Calm down kid

How to Help Children Calm Down

Many children have difficulty regulating their emotions. Tantrums, outbursts, whining, defiance, fighting: these are all behaviors you see when kids experience powerful feelings they can’t control. While some kids have learned to act out because it gets them what they want — attention or time on the iPad — other kids have trouble staying calm because they are unusually sensitive.

The good news is that learning to calm down instead of acting out is a skill that can be taught.

What is dysregulation?

“Some children’s reactions are just bigger than their peers or their siblings or their cousins,” explains Lindsey Giller, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. “Not only do they feel things more intensely and quickly, they’re often slower to return to being calm.” Unusually intense feelings can also make a child more prone to impulsive behaviors.

When kids are overwhelmed by feelings, adds Dr. Giller, the emotional side of the brain isn’t communicating with the rational side, which normally regulates emotions and plans the best way to deal with a situation. Experts call it being “dysregulated.” It’s not effective to try to reason with a child who’s dysregulated. To discuss what happened, you need to wait until a child’s rational faculties are back “online.”

Rethinking emotions

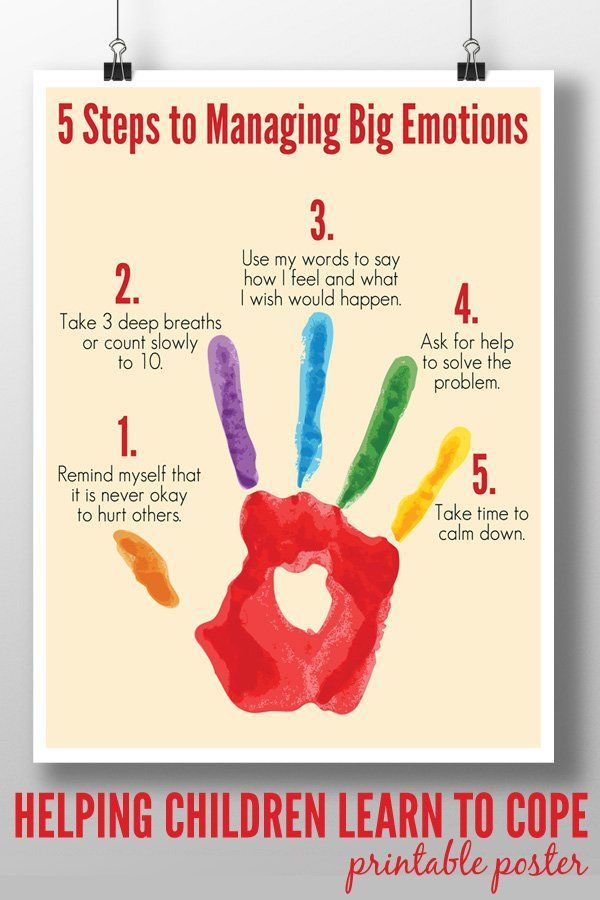

Parents can start by helping children understand how their emotions work. Kids don’t go from calm to sobbing on the floor in an instant. That emotion built over time, like a wave. Kids can learn control by noticing and labeling their feelings earlier, before the wave gets too big to handle.

Some kids are hesitant to acknowledge negative emotions. “A lot of kids are growing up thinking anxiety, anger, sadness are bad emotions,” says Stephanie Samar, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. But naming and accepting these emotions is “a foundation to problem-solving how to manage them.”

Parents may also minimize negative feelings, notes Dr. Samar, because they want their kids to be happy. But children need to learn that we all have a range of feelings. “You don’t want to create a dynamic that only happy is good,” she says.

“You don’t want to create a dynamic that only happy is good,” she says.

Model managing difficult feelings

“For younger children, describing your own feelings and modeling how you manage them is useful,” notes Dr. Samar. “They hear you strategizing about your own feelings, when you’re nervous or frustrated, and how you’re going to handle it, and they can use these words.”

For kids who feel like big emotions sneak up on them, you can help them practice recognizing their emotions, and model doing that yourself. Try ranking the intensity of your emotions from 1-10, with 1 being pretty calm and 10 being furious. If you forget something that you meant to bring to Grandma’s, you could acknowledge that you are feeling frustrated and say that you’re at a 4. It might feel a little silly at first, but it teaches kids to pause and notice what they are feeling.

If you see them starting to get upset about something, ask them what they are feeling, and how upset they are. Are they at a 6? For some younger kids, a visual aid like a feelings thermometer might help.

Are they at a 6? For some younger kids, a visual aid like a feelings thermometer might help.

Validate your child’s feelings

Validation is a powerful tool for helping kids calm down by communicating that you understand and accept what they’re feeling. “Validation is showing acceptance, which is not the same thing as agreement,” Dr. Giller explains. “It’s nonjudgmental. And it’s not trying to change or fix anything.” Feeling understood, she explains, helps kids let go of powerful feelings.

Effective validation means paying undivided attention to your child. “You want to be fully attuned so you can notice her body language and facial expressions and really try to understand her perspective,” says Dr. Samar. “It can help to reflect back and ask, ‘Am I getting it right?’ Or if you’re truly not getting it, it’s okay to say, ‘I’m trying to understand.’ ”

Helping kids by showing them that you’re listening and trying to understand their experience can help avoid explosive behavior when a child is building towards a tantrum.

Active ignoring

Validating feelings doesn’t mean giving attention to bad behavior. Ignoring behaviors like whining, arguing, inappropriate language or outbursts is a way to reduce the chances of these behaviors being repeated. It’s called “active” because it’s withdrawing attention conspicuously.

“You’re turning your face, and sometimes body, away or leaving the room when your child is engaging in minor misbehaviors in order to withdraw your attention,” Dr. Giller explains. “But the key to its effectiveness is, as soon as your child is doing something you can praise, to turn your attention back on.”

Positive attention

The most powerful tool parents have in influencing behavior is attention. As Dr. Giller puts it, “It’s like candy for your kids.” Positive attention will increase the behaviors you are focusing on.

When you’re shaping a new behavior, you want to praise it and give a lot of attention to it. “So really, really focus in on it,” adds Dr. Giller. “Be sincere, enthusiastic and genuine. And you want it to be very specific, to make sure your child understands what you are praising.”

Giller. “Be sincere, enthusiastic and genuine. And you want it to be very specific, to make sure your child understands what you are praising.”

When helping your child deal with an emotion, notice the efforts to calm down, however small. For example, if your child is in the midst of a tantrum and you see him take a deep inhale of air, you can say, “I like that you took a deep breath” and join him in taking additional deep breathes.

Clear expectations

Another key way to help prevent kids from getting dysregulated is to make your expectations clear and follow consistent routines. “It’s important to keep those expectations very clear and short,” notes Dr. Samar, and convey rules and expected behaviors when everyone is calm. Dependable structure helps kids feel in control.

