Help a child to read

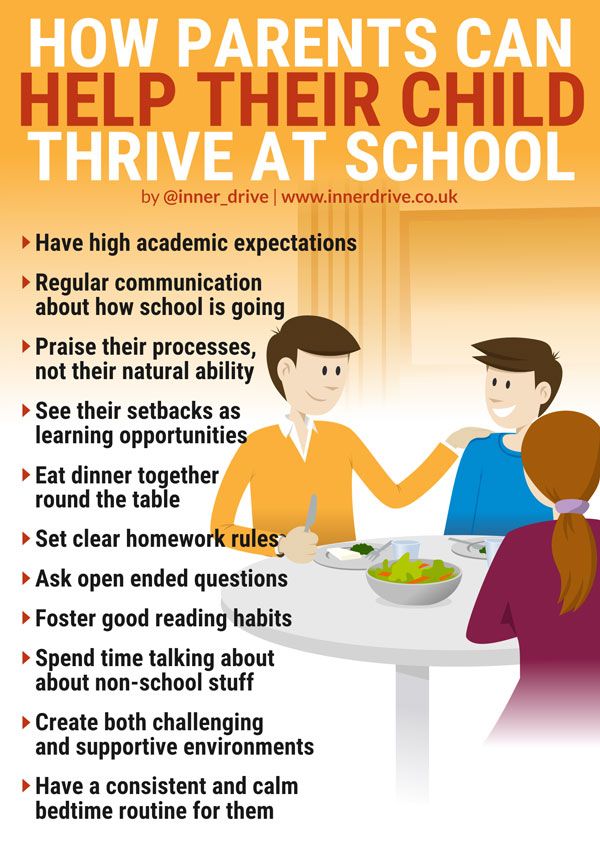

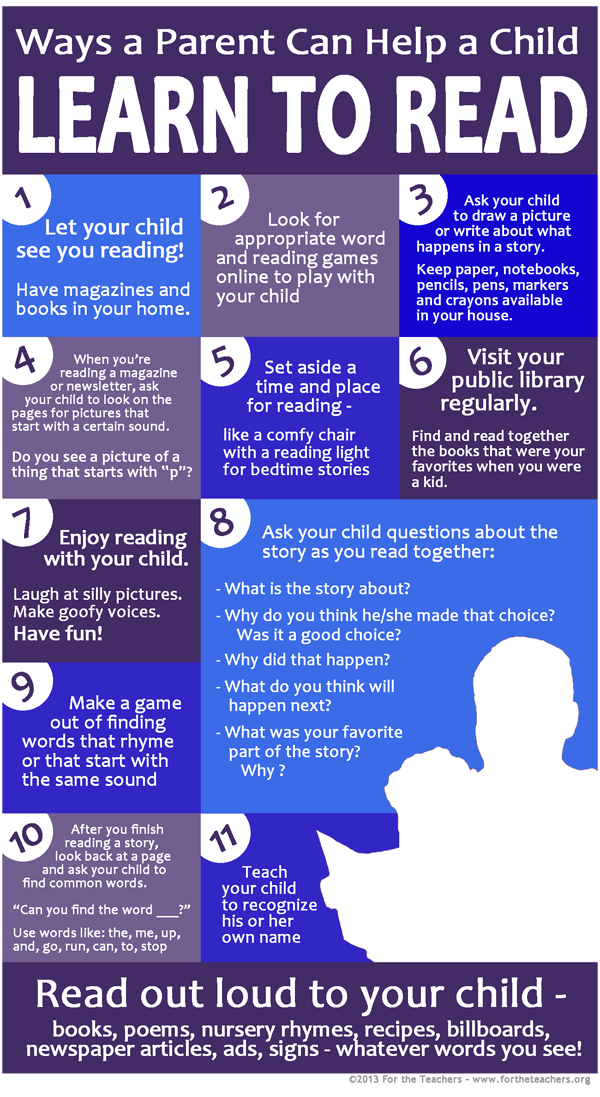

11 Ways Parents Can Help Their Children Read

Parents often ask how they can help their children learn to read; and it’s no wonder that they’re interested in this essential skill. Reading plays an important role in later school success. One study even demonstrates that how well 7-year-olds read predicts their income 35 years later!

