Kids being helpful

Tips for teaching generosity and kindness

© 2020 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

How do you teach kids to be helpful? To be generous and kind? Studies suggest we should avoid heavy-handed tactics and bribes. Instead, we need to respect — and nurture — our children’s natural inclinations to do good.

Helpful? Generous? Caring? Psychologists call these behaviors “prosocial,” and they are valued in societies throughout the world. Prosocial behavior is the bedrock of morality. It’s the glue that keeps communities strong.

And prosocial behavior is crucial for an individual’s success. Making friends, entering into cooperative projects, building trust and goodwill… all of these things depend on our ability to contribute, help, and share.

No wonder, then, that societies around the world strive to nurture or teach helpfulness. But which approaches are the most effective?

I think it’s crucial to start with an understanding of the psychology of prosocial behavior.

Children–even babies–can be spontaneously kind and helpful. They are prompted by a sense of empathy, and by the good feelings that arise from prosocial acts.

We can try to boost these natural inclinations, but beware. Pressuring children can backfire.

So let’s begin by considering this fundamental evidence, and then take a look at positive steps we can take to nurture helpfulness in children.

Experimental evidence: Children — even babies — can be spontaneously kind and helpful.

Some people believe that babies don’t experience empathy, but that’s wrong. As I explain elsewhere, babies respond to our emotional states.

If we’re stressed out, they become stressed too. If they see that we’re sad or dejected, their faces register sympathetic concern.

If they witness acts of bullying, they show a preference for the victims — and also for individuals who come to the aid of victims.

So yes, babies show signs of empathy — even before they can walk or talk.

And once babies start walking, they can use their motor skills to be helpers. Indeed, babies can recognize other people’s frustrated intentions and respond with a helping hand.

How can we be sure?

At the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Felix Warneken and Michael Tomasello tested 14-month-old babies by presenting them with a stranger experiencing difficulties.

The man was trying to pick up an object beyond his reach. Without even being asked, babies helped him retrieve it, and these kids were fast:

In most cases, the babies responded within 7 seconds—before the man made eye contact or named the object he was after (Warneken and Tomasello 2007).

Experiments on 18-month old babies yielded similar results (Warneken et al 2007). Babies helped a woman retrieve an out-of-reach item (a marking pen) even though they had to cross several obstacles first.

By the preschool years, kids become capable of even more sophisticated forms of aid, like helping a stranger get the attention of another person (Beier et al 2013), and giving people what they really need, instead of what they ask for (Martin and Olsen 2013; Hepach et al 2019).

Experimental evidence: Children help because it feels good.

This is crucial to understand. People like to be helpful. And young children are no different.

Experiments suggest that 22-month-old babies feel happy when they give to others (Aknin et al 2012).

Given a choice between sharing and hoarding, preschoolers show greater happiness when they share (Wu et al 2017).

And by the age of 3 to 6 years, kids are aware that sharing makes them feel good. They anticipate positive feelings, and this prompts them to be generous (Paulus and Moore 2017).

Experimental evidence: Kids are less likely to share if, in the past, adults have pressured them.

A few years back, Nadia Chernyak and Tamar Kushnir (2013) wondered what would happen if children were compelled to give away a prize. Would the experience encourage future generosity, or curtail it?

In experiments on 72 young children, aged 3-5, the researchers gave each child a sticker, and then introduced a sad character (a puppet) who needed cheering up. Some kids were told to give their sticker to the character. Other kids were given a choice.

Some kids were told to give their sticker to the character. Other kids were given a choice.

Later kids were given three stickers, and presented with an opportunity to help yet another depressed creature.

Kids in both groups gave away at least one sticker. But some gave away two or three, and these were primarily the children who’d experienced free choice.

Kids who’d previously been forced to give were only half as likely to donate most of their stickers.

Why does forced sharing make children less likely to share spontaneously? One likely theory is that it disrupts the learning process.

When researchers have pitted spontaneous sharing against forced sharing, they noticed something. Kids don’t experience the same, natural high when they are forced to share (Wu et al 2017).

Thus, forced sharing may prevent kids from learning to associate sharing with positive feelings.

Experimental evidence: Giving kids prizes and toys for helping isn’t such a good idea.

Controlled studies have tested this hypothesis. For example, consider the research on toddlers.

Felix Warneken and Michael Tomasello (2008) assigned 20-month-old toddlers to one of three treatment groups.

- One group was trained to expect a material reward for helping.

- Another group was trained to expect verbal praise.

- The third group received no reward at all.

Next, the toddlers were given the opportunity to help an adult stranger. The outcome?