When change is unavoidable, it’s good to give advance warning. Transitions are particularly tough for kids who have trouble with big emotions, especially when it means stopping an activity they’re very engaged in. Providing a warning before a transition happens can help kids feel more prepared. “In 15 minutes, we’re going to sit down at the table for dinner, so you’re going to need to shut off your PS4 at that time,” Dr. Giller suggests. It may still be hard for them to comply, but knowing it’s coming helps kids feel more in control and stay calmer,” she explains.

Providing a warning before a transition happens can help kids feel more prepared. “In 15 minutes, we’re going to sit down at the table for dinner, so you’re going to need to shut off your PS4 at that time,” Dr. Giller suggests. It may still be hard for them to comply, but knowing it’s coming helps kids feel more in control and stay calmer,” she explains.

Give options

When kids are asked to do things they’re not likely to feel enthusiastic about, giving them options may reduce outbursts and increase compliance. For instance: “You can either come with me to food shopping or you can go with Dad to pick up your sister.” Or: “You can get ready for bed now and we can read a story together — or you can get ready for bed in 10 minutes and no story.”

“Giving two options reduces the negotiating that can lead to tension,” Dr. Samar suggests.

Coping ahead

Coping ahead is planning in advance for something that you predict may be an emotionally challenging situation for your child, or for both of you. It means talking, when you are both calm, about what’s coming, being direct about what negative emotions can arise, and strategizing how you will get through it.

It means talking, when you are both calm, about what’s coming, being direct about what negative emotions can arise, and strategizing how you will get through it.

If a child was upset last time she was at Grandma’s house because she wasn’t allowed to do something she gets to do at home, coping ahead for the next visit would be acknowledging that you saw that she was frustrated and angry, and discussing how she can handle those feelings. Together you might come up with something she is allowed to do at Grandma’s that she can have fun doing.

Talking about stressful situations in advance helps avoid meltdowns. “If you set up a plan in advance, it increases the likelihood that you’ll end up in a positive situation,” Dr. Samar notes.

Problem solving

If a child has a tantrum, parents are often hesitant to bring it up later, Dr. Samar notes. “It’s natural to want to put that behind us. But it’s good to revisit briefly, in a non-judgmental way.”

Revisiting an earlier event — say a meltdown at the toy store — engages the child in thinking about what happened, and to strategize about what could have been done differently. If you can come up with one or two things that might have led to a different outcome, your child might remember them next time he’s starting to feel overwhelmed.

If you can come up with one or two things that might have led to a different outcome, your child might remember them next time he’s starting to feel overwhelmed.

Five special minutes a day

Even a small amount of time set aside reliably, every day, for mom or dad to do something chosen by a child can help that child manage stress at other points in the day. It’s a time for positive connection, without parental commands, ignoring any minor misbehavior, just attending to your child and letting her be in charge.

It can help a child who’s having a tough time in school, for instance, to know she can look forward to that special time. “This five minutes of parental attention should not be contingent on good behavior,” says Dr. Samar. “It’s a time, no matter what happened that day, to reinforce that ‘I love you no matter what.’ ”

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you help an angry child calm down?You can help an angry child calm down by validating their feelings and listening actively to understand what’s upsetting them. Your attention is your most powerful tool, so it helps to give your child lots of positive attention as soon as they do something to calm down: “I like that you took a deep breath!”

Your attention is your most powerful tool, so it helps to give your child lots of positive attention as soon as they do something to calm down: “I like that you took a deep breath!”

Video Resources for Kids

Teach your kids mental health skills with video resources from The California Healthy Minds, Thriving Kids Project.

Start Watching

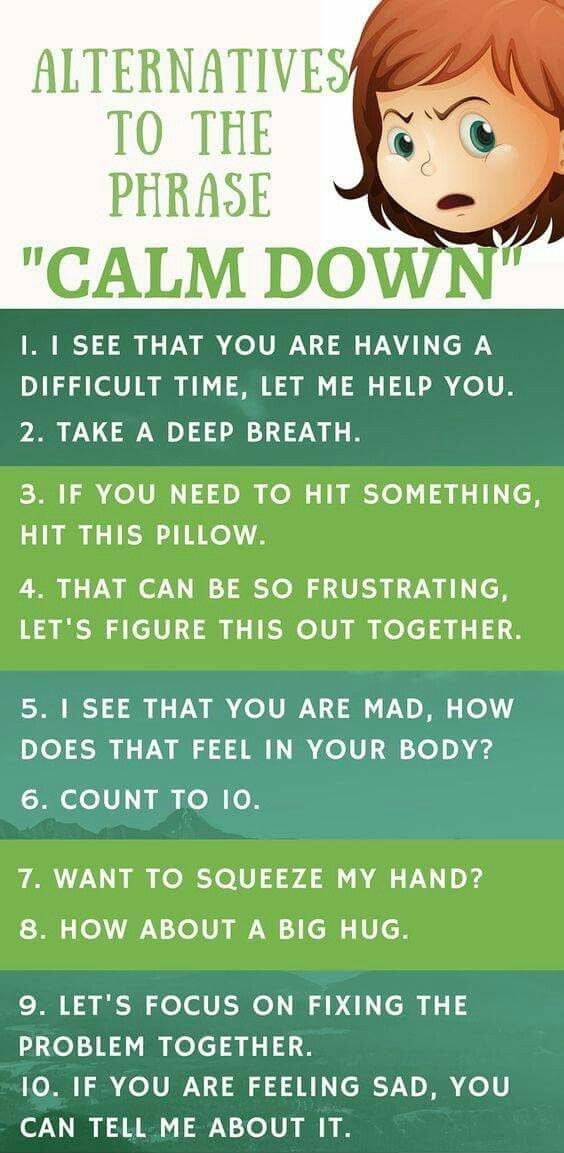

10 Ways to Teach Kids to Calm Down

Being able to resolve conflicts is one of the most important social skills our kids need in order to thrive in relationships and life. I’ve written a series of posts about different conflict resolution skills, including how to apologize well.

When kids (or adults) are really mad, words and reactions can be ugly. The inability to calm down, self-regulate, and manage anger can have lasting negative effects, the most important of which can be an adulthood that lacks meaningful, sustained relationships. And since the people and relationships in our lives are the most important predictor of happiness and well-being, this is a high price to pay for not learning to control anger.

For children, this can manifest itself in a number of ways, but the primary consequence of angry reactions is social rejection. In other words, anger in children is a deterrent to friendships, and lack of peer support at a young age often leads to an absence of fulfilling relationships later in life. That’s why teaching our kids to regulate their emotions and learn how to calm down when angry are extremely important life skills.

Take a look at adults who have trouble managing anger and the damage it can cause in their lives and the lives of those close to them. Angry people cause others to feel upset, intimidated, and unloved, which in turn leaves the angry person feeling isolated and often miserable. This reminds us, then, of how important it is to help our kids learn to calm down in the midst of difficult situations. Because no matter how hard we might try to pave our child’s path (also not a good idea), they will most definitely encounter people and situations that bring up negative emotions like anger, frustration, and sadness. And our kids need to learn how to process those emotions in a productive way.

And our kids need to learn how to process those emotions in a productive way.

