Story of the fly

The Fly

Published in 1922, The Fly is often heralded as one of Katherine Mansfield's finest short stories. But it does not reward lazy readers! Your enjoyment of this story depends on how well you read the story. So please take your time and read it with careful attention. Readers will wish to contemplate the symbolism of the fly, and notice that the ending of the story plays on one of Woodfield's problems mentioned near the story's beginning. This story is featured in our collection of World War One Literature.

A.J.E. Terzi, Ox Warble Fly, in ink, 1919

" Y'ARE very snug in here," piped old Mr. Woodifield, and he peered out of the great, green leather armchair by his friend the boss's desk as a baby peers out of its pram. His talk was over; it was time for him to be off. But he did not want to go. Since he had retired, since his... stroke, the wife and the girls kept him boxed up in the house every day of the week except Tuesday.

On Tuesday he was dressed and brushed and allowed to cut back to the City for the day. Though what he did there the wife and girls couldn't imagine. Made a nuisance of himself to his friends, they supposed ... Well, perhaps so. All the same, we cling to our last pleasures as the tree clings to its last leaves. So there sat old Woodifield, smoking a cigar and staring almost greedily at the boss, who rolled in his office chair, stout, rosy, five years older than he, and still going strong, still at the helm. It did one good to see him. Wistfully, admiringly, the old voice added, " It's snug in here, upon my word ! "

" Yes, it's comfortable enough," agreed the boss, and he flipped the Financial Times with a paper-knife. As a matter of fact he was proud of his room ; he liked to have it admired, especially by old Woodifield. It gave him a feeling of deep, solid satisfaction to be planted there in the midst of it in full view of that frail old figure in the muffler.

" I've had it done up lately," he explained, as he had explained for the past—how many ?— weeks. " New carpet," and he pointed to the bright red carpet with a pattern of large white rings. " New furniture," and he nodded towards the massive bookcase and the table with legs like twisted treacle. " Electric heating ! " He waved almost exultantly towards the five transparent, pearly sausages glowing so softly in the tilted copper pan.

" New carpet," and he pointed to the bright red carpet with a pattern of large white rings. " New furniture," and he nodded towards the massive bookcase and the table with legs like twisted treacle. " Electric heating ! " He waved almost exultantly towards the five transparent, pearly sausages glowing so softly in the tilted copper pan.

But he did not draw old Woodifield's attention to the photograph over the table of a grave-looking boy in uniform standing in one of those spectral photographers' parks with photographers' storm-clouds behind him. It was not new. It had been there for over six years.

" There was something I wanted to tell you," said old Woodifield, and his eyes grew dim remembering. " Now what was it ? I had it in my mind when I started out this morning." His hands began to tremble, and patches of red showed above his beard.

Poor old chap, he's on his last pins, thought the boss. And, feeling kindly, he winked at the old man, and said jokingly, " I tell you what. I've got a little drop of something here that'll do you good before you go out into the cold again. It's beautiful stuff. It wouldn't hurt a child." He took a key off his watch-chain, unlocked a cupboard below his desk, and drew forth a dark, squat bottle. " That's the medicine," said he. " And the man from whom I got it told me on the strict Q.T. it came from the cellars at Windsor Cassel."

I've got a little drop of something here that'll do you good before you go out into the cold again. It's beautiful stuff. It wouldn't hurt a child." He took a key off his watch-chain, unlocked a cupboard below his desk, and drew forth a dark, squat bottle. " That's the medicine," said he. " And the man from whom I got it told me on the strict Q.T. it came from the cellars at Windsor Cassel."

Old Woodifield's mouth fell open at the sight. He couldn't have looked more surprised if the boss had produced a rabbit.

" It's whisky, ain't it ? " he piped, feebly.

The boss turned the bottle and lovingly showed him the label. Whisky it was.

" D'you know," said he, peering up at the boss wonderingly, " they won't let me touch it at home." And he looked as though he was going to cry.

" Ah, that's where we know a bit more than the ladies," cried the boss, swooping across for two tumblers that stood on the table with the water-bottle, and pouring a generous finger into each. " Drink it down. It'll do you good. And don't put any water with it. It's sacrilege to tamper with stuff like this. Ah ! " He tossed off his, pulled out his handkerchief, hastily wiped his moustaches, and cocked an eye at old Woodifield, who was rolling his in his chaps.

" Drink it down. It'll do you good. And don't put any water with it. It's sacrilege to tamper with stuff like this. Ah ! " He tossed off his, pulled out his handkerchief, hastily wiped his moustaches, and cocked an eye at old Woodifield, who was rolling his in his chaps.

The old man swallowed, was silent a moment, and then said faintly, " It's nutty ! "

But it warmed him ; it crept into his chill old brain—he remembered.

" That was it," he said, heaving himself out of his chair. " I thought you'd like to know. The girls were in Belgium last week having a look at poor Reggie's grave, and they happened to come across your boy's. They're quite near each other, it seems."

Old Woodifield paused, but the boss made no reply. Only a quiver in his eyelids showed that he heard.

" The girls were delighted with the way the place is kept," piped the old voice. " Beautifully looked after. Couldn't be better if they were at home. You've not been across, have yer ? "

" No, no ! " For various reasons the boss had not been across.

" There's miles of it," quavered old Woodifield, " and it's all as neat as a garden. Flowers growing on all the graves. Nice broad paths." It was plain from his voice how much he liked a nice broad path.

