Preview reading strategy

3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 31308

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

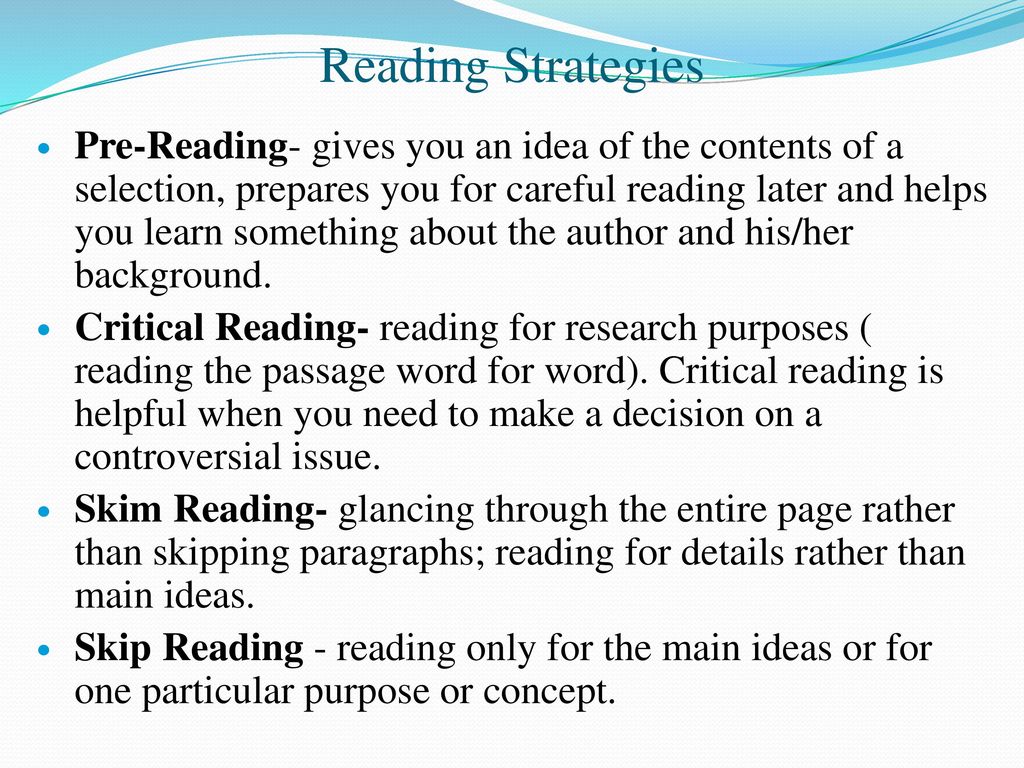

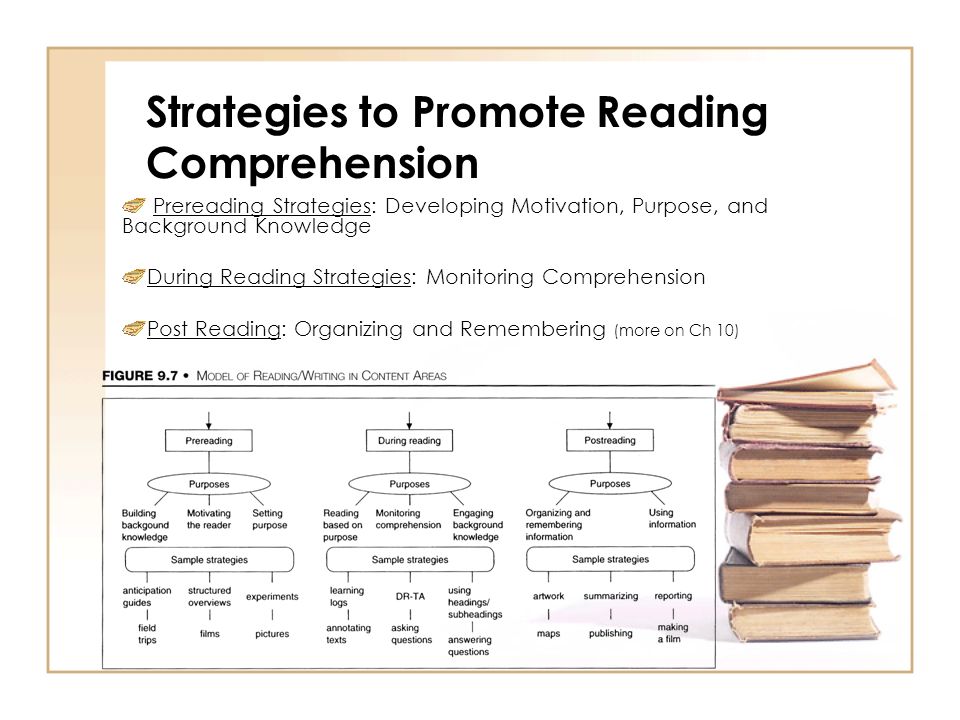

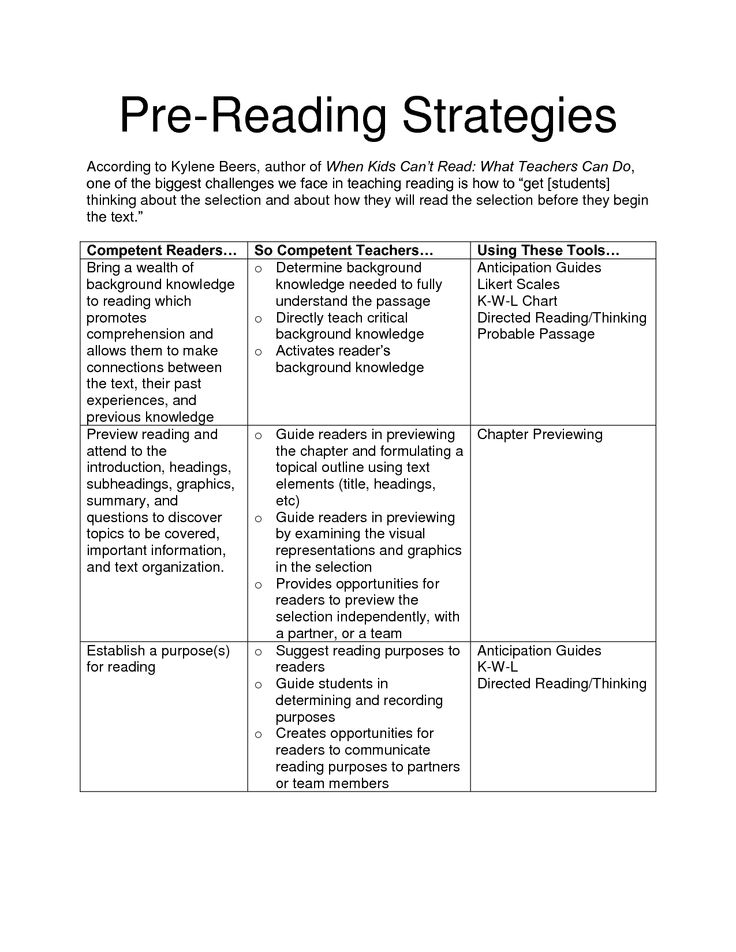

Pre-reading Strategies

The few minutes you spend preparing BEFORE reading any difficult material can motivate you to read it, as well as increase your ability to understand and remember what you read. Think about it like this: when you are driving to a new place, you would probably look at a map first (or at least turn on your GPS) so you don’t waste time getting lost. Similarly, when you approach a new academic reading, it’s best to use the 4P’s (

purpose, preview, prior knowledge, and predict) so you don’t struggle as much to figure out what the authors want to say or how they plan to say it. Preparing to read can also help you estimate how long you’ll take to read so you can plan your time more efficiently.