Compared to the kids in the “verbal praise” and “no reward” conditions, the kids with a history of tangible rewards became less likely to help.

A second experiment on somewhat older children — 3-year-olds — came up with similar results. Little kids end up sharing less after they’ve experienced bribes (Ulber et al 2016).

And there’s evidence regarding school-aged children, too.

In an experiment conducted by Richard Fabes and colleagues, primary school kids (grades 2-5) were offered the chance to sort stacks of colored paper (Fabes et al 1989).

All the kids were told this task would benefit hospitalized children.

In addition, some kids were also told that they would be given a small toy in exchange for helping.

After their initial opportunity to help, kids were given a second chance to work more on the same task. This time, there was no mention of the hospital kids or the material reward. Kids were simply given the change to spontaneously continue their “volunteer work.”

What happened?

The kids who had been given toys for helping were less helpful during the follow-up opportunity. They spent less time sorting paper and got less work done.

Moreover, the results were linked with parenting. Motivation was most undermined among kids whose parents routinely used tangible rewards at home (Fabes et al 1989).

Experimental evidence: Money — and talk about money — turns off the helpful, generous impulse.

As a team of Polish and American researchers explain, there are different modes for satisfying our needs.

One is by dealing with people in the marketplace. We buy and sell our services.

Another is by relating to each other out of a sense of community, friendship, or affection. We don’t help because we anticipate payment. We help because we care.

What happens when our attention turns toward the marketplace mode? The results aren’t good for prosociality. When researchers primed young children to think about money (by having them handle coins), the kids showed less helpfulness and generosity immediately after (Gasiorowska et al 2019).

Here’s what the research suggests.

1. Nurture empathy and “emotional intelligence”

Helpfulness in children is associated with many of the same factors that predict empathy and empathic concern (Eisenberg et al 2006; Brownell et al 2013), and that makes sense: Empathy makes us better at helping. It gives us insights into what other people need.

So check out these Parenting Science tips for nurturing empathy in children and teens.

2. Celebrate spontaneous acts of helpfulness and kindness, but pay attention to guidelines for effective praise.

Praise can be motivating, especially for younger children.

In the experiments mentioned above, praise didn’t have a negative impact on a child’s natural, unforced inclination to share.

And in observational studies, researchers have noticed links between parental praise and prosocial behavior in young children.

Mothers who praises their preschoolers’ good deeds were more likely to have generous, helpful children (Garner 2006; Hastings et al 2007).

Praise may be motivating for older kids, too. But we need to be careful, because older children are more socially-savvy, and capable of analyzing our motives. They may feel we are trying to manipulate them, and that can backfire.

For tips on using praise wisely, see this my article about the science of praise.

3. Make children feel secure — in life, and in their attachment relationships.

Research confirms it: Kids are less likely to offer help, less likely to share, when they feel threatened.

For example, one study of preschoolers found that children were less likely to share a prize if they were insecurely attached to their parents (Paulus et al 2016).

Another study found that securely-attached kids engaged more often in helping, sharing, and comforting others (Beier et al 2019).

And when researchers studied children’s reactions following a natural disaster (a destructive earthquake), they found that the youngest children tended to become less generous (Li et al 2013).

In particular, kids under the age of 6 seemed to retreat into a more self-protective mode. In experiments, kids were less likely to share prizes with a stranger. The effects lasted for up to a year after the disaster.

So kids are more likely to behave prosocially if they feel a sense of security. Help kids develop these feelings by practicing sensitive, responsive parenting, and by coaching kids through difficult emotions.

For more information, see my guide to emotion coaching, and these articles about the benefits of sensitive, responsive parenting:

- Secure attachment relationships protect children from toxic stress

- Oxytocin affects social bonds. Can we influence oxytocin in children?

- Positive parenting tips: Getting better results with humor, empathy, and diplomacy

Studies suggest that cooperative games and activities help kids hone communication skills that are crucial for becoming an effective helper.

For more information, see these Parenting Science articles:

- Social skills activities for children and teens

- Cooperative board games for kids

Aguilar-Pardo D, Martínez-Arias R, and Colmenares F. 2013. The role of inhibition in young children’s altruistic behaviour. Cogn Process. 14(3):301-7.

Aknin LB, Hamlin JK, Dunn EW. 2012. Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS One. 7(6):e39211.