Here are 11 practical recommendations for helping preschoolers and school-age students learn to read.

1. Teaching reading will only help.

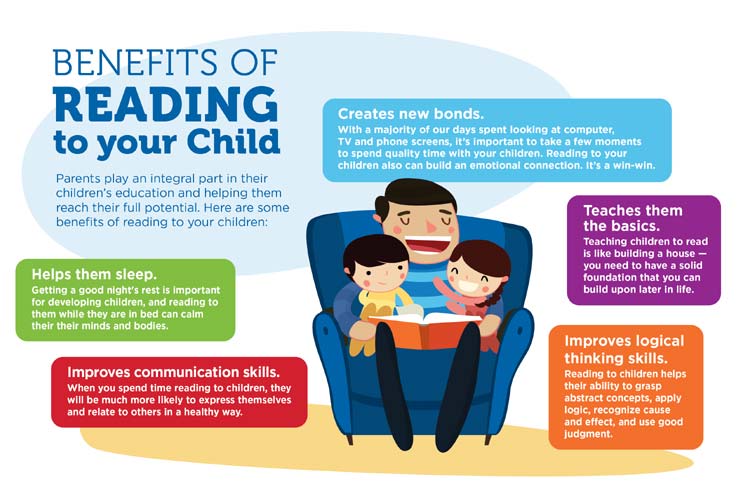

Sometimes, parents are told early teaching is harmful, but it isn’t true. You simply can’t introduce literacy too early. I started reading to my own children on the days they were each born! The “dangers of early teaching” has been a topic of study for more than 100 years, and no one has ever found any convincing evidence of harm. Moreover, there are hundreds of studies showing the benefits of reading to your children when they are young.

2. Teaching literacy isn’t different than teaching other skills.

You don’t need a Ph.D. to raise a happy, healthy, smart child. Parents have been doing it for thousands of years. Mothers and fathers successfully teach their kids to eat with a spoon, use a potty, keep their fingers out of their noses, and say “please.” These things can be taught pleasantly, or they can be made into a painful chore. Being unpleasant (e.g. yelling, punishing, pressuring) doesn’t work, and it can be frustrating for everyone. This notion applies to teaching literacy, too. If you show your 18-month-old a book and she shows no interest, then put it away and come back to it later. If your child tries to write her name and ends up with a backwards “D,” no problem. No pressure. No hassle. You should enjoy the journey, and so should your child.

3. Talk to your kids (a lot).

Last year, I spent lots of time with our brand new granddaughter, Emily. I drowned her in language. Although “just a baby,” I talked — and sang — to her about everything. I talked about her eyes, nose, ears, mouth, and fingers. I told her all about her family — her mom, dad, and older brother. I talked to her about whatever she did (yawning, sleeping, eating, burping). I talked to her so much that her parents thought I was nuts; she couldn’t possibly understand me yet. But reading is a language activity, and if you want to learn language, you’d better hear it, and eventually, speak it. Too many moms and dads feel a bit dopey talking to a baby or young child, but studies have shown that exposing your child to a variety of words helps in her development of literacy skills.

I told her all about her family — her mom, dad, and older brother. I talked to her about whatever she did (yawning, sleeping, eating, burping). I talked to her so much that her parents thought I was nuts; she couldn’t possibly understand me yet. But reading is a language activity, and if you want to learn language, you’d better hear it, and eventually, speak it. Too many moms and dads feel a bit dopey talking to a baby or young child, but studies have shown that exposing your child to a variety of words helps in her development of literacy skills.

