Learn while playing

Minds On! Learning Through Play Promotes STEM

Aug 28 2018

Authors: Jennifer M. Zosh

Blog

Early Childhood Education Family Engagement

In this blog, Jennifer Zosh describes the power of playful learning in promoting STEM.

It is hard to imagine, but that little one in front of you with a bowl full of spaghetti poured over his head might be tomorrow’s leading biologist. Or your little girl, who just cannot seem to figure out how potty training works, may be the woman who designs the world’s largest skyscraper in 2058. The truth is that the building blocks for STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) start early—even in infancy and early childhood. On the one hand, this is great news! This means that children literally have their entire lives to develop the kinds of thinking that will help them to excel in all disciplines in the future (including STEM).

But this also raises an all-too-important question: What kinds of experiences today can help build the thinking we want tomorrow?

The truth is that the answer is not nearly as complicated as you may think. Recently, I worked with a team of international collaborators and the LEGO Foundation to review the literature about how children learn and to highlight principles that guide learning. Guess what? The principles that guide learning are the same ones that we find during high-quality play. The play that happens in your living room, in the car, during story time at the library, and even in line at the supermarket is the kind that can help build better brains and more successful adults, and that can help transform today’s spaghetti monster and potty-training-challenged children into tomorrow’s STEM leaders.

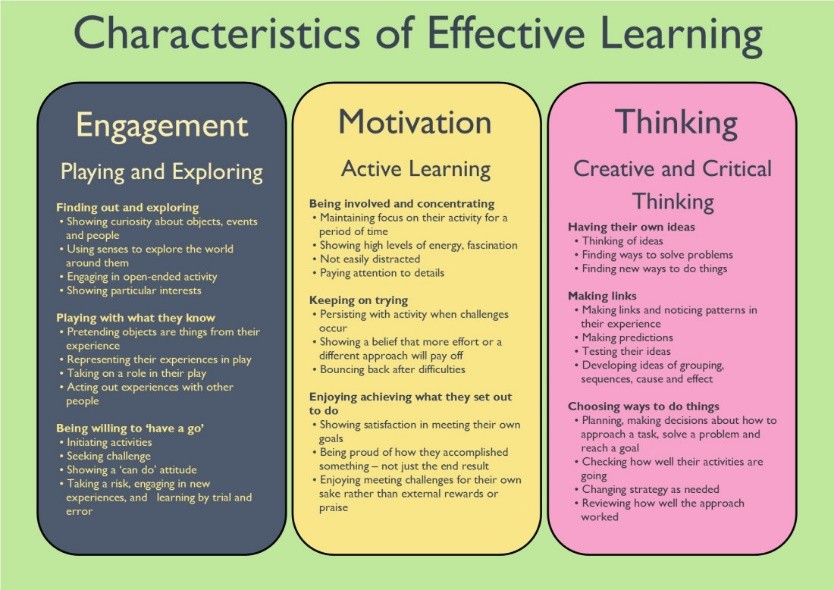

This work suggests that play is particularly powerful for learning because it naturally harnesses the following characteristics that support learning:

- Joyful! Remember the story line of the movie you watched right after a dramatic breakup? No? This is not surprising.

Emotions are linked to learning, and joy seems to help promote learning. Now, think of the kind of joy your child feels when immersed in play. You know, the kind of play that you hate to stop because your child is just SO into pretending to be an archaeologist in the backyard. This type of joy seems to help support learning, so by promoting children’s learning during play, you can help them to master dinosaur names more easily in the backyard while they dig in dirt than you can by sitting around with flash cards.

Emotions are linked to learning, and joy seems to help promote learning. Now, think of the kind of joy your child feels when immersed in play. You know, the kind of play that you hate to stop because your child is just SO into pretending to be an archaeologist in the backyard. This type of joy seems to help support learning, so by promoting children’s learning during play, you can help them to master dinosaur names more easily in the backyard while they dig in dirt than you can by sitting around with flash cards.

