How can read

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

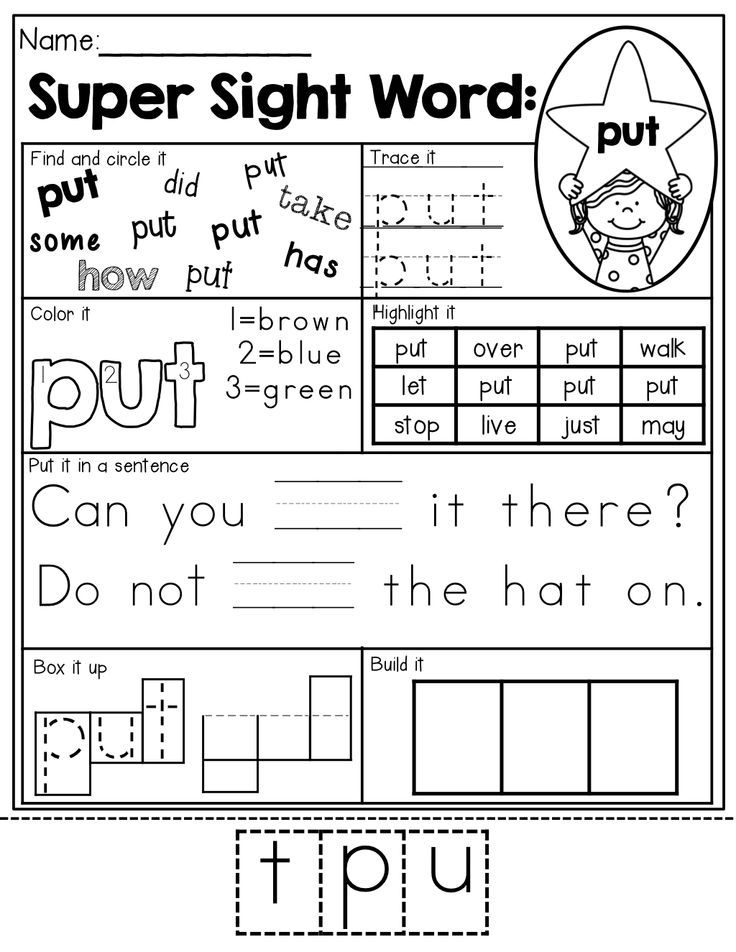

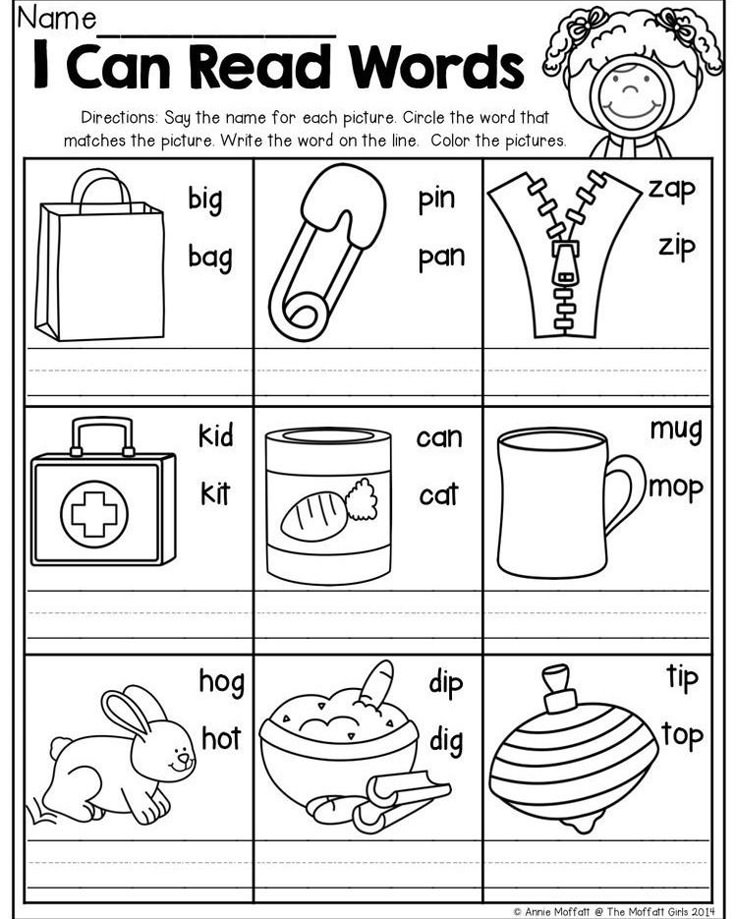

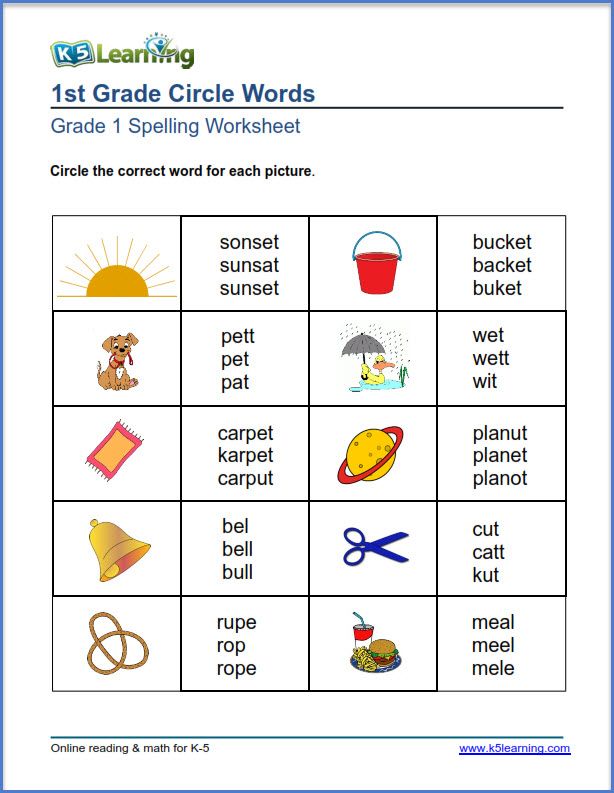

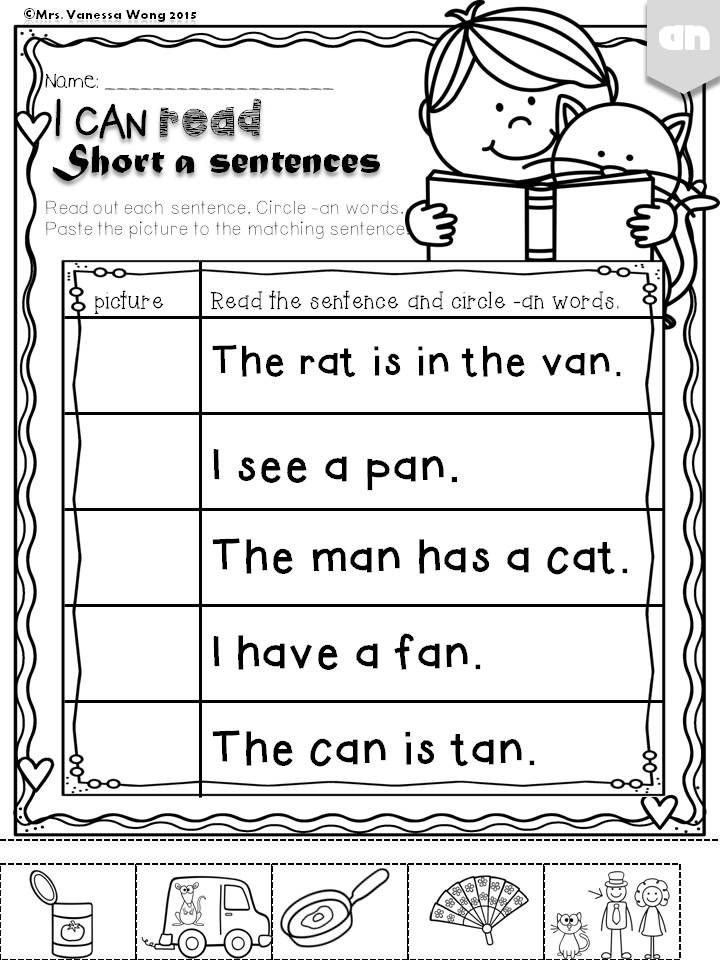

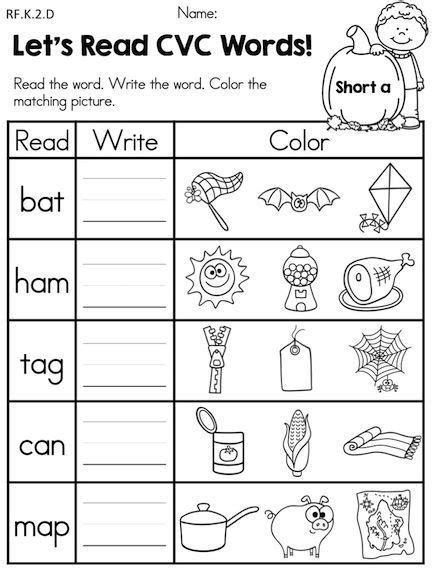

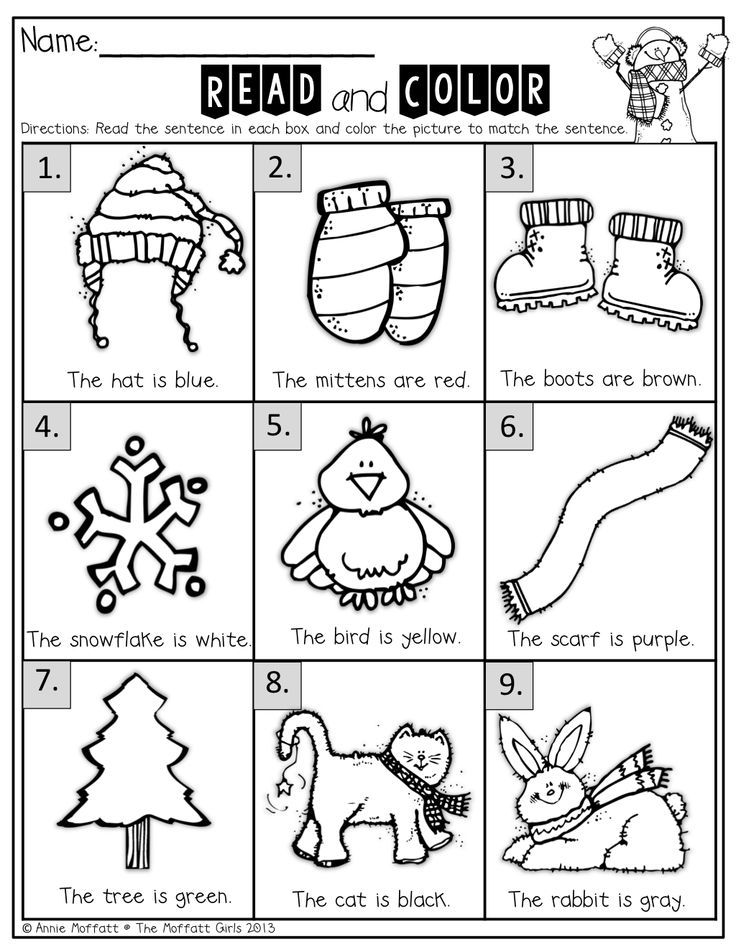

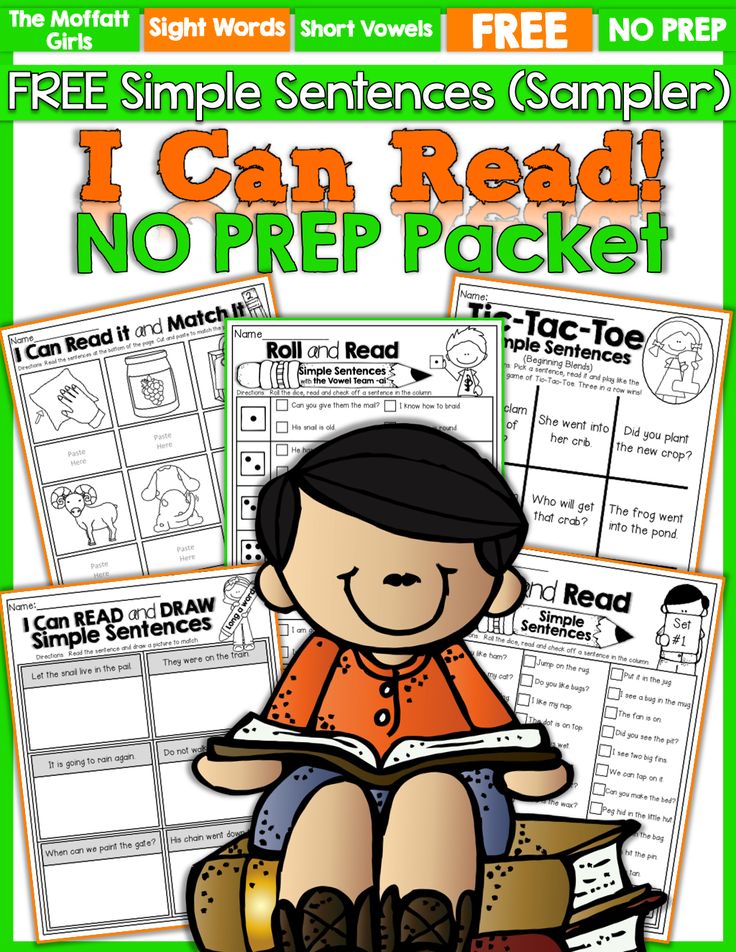

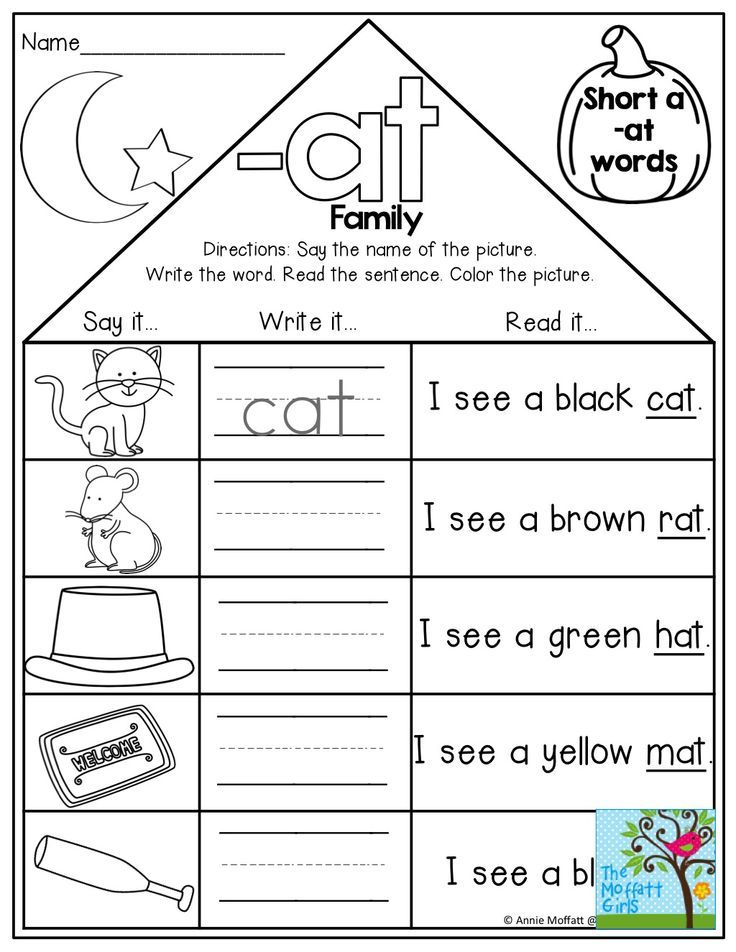

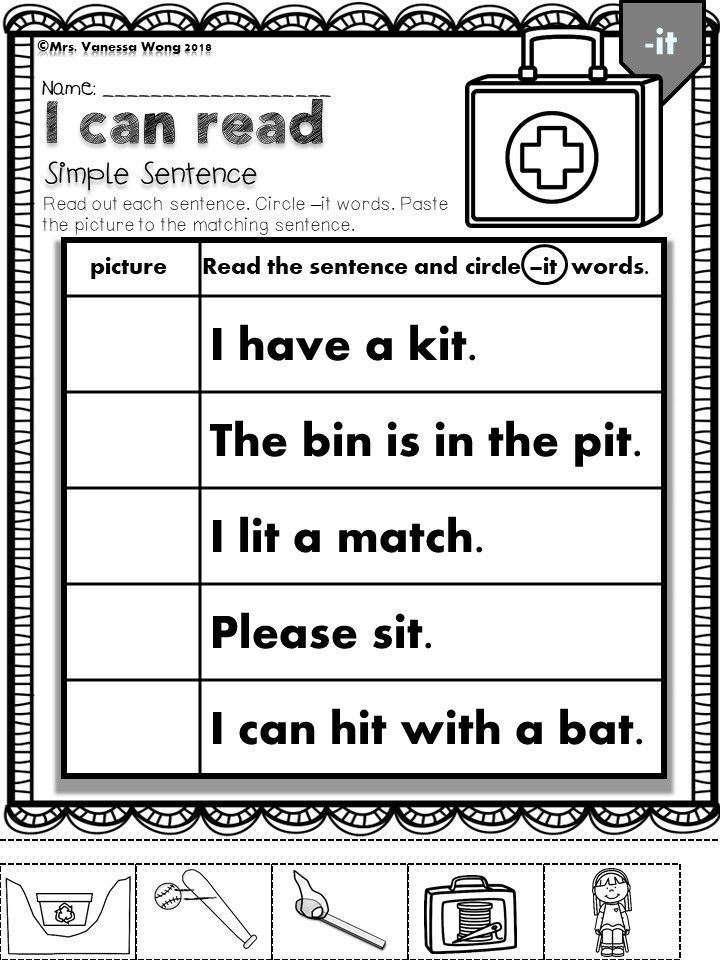

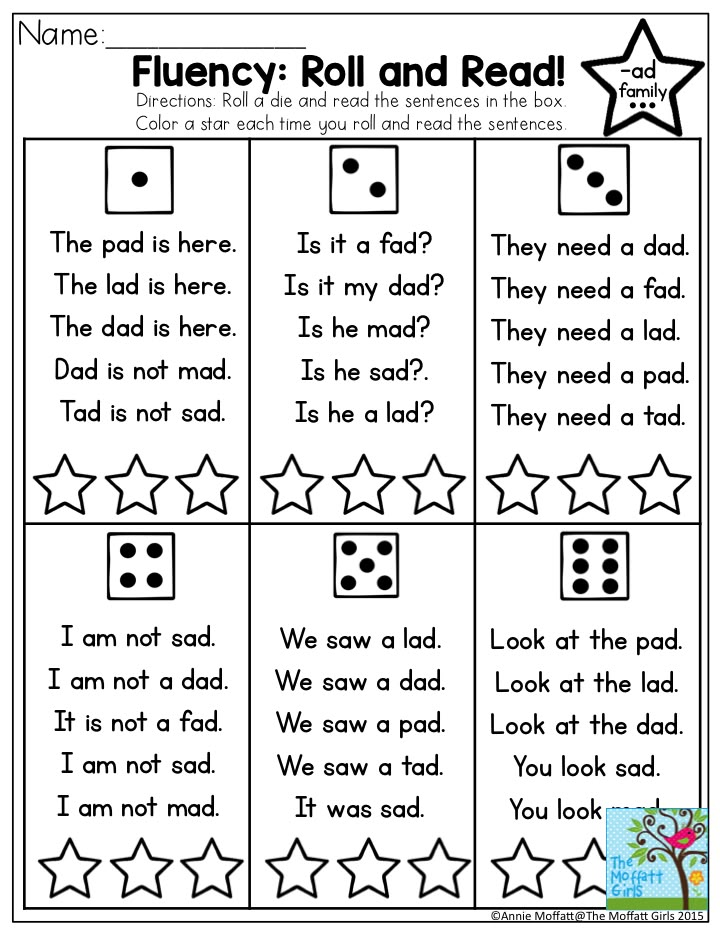

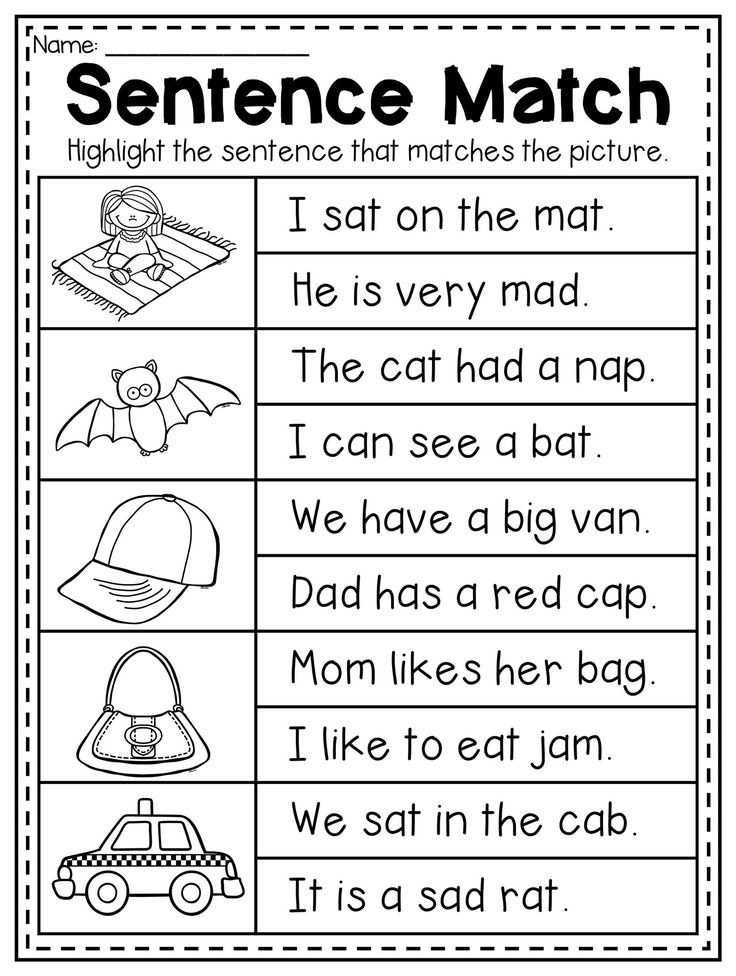

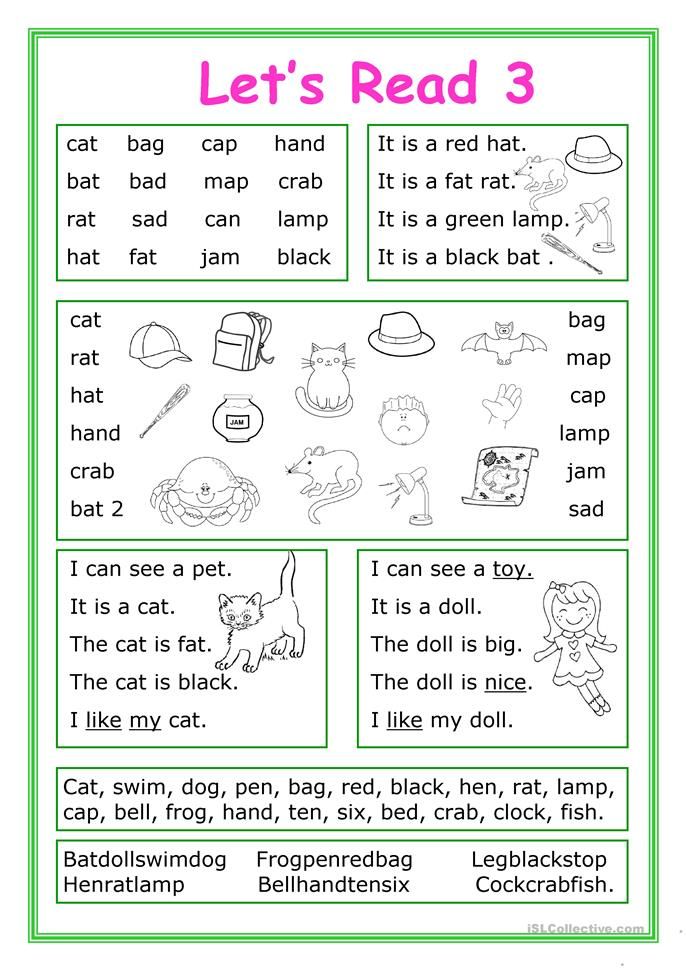

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

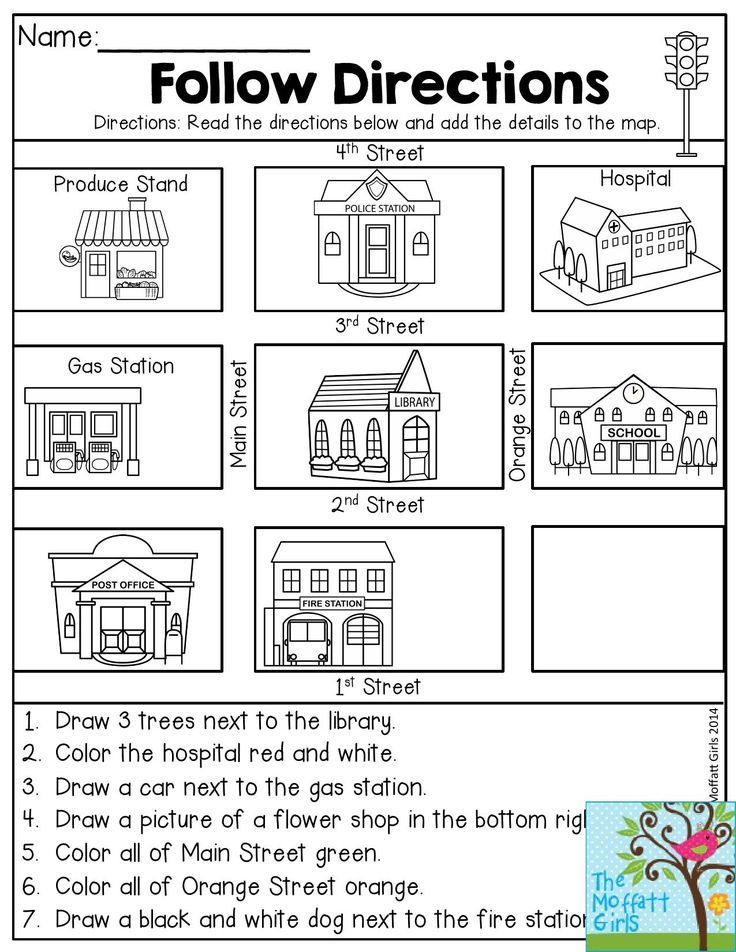

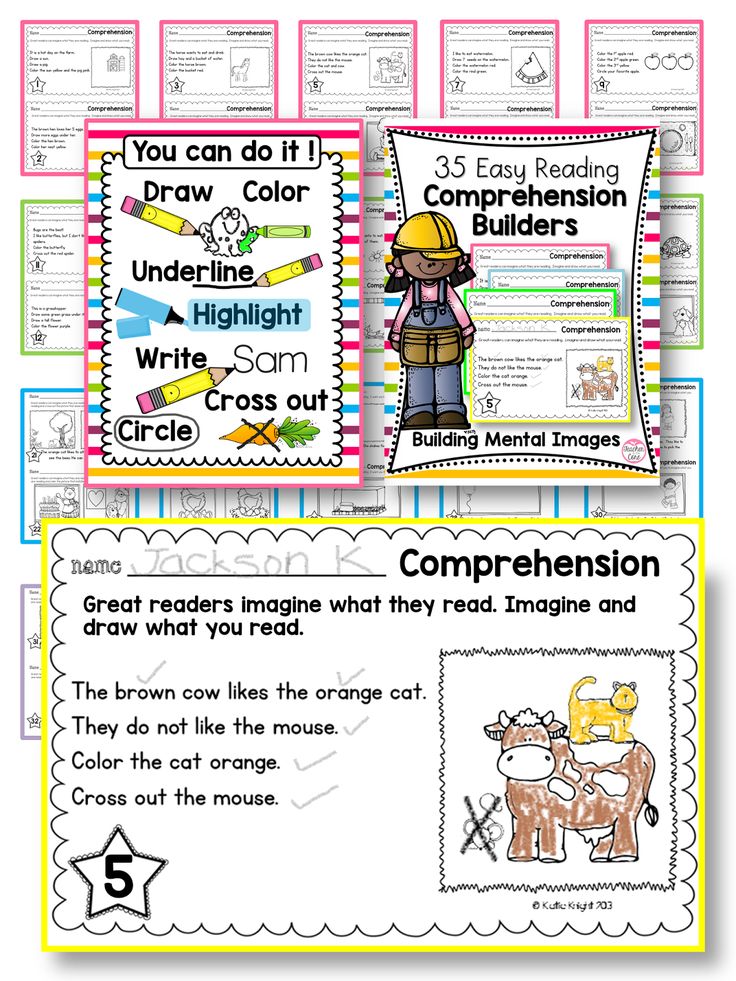

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

The Best Way to Read More Books (and Remember What You've Read)

“I just sit in my office and read all day.”

This is how Warren Buffett, one of the most successful people in the business world, describes his day. Sitting. Reading.

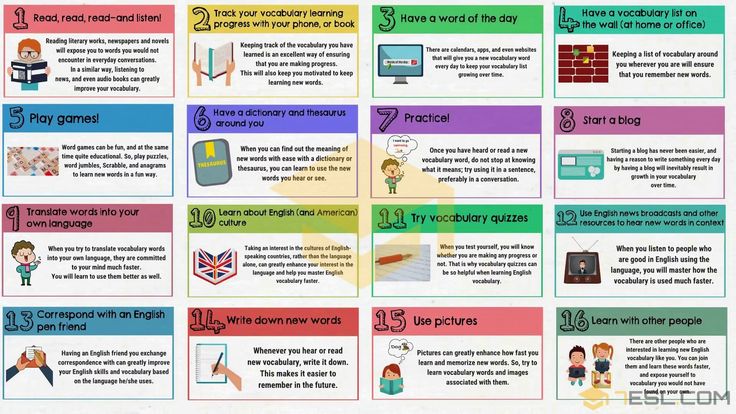

He advises everyone to read more, and that’s certainly a goal we can all get behind. Our personal improvements at Buffer regularly come back to the books we read—how we aim to read more and make reading a habit. I imagine you’re in the same boat as well. Reading more is one of our most common ambitions.

