Emergent literacy writing and reading

Emergent literacy | Literacy Instruction for Students with Significant Disabilities

“Emergent literacy is not age dependent but is based on experiences with print!”

–Karen Erickson and David Koppenhaver

Who are emergent readers and writers?

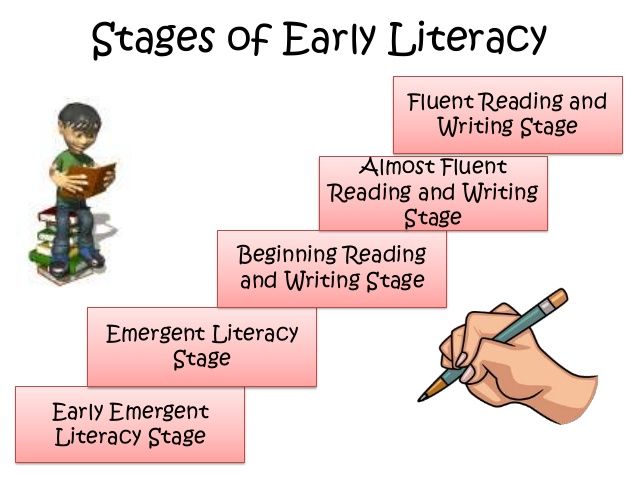

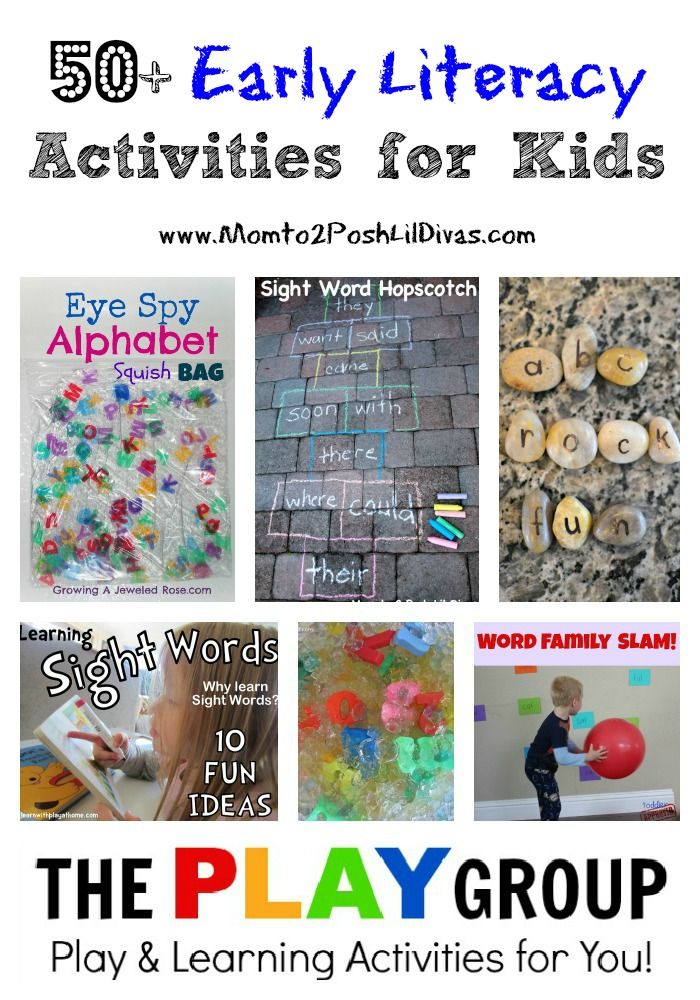

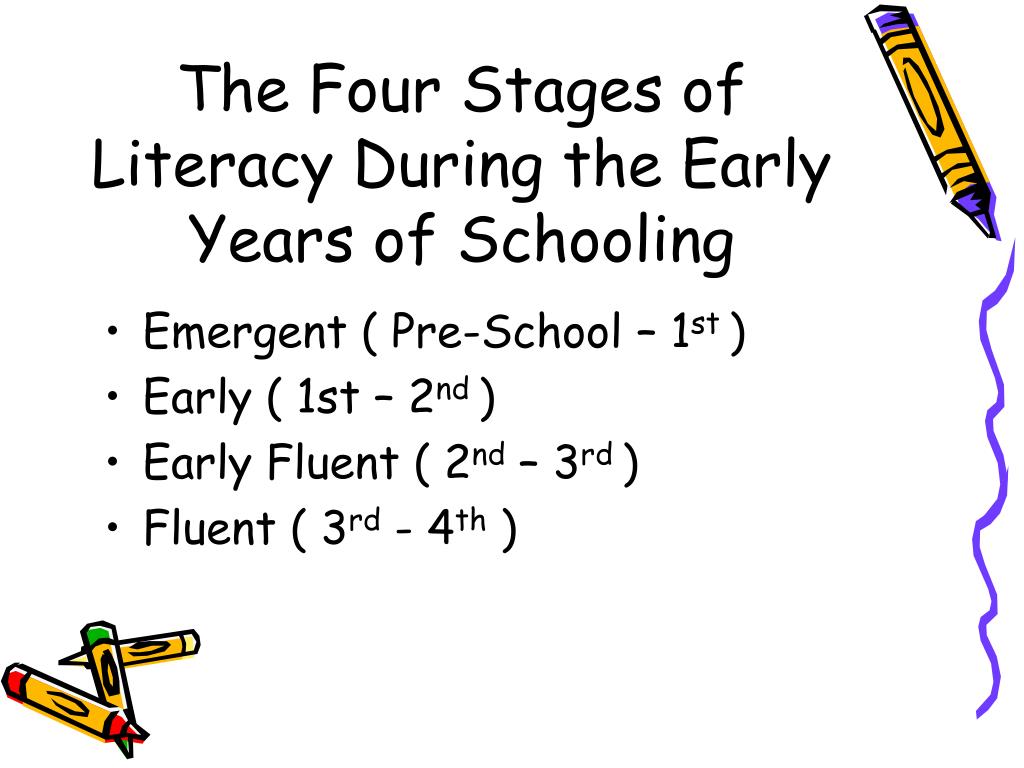

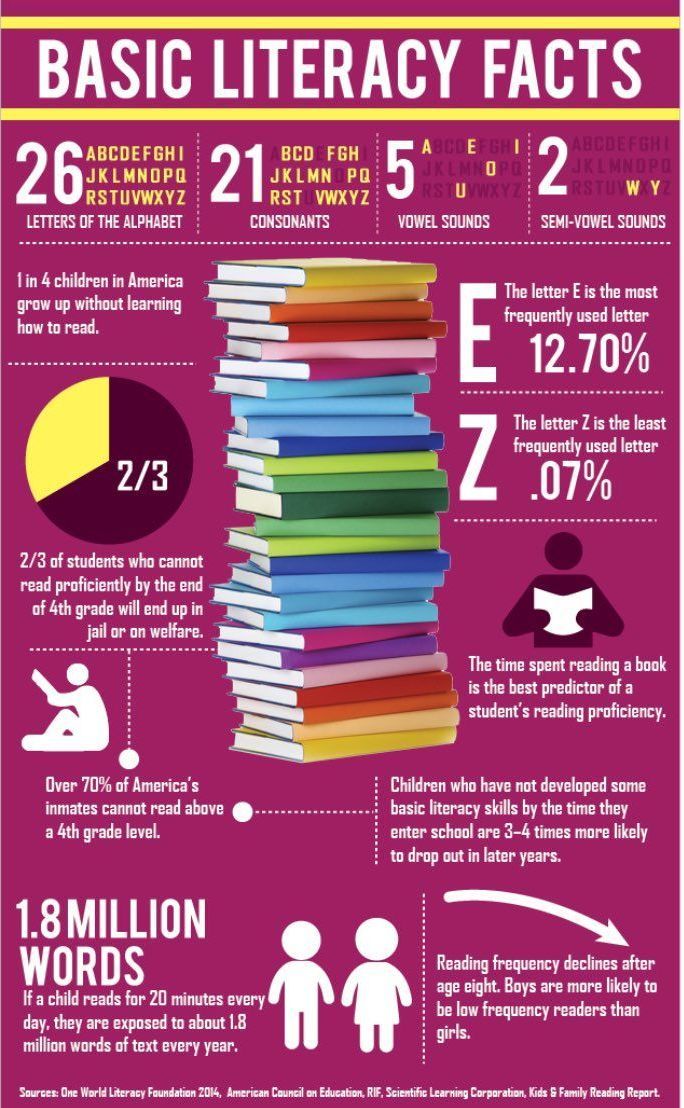

Emergent literacy is the term used to describe the reading and writing experiences of young children before they learn to write and read conventionally (Teale & Sulzby, 1986). Emergent literacy begins at birth, regardless of whether or not a child has a disability. For older emergent literacy learners, it is important to keep all activities age respectful.

Emergent literacy is commonly defined as the behaviors of reading and writing that lead to conventional literacy and “comprises all of the actions, understandings and misunderstandings of learners engaged in experiences that involve print creation or use” (Koppenhaver & Erickson, 2003, p. 283), and these experiences are not only necessary but closely related to later literacy outcomes (Justice and Kaderavek, 2004).

Emergent literacy behaviours and understandings are directly related to opportunity and experience. Students with significant disabilities often have the fewest learning opportunities and experiences that lead to literacy.