The pause came again. Then the old man brightened wonderfully.

" D'you know what the hotel made the girls pay for a pot of jam ? " he piped. " Ten - francs! Robbery, I call it. It was a little pot, so Gertrude says, no bigger than a half-crown. And she hadn't taken more than a spoonful when they charged her ten francs. Gertrude brought the pot away with her to teach 'em a lesson. Quite right, too ; it's trading on our feelings. They think because we're over there having a look round we're ready to pay anything. That's what it is." And he turned towards the door.

" Quite right, quite right! " cried the boss, though what was quite right he hadn't the least idea. He came round by his desk, followed the shuffling footsteps to the door, and saw the old fellow out. Woodifield was gone.

For a long moment the boss stayed, staring at nothing, while the grey-haired office messenger, watching him, dodged in and out of his cubby hole like a dog that expects to be taken for a run. Then : " I'll see nobody for half an hour, Macey," said the boss. " Understand ? Nobody at all."

" Very good, sir."

The door shut, the firm heavy steps recrossed the bright carpet, the fat body plumped down in the spring chair, and leaning forward, the boss covered his face with his hands. He wanted, he intended, he had arranged to weep...

It had been a terrible shock to him when old Woodifield sprang that remark upon him about the boy's grave. It was exactly as though the earth had opened and he had seen the boy lying there with Woodifield's girls staring down at him. For it was strange. Although over six years had passed away, the boss never thought of the boy except as lying unchanged, unblemished in his uniform, asleep for ever. " My son ! " groaned the boss. But no tears came yet. In the past, in the first months and even years after the boy's death, he had only to say those words to be overcome by such grief that nothing short of a violent fit of weeping could relieve him. Time, he had declared then, he had told everybody, could make no difference. Other men perhaps might recover, might live their loss down, but not he. How was it possible ? His boy was an only son. Ever since his birth the boss had worked at building up this business for him ; it had no other meaning if it was not for the boy. Life itself had come to have no other meaning. How on earth could he have slaved, denied himself, kept going all those years without the promise for ever before him of the boy's stepping into his shoes and carrying on where he left off ?

In the past, in the first months and even years after the boy's death, he had only to say those words to be overcome by such grief that nothing short of a violent fit of weeping could relieve him. Time, he had declared then, he had told everybody, could make no difference. Other men perhaps might recover, might live their loss down, but not he. How was it possible ? His boy was an only son. Ever since his birth the boss had worked at building up this business for him ; it had no other meaning if it was not for the boy. Life itself had come to have no other meaning. How on earth could he have slaved, denied himself, kept going all those years without the promise for ever before him of the boy's stepping into his shoes and carrying on where he left off ?

And that promise had been so near being fulfilled. The boy had been in the office learning the ropes for a year before the war. Every morning they had started off together ; they had come back by the same train. And what congratulations he had received as the boy's father ! No wonder ; he had taken to it marvellously. As to his popularity with the staff, every man jack of them down to old Macey couldn't make enough of the boy. And he wasn't in the least spoilt. No, he was just his bright, natural self, with the right word for everybody, with that boyish look and his habit of saying, " Simply splendid ! "

As to his popularity with the staff, every man jack of them down to old Macey couldn't make enough of the boy. And he wasn't in the least spoilt. No, he was just his bright, natural self, with the right word for everybody, with that boyish look and his habit of saying, " Simply splendid ! "

But all that was over and done with as though it never had been. The day had come when Macey had handed him the telegram that brought the whole place crashing about his head. " Deeply regret to inform you ..." And he had left the office a broken man, with his life in ruins.

Six years ago, six years ... How quickly time passed ! It might have happened yesterday. The boss took his hands from his face ; he was puzzled. Something seemed to be wrong with him. He wasn't feeling as he wanted to feel. He decided to get up and have a look at the boy's photograph. But it wasn't a favourite photograph of his; the expression was unnatural. It was cold, even stern-looking. The boy had never looked like that.

At that moment the boss noticed that a fly had fallen into his broad inkpot, and was trying feebly but desperately to clamber out again. Help ! help ! said those struggling legs. But the sides of the inkpot were wet and slippery ; it fell back again and began to swim. The boss took up a pen, picked the fly out of the ink, and shook it on to a piece of blotting-paper. For a fraction of a second it lay still on the dark patch that oozed round it. Then the front legs waved, took hold, and, pulling its small, sodden body up it began the immense task of cleaning the ink from its wings. Over and under, over and under, went a leg along a wing, as the stone goes over and under the scythe. Then there was a pause, while the fly, seeming to stand on the tips of its toes, tried to expand first one wing and then the other. It succeeded at last, and, sitting down, it began, like a minute cat, to clean its face. Now one could imagine that the little front legs rubbed against each other lightly, joyfully. The horrible danger was over ; it had escaped ; it was ready for life again.

The horrible danger was over ; it had escaped ; it was ready for life again.

But just then the boss had an idea. He plunged his pen back into the ink, leaned his thick wrist on the blotting paper, and as the fly tried its wings down came a great heavy blot. What would it make of that ? What indeed ! The little beggar seemed absolutely cowed, stunned, and afraid to move because of what would happen next. But then, as if painfully, it dragged itself forward. The front legs waved, caught hold, and, more slowly this time, the task began from the beginning.

