Learning how to read 1st grade

First grade is critical for reading skills, but some kids are way behind

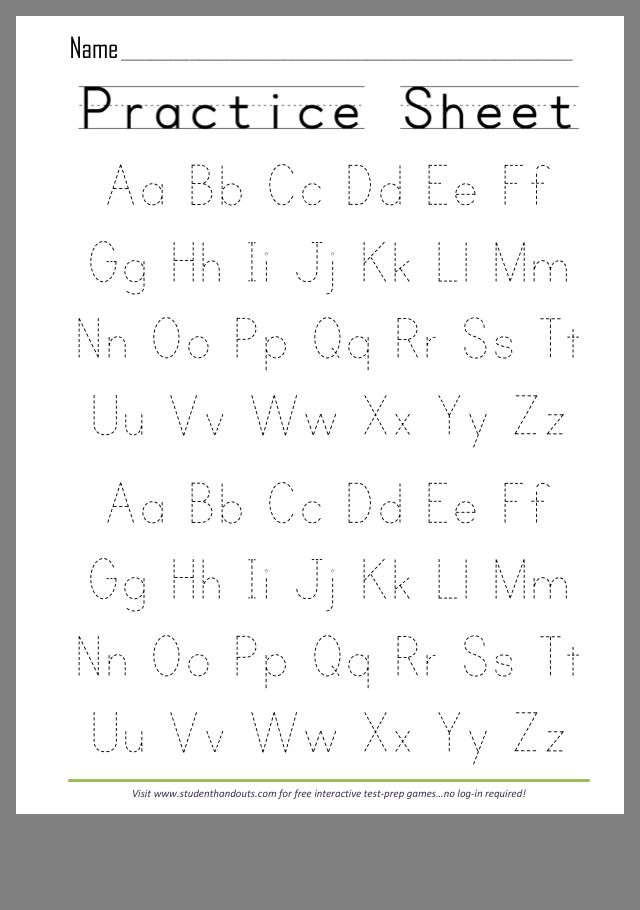

AUSTIN, Texas — Most years, by the third week of first grade, Heather Miller is working with her class on writing the beginning, middle and end of simple words. This year, she had to backtrack — all the way to the letter “H.”

This story also appeared in USA Today“Do we start at the bottom or do we start at the top?” Miller asked as she stood in front of her class at Doss Elementary.

“Top!” chorused a few voices.

“When I do an H, I do a straight line down, another straight line down and then I cross in the middle,” Miller said, demonstrating on a projector in a front corner of the classroom.

Her 25 students set to work on their own. Some got it right away. One student watched his tablemate before slowly copying down his own H’s. Another tested her own way of writing the letter: one line down, cross in the middle, then another line down. “Your paper is upside down, let’s turn it,” Miller said to a student who was trying to write letters while leaning sideways, almost out of her seat.

In classrooms across the country, the first months of school this fall have laid bare what many in education feared: Students are way behind in skills they should have mastered already.

Children in early elementary school have had their most formative first few years of education disrupted by the pandemic, years when they learn basic math and reading skills and important social-emotional skills, like how to get along with peers and follow routines in a classroom.

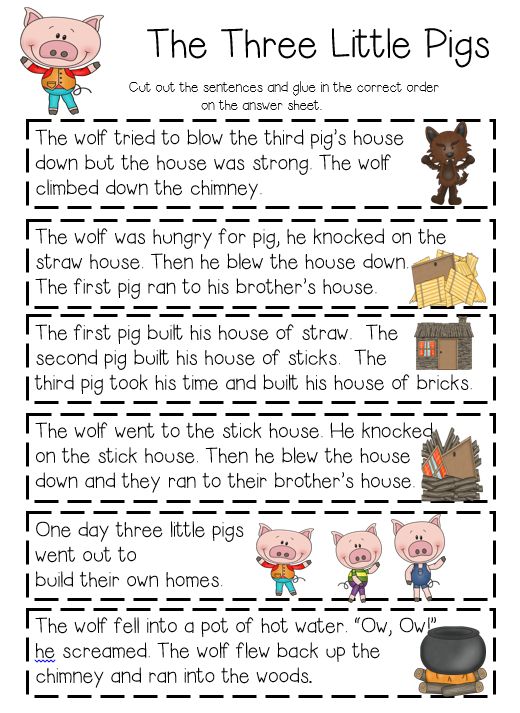

While experts say it’s likely these students will catch up in many skills, the stakes are especially high around literacy. Research shows if children are struggling to read at the end of first grade, they are likely to still be struggling as fourth graders. And in many states with third grade reading “gates” in place, students could be at risk of getting held back if they haven’t caught up within a few years.

40 percent — The number of first grade students “well below grade level” in reading in 2020, compared with 27 percent in 2019, according to Amplify Education Inc.

First grade in particular — “the reading year,” as Miller calls it — is pivotal for elementary students, when their literacy skills “really take off.” Kindergarten focuses on easing children from a variety of educational backgrounds — or none at all — into formal schooling. In contrast, first grade concentrates on moving students from pre-reading skills and simple math, like counting, to more complex skills, like reading and writing sentences and adding and subtracting numbers.

By the end of first grade in Texas, students are expected to be able to mentally add or subtract 10 from any given two-digit number, retell stories using key details and write narratives that sequence events. The benchmarks are similar to those used in the more than 40 states that, along with the District of Columbia, adopted the national Common Core standards a decade ago.

Teachers often see a range of literacy skills, and that could be more pronounced this year due to the pandemic

Teacher Heather Miller has seen a wide range of writing skills among her first grade students, with some students already writing complex sentences while others are still working on letter formation. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller has already seen improvement in writing, including among students who started the year without a strong grasp of forming letters. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report

Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller has already seen improvement in writing, including among students who started the year without a strong grasp of forming letters. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportHeather Miller’s students frequently write in notebooks to show their progress in writing skills. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger Report“They really grow as readers in first grade, and writers,” Miller said. “It’s where they build their confidence in their fluency.”

But about half of Miller’s class of first graders at Doss Elementary, a spacious, bright, newly built school in northwest Austin, spent kindergarten online. Some were among the tens of thousands of children who sat out kindergarten entirely last year.

More than a month into this school year, Miller found she was spending extensive time on social lessons she used to teach in kindergarten, like sharing and problem-solving. She stopped class repeatedly to mediate disagreements. Finally, she resorted to an activity she used to use in kindergarten: role-playing social scenarios, like what to do if someone accidentally trips you.

She stopped class repeatedly to mediate disagreements. Finally, she resorted to an activity she used to use in kindergarten: role-playing social scenarios, like what to do if someone accidentally trips you.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs … there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

Heather Miller, first grade teacher

“So many kids are missing that piece from last year because they were, you know, virtual or on an iPad for most of the time, and they don’t know how to problem-solve with each other,” Miller said. “That’s just caused a lot of disruption during the school day.”

Her students were also not as independent as they had been in previous years. Used to working on tablets or laptops for much of their day, many of these students were also behind in fine motor skills, struggling to use scissors and still working on correctly writing numbers.

Related: What parents need to know about the research on how kids learn to read

Instead of working on first grade standards, Miller was devoting time on this Friday morning in early September to forming upper- and lowercase letters, a kindergarten standard in Texas and the majority of other states. As students finished practicing the letter H, they moved on to the assignment at the bottom of the page: Draw a picture and write a word describing something that starts with an H.

As students finished practicing the letter H, they moved on to the assignment at the bottom of the page: Draw a picture and write a word describing something that starts with an H.

“H-r-o-s” one student wrote next to a picture of a horse standing on green grass in front of a light blue sky. “H-e-a-r-s” another student wrote next to a picture of a strip of brown hair, floating in the white picture box. “You should draw a face there,” suggested his tablemate, pointing at the blank space under the hair.