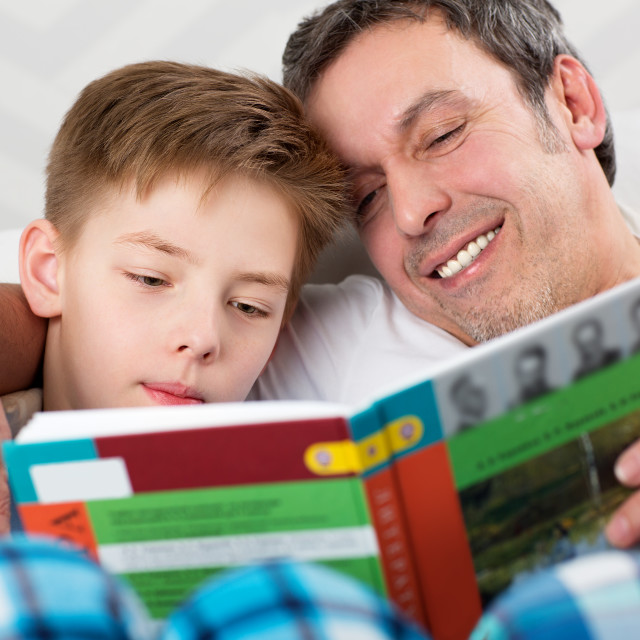

4. Read to your kids.

I know everyone says this, but it really is a good idea — at least with preschoolers. One of my colleagues refers to this advice as the “chicken soup” of reading education. We prescribe it for everything. (Does it help? It couldn’t hurt.) If a parent or caregiver can’t read or can’t read English, there are alternatives, such as using audiobooks; but for those who can, reading a book or story to a child is a great, easy way to advance literacy skills. Research shows benefits for kids as young as 9-months-old, and it could be effective even earlier than that. Reading to kids exposes them to richer vocabulary than they usually hear from the adults who speak to them, and can have positive impacts on their language, intelligence, and later literacy achievement. What should you read to them? There are so many wonderful children’s books. Visit your local library, and you can get an armful of adventure. You can find recommendations from kids at the Children’s Book Council website or at the International Literacy Association Children's Choices site. [Reading Rockets also provides guidance and lots of themed booklists in our Children's Books & Authors section.]

Research shows benefits for kids as young as 9-months-old, and it could be effective even earlier than that. Reading to kids exposes them to richer vocabulary than they usually hear from the adults who speak to them, and can have positive impacts on their language, intelligence, and later literacy achievement. What should you read to them? There are so many wonderful children’s books. Visit your local library, and you can get an armful of adventure. You can find recommendations from kids at the Children’s Book Council website or at the International Literacy Association Children's Choices site. [Reading Rockets also provides guidance and lots of themed booklists in our Children's Books & Authors section.]

5. Have them tell you a “story.”

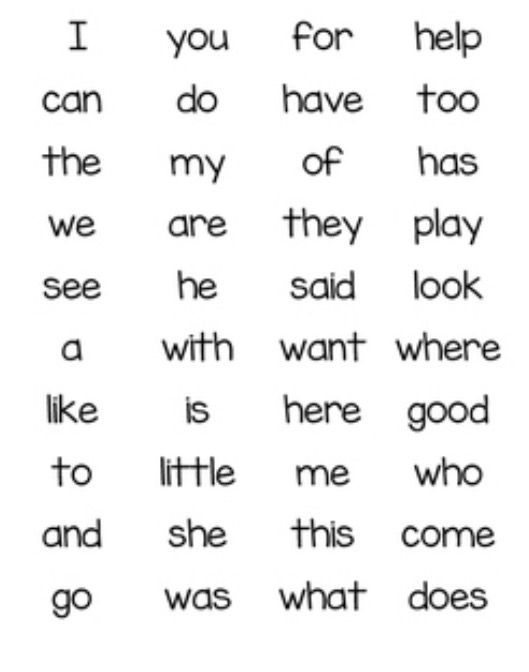

One great way to introduce kids to literacy is to take their dictation. Have them recount an experience or make up a story. We’re not talking “Moby Dick” here. A typical first story may be something like, “I like fish. I like my sister. I like grandpa.” Write it as it is being told, and then read it aloud. Point at the words when you read them, or point at them when your child is trying to read the story. Over time, with lots of rereading, don’t be surprised if your child starts to recognize words such as “I” or “like.” (As children learn some of the words, you can write them on cards and keep them in a “word bank” for your child, using them to review later.)

I like grandpa.” Write it as it is being told, and then read it aloud. Point at the words when you read them, or point at them when your child is trying to read the story. Over time, with lots of rereading, don’t be surprised if your child starts to recognize words such as “I” or “like.” (As children learn some of the words, you can write them on cards and keep them in a “word bank” for your child, using them to review later.)