So how do we do it? And what are we to do with all that information once we have it?

Reading more and remembering it all is a discussion with a lot of different layers and a lot of interesting possibilities. I’m happy to lay out a few possibilities here on how to read more and remember it all, and I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

I’m happy to lay out a few possibilities here on how to read more and remember it all, and I’d love to hear your thoughts below.

But first, let’s set some baselines …

How fast do you read?

One of the obvious shortcuts to reading more is to read faster. That’s likely the first place a lot of us would look for a quick win in our reading routine.

So how fast do you read?

Staples (yes, the office supply chain) collected speed reading data as part of an advertising campaign for selling e-readers. The campaign also included a speed reading tool that is still available to try. Go ahead and take the test to see how fast you read.

(My score was 337 words per minute. Yours?)

The Staples speed reading test includes data on how other demographics stack up in words per minute. According to Staples, the average adult reads 300 words per minute.

- Third-grade students = 150 words per minute

- Eight grade students = 250

- Average college student = 450

- Average “high level exec” = 575

- Average college professor = 675

- Speed readers = 1,500

- World speed reading champion = 4,700

Is reading faster always the right solution to the goal of reading more? Not always. Comprehension still matters, and some reports say that speed reading or skimming leads to forgotten details and poor retention. Still, if you can bump up your words per minute marginally while still maintaining your reading comprehension, it can certainly pay dividends in your quest to read more.

Comprehension still matters, and some reports say that speed reading or skimming leads to forgotten details and poor retention. Still, if you can bump up your words per minute marginally while still maintaining your reading comprehension, it can certainly pay dividends in your quest to read more.

There’s another way to look at the question of “reading more,” too.

How much do you read?

There’s reading fast, and then there’s reading lots. A combination of the two is going to be the best way to supercharge your reading routine, but each is valuable on its own. In fact, for many people, it’s not about the time trial of going beginning-to-end with a book or a story but rather more about the story itself. Speed reading doesn’t really help when you’re reading for pleasure.