For kids with low self-regulation, processing emotions productively can be a real challenge. Most are quick to anger, over-reacting to small things like being on the losing end of a card game or misplacing a prized toy. Such children often perceive themselves as targets of other kids (even when they’re not). And even the kindest of kids can get annoyed at ones who have angry outbursts.

Modeling for Our Kids

Being aware of our own reactions to situations, and what we’re modeling for our kids, is important as we try to teach them how to calm down. Unfortunately (or fortunately, if you’re good at calming down), our kids are going to learn to respond to situations the same way we do. The worst coping mechanism I’ve utilized when I’m frustrated is sarcasm. I’m not a yeller, but I have often found myself making a sarcastic comment to my kids in response to something they’ve done (or not done) that’s bothered me. As soon as the words are out, I know I was wrong to say them. So, I, too, need to practice calming down before I respond to a situation. Teaching our kids ways to calm down, and practicing these techniques ourselves, is an important way we can help ensure better relationships and overall well-being for our kids (and ourselves).

As soon as the words are out, I know I was wrong to say them. So, I, too, need to practice calming down before I respond to a situation. Teaching our kids ways to calm down, and practicing these techniques ourselves, is an important way we can help ensure better relationships and overall well-being for our kids (and ourselves).

Never Problem Solve when Emotions are High

Especially in conflict situations, the people involved need to calm down before any talking or problem-solving can occur. Nothing useful comes from trying to lead a discussion with upset, emotionally fragile kids. So always gently help them figure out the best way to calm down before attempting to solve the problem. This goes for parents, too. If our child has done something that really makes us mad and requires some type of conversation or consequence, we need to step back and calm down before we respond, so that we can do so in a logical way that lets our child know we love them and that they will be held responsible for rectifying the situation or facing the consequences of their behavior.

