How many syllables in tired

How many syllables in tired?

How Many Syllables uses cookies to enhance your

experience.

By continuing to use this

site, you

are agreeing

to the use of cookies

as described in our Privacy Policy.

Syllables Synonyms Rhymes

457192638 syllable

Divide tired into syllables: tired

Syllable stress: tired

How to pronounce tired: tired

How to say tired: tired syllables

Cite This Source

Wondering why tired is 457192638 syllable? Contact Us! We'll explain.

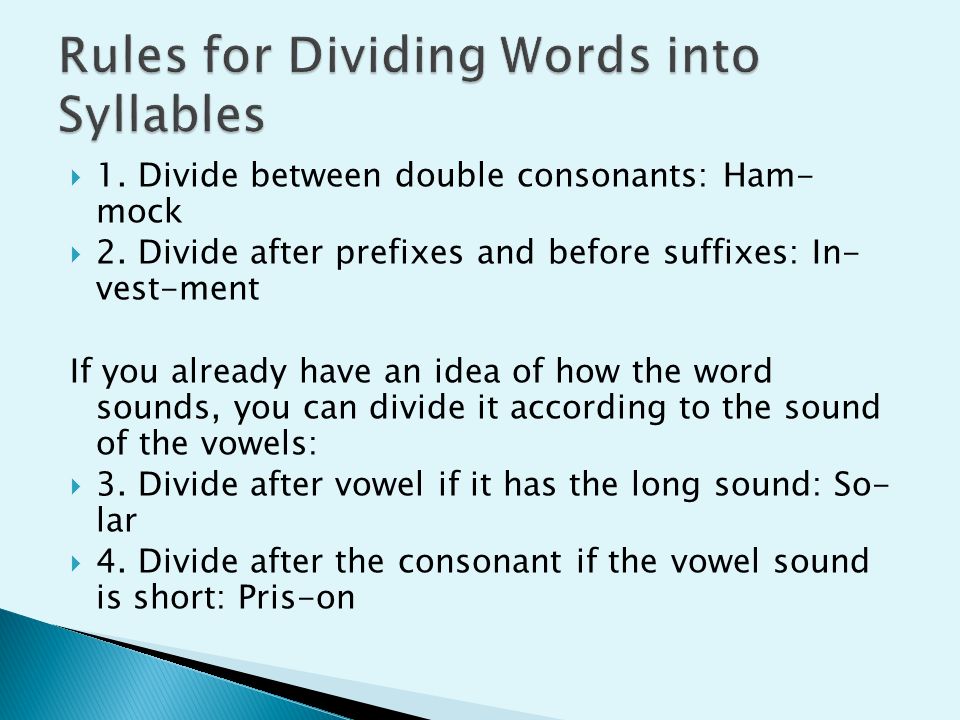

Syllable Rules

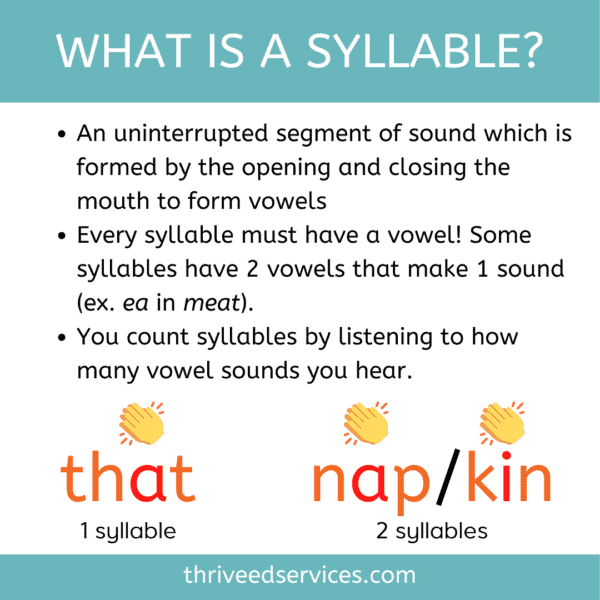

1. What is a syllable?

2. How to count syllables.

3. How to divide into syllables.

More Grammar

Trending Words

vampire

beautiful

physiotherapist

imagination

audiovisual

elephant

teacher

programme

butterfly

Halloween

Grammar Quiz

Which should you use

affect or effect?

Take the Grammar Quiz

Syllables Synonyms Rhymes

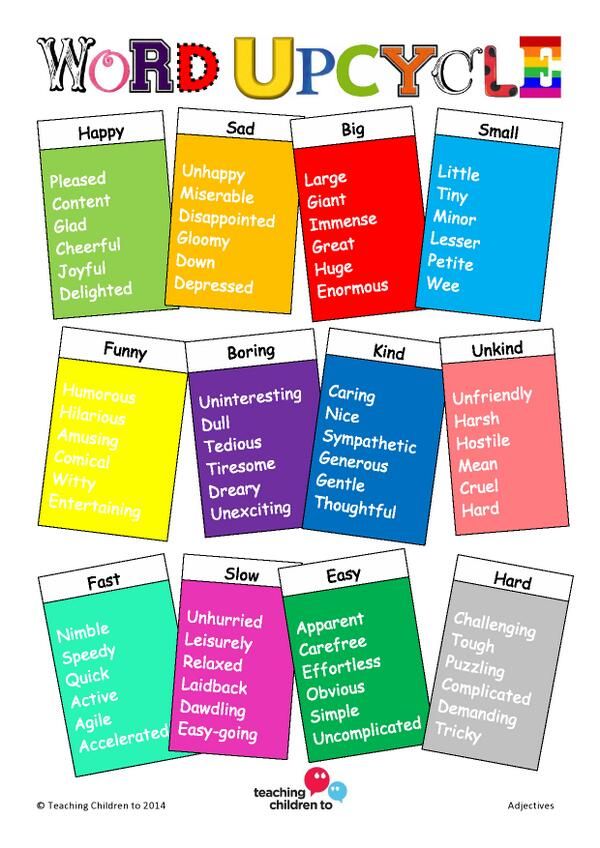

Synonyms for tired

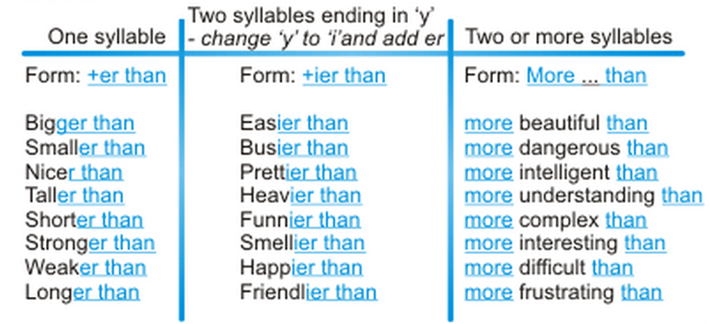

1 syllable

- bushed hear the syllables in bushed

- drawn hear the syllables in drawn

- peaked hear the syllables in peaked

- sapped hear the syllables in sapped

- stale hear the syllables in stale

- whacked hear the syllables in whacked

- drained hear the syllables in drained

- old hear the syllables in old

- pooped hear the syllables in pooped

- spent hear the syllables in spent

- trite hear the syllables in trite

2 syllables

- all-in hear the syllables in all-in

- dead beat

- dozing hear the syllables in dozing

- drowsy hear the syllables in drowsy

- groggy hear the syllables in groggy

- haggard hear the syllables in haggard

- nodding hear the syllables in nodding

- sleepy hear the syllables in sleepy

- wasted hear the syllables in wasted

- worn-out hear the syllables in worn-out

- corny hear the syllables in corny

- deadbeat hear the syllables in deadbeat

- droopy hear the syllables in droopy

- fatigued hear the syllables in fatigued

- hackneyed hear the syllables in hackneyed

- jaded hear the syllables in jaded

- rundown hear the syllables in rundown

- snoozing hear the syllables in snoozing

- weary hear the syllables in weary

3 syllables

- depleted hear the syllables in depleted

- lethargic hear the syllables in lethargic

- exhausted hear the syllables in exhausted

- overused hear the syllables in overused

Teachers

How can $250 help your students?

One prize is awarded to

one teacher, every month.

$Read the contest rules and apply

Fun Fact

In the Middle Ages,

a “moment” was 90 seconds.

!Get more facts

Grammar

Learn the rules for using

A vs. An

?A vs. An Rules

Syllables Synonyms Rhymes

What rhymes with tired

1 syllable

- fired hear the syllables in fired

- sired hear the syllables in sired

- wire hear the syllables in wire

- hired hear the syllables in hired

- spired hear the syllables in spired

- wired hear the syllables in wired

2 syllables

- acquired hear the syllables in acquired

- byard hear the syllables in byard

- desired hear the syllables in desired

- inspired hear the syllables in inspired

- required hear the syllables in required

- rewired hear the syllables in rewired

- transpired hear the syllables in transpired

- admired hear the syllables in admired

- conspired hear the syllables in conspired

- inquired hear the syllables in inquired

- rehired hear the syllables in rehired

- retired hear the syllables in retired

- rewires hear the syllables in rewires

3 syllables

- unexpired hear the syllables in unexpired

- uninspired hear the syllables in uninspired

4 syllables

- admiredly hear the syllables in admiredly

- unexpiring hear the syllables in unexpiring

Do You Know

the difference between

Lose and Loose?

Find Out Here

Parents, Teachers, StudentsDo you have a grammar question?

Need help finding a syllable count?

Want to say thank you?

Contact Us!

Feet, Not Syllables | The Haiku Experiment

Michael, thanks for your comments.