- Active (minds on)! You know how time just flies when your brain is engaged in thinking about something? Do you remember the thrill of putting in the last puzzle piece? Research suggests (perhaps unsurprisingly) that children learn more when they have to figure something out for themselves or are “minds on” rather than when they are sitting passively and just listening to new information. Supporting the thrill of active discovery is key!

- Engaged (not distracted)! Remember when the fire alarm would go off in school and you had to go outside for 15 minutes and then return to class? Do you recall the feeling of complete disorientation when you came back inside? Most of the time, you could barely remember what you were even studying! Young children seem to be especially susceptible to distraction, so part of what you can do is help to eliminate some of it.

Even things like background TV or “fun” features of apps have been shown to distract children. Try to eliminate outside diversions to help your child learn.

Even things like background TV or “fun” features of apps have been shown to distract children. Try to eliminate outside diversions to help your child learn.

- Meaningful! What do you think your child would be more interested in building: a random house made out of bricks or a castle that can hold a magical dinosaur? And what is it that you want your child to know—that the triangle in front of him in the app you just purchased is called a triangle or the ability to see triangles, of all different sizes and forms, out in the real world? One of the things that the Science of Learning suggests is that children will: a) be more motivated and b) learn more from contexts that are meaningful to them. This means that drilling with flash cards is much less effective than learning from the real world around us! Learning is not something that happens just at school or in “educational” settings—it happens everywhere!

- Socially interactive! People are likely the best resources for children.

You can help your child by following her interests and supporting (NOT leading) playful interactions. If your child is into animals, support that love and find books that talk about different animals. Relate the animals in the books to the ones you saw in the zoo last summer. No app can do that.

You can help your child by following her interests and supporting (NOT leading) playful interactions. If your child is into animals, support that love and find books that talk about different animals. Relate the animals in the books to the ones you saw in the zoo last summer. No app can do that.

- Iterative! You know how when your little one was in her high chair and she just kept dropping her fork over the side of the tray. Over. And over. And over again? While frustrating for you, this kind of activity is actually the beginning of thinking like a scientist. What will happen this time? What about this time? All parents know that repetition seems to be your toddler’s best friend, but sometimes this repetition and the slight changes your child makes is her experimenting. This kind of thinking, where we take what we know and we learn more by trial and error, is the foundation of STEM thinking.

Don’t read this list and think that children’s experiences must exhibit all of the characteristics 24/7. Instead, think about how play naturally brings the attributes out, and take comfort in the fact that if you support your children’s play, you are helping them to become tomorrow’s leaders (whether they go into STEM fields or not).

Instead, think about how play naturally brings the attributes out, and take comfort in the fact that if you support your children’s play, you are helping them to become tomorrow’s leaders (whether they go into STEM fields or not).

LearningThroughPlay

Jennifer M. Zosh, Emily J. Hopkins, Hanne Jensen, Claire Liu, Dave Neale, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, S. Lynneth Solis and David Whitebread

Learning through play: a review of the evidence

| Jennifer M. Zosh, Ph.D., is an associate professor of Human Development and Family Studies at Penn State University’s Brandywine campus. She is also the director of the Brandywine Child Development Lab where she studies how infants and young children learn about the world around. |

This update is part of a four-part series on family engagement in STEM learning. Join the conversation by sharing this blog with your networks using #FamilySTEM.

Join the conversation by sharing this blog with your networks using #FamilySTEM.

Share Blog on Twitter

Related STEM Series Resource

To learn more about how to support families' STEM learning, check out this video highlighting GFRP's research on family engagement in STEM.

Play-Based Learning: What It Is and Why It Should Be a Part of Every Classroom

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

Renowned psychologist and child development theorist Jean Piaget was quoted in his later years as saying “Our real problem is – what is the goal of education? Are we forming children that are only capable of learning what is already known? Or should we try developing creative and innovative minds, capable of discovery from the preschool age on, throughout life?”