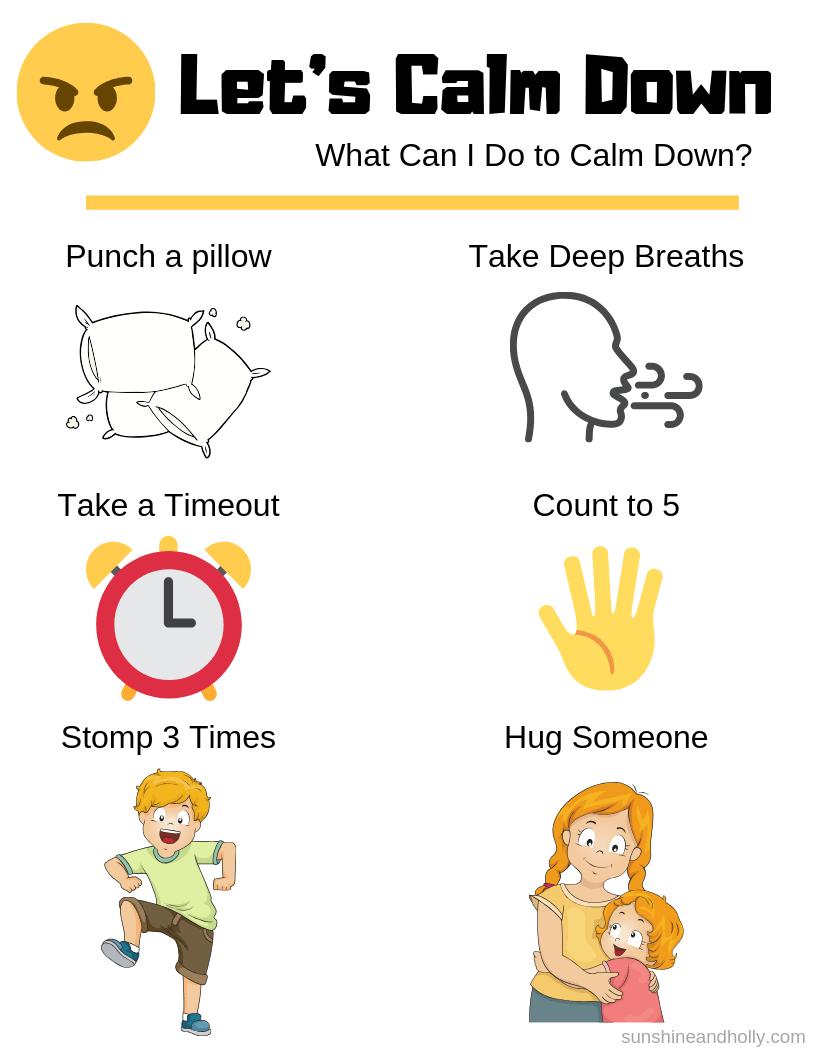

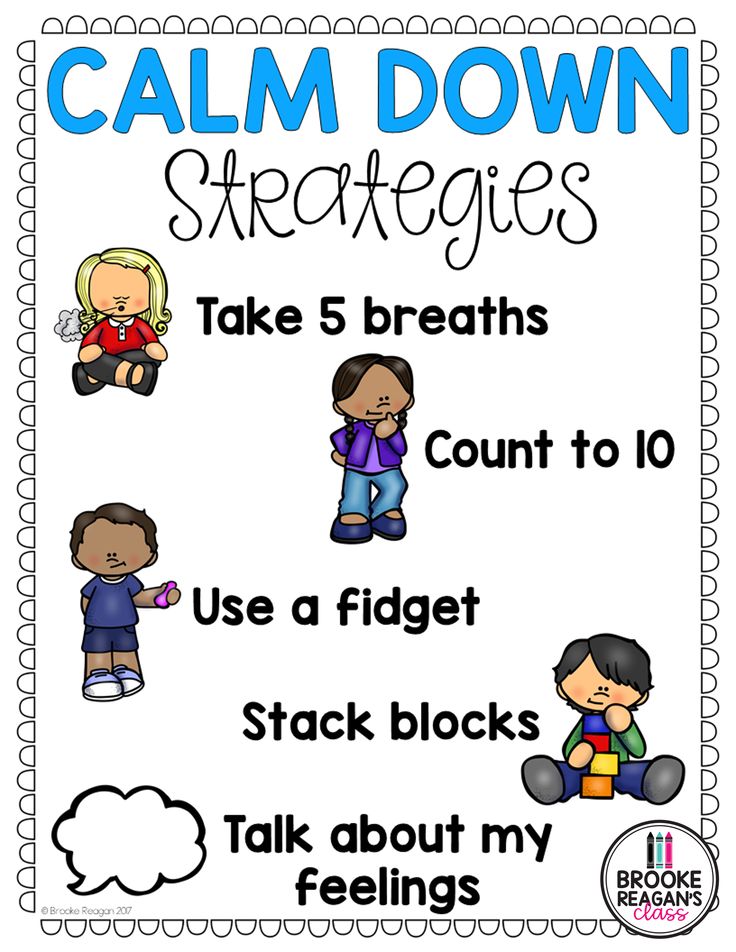

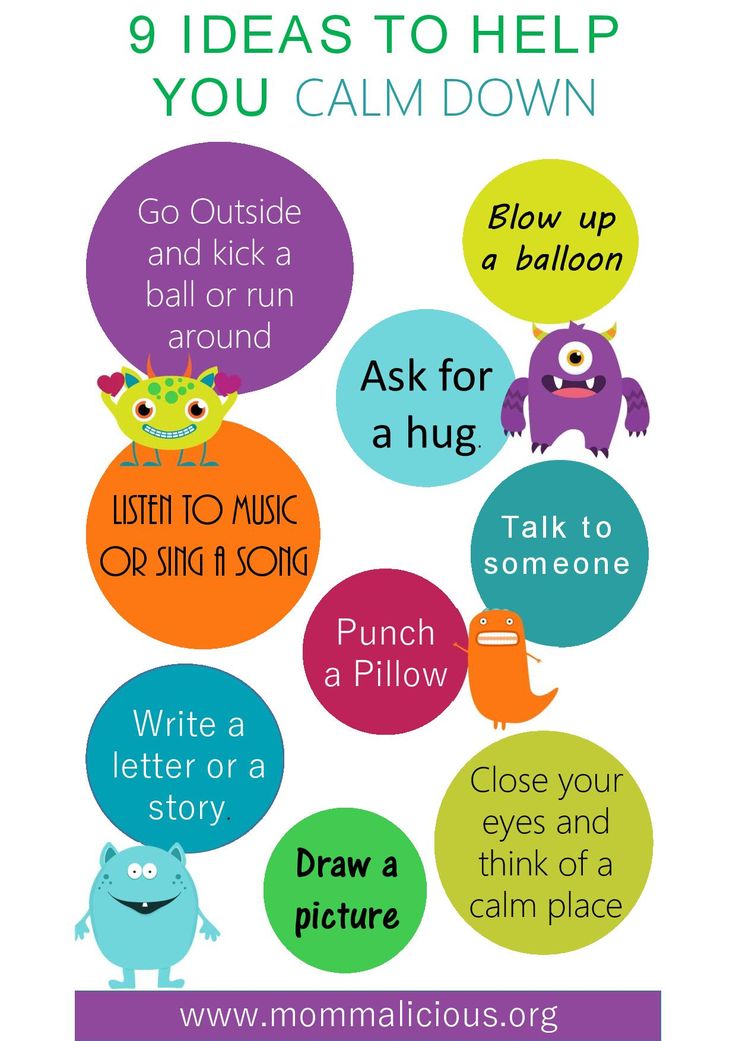

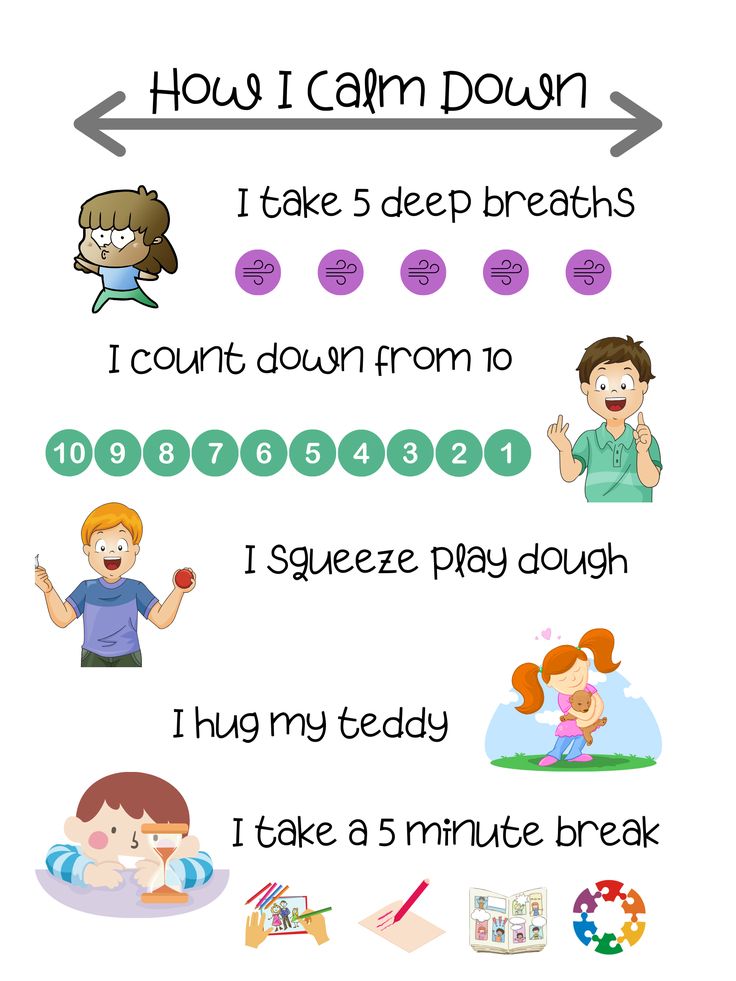

10 Ways to Calm Down

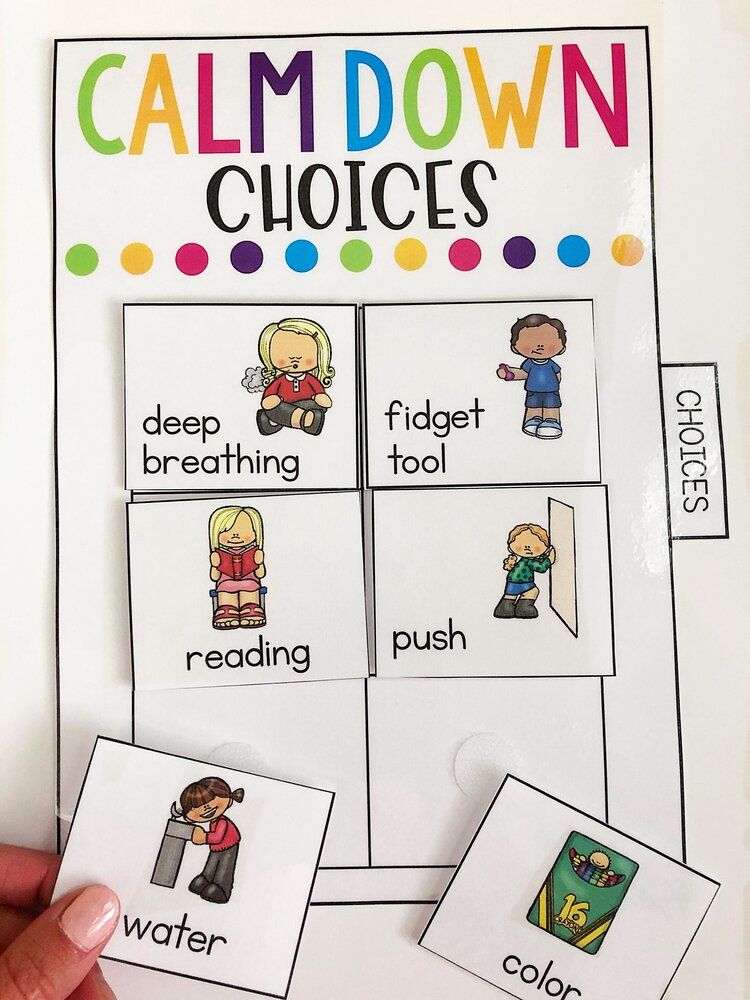

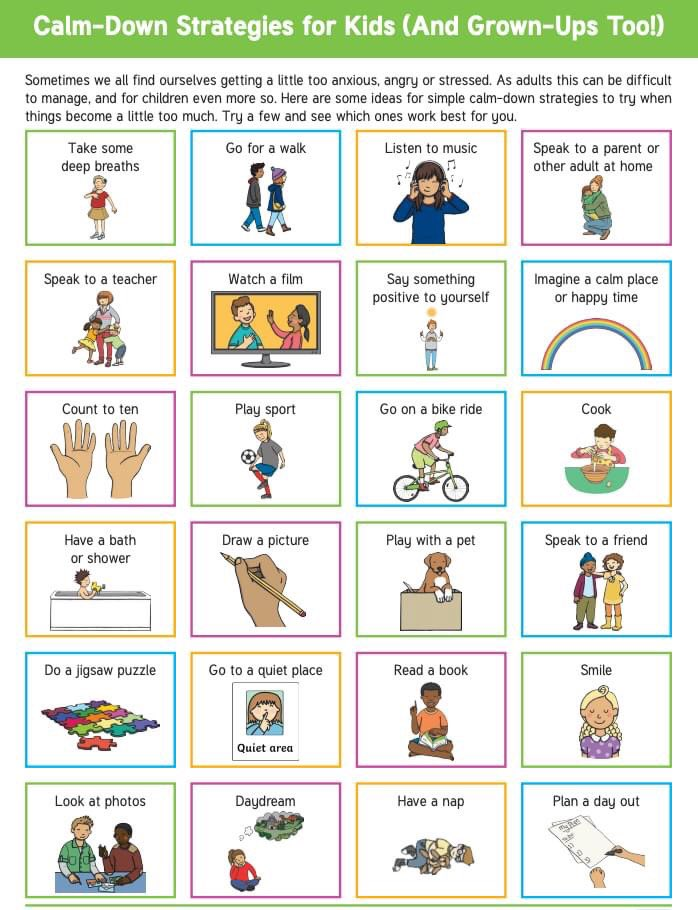

There are many ways people have found to calm down. Finding what works for you and helping your child learn what works for them may involve some trial and error. Think of it as an experiment in calming down, and tell your kid it’s an experiment, too. Start by saying something like this: “I’m trying to learn to calm down when I’m angry so I don’t say things I regret later. I’d love for