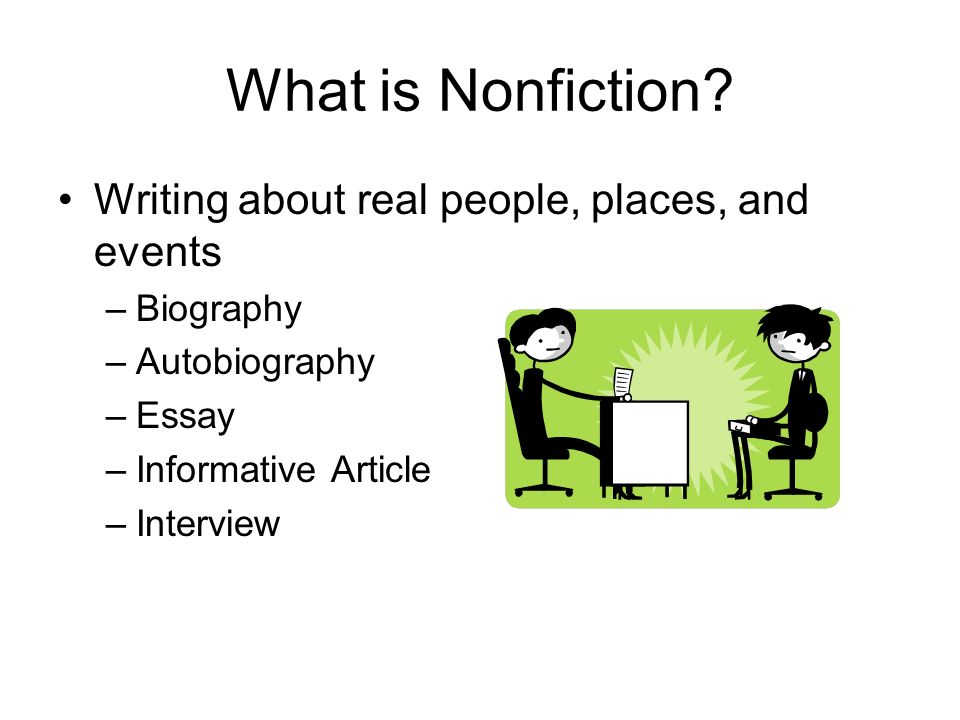

A nonfiction story

Creative Nonfiction / True stories, well told.

Current Issue / Issue 78 Fall 2022

What is voice? How do you find yours? How can you change it, rearrange it, play with it? And then, how can you use it to make change in the world?

This issue is a celebration of writerly playfulness, exploration, and risk-taking, featuring breathless, epistolary, speculative, second-person, and snarky essays. Plus, an interview with Hysterical memoirist Elissa Bassist, close reads of work by Steve Coughlin, Jaquira Díaz, Margo Jefferson, and R. Eric Thomas, micro-essays, and more.

Including essays by

Sonya Huber, Beth Kephart, Leath Tonino, Jill Christman & more.

Explore Issue 78

Explore Creative Nonfiction

Can’t get enough? Browse 25 years of archives.

View by Issue

Select an Issue Issue 78 Issue 77 Issue 76 Issue 75 Issue 74 Issue 73 Issue 72 Issue 71 Issue 70 Issue 69 Issue 68 Issue 67 Issue 66 Issue 65 Issue 64 Issue 63 Issue 62 Issue 61 Issue 60 Issue 59 Issue 58 Issue 57 Issue 56 Issue 55 Issue 54 Issue 53 Issue 52 Issue 51 Issue 50 Issue 49 Issue 48 Issue 47 Issue 46 Issue 45 Issue 44 Issue 43 Issue 42 Issue 41 Issue 40 Issue 39 Issue 38 Issue 37 Issue 36 Issue 35 Issue 34 Issue 33 Issue 32 Issue 31 Issue 30 Issue 29 Issue 28 Issue 27 Issue 26 Issue 24/25 Issue 23 Issue 22 Issue 21 Issue 20 Issue 19 Issue 18 Issue 17 Issue 16 Issue 15 Issue 14 Issue 13 Issue 12 Issue 11 Issue 10 Issue 09 Issue 08 Issue 07 Issue 06 Issue 05 Issue 04 Issue 03 Issue 02 Issue 01

View by Type

Select a TypeBook ExcerptsCNF QuarterlyCraft & ProcessDiscussions & RoundtablesEditor’s NoteEssay & MemoirExperimental & Hybrid FormsFlashInterviews & ProfilesLongformSunday Short ReadsThe Writing LifeTrue StoryView by Topic

Select a TopicArt & Movies & MusicBirth & BabiesBody & MindClimate & Environment & NatureCulture & IdentityEnd of LifeFamilyFood & DrinkFriendshipHealthcare & HealingHistory & HeritageJournalism & ReportageLaw & PolicyMental HealthPlants & AnimalsPopularRecommended ReadingReligion & SpiritualityScience & TechnologySex & LoveSurviving TraumaTravel & PlaceWork & MoneyWriting & Publishing

CNF Education

Writing can be lonely. Often, what we need most as writers is a network of focused peers and professionals who can provide constructive feedback, keep us motivated, and inspire us to do our best work. You don’t have to write alone.

