Story writing games for adults

5 Fun Writing Games to Play While You’re Waiting for Inspiration to Strike — Chippewa Valley Writers Guild

Kensie Kiesow

Have you ever been in a mood to write, but you’re not sure what to write about? Maybe you’re stuck on an idea that’s going nowhere, or a plot that’s going somewhere, but you don’t like where it’s ended up. Or, maybe you’re bored and this whole writing thing is something different to pass the time. In any case, games are a great way to relieve any stress or anxiety that might be preventing you from working on the next Great American Novel (cue waving flag and fireworks). Creative people often get stuck in their heads about their projects and it’s difficult to escape that spiral, especially when a deadline is fast approaching. However, it’s important to take a step back from your work every now and then to give your brain something else to chew on for a while, so let’s play some games!

“Complete the Story”

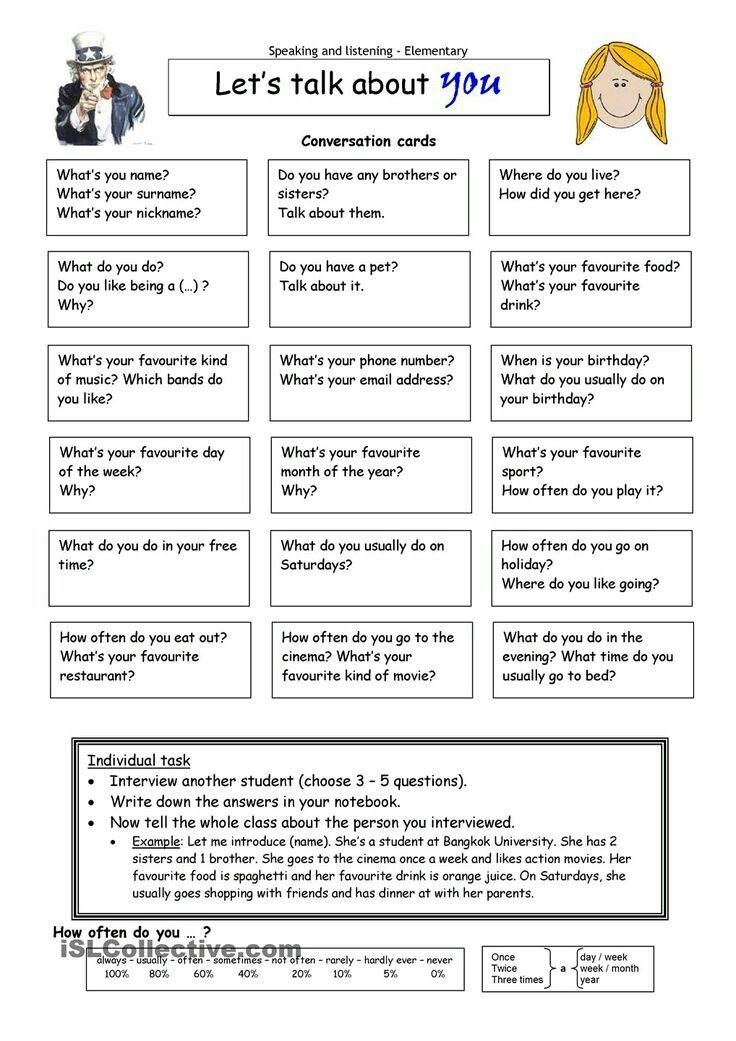

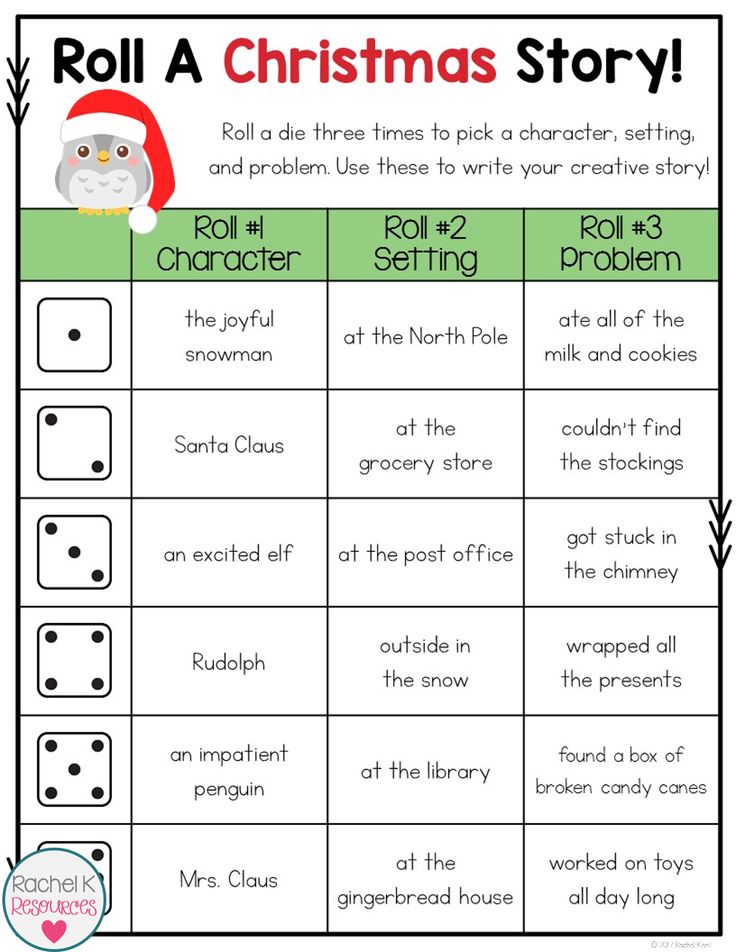

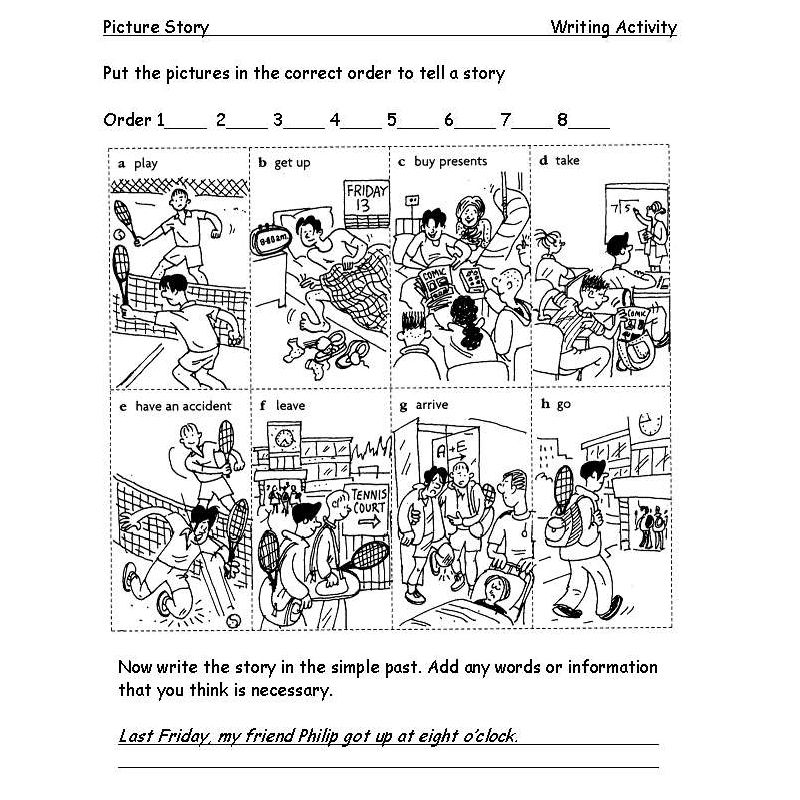

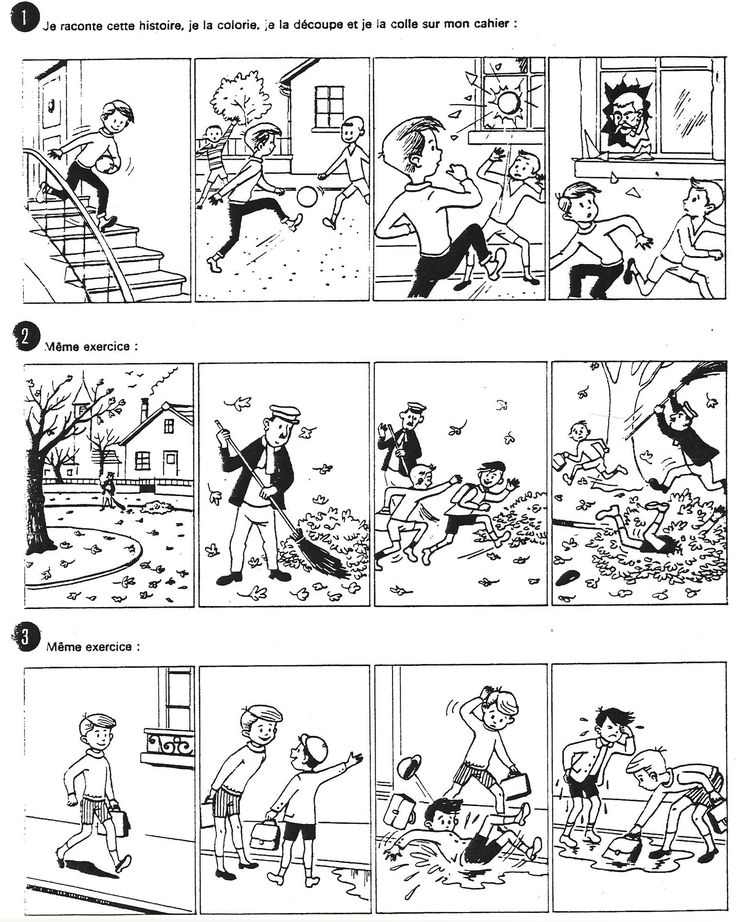

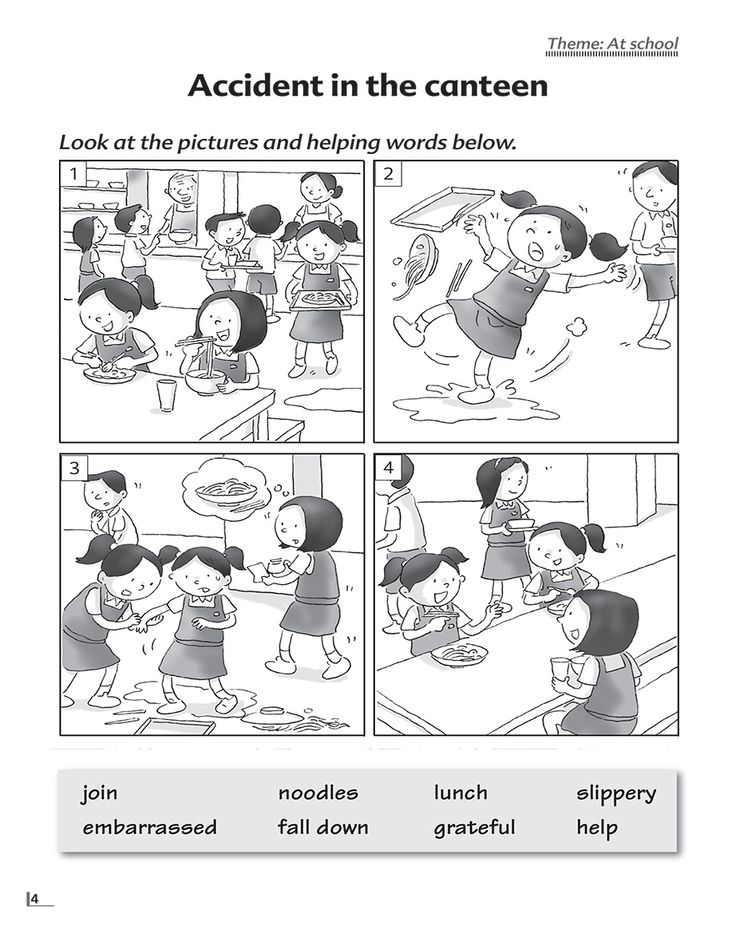

This here game is the only one on this list that requires a group of writers (at least two, but the more the zanier!) and it can easily be adapted to a socially distant e-mail chain. Firstly, you will need a prompt. The more vague or ambiguous the prompt the better because then it opens each story up to multiple, vastly different interpretations, and we at the guild have found that prompts in the form of a picture or painting work wonders for this. Next, now that you’ve got a group of creative writers and an intriguing prompt, it’s time to start writing your stories. After each player has had a moment to divine a story from the selected prompt, they have three minutes of speed writing before passing the document onto the person next to them in a clockwise motion. If you wish to adapt this to a socially distanced, e-mail format, your group will have to devise a hypothetical circle around which to pass the documents. The number of rounds wherein your group passes the document is absolutely up to you and your group, but eventually, each story should be written to conclusion. Once the stories are completed and returned to their original writers, read them back to the group and try not to laugh!