In this sense, a desire to read more might simply mean having more time to read, and reading more content—books, magazines, articles, blog posts—in whole.

Let’s start off with a reading baseline. How many books do you read a year?

How many books do you read a year?

A 2012 study by the Pew Research Center found that adults read an average of 17 books each year.

The key word here is “average.” There are huge extremes at either end, both those who read way more than 17 books per year and those who read way less—like zero. The same Pew Research study found 19 percent of Americans don’t read any books. A Huffington Post/YouGov poll from 2013 showed that number might be even higher: 28 percent of Americans haven’t read a book in the past year.

Wanting to read more puts you in pretty elite company.

5 ways to read more books, blogs, and articles

1. Read for speed: Tim Ferriss’ guide to reading 300% faster

Tim Ferriss, author of the 4-Hour Workweek and a handful of other bestsellers, is one of the leading voices in lifehacks, experiments, and getting things done. So it’s no wonder that he has a speed-reading method to boost your reading speed threefold.

His plan contains two techniques:

- Using a pen as a tracker and pacer, like how some people move their finger back and forth across a line as they read

- Begin reading each new line at least three words in from the first word of the line and end at least three words in from the last word

The first technique, the tracker/pacer, is mostly a tool to use for mastering the second technique. Ferriss calls this second technique Perceptual Expansion. With practice, you train your peripheral vision to be more effective by picking up the words that you don’t track directly with your eye. According to Ferriss:

Untrained readers use up to ½ of their peripheral field on margins by moving from 1st word to last, spending 25-50% of their time “reading” margins with no content.

The below image from eyetracking.me shows how this concept of perceptual expansion might look in terms of reading:

You’ll find similar ideas in a lot of speed reading tips and classes (some going so far as to suggest you read line by line in a snake fashion). Rapid eye movements called saccades occur constantly as we read and as our eyes jump from margins to words. Minimizing these is a key way to boost your reading times.

Rapid eye movements called saccades occur constantly as we read and as our eyes jump from margins to words. Minimizing these is a key way to boost your reading times.

The takeaway here: If you can advance your peripheral vision, you may be able to read faster—maybe not 300 percent faster, but every little bit counts.

