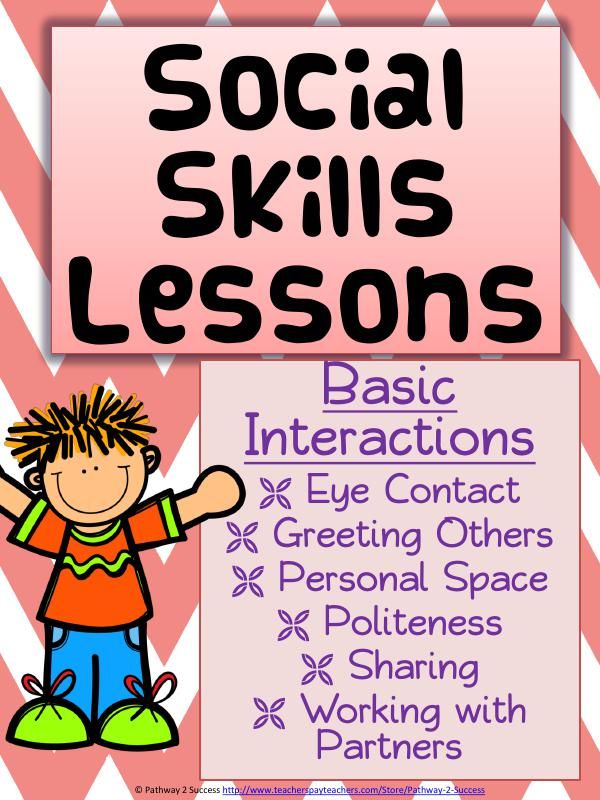

Teach social skills

9 Ways to Teach Social Skills in Your Classroom

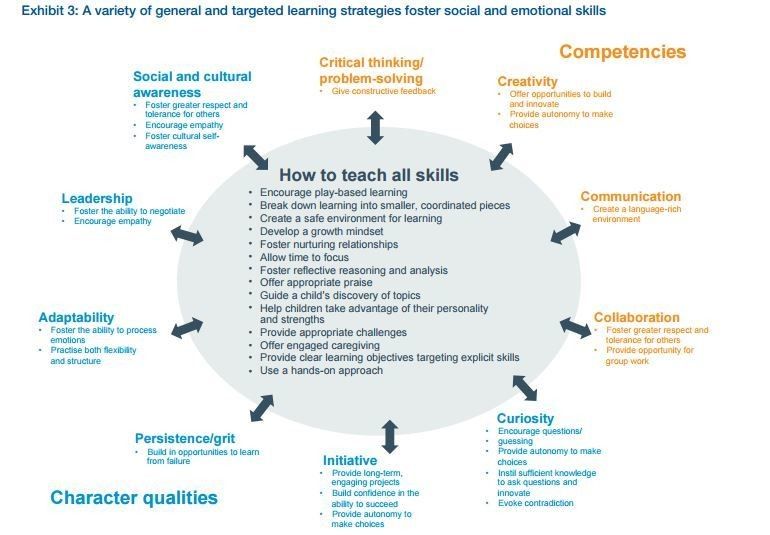

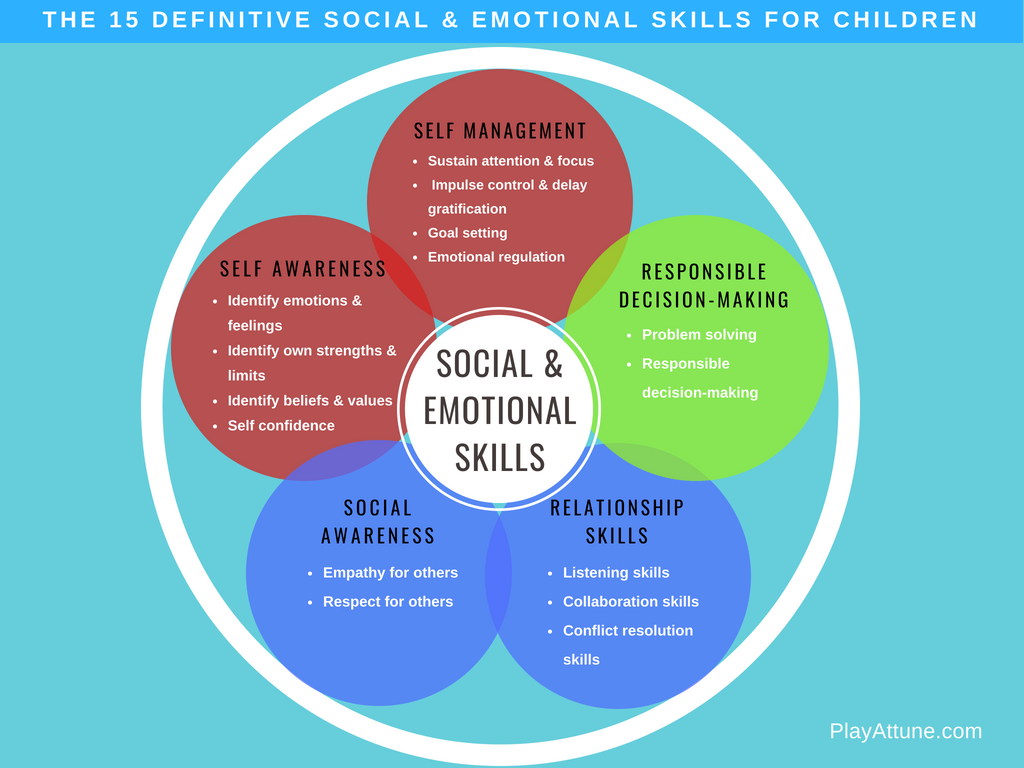

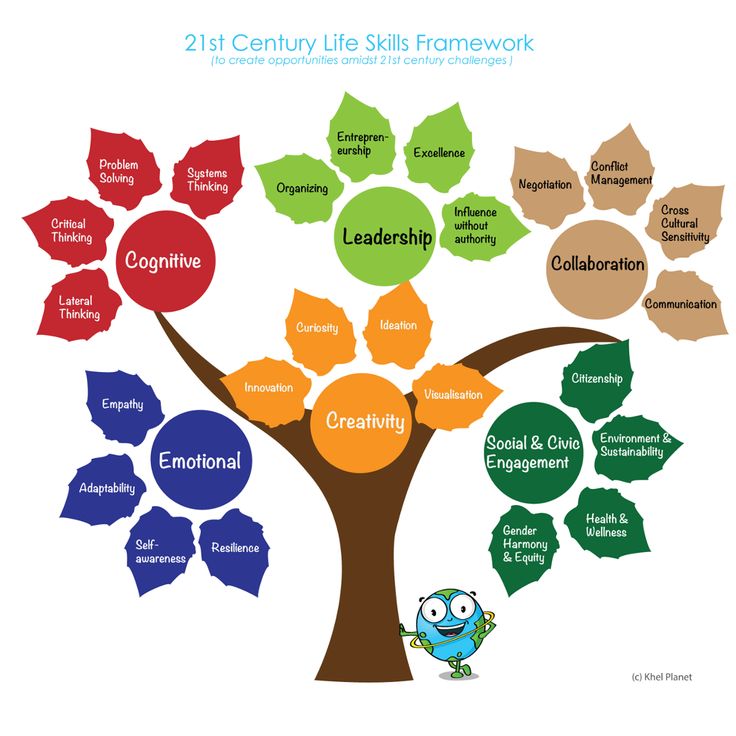

Research and experience has told us that having social skills is essential for success in life. Inclusive teachers have always taught, provided and reinforced the use of good social skills in order to include and accommodate for the wide range of students in the classroom.

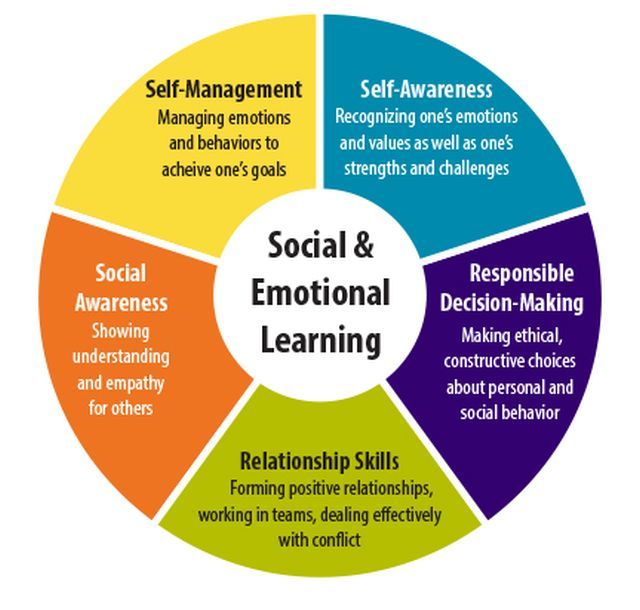

Essentially, inclusive classrooms are representations of the real world where people of all backgrounds and abilities co-exsist. In fact, there are school disctricts with curriculum specifically for social and emotional development.

Here are some ways in which you can create a more inclusive classroom and support social skill development in your students:

1. Model manners

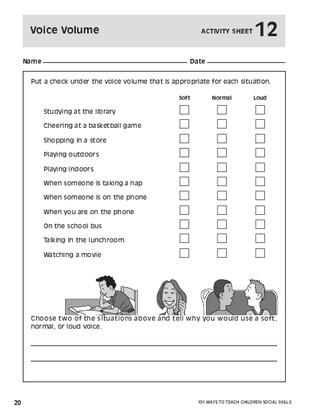

If you expect your students to learn and display good social skills, then you need to lead by example. A teacher's welcoming and positive attitude sets the tone of behaivor between the students. They learn how to intereact with one another and value individuals. For example, teachers who expect students to use "inside voices" shouldn't be yelling at the class to get their attention.

In other words, practice what you preach.

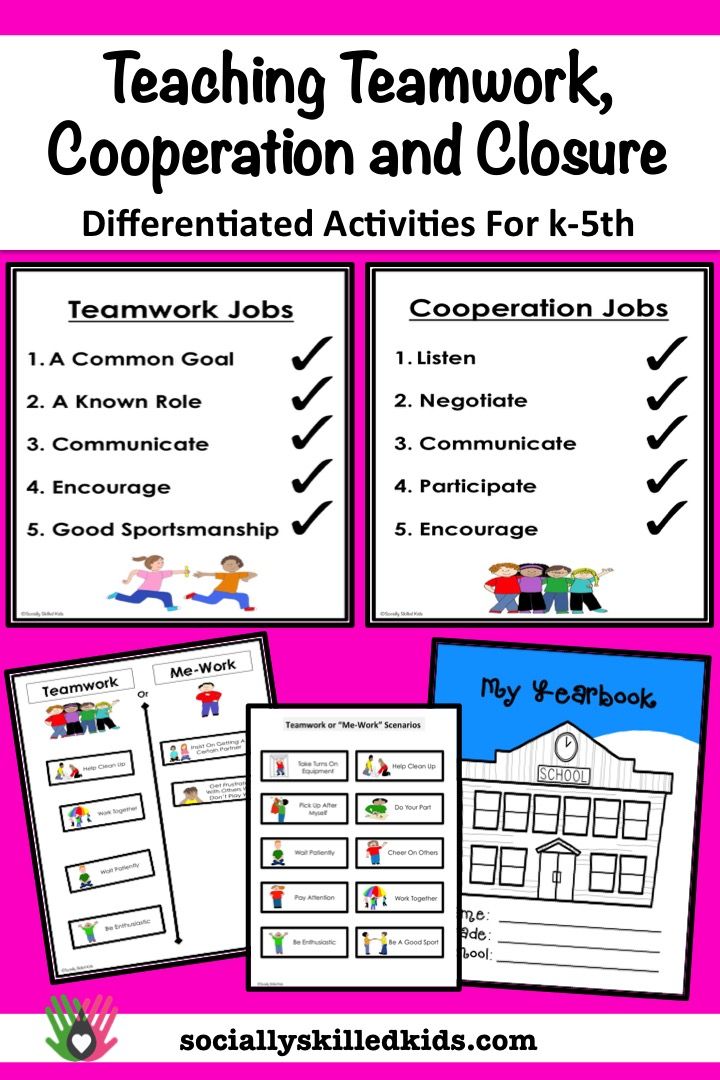

2. Assign classroom jobs

Assigning classroom jobs to students provides opportunties to demonstrate responsibility, teamwork and leadership. Jobs such as handing out papers, taking attendance, and being a line-leader can highlight a student's strengths and in turn, build confidence. It also helps alleviate your workload! Teachers often rotate class jobs on a weekly or monthly basis, ensuring that every student has an opportunity to participate. Check out this list of classroom jobs for some ideas!