He's a plucky little devil, thought the boss, and he felt a real admiration for the fly's courage. That was the way to tackle things ; that was the right spirit. Never say die ; it was only a question of ... But the fly had again finished its laborious task, and the boss had just time to refill his pen, to shake fair and square on the new-cleaned body yet another dark drop. What about it this time ? A painful moment of suspense followed. But behold, the front legs were again waving ; the boss felt a rush of relief. He leaned over the fly and said to it tenderly, " You artful little b . . ." And he actually had the brilliant notion of breathing on it to help the drying process. All the same, there was something timid and weak about its efforts now, and the boss decided that this time should be the last, as he dipped the pen deep into the inkpot.

But behold, the front legs were again waving ; the boss felt a rush of relief. He leaned over the fly and said to it tenderly, " You artful little b . . ." And he actually had the brilliant notion of breathing on it to help the drying process. All the same, there was something timid and weak about its efforts now, and the boss decided that this time should be the last, as he dipped the pen deep into the inkpot.

It was. The last blot fell on the soaked blotting-paper, and the draggled fly lay in it and did not stir. The back legs were stuck to the body; the front legs were not to be seen.

" Come on," said the boss. " Look sharp ! " And he stirred it with his pen—in vain. Nothing happened or was likely to happen. The fly was dead.

The boss lifted the corpse on the end of the paper-knife and flung it into the waste-paper basket. But such a grinding feeling of wretchedness seized him that he felt positively frightened. He started forward and pressed the bell for Macey.

" Bring me some fresh blotting-paper," he said, sternly, " and look sharp about it. " And while the old dog padded away he fell to wondering what it was he had been thinking about before. What was it ? It was... He took out his handkerchief and passed it inside his collar. For the life of him he could not remember.

" And while the old dog padded away he fell to wondering what it was he had been thinking about before. What was it ? It was... He took out his handkerchief and passed it inside his collar. For the life of him he could not remember.

The Fly was featured as The Short Story of the Day on Sun, Jan 09, 2022

The Fly is featured in our collection of Short Stories for High School I

Add The Fly to your library.

Return to the Katherine Mansfield library , or . . . Read the next short story; The Garden Party

‘The Fly’ by Katherine Mansfield

In this short story, a boss is visited by an old friend in his London office.

The Fly

Y’are very snug in here,’ piped old Mr. Woodifield, and peered out of the great, green-leather armchair by his friend the boss’s desk as a baby peers out of its pram. His talk was over; it was time for him to be off. But he did not want to go. Since he had retired, since his…stroke, the wife and the girls kept him boxed up in the house every day of the week except Tuesday. On Tuesday he was dressed and brushed and allowed to cut back to the City for the day. Though what he did there the wife and girls couldn’t imagine. Made a nuisance of himself to his friends, they supposed...Well, perhaps so. All the same, we cling to our last pleasures as the tree clings to its last leaves. So there sat old Woodifield, smoking a cigar and staring almost greedily at the boss, who rolled in his office chair, stout, rosy, five years older than he, and still going strong, still at the helm. It did one good to see him.

Since he had retired, since his…stroke, the wife and the girls kept him boxed up in the house every day of the week except Tuesday. On Tuesday he was dressed and brushed and allowed to cut back to the City for the day. Though what he did there the wife and girls couldn’t imagine. Made a nuisance of himself to his friends, they supposed...Well, perhaps so. All the same, we cling to our last pleasures as the tree clings to its last leaves. So there sat old Woodifield, smoking a cigar and staring almost greedily at the boss, who rolled in his office chair, stout, rosy, five years older than he, and still going strong, still at the helm. It did one good to see him.

Wistfully, admiringly, the old voice added, ‘It’s snug in here, upon my word!’

‘Yes, it’s comfortable enough,’ agreed the boss, and he flipped the Financial Times with a paper-knife. As a matter of fact he was proud of his room; he liked to have it admired, especially by old Woodifield. It gave him a feeling of deep, solid satisfaction to be planted there in the midst of it in full view of that frail old figure in the muffler.

‘I’ve had it done up lately,’ he explained, as he had explained for the past how many weeks.

‘New carpet,’ and he pointed to the bright red carpet with a pattern of large white rings. ‘New furniture,’ and he nodded towards the massive bookcase and the table with legs like twisted treacle. ‘Electric heating!’ He waved almost exultantly towards the five transparent, pearly sausages glowing so softly in the tilted copper pan.

But he did not draw old Woodifield’s attention to the photograph over the table of a grave-looking boy in uniform standing in one of those spectral photographers’ parks with photographers’ storm-clouds behind him. It was not new. It had been there for over six years.

‘There was something I wanted to tell you,’ said old Woodifield, and his eyes grew dim remembering. ‘Now what was it? I had it in my mind when I started out this morning.’ His hands began to tremble, and patches of red showed above his beard.

Poor old chap, he’s on his last pins, thought the boss. And, feeling kindly, he winked at the old man, and said jokingly,

And, feeling kindly, he winked at the old man, and said jokingly,

‘I tell you what. I’ve got a little drop of something here that’ll do you good before you go out into the cold again. It’s beautiful stuff. It wouldn’t hurt a child.’ He took a key off his watch-chain, unlocked a cupboard below his desk, and drew forth a dark, squat bottle. ‘That’s the medicine,’ said he. ‘And the man from whom I got it told me on the strict Q.T. it came from the cellars at Windsor Castle.’

Old Woodifield’s mouth fell open at the sight. He couldn’t have looked more surprised if the boss had produced a rabbit.

‘It’s whisky, ain’t it?’ he piped feebly.

