Teaching a child empathy

How to Help Your Child Develop Empathy

Yes, you can help your child be more empathetic! Try these practical tips to help infants and toddlers develop empathy and understand that others have different thoughts and feelings than they do.

Empathy is the ability to imagine how someone else is feeling in a particular situation and respond with care. This is a very complex skill to develop. Being able to empathize with another person means that a child:

- Understands that he is a separate individual, his own person;

- Understands that others can have different thoughts and feelings than he has;

- Recognizes the common feelings that most people experience—happiness, surprise, anger, disappointment, sadness, etc.;

- Is able to look at a particular situation (such as watching a peer saying good-bye to a parent at child care) and imagine how he—and therefore his friend—might feel in this moment; and

- Can imagine what response might be appropriate or comforting in that particular situation—such as offering his friend a favorite toy or teddy bear to comfort her.

Milestones in Empathy

Understanding and showing empathy is the result of many social-emotional skills that are developing in the first years of life. Some especially important milestones include:

- Establishing a secure, strong, loving relationship with you is one of the first milestones. Feeling accepted and understood by you helps your child learn how to accept and understand others as he grows.

- Around 6 months old, babies start using social referencing. This is when a baby will look to a parent or other loved one to gauge his or her reaction to a person or situation. For example, a 7-month-old looks carefully at her father as he greets a visitor to their home to see if this new person is good and safe. The parent’s response to the visitor influences how the baby responds. (This is why parents are encouraged to be upbeat and reassuring—not anxiously hover—when saying good-bye to children at child care. It sends the message that “this is a good place” and “you will be okay.

”) Social referencing, or being sensitive to a parent’s reaction in new situations, helps the babies understand the world and the people around them.

”) Social referencing, or being sensitive to a parent’s reaction in new situations, helps the babies understand the world and the people around them. - Between 18 and 24 months old, toddlers will be developing a theory of mind. This is when a toddler first realizes that, just as he has his own thoughts, feelings and goals, others have their own thoughts and ideas, and these may be different from his.

- Between 18 and 24 months, toddlers will start recognizing one’s self in a mirror. This signals that a child has a firm understanding of himself as a separate person.

What You Can Do To Help Toddlers Develop Empathy

Empathize with your child. For example, “Are you feeling scared of that dog? He is a nice dog but he is barking really loud. That can be scary. I will hold you until he walks by.”

Talk about others’ feelings. For example, “Kayla is feeling sad because you took her toy car. Please give Kayla back her car and then you choose another one to play with.”

Please give Kayla back her car and then you choose another one to play with.”

Suggest how children can show empathy. For example, “Let’s get Jason some ice for his boo-boo.”

Read stories about feelings. Some suggestions include:

- I Am Happy: A Touch and Feel Book of Feelings

- My Many Colored Days by Dr. Seuss

- How Are You Peeling by Saxton Freymann and Joost Elffers

- Feelings by Aliki

- The Feelings Book by Todd Parr

- Baby Happy Baby Sad by Leslie Patricelli

- Baby Faces by DK Publishing

- When I Am/Cuando Estoy by Gladys Rosa-Mendoza

Be a role model. When you have strong, respectful relationships and interact with others in a kind and caring way, your child learns from your example.

Use “I” messages. This type of communication models the importance of self-awareness: I don’t like it when you hit me. It hurts.

It hurts.

Validate your child’s difficult emotions. Sometimes when our child is sad, angry, or disappointed, we rush to try and fix it right away, to make the feelings go away because we want to protect him from any pain. However, these feelings are part of life and ones that children need to learn to cope with. In fact, labeling and validating difficult feelings actually helps children learn to handle them: You are really mad that I turned off the TV. I understand. You love watching your animal show. It’s okay to feel mad. When you are done being mad you can choose to help me make a yummy lunch or play in the kitchen while mommy makes our sandwiches. This type of approach also helps children learn to empathize with others who are experiencing difficult feelings.