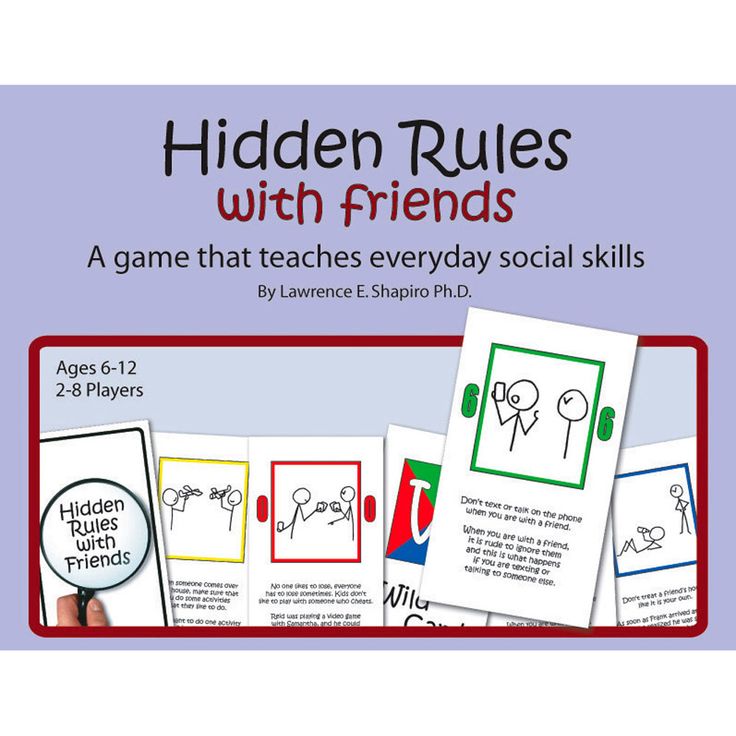

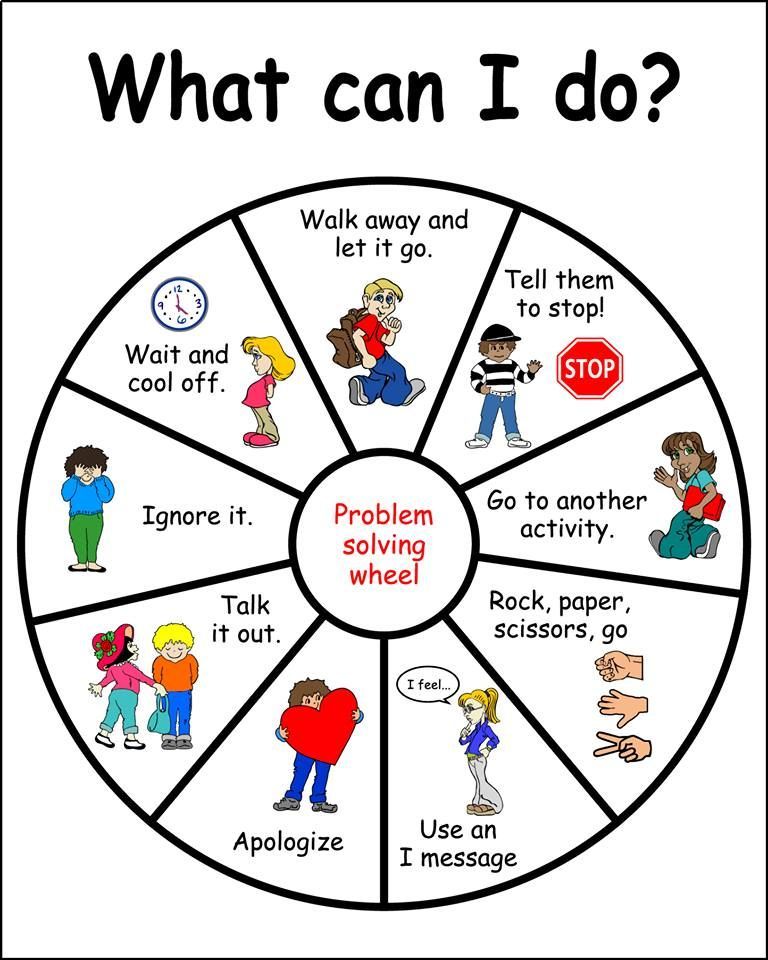

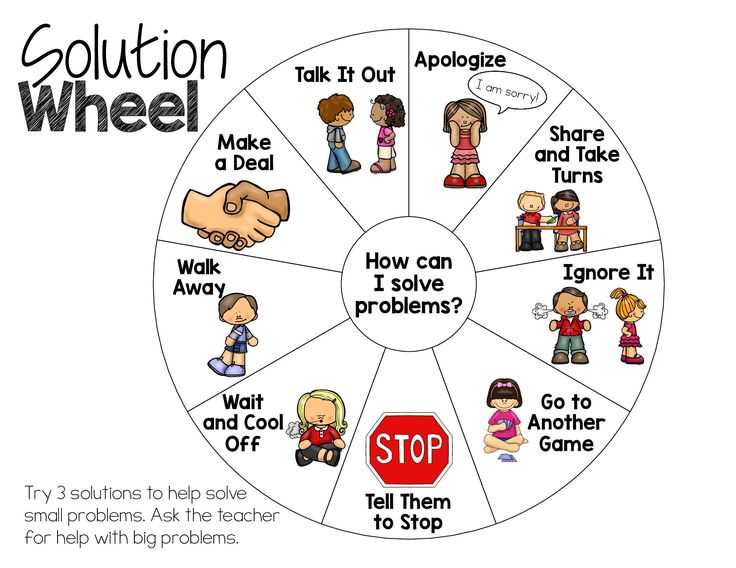

3. Role-play social situations

As any teacher knows, it's important to not only teach the students a concept or lesson but then give them a chance to practice what they have learned. For example, if we teach students how to multiply, then we often provide a worksheet or activity for the students to show us their understanding of mulitiplication. The same holds true for teaching social skills. We need to provide students with opportunities to learn and practice their social skills. An effective method of practice is through role-playing. Teachers can provide structured scenarios in which the students can act out and offer immediate feedback. For more information on how to set-up and support effective role-playing in your classroom have a look at this resource from Learn Alberta.

An effective method of practice is through role-playing. Teachers can provide structured scenarios in which the students can act out and offer immediate feedback. For more information on how to set-up and support effective role-playing in your classroom have a look at this resource from Learn Alberta.