you to practice with me, because I think it will help you with your friends at school.” Then, try one or more of these 10 ideas:

1. Go to a “chill spot”

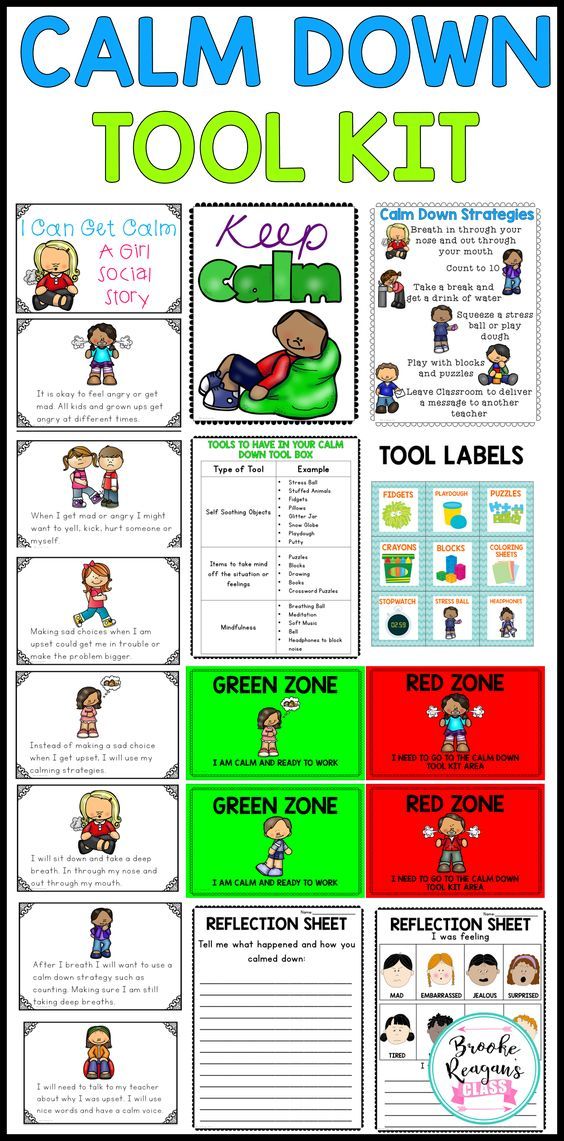

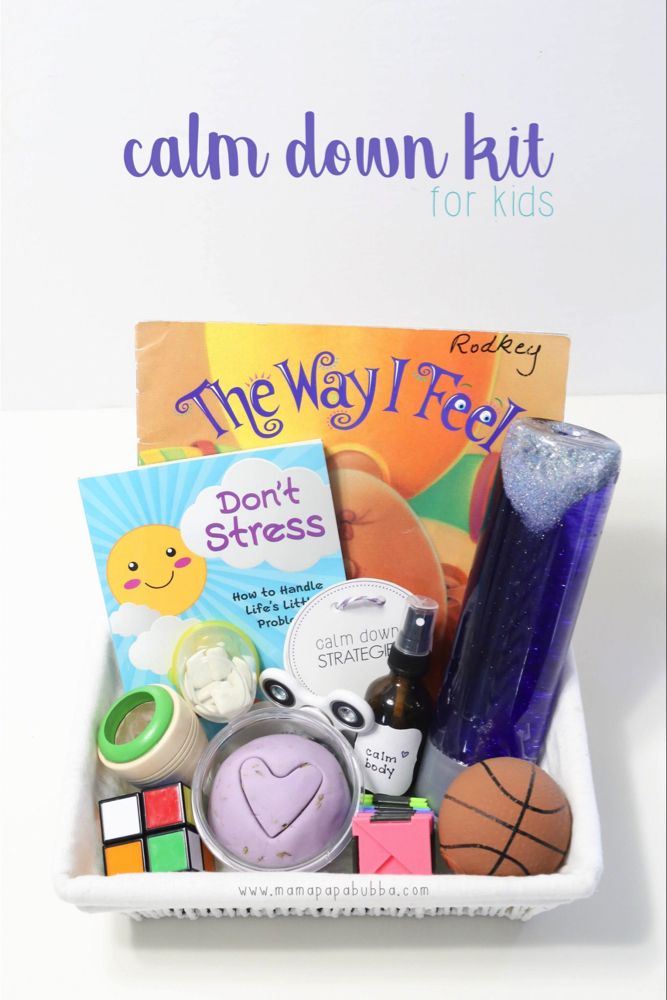

Instead of making the need to calm down a negative thing (like a “time out”), we can turn it into a positive by designating a place (or multiple places) where we go to calm down. We can call it a “chill spot” or whatever name sounds good, and it can be our bedroom or a patio chair outside or a comfy sofa in the living room. Talk about it when everyone is calm and explain what the “chill spot” is for. You and your child can share your respective “chill spots.” Remember to make it a pleasant spot (not the chair facing the corner in the garage). Maybe even set up some “chill” supplies at the designated spot (a book, coloring, or any other calming activities). The next time you’re having a stressful “moment” (if you’re like me, it will probably happen within the next day), model going to the chill spot yourself before you ask your child to use it. Before yelling or reacting in sarcasm or anger, just say, “I’m going to my chill spot for a few minutes. I need to calm down.” They will learn volumes from your modeling and probably look forward to their “chill spot” opportunities.