Beier JS, Over H, and Carpenter M. 2013. Young Children Help Others to Achieve Their Social Goals. Dev Psychol. 2013 Aug 12. [Epub ahead of print]

2013. Young Children Help Others to Achieve Their Social Goals. Dev Psychol. 2013 Aug 12. [Epub ahead of print]

Brownell CA, Svetlova M, Anderson R, Nichols SR, and Drummond J. 2013. Socialization of Early Prosocial Behavior: Parents’ Talk about Emotions is Associated with Sharing and Helping in Toddlers. Infancy. 18:91-119

Cameron J, Bank KM, and Pierce WD. 2001 Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. The Behavior Analyst 24: 1-44.

Chernyak N and Kushnir T. 2013. Giving preschoolers choice increases sharing behavior. Psychol Sci. 24(10):1971-9.

Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad T L. 2006. Prosocial development. In W. Damon (ed): Handbook of child psychology, volume 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th edition. New York: Wiley.

Eisenberg N and Fabes RA. 1998. Prosocial development. In W. Damon (ed): Handbook of child psychology, volume 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th edition. New York: Wiley.

New York: Wiley.

Fabes RA, Fulse J, Eisenberg N, et al. 1989. Effects of rewards on children’s prosocial motivation: A socialization study. Developmental Psychology 25: 509-515.

Garner PW. 2006. Prediction of prosocial and emotional competence from maternal behavior in African American preschoolers. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 12(2):179-98.

Gasiorowska A, Chaplin LN, Zaleskiewicz T, Wygrab S, Vohs KD. 2016. Money Cues Increase Agency and Decrease Prosociality Among Children: Early Signs of Market-Mode Behaviors. Psychol Sci. 27(3):331-44.

Hastings PD, McShane KE, Parker R, and Ladha F. 2007. Ready to make nice: parental socialization of young sons’ and daughters’ prosocial behaviors with peers. J Genet Psychol. 168(2):177-200.

Hepach R, Benziad L, Tomasello M. 2019. Chimpanzees help others with what they want; children help them with what they need. Dev Sci. 2019 Nov 11:e12922. Epub ahead of print: https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12922.

Hepach R, Vaish A, and Tomasello M. 2012. Young children are intrinsically motivated to see others helped. Psychol Sci. 23(9):967-72.

2012. Young children are intrinsically motivated to see others helped. Psychol Sci. 23(9):967-72.

Hepach R, Vaish A, and Tomasello M. 2013. Young children sympathize less in response to unjustified emotional distress. Dev Psychol. 49(6):1132-8.

Leimgruber KL, Shaw A, Santos LR, Olson KR. 2012. Young children are more generous when others are aware of their actions. PLoS One. 7(10):e48292.

Li Y, Li H, Decety J, Lee K. 2013. Experiencing a natural disaster alters children’s altruistic giving. Psychol Sci. 24(9):1686-95.

Martin A and Olson KR. 2013. When kids know better: paternalistic helping in 3-year-old children. Dev Psychol. 49(11):2071-81.

Paulus M and Moore C. 2017. Preschoolers’ generosity increases with understanding of the affective benefits of sharing. Dev Sci. 20(3).

Roth-Hanania R, Davidov M, Zahn-Waxler C. 2011. Empathy development from 8 to 16 months: early signs of concern for others. Infant Behav Dev. 2011 Jun;34(3):447-58

Svetlova M, Nichols SR, Brownell CA. 2010. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: from instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Dev. 81(6):1814-27.

2010. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: from instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Dev. 81(6):1814-27.

Ulber J, Hamann K, Tomasello M. 2016. Extrinsic Rewards Diminish Costly Sharing in 3-Year-Olds. Child Dev. 87(4):1192-203.

Vaish A, Carpenter M, and Tomasello M. 2010. Young children selectively avoid helping people with harmful intentions. Child Dev. 81(6):1661-9.

Warneken F and Tomasello M. 2013. The emergence of contingent reciprocity in young children. J Exp Child Psychol. 2013 Oct;116(2):338-50.

Warneken F and Tomasello M. 2008. Extrinsic rewards undermine altruistic tendencies in 20-month-olds. Developmental Psychology 44(6): 1785 – 1788.

Warneken, F, Hare, B, Melis, AP, Hanus D, and Tomasello, M. 2007. Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLoS Biology 5 (7): 1414 – 1420.

Warneken F and Tomasello M. 2007. Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy 11(3): 271–294.

Wu Z, Zhang Z, Guo R, Gros-Louis J. 2017. Motivation Counts: Autonomous But Not Obligated Sharing Promotes Happiness in Preschoolers. Front Psychol. 8:867.