Reading Strategy: Previewing

What It Is

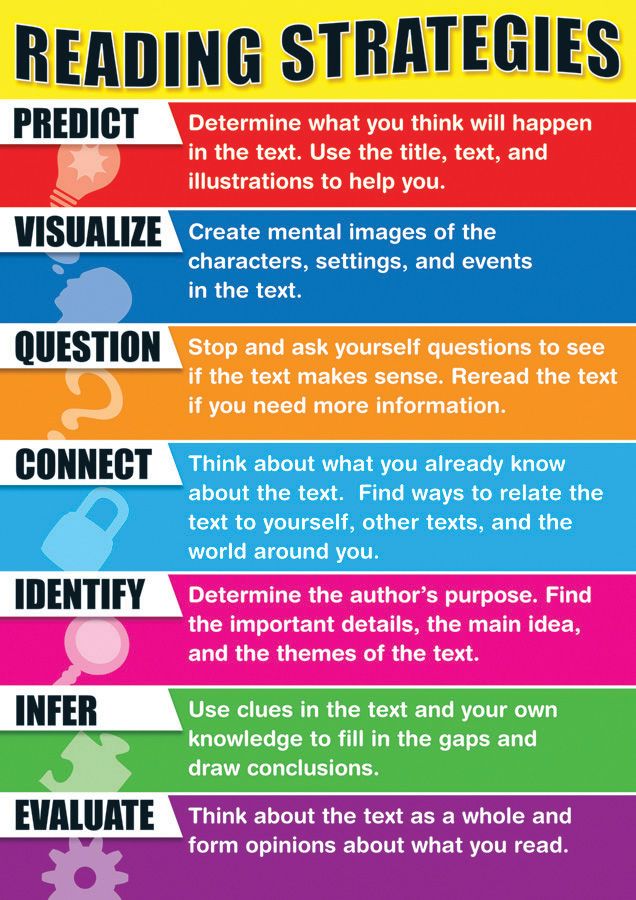

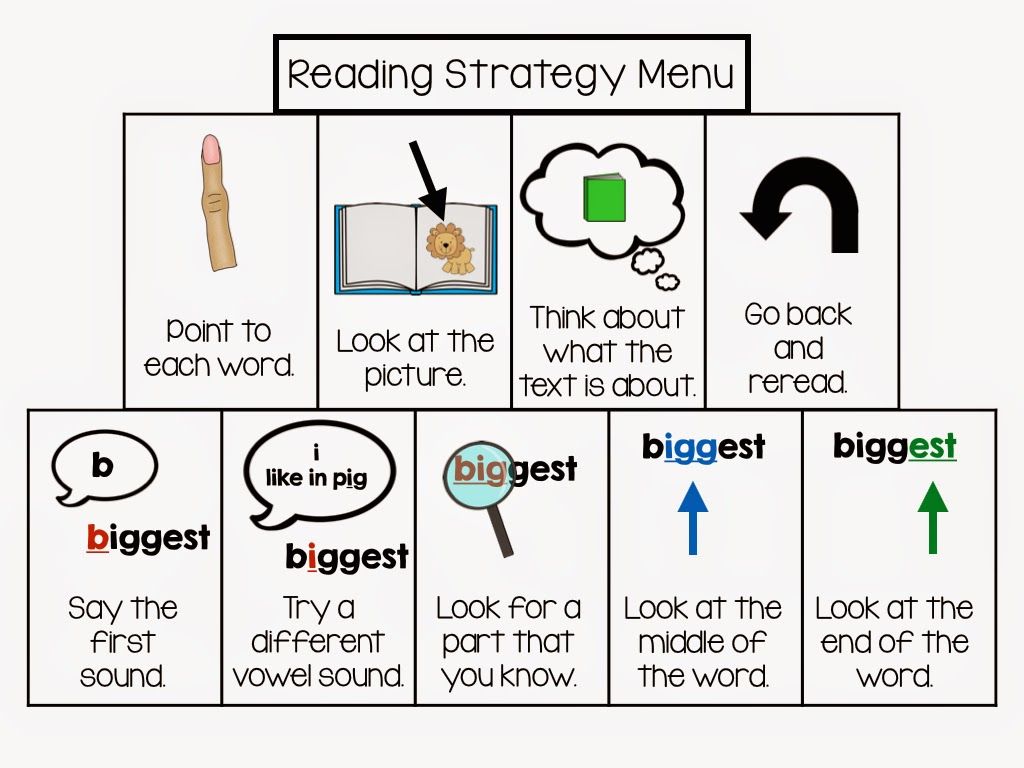

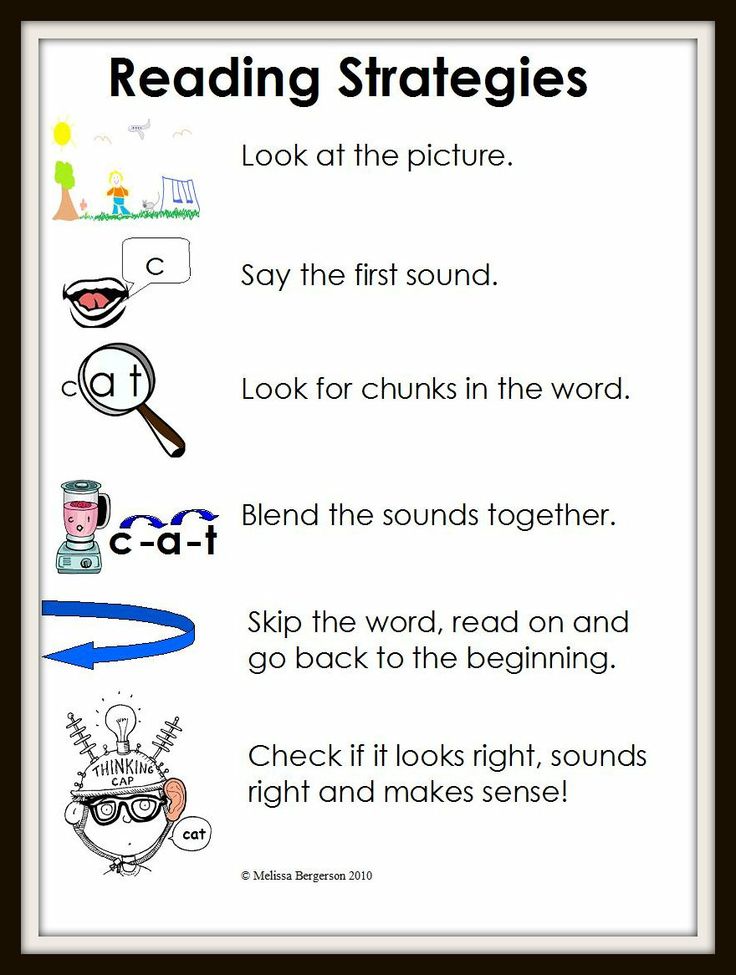

Previewing is a strategy that readers use to recall prior knowledge and set a purpose for reading. It calls for readers to skim a text before reading, looking for various features and information that will help as they return to read it in detail later.

Why Use It

According to research, previewing a text can improve comprehension (Graves, Cooke, & LaBerge, 1983, cited in Paris et al., 1991).

Previewing a text helps readers prepare for what they are about to read and set a purpose for reading.

The genre determines the reader’s methods for previewing:

- Readers preview nonfiction to find out what they know about the subject and what they want to find out. It also helps them understand how an author has organized information.

- Readers preview biographies to determine something about the person in the biography, the time period, and some possible places and events in the life of the person.

- Readers preview fiction to determine characters, setting, and plot. They also preview to make predictions about story’s problems and solutions.

When To Use It

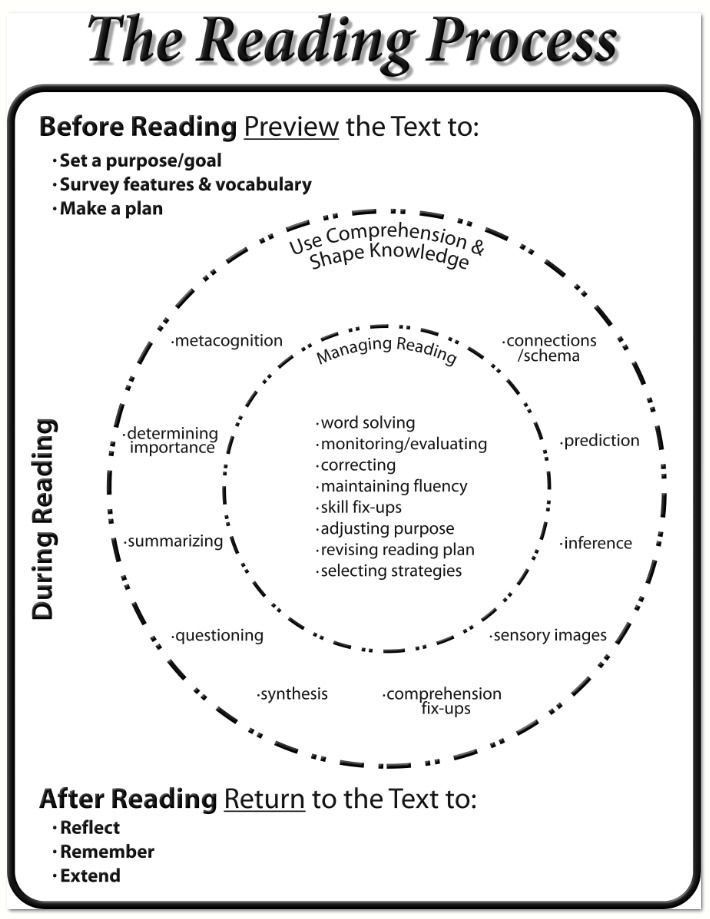

Previewing is a strategy readers use before and during reading.

How To Use It

When readers preview a text before they read, they first ask themselves whether the text is fiction or nonfiction.

- If the text is fiction or biography, readers look at the title, chapter headings, introductory notes, and illustrations for a better understanding of the content and possible settings or events.