The boss turned the bottle and lovingly showed him the label. Whisky it was.

‘D’you know,’ said he, peering up at the boss wonderingly, ‘they won’t let me touch it at home.’ And he looked as though he was going to cry.

‘Ah, that’s where we know a bit more than the ladies,’ cried the boss, swooping across for two tumblers that stood on the table with the water-bottle, and pouring a generous finger into each. ‘Drink it down. It’ll do you good. And don’t put any water with it. It’s sacrilege to tamper with stuff like this. Ah!’ He tossed off his, pulled out his handkerchief, hastily wiped his moustaches, and cocked an eye at old Woodifield, who was rolling his in his chaps.

‘Drink it down. It’ll do you good. And don’t put any water with it. It’s sacrilege to tamper with stuff like this. Ah!’ He tossed off his, pulled out his handkerchief, hastily wiped his moustaches, and cocked an eye at old Woodifield, who was rolling his in his chaps.

The old man swallowed, was silent a moment, and then said faintly, ‘It’s nutty!’

But it warmed him; as it crept into his chill old brain he remembered.

‘That was it,’ he said, heaving himself out of his chair.

‘I thought you’d like to know. The girls were in Belgium last week having a look at poor Reggie’s grave, and they happened to come across your boy’s. They’re quite near each other, it seems.’

Old Woodifield paused, but the boss made no reply. Only a quiver in his eyelids showed that he heard.

‘The girls were delighted with the way the place is kept,’ piped the old voice. ‘Beautifully looked after. Couldn’t be better if they were at home. You’ve not been across, have yer?’

‘No, no!’ For various reasons the boss had not been across.

‘There’s miles of it,’ quavered old Woodifield, ‘and it’s all as neat as a garden. Flowers growing on all the graves. Nice broad paths.’ It was plain from his voice how much he liked a nice broad path.

The pause came again. Then the old man brightened wonderfully.

‘D’you know what the hotel made the girls pay for a pot of jam?’ he piped. ‘Ten francs! Robbery, I call it. It was a little pot, so Gertrude says, no bigger than a half-crown. And she hadn’t taken more than a spoonful when they charged her ten francs. Gertrude brought the pot away with her to teach ‘em a lesson. Quite right, too; it’s trading on our feelings. They think because we’re over there having a look round we’re ready to pay anything. That’s what it is.’ And he turned towards the door.

‘Quite right, quite right!’ cried the boss, though what was quite right he hadn’t the least idea. He came round by his desk, followed the shuffling footsteps to the door, and saw the old fellow out. Woodifield was gone.

For a long moment the boss stayed, staring at nothing, while the grey-haired office messenger, watching him, dodged in and out of his cubby-hole like a dog that expects to be taken for a run. Then: ‘I’ll see nobody for half an hour, Macey,’ said the boss. ‘Understand! Nobody at all.’

‘Very good, sir.’

The door shut, the firm heavy steps recrossed the bright carpet, the fat body plumped down in the spring chair, and leaning forward, the boss covered his face with his hands. He wanted, he intended, he had arranged to weep...

It had been a terrible shock to him when old Woodifield sprang that remark upon him about the boy’s grave. It was exactly as though the earth had opened and he had seen the boy lying there with Woodifield’s girls staring down at him. For it was strange. Although over six years had passed away, the boss never thought of the boy except as lying unchanged, unblemished in his uniform, asleep for ever. ‘My son!’ groaned the boss. But no tears came yet. In the past, in the first months and even years after the boy’s death, he had only to say those words to be overcome by such grief that nothing short of a violent fit of weeping could relieve him. Time, he had declared then, he had told everybody, could make no difference. Other men perhaps might recover, might live their loss down, but not he. How was it possible! His boy was an only son. Ever since his birth the boss had worked at building up this business for him; it had no other meaning if it was not for the boy. Life itself had come to have no other meaning. How on earth could he have slaved, denied himself, kept going all those years without the promise for ever before him of the boy’s stepping into his shoes and carrying on where he left off?

In the past, in the first months and even years after the boy’s death, he had only to say those words to be overcome by such grief that nothing short of a violent fit of weeping could relieve him. Time, he had declared then, he had told everybody, could make no difference. Other men perhaps might recover, might live their loss down, but not he. How was it possible! His boy was an only son. Ever since his birth the boss had worked at building up this business for him; it had no other meaning if it was not for the boy. Life itself had come to have no other meaning. How on earth could he have slaved, denied himself, kept going all those years without the promise for ever before him of the boy’s stepping into his shoes and carrying on where he left off?

And that promise had been so near being fulfilled. The boy had been in the office learning the ropes for a year before the war. Every morning they had started off together; they had come back by the same train. And what congratulations he had received as the boy’s father! No wonder; he had taken to it marvellously. As to his popularity with the staff, every man jack of them down to old Macey couldn’t make enough of the boy. And he wasn’t in the least spoilt. No, he was just his bright natural self, with the right word for everybody, with that boyish look and his habit of saying, ‘Simply splendid!’

As to his popularity with the staff, every man jack of them down to old Macey couldn’t make enough of the boy. And he wasn’t in the least spoilt. No, he was just his bright natural self, with the right word for everybody, with that boyish look and his habit of saying, ‘Simply splendid!’

But all that was over and done with as though it never had been. The day had come when Macey had handed him the telegram that brought the whole place crashing about his head. ‘Deeply regret to inform you ...’ And he had left the office a broken man, with his life in ruins.