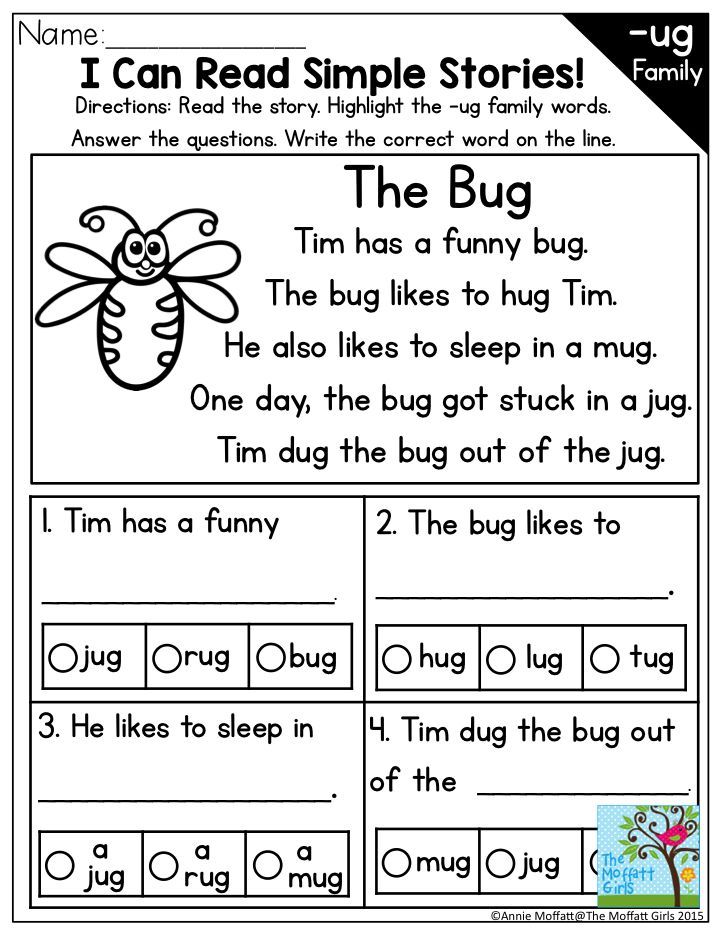

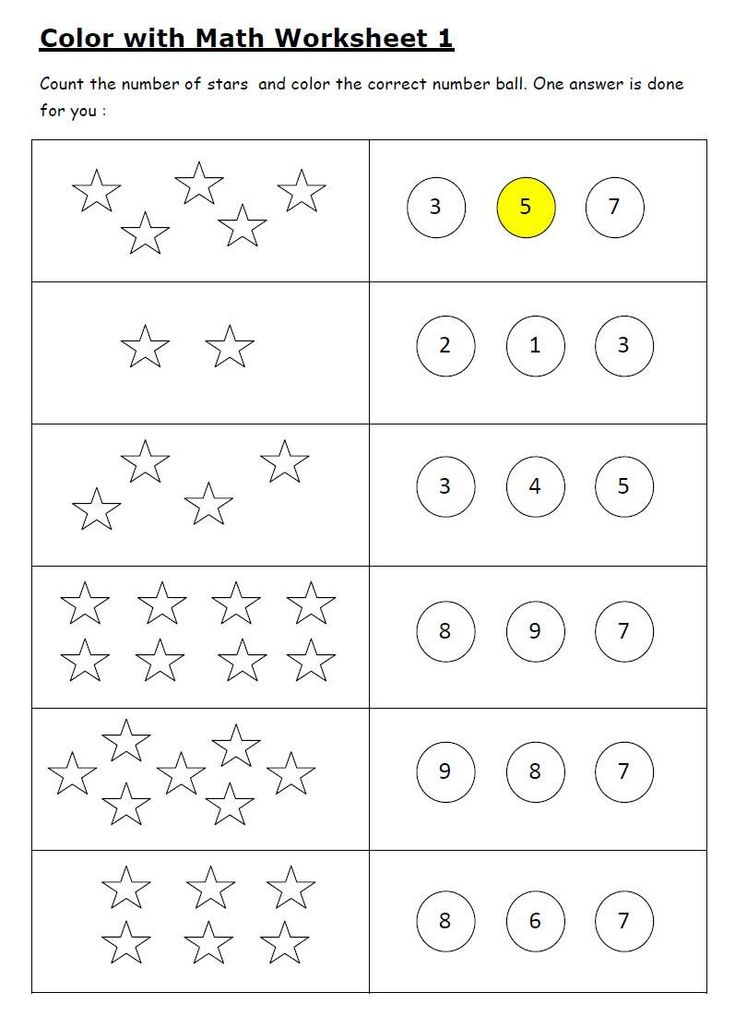

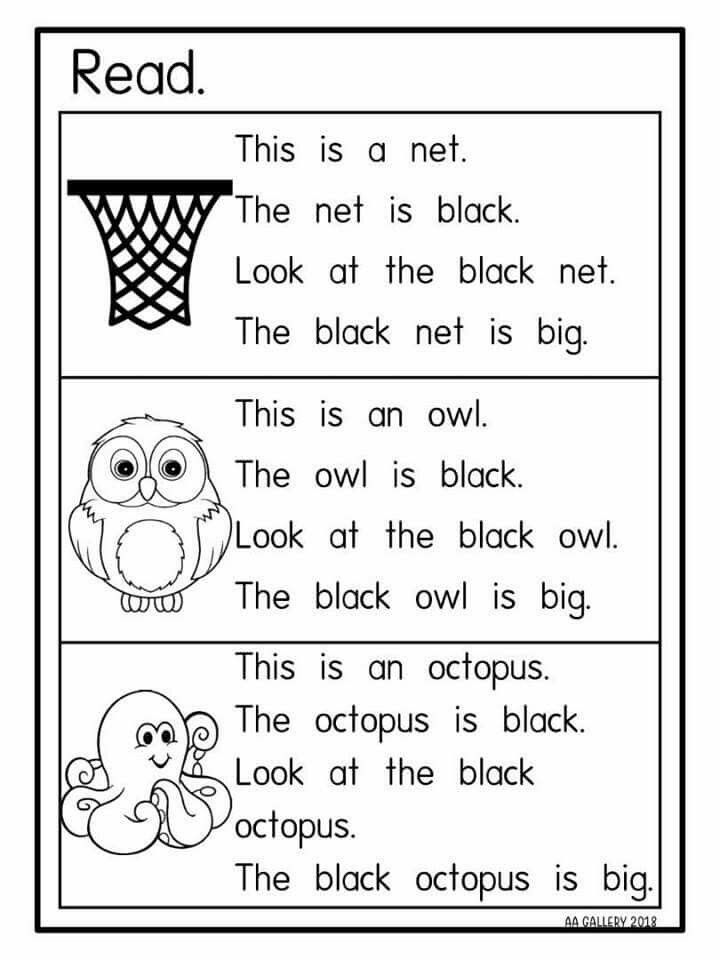

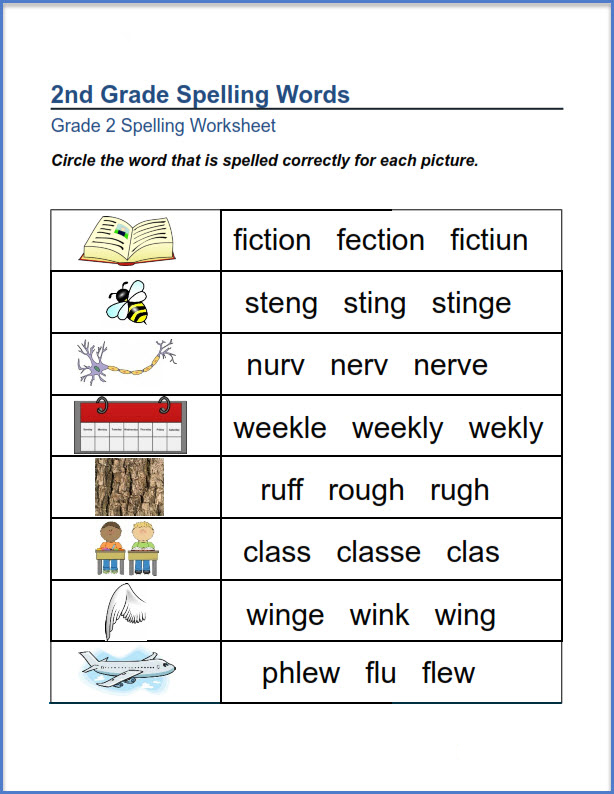

Students work on a phonics activity during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s first graders are a case study in the scale, depth and unevenness of learning loss during the pandemic. One report by Amplify Education Inc., which creates curriculum, assessment and intervention products, found children in first and second grade experienced dramatic drops in grade level reading scores compared with those in previous years.

In 2020, 40 percent of first grade students and 35 percent of second grade students were scoring “well below grade level” on a reading assessment, compared with 27 percent and 29 percent the previous year. That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

That means a school would need to offer “intensive intervention” to nearly 50 percent more students than before the pandemic.

Data analyzed by McKinsey & Company late last year concluded that children have lost at least one and a half months of reading. Other data show low-income, Black and Latinx students are falling further behind than their white peers, leading to worsening achievement gaps.

Experts say it’s now clear families who had time and resources to help their children with academics when schooling was disrupted had a tremendous advantage.

“Higher-income parents, higher-educated parents, are likely to have worked with their children to teach them to read and basic numbers, and some of those really basic early foundational skills that kids generally get in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade,” said Melissa Clearfield, a professor of psychology who focuses on young children and poverty at Whitman College.

“Families who were not able to, either because their parents were essential workers or children whose parents are significantly low-income or not educated, they’re going to be really far behind. ”

”

What Miller has observed in the first few weeks of the school year is likely taking place in classrooms nationwide, experts say. In April, researchers with the nonprofit NWEA, which develops pre-K-12 assessments, predicted how the pandemic’s disruptions would manifest among the kindergarten class of 2021: a wider range of ability levels; large class sizes with more diverse ages because some parents held children back a grade; and students unfamiliar with in-person classroom routines.

“We predicted that there would be a lot of diversity in skills,” said Brooke Mabry, strategic content design coordinator for NWEA Professional Learning. That includes skills related to academics, social-emotional learning and executive functioning, she added.

The varying experiences children had with school last year also impacted fine motor skill development, independence, ability to navigate conflicts and the “unfinished learning” teachers are now observing, she added.

Related: Remote learning a bust? Some families consider having their child repeat kindergarten

While switching to remote learning was hard on many students, younger students were generally unable to log themselves on to a computer independently and focus on virtual lessons for extended periods of time. Teachers, who usually rely on small, in-person groups for early literacy skills, instead had to teach letters, sounds and sight words via online platforms.

Miller had the unwieldy task of teaching kids both in person and online, spending her year pivoting between students in front of her and students on her computer screen, using her projector to display books to students at home and teaching reading skills via virtual groups.

Now, with students in front of her again, Miller was finding that those online lessons weren’t as useful as many had hoped.

Miller, 30, is a calm, confident teacher who is in her eighth year of teaching and her second at Doss. She usually has students with a wide range of ability levels at the beginning of the year, although Doss is relatively affluent. Nearly 62 percent of students at the school are white, and fewer than 20 percent are economically disadvantaged, compared with the district average of nearly 53 percent. In 2019, 95 percent of Doss’ students passed the state reading assessment.

Students play outside Doss Elementary in Austin, Texas. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportBut this year, Miller saw larger gaps in reading skills than ever before. Usually, her first graders would start with reading levels ranging from mid-kindergarten to second grade. This year, the levels spanned early kindergarten up to fourth grade.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs,” Miller said. “I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

“I just feel like — and I’m sure every teacher feels like this — there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

She’s also seen higher literacy levels for kids who went to school in person last year. To her, it speaks to the immense benefits kids get from all aspects of in-person learning. “It just shows how important it is for these kids to be around their peers and just have normalcy,” she said.

Related: Summer school programs race to help students most in danger of falling behind

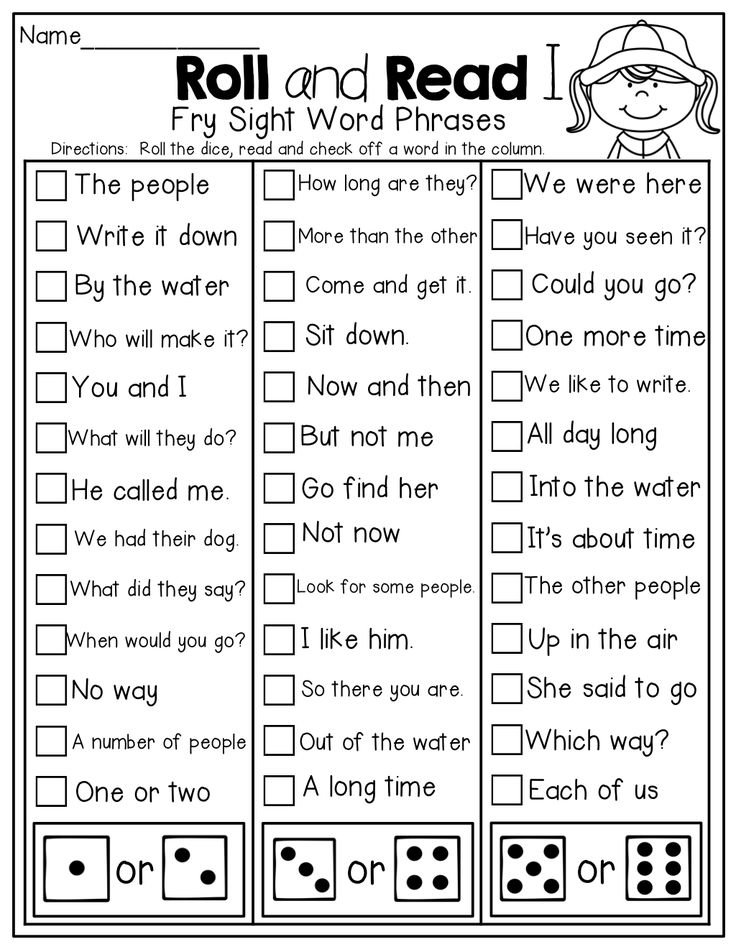

To catch kids up, Miller is relying on, among other things, one of the staples of the early elementary classroom: center time. For two hours a day, she works with small groups of students on the specific math and reading skills they are lacking.

On a recent October morning, Miller divided her class into five groups to rotate through various activities around her room. She gave her students a few minutes to finish a writing assignment as she pulled out several sets of small books at various reading levels; colorful plastic, hollow phones so her students could hear themselves read; and for a group of struggling readers, a matching game featuring cards showing various letters and pictures.

“I feel like I’m teaching four grades,” Miller said as she arranged the materials on her desk.

Several minutes later, seated at a table in the back of the room with five of her grade-level readers, Miller handed them each a phone, a small book and a green witch’s finger to help them point at the words in the book. “Today we’re going to talk about our reading tools,” Miller said, holding up a blue plastic phone. “These are called whisper phones. You whisper so you can hear yourself sound out the words,” she said. “Do these go on our heads?”

“No!” the students said, giggling.

“You know what these are for?” she said, holding up a rubber finger.

“Um, they’re for reading,” one student said. “’Cause I had them in kindergarten.”

“Very good. Are these for picking your nose?” Miller asked.

“No!” the students said, laughing.

She placed a book in front of each child and walked them through a series of exercises, including looking at the cover and predicting what the book would be about.

Then, they opened their books and began to read in a whisper. Miller turned from one side of the table to the other, listening as students read to themselves, pointing at each word with their green rubber fingers. She helped them sound out challenging words, like “away.” One by one, the students finished the book. A few read it several times in the minutes allotted.