2. Try a brand new way of reading

Is there still room for innovation in reading? A couple of new reading tools say yes.

Spritz and Blinkist take unique approaches to helping you read more—one helps you read faster and the other helps you digest books quicker.

First, Spritz. As mentioned above in the speed reading section, there is a lot of wasted movement when reading side-to-side and top-to-bottom.

Spritz cuts all the movement out entirely.

Spritz shows one word of an article or book at a time inside a box. Each word is centered in the box according to the Optimal Recognition Point—Spritz’s term for the place in a word that the eye naturally seeks—and this center letter is colored red.

Spritz has yet to launch anything related to its technology, but there is a bookmarklet called OpenSpritz, created by gun.io, that lets you use the Spritz reading method on any text you find online.

Here is what OpenSpritz looks like at 600 words per minute:

The Spritz website has a demo on the homepage that you can try for yourself and speed up or slow down the speeds as you need.

Along with Spritz is the new app Blinkist. Rather than a reimagining of the way we read, Blinkist is a reimagining of the way we consume books. Based on the belief that the wisdom of books should be more accessible to us all, Blinkist takes popular works of non-fiction and breaks the chapters down into bite-sized parts.

These so-called “blinks” contain key insights from the books, and they are meant to be read in two minutes or less. Yes, it’s a lot like Cliff Notes. Though the way the information is delivered—designed to look great and be eminently usable on mobile devices so you can learn wherever you are—makes it one-of-a-kind.

Here is an example of the Blinkist table of contents from Ben Horowitz’s The Hard Thing About Hard Things:

I’m sure we can agree that it’s a lot easier to read more when a book is distlled into 10 chapters, two minutes each.

3. Read more by making the time

Shane Parrish of the Farnam Street blog read 14 books in March, and he tackles huge totals like this month-in and month-out. How does he do it?

He makes it a priority, and he cuts out time from other activities.

What gets in the way of reading?I don’t spend a lot of time watching TV. (The lone exception to this is during football season where I watch one game a week.)

I watch very few movies.

I don’t spend a lot of time commuting.

I don’t spend a lot of time shopping.

If you look at it in terms of raw numbers, the average person watches 35 hours of TV each week, the average commute time is one hour per day round-trip, and you can spend at least another hour per week for grocery shopping.

All in all, that’s a total of 43 hours per week, and at least some of that could be spent reading books.

4. Buy an e-reader

In the same Pew research study that showed Americans’ reading habits, Pew also noted that the average reader of e-books reads 24 books in a year, compared to a person without an e-reader who reads an average of 15.

Could you really read nine more books a year just by purchasing an e-reader?

Certainly the technology is intended to be easy-to-use, portable, and convenient. Those factors alone could make it easier to spend more time reading when you have a spare minute. Those spare minutes might not add up to nine books a year, but it’ll still be time well spent.

5. Read more by not reading at all

This is quite counterintuitive advice, and it comes from a rather counterintuitive book.

How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, written by University of Paris literature professor Pierre Bayard, suggests that we view the act of reading on a spectrum and that we consider more categories for books besides simply “have or haven’t read. ” Specifically, Bayard suggests the following:

” Specifically, Bayard suggests the following:

- books we’ve read

- books we’ve skimmed

- books we’ve heard about

- books we’ve forgotten

- books we’ve never opened.

He even has his own classification system for keeping track of how he’s interacted with a book in the past.

UB book unknown to meSB book I have skimmed

HB book I have heard about

FB book I have forgotten

++ extremely positive opinion

+ positive opinion

– negative opinion

– extremely negative opinion

Perhaps the key to reading more books is simply to look at the act of reading from a different perspective? In Bayard’s system, he essentially is counting books he’s skimmed, heard about, or forgotten as books that he’s read. How might these new definitions alter your reading total for the year?

3 ways to remember what you read

1. Train your brain with impression, association, and repetition

Train your brain with impression, association, and repetition

A great place to start with book retention is with understanding some key ways our brain stores information. Here are three specific elements to consider:

- Impression

- Association

- Repetition

Let’s say you read Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, one of our favorites here at Buffer. You loved the information and want to remember as much as possible. Here’s how:

Impression – Be impressed with the text. Stop and picture a scene in your mind, even adding elements like greatness, shock, or a cameo from yourself to make the impression stronger. If Dale Carnegie is explaining his distaste for criticism, picture yourself receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace and then spiking the Nobel Prize onto the dais.

(Another trick with impression is to read an important passage out loud. For some of us, our sensitivity to information can be greater with sounds rather than visuals. )

)

Association – Link the text to something you already know. This technique is used to great effect with memorization and the construction of memory palaces. In the case of Carnegie’s book, if there is a particular principle you wish to retain, think back to a time when you were part of a specific example involving the principle. Prior knowledge is a great way to build association.

Repetition – The more you repeat, the more you remember. This can occur by literally re-reading a certain passage or in highlighting it or writing it down then returning to it again later.

Practicing these three elements of remembering will help you get better and better. The more you work at it, the more you’ll remember.

2. Focus on the four levels of reading

Mortimer Adler’s book, How to Read a Book, identifies four levels of reading:

- Elementary

- Inspectional

- Analytical

- Syntopical

Each step builds upon the previous step. Elementary reading is what you are taught in school. Inspectional reading can take two forms: 1) a quick, leisurely read or 2) skimming the book’s preface, table of contents, index, and inside jacket.

Elementary reading is what you are taught in school. Inspectional reading can take two forms: 1) a quick, leisurely read or 2) skimming the book’s preface, table of contents, index, and inside jacket.

Where the real work (and the real retention begins) is with analytical reading and syntopical reading.

With analytical reading, you read a book thoroughly. More so than that even, you read a book according to four rules, which should help you with the context and understanding of the book.

- Classify the book according to subject matter.

- State what the whole book is about. Be as brief as possible.

- List the major parts in order and relation. Outline these parts as you have outlined the whole.

- Define the problem or problems the author is trying to solve.

The final level of reading is syntopical, which requires that you read books on the same subject and challenge yourself to compare and contrast as you go.

As you advance through these levels, you will find yourself incorporating the brain techniques of impression, association, and repetition along the way. Getting into detail with a book (as in the analytical and syntopical level) will help cement impressions of the book in your mind, develop associations to other books you’ve read and ideas you’ve learned, and enforce repetition in the thoughtful, studied nature of the different reading levels.

Getting into detail with a book (as in the analytical and syntopical level) will help cement impressions of the book in your mind, develop associations to other books you’ve read and ideas you’ve learned, and enforce repetition in the thoughtful, studied nature of the different reading levels.

3. Keep the book close (or at least your notes on the book)

One of the most common threads in my research into remembering more of the books you read is this: Take good notes.

Scribble in the margins as you go.

Bookmark your favorite passages.

Write a review when you’ve finished.

Use your Kindle Highlights extensively.

And when you’ve done these things, return to your notes periodically to review and refresh.

Shane Parrish of Farnam Street is a serial note taker

, and he finds himself constantly returning to the books he reads.

