Children doing maths

Math Skills and Milestones by Age

Kids start learning math the moment they start exploring the world. Each skill — from identifying shapes to counting to finding patterns — builds on what they already know.

There are certain math milestones most kids hit at roughly the same age. But keep in mind that kids develop math skills at different rates. If kids don’t yet have all the skills listed for their age group, that’s OK.

Here’s how math skills typically develop as kids get older.

Babies (ages 0–12 months)

- Begin to predict the sequence of events (like running water means bath time)

- Start to understand basic cause and effect (shaking a rattle makes noise)

- Begin to classify things in simple ways (some toys make noise and others don’t)

- Start to understand relative size (baby is small, parents are big)

- Begin to understand words that describe quantities (more, bigger, enough)

Toddlers (ages 1–2 years)

- Understand that numbers mean “how many” (using fingers to show how many years old they are)

- Begin reciting numbers, but may skip some of them

- Understand words that compare or measure things (under, behind, faster)

- Match basic shapes (triangle to triangle, circle to circle)

- Explore measurement by filling and emptying containers

- Start seeing patterns in daily routines and in things like floor tiles

Preschoolers (ages 3–4 years)

- Recognize shapes in the real world

- Start sorting things by color, shape, size, or purpose

- Compare and contrast using classifications like height, size, or gender

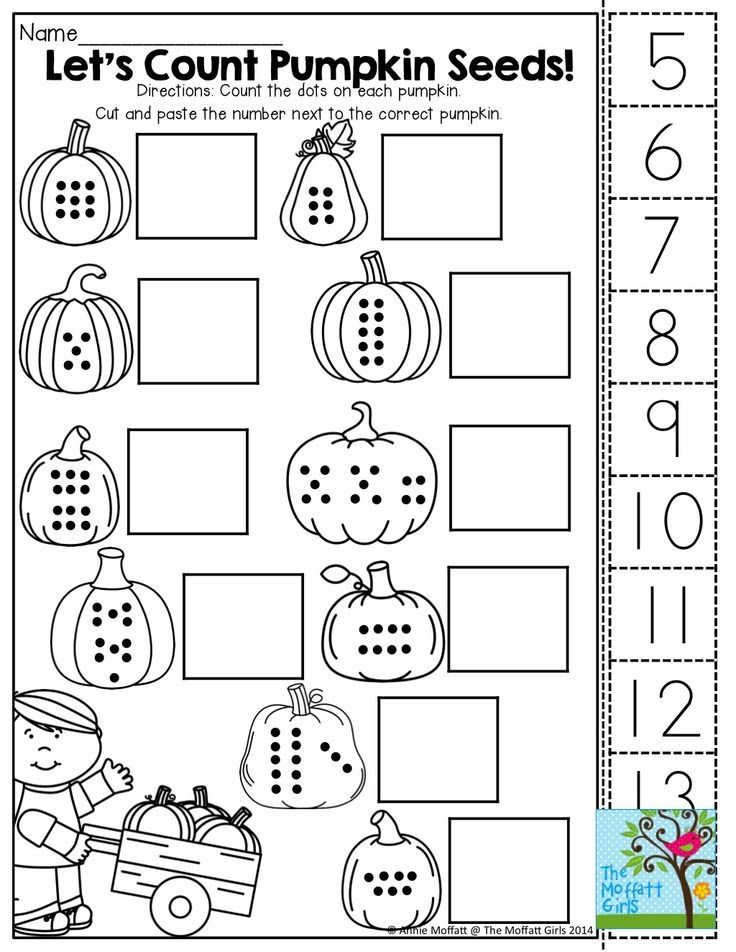

- Count up to at least 20 and accurately point to and count items in a group

- Understand that numerals stand for number names (5 stands for five)

- Use spatial awareness to put puzzles together

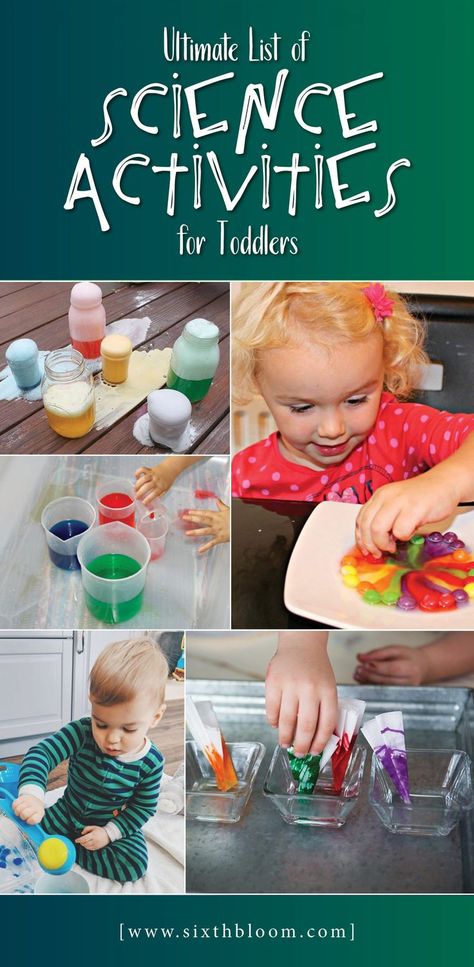

- Start predicting cause and effect (like what will happen if they drop a toy in a tub full of water)