2017. Motivation Counts: Autonomous But Not Obligated Sharing Promotes Happiness in Preschoolers. Front Psychol. 8:867.

Image credits for “Raising helpful kids: Tips for teaching kindness and generosity”

Title image of boys rollerskating by Pahis / istock

image of girl helping boy on scooter by monkeybusinessimages / istock

image of girl holding coins by jeancliclac / istock

This article includes some brief portions of text from a previously-published Parenting Science article, “Raising helpful kids: The perils of rewarding good behavior.”

Content last modified 5/2020

How to Teach Kids to Be Helpful

I was at my son’s school to check him out early for an appointment. While I waited for him, the school secretary commented on what a nice, helpful kid my son is.

“Really?” I replied, hoping she would say more.

“Oh yes, just the other day, it was raining and several girls forgot their umbrellas. Your son took his jacket off and held it over their heads while they were waiting in the carpool line so they wouldn’t get wet!” she said.

Your son took his jacket off and held it over their heads while they were waiting in the carpool line so they wouldn’t get wet!” she said.

Smiling, I thanked her for the compliment, but I wasn’t surprised. I could picture my son doing that!

That’s when I realized his actions at school were the actualization of a lifetime of lessons that family, friends and teachers have gifted to my son. We’ve worked hard to teach him to be helpful through conscious attention to teaching helpfulness as a skill.

Teaching kids behaviors like helpfulness is an endeavor that starts when they are babies and continues until they leave home, and it’s influenced by everyone our kids come in contact with. I suppose you have heard the saying “It takes a village”? How true that saying is!

That’s why it’s important to expose our kids to the people that will be the best role models. To give them age-appropriate toys and entertainment that aligns with your family’s values. To know who their friends are and the ideas they are being exposed to. And to give them the best education we can find.

And to give them the best education we can find.

Helpfulness is a wonderful character trait to teach our children. I’ve read that kids are like sponges; they soak up everything! You see, learning doesn’t start on the first day of school. Learning starts the day they are born!

Here are some ideas I’ve found invaluable in learning how to teach kids to be helpful at any age!

To be the positive parent you’ve always wanted to be, click here to get our FREE mini-course How to Be a Positive Parent.

BabiesBabies take in all the information they know by hearing and seeing. As parents, we are the first teachers. That’s an honor and privilege to be certain! What we say and how we say it matters from day one.

Babies will sense your mood, listen to the sound of your voice and pick up on your facial cues. When you are calm, your baby will be calmer. If you talk in a calm, soothing voice, your baby will become quieter. When you smile, they will smile back. Your mood will influence their mood. “Children frequently hear more in the tone of voice than in the words we use” as noted by Rudolf Dreikurs, M.D. in his classic book Children the Challenge.

When you smile, they will smile back. Your mood will influence their mood. “Children frequently hear more in the tone of voice than in the words we use” as noted by Rudolf Dreikurs, M.D. in his classic book Children the Challenge.

Your behavior, attitude and demeanor will first be observed and later mimicked as babies learn about the world around them through their first interactions with their parents and caregivers.

They will hear every “please” and “thank you” that you say. When they start to talk, they will mimic what they have heard. Most importantly, what you say and how you say it will be their first lessons in learning to be helpful themselves later on.

Likewise, bad language and angry inflection will be mimicked when babies start to talk. When my son was very young he repeated a couple of bad words he overheard. Instead of ignoring it or finding it funny and laughing, we sprang into action each and every time he uttered an “off-limits” word. Gentle reinforcement and explaining which words we do not say a few times was all it took for him to get the message that we have boundaries in our family. Besides, now he holds me accountable for my occasional slips!

Gentle reinforcement and explaining which words we do not say a few times was all it took for him to get the message that we have boundaries in our family. Besides, now he holds me accountable for my occasional slips!

Toddlers take in the world by touching, doing and asking WHY? Why? Why?

Let that question be music to your ears. Here is WHY: Why is the greatest question in the world.

Wanting to know why is the spark that starts kids on the path to learning and wanting to learn more! The smartest people in the room are those who asked why the most in school.

I read an interesting article in LIVESCIENCE called Why Kids Ask Why, which explains how important answering the why questions at this age matters.

According to this article, a new study of toddlers aged 2 to 5 suggests they are more active about gathering knowledge at this age than previously thought. This is the perfect time to give them good answers which help enforce important character concepts like teaching kindness.

So, challenge yourself to push aside the annoyance when you feel like you can’t answer one more WHY to find real and meaningful answers.

For example:

- When you buy those delicious Girl Scout Cookies they have asked for, explain that buying those cookies helps the girls selling them earn money for their club.

- As kids pick up their toys and put them away, tell them “Thank you for helping keep the house clean.”