No doubt, Piaget didn’t have to deal with standardized assessment—and he would be at odds with those officials who prioritize test high scores and good grades as the primary goals of education. Instead, Piaget would advocate for helping students understand learning as a lifelong process of discovery and joy. Why do we question the value of this approach?

Instead, Piaget would advocate for helping students understand learning as a lifelong process of discovery and joy. Why do we question the value of this approach?

Being a kid is critical. We see the signature of early childhood experience literally in people’s bodies: as this study from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child shows, positive early experiences lead to longer life expectancy, better overall health, and improved ability to manage stress. Plus, long-term social emotional capabilities are more robust when children have a chance to learn through play; form deep relationships; and when their developing brains are given the chance to grow in a nurturing, language-rich, and relatively unhurried environment.

This is something that as educators we understand in our souls but often find it difficult to implement given the restraints and restrictions of the modern classroom and accountability environment. But, it’s critical to address this disconnect directly in order to make progress. So, let’s talk about why students need play and how we can bring it into our own classrooms—even if we have to sneak it in, and even if we are working with kids who are not so little anymore.

So, let’s talk about why students need play and how we can bring it into our own classrooms—even if we have to sneak it in, and even if we are working with kids who are not so little anymore.

Play is the defining feature of human development: the impulse is hardwired into us and can’t be suppressed. It’s crucial that we recognize that while the play impulse is one thing, understanding the nuts and bolts of actually playing is not always so natural, and may require careful cultivation.

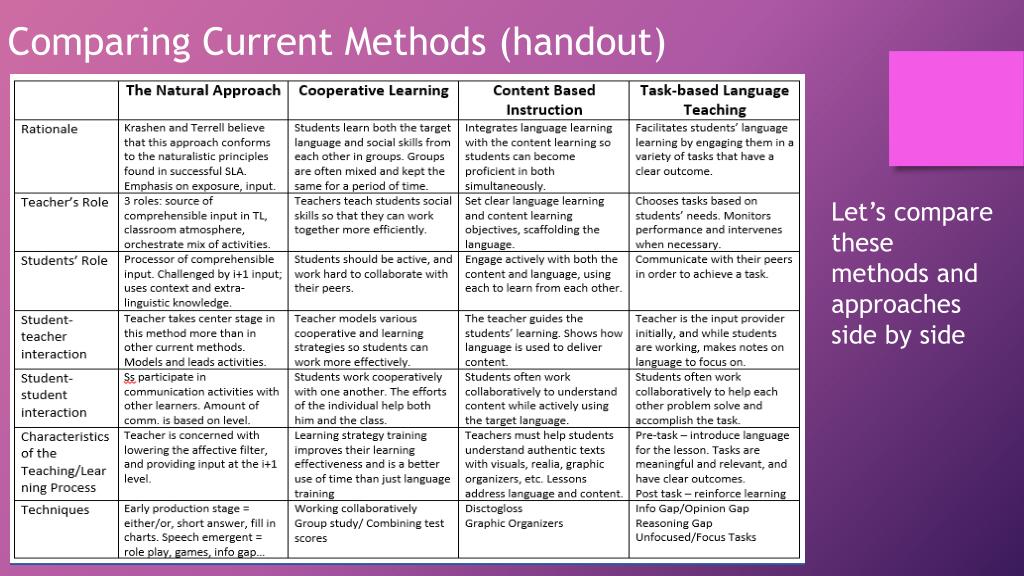

That’s why a play-based approach involves both child-initiated and teacher-supported learning. The teacher encourages children’s learning and inquiry through interactions that aim to stretch their thinking to higher levels. There are other foundational thinkers who have built from Piaget’s theories that support this; educators like Montessori and Stanley Greenspan have recognized that the way to teach a child is through their own interests and developed concrete strategies to do so.