- If the text is nonfiction, readers look at text features and illustrations (and their captions) to determine subject matter and to recall prior knowledge, to decide what they know about the subject. Previewing also helps readers figure out what they don’t know and what they want to find out.

How to Preview

Figure: CC BY-NCPreviewing a text is similar to watching a movie preview.

Think of previewing a text as similar to watching a movie trailer. A successful preview for either a movie or a reading experience will capture what the overall work is going to be about, generally what expectations the audience can have of the experience to come, how the piece is structured, and what kinds of patterns will emerge.

Previewing engages your prior experience and asks you to think about what you already know about this subject matter, or this author, or this publication. Then anticipate what new information might be ahead of you when you return to read this text more closely.

Specific Previewing Strategies

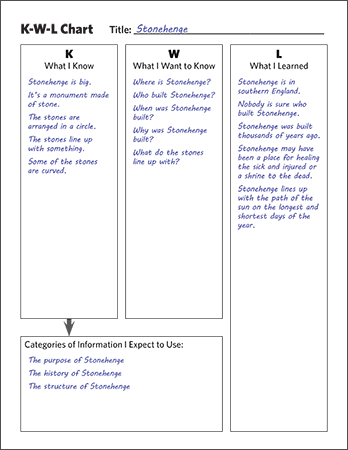

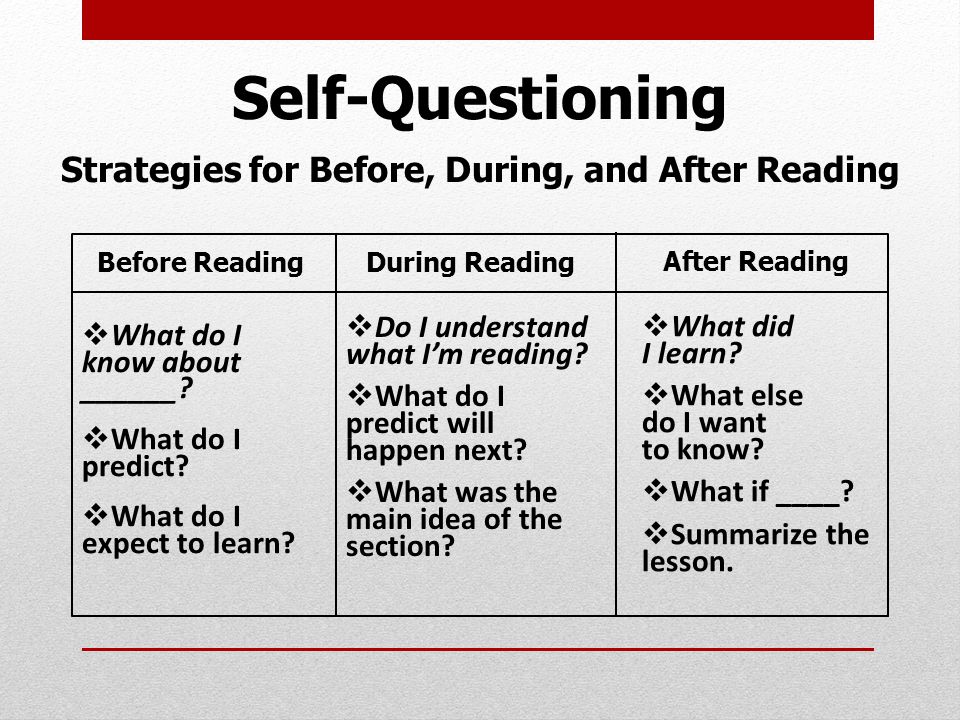

KWL+

KWL+ is a simple strategy that is both a reading-writing strategy, as well as an overall structure for research papers. K stands for "What I Know". W

stands for "What I Want to Know." L stands for "What I Learned. " + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

" + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

After a brief review of the topic you will be reading about, on a piece of paper, create a table like the one below with the topic at the top of the page. Write down what you already know about the topic in the K column and what you want to learn in the W column. Use the "K" column as an "into the reading" activity and the "W" column as a guide for what you will look for as you read about the topic. After you have done your research or reading, write down what you learned in the "L" column. Then -- at the end of the research process or when you are done reading -- write down what you still want to know in the "+" column. This becomes a recursive process (routine) in which the "+" can then become the base for the next round of your inquiry.

Topic: _________________________________________________________________

| K (What I Know) | W (What I Want to Know) | L (What I Learned) | + (What I Still Want to Know) |

- Topic: _________________________________________________________________

The 4 "P"s: Purpose, Preview, Prior Knowledge, Predict

1. Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

- Are you looking for general main ideas or specific details, or both?

- Are you going to discuss what you read in class, take a test, use what you read in an essay? Or are you just reading for pleasure?

- How does this reading task tie into the unit or the whole course?

2. Preview: Spend a few minutes looking at visual clues to the author’s central idea, supporting points, and organization of ideas. Depending on the type of reading, look at some, or all, of the following elements:

- Title

- Introductory information about the author and/or selection

- First and last paragraphs

- First sentence of body paragraphs

- Headings and subheadings

- Italics, bold print, numbers, symbols

- Comprehension questions or, other after-reading assignment

3. Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

4. Predict: After previewing a text, a reader can begin to make guesses about what the writer wants to say. These predictions are important in motivating you and keep you focused while reading.