Kindergartners (age 5 years)

- Add by counting the fingers on one hand — 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 — and starting with 6 on the second hand

- Identify the larger of two numbers and recognize numerals up to 20

- Copy or draw symmetrical shapes

- Start using very basic maps to find a “hidden treasure”

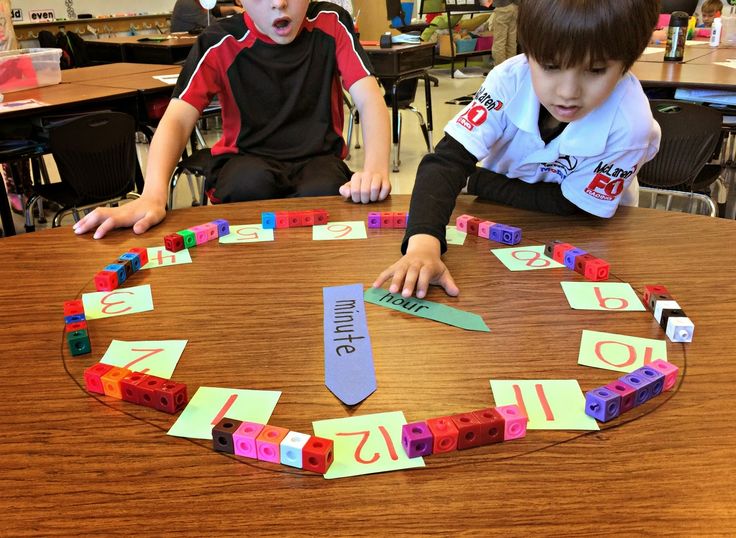

- Begin to understand basic time concepts, like morning or days of the week

- Follow multi-step directions that use words like first and next

- Understand the meaning of words like unlikely or possible

First and second graders

- Predict what comes next in a pattern and create own patterns

- Know the difference between two- and three-dimensional shapes and name the basic ones (cubes, cones, cylinders)

- Count to 100 by ones, twos, fives, and tens

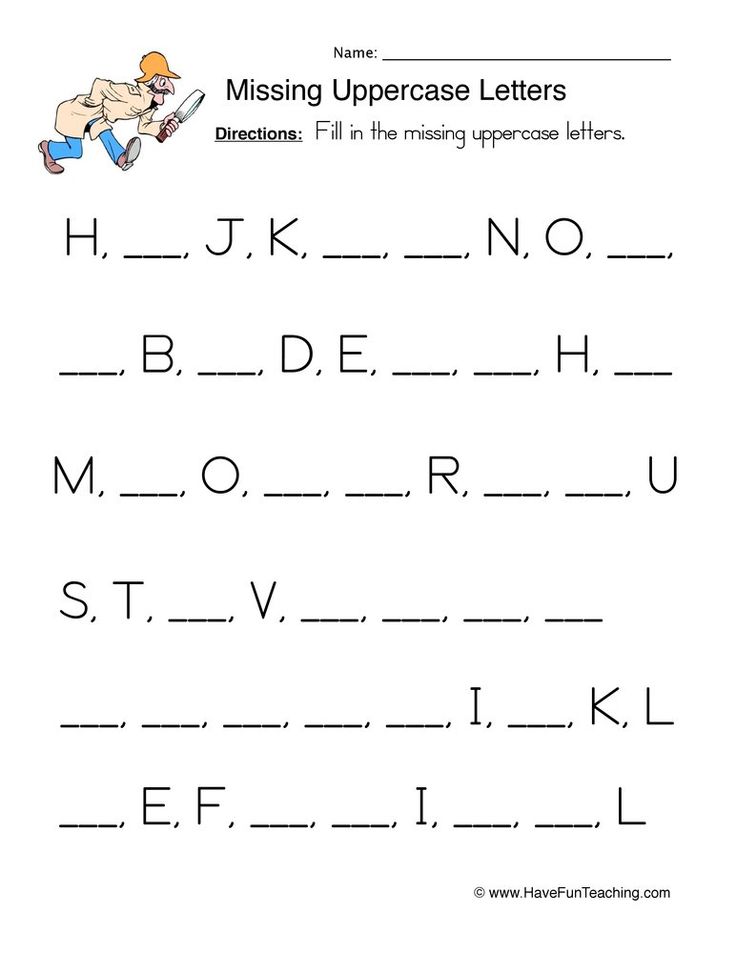

- Write and recognize the numerals 0 to 100, and the words for numbers from one to twenty