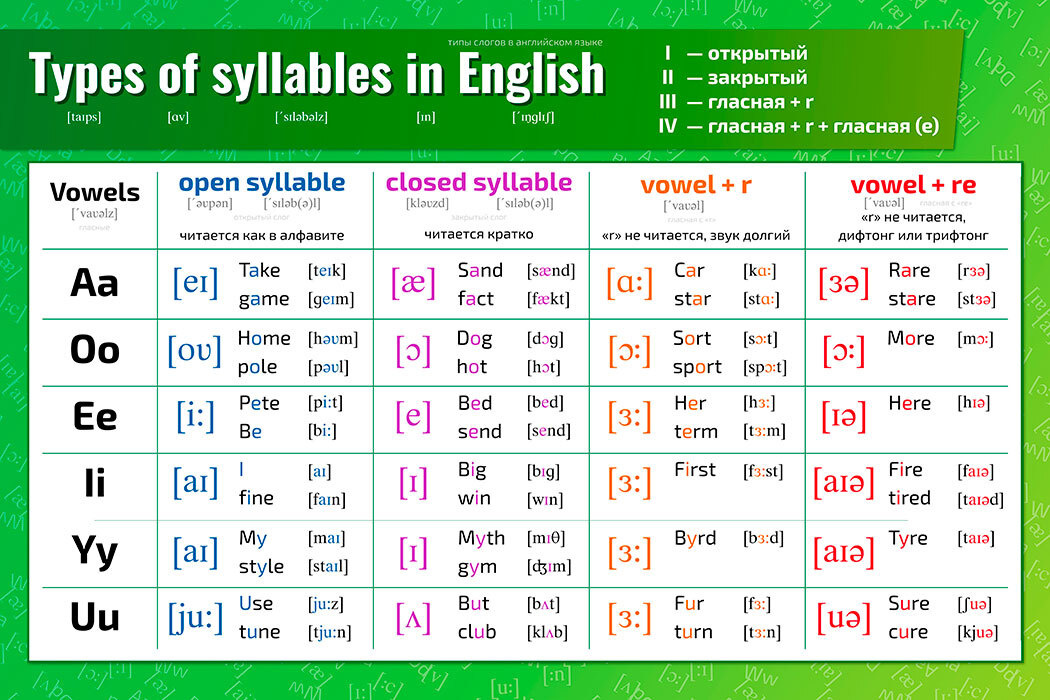

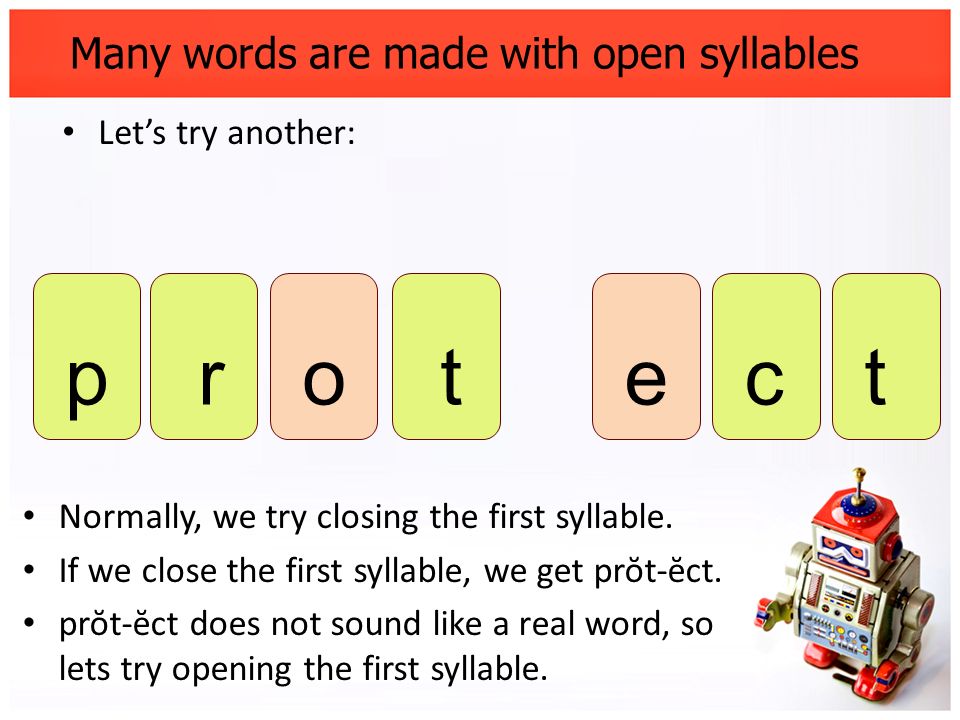

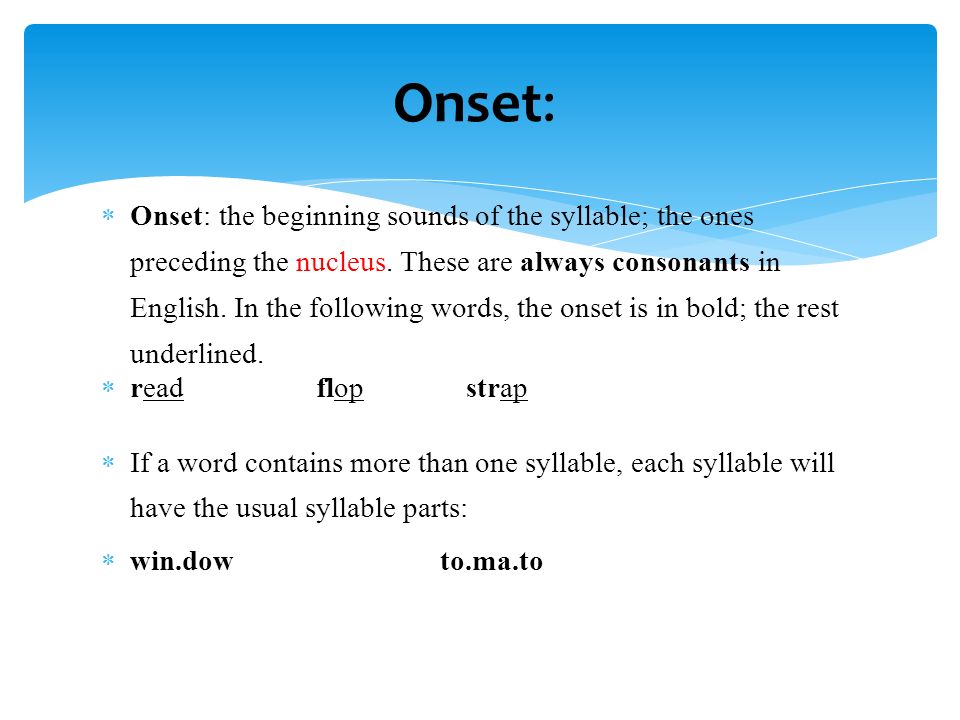

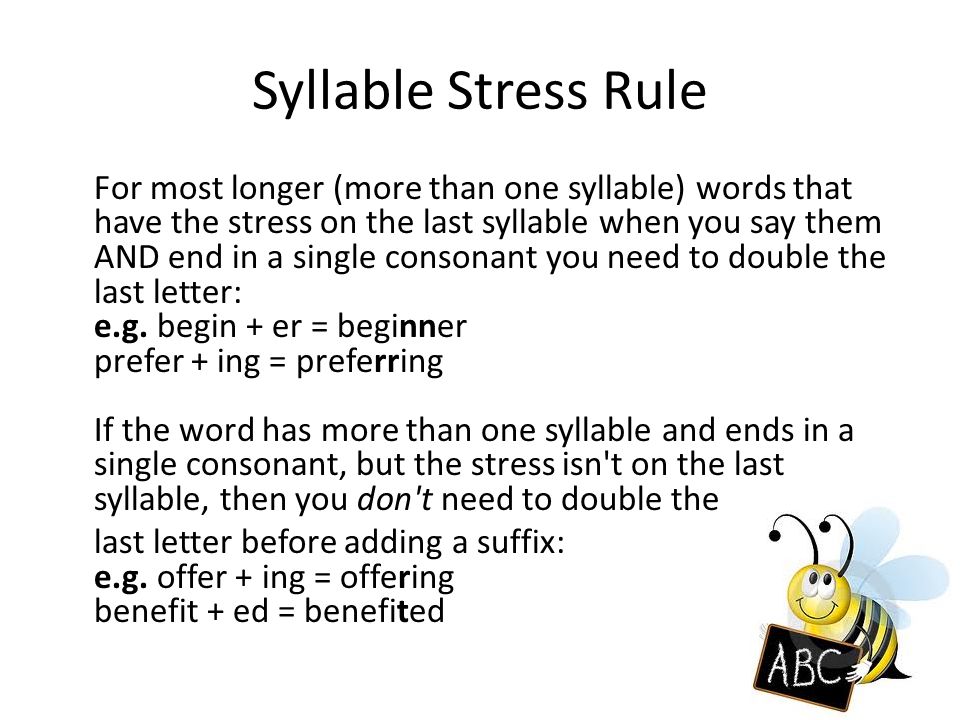

In your article you wrote that poets should understand what syllables are and should know how to count them, but the truth is that English language poets have never counted syllables, rather they they have counted the feet which measure the metric value of stressed and unstressed syllables. This is something different than just counting syllables.

English is a stressed timed language, which means that syllables aren’t uniform in the length of time and some are longer than others, this is different from syllable timed languages where every syllable has the same amount of time with no variation between them. This is why we in English count feet rather than syllables.