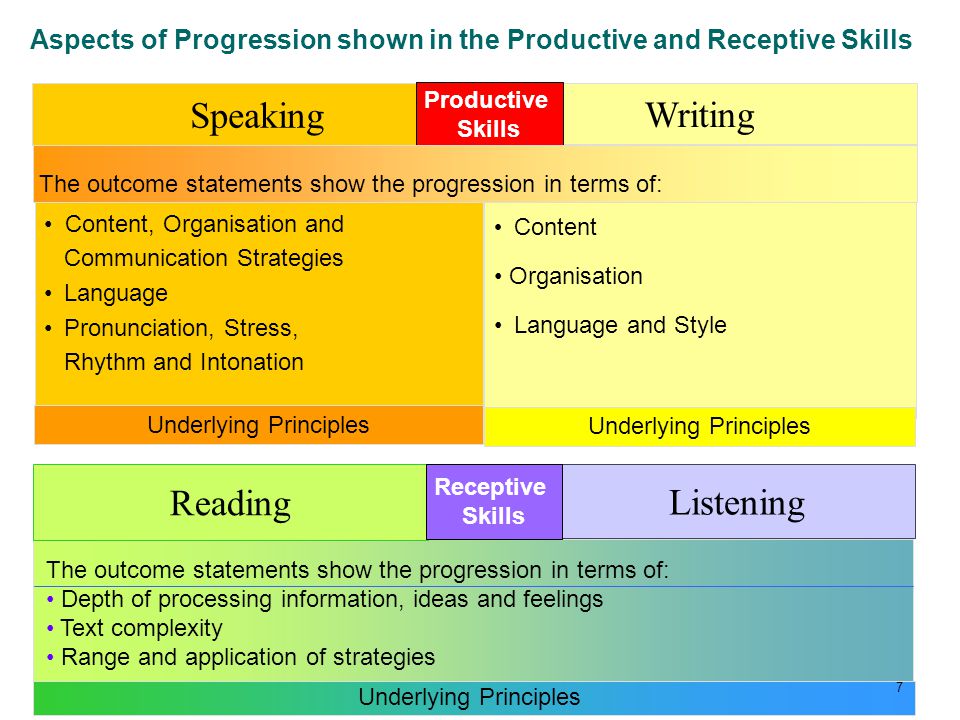

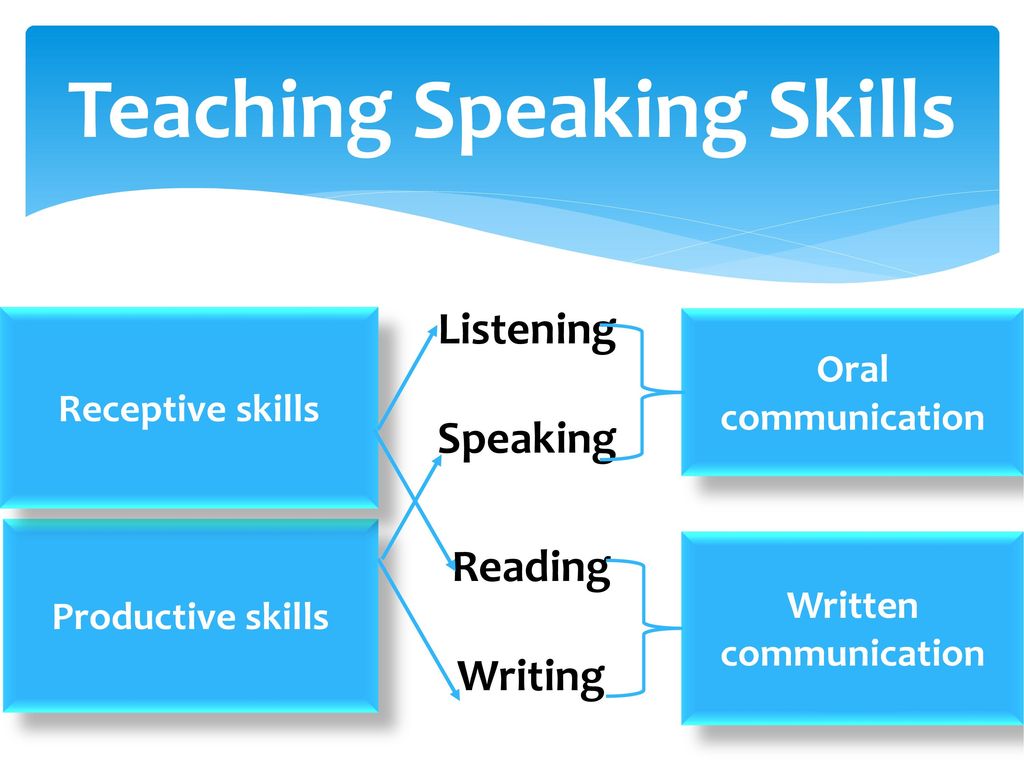

4. Pen-pals

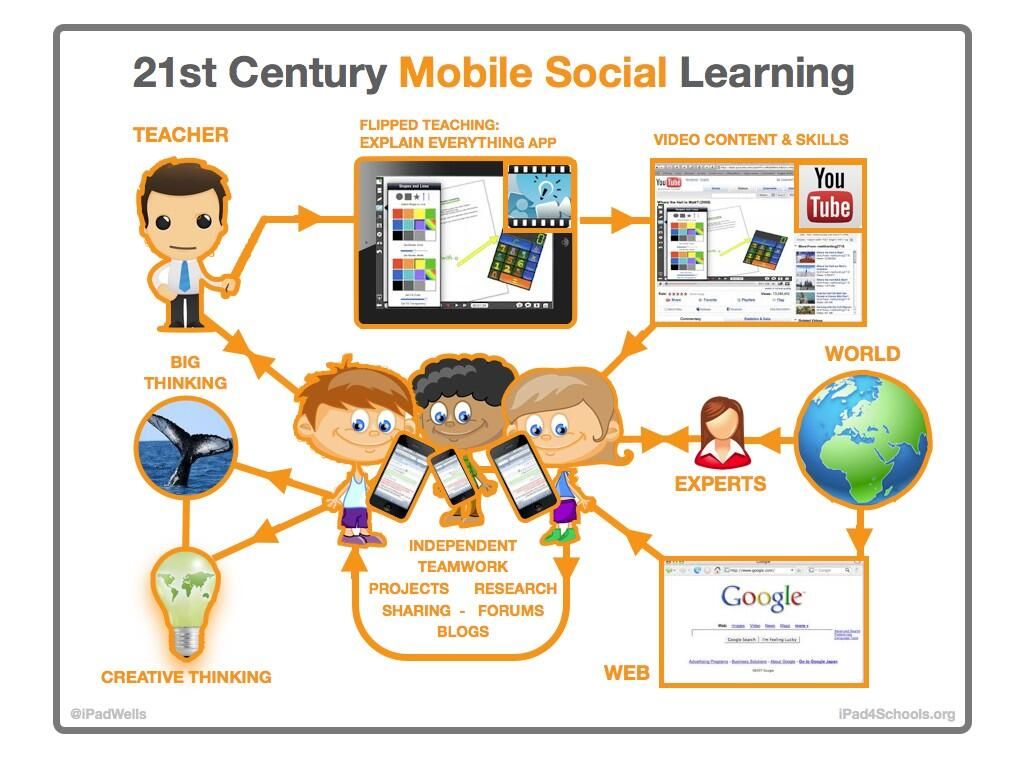

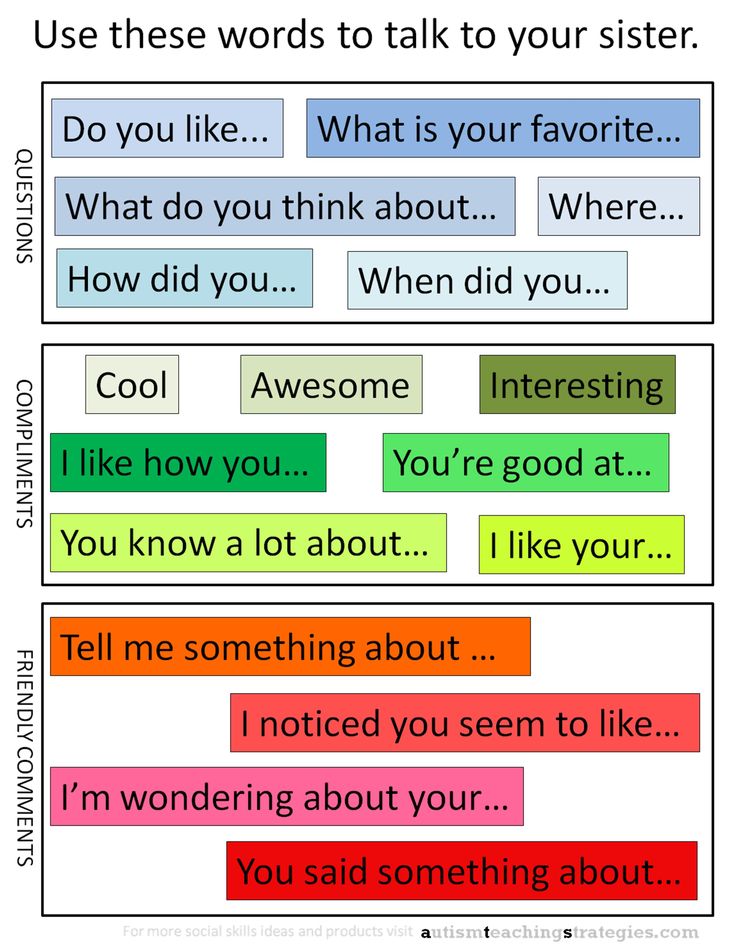

For years, I arranged for my students to become pen-pals with kids from another school. This activity was a favorite of mine on many different academic levels; most importantly it taught students how to demonstrate social skills through written communication. Particularly valuable for introverted personalities, writing letters gave students time to collect their thoughts. It levelled the playing field for students who had special needs or were non-verbal. I was also able to provide structured sentence frames in which the kids held polite conversation with their pen-pal. Setting up a pen-pal program in your classroom takes some preparation before the letter writing begins. You want to ensure that students have guidelines for content and personal safety. This article, Pen Pals in the 21st Century, from Edutopia will give you some ideas!

You want to ensure that students have guidelines for content and personal safety. This article, Pen Pals in the 21st Century, from Edutopia will give you some ideas!

5. Large and small group activities

In addition to the academic benefits, large and small group activities can give students an opportunity to develop social skills such as teamwork, goal-setting and responsibility. Students are often assigned roles to uphold within the group such as Reporter, Scribe, or Time-Keeper. Sometimes these groups are self-determined and sometimes they are pre-arranged. Used selectively, group work can also help quieter students connect with others, appeals to extroverts, and reinforces respectful behavior. Examples of large group activities are group discussions, group projects and games. Smaller group activities can be used for more detailed assignments or activities. For suggestions on how to use grouping within your classroom, check out this article, Instructional Grouping in the Classroom.

6. Big buddies

We know that learning to interact with peers is a very important social skill. It is just as important to learn how to interact with others who may be younger or older. The Big Buddy system is a great way for students to learn how to communicate with and respect different age groups. Often an older class will pair up with a younger class for an art project, reading time or games. Again, this type of activity needs to be pre-planned and carefully designed with student's strengths and interests in mind. Usually, classroom teachers meet ahead of time to create pairings of students and to prepare a structured activity. There is also time set aside for the teacher to set guidelines for interaction and ideas for conversation topics. Entire schools have also implemented buddy programs to enrich their student's lives. Here is an article that offers tips on how to start a reading buddy program.

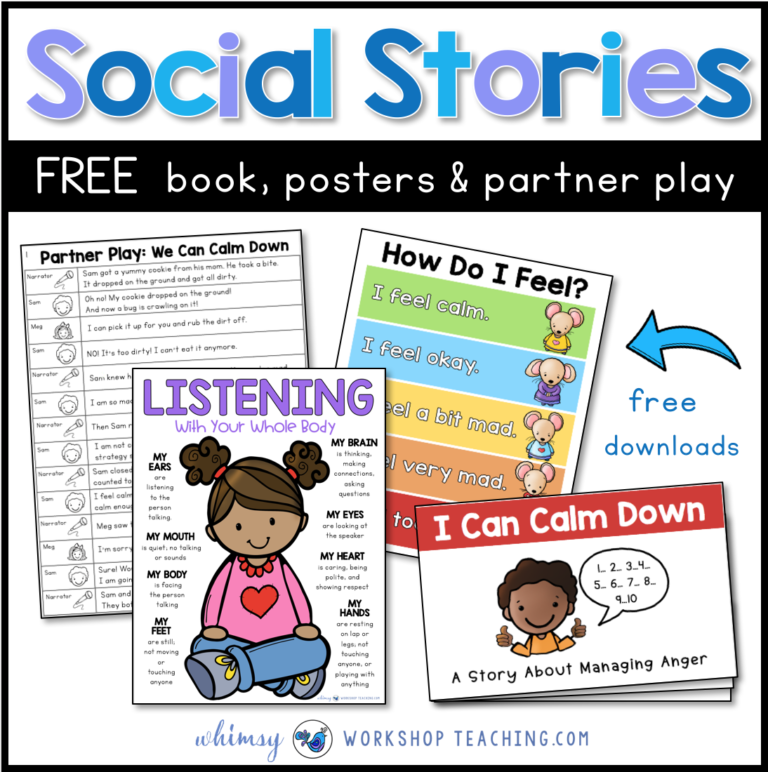

7. Class stories

There are dozens of stories for kids that teach social skills in direct or inadvertant ways. Find strategies to incoporate these stories in your class programs. You can set aside some time each day to read-aloud a story to the entire class or use a story to teach a lesson. Better yet, have your class write their own stories with characters who display certain character traits.

Find strategies to incoporate these stories in your class programs. You can set aside some time each day to read-aloud a story to the entire class or use a story to teach a lesson. Better yet, have your class write their own stories with characters who display certain character traits.

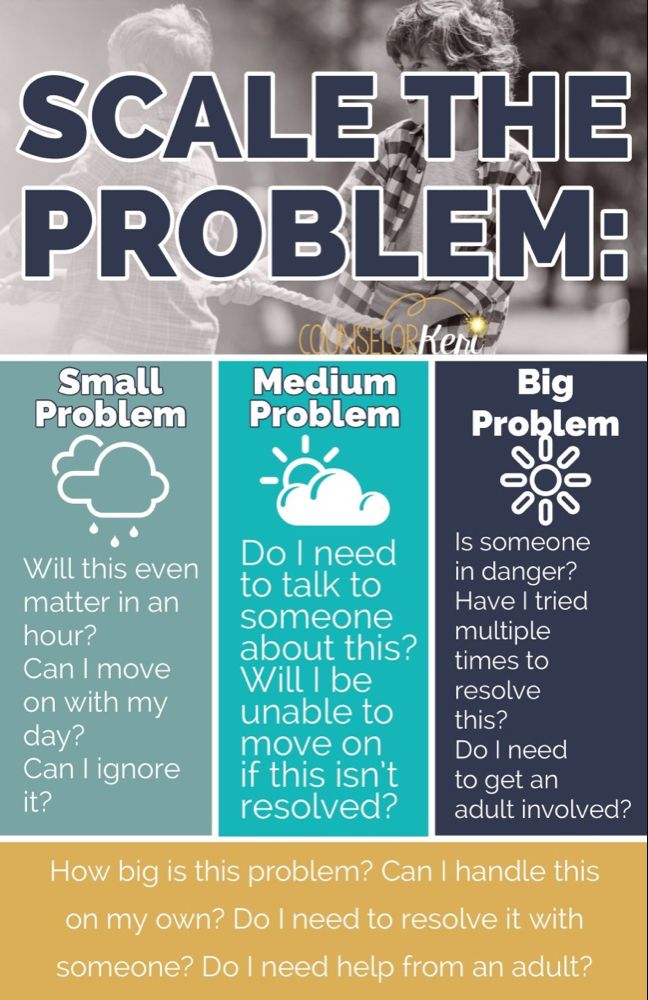

8. Class meeting

Class Meetings are a wonderful way to teach students how to be diplomatic, show leadership, solve problems and take responsibility. They are usually held weekly and are a time for students to discuss current classroom events and issues. Successful and productive meetings involve discussions centered around classroom concerns and not individual problems. In addition, it reinforces the value that each person brings to the class. Before a class meeting, teachers can provide the students with group guidelines for behavior, prompts, and sentence frames to facilitate meaningful conversation. Here is a great article, Class Meetings: A Democratic Approach to Classroom Management, from Education World that describes the purpose and attributes of a class meeting.

