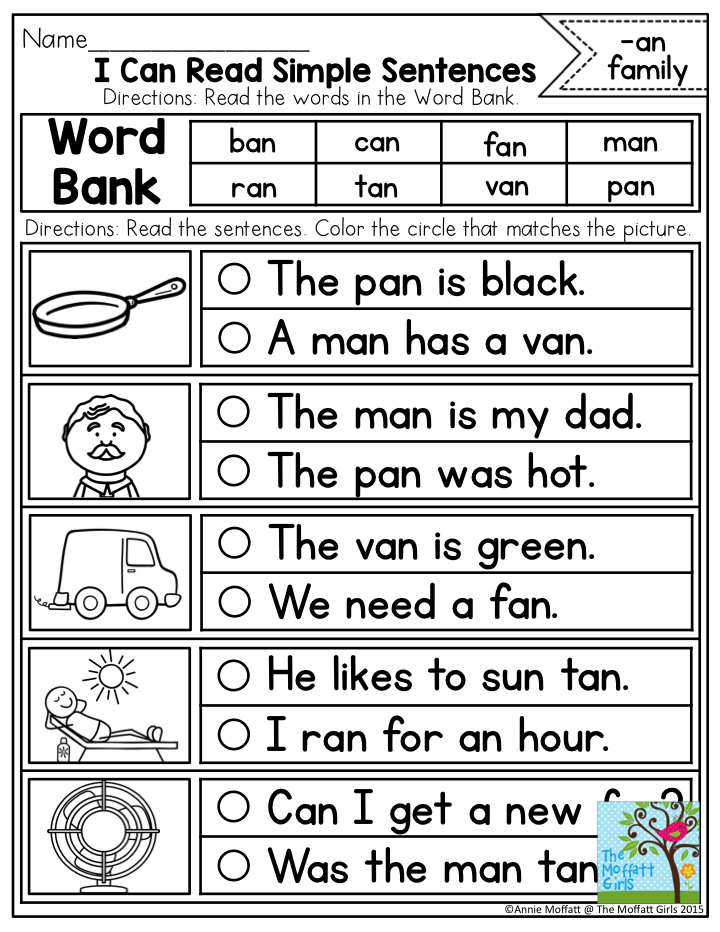

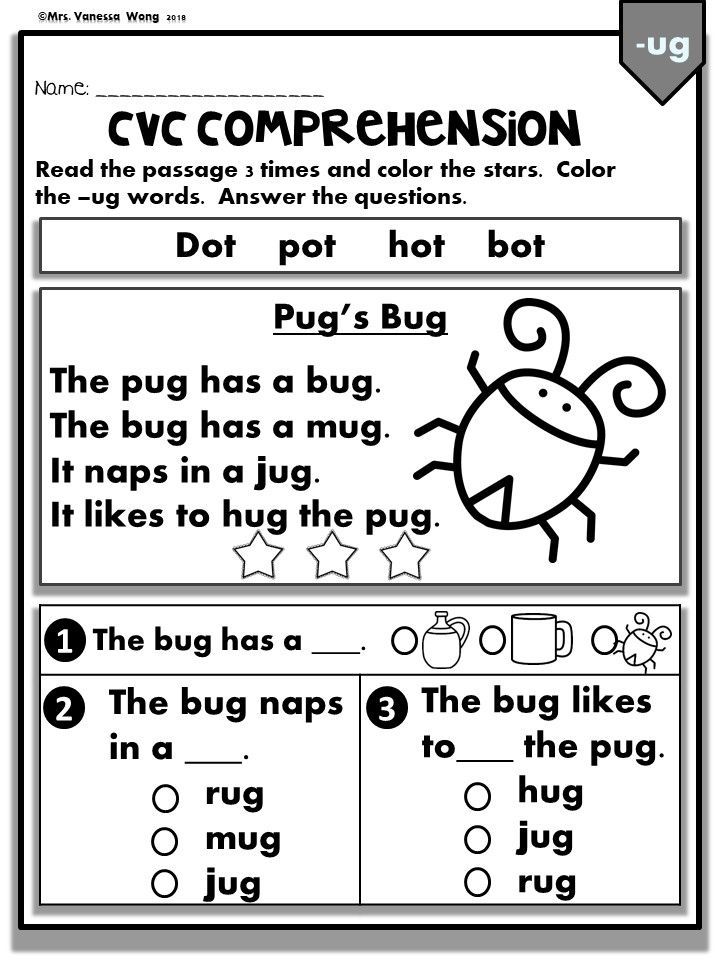

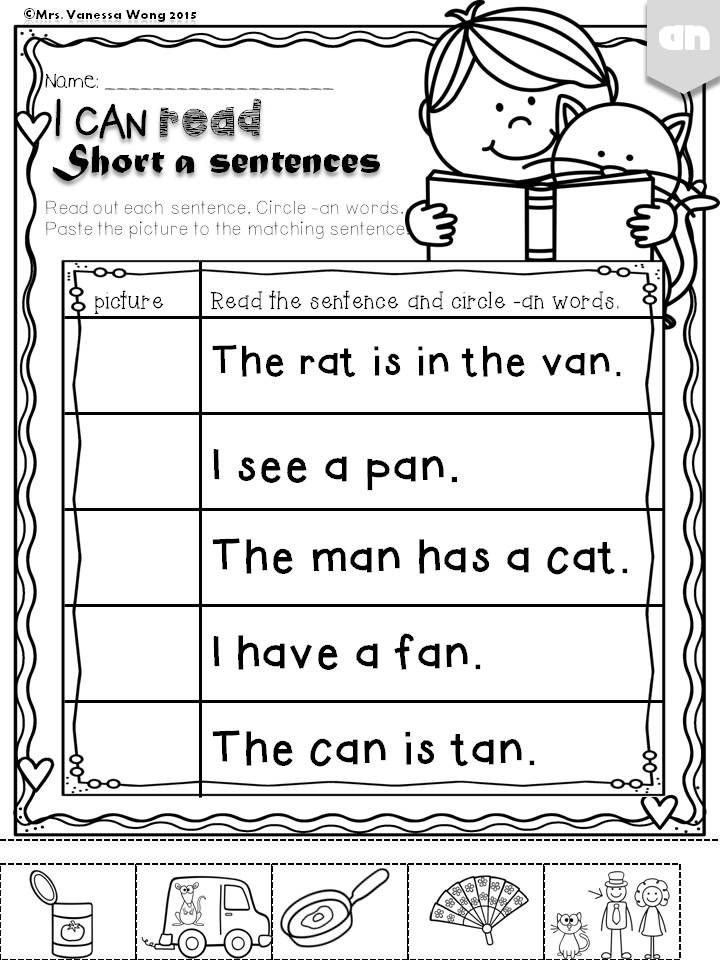

Early reading words

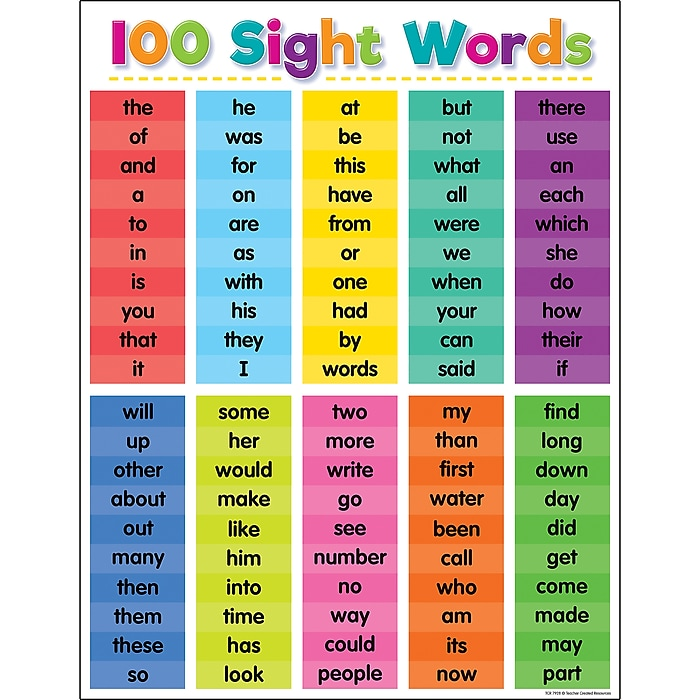

The Perfect Sight Word List For Beginner Readers.

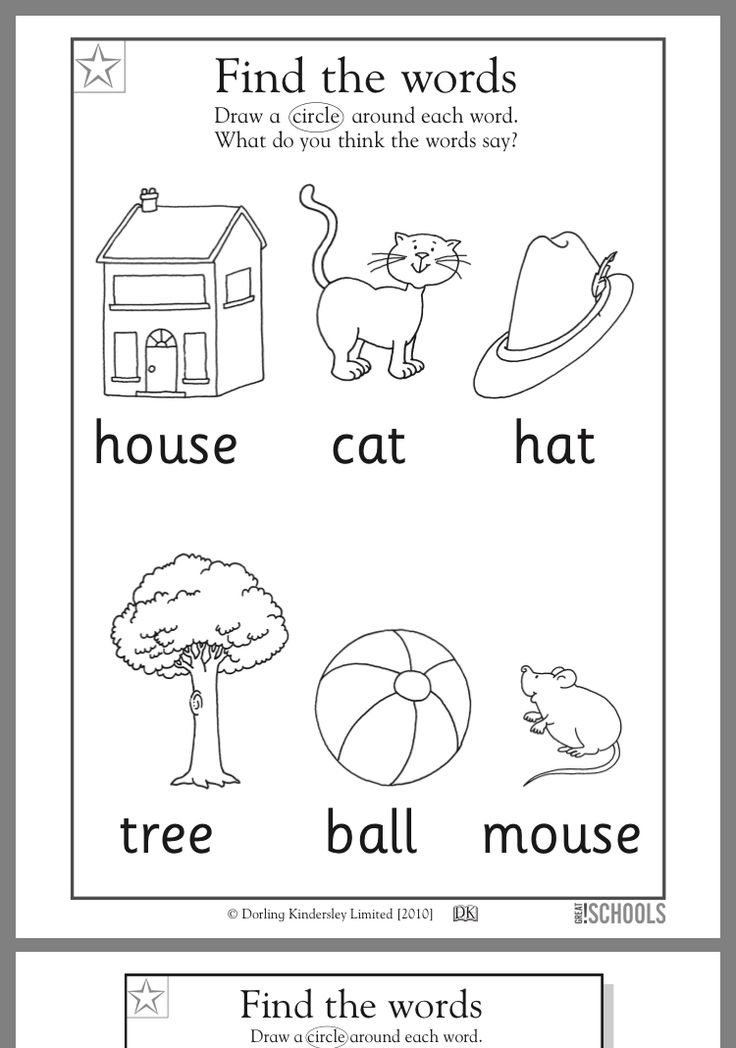

Children in their first years at school, who learn the sight word list below, will have an excellent start to reading and writing.

Initially this process takes time, often months. That's why teachers introduce lists like this to children, gradually, when they first start school. But it doesn't hurt them to recognise a few words before then, if they are ready to learn them.

Sight Word List

The list of sight words below is broken into groups. Each group consists of 10 words.

There are several lists available for teachers to use. But they are virtually identical as they are composed of words children most frequently use.

The list below covers 80 of the first sight words your child will need to know.

The trick is to ensure your child recognises the words in one group before starting another. But as I mentioned before, this doesn't happen immediately. So don't feel you need to put pressure on your child or you'll switch off their desire to learn. If you're helping them at home, keep it light.

At the end of this article I will explain how you can gently introduce some of these words to your child so they learn them without pressure.

Don't be concerned if your child finds the list below too difficult at this stage. They may only manage the first group of words. Or they may not be ready for them at all. If that's the case, wait for their teacher to guide you.

|

|

|

|

More About Sight Words

Your child needs to learn these word by sight rather than decode them. That means they may need to see them many, many times in order to memorise them.