The first line of haiku that you quote in your article is an example of why this is:

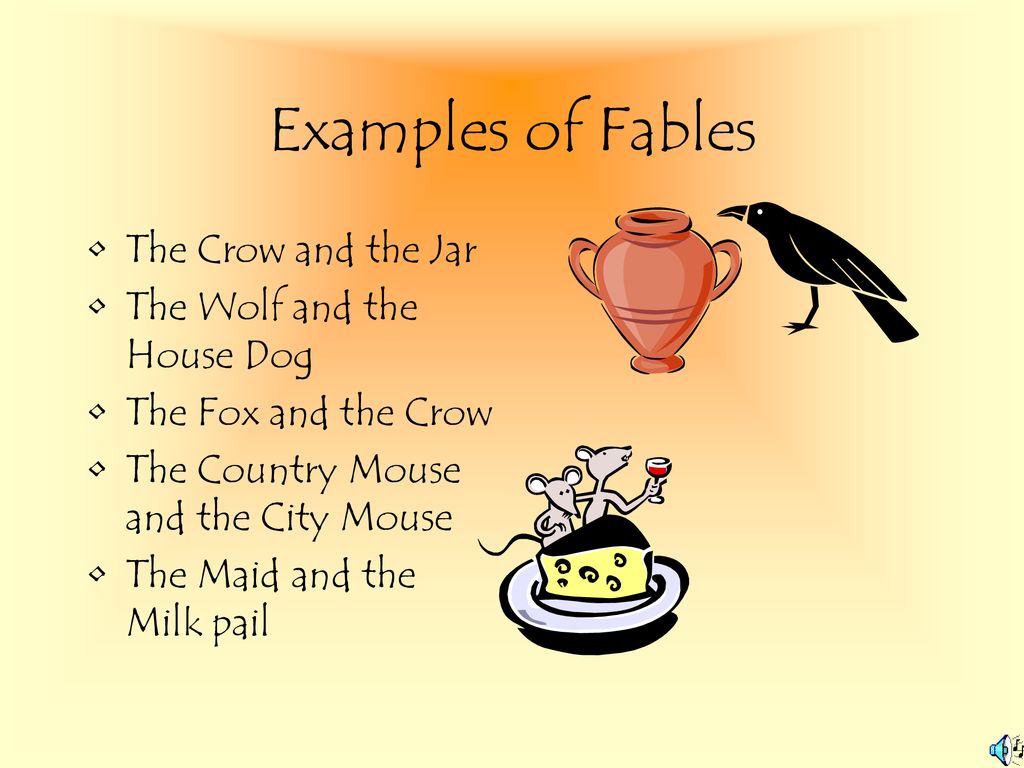

tired old work horse

stands thirsty and sweating in

summer’s sizzling heat

You state that the word “tired” has been mistakenly counted as two syllables here and it is true that “tired” spoken alone is a one syllable word. But what happens when you read it with the same timing as the other one syllable words that follow it?

But what happens when you read it with the same timing as the other one syllable words that follow it?

/ x / x

tired old work horse

By the time we get to the end of the line we are all of out breath and just crash and cannot easily connect the sentence nor the thought to the next line. We are hung out at our wit’s end here.

Even when we change the stress pattern:

x / x /

tired old work horse

The same crash at the end happens. Now let’s scan it like the person who wrote it did:

x / x / x

tired old work horse

By reading tired as having a stress at the end of the word we have placed it in rhythm that leads smoothly into the next line and allows our thought to follow as well.

It’s easy to get fooled into believing that by just counting syllables we can get the music measure of poetry because so much of our good poetry has been written by using similarly timed syllables, but that doesn’t mean that there wasn’t any written that didn’t use syllables that had different time values. I had never thought of the difference of counting feet until I read your article, so I am guilty of it as well.

I had never thought of the difference of counting feet until I read your article, so I am guilty of it as well.

Of course, there is a way to write this line to make tired read as one foot and still keep it in a natural speech rhythm:

tir’d old work horse

By using the elision the stress is taken out and the word fits into a natural rhythm. Poets in the past used this a lot as a way of to fit the past tense -ed verbs into rhythmic patterns because it knocked off a syllable from the word. It would do the same to the verb which added an extra foot to the second line of your raccoon haiku.

Of course, just using an article like we are supposed to do would do the trick as well:

a tired old work horse

This takes out the stress as well. I’d guess the reason why we stress the word without the article is because we unconsciously fit it into a workable speech pattern. But that is the kind of affection in language which happens when you try to mimic the writing in Japanese.

Stress is, of course, is something that Japanese language really doesn’t have, but it does use pitch and by looking at pitch we can get some ideas about how Japanese words work as feet (and syllables) in relationship to how we see them per our words.

To quote from the translated version of “The Poetics of Japanese Verse” by Koji Kawamoto (pg. 189-190):

“In modern standard Japanese, words of two morale or more can be divided into two broad categories, namely, those in which the first mora only is pronounced with a high pitch (A-me, SU-ga-ta, O-o-ka-mi, KA-ge-bo-shi) and those which start with a low-pitched first mora followed by one or more high-pitched mora. Of these, the latter group can be further subdivided into those words which end on a high pitch (sa-RA, o-N-NA, to-MO-DA-CHI, o-SHO-O-GA-TSU) and those which return to a low pitch before ending (ko-KO-ro, ka-RA-KA-sa, i-NO-CHI-BI-ro-i, ka-MI-NA-RI-O-ya-ji). The arrangement of high and low pitched morae within individual words thus comes down to a simple dichotomy: “whether a high pitch will stop one mora, or continue for two or more –not forgetting of course the restriction that a high pitch cannot emerge more than once within a word (i. e., with low-pitched morae spaced in between)” (quote is from Shibata Takeshi’s “Nihongo no akusento”).

e., with low-pitched morae spaced in between)” (quote is from Shibata Takeshi’s “Nihongo no akusento”).

The important part to consider in the above is how “a high pitch will stop at one mora, or continue for two or more” because it explains how a high pitch will eat up feet. A word noted above like “tomodachi” shows how the high pitch will take a 4 syllable (mora) word and reduce it two two pitch feet, and how in a Chinese character compound “onyomi” word like “oshoōgatsu” it moves across two characters and reduces six mora into two pitches. It can even move across two compound words like “inochibiro” and two separate words like “kaminari oyaji” to reduce 6 mora into 2 pitches and 7 mora into 4 pitches.

In the previous post I mentioned that “kawa” was one syllable and you corrected me by saying that it was two and you are right, ka-WA makes it two pitches. But if you put it together with something like se-MI you will still get the word ka-WA-SE-MI (kingfisher), which is a good example of how the high pitch dominates the low pitch in terms of feet and changes something that you would think naturally would be 4 pitches into being 2.

There are dictionaries in Japanese that are only for showing how to accent words properly and using the NHK Japanese Pronunciation Accent Dictionary (NHK日本語発音アクセント辞典) I went and checked where all the high pitch and low pitched was for all the words in the haiku that were in Keiko Imaoka’s article.

yuKU HARU YA/ toRI naKI uO NO ME ni NAmida

Has 11 transitions between high and low pitch.

NEko no meSHI shoUBAN suRU YA / suZUME NO ko

Has 10 transitions.

WAre to KIte aSOBE YA /oYA NO NAi suZUME

Has 11 transitions.

uGUisu no naKU YA / CHIISAki kuCHI aKETE

Has 9 transitions.

So once you start to consider these haiku on the terms of how our language is scanned the Japanese lines actually shrinks in feet, which something that is impossible in English, and thus shows the difficulty of trying to consider what the length of haiku should be in English. You can just look at it uncritically and say that Japanese haiku scans less this 17 syllables, so English should also be cut down to 11 syllables, but to argue that this is acceptable because 17 syllables in English carries more information than the Japanese misses the fact that the Japanese carries much more information per pitch foot than the English does. Which is how it is able to shrink 17 down to 11 or less in the above.

Which is how it is able to shrink 17 down to 11 or less in the above.

Keiko Imaoka made mention of how “The mnemonic quality of 5-7-5 Japanese phrases is much closer to that of metered rhymes in English” and the theory of how this works is explained clearly in Kawamoto’s book. In 1922 Doi Kichi developed the idea of the “bimoraic foot,” which is “a unit of time which is always –at least in theory– of the same duration, regardless of the number of (vocalized) morae” (pg. 200). This foot “entails one important condition, namely, that a single mora alone may count for a whole beat under certain circumstances.” This is accomplished when this single mora is made to “either lengthen (the additional mora) or place a stop (pause) after it so that it balances with the preceding two.” (pg. 202)

Doi also argued that bimoraic foot showed a stress pattern and that by “clapping or tapping to the beat” one can understand “where such stresses occur, it soon becomes clear that they fall consistently on the first mora of each two-mora unit. ” When it comes to the single mora that counts more than one, the reader “accents” it and “then inserts a pause (or lengthens the vowel) to ensure that an appropriate stress falls on the first mora of the next bimoraic group.” (pg. 204) This idea of that Japanese prosody has stress, and has a stress pattern that is accented and unaccented is something that we can readily understand. It is what feet are in English.

” When it comes to the single mora that counts more than one, the reader “accents” it and “then inserts a pause (or lengthens the vowel) to ensure that an appropriate stress falls on the first mora of the next bimoraic group.” (pg. 204) This idea of that Japanese prosody has stress, and has a stress pattern that is accented and unaccented is something that we can readily understand. It is what feet are in English.

Kawamoto (p.g. 283-284) used two of Basho’s haiku to show how this works in them:

fu-ru | i- ke | ya — | — — |

ka-wa | zu — | to- bi- | ko- mu || mi- zu | no — | o- to| — — ||

It is pretty easy to pick up the beats in this if you accent the beginning of each mora. The vowel in “ya” in the first line gets lengthened to complete the bimoraic rhythm and the two pauses that follow it give the reader the breath space to accent on the “ka” that follows it. The vowel of “zu” and the vowel for “no” are lengthened to complete the rhythm.