6. Teach phonemic awareness.

Young children don’t hear the sounds within words. Thus, they hear “dog,” but not the “duh”-“aw”- “guh.” To become readers, they have to learn to hear these sounds (or phonemes). Play language games with your child. For instance, say a word, perhaps her name, and then change it by one phoneme: Jen-Pen, Jen-Hen, Jen-Men. Or, just break a word apart: chair… ch-ch-ch-air. Follow this link to learn more about language development milestones in children.

7. Teach phonics (letter names and their sounds).

You can’t sound out words or write them without knowing the letter sounds. Most kindergartens teach the letters, and parents can teach them, too. I just checked a toy store website and found 282 products based on letter names and another 88 on letter sounds, including ABC books, charts, cards, blocks, magnet letters, floor mats, puzzles, lampshades, bed sheets, and programs for tablets and computers. You don’t need all of that (a pencil and paper are sufficient), but there is lots of support out there for parents to help kids learn these skills. Keep the lessons brief and fun, no more than 5–10 minutes for young’uns. Understanding the different developmental stages of reading and writing skills will help to guide your lessons and expectations.

Most kindergartens teach the letters, and parents can teach them, too. I just checked a toy store website and found 282 products based on letter names and another 88 on letter sounds, including ABC books, charts, cards, blocks, magnet letters, floor mats, puzzles, lampshades, bed sheets, and programs for tablets and computers. You don’t need all of that (a pencil and paper are sufficient), but there is lots of support out there for parents to help kids learn these skills. Keep the lessons brief and fun, no more than 5–10 minutes for young’uns. Understanding the different developmental stages of reading and writing skills will help to guide your lessons and expectations.

8. Listen to your child read.

When your child starts bringing books home from school, have her read to you. If it doesn’t sound good (mistakes, choppy reading), have her read it again. Or read it to her, and then have her try to read it herself. Studies show that this kind of repeated oral reading makes students better readers, even when it is done at home.

9. Promote writing.

Literacy involves reading and writing. Having books and magazines available for your child is a good idea, but it’s also helpful to have pencils, crayons, markers, and paper. Encourage your child to write. One way to do this is to write notes or short letters to her. It won’t be long before she is trying to write back to you.