For this game, pick two books from your bookshelf completely at random. With your eyes closed, flip through the pages of the first book until some intuition from deep in your gut tells you to stop, then with that same gut intuition and your eyes closed, pick a line at random. This line will be what starts your story. Now, turn to the second book you pulled and choose another line using the same search process. As I’m sure you can guess, this second line will be the last line of your story. Write the starting line at the top of a piece of paper and the ending line on the bottom and try to connect these two, completely random thoughts!

With your eyes closed, flip through the pages of the first book until some intuition from deep in your gut tells you to stop, then with that same gut intuition and your eyes closed, pick a line at random. This line will be what starts your story. Now, turn to the second book you pulled and choose another line using the same search process. As I’m sure you can guess, this second line will be the last line of your story. Write the starting line at the top of a piece of paper and the ending line on the bottom and try to connect these two, completely random thoughts!

Some poem formulas present unique creative challenges, like the sonnet or villanelle, which require a specific structure when written traditionally. Contemporary poetry writing has all but thrown propriety out the window, but sometimes returning to your grandparent’s age of poetry can be fun game to pass that unproductive time staring at a blank page. The pantoum form consists of four-line stanzas wherein the second and fourth lines of the first stanza become the first and third lines of the next stanza, and so on and so forth. Your poem can be however long you want, but in the last stanza, the pattern switches up. Instead, the third and first lines of the first stanza become the second and fourth lines of the last, so your poem should end with the beginning line. Sound complicated enough? If your answer is no and you’d like to take this poem a step further, steal four lines from your favorite song or poem and build the rest of your pantoum from there!

Your poem can be however long you want, but in the last stanza, the pattern switches up. Instead, the third and first lines of the first stanza become the second and fourth lines of the last, so your poem should end with the beginning line. Sound complicated enough? If your answer is no and you’d like to take this poem a step further, steal four lines from your favorite song or poem and build the rest of your pantoum from there!