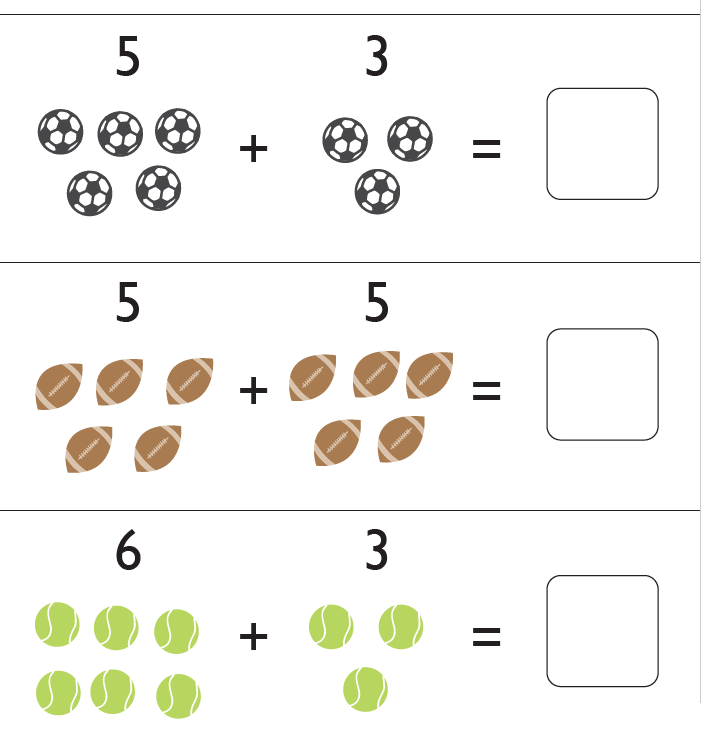

- Do basic addition and subtraction up to 20

- Read and create a simple bar graph

- Recognize and know the value of coins

Third graders

- Move from using hands-on methods to using paper and pencil to work out math problems

- Work with money

- Do addition and subtraction with regrouping (also known as borrowing)

- Understand place value well enough to solve problems with decimal points

- Know how to do multiplication and division, with help from fact families (collections of related math facts, like 3 × 4 = 12 and 4 × 3 = 12)

- Create a number sentence or equation from a word problem

Fourth and fifth graders

- Start applying math concepts to the real world (like cutting a recipe in half)

- Practice using more than one way to solve problems

- Write and compare fractions and decimals and put them in order on a number line

- Compare numbers using > (greater than) and < (less than)

- Start two- and three-digit multiplication (like 312 × 23)

- Complete long division, with or without remainders

- Estimate and round

Middle-schoolers

- Begin basic algebra with one unknown number (like 2 + x = 10)

- Use coordinates to locate points on a grid, also known as graphing ordered pairs

- Work with fractions, percentages, and proportions

- Work with lines, angles, types of triangles, and other basic geometric shapes

- Use formulas to solve complicated problems and to find the area, perimeter, and volume of shapes

High-schoolers

- Understand that numbers can be represented in many ways (fractions, decimals, bases, and variables)

- Use numbers in real-life situations (like calculating a sale price or comparing student loans)

- Begin to see how math ideas build on one another

- Begin to understand that some math problems don’t have real-world solutions

- Use mathematical language to convey thoughts and solutions

- Use graphs, maps, or other representations to learn and convey information

Remember that kids develop at different paces. Some may gain some math skills later than other kids or have some that are advanced for their age.

If you're concerned about progress in math, find out why some kids have trouble with math, and next steps to take.

Related topics

Help Your Child Develop Early Math Skills

Before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. Learn what informal activities give children a head start on early math skills when they start school.

Children are using early math skills throughout their daily routines and activities. This is good news as these skills are important for being ready for school. But early math doesn’t mean taking out the calculator during playtime. Even before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. For example, Thomas has two cars; Joseph wants one. After Thomas shares one, he sees that he has one car left (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001, p. 201). Other math skills are introduced through daily routines you share with your child—counting steps as you go up or down, for example. Informal activities like this one give children a jumpstart on the formal math instruction that starts in school.

After Thomas shares one, he sees that he has one car left (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001, p. 201). Other math skills are introduced through daily routines you share with your child—counting steps as you go up or down, for example. Informal activities like this one give children a jumpstart on the formal math instruction that starts in school.