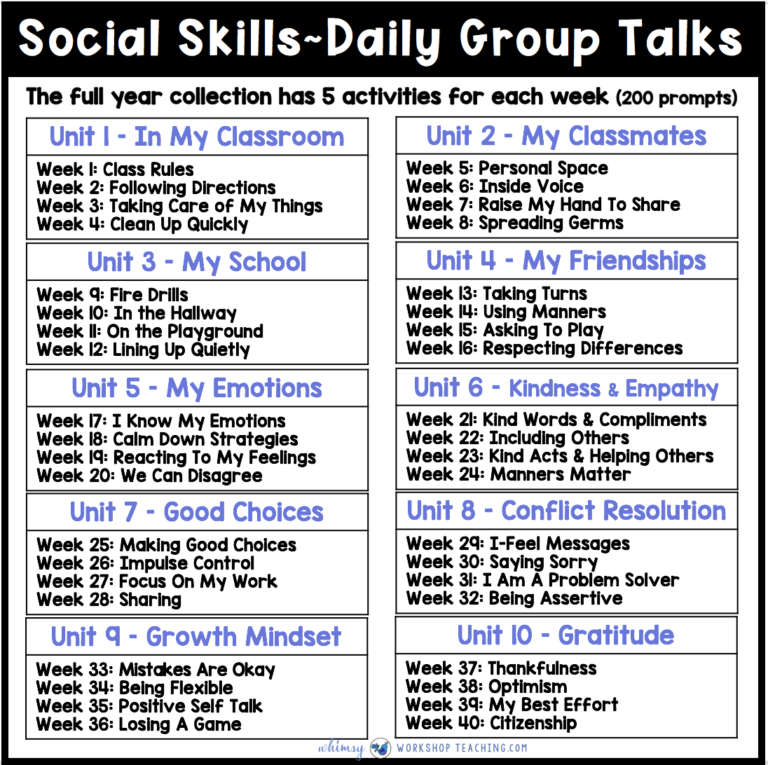

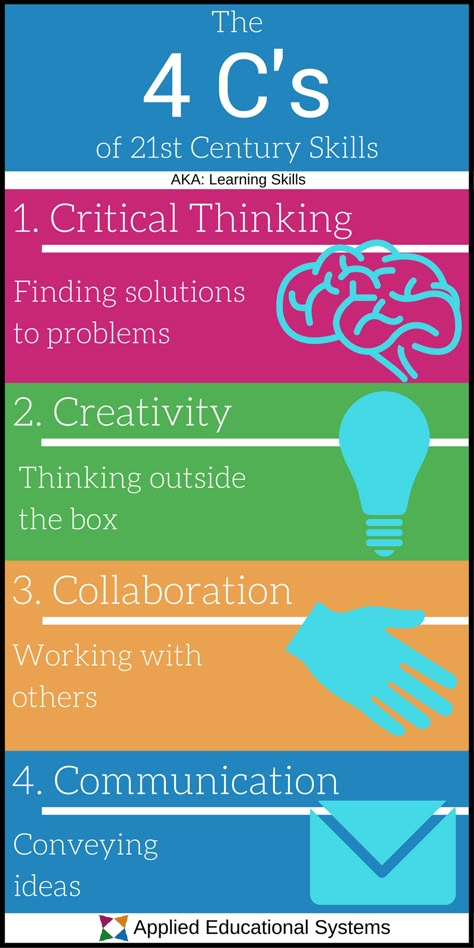

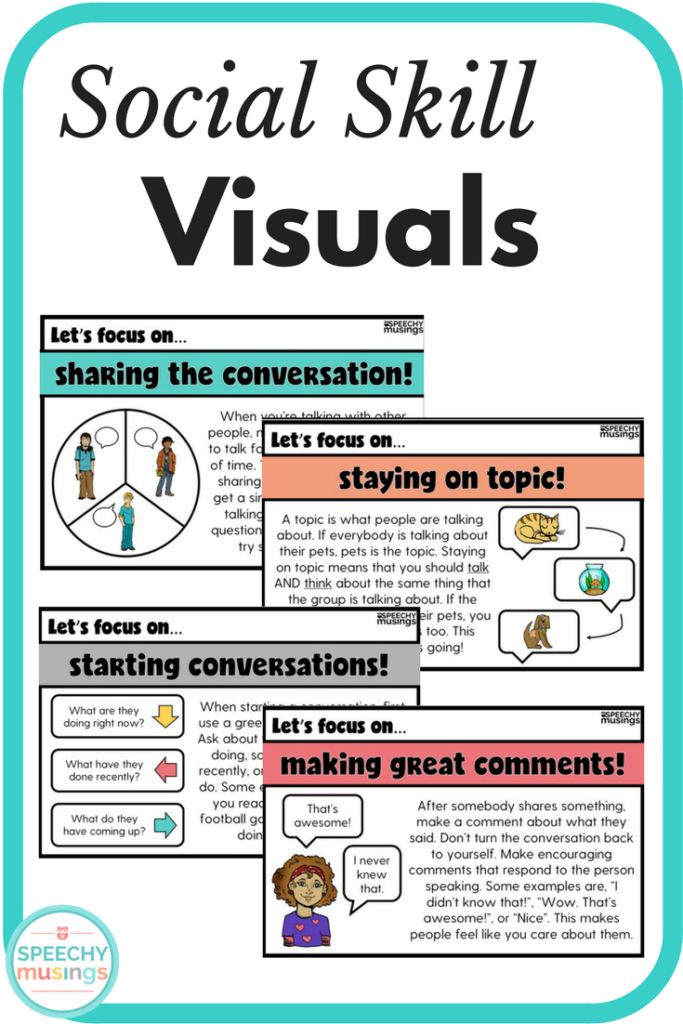

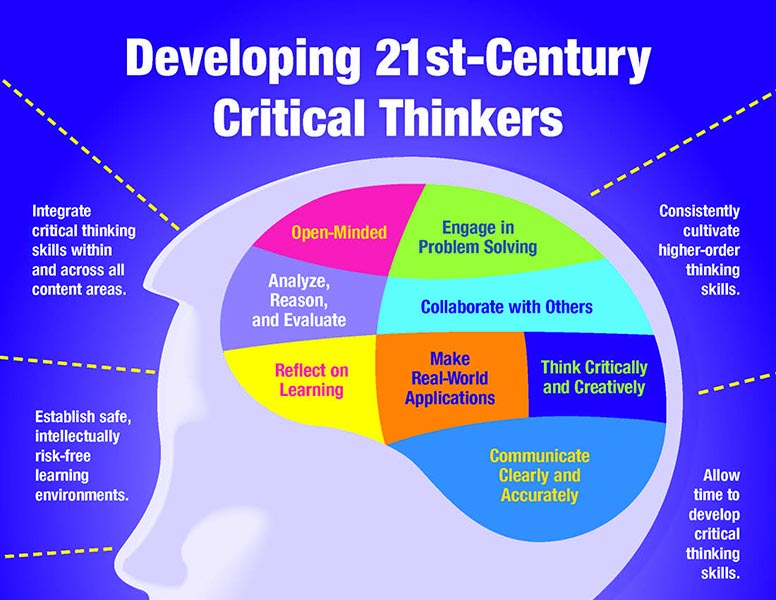

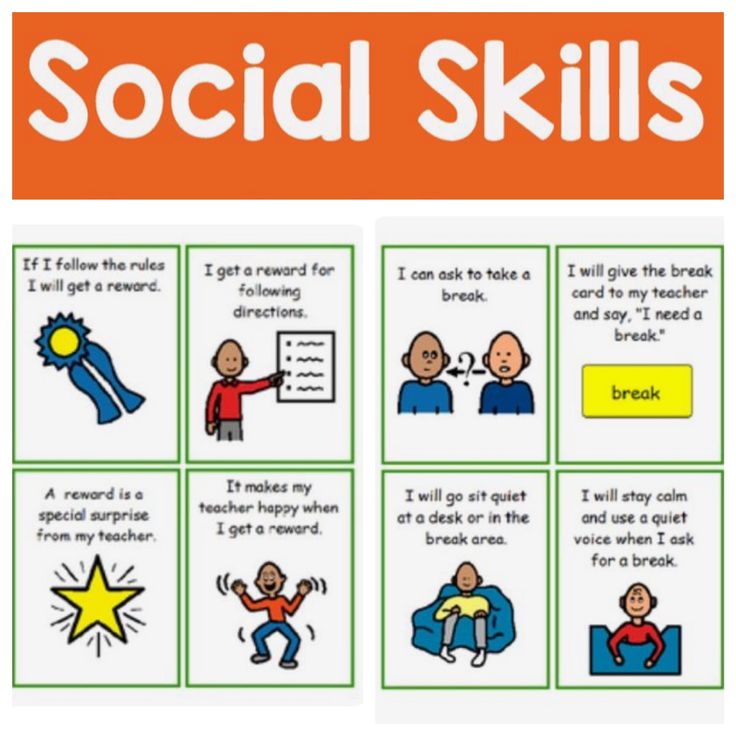

9. Explicit instruction

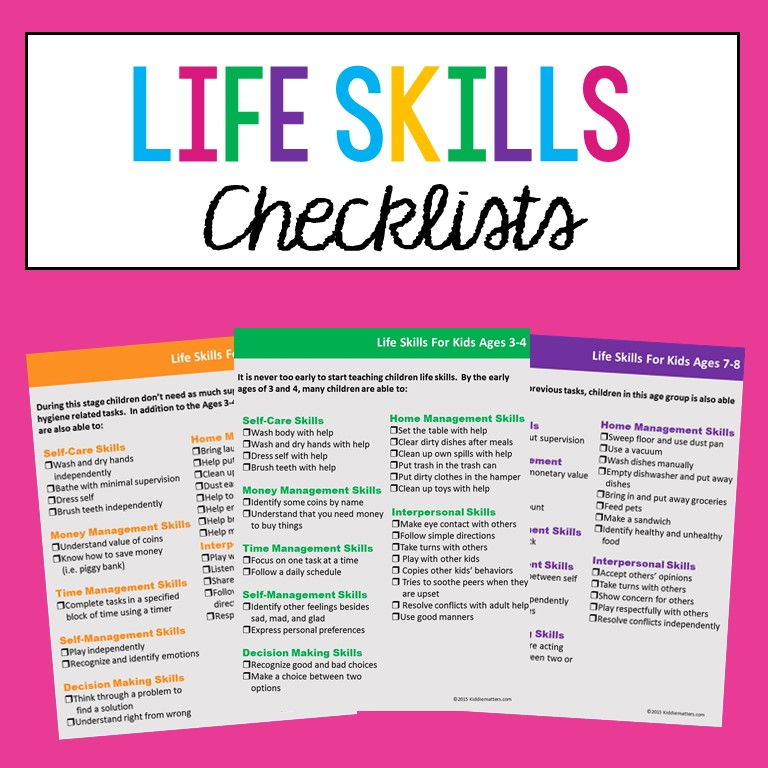

Finally, teachers can carve out a time in their curriculum to directly teach social skills to their students. Research-based programs such as Second Step provide teachers and schools with explicit lessons for social development. These programs can provide schools and classrooms with a common language, set of behavior expectations, and goals for the future. I have used programs such as Second Step in my classrooms with much success!