Students practice reading using whisper phones during center time in their first grade classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportMiller’s next group, all of whom were reading far below grade level, required a different activity. Rather than handing out a book, Miller pulled out a letter-matching game at the table, using materials she had from her days as a kindergarten teacher. She placed two small laminated cards on the table, one showing the letter D and a picture of a dog, and one with the letter B and a picture of a ball.

“We’re going to do your letters today,” Miller said to the group. “What letter is this?” she asked, pointing to the B.

“Ball!” one student responded.

“What letter?” Miller asked again. There was a pause.

“B!” another student responded.

“What sound does it make?”

“Buh,” a third student said.

The students ran through the activity, looking at pictures of items starting with B and D like a doll, ball, dog and dolphin, and sorting them into piles based on the starting letter.

A student reads a book during center time in Heather Miller’s classroom. Credit: Jackie Mader/ The Hechinger ReportExperts like Clearfield say finding new or different strategies to help students learn grade-level content after the last 18 months will be critical, even if that means pulling out activities typically used by lower grade levels, as Miller did with her lowest reading group.

It also may mean recruiting help from outside the classroom. Miller said Doss already had a strong team of interventionists to rely on, and several of her students receive extra reading help during the day.

Miller has also found it helpful to work with her fellow first grade teachers to solve a shared academic challenge. This fall, the first grade teachers all discovered that many of their students were behind in reading sight words. They began meeting regularly to share tips and strategies to combat this.

Despite the obvious need to catch kids up, Miller has been mindful of not coming on too strong with remediation efforts. “I don’t want to push them so hard where they get burned out,” she said on an October evening. “They’ve been through so much.”

Related: We know how to help young children cope with the trauma of the last year— but will we do it?

Mabry, of NWEA, said while catching students up is important, society needs to view the recovery process as a multiyear effort. “In previous years, when looking at unfinished learning and finding ways to get students to accelerated growth, we never expected that we would get students who need support to meet those accelerated goals in one year. We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

We would never approach it that way,” Mabry said. “Now, we’re so frantic. I think we’re frantic because we feel it’s this larger population.”

It’s a daunting task, but experts say there is hope.

“Kids will catch up eventually,” said Clearfield from Whitman College. But to get there, society may need to re-evaluate expectations, she added. “If most children in our community are behind by, like, a year or two, then our expectations for what is typical, it’s going to have to match where they are,” Clearfield said. “Otherwise, we are going to be constantly frustrated … we’re going to have expectations that don’t match their skills or abilities.”

By mid-autumn, Miller was heartened by what she was seeing in her classroom. Students were becoming more confident and independent. Their writing was stronger. There were fewer conflicts.

There were fewer conflicts.

One morning, Miller stood by her desk as students effortlessly transitioned from one activity to the next during center time. They quietly buzzed around, cleaning up activities and putting their notebooks away in cubbies as she prepared to work with a new group of students at her desk.

“It kind of gives me hope that we’ll be OK,” she said. “Even after last year, we’ll be OK.”

This story about reading skills was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

The Complete Guide For Parents

1st grade reading is only the beginning of your child’s lifelong journey toward becoming an enriched, excited reader!

HOMER is here with the essential information you need to figure out how you can help your child succeed with their 1st grade reading adventures, as well as how to have fun with reading!

The Essential Goals Of 1st Grade Reading

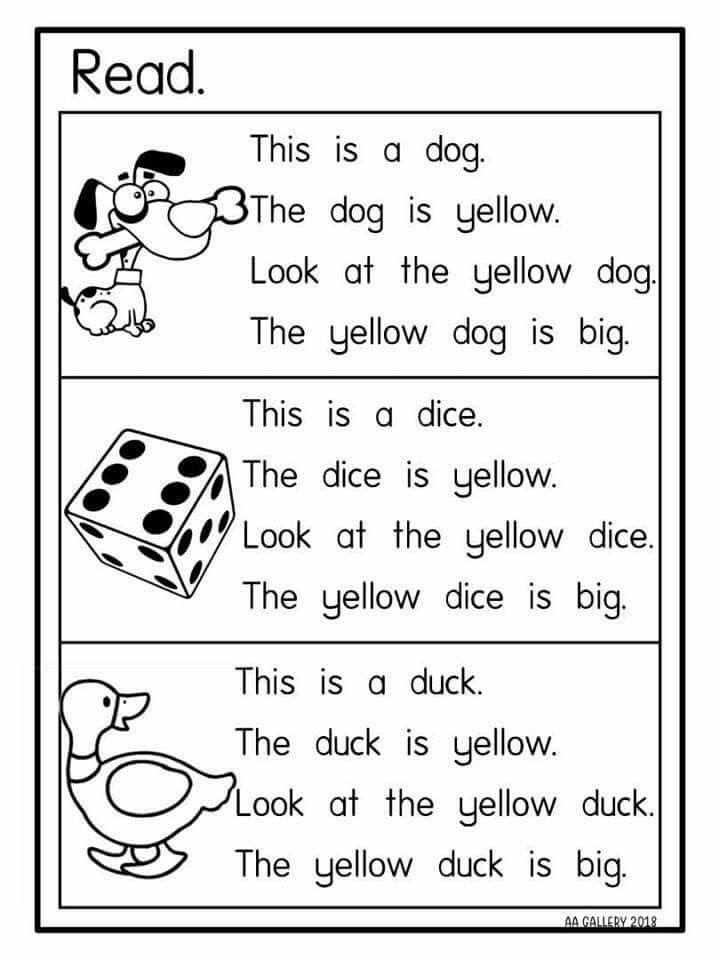

Phonological Awareness

Your first-grader will begin developing their phonological awareness skills before they even reach kindergarten, but these are the sort of skills that will help them for the rest of their life.

Building phonological awareness continues in first grade and means that your child understands how to manipulate, distinguish, and play with sounds and words.

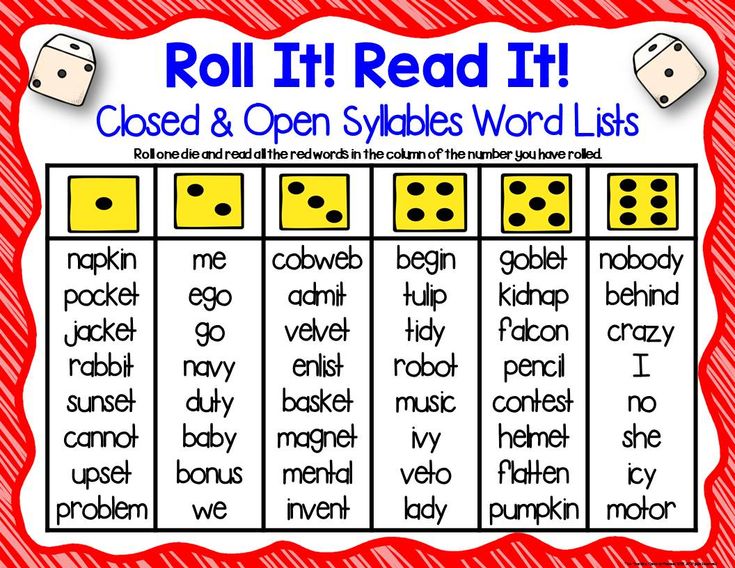

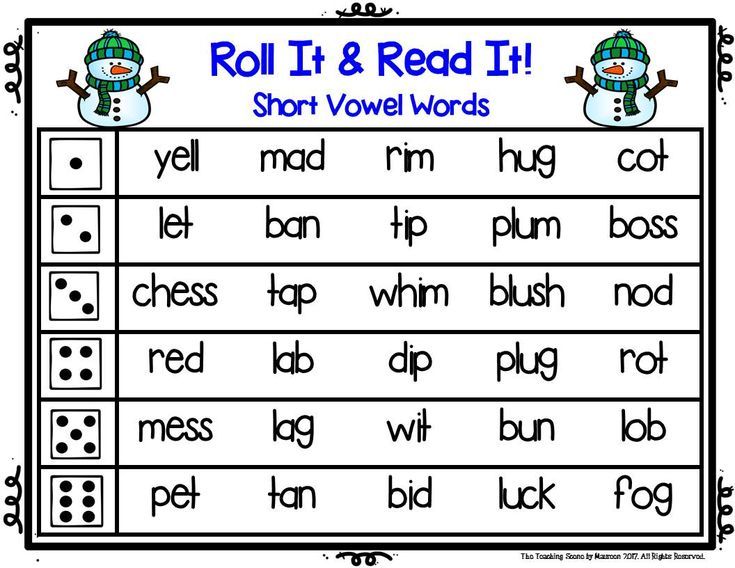

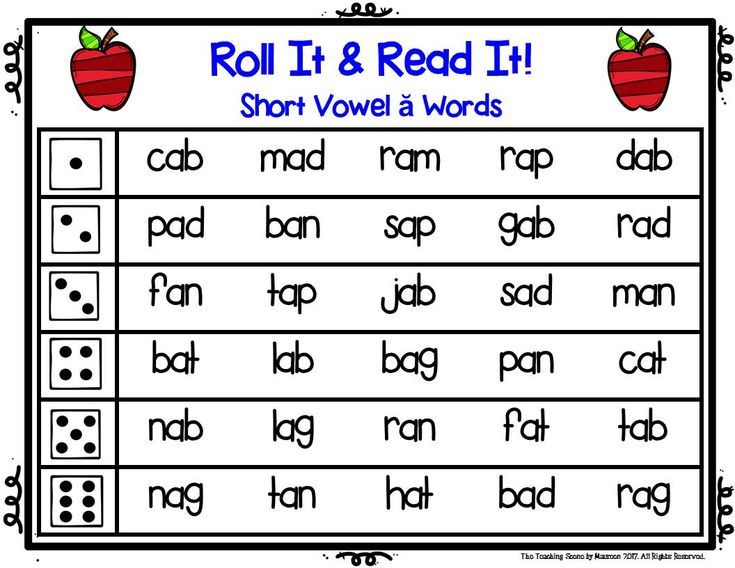

They’ll learn how to tell the difference between spoken words, syllables within words, and random sounds. They will begin to isolate syllables in words and blend syllables to make words. Finally, they’ll learn to isolate individual sounds within words and blend sounds to make words.

They will begin to isolate syllables in words and blend syllables to make words. Finally, they’ll learn to isolate individual sounds within words and blend sounds to make words.

These skills also mean they’ll have the ability to read words, both old and familiar, using their knowledge of phonics and their decoding skills.

With their strong grasp on phonological awareness, they’ll also have a higher success rate with spelling new words that are phonetically regular. This means even if they’ve never seen the word “rim” or “blink,” they’ll likely be able to spell it correctly on their first attempt.

