Parent cooperatives definition

Choosing a Cooperative — Parent Cooperative Preschools International

Taking part in a cooperative preschool allows you to be directly involved with your child’s early education. Being able to supervise your child, and the teacher, guarantees your child is safe and with the best teachers anywhere. Interacting with a community of other parents who share your commitment to childhood and receiving modeling by the teacher as you help, gives you opportunities to learn alongside your child. Most importantly, choosing a cooperative preschool gives you extra time to bond with your child and create memories together. Your child will always know that education is important in your family because you live it everyday.

How a Cooperative Works

A parent cooperative preschool is organized by a group of families with similar philosophies who hire a trained teacher to provide their children with a quality preschool experience. The preschool is administered and maintained by the parents.

The parents assist the professional teachers in the classroom on a rotating basis and participate in the educational program of all the children. Each family shares in the business operation of the school (usually a nonprofit venture), thus making it truly a cooperative venture. Parents, preschool children and their teachers all go to school together and learn together.

For Parents

Parents gain insight into child behavior by observing other children. They observe how other parents and the professional teachers handle various situations and gain greater understanding and enjoyment of their own children through active participation in their education. They have the opportunity to share their experiences and expertise with others while working together in a cooperative setting. Through serving on the Board, parents learn about administration, running meetings and other skills useful to them in other areas and states of their lives. They also learn useful ideas for helping their children at home and in the world around them. .

.

For Children

Children participate in a supervised play and learning experience with children of their own age. Equipment, materials and physical facilities are scaled to child size. An opportunity is provided to interact with adults other than their own parents. The children are able to find security and a feeling of belonging in a world which is non-threatening and interested in them. Learning to respect and accept the rights and differences of others is emphasized. Children have hands-on experiences in creative arts, music, science, literature, and language geared to their needs and developmental level.

For the Community

Parents and children develop an extended family with friendships they carry through their lives. Parents gain a strong sense of responsibility and develop positive self worth which carries over into every aspect of community life. The cooperative organization provides preschool experiences within the financial means of most families.

A Family of Families

Potential Through Play

Cooperative Models

Childcare Co-ops | California Center for Cooperative Development

General InfoChildcare and preschool cooperatives can be organized in a variety of ways. Workers can form a cooperative to offer childcare or preschool services (see worker cooperative).

Workers can form a cooperative to offer childcare or preschool services (see worker cooperative).

Parent Cooperatives

Parents are attracted to childcare and preschool cooperatives because they offer high quality, affordable early education for children. The cooperative is led by a parent-elected Board of Directors who establishes policies and hire and oversee qualified staff who run the day-to-day operations. Parents often contribute volunteer hours to the cooperative. This involvement reduces overhead costs and allows parent input and intimate knowledge regarding their child’s out-of-home experiences, as well as opportunities to interact with other parents.

Preschool cooperatives, sometimes referred to as Parent Participation Nursery Schools (PPNS), date back to 1916 when a group of mothers at the University of Chicago organized a cooperative program to provide social and educational experiences for their young children, and to gain child-free time to pursue volunteer activities. Contemporary preschool cooperatives offer similar enrichment activities for preschoolers; many offer the option of extended childcare hours for parents who are employed. The program is licensed and staffed by one or more experts in early childhood education. Parent involvement contributes to the quality of the program and also reduces operational costs.

Contemporary preschool cooperatives offer similar enrichment activities for preschoolers; many offer the option of extended childcare hours for parents who are employed. The program is licensed and staffed by one or more experts in early childhood education. Parent involvement contributes to the quality of the program and also reduces operational costs.

Childcare cooperatives offer quality care for children while their parents work. Although many aspects of childcare cooperatives are identical to preschool cooperatives, they usually differ in three significant ways: they offer full day care, staff provide a larger portion of the care provided, and parent participation requirements are significantly reduced.

A growing number of preschool cooperatives are modifying or offering options to their programs to accommodate employed parents. Many offer “after preschool” childcare options, some allow nannies or grandparents to complete the parent participation requirements, or participation options that can be completed during evening or weekend time. Other programs offer members the option of reducing their parent participation requirements by paying an increased fee.

Other programs offer members the option of reducing their parent participation requirements by paying an increased fee.

Employer-Assisted Cooperative Childcare

The cooperative can be a useful model for on or near worksite childcare. In the employee model, parents at the worksite are the members and elect the board of directors. The center operates almost identical to the parent childcare cooperative described earlier. The employer may assist the cooperative by helping with start-up expenses, contributing financially or by providing in-kind assistance like utilities, use of buildings and outdoor space, duplicating, secretarial, and/or other goods or services.

In a child-care consortium, businesses, rather than parents, are the members and they join together to provide near worksite childcare for their employees. In this model, the board is primarily composed of member-business representatives (who may also be parents). Business members share the costs and benefits associated with the program and typically charge fees to employee-parents using the center.