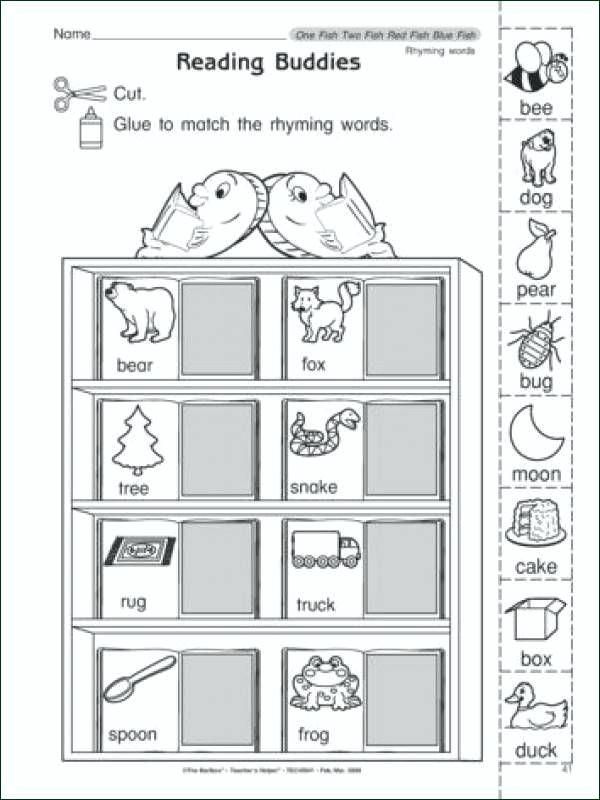

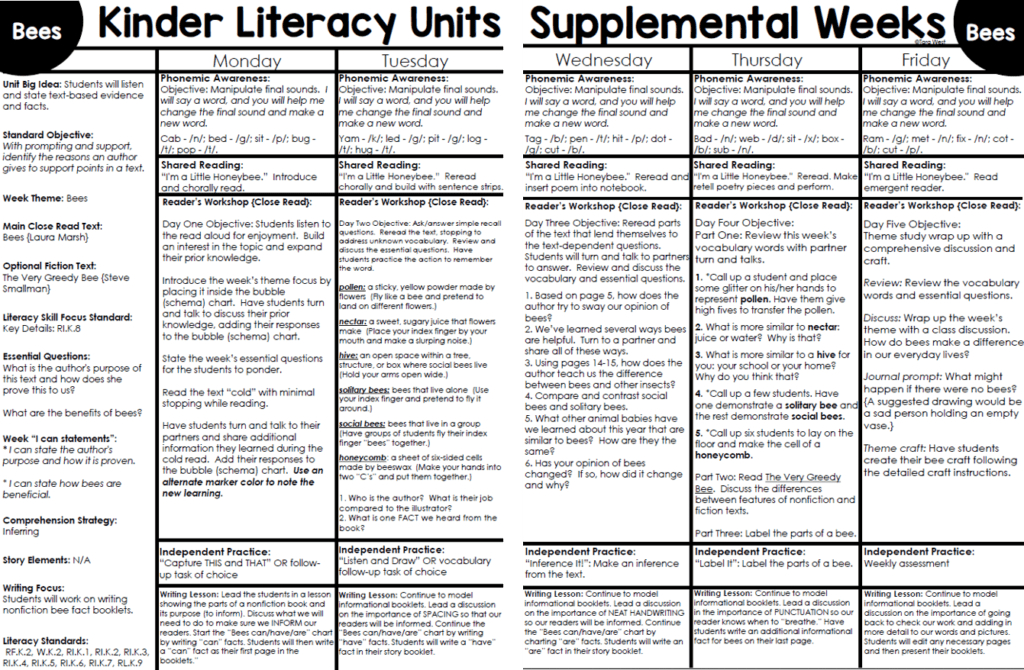

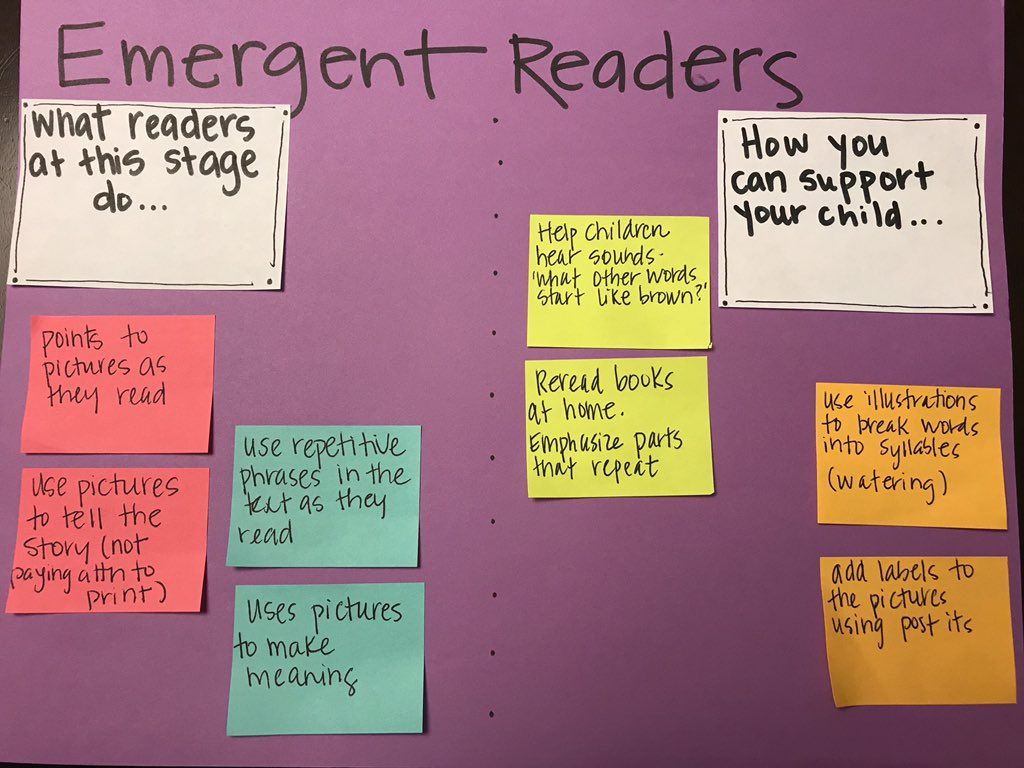

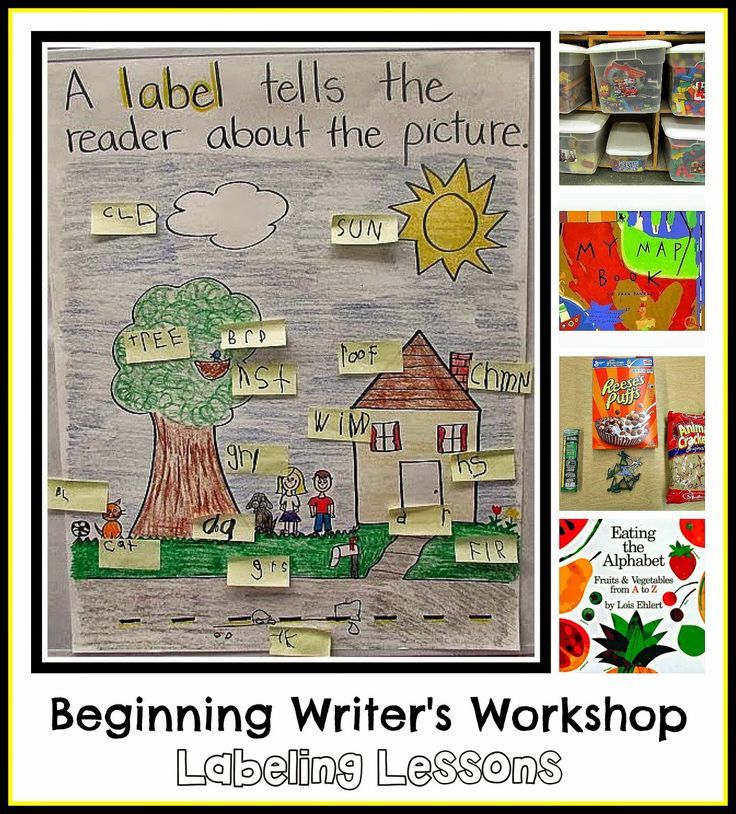

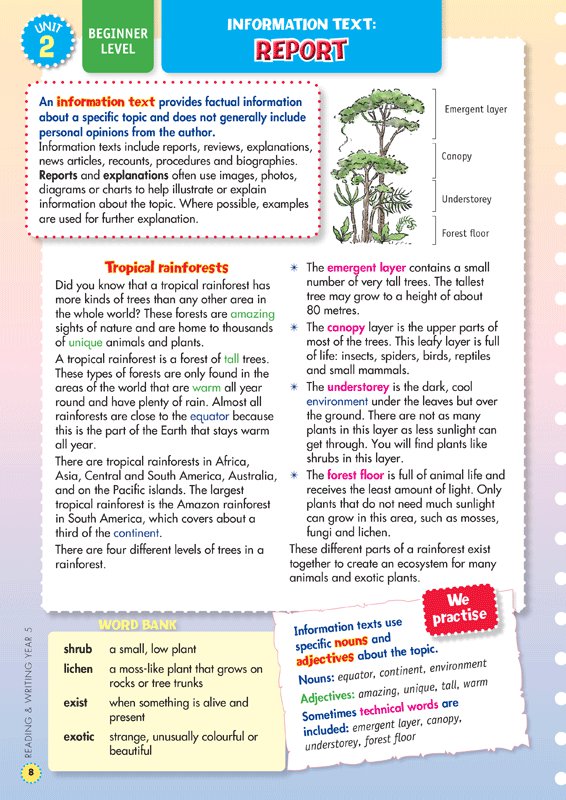

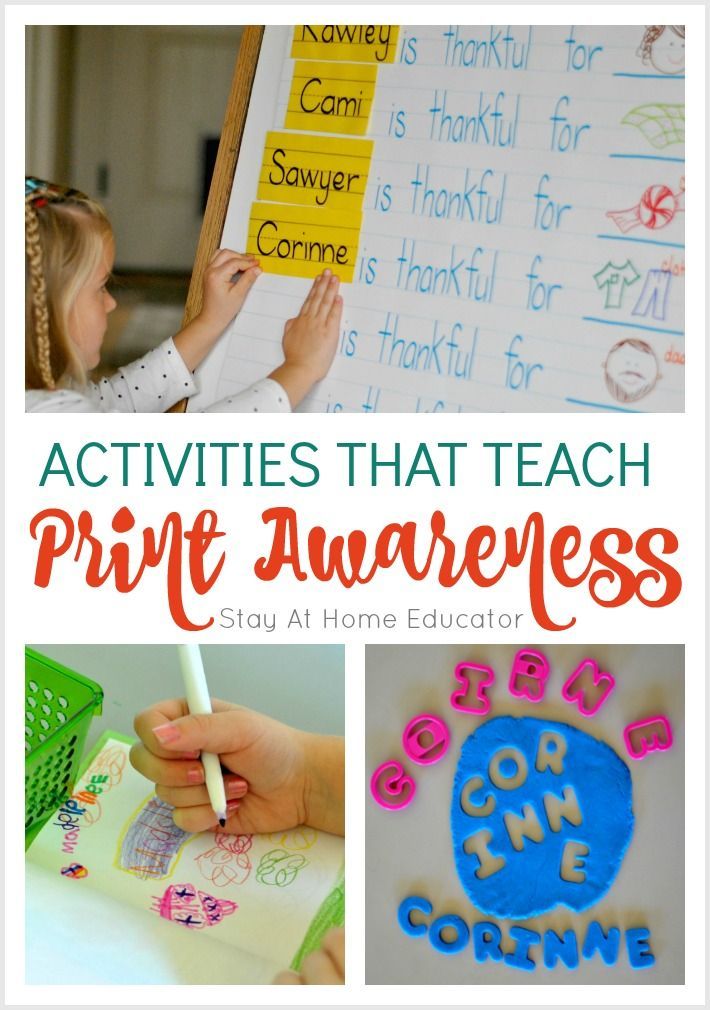

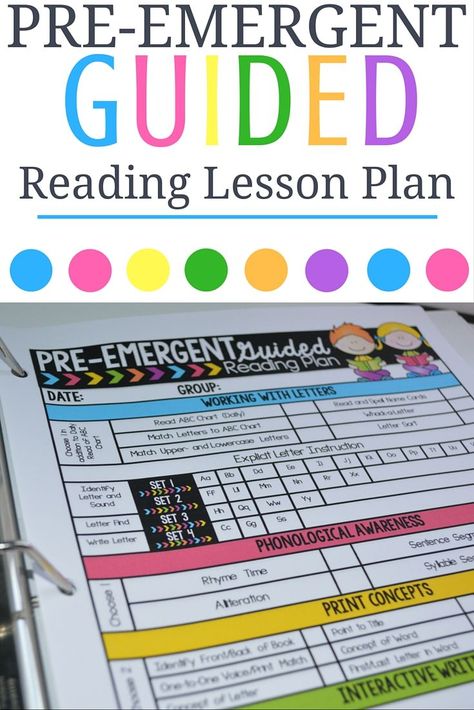

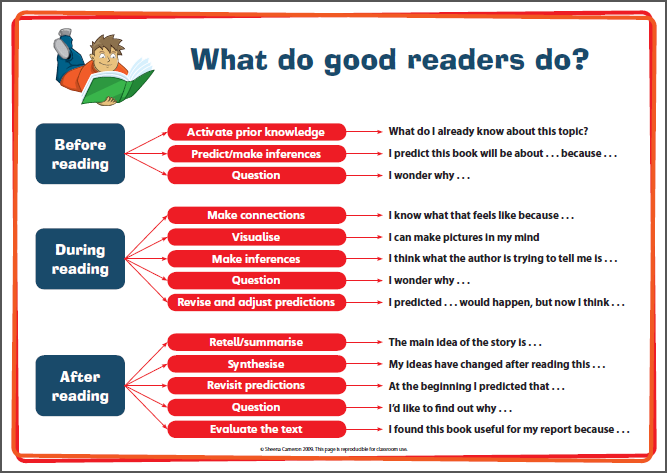

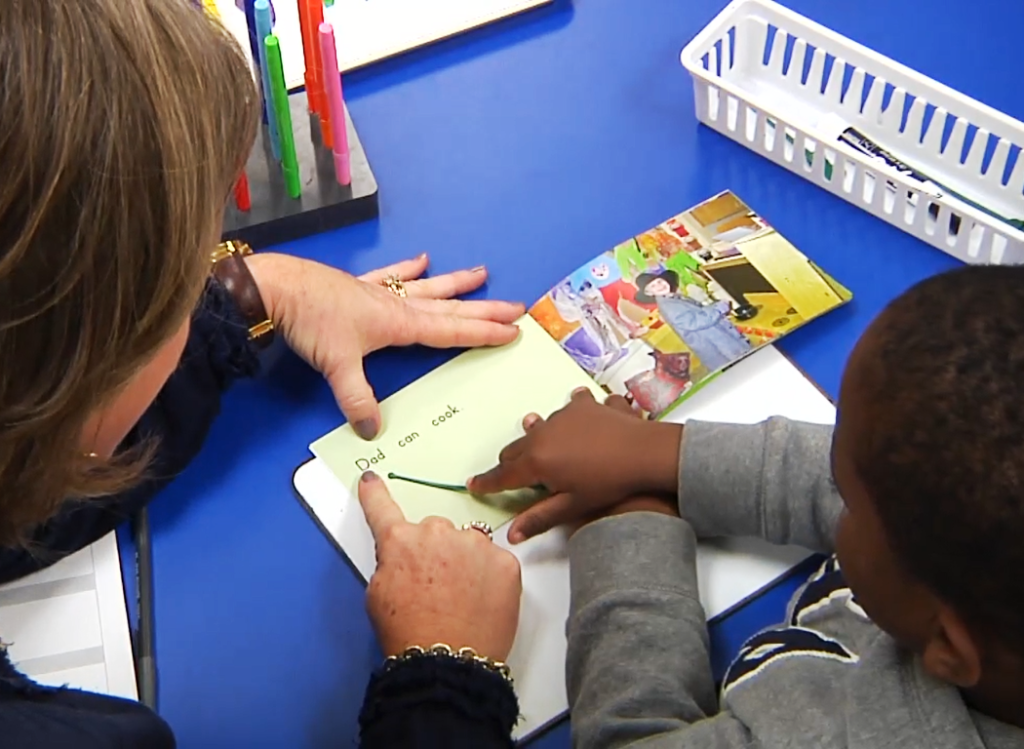

Students who are emerging in their understandings of literacy are working to understand the functions of print and print conventions. Developing phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, and important receptive and expressive language skills will eventually allow students to use reading and writing to interact with others. Emergent readers and writers are making discoveries and learning about literacy when they explore literacy materials, observe print within the natural environment, interact with conventional readers and writers, and see models of how and why print is used (Teale & Sulzby, 1992). Examples of emergent literacy behaviors may include interpreting a story through pictures rather than through text, manipulating books in nonconventional ways (e. g., looking at the book from back to front or holding it upside down), scribbling, and the use of invented spelling (Clay, 1993; Koppenhaver, 2000).