10. Ask questions.

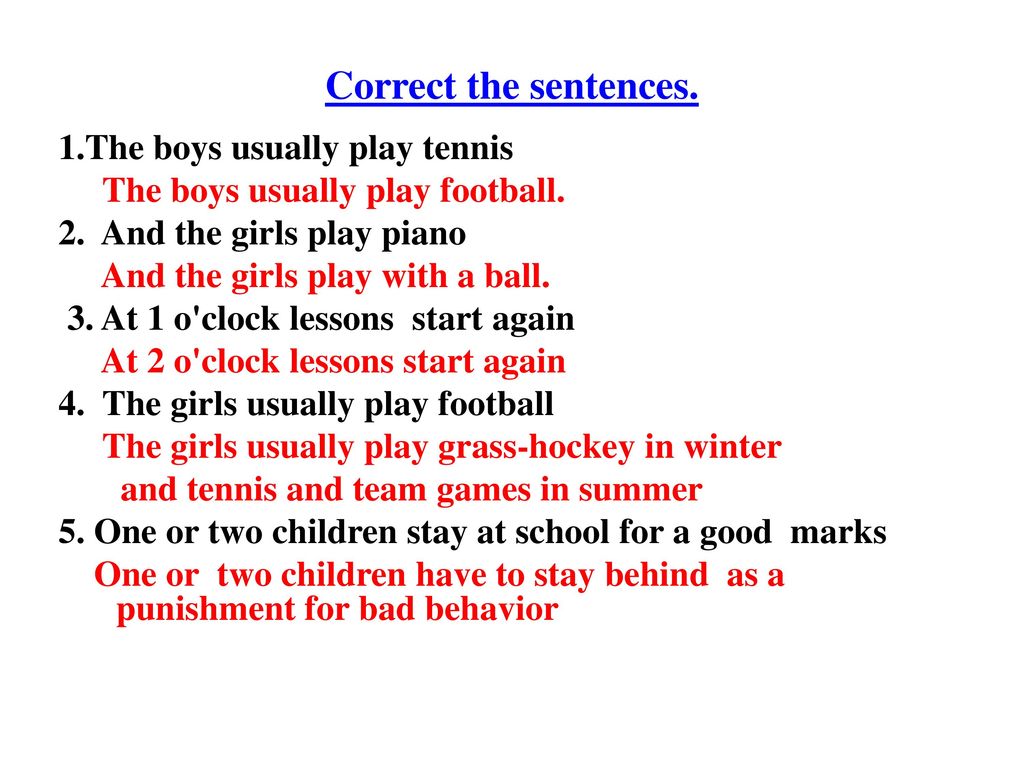

When your child reads, get her to retell the story or information. If it’s a story, ask who it was about and what happened. If it’s an informational text, have your child explain what it was about and how it worked, or what its parts were. Reading involves not just sounding out words, but thinking about and remembering ideas and events. Improving reading comprehension skills early will prepare her for subsequent success in more difficult texts.

11. Make reading a regular activity in your home.

Make reading a part of your daily life, and kids will learn to love it. When I was nine years old, my mom made me stay in for a half-hour after lunch to read. She took me to the library to get books to kick off this new part of my life. It made me a lifelong reader. Set aside some time when everyone turns off the TV and the web and does nothing but read. Make it fun, too. When my children finished reading a book that had been made into a film, we’d make popcorn and watch the movie together. The point is to make reading a regular enjoyable part of your family routine.

She took me to the library to get books to kick off this new part of my life. It made me a lifelong reader. Set aside some time when everyone turns off the TV and the web and does nothing but read. Make it fun, too. When my children finished reading a book that had been made into a film, we’d make popcorn and watch the movie together. The point is to make reading a regular enjoyable part of your family routine.

Happy reading!

Sources:

Ritchie, S.J., & Bates, T.C. (2013). Enduring links from childhood mathematics and reading achievement to adult socioeconomic status. Psychological Science, 24, 1301-1308.

Karass J., & Braungart-Rieker J. (2005). Effects of shared parent-infant reading on early language acquisition. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 133-148.