For example, while children are playing with blocks, a teacher can pose questions that encourage problem solving, prediction, and hypothesizing. The teacher can also bring the child’s awareness towards mathematics, science, and literacy concepts. How tall can this get? How many blocks do you need? Can you BLOW the house down? Who else does that? These simple questions elevate the simple stacking of blocks to application of learning. Through play like this, children can develop social and cognitive skills, mature emotionally, and gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

Understanding the Value of PlayWhen children engage in real‐life and imaginary activities, play can challenge children’s thinking.

Children learn best through first-hand experiences—play motivates, stimulates and supports children in their development of skills, concepts, language acquisition, communication skills, and concentration. During play, children use all of their senses, must convey their thoughts and emotions, explore their environment, and connect what they already know with new knowledge, skills and attitudes.

During play, children use all of their senses, must convey their thoughts and emotions, explore their environment, and connect what they already know with new knowledge, skills and attitudes.

It is in the context of play that children test out new knowledge and theories. They reenact experiences to solidify understanding. And it is here where children first learn and express symbolic thought, a necessary precursor to literacy. Play is the earliest form of storytelling. And, it is how children learn how to negotiate with peers, problem-solve, and improvise.

It is in play that basic social skills—like sharing and taking turns—are learned and practiced. Children also bring their own language, customs, and culture into play. As an added benefit, they learn about their peers’ in the process.

Involvement in play stimulates a child’s drive for exploration and discovery. This motivates the child to gain mastery over their environment, promoting focus and concentration. It also enables the child to engage in the flexible and higher-level thinking processes deemed essential for the 21st century learner. These include inquiry processes of problem solving, analyzing, evaluating, applying knowledge and creativity.

These include inquiry processes of problem solving, analyzing, evaluating, applying knowledge and creativity.

Finally, play supports positive attitudes toward learning. These include imagination, curiosity, enthusiasm, and persistence. The type of learning processes and skills fostered in play cannot be replicated through traditional rote learning, where the emphasis is on remembering facts.