Six years ago, six years.... How quickly time passed! It might have happened yesterday. The boss took his hands from his face; he was puzzled. Something seemed to be wrong with him. He wasn’t feeling as he wanted to feel. He decided to get up and have a look at the boy’s photograph. But it wasn’t a favourite photograph of his; the expression was unnatural. It was cold, even stern-looking. The boy had never looked like that.

At that moment the boss noticed that a fly had fallen into his broad inkpot, and was trying feebly but desperately to clamber out again. Help! Help! said those struggling legs. But the sides of the inkpot were wet and slippery; it fell back again and began to swim. The boss took up a pen, picked the fly out of the ink, and shook it on to a piece of blotting-paper. For a fraction of a second it lay still on the dark patch that oozed round it. Then the front legs waved, took hold, and, pulling its small, sodden body up, it began the immense task of cleaning the ink from its wings. Over and under, over and under, went a leg along a wing as the stone goes over and under the scythe. Then there was a pause, while the fly, seeming to stand on the tips of its toes, tried to expand first one wing and then the other. It succeeded at last, and, sitting down, it began, like a minute cat, to clean its face. Now one could imagine that the little front legs rubbed against each other lightly, joyfully. The horrible danger was over; it had escaped; it was ready for life again.

The horrible danger was over; it had escaped; it was ready for life again.

But just then the boss had an idea. He plunged his pen back into the ink, leaned his thick wrist on the blotting-paper, and as the fly tried its wings down came a great heavy blot. What would it make of that! What indeed! The little beggar seemed absolutely cowed, stunned, and afraid to move because of what would happen next. But then, as if painfully, it dragged itself forward. The front legs waved, caught hold, and, more slowly this time, the task began from the beginning.

He’s a plucky little devil, thought the boss, and he felt a real admiration for the fly’s courage. That was the way to tackle things; that was the right spirit. Never say die; it was only a question of... But the fly had again finished its laborious task, and the boss had just time to refill his pen, to shake fair and square on the new-cleaned body yet another dark drop. What about it this time? A painful moment of suspense followed. But behold, the front legs were again waving; the boss felt a rush of relief. He leaned over the fly and said to it tenderly, ‘You artful little b...’ And he actually had the brilliant notion of breathing on it to help the drying process. All the same, there was something timid and weak about its efforts now, and the boss decided that this time should be the last, as he dipped the pen deep into the inkpot.

But behold, the front legs were again waving; the boss felt a rush of relief. He leaned over the fly and said to it tenderly, ‘You artful little b...’ And he actually had the brilliant notion of breathing on it to help the drying process. All the same, there was something timid and weak about its efforts now, and the boss decided that this time should be the last, as he dipped the pen deep into the inkpot.

It was. The last blot fell on the soaked blotting-paper, and the draggled fly lay in it and did not stir. The back legs were stuck to the body; the front legs were not to be seen.

‘Come on,’ said the boss. ‘Look sharp!’ And he stirred it with his pen in vain. Nothing happened or was likely to happen. The fly was dead.

The boss lifted the corpse on the end of the paper-knife and flung it into the waste-paper basket. But such a grinding feeling of wretchedness seized him that he felt positively frightened. He started forward and pressed the bell for Macey.

‘Bring me some fresh blotting-paper,’ he said sternly, ‘and look sharp about it. ’ And while the old dog padded away he fell to wondering what it was he had been thinking about before. What was it? It was... He took out his handkerchief and passed it inside his collar. For the life of him he could not remember.

’ And while the old dog padded away he fell to wondering what it was he had been thinking about before. What was it? It was... He took out his handkerchief and passed it inside his collar. For the life of him he could not remember.

Useful Resources

Great Writers Inspire on Katherine Mansfield

Open educational resources on Mansfield, created by Oxford academics.

Great Writers Inspire on Modernism

Read an essay by Rebecca Beasley on modernist literature and access more open educational resources.

The Katherine Mansfield Society Resources

About the Contributor

Elleke Boehmer is a novelist, critic and short story writer. She has been a passionate admirer of Katherine Mansfield's work since first she read 'The Garden Party' aged about thirteen. She is Professor of World Literature in English at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. She is the author of Colonial and Postcolonial Literature (1995, 2005), Empire, the National and the Postcolonial (2002), Stories of Women (2005), Postcolonial Poetics (2018), and a widely translated biography of Nelson Mandela (2008). Her book Indian Arrivals 1870-1915 (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990) and The Shouting in the Dark (2015) which won the triennial Olive Schreiner award (2018). To the Volcano, a second collection of short stories, appeared in 2019. Elleke Boehmer is the Director of the Oxford Centre for Life Writing and Writers Make Worlds.

Her book Indian Arrivals 1870-1915 (2015) was the winner of the biennial ESSE 2015-16 Prize. She is the author of five novels including Screens against the Sky (1990) and The Shouting in the Dark (2015) which won the triennial Olive Schreiner award (2018). To the Volcano, a second collection of short stories, appeared in 2019. Elleke Boehmer is the Director of the Oxford Centre for Life Writing and Writers Make Worlds.

Dilogy about the Fly

- Have you ever heard about the political views of the fly? I didn't hear either. Insects... don't have politics. They are very... cruel. No sympathy, no compromise. We cannot trust insects. I would like to be the first ... insect politician ...