With one sheet of paper, write a story or poem wherein the first sentence or first line contains twenty-six words. No more, no less. As you write, knock off one more word from each sentence or line until you end up with just one word. If you’re writing a poem, you can use enjambment to cheat a little bit, but if you want to up the ante, try to make each line a complete sentence. Conversely, you could write a story that begins with a one-word sentence and grows to twenty-six!

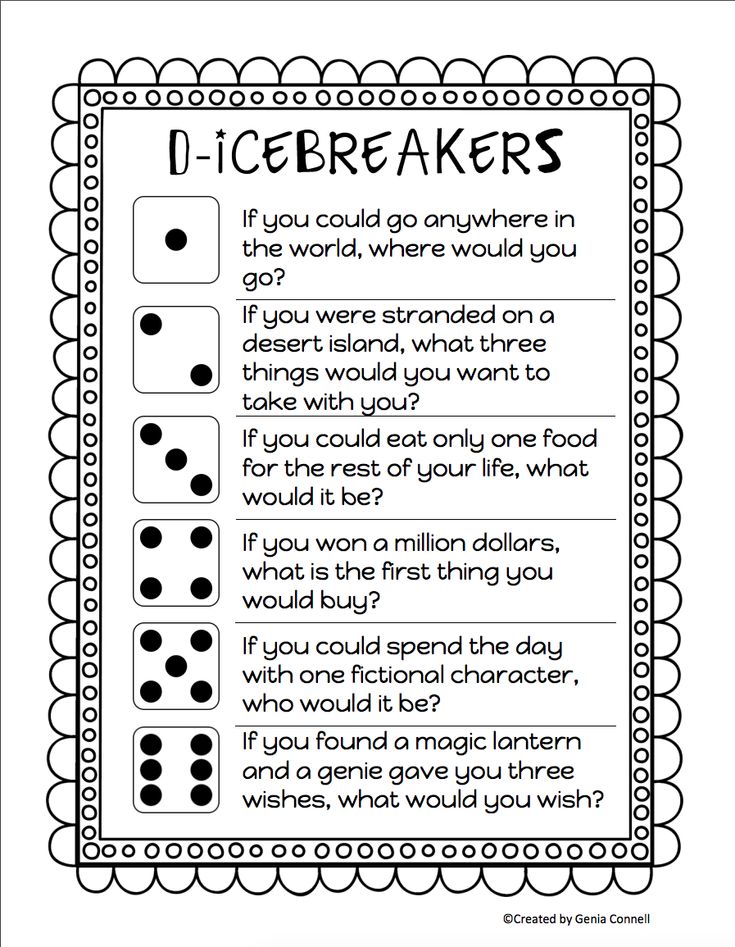

“Dialogue”Dialogue is notoriously difficult to write. There hasn’t been one writer in the history of the world who hasn’t, at some point, struggled with dialogue. It always sounds too unnatural or trite to their ears, so this game can provide you with a little no-stakes practice. Firstly, you’ll need three hats. Or, you could use envelopes, boxes, your friends’ purses, bowls, what have you, but you need three containers. Cut up a bunch of little slips of paper and write out as many places as you can think of in ten seconds and put them in the first hat. These could be rooms in your own house, a Macy’s, a national park, or the surface of the sun. Into the second hat, dump an equal number of slips on which you’ve written your characters: a mother and her son, three teen gal pals, a chicken and a goose, or a priest, rabbi, and monk. In the third and final hat, list some interesting topics like hiking in the Andes, dentistry, baking, Frankenstein, etc. Your topics can be anything you want, but make sure you can get a story out of it.

There hasn’t been one writer in the history of the world who hasn’t, at some point, struggled with dialogue. It always sounds too unnatural or trite to their ears, so this game can provide you with a little no-stakes practice. Firstly, you’ll need three hats. Or, you could use envelopes, boxes, your friends’ purses, bowls, what have you, but you need three containers. Cut up a bunch of little slips of paper and write out as many places as you can think of in ten seconds and put them in the first hat. These could be rooms in your own house, a Macy’s, a national park, or the surface of the sun. Into the second hat, dump an equal number of slips on which you’ve written your characters: a mother and her son, three teen gal pals, a chicken and a goose, or a priest, rabbi, and monk. In the third and final hat, list some interesting topics like hiking in the Andes, dentistry, baking, Frankenstein, etc. Your topics can be anything you want, but make sure you can get a story out of it. Choose one slip of paper from each hat and write a scene about what happens using ONLY dialogue! Your dialogue must include a mention of the place in which the characters are talking as well as some action, body language, and most importantly, a narrative. Writing dialogue can be stressful, but practice makes perfect and games make practicing fun!

Choose one slip of paper from each hat and write a scene about what happens using ONLY dialogue! Your dialogue must include a mention of the place in which the characters are talking as well as some action, body language, and most importantly, a narrative. Writing dialogue can be stressful, but practice makes perfect and games make practicing fun!

Now, go write!

Games to Play While Waiting for an Idea

Games to Play While Waiting for an Idea Playing at writing is an important thing to do. You probably came to write because you liked to do it. Okay, yes – you want to be rich and famous and have interesting friends. But you like writing a lot. A hockey player who works his way up through the ranks of junior hockey hopes to play in the NHL one day, but apart from skill and strength and grim determination, he has to love the game. 1. A Poem of Your Name 2. The Creature in You 3. Your Name as an Acronymic Sentence

4. The List Poem 5. A Poem in Your Phone Number 6. Metaphors and Similes. 7. Twenty-six to one 8. The Lipogram 9. 10. Pangrams 11. Verbal Remedies 12. The Pantoum The whole idea of it makes me feel Like I’m coming down with something The world chained to my ankle, a mafia death warrant, I am no poet. The subtlety of Collins’s poem is lost in my pantoum, but by the third stanza above, all the words are mine, for better or worse. It’s as if the opening stanza (the found words) is a launching pad. The second verse is half his, half mine, and then…I’m on my own. 13. Tops & Tails Thank you Richard Scrimger. Thank you Sarah Ellis. Hmmm. How do I write a page of text connecting these two thoughts? 14. Point of View 15. Dialogue 16. Words of One Syllable 17. Chronology 18. Breaking the Glass 19. Landscape is Never Simply Landscape 20. Conditions A bottle with a message in it washes up on a desert island only to be trapped in the bleached ribcage of a dead man. A tattered flag is attached to the skeleton’s wrist. In a garden on the Dorset coast, a small girl pricks her finger on a bramble bush. Ink drips from the cut – ink the same colour as the flag. It begins to spell a name on her snow-white skirt. Part of what this exercise helps to do is get you into the habit of exploring a scene like a camera, from a distance, or mid range, and then zoooooming in for that extreme close-up. It has been said that detail is the life-blood of good fiction. This is an exercise to get you thinking into an image, like a detective closing in on a clue.

|

Fairy tale box. Storytelling game

WHAT IS A BOX OF FAIRIES?

Arguably the best imaginative and storytelling board game in the galaxy.

The meaning of the game is to tell a story. And it's not so easy, because your character will travel through a bizarre world, get into strange places and unforeseen situations, and get out of them with the help of random items. Where you will go, what you will have at hand, who you will meet on the way - the cube, the "roulette of fate" and chance will decide, almost like in life. Your task is to weave a wonderful web of history out of all this and not get confused in it yourself. And you will need fantasy and mastery of the word.