That means they may need to see them many, many times in order to memorise them.

You may be asking yourself about now

- what exactly is a sight word?

- why are they so important in reading?

- how do you know what is a sight word and when do you sound out a word?

If you want to know more, click on my article What Are Sight Words? There you'll get answers you need. At the same time you'll see how it's affected an adult student of mine who hasn't ever known them!

Introducing Them To Your Child

Here's a great way to introduce sight words.

- Print off two copies of the sight word list.

- Cut two copies of the group One words starting the word 'I'.

- Cut each of the words individually.

- Place one set of the words in front of your child. You keep the other.

- Hold up one of the words

- Read it to your child and ask them to find the matching word. (They will study the shape of the letters and hear the word associated with them.

)

) - When they find the matching word, repeat the word. Say: "Yes, that word says ...... Can you tell me what the word says?" (This reinforces and matches in their brain the visual appearance of the word with how the word sounds.)

Play this game often and you'll find your child will become increasingly comfortable with these words. Gradually they will memorise them. They will then build up an invaluable bank of everyday words for reading and writing.

If you are struggling to engage your child, click on my phonics games page. There you'll find out how important it is to make learning fun. Plus great activities you can do at home to breathe life into learning literacy skills.

Go From Sight Word List To Literacy Lessons

Go To Phonics Literacy Homepage

Top 100 Sight Words and How to Teach Them

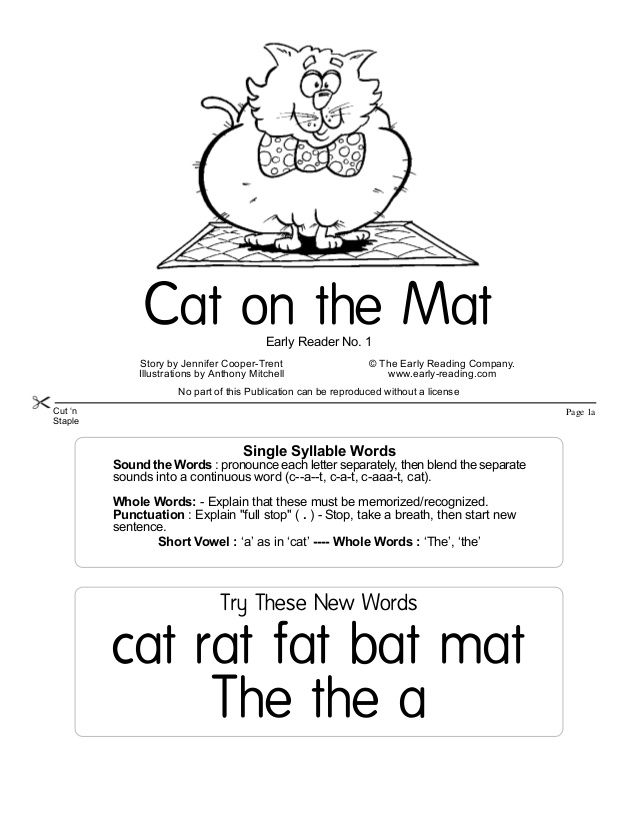

Sight words is a common term in reading that has a variety of meanings. When it is applied to early reading instruction, it typically refers to the set of about 100 words that keeps reappearing on almost any page of text. “Who, the, he, were, does, their, me, be” are a few examples.

“Who, the, he, were, does, their, me, be” are a few examples.

In addition to their being very frequent, many of these words cannot be “sounded out.” Children are expected to learn them by sight (that is, by looking at them and recognizing them, without any attempt to sound them out.)

Unfortunately, this means minimal teaching. Often, little is done other than to show the word and tell the child what it is “saying.” For many children, this is not enough, with the result that their reading of these critical words is laden with error.

What does this mean for parents who are helping their children master reading? Basically it means spending some time in truly teaching these words so that your child gains real mastery of them. The key to achieving this goal is accurate writing (spelling)—via memory. That is, the child writes the word when the model is not in view.