Use pretend play. Talk with older toddlers about feelings and empathy as you play. For example, you might have your child’s stuffed hippo say that he does not want to take turns with his friend, the stuffed pony. Then ask your child: How do you think pony feels? What should we tell this silly hippo?

Then ask your child: How do you think pony feels? What should we tell this silly hippo?

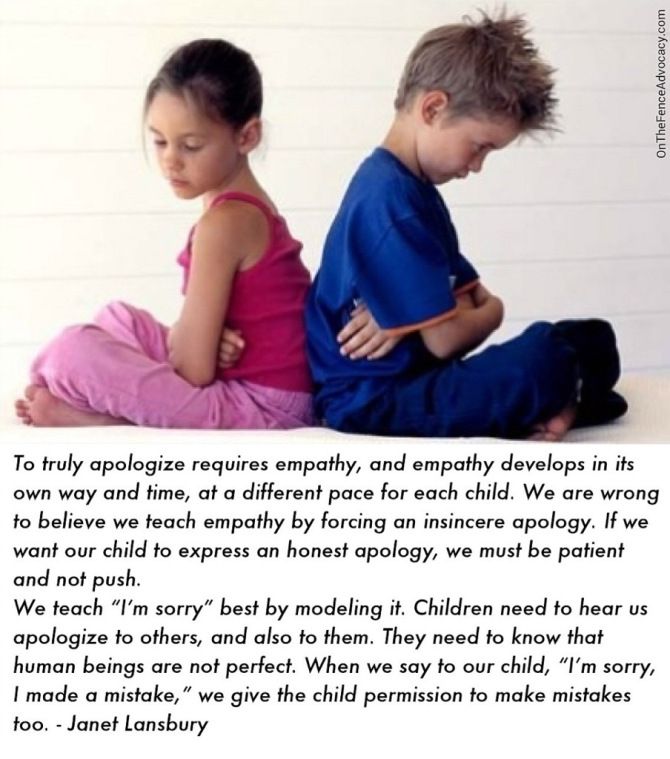

Think through the use of “I’m sorry.” We often insist that our toddlers say “I’m sorry” as a way for them to take responsibility for their actions. But many toddlers don’t fully understand what these words mean. While it may feel “right” for them to say “I’m sorry”, it doesn’t necessarily help toddlers learn empathy. A more meaningful approach can be to help children focus on the other person’s feelings: Chandra, look at Sierra—she’s very sad. She’s crying. She’s rubbing her arm where you pushed her. Let’s see if she is okay. This helps children make the connection between the action (shoving) and the reaction (a friend who is sad and crying).

Be patient. Developing empathy takes time. Your child probably won’t be a perfectly empathetic being by age three. (There are some teenagers and even adults who haven’t mastered this skill completely either!) In fact, a big and very normal part of being a toddler is focusing on me, mine, and I. Remember, empathy is a complex skill and will continue to develop across your child’s life.

Remember, empathy is a complex skill and will continue to develop across your child’s life.