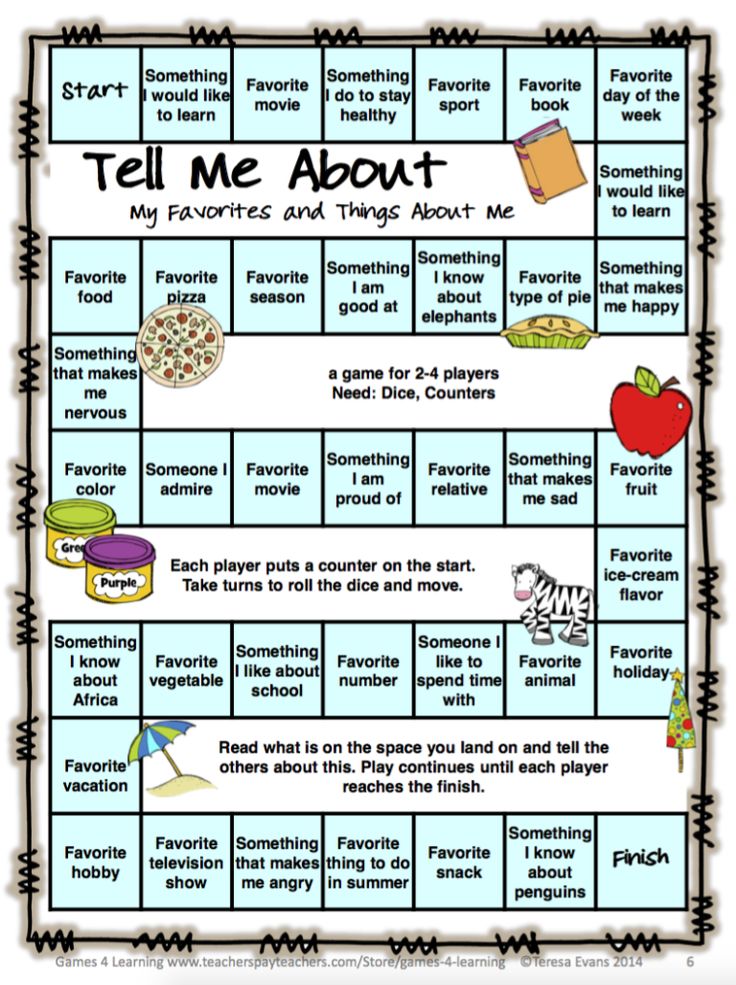

Play-Based Learning and Executive FunctionChildren are naturally motivated to play. A play-based program builds on this motivation, using it as a context for learning. In this framework, children can explore, experiment, discover, and solve problems in imaginative and playful ways. They also expand their executive function skills by practicing their ability to retain information—like where the butterfly was in the spread of memory cards, who had the “4” in Go Fish, and what color card they have and need for in UNO.

When students play games that involve strategy, they have an opportunity to make plans, and then to adjust those plans in response to what happens during gameplay. This engages other critical executive function skills like inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. Think Battleship, checkers, tick-tack-toe, or Hide-and-Go-Seek; these games have children develop a plan and adjust on the fly in response to the other player.

This engages other critical executive function skills like inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. Think Battleship, checkers, tick-tack-toe, or Hide-and-Go-Seek; these games have children develop a plan and adjust on the fly in response to the other player.

Teachers can provide opportunities for students to build their executive function skills through meaningful social interactions and fun games—including activities as common as checkers, Simon Says, and I Spy. Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child offers lots of great ideas for children at different ages.

Play and the Value of Active LearningPlay-based learning is an important way to develop active learning. Active learning means using your brain in lots of ways. When children play, they explore the world—and build on their understanding of the natural and social environments around them.

On the physical level, kids work on both gross and fine motor development through play. Students working in a play-based classroom explore spatial relationships and hone these important motor capabilities. In fact, it is before the age of 7 years—traditionally known as “pre-academic” age—when children desperately need to have a multitude of whole-body sensory experiences daily in order to develop strong bodies and minds. This is best done outside where the senses can be fully engaged, and young bodies are challenged by the uneven and unpredictable, ever-changing terrain—but a well-equipped, thoughtfully set-up classroom can be just as effective.

Students working in a play-based classroom explore spatial relationships and hone these important motor capabilities. In fact, it is before the age of 7 years—traditionally known as “pre-academic” age—when children desperately need to have a multitude of whole-body sensory experiences daily in order to develop strong bodies and minds. This is best done outside where the senses can be fully engaged, and young bodies are challenged by the uneven and unpredictable, ever-changing terrain—but a well-equipped, thoughtfully set-up classroom can be just as effective.

Children build language skills while developing content knowledge. Plus, cooperative experiences provide children the opportunity to cultivate social skills, competencies, and a disposition to learn.

Play also builds self-esteem. Children are most receptive to learning during play and exploration and are generally willing to persist in order to learn something new or solve a problem. The experience of successfully working through something new or challenging helps kids gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

The experience of successfully working through something new or challenging helps kids gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

And a big winner in play is Social development. Interpersonal skills like listening, negotiating, and compromising are challenging for 4- and 5-year-olds (as well as older kids and adults). Through play, children get to practice social and language skills, think creatively, and gather information about the world through their senses. Think about the games that students come up with on their own—they are creative, often intricate, and their “rules” always have to be negotiated.

Games and GamificationSome educators regard the time kids spend socializing with their friends while gaming online as the salvation during the COVID-19 pandemic, or in any scenario where a child might experience barriers to in-person socialization. In addition to the social connections, there is an increased understanding that video games can actually improve kids’ remote learning. As educators we know that using student’s passions to engage them in learning is critical and kids love games. Done right, gaming and gamification of games can engage both intrinsic (pleasure and fulfillment) and extrinsic (recognition and rewards) motivation.