You can play both together and in a large company, and of course, you can and should - with children. The party can last from half an hour to the whole evening. The age of the players is from 5 to 99. The rules are simple and flexible, the scope for creativity is almost endless.

The mechanics of The Box of Fairy Tales are designed to create a situation for the development of natural creativity without limiting the freedom of expression. It is inherent in competitiveness - but without a subjective assessment of the "quality" of fairy tales; focus on a friendly atmosphere and support during the game - but also the opportunity to "put a pig" on a partner; an element of chance - but thoughtfulness and balance.

It is inherent in competitiveness - but without a subjective assessment of the "quality" of fairy tales; focus on a friendly atmosphere and support during the game - but also the opportunity to "put a pig" on a partner; an element of chance - but thoughtfulness and balance.

I want to buy!

What does a game consist of?

Game board cards

20 very different locations. From them, a map of your history is compiled - from all (if you are not in a hurry) or from only a few. The characters will travel along it. The colorful illustrations are created according to the Wimmelbuch principle, with many details. They set a fabulous atmosphere and become starting points to the worlds of your imagination.

Characters

26 figures on stands - the characters of your future stories. What will you become today - a princess or a witch? Knight or Rogue? Or maybe a dwarf or a fairy? Or an alien monster?

You can choose your favorite heroes, give them names and give them any character properties (but remember that these properties will have to affect the game and the behavior of your character).

Items

80 tokens with items. The player who manages to use the items he got in his fairy tale receives additional points.

Stuff

Destiny Roulette - indicates what will happen to the character on the playing field during his turn.

Cube - determines where you will go (forward, backward or stay in place).

Hourglass - counts the time of the move, helping you to focus on the most important and not be distracted by trifles.

-

Number of players

from 2 to 10

-

Party

from 30 minutes to the whole evening

-

Age0003

Storytelling is an ancient, wonderful art, accessible to everyone, but almost forgotten today. This is a way of creative understanding and transformation of the world, inherent in man from time immemorial. We would very much like to see it revived and developed.

| I want to! |

| More details |

This game helped me come up with the best of my true stories.

I swear by my cocked hat!

Carl Friedrich Jerome

von Munchausen

Baron

If I had this game, I would tell fairy tales for at least 5000 nights in a row!

Scheherazade

princess

If you use this game to compose fairy tales, you will definitely not be able to fall asleep!

Ole Lukoye

storyteller

Who is our game for?

-

For inveterate dreamers and inventors — it will become the favorite leisure activity

-

For mothers — will help tell kids bedtime stories

-

For children from 5 years old — will develop creativity in the child, out-of-the-box thinking, and of course, speech

-

For creative people — will inspire new ideas

-

For everyone who would like to learn how to invent and tell - it will help to "wake up" their imagination and learn to build a story

-

For connoisseurs of board games - will become a "chip" of the collection

What develops and what will it be useful for?

-

Develops creativity, imagination, the ability to think creatively and outside the box

-

Develops oral speech, the ability to build a coherent narrative

-

Can serve as an excellent tool for language development in bilingual children, as well as for learning a foreign language 903

-

Helps the child to live through emotions and fears in a playful way, work through stressful situations.

It will become an indispensable tool in psychological work with children, fairy tale therapy and art therapy

It will become an indispensable tool in psychological work with children, fairy tale therapy and art therapy

UNFORTUNATELY, THE CIRCULATION OF THE GAME IS ENDED AND IT IS NOT AVAILABLE NOW :(

We don't know yet when there will be a new circulation, and whether there will be at all.

If you want to sign up for the waiting list, leave your details in the form below — we will definitely notify you when the game is available for sale.0003

You can find out all the details about it and order it on the website of our publishing house papermagic.ru

| Buy! |

Click to order

Word games • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

Children's room ArzamasMaterialsMaterials

Arzamas for classes with schoolchildren! A selection of materials for teachers and parents

Everything you can do in an online lesson or just for fun

Cartoons are winners of festivals. Part 2

Part 2

Fairy tales, parables, experiments and absurdity

Guide to Yasnaya Polyana

Leo Tolstoy's favorite bench, greenhouse, stable and other places of the museum-estate of the writer that are worth seeing with children

Children's poems oberiutov 9003 , Zabolotsky and Vladimirov about cats, tigers, fishermen and boys named Petya

Migrants: how to fight for their rights with the help of music

Hip-hop, carnival, talking drums and other non-obvious ways

Old records: fairy tales of the peoples of the world

Listening and analyzing Japanese, Italian, Scandinavian and Russian fairy tales 9002 Video 9003 : ISS commander asks a scientist about space

Lecture at an altitude of 400 kilometers

How to make a movie

Horror, comedy and melodrama at home

The most unusual animation techniques

VR, sunbeams, jelly and spice cartoons

Play the world's percussion instruments

Learn how the gong, marimba and drum work and build your own orchestra

How to put on a show

Shadow theater and other options for reading performances for children

Soviet puzzles

Solve children's puzzles of the 1920s-70s

22 cartoons for the smallest

What to watch if you are not six

From "The Wild Dog Dingo" to "Timur and his team"

What you need to know about the main Soviet books for children and teenagers

A guide to children's poetry of the 20th century

From Agnia Barto to Mikhail Yasnov: children's poems in Russian 9003

10 books by artists

The pages of tracing paper are Milanese fog, and the binding is the border between reality and fantasy

How to choose a modern children's book

“Like Pippi, only about love”: explaining new books through old ones

Word games

"Hat", "telegrams", "MPS" and other old and new games

Games from classic books

What the heroes of the works of Nabokov, Lindgren and Milne play

Plasticine animation: Russian school

3 From "Plasticine Crow" to plasticine "Sausage"

Cartoons - winners of festivals

"Brave Mom", "My Strange Grandfather", "Very Lonely Rooster" and others

Non-fiction for children

How the heart of a whale beats, what is inside the rocket and who plays the didgeridoo - 60 books about the world around

Guide to foreign popular music

200 artists, 20 genres and 1000 songs to help you understand the music of the 1950s-2000s

Cartoons based on poems

Poems by Chukovsky, Kharms, Gippius and Yasnov in Russian animation

Home games

Shadow theater, crafts and paper dolls from children's books and magazines of the 19th–20th centuries

Books for the little ones

Modern literature from 0 to 5: read, look at, study

Puppet animation: Russian school

Amorous Crow, Imp No. 13, Lyolya and Minka and other old and new cartoons

13, Lyolya and Minka and other old and new cartoons

Smart coloring books

Museums and libraries offer to paint their collections

Reprints and reprints of children's books

Favorite fairy tales, stories and magazines of the last century, which can be bought again

What can be heard in classical music

Steps on ice, the voice of a cuckoo and the sounds of a night forest in great compositions of the 18th–20th centuries

Soviet educational cartoons

Archimedes, dinosaurs, Antarctica and space - popular science cartoons in the USSR

Logic problems

Settle the wise men's dispute, make a bird out of a shirt and count the kittens correctly

Modern children's stories

The best short stories about grandmothers, cats, spies and knights

How Russian lullabies work

We explain why a spinning top is scary and why you shouldn't lie down on the edge. Bonus: 5 lullabies “Naada”

Musical fairy tales

As Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Prokofiev work with plots of children's fairy tales

Armenian animation school

The most rebel cartoons of the Soviet Union

Dina Goder

Software Director Great cartoon festival advises what to watch with a child

Cartoons about art

How to tell children about Picasso, Pollock and Tatlin using animation

40 riddles about everything in the world

What burns without fire and who has a sieve in his nose: riddles from "Chizh", "Hedgehog" books by Marshak and Chukovsky