How to Teach Empathy to Kids

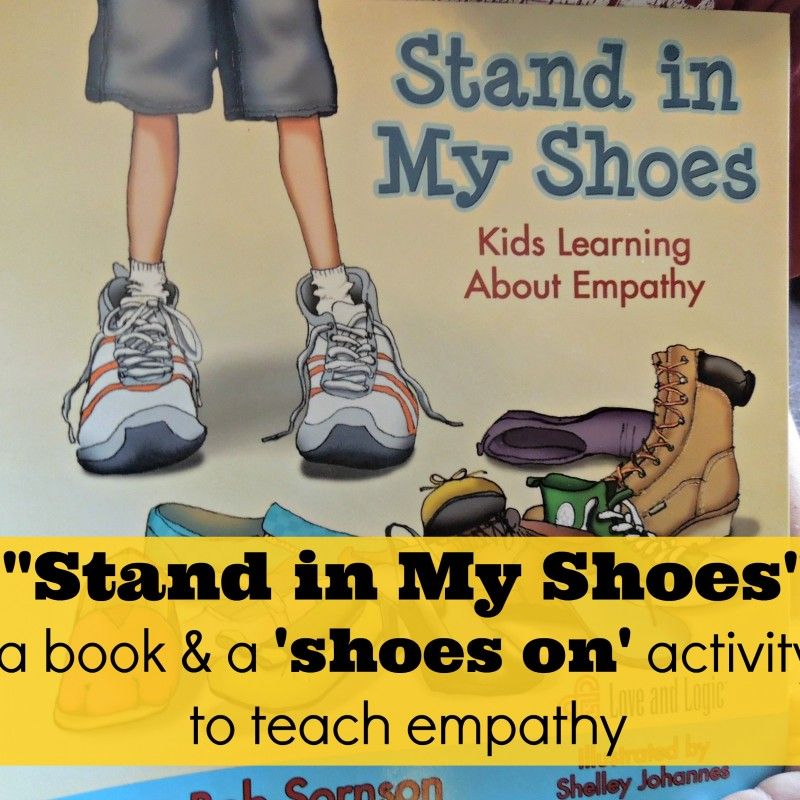

You may have heard the saying, “Before you criticize or judge someone, walk a mile in their shoes.” This quote is all about empathy. Empathy is the ability to be aware of the feelings of others and imagine what it might be like to be in their position (or in their shoes).

Empathy is a key ingredient in positive friendships and relationships. It reduces conflict and misunderstandings and leads to helping behavior, kindness, and even greater success in life in general.

And like any skill, empathy can be taught and developed in children. Because cognitive abilities and life experiences develop over time, the most effective strategies to use depend on the child’s age.

Let’s look at some key strategies for teaching empathy to children, as well as some age-by-age ideas and activities.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our FREE 21-Day Family Gratitude Challenge. Make this challenge a part of your night routine or family dinner time for the next 21 days (that's how long it takes to build a habit).

Make this challenge a part of your night routine or family dinner time for the next 21 days (that's how long it takes to build a habit).

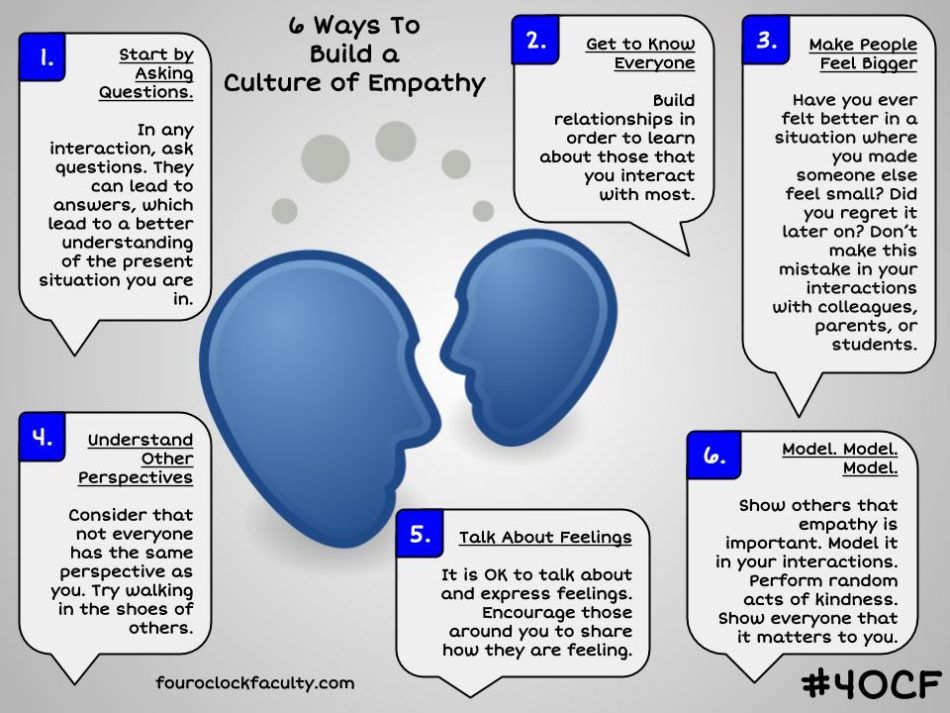

Model empathy.