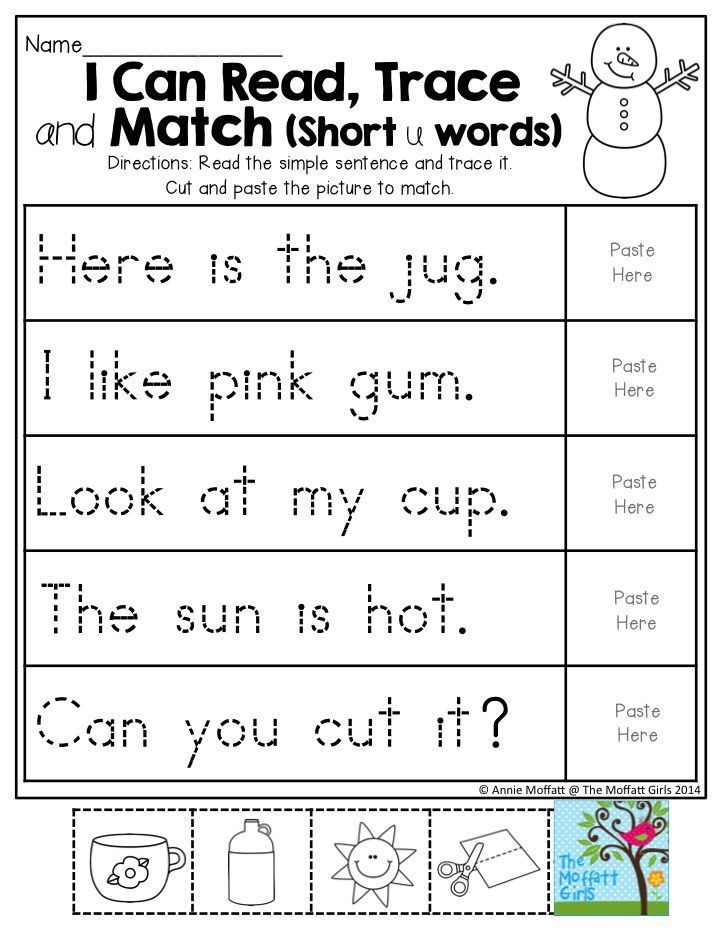

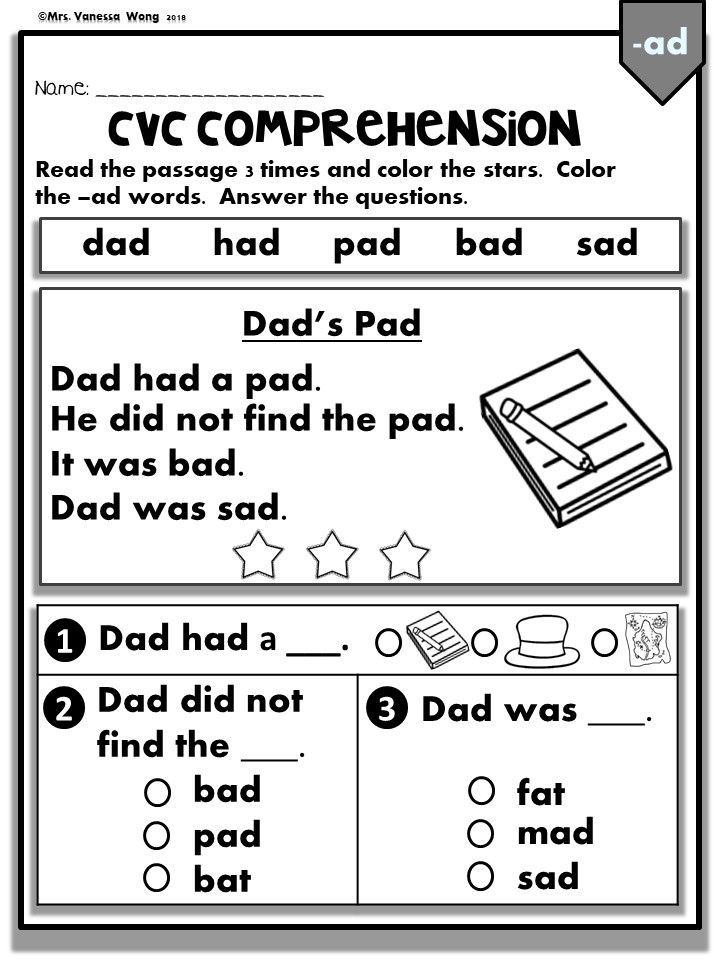

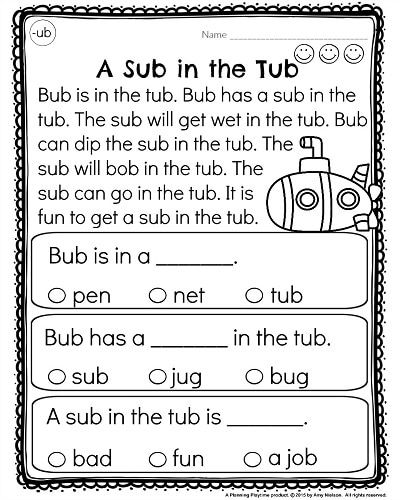

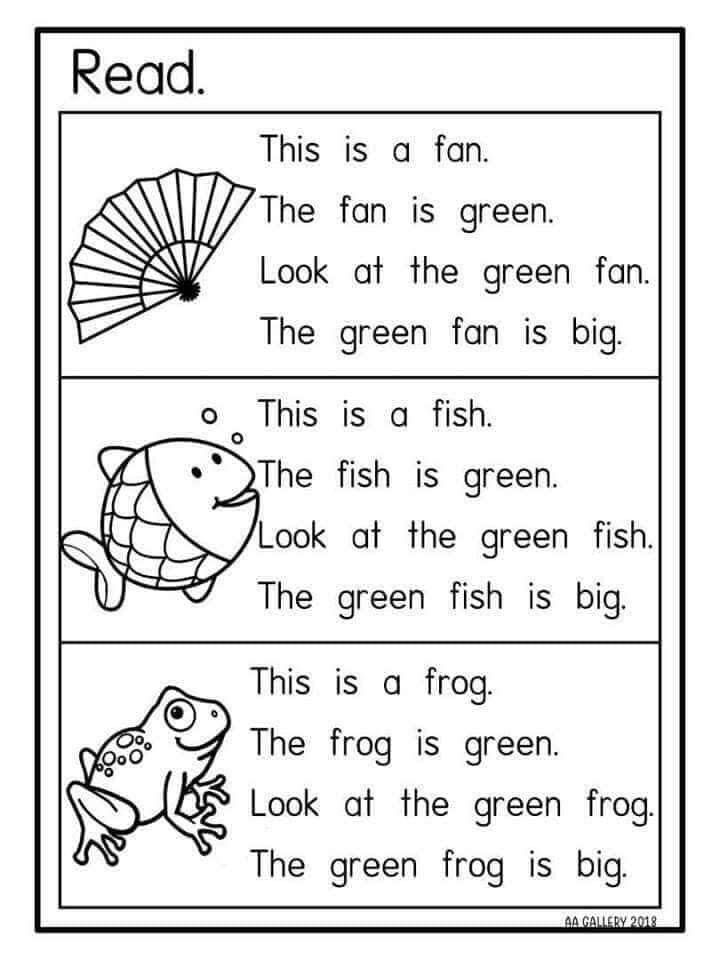

You can do this by creating simple sentences that the child reads. (By using sentences, you will automatically be using many “sight words. ” In addition, you will be giving your child the opportunity to deal with words in context—a key to meaningful reading) After showing the sentence and having your child read it, turn it over and then dictate the sentence. If there is an error, you immediately stop your child and take away the paper. Then you show the model again and repeat the process. In other words, the writing of the sentence has to be fully accurate, starting with the first word.

” In addition, you will be giving your child the opportunity to deal with words in context—a key to meaningful reading) After showing the sentence and having your child read it, turn it over and then dictate the sentence. If there is an error, you immediately stop your child and take away the paper. Then you show the model again and repeat the process. In other words, the writing of the sentence has to be fully accurate, starting with the first word.