From online classes to webinars, all year round, CNF offers a variety of ways you can connect with the broader creative nonfiction community and learn new skills, generate new writing, stay focused, and create your best work.

Explore Education

About the Genre

What is Creative Nonfiction?

Dive in with CNF Founder and Editor, Lee Gutkind

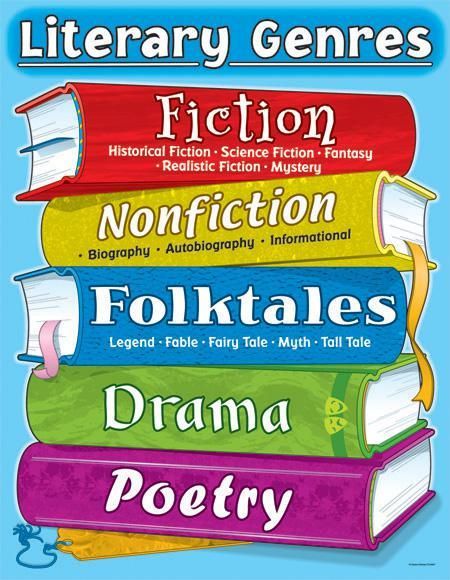

Creative Nonfiction magazine defines the genre simply, succinctly, and accurately as “true stories well told.” And that, in essence, is what creative nonfiction is all about.

In some ways, creative nonfiction is like jazz—it’s a rich mix of flavors, ideas, and techniques, some newly invented and others as old as writing itself.

Read the Full ArticleTrue Story

Each pocket-size issue our monthly mini-magazine showcases one exceptional longform essay by one exceptional writer.