- When you put the trash in the trash can, explain that you are helping the trash collectors do their jobs and helping the earth by keeping it clean.

- If someone holds a door open for you, remember to say “Thank you for helping me,” or “That’s so kind of you.”

Continue to illustrate helpfulness in your language and actions. Your kid(s) are looking, listening and learning!

School-Age ChildrenSchool-age children want to be involved! Start encouraging them to find ways to help others. Focus on actions that stimulate creativity, give them a sense of fun and get them involved in active ways.

Focus on actions that stimulate creativity, give them a sense of fun and get them involved in active ways.

Encouragement is one of the most important aspects of child rearing, according to the authors of Children the Challenge. They go on to note that the lack of proper encouragement can be “considered the basic cause for misbehavior.” Encouragement is THAT important!

Here are some examples:

- Do your kids like to draw? Most kids do! Encourage them to make a get-well card for a sick friend or family member.

- Do you have a family pet? Give them the responsibility of feeding and walking the family dog, or brushing the cat’s fur. Teach them that it helps the pet stay healthy and happy.

- Do you recycle? Teach your school age children how recycling helps the planet. Make them in charge of filling up your recycle bins (just make sure what they put into them is meant to be thrown out!).

- Give them small jobs to do around the house and praise them for helping without complaining.

Resist giving bribes or allowances for being helpful. Helping comes from the heart!

Resist giving bribes or allowances for being helpful. Helping comes from the heart!

Bribing children for acting a certain way or co-operating with what we want them to do may work in the short term but eventually fails because it teaches the child to comply only when they get rewarded.

As noted in Children the Challenge: “Children don’t need to be bribed to be good. They actually want to be good.” So encourage the behavior you want to see and keep reinforcing it with thanks and praise.

Often kids only need a little encouragement to learn to help others in small ways. The lesson they will be learning is BIG: every way of helping matters.

Big or small, every kindness counts. Kids love feeling big and important because they spend a lot of time in their day feeling like they don’t know enough or aren’t old enough yet to do what they want to do. Let them know they are not too small to help out!

Preteen and TeenPreteens and teens want to become more independent and start to make decisions on their own. Christine Carter Ph.D., writing for Psychology Today.com, explains that “once kids reach adolescence, they need to start managing their own lives.”

Christine Carter Ph.D., writing for Psychology Today.com, explains that “once kids reach adolescence, they need to start managing their own lives.”

Here, too, is an opportunity for you to mentor their skills of helpfulness while encouraging interests in areas which will help ease them into more independence.

Does your teen have a special hobby or interest you can share and explore together? As a preteen, my son expressed an interest in space. We joined the National Space Society and started attending meetings. Many nonprofit organizations, like this one, need volunteers to help during community events. In no time my son started to volunteer for this organization because it was fun and his contribution was so appreciated.

Volunteering is the perfect way to help kids learn the lessons of civic duty and find ways they can impact their community. It takes the lessons of being a helpful person outside the family and out into the bigger, wider world!

Now that my son is older, he has chosen other organizations to volunteer with independent of us.

Check out some of the nonprofit organizations in your area to see at what age they will accept volunteers. You will be surprised that many will allow teens to help out.

Here are just a few examples:

- Pet shelters need donations of food and toys but also volunteers to come spend time with the animals.

- If you attend a church, temple, or other place of worship, there are endless ways for teens to help out, from serving snacks, to teaching summer camps for younger kids, to going on mission trips.

- Summer programs are always looking for responsible teen volunteers as are museums and zoos. My son volunteers as a teacher’s aide at the summer camp he attended when he was younger. His spirit of helpfulness actually impressed the staff so much they asked him to return when he outgrew the program!

Besides the feeling of goodwill your teen or preteen will get from doing volunteer work, other benefits may be the hours they serve counting toward National Honor Society requirements or service hours required by their school.

These are just a few examples that illustrate ways you can teach your child the value of being helpful at every age.

Being a person who is giving and helpful can be easy, fun and rewarding, whether it’s in the service of a friend, family member, animals, your local community or the planet!

Grown-Ups Have a Role Too!Encourage kids everyday by modeling the behavior you want them to learn. Kids will quickly see through you if you talk about being helpful but don’t show them that it’s a priority in your own life.

- Common courtesies count: Remember to say please and thank you!

- Teach by example: Try to hold your tongue when someone cuts you off in traffic or cuts to the front of the line. Use these opportunities to teach your kids calmness and kindness to others.

- Encourage kindness while going about your daily business: Open doors for others, return shopping carts to stores and even loan people your umbrella when it’s raining.