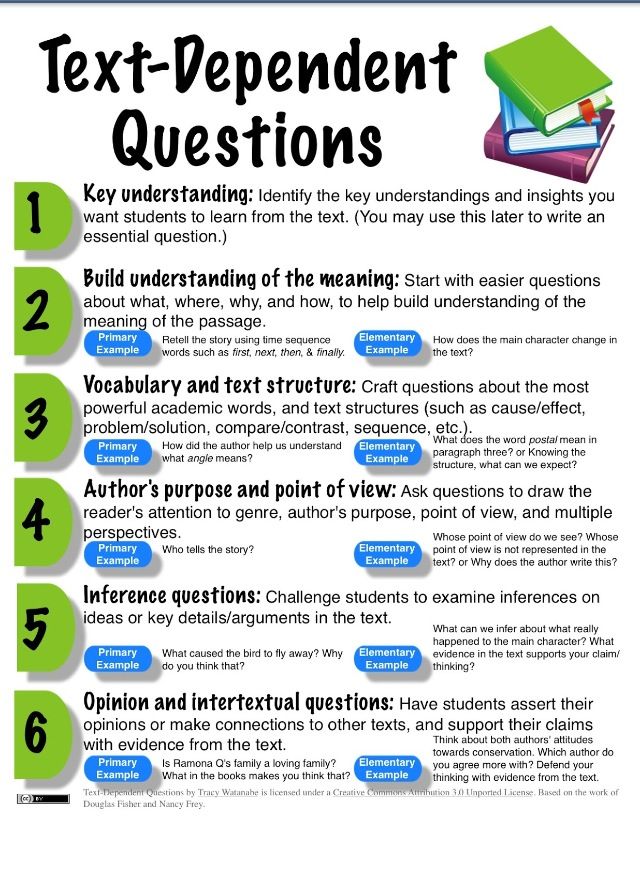

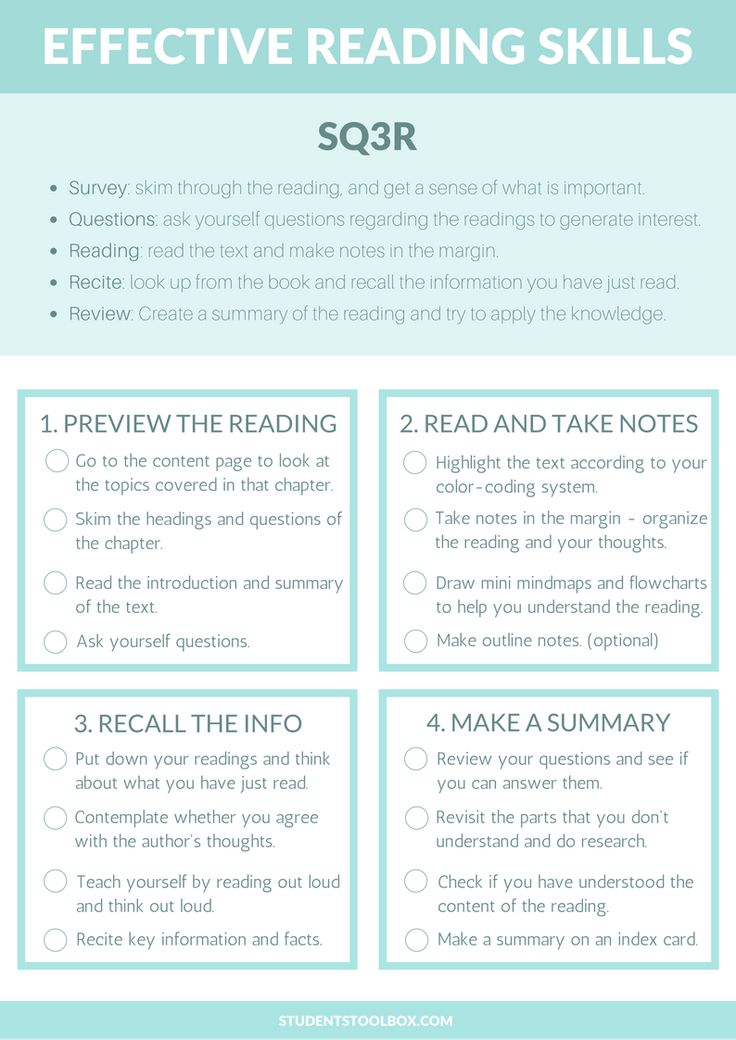

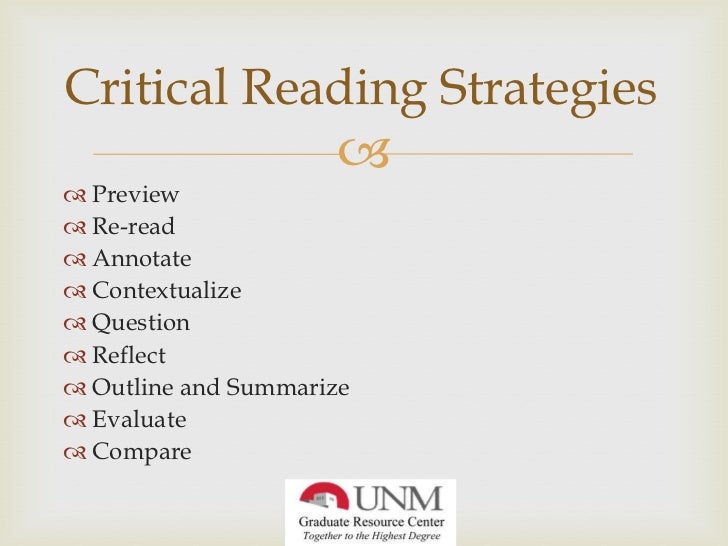

Use the SQ3R Strategy

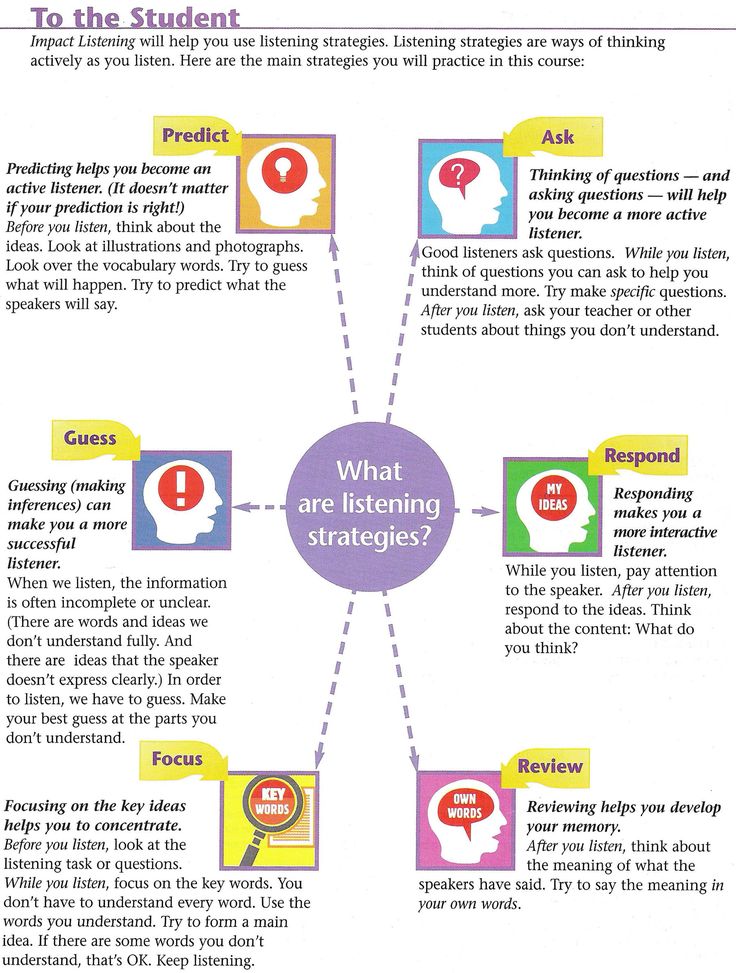

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy, a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already be using some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

1. Survey the text in advance.

2. Form questions before you start reading.

3. Read the text.

4. Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

5. Review and reflect on the text after you read.

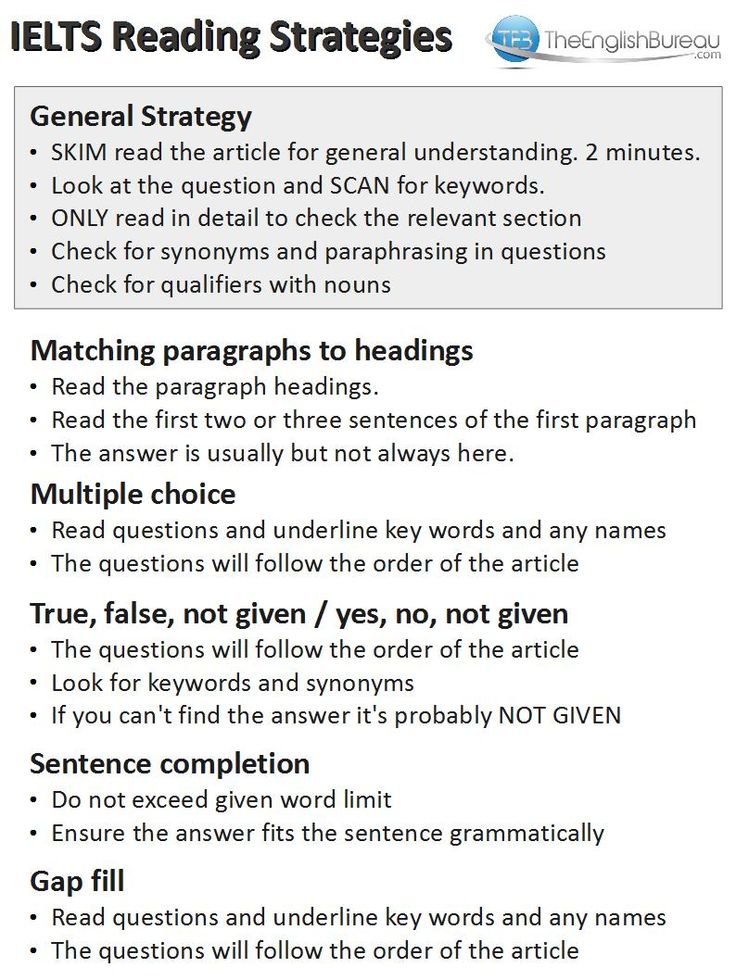

Before reading, survey -- or preview -- the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you figure out the text's main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading i your textbook reads "Medicare and Medicaid," you might ask yourself:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are ore open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author's main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted--or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

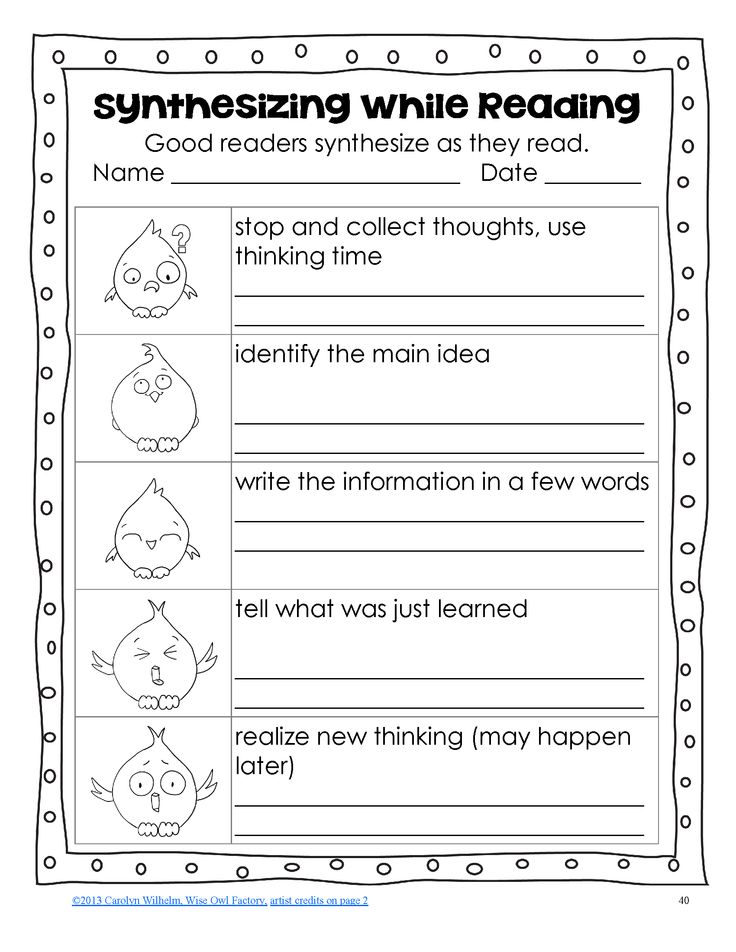

While you are reading, pause occasionally to record/recite important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or where there is an obvious shift in the writer's train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agree or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