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

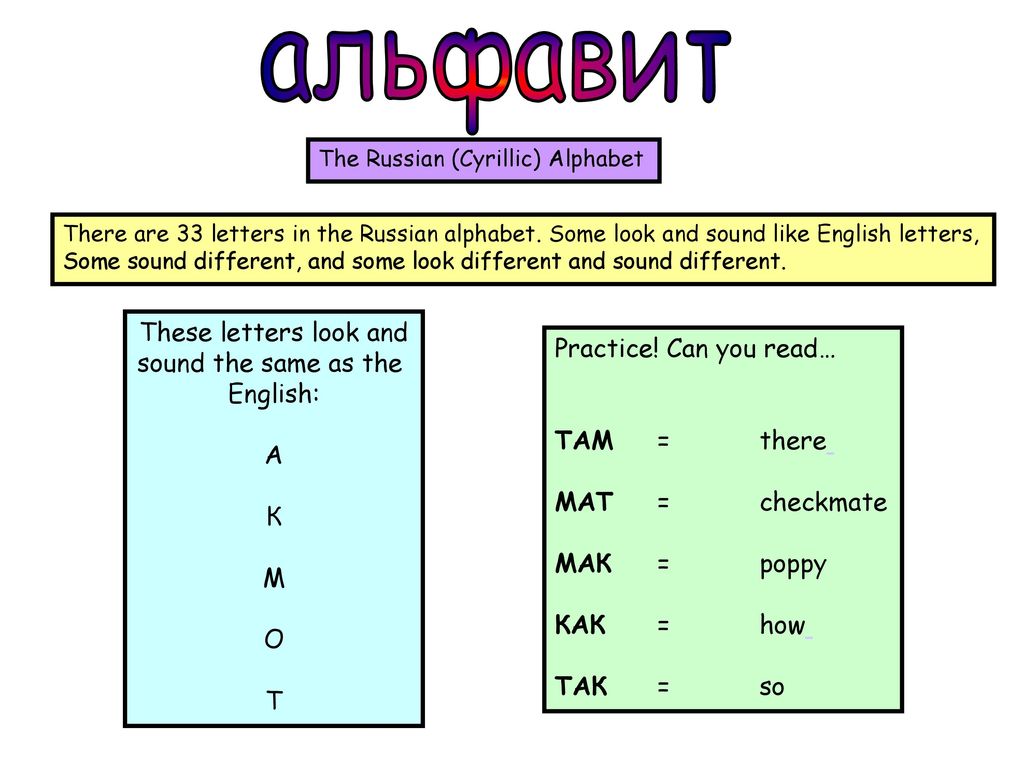

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

How to teach a child to understand and remember the read text?

You spend a lot of time helping your child learn to read. You try to be patient and not rush him. He reads and rereads the same paragraph, but he never “understands” it. Why is it so difficult for a child to understand what he reads?

It's great that you support your child's reading endeavors. Your disappointment is understandable, you have spent a lot of time and effort on teaching your child, but at the same time you do not see much improvement. Rest assured, you have already done a lot just by showing your child how much you care about him.

The ability to make sense of sentences and paragraphs involves a complex combination of many skills and abilities. In order to provide a child with the right support in reading, it is necessary to understand the nature of his difficulties.

In order to provide a child with the right support in reading, it is necessary to understand the nature of his difficulties.

The process of decoding and word recognition

The process of decoding is the transformation of a graphic model of a word into an oral language form. The ability to match the written and sound designation of a word is an important step in learning to read. Decoding is the foundation on which all learning to read is built.

If your child gets lost in the decoding process, they will have difficulty reading comprehension. To develop your decoding skills at home, take classes in the new Fast ForWord Foundations correctional online program. Decoding is a very important process - the more words a child can automatically recognize at a glance (without having to pronounce each letter or syllable), the faster he will be able to read.

Reading fluency

Why does fluent reading matter? If a child reads each word syllable by syllable, it takes him a long time to read the whole sentence. This makes it difficult to memorize all the words in a sentence and understand how they fit together.

This makes it difficult to memorize all the words in a sentence and understand how they fit together.

One way to learn to quickly recognize a word is to read it out loud several times. This is why reading the same passage repeatedly can help a child learn to read fluently.

Reading comprehension level

Even if your child is a good reader, they may be reading books that are well above their current level of comprehension. The most important thing is that the child can not only read the text, but also comprehend it. Sometimes teachers evaluate reading skills - how well a student can read and understand a text. These grades also reflect important information - whether the student needs help.

Talk to the teacher about your child's reading skills. You can ask the teacher to recommend books for home reading that are appropriate for your child's reading level. You can also choose books by yourself. For example, when choosing a book, ask your child to read a few pages and talk about what they just read. The book is suitable if the child really understands what they read.

The book is suitable if the child really understands what they read.

Attention Concentration

Difficulty concentrating is another reason your child may have reading comprehension problems. Reading comprehension also depends on the ability to ignore distractions.

If your child has difficulty concentrating, it may be due to an executive function disorder, an auditory processing disorder, or ADD/ADHD. These impairments can affect his ability to understand and retain information in working memory.

You can help your child to reduce the load, for example, teach him to break reading tasks into small parts, take notes, highlight important information.

Comprehension skills and strategies

Reading is thinking. And the way we think is the basis for improving comprehension while reading. To improve text comprehension, sometimes we need to consciously stop while reading and analyze our ideas and thoughts related to what we have read.

You can teach your child to be an active reader. Encourage him to voice all his thoughts and doubts, ask questions as he reads, read aloud one paragraph at a time and discuss what he read.

Point out to him that experienced readers also monitor how well they understand what they are reading and reread confusing parts of the text. Learn to look for contextual clues around a sentence or phrase, such as pictures or words in adjacent sentences, can help your child understand the meaning of words they don't understand. Help your child learn these strategies by example.

Additional support

Be sure to talk to your child's teacher about additional support at school.

Remember that your continued attention and encouragement will have a long-term positive impact on your child's education. Understanding your child's problems and applying the instructions above will help you improve your child's reading skills.

Do you want to quickly develop key reading skills: decoding, reading comprehension, extracting meaning from context, reading fluency, etc., as well as concentration, memory, information processing? Then you need classes according to the FAST FORWORD method!