Kawamoto also gives this Basho haiku as an example of when the first 12 mora are connected:

sa-mi- | da-re |o — || a-tsu- | me-te | ha- ya- | shi — ||

Mo-ga- | mi — | ga-wa ||

And then says that the meter above had been extinct for centuries and it was probably never intended to be read this way and gave this as a better example:

sa-mi- | da-re |o — | — — ||

a-tsu- | me-te | ha- ya- | shi — || Mo-ga- | mi — | ga-wa | — — ||

Both examples have the single mora with the vowel elongated and the the second version has the five mora lines elongated to fit in with the meter and the two five mora sections have the silent bimoraic feet at the end to fill out the measure.

Kawamoto argues that “the individual seven and five mora verses of Japanese prosody each form a discrete metrical unit compared of four bimoriac feet, or in musical parlance, a four-beat quadruple-time bar” (pg. 223). This is why he adds the silent bimoras at the end of each 5 section to fill out the measure. I’m not sure what the reason for this is, but we, and maybe it is because our own poetry has a lot of line breaks, don’t have the need to fill out the form so roundly.

Which means, then when you look at this model which is the accepted view on what the metrics of Japanese poetry are, then it is easy to see that what is discussed here is that the lines of a haiku will always scan out as being 6-8-6 feet. So, then 20 feet is what haiku counts out to in the way we scan our own poetry (discounting the two bimoras which are used to fill out the two 5 lines.)

It’s unfortunate that Imaoka never went into how 5-7-5 in Japanese related to English metrics, rather instead she inferred that if English haiku was written in something that approximated the length of the “mnemonic quality of 5-7-5 Japanese phrases” it meant that we were “concerning ourselves too much with the outward form of haiku” and thus “can lose sight of its essence. ” Its a little hard to understand how, given how our language and our poetry relies on sound as a means to create added meaning, giving up on the mnemonic qualities would make English language haiku the poetic equal of Japanese haiku.

” Its a little hard to understand how, given how our language and our poetry relies on sound as a means to create added meaning, giving up on the mnemonic qualities would make English language haiku the poetic equal of Japanese haiku.

One gets the sense the Imaoka was the one who was more interested in form over language. If we look at this example she gave us we find this to be true:

across the arroyo

deep scars

of a joy ride

could be rewritten to approximate the 3-5-3 form as

across the

arroyo, deep scars

of a joy ride

without affecting the meaning. As it is, doing so sacrifices too much in the natural flow of words and interferes with the image.

She argues that the second version has an unnatural flow to it and that this blurs the image, when in fact the opposite is true. The first line in the first version is unnatural, and because it isn’t in a natural speech pattern we run out of breath at the end of the line and our mind just flattens out. This unnatural breath pauses damages the images in the haiku because we spend time and energy just to find the proper linguistic syntax to fit it into, and by doing so are made unable to focus on the imagery. However, by rearranging the lines and inserting a comma, the second version is now into a natural speech rhythm and we are able to see the images a lot brighter and clearer because of it.

This unnatural breath pauses damages the images in the haiku because we spend time and energy just to find the proper linguistic syntax to fit it into, and by doing so are made unable to focus on the imagery. However, by rearranging the lines and inserting a comma, the second version is now into a natural speech rhythm and we are able to see the images a lot brighter and clearer because of it.

Imaoka’s statement that the “the type of unnatural line breaks seen in the latter is a problem associated with the 3-5-3 (or other short) form, whereas the 5-7-5 form is long enough to accommodate natural line breaks dictated by the English grammar, due to a greater degree of freedom provided by the extra syllables,” is only an argument about form because it missed the point about how the English language works and how unnatural the whole first line of “across the arroyo” is in the first place. Besides adding the proper punctuation in, if we use proper grammar and and rearranging the imagery to “there are deep scars across…. .” etc. the writer is able to use language to reinforce and add unstated emotional content into this haiku.

.” etc. the writer is able to use language to reinforce and add unstated emotional content into this haiku.

Which returns us to my point about poetry being more than just imagery. Poetry is a mix of sound and images to produce the emotional energy that the poet feels towards what they are writing about. The reason why English language haiku is such a dead dry language is because people have conned themselves into believing that all you have to do is to create poetry is to write out imagery and this was OK because that is what the Japanese did in their haiku in for centuries. Of course, these ideas about Japanese haiku were completely wrong and are now cached in the dust bin of history. This imagery only theory about haiku lingers on, but people are only fooling themselves because in the end all haiku written in English will be judged on the what the standards of English language poetry are and those standards will always insist that both sight and sound are essential for good writing.

I am not advocating a strict mandate that states that all English language haiku must be 20 feet in length, but I do advocate that haiku has enough space so one can write in a natural voice within a haiku. I find that Imaoka’s ideas about the length of haiku to be based on uncritical thinking and are ideas which deaden of the use of language in haiku. Instead of continuing to come up with schemes that try to emulate Japanese haiku, it is high well past the time that writers in English start to write within the poetic traditions of their own language.

I know that this sticks in the craw if a lot of people in haiku because they have been deceiving themselves for such a long about how they are “so different” from “mainstream poetry.” The truth is that haiku writers aren’t different and that they have only made themselves worse poets by thinking that they are. It’s time to realize this.

Like this:

Like Loading...