The video below explains a little more about the SQ3R strategy.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Choose another text that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect o n how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Use Other Active Reading Strategies

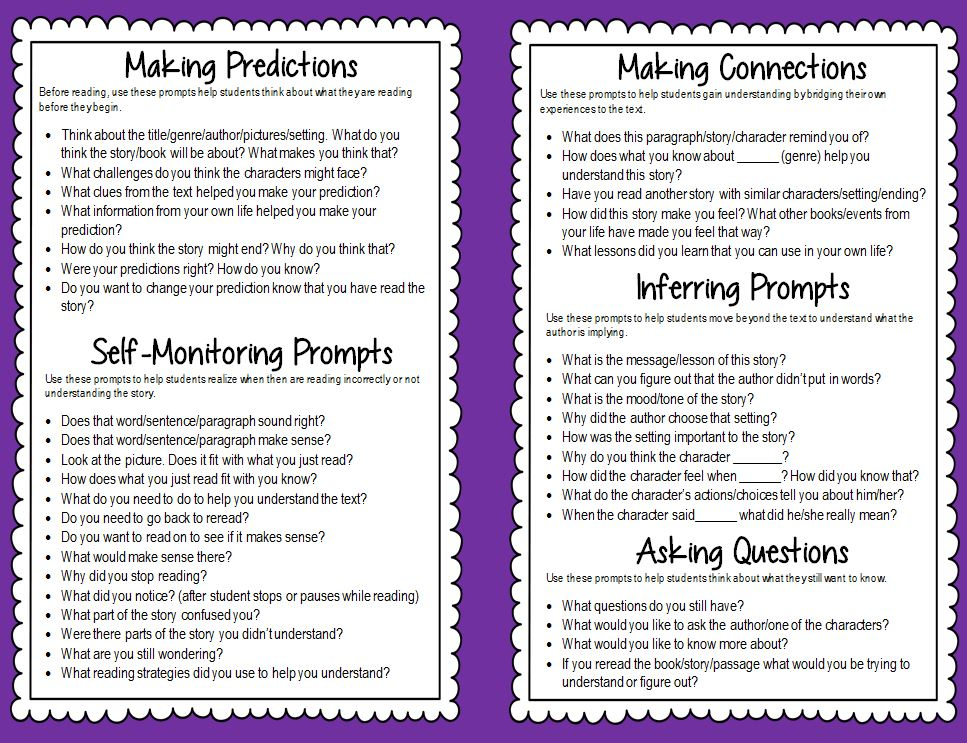

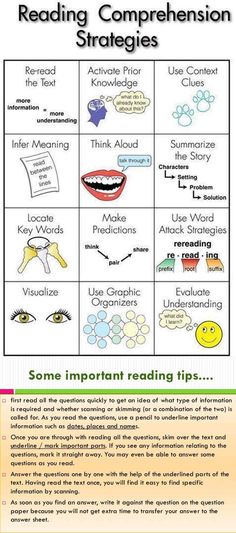

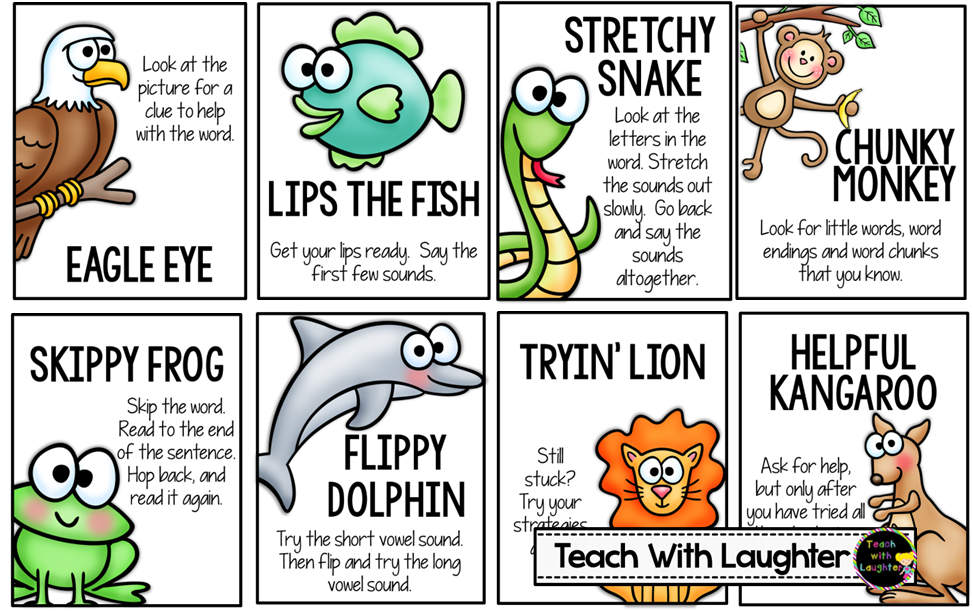

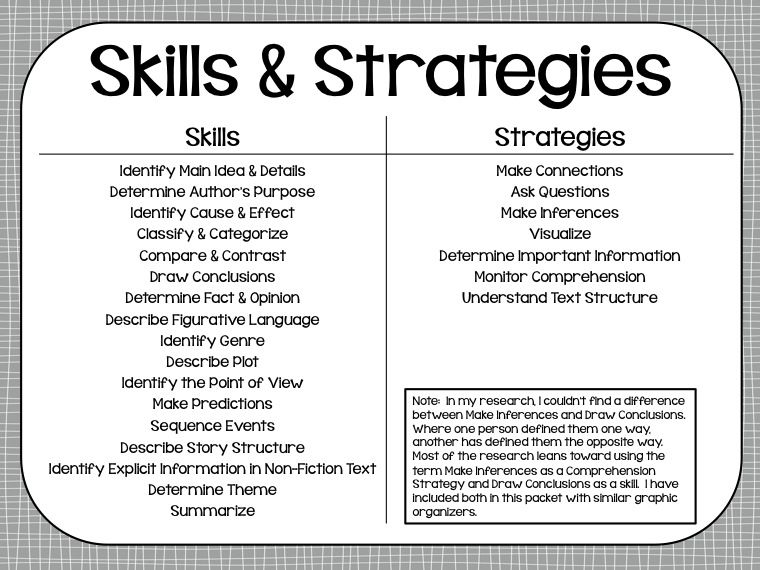

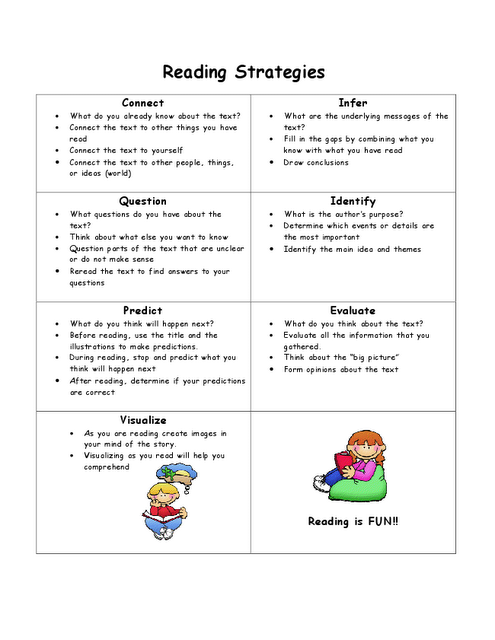

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering quesitons, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize.

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). - Pay attention to graphics a well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author's purpose in writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author's ideas. For instance, two writers address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the rhetorical context is different.

- Plan to talk or write about what you read.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Additional Strategies

Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments. - Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text is sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell phone while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- Highlight your reading material. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read. - Annotate your reading material. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class!

The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text.

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”Watch the following video on annotating texts:

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Video: Annotate It! Authored by: Janene Davison. All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

- Get to Know the Conventions. Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

- Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases. Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. Many books available on an e-reader have definitions already embedded if you highlight the unknown word. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them. - Make Flashcards. If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you. Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words.

Contributors

- Adapted from Previewing in College Composition. Provided by: Lumen Learning.

CC BY-SA

CC BY-SA - Adapted from Successful College Composition. Authored by: Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Provided by: Galileo, Georgia's Virtual Library. CC-NC-SA-4.0

- Adapted from EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Public Domain: No Known Copyright

This page most recently updated on June 6, 2020.