Babysitting Co-ops

Babysitting cooperatives allow parents to equitably exchange baby-sitting services so they can enjoy a night out or travel on business trips. These cooperatives are less formal and involve relatively short-term arrangements. When parents take care of a child(ren) from a member family they earn points or scrip that can be “spent” when they need baby-sitting services.

Housing and construction cooperatives

The Civil Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as the Civil Code of the Russian Federation) recognizes a housing or housing-construction cooperative as a voluntary association of citizens and (or) legal entities on the basis of membership in order to meet the needs of citizens in housing, as well as manage residential and non-residential premises in a cooperative house. Among other things, the Civil Code of the Russian Federation establishes that housing and housing-construction cooperatives are consumer cooperatives. Therefore, the provisions on consumer cooperatives apply to the regulation of their activities. It should be pointed out that a consumer cooperative is a voluntary association of citizens and legal entities on the basis of membership in order to meet the material and other needs of the participants, carried out by combining property shares by its members. In the legal literature, this definition is clarified by indicating the fact that the initial property of the cooperative consists of shares.

Therefore, the provisions on consumer cooperatives apply to the regulation of their activities. It should be pointed out that a consumer cooperative is a voluntary association of citizens and legal entities on the basis of membership in order to meet the material and other needs of the participants, carried out by combining property shares by its members. In the legal literature, this definition is clarified by indicating the fact that the initial property of the cooperative consists of shares.

The consumer cooperative is a non-profit organization, i.e. a legal entity that does not pursue profit as the main goal of its activities. A consumer cooperative has the right to carry out entrepreneurial activity only insofar as it serves to achieve the goals for which it was created, and insofar as such activity corresponds to the specified goals.

Unlike other types of non-profit organizations, a consumer cooperative has the right to distribute the profits received among its members in accordance with the law and the charter of the cooperative. All other non-profit organizations are not entitled to distribute profits from entrepreneurial activities among their participants (members). In addition, the goals of creating a consumer cooperative are not aimed at achieving any public benefits, as in most non-profit organizations, but are related to meeting the needs of members of the cooperative.

All other non-profit organizations are not entitled to distribute profits from entrepreneurial activities among their participants (members). In addition, the goals of creating a consumer cooperative are not aimed at achieving any public benefits, as in most non-profit organizations, but are related to meeting the needs of members of the cooperative.

The legislation for housing and housing-construction cooperatives establishes a single regulatory definition. At the same time, the features of these two types of cooperatives lie in the fact that members of a housing cooperative participate with their own funds in the construction, reconstruction and subsequent maintenance of an apartment building, while members of a housing cooperative finance the acquisition and maintenance of an already completed apartment building, as well as, if necessary, its reconstruction.

Citizens and (or) legal entities have the right to join housing and housing-construction cooperatives. Citizens with the right to join a cooperative can only be those individuals who have reached the age of 16 years. At the same time, the poor and other citizens who, on the grounds established by the Code, are recognized as in need of improved housing conditions, have a priority right to join the cooperative. However, this right arises for such citizens in relation not to any housing and housing cooperatives, but only in relation to those of them that are organized with the assistance of federal or regional state authorities or local governments.

Citizens with the right to join a cooperative can only be those individuals who have reached the age of 16 years. At the same time, the poor and other citizens who, on the grounds established by the Code, are recognized as in need of improved housing conditions, have a priority right to join the cooperative. However, this right arises for such citizens in relation not to any housing and housing cooperatives, but only in relation to those of them that are organized with the assistance of federal or regional state authorities or local governments.

The right to join housing and housing-construction cooperatives equally belongs to citizens of the Russian Federation, foreign citizens and stateless persons who have reached the established age.

Legal entities that have the right to join housing and housing-construction cooperatives can be both commercial and non-commercial organizations. At the same time, it is advisable to take into account that the participation of certain types of legal entities in other commercial and non-commercial organizations may be made dependent on the observance of certain conditions by law.

Management bodies in housing and housing-construction cooperatives are:

- general meeting of members of the cooperative;

- conference, if the number of participants in the general meeting is more than 50 and this is provided for by the charter of the cooperative;

- board and chairman of the board of the cooperative.

The general meeting (conference) is the supreme governing body of the cooperative. Let us note that if the number of participants in the general meeting is more than 50, then it is not at all necessary that the functions of the supreme governing body are vested in the conference. This does not happen automatically, but only if such a body is provided for by the charter of the cooperative.

The Board is a collegial executive body of the cooperative, accountable to the general meeting of members of the cooperative (conference). The board of a housing cooperative is elected from among the members of the relevant cooperative by the general meeting of members of the housing cooperative (conference). The board manages the current activities of the cooperative, elects the chairman of the cooperative from among its members and exercises other powers that are not referred by the charter of the cooperative to the competence of the general meeting (conference).