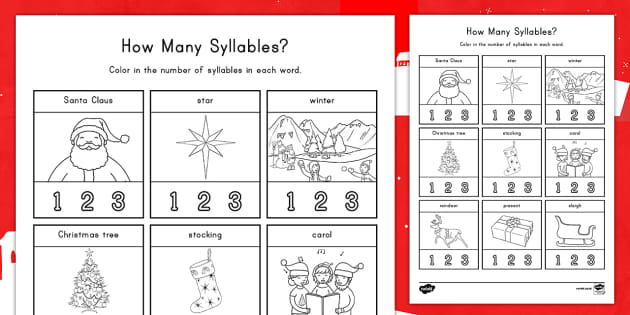

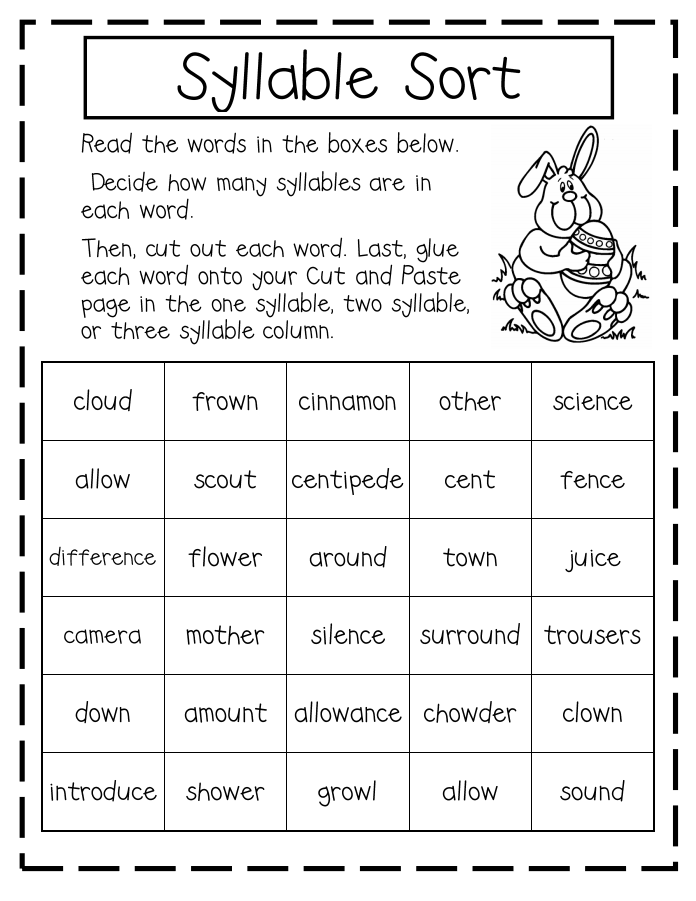

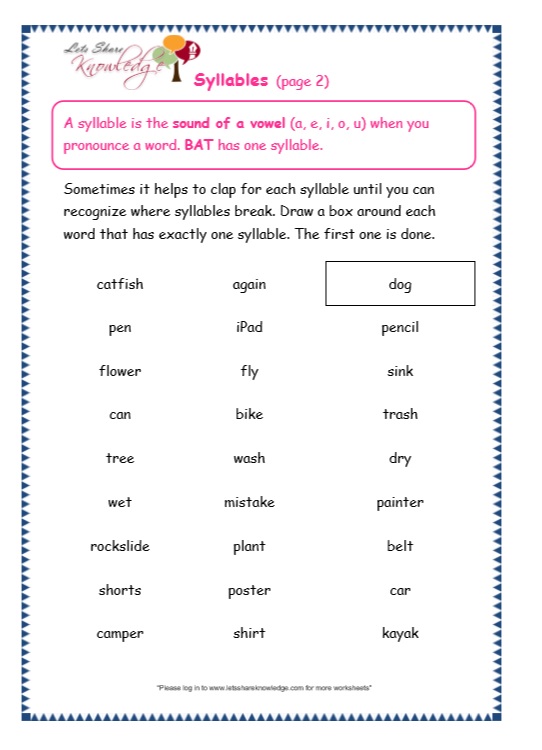

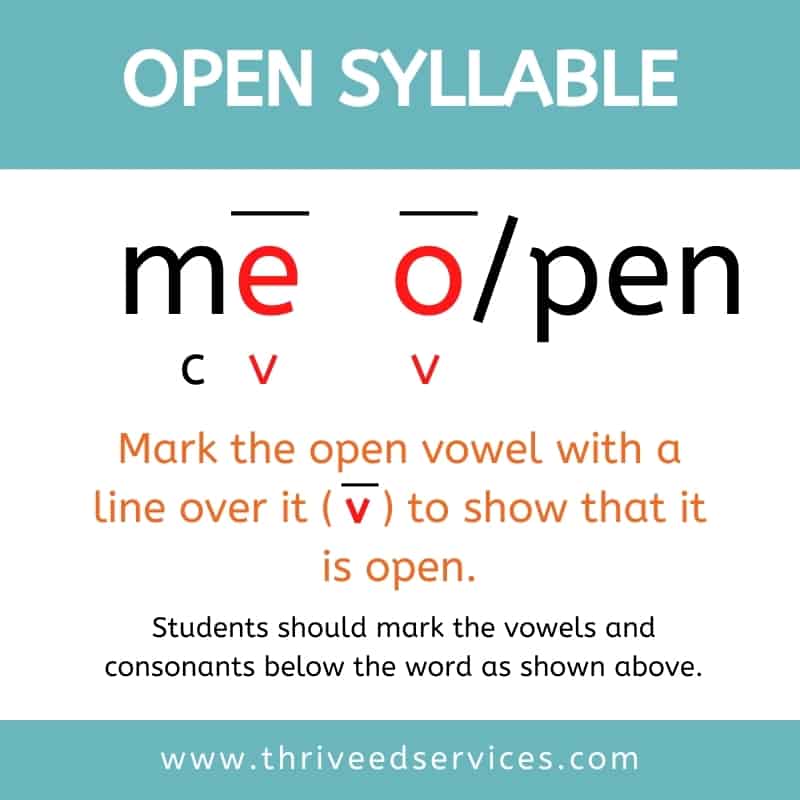

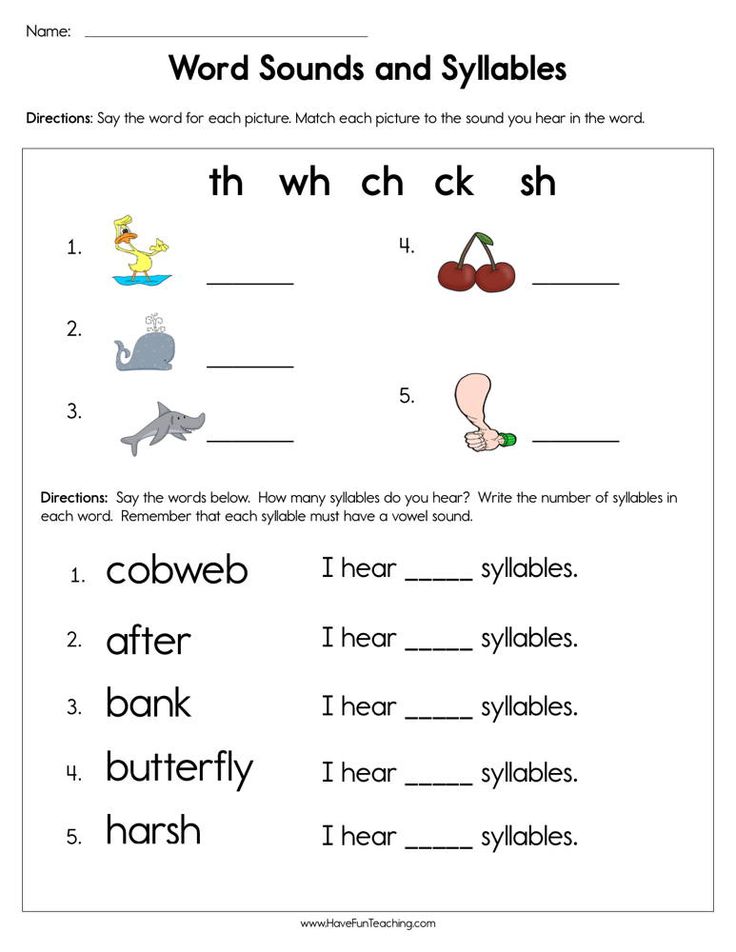

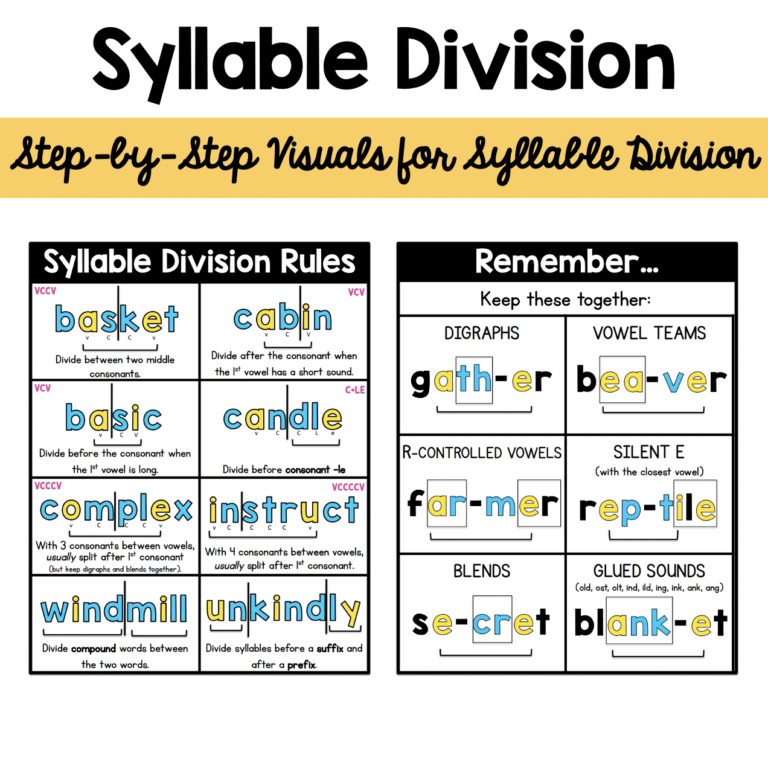

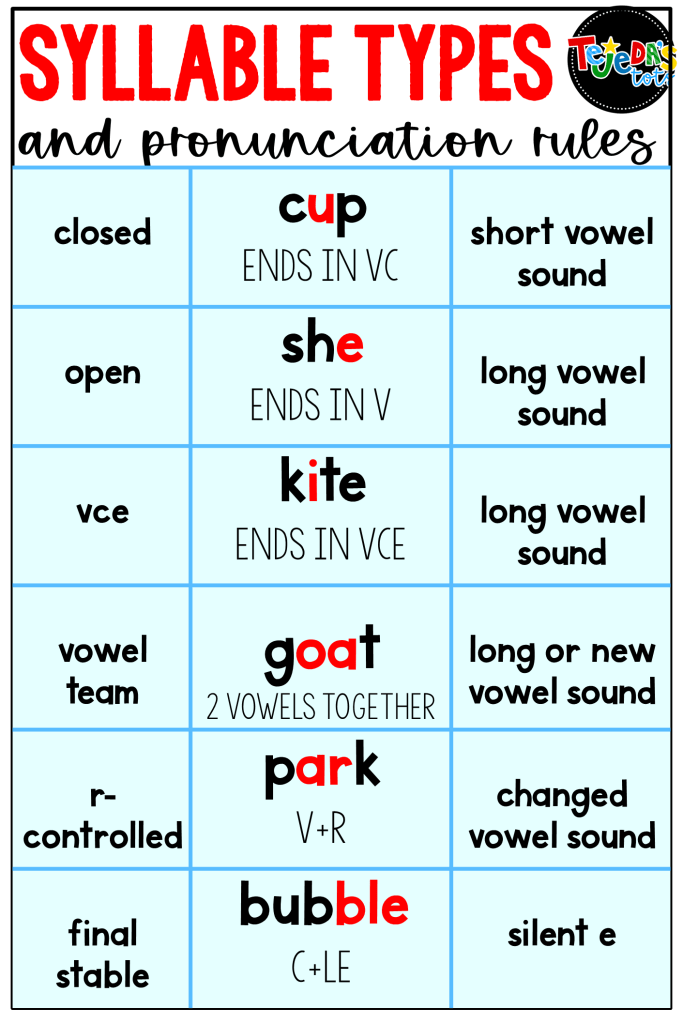

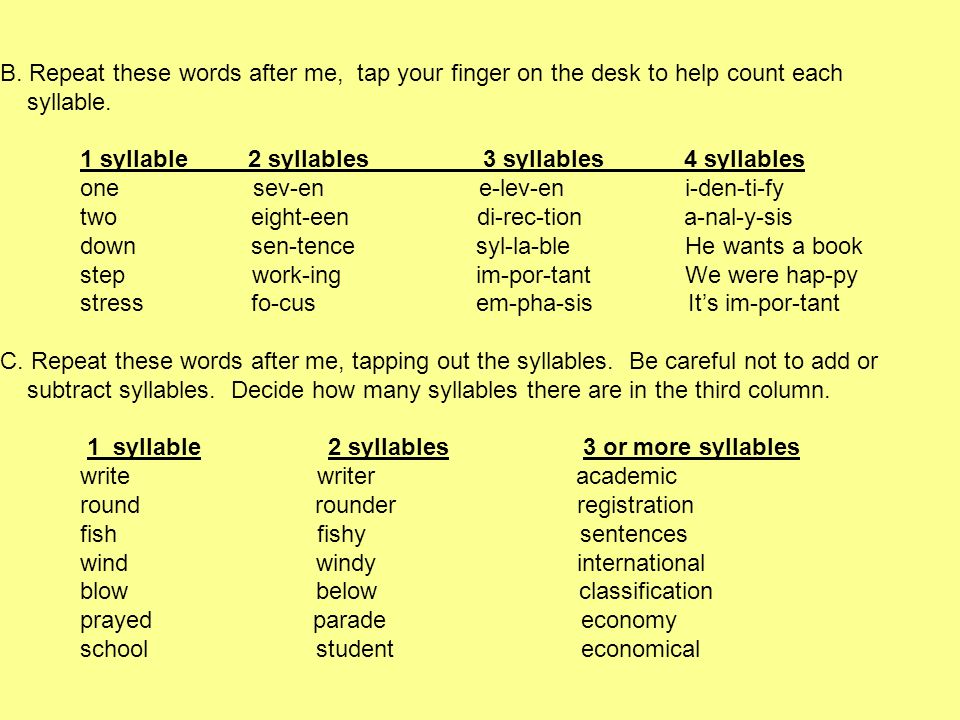

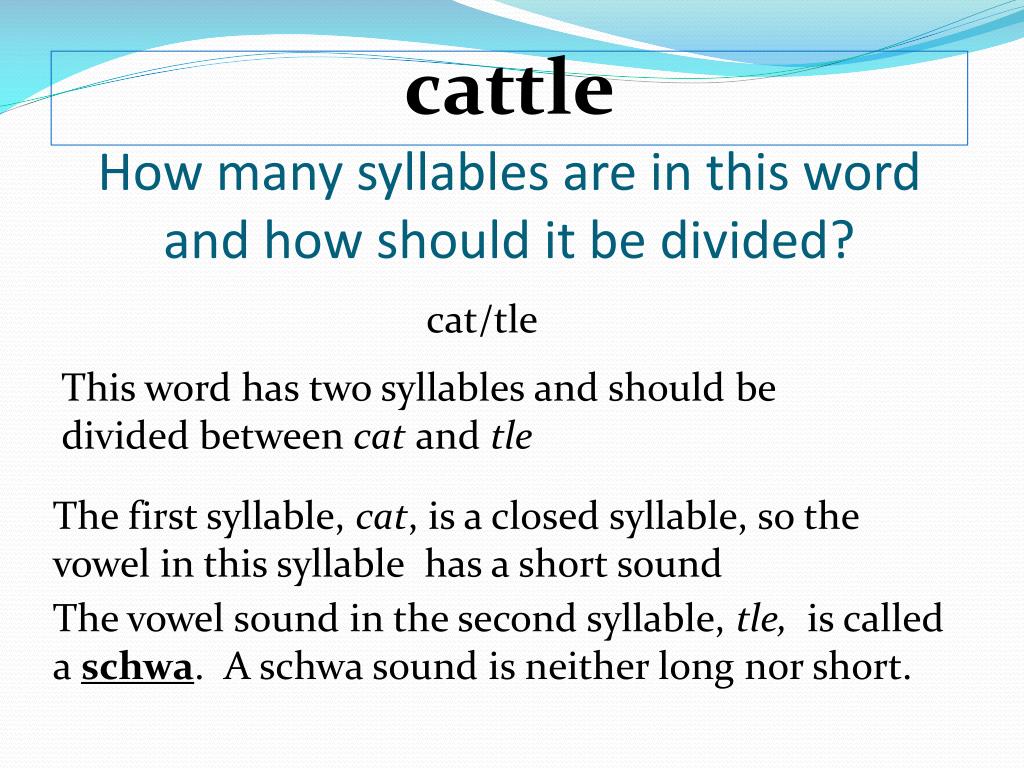

| Main page CATEGORIES: Archeology TOP 10 on the site Preparation of disinfectant solutions of various concentrations Technique of the lower direct ball delivery. Franco-Prussian war (causes and consequences) Organization of the work of the treatment room Semantic and mechanical memorization, their place and role in the assimilation of knowledge Communication barriers and ways to overcome them Processing of reusable medical devices Samples of journalistic style text Four types of rebalancing Problems with answers for the All-Russian Olympiad in Law We will help you write your papers! DID YOU KNOW? The influence of society on a person Preparation of disinfectant solutions of various concentrations Practical work in geography for the 6th grade Organization of the work of the treatment room Changes in inanimate nature in autumn Treatment room cleaning Solfeggio. Beam systems. Determination of support reactions and pinching moments | ⇐ PreviousPage 10 of 12Next ⇒ The speech therapist names two- and three-syllable words mixed up. Pupils raise, respectively, the scheme of a two- or three-syllable word. hens, chicken, puddle, puddle, soap, washed, drove, carried, soap VI. Graphic dictation of disyllabic and trisyllabic words . (You may use the words given in V.) VII. Summary of the lesson. Speech therapist. What did you learn to do today? Session 3 Subject. Same. Purpose. To give students an idea of the syllable-forming role of the vowel. Teach children to distinguish vowels from words.

Course of the lesson, I. Organizational moment. Pupils will sit down and name a word consisting of two syllables. II. Division of words into syllables and isolation of vowels by voice : a) from disyllabic words. The speech therapist pronounces the word mountains in syllables, highlighting the vowels with his voice: “Go- what vowel do you hear in this syllable? (o), ry-(s). How many syllables are in the word mountains? (Two.) How many vowels are in this word? (Two.) Name the vowels in the word mountains (oh, s) again. Two or three more words are parsed similarly. The speech therapist draws the attention of students to the fact that in words the number of vowels corresponds to the number of syllables; b) from monosyllabic words. Speech therapist pronounces word house. Pupils identify a vowel with their voice and determine the number of syllables. Then the speech therapist asks the students how they guessed that the word had one syllable; c) from three-syllable words. Speech therapist. What helped you determine the number of syllables in a word? (Number of vowels.) Then the speech therapist together with the students concludes: “The number of syllables in words depends on the number of vowels, and the number of vowels should correspond to the number of syllables in the word.” III. Summary of the lesson. Speech therapist. What did you learn to do in class today? What should be remembered when dividing words into syllables? Practice exercises Identify vowels from words. Determine the number of syllables in a word. (Each time the speech therapist requires proof why the word has one, two, three syllables. The speech therapist pronounces the word the way it is spelled.) , bush, steel, bridge, brother, friend, chair, wedge, whip, bayonet; b) from two-syllable words: soap, notes, flour, soda, sting, teeth, chickens, map, cat, pen, fish, stuffy, magnificent, donut, horns, wing; c) from three-syllable words: car, shovel, magpie, houses, fishermen, swans, goslings, paper, boots, coast. Lesson 4 Topic. Same. Purpose. To consolidate in children the ability to divide words into syllables, to distinguish vowels from words. Equipment. Subject pictures, word schemes.