After I finish a book, I let it age for a week or two and then pick it up again.I look at my notes and the sections I’ve marked as important. I write them down. Or let it age for another week or two.

Even Professor Pierre Bayard, the author of How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, identifies the importance of note-taking and review:

Once forgetfulness has set in, he can use these notes to rediscover his opinion of the author and his work at the time of his original reading. We can assume that another function of the notes is to assure him that he has indeed read the works in which they were inscribed, like blazes on a trail that are intended to show the way during future periods of amnesia.

I’ve tried this method for myself, and it has completely changed the way I perceive the books I read. I look at books as investments in a future of learning rather than a fleeting moment of insight, soon to be forgotten. I store all the reviews and notes from my books on my personal blog so I can search through them when I need to remember something I’ve read.

(Kindle has a rather helpful feature online, too, where it shows you a daily, random highlight from your archive of highlights. It’s a great way to relive what you’ve read in the past.)

It’s not important which method you have for note-taking and review so long as you have one. Let it be as simple as possible to complete so that you can make sure you follow through.

Over to you

How many books do you read each year? What will be your goal for this year? What’s your best tip for reading more and remembering more? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

P.S. If you liked this post, you might also like The Two Brain Systems that Control Our Attention: The Science of Gaining Focus and 5 Unconventional Ways to Become a Better Writer (Hint: It’s About Being a Better Reader).

Image credits: Patrick Gage via Compfight, eyetracking.me, OpenSpritz,

How to read correctly. 7 important tips

A+ A A-

- Category: Tips for parents

- Views: 103510

How to read correctly.

7 Important Tips

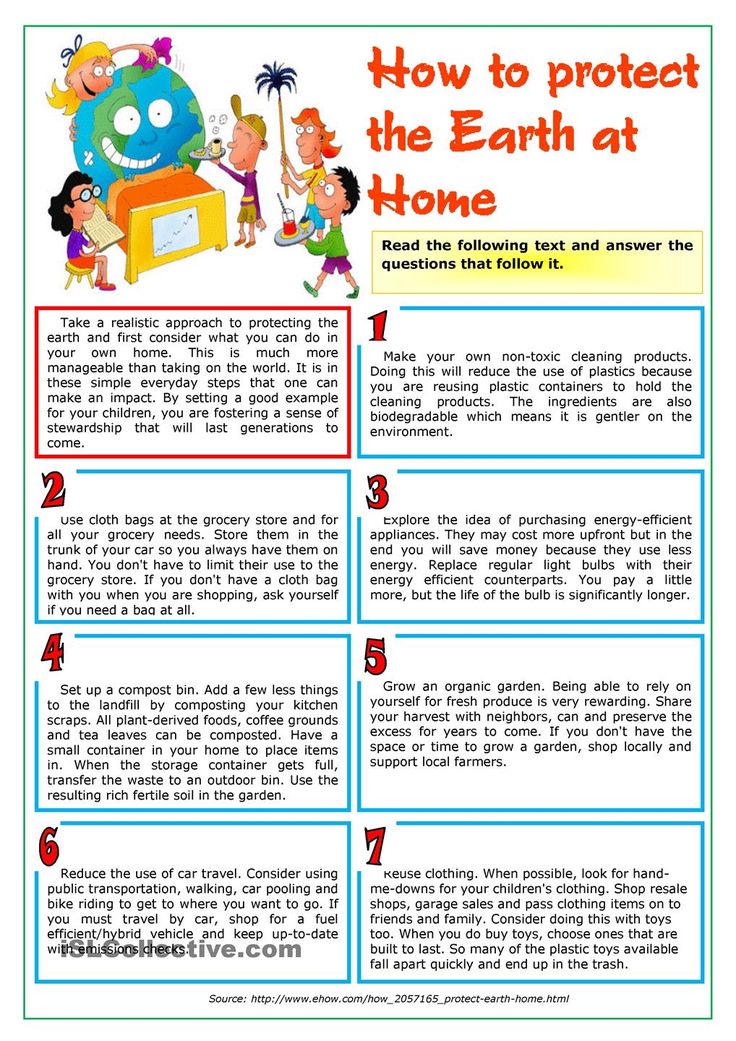

7 Important Tips So here are some tips on how to read correctly. It's not just about reading technique. Correct in this case - this is with the maximum benefit from what you read. Naturally, first of all, these tips relate to reading non-fiction literature - books on self-development, on the profession, educational and scientific literature, etc. That is, those from the reading of which some very specific benefit is expected: knowledge, skills, competencies. However, these "rules" can be successfully applied to fiction as well. After all, fiction, especially classical literature, is designed not so much to entertain the reader as to give him some new experience. Here is how to get this experience as much as possible and our advice will help.

1. Read regularly

Make it a rule to dedicate at least an hour a day to reading and do not deviate from this rule for anything. If it is impossible to carve out such a whole period of time in your daily routine, break this time into two 30-minute segments, or even three 20-minute ones. Taking time to read before bed is not a good idea from a productivity standpoint. During the day, your brain gets tired and saturated with information, it will be difficult for it, especially if you read non-fiction.

Taking time to read before bed is not a good idea from a productivity standpoint. During the day, your brain gets tired and saturated with information, it will be difficult for it, especially if you read non-fiction.

2. Read with a notepad at hand

The ability to write down the necessary thoughts from the book, or your thoughts that arise in the course of reading, significantly increase the effectiveness of reading. Using these notes, you can then easily restore the key points of the book in memory, you can use them when the book is not at hand. Even just writing out quotes from a fiction book is of great benefit. Some advise even to compose the "skeleton" or "summary" of the book in this way, but these are already details.

3. Read thoughtfully

" Read correctly " does not mean "read fast", rather the opposite. Never chase reading speed. The usefulness of books "is not determined by the amount of reading, but by the amount of understanding. " It is better to re-read a difficult or controversial passage than to skip without understanding anything. Do not be lazy to find out the meanings of unfamiliar words and terms (fortunately, now it is very simple). Pay attention to context. If the author refers to a theory or study unfamiliar to you, find out at least in general terms what the essence of the theory or study is. By the way, this will help you with the next step.

" It is better to re-read a difficult or controversial passage than to skip without understanding anything. Do not be lazy to find out the meanings of unfamiliar words and terms (fortunately, now it is very simple). Pay attention to context. If the author refers to a theory or study unfamiliar to you, find out at least in general terms what the essence of the theory or study is. By the way, this will help you with the next step.

4. Constantly look for books

It would seem that what to look for - there are so many of them. But most of these books are of no use to you, they are just rubbish. In order not to fill your head with garbage, you need to responsibly approach the choice of literature for reading. Make sure you have a "to read" list. Follow the latest in the area you are interested in, read the reviews of other people. Determine the next book in advance. In a word, plan your reading process.

5. Read different books

Sometimes it is very useful to read several books on the same topic in a row, compare them with each other, look at the problem from different angles. But you shouldn't get hung up on the same thing. Read science fiction after self-development books, Russian classics after business literature, etc. Some even advise doing it at the same time - reading one book "for good", and another, fiction, for pleasure.