Any time you want to teach a skill to a child, it’s important to model it yourself. This way, the child understands what empathy looks like, sounds like, and feels like. Plus, it’s easier to teach a skill that you’ve already mastered yourself.

Remember to model empathy even when you’re upset with or giving consequences to your child. This reinforces the idea that empathy can and should be used even when you’re feeling disappointed, hurt, or angry. The more children receive empathy, the more likely they are to offer it to others.

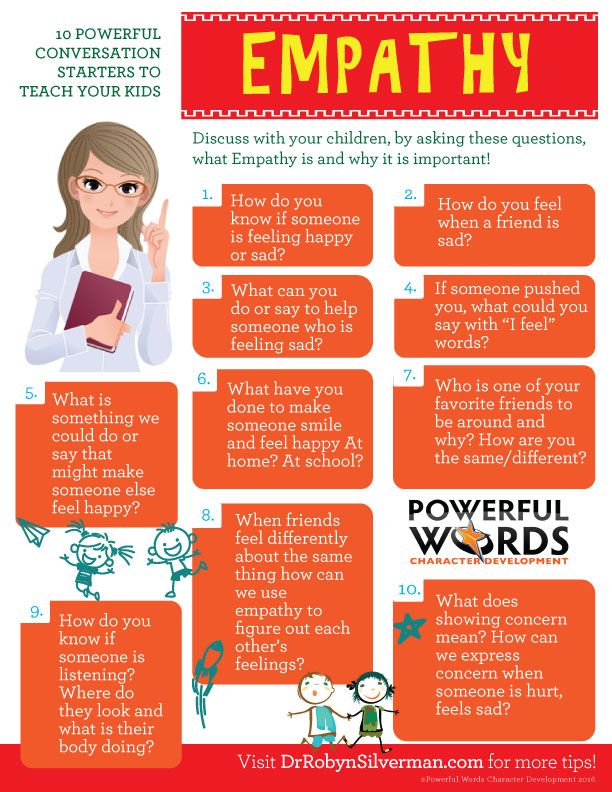

Discuss emotions.

Talk openly about emotions rather than dismissing or burying them. Let’s say your child is scared of the dark. Instead of saying, “There’s nothing to be afraid of,” explore the child’s feelings: “Are you scared of the dark? What scares you about the dark?”

If your child doesn’t like another child, don’t immediately say, “That’s wrong,” but ask why the child feels that way. This can lead to a discussion about the other child’s actions and why the child might be acting that way (e.g., They just moved to a new school and are feeling angry because they miss their old school and their friends).

This can lead to a discussion about the other child’s actions and why the child might be acting that way (e.g., They just moved to a new school and are feeling angry because they miss their old school and their friends).

Never punish a child for feeling sad or angry. Make it clear that all emotions are welcome, and learn to manage them in a healthy way through discussion and reflection.

Help out at home, in the community, or globally.

Helping others develop kindness and caring. It can also give children the opportunity to interact with people of diverse backgrounds, ages, and circumstances, making it easier to show empathy for all people.

Read through our list of activities that make a difference at home, in the community, and globally, then pick an activity or two and get started.