Print Concepts

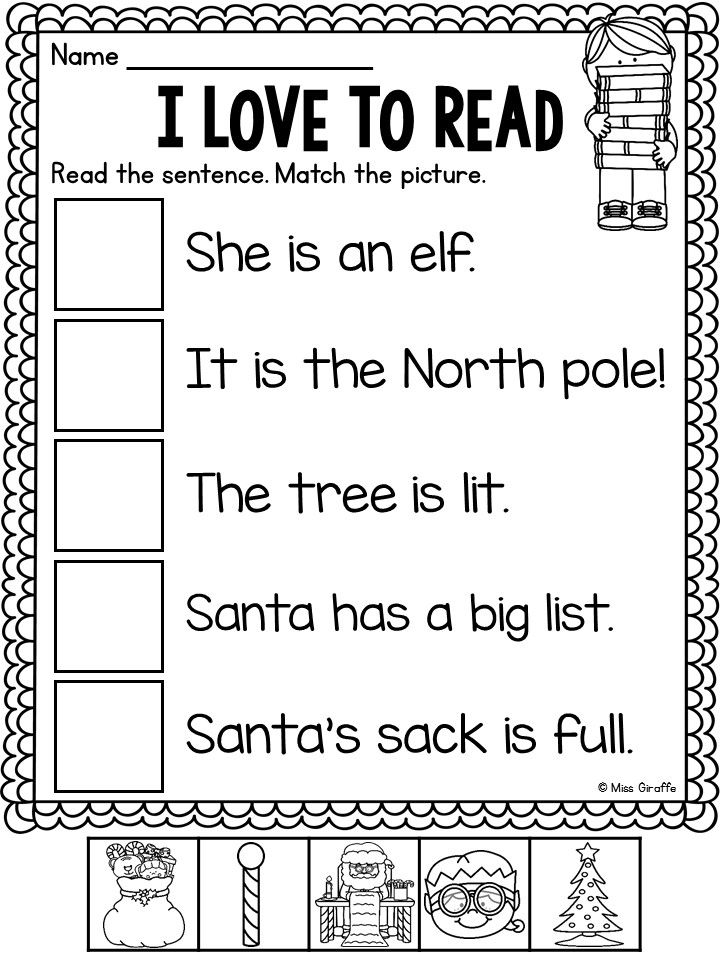

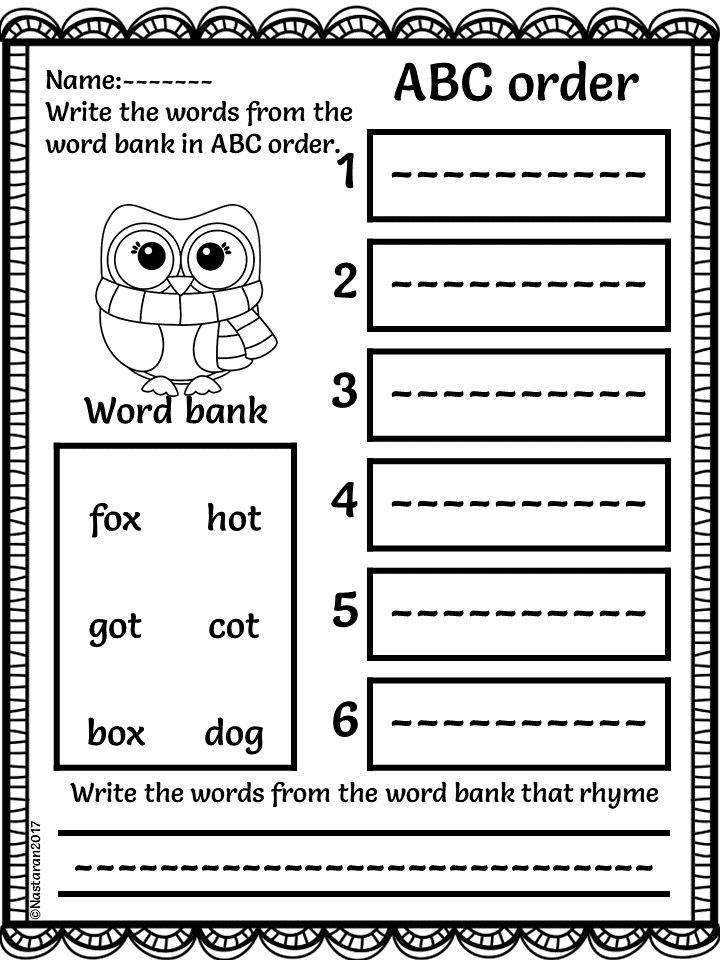

Advancing their knowledge of print concepts means your child isn’t just leveling up their reading — they’re expanding what they know about the boundaries of reading and writing!

Your first-grader will move beyond homogenous letter writing (writing in only uppercase or lowercase letters). Now they understand basic rules for capitalization along with punctuation rules. Periods, exclamation marks, question marks — your child will learn them all!

Periods, exclamation marks, question marks — your child will learn them all!

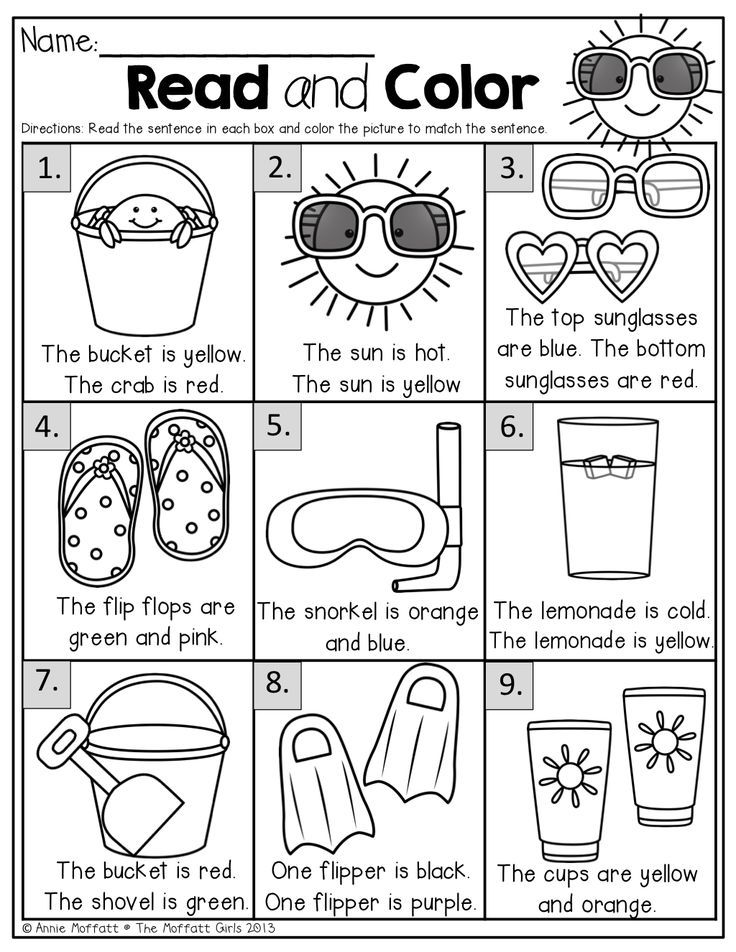

They may also be able to reliably pinpoint the emotional context of a sentence based on the ending punctuation. They’ll know when a sentence is supposed to be informative, inquisitive, or exciting.

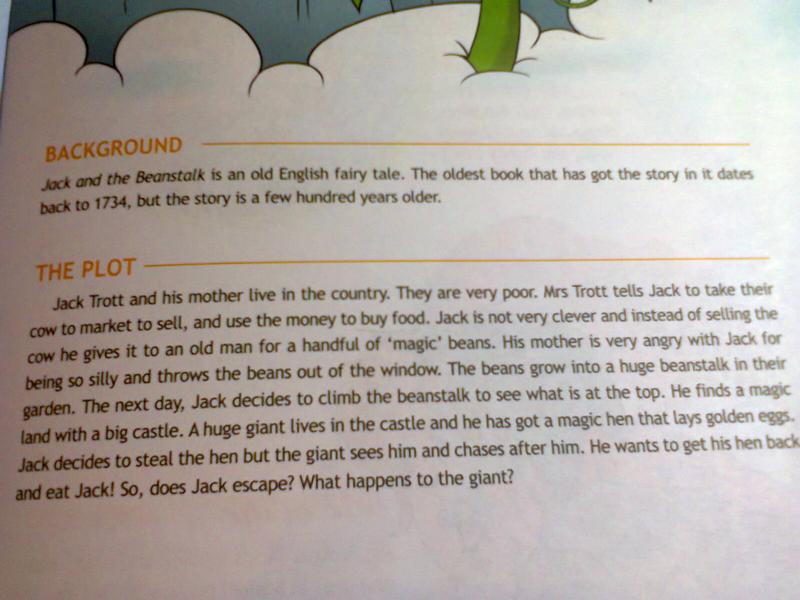

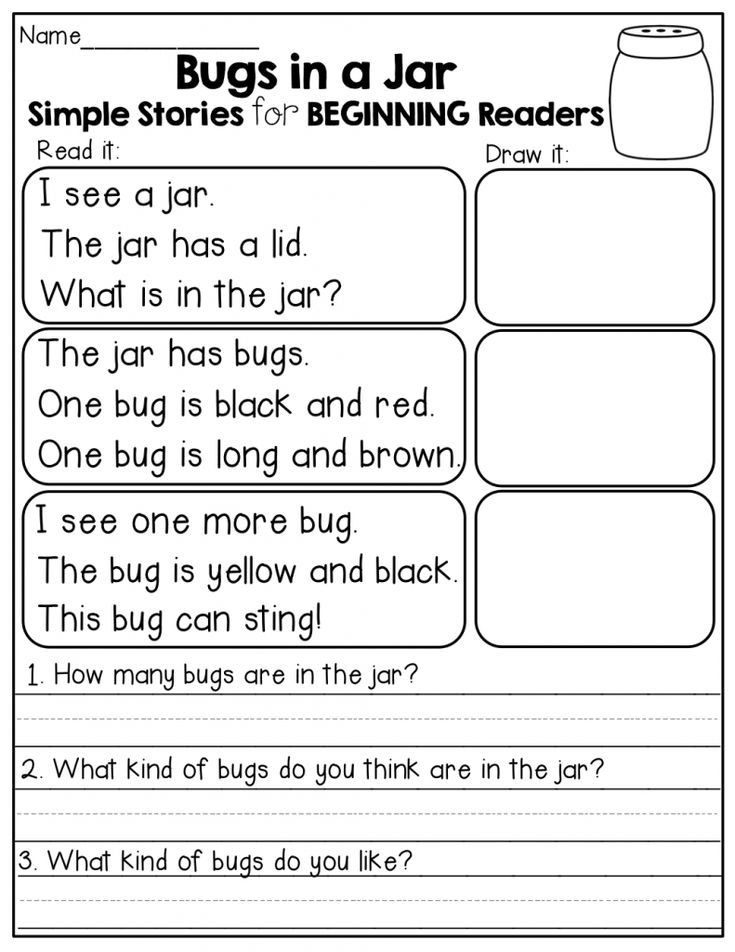

Additionally, your child will learn that when it comes to books, there are many places to go to figure out the “roadmap” of a story! They’ll know where to find information about the book — like its title — and where they can find the name of the author or illustrator.

They will understand that nonfiction books often have captions with extra facts and that some books have glossaries that can help them to understand the meaning of challenging words.

That’s not all! They’ll learn how to make predictions about a text based on its cover, title, or illustrations. Afterward, they’ll be able to compare and contrast their initial guess with what they actually read.

Although your child may be able to draw some conclusions about what they read, remember they’re still young. Their insights may only work at a surface level.

Their insights may only work at a surface level.

This is perfectly OK! Even asking basic questions about the text read will help reinforce the idea that it is important to think about what we read.