The board manages the current activities of the cooperative, elects the chairman of the cooperative from among its members and exercises other powers that are not referred by the charter of the cooperative to the competence of the general meeting (conference).

The chairman of the board is the sole executive body of the cooperative, elected by the board from among its members for a period determined by the charter of the cooperative. This body ensures the implementation of the decisions of the board; acts on behalf of the cooperative without a power of attorney, including representing its interests and making transactions; exercises other powers that are not referred by the Code or the charter of the cooperative to the competence of the general meeting of members of the cooperative (conference) or the board of the cooperative.

The supervisory body in any housing and housing-construction cooperatives is the audit commission (auditor). This body is not among the governing bodies of the cooperative, since it does not carry out independent organizational and executive and administrative activities, but implements only one specific management function - control over the financial and economic activities of the cooperative, the so-called internal audit.

The audit commission (auditor) of a housing cooperative is elected for a period of not more than three years by the general meeting of members of the cooperative (conference). The number of members of the audit commission of a housing cooperative is determined by the charter of the cooperative. Members of the audit commission cannot simultaneously be members of the board of a housing cooperative, as well as hold other positions in the management bodies of a housing cooperative.

The audit commission of a housing cooperative elects the chairman of the audit commission from among its members.

The election of an audit commission (auditor) is mandatory in all housing and housing-construction cooperatives.

From the theory of cooperatives to cooperative practice - Monthly reviews / Blog. Bank of social ideas.