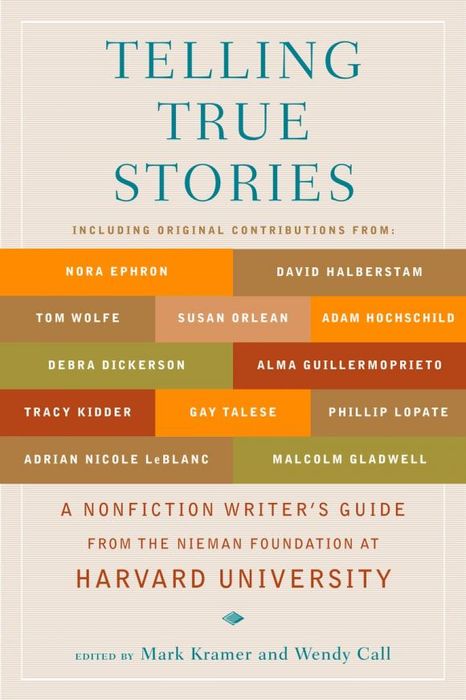

50 Great Narrative Nonfiction Books To Get On Your TBR List

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

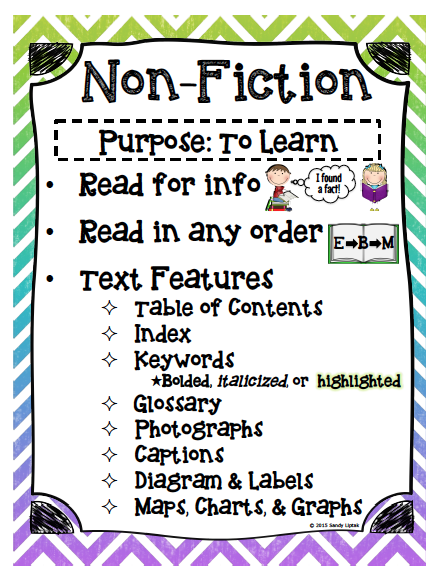

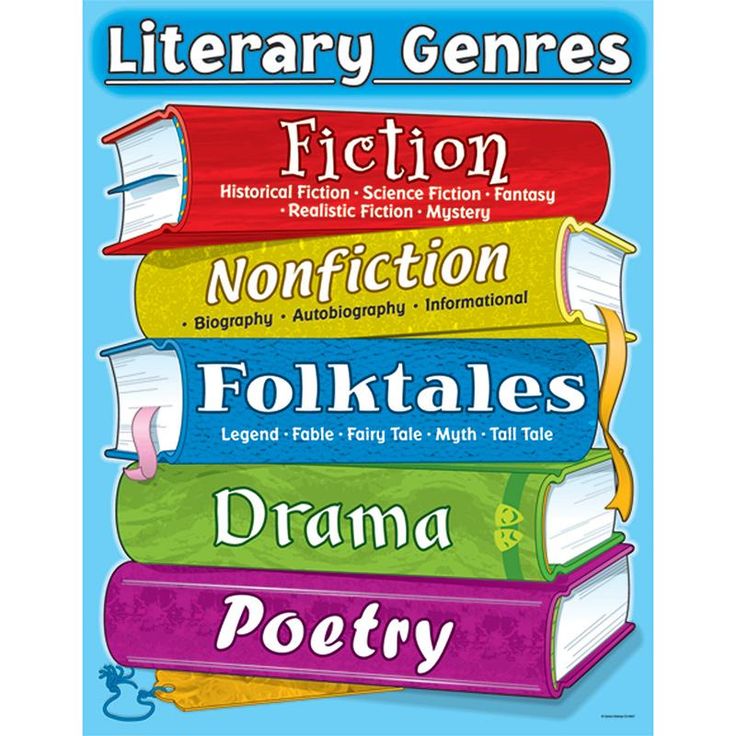

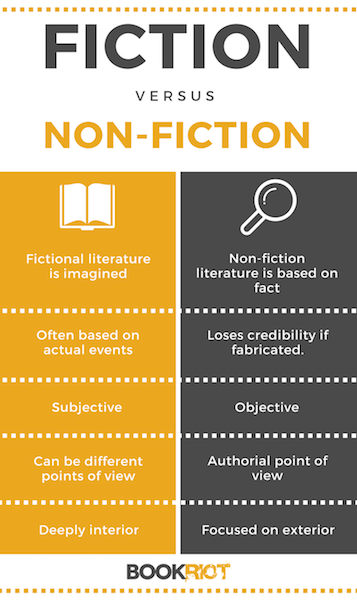

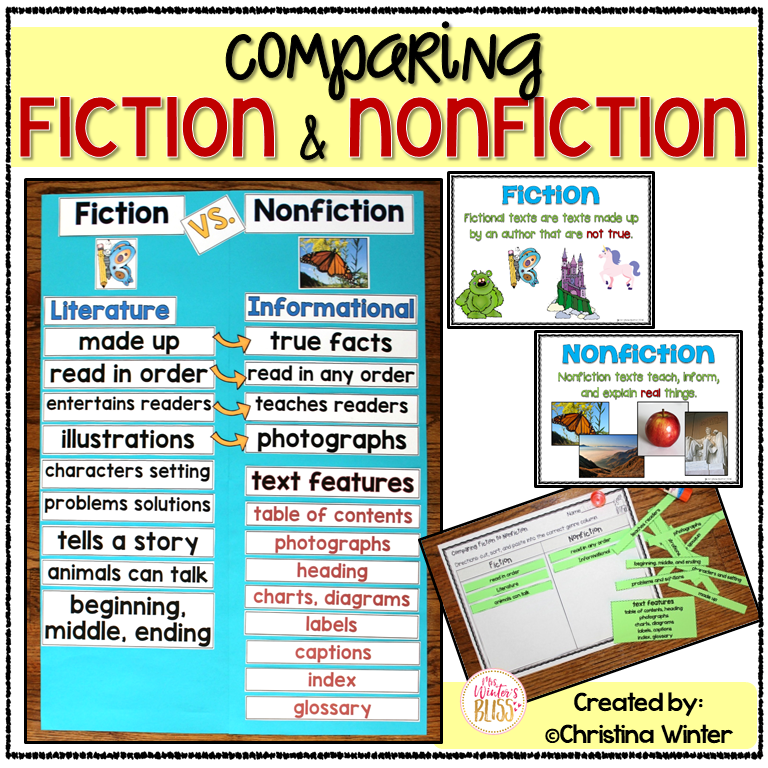

Narrative nonfiction—also known as creative nonfiction or literary nonfiction—is usually defined as nonfiction that uses the techniques and style of fiction (characters, plot, conflict, scene-setting) to tell a true story. Narrative nonfiction books can cover just about any topic, but if you pick one up you’re almost guaranteed to have a great reading experience.