This page titled 3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing is shared under a CC BY-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative) .

- Back to top

- Was this article helpful?

-

- Article type

- Section or Page

- Author

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- License

- CC BY-SA

- OER program or Publisher

- ASCCC OERI Program

- Show TOC

- yes

- Tags

-

- #4Ps

- #annotation

- #KWL+

- #predict

- #preview

- #previewing

- #prior knowledge

- #purpose

- #reading

- #reading strategies

Previewing | English Composition 1

Learning Objectives

- Use previewing as a reading strategy

Reading Strategy: Previewing

What It Is

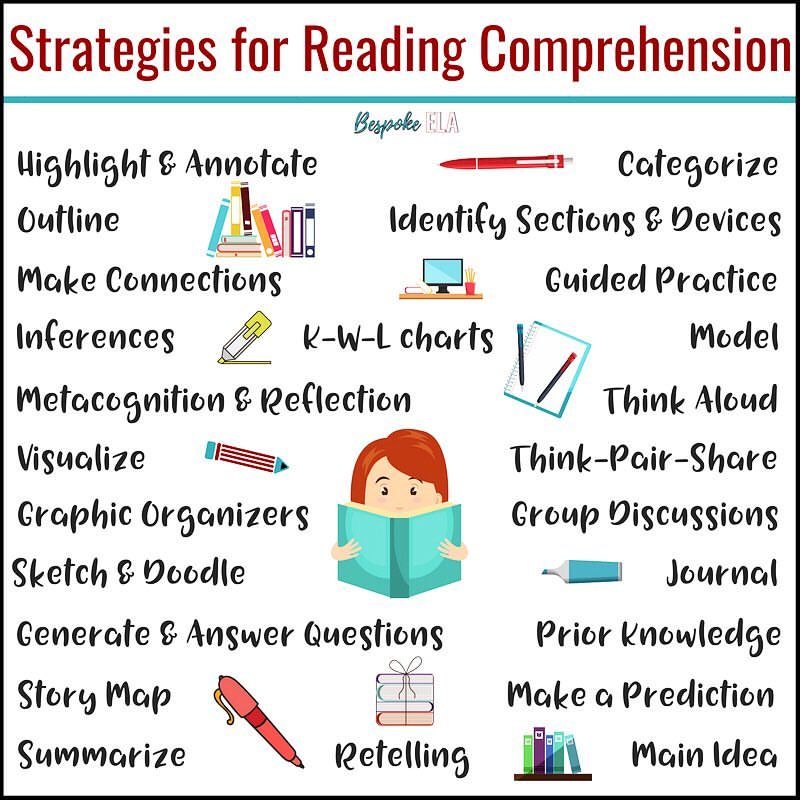

Previewing is a strategy that readers use to recall prior knowledge and set a purpose for reading. It calls for readers to skim a text before reading, looking for various features and information that will help as they return to read it in detail later. Think about the word itself in parts. “Pre” is prefix that means “before” and the word “viewing” is to see. You are quite literally thinking about how to see before you read.

It calls for readers to skim a text before reading, looking for various features and information that will help as they return to read it in detail later. Think about the word itself in parts. “Pre” is prefix that means “before” and the word “viewing” is to see. You are quite literally thinking about how to see before you read.

Why Previewing Matters

Figure 1. Think of previewing a text as similar to watching a movie preview.

According to research, previewing a text can improve your comprehension (Graves, Cooke, & LaBerge, 1983, cited in Paris et al., 1991). You set a purpose for your reading to help you prepare for what’s coming next.

Depending on the genre, or the kind of reading, your approach to previewing may vary:

- To preview nonfiction, find out what you know about the subject and what you want to find out. This also helps to understand how an author has organized information.

- To preview biographies, determine something about the person in the biography, the time period, and some possible places and events in the life of the person.

- To preview fiction, determine characters, setting, and plot. Preview to make predictions about a story’s problems and solutions.

How To Use Previewing

To preview a text before you read, first ask yourself whether the text is based on reality or true events (nonfiction) or if it’s creative story (fiction).

- If the text is fiction or biography, look at the title, chapter headings, introductory notes, and illustrations for a better understanding of the content and possible settings or events.

- If the text is nonfiction, look at text features and illustrations (and their captions) to determine the subject matter and to recall prior knowledge, to decide what you already know about the subject. Previewing also helps you figure out what you don’t know and what you need to learn.

How to Preview

Think of previewing a text as similar to creating a movie trailer. A successful preview for either a movie or a reading experience will capture what the overall work is going to be about, generally what expectations the audience can have of the experience to come, how the piece is structured, and what kinds of patterns will emerge.