As educators we know that using student’s passions to engage them in learning is critical and kids love games. Done right, gaming and gamification of games can engage both intrinsic (pleasure and fulfillment) and extrinsic (recognition and rewards) motivation.

Teachers help enhance play-based learning by creating environments in which rich play experiences are available. The act of being a teacher is recognizing the goals of education, understanding how learning works, and figuring out how to apply all this to each student, one at a time. Teaching children how to learn is a strong basis for every grade level.

It is pretty clear that students learn through play. Every child. Some use play to explore their world, others to gain language, and on and on and on. In fact, we have also seen that it is a natural impulse—like getting hungry, or crying when upset, children play. So why not lean into it? Find ways to increase the time spent on play in your class. Whether you create centers for dramatic play, bring in costume boxes, explore problem solving with board games, or design your own multiplication board game or even better, have your students design that game, lean in. Use what is part of a child’s fabric to enhance instruction and learning.

Whether you create centers for dramatic play, bring in costume boxes, explore problem solving with board games, or design your own multiplication board game or even better, have your students design that game, lean in. Use what is part of a child’s fabric to enhance instruction and learning.

Looking for additional ideas to make your classroom a more hands-on learning environment for your young students? Check out this blog post on Exploring CTE at the Elementary Level Through Play for more outside-the-box inspiration!

Interested in learning more about play-based learning? Check out our OnDemand webinar where we explore this topic in-depth!

This post was originally published October 2019 and has been updated.

What is more important: to play or to study?

Parents who do not take their child to all kinds of developmental activities and clubs and just let him play often get disapproving looks. Like, business time, fun hour. Who is right? And what is more important for a little person: study or play? What role does play play in human development, how does the mechanism of mastering new skills, understanding oneself and the world around work? And which games work for the benefit of development, and which ones do the opposite?

Why children play

People did not think yesterday about the meaning of the game. In 1898, the philosopher Karl Groos, in his book The Play of Animals, studied the question of why the children of all mammals play from an evolutionary point of view. He concluded that the game originated as a way to learn the skills needed to survive and reproduce. Only mammals have a period of childhood and play - the highest stage of development of the animal world. At the same time, it is longer for predators, because hunting is much more difficult than gathering. Only the most developed societies can afford to have a long childhood, in primitive communities the period of play is not so long - children are immediately included in the process of mastering everyday and labor skills. Humans play much more than other species: they have to learn a lot of things related to the culture in which they will grow up and live. The more survival depends on skill rather than instinct, the longer the period of the game. nine0003

In 1898, the philosopher Karl Groos, in his book The Play of Animals, studied the question of why the children of all mammals play from an evolutionary point of view. He concluded that the game originated as a way to learn the skills needed to survive and reproduce. Only mammals have a period of childhood and play - the highest stage of development of the animal world. At the same time, it is longer for predators, because hunting is much more difficult than gathering. Only the most developed societies can afford to have a long childhood, in primitive communities the period of play is not so long - children are immediately included in the process of mastering everyday and labor skills. Humans play much more than other species: they have to learn a lot of things related to the culture in which they will grow up and live. The more survival depends on skill rather than instinct, the longer the period of the game. nine0003

One of the main tasks of the game is to test the measure of risk, to master the ability to control fears, to learn how to cope with dangerous situations physically and emotionally. In their article, Norwegian psychologists Leif Kennar and Ellen Sandsetter argue that modern playgrounds must be dangerous. Remember how the generation of the 70s grew up. We played robber Cossacks, climbed trees, fired slingshots, jumped rubber bands, skated down ice slides, bungee and car tires. We came home with scratches and bruises, and no one restricted us. Our parents understood that it was impossible and does not make sense to raise a child under a cap. He himself needs to learn how to measure his abilities with desires, to get burned, fall and rise. This is how a full-fledged independent personality is formed, not dependent on parental prohibitions and control. nine0003