This list a collection of 50 great narrative nonfiction books, although it easily could have been much longer. A few caveats: I tried not to include straight autobiographies or memoirs because I wanted to keep this list focused on books that highlight strong research/reporting along with narrative voice. I also included just one book from any given author. If you’ve already read the book I’ve listed, most of these writers have an extensive backlist to explore. And, of course, this list of narrative nonfiction isn’t nearly comprehensive—that’d be basically impossible.

And, of course, this list of narrative nonfiction isn’t nearly comprehensive—that’d be basically impossible.

Science

The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee—An in-depth biography of cancer.

Being Mortal by Atul Gawande—Medicine, life, and choices about how we die.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot—History of the most prolific cells in science.

Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly—African American female mathematicians and the race to space.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach—The strange science used to get astronauts ready for space.

Leaving Orbit by Margaret Lazarus Dean—“Notes from the last days of American spaceflight”

Annals of the Former World by John McPhee—Four books collected into one giant work on the geological history of North America.

The Secret Life of Lobsters by Trevor Corson—“How fishermen and scientists are unraveling the mysteries of our favorite crustacean.”

Global Issues

Night Draws Near by Anthony Shadid—A portrait of Iraqi citizens “weathering the unexpected impact of America’s invasion and occupation. ”

”

Behind the Beautiful Forevers by Katherine Boo—Life in a Mumbai slum.

Mountains Beyond Mountains by Tracy Kidder—One doctor’s work bringing medical care to those most in need.

Without You, There Is No Us by Suki Kim—A reporter goes inside a school for the sons of North Korea’s elite.

Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick—North Korean defectors tell what it’s like inside the country.

Reading Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi—Reading American classics in revolutionary Iran.

The Secretary by Kim Ghattas—An inside account of Hillary Clinton’s term as Secretary of State by a traveling journalist.

The Lonely War by Nazila Fathi—An Iranian journalist’s account of the struggle for reform in modern Iran.

History

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson—The great migration of African Americans to northern cities, and the impact it has today.

Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand—World War II tale of survival after being shot down over the Pacific Ocean.

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown—Olympic rowing at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (this book is amazing!).

Sin in the Second City by Karen Abbott—Stories from America’s favorite Victorian-era brothel and the culture war it inspired.

Eighty Days by Matthew Goodman—Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland race around the world in 1889.

In the Garden of Beasts by Erik Larson—America’s ambassador to Germany, and his headstrong daughter, in the lead up to World War II.

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann—A conspiracy against the Osage tribe, and the birth of the FBI.

The Wordy Shipmates by Sarah Vowell—The Puritans and their strange journey to found America

Galileo’s Daughter by Dava Sobel—A look at the relationship between Galileo and his oldest daughter, a nun named Maria Celeste.

The Romanov Sisters by Helen Rappaport—A look at the fall of the Romanov family, focusing specifically on the lives of Nicholas and Alexandra’s four daughters, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia.

City of Light, City of Poison by Holly Tucker—An account of Paris’s first police chief and a poisonous murder epidemic in the late 1600s.

Narrative Nonfiction Classics

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote—The original true crime nonfiction novel.

The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean—Obsession and rare flowers in the Florida Everglades.

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer—The story of a harrowing, deadly climb on Mount Everest.

Random Family by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc—“Love, drugs, trouble, and coming of age in the Bronx.”

Friday Night Lights by Buzz Bissinger—The big business of high school football in Texas.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion—Essays on a feminist journalist’s experiences in California in the 1960s.

Newjack by Ted Conover—A journalist goes undercover as a prison officer in Sing Sing to better understand the penal system.

The Monster of Florence by Douglas Preston and Mario Spezi—Historical true crime on Italy’s Jack the Ripper, who killed between 1968 and 1985.

The Blind Side by Michael Lewis—A sports biography on one man’s journey to the NFL and the evolution of the game.

Social Issues

Does Jesus Really Love Me? by Jeffrey Chu—A gay Christian looks for God in America.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman—Cultural barriers in life and medicine (so good!).

Evicted by Matthew Desmond—Poverty, profits and the eviction crisis in America.

Gang Leader for a Day by Sudhir Venkatesh—A sociologist spend a decade in Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes to better understand the lives of the urban poor.

Homicide by David Simon—A look at one year spent with homicide detectives in Baltimore.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge—A journalist puts a human face on gun violence by writing about the 10 teenagers killed by guns on a single day in America.

Methland by Nick Reding—A look at the impact of meth on small towns, based on four years of reporting in an agricultural town in Iowa.

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts—The first and perhaps most comprehensive look at the AIDS crisis.

Contemporary Reporting

The Man Who Loved Books Too Much by Allison Hoover Bartlett—“The true story of a thief, a detective, and a world of literary obsession.”