Yard games

Traffic light, Shtander, Ring and other games for a large company

Poems that are interesting to learn by heart

autumn

Old audio plays for children

Ole Lukoye, The Gray Sheika, Cinderella and other interesting Soviet recordings

Classical music cartoons

How animation works with the music of Tchaikovsky, Verdi and Glass

How children work counting rhymes

“Ene, bene, slave, kvanter, manter, toad”: what does it all mean

“Hat”, “telegrams”, “MPS” and other games that require almost nothing but company and a desire to spend time properly

Author Lev Gankin

Primer “A. B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons

B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons Oral games

Associations

Game for a big company. The host briefly leaves the room, during which time the rest decide which of those present they will guess (this may be the host himself). Upon returning, the player asks the others questions - what flower do you associate this person with, what vehicle, what part of the body, what kitchen utensils, etc. - in order to understand who is hidden. Questions can be very different - this is not limited by anything other than the imagination of the players. Since associations are an individual matter and an exact match may not happen here, it is customary to give the guesser two or three attempts. If the company is small, you can expand the circle of mutual acquaintances who are not present at that moment in the room, although the classic version of "associations" is still a hermetic game.

Game of P

A game for a company of four people, an interesting variation on the "hat" theme (see below), but does not require any special accessories. One player guesses a word to another, which he must explain to the others, but he can only use words starting with the letter "p" (any, except for the same root). That is, the word "house" will have to be explained, for example, as follows: "I built - I live." If you couldn’t guess right away, you can throw up additional associations: “building, premises, space, the simplest concept ...” And at the end add, for example, “Perignon” - by association with Dom Perignon champagne. If the guessers are close to winning, then the facilitator will need comments like “about”, “approximately”, “almost right” - or, in the opposite situation: “bad, wait!”. Usually, after the word is guessed, the explainer comes up with a new word and whispers it into the ear of the guesser - he becomes the next leader.

One player guesses a word to another, which he must explain to the others, but he can only use words starting with the letter "p" (any, except for the same root). That is, the word "house" will have to be explained, for example, as follows: "I built - I live." If you couldn’t guess right away, you can throw up additional associations: “building, premises, space, the simplest concept ...” And at the end add, for example, “Perignon” - by association with Dom Perignon champagne. If the guessers are close to winning, then the facilitator will need comments like “about”, “approximately”, “almost right” - or, in the opposite situation: “bad, wait!”. Usually, after the word is guessed, the explainer comes up with a new word and whispers it into the ear of the guesser - he becomes the next leader.

Lectures for children on this topic:

Course of lectures for children about the languages of the world

How many languages in the world, how do they differ and how are they similar to each other

Course of lectures for children about strange and new words of the Russian language

Why linguists study jargon, parasitic words and speech errors

Primer "A. B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons

B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons Say the Same Thing

An upbeat and fast-paced game for two, named after a video clip by the inventive rock band OK Go, from which many people learned about it (the musicians even developed a mobile application that helps to play it from a distance, although it is currently unavailable). The meaning of the game is that on the count of one-two-three each of the players pronounces a randomly chosen word. Further, the goal of the players is, with the help of successive associations, to come to a common denominator: for the next time, two or three, both pronounce a word that is somehow connected with the previous two, and so on until the desired coincidence occurs. Suppose the first player said the word "house" and the second player said the word "sausage"; in theory, they can coincide very soon, if on the second move after one-two-three both say "store". But if one says “shop”, and the other says “refrigerator” (why not a sausage house?), then the game can drag on, especially since it’s impossible to repeat - neither the store nor the refrigerator will fit, and you will have to think, say, before "refrigerator" or "IKEI". If the original words are far from each other (for example, "curb" and "weightlessness"), then the gameplay becomes completely unpredictable.

If the original words are far from each other (for example, "curb" and "weightlessness"), then the gameplay becomes completely unpredictable.

Characters

A game for the company (the ideal number of players is from four to ten), which requires from the participants not only a good imagination, but also, preferably, a little bit of acting skills. As usual, one of the players briefly leaves the room, and while he is gone, the rest come up with a word, the number of letters in which matches the number of participants remaining in the room. Next, the letters are distributed among the players, and a character is invented for each of them (therefore, words that contain "b", "s" or "b" do not fit). Until the word is guessed, the players behave in accordance with the chosen character - the leader's task is to understand exactly what characters his partners portray and restore the hidden word. Imagine, for example, that a company consists of seven people. One leaves, the rest come up with a six-letter word "old man" and distribute roles among themselves: the first, say, will be with indoor, the second - t erpel, the third - a secondary, the fourth - p asylum, the fifth - and mane and sixth - to ovary. The returning player is greeted by a cacophony of voices - the company "lives" their roles until they are unraveled, and the host asks the players questions that help reveal their image. The only condition is that as soon as the presenter pronounces the correct character - for example, guesses the insidious one - he must admit that his incognito has been revealed and announce the number of his letter (in the word "old man" - the sixth).

The returning player is greeted by a cacophony of voices - the company "lives" their roles until they are unraveled, and the host asks the players questions that help reveal their image. The only condition is that as soon as the presenter pronounces the correct character - for example, guesses the insidious one - he must admit that his incognito has been revealed and announce the number of his letter (in the word "old man" - the sixth).

Recognize the song

A game for a company of four to five people. The host leaves, and the remaining players choose a well-known song and distribute its words among themselves - each word. For example, the song “Let there always be sun” is guessed: one player gets the word “let”, the second - “always”, the third - “will be”, the fourth - “sun”. The host returns and begins to ask questions - the most varied and unexpected: "What is your favorite city?", "Where does the Volga flow?", "What to do and who is to blame?". The task of the respondents is to use their own word in the answer and try to do it in such a way that it does not stand out too much; you need to answer quickly and not very extensively, but not necessarily truthfully. Answers to questions in this case can be, for example, “It’s hard for me to choose one city, but let today it will be Rio de Janeiro" or "Volga - into the Caspian, but this does not happen always , every third year it flows into the Black". The presenter must catch which word is superfluous in the answer and guess the song. They often play with lines from poetry rather than from songs.

The task of the respondents is to use their own word in the answer and try to do it in such a way that it does not stand out too much; you need to answer quickly and not very extensively, but not necessarily truthfully. Answers to questions in this case can be, for example, “It’s hard for me to choose one city, but let today it will be Rio de Janeiro" or "Volga - into the Caspian, but this does not happen always , every third year it flows into the Black". The presenter must catch which word is superfluous in the answer and guess the song. They often play with lines from poetry rather than from songs.

Tip

A game for four people divided into pairs (in principle, there can be three or four pairs). The mechanics is extremely simple: the first player from the first pair whispers a word (a common noun in the singular) into the ear of the first player from the second pair, then they must take turns calling their associations with this word (in the same form - common nouns; cognate words cannot be used ). After each association, the teammate of the player who voiced it calls out his word, trying to guess if it was originally guessed - and so on, until the problem is solved by someone; at the same time, all associations already sounded in the game can be used in the future, adding one new one at each move. For example, suppose there are players A and B on one team, and C and D on the other. Player A whispers the word "old man" into player C's ear. Player C says aloud to his partner D: "age". If D immediately answers "old man", then the pair of C and D scores a point, but if he says, for example, "youth", then the move goes to player A, who, using the word "age" suggested by C (but discarding the irrelevant to the case "youth" from D), says to his partner B: "age, man." Now B will probably guess the old man - and his team with A will already earn a point. But if he says "teenager" (thinking that it is about the age when boys turn into men), then C, to whom the move suddenly returned, will say " age, man, eightieth birthday”, and here, probably, “old man” will be guessed.