In their article, Norwegian psychologists Leif Kennar and Ellen Sandsetter argue that modern playgrounds must be dangerous. Remember how the generation of the 70s grew up. We played robber Cossacks, climbed trees, fired slingshots, jumped rubber bands, skated down ice slides, bungee and car tires. We came home with scratches and bruises, and no one restricted us. Our parents understood that it was impossible and does not make sense to raise a child under a cap. He himself needs to learn how to measure his abilities with desires, to get burned, fall and rise. This is how a full-fledged independent personality is formed, not dependent on parental prohibitions and control. nine0003

In order to protect children from dangers, they must be taught to cope with them

At some point, adults began to dispose of children's leisure at their own discretion: society looks askance at parents whose children are "not busy" - countless circles, sections, additional classes and preparation for the olympiads. These same adults have piled up unimaginably boring playgrounds in the yards that meet all safety standards, to which children practically do not fit. By artificially creating a "safe" environment for the game, we are raising victimized and weak people who are waiting for someone's instructions to take the next step. “You can cover a child with cotton wool, endlessly sterilize his toys, but in the end he will grow up and face bacteria, hard ground and sharp corners,” says Leif Kennar. This, of course, is not about deliberately offering children dangerous games or, moreover, pushing them beyond their limits, as physical education teachers often do, forcing schoolchildren to climb a rope under the ceiling or hang on a Swedish wall head down without arms. . Exactly the opposite: children themselves will gradually complicate their tasks and increase the level of danger if they are allowed to study step by step their body, its sensations in space, ways of interacting with the environment. Such ideas are implemented by the physical education teacher and the author of his own method of physical development Sergey Reutsky, offering such game complexes and materials with the help of which they learn to extricate themselves from rope labyrinths or cocoons, free themselves from under mats, walk along thin ropes, climb high structural elements and etc.

These same adults have piled up unimaginably boring playgrounds in the yards that meet all safety standards, to which children practically do not fit. By artificially creating a "safe" environment for the game, we are raising victimized and weak people who are waiting for someone's instructions to take the next step. “You can cover a child with cotton wool, endlessly sterilize his toys, but in the end he will grow up and face bacteria, hard ground and sharp corners,” says Leif Kennar. This, of course, is not about deliberately offering children dangerous games or, moreover, pushing them beyond their limits, as physical education teachers often do, forcing schoolchildren to climb a rope under the ceiling or hang on a Swedish wall head down without arms. . Exactly the opposite: children themselves will gradually complicate their tasks and increase the level of danger if they are allowed to study step by step their body, its sensations in space, ways of interacting with the environment. Such ideas are implemented by the physical education teacher and the author of his own method of physical development Sergey Reutsky, offering such game complexes and materials with the help of which they learn to extricate themselves from rope labyrinths or cocoons, free themselves from under mats, walk along thin ropes, climb high structural elements and etc. nine0003

nine0003

“Children are interested in climbing, and not just climbing, but always finding new ways and overcoming new difficulties. And I have a strange suspicion and belief that children are designed in such a way that they constantly train themselves in overcoming if they are not interfered with! So, in the space of the complex, choosing a task according to their strength, children accidentally train such physical qualities as strength, agility, endurance.

Sergei Reutsky, physical education teacher and author of his own method of physical development

Not only physical, but also intellectual development

From the point of view of modern neuropsychology, the posterior sections of the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures are responsible for mastering operations, cramming, practicing techniques. This is the lot of performers. On the contrary, orientation in situations and meanings, directing, programming and control is the highest function, which is regulated by the latest maturing parts of the brain: the frontal parts of the cerebral cortex. This is the path of leaders, innovators, inventors, businessmen. nine0003

This is the path of leaders, innovators, inventors, businessmen. nine0003

“The shortcomings of the rote learning system are well known: lack of social and practical skills, lack of self-discipline and imagination, loss of curiosity and desire for education… We will realize that Chinese schools are changing for the better when grades start to drop.”