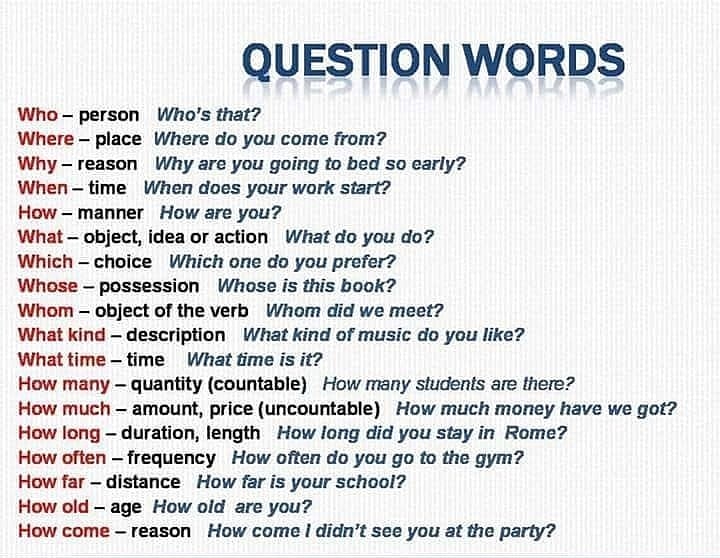

What math knowledge will your child need later on in elementary school? Early mathematical concepts and skills that first-grade mathematics curriculum builds on include: (Bowman et al., 2001, p. 76).

- Understanding size, shape, and patterns

- Ability to count verbally (first forward, then backward)

- Recognizing numerals

- Identifying more and less of a quantity

- Understanding one-to-one correspondence (i.e., matching sets, or knowing which group has four and which has five)

Key Math Skills for School

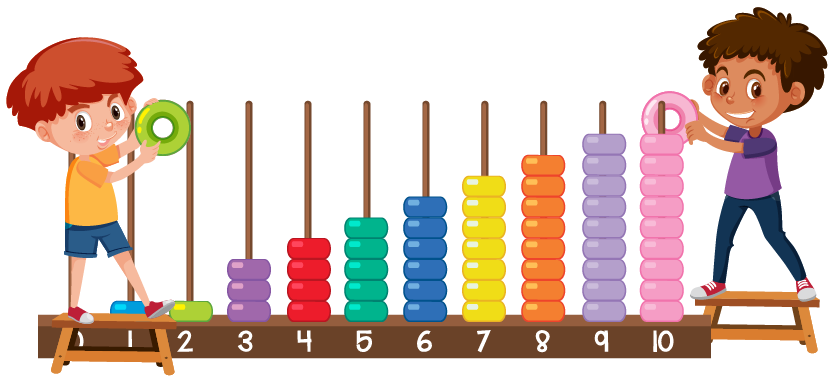

More advanced mathematical skills are based on an early math “foundation”—just like a house is built on a strong foundation. In the toddler years, you can help your child begin to develop early math skills by introducing ideas like: (From Diezmann & Yelland, 2000, and Fromboluti & Rinck, 1999.)

In the toddler years, you can help your child begin to develop early math skills by introducing ideas like: (From Diezmann & Yelland, 2000, and Fromboluti & Rinck, 1999.)

Number Sense

This is the ability to count accurately—first forward. Then, later in school, children will learn to count backwards. A more complex skill related to number sense is the ability to see relationships between numbers—like adding and subtracting. Ben (age 2) saw the cupcakes on the plate. He counted with his dad: “One, two, three, four, five, six…”

Representation

Making mathematical ideas “real” by using words, pictures, symbols, and objects (like blocks). Casey (aged 3) was setting out a pretend picnic. He carefully laid out four plastic plates and four plastic cups: “So our whole family can come to the picnic!” There were four members in his family; he was able to apply this information to the number of plates and cups he chose.

Spatial sense

Later in school, children will call this “geometry. ” But for toddlers it is introducing the ideas of shape, size, space, position, direction and movement. Aziz (28 months) was giggling at the bottom of the slide. “What’s so funny?” his Auntie wondered. “I comed up,” said Aziz, “Then I comed down!”

” But for toddlers it is introducing the ideas of shape, size, space, position, direction and movement. Aziz (28 months) was giggling at the bottom of the slide. “What’s so funny?” his Auntie wondered. “I comed up,” said Aziz, “Then I comed down!”

Measurement

Technically, this is finding the length, height, and weight of an object using units like inches, feet or pounds. Measurement of time (in minutes, for example) also falls under this skill area. Gabriella (36 months) asked her Abuela again and again: “Make cookies? Me do it!” Her Abuela showed her how to fill the measuring cup with sugar. “We need two cups, Gabi. Fill it up once and put it in the bowl, then fill it up again.”

Estimation

This is the ability to make a good guess about the amount or size of something. This is very difficult for young children to do. You can help them by showing them the meaning of words like more, less, bigger, smaller, more than, less than. Nolan (30 months) looked at the two bagels: one was a regular bagel, one was a mini-bagel. His dad asked: “Which one would you like?” Nolan pointed to the regular bagel. His dad said, “You must be hungry! That bagel is bigger. That bagel is smaller. Okay, I’ll give you the bigger one. Breakfast is coming up!”