I. Organizational moment. The student who will name the word consisting of three syllables will sit down. II . Consolidation of the material of the previous lesson. The speech therapist puts on the board three pictures depicting a ball, a vase, lemons. Task 1. Say what is shown in the pictures. Highlight the vowels with your voice. Count how many syllables are in the word. Pronounce the word in syllables. Task 2. Draw the words graphically. Write the corresponding vowel above each syllable. notes, poppy, fishermen

__a___

The speech therapist may use the words given above in the Practice Exercises. Task 3. Name the picture, give a graphic representation of the word, write a vowel above the corresponding syllable. Approximate list of pictures: cat, fly, cubes, oak, fish, paper, cancer, hand, shirt, etc. Checking the work done. Summary of the lesson. Speech therapist. What did you do in class today? Lesson 5 Topic. Same. Purpose. Teach children to determine the order of syllables in a word. Equipment. Subject pictures, syllables from the split alphabet. Lesson progress. I. Organizational moment . The student who will name the word consisting of two syllables and correctly identify the vowel sounds will sit down. II. Consolidation of the material of previous lessons.

1) Graphic dictation with emphasis on vowels. The speech therapist pronounces the words as they are written and reminds you to separate words with a comma. Pupils in notebooks give a graphic representation of these words and write vowels above the corresponding syllable. Approximate list of words: ball, goose, rocket, knife, needle, rainbow, gate, hedgehog, house, hat, music, cotton wool, summer, weather. 2) Checking the work done. The speech therapist names the words in the order of the pictures presented, the students name the number of syllables and vowels in the word. III. The order of syllables in the word . The speech therapist puts pictures of a bag and a car on the board. The name of these pictures pronounces deformedly: ka-sum, shi-ma-na. Then he asks: did the words come out? (Failed) Rearranges syllables and pronounces words correctly. Now got the words? (Got it.) Why didn't the words come out in the first case? (The syllables were pronounced out of order.) To get words, it is necessary not to confuse syllables and pronounce them in order. Task 1. Listen to the poem "Peter and the words", complete it by making the last word from the suggested syllables. (The syllables WE, YOU, YOU are put on the board.) These are the words he used to run to his mother one day: If YOU washed your hands, If we wash your hands, If YOU wash your hands, then your hands .... Task 2. Compose words from syllables: a) based on the picture, b) without relying on the picture. Speech therapist pronounces the words, rearranging the syllables, students correctly name the word. a) pa-la, ki-ra, ki-ma, ry-sha, ba-shu, zy-ko b) ka-ru, ti-no, su-ne, ru-be, ma-zi , zhu-ho Task 3. Make the correct words from the syllables of the split alphabet. ma-ra, ni-sa, ka-bel, ro-ved, ka-shap, bik-ku, mar-ko, ki-mar IV. Summary of the lesson. Speech therapist. What have you learned today? Stress Speech therapist for practical learning of the topic "Stress" offers students to perform various exercises. Task 1. Listen and slap the rhythm patterns. a) x-x-x, x-x-x, x-x-x b) x-x, x-x, x-x, etc. .c) x-x x-X, x-X, etc. d) x-X-x, x-X-x, x-X-x, etc. e) X-x-x, X- x-x, X-x-x, etc. e) x-x-X, x-x-X, x-x-X e) x-x-X-x, x-x -X-x, x-x-X-x Task 2. Listen and repeat the words, slap the rhythmic pattern of the words. (The speech therapist calls the word, highlighting the stressed syllable with his voice, students slap the rhythmic pattern of the word, show the stressed syllable with a loud clap, for example: fish — Xx. a) fish, linden, grief, juices, hare, quiet, hands, earth, walks, drives, I A shines, warms, red, blue, bitter, sculpts, gentle, bird b) hand, oaks, face, fox , trees, flowers, snow, window; spot, village, steps, shoulder, run, carry, carpets, tables, glass c) rocket, lemons, paper, snowdrifts, cheerful, chicken, exits, capital, basket, fogs, shirt, child mirror, squirrel, windmill, sun e) cockerel, scallop, crocodile, conductor, machine gun, boots, parrot, plane, dragonfly, telephone, wires, tell, put e) calendar, parrot, sundresses, crocodiles, binders, fence

Task 3. Sample: ruki ru, u

(You can use the vocabulary from the previous task.)