Sign up for trial online classes in Fast ForWord right now.

Don't delay helping your child!

Source

SIGN UP

Useful article? Share with your friends!

7 tips on how to help your child fall in love with reading (voluntarily!)

For one child, a book is really the best gift, while another will cringe at the sight of another volume. They force you at school, now at home too. But you don’t need to force it, even a school reading list for the summer. How to really captivate a child with books - says a specialist in children's reading and writer Yulia Kuznetsova.

They force you at school, now at home too. But you don’t need to force it, even a school reading list for the summer. How to really captivate a child with books - says a specialist in children's reading and writer Yulia Kuznetsova.

1. Do not force your child to read

The desire to read is formed from within, so I am sure that forcing a child to read at five or six years old is a dangerous path. The word "should" should be applied to children's reading in general with caution and at a more serious age, from grade 5-6 and only in relation to school literature.

If a child does not feel like reading himself, there is nothing wrong with that. My middle son did not take reading aloud until he was three years old. While I was reading to my eldest daughter, he was crawling around on the sofa, pinching our hair - it only annoyed me. Then suddenly, at the age of four, he fell in love with reading aloud. At the age of five, we began to teach him to read, at first he did not particularly like to do this either. And by the age of six, reading began, this is a spontaneous process.

And by the age of six, reading began, this is a spontaneous process.

Parents are often afraid that their child will go to school without being able to read. It all depends on the teacher. Now I hear about cases when teachers say: “I don’t need parents to bring the child to some level, otherwise he will be simply bored in the lessons.”

2. Surrounding children with books is good advice, but it doesn't always work

My experience is quite different. When I came back from book festivals and brought bags of books to children, we had the following dialogue: "I brought you gifts" - "What gifts?" - "Books" - "I see, but did you bring normal gifts?"

When there are many books in the family, the following stories may come up. You ask: "Do you want to read a book?" - "Not". They closed the book and put it in the fridge. After a while, you ask again, you get the same answer, and you put the book on the windowsill. It turns out that these “I don’t want” lie all over the apartment.

It seems to me that we should remember our book experience, when in childhood there were always not enough books. Especially the ones you really wanted to read. I run courses for children where we do group calculations, we have our own library that fits on a chair. These are books from my home library that have gone through a rigorous selection: they will definitely appeal to children who do not like and do not want to read. Children come, sit down, see some books, they are interested in taking them and looking at them, but I don’t let them do it. They say, “Please, please, can I? If I don’t take it now, then Petya will take this book later.” I say: "No, now we have a lesson, we are doing other interesting things." And when they see that the books cannot be freely approached, then after the lesson they scatter in a second. A mob runs up, they take everything apart and take it home. Moreover, the children know that next time I will ask what this book was about.

3.

Talk with your children about the books you read yourself

Talk with your children about the books you read yourself Parents who read in front of their children are very rare. Use these moments to talk to him about the book you are reading right now, or even try reading out snippets. For example, my daughter once loved sheep very much, and I was reading Sheep Hunt by Haruki Murakami just at that time. When she found out about this, she said: “Sheep are being killed there, I feel sorry for them.” I offered to read a fragment of the book aloud to her so that she would see that no one was being killed there. I read the description of the pasture to her, and she was so delighted: her mother let her touch her book.

You can discuss books with other adults in front of children. I discuss books on the phone with my mother

We have similar tastes, my mother likes modern Russian women's prose, for example, Marina Stepanova. We call her and discuss some books, and the children hear it all.

4. Read aloud. And record reading on a voice recorder

Parents spend the whole day at work, and if after that they read aloud to their children for at least ten minutes, this becomes a powerful lock that holds relationships together. You can also not only read aloud, but also record reading on a voice recorder. The phone is not suitable for this, because it will switch attention to itself all the time. There is only one button on the voice recorder - turn it on and off.

You can also not only read aloud, but also record reading on a voice recorder. The phone is not suitable for this, because it will switch attention to itself all the time. There is only one button on the voice recorder - turn it on and off.