His dad asked: “Which one would you like?” Nolan pointed to the regular bagel. His dad said, “You must be hungry! That bagel is bigger. That bagel is smaller. Okay, I’ll give you the bigger one. Breakfast is coming up!”

Patterns

Patterns are things—numbers, shapes, images—that repeat in a logical way. Patterns help children learn to make predictions, to understand what comes next, to make logical connections, and to use reasoning skills. Ava (27 months) pointed to the moon: “Moon. Sun go night-night.” Her grandfather picked her up, “Yes, little Ava. In the morning, the sun comes out and the moon goes away. At night, the sun goes to sleep and the moon comes out to play. But it’s time for Ava to go to sleep now, just like the sun.”

Problem-solving

The ability to think through a problem, to recognize there is more than one path to the answer. It means using past knowledge and logical thinking skills to find an answer. Carl (15 months old) looked at the shape-sorter—a plastic drum with 3 holes in the top. The holes were in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square. Carl looked at the chunky shapes on the floor. He picked up a triangle. He put it in his month, then banged it on the floor. He touched the edges with his fingers. Then he tried to stuff it in each of the holes of the new toy. Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

The holes were in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square. Carl looked at the chunky shapes on the floor. He picked up a triangle. He put it in his month, then banged it on the floor. He touched the edges with his fingers. Then he tried to stuff it in each of the holes of the new toy. Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

Math: One Part of the Whole

Math skills are just one part of a larger web of skills that children are developing in the early years—including language skills, physical skills, and social skills. Each of these skill areas is dependent on and influences the others.

Trina (18 months old) was stacking blocks. She had put two square blocks on top of one another, then a triangle block on top of that. She discovered that no more blocks would balance on top of the triangle-shaped block. She looked up at her dad and showed him the block she couldn’t get to stay on top, essentially telling him with her gesture, “Dad, I need help figuring this out. ” Her father showed her that if she took the triangle block off and used a square one instead, she could stack more on top. She then added two more blocks to her tower before proudly showing her creation to her dad: “Dada, Ook! Ook!”

” Her father showed her that if she took the triangle block off and used a square one instead, she could stack more on top. She then added two more blocks to her tower before proudly showing her creation to her dad: “Dada, Ook! Ook!”

You can see in this ordinary interaction how all areas of Trina’s development are working together. Her physical ability allows her to manipulate the blocks and use her thinking skills to execute her plan to make a tower. She uses her language and social skills as she asks her father for help. Her effective communication allows Dad to respond and provide the helps she needs (further enhancing her social skills as she sees herself as important and a good communicator). This then further builds her thinking skills as she learns how to solve the problem of making the tower taller.

What You Can Do

The tips below highlight ways that you can help your child learn early math skills by building on their natural curiosity and having fun together. (Note: Most of these tips are designed for older children—ages 2–3. Younger children can be exposed to stories and songs using repetition, rhymes and numbers.)

(Note: Most of these tips are designed for older children—ages 2–3. Younger children can be exposed to stories and songs using repetition, rhymes and numbers.)

Shape up.

Play with shape-sorters. Talk with your child about each shape—count the sides, describe the colors. Make your own shapes by cutting large shapes out of colored construction paper. Ask your child to “hop on the circle” or “jump on the red shape.”

Count and sort.

Gather together a basket of small toys, shells, pebbles or buttons. Count them with your child. Sort them based on size, color, or what they do (i.e., all the cars in one pile, all the animals in another).

Place the call.

With your 3-year-old, begin teaching her the address and phone number of your home. Talk with your child about how each house has a number, and how their house or apartment is one of a series, each with its own number.

What size is it?

Notice the sizes of objects in the world around you: That pink pocketbook is the biggest. The blue pocketbook is the smallest. Ask your child to think about his own size relative to other objects (“Do you fit under the table? Under the chair?”).

The blue pocketbook is the smallest. Ask your child to think about his own size relative to other objects (“Do you fit under the table? Under the chair?”).

You’re cookin’ now!

Even young children can help fill, stir, and pour. Through these activities, children learn, quite naturally, to count, measure, add, and estimate.

Walk it off.

Taking a walk gives children many opportunities to compare (which stone is bigger?), assess (how many acorns did we find?), note similarities and differences (does the duck have fur like the bunny does?) and categorize (see if you can find some red leaves). You can also talk about size (by taking big and little steps), estimate distance (is the park close to our house or far away?), and practice counting (let’s count how many steps until we get to the corner).

Picture time.

Use an hourglass, stopwatch, or timer to time short (1–3 minute) activities. This helps children develop a sense of time and to understand that some things take longer than others.

Shape up.