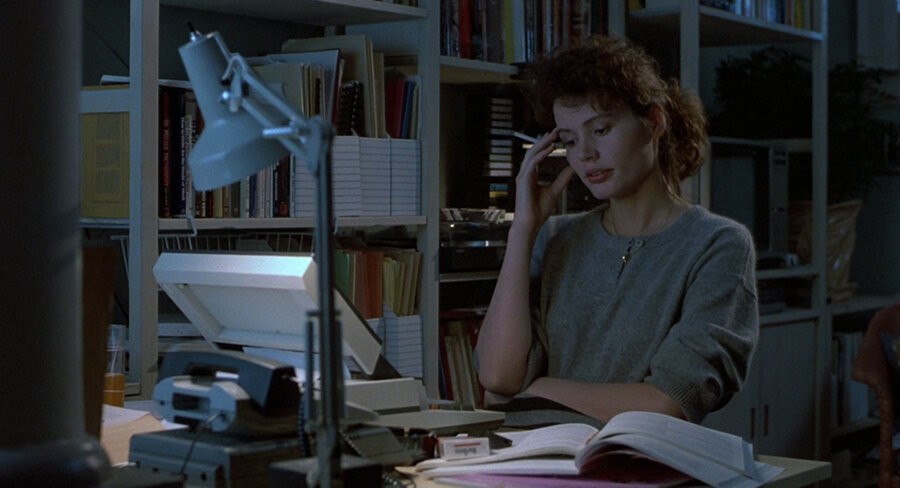

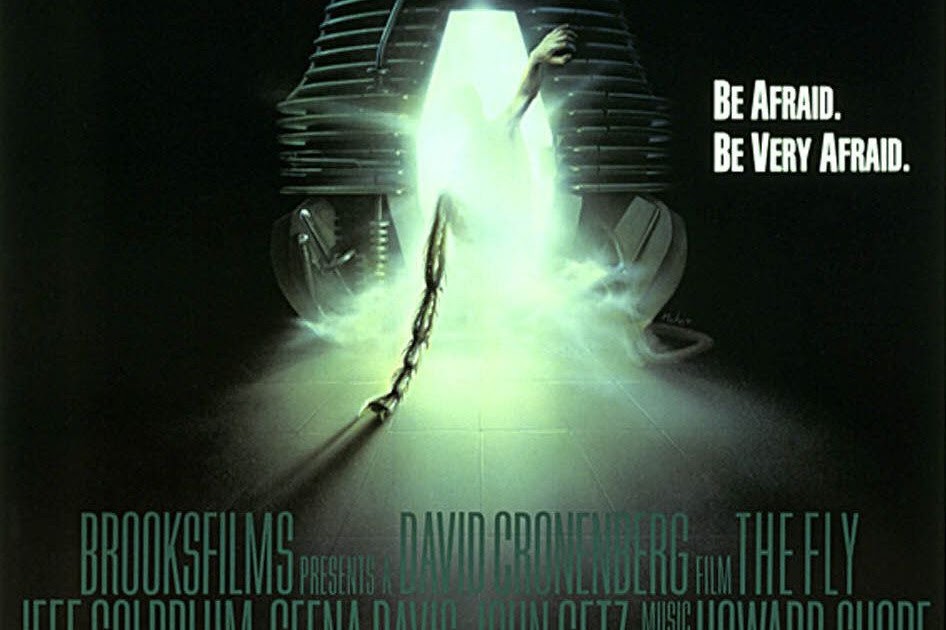

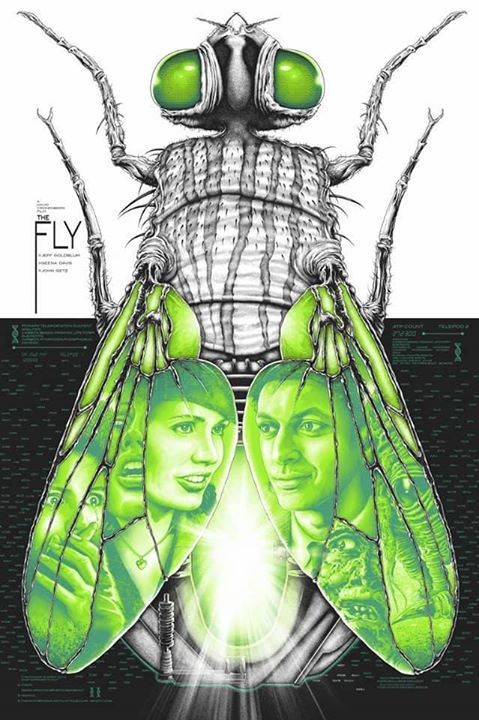

The Fly (1986)

short story "The Fly" by French writer Georges Langelan. Langelan himself is an extraordinary person; during the Second World War, he was sent to occupied France as a scout; was captured by the Nazis and sentenced to death, but escaped. His story also turned out to be extraordinary - about a scientist who accidentally "crossed" himself with a fly, resulting in two organisms - a man turning into a fly and ... an intelligent fly with a human head. A year later, the story was filmed by Kurt Neumann, retaining the plot plot. One of the roles in the film was played by the famous Vincent Price; the film was so successful that it was followed by two sequels (Return of the Fly, 1959 and Curse of the Fly, 1965).

His story also turned out to be extraordinary - about a scientist who accidentally "crossed" himself with a fly, resulting in two organisms - a man turning into a fly and ... an intelligent fly with a human head. A year later, the story was filmed by Kurt Neumann, retaining the plot plot. One of the roles in the film was played by the famous Vincent Price; the film was so successful that it was followed by two sequels (Return of the Fly, 1959 and Curse of the Fly, 1965).