If you want a list of those words to help guide your efforts, here is the top 100 according to the American Heritage Word Frequency Book by John B. Carroll.

A: a, an, at, are, as, at, and, all, about, after

B: be, by, but, been

C: can, could, called

D: did, down, do

E: each

F: from, first, find, for

H: he, his, had, how, has, her, have, him

I: in, I, if, into, is, it, its

J: just

K: know

L: like, long, little

M: my, made, may, make, more, many, most,

N: not, no, now

O: or, one, of, out, other, over, only, on

P: people

S: said, she, some, so, see

T: the, to, they, this, there, them, then, these, two, time, than, that, their

U: up, use

V: very

W: was, with, what, were, when, we, which, will, would, words, where, water, who, way

Y: you, your

Click here to download our Recommended Top 100 Sight Words.

Literacy and reading expert, Dr. Marion Blank

Dr. Marion Blank is answering your questions about reading and learning. If you have a question for Dr. Marion, visit the Reading Kingdom Facebook Page and let us know how we can help.

If you think the Reading Kingdom program can help your children learn to read, enjoy a free, 30-day trial here.

On the dangers of early learning to read: Why is prematurely developed phonemic hearing bad?

Up to now I have thought that early learning to read (before the age of four or five), although useless, can still not bring any harm. Therefore, if it so happened that parents, having become infected with the ideas of early development, start reading from the cradle, then there is no big trouble in this. Parental impatience is quite understandable: what if, in fact, Doman is right - and it is already hopelessly late to teach a seven-year-old child to read - just as hopelessly as teaching to speak? Let Doman not give any experimental confirmation of his theory (except for experiments on rats), but there is logic in his reasoning! It is so?

My confidence in the harmlessness of early reading was greatly shaken after meeting Lev Sternberg, the author of the rebus method, with the help of which he taught more than a thousand children of kindergarten age to read. The fact is that Sternberg strongly discourages reading with children under the age of five, and he considers classes with kids under the age of four to be completely unacceptable. This is the rarest case when a person publicly defends a point of view that is in blatant contradiction with his mercantile interests. For that alone, she deserves to be taken seriously.

The fact is that Sternberg strongly discourages reading with children under the age of five, and he considers classes with kids under the age of four to be completely unacceptable. This is the rarest case when a person publicly defends a point of view that is in blatant contradiction with his mercantile interests. For that alone, she deserves to be taken seriously.

In contrast to Doman, Sternberg argues that, according to his observations, children who are prematurely taught to read usually lose their apparent advantage after two or three years and become noticeably dumber than their peers. They have more problems with logical thinking, foreign languages are more difficult for them and, paradoxically, they show less interest in reading.

— Where is the proof? I yelled indignantly, immediately remembering that I started teaching my eldest son to read when he was two years old. Where is the experimental evidence?

My interlocutor did not have any experimental confirmation, but he readily shared with me the theoretical arguments substantiating his correctness. I must admit that Sternberg's theory is no less logical than Doman's, and perhaps even more so. I present it in a brief free retelling.

I must admit that Sternberg's theory is no less logical than Doman's, and perhaps even more so. I present it in a brief free retelling.

As you know, teaching a small child letters is not a problem. Difficulties begin when we write two letters in a row - for example, "ba" - and ask the baby to pronounce the resulting syllable together. It turns out that this task is not up to him. The question is why? What, it would seem, is difficult here?

Let's ask ourselves a question: why did we ask the child to read the syllable "ba" and, say, not the syllable "be"? Understandable why. The child will certainly not cope with the syllable "be". Indeed, in the syllable "be" the letters "b" and "e" are pronounced differently from how they are read when they stand separately, by themselves. In the syllable "be", the letter "b" becomes soft, and the initial iotation disappears from the letter "e". No matter how quickly we pronounce the two letters “b” and “e” one after another, they will not merge into the syllable “be”.

But the situation is exactly the same with the syllable "ba"! Let's try to quickly pronounce the sounds in a row, transmitted by the separate letters "b" and "a". Do they merge into one syllable "ba"? Nothing like this!

For those who have mastered phonetics well from the school course, this result should seem unexpected. In school, we are told that the graphic symbol "b" represents the sound [b], and the graphic symbol "a" represents the sound [a]. Therefore, it would seem that if we read the letter “b” first, and then “a”, then it should sound like [ba]. Why doesn't this actually work?

Let's listen more closely to the sound we make when we read the letter "b". Better yet, take a microphone and record this sound in an audio editor:

We see that our sound consists of two parts, the first part is quieter, the second is louder, and each with its own special sound wave pattern. Listening to these parts separately, it is easy to make sure that by ear none of them even remotely resembles the sound [b]. It turns out that the sensation of sound [b] is created by nothing more than a transition from one part to another.

It turns out that the sensation of sound [b] is created by nothing more than a transition from one part to another.

And now let's read and write down the syllable "ba" in the audio editor:

Isn't it true, the picture turned out surprisingly similar? Here are the same two parts: one is quieter, the other is louder, only the wave pattern of the second part is not the same as before. (However, when I was preparing this picture, I deliberately pronounced the syllable "ba" very briefly, so that the duration of the sound of both recordings was approximately the same.)

Thus, the single letter "b" and the letter combination "ba" generate sounds of exactly the same structure. But if in the sound generated by two letters “ba”, we can distinguish a consonant and a vowel component, then the sound generated by a single letter “b” should have exactly the same composition. Indeed, voicing the letter “b”, we end, albeit with a short, but still almost unhindered exhalation, which has all the formal features of a vowel and resembles something between [o] and [s]. A hundred years ago, in the Russian alphabet, to convey this vowel, there was a special letter, which was called "er" and was designated as "b". If we lived in those days, we would not write "b", but "b". However, during the post-revolutionary reform of Russian spelling, the letter "b" was deprived of its main role and renamed into a "hard sign".

A hundred years ago, in the Russian alphabet, to convey this vowel, there was a special letter, which was called "er" and was designated as "b". If we lived in those days, we would not write "b", but "b". However, during the post-revolutionary reform of Russian spelling, the letter "b" was deprived of its main role and renamed into a "hard sign".