Point out the different shapes and colors you see during the day. On a walk, you may see a triangle-shaped sign that’s yellow. Inside a store you may see a rectangle-shaped sign that’s red.

Read and sing your numbers.

Sing songs that rhyme, repeat, or have numbers in them. Songs reinforce patterns (which is a math skill as well). They also are fun ways to practice language and foster social skills like cooperation.

Start today.

Use a calendar to talk about the date, the day of the week, and the weather. Calendars reinforce counting, sequences, and patterns. Build logical thinking skills by talking about cold weather and asking your child: What do we wear when it’s cold? This encourages your child to make the link between cold weather and warm clothing.

Pass it around.

Ask for your child’s help in distributing items like snacks or in laying napkins out on the dinner table. Help him give one cracker to each child. This helps children understand one-to-one correspondence. When you are distributing items, emphasize the number concept: “One for you, one for me, one for Daddy.” Or, “We are putting on our shoes: One, two.”

When you are distributing items, emphasize the number concept: “One for you, one for me, one for Daddy.” Or, “We are putting on our shoes: One, two.”

Big on blocks.

Give your child the chance to play with wooden blocks, plastic interlocking blocks, empty boxes, milk cartons, etc. Stacking and manipulating these toys help children learn about shapes and the relationships between shapes (e.g., two triangles make a square). Nesting boxes and cups for younger children help them understand the relationship between different sized objects.

Tunnel time.

Open a large cardboard box at each end to turn it into a tunnel. This helps children understand where their body is in space and in relation to other objects.

The long and the short of it.

Cut a few (3–5) pieces of ribbon, yarn or paper in different lengths. Talk about ideas like long and short. With your child, put in order of longest to shortest.

Learn through touch.

Cut shapes—circle, square, triangle—out of sturdy cardboard. Let your child touch the shape with her eyes open and then closed.

Let your child touch the shape with her eyes open and then closed.

Pattern play.

Have fun with patterns by letting children arrange dry macaroni, chunky beads, different types of dry cereal, or pieces of paper in different patterns or designs. Supervise your child carefully during this activity to prevent choking, and put away all items when you are done.

Laundry learning.

Make household jobs fun. As you sort the laundry, ask your child to make a pile of shirts and a pile of socks. Ask him which pile is the bigger (estimation). Together, count how many shirts. See if he can make pairs of socks: Can you take two socks out and put them in their own pile? (Don’t worry if they don’t match! This activity is more about counting than matching.)

Playground math.

As your child plays, make comparisons based on height (high/low), position (over/under), or size (big/little).

Dress for math success.

Ask your child to pick out a shirt for the day. Ask: What color is your shirt? Yes, yellow. Can you find something in your room that is also yellow? As your child nears three and beyond, notice patterns in his clothing—like stripes, colors, shapes, or pictures: I see a pattern on your shirt. There are stripes that go red, blue, red, blue. Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

Ask: What color is your shirt? Yes, yellow. Can you find something in your room that is also yellow? As your child nears three and beyond, notice patterns in his clothing—like stripes, colors, shapes, or pictures: I see a pattern on your shirt. There are stripes that go red, blue, red, blue. Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

Graphing games.

As your child nears three and beyond, make a chart where your child can put a sticker each time it rains or each time it is sunny. At the end of a week, you can estimate together which column has more or less stickers, and count how many to be sure.

References

Bowman, B.T., Donovan, M.S., & Burns, M.S., (Eds.). (2001). Eager to learn: Educating our preschoolers. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Diezmann, C., & Yelland, N. J. (2000). Developing mathematical literacy in the early childhood years. In Yelland, N.J. (Ed.), Promoting meaningful learning: Innovations in educating early childhood professionals. (pp.47–58). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

(pp.47–58). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Fromboluti, C. S., & Rinck, N. (1999 June). Early childhood: Where learning begins. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, National Institute on Early Childhood Development and Education. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/EarlyMath/title.html

At what age to start doing mathematics

Game teacher Zhenya Katz tells why it makes no sense to go to a mathematical circle before the age of four. And explains what the connection is between math and role-playing.

Very often parents ask me: at what age should I start teaching mathematics with children? I usually answer that in my groups children are engaged from the age of four. But sometimes I want to ask, what do you mean by "doing math"? Sit down at the table and solve examples in a notebook? This can be done from the age when the child himself becomes interested.

The child begins to "mathematics" from infancy. Further-closer, more-less - these are mathematical concepts. And the child masters them when he starts to stretch, grab, crawl, walk. The simplest - here it is, a toy, stretched, oh no, stretched some more - and crawled. Here she is, mother next to me. I hold on to a chair, reach for my mother, oh no, I reach for more, I fall, oh no, I don’t fall, and now my mother is hugging me, and here it is the first step. The first step on all fours, the first step on two legs, the joy and pride of parents.