- Take an active role when mentoring older kids until they are independent enough to go solo.

Love this article? Receive others just like it once per week directly in your mailbox. Click here to join us… we’ll even get you started with our FREE mini-course How to Be a Positive Parent.

The 2-Minute Action Plan for Fine ParentsFor our quick contemplation questions today, please ask yourself:

- How often do I respond helpfully when my kids ask why?

- How often do I encourage my kids to get involved and help others?

- Who could I ask to learn more about organizations where my kids and I could volunteer?

Hopefully these ideas will help you find unique ways to keep engaging your kid(s) to look for ways to be helpful, big or small!

The Ongoing Action Plan for Fine ParentsGet the whole family involved in ways to teach helpfulness.

Take advantage of the time the whole family has together during holiday breaks and summer vacation. Plan some family events that include volunteering for good causes in your community:

Plan some family events that include volunteering for good causes in your community:

- Help at a food pantry or serve lunch at a soup kitchen.

- Spend an afternoon at the mall during the holiday season selecting gifts for others that can be donated at a charity in need.

- Plant a tree together on Earth Day because we all need to show the Earth more kindness too!

- Join a club and go to meetings together. Volunteer on the Board of Directors at the club, and your teen will start learning leadership skills and how to be helpful as you model it for them.

- Encourage your preteen or teen to volunteer at clubs and causes they choose on their own at school or in the community, and clear away obstacles they may have like transportation or funding.

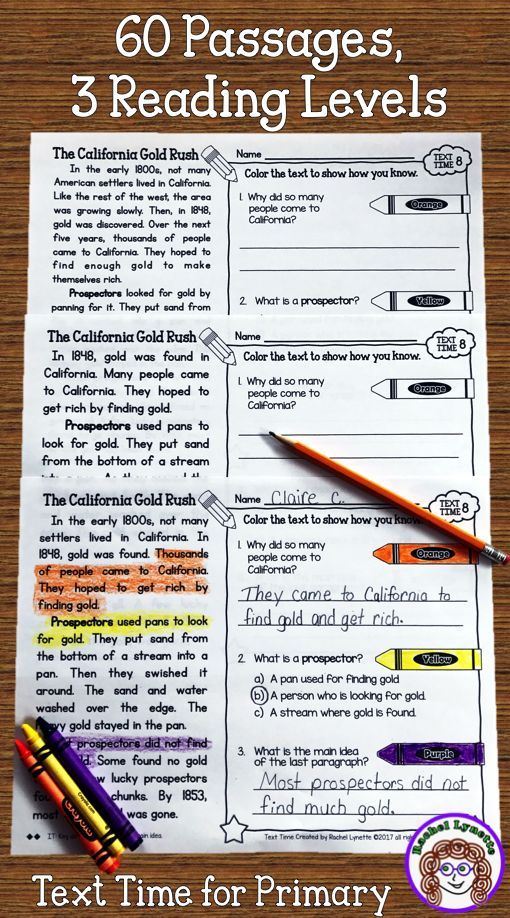

Should children help their parents ? Many parents believe that it is not worth burdening children with household chores . They think that housework will rob children of the carefree childhood that comes only once. Often, parents who come to a psychologist for a consultation believe that schooling is enough for their children and, apart from that, they do not need anything from children.

They think that housework will rob children of the carefree childhood that comes only once. Often, parents who come to a psychologist for a consultation believe that schooling is enough for their children and, apart from that, they do not need anything from children.

However, as a family psychologist, the author of this note Olga Tseytlin believes that it is much more important that when children help their parents by performing household chores , they will feel needed in the family, able to contribute their own own contribution to family well-being and therefore be its full members.

In counseling, she helps parents understand that by teaching children responsibility for household chores, we develop their social interest and prepare them to not be afraid of responsibility outside the home.

children who help their parents and have their own household chores tend to do better in school because they interact better with teachers. Without such preparation, children become consumers and in the future only want to receive something from other people. They just sit at home and wait for someone to come and give them what they want. Sometimes these children get the feeling that they are something of themselves only when someone serves them.

Without such preparation, children become consumers and in the future only want to receive something from other people. They just sit at home and wait for someone to come and give them what they want. Sometimes these children get the feeling that they are something of themselves only when someone serves them.

Based on their experience and life situations, adults can come up with a lot of different things that a child can do for the benefit of the family. But sometimes parents are at a loss, not knowing what can be entrusted to children, so the author further gives approximate lists of household chores for children of different ages, which were taken with slight changes in the book by B. B. Grunwald, G. V. Macaby "Family Counseling" . So than children help around the house at different ages:

Three-year-old household chores

Gather and put toys in the appropriate place.