g., looking at the book from back to front or holding it upside down), scribbling, and the use of invented spelling (Clay, 1993; Koppenhaver, 2000).

An emergent reader is one who is interested in books but can’t yet read them independently or may be able to read some words but requires continued support to make meaning from print. It could also be a student who is not yet interested in reading books. An emergent reader may have not yet developed intentional or symbolic means of communication.

A emergent writer is one who is learning to use written language to express communicative intent, and beginning writing is defined as starting with emergent writing (drawing, scribbling, and writing letters) and ending with conventional writing abilities, usually acquired by second or third grade for typically developing children. (Strum, Cali, Nelson, & Staskowski, 2012)

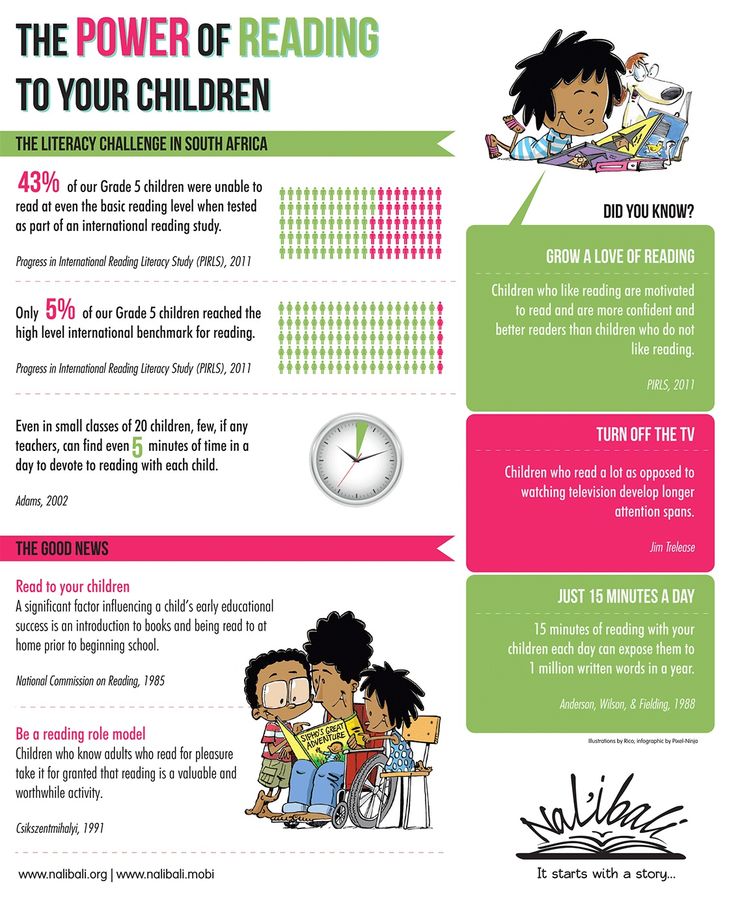

Regular participation in reading and writing activities plays a central role in supporting typical children’s understandings about print. Research in emergent literacy shows that students with significant disabilities, including those with complex communication needs, can benefit from the same type of literacy activities used with typically developing children but may require more time and opportunity. Regular participation in reading and writing activities plays a central role in supporting understandings about print for ALL students.