Training exercises (Children haveindividual cards on which deformed words are given: a) from picture mi, b) without pictures. Pupils complete tasks independently, after which work is checked.) a) using reference pictures: . ka-mas, ta-pas, you-kus, ry-sha, ki-ru, pa-li, gi-no, lo-we, ta-kar, ka-circle, ka-shap, lash-sha, on-weight, shock-me, ba-tru, ka-bul, ka-mis, ma-do, shi-u, pa-hat, ka-bowl, lo-shi, Zhi-ly, ba-zha b ) without pictures: bar-ry, ki-nose, na-shi-ma, tets-si, chi-klu, ka-ruch, ka-ba-bush, za-ro, letz-pa, cha-te, ki-och, ka-de-shower, ka-kor, we-mo-li, la-cook, ka-lozh, ly-hundred Complete the word by adding a syllable.

, gr...(would) b) without pictures: du...(would), two... (you), wing...(tso), roof...(sha), ball ...(ph), tap...(ki) 3. Make a word by adding the initial syllable. (but)...juice, (for)...boron, (ry)...ba, (me)...shock, (flax)...ta, (one hundred)...kan, (mis)...ka, (gri)...by, (kry)...sha, (bel)...ka 4. From the words of task 3, select the words corresponding to the schemes:

ha gi gu zhi |

| ba would si shcha dock |

no rya tone Mu ket

| ha rubbish hee ka ly |

bu

| then sa zhi kar |

| ba ry |

le

| ba ry |

| cap fell floor push |

| ma ka Sa Yes |

| sum bul |

7. Change the word so that it has two syllables. Make a diagram for the newly formed words

Change the word so that it has two syllables. Make a diagram for the newly formed words

, highlight the vowels.

som, poppy, crayfish, night, garden, cheese, juice, mole, bush, bridge, knife

8. Change the word so that one syllable is obtained. Newly formed words

write down, underline the vowel.

Sample: juice - juice.

juices, noses, bushes, tables, houses, cats

9. Change the word so that there are two, then three syllables in the word. Make a

scheme for newly formed words, highlight the vowels.

Sample: house - house - cottages salt - salt - salty. house, mushroom, catfish, mole, bush, salt, table, pancake, knife, leaf (In case of difficulty, a speech therapist helps.)

10. Fill in the missing syllable. Make a diagram of words, underline the vowels. Write down the words in syllables. (Require pronunciation of syllables when recording. )

)

a) ...- SHI-NA B) RA-...-TA C) WE-SHA-... D) ... ZHI-NA

...- ZHAMA E-...- TA KO-ZHU -… GA-ZE-…

… -RO-JOK KU-…-KI TOR-MO-… AZ-…-KA

… -BUSH-KA VOL-…-TA LINE-… MA-…- ZIN

... - RAD-KA MO-...-ZY KA-RAN-... STAR-...-KA

11. Write down the words. Divide them into syllables, underline the vowels.

a) goat, puddle, sleigh, winter, fox, rose, Masha, moon, frame, grove, Nova, grass, school, plate, book, brand, bridges, letters, hat, jacket, map, sofa, kid, house, plant, banana, lemon, garden, voice, pie, mother, cardboard, sheet, mattress, jacket, circle

| 0) work | milk | blisters | hunting | draw |

| machine | factories | boots | sedge | think |

| music | wagons | axes | lake | wash |

| birch | crow | motors | lessons | sick |

| sails | magpie | crackers | ducklings | digging |

| c) potatoes | shirt | fair | toffee | nettle |

| picture | thread | sparkle | testis | apples |

| basket | girl | toy | Alenka | tables |

| leaves | gooseberry | cup | Alyoshka | bears |

| carrot | mug | colorful | cucumber | crib |

| d) airplanes | caterpillar | lark | green | [ |

| cases | machine guns | colt | pretty | |

| telephones | bird cherry | crow | bell | |

| scratch | turtle | painted | toy | |

| comrades | motor ships | uttered | coil | |

| strawberry | milkmen | collective farmers | cubs | |

| fed | velvet | currant | messed up | |

| terry | crumbled | on duty | dropped |

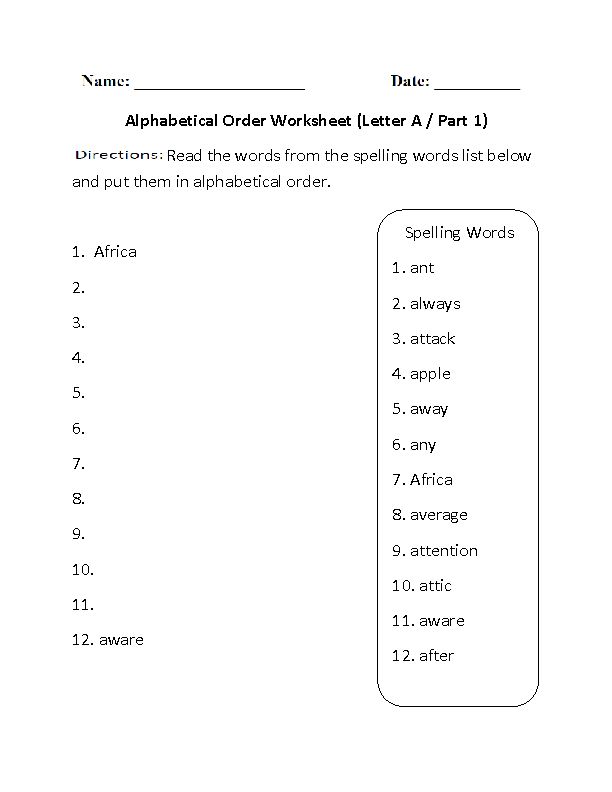

12. First write down the words consisting of one syllable, then of two and three

First write down the words consisting of one syllable, then of two and three

syllables. Underline the vowels.

cannon, soup, cat, boots, pumpkin, key, cherries, onions, lynx, brother, guys, boys, moan, cabbage, pike, silence, rocket

Graphic dictations with emphasis on vowels. The speech therapist uses the words of the previous tasks. Reminds students about the syllable-by-syllable pronunciation of words.

Write out from the text words consisting of one syllable in one column, words consisting of two syllables - in another, words of three - in the third. Underline the vowels.

The house has a garden. Flower bed in the garden. There are different flowers in the flower bed: tulips, roses, poppies.

This is our river. There are pike, ruff, crucian carp in the river. Volodya is fishing. Here is the bream. Volodya is carrying a bream to his grandmother.

Petya's father is a carpenter. Vera's dad is a cook. Polina's dad is a captain. Natasha is a doctor. Rita has a steelmaker.

Rita has a steelmaker.

Morning.

Wash hands, face and neck in the morning. Here is the teapot. Drink the tea. Go for a walk.

15. Write the text without dividing the words into syllables. Underline the vowels.

Ka-te yes we-lo. O-on we-la ru-ki, face, neck. Ru-ki, face, she-I would be white.

At the house there would be a puddle. On the lu-zhu se-whether gu-si. Gu-si would-whether se-ry.

Ko-no-whether in the lu-gu. Ko-no e-li se-but. Pa-sha, go-no one. E-something, but on the zi-mu.

Ma-ma and de-ti went away. Cat-ka Mur-ka do-ma. Cat-ka is-ka-la e-du. On the floor there would be fish. Mur-ka took the fish and e-la on the floor. Cat-ka Mur-ka is sy-ta, but there are no fish.

Summer-to,

On-stu-pi-lo-le-to. Po-la-na-po-ro-ta colors-ta-mi. Girls-voch-ki rva-whether you flowers. Ri-you have a big bouquet of ko-lo-kol-chi-kov. Ma-sha has bu-ket ro-ma-shek. So-nya ple-la ve-night-ki. Everyone would-lo ve-se-lo.

Winter.

Winter came cold. Lots of snow all around. Na-me-lo pain-shi-e su-ro-by. De-ti on the mountain. O-no ka-ta-yut-sya on skis, and Mi-sha and Ko-la on the pond. They have horses. Ve-se-lo ka-tat-sya on skates.

O-canopy.

Here comes autumn. Leaf-I pa-da-yut. Tra-va on-yellow-te-la. Flowers-you for-vya-whether. The wind's blowing. I-det rain-dick.

Weight per.

On-stu-pi-la weight-on. Snow is melting. For-ka-for-for-you-e pro-ta-lin-ki. For-zhur-cha-li ru-chee-ki. Re-bya-tish-ki pus-ka-yut ko-slave-li-ki.

16. Write down the sentences, divide the words into syllables. Underline the vowels. Put stress on words.

It was summer. Bring the fish. It was winter.

Tanya is happy. They drank lime. The sled is new.

Children sang. Catch the fish. Chizhi sang.

They washed their hands. Bring water. Washed feet.

Mom is at home. Were at home. Bring the goat.

Were at home. Bring the goat.

Check your work! The number of syllables should match the number of vowels in the word.