Nicole Eredics is an educator who specializes in the inclusion of students with disabilities in the general education classroom. She draws upon her years of experience as a full inclusion teacher to write, speak, and consult on the topic of inclusive education to various national and international organizations. She specializes in giving practical and easy-to-use solutions for inclusion. Nicole is creator of The Inclusive Class blog and author of a new guidebook for teachers and parents called, Inclusion in Action: Practical Strategies to Modify Your Curriculum. For more information about Nicole and all her work, visit her website.

For more information about Nicole and all her work, visit her website.

Related Topics

Social-Emotional Learning

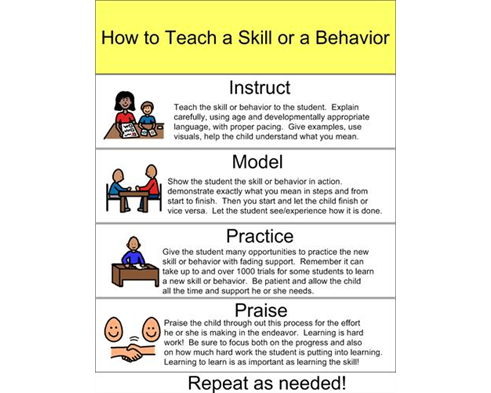

How to Teach Social Skills, Step by Step

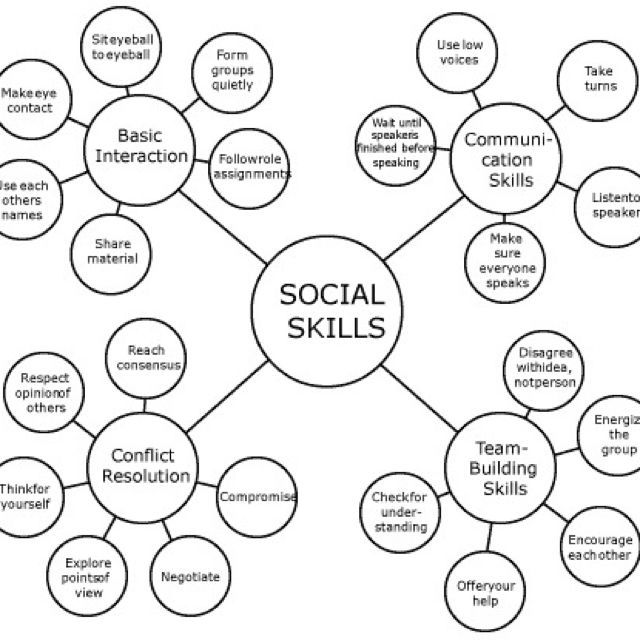

Seating students together is not enough to ensure teamwork. Many kids have very little idea how to interact appropriately with their classmates. They simply lack the social skills needed to perform the most basic cooperative learning tasks. Lack of social skills is probably the biggest factor contributing to lack of academic success in teams. Fortunately, social skills can be taught just like academic skills. If you use a systematic approach like the one described below, you’ll find that your students CAN learn how to interact appropriately and become productive team members.

Listen to the Podcast: How to Teach Social Skills for Working Together

For more information about how to teach social skills, listen to Episode 7 of my Inspired Teaching Made Easy podcast below.

Six Step Process for Teaching Social Skills

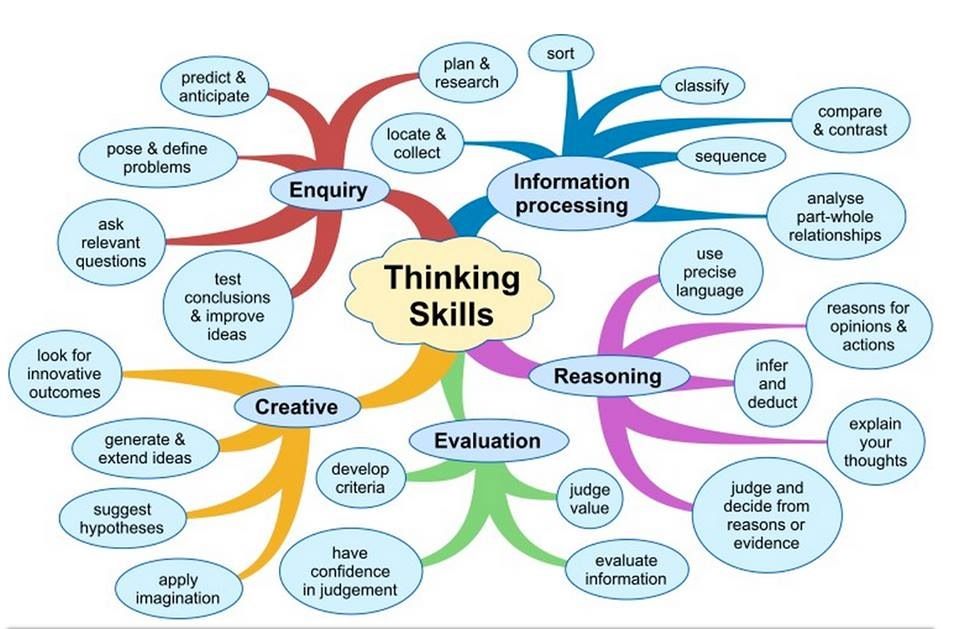

1. Discuss the Need for Social Skills

Discuss the Need for Social Skills

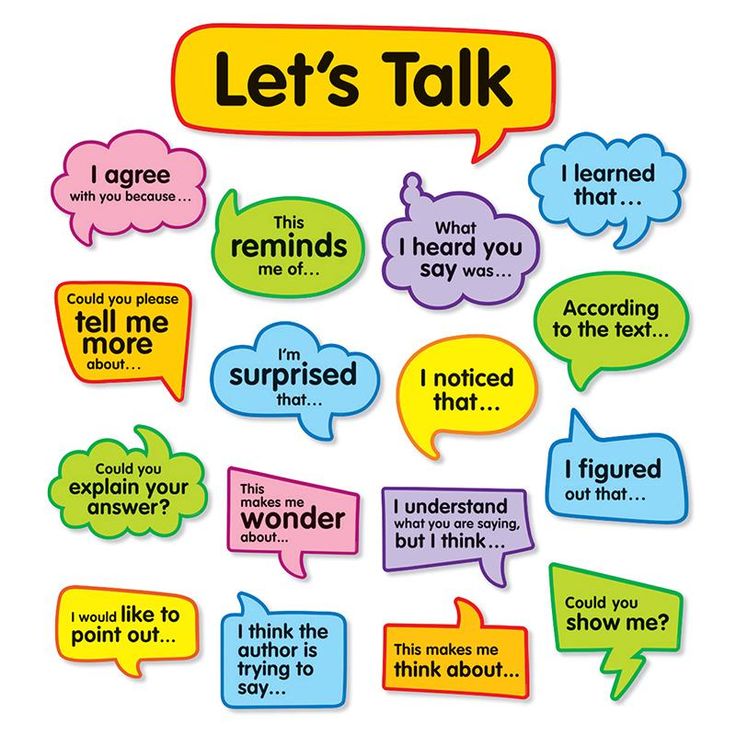

Before you can help students improve their social skills, they need to understand why these skills are important. You might begin by asking your students to think about problems they may have experienced when working in groups, such as team members not listening to each other or not taking turns. Explain that most of these problems are caused by poor “social skills,” sometimes known as “people skills.” You might even mention that sometimes adults need to work on their social skills, too! Brainstorm a list of social skills that might make it easier for students to work together in teams. If they can’t think of any social skills for working together, share some of the suggestions from the list below.

2. Select a Social Skill

Even though your students may need to work on several different social skills, it’s best to focus on just one skill at a time. You can start with the skill you feel is most important, or you can let your class decide which skill they need to work on at a given time. I like to start with “Praising,” which might also be stated as “Showing Appreciation,” because when kids master this skill, all of the other skills are easier to learn.

I like to start with “Praising,” which might also be stated as “Showing Appreciation,” because when kids master this skill, all of the other skills are easier to learn.

3. Teach the Social Skill

Step 3 is to teach the skill explicitly so that your students know exactly what to do and what to say in order to master the social skill. For this part of the lesson, you can use the Working Together Skills T-chart below by projecting it on a whiteboard or drawing it on anchor chart paper.

Write the name of the social skill in the box at the top of the Working Together Skills chart. Then ask your students to help you brainstorm what they might do and what they might say when demonstrating the social skill. Write what they might DO under the Looks Like heading because this is what the skill looks like when it is demonstrated. Write the words they might SAY under the Sounds Like heading because this is what the skill might sound like to someone who is observing the activity.

Examples for the social skill of Praising:

Looks Like: Thumbs up, Clapping, Smiling

Sounds Like: Terrific! I knew you could do it! Way to go! I like the way you…

4. Practice the Skill

After you complete the Working Together Skills chart with your students, it’s important to have them practice the skill right away by participating in a structured cooperative learning activity. For example, if you taught Active Listening as the social skill, you might follow up with a team discussion activity in which students take turns answering questions or sharing ideas around the team. Here a a few suggestions for cooperative learning structures you can use to practice specific social skills:

Social Skills and Cooperative Learning Structures

| Social Skills | Structures for Practice* |

| Active Listening | Roundrobin, Think-Pair-Share, Mix-Freeze-Pair |

| Praising | Rallytable, Roundtable, Pairs Check, Showdown |

| Taking Turns | Rallytable, Pairs Check, Roundtable |

| Using Quiet Voices | Think-Pair-Share, Numbered Heads Together, Showdown |

| Staying on Task | Rallytable, Roundtable, Pairs Check, Showdown, Mix-N-Match |

| Helping or Coaching | Rallytable, Pairs Check, Showdown, Mix-N-Match |

| Using Names | Mix-N-Match, Mix-Freeze-Pair, Showdown |

Spencer Kagan’s book, Cooperative Learning. Spencer Kagan’s book, Cooperative Learning. | |

5. Pause and Reflect

Sometime during the practice activity, use an attention signal to stop the class. Ask them to think about how they’ve been using the social skill. If you have observed teams or individuals doing a good job with the skill, share your observations with the class. Challenge students to continue to work on their use of the social skill as they complete the activity. Refer to your Working Together Skills T-chart if students have forgotten what the skill Looks Like and Sounds Like.

6. Review and Reflect

At the end of the activity, reflect again on how well the social skills were used. Take a few minutes to discuss the positive interactions that were happening, and aspects of the social skill that still need work. This is a also a perfect opportunity for personal journal writing and reflections. Consider these writing prompts:

- How well was the social skill being used on your team? What specific examples do you remember?

- How did you personally use the social skill? What did you do and/or say? To whom?

- How might you improve in using this skill next time?

By the way, it’s not necessary to follow all six steps every time you teach a new social skill. The most important elements are explicitly teaching of the skill and immediately following the instruction with a cooperative activity to practice the skill. The reflection steps are important and should be included as often as possible, too.

The most important elements are explicitly teaching of the skill and immediately following the instruction with a cooperative activity to practice the skill. The reflection steps are important and should be included as often as possible, too.