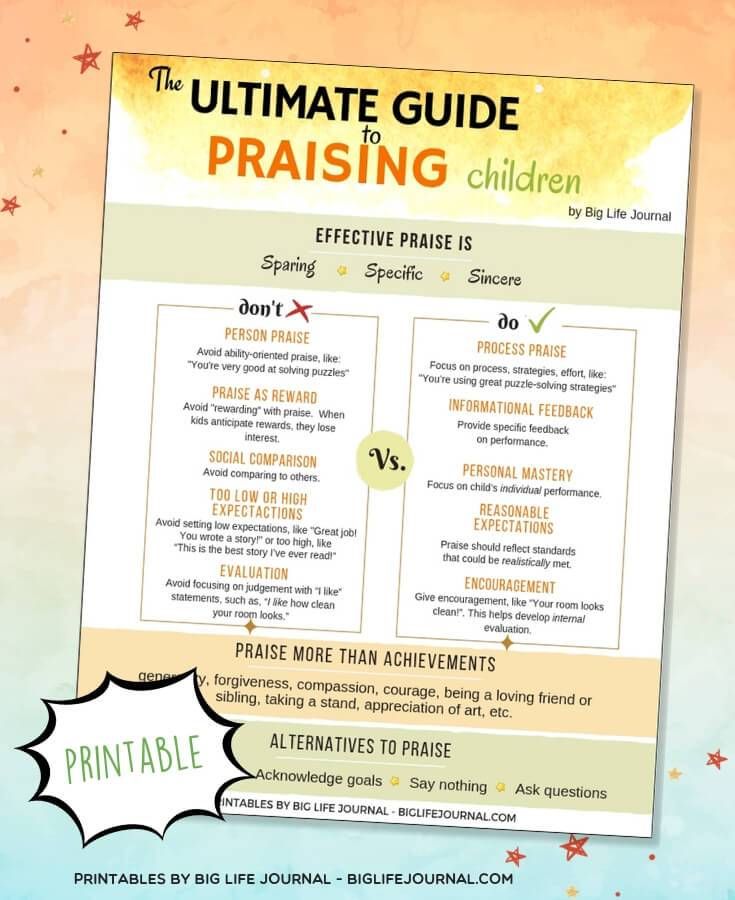

Praise empathetic behavior.

When your child shows empathy for others, praise the behavior. Focusing on and encouraging empathetic behavior encourages more of it in the future.

Make the praise specific: “You brought your sister a Band-Aid for her scraped knee so she could feel better. That was so kind and helpful!”

Age-Specific StrategiesBelow are some age-specific strategies for developing empathy in children. The age ranges below are a general guide; start with a few activities or ideas that you think will resonate with your child. Some activities introduced to younger children may be carried on into the later years.

3-5 YearsDescribe and label.

Help children recognize their emotions and the emotions of others by describing and labeling (e.g., “You seem angry,” or, “Are you feeling sad?”).

You can also promote body awareness, as young children may find it easier to identify emotions based on how it feels in their body.

For instance, you might say, “You’re clenching your fists. You stomped your feet. You seem angry.” The more children become aware of their own emotions, the more they’ll recognize and consider the emotions of others.

Read Stories.

As you read stories with your child, ask how the characters in the storybooks might be feeling.

Here’s one example from our list of 29 Books and Activities That Teach Kindness to Children:

"Listening with My Heart" by Gabi Garcia tells the story of Esperanza, who learns to be kind both to others and to herself when things don’t go as planned. You can ask your child questions like:

- How does Esperanza feel at the beginning of the story? How do Esperanza’s feelings change during the story?

- How does Bao feel at the beginning of the story? How do Bao’s feelings change?

- How was Esperanza feeling when she ran off the stage?

- If you could talk to Esperanza after she ran off the stage, what would you say to her?

- How do you think it would feel if it happened to you? What would you like someone to say to you after that experience?

- What does Esperanza do to be a good friend to herself?

- What can you do to be a good friend to yourself?

You can also read about and discuss how it feels when others are mean with the book "Chrysanthemum" by Kevin Henkes, in which Chrysanthemum loves her unique name—until others start to tease her about it.

"The Day the Crayons Quit" by Drew Daywalt is another great book for discussing emotions with young children. In this colorful story, Duncan just wants to color. Unfortunately, his crayons are on strike. Beige is always overlooked for Brown, Black only gets to make outlines, Orange and Yellow are in a standoff over which is the true color of the sun, and so on.

As Duncan tries to find a way to make all of his crayons happy, you can talk to children about how the crayons (and Duncan) are feeling. This is also a good way to teach that everyone has different needs, hopes, and dreams, and sometimes it’s hard to find ways for everyone to agree.

You can take a similar approach with just about any story that your child loves!