The child's brain analyzes a huge amount of information from its actions and from the sensations of the body, from the result. So the brain makes a conclusion about the ratio of objects

The shape of an object, its volume, an object in space - this is mathematics. Pyramid, cubes, nesting dolls, cups of different sizes are mathematical toys. Pouring a spoonful of water from one cup to another is a mathematical game. Taking a bath with three plastic ducklings is also a math game. Why? Because the child understands that three ducks are a kind of "3", exactly the same as three cookies or three cars, the same as three fingers. And how mother stroked her head three times and sang a song three times. When a child suddenly understands that there is some universal “3”, the child understands mathematics. And not when they buy him a notebook with tasks or bring him to the "mouse" group.

Why? Because the child understands that three ducks are a kind of "3", exactly the same as three cookies or three cars, the same as three fingers. And how mother stroked her head three times and sang a song three times. When a child suddenly understands that there is some universal “3”, the child understands mathematics. And not when they buy him a notebook with tasks or bring him to the "mouse" group.

I will now explain why I work with children from the age of four in a group. Simply because four-year-olds can already set some meaningful tasks and they are already socialized enough to interact in a group.

Three-year-olds will think more about where mom is and when she will come, and not about the task and the game. It is better for three-year-olds to play math with mom and dad. They still have the main channel of perception - interaction with a significant adult. They are not yet ready (the brain has not matured) to operate with abstract concepts and signs. For them, role-playing is much more important.

And by the way, the role-playing game just brings them to math. One of the basics of role-playing is "come on like it's...". If at 11 months the baby dragged his bear to the book about the bear, then at 2.5-3 years (someone earlier) he is ready to admit that “as if” a bump, a finger, a cube can be a bear, and a bear can be “as if” by Dr. Aibolit, Barmaley, a tiger or a child. This “as if” is a big step towards mathematics.

At the age of four, children, as a rule, are already ready to play with their peers without parents for some time, ready to interact with another adult, their brain is ready to perceive signs (numbers and letters), many already “know how to count”, that is, tell a rhyme "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten", hold a pen or pencil well, can perceive and complete tasks from several stages.

At the same time, we still "do math" with a pen and paper at the table very little. We play mathematics with different objects (oh, what visual materials we have!), we run, jump, crawl. And at the same time we count childish steps, jumps, my “meow”, “kar” and “woof”. We make patterns from cubes (do you think it's simple?). And we do a lot more interesting things for children. And as a result, the child does not just "do math", he begins to understand it through himself, through his fingers, arms, legs and even his back. We have a game, such a “spoiled phone”, when you have to count with your back. The child really feels mathematics. Do you understand?

And at the same time we count childish steps, jumps, my “meow”, “kar” and “woof”. We make patterns from cubes (do you think it's simple?). And we do a lot more interesting things for children. And as a result, the child does not just "do math", he begins to understand it through himself, through his fingers, arms, legs and even his back. We have a game, such a “spoiled phone”, when you have to count with your back. The child really feels mathematics. Do you understand?

Photo: iStockphoto (Nadezhda1906)

Even more useful texts with the best advice from psychologists on parenting and how to build relationships in the family (so that no one remains offended), in our telegram channel and on the page about child psychology on facebook.

Mathematics, what are the difficulties faced by parents and children living abroad.

How to deal with a child? And in what language? But as? Transfer? Don't translate? Switch to school language? How to do it so as not to spoil the relationship? Thousands of questions are asked by parents almost daily.

How to learn math and Russian at the same time, so that the child is satisfied and learns with joy? First of all, you need to determine why you plan to study mathematics, what level of both languages the child has, whether the child needs help, whether he loves mathematics.

Our experience shows that the main requests are like this.

1. Help your child with homework. assignments from the local school. baby still small to do it yourself. Consolidate the knowledge gained at school without looking ahead.

2. The child is very math is hard. How does he help?

3. Mathematics at school weak, the child is easy. I would like to give mathematics additionally and in depth, get ahead, learn to solve interesting tasks. Classes for the sake of pleasure, the child loves math, parents want to show the child that mathematics is very interesting and beautiful.

4. The child will pass exams, enter a school with a huge competition. School knowledge is not enough for successful passing the exam, you need to prepare for exam.

5. The child has just moved in, the language of the environment is weak, because the child at school is difficult and incomprehensible, he lags behind and loses motivation.

Each case has its own recipe, and it depends not only on goals, but also on the level of language proficiency. In this article, I will not write about those cases when the Russian language is weak and does not allow him to study.

Well, let's start.

First and second requests can be combined, because in any of these cases the child needs help with learning and the parent will have to figure out how set up a local program for mathematics.

Children come for help, it is difficult and incomprehensible for them, parents wholeheartedly try to help and encounter child resistance. Why?

The main reason is that different countries have different explain different topics. Use different terminology, different designations and another entry. For example, in English countries, the division is written differently than in Germany and Russia.