Modification for Younger Students

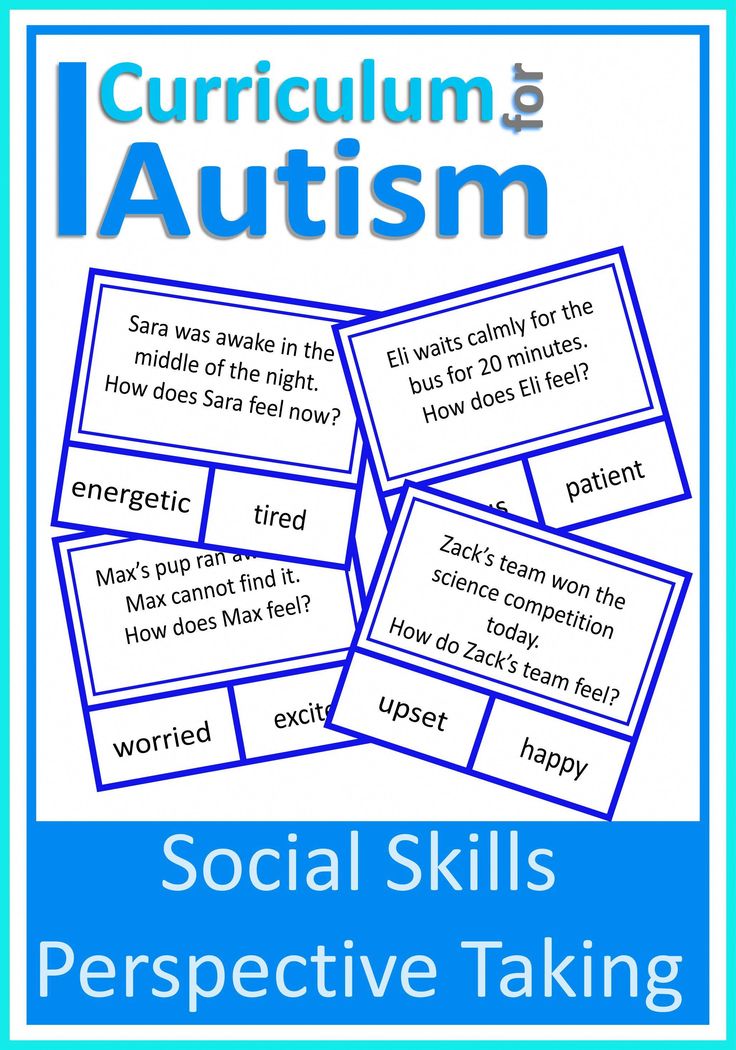

Younger students or special needs students could benefit from watching an excellent video created by Model Me Kids called Time for School. This video shows students exactly how to perform specific social skills. Even if you don’t use the video with your students, you might be interested in viewing it yourself to see how social skills can be broken down into steps and taught. If the video is appropriate for your students, they could watch it before completing the Working Together Skills chart above.

Social skills training • Mosaic

What is a good way to teach social skills, especially in the group?

I work with children with autism. I confidently teach them academic and everyday skills, but, unfortunately, not social ones. I need a simple and effective flexible learning method as I need to teach a variety of skills to children of different levels. Many of my students have intermediate or advanced language skills but find it difficult to make friends and maintain relationships. Since it is not possible to organize individual work with each student, something is needed that can be done in a group. Any suggestions?

I need a simple and effective flexible learning method as I need to teach a variety of skills to children of different levels. Many of my students have intermediate or advanced language skills but find it difficult to make friends and maintain relationships. Since it is not possible to organize individual work with each student, something is needed that can be done in a group. Any suggestions?

Answered by Shanti Stockley, Master of Education (MEd), Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), Licensed Behavior Analyst (LBA) Autism Treatment Association.

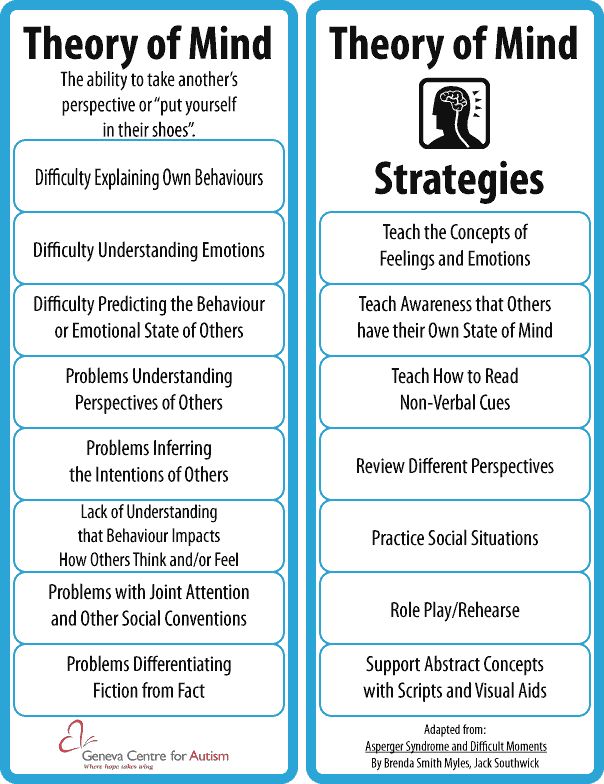

Although the amount of research available on social skills education is increasing, this question remains very common. It can be difficult for educators to find evidence-based curricula and strategies. One strategy that has proven effective in teaching social skills to children of different levels in groups is the Teaching Interaction Procedure (TIP). The learning interaction method is a 6-step process in which the educator names and defines the skill being learned, explains the need for its application, describes the steps necessary to perform it correctly, demonstrates this skill, conducts practical exercises with students in the form of a role-play, and also gives give them feedback and reinforcement. Over the past ten years, this procedure has been repeatedly studied, including its use in individual work with a child (for example, Leaf et al., 2009), in groups (e.g. Leaf, Dotson, Oppeneheim, Sheldon and Sherman, 2010) and in schools (Tullis and Gallagher, 2016). In this issue of Clinical Corner, I will share how this method is commonly used, demonstrate a variation of the procedure that may help you, compare it to other teaching methods, and tell you where to find more information.

Over the past ten years, this procedure has been repeatedly studied, including its use in individual work with a child (for example, Leaf et al., 2009), in groups (e.g. Leaf, Dotson, Oppeneheim, Sheldon and Sherman, 2010) and in schools (Tullis and Gallagher, 2016). In this issue of Clinical Corner, I will share how this method is commonly used, demonstrate a variation of the procedure that may help you, compare it to other teaching methods, and tell you where to find more information.

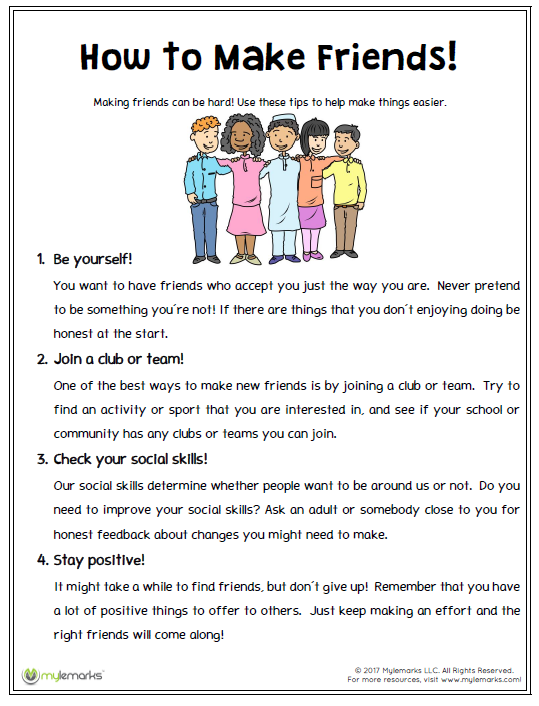

Before you start teaching social skills, first choose the skills you will teach and develop an appropriate motivation system. While identifying the skills to learn is out of the scope of this article, it is perhaps more important than how you teach it! Teaching essential skills (that are appropriate to the student's level on the assessment, meaningful to the child and their environment, and open up new opportunities for them) is both extremely important and difficult at the same time. The process of learning in a group increases the complexity. For guidance on setting goals and assessing social skills, see Chapters 1 and 5 of Teaching Social Skills to People with Autism: Best Practices for Individual Intervention (Bondy and Weiss, 2013) by clicking here. Once the skills are chosen, set up a motivation system so that the children put in the best effort in practice. To do this, it is necessary to identify one or more favorite activities or subjects that each child would like to receive. Next, come up with a system of points or tokens that he can exchange for the selected reward. You can see how to do this effectively in the ASAT Intervention Summary. Once you've completed these steps, you're ready to start learning.

For guidance on setting goals and assessing social skills, see Chapters 1 and 5 of Teaching Social Skills to People with Autism: Best Practices for Individual Intervention (Bondy and Weiss, 2013) by clicking here. Once the skills are chosen, set up a motivation system so that the children put in the best effort in practice. To do this, it is necessary to identify one or more favorite activities or subjects that each child would like to receive. Next, come up with a system of points or tokens that he can exchange for the selected reward. You can see how to do this effectively in the ASAT Intervention Summary. Once you've completed these steps, you're ready to start learning.

The following is a more detailed description of how the six steps of the learning interaction procedure work in practice. Examples are given that include teaching in the format of individual and group lessons for children of primary school and adolescence, both with an average and a higher level of social skills.

Step 1. Skill name and definition : Tell students what they will be learning. Give the skill a name that is descriptive and appropriate for the child's developmental level. Ask each child to tell what this skill is. It is very important that students actively respond. Therefore, each stage should include opportunities for responses. Don't let the procedure turn into a lecture!

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “Susie, we will learn how to say hello to our friends. What are we going to do today?" | "Say hello to friends!" |

| Teens In the classroom | Hello children! Today we will practice changing the topic of conversation. John, what are we going to learn today?” | "We will learn to change the subject of conversation." |

Stage 2 Skill and Prompt Need: Explain to the children why they need the skill being learned. The explanation should contain natural, significant for students, consequences of applying the skill. You could give an example and ask each child to give their own explanation. Describe the environment or landmarks that indicate the right moment to use this skill. Ask each student to share when they will use this skill.

The explanation should contain natural, significant for students, consequences of applying the skill. You could give an example and ask each child to give their own explanation. Describe the environment or landmarks that indicate the right moment to use this skill. Ask each student to share when they will use this skill.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “If you say hello to your friends, they will want to play with you. Why say hello to friends? | "For them to play with me." |

| Junior students Individually | “You can say hello to Bobby when he comes to the water play table. Who will you say hello to? | "Bobby". |

| Teenagers in the classroom | “It is important to be able to change the topic of conversation correctly so that friends do not get tired of talking about the same thing and leave. Sarah, why do you think we need to change the subject?” Sarah, why do you think we need to change the subject?” | "So that my friends can also talk about whatever they want." |

| Teenagers in the classroom | “For example, I need to use this skill when I talk to my daughter about school so that she can talk about other topics that she is interested in. Jordan, when do you need to change the subject?" | "When I talk about myself for a long time." |

Stage 3 - Divide the skill into steps .