As for spelling, this is, in principle, a conditional thing: as we agree, we will write. But when we want to display the pronunciation of a word as a transcription, here we must be as precise as possible. Therefore, the sound transmitted by the free-standing letter "b" should be written as [b]. It is important to note that although we needed two characters to record this sound, nevertheless it is one indivisible sound: we do not pronounce [b] and [b] separately, but only together - [b].

But if [b] is an indivisible sound, then [ba] is also an indivisible sound. We do not tear [b] from [a] in the same way as we do not tear [b] from [b]. Now it remains to find out what happens when we read the letter "a" by itself. Let's use the microphone again and look at the result in the audio editor.

Now it remains to find out what happens when we read the letter "a" by itself. Let's use the microphone again and look at the result in the audio editor.

This time the sound does not split into two parts. The sound wave pattern is almost the same everywhere. And yet, there is no need to talk about complete homogeneity, because the amplitude of the sound does not remain constant. If you listen carefully, it turns out that a sharp increase in amplitude at the very beginning of the recording is perceived by our ear as a slight click. This click is heard especially clearly (and not only heard, but also felt) if you try to read the letter "a" in a whisper.

Scientifically, this click is called a "glottal stop", and for those who know at least a little German, it is also known as a "hard attack" ( Knacklaut ). Perhaps the easiest way to feel what it is, on the example of the words "ay-ay-ay" and "oh-oh-oh." Usually we pronounce these interjections together: they sound as if they were written “a-ya-yay!” and “oh-oh-oh!”. Here the glottal stop is present only in the very first "ai" and in the very first "oh". But if you pronounce all subsequent “ay” and “oh” in the same way as the very first ones, then we get: “ay! ouch! ouch! and “oh! oh! oh!". Isn't it true that adding a glottal stop radically changes the sound of a word?

Here the glottal stop is present only in the very first "ai" and in the very first "oh". But if you pronounce all subsequent “ay” and “oh” in the same way as the very first ones, then we get: “ay! ouch! ouch! and “oh! oh! oh!". Isn't it true that adding a glottal stop radically changes the sound of a word?

Some languages have special symbols for the glottal stop: for example, the letter א (aleph) in Hebrew or the icon ء (hamza) in Arabic. Linguists consider the glottal stop to be a full consonant. In the international phonetic alphabet, it corresponds to the symbol "ʔ". Thus, when we read the stand-alone letter "a", we pronounce one indivisible sound, which is conveyed by two characters [ʔa].

What then do the phonetic symbols, taken by themselves, such as [b] and [ʔ], [a] and [b] mean? These symbols stand for abstract "halves of sounds", which are scientifically called phonemes. It is abstract phonemes (and not letters or sounds at all) that are consonants and vowels. Each speech sound has a consonant component, which is characterized by a consonant phoneme ([b], [ʔ], etc.), and a vowel component, which is characterized by a vowel phoneme ([a], [ъ], etc.). Similarly, the situation is with musical sounds displayed on the letter in the form of notes. Each note is defined by pitch and duration, two abstract characteristics that by themselves, one without the other, do not exist.

Each speech sound has a consonant component, which is characterized by a consonant phoneme ([b], [ʔ], etc.), and a vowel component, which is characterized by a vowel phoneme ([a], [ъ], etc.). Similarly, the situation is with musical sounds displayed on the letter in the form of notes. Each note is defined by pitch and duration, two abstract characteristics that by themselves, one without the other, do not exist.

Now it is clear why a small child is not able to merge the letters "b" and "a" into one syllable "ba". Because the sounds [b] and [ʔa] in principle cannot merge into the sound [ba]. It is as if we played a half note "F" and a quarter note "A" to a child and expected him to sing the half note "A" to us in response. This requires a sufficiently developed abstract thinking, the ability to manipulate the "halves of sounds" that do not actually exist, and this is still beyond the power of the kids.

Traditional methods of teaching reading, designed for children of six or seven years of age, rely entirely on the ability of students to think abstractly. This ability is further developed with the help of the so-called phonemic hearing. An adult says to a child (who cannot read yet):

This ability is further developed with the help of the so-called phonemic hearing. An adult says to a child (who cannot read yet):

- I will now name two words, and you will clap your hands immediately after the one that begins with the sound "b". Listen carefully: "stick - beam."

According to the plan of an adult, the child should clap his hands after the word “beam”.

Further, more. An adult asks:

- What sound does the word "bank" begin with?

To this a child who has become proficient in phonemic hearing must answer:

— From the sound "b".

Such activities with a child are so commonplace that we do not notice how unnatural they are. Indeed, in reality, the word "beam" does not begin at all with the sound that is transmitted by the free-standing letter "b". The word [beam] begins with a single and indivisible sound [ba], and there is no sound [b] in this word at all. In fact, we teach the child to "hear" in our speech those sounds that we do not pronounce.

However, most children are smart enough to know what to say to please adults. Very little time passes - and the child, without blinking an eye, begins to assert that the word [bank] begins with the sound [b]. Phonemic hearing is considered to be successfully formed when a child “learns to hear” about four dozen sounds in Russian speech - such as [ʔа], [bъ], [b], [vb], [v], etc. - and not hear anything else . For example, in the word “bank” a good student hears the sounds [b], [ʔa], [nb], [kъ] and again [ʔa], and in the word “ball” - [m], [ʔa], [ch ], [ʔi] and [къ].

This phonemic awareness is said to be very useful for reading and writing. But at the same time, this is nothing more than the “ability to hear” what is not, and not to notice what is. Phonemic hearing is a grossly distorted perception of reality in favor of some artificial scheme. All the variety of human speech in a trained child is reduced to a limited set of standard sounds. This set includes only those sounds that can be transmitted by a single letter of the Russian language or by a pair of "consonant" + "ь". (At the same time, it should be noted that not every letter generates a standard sound. So, the separate letters “b” and “b” cannot be voiced, but in the iotized vowels “e”, “e”, “yu”, “I” of the child they teach to hear not one indivisible sound, but two at once - respectively [yy-ʔe], [yy-ʔo], [yy-ʔy] and [yy-ʔa]).