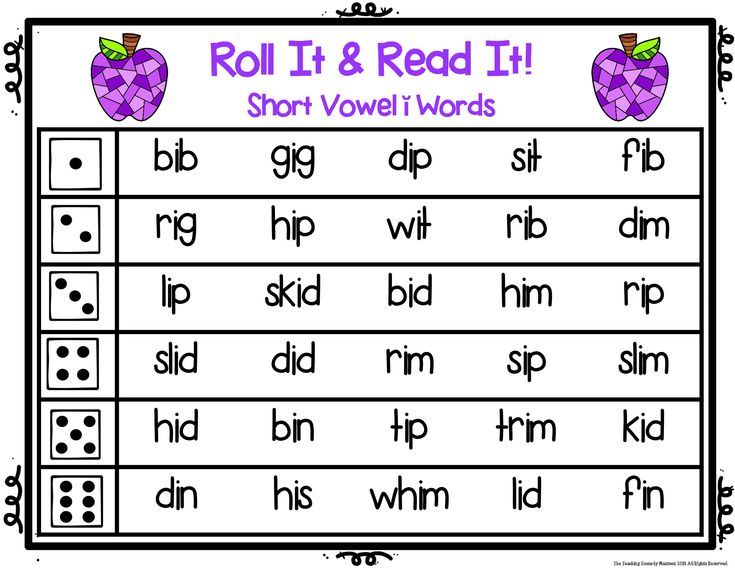

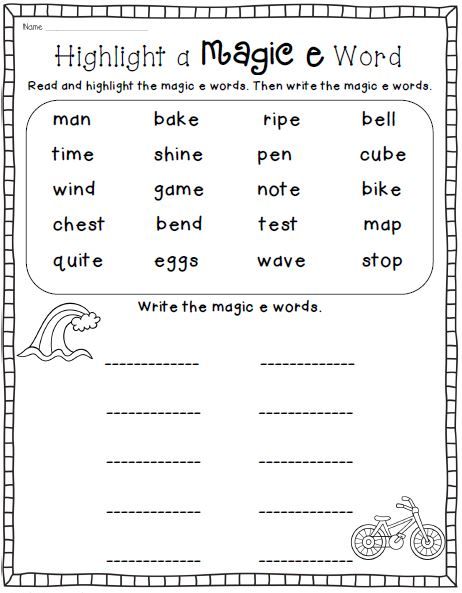

Phonics

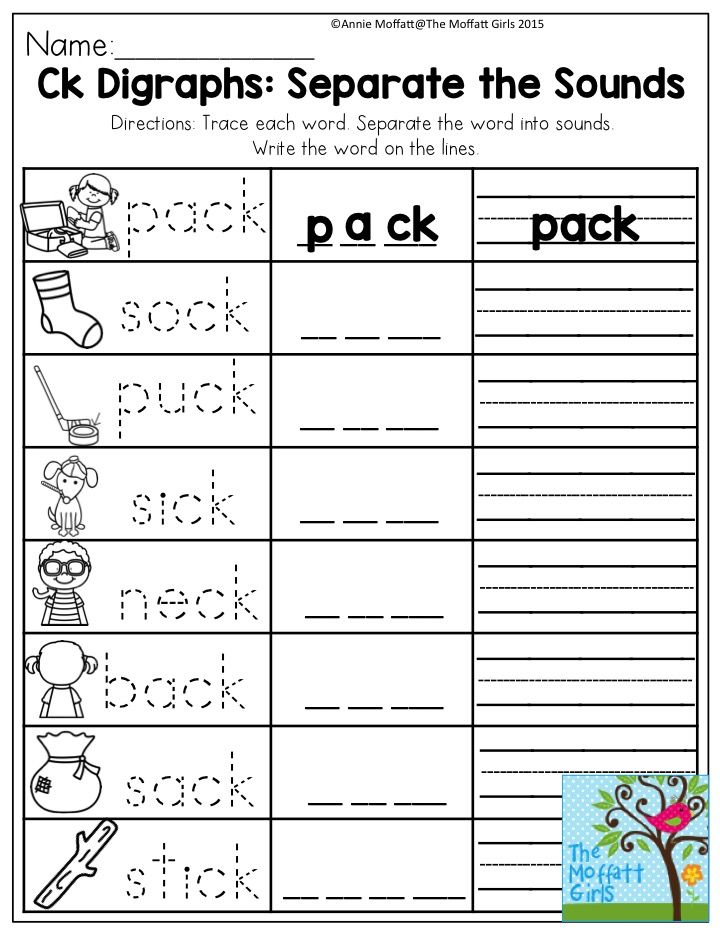

Phonics may sound a lot like phonological awareness. The two are related but not identical!

While phonological awareness refers to a generalized awareness of sounds and how they work within words (and outside of them as broader sounds), phonics deals specifically with letter sounds.

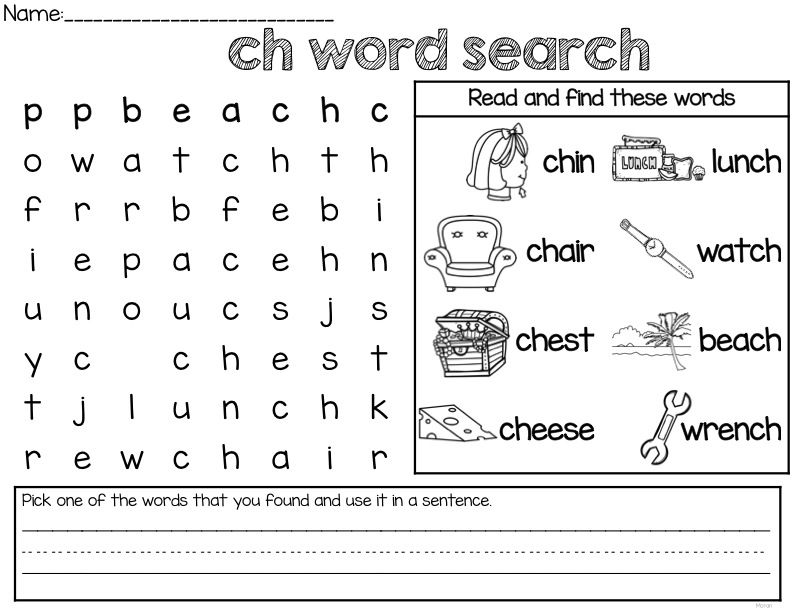

Phonics involves linking letters and combinations of letters with specific sounds. Children with a strong foundation in phonics can correctly and consistently link alphabetic letters with associated sounds to decode unfamiliar words.

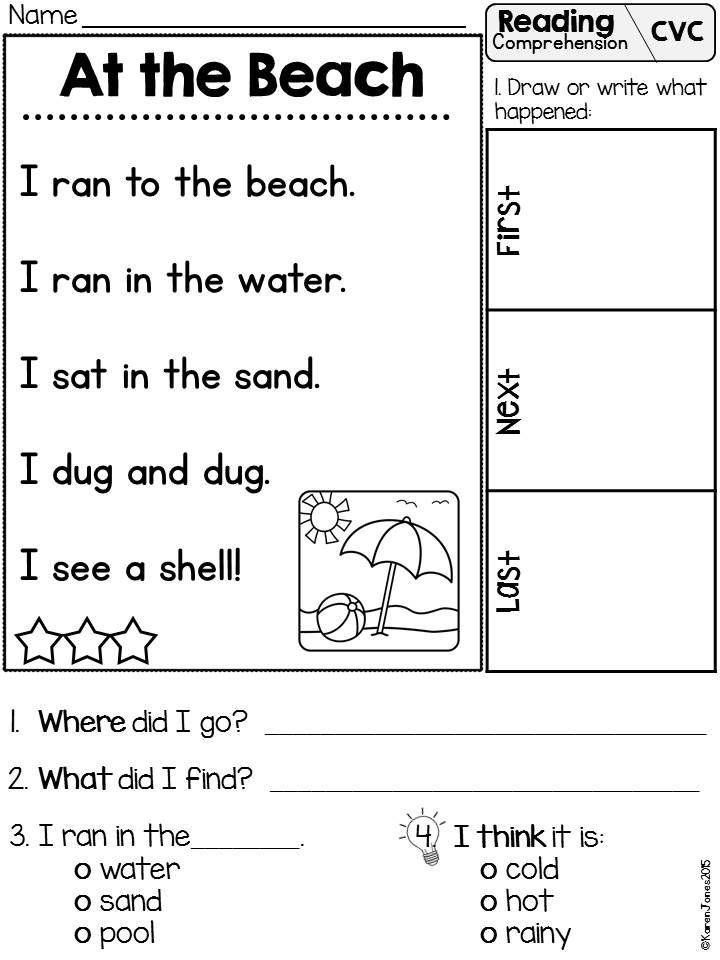

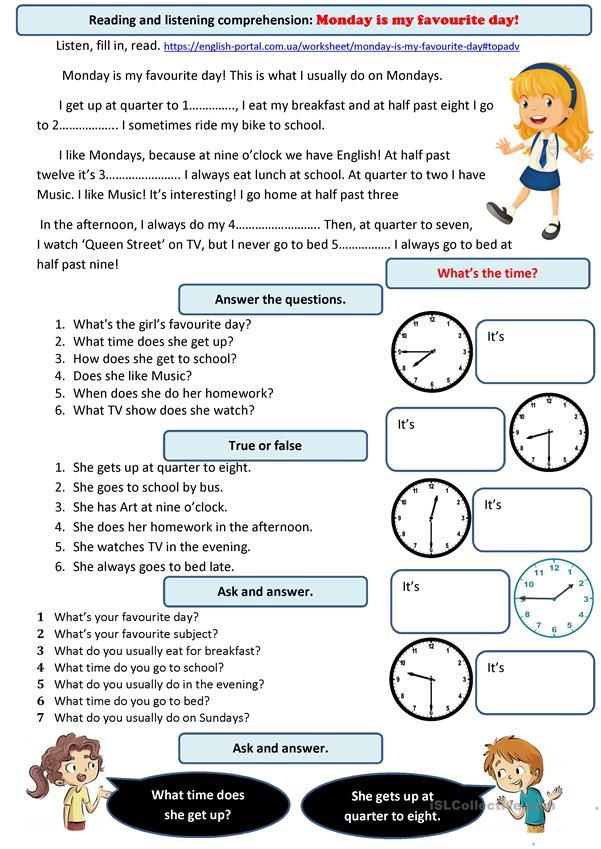

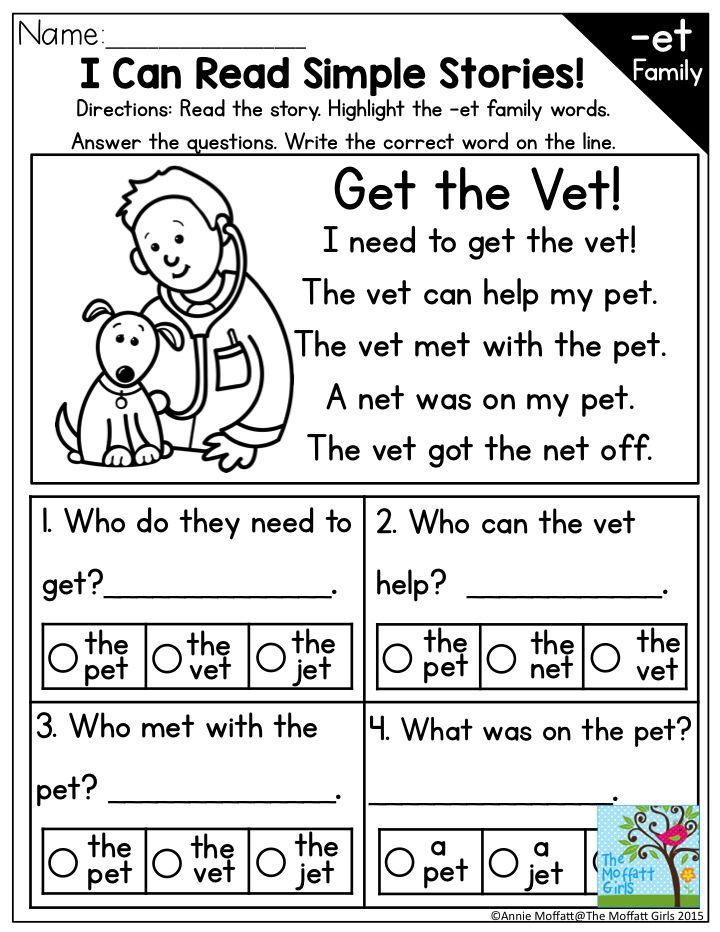

At the 1st-grade reading level, children are expected to use phonics to decode phonetically regular words.