But you shouldn't get hung up on the same thing. Read science fiction after self-development books, Russian classics after business literature, etc. Some even advise doing it at the same time - reading one book "for good", and another, fiction, for pleasure.

6. Switch to e-books

Paper books are wonderful and I do not call for them to be abandoned. But the reality is that reading e-books from a tablet, and even more so from a book reader, is much more convenient. The e-book market is developing and more and more new publications are available in electronic format. If you really want to read a lot and profitably, then e-books are an almost inevitable choice.

7. Draw conclusions about what you read

After you have turned the last page, it would be good to formulate your thoughts about what you read - to draw some conclusions for yourself. What do you understand, what do you agree/disagree with, what can be used. Even after reading a fiction book, it can be helpful to structure your thoughts. If you followed the second point, then it will be quite simple to do this. It is a good practice to write reviews and reviews of what you have read.

If you followed the second point, then it will be quite simple to do this. It is a good practice to write reviews and reviews of what you have read.

Well, the most important advice on how to read correctly: " Put what you read into practice! "Otherwise, everything is in vain.

http://bookmix.ru/blogs/note.phtml?id=13178

- Back

- Forward

How to read books correctly - Lifehacker

June 15, 2014 Books

Reading books is already good. But it's even better if you do it right.

janeimanbaeva

Some books are easy enough to try, others you want to swallow in one fell swoop, and there are those that take a long time to chew and digest.

Francis Bacon

In 1940, the American philosopher Mortimer Adler wrote How to Read Books. A Guide to Reading Great Works, which is now considered a classic. Let's take a look at the important points from his work.

What do you need to know to read books correctly?

There are four ways of reading:

- Elementary. This is taught in elementary school. You read the words, understand their meaning and follow the main plot.

- Inspection. This is vertical reading. You look at the beginning of the page, then you go to the end and at the same time try to catch the key points. This method is suitable for those who need to master large educational or work materials.

- Analytical. You read slowly and carefully, take notes, look up words you don't understand, follow the links provided by the author.

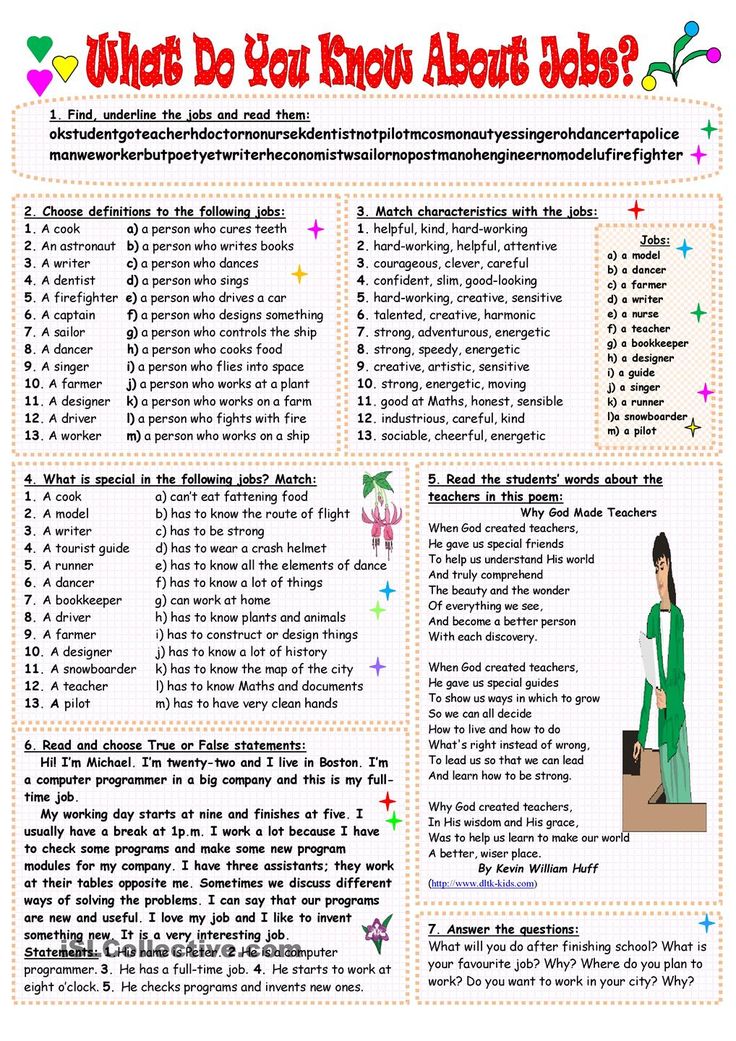

- Research. This is how writers, scientific and creative workers read. You study several books on the same topic at the same time to confirm or disprove your theory.

Let's focus on the second and third types of reading, because elementary reading has long been familiar to you, and few will be interested in research reading. With analytical and inspection reading, it is different: many people need it, but not all people know it.

With analytical and inspection reading, it is different: many people need it, but not all people know it.

Inspection reading

It is suitable in several situations. For example, you need to quickly evaluate a book in a store, understand the essence of a report, and find out the latest news in your field. What you need is not a deep dive into the text, but a quick capture and evaluation of information. How to learn it?

Read the title and study the cover of the book

The author always attaches great importance to the title and design, putting the main meaning of the whole book into them. If you manage to guess this message, much will become clear even before the first lines of the text.

Pay attention to the first pages

The table of contents, preface, prologue are useful pages that will give an idea of the whole book, even if you have a multi-page scientific work in front of you.

Review chapter titles and conclusion

This is especially true for business and popular science literature. Here you can immediately go to the end to find out the main conclusions, and only then read the proof.

Here you can immediately go to the end to find out the main conclusions, and only then read the proof.

Read reviews

Find book sites that post reviews from real people.

These skills will help you choose the right book in 5-10 minutes and save time.

Analytical reading

If you can't read in this way, no book can give you what the author puts in it. Use analytical reading when you want to get the most out of reading. Let's see how to get the most out of what we read.

Learn more about the author and his other works

This will clarify the motives and features of his work. A book about financial success will be more credible if written by a practicing entrepreneur rather than a broke loser. A novel about the war will be read differently if the author himself went through it.

Spend a few minutes reading

Before diving into the text, pay attention to the title, cover, first pages, table of contents, and conclusion.

Go back to difficult points

If you come across a difficult or incomprehensible passage, don't stop there, just make a note and keep reading. When you finish the book, go back to your bookmarks and pay attention to all the controversial and incomprehensible points. Attract additional sources, reread complex paragraphs. You should not have dark places in the studied material.

Prepare a short summary

Write a short report after reading the book. Tell us about your impressions and new knowledge. Ideally, if you do it in writing.

- What is this book about? Sometimes we are so immersed in the plot that by the end we forget about the main idea of the author. Describe in a few sentences the main meaning of the work.

- What happened and why? Make a short outline of the book. For fiction, these may be the key events of the plot, for popular science - the main theses and evidence.

- Are the events, facts and opinions described in the book interesting and true? How do you feel about the book? Do you agree with the author's opinion?

- What conclusions did you draw? Tell us what you learned from the book for yourself.

Learn more