And they teach adding not with the usual column, but using a number line. The multiplication and division signs are different, and even numbers are written differently. Of course, it is important for a child to be explained to him in the same way as in the classroom, only more clearly. It is important for a child not only to get the correct result and learn how to solve, but also to master the school method for successful application in the classroom. Some children are afraid to decide differently than the teacher explained, and in some schools they do not decide in a different way. Do not force the child to conflict with the school, defending their position and decision there. What to do? The child really needs help.

Parents will have to figure out what they want at school. It's good if there are textbooks, but sometimes you have to go to a school for a consultation, watch videos on the Internet, buy local textbooks, ask on the forum. But it is just possible to discuss problems in Russian. If the method is the same as at school, then Russian terminology can be introduced. The child will easily transfer the knowledge gained at home to school mathematics. This is a difficult but doable task. As a result, everyone will benefit: both the child who understands that the parent is ready to understand his problems and solve them, and the parent, and the Russian language.

If the method is the same as at school, then Russian terminology can be introduced. The child will easily transfer the knowledge gained at home to school mathematics. This is a difficult but doable task. As a result, everyone will benefit: both the child who understands that the parent is ready to understand his problems and solve them, and the parent, and the Russian language.

Third request. It is too easy for a child in mathematics lessons, he wants to study mathematics in depth. In this case, parents have much more freedom and there is no need to rely on the school curriculum. You can search for interesting tasks in Russian, local or other language you are learning. You can use books and manuals. The choice is up to the parents, but the following parameters should be taken into account:

- Which further education of the child is planned in the country

- What language parents find it easy to find information, whether they know the terminology in the language of the environment and whether they want to understand it.

- Can the child is free to read and write in Russian.

- Are there enough interesting sources in the language environment. (There are many and very high-quality sources in Russian, in English too)

(tasks from the Kangaroo Mathematical Olympiad)

It will be possible to find interesting courses and selections in the language of the environment, invite the child to translate assignments into Russian, make a dictionary with the necessary terms. You can combine tasks by selecting tasks in two languages on one topic. It is very important to link terms in two languages, this will help the child to freely participate in Olympiads in the future and it is easier to learn new topics at school, and also helps to develop the Russian language. There are international mathematical Olympiads, tasks for which can be found in almost any language.

With the majority of students, we combine tasks in different languages and within the same lesson we read and solve problems both in the language of the environment and in Russian.

However, I would like to note that even when doing mathematics in depth, it would be good to imagine what topics the child has already studied at school, and which ones he has yet to get acquainted with. Each country has its own peculiarities: some of the topics taught by children studying in the English program are not studied by children in Russia, and vice versa.

Fourth request. The child has to pass a difficult exam. Of course, the child must be prepared for test based on the local curriculum and exam requirements. Here, not only formal knowledge is important, but and the ability to read assignments carefully, unravel complex wording and clearly answer the questions posed.

The educational material itself must be in the language of the environment, the parent needs to understand in the requirements for applicants and conduct a lot of preparatory work.

And during the lessons it is possible to discuss tasks in Russian, moreover, it happens that the child has not yet formed the necessary terminology in the school language, i. e. the wording is not clear. You can create a dictionary of terms, write out phrases from tasks - all this will help the child in the exam. As a rule, in bilingual children, the acquired skills move freely between languages, regardless of the language in which the task was discussed.

e. the wording is not clear. You can create a dictionary of terms, write out phrases from tasks - all this will help the child in the exam. As a rule, in bilingual children, the acquired skills move freely between languages, regardless of the language in which the task was discussed.

Of course, the main purpose of such classes is to prepare for the exam, and not to study the language, but, nevertheless, the language develops in such classes.

Fifth request. The child has just moved, and it is difficult for him to master the school curriculum. This case is very similar to the first and second requests. Even if mathematics was easy for a child before, now the requirements have changed, and often the curriculum does not coincide with the Russian one. The helping parent will have to deal with the school system, new requirements and unusual notation, terminology and wording. Help your child to be successful in at least one of the areas, this is very important. Mathematics is the first subject that a child successfully copes with in a new school life.

Mathematics is the first subject that a child successfully copes with in a new school life.

Despite the fact that the requests are different, the purpose of the classes is still the same - to make it easier and more interesting for the child to study, to help him achieve his goals. By adapting to the local education system, the parent takes the side of the child, and this is really important for him. Math classes with translation of terms, discussion of problems in Russian gives the child the opportunity to start learning in Russian, which is very important for the development of the language and gives the student the opportunity to understand why he needs the Russian language. The most important thing is to be on the side of the child, to hear him, to understand the problems and requests, to choose the optimal training scheme. In my opinion, a language truly lives and develops when you not only learn it, but learn from it. Classes in mathematics, science, chess in Russian are no less effective than classes in the language of the environment.