Dad sits down, reads aloud to them, all this is recorded on a dictaphone. One chapter in a children's book lasts an average of 10-15 minutes, this time is enough for the event called "evening reading" to take place. When dad leaves for a business trip, the children listen to the recordings. They turn it on when they eat, when they draw. This is not just a text, this is a memory of how good it was with dad in the evening.

5. Don't ignore audio books - they help with text

Audio books are a relief for children who are not very confident and see mostly letters, not images. They first get used to, and then return to a paper book. This mechanism also works with films (yes, yes). Children first watch the movie, find out how it all ends there, and then take the book and read it. It happens that children take the book even after performances. The host of the theater studio told how she staged "Uncle Vanya" with teenagers, and then a boy came to her and asked: "Is it possible to read this somewhere?" So a well-read audiobook, especially if you listen to it with your parents and discuss the plot, can also help instill a love of reading.

It happens that children take the book even after performances. The host of the theater studio told how she staged "Uncle Vanya" with teenagers, and then a boy came to her and asked: "Is it possible to read this somewhere?" So a well-read audiobook, especially if you listen to it with your parents and discuss the plot, can also help instill a love of reading.

6. Write a book about your child - this is another way to help him start reading

Take a picture or draw your child, stick it on a piece of paper and write: "This is Kolya." Then take a picture of how he eats and write: "Kolya eats." Then you can take a picture of how he sleeps, plays, and so on. Make such a book and show a child at the age of three - let him look at all this. When he is four years old, he will understand that letters can somehow be put together into words and will start trying to do it. Reading about yourself is always more interesting. My daughter is 12 years old, and she sits down with pleasure herself and reads a book about what she did nine years ago: she sculpted hedgehogs, kneaded the dough, molded cookies from it.

In my lessons I set aside 15 minutes and we write a book about ourselves. I give simple phrases that need to be completed: "Once I went ...", "And suddenly I saw ...", "Here I meet ...". It takes a little time, but it works very well. Children can write whole volumes about themselves.

In fact, for students who have difficulty in reading, it can be like writing classes - this is a good way to overcome reading difficulties. It seems that the child is learning to write, but at the same time learning to read. I had a girl on the course who stuttered and skipped words when reading. But when I read my text, I did not miss a single word. For her it was very important.

7. Do not be afraid that the child will not read the school list of literature for the summer

Take the list of literature, a pen and first of all cross out the books that the child definitely does not need. During communication with the teacher, you can understand what he wanted, including this or that book in the list. For example, in the first grade in our textbook there was a fragment from The Hobbit. The teacher decided that since there is a piece from Tolkien, then you need to read the whole book. I say, "Sorry, guys," and cross it out. We tried to watch a movie based on the book, but the children didn't get it: they were just scared.

For example, in the first grade in our textbook there was a fragment from The Hobbit. The teacher decided that since there is a piece from Tolkien, then you need to read the whole book. I say, "Sorry, guys," and cross it out. We tried to watch a movie based on the book, but the children didn't get it: they were just scared.

Then cross out all the books that the children know by heart. In the first grade, along with The Hobbit, we came across Little Red Riding Hood. I crossed out this book because we know it very well. Next, we select books that can be replaced with audiobooks and films. If the child is not drawn to reading Pinocchio, just show him the film. The plot will be postponed, and when the text from the book comes across to him in the textbook, the child will cope with it, because he will be six months or a year older.

Then choose the books you will read aloud. It was the same with Garin-Mikhailovsky's The Childhood of the Theme. My daughter got it in the second grade, and I realized that she would not pull it.

There remains a small sample of books that the child can read on his own. You take this list and say: “Look, here the teacher recommended these books. Which of these would be the most interesting for you to read?”. He chooses and you start reading. One summer, our son read one or two books, but at the very least, we replenished our cultural baggage. Often parents are afraid that they will come to school in September and they will be asked if the child has read the entire list. Just answer that you didn't read everything. There is nothing terrible in this.

What else to read about children's reading:

- Marina Aromshtam "Read!" - book that will give parents answers to many questions.

- Yulia Kuznetsova Calculation. How to help your child love reading ”- book about how parents can help children love books.

- Aidan Chambers “Tell me. We read, think, discuss” - the author tells how to communicate with children through books.

Learn more