(At the same time, it should be noted that not every letter generates a standard sound. So, the separate letters “b” and “b” cannot be voiced, but in the iotized vowels “e”, “e”, “yu”, “I” of the child they teach to hear not one indivisible sound, but two at once - respectively [yy-ʔe], [yy-ʔo], [yy-ʔy] and [yy-ʔa]).

All this is as if glasses with filters were put on a child's eyes, which out of all the variety of colors let through only four dozen, and even then - in a very distorted form. Such a child, instead of a full-fledged picture:

, begins to see something like this:

the letters "b" and "a" into the syllable "ba". Some children, however, do not lend themselves to such learning at all and stubbornly refuse, for example, to recognize that the word [bank] begins with the sound [b]. Well, they don't hear that sound there and that's it. These children are called dyslexics. They experience great difficulty in learning to read by traditional methods, although they may be higher in intelligence than their peers. School teachers usually send them to speech therapists so that they can convince them with their special professional methods that there is a sound [b] with the word [bank].

School teachers usually send them to speech therapists so that they can convince them with their special professional methods that there is a sound [b] with the word [bank].

Phonemic awareness is specific to each particular language. Therefore, having learned to decompose all words into sounds corresponding to the Russian alphabet, the child largely loses the ability to correctly perceive and reproduce foreign speech. He does not distinguish between the English "shit" and "sheet", and instead of the German "natürlich" he says "natürlich".

However, the abuse of the natural order of things is not limited to phonemic hearing alone. As soon as the child begins to grasp the logic underlying the lettering of words, it immediately turns out that this logic is violated at every step. It is written "him", but for some reason it is necessary to read "evo"; “what” is written, but it is necessary to read “what”, etc.

It is clear that we are all hostages of the culture in which we live. In our writing, letters do not convey sounds, but "halves of sounds" - phonemes, and very inaccurately and inconsistently. Whether we like it or not, sooner or later, when we begin to teach a child to read and write, we will be forced to spoil his innate speech hearing, replacing it with phonemic hearing. Sooner or later we will have to sow confusion in the child's mind by developing abstract logical thinking in the child and at the same time making it clear that logic is a very unreliable thing. The whole question is when exactly to do it: sooner or later?

In our writing, letters do not convey sounds, but "halves of sounds" - phonemes, and very inaccurately and inconsistently. Whether we like it or not, sooner or later, when we begin to teach a child to read and write, we will be forced to spoil his innate speech hearing, replacing it with phonemic hearing. Sooner or later we will have to sow confusion in the child's mind by developing abstract logical thinking in the child and at the same time making it clear that logic is a very unreliable thing. The whole question is when exactly to do it: sooner or later?

The answer suggests itself: better later , than earlier , and best of all shortly before the child really needs to read books. Modern methods - such as the rebus method - make it possible to teach reading in warehouses simply quickly: two or three months for a five-six-year-old child is enough. At the same time, children easily catch up and overtake their peers who were taught to read earlier.

And, in fact, what kind of reading is this, which is demonstrated by a three-year-old reading? The kid still sorely lacks life experience in order to restore the richness of human speech, with all its intonations, emotions, humor - in a word, with everything that makes it interesting from a set of soulless symbols. This is completed for him in his imagination by benevolent adult listeners - mainly mothers and grandmothers. For the kid himself, reading is an incomprehensible, tedious activity that manages to get bored many times by the age when other children also learn to read and write and, in the wake of primary enthusiasm, begin to show interest in books.

This is completed for him in his imagination by benevolent adult listeners - mainly mothers and grandmothers. For the kid himself, reading is an incomprehensible, tedious activity that manages to get bored many times by the age when other children also learn to read and write and, in the wake of primary enthusiasm, begin to show interest in books.

Doubtful acquisitions of early learning to read quickly disappear, and the losses may be irreplaceable. There is nothing good in forcing a child from the cradle to perceive the world through a filter of very approximate abstract schemes, which are the sequences of letters in relation to living speech. Let the child first listen well to adults, let him learn to speak well himself, and only then it already makes sense to structure his speech experience with the help of abstractions. Only then will the schemes in his mind be filled with full content. And if the filter is applied prematurely, then all the richness and variety of the sounds of human speech will simply pass by the child's ears. Thus, early learning to read is unambiguously harmful: it does not contribute to the development of the mind, but, on the contrary, to the stupidity.

Thus, early learning to read is unambiguously harmful: it does not contribute to the development of the mind, but, on the contrary, to the stupidity.

These are, in general terms, the arguments I heard from Lev Sternberg. I recounted them as I understood them, and if I distorted something, it was not out of malicious intent, but because, in general, all ideas, migrating from one head to another, tend to be distorted.

In my opinion, the colors here are somewhat thickened. Still, youngsters are now being taught to read not according to traditional school methods, but according to Zaitsev's Cubes. Zaitsev taught us to break words not into letters, but into warehouses.

That is not so:

E-t-a s-t-r-o-c-a r-a-z-b-i-t-a n-a b-u-k-v-s.

And so:

E-ta s-t-ro-ka ra-z-bi-ta on s-k-la-dy.

Accordingly, if you spell it, it turns out

[ʔe-t'-ʔa s-t-r-ʔo-k'-ʔa r'-ʔa-z-b-ʔi-t'-ʔa n'-ʔa b'-ʔu- k-v-ʔy].

And if by warehouses, then -

[ʔe-ta s-t-ro-ka ra-z-bi-ta on s-k-la-dy].

Each warehouse is considered one indivisible symbol, and, as it is easy to see, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the Zaitsev warehouses and the single indivisible sounds of Sternberg. In order to learn how to read and write in warehouses, you need not phonemic hearing, but “warehouse”. In the classroom for the development of warehouse hearing, an adult should offer the child, obviously, such tasks:

- I will now say two words, and you will clap your hands immediately after the one that begins with the "ba" warehouse. Listen carefully: "stick - beam."