30 years later, in the mid-80s, the idea of shooting a remake arose. It should be noted that the film could turn out completely different - David Cronenberg planned to shoot the action movie “Remember Everything” for Dino De Laurentiis (the same one with Schwarzenegger), and director Robert Birman undertook to shoot “The Fly”. However, fate decreed otherwise. The sudden death of Birman's daughter temporarily interrupted his film work, and Cronenberg quarreled with De Laurentiis, as a result of which Paul Verhoeven shot Recall Everything, and Cronenberg ended up in the director's chair on the set of The Fly. This determined the fate of the film - after all, Cronenberg was always interested in the darkest sides of the human soul, physical and psychological flaws, so the story of the unfortunate experimenter, who turns into a vile monster day after day, suited him like a glove. Cronenberg made a number of important decisions - he abandoned the idea of \u200b\u200ba "second organism", and focused on the frightening metamorphoses of the protagonist. At the same time, the director came up with a "ribbed" design of teleporters, inspired by the shapes of ... a vintage Ducati motorcycle.

This determined the fate of the film - after all, Cronenberg was always interested in the darkest sides of the human soul, physical and psychological flaws, so the story of the unfortunate experimenter, who turns into a vile monster day after day, suited him like a glove. Cronenberg made a number of important decisions - he abandoned the idea of \u200b\u200ba "second organism", and focused on the frightening metamorphoses of the protagonist. At the same time, the director came up with a "ribbed" design of teleporters, inspired by the shapes of ... a vintage Ducati motorcycle.

The choice of Jeff Goldblum for the title role does not seem the most obvious. Nevertheless, although I don’t like the work of this actor in all films, for The Fly he was a hit in the bull's-eye: intelligent, witty, beautifully built - it is simply impossible to imagine him as a vile insect. And yet, he played this transformation - not only with the help of complex makeup, but also with acting. By the way, the role of journalist Veronica, who falls in love with a scientist, went to Geena Davis, not least due to the fact that at 19She dated Goldblum in 1985 (ironically, they got married and divorced by the time the sequel came out). Result? A real “screen chemistry” sparks between the characters - they do not play love, but live it for real. And the more terrible is the nightmare with which this “love story” ends on the screen. The third peak of the plot triangle in the film was John Getz - I rarely saw this actor anywhere, but in The Fly he got an extremely interesting role. His character is at first a typical "bad guy": being a "former" journalist, he steals her sensational material, is jealous of her, and in general, in every possible way is mean. All the more surprising is his transformation in the finale into a hero who sacrifices himself (more precisely, some parts of his body) to save his beloved. Not always in a "scary" movie you will see such a multifaceted character. Cronenberg himself starred in the film in a cameo role ... a gynecologist (the choice is not accidental - somehow Martin Scorsese told him that the director looks like a doctor).

Result? A real “screen chemistry” sparks between the characters - they do not play love, but live it for real. And the more terrible is the nightmare with which this “love story” ends on the screen. The third peak of the plot triangle in the film was John Getz - I rarely saw this actor anywhere, but in The Fly he got an extremely interesting role. His character is at first a typical "bad guy": being a "former" journalist, he steals her sensational material, is jealous of her, and in general, in every possible way is mean. All the more surprising is his transformation in the finale into a hero who sacrifices himself (more precisely, some parts of his body) to save his beloved. Not always in a "scary" movie you will see such a multifaceted character. Cronenberg himself starred in the film in a cameo role ... a gynecologist (the choice is not accidental - somehow Martin Scorsese told him that the director looks like a doctor).

The result is well known: "Fly" became a hit at the box office (including the USSR in the era of video salons). This is a typical “scary” movie with monsters and “blood”, but at the same time it is also a typical Cronenberg film that raises acute social problems, including the topic of the spread of AIDS, mutations, man-made disasters ... The special effects in the film were simply amazing for that time (“the toxic concoction that the man-fly “shoots” at people was made from a mixture of milk, eggs and honey), so it even makes sense that the sequel to the film, filmed in 1989, they entrusted Chris Wallace, who was responsible for the special effects on The Fly.

This is a typical “scary” movie with monsters and “blood”, but at the same time it is also a typical Cronenberg film that raises acute social problems, including the topic of the spread of AIDS, mutations, man-made disasters ... The special effects in the film were simply amazing for that time (“the toxic concoction that the man-fly “shoots” at people was made from a mixture of milk, eggs and honey), so it even makes sense that the sequel to the film, filmed in 1989, they entrusted Chris Wallace, who was responsible for the special effects on The Fly.

Although such venerable (future) directors and screenwriters as Frank Darabont and Mick Garris had a hand in the script of "Flies 2", the fact remains that this is no longer a Cronenberg film. This does not mean that the film is bad - it's just "a completely different story." Veronica dies in the sequel at the very beginning (for obvious reasons, this role is already played by another actress - Saffron Henderson), giving birth to the son of the Fly Man: Martin Brundle. He looks like an ordinary child, only he grows by leaps and bounds, and by the age of five he turns into an adult man. All this time, the insidious head of the corporation Bartok keeps Martin under observation, looking forward to when he will turn into a fly, giving science an uncountable number of discoveries.

He looks like an ordinary child, only he grows by leaps and bounds, and by the age of five he turns into an adult man. All this time, the insidious head of the corporation Bartok keeps Martin under observation, looking forward to when he will turn into a fly, giving science an uncountable number of discoveries.