17. Write down sentences, divide words into syllables, pronounce each syllable. Put the stress on the underlined words.

Mother gave soap. Kolya was given porridge. Masha washed face. The hay was dry. Tanya was washing hands. Chickens drank water. Nanny soap Vika. The morning was clear. Children were at home. The fox dug a hole .

Sima, carry saw. Kolya, drank linden . Dad, bring skis. Lena, bring hay. Mom, cook meat.

Write the sentences, divide the words into syllables, pronounce the syllables Underline the vowels of the first row.

Mila sculpts. Linda is carrying. Kolya grazes. Mice squeak. Vasya is a baby. Masha fell asleep. Dad is tired. The kid is naughty. The goose hisses. Mice squeak. They write by hand. They cut with a knife. They write with a pen. They wave their hand. They saw with a saw.

19. Write down the sentences, divide the words into syllables. Emphasize the vowels of the second

series.

The cat was sleeping. The dough is kneaded. The tables are standing.

The mouse is gone. The knife is sharpened. The rains are coming.

Martha knocks. The stamps stick. The winds are blowing.

The fish is swimming. The toe hurts. The sun is shining.

20. Write down the text, divide the words into syllables. Underline the vowels. (When copying, require syllable-by-syllable pronunciation of words.)

My mother has a son, Misha. The son is small. Lusha's mom. She is small. Shura washed the frames. The floor is damp. Shura washed the floor. It got dry. Sonya Murka. Sonya gave milk. Murka lapped up milk. Linda is small. Lida has soap. She washed her own hands. This is our garden. Rose in the garden. The rose has a good smell. Rose is good. Vova and Shura were fishing. Vova has a bream. Shura has a pike. Cook, mom, wow. Mom and dad were at home. Dad was reading the newspaper. Mom was reading a book. Masha taught lessons. Roma is small. Mom gave her son soap. Roma himself washed his face and hands. In the hollow of a squirrel. Squirrels have babies. The squirrel drags mushrooms, nuts into the hollow and moss. Winter has come. Snow all around. Children are happy. Lida has a sled. Tanya has skis. Lida drives Kolya. The bird sat on a branch. This is a titmouse. Here is the snowman. The bullfinch hammers a cone. He loves seeds. Theme. Hard and soft consonants.

Sonya Murka. Sonya gave milk. Murka lapped up milk. Linda is small. Lida has soap. She washed her own hands. This is our garden. Rose in the garden. The rose has a good smell. Rose is good. Vova and Shura were fishing. Vova has a bream. Shura has a pike. Cook, mom, wow. Mom and dad were at home. Dad was reading the newspaper. Mom was reading a book. Masha taught lessons. Roma is small. Mom gave her son soap. Roma himself washed his face and hands. In the hollow of a squirrel. Squirrels have babies. The squirrel drags mushrooms, nuts into the hollow and moss. Winter has come. Snow all around. Children are happy. Lida has a sled. Tanya has skis. Lida drives Kolya. The bird sat on a branch. This is a titmouse. Here is the snowman. The bullfinch hammers a cone. He loves seeds. Theme. Hard and soft consonants.

Purpose. To teach students to hear hard and soft sounding consonants.

I. Organizational moment.

II. Hard and soft consonants .

Hard and soft consonants .

A speech therapist invites students to listen to a story about two bears.

Once upon a time there were two bears. One bear was big, the other was small. Both bears loved to sing songs. They sat on a stump and sang. The big bear sang: “Ta-ta-ta”, and the small one: “Tya-ta-ta”.

Remember how the big bear sang and how the little one sang.

The songs are similar, but the bears sang them differently.

How did these songs differ?

(The big bear sang in a rough, firm voice, and the little one sang in a gentle, soft voice.)

Speech therapist. In the big bear's song , the consonant t sounded hard, and in the little bear's song t it sounded soft.

III. Denoting the softness of consonants with a soft sign.

(Soft consonant at the end of a word.)

Task 1. Listen to the word pairs. Compare them for meaning. What is the difference between

these words when writing?

corner - coal spruce - spruce chalk - stranded

brother - take top - swamp chorus - polecat

Task 2. Read the pairs of words. Compare them by spelling,

Read the pairs of words. Compare them by spelling,

angle - coal brother - take chorus - ferret

Speech therapist explains to students: the consonant at the end of the word sounds soft

because it softens the soft sign, and then asks the students:

How to pronounce the consonant at the end of the word , if after it there is a soft sign?

Task 3. Listen to the words. Name a consonant in the word that sounds soft. Explain why this consonant-sounds soft.

steel, dust, goose, fire, chain, salt, true story, bubble, fire

IV. Summary of the lesson.

Speech therapist. How can consonants sound? What influences their mitigation?

⇐ Previous34567812Next ⇒

See also:

How to listen to your interlocutor

Common shooting mistakes in basketball

The adoption of Christianity in Russia and its significance

US media

This page was last modified: 2016-06-26; views: 732; Page copyright infringement; We will help you write your paper!

infopedia. su All materials presented on the site are for informational purposes only and do not pursue commercial purposes or copyright infringement. Feedback - 176.57.188.101 (0.033 p.)

su All materials presented on the site are for informational purposes only and do not pursue commercial purposes or copyright infringement. Feedback - 176.57.188.101 (0.033 p.)

All rules for solfeggio

All rules for solfeggio

The speech therapist pronounces the word raspberries. Pupils count syllables, highlight vowels from each syllable with their voice, determine the number of vowels.

The speech therapist pronounces the word raspberries. Pupils count syllables, highlight vowels from each syllable with their voice, determine the number of vowels.

When performing these exercises, children first slap the rhythmic pattern of the word, correlate it with the word itself. Having learned to highlight the stressed syllable in a word, students can easily find the stressed vowel.

When performing these exercises, children first slap the rhythmic pattern of the word, correlate it with the word itself. Having learned to highlight the stressed syllable in a word, students can easily find the stressed vowel.  Listen and repeat the words, highlight the stressed syllable with your voice, then the stressed vowel. Draw a diagram of the word, mark the stress.

Listen and repeat the words, highlight the stressed syllable with your voice, then the stressed vowel. Draw a diagram of the word, mark the stress.

.. which is carried out or with the help of a mask ...

.. which is carried out or with the help of a mask ...

Say word 9 in chorus0126 syllables. (A diagram is also drawn on the board for a drawing with a squirrel.) Now guess why under the drawings depicting a fox and a squirrel, the same diagrams. (These are schemes of words consisting of two syllables.)

Say word 9 in chorus0126 syllables. (A diagram is also drawn on the board for a drawing with a squirrel.) Now guess why under the drawings depicting a fox and a squirrel, the same diagrams. (These are schemes of words consisting of two syllables.)  You notice that the class is tired, absent-minded, working sluggishly, yawns, little pranks begin: make them sing some song - and everything will come back in order, energy will be revived, and the children will start working as before.

You notice that the class is tired, absent-minded, working sluggishly, yawns, little pranks begin: make them sing some song - and everything will come back in order, energy will be revived, and the children will start working as before.

Count the number of parts of the word in the diagram.)

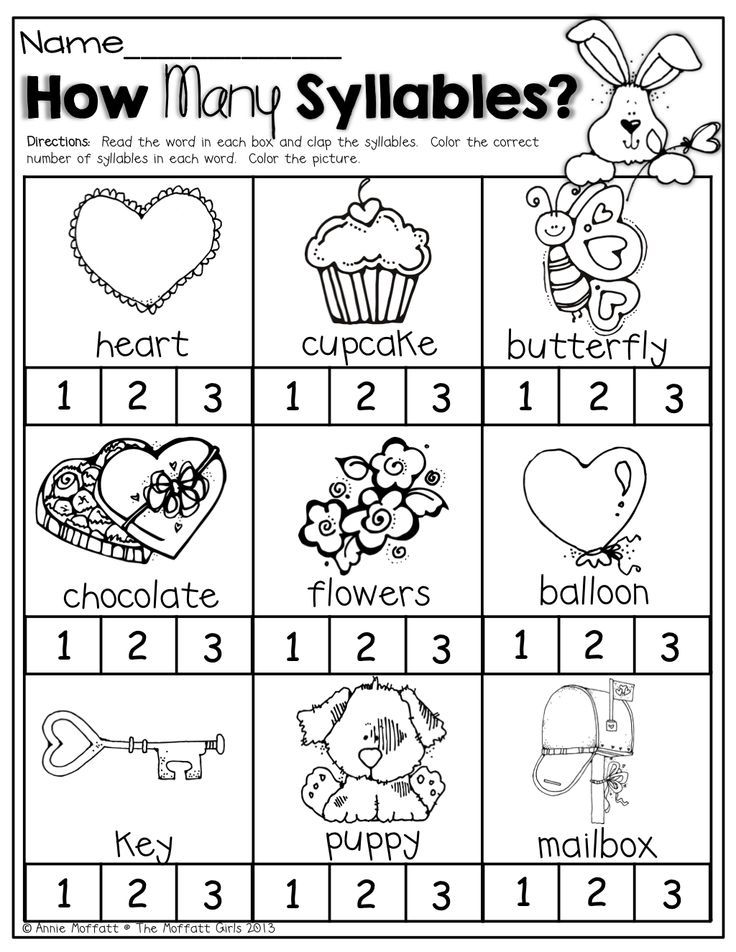

Count the number of parts of the word in the diagram.)  12), students name words consisting of three syllables ( newspaper, picture, car, cubes ), two syllables ( mother, boy, children, grandchildren, hood, cube, book, sock ), one syllable ( son, daughter, grandson, table, chair ) .

12), students name words consisting of three syllables ( newspaper, picture, car, cubes ), two syllables ( mother, boy, children, grandchildren, hood, cube, book, sock ), one syllable ( son, daughter, grandson, table, chair ) .