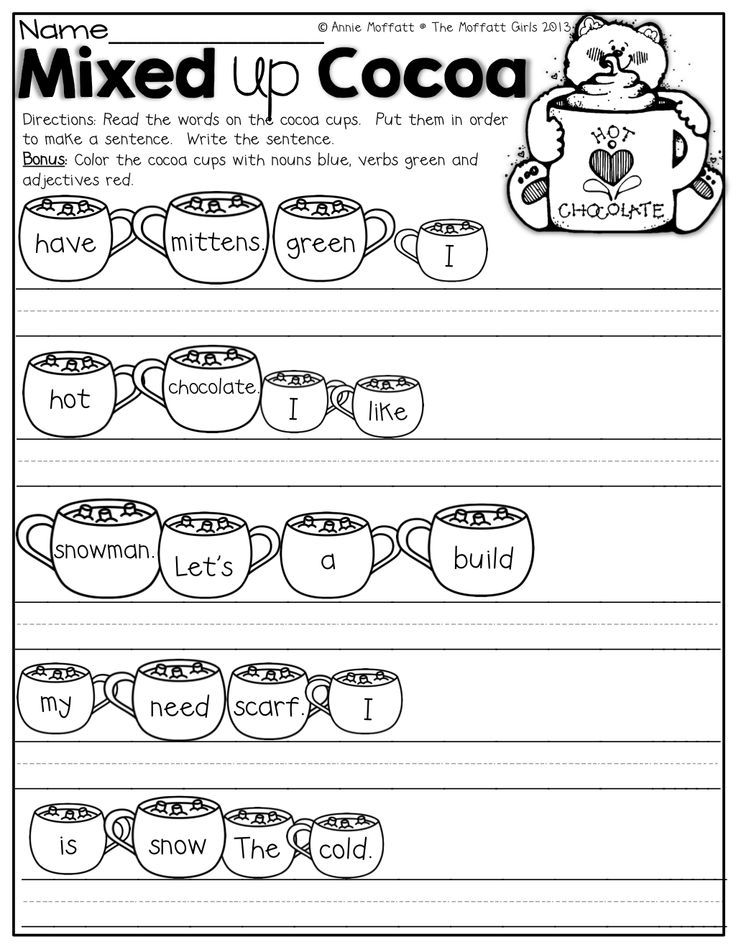

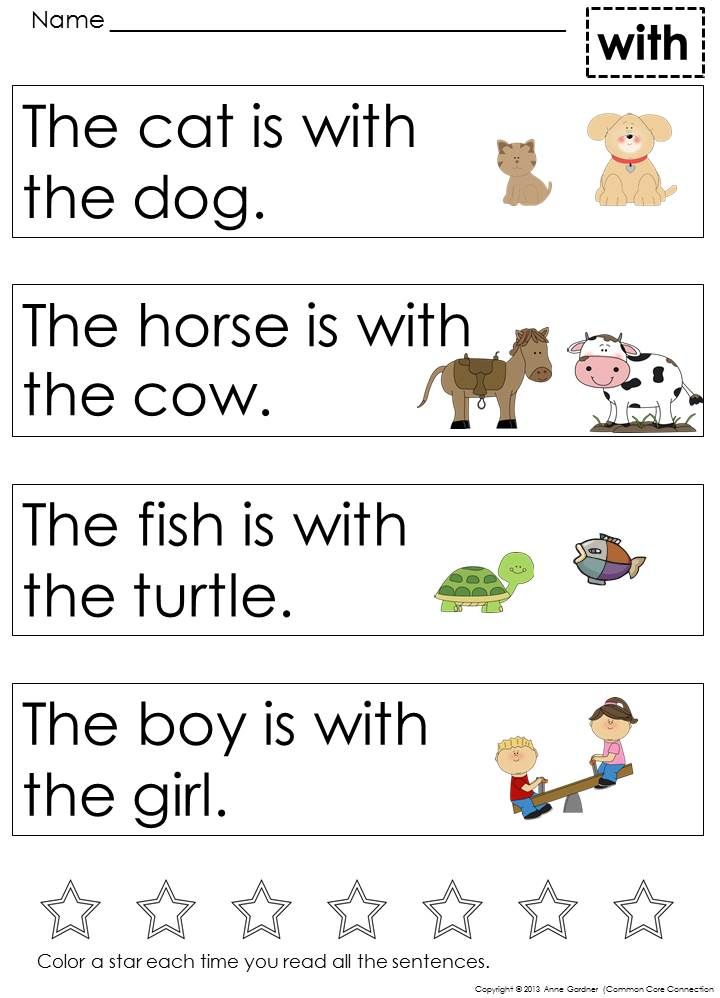

They will learn how to read words with short vowels (like cap and cub), words that use a silent E to create long sounds (like cape and cube), words with beginning and ending blends (like skunk and twist), and words with consonant digraphs (like mash and ship).

Through phonics, your child will begin to understand how essential vowels are to word formation. No matter how you slice it, every English word has at least one vowel sound. In fact, every syllable has a vowel sound — and only one vowel sound!

They’ll use these skills to break apart longer words into smaller, more manageable syllables. As your child becomes more comfortable decoding words, they’ll be able to apply the emotional inflection of a sentence (usually conferred by punctuation) while reading words.

Fluency

Fluent reading doesn’t mean your child can read anything on the market. It simply means that they are developing the ability to read with acceptable speed, accuracy, and expression at their determined reading level.

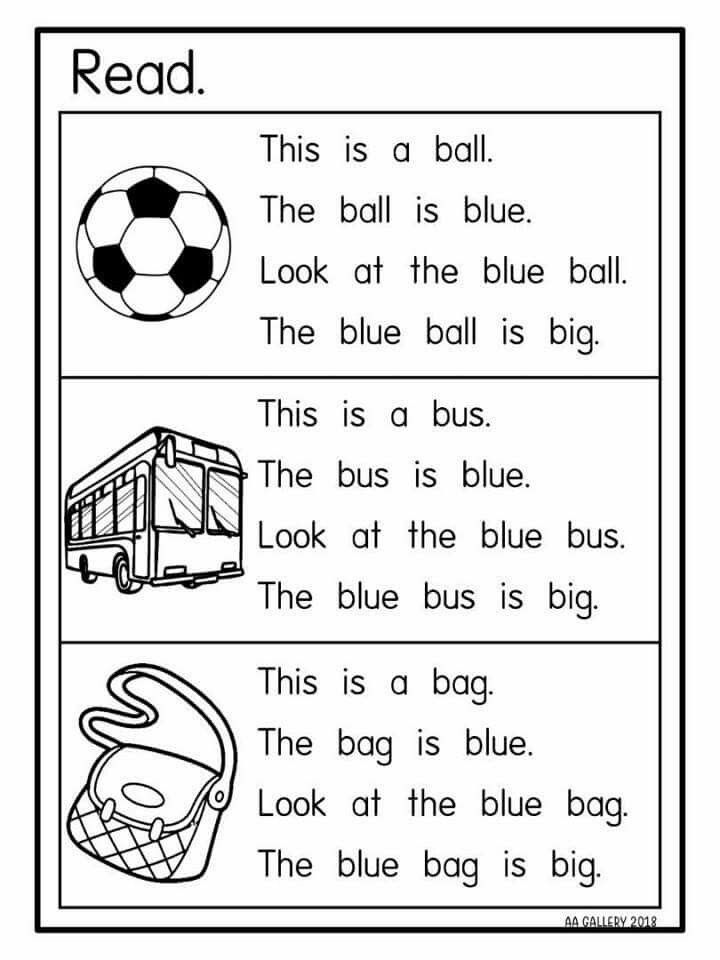

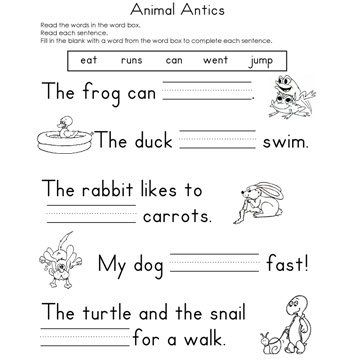

While reading, first-graders will appropriately utilize context clues and illustrations to aid the fluency of their reading. They’ll be able to understand almost anything that appears on the page (as long as the book is in their reading level!)

Their reading will feature emotional expression and, when applicable, slower moments when they need to sound out new, grade-appropriate words. The next time they revisit the story, they should read the word a little bit smoother!

The next time they revisit the story, they should read the word a little bit smoother!

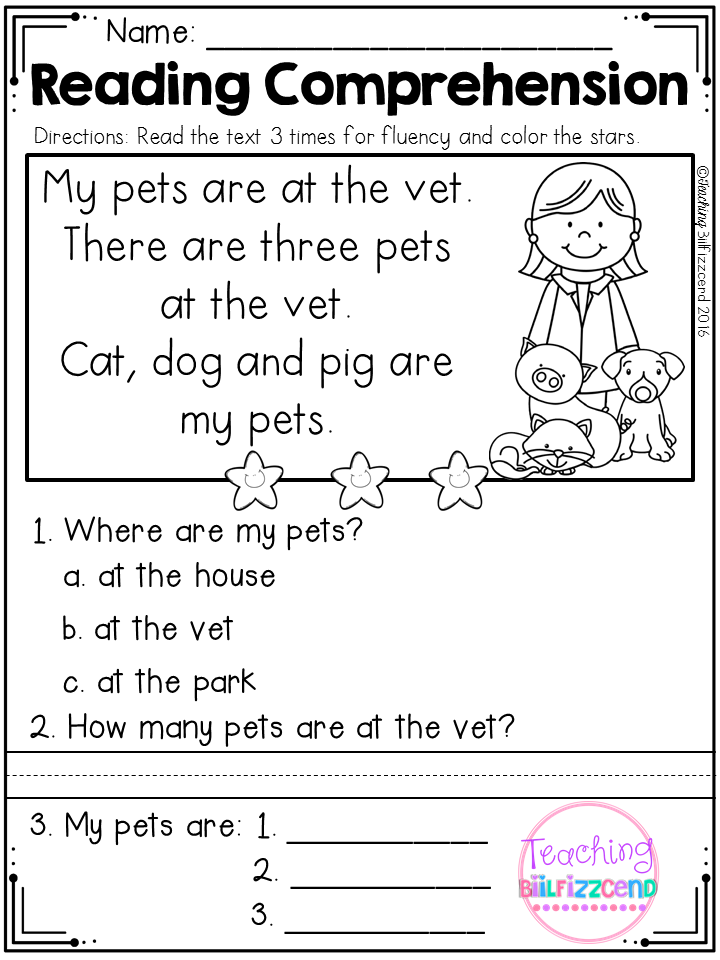

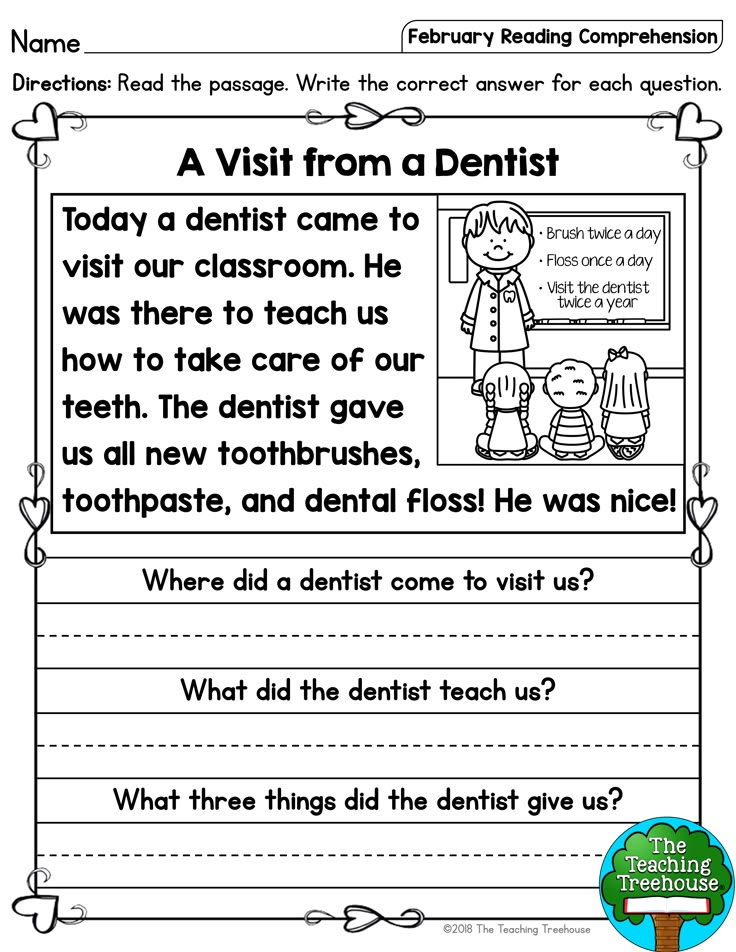

Comprehension

Your first-grader is starting to get a sense of how big the world around them really is (and how much bigger their imagination can be!).