It is clear that this is no longer a story about a love triangle and the fear of infection, this is a "bipolar" system: Martin against Bartok, a hero against a megacorporation, a man against the control of the system. And from this point of view, the film looks quite worthy, especially the part about the short "childhood" of the hero, who is forced to consider his father a cruel and hypocritical experimenter. As soon as the hero turns into a Very Big Fly, and the horror movie begins directly, the degree of interest in the film paradoxically drops - after all, the highlight of the "Fly" was not in the spilled blood, but in the philosophical Kafkaesque overtones. In addition, today the special effects with the "puppet" fly (and at the same time antediluvian computers with monitors) are so outdated that the film seems more archaic than the same "Fly". The key idea of Cronenberg's film has also changed - in the first "Fly" the hero turned into a monster not only externally, but also internally (in the final scene he drags his "beloved" to a teleport to merge with her genes there), which creates an additional dimension of horror. In "Fly 2", on the contrary, Martin retains a semblance of humanity even with six legs: he strokes the dog, protects the girl ... Yes, and the happy ending in this kind of movie looks fake.

The key idea of Cronenberg's film has also changed - in the first "Fly" the hero turned into a monster not only externally, but also internally (in the final scene he drags his "beloved" to a teleport to merge with her genes there), which creates an additional dimension of horror. In "Fly 2", on the contrary, Martin retains a semblance of humanity even with six legs: he strokes the dog, protects the girl ... Yes, and the happy ending in this kind of movie looks fake.

Only John Getz migrated from the previous film to the sequel, but his role is episodic, and, by and large, unprincipled. Seth Brundle's son, Martin, is played by Eric Stoltz. In 1985, he began acting as Marty McFly in the famous Back to the Future trilogy, but after the start of filming he was replaced by Michael J. Fox. So if you want to see what Marty McFly would look like if Stoltz played him, watch Fly 2. His hero is a "big child", vulnerable and naive. Alas, the make-up artist had more to do with the transformation of his "white and fluffy" character into a "black and furry" fly than Stolz's acting. It seems to me that this time the special effects team was more successful not with "insect" mutations, but with a creepy monster dog (a victim of Bartok's experiments) and a disgusting monster that appears at the very end. Even realizing that these are dolls, it still becomes uncomfortable.

It seems to me that this time the special effects team was more successful not with "insect" mutations, but with a creepy monster dog (a victim of Bartok's experiments) and a disgusting monster that appears at the very end. Even realizing that these are dolls, it still becomes uncomfortable.

Thus, moving away from the "Cronenberg line", the nascent franchise immediately reached a dead end - "Fly 3" did not appear. But now there is a preparation for a new remake. Whether the new film will be the same step forward that the 1986 film was in relation to the 1958 original, only time will tell. Moreover, David Cronenberg should be in the director's chair again!

- I am an insect who dreamed that he was a man and liked it. But the dream ended... and the insect woke up!

“Mukha” (1986)

What were flies 50 million years ago-DW-12.03.2021

Fossibility of a fly-knitted family, found in the German career Messel photos: Senckenberg-heshalschaft für NATURFORFUNG dpa/picture alliance

Science

Maxim Nelyubin

March 12, 2021

The German Messel Quarry once again delighted fossil lovers and surprised scientists.

https://p.dw.com/p/3qXCm

Advertising

Messel • The age of this petrified fly can be determined more or less accurately. About 47.5 million years ago, this prehistoric insect, immediately after a plentiful and last dinner in her life, so to speak, fell into a crater lake, died and turned into a fossil.

The Messel Quarry on the site of this lake is located in the German state of Hesse and is included in the UNESCO World Heritage List as a site of discovery of numerous rare fossils. Photos of some of the earlier finds are collected in our gallery at the bottom of the page. You can read more about this place here Ancestor of a cat with a big tail and other fossils of the Messel quarry, so let's go straight to the fly that served the cause of science.

Pollen in the stomach of a petrified fly

Points where samples were taken are marked on the left. Shown in red on the right is the full abdomen of insect Photo: Senckenberg-Gesellschaft für Naturforschung/dpa/picture alliance Current Biology published a report in March by an international team of scientists from the US, Austria and Germany who studied the fossil. Sonja Wedmann, an employee of the Senckenberg Museum (Naturmuseum Senckenberg) in Frankfurt am Main, took part in the project. Here, in one of the largest European museums of natural history, many exhibits from the nearby quarry are stored.

Sonja Wedmann, an employee of the Senckenberg Museum (Naturmuseum Senckenberg) in Frankfurt am Main, took part in the project. Here, in one of the largest European museums of natural history, many exhibits from the nearby quarry are stored.

Flies and plant pollination

By studying the contents of the stomach of this fly from the Nemestrinidae family, scientists found pollen from various plants, which was the first evidence that Diptera insects from this family participated in the pollination of plants about fifty million years ago, like bees, bumblebees and butterflies.

The Messel Quarry is located near Darmstadt - about 30 kilometers from Frankfurt am Main Photo: Arne Dedert/dpa/picture alliance According to Sonia Wedman, paleontological researchers do not rule out that for tropical plants, flies could have played an even more important role in this process than bees at that time. We also note that in recent years, due to the reduction in the number of bees in the world, scientists are increasingly paying attention to the participation of flies and other insects in pollination and are conducting appropriate research.