Jiang Xueqin, a well-known Chinese teacher and methodologist in an article for The Wall Street Journal

Finally, it is a full-fledged long happy childhood, where the child was allowed to be a child, where he was given that measure of excitement, drive, research ardor, creative search that raises the child over his current capabilities, becomes a source of strength, a powerful psychological resource in the future. When it's hard for us, we turn to childhood, find support, support and consolation in it. The task of an adult is to make sure that this source is filled. In fact, do not interfere with the mechanisms laid down by nature. Do not knock down children's settings. It’s not just important to allocate time for the game. Play is the most important leading activity of a child. I hope I convinced you of this. nine0003

Do not knock down children's settings. It’s not just important to allocate time for the game. Play is the most important leading activity of a child. I hope I convinced you of this. nine0003

Photo: Pressmaster/YanLev/Shutterstock.com

psychologydevelopmenteducationhelpful tipsschool . The author of the book "Freedom to Learn" Peter Gray is sure of this. It helps parents to take a fresh look at the learning process and understand how significant the game is in the life of a child. Mel, together with the Mann, Ivanov and Ferber publishing house, present five arguments from the book in favor of making learning more playful and fun. nine0003

1. If you force a child to study well, you can take away his desire to study at all

Psychologists came to these results during the following experiment. They watched the students play billiards. At first they discreetly recorded the results of each player, then they began to make it more obvious so that the players noticed that their game was being evaluated.

The researchers came to the conclusion that experienced players (who can be called masters) began to play much better, while beginners, on the contrary, began to score significantly less points. nine0003

It turned out that this observation is also true for schoolchildren: grades have a positive effect only on those who already know or can do something, and if the child is just learning, then grades interfere with him and make him absorb the material much worse.

2. If the creative process is stimulated, the child's abilities will not develop

Psychologist Teresa Amabile has been studying creativity for many years. She did this experiment. The children had to draw a picture or write a story. It had to be done at speed. nine0003

At the same time, she motivated some participants: she informed them that their work would be exhibited at a competition or a prize was due for the best one. Other participants were not promised anything.

Why you shouldn't help kids with creative tasks

Teresa then asked the experts to evaluate all the work. It turned out that the work of those who were motivated turned out to be less creative and innovative.

It turned out that the work of those who were motivated turned out to be less creative and innovative.

This proves that any incentives reduce the ability to think creatively and harm creativity. nine0003

If a student draws something just for fun, then his creative abilities are revealed to a greater extent.

3. Play helps to develop creativity

This experiment helped scientists figure out how to develop children's creativity. A group of kids were asked to make collages. Before starting work, some guys were told to play with salt dough for 25 minutes, others were forced to rewrite the text. As a result, the collages of kids who managed to play before the experiment turned out to be more creative. nine0003

4. Laughter improves a child's analytical thinking

Alice Isen, professor at Cornell University, found out how mood affects our analytical abilities.

He offered students to solve a classical analytical problem. The essence of the experiment: each of the participants receives a box of buttons and a candle. The task is to fix the candle on the wall so that it can burn and the wax does not fall on the floor.

The task is to fix the candle on the wall so that it can burn and the wax does not fall on the floor.

“If children don’t play, adults are to blame”

Before giving a task to the students, he showed the first group of children a fragment of a funny film, the second group showed a piece of a rather boring movie of the same duration, and the third group showed nothing.

The results were amazing: 3/4 of the students who watched the comedy solved the problem, and only 20% of the children from the other groups were able to attach the candle to the wall correctly.

The conclusion is simple: even five minutes of humor stimulates creativity and ingenuity.

5. Games help develop logic

Toddlers can solve challenging tasks for their age in play mode. British scientists came to this conclusion. They asked the children the following logic puzzle:

All birds meow

Kesha is a bird.

Does Kesha meow?

Children 10-11 years old could not cope with him.