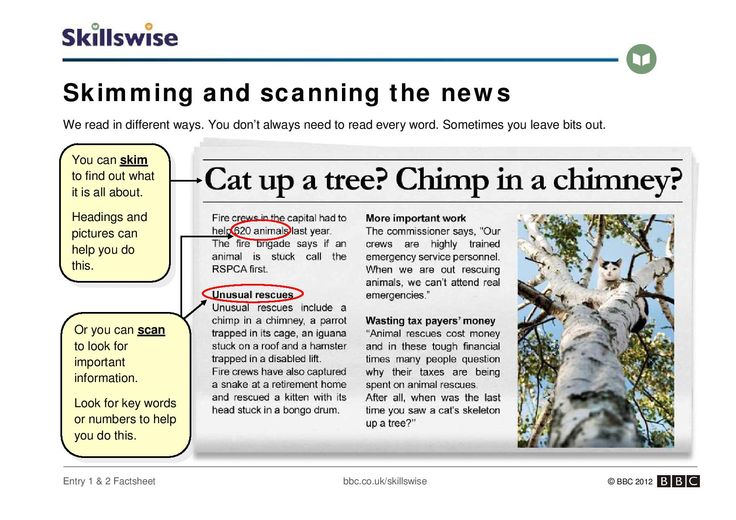

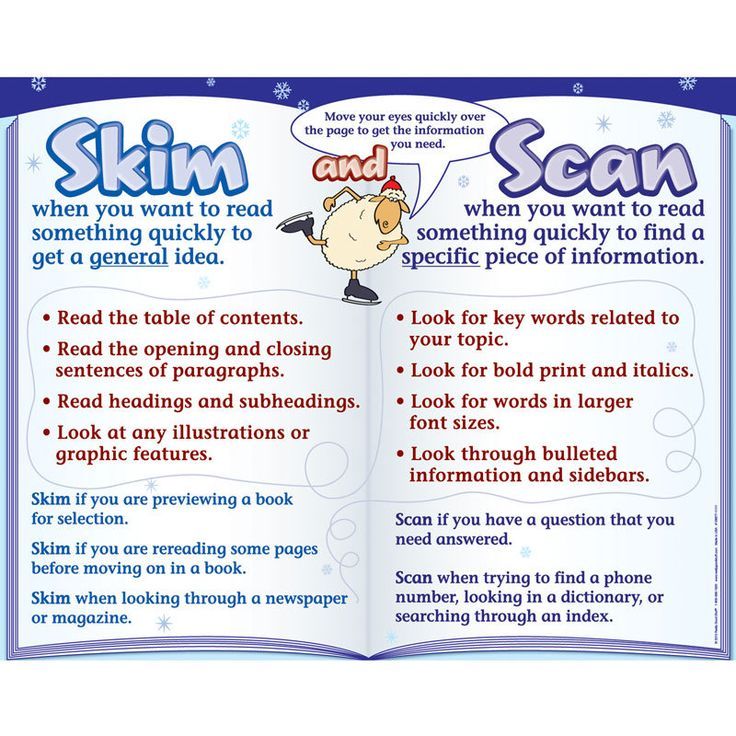

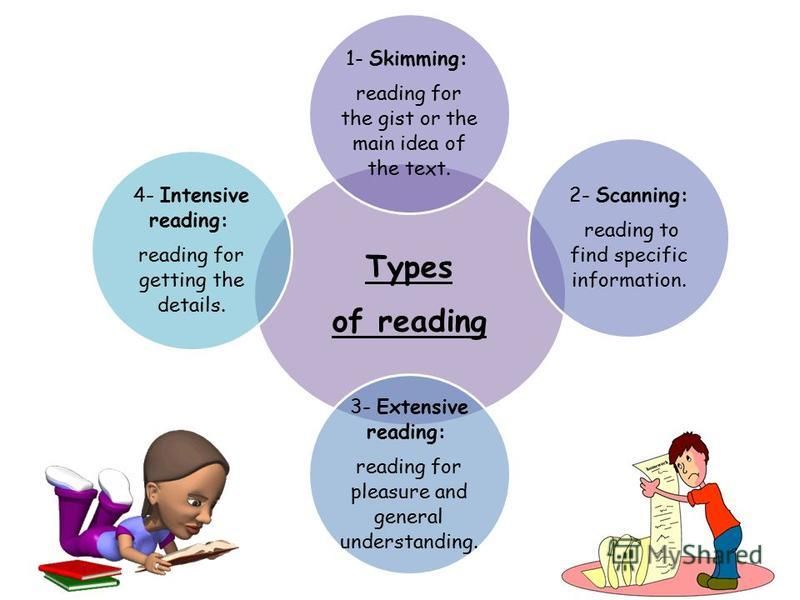

Scanning and Skimming

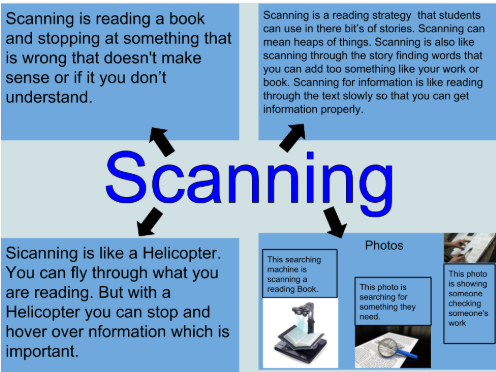

Scanning

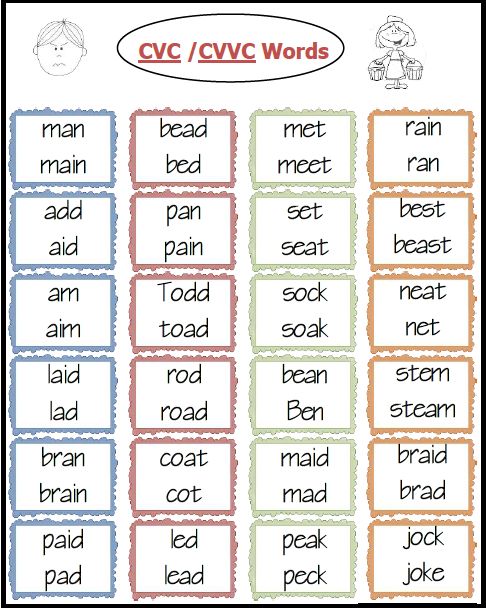

The technique of scanning is a useful one to use if you want to get an overview of the text you are reading as a whole – its shape, the focus of each section, the topics or key issues that are dealt with, and so on. In order to scan a piece of text you might look for sub-headings or identify key words and phrases which give you clues about its focus. Another useful method is to read the first sentence or two of each paragraph in order to get the gist of the discussion and the way that it progresses.

Figure 2. Identifying sub-headings and key words as you scan a particular text can help you to get an overview of the bigger ideas and themes.

Scanning is also used to find a particular piece of information. Run your eyes over the text looking for the specific piece of information you need. You may run your eyes quickly down the page in a zigzag or winding S pattern. If you are looking for a name, you note capital letters. For a date, you look for numbers. Vocabulary words may be boldfaced or italicized. When you scan for information, you read only what is needed. If you see words or phrases that you don’t understand, don’t worry when scanning.

For a date, you look for numbers. Vocabulary words may be boldfaced or italicized. When you scan for information, you read only what is needed. If you see words or phrases that you don’t understand, don’t worry when scanning.

Using internet tools such as a search bar or Ctrl + F can be useful when scanning. Some tips for scanning:

- Scan for titles, headings, and subheadings

- Scan the first sentence after each heading

- Scan any supplemental material at the beginning or end of the text, such as chapter outlines, chapter objectives, discussion questions, or vocabulary lists

Skimming

Skimming is used to quickly gather the most important information, or “gist” of a text. Run your eyes over the text, noting important information. Use skimming to quickly get up to speed on the basic content coverage; it’s not essential to understand each word when skimming. As you skim, you could write down the main ideas and develop a chapter outline. Some tips for skimming:

- Skim the first paragraph or introduction

- Skim the last paragraph or summary

- Skim the abstract (if provided)

When you preview, you look for signposts by making a note of graphic aids such as figures, tables, charts, graphs, and images. You can get a lot of information about the reading itself if there are images included. You may also want to note typographical aids such as bold-faced or highlighted words and phrases. Previewing engages your prior experience, and asks you to think about what you already know about this subject matter, or this author, or this publication. Then anticipate what new information might be ahead of you when you return to read this text more closely.

You can get a lot of information about the reading itself if there are images included. You may also want to note typographical aids such as bold-faced or highlighted words and phrases. Previewing engages your prior experience, and asks you to think about what you already know about this subject matter, or this author, or this publication. Then anticipate what new information might be ahead of you when you return to read this text more closely.

Watch It

This video explains the advantages of previewing a text and how to do it successfully.

You can view the transcript for “How to Preview a Text” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Contribute!

Did you have an idea for improving this content? We’d love your input.

Improve this pageLearn More

Pre-reading strategies (meaning, basic strategies, home strategies)

Learning is of paramount importance for everyone; as we grow daily, we must learn, unlearn, and relearn through reading preparation strategies.

Not only to add it to our vocabulary, but also to use it in our daily activities.

The preliminary stage of learning is infancy. Children are meant for daily learning to build them up, hence the reason for pre-reading strategies.

Contents

What are pre-reading strategies?

Reading preparation strategies are learning approaches or methods designed to help your child gain structure, guidance, balance, and background knowledge before they begin to learn a new text or solve a new problem.

These strategies aim to develop your child's reading and comprehension skills by giving them the tools they need to become an active and successful reader.

Reading and understanding at a tender age is something that young children find tiresome.

You rarely meet a child who is fond of reading.

By activating your child's already existing knowledge in certain subjects, learning to use contextual cues and talking to you about the book, they will soon become champions in reading and writing scientific essays.

Basic pre-reading strategies

Dad helps son with pre-reading strategies. As the name suggests, reading preparation strategies are used first before you start reading a book with your child.

There are a few basic strategies you can use to help your child prepare to dive into any story or understanding.

Preview:

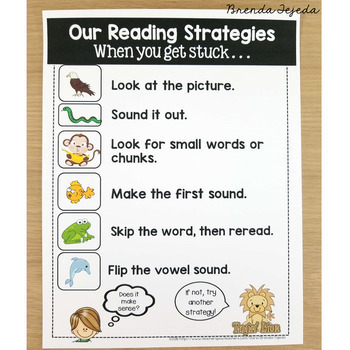

Preview means giving your child the opportunity to gather clues, reviews, etc. from the book title and cover illustrations, internal illustrations, and possibly the table of contents, so that older children can try to understand what might happen or what they might learn from the book they are about to read. hear or read before actually getting the real thing.

Target:

If you have time, it's always a good idea to take a moment to pay attention before reading with your child. This is one of the most important basic strategies before reading.

Talk to them about what reading goals they want to achieve after reading the book you bought for them.

Do they still need help with longer words or words with funny accent patterns (pronunciation)?

Do they want to work on their characters' voices or voiceover (expression)? Getting their information will help both of you come together to set a goal or goal for your reading together.

Predictions:

Using the resources available to your child, see if he can predict what might happen in a story before he has a chance to read anything, such as judging a book by its cover before he has read it. her.

What information can they gather just by using the title, cover and illustrations?

Read this: Underrated parts of school you should focus on

Pre-reading strategies to try at home:

1) Speaking in questions:

This is a fun activity that will help your child better understand the text he is reading by allowing him to make jokes about said text.

You probably use the questionnaire with your children at home, but the child should ask the question here. Your child has the right to ask any questions.

For example, if you are reading Goldilocks and The Three Bears, you can start a conversation with questions by asking the child, “Why is her name Goldilocks?” Your child may ask back, "Why are these bears in the house?"

See how many questions you can ask in these interactive segments. In most cases, there is a tendency for questions to remain unanswered until you have finished reading the text.

2) KWLH Graph:

This pre-reading exercise was invented and celebrated by Donna Ogle back in the 1980s.

This is one of the pre-reading strategies with different letters in the KWHL charts representing different tasks your child has to complete and compete.

The K column is reserved for what your child already knows about the subject of the story they have already read.

The key here is to activate and then reflect on your previous knowledge. For example, if they are reading Charlotte's Web, what do they already know about pigs according to the book?

The "W" category is for what your child wants to know about history. What they are curious about how to find out.

"L" (what we learned from the story) in the process of reading.

Columns "H" (how they can learn more) are reserved for discussion after you've finished reading the book.

The last row, how they can learn more, is more important in scientific literature than in fiction. It is advisable to use popular science books for this purpose.

The pleasure of this exercise is to physically force the child to do it, not to see it as a task.

3) Preliminary vocabulary:

If you know that the book you will be reading together will challenge your child's current reading skills, consider teaching them a few more difficult words before you start reading to ensure reading fluency.

4) Reading Preparation Strategies : Preliminary Topics

Many children's books are designed to teach children more than new words. They usually have moral lessons embedded in their pages to help with real moral teachings.