Put books and magazines on the shelf.

Take napkins, plates and cutlery to the table.

Clean up leftover crumbs after eating.

Clear your seat at the table.

Brush teeth, wash and dry hands and face, comb hair.

Undress yourself, with a little help get dressed.

Wipe away traces of "childish surprise".

Carry small items to the desired shelf, put items on the bottom shelf.

Household chores for a four year old

Set the table, including good plates.

Help put away groceries.

Under the supervision of a parent, help in buying cereals, pasta, sugar, biscuits, sweets, bread.

Feed pets on a schedule.

Help clean the garden and yard in the country house.

Help make and make the bed.

Help wash dishes or help load the dishwasher.

Wipe dust.

Spread butter on bread. Prepare cold breakfasts (cereals, milk, juice, crackers).

Help prepare a simple dessert (put decoration on cake, add jam to ice cream).

Share toys with friends.

Retrieve mail from a mailbox.

Play at home without constant supervision and without constant adult attention.

Hang socks and handkerchiefs to dry.

Help folding towels.

Five-year-old household chores

Help plan meals and groceries.

Make your own sandwiches or a simple breakfast and clean up after yourself.

Pour yourself a drink.

Serve a dinner table.

Pick lettuce and herbs from the garden.

Add certain ingredients to the recipe.

Make and tidy the bed, clean the room.

To dress and put away clothes independently.

Clean sink, toilet and tub.

Wipe mirrors.

Sort laundry for washing. Fold white separately, color separately.

Fold and put away clean laundry.

Answer phone calls.

Help clean the apartment.

Pay for small purchases.

Help wash the car.

Help take out the trash.

Decide for yourself how to spend your part of the family entertainment money.

Feed and clean up after your pet.

Tie your own shoelaces.

Household chores for a six-year-old (1st grade)

Pick your own clothes for the weather or occasion.

Vacuum the carpet.

Watering flowers and plants.

Peel vegetables.

Prepare simple meals (hot sandwiches, boiled eggs).

Packing for school.

Help hang laundry on the clothesline.

Hang your clothes in a wardrobe.

Gather firewood.

Rake dry leaves, weeds.

Walk pets.

Be responsible for your minor injuries.

Take out the trash.

Tidy up the cutlery drawer.

Set the table.

Household duties of a seven-year-old child (second grade)

Lubricate the bike, take care of it. Lock it in a dedicated place when not in use.

Receive telephone messages and record them.

Be on parcels with parents.

Wash the dog or cat.

Train pets.

Carry grocery bags.

Get up in the morning and go to bed in the evening without being reminded.

Be polite and courteous to other people.

Leave the bathroom and toilet in order.

Iron simple items.

Household chores for an eight- and nine-year-old child (third grade)

Correctly fold napkins and arrange cutlery.

Wash the floor.

Help to rearrange furniture, plan furniture arrangement with adults.

Fill your own bath.

Help others (if asked) in work.

Organize your cupboards and drawers.

Buy clothes and shoes for yourself with the help of your parents, choose clothes and shoes.

Change school clothes for clean ones without being reminded.

Fold blankets.

Sew on buttons.

Stitch open seams.

Clean the pantry.

Clean up after animals.

Get acquainted with recipes for preparing simple dishes and learn how to cook them.

Cut flowers and prepare a vase for bouquets.

Gather fruits from trees.

Light a fire. Prepare everything you need for cooking on a fire.

Painting a fence or shelves.

Write simple letters.

Write thank you cards.

Feed the baby.

Bathe younger sisters or brothers.

Polish the furniture in the living room.

Nine- and ten-year-old household chores (fourth grade)

Change bedding and put dirty laundry in a basket.

Know how to operate a washer and dryer.

Measure out laundry detergent and fabric softener.

Buy groceries from a list.

Cross the street independently.

Come to appointments on your own if you can walk or cycle there.

Bake biscuits from semi-finished products in boxes.

Prepare meals for the family.

Receive and reply to your mail.

Prepare tea, coffee or juice, pour into cups.

Visiting.

Plan your birthday or other holidays.

Be able to provide basic first aid.

Wash the family car.

Learn frugality and economy.

Ten- and eleven-year-old household chores (fifth grade)

Earn money on your own.

Do not be afraid to stay at home alone.

Manage some amount of money responsibly.

Be able to ride a bus.

Responsible for personal hobbies.

Eleven and twelve year old household chores (sixth grade)

Be able to take on leadership responsibilities outside the home.