Before learning, divide a skill into a sequence of steps (usually 2 to 5). The number of steps should match the number of important elements of the skill being learned and be easy to remember. Tell the students about each step and ask them to say it in order.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “When you say 'hello' to a friend, look at her, smile and say 'hello' in a friendly voice. How do you say hello to your girlfriend? How do you say hello to your girlfriend? | "I'll look at her... I'll say hello in a friendly voice." |

| Teens In the classroom | “This is a good way to change the subject. First, wait for a pause. Second, use a transition phrase to link the old topic to the new one. A passphrase is a phrase like “By the way, oh…” or “That reminds me of…”, etc. Third, suggest a new topic. Fourth, observe your interlocutor to see if he is interested in a new topic. Who can remember all four steps when changing the subject? John, try it” | “Um…wait for a pause, then say a passphrase. Start talking about a new topic and see what others are interested in” |

Step 4 - Skill Demonstration : Demonstrate the skill you are teaching.

Educational interactions often (but not always) show both right and wrong behavior so that children learn to distinguish between right and wrong responses. First, demonstrate the skill incorrectly by doing only some of the steps. Ask students to answer if everything was done correctly. Then ask the children to tell what went wrong and how to fix it. Show the correct behavior. You can demonstrate the skill with another adult, a specially trained peer, one of the students and, in some cases (depending on the skill itself), on your own.

First, demonstrate the skill incorrectly by doing only some of the steps. Ask students to answer if everything was done correctly. Then ask the children to tell what went wrong and how to fix it. Show the correct behavior. You can demonstrate the skill with another adult, a specially trained peer, one of the students and, in some cases (depending on the skill itself), on your own.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “Look how I say hello to my friend Mrs. Smith. Tell me if I'm doing it right." Look at Mrs Smith with a serious expression and say hello. “Did I do everything right? What did I do wrong? | “No! You didn't smile and your voice wasn't sweet." |

| Junior students Individually | “That's right! How can I do it right?" | "You should smile and say in a sweet voice like this:" Hello! |

| Junior students Individually | “Well done! I'll try again. Tell me if I'm doing the right thing…” Tell me if I'm doing the right thing…” | |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Look how I change the subject. And tell me if I followed all four steps correctly. Sarah, you will be my partner. Let's talk about our favorite music and I'll change the subject." | Sarah: "Who is your favorite singer?" |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “I like the Beatles. And you?" | Sarah: "I like Taylor Swift." |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “Yesterday, while jogging, I lost my favorite headphones…” “Guys, how did I manage? On the count of three, thumbs up if I've completed all the steps and thumbs down if I haven't. One two Three!" | Pupils show thumbs down. |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Everyone thinks that she didn't do it. Right! What did I do wrong and how can I fix it? | "You didn't use a passphrase. " " |

| Teenagers Classroom | “That's right! I missed the passphrase. Who can invent it? | “Speaking of listening to music…” |

Stage 5 - Role Play: Give each student the opportunity to demonstrate the skill in a role play with you. Look for clues and hints that trigger the application of the skill being learned. Give feedback after the skill has been demonstrated by the students. Clarify what was done right and what mistakes were made. If there were mistakes, ask the children to try again. If mistakes are made the second time, it may be necessary to use a hint during the role-play to increase the chances of the children being successful on the third attempt.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “When Mrs. Smith comes into the room, show me how you say hello to her. (Mrs Smith comes in) (Mrs Smith comes in) | Susie looks at her, smiles and says "hello" in a joyful voice. |

| Junior students Individually | “Well done, Susie! You looked at Mrs Smith and said hello to her in a friendly voice. | |

| Teenagers Classroom | Now it's your turn to show the group how to change the subject. John, you start. I will be your partner. We'll start talking about Pokémon and you'll change the subject" "When I was playing Pokémon the other day, I…" | 0007 World of Warcraft ?” |

| Teenagers Classroom | With a pitiful look “No…” | “She's cool! What I like the most is the new equipment that I can use. There is one spell that can be cast…” |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Let's stop there. John, you said a great transitional phrase "by the way, about video games" and started a new topic that is relevant to the question asked. But you did not wait for a pause in the conversation, and also did not follow my face. You did not notice that I was not interested in a new topic. Try again". John, you said a great transitional phrase "by the way, about video games" and started a new topic that is relevant to the question asked. But you did not wait for a pause in the conversation, and also did not follow my face. You did not notice that I was not interested in a new topic. Try again". |

Stage 6 - Feedback and Reinforcement: It is desirable that throughout the procedure the student receives reinforcement (usually praise along with some other prize) for correct answers, and in case of errors - corrective feedback. Before starting training, determine the child's preferences and objects that can be used as reinforcement. Token or point systems are effective for this purpose. During the lesson, children receive points or tokens for correct answers (Steps 1-4) and correct use of the skill during the role-play (Step 5). At the end of the lesson, the students exchange them for a reward. The order of issuing tokens can be as follows: for the correct performance of the skill on the first attempt, give two tokens, on the second - one token, in case of a correct answer using the hint on the third attempt - praise. This will happen at every stage of the learning interaction procedure, not just at the end of the

This will happen at every stage of the learning interaction procedure, not just at the end of the

Below is another example of a learning interaction procedure, also used in group sessions with elementary school students. This example includes a feedback/rewards process (tokens are issued throughout the process).

| Step | Teacher | Students |

| Step 1: Naming and defining the skill | “Today we will learn how to invite a friend to play a game. Guys, what are we going to learn to do? | (in unison) "Invite a friend to play a game!" |

| "That's right!" (give each student two tokens) | ||

| Step 2: Explain the need for the skill and environmental guidelines | “Why is it important to invite friends to play? Olive, what do you think?" | Olive : « I am not know ". |

| “Try to answer. Why would you want to invite a friend to play together?” | Olive: "That'll be more fun." | |

| "Yes, it's more fun!" (give Oliver 1 token for the correct answer on the second try, ask the rest of the children until each of them gives their own explanation). “When will you invite a friend to play? For example, you can invite a friend who is watching the game. Levi, when are you going to invite a friend to play together?” | Levy: "I'm going to invite Cayden to play Square because I know he likes the game." | |

| “Great idea! I'm sure Cayden will be very happy!" (give Levi two tokens for the correct answer on the first try, ask the rest of the children) | ||

| Step 3: Skill division into steps | “You can invite a friend to play in the following way: first, find a person who might be interested. Choose a friend who is not currently playing something else. Second, approach him in a friendly way. It means to come up and smile. Third, tell what you are doing and ask if he would like to join. Fourth, if the friend agreed, tell them exactly how they can join the game, for example, say: "You can be on my team" or "You can draw with this marker." You had to memorize many steps. Let's try to say them all. Calvin, you begin." Choose a friend who is not currently playing something else. Second, approach him in a friendly way. It means to come up and smile. Third, tell what you are doing and ask if he would like to join. Fourth, if the friend agreed, tell them exactly how they can join the game, for example, say: "You can be on my team" or "You can draw with this marker." You had to memorize many steps. Let's try to say them all. Calvin, you begin." | Calvin: "Find a friend to play with and ask him if he wants to." |

| “You named two steps out of four! The two steps you missed: approach in a friendly way, and then tell how you can join. | Calvin: “Okay. Find a friend to play with, ask him to join, and tell him how to join" . | |

| “Nice try. You named three steps out of four. Try again and I'll help you remember when to approach in a friendly way." | Calvin: "Find a friend to play with. .." .." | |

| Interrupts the student with the words "and come..." | “And approach in a friendly way. Ask to play together and tell how you can join. | |

| “You named all the steps! Great!" (do not give tokens because the child needed a hint to get the correct answer. Continue with the next student).” | ||

| Step 4: Skill Demonstration | “Now I will show you how to invite someone to play. I can do everything right, or I can make a mistake. Look carefully and tell me if I did the right thing or not. (Demonstrate a skill with a colleague who is "passionate about playing another game." Follow all steps except the first one: "Find a buddy who might want to play together.") | |

| “So, tell me, did I do everything right? What should have been done differently if a mistake was made? Olive?" | Olive: “Wrong. Mrs Smith was busy. You should have asked the other person." Mrs Smith was busy. You should have asked the other person." | |

| Great, Olive! (give Olive 2 tokens, and give each student a chance to answer). | ||

| Pitch 5: Role play | “Now it's your turn to invite a friend to play the game. Levy, you start playing Uno with the mission c Smith." (Silently watching the game with interest - and this is a hint that you can be invited to the game). | Levi sees you watching, comes up to you with a smile and asks if you want to play. When you say yes, he returns to the game. |

| “Well done, Levi! You did four steps correctly, but you forgot the last one. I needed help getting started. You could do it this way: give me some cards or tell me you're almost done and give me the cards in the next round." | Levi repeats the role play again, doing everything right. | |

| “Great! You followed all the steps correctly." (Give Levi one token and train the rest of the students) | ||

| Step 6: Feedback and Reinforcement | “You all did great! You've learned how to invite your friends to play the game! Be sure to practice again today during recess. Count your tokens and raise your hand if you want to exchange them." |

Follow these procedures until each student has mastered the skill being taught. This method can be adapted in future lessons. For example, after one or two lessons, ask students to independently determine the skill and explain its necessity. It usually takes 3 to 6 sessions to master a new skill. This parameter will vary depending on the level of development of students.

How do you know if a child has mastered a skill? One of the signs is the correct use of it the first time during a role-playing game. Even better, try without warning: create a situation outside of the group session in which it would be appropriate to apply this skill, and observe the actions of the child. In the case of the example of learning to change the subject, talk to a student at any time during the day and suddenly pretend to be bored. See if he changes the subject. In the case of the example of learning to say "hello", when the child is playing alone, suddenly come and sit next to him to see if he says hello.

Even better, try without warning: create a situation outside of the group session in which it would be appropriate to apply this skill, and observe the actions of the child. In the case of the example of learning to change the subject, talk to a student at any time during the day and suddenly pretend to be bored. See if he changes the subject. In the case of the example of learning to say "hello", when the child is playing alone, suddenly come and sit next to him to see if he says hello.

Each student may progress at a different pace. It is important to make sure that each child gets enough practice. However, if the skill is not mastered by the student despite sufficient time to practice it, pay attention to the following points:

- Is the learning interaction procedure being applied correctly? Based on the steps listed in the article (or the links at the end of the article), you need to make a checklist and make sure that the teacher consistently completes all the steps of the procedure.

- Are there steps (skill items) that require more explicit description or detailed training? For example, the "decide if this person would be a good friend" step as part of the making friends skill would likely require a definition explaining who would make a good friend. It will also take more time to practice distinguishing between examples that correspond to the behavior of good and bad friends.

- Do students have the necessary prerequisite skills? As a rule, to get a good result, the child needs well-mastered basic speech skills (for example, using sentences in communication), and it may also require pre-learning certain steps (as in the previous example).

- Are students motivated enough to try hard? If not, pay attention to the reinforcement system. Make sure to use it consistently. Replace some rewards with more interesting ones. You can choose the most desired encouragement, which will be used only in lessons using the learning interaction method.

- The student does not apply the skill learned in the role play in real life.

Read on.

Read on.

Several steps have been added to one of the potentially successful variations of the procedure to allow generalization of the skill. That is, the child will use the learned skill not only in role play with the teacher, but also in real life situations (Kassardjian & Taubman, 2013). You can see if generalization is happening by observing the student in other settings and seeing if the skill is applied. You can also ask your child's parents if they use the skill outside of school. In order to use this option, minor changes should be made to Stage 5 and practice in real life conditions (generalization phases) should be added:

Step 5 - Role Play: Use a variety of realistic scenarios to role play. Use as many potential situations as possible, especially in which the child does not demonstrate this skill. Organize role-play with other children in such a way that they have the opportunity to interact with each other on a daily basis. For classes, you should choose materials that are usually used in the daily life of children. The role-play should be conducted in places where the skill is really needed. In the case of the example of teaching children to “invite friends to play something”, a role-play can be organized in the playground using real games.

The role-play should be conducted in places where the skill is really needed. In the case of the example of teaching children to “invite friends to play something”, a role-play can be organized in the playground using real games.