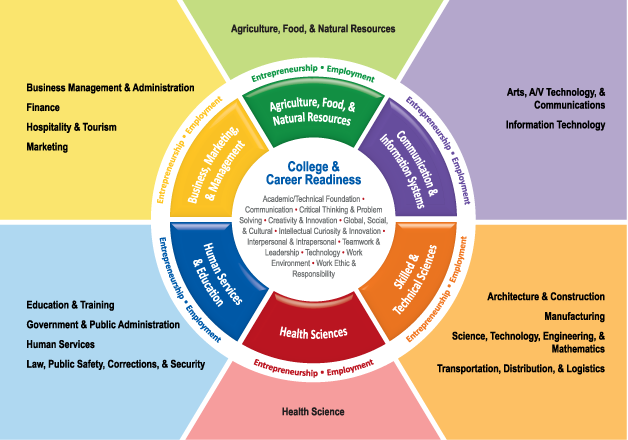

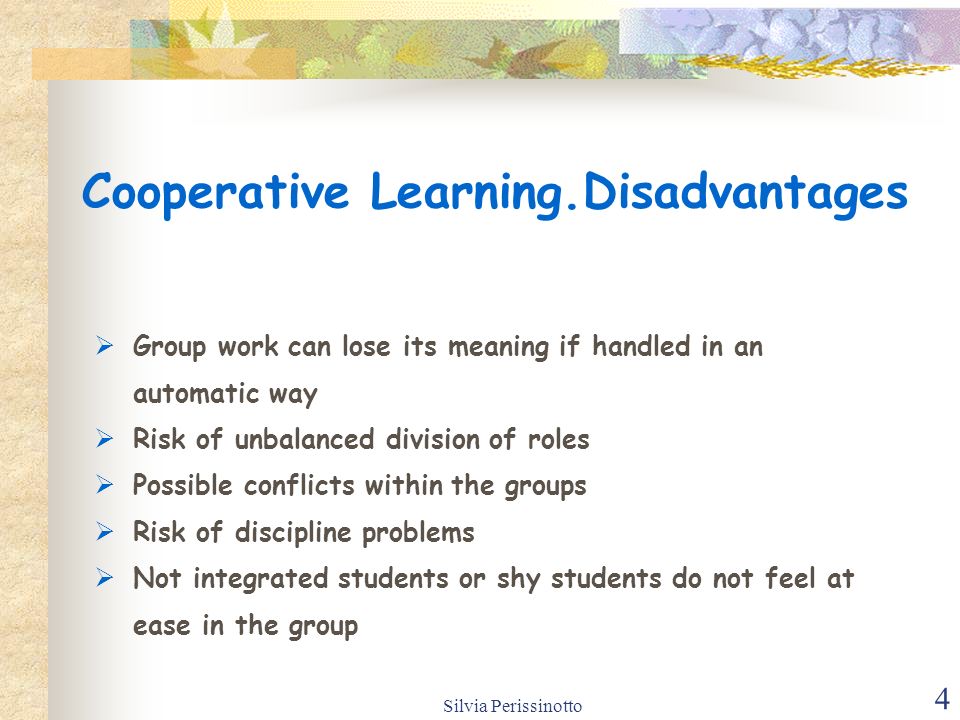

The concept of "collaboration" ("cooperation") has two different meanings. In the broadest sense, according to the definition of economists and sociologists, this concept is associated with the coordinated activity of agents pursuing various goals and striving to establish general rules. In the narrow sense of the word, according to the definition of the cooperative movement, it refers to the institutionalized activities of cooperative enterprises. As stated below, cooperative enterprises, in order to survive and develop, should combine narrow and broad senses. A review of how cooperatives developed in the second half of the 20th century shows that many of them followed the most common practice. However, around 2000, the trend reversed. Cooperatives small and large, young and old, started by rethinking their founding values and based their development on new shared experiences. These innovations are directly related to the growth of membership participation. To attract participating members was more sustainable, it should be supported by the cooperatives, in particular through the creation of a membership initiative. Ultimately, collaboration is an act of mutual learning that results in innovation and democratic forms of governance.

In the narrow sense of the word, according to the definition of the cooperative movement, it refers to the institutionalized activities of cooperative enterprises. As stated below, cooperative enterprises, in order to survive and develop, should combine narrow and broad senses. A review of how cooperatives developed in the second half of the 20th century shows that many of them followed the most common practice. However, around 2000, the trend reversed. Cooperatives small and large, young and old, started by rethinking their founding values and based their development on new shared experiences. These innovations are directly related to the growth of membership participation. To attract participating members was more sustainable, it should be supported by the cooperatives, in particular through the creation of a membership initiative. Ultimately, collaboration is an act of mutual learning that results in innovation and democratic forms of governance.

Cooperation: an alternative and/or reform?

What is cooperation? What gives the co-operative movement its distinct identity, regardless of the legal basis? The answer to this question is of interest not only to the cooperative movement, but to the entire social economy and the third sector. Our the hypothesis is that the social economy is based on cooperation.

Our the hypothesis is that the social economy is based on cooperation.

In 1844, Robert Owen defined cooperation as the opposite of conflict and capitalist competition. While the terms “cooperation” and “competition” may be opposites, in reality the difference between cooperatives and ordinary companies cannot be described in terms of mere opposition. Cooperatives are involved both in the creation of an alternative and in the functioning of the capitalist economy. How do they do it? Social and economic injustice, symbolic the violence and selfishness that the capitalist economy brings, and the pressure that this economy is likely to exert on government, including democratic government, give an idea of the magnitude of the challenge that is the opportunity to build a democratic economic alternative.

To answer these questions, we need to look again at the meaning of the word “cooperation”. This word has two main uses. We believe that the cooperative movement must embrace both meanings of cooperation if it is to achieve economic success without betraying their ethical principles.

The general meaning of cooperation

The term “cooperation” first appeared in the fourteenth century. Word derived from Christian Latin cooperation (cooperatio) , in the fifteenth century meant a common cause, consisted of co- and meant “with” or “together” and operare, i.e. "act". Thus, cooperation is a joint action, the unification of individual efforts to achieve a common goal. In general, collaboration refers to any kind of joint work. between individuals or groups, voluntary or otherwise. Often used in the literature on sociology, economics and management, especially in the fields of work, in organizations and in firms, the concept of cooperation is especially relevant in dealing with issues related to with the forms of labor collectives. Although it is “one of the main problems of all communities” (Dadoy, 1999), this general meaning of the term, which is by far the most common, however, is often used implicitly. This the meaning of the term is hidden in a number of words that are associated with the idea of cooperation. Communication, collaboration, coordination, participation, mediation, interaction and collective action are classical terms in sociology, usually implying indirect way, cooperation.

Communication, collaboration, coordination, participation, mediation, interaction and collective action are classical terms in sociology, usually implying indirect way, cooperation.

Its use was widespread during the industrial revolution, and since the nineteenth century, the concept of cooperation has been used in the wider context of society and work organization. In the first volume Capital , Part IV, Chapter XIII, entitled Collaboration , Marx wrote: "When several workers work together to achieve a common goal in the same process of production or in different but related processes, their work takes the form of cooperation" (Marx, 1867, p.863). Marx showed the advantages of "working in collaboration" and added that it increases with the concentration of capital: “The number of workers who cooperate, or, in other words, the extent of cooperation, depends primarily on the amount of capital advanced to acquire labor power” (ibid. , p. 868). Marx also wrote about this dependence: “If capitalist control is essentially two-sided, due to the two-sided nature of the controlled object, which, on the one hand, is the process of cooperative production, and, on the other hand, it is a way of extracting surplus value, then the form of this control is purely despotic” (ibid., p.871). Therefore, Marx emphasized the contradiction between the process of cooperative production, which requires that workers agreed with the goals of entrepreneurship, and the extraction of surplus value, which is contrary to their interests. But he did not continue to do this further, in particular, with cooperatives that tried to overcome this contradiction. We know that Marx was well aware of the existence of labor cooperatives, but he made no reference to them in his theoretical discussion of cooperation. This silence is all the more surprising given that Marx distinguished between “ simple cooperation” in work in pre-capitalist societies, which was based on " joint ownership of the means of production " and " capitalist cooperation ", " the productive power of capital ".