- Tell me, please, from what warehouse does the word "bank" begin?

Thus, the Zaitsevsky storage filter, which is put on the ears of a child during early learning to read, is still not as monstrously rude as the school phonemic filter, which is put on the ears of a first grader. As for the rest, Sternberg's logic, perhaps, cannot be faulted. I would only like more experimental confirmation, but, as you know, pure logic is an unreliable thing, it happens that it deceives.

07/15/2014

Link to the source

Lev Sternberg's articles about children's reading on the site rebus-method.net

Problems of early learning to read

E. Demina, speech therapist MBDOU №21

Now no one doubts that the success of a child's education in school largely depends on how well he is prepared for it. Most parents believe that if their son or daughter can read, then they are ready for schooling. And they try by all means to teach the child to read from the age of four or five, and sometimes even earlier.

The problem of early learning to read has been discussed for many years and has both supporters and opponents, even when the social demands of society, schools, and families speak in favor of such learning. The system of early development of a child, including teaching to read, can and should have a positive aspect, if we look at it not as a recipe for "cultivating geniuses", but as one of the means of understanding the world by a child. The issue is not the advisability of early learning to read, but how best to do it.

The issue is not the advisability of early learning to read, but how best to do it.

Most children cannot learn to read and write correctly right away. Difficulties can be caused by various reasons. But the most significant reason, in my opinion, is that an increasing number of preschoolers have speech disorders of varying degrees of severity and, most importantly, insufficient formation of phonemic perception.

Written speech, unlike oral speech, is formed in conditions of purposeful learning. Reading is the recognition and reproduction of speech sounds indicated by a letter. Therefore, before introducing a particular letter to a child, it is important to find out whether the child isolates the given sound from the speech stream; can independently pick up words with a given sound; copes with the analysis of the sound composition of the simplest words.

If a preschooler is experiencing difficulties, it is necessary to help him master these skills, because all of the above is an important condition for successfully mastering the skill of reading. In order to merge sounds into syllables and words when reading, the child must analyze which “neighbors” the letter has, and based on this, how to read: soft or hard.

In order to merge sounds into syllables and words when reading, the child must analyze which “neighbors” the letter has, and based on this, how to read: soft or hard.

Learning is a game that must be stopped before the child gets tired of it. The main thing is that he should be “undernourished” and get up from the “table of knowledge” with a feeling of constant “hunger”, so that his thirst for knowledge does not dry out.

The essence of reading is a complex process consisting of a number of operations: letter recognition, its connection with a phoneme, merging letters into syllables, syllables into words. The quality of reading is characterized by the way of reading, its speed (fluent or syllable-by-syllable), correctness, meaningfulness.

The reasons for the difficulties in teaching reading are:

1. Pedagogical neglect (due to the lack of a student-centered approach), caused by the forced pace of learning; numerous absenteeism; insufficient control over the assimilation of knowledge; the passivity of teachers in providing individual assistance; low qualification of specialists; family indifference, etc. ;

;

2. A predisposition that may lie latent for a long time, but under favorable conditions "blooms" violently.

Many years of experience working with children confirms that the earlier a child learns to read and write, the fewer problems he has with schooling, the more successful it is, gives more positive emotions, and less often there are difficulties.

And even when working with children with speech disorders, early learning to read makes it possible to productively use the potential of correctional pedagogy: a letter, unlike a sound, has a permanent image, so it is easier to automate sounds through reading in syllables, words, phrases; analytical and synthetic activity develops; the vocabulary is refined, enriched, the child masters the skills of inflection and word formation; self-confidence appears, negative attitude towards school disappears, fear of failure, fear of getting bad grades; communications are being improved.

When choosing a method of teaching reading to children with speech disorders, communication difficulties, emotionally immature, suggestible and insufficiently capable of understanding their own problems, before giving preference to one method or another, it is necessary to clarify which type of perception dominates in the child (analytical or synthetic), and build your work taking into account this feature.

In addition to clarifying the dominant type of perception, it is necessary to find out which of the child's analyzers is functionally stronger: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, or tactile. Not only methods are individualized, but also the pace of learning. The discrepancy between the rate of presentation of the material and the individual pace of assimilation leads to inadequate mastery of skills, slows down the learning process, reduces children's self-confidence, and causes pedagogical neglect.

Laying out letters from sticks helps to form a stable graphic image of a letter in a child, transforming it in the most appropriate way. In order to reduce the number of optical errors, to avoid mixing letters, it is advisable to compare letters similar in spelling, highlight common elements, and teach to see the difference in their location. Very effective are the methods of tracing the contour of the letter with a finger, the methods of dermolexia (drawing letters on the palm), tactile recognition of letters. Children with speech pathology have difficulty in syllables. Therefore, it is important to take into account the specifics of teaching preschoolers to read and write and the pronunciation capabilities of each child individually. These children learn to read backward syllables more easily, and then direct ones. But do not linger on reading syllables, let's move on to reading monosyllabic words with a closed syllable. Significant problems in children of speech therapy groups are caused by the division of words into syllables. To overcome these difficulties, color marking of syllables, division into syllables with the help of vertical lines is used. While the children are at the stage when the perception and comprehension of what they read are still separated, you can use games that convince the child that he is already reading and understands the meaning of the short task. The kid reads, follows the instructions and finds a surprise. As the quality of reading is mastered, the text becomes more complicated: a two-step instruction appears.

Children with speech pathology have difficulty in syllables. Therefore, it is important to take into account the specifics of teaching preschoolers to read and write and the pronunciation capabilities of each child individually. These children learn to read backward syllables more easily, and then direct ones. But do not linger on reading syllables, let's move on to reading monosyllabic words with a closed syllable. Significant problems in children of speech therapy groups are caused by the division of words into syllables. To overcome these difficulties, color marking of syllables, division into syllables with the help of vertical lines is used. While the children are at the stage when the perception and comprehension of what they read are still separated, you can use games that convince the child that he is already reading and understands the meaning of the short task. The kid reads, follows the instructions and finds a surprise. As the quality of reading is mastered, the text becomes more complicated: a two-step instruction appears.