Research in emergent literacy shows that students with significant disabilities, including those with complex communication needs, can benefit from the same type of literacy activities used with typically developing children but may require more time and opportunity. Regular participation in reading and writing activities plays a central role in supporting understandings about print for ALL students.

Many of the studies and literature surveys the last four decades have a common finding: nothing replaces sound early literacy instruction, even when taking into consideration recent technical advances.

If students with significant disabilities are not exposed to reading and writing materials, how can they learn to use them?

Old assumptions

An emphasis on functional skills, rote memorization, and readiness activities typically take precedence over in-depth literacy instruction (Skotko, Koppenhaver, & Erickson, 2004). Literacy development for 70-90% of students with significant disabilities rarely approached conventional literacy skills expected for typically developing students (Koppenhaver and Yoder, 1992).

- Literacy is learned in a predetermined, sequential manner that is linear, additive, and unitary.

- Literacy learning is school-based.

- Literacy learning requires mastery of certain pre-requisite skills.

- Some children will never learn to read.

New thinking

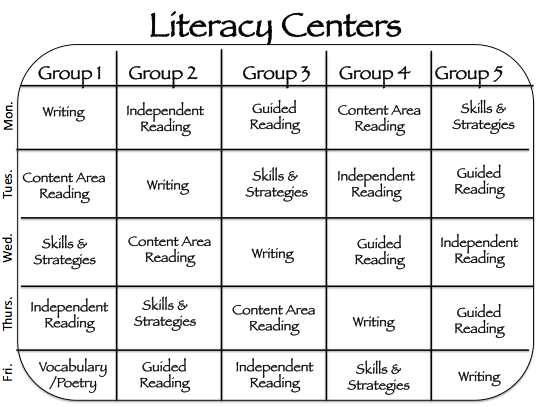

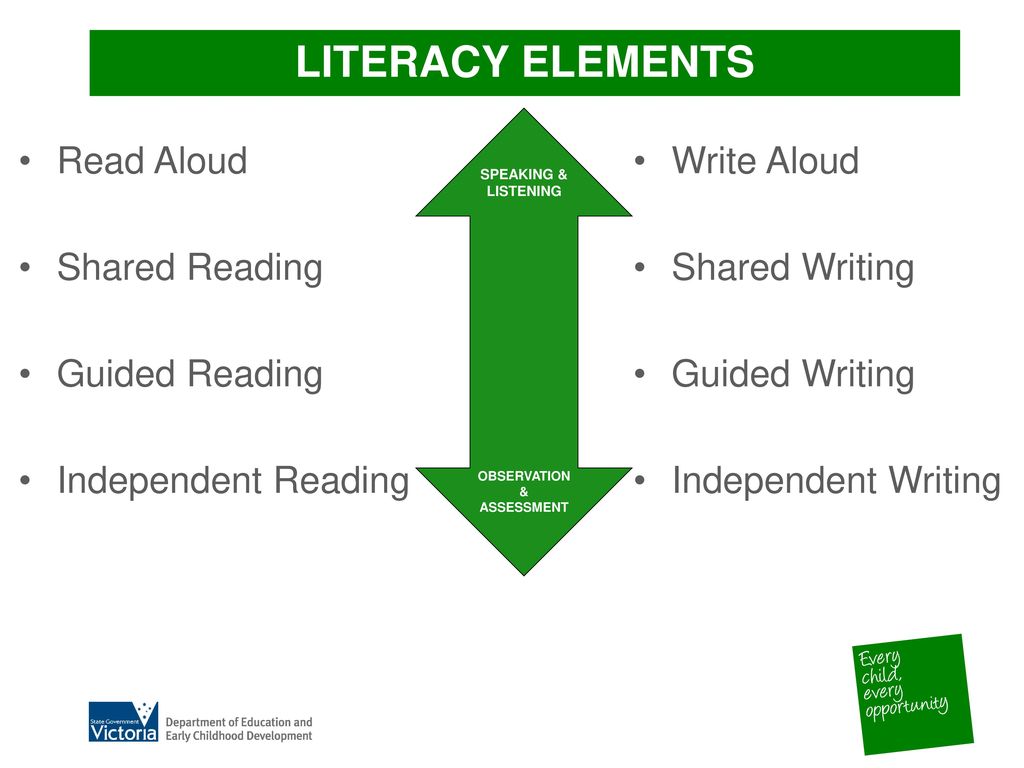

Holistic and explicit instructional approaches to balanced literacy that include daily reading, writing, and word study are critical for all learners, including those with significant disabilities (Erickson, Koppenhaver, & Cunningham, 2006; Sturm & Clendon., 2004).

- Literacy is learned through interaction with and exposure to all aspects of literacy (i.e. listening, speaking, reading, and writing).

- Literacy is a process that begins at birth – there are no prerequisites.

- Literacy abilities/skills develop concurrently and interrelatedly.

- All children can learn to use print meaningfully.

From an emergent literacy perspective, reading and writing develop concurrently and interrelatedly in young children, fostered by experiences that permit and promote meaningful interaction with oral and written language (Sulzby & Teale, 1991), such as following along in a big book as an adult reads aloud or telling a story through a drawing (Hiebert & Papierz, 1989).

Through the concept of emergent literacy, researchers have expanded the purview of research from reading to literacy, based on theories and findings that reading, writing, and oral language develop concurrently and interrelatedly in literate environments (Sulzby & Teale, 1991).

Where can I learn more?

Learning for All – This Alberta resource offers information, strategies and references for school leaders and teachers working with students with significant disabilities. This content was collaboratively developed through Learning for All, a one-year community of practice (2014-2015) for district leaders and consultants.

Literacy, Assistive Technology, and Students with Significant Disabilities. Karen A. Erickson, Penelope Hatch, and Sally Clendon, Focus on Exceptional Children, Volume 42, Number 5, 2010.

Quick Guide #13 “Supporting Literacy Learning in All Children” by David A. Koppenhaver and Karen A. Erickson (pp. 181-194) in Quick Guides for Inclusion: Ideas for Educating Students with Disabilities, 2nd edition

Research Based Practices for Creating Access to the General Curriculum in Reading and Literacy for Students with Significant Intellectual Disabilities. Karen Erickson, Ph.D., Gretchen Hanser, Ph.D., Penelope Hatch, Ph.D., Eric Sanders, M.S./CCC-SLP, 2009.

Karen Erickson, Ph.D., Gretchen Hanser, Ph.D., Penelope Hatch, Ph.D., Eric Sanders, M.S./CCC-SLP, 2009.

Comprehensive Literacy for All is written by Karen Erickson and David Koppenhaver. This is the new version of Children with Disabilities: Reading and Writing the Four-Blocks Way, which was used by the Literacy for All community of practice.

“Literacy improves lives—and with the right instruction and supports, all students can learn to read and write. That’s the core belief behind this teacher-friendly handbook, your practical guide to providing comprehensive, high-quality literacy instruction to students with significant disabilities. Drawing on decades of classroom experience, the authors present their own innovative model for teaching students with a wide range of significant disabilities to read and write print in grades preK–12 and beyond. Foundational teaching principles blend with concrete strategies, step-by-step guidance, and specific activities, making this book a complete blueprint for helping students acquire critical literacy skills they’ll use inside and outside the classroom. ” (Published 2020)

” (Published 2020)

Preview Comprehensive Literacy for All here.

Symbol-based communication | Literacy Instruction for Students with Significant Disabilities

“Communication is when one person shares something the other person did not know they were thinking.”

–Erin Sheldon

SYMBOL-BASED COMMUNICATION

What is symbol-based communication?

Symbol based communication is the “alternative” in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Taking a closer look at the elements of AAC allows us to see where symbol-based communication fits within this context:

- Augment means to add to or to enhance. Almost all speakers and non-speakers augment speech by using eye pointing, vocalizations, gestures and body language.

- Alternative means replacement or substitute. An alternative to speech includes pointing or gazing to symbols, signing or spelling.

- Communication means to send and receive messages with at least one other person.

Symbol-based communication is often used by individuals who are unable to communicate using speech alone and who have not yet developed, or have difficulty developing literacy skills. Symbols offer a visual representation of a word or idea.

“The immediate goal is NOT for students to use all of the symbols we’ve introduced functionally in their own communication but for them to interact with others who are modelling symbol-based approaches to communication.” – Karen Erickson

Which students would benefit from symbol-based communication?

Students whose speech is:

- slow to develop

- difficult to understand (as a back up)

- very limited or non-existent

How can students benefit from symbol-based communication?

Students who are provided authentic and meaningful opportunities to communicate using a symbol-based system across learning and living environments benefit in a multitude of ways including:

- development of language skills

- development of literacy skills

- having more to say to more people

- building relationships and connectedness and belonging

- decreasing frustration/behaviours

- developing a better understanding of the world around them

- making personally meaningful requests, choices and decisions

- increasing participation across environments

- building creativity and self-expression

Examples of symbol-based communication:

Communication boards make language visible and accessible. Core vocabulary is intended to be used across all environments and levels of language competence.