, p. 868). Marx also wrote about this dependence: “If capitalist control is essentially two-sided, due to the two-sided nature of the controlled object, which, on the one hand, is the process of cooperative production, and, on the other hand, it is a way of extracting surplus value, then the form of this control is purely despotic” (ibid., p.871). Therefore, Marx emphasized the contradiction between the process of cooperative production, which requires that workers agreed with the goals of entrepreneurship, and the extraction of surplus value, which is contrary to their interests. But he did not continue to do this further, in particular, with cooperatives that tried to overcome this contradiction. We know that Marx was well aware of the existence of labor cooperatives, but he made no reference to them in his theoretical discussion of cooperation. This silence is all the more surprising given that Marx distinguished between “ simple cooperation” in work in pre-capitalist societies, which was based on " joint ownership of the means of production " and " capitalist cooperation ", " the productive power of capital ". In addition, the question of difficult relationships Marx with the cooperative movement is another topic that we will deal with later. Marx used a different, more militant style of argument to comment on the cooperative movement, but in his economic writings he used the general meaning of this term, which is used within the framework of the organization of the workflow. He concluded his discussion by saying that "collaboration appears as a specific mode of capitalist production."

In addition, the question of difficult relationships Marx with the cooperative movement is another topic that we will deal with later. Marx used a different, more militant style of argument to comment on the cooperative movement, but in his economic writings he used the general meaning of this term, which is used within the framework of the organization of the workflow. He concluded his discussion by saying that "collaboration appears as a specific mode of capitalist production."

Half a century later, Frederick Winslow Taylor used the term "collaboration" to describe the relationship between workers and employers. As we know, Taylor wanted to develop a system for managing companies that would eliminate conflict. between employers and workers, and thus lead to improved productivity both quantitatively and qualitatively, leading to shared prosperity. In Marxist terms, this means reducing the contradiction between the production process and extraction of surplus value. It is interesting to see how collaboration again plays an important role in Taylor's work. Taylor's "scientific management system" depends on how workers and employers change their mental attitudes and realize that they duty is to cooperate in order to obtain the highest possible profit (Taylor, 19eleven). However, the most difficult thing was for the workers to get rid of the existing antagonism and mistrust with cooperation and mutual assistance, and they clearly practiced "dodging work" (Taylor's main concern), which was clearly the result of conflict between employers and employees. Unlike Marx, Taylor's use of the term "collaboration" refers to the organization of enterprise, rather than the labor process.

Taylor's "scientific management system" depends on how workers and employers change their mental attitudes and realize that they duty is to cooperate in order to obtain the highest possible profit (Taylor, 19eleven). However, the most difficult thing was for the workers to get rid of the existing antagonism and mistrust with cooperation and mutual assistance, and they clearly practiced "dodging work" (Taylor's main concern), which was clearly the result of conflict between employers and employees. Unlike Marx, Taylor's use of the term "collaboration" refers to the organization of enterprise, rather than the labor process.

Marx's theories were strong, but so was Taylor's praxeology. The "collaboration" that Taylor spoke of will prevail, even if this dominance was not achieved through Taylor's scientific management system, but rather through compromise, a compromise that workers often had to fight for. The term “cooperation” was omitted from the analysis of the employer-employee relationship and correctly replaced by “compromise”.

In 1893, Émile Durkheim published The division of labor in society . The concept of social solidarity is central to Durkheim's thought because his analysis was sociological rather than economic, and the term "solidarity" had ethical implications. effects. By the end of the nineteenth century, the study of economics had already turned its back on ethics, leaving the way open for sociology. Durkheim showed that society was, in fact, the birthplace of ethics. The division of labor led to solidarity because what is it “ created among men a whole system of rights and obligations which bound them together firmly ” (Durkheim, 1893, p. 403). The assertion that solidarity includes or presupposes cooperation does not contradict Durkheim's theory. Emphasizing solidarity, Durkheim gave cooperation an ethical basis that would suit the cooperative movement. He also endowed it with a deterministic dimension that goes against the founding principle of the cooperative: the right to join or leave the cooperative. is voluntary. Since Durkheim, almost all sociologists have analyzed collaboration from a functional, structural, and/or systemic point of view, and as a conscious and intentional practice. Parsons extended the use of the concept of cooperation, showing that every social organization was a system of cooperative relations. Later, the understanding of cooperation became more concise and heuristic in works on industrial democracy. " Collective functioning based on communication, self-expression and power of individual subjects ” opposed Taylor's “ rationality ” (Sainsaulieu, Tixier and Marty, 1983, p. 238). However, Reynaud questioned whether the impact of industrial democracy is limited by that these experiments “ seriously underestimated the nature and importance of existing power relations ” (Reynaud, 1988, p.12). Using a similar approach, Aoki identifies a cooperative organization with a hierarchical organization, first based on base “ horizontal coordination ”, and secondly, on “ top-down planning ” (Aoki, 1991).