This means that through reading and learning, they’ll gain a little bit more baseline knowledge of all sorts of subjects. This is what reading comprehension is all about!

Comprehension will help them remember what they’re reading as well as consider the goals of the text in front of them (is it for informing or entertaining?).

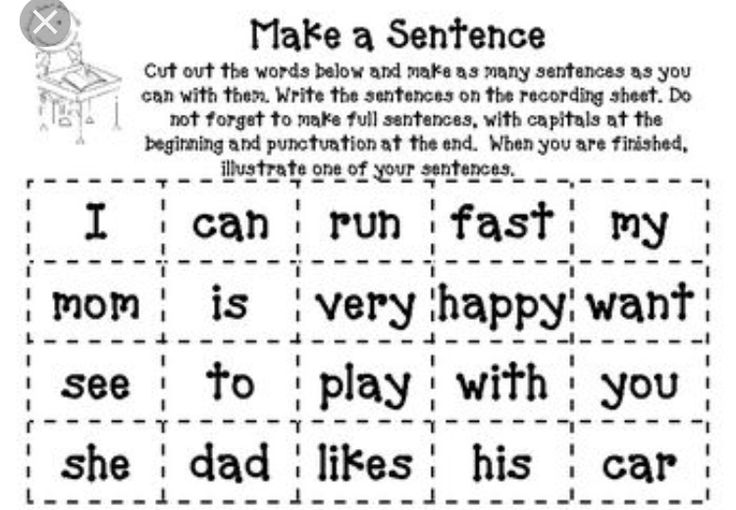

While reading, they’ll learn to identify words or phrases that suggest specific feelings, compare and contrast the experiences of different characters, and pinpoint the main character in the story.

They’ll be able to draw conclusions from these different sources of information and express opinions about what they uncover in the text. They may also begin to relate these thoughts and ideas to their own experiences.

Skills Needed To Master 1st Grade Reading

Before beginning 1st grade reading, your child will need to know some things to jump-start their new learning adventures.

Firm Grasp On Letters

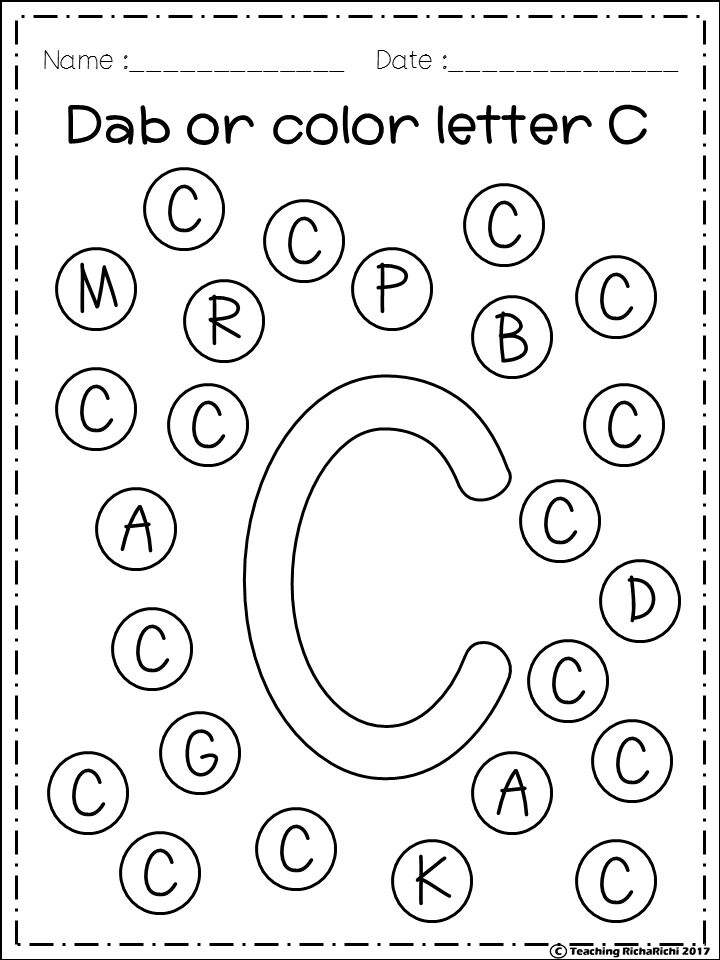

Ideally, your child will come into first grade with a strong grasp of the alphabet!

They should be able to not only recognize letters but correctly pair letters with the sounds they make. They should be able to differentiate between uppercase and lowercase letters, as well.

Your child may already know how to spell or read a few consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words, too. If not, there’s no need to worry! This is a skill they’ll work on more as they go through first grade.

For now, focusing on your child’s letter and letter-sound practice will get them primed for 1st grade reading.

Ability To Pinpoint Evidence

While reading, your child will probably express opinions about a character or plot point of the story. By first grade, they may be able to explain what gives them those opinions — in other words, identify evidence in a text.

We encourage you to give your child an extra nudge in the right direction by asking how they know what they know. You may be surprised to hear what they say!

This also gives you a chance to double-check that your child knows a text can give them all the evidence they need to support their conclusions.

Using Words To Express Ideas

What better way to use all the new words your child is learning than by expressing themselves?

The best way to help your child learn to use words to express ideas — and, as a result, prepare them for first grade — is to read and talk to them. Doing both allows you to help your child develop not just a love of reading but a strong desire to be a reader.

Talking with children also enhances their receptive language (their ability to understand what is said to them) and their expressive language (their ability to express their ideas accurately and thoughtfully).

It’s simple but so effective: taking the time to read to and have real conversations with your child can help their reading development so much!

Master 1st Grade Reading With HOMER

The skills your child learns as a first-grader will help them on their reading journey for the rest of their life. Not only that, but there is so much fun and excitement waiting for them just beneath those colorful covers!

Not only that, but there is so much fun and excitement waiting for them just beneath those colorful covers!

Getting the hang of the skills needed for 1st grade reading will take time, but with practice and patience, we know your child will get where they need to go!

And may they never forget that reading is one of the most exciting things they’ll ever learn how to do! It opens up a world of possibilities and imagination, all ready for their exploration anytime and anywhere.

We at HOMER hope that this guide has you feeling ready and relaxed about what your child will achieve during 1st grade reading lessons.

We’re always here to lend a helping hand in your child’s learning journey, especially through our Learn & Grow app. We want your child to feel like the whole world is at their fingertips, and with our personalized reading activities, it can be!

Author

Learning to read by syllables, we teach Russian alphabet for children

Home -forces and diploma

Reading and diploma

Course Learn the letter

View all

Letter A

letter B

letter B 9000 G

letter D

The letter E

The letter Y

The letter Zh

The letter Z

View all

Letters and sounds

View all0003

Recognize the letter from the sound (1)

Recognize the sound in the word

Distinguish letters

Upside down letters

Guess the sound from the letter

First and last sound in the word (1)

First and last sound in the word (1)

)

Do you know the alphabet?

View all

Reading syllables and words

View all

Reading verbs (1)

Reading verbs (2)

Making words (1)

Making words (2)

Slogo game (1)

Slogo game (2)

Slogo game (3)

Which syllable is extra? (1)

Which syllable is missing? (2)

View all

Read phrases and sentences

View all

Decoder

Simple offers (1)

Simple sentences (2)

View all

We develop speech

View all

Decoder

Learning prepositions

Simple sentences (1)

Study prepositions (2)

Simple sentences (2)

unfamiliar words 1 class

unfamiliar words 2 class

unfamiliar words 3 class

Steppower grade 4 class

View all

write competently

Stressed and unstressed vowels

ChA-SCHA combinations (1)

Zhi-Shi combinations (1)

Grammatical blitz (2)

Dictionary words (1)

Vowels after hard and soft consonants (2)

Vowels after hard and soft consonants (3)

Vowels after hard and soft consonants (4)

Write words from the text

View all

Parsing

View all

Letter and sound (1)

Letter and sound (2)

Letter and sound (3)

Letter and sound (4)

Major and minor members of a sentence (1)

Major and minor members of a sentence Grade 3

Division into syllables (1 ) 9Ol000

Pronoun (1)

Words-objects answering the questions who? What?

Words-objects, words-actions, words-signs

Noun

Modifiable and invariable nouns (1)

View all

Secrets of the Russian language

View all

Alphabet. Alphabetical order

Alphabetical order

Antonyms

Interrogative sentences (1)

Dialogue and monologue

Lying and deaf consonants at the end of the word

Noun

Board-Duel

Multiplying, borrowed words

View all

with literature

View all

Everything secret becomes clear

Reader's diary. A. Aleksin "In the land of eternal holidays"

Reader's diary. A. Volkov. Wizard of the Emerald City

Reader's diary. A. Gaidar "Chuk and Gek"

Reader's diary. A.P. Chekhov. "Kashtanka"

Reader's diary. A.S. Pushkin. "Ruslan and Lyudmila"

Reader's diary. A.S. Pushkin. The Tale of the Dead Princess...

Reader's diary. V. Gauf "Dwarf Nose" and "Little Muk"

Reader's diary. V. Kataev. Son of Regiment

View all

ABC online

View all

Tasks letter A

Tasks letter B

Tasks letter B

Tasks letter G

Tasks letter e

Tasks letter E

Tasks letter Z

Tasks letter Z

View all

Learn the alphabet

View all

Letter puzzles

Letters and sounds

Decoder

Do you know the alphabet?

Distinguishing letters

Distinguishing vowels and consonants

Distinguishing sounds in pictures (1)

Guess the sound from the letter

Learn the letter from the sound (1)

View all

First you need to understand that the child is ready for learning. This can be verified by the following indicators: - the child's speech is clear, without serious violations in pronunciation, the child does not "swallow" sounds during pronunciation; - there is the ability to see the text; there is an understanding that these are letters - not pictures, but symbols depicting sounds. It is believed that the ideal age for learning to read is 6 years old, but one must always understand that this age is determined individually. It is better to start learning to read by syllables in a playful way, getting acquainted with individual letters. It is better to do little by little, but regularly: 15 minutes daily will be enough. After getting acquainted with the letters, proceed to reading by syllables. Reading by syllables is a technique available to every adult, it does not require special training. But you can always choose lesser-known author's methods of teaching reading, carefully studying their features and reviews of other parents. Having folded the alphabet into syllables, you can proceed to compose simple words.