The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu by Joshua Hammer—A group of librarians banded together to pull of a literary heist to save precious Arabic texts from Al Qaeda.

Moby Duck by Donovan Hohn—“The true story of 28,800 bath toys lost at sea and of the beachcombers, oceanographers, environmentalists and fools, including the author, who went in search of them.”

Columbine by Dave Cullen—The definitive account of the Columbine shooting.

Five Days at Memorial by Sheri Fink—Life and death and medical malpractice at a hospital ravaged by Hurricane Katrina.

Tribe by Sebastian Junger—Learning about loyalty and belonging from tribal societies.

If you enjoyed this list and want more narrative nonfiction content, check out our True Story newsletter. Sign up here!

Sign up here!

history of Russian popular science literature / Habr

Accessible and interesting literature about science is a magic wand that helps progress not to slow down and move forward. Thanks to her, children begin to learn voluntarily and with interest, and adults broaden their horizons and do not let the brain relax. Biology, astronomy and mathematics are replacing sagas about regular elves and intergalactic ships. And if in Western countries the pop-science quietly developed from Jules Verne to Yudkovsky's "Less Wrong", then in Russia it experienced both ups and downs.

Russian Empire

Until the 19th century, science was considered an elitist occupation, and scientific works for a wide range of readers were isolated experiments. The industrial revolution changed everything. The role of science in people's lives has grown dramatically, it has attracted attention, and there has been a demand for accessible scientific content. It was also required in Russia, where scientific literature stalled along with technical progress.

It was also required in Russia, where scientific literature stalled along with technical progress.

In the Russian Empire, the state treated the press tensely, and any publishing sneeze was coordinated with the censorship committees, which were guided by church dogmas. The most popular literature was low-grade mysticism, and society was dominated by the attitude “everyone should do what they must”: women give birth, peasants plow, and only the elite are engaged in science. Some scientists even believed that it was in no way possible to profane science, and that the very idea of popular science literature was evil. But with the development of industry in Russia, a need arose for accessible scientific publications, and there were those who took up this risky business.

The first sign in 1861 was the magazine “Vokrug sveta”: it published foreign translations and notes on Russian geography. The magazine was published for only 7 years, and then closed until 1885. The revived “Around the World” relied on a low price and compensated for it with an abundance of advertising. Gradually, the quality of publications dropped to a collection of adventurous and adventure stories. In 1891, the creator of the first Russian media empire, I. D. Sytin, saved the situation. He formed a new edition and made "Around the World" a mass publication, which published information about scientific discoveries and new inventions. The October Revolution made its own adjustments: the entire publishing empire of Sytin was nationalized, Around the World was closed, and the simple Russian peasant Ivan Sytin refused V.I. Lenin to head the State Publishing House and retired.

The revived “Around the World” relied on a low price and compensated for it with an abundance of advertising. Gradually, the quality of publications dropped to a collection of adventurous and adventure stories. In 1891, the creator of the first Russian media empire, I. D. Sytin, saved the situation. He formed a new edition and made "Around the World" a mass publication, which published information about scientific discoveries and new inventions. The October Revolution made its own adjustments: the entire publishing empire of Sytin was nationalized, Around the World was closed, and the simple Russian peasant Ivan Sytin refused V.I. Lenin to head the State Publishing House and retired.

Even less lucky with the launch of the journal "Priroda". Zoologist and psychologist V.A. Wagner conceived it under the influence of Chekhov and almost launched it in the 80s, but the publisher was afraid of problems with censorship. Chekhov's idea was realized only in 1912. In an address to readers, the editors wrote that they consider this format "the best way to combat prejudice, with the influence of scholasticism and metaphysics." This attitude turned out to be close to many, and well-known physicists and biologists began to cooperate with the journal; it published translations of articles by Planck and Einstein. Under the auspices of the journal, books were published, lectures were held; it has become a platform for communication between scientists.

In an address to readers, the editors wrote that they consider this format "the best way to combat prejudice, with the influence of scholasticism and metaphysics." This attitude turned out to be close to many, and well-known physicists and biologists began to cooperate with the journal; it published translations of articles by Planck and Einstein. Under the auspices of the journal, books were published, lectures were held; it has become a platform for communication between scientists.

In 1889, the publishing house P.P. Soykin published and immediately became popular magazine "Nature and People". It published information about the latest technical innovations from around the world, articles by Tsiolkovsky and members of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. In 1901, he began working in the magazine, and in 1913 Yakov Perelman became the editor-in-chief. His "Entertaining Physics" was a huge success with readers and positive reviews from professional scientists. The word "entertaining" becomes a household word for any popular science books.

The word "entertaining" becomes a household word for any popular science books.