is voluntary. Since Durkheim, almost all sociologists have analyzed collaboration from a functional, structural, and/or systemic point of view, and as a conscious and intentional practice. Parsons extended the use of the concept of cooperation, showing that every social organization was a system of cooperative relations. Later, the understanding of cooperation became more concise and heuristic in works on industrial democracy. " Collective functioning based on communication, self-expression and power of individual subjects ” opposed Taylor's “ rationality ” (Sainsaulieu, Tixier and Marty, 1983, p. 238). However, Reynaud questioned whether the impact of industrial democracy is limited by that these experiments “ seriously underestimated the nature and importance of existing power relations ” (Reynaud, 1988, p.12). Using a similar approach, Aoki identifies a cooperative organization with a hierarchical organization, first based on base “ horizontal coordination ”, and secondly, on “ top-down planning ” (Aoki, 1991). The issue of cooperative action can also be at least partially studied sociologically by developing “ systems specific actions ” (Crozier and Friedberg, 1977), as well as by using convention theory to study the relationship of the underlying causes of behavior. These and other approaches related to the sociology of work, sociology of organizations and socio-economic aspects of the firm, do not in any way form an indivisible whole, but they all define cooperation in relation to the organization of the work process. Finally, the term “collaboration” is always used in a general sense (see, for example, Amadieu, 1993, and Bernoux, 1995). Cooperation in this general sense can be defined as the coordinated activity of agents pursuing different goals and aimed at establishing common rules.

The issue of cooperative action can also be at least partially studied sociologically by developing “ systems specific actions ” (Crozier and Friedberg, 1977), as well as by using convention theory to study the relationship of the underlying causes of behavior. These and other approaches related to the sociology of work, sociology of organizations and socio-economic aspects of the firm, do not in any way form an indivisible whole, but they all define cooperation in relation to the organization of the work process. Finally, the term “collaboration” is always used in a general sense (see, for example, Amadieu, 1993, and Bernoux, 1995). Cooperation in this general sense can be defined as the coordinated activity of agents pursuing different goals and aimed at establishing common rules.

At the same time, for more than a century and a half, the concept of cooperation has been widely studied by cooperators and forms a separate school of thought, ignored by academic sociologists and economists.

The specific meaning of cooperation for the cooperative movement

In this case, the term refers to a specific type of entrepreneurship. " A co-operative is an autonomous association of persons united on a voluntary basis to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through joint ownership and democratically controlled enterprise” (International Cooperative Alliance, 1996). Thus, the cooperative serves the collective interests of its members (Fauquet, 1935). Cooperation in this sense refers to the collective action of its members, and not to the organization of the work process, except in the special case of labor cooperatives only because their members are also their employees. Early utopian thinkers defined collaboration according to the general meaning. In 1844, Owen contrasted the individualistic system of competition with the system of mutual cooperation (Owen, 1844). However, the evolution of the cooperative movement, and in particular “ heartbreaking reforms ”, by Gide's expression, which excluded workers and treated consumers as the only members, downgraded cooperation to membership (workers could also be called "participants" or "cooperators"). This use of the term can be defined as a specific sense of cooperation. We do not know of any recent sociological view that would establish a connection between the two understandings of the term, general and specific. (1) Single origin of the two senses of the term, referred to in the writings of Robert Owen, suggests that reintroducing a broader, more general meaning can help the co-operative movement more clearly define its areas of activity, for example, new ways of organizing the work process, new ways of organizing markets, etc.

This use of the term can be defined as a specific sense of cooperation. We do not know of any recent sociological view that would establish a connection between the two understandings of the term, general and specific. (1) Single origin of the two senses of the term, referred to in the writings of Robert Owen, suggests that reintroducing a broader, more general meaning can help the co-operative movement more clearly define its areas of activity, for example, new ways of organizing the work process, new ways of organizing markets, etc.

On the other hand, it can be argued that the increasingly limited range of application of cooperative principles can be cited as the reason why the cooperative movement considers itself (as it did before World War II) to be less of an alternative system than other forms of business. Since then, the cooperative movement has been increasingly seen as a sector that takes its place along with the other three sectors of the economy, namely capitalist, public and small business (Fauquet, 1935). This concept of the cooperative movement reaches its limits in the course of its transition to the mainstream, which began to influence part of the movement at the end of the twentieth century (Moreau, 1994).