To focus the child's attention on the topic of the book, you can encourage him to discuss the same moral lesson contained in the book and link it to a real life scene.

Look at their initial opinion, their interpretation, and see if they already have a clear idea about it, or if they want to know more?

Read this: How old are you in 10th grade (best answer)

5) Word Bingo:

This game is another great option for preparing your child's mind to learn vocabulary or brush up on words they need extra help trying to fix or get.

If you would like to try this exercise before reading, create a bingo sheet using words from the text before reading time.

Each time you or your child hears or sees a word that matches a word on your sheet, place an emoji on it. The first one to yell "Bingo!" wins instantly.

Conclusion:

It is essential that children go through the stages of preparation for reading in life before delving into life's quest. Parents are encouraged to send their children to tutors who can properly educate their children.

Awesome; I hope this article has answered your question.

Share this information.

Editor's recommendation:

Reading strategies - Studopedia

Share

How do you feel about rational reading? Apparently such when work with large volumes of information, with a large number of books is carried out with maximum productivity and with minimal effort and time. It is clear that work with books should begin with psychological preparation. By viewing the first book, you need to determine for yourself whether to read it or put it aside, whether it is advisable or not to work on it, and if appropriate, then in what class you need to read: either study the entire book in depth, or superficially review it, reading only separate parts , either find the necessary section in it and read this section selectively, or quickly find the necessary facts and thoughts in the book. In accordance with the task set for oneself, it is desirable to choose a specific reading strategy and work through the book in a planned way. Then move on to the second, to the third book, and so on. At the same time, it is desirable that reading strategies be worked out in advance.

In accordance with the task set for oneself, it is desirable to choose a specific reading strategy and work through the book in a planned way. Then move on to the second, to the third book, and so on. At the same time, it is desirable that reading strategies be worked out in advance.

Studies by psychologists who are not supporters of learning speed reading types, but recognize the reality of the existence of readers with high reading speeds, have shown that one of the main foundations of speed reading skills is FORMED (note, not innate, but acquired as a result of practical training) READING HABITS FOR THE FOUR READING STRATEGIES:

1. The viewing strategy of reading.

2. Analytical strategy of reading.

3. Selective reading strategy.

4. Search strategy for reading.

Therefore, in order to learn how to read quickly, you need to FORM A STABLE MENTAL INSTALLATION to READ ALL TEXTS IN ONLY ONE OF THE FOUR STRATEGIES (and nothing else!).

| LETTER CHARTS | |||||||||

| b P X in to | about t l With at | g a f d c | s Yu e n w | w m sch s h | e R I th and | ||||

| s d h I in | about f Yu th b | X uh sch and | g h m to R | w c w a e | t P With l n | ||||

| 8888 | |||||||

| p h d and m | c l h R w | x With Yu sch I | in G at and th | about a e s f | t to n uh b | ||

| 8888 | ||||||

| with m n about G | yu uh in X d | h w and P f | a th e t at | w I b and s | l to R c h | |

| 169 |

| p h d and m | c l h R w | x With Yu sch I | in G at and th | about a e s f | t to n uh b | ||

| k at in and th | f e s w and | d Yu c X I | n h h l uh | w P G R m | a b about t With | ||

| at e G sch | f in P about d | i With and b uh | a X Yu l c | s to w t m | n and h R uh | ||

| 8888 | |||||||

| e and at a about | e s b t | i sch G Yu P | sh n f h X | m and h l c | k R d With in | ||

| 8888 | |||||||

| w in c h | s uh n X d | h at e b f | p m t l th | w to P and s | a I and about G | ||

| 8888 | ||||||

| s P m l n | about f Yu th b | X uh sch and | t h With to R | w c w a e | g d h I in | |

tables of tables

| 26 | |||||||

| 25 | |||||||

Viewing reading - This is a preliminary reading, on the basis of whether the text is determined, the class is determined to which the text refers to the text, and at the same time the text of the textista is wrapped together with the total content of text. important facts and thoughts of the text. Guided by the belonging of the text to a particular class, you will remember the text reader corresponding to this class. Reading in the third grade can be attributed to the viewing strategy of reading.

important facts and thoughts of the text. Guided by the belonging of the text to a particular class, you will remember the text reader corresponding to this class. Reading in the third grade can be attributed to the viewing strategy of reading.

Having developed a scanning reading strategy, you will be able to “take a look at the text with a single eye”, present its structure, clarifying its idea, drawing up a plan for future in-depth study: what should be paid special attention to, and what can be omitted without losing the meaning of the text. Viewing reading is used especially successfully by those who have mastered well and worked out to automatism the skill of anticipation - mental prediction of the text. This skill is very important for developing a scanning reading strategy. Those readers who do not have the skills of viewing reading have to look through almost all lines of the text while reading the text in order to get an idea of the content of the text. Readers with at least mental prediction skills will be able to form a general idea of the text by selectively reading parts of the text and further guessing what was not learned. Readers with skim reading skills not only use their mental forecasting skills, but also know how to move their eyes through the text reasonably (rationally) in terms of time and effort.

Readers with skim reading skills not only use their mental forecasting skills, but also know how to move their eyes through the text reasonably (rationally) in terms of time and effort.

Based on this functional program, the brain directs the further process of reading. This program is implemented in a complex trajectory of gaze movement. Scientists have proven that the more complex the trajectory of the gaze when reading, the better the assimilation of the text.

Those who have worked out accelerated reading, and these are those who have studied conscientiously, have developed such skills that those who have not specifically dealt with these problems cannot have. In practical classes, when performing exercises, you form this functional program of the reading strategy, the brain directs the alignment of the trajectory of the movement of the gaze. Within two weeks of training, you will get used to the chosen reading strategy, gain automatism in working with text, and fixing this functional program is a matter of practice.

Analytical reading strategy is determined by the goal facing the reader to gain solid knowledge about the subject of reading and study, and this task involves reading and understanding what has been read, processing the information received into fundamental knowledge that can always be remembered. It remains to add that if you have chosen the strategy of in-depth analytical reading, try not to slow down your reading speed. We suggest reading:

1) popular science literature at a speed of 1500-3000 characters per minute;

2) periodicals (newspaper text) - 3000-5000 characters per minute;

3) educational or scientific texts - 200-600 characters per minute.

You use the scanning reading strategy to find out what the text is about and where the information that is most relevant to you is located. But you still need to learn, without wasting time processing irrelevant information, to read texts using the selective reading strategy. This strategy will help you find the information you need, for example, find out what new publications have appeared in your specialty.

This strategy will help you find the information you need, for example, find out what new publications have appeared in your specialty.

Selective reading is carried out in a 2-speed mode: text that does not carry significant information is scanned quickly, very quickly, without memorization, without analysis and conclusions - to essential information. By essential words and phrases, you evaluate the significance of information. Next, you apply a different reading strategy, similar to the analytical reading strategy, here line-by-line movement of the gaze, and return movements, etc. are possible. It is necessary to concentrate as much as possible in order to remember this text, comprehending it.

The exploratory reading strategy will help you quickly find the answer to a specific question.

With such a search, you set yourself the goal: to find the information you are interested in. Unlike selective reading, you don't judge the relevance of information, you just search. For search reading, a two-speed mode is used, similar to selective reading.

For search reading, a two-speed mode is used, similar to selective reading.

Try to analyze and remember the emotional state that arises in you when reading like this - the state of maximum realization of all your abilities, an elevated state in which the text is assimilated at high speeds in the best possible way. If you are having difficulty choosing a search reading strategy, this means that you have a narrow field of simultaneous perception of the text.

For an untrained reader, the field of simultaneous perception of the text is equal to the field of clear vision. But if we consider that we see at 120-160 about around us, and the field of clear vision is only 5-6 about , then it becomes clear that one should improve, perceiving more and more text in an instant, and you succeed in exploratory reading. But the simple ability to perceive visual information from a wide field may not turn into the skill of expanding the field of perception when reading. It is necessary to additionally develop an attitude (habit) to expand the field of perception when reading. This is an element of qualified reading. In order for the expansion of the field of perception during reading to become a habit, such a skill has been developed, always during search reading it is necessary not only to see paragraphs, semantic blocks, semantic integral units, but also to remember the need to expand the field of perception.

It is necessary to additionally develop an attitude (habit) to expand the field of perception when reading. This is an element of qualified reading. In order for the expansion of the field of perception during reading to become a habit, such a skill has been developed, always during search reading it is necessary not only to see paragraphs, semantic blocks, semantic integral units, but also to remember the need to expand the field of perception.

In general, the expansion of the field of simultaneous perception of the text, and at the same time the expansion of the field of clear vision, is a serious task of the final stage of teaching rational reading. Your task is to achieve simultaneous perception of a whole line of text using anticipation and a well-developed extended field of text perception. The development of the reader's vocabulary will greatly contribute to the expansion of the field of simultaneous perception of the text, and at the same time the development of the strategy of search reading.