Country of the victorious proletariat

The First World War, the Revolution and the Civil War shook the Russian society. People are tired of politics: no one read Marx, Lenin and the like, but fiction, classics and scientific books were swept away from book sales. There was a huge demand for self-education, and society needed accessible scientific and technical literature.

The Civil War was still in full swing, and in 1919 Yakov Perelman launched the first Soviet popular science magazine, In the Workshop of Nature. After a one-year break, she resumed her work under the auspices of the Academy of Sciences "Priroda". A little later, new editions appeared: “Radio Amateur” (1924), “Knowledge is Power” (1926), “Young Naturalist” (1928). "Nature and People" (1927) and "Around the World" (1927) are being revived. Prior to the creation of a publishing monopoly in 1930, popular science literature was actively printed by private publishing houses. Only in the publishing house P.P. Soikin published about a hundred books: “In the sands of the Karakums” by A.E. Fersman, “On the Liu Kiu Islands” by P.Yu. Schmidt, “In the Heart of Asia” by P.K. Kozlova…

Only in the publishing house P.P. Soikin published about a hundred books: “In the sands of the Karakums” by A.E. Fersman, “On the Liu Kiu Islands” by P.Yu. Schmidt, “In the Heart of Asia” by P.K. Kozlova…

The interests of society were strengthened by state projects: the cyclopean Soviet construction projects and forced industrialization required a huge number of qualified personnel and serious advertising. Lenin's comrade-in-arms and former member of the Politburo, N.I. Bukharin. The journals Socialist Reconstruction and Science - SoRena appeared (1931), Technique for the Youth (1933), and the journal Science and Life (1934) was reborn.

After the consolidation of all publishing houses into OGIZ, the future Fizmatlit, ONTI (United Scientific and Technical Publishing House), and DETGIZ, headed by S. Marshak, become the largest publishers of popular science literature. They published the series “Science for the Masses”, “Technical and Constructive Series” for children, “Entertaining Sciences” by Yakov Perelman, books by M. P. Bronstein, S.A. Lurie. Soviet popular science literature was exported: they were translated into all European languages and published in the USA “What time is it?”, “Black and white”, “100,000 why”, “The story of the great plan”, “Mystery tale”, “How a Man Became a Giant” by M. Ilyin.

P. Bronstein, S.A. Lurie. Soviet popular science literature was exported: they were translated into all European languages and published in the USA “What time is it?”, “Black and white”, “100,000 why”, “The story of the great plan”, “Mystery tale”, “How a Man Became a Giant” by M. Ilyin.

The problem was that the young Soviet state did not provide the population with high-quality popular science literature. There were not enough capacities, paper, but especially there were not enough authors. The incompetence of the censors, the orientation towards the opinion of the party leadership and the fear of reprisals hampered popular science literature: many topics were banned, and experienced engineers who were trained in Tsarist Russia, journalists and writers turned out to be class enemies with all tragic consequences.

The Party began searching for authors among the workers: on December 31, 1931, a decree was issued "on the involvement of workers in the creation of a mass technical book. " It didn't help. In the second half of the 1930s, both ONTI and DETGIZ began to overwhelm the overblown plans descending from above. And if ONTI was simply disbanded, then the Leningrad branch of DETGIZ was destroyed. In 1936, Priroda's main competitor, the magazine SoReNa, was closed and withdrawn from all libraries, and in 1938 N.I. Bukharin was shot.

" It didn't help. In the second half of the 1930s, both ONTI and DETGIZ began to overwhelm the overblown plans descending from above. And if ONTI was simply disbanded, then the Leningrad branch of DETGIZ was destroyed. In 1936, Priroda's main competitor, the magazine SoReNa, was closed and withdrawn from all libraries, and in 1938 N.I. Bukharin was shot.

And yet, in the USSR, an organization was found in which there were unfinished personnel. She was the Academy of Sciences. In the Academy of Sciences, the optical physicist, Academician S.I. Vavilov. In 1935, he became chairman of the commission of the USSR Academy of Sciences on popular science literature, and in 1936 he headed the editorial board of Priroda and even squeezed out of the editorial office Stalin's favorite and murderer of Soviet genetics, Academician T. D. Lysenko.

In 1938, the publishing house of the USSR Academy of Sciences launched three series at once: “The Academy of Sciences of the USSR for the Stakhanovites” edited by the President of the Academy of Sciences V. L. Komarov, on exact and natural sciences, edited by S.I. Vavilov and a series dedicated to agriculture. Despite the growth in the number of popular science publications, they were sorely lacking and quality books were sold out instantly.