You and your child can share your respective “chill spots.” Remember to make it a pleasant spot (not the chair facing the corner in the garage). Maybe even set up some “chill” supplies at the designated spot (a book, coloring, or any other calming activities). The next time you’re having a stressful “moment” (if you’re like me, it will probably happen within the next day), model going to the chill spot yourself before you ask your child to use it. Before yelling or reacting in sarcasm or anger, just say, “I’m going to my chill spot for a few minutes. I need to calm down.” They will learn volumes from your modeling and probably look forward to their “chill spot” opportunities.

2. Go outside for a walk or run

Getting outside and getting some exercise are both great ways to calm down. Kids with ADHD who exercise for 10 minutes get more benefits than medication. This is a great activity to do together. I advise no talking for at least 5-10 minutes while walking or running, so that the calming can occur and the brain clears of cortisol and floods with endorphins.

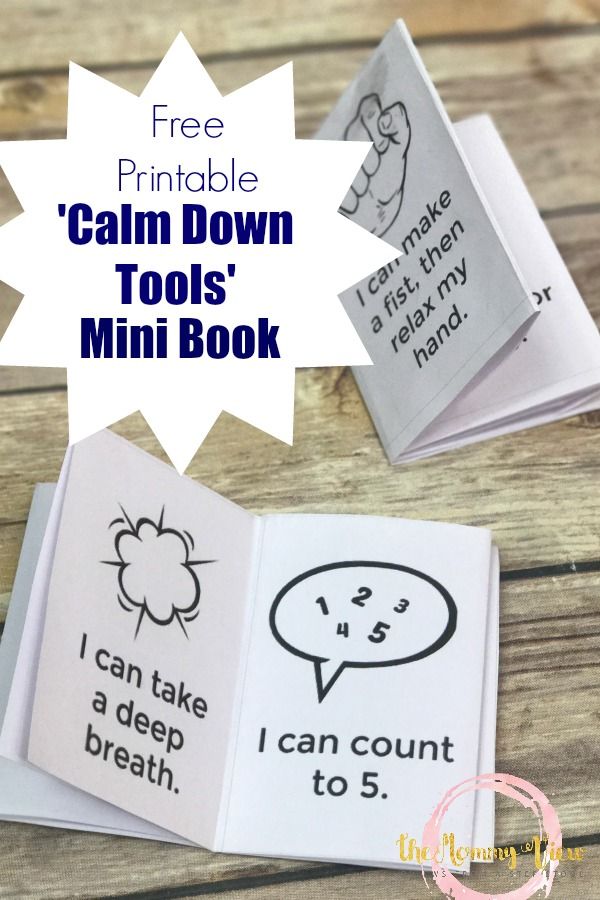

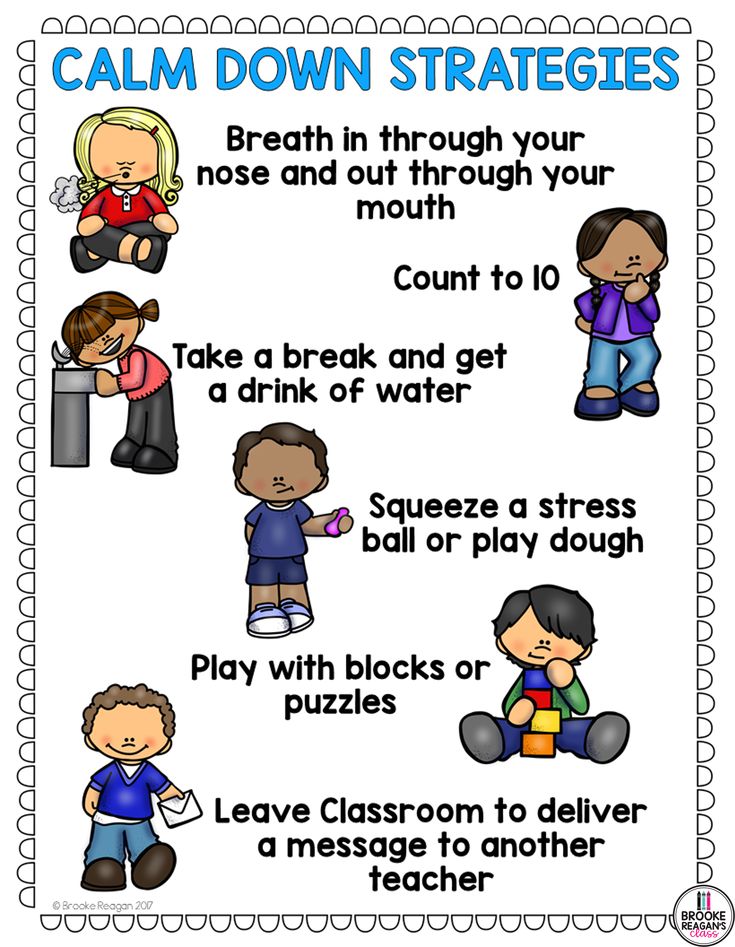

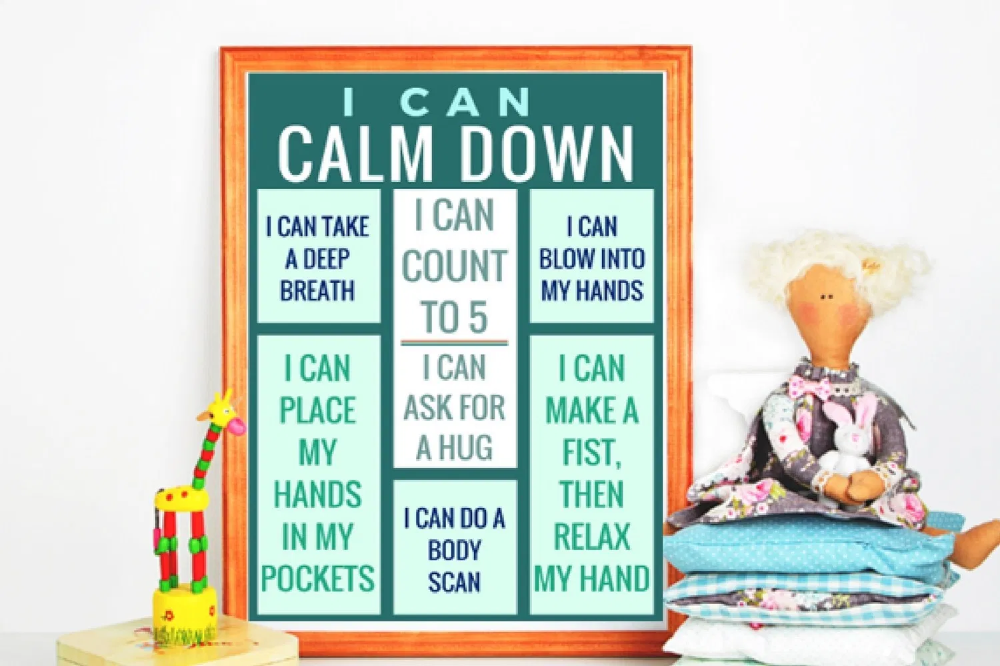

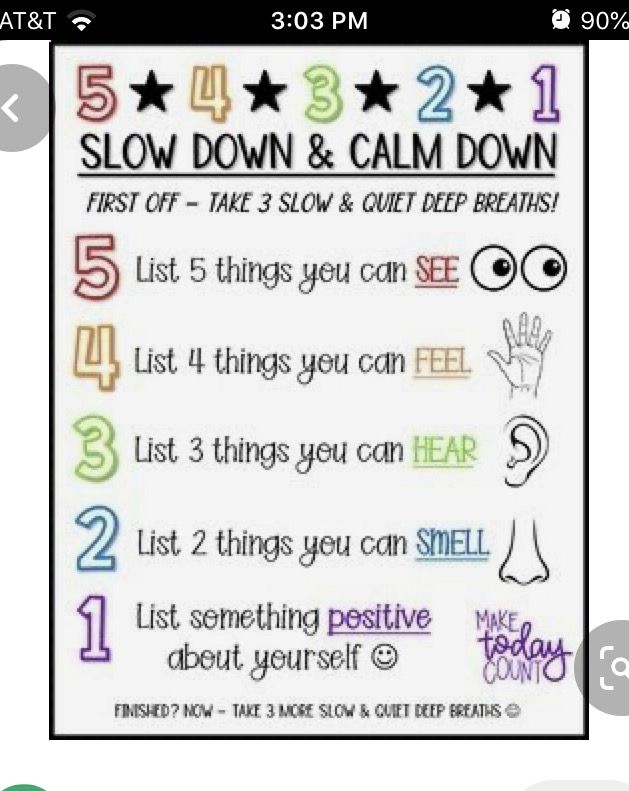

3. Take some deep breaths

I’ve been learning to breathe this year. When we’re upset, we tend to do a kind of shallow breathing that keeps us agitated and anxious. Slowing down our breathing can help our body physiologically calm down, which leads to a calmer mental state. Where the body goes, the mind follows. So, during the stress response caused by a negative situation or interaction, we really need to just breathe deeply for a little while. This can be standing up, sitting down, or lying down. Again, when talking with our kids about how breathing can help us calm down, we can practice together and find the “best position” for ourselves.

4. Count to 10 (or 100)

I do this sometimes in my head (not out loud). Just pausing before responding can help prevent things from coming out of the mouth that we later regret. Teaching our kids this skill can be a life changer.

5. Listen to some soothing music – (not angry music!)

Have a playlist handy on your phone that’s your happy/calming music. Have one for your child, too, if they’re young, or encourage them to create their own calming playlist

Have one for your child, too, if they’re young, or encourage them to create their own calming playlist

6. Think of something you’re grateful for

Any gratitude practice can help you calm down, because you can’t hold the two physiological/mental states of anger and gratitude at the same time. If you jot down a note of a few things you’re grateful for or pen a thank you letter, you’ll feel much more calm after.

7. Look at a funny meme or video

I keep a Pinterest board of funny things (maybe only to me!). Again, if you can laugh you’ll offset the negative emotions and be able to calm down. Plus, a hearty belly laugh is just good in general.

8. Hug

This is a simple thing that might be appealing to your child as a way to calm down. Holding them still and breathing with them, while giving a loving hug, can help them calm down.

9. Loosen up

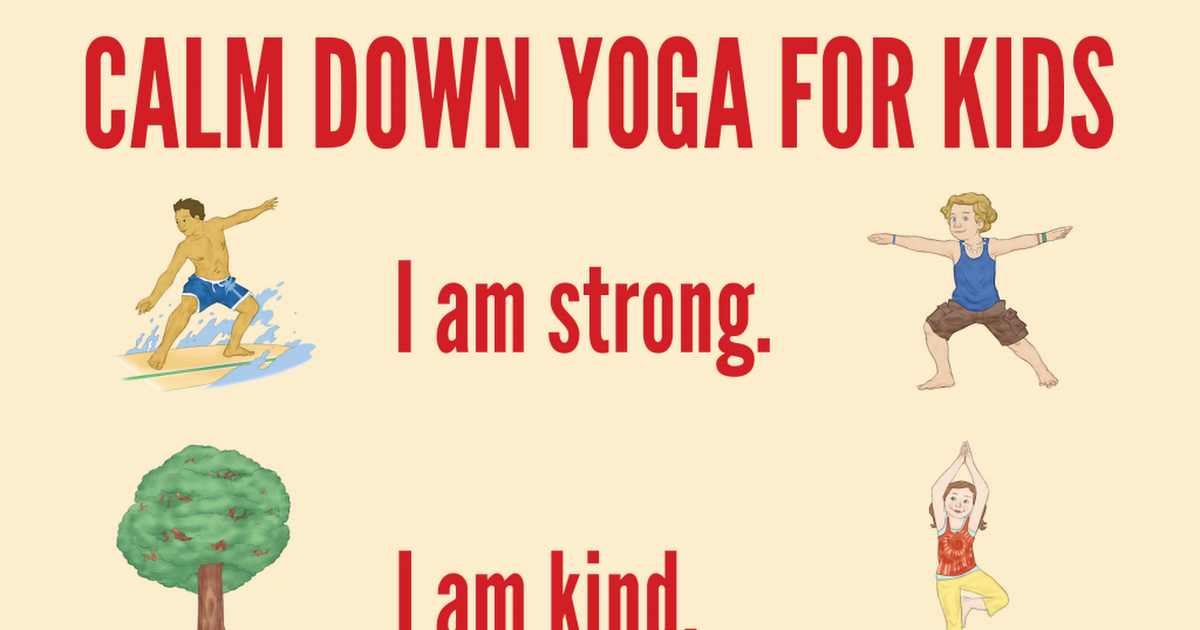

Stretch or do a yoga pose like “child’s pose” or, my personal favorite, “corpse.” Doing these things can help you breathe and bring a calmness to your body that will reverberate in your mind.