This concept of the cooperative movement reaches its limits in the course of its transition to the mainstream, which began to influence part of the movement at the end of the twentieth century (Moreau, 1994).

(1) As far as we know, the last person to attempt this connection was Henry Desroches. Desroches' approach was focused on the members of the cooperative, and more specifically on its utopia.

Regulation and innovation: connecting narrow cooperation with broad cooperation

Parallel development of mainstream practices and new cooperative practices

Some changes show how the cooperative movement has adopted mainstream practices. This is in line with the overall process of economic integration. From the end of World War II until the 1980s, cooperatives found themselves strongly integrated into the overall economy, however, this came at the cost of weakening some of their specific traits, which in turn affected the movement's self-image. These changes include:

These changes include:

● Compliance of cooperative production with the production of capitalist enterprises;

● focus on high volume sales;

● investing heavily in the development of specific areas such as training and, in particular, the training of board members;

● declining participation rates of members and elected officials;

● the growing power of paid managers;

● hiring based on skills rather than socioeconomic values;

● expansion of wage differences;

● external growth leading to the formation of holding companies with capitalist companies sometimes more powerful than the parent cooperative.

The phenomenon of adopting mainstream practices (Moreau, 1994), and even becoming traditional companies (Vienney, 1994), has all been noted, especially among agricultural cooperatives and cooperative banks. less in agricultural cooperatives adhered to certain fundamental principles (such as cooperative exclusivity and “own capitalism”), and in some cases they did not exist at all (Mauget and Koulytchisky, 2003). (2)

(2)

(2) See René Magot's article on this subject.

In co-operative banks, banking activities pursue goals that are different from the wishes of the founding members, but are more in line with the policy of pure economic growth than the provision of services to their members (Richez-Battesti, Gianfaldoni, Glouoviezoff and Alcaras, 2006; Ory, Gurtner and Jaeger, 2006). (3)

(3) See the article by these authors regarding this issue.

One of the main difficulties in resolving this issue is the lack of a cooperative concept of the market. A number of authors, namely Claude Vinnie, Maurice Parodi, Daniel Cote, Serge Kolytchinsky, René Magot, Yair Levy, Jacques Defone and Daniele Demoustier, have shown that The market plays a central role in the development of cooperatives. This is the main issue that the International Cooperative Alliance considers one of its top priorities (Zevi and Monzon Campos, 1995; Spear, 1996; Chomel and Vienna, 1996; Cote, 2001). The market question is being considered not only in terms of cooperative adaptation, but also in terms of participation of cooperatives in the creation of the market. This approach began with Lambert and Peters (1972) and François Perroux (1976). The authors showed, on the one hand, that the price is determined not only by the market and, on the other hand, that the distribution of means of production is not tied to the relative cost of resources and is largely determined by the policies of transnational corporations. After these works, several currents in economics and in social economics have reconsidered the issue about how markets are created, in particular, the theory of regulation, the theory of closed markets, as well as the theory of conventions; namely, the theories that practitioners and researchers put forward to better understand what is happening in the social economy.

This approach began with Lambert and Peters (1972) and François Perroux (1976). The authors showed, on the one hand, that the price is determined not only by the market and, on the other hand, that the distribution of means of production is not tied to the relative cost of resources and is largely determined by the policies of transnational corporations. After these works, several currents in economics and in social economics have reconsidered the issue about how markets are created, in particular, the theory of regulation, the theory of closed markets, as well as the theory of conventions; namely, the theories that practitioners and researchers put forward to better understand what is happening in the social economy.

It must be emphasized that the developments briefly mentioned above, which bring cooperatives ever closer to the mainstream, were not immediately obvious or widely recognized. In parallel, there were numerous debates about hiring, wages, growth and distribution surplus. Thinking has changed as socio-economic enterprises become less and less involved in defining the rules of the market. First of all, urgent issues had to be addressed: the conviction that entrepreneurship will survive, the satisfaction of members, who are usually customers of the cooperative, and collective bargaining. The cooperative must be able to offer products, wages or working conditions that are equal or, if possible, even better than competitors. Could (could) cooperatives, or better yet, the social economy, trigger the growth of domestic markets and other forms of regulation?

Thinking has changed as socio-economic enterprises become less and less involved in defining the rules of the market. First of all, urgent issues had to be addressed: the conviction that entrepreneurship will survive, the satisfaction of members, who are usually customers of the cooperative, and collective bargaining. The cooperative must be able to offer products, wages or working conditions that are equal or, if possible, even better than competitors. Could (could) cooperatives, or better yet, the social economy, trigger the growth of domestic markets and other forms of regulation?