L. Komarov, on exact and natural sciences, edited by S.I. Vavilov and a series dedicated to agriculture. Despite the growth in the number of popular science publications, they were sorely lacking and quality books were sold out instantly.

The war put an end to this development. Many magazines were closed, and in 1942 Y. Perelman died of starvation in Leningrad. But popular science literature continued to live. Alone, working for the entire editorial staff, he pulled the journal “Priroda”, first in besieged Leningrad, and then in the evacuation, professor-lichenologist V.P. Savich. He halved the number of issues, but "Science and Life" was published.

Popular scientific books were published: A.I. Oparin “The Emergence of Life on Earth” (1941), I.M. Sechenov “Reflexes of the brain” (1942), S.I. Vavilov “The eye and the sun. On Light, Sun and Vision” (1944), N.P. Voronikhin “The Flora of the Ocean” (1945), M.M. Pokrovsky “History of Roman Literature” (1945), S. Ya. Lurie "Archimedes" (1945). The Academy of Sciences, evacuated to Kazan, published several books dedicated to the 300th anniversary of I. Newton.

Ya. Lurie "Archimedes" (1945). The Academy of Sciences, evacuated to Kazan, published several books dedicated to the 300th anniversary of I. Newton.

It was at this time, 1943-1944, that the state scientific and technical policy was formulated, which became the basis for the future system of science popularization. On September 27, 1944, a resolution of the Central Committee "On the organization of scientific and educational propaganda" was issued, and on December 14, 1944 years in Izvestia - article by S.I. Vavilov "The duty of the Soviet intelligentsia". The destroyed Soviet Union urgently needed qualified personnel.

Golden age

The war showed that it is not dashing attacks in the forehead that win, but accuracy, fault tolerance and maintainability. It was the "war of motors". The "space race" and "arms race" that followed it demanded scientific advances. In July 1945, S.I. Vavilov was elected president of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In 1947, the society "Knowledge" was created, the purpose of which was the mass education of the population. The state finally approved the system of popularization of science and made it an obligatory part of scientific activity.

In 1947, the society "Knowledge" was created, the purpose of which was the mass education of the population. The state finally approved the system of popularization of science and made it an obligatory part of scientific activity.

The output of non-fiction literature grew steadily. New magazines appeared: "Young Technician" (1956), "Model Designer" (1962), "Science and Humanity" (1965), "Chemistry and Life" (1965), "Earth and Universe" (1965), "Quantum (1970). In total, about 83 popular science magazines were published in the USSR. Competition developed between them, the editors experimented, used unusual illustrations, and released fantastic works. The circulation of Science and Life reached 3 million a year, and in 1977 it published a draft of a new constitution for the USSR.

Perelman's books were republished in millions of copies, the series came out: “From the history of world culture”, “History and modernity”, “History of science and technology”, “Pages of the history of our Motherland”, “Peoples of the world”, “The present and future of the Earth and mankind ”, “Man and the Environment”, “Science for Agriculture”, “Science and Technological Progress”, “Scientific-Atheistic Series”, “Scientific Biographies and Memoirs of Scientists”, “From Molecule to Organism”, “Planet Earth and Universe " and many others. In the 1980s, the publishing house of the USSR Academy of Sciences, renamed Nauka, was the largest scientific publishing house in the world. But it was then that the same thing happened as 70 years ago with political literature: the population was tired of mass propaganda.

In the 1980s, the publishing house of the USSR Academy of Sciences, renamed Nauka, was the largest scientific publishing house in the world. But it was then that the same thing happened as 70 years ago with political literature: the population was tired of mass propaganda.

Disaster

In the USSR, everyone read popular science literature. Except for his leadership. Political mistakes were replaced by economic ones and vice versa - the chance to become a world research institute was irretrievably lost, industry stood up, the standard of living collapsed, and normal scientists preferred countries with a warmer climate and sane law enforcement agencies. The population switched to science fiction and mysticism, and the state relied on religion.

Popular science literature collapsed. The surviving magazines reduced circulation by a hundred times, and no one needed books. Nauka became a typical state monopoly on the entire academic press and was on the verge of bankruptcy. The Knowledge Society has collapsed, and an attempt to revive it is more like necromancy with the creation of zombies. Fizmatlit was torn into two parts: private and state.

The Knowledge Society has collapsed, and an attempt to revive it is more like necromancy with the creation of zombies. Fizmatlit was torn into two parts: private and state.

But there were also local successes on this front. Computer technology magazines such as Computerra (1992), Byte (1998), CHIP (2001) have emerged. And in the 90s, the Quantum magazine was published in the USA with translations from Quantum.