10. Sit quietly and have a drink of water, cup of tea, or piece of fruit

This could be part of going to the chill spot, or it can be its own calming technique. Just sitting quietly and sipping a cup of water is a way to extricate from whatever stressful encounter or situation is at hand.

Empower your child to figure out what works best for him/her to calm down. And continue practicing together. The valuable life skill of being able to calm down will lead to better relationships and success, at home and at work, throughout your child’s life.

You can read more in my posts Five Steps to Help Kids Resolve Conflicts and More Than “I’m Sorry” – Teaching Kids to Apologize Well.

Resources

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/exercise-seems-to-be-beneficial-to-children/380844/

Posted by Audrey Monke

in

Friendship & Social Skills

WANT TO SOOTH A CRYING BABY? TAKE IT DOWN

Topic of the day

- home

- society

November 03, 2000, 00:00 print Issue No. 43, November 3-November 10, 2000

Not so long ago, one of the capital's newspapers told a terrible story: a twenty-year-old mother, not knowing how to calm her two-month-old daughter, hit her with her fist. ..

..

- MIRROR OF THE WEEK, UKRAINE Room archive | Latest Articles < >

-

"War and theft". Who and why seizes the agricultural lands of Ukraine? The price of the issue is the loss of economic independence Reader Survey

Author Inna Vedernikova Article March 28 08:30

-

Three goals of Putin: why does he need nuclear weapons in Belarus The Kremlin continues to play to raise rates Reader Survey

Author Vladimir Kravchenko Article March 27 14:43

-

Ocean Plaza Rotenberg.

How the asset was confiscated and why it matters Formal change of shareholders is not an option infographics Reader Survey

How the asset was confiscated and why it matters Formal change of shareholders is not an option infographics Reader Survey Author Alexander Lemenov Article March 27 08:32

-

Postal voting. How does this system work and could it work in Ukraine Experiment from the Civic Network OPORA Reader Survey

Author Yury Lisovsky Article March 26 17:00

-

industrial parks.

Minimum progress in ten years Will the implementation of the adopted strategy affect their development? Reader Survey

Minimum progress in ten years Will the implementation of the adopted strategy affect their development? Reader Survey Author Evgeny Cherny Article March 26 13:01

-

Pension-2023: to whom exactly, how and how much Occupation or going abroad does not stop pension accruals Reader Survey

Author Tatyana Kirilenko Article March 26 08:49

-

- You will also be interested >

-

War and love Reader Survey 12.

02 17:00

02 17:00 -

Kherson: freedom under artillery fire Reader Survey 12.02 15:00

-

Abuse and war Reader Survey 12.02 08:35

-

Dogs of War: Rescue the Living, Find the Dead 09.02 12:30

-

Military doctor Yurik Mkrtchyan about 206 days of Russian captivity: “They beat you - you take a hit.

The main thing is not to embarrass yourself in front of yourself. 06.02 13:00

The main thing is not to embarrass yourself in front of yourself. 06.02 13:00 -

Is this just entertainment? Reader Survey 05.02 08:35

-

75 years without Gandhi Reader Survey 08:30

-

Dnipro. Big hole in the heart 25.

01 13:02

01 13:02 -

Psychology of conspiracy theories 24.01 17:00

-

It is possible to return from the Russian “evacuation”: what needs to be done now for this Reader Survey 01/22 08:35

-

Not only humanitarian aid Reader Survey 17.

01 17:02

01 17:02 -

Life after mom. “Vlad almost every day brought sweets to his mother’s grave” 17.01 08:30

-

Latest news

- The expert explained how the Easter basket could rise in price in 2023 10:00

- Putin decided to deploy nuclear weapons in Belarus because he did not get what he wanted from Xi - Zelensky 09:53

- The military will defend Bakhmut as long as it is necessary for us in terms of fulfilling military defense tasks - Malyar 09:47

- Society will feel tired and will tend to compromise - Zelensky on the risks of Bakhmut's fall 09:32

- Zelensky invites Chinese leader to Ukraine 09:04

All news

Welcome! Registration Password recovery Log in to be able to comment on content Register to be able to comment on materials Enter the email address you registered with and a password will be sent to it

Forgot your password? To come in

The password can contain uppercase and lowercase Latin letters, as well as numbers The entered e-mail contains errors

Register

Name and surname must consist of letters of the Latin alphabet or Cyrillic The entered e-mail contains errors This email already exists The First and last name field has no errors Email field has no errors

Remind password

The e-mail entered contains errors

No account? Register! Already registered? Sign in! Don't have an account? Register!

Benefits and harms of the usual phrase "Calm down"

In our daily life we often hear someone say "Calm down". Sometimes, it is pronounced in different situations, with different messages and different intonations.

Sometimes, it is pronounced in different situations, with different messages and different intonations.

Let's discuss such situations from a psychological point of view, when this phrase is spoken to the child by the parents.

For example, a mother with a baby is walking down the street. The child is crying and upset about something. Sometimes he practically screams, sometimes he cries bitterly. In response, mom can quite sharply say “Stop! Calm down!"

At such a moment one can sympathize with the child. Since he remains unheard by his mother. The child feels rejected, not needed, not important and not loved.

These tears indicate that the baby needs something from the mother (we are not talking about something material, but about being understood and heard), but the mother (for some reason) cannot give him this.

Does this phrase help the child calm down?

Child psychologists recommend remembering yourself in similar situations. Everyone, for sure, sometime in his life faced with something like this, this happens quite often, in childhood and in adulthood. Did this phrase make you feel really calmer? Agree, it's unlikely.

Did this phrase make you feel really calmer? Agree, it's unlikely.

What did you need at that moment?

At such a moment when we experience any experience, we need to understand that we are being heard and perhaps even understood. It is important for us to know that the person next to us sympathizes with what is happening to us, that our condition is not indifferent to others, that we are not alone with our problem.

So why is the phrase "Calm down" commonly said?

This is most likely due to the fact that our parents did the same with them. For the reason that we are accustomed to say so. Because the parents never thought about the consequences of the words she said. But if you notice this in relationships with your child, then this habitual behavior can be changed.

What can actually help a child calm down?

It is important for the child to say that you sympathize with him. You're sorry this is happening. That you cannot buy something for him, for example.

You can say something like this to a child: “I hear you and understand that you want sweets. But eating a lot of sweets is harmful. And I don't want to hurt you. I'm very sorry this is happening. I'm sorry this makes you upset. Let's come up with something instead of sweets?

There are also situations when an adult says with sympathy to a screaming, crying baby: "Calm down." Does this phrase help with the message to sympathizers?

If you remember yourself in such a situation, you will probably agree that this phrase in itself did nothing to help you feel calmer. And your experiences remain the same as they were.

What will help a child in such a situation?

It will also help if you let your child know that you hear him and share his feelings with him. This support and acceptance will help your baby feel better and calm down.

Seeing your acceptance and sympathy, the baby learns to do the same towards you and towards other people.

What about the situation when, for example, mother is tired, angry or irritated? You can say about your condition, for example: “Today I am very tired (angry, upset, etc.