After each association, the teammate of the player who voiced it calls out his word, trying to guess if it was originally guessed - and so on, until the problem is solved by someone; at the same time, all associations already sounded in the game can be used in the future, adding one new one at each move. For example, suppose there are players A and B on one team, and C and D on the other. Player A whispers the word "old man" into player C's ear. Player C says aloud to his partner D: "age". If D immediately answers "old man", then the pair of C and D scores a point, but if he says, for example, "youth", then the move goes to player A, who, using the word "age" suggested by C (but discarding the irrelevant to the case "youth" from D), says to his partner B: "age, man." Now B will probably guess the old man - and his team with A will already earn a point. But if he says "teenager" (thinking that it is about the age when boys turn into men), then C, to whom the move suddenly returned, will say " age, man, eightieth birthday”, and here, probably, “old man” will be guessed. In one of the variants of the game, it is also allowed to "shout": this means that, having suddenly guessed what was meant, the player can shout out the option not on his turn. If he guessed right, his team will get a point, but if he rushed to conclusions, the team will lose a point. They usually play up to five points.

In one of the variants of the game, it is also allowed to "shout": this means that, having suddenly guessed what was meant, the player can shout out the option not on his turn. If he guessed right, his team will get a point, but if he rushed to conclusions, the team will lose a point. They usually play up to five points.

IPU

Game for a big company. Here we are forced to warn readers that, having seen this text in full, you will never be able to drive again - the game is one-time.

Spoiler →

First, the player who gets to drive leaves the room. When he returns, he must find out what MPS means - all that is known in advance is that the bearer of this mysterious abbreviation is present in the room right now. To find out the correct answer, the driver can ask other players questions, the answers to which should be formulated as “yes” or “no”: “Does he have blond hair?”, “Does he have blue eyes?”, “Is this a man?”, “He in jeans?", "Does he have a beard?"; moreover, each question is asked to a specific player, and not to all at once. Most likely, it will quickly become clear that there is simply no person in the room who meets all the criteria; Accordingly, the question arises, according to what principle the players give answers. "Opening" this principle will help answer the main question - what is MPS. The Ministry of Railways is not the Ministry of Communications at all, but m oy p equal s seated (that is, each player always describes the person sitting to his right). Another option is COP, to then to answered to last (that is, everyone talks about who answered the previous question).

Most likely, it will quickly become clear that there is simply no person in the room who meets all the criteria; Accordingly, the question arises, according to what principle the players give answers. "Opening" this principle will help answer the main question - what is MPS. The Ministry of Railways is not the Ministry of Communications at all, but m oy p equal s seated (that is, each player always describes the person sitting to his right). Another option is COP, to then to answered to last (that is, everyone talks about who answered the previous question).

Contact

A simple game that can be played with a group of three or more people. One thinks of a word (noun, common noun, singular) and calls its first letter aloud, the task of the others is to guess the word, remembering other words with this letter, asking questions about them and checking if the presenter guessed. The facilitator's task is not to reveal the next letters in the word to the players for as long as possible. For example, a word with the letter "d" is guessed. One of the players asks the question: “Is this by chance not the place where we live?” This is where the fun begins: the host must figure out as quickly as possible what the player means and say “No, this is not“ house ”” (well, or, if it was a“ house ”, honestly admit it). But in parallel, other players also think the same thing, and if they understand what “house” means before the leader, then they say: “contact” or “there is contact”, and start counting up to ten in chorus (while the count is going on, the presenter still has a chance to escape and guess what it is about!), and then they call the word. If at least two matched, that is, at the expense of ten they said “house” in chorus, the presenter must reveal the next letter, and the new guesser version will already begin with the now known letters “d” + the next one. If it was not possible to beat the host on this question, then the guessers offer a new option.

The facilitator's task is not to reveal the next letters in the word to the players for as long as possible. For example, a word with the letter "d" is guessed. One of the players asks the question: “Is this by chance not the place where we live?” This is where the fun begins: the host must figure out as quickly as possible what the player means and say “No, this is not“ house ”” (well, or, if it was a“ house ”, honestly admit it). But in parallel, other players also think the same thing, and if they understand what “house” means before the leader, then they say: “contact” or “there is contact”, and start counting up to ten in chorus (while the count is going on, the presenter still has a chance to escape and guess what it is about!), and then they call the word. If at least two matched, that is, at the expense of ten they said “house” in chorus, the presenter must reveal the next letter, and the new guesser version will already begin with the now known letters “d” + the next one. If it was not possible to beat the host on this question, then the guessers offer a new option. Of course, it makes sense to complicate the definitions, and not ask everything directly - so the question about "home" would sound better like "Is this not where the sun rises?" (with a reference to the famous song "House of the Rising Sun" by The Animals). Usually, the one who eventually gets to the searched word (names it or asks a question leading to victory) becomes the next leader.

Of course, it makes sense to complicate the definitions, and not ask everything directly - so the question about "home" would sound better like "Is this not where the sun rises?" (with a reference to the famous song "House of the Rising Sun" by The Animals). Usually, the one who eventually gets to the searched word (names it or asks a question leading to victory) becomes the next leader.

Writing games

Encyclopedia

Not the fastest, but extremely exciting game for a company of four people - you will need pens, paper and some kind of encyclopedic dictionary (preferably not limited thematically - that is, TSB is better than a conditional "biological encyclopedia"). The host finds a word in the encyclopedia that is unknown to anyone present (here it remains to rely on their honesty - but cheating in this game is uninteresting and unproductive). The task of each of the players is to write an encyclopedic definition of this word, inventing its meaning from the head and, if possible, disguising the text as a real small encyclopedic article. The presenter, meanwhile, carefully rewrites the real definition from the encyclopedia. After that, the “articles” are shuffled and read out by the presenter in random order, including the real one, and the players vote for which option seems most convincing to them. In the end, the votes are counted and points are distributed. Any player receives a point for correctly guessing the real definition and one more point for each vote given by other participants to his own version. After that, the sheets are distributed back and a new word is played out - there should be about 6-10 of them in total. You can also play this game in teams: come up with imaginary definitions collectively. The game "poems" is arranged in a similar way - but instead of a compound word, the host selects two lines from some little-known poem in advance and invites the participants to add quatrains.

The task of each of the players is to write an encyclopedic definition of this word, inventing its meaning from the head and, if possible, disguising the text as a real small encyclopedic article. The presenter, meanwhile, carefully rewrites the real definition from the encyclopedia. After that, the “articles” are shuffled and read out by the presenter in random order, including the real one, and the players vote for which option seems most convincing to them. In the end, the votes are counted and points are distributed. Any player receives a point for correctly guessing the real definition and one more point for each vote given by other participants to his own version. After that, the sheets are distributed back and a new word is played out - there should be about 6-10 of them in total. You can also play this game in teams: come up with imaginary definitions collectively. The game "poems" is arranged in a similar way - but instead of a compound word, the host selects two lines from some little-known poem in advance and invites the participants to add quatrains.