Core vocabulary is intended to be used across all environments and levels of language competence.

A flip book is a communication book with tabs for easy navigation. Vocabulary is arranged by categories, which are indicated on the tabs.

Check out this resource for templates for Low-tech Communication Board options: https://saltillo.com/chatcorner/content/29

Eye-gaze (also known as eye-pointing) is the act of using one’s eyes to direct or redirect the attention of another person. Effective eye-gaze requires participation of both the student and the communication partner. The student fixes their gaze in the direction of the intended message. For example, if a student wants to go outside, they may set their gaze on the door.

An e-tran, or an eye gaze communication board, is a vertically held/mounted board, made of plexiglass or sturdy paper with a window cut in the middle, that enables students to communicate by focusing their gaze on selected items displayed on the board. Items can be displayed in any configuration and can be encoded to provide more choices on each board. Students access the ETran via Partner Assisted Scanning.

Items can be displayed in any configuration and can be encoded to provide more choices on each board. Students access the ETran via Partner Assisted Scanning.

This pragmatically based communication page set is specifically made to help eye gaze users hold simple conversations around a variety of topics and needs.

An iPad communication app allows the user to directly select symbols that are arranged to support a specific topic or serve a communicative function. For example, this page is a list of verbs in alphabetical order- find, fly, give, help. The pages on many apps are dynamic, meaning once the user selects a message, the app will jump to the next logical page.

How can we teach symbol-based communication?

If we expect learners to speak using symbols, we must speak using symbols. Aided Language Stimulation or Aided Language Input is a research-based strategy for teaching symbol-based communication. Essentially, communication partners model or demonstrate symbol-based communication when talking with students who are learning to use symbol-based communication.

A robust and well-organized set of symbols need to be available in order to demonstrate how they can be used to comment, ask questions, make requests, joke, greet, protest and so on at home, school and in the community. Using the same well-organized set of symbols flexibly in all environments supports communication development and language learning over time.

Following are a few points to keep in mind when modeling symbol-based communication:

- Communication partners model, not prompt the students to point or touch the picture symbols to communicate. It is about what the communication partners do, not about what the student does.

- Use the student’s AAC system to model and have conversations.

- Provide models of multiple communicative functions and purposes such as:

- Sharing information: “I heard you went to see Spider Man on the weekend”

- Making comments: “That’s awesome!”

- Asking questions: “What is your favourite colour?”

- Greeting: “Hi! I’m happy to see you today!”

- Requesting: “I want the red ball.

” “I need help.”

” “I need help.” - Protesting/Refusing: “I don’t like that.” “All done.” “Stop!”

- When a student communicates something by looking at an object or making a noise, demonstrate how they could “say it‟ on their AAC system.

- Read and match the student’s non-verbal signals with pictures. Look for what the student communicates with body language and gestures and match those with symbols. For example, if a student puts their head down on the table, the adult could point at tired symbol and say, “You look tired.”

- Point out the main words that you say on the AAC system.

- Whenever the student uses their AAC system, model their message back in a slightly longer form. For example, when the student points to ‘book’ on their AAC system, point out ‘want book’ as you say, “You want a book?‟ Then point out ‘get book’ as you say, “OK. I’ll get you a book‟.

- Model only a few more words per utterance than the student is using – this way the modeling is not too hard for the student to copy.

What is core vocabulary?

About 85% of our English spoken language is comprised of 250-350 words. Core vocabulary is a relatively small set of words that have been determined to be highly useful for communicating in both social and academic contexts. Core vocabulary is primarily composed of pronouns, verbs, descriptors, and prepositions. There are very few nouns.

The DLM Core Vocabulary Project was initiated to determine the vocabulary that is necessary for students with significant cognitive disabilities to engage, learn, and demonstrate knowledge in an academic environment.

These words have been extensively researched by the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies for words needed for AAC Core vocabulary and Academic Core Vocabulary.

Where can I learn more?

Aided Language Videos

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vUY6oQoSTXw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=flFNMky22-U

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Beginning Communicators

This module describes symbolic and non-symbolic forms of communication, the distinction between pre-intentional and pre-symbolic communicators, and identifies additional sources of support for building communication skills.

Online Self-directed Module

Facilitated Module Materials for Groups

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Core Vocabulary

Core Vocabulary is a list of words that have been determined to be highly useful for communicating in both social and academic contexts. https://www.med.unc.edu/ahs/clds/resources/core-vocabulary

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Core Vocabulary and Communication

This module focuses on the use of core vocabulary as a support for communication for students who cannot use speech to meet their face-to-face communication needs and require augmentative and alternative communication.

Online Self-directed Module

Facilitated Module Materials for Groups

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Speaking and Listening

This module addresses speaking and listening in the broader context of expressive and receptive communication for students with significant cognitive disabilities. The content in this module is important to understand the DLM Essential Elements in Speaking and Listening and across all of the strands of Essential Elements in English language arts.

Online Self-directed Module

Facilitated Module Materials for Groups

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Supporting Participating in Discussion

Participants will review the goals of supporting participation in discussion and the need of an expressive means of communication for all students. Participants will also be given 5 strategies to use in supporting students during discussions with teachers and peers.

Online Self-directed Module

Facilitated Module Materials for Groups

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) – Symbols

This self-directed module provides an overview of symbols to support communication and interaction. It also describes the use of symbols and photographs in text.

Online Self-directed Module

Facilitated Module Materials for Groups

Language Stealers (video 2:52 min)

Language Stealers reveals the real barriers to communication for learners with speech and motor impairments as being no access to language and literacy.

Noun Town

This short presentation shares the importance of using high frequency words, instead of living in ‘noun town’. Share the story of Noun Town to illustrate how important it is to include core vocabulary in all settings. For a print version, visit AAC Language Lab. You’ll need to do a search for Noun Town (it shows up under Activities) and then you can download it.

Pragmatic Organization Dynamic Display (PODD) communication books were developed in Australia by Gayle Porter, originally for children with cerebral palsy. Their structured organization and emphasis on visual communication means that they are also a valuable tool for developing the communication of those with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Porter & Cafiero, 2009). http://praacticalaac.org/praactical/how-i-do-it-using-podd-books-and-aided-language-displays-with-young-learners-with-autism-spectrum-disorder

Project Core

The Project Core implementation model is aimed at helping teachers provide students with significant cognitive disabilities and complex communication needs with access to a flexible Universal Core vocabulary and evidence-based instruction to teach them to use core vocabulary via personal augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems. http://www.project-core.com

http://www.project-core.com

Symbols and Learning to Read

In this short video clip, Dr. Caroline Musselwhite talks about how symbols can affect the reading process and to be effective supports in learning to read, symbols must be used thoughtfully. A Learning Guide accompanies the video.

Tar Heel Reader

Tar Heel Reader is a growing library of accessible, beginning level readers for students of all ages from the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies. It includes a collection of free, easy-to-read (core words), and accessible books on a wide range of topics. Each book can be speech enabled and accessed using multiple interfaces, including touch screens, the IntelliKeys with custom overlays, and 1 to 3 switches. https://tarheelreader.org

Tar Heel Shared Reader

Developed by a team at the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, this variation of the popular Tar Heel Reader website emphasizes shared reading and provides PCS symbol support for core words that can be used in discussing each book. A comprehensive set of free professional development modules provide training and examples of Tar Heel Shared Reader teaching practices. Each module requires between 45-60 minutes to complete. Various formats allow for flexibility in order to best meet scheduling needs. https://www.sharedreader.org

A comprehensive set of free professional development modules provide training and examples of Tar Heel Shared Reader teaching practices. Each module requires between 45-60 minutes to complete. Various formats allow for flexibility in order to best meet scheduling needs. https://www.sharedreader.org

Top 10 Tips for Partner Assisted Scanning, Gretchen Hanser, Ph.D., Center for Literacy and Disability Studies, 2007.

The role of reading in the development of literacy and the formation of a graphic lexicon

The role of reading in the development of literacy and the formation of a graphic lexicon

- Rogova Julia Anatolyevna

The role of reading in the development of literacy and the formation of a graphic lexicon 9

Primary school teacher It is known that each child goes through his own individual way of mastering his native language before school and during schooling.

This path is corrected, clarified, expanded, consolidated thanks to the purposeful school teaching of the Russian language (the school curriculum) and the activities of the teacher, aimed at achieving the most competent development of writing by the student.

This path is corrected, clarified, expanded, consolidated thanks to the purposeful school teaching of the Russian language (the school curriculum) and the activities of the teacher, aimed at achieving the most competent development of writing by the student. Observing the success of their students in mastering the written native Russian language for a number of years, it can be seen that the following conditions contribute to a faster, stronger and more conscious spelling and literacy.

- Development of cognitive processes

(memory, attention, perception, thinking) according to the child's age. Without the proper level of formation of these psychological processes, the success of any activity (including educational activities), and especially the process of language acquisition, is impossible.

-

. A child who wants to study well, properly motivated to overcome difficulties and failures in the process of learning activities, will be able to achieve his goal by making the best of his efforts.

. Parents of those children who write competently, most often, in childhood also did not have any particular difficulties in mastering the written native language. And, conversely, for parents who recall school lessons of the Russian language with fear or neglect, children also do not consider these lessons easy and loved. More often than not, spelling remains a mystery to them.