Help put little brothers and sisters to bed.

Do your own business.

Mowing the lawn.

Help father with construction, crafts and household chores.

Clean stove and oven.

Independently allocate time for study sessions.

Home duties for high school students

On school days, going to bed at a certain time (as agreed with parents).

Take charge of cooking for the whole family.

Have an idea of a healthy lifestyle: eat healthy food, maintain a healthy weight, get regular medical check-ups.

Anticipate the needs of others and take appropriate action.

Have a realistic understanding of possibilities and limits.

Consistently implement the decisions made.

Show mutual respect, loyalty and honesty in all respects.

Earn some money if possible.

Do not ask children to do anything. Just once discuss what they could take on and assign them their responsibilities. You don't have to become a drill sergeant among recruits, but at the end of the day you are the boss.

Do not force children to do things under duress. Remember that part of their work is based on trust. Tell them what needs to be done and let them know how confident you are that they can do it. When they feel that they really help, it is very interesting to watch them.

Many people have a schedule hanging in the kitchen that lists all the daily chores of the children. It indicates the days of the week and the tasks that children must complete on that day. This chart helps a lot by guiding the kids and they don't need to be reminded of anything. They can look at the schedule at any time and see what they have to do. Yes, it's not exactly a perfect scheme, but the schedule definitely helps.

This chart helps a lot by guiding the kids and they don't need to be reminded of anything. They can look at the schedule at any time and see what they have to do. Yes, it's not exactly a perfect scheme, but the schedule definitely helps.

How Children Help Us Grow Up - Child Development

We often wonder how we can raise our children to reach their full potential. But much less often do we ask ourselves the question of how our children help us grow up. After all, even as adults, we are still growing and developing!

Let's face it, our children can evoke emotions in us that we didn't know we had until we became parents. We may encounter a child's tantrum; see how he perceives all our requests with hostility or does not want to take responsibility for the situations that happen to him. It is in such cases that we see ourselves in our children. And, if we know how to treat ourselves with compassion, then we can treat the child from the position of an adult and help him cope with certain situations.

You can also look at how children develop us from the other side: children help our inner child to manifest itself. This wording may seem strange, but the inner child is simply our inner emotional state associated with our childhood experiences. Each of us has a childish part of the psyche that contains different emotions - from sadness to joy and surprise. The inner child can manifest itself in adult life in various situations. For example, if in childhood we experienced negative emotions due to the fact that our words were not listened to, then in similar situations in adult life we also get upset more than we should. And, as if by an irony of nature, our inner child is most powerful when we raise our children.

If you wish, it is easy to find the childish part in your psyche. Try to remember a difficult moment when you overreacted to some situation with your child. Notice that even the thought of this situation triggers emotional and bodily reactions in you. It is in these situations that the child helps you to discover your childish part of the psyche.

For example, imagine that your child is rude to you. You get frustrated and even angry with him. At this point, you may be thinking, "I reacted correctly." But, on the other hand, keep in mind that your disappointment is not only caused by the current situation, but its roots stretch from your childhood.

You might object, “But the child is also behaving badly.” Of course, you need to work correctly with this behavior, in particular, with its causes. However, it is equally important to grow up yourself. As our psyche matures, we understand more clearly how our children should be raised.

Needless to say, parents should not show any emotional reactions when raising children. It's just not possible. Emotions are bright colors in our lives, and they are not going anywhere. However, we can relate to ourselves and our emotions in different ways.

But how do we become mentally mature? Let's take a look at a few key tips for this.

1. Be curious and observe yourself. Ask yourself in different situations: "How is my emotional reaction related to the childish part of my psyche?" This question will help you disengage from thoughts about the situation and pay attention to bodily sensations. Like our children, the children's part of the psyche requires our attention, protection and care. Our attentiveness to the child part of the psyche means a lot for our emotional well-being.

Ask yourself in different situations: "How is my emotional reaction related to the childish part of my psyche?" This question will help you disengage from thoughts about the situation and pay attention to bodily sensations. Like our children, the children's part of the psyche requires our attention, protection and care. Our attentiveness to the child part of the psyche means a lot for our emotional well-being.

2. Expect mental resistance. The first reaction of a person is often a reluctance to explore his own emotions and avoid contact with the childish part of his psyche. We find it difficult to accept parts of ourselves that we do not accept in our children. For example, if we do not recognize some vulnerable points in ourselves, we are unlikely to accept them in our children.

3. Remember that your love for children will motivate you to grow up. It is out of love for children that we strive to be more restrained in our emotional reactions and to do more for our children.