Generalization. Phase 1 - Reminder, Praise, Reward: After the skill has been mastered by students at the role-play level, situations should be created in which the new skill needs to be applied in a real life setting. For example, if this is one of the play skills, you can use recess or games during class. At the beginning of the exercise, remind the students to use the new skills. If the children are doing their actions correctly, praise and reinforce this.

Generalization. Phase 2 - Praise and Reward: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). In case of correct performance, praise them and give encouragement.

Generalization. Phase 3 - Praise: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). If performed correctly, only praise is used.

If performed correctly, only praise is used.

Generalization. Phase 4 - Autonomy: Create situations to demonstrate a skill without reminders or additional consequences. Now the students have to do everything in the natural environment on their own! Congratulations!

In addition to the method of learning interaction, there are other options for teaching social skills. And although there are many more, let's compare this method with "social stories" (Social Stories) and behavior skills training (Behavioral Skills Training).

Social stories ( Social Stories ): " Social stories" are stories, individual for each child, from which he learns information on social topics. At the moment, on the official website about this method, 10 signs are given, according to which "social history" can be considered as such. Social stories are a commonly used intervention method. Therefore, the researchers compared it with the learning interaction method to find out which one is more effective. In the first comparative study (Leaf et al., 2012), six children were taught six different skills, three skills using the learning interaction method and three others using the social stories method. According to the results obtained, using the learning interaction method, children mastered 18 skills out of 18 that they were taught. At the same time, students mastered only 4 of the 18 skills that they were taught with the help of "social stories". Although the comparison was made for applying both methods through individual learning, it was also replicated in a group learning setting (Kassardjian et al., 2014). In this study, the authors concluded that the learning interaction procedure was effective for all children, while the application of the "social stories" method did not lead to any improvements. Therefore, they recommended using the method of learning interaction.

Therefore, the researchers compared it with the learning interaction method to find out which one is more effective. In the first comparative study (Leaf et al., 2012), six children were taught six different skills, three skills using the learning interaction method and three others using the social stories method. According to the results obtained, using the learning interaction method, children mastered 18 skills out of 18 that they were taught. At the same time, students mastered only 4 of the 18 skills that they were taught with the help of "social stories". Although the comparison was made for applying both methods through individual learning, it was also replicated in a group learning setting (Kassardjian et al., 2014). In this study, the authors concluded that the learning interaction procedure was effective for all children, while the application of the "social stories" method did not lead to any improvements. Therefore, they recommended using the method of learning interaction.

Behavioral Skills Training Behavioral Skills Behavior skills training has four components: instruction, skill demonstration, skill practice, and feedback. The main difference between the two methods is that the BST does not provide an explanation for the need to apply the skill. Another difference: in the case of learning interaction method, both correct and incorrect skill models are often shown in order to develop discernment skill. This stage implementation has been called Cool/Not Cool and has been shown to be effective on its own (Au et al., 2016). In the case of BST, only the correct response model is shown. After reviewing studies on behavioral skills training and learning interactions involving people with autism (Leaf et al., 2015), the authors of the article concluded that both methods have a sufficient evidence base and are effective.

If you are going to use the learning interaction method for teaching social skills, I recommend that you read the study guide with a detailed curriculum “Connected! Learning programs. Socialization of People with Autism Using Applied Behavioral Analysis” (Taubman M., Leaf R., MakEken J., edition in Russian: IP Tolkachev, 2018). The articles I referenced in this paper also provide examples of how the learning interaction method can be applied.

Socialization of People with Autism Using Applied Behavioral Analysis” (Taubman M., Leaf R., MakEken J., edition in Russian: IP Tolkachev, 2018). The articles I referenced in this paper also provide examples of how the learning interaction method can be applied.

References:

- Au, A., Mountjoy, T., Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., Taubman, M., McEachin, J., & Tsuji, K. (2016). Teaching social behavior to individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder using the cool versus not cool procedure in a small group instructional format. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 41(2), 115–124. doi:10.3109/13668250.2016.1149799

- Bondy, A., & Weiss, M. J. (2013). Teaching social skills to people with autism: Best practices in individualizing interventions (1st ed.). Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

- Online download link for some chapters: https://pecsusa.com/downloadable-books/

- Kassardjian, A., Leaf, J. B., Ravid, D.

, Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Dale, S., … Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L. (2014). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: A replication study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2329–2340. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2103-0

, Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Dale, S., … Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L. (2014). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: A replication study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2329–2340. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2103-0 - Kassardjian, A., & Taubman, M. (2013). Utilizing teaching interactions to facilitate social skills in the natural environment. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48(2), 245–257.

- Leaf, J. B., Dotson, W. H., Oppeneheim, M. L., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). The effectiveness of a group teaching interaction procedure for teaching social skills to young children with a pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 186–198. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.003

- Leaf, J. B., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Call, N. A., Sheldon, J. B., Sherman, J. A., Taubman, M., ... Leaf, R. (2012). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281 - Leaf, J. B., Taubman, M., Bloomfield, S., Palos-Rafuse, L., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Oppenheim, M. L. (2009). Increasing social skills and pro-social behavior for three children diagnosed with autism through the use of a teaching package. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.07.003

- Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., … Pentz, T. G. (2015). The Teaching Interaction Procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. doi:10.1007/s40489-015-0060-y

- Taubman, M. T., Leaf, R. B., McEachin, J., & Driscoll, M. (2011). Crafting connections: Contemporary applied behavior analysis for enriching the social lives of persons with autism spectrum disorder.

DRL Books.

DRL Books. - Tullis, C., & Gallagher, P. (2016). Effects of a group teaching interaction procedure on the social skills of students with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51(4), 421–433.

- Citation for this article: Stoeckley, C. (2020). Clinical corner: What is a good way to teach social skills in a group? Science in Autism Treatment, 17(2).

Source: Link to the original article

Translators - Galina Chernobay, Yulia Tomilova.

We are in the social. networks

Social skills training and how it can help you • BUOM

September 1, 2021

Social skills are essential in everyday life. As people excel at social interaction, developing your social skills can equip you with the tools you need to become more socially competent and interact effectively with family, friends, and colleagues.

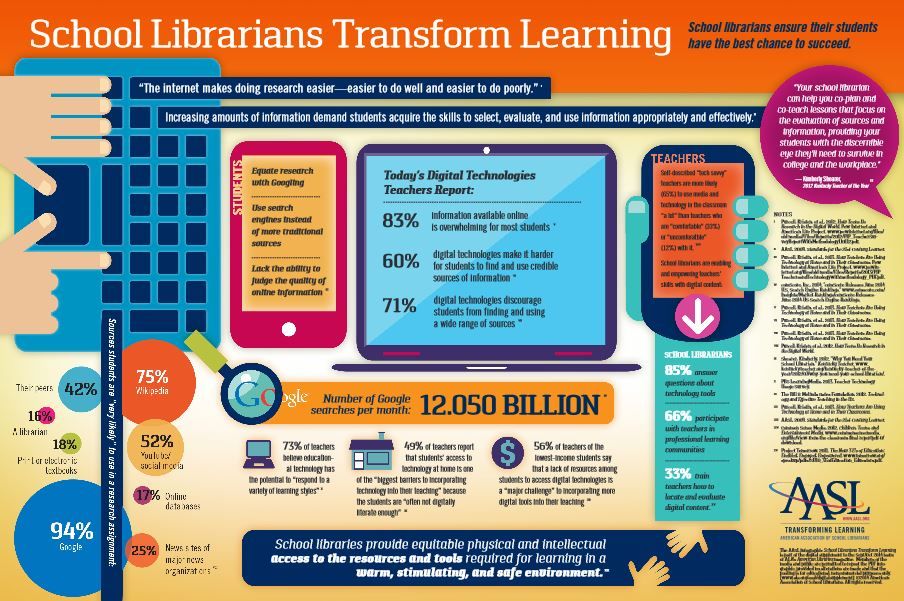

In this article, we'll talk about Social Skills Training (SST) and how to apply techniques to improve your social skills, as well as give examples of improved skills and other benefits you can expect from raising your emotional IQ.

What is social skills training?

Social skills training, or SST, is a form of behavioral therapy that is designed to help people who have different levels of problems with other people to become more socially competent. Teachers and therapists usually provide social skills training in an individual or group setting.

Windows apps, mobile apps, games - EVERYTHING FOR FREE, in our closed telegram channel - Subscribe :)

How social skills training is done

In most cases, social skills training follows a similar implementation structure with targeted steps and methods that can improve a person's social skills. Here are some ways that therapists or trainers implement social skills training:

-

Identify the problem. The trainer or therapist has a thorough discussion with the trainee to determine the underlying social problem. For example, during the discussion, the therapist may discover that the trainee has a social fear of large crowds.

Once they discover a problem, they can develop a plan to overcome it.

Once they discover a problem, they can develop a plan to overcome it. -

Set goals. A therapist or coach will help you set your overall goal and the specific goals you want to achieve with CCT. For example, a common goal might be to feel comfortable interacting with people in your workplace. A small goal might be to learn how to properly greet someone.

-

Model. Before the therapist can expect you to develop a skill, he must model that skill for you. This way you can see what you need to do before you try to do it yourself.

-

Behavioral rehearsal. Behavioral rehearsal or role play is an important aspect of SST. It involves practicing skills in a simulated situation before applying them to a real social situation.

-

Corrective feedback. Your therapist will provide feedback during your workout so that you can correct a particular skill or behavior and practice further. This is an inspiring technique that helps you develop skills in an area where you may not yet be strong.

-

Positive reinforcement. The therapist may offer some form of positive reinforcement to reward improvement in social skills.

-

Homework. Therapy usually only lasts about an hour in each session, so you will most likely get exercise and work to practice certain social skills on your own at home. The therapist or coach will probably want to know how your homework went the next time you meet.

Short training is usually sufficient and may need to be repeated as needed. Sometimes social skills training reveals other underlying issues that may require additional therapies in combination with social skills training.

Skills that can be improved with social skills training

There are many social skills that you can improve with social skills training, including:

-

Listening is an important tool that should be developed and used in various social situations of life. Listening helps build trust, resolve conflicts, and improve relationships.

-

Empathy is a key skill that allows you to form social bonds. Empathy is an important skill that SST can improve through role play. This allows the trainee to think about the emotions of other people they may be interacting with and imagine themselves in the same situation. Understanding someone else's situation, perceptions and feelings, and the ability to convey that understanding in response are essential to the role of a leader.

-

Confidence can be developed with SST. Those who lack social skills are often either too aggressive or too submissive. When an intern learns to assert himself, he creates healthy boundaries that command respect without upsetting others or getting upset.

-

Non-verbal communication refers to body language, including eye contact and gestures. Appropriate non-verbal communication skills can be beneficial both in your personal life and at work.

-

Verbal communication is the basis for building relationships.

When you learn to talk about yourself and other topics, others are likely to be more understanding and willing to communicate. Knowing how to better navigate conversations will help you understand those around you.

When you learn to talk about yourself and other topics, others are likely to be more understanding and willing to communicate. Knowing how to better navigate conversations will help you understand those around you. -

Self-control can be improved with SST as a coach or therapist helps you control your emotions, thoughts or feelings in relation to social situations. This can reduce your impulsive actions or emotional outbursts and help you deal with frustration effectively. Stress and anxiety about social situations disappear when you feel like you're in control.

Benefits of social skills training

SST primarily benefits those with certain mental, psychological or developmental disabilities. However, those looking to improve their social confidence and social skills may also benefit. Here are some of the benefits a trainee can get from learning social skills:

-

Develops appropriate responses in various social situations.

-

Raises self-esteem.