-

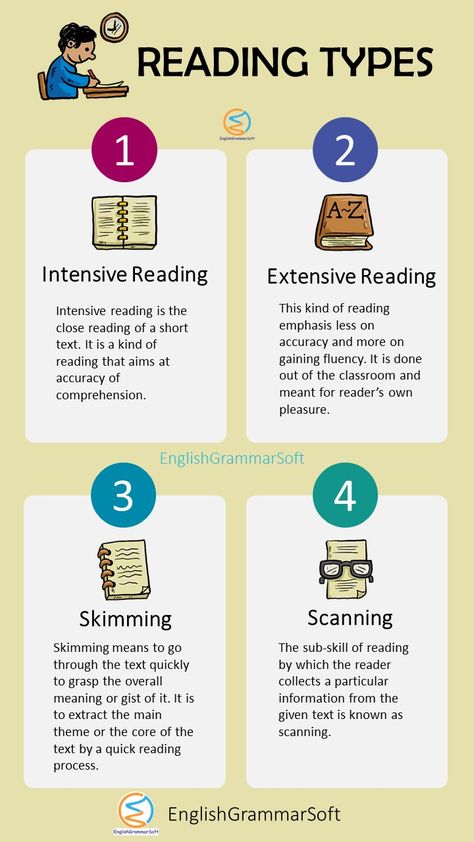

I would like to dwell on the last fact in more detail and discuss how the reading process affects the student's successful mastery of spelling and literacy and what kind of reading affects literacy.

Undoubtedly, the individual language system of a person, both in oral and written form, is built on the basis of his perception of oral and written speech, his oral and / or speech experience, which allows him to work out and polish emerging speech skills. The dependence of a child's literacy on his experience of writing, and especially reading, was noted by many researchers, including A. N. Gvozdev [Gvozdev 1934]. How the process of mastering reading takes place at the early stages, how it is connected with writing (typing) depends on the further mastery of a person's native language in its oral form.

N. Gvozdev [Gvozdev 1934]. How the process of mastering reading takes place at the early stages, how it is connected with writing (typing) depends on the further mastery of a person's native language in its oral form.

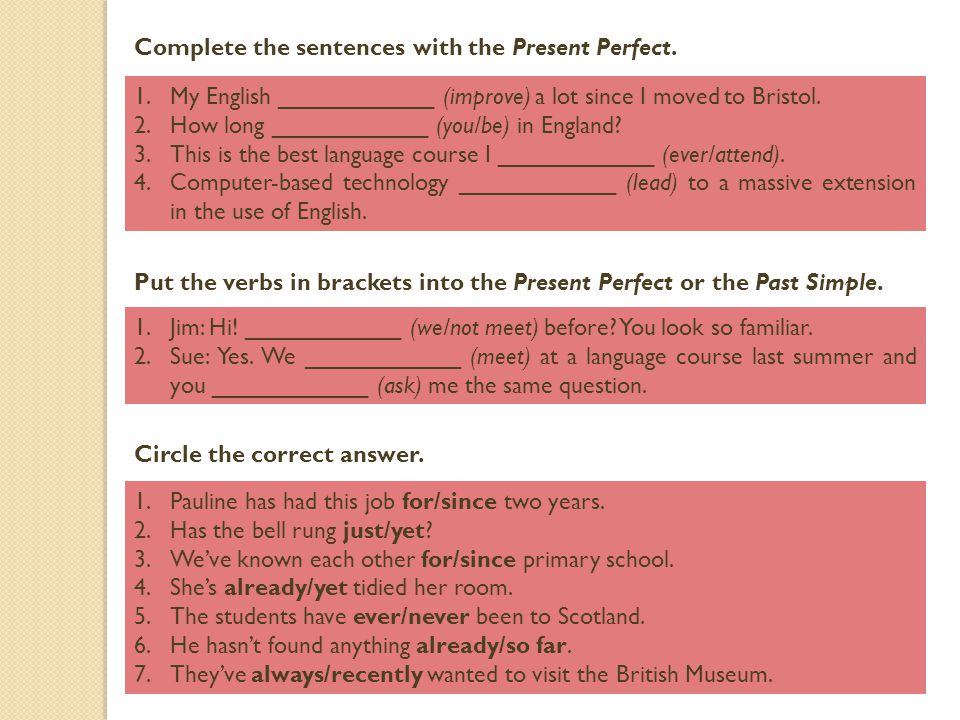

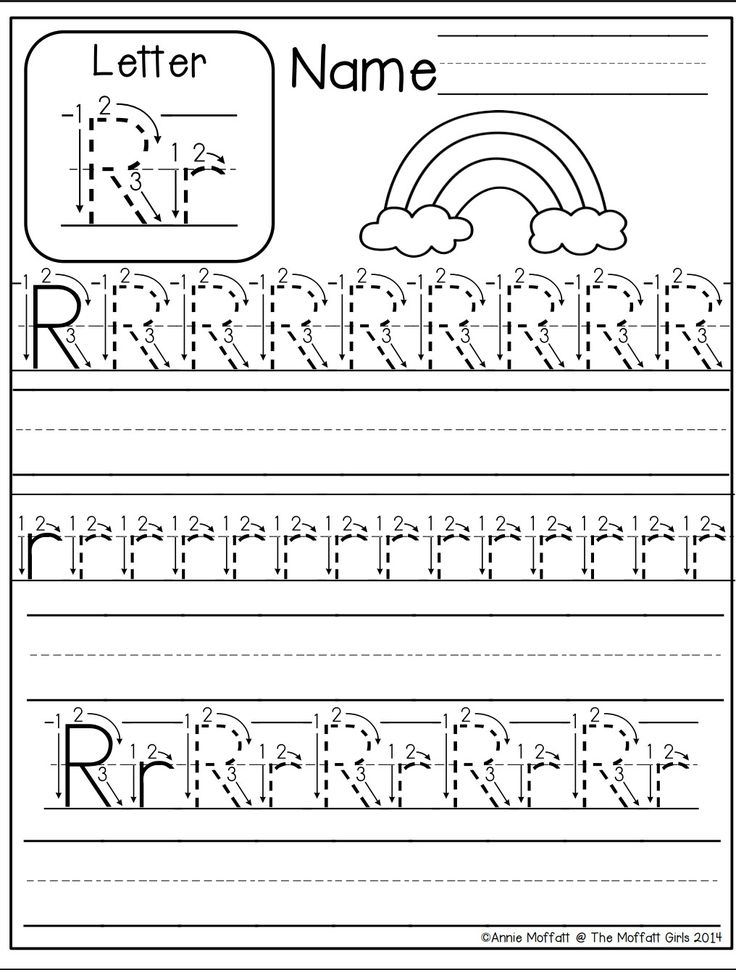

How is reading habit formed? An adequately developing reading skill is based on the constant work of sequential perception - therefore, it is easily formed in those children for whom this method of perception is the leading one (left hemisphere). The main stages in the formation of this skill are:

a) combining letters into syllables;

b) slow syllable-by-syllable reading;

c) slow continuous syllabic and at the same time expressive reading;

d) continuous fluent expressive reading, when the child runs his eyes over the entire word from left to right, determines the speed of his reading himself, and if he comes across an unfamiliar word, then the child automatically returns to the previous level for a while - to a slow continuous syllabic or even to a slow syllabic reading [Patyaeva 2007: 154-161].

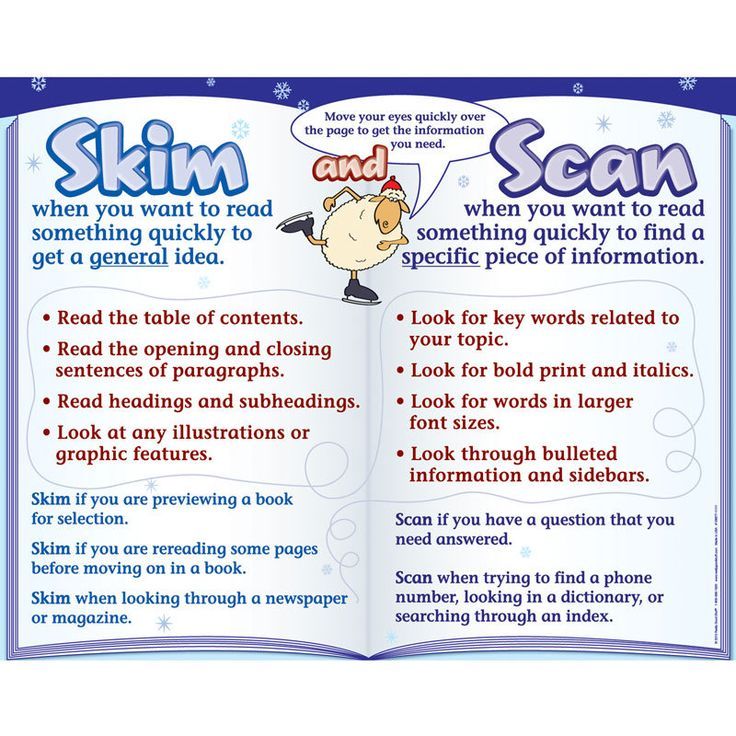

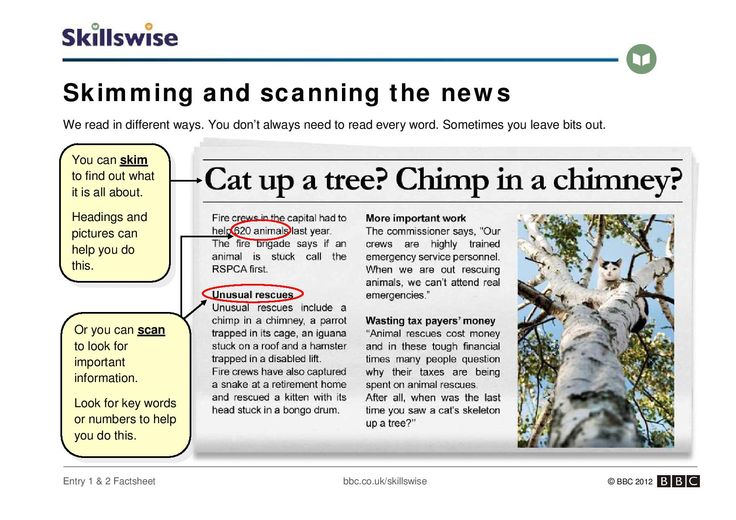

Researcher A.A. Kosenko discusses the importance of the way of reading on the developing skill of writing [Kosenko 2008]. He welcomes slow, unhurried reading and protests against "speed reading". The author believes that it is the way of reading that lies in line with the development of literate writing - it is adequate to the process of writing. “This happens because the child, reading the word, runs over it with his eyes from beginning to end. And the process of writing words is also the process of deploying a word from left to right. Both in writing and in the first way of reading, sequential slow perception works for us. But with the second (high-speed) way of reading, we turn on a holistic instantaneous perception. And as a result, many children do not develop a literate letter even at the pre-spelling level, that is, they continue to make pre-spelling errors (missing letters, confusing them, rearranging them) until grade 11" [Kosenko 2008].