In the 2000s, despite the inaction of the state and the general crisis in the publishing industry, the situation began to gradually improve. New journals appeared: Popular Mechanics (2002), Science First Hand (2004), Machines and Mechanisms (2005), Science and Technology (2006), Quantik (2012), Schrödinger's Cat (2014).

It suddenly became clear that in the 21st century there is no way without R&D, and scientific pop began to revive behind this understanding. Private publishing houses gradually translate foreign authors, reprint Soviet ones, and their own publishers appear: M. S. Gelfand, Asya Kazantseva, A.M. Raygorodsky, L.I. Podymov. This, of course, is a drop in the bucket, but…

S. Gelfand, Asya Kazantseva, A.M. Raygorodsky, L.I. Podymov. This, of course, is a drop in the bucket, but…

Not everything is so bad and it's too early to whine.

We live in an interesting time: the education system does not keep up with progress, and the huge demand for self-education is compensated by information technology. Cyberleninka, Sci-hub, Rutracker.org, Flibusta, Habr.com, Anthropogenesis.ru, Postnauka, Simple Science, Elements of Big Science, N+1, Naked Science have occupied the niche of the Academy of Sciences and make scientific content really accessible and, most importantly, interesting. Large technology companies create newsrooms and, in fact, are engaged in “tech propaganda”. Amateurs massively translate articles from foreign sources. The areas in which we are traditionally strong are being popularized: mathematics, physics, programming, biology.

As a result, the Russian Internet is filled with high-quality and accessible foreign scientific content, which rests on the powerful Soviet legacy. It turned out to be a paradoxical situation: due to the failure of traditional publishing houses, digital resources that generate high-quality content receive an impetus for development. Russian popular science literature, a famous brand with a rich history, turns out to be alive and competitive. It remains only to wait when he will finally cope with the crisis and enter the world market.

It turned out to be a paradoxical situation: due to the failure of traditional publishing houses, digital resources that generate high-quality content receive an impetus for development. Russian popular science literature, a famous brand with a rich history, turns out to be alive and competitive. It remains only to wait when he will finally cope with the crisis and enter the world market.

P.S.

The article used:

- Illustrations by Vasya Lozhkin and Alexander Seleznev

- facts from Andrey Vaganov's book "The Genre We Lost: An Essay on the History of Russian Popular Science Literature"

- Quantum Journal Archive

Non-fiction books on the history of the country or period: chto_chitat — LiveJournal

A small digression for overclockingAs a child (like many) I was a smart and promising child. And I really, really liked to read "adult" books, trying to understand them, and I got great pleasure from these difficulties.

I remember that at the age of 6-7 I took up Tolstoy's "Peter 1st" and my mother's school history of the Middle Ages. And after all, I overcame and enjoyed it! According to this logic, I would grow with age, develop and switch to reading professional historians in the original language. But no - from the age of 15 she began to read fairy tales en masse, and then gradually switched to pop-science.

I remember that at the age of 6-7 I took up Tolstoy's "Peter 1st" and my mother's school history of the Middle Ages. And after all, I overcame and enjoyed it! According to this logic, I would grow with age, develop and switch to reading professional historians in the original language. But no - from the age of 15 she began to read fairy tales en masse, and then gradually switched to pop-science. But actually this is all a saying, and the fairy tale will just be about historical science fiction, namely about books (and films) on long periods of the history of the country (s) - in the wake of disappointment with Akunin's "History" I want to collect a list of those stories from different countries that I liked community members. I want a combination of interest, emotions and undistorted (or at least minimally distorted) scientific facts. And also - the show and history in general - the feudal system there, capitalism is emerging, they began to print books, and personalities. Because in order for the story to be interesting, you can’t go anywhere without personalities, and you don’t want to read without them, and it’s impossible to remember which king followed which one. And let professional historians throw stones at me, but for me, bad-good ratings do not make a history book unusable.

And let professional historians throw stones at me, but for me, bad-good ratings do not make a history book unusable.

* My favorite is Churchill's History of the English-speaking Peoples, or rather the first two volumes of 4. With the third volume, too much party struggle between Whigs and Tories begins for my taste. This, of course, is close to the author, but I feel like a schoolboy who is flooded with political information about the next congress of the CPSU.

* Druon's Paris from Caesar to Saint Louis would also be good, but the book is too short. I wouldn’t get tired of reading before De Gaulle, well, before Napoleon III for sure, but I won’t demand too much, but why didn’t the author of Damned Kings tell about the Hundred Years War ?!

* Barbara Merz - two books on the history of ancient Egypt and a book on the history of Rome. Here, by the way, about personality in books. Alas, there is little left of the memories of personalities from Ancient Egypt, even about such interesting ones as Hatshepsut or Akhenaten.