However, there have been important changes since 1980. New cooperative practices have emerged:

● Creation of the first social cooperatives;

● A recruitment policy that takes into account cooperative values;

● courses for employees and board members;

● more active participation;

● in the banking sector, the development of social policies for the benefit of poor groups and the promotion of alternative banks;

● in agriculture, development and implementation of social reporting;

● reorganization of democratic representation in large cooperative federations;

● Growth strategies focus more on the region and less on the sector, reflecting an attempt by local actors to re-appropriate markets;

● promoting complementary relationships between cooperatives both locally and internationally;

● Alternative promotion of cooperatives and the social economy (eg through mass advertising campaigns).

These new developments do not affect all socio-economic enterprises, but the cooperative revival is not in doubt.

Membership as the basis of cooperative practices

What makes businesses reaffirm the principles of cooperation, and not follow unreliable popular practices? We argue that the main reason is the participation of members. The process of demutualization, which had an impact on large joint society in the UK over the past few years has had repercussions for the entire cooperative world. This shows that all that is needed for the disappearance of a cooperative or joint society is the withdrawal of its capital by a majority of its members. It may occur in various ways: the power of members is weakened by the arrival of new investors. But even before that happens, its members must consider themselves as corporate shareholders, not just members of the cooperative. However, if we take entrepreneurship then, first of all, a simple partnership of capital was all that was necessary for members to sell their shares, and, conversely, all that was necessary for the preservation of the Co-operative Wholesale Society, for example, was the transformation of its members into an organization (Melmoth, 1999). This is a classic case. Using the dual status of member and user allows the cooperative to persist. As Georges Foucault said, cooperative associations combine two elements: the association of people and common enterprise. This dual nature defines “ social relations between members in association ” and “ economic relations between them and enterprise ” (Fauquet, 1965, p. 40).

This is a classic case. Using the dual status of member and user allows the cooperative to persist. As Georges Foucault said, cooperative associations combine two elements: the association of people and common enterprise. This dual nature defines “ social relations between members in association ” and “ economic relations between them and enterprise ” (Fauquet, 1965, p. 40).

It is clear that George Foucault's concept must be revised so that it can be applied to a wide range of cooperatives, in particular cooperatives that have several different types of members. Often these two groups of users and members are not completely identical, in particular in social cooperatives. Establishing dual status as a central tenet of cooperative practices is tantamount to committing to a particular policy or establishing it as one of their goals. participation of beneficiaries as members, i.e. empowering them with the right and obligation to participate in general meetings. On the other hand, it also means that when active membership is not required, entrepreneurship shirks from cooperative practices.

On the other hand, it also means that when active membership is not required, entrepreneurship shirks from cooperative practices.

However, when cooperators abandon the practice of dual status, it is usually because their cooperative no longer functions as a cooperative. In this case, the rejection of the cooperative form thus establishes the rules of control a certain legal form in accordance with autonomous rules, defined internal practices (Reynaud, 1988), which determine everything in the end. While there is a risk of sociological simplification, this suggests that people choose economic principles that suit them. If all members of a co-op see themselves as customers and customers only, and if they have the same attitude towards it as they do to a regular company, then the co-op runs a great risk of feeling its own autonomous cooperative principles by the rules of control of a capitalist nature. Cooperative practices are separated from cooperative status, which may cause new social tensions, or greater economic pressure, or even changes in legislation, which may call into question the cooperative form. When a gap appears between status and practices, the most common way to close it is to change the legal form, rather than re-establishing cooperative practices (Chomel and Vienna, 1996).

When a gap appears between status and practices, the most common way to close it is to change the legal form, rather than re-establishing cooperative practices (Chomel and Vienna, 1996).

However, this process is not inevitable. Cooperative practice can be confirmed in the process of innovation. Typically, this involves recognizing that “creative disorder” is possible (Alter, 1993), and that more opportunities are given to actors. for autonomous regulation. It also suggests that there is a desire for change and collaborative learning. In addition to the necessary measures to protect and expand the internal charter, new cooperative rules should also be formulated. Innovation in a cooperative form, they create a link between values and law, between the utopia of social transformations and socio-economic restrictions. As demonstrated by the experience of Italian social cooperatives (Zandonai, 2002; Borzaga, 1997), these new rules precede future legislation taking into account basically all innovative practices that are already in direct use.

Conclusion: Collaboration as a process of collective learning

The biggest challenge facing socio-economic entrepreneurship is the definition of co-management rules that can resist constant interference in business affairs from dominant, competitive rules. The successive transformations of the social economy in the past, its current evolution, as well as the conditions for the emergence of a new social economy indicate that cooperative rules can only be obtained through cooperation between by its members, an act on the basis of which conventions and social and economic rules based on collective action are built. Far from acquired skills, conventions that favor cooperation (in work, in enterprise organization, in the socio-economic construction of markets) are a constant subject of discussion. Collaboration takes a long time, and is constantly questioned. This requires on the part of the actors mutual learning and constant striving for innovation and alternative forms of control.