Therefore, it becomes clear that the way of reading, which the school forces the student to, and she forces him to complete reading, arranging training with a stopwatch, will interfere with the development of writing skills. At the same time, the folding of the skills of understanding the text is also violated: “swallowing” the endings, the child does not grasp the syntactic connections of words, and since he also “reads” some of the words incorrectly, the meaning of the sentence very often eludes him - which, in turn, is not noticed by the teacher , tracking standards for reading speed. As a result, a very bad habit is developed - to read just like that, without thinking about what you read.

At the same time, the folding of the skills of understanding the text is also violated: “swallowing” the endings, the child does not grasp the syntactic connections of words, and since he also “reads” some of the words incorrectly, the meaning of the sentence very often eludes him - which, in turn, is not noticed by the teacher , tracking standards for reading speed. As a result, a very bad habit is developed - to read just like that, without thinking about what you read.

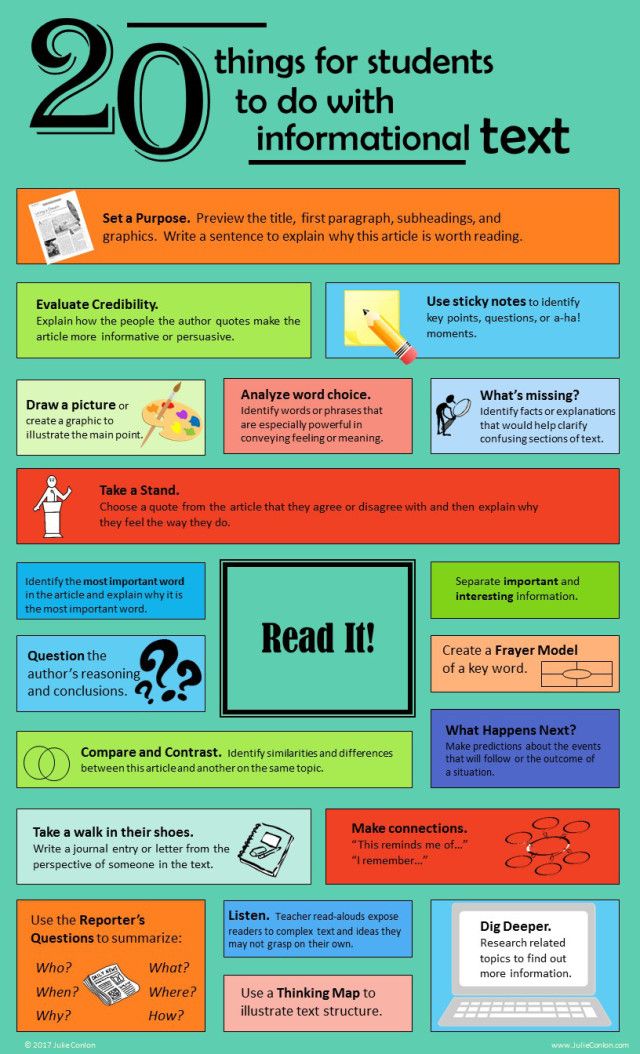

Therefore, reading always, and especially at the early (initial) stages of education (grades 1-2, and sometimes grade 3) should be thoughtful, conscious, attentive and unhurried.

In my opinion, reading is certainly a significant factor that can influence the growth of a student's literacy. But reading at the same time should be systematic, thoughtful. Reading from case to case does not give the proper and desired effect. For the formation of a mental graphic lexicon, multiple, repeated collision of the child's gaze with the word is necessary. The image of the word must be unconsciously imprinted in the mind of the child and at the right moment (for recording) break out of the "dark field" of consciousness.

The image of the word must be unconsciously imprinted in the mind of the child and at the right moment (for recording) break out of the "dark field" of consciousness.

Thus, the formation of a child's literacy when mastering the written native Russian language is influenced by many factors sometimes beyond his control. The task of the parent and teacher is to make the process of learning the native language personal, individual and interesting for the child.

- Gvozdev AN To the question of the role of reading in the assimilation of spelling // Russian language and literature in secondary school. M.: Uchpedgiz, 1934. -S. 22-34.

- Kosenko A.A., Patyaeva E.Yu. The influence of the leading type of perception on the development of reading and literate writing skills. M., 2008.

- Patyaeva E.Yu. From birth to school. The Thinking Parent's First Book. M.: Meaning, 2007.

- Back

- Forward

You have no rights to post comments

Login

Remember me

Registration

- Forgot your login details?

- Registration

Website translation

Details and discounted registration

Lesson 7: Written Literacy

Traditionally, literacy refers to the ability to read and write in one's native language. At the same time, with the spread of universal school education, the requirements for literate people have increased: it is no longer just a question of them being able to read and write, but writing in accordance with established norms of grammar and spelling. Without exaggeration, we can say that today's community of readers and writers is divided into two camps: ardent advocates of literacy and, of course, not its opponents, but those who treat it without any reverence. The former are jokingly nicknamed grammar nazi, as they demand strict adherence to the rules of grammar and are ready to pass a death sentence on a text in which they have managed to detect the slightest error. Their opponents reasonably notice that the main thing in the text is the content, and the language is not a frozen set of rules, but a living and developing entity, the norms of which are constantly changing. In this lesson, we will talk about how important literacy is when writing texts and how to develop it in yourself.

Their opponents reasonably notice that the main thing in the text is the content, and the language is not a frozen set of rules, but a living and developing entity, the norms of which are constantly changing. In this lesson, we will talk about how important literacy is when writing texts and how to develop it in yourself.

Contents

- When it is necessary and not necessary to write correctly

- How to learn to write correctly?

- Verification test

When it is necessary and not necessary to write correctly

Perhaps this statement will seem seditious to many, but we will give the following advice: write without paying attention to grammar. The fact is that often an excessive concentration of attention on grammatical rules interferes with writing. It is difficult for a person to instantly clothe his thoughts in an ideal form from a grammatical point of view. As a result, his work stalls on a few sentences, and he is no longer able to move on. Therefore, it is useful to practice the so-called free writing ( free writing ), during which a person simply expresses his thoughts without correcting typos and errors, without thinking about punctuation and the correct construction of sentences.

Therefore, it is useful to practice the so-called free writing ( free writing ), during which a person simply expresses his thoughts without correcting typos and errors, without thinking about punctuation and the correct construction of sentences.

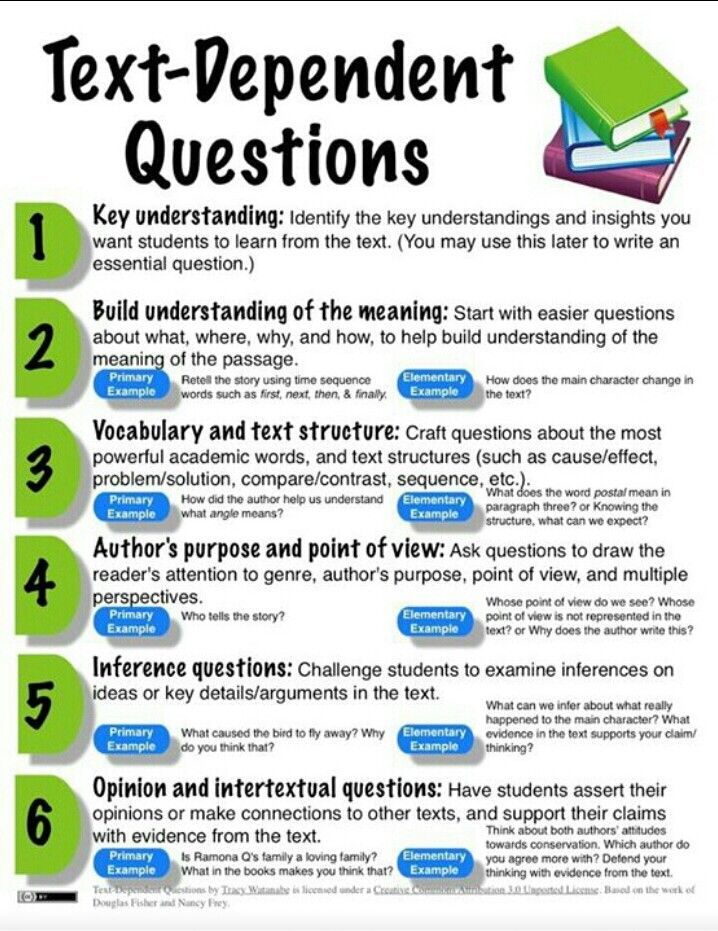

However, this does not mean that one can forget about grammar altogether. The written text is not the final product yet, it is just a draft that is subject to multiple editing. Moreover, the last stage of editing is checking for compliance with the language rules and correcting all possible language errors. Thus, our advice in full is: do not pay attention to grammar in the process of writing, but re-read the finished text several times and correct errors.