Game from Inglourious Basterds

A game for a company of any size that many knew before the Quentin Tarantino film, but it does not have a single name. Each player invents a role for his neighbor (usually it is some famous person), writes it on a piece of paper and sticks the piece of paper on his neighbor's forehead: accordingly, everyone sees what role someone has, but does not know who they are. The task of the participants is, with the help of leading questions, the answers to which are formulated as “yes” or “no” (“Am I a historical figure?”, “Am I a cultural figure?”, “Am I a famous athlete?”), to find out who exactly they are. In this form, however, the game exhausts itself rather quickly, so you can come up with completely different themes and instead of famous people play, for example, in professions (including exotic ones - "carousel", "taxidermist"), in film and literary heroes (you can mix them with real celebrities, but it’s better to agree on this in advance), food (one player will be risotto, and the other, say, green cabbage soup) and even just items.

Bulls and cows

A game for two: one participant thinks of a word, and it is agreed in advance how many letters should be in it (usually 4-5). The task of the second is to guess this word by naming other four- or five-letter words; if some letters of the named word are in the hidden one, they are called cows, and if they have the same place inside the word, then these are bulls. Let's imagine that the word "eccentric" is conceived. If the guesser says “dot”, then he receives an answer from the second player: “three cows” (that is, the letters “h”, “k” and “a”, which are in both “eccentric” and “dot”, but in different places). If he then says "head of head", he will no longer get three cows, but two cows and one bull - since the letter "a" in both "eccentric" and "head" is in the fourth position. As a result, sooner or later, it is possible to guess the word, and the players can change places: now the first one will guess the word and count the bulls and cows, and the second one will name his options and track the extent to which they coincide with the one guessed. You can also complicate the process by simultaneously guessing your own word and guessing the opponent's word.

You can also complicate the process by simultaneously guessing your own word and guessing the opponent's word.

Intellect

Writing game for the company (but you can also play together), consisting of three rounds, each for five minutes. In the first, players randomly type thirteen letters (for example, blindly poking a book page with their finger) and then form words from them, and only long ones - from five letters. In the second round, you need to choose a syllable and remember as many words as possible that begin with it, you can use single-root ones (for example, if the syllable "house" is selected, then the words "house", "domra", "domain", "domain", "brownie", "housewife", etc.). Finally, in the third round, the syllable is taken again, but now you need to remember not ordinary words, but the names of famous people of the past and present in which it appears, and not necessarily at the beginning - that is, both Karamzin and McCartney will fit the syllable "kar" , and, for example, Hamilcar. An important detail: since this round provokes the most disputes and scams, game participants can ask each other to prove that this person is really a celebrity, and here you need to remember at least the profession and country. Typical dialogue: "What, you don't know Hamilcar? But this is a Carthaginian commander!” After each round, points are counted: if a particular word is the same for all players, it is simply crossed out, in other cases, players are awarded as many points for it as the opponents could not remember it. In the first round, you can still add points for especially long words. Based on the results of the rounds, it is necessary to determine who took the first, second, third and other places, and add up these places at the end of the game. The goal is to get the smallest number at the output (for example, if you were the winners of all three rounds, then you will get the number 3 - 1 + 1 + 1, and you are the champion; less cannot be purely mathematical).

An important detail: since this round provokes the most disputes and scams, game participants can ask each other to prove that this person is really a celebrity, and here you need to remember at least the profession and country. Typical dialogue: "What, you don't know Hamilcar? But this is a Carthaginian commander!” After each round, points are counted: if a particular word is the same for all players, it is simply crossed out, in other cases, players are awarded as many points for it as the opponents could not remember it. In the first round, you can still add points for especially long words. Based on the results of the rounds, it is necessary to determine who took the first, second, third and other places, and add up these places at the end of the game. The goal is to get the smallest number at the output (for example, if you were the winners of all three rounds, then you will get the number 3 - 1 + 1 + 1, and you are the champion; less cannot be purely mathematical).

B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons

B. C. Trim, alphabet enchanté. Illustrations by Bertal. France, 1861 Wikimedia Commons Frame

A game for any number of people, which was invented by one of the creators of the Kaissa chess program and the author of the anagram search program Alexander Bitman. First, the players choose several consonants - this will be the frame, the skeleton of the word. Then the time is recorded (two or three minutes), and the players begin to “stretch” vowels (as well as “й”, “ь”, “ъ”) onto the frame to make existing words. Consonants can be used in any order, but only once, and vowels can be added in any number. For example, players choose the letters "t", "m", "n" - then the words "fog", "cloak", "mantle", "coin", "darkness", "ataman", "dumbness" and other. The winner is the one who can come up with more words (as usual, these should be common nouns in the singular). The game can be played even with one letter, for example, "l". The words “silt”, “lay”, “yula”, “aloe”, “spruce” are formed around it, and if we agree that the letter can be doubled, “alley” and “lily”. If the standard "framework" is mastered, then the task may be to compose a whole phrase with one consonant: a textbook example from the book by Evgeny Gik - "Bobby, kill the boy and beat the woman at the baobab."

If the standard "framework" is mastered, then the task may be to compose a whole phrase with one consonant: a textbook example from the book by Evgeny Gik - "Bobby, kill the boy and beat the woman at the baobab."

Chain of words

Game for any number of players. Many people know it under the name "How to make an elephant out of a fly", and it was invented by the writer and mathematician Lewis Carroll, the author of "Alice". The “chain” is based on metagram words, that is, words that differ by only one letter. The task of the players is to turn one word into another with the least number of intermediate links. For example, let's make a "goat" from a "fox": FOX - LINDE - PAW - KAPA - KARA - KORA - GOAT. It is interesting to give tasks with a plot: so that the “day” turns into “night”, the “river” becomes the “sea”. The well-known chain, where the "elephant" grows out of the "fly", is obtained in 16 moves: FLY - MURA - TURA - TARA - KARA - KARE - CAFE - KAFR - MURDER - KAYUK - HOOK - URIK - LESSON - TERM - DRAIN - STON - ELEPHANT (example of Evgeny Gik). For training, you can compete in the search for metagrams for any word. For example, the word "tone" gives "sleep", "background", "current", "tom", "tan" and so on - whoever scores more options wins.

For training, you can compete in the search for metagrams for any word. For example, the word "tone" gives "sleep", "background", "current", "tom", "tan" and so on - whoever scores more options wins.

Hat

A game for a company of four people, requiring simple equipment: pens, paper and a “hat” (an ordinary plastic bag will do). Sheets of paper need to be torn into small pieces and distributed to the players, the number of pieces depends on how many people are playing: the larger the company, the less for each. Players write words on pieces of paper (one for each piece of paper) and throw them into the "hat". There are also options here - you can play just with words (noun, common noun, singular), or you can play with famous people or literary characters. Then the participants are divided into teams - two or more people each; the task of each - in 20 seconds (or 30, or a minute - the timing can be set at your own choice) to explain to your teammates the largest number of words arbitrarily pulled out of the "hat", without using the same root. If the driver could not explain a word, it returns to the hat and will be played by the other team. At the end of the game, the words guessed by different representatives of the same team are summed up, their number is counted, and the team that has more pieces of paper is awarded the victory. A popular version of the game: everything is the same, but in the first round the players explain the words (or describe the characters) orally, in the second round they show in pantomime, in the third round they explain the same words in one word. And recently a board game has appeared, where you need not only to explain and show, but also to draw.

If the driver could not explain a word, it returns to the hat and will be played by the other team. At the end of the game, the words guessed by different representatives of the same team are summed up, their number is counted, and the team that has more pieces of paper is awarded the victory. A popular version of the game: everything is the same, but in the first round the players explain the words (or describe the characters) orally, in the second round they show in pantomime, in the third round they explain the same words in one word. And recently a board game has appeared, where you need not only to explain and show, but also to draw.