This can be verified by the following indicators: - the child's speech is clear, without serious violations in pronunciation, the child does not "swallow" sounds during pronunciation; - there is the ability to see the text; there is an understanding that these are letters - not pictures, but symbols depicting sounds. It is believed that the ideal age for learning to read is 6 years old, but one must always understand that this age is determined individually. It is better to start learning to read by syllables in a playful way, getting acquainted with individual letters. It is better to do little by little, but regularly: 15 minutes daily will be enough. After getting acquainted with the letters, proceed to reading by syllables. Reading by syllables is a technique available to every adult, it does not require special training. But you can always choose lesser-known author's methods of teaching reading, carefully studying their features and reviews of other parents. Having folded the alphabet into syllables, you can proceed to compose simple words. The main thing is not to force the process: when it is measured and regular, it is doomed to success!

The main thing is not to force the process: when it is measured and regular, it is doomed to success!

What is a syllable?

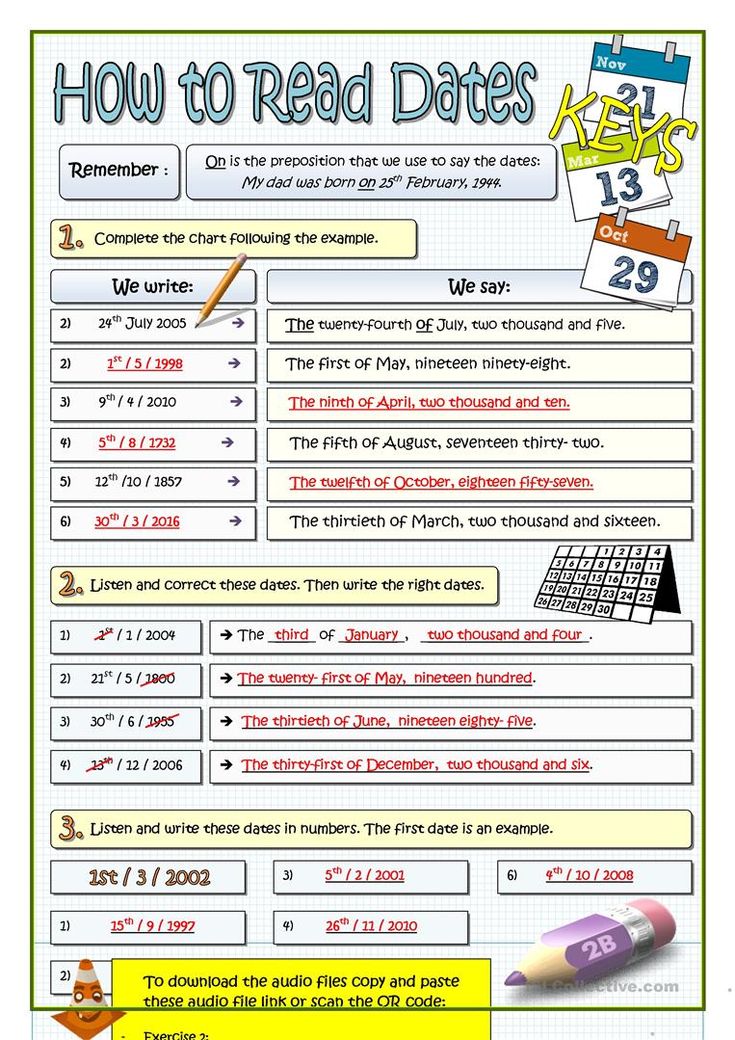

To successfully master the skill of reading, it is necessary to understand how to divide words into syllables. A syllable is one or more sounds uttered by one expiratory push of air. For a simple orientation, it can be taken as a rule that there are as many syllables in a word as there are vowels. Use our exercises, compiled by professional teachers, for a more effective acquaintance with this topic, so as not to confuse the concepts of "syllable division" and "word transfer".

How many words per minute should a first grader read?

The number of words read per minute, which can be used as a reference when assessing the quality of reading, is just one of the indicators. On average, the rate (or speed) of reading a first grade student is 15-25 words per minute. It is equally important to take into account qualitative indicators: how much the child understands the meaning of what is read, whether there is expressiveness when reading. To train the reading skill, it is important to be able to read not only aloud, but also silently, this is how awareness is born and further - the expressiveness of reading.

It is equally important to take into account qualitative indicators: how much the child understands the meaning of what is read, whether there is expressiveness when reading. To train the reading skill, it is important to be able to read not only aloud, but also silently, this is how awareness is born and further - the expressiveness of reading.

"The basics of literacy for preschool children are presented on our website with online exercises for learning letters, sounds, reading by syllables. Opportunities are presented for studying the alphabet, vowels and consonants and sounds, adding syllables, reading the first words and distinguishing sounds in words, taking into account the hobbies of a preschooler. Find matching words, play syllabic bingo, disenchant spelled words, and more! The lessons are equipped with bright and colorful pictures, illustrations understandable for the child, which will allow you to explore the magical world of letters and syllables in a playful way. "

"

Playful activities

Your child will have a fun and productive time.

Children are engaged with pleasure, are completely immersed in the learning process and achieve results. For children under 6 who have not yet learned to read, we voiced each task.

Cups and medals for children

Awards that motivate children to achieve success.

Each child has his own “hall of awards and achievements”. If the tasks are completed correctly, children receive cups, medals and nominal diplomas. The awards can be shared on social networks, and the diploma can be printed.

Personal training

Fully controlled development of the child.

We save all the successes of the child and show you what you should pay special attention to. Make up your own training programs so that the child develops harmoniously in all the right directions.

Start learning with your child

today - it's free

Register and get 20 tasks for free. To remove restrictions and achieve great results in your studies - choose and pay for the tariff plan that suits you.

Register orChoose a tariff

How to teach a child to read: techniques from an experienced teacher

At what age should one start teaching a child to read

Speech therapist Naya Speranskaya believes that the optimal age at which you can gradually start learning to read is 5.5 years.

“But still, the starting point for the first steps in this matter should not be a specific age, but the child himself. There are children who are ready to master the skill as early as 3-4 years old, and there are those who "mature" closer to grade 1. Once I worked with a boy who could not read at 6.5 years old. He knew letters, individual syllables, but he could not read. As soon as we began to study, it became clear that he was absolutely ready for reading, in two months he began to read perfectly in syllables, ”said Speranskaya.

How to teach a child to read quickly and correctly

The first thing you need to teach your baby is the ability to correlate letters and sounds. “In no case should a child be taught the names of letters, as in the alphabet: “em”, “be”, “ve”. Otherwise, training is doomed to failure. The preschooler will try to apply new knowledge in practice. Instead of reading [mom], he will read [me-a-me-a]. You are tormented by retraining, ”the speech therapist warned.

Therefore, it is important to immediately give the child not the names of the letters, but the sounds they represent. Not [be], but [b], not [em], but [m]. If the consonant is softened by a vowel, then this should be reflected in the pronunciation: [t '], [m'], [v '], etc.

To help your child remember the graphic symbols of letters, make a letter with him from plasticine, lay it out using buttons, draw with your finger on a saucer with flour or semolina. Color the letters with pencils, draw with water markers on the side of the bathroom.

“At first it will seem to the child that all the letters are similar to each other. These actions will help you learn to distinguish between them faster, ”said the speech therapist.

As soon as the baby remembers the letters and sounds, you can move on to memorizing syllables.

close

100%

How to teach your child to join letters into syllables

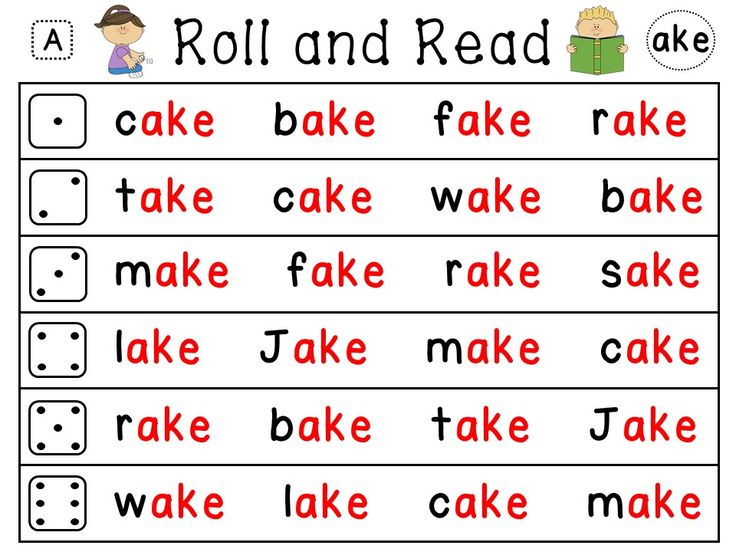

“Connecting letters into syllables is like learning the multiplication table. You just need to remember these combinations of letters, ”the speech therapist explained.

Naya Speranskaya noted that most of the manuals offer to teach children to read exactly by syllables. When choosing, two nuances should be taken into account:

1. Books should have little text and a lot of pictures.

2. Words in them should not be divided into syllables using large spaces, hyphens, long vertical lines.

“All this creates visual difficulties in reading. It is difficult for a child to perceive such a word as something whole, it is difficult to “collect” it from different pieces. It is best if there are no extra spaces or other separating characters in the word, and syllables are highlighted with arcs directly below the word, ”the speech therapist explained.

It is best if there are no extra spaces or other separating characters in the word, and syllables are highlighted with arcs directly below the word, ”the speech therapist explained.

According to Speranskaya, cubes with letters are also suitable for studying syllables - playing with them, the child will quickly remember the combinations.

Another way to gently help your child learn letters and syllables is to print them in large print on paper and hang them all over the apartment.

“Hang them on the refrigerator, on the board in the nursery, on the wall in the bathroom. When such leaflets are hung throughout the apartment, you can inadvertently return to them many times a day. Do you wash your hands? Read what is written next to the sink. Is the child waiting for you to give him lunch? Ask him to name which syllables are hanging on the refrigerator. Do a little, but as often as possible. Step by step, the child will learn the syllables, and then slowly begin to read,” the specialist said.

Speranskaya is sure that in this way the child will learn to read much faster than after daily classes, when parents seat the child at the table with the words: "Now we will study reading ..."

“If it is really difficult for you to give up such activities, then pay attention that the nervous system of preschoolers is not yet ripe for long and monotonous lessons. Children spend enormous efforts on the analysis of graphic symbols. Learning to read for them is like learning a very complex cipher. Therefore, it is necessary to observe clear timing in such classes. At 5.5 years old, children are able to hold attention for no more than 10 minutes, at 6.5 years old - 15 minutes. That's how long one lesson should last. And there should be no more than one such “lessons” a day, unless, of course, you want the child to lose motivation for learning even before school,” the speech therapist explained.

How to properly explain to a child how to divide words into syllables

When teaching a child to divide words into syllables, use a pencil. Mark syllables with a pencil using arcs.

Mark syllables with a pencil using arcs.

close

100%

“Take the word dinosaur. It can be divided into three syllables: "di", "but", "zavr". The child will read the first syllables without difficulty, but it will be difficult for him to master the third. The kid cannot look at three or four letters at once. Therefore, I propose to teach to read not entirely by syllables, but by the so-called syllables. This is when we learn to read combinations of consonants and vowels, and we read the consonants separately. For example, we will read the word "dinosaur" like this: "di" "but" "for" "in" "p" The last two letters are read separately from "for". If you immediately teach a child to read by syllables, he will quickly master complex words and move on to fluent reading, ”the speech therapist is sure.

In a text, syllables can be denoted in much the same way as syllables. Vowel + consonant with the help of an arc, and a separate consonant with the help of a dot.

Naya Speranskaya gave parents a recommendation to memorize syllables/syllable fusions for as long as possible, and move on to texts only when the child suggests it himself.