Why is it important to write well in the end? Let's start with the fact that the rules of language are not arbitrary institutions of linguists, invented in order to torment people. They developed naturally in the course of the historical development of the language, and their role is to unify the ways of writing so that we can understand each other's texts. If a unified grammar did not exist, then written communication would be impossible. Therefore, it is not necessary to consider the observance of grammatical rules as a favor that you are doing to a teacher or a linguist. Remember that this is a condition for the existence of writing in general.

If a unified grammar did not exist, then written communication would be impossible. Therefore, it is not necessary to consider the observance of grammatical rules as a favor that you are doing to a teacher or a linguist. Remember that this is a condition for the existence of writing in general.

Further, poorly written text repels the reader. Firstly, if the text contains many obvious errors, this indicates that the author did not even bother to re-read his creation. Hence the reader makes a legitimate conclusion that the author does not respect him, slipping him an unfinished work. And if the author was not guided by the reader, then why read his text at all? Secondly, human perception is arranged in such a way that even if we ourselves make mistakes when writing, we will certainly see them in someone else's text. This means that many readers, without noticing it themselves, in the process of reading turn into those same Grammar Nazis. At the same time, many tend to reason like this: if the author has not managed to master the school grammar, then is it worth taking his text seriously at all; most likely, he has problems with logic, with the ability to structure his thoughts, with the depth of study of the material, etc. Although such reasoning is by no means always correct, without thinking about grammar, the author can lose a significant share of readers.

Although such reasoning is by no means always correct, without thinking about grammar, the author can lose a significant share of readers.

On top of that, the commonplace argument - "It's the content that matters, not the form" - is incorrect. Communication researchers have long formulated the following principle: “The medium is the message”, i.e. "The medium of communication is the message." The principle, if you think about it, is pretty obvious. At least writers have been using it since ancient times. If we apply this principle to our topic, it turns out that the form is inseparable from the content, it also works for its production. The simplest illustration of this thesis is that errors (especially punctuation) obscure the meaning of the text.

Finally, non-compliance with the rules of the Russian language can lead to a comic effect, which the author did not intend to create. For example, seeing the inscription “The 10th Congress of Journalists”, everyone immediately understands that the Congress is poorly organized, and the journalists came to it so-so. Although in this case it is obvious that a negative characterization of the congress was not included in the author's plans.

Although in this case it is obvious that a negative characterization of the congress was not included in the author's plans.

As well as the importance of literate speech, we analyze in this video:

How to learn to write correctly?

In theory, a Russian language course in secondary school provides us with all the necessary knowledge to write correctly. Unfortunately, practice shows that many fail to master it. Of course, we cannot list and explain all the rules of the Russian language in this lesson. Our goal is to give a few simple tips that will tell you how to fill in the gaps in your knowledge of the Russian language on your own if you have the appropriate motivation.

There is a popular belief that one can learn to write correctly by reading a lot of good classical literature. It is based on the belief that when reading, people acquire the visual appearance of the word and then, in the process of writing, restore it with the help of visual memory. In our opinion, the importance of reading for the development of literacy is somewhat overestimated. Of course, reading quality literature is always useful. This will enrich the vocabulary and help to form a good style. However, when it comes to literacy, there are several problems. Firstly, not everyone has a developed visual memory, especially for small details. Secondly, when reading, people are usually absorbed in the content of the text and do not set themselves the goal of paying special attention to the spelling of words or the construction of sentences. Finally, many errors arise not because a person does not know how this or that word is spelled, but because of the wrong declension, misunderstanding the difference between -tsya and -tsya , confusion in continuous and separate writing, incorrect punctuation marks, etc.

It is based on the belief that when reading, people acquire the visual appearance of the word and then, in the process of writing, restore it with the help of visual memory. In our opinion, the importance of reading for the development of literacy is somewhat overestimated. Of course, reading quality literature is always useful. This will enrich the vocabulary and help to form a good style. However, when it comes to literacy, there are several problems. Firstly, not everyone has a developed visual memory, especially for small details. Secondly, when reading, people are usually absorbed in the content of the text and do not set themselves the goal of paying special attention to the spelling of words or the construction of sentences. Finally, many errors arise not because a person does not know how this or that word is spelled, but because of the wrong declension, misunderstanding the difference between -tsya and -tsya , confusion in continuous and separate writing, incorrect punctuation marks, etc. In this case, reading is completely useless: you need to know the rules. Thus, read as much as possible, but to improve your literacy, follow these recommendations:

In this case, reading is completely useless: you need to know the rules. Thus, read as much as possible, but to improve your literacy, follow these recommendations:

1

Reread your text after writing. Most mistakes are due to inattention. If the author is completely absorbed in the process of formulating his thoughts, then he can no longer follow the spelling of words or the placement of commas. A simple check will help you easily identify and correct errors and typos. It may also be helpful to reread your text backwards. This technique will allow you to get rid of the effect of sliding your eyes over the text and get a grasp of each individual word.

2

Use the spelling and punctuation check built into the text editor. Naturally, such a check is not perfect: text editors often do not know many words and cannot correctly understand the syntax, but they will at least help correct some gross errors and point out fragments that require increased attention. Many people are annoyed by the constant underlining of words and sentences with colored lines. In this case, you can disable the built-in check during the writing process, but enable it while editing the text.

In this case, you can disable the built-in check during the writing process, but enable it while editing the text.

3

Use Russian dictionaries and reference books. Educated is not the one who knows everything, but the one who knows where to find the necessary information. There is nothing catastrophic in the fact that a person does not know or does not remember some rules, no. The main thing is not to forget, if necessary, to look into the right book. Here is a small list of dictionaries and reference books on the Russian language that are useful to have at hand (or bookmarked):

- Rosenthal D.E. A guide to spelling, pronunciation, literary editing

- Lopatin V.V. Rules of Russian spelling and punctuation. Complete academic reference book

- Spelling Dictionary of the Russian Language

- Explanatory dictionary of the Russian language

- Buchkina B.Z., Kalakutskaya L.P. Together or separate? (Experience dictionary-reference)

- Kolesnikov N.

P. Words with Double Consonants: Reference Dictionary

P. Words with Double Consonants: Reference Dictionary - Dictionary of foreign words

- Zaliznyak A.A. Grammar Dictionary of the Russian Language

- Rosenthal D.E. Management in Russian: Dictionary-Reference

4

Make tables and charts. They are the perfect way to structure and remember complex material. For example, you can make a table of noun declensions or punctuation patterns in compound sentences. In principle, there are already ready-made reference books "Russian in tables and diagrams", but we advise you to create tables yourself. To do this, you will need to really understand the topic, which will certainly help memorize it, and you will be able to organize the material in the way that is most convenient for you. It is convenient to keep such tables on the desktop and refer to them in case of doubt about a particular rule.

5

Familiarize yourself with basic morphology and syntax. Their knowledge is the key to spelling.

Their knowledge is the key to spelling.

The same applies to the syntax. You need to be able to distinguish its constituent parts in a sentence: subject, predicate, definition, object, circumstance, application, introductory construction. All punctuation rules are built precisely on this ability to highlight the members of a sentence. If you learn to see the structure of words and sentences, remembering and applying the rules will no longer be difficult for you.

6

If spelling is your weak point, try one of the following techniques. First, check unstressed vowels in the root by selecting words with the same root, where these main ones are stressed. For example, recently I encountered the following error: "I have recovered from this disease." It is correct to write “ cured ”, and this is easy to check using the words “ heals ” and “ healer ”. Secondly, try writing difficult words on a sticker, highlighting problematic letters in font size and color: " privilege ”, “ Saturday ”. Thirdly, you can use the method of associations. As an illustration, in the word " milk " unstressed vowels in the root can be associated with bagels that we eat with milk, and which are shaped like the letter "O". They remembered bagels, they remembered how the word is spelled. Finally, try to memorize typical cases. This method can be especially effective for memorizing the continuous and separate spelling of words. For example, firmly remembering that the word " vice-president " is written with a hyphen, you will no longer experience difficulties with words like it: "deputy prime minister", "vice consul", etc.

Thirdly, you can use the method of associations. As an illustration, in the word " milk " unstressed vowels in the root can be associated with bagels that we eat with milk, and which are shaped like the letter "O". They remembered bagels, they remembered how the word is spelled. Finally, try to memorize typical cases. This method can be especially effective for memorizing the continuous and separate spelling of words. For example, firmly remembering that the word " vice-president " is written with a hyphen, you will no longer experience difficulties with words like it: "deputy prime minister", "vice consul", etc.

7

If punctuation is especially difficult, then it is useful to remember that punctuation marks are designed to reflect pauses and intonational nuances of speech in writing. Therefore, it can be helpful to read the sentence aloud and pay attention to how you pronounce it, where you pause, what words you put emphasis on. Where you notice pauses and accents, there should be punctuation marks. Here are all the general tips that can be given regarding the development of literacy.

Here are all the general tips that can be given regarding the development of literacy.

8

Online course "Russian Language"

There are not so many topics of the Russian language in which people most often make mistakes - about 20. We decided to devote the course "Russian Language" to these topics. In the classroom, you will get the opportunity to work out the skill of competent writing using a special system of multiple distributed repetitions of the material through simple exercises and special memorization techniques.

Test your knowledge

If you would like to test your knowledge of the topic of this lesson, you can take a short test consisting of several questions. Only 1 option can be correct for each question. After you select one of the options, the system automatically moves on to the next question. The points you receive are affected by the correctness of your answers and the time spent on passing. Please note that the questions are different each time, and the options are shuffled.