Telegrams

Game for any number of players. The players choose a word, for each letter of which they will need to come up with a part of the telegram - the first letter will be the beginning of the first word, the second - the second, and so on. For example, the word "fork" is selected. Then the following message can become a telegram: “The camel is healed. I'm flying a crocodile. Aibolit". Another round of the game is the addition of genres. Each player gets the task to write not one, but several telegrams from the same word - business, congratulatory, romantic (the types of messages are agreed in advance). Telegrams are read aloud, the next word is chosen.

I'm flying a crocodile. Aibolit". Another round of the game is the addition of genres. Each player gets the task to write not one, but several telegrams from the same word - business, congratulatory, romantic (the types of messages are agreed in advance). Telegrams are read aloud, the next word is chosen.

even more different games for one or a company

Home games

Shadow theater, crafts and paper dolls from children's books and magazines of the XIX-XX centuries Ring and other games

Games from classic books

What do the heroes of the works of Nabokov, Lindgren and Milne play

Children's course on where games, jokes, horror stories and memes come from and why we need them

Children's room

Special project

Children's room Arzamas

Sources

It’s fun! Same goes for writing. The work of writing grows out of the enjoyment of stick-handling words, passing words, zinging words into the net. You will never be able to write twelve drafts of a novel if you didn’t enjoy the first, rough, casting-about part of the process. It is my great hope that the work involved in writing doesn’t even occur to a person until s/he is already so far along in the pleasurable task of putting words and sentences together in original and amusing and striking ways; that the work is well worth the effort to get it right. But I digress. When the ideas aren’t flowing you can prime the pump. Here are some games I have discovered along the way.

It’s fun! Same goes for writing. The work of writing grows out of the enjoyment of stick-handling words, passing words, zinging words into the net. You will never be able to write twelve drafts of a novel if you didn’t enjoy the first, rough, casting-about part of the process. It is my great hope that the work involved in writing doesn’t even occur to a person until s/he is already so far along in the pleasurable task of putting words and sentences together in original and amusing and striking ways; that the work is well worth the effort to get it right. But I digress. When the ideas aren’t flowing you can prime the pump. Here are some games I have discovered along the way. If you’ve got middle names, now is the time to be thankful for them. I knew a seventh-grade student who found Smashing Pumpkins in her name! I say poem, but I use the term loosely. You make a list of words and then use them as well as you can. The thing is, the result will always sound poetic by dint of its highly alliterative content. (See Stephen’s poem in the chapter “Me, Myself and Why” in my book, Stephen Fair.)

If you’ve got middle names, now is the time to be thankful for them. I knew a seventh-grade student who found Smashing Pumpkins in her name! I say poem, but I use the term loosely. You make a list of words and then use them as well as you can. The thing is, the result will always sound poetic by dint of its highly alliterative content. (See Stephen’s poem in the chapter “Me, Myself and Why” in my book, Stephen Fair.) Try to write a sentence, instead. Here am I acronymically: Today Is More Of Tomorrow’s Hopeful Yesterdays. String together acronymic sentences of ten of your family or friends’ names. Try to make it into a unified piece.

Try to write a sentence, instead. Here am I acronymically: Today Is More Of Tomorrow’s Hopeful Yesterdays. String together acronymic sentences of ten of your family or friends’ names. Try to make it into a unified piece. When Kathi does it, a zero counts as a wild card.

When Kathi does it, a zero counts as a wild card. You can stand this game on its head and write a story that begins with one word. This is a wonderful way to get to know what a sentence is or might be. The story will, inevitably, be totally nonsensical. My twenty-six-to-one book On Tumbledown Hill makes some sense and rhymes, too, but it took over six years to write!

You can stand this game on its head and write a story that begins with one word. This is a wonderful way to get to know what a sentence is or might be. The story will, inevitably, be totally nonsensical. My twenty-six-to-one book On Tumbledown Hill makes some sense and rhymes, too, but it took over six years to write! The Univocalic

The Univocalic Here is one that’s not so short but paints a lively picture: “Curious and wily journalists braved the fury of the six brazen knaves picketing the mad queen.”

Here is one that’s not so short but paints a lively picture: “Curious and wily journalists braved the fury of the six brazen knaves picketing the mad queen.”  The second and fourth lines of the first stanza become the first and third line of the next stanza, and so on. The poem can be of any length but in the final stanza the pattern changes. The third and first line of the original verse become the second and fourth line of the last, so that the pantoum ends exactly as it began.

The second and fourth lines of the first stanza become the first and third line of the next stanza, and so on. The poem can be of any length but in the final stanza the pattern changes. The third and first line of the original verse become the second and fourth line of the last, so that the pantoum ends exactly as it began.  Condemned; a corpse in training

Condemned; a corpse in training The idea is not to think too much, not to pause or scratch out or worry about grammar or spelling, but just to let the words pour from one’s unconscious, more or less out of control. That’s good. Your unconscious is your writing buddy and the more chance s/he gets to spew without your conscious mind editing, the better.

The idea is not to think too much, not to pause or scratch out or worry about grammar or spelling, but just to let the words pour from one’s unconscious, more or less out of control. That’s good. Your unconscious is your writing buddy and the more chance s/he gets to spew without your conscious mind editing, the better.

Or maybe the goat?

Or maybe the goat? )

)

It helped. Last time I heard he was playing first violin for the San Francisco Opera.

It helped. Last time I heard he was playing first violin for the San Francisco Opera. ” Such sentences evoke nothing, express no emotion. But how can a lake or a garden tell us of love or loss? Well, think of how bleak the world looks when you’re sad, even if the sun is shining. Now do you get it? In fact, a really good exercise would be to describe a lake as seen by a boy or girl who is in love. And then describe a lake as seen by a boy or a girl who just killed someone. The lake will not be the same.

” Such sentences evoke nothing, express no emotion. But how can a lake or a garden tell us of love or loss? Well, think of how bleak the world looks when you’re sad, even if the sun is shining. Now do you get it? In fact, a really good exercise would be to describe a lake as seen by a boy or girl who is in love. And then describe a lake as seen by a boy or a girl who just killed someone. The lake will not be the same. It’s something Edward Gorey did a lot of. Also, one thinks of Chris Van Allsburg’s The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. Or the way Stephen King starts his novels by introducing you to a character in a bizarre situation then jumping to several other characters, also in compromising or difficult situations. You know they are a “special” group; you know they are going to come together. But whether the conditions in this exercise lead anywhere or not, leaps are a good thing to know about – to practice. Sometimes I will worry away at a piece of writing for pages and pages trying to get my protagonist from point A to point B in a “meaningful way,” and then end up just putting him there. Think of the way scenes in movies are spliced together. Here’s an example of a string of conditions I wrote when I was much younger.

It’s something Edward Gorey did a lot of. Also, one thinks of Chris Van Allsburg’s The Mysteries of Harris Burdick. Or the way Stephen King starts his novels by introducing you to a character in a bizarre situation then jumping to several other characters, also in compromising or difficult situations. You know they are a “special” group; you know they are going to come together. But whether the conditions in this exercise lead anywhere or not, leaps are a good thing to know about – to practice. Sometimes I will worry away at a piece of writing for pages and pages trying to get my protagonist from point A to point B in a “meaningful way,” and then end up just putting him there. Think of the way scenes in movies are spliced together. Here’s an example of a string of conditions I wrote when I was much younger.