Make a "We Care Center”.

Dr. Becky Bailey, the founder of the SEL program Conscious Discipline, recommends making a We Care Center to teach children empathy.

The We Care Center can be as simple as a box containing Kleenex, Band-Aids, and a small stuffed animal. This provides a symbolic way for children to offer empathy to others in distress.

This provides a symbolic way for children to offer empathy to others in distress.

For instance, a young child may notice that Mom seems sad—or even that Mom is sneezing—and offer tissues.

This teaches children to be aware of others and to develop an understanding that our responses and actions can have a positive impact.

We can also model this relationship with statements like, “Our neighbors are sick. Let’s take them some soup to help them feel better!” or, “Your brother scraped his elbow. Let’s help by bringing him a Band-Aid!”

Coach social skills in the moment.

If your child snatches her brother’s toy, ask questions like, “How do you think your brother feels? How do you feel when your brother takes your toys? Look at his face. He seems sad. What could we do instead of snatching your brother’s toy?”

At this point, you could teach a more appropriate response to want a toy, such as asking for a turn, making a trade, or playing with another toy while waiting. It’s much easier for children to learn social skills when they are taught in context.

It’s much easier for children to learn social skills when they are taught in context.

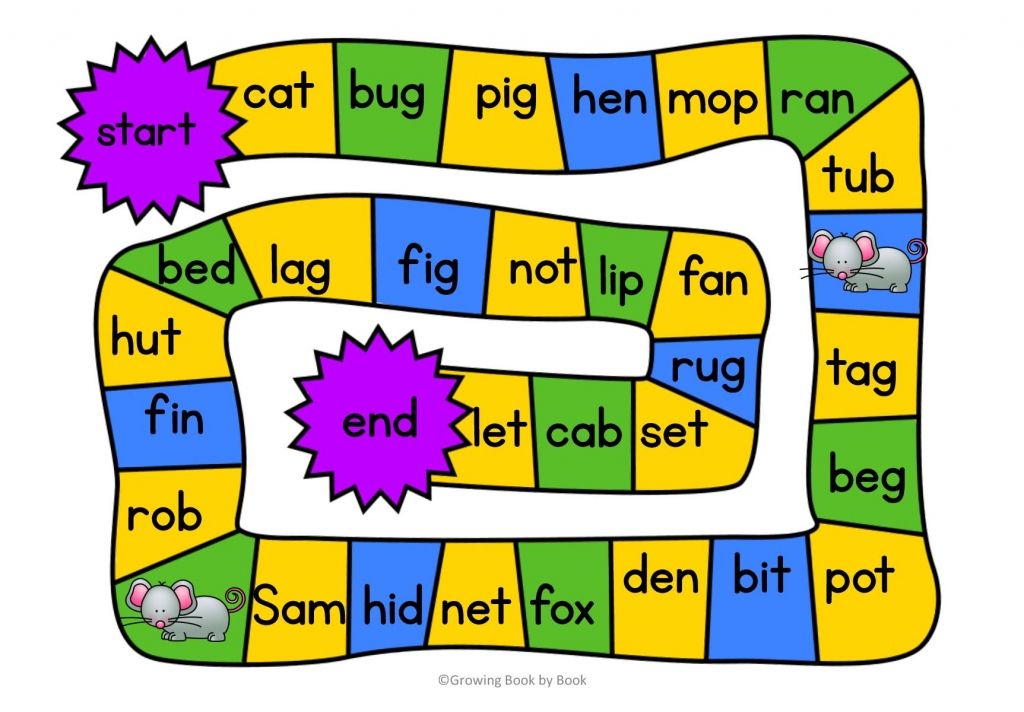

Play emotion charades.

Teaching emotions through play is an important way to develop empathy in children. Games and activities can help children learn the language to express and understand complex feelings.

To play emotion charades, take turns acting out emotions and guessing what feeling is being portrayed. After a player has guessed correctly, you can also discuss the emotion with questions like:

- When do you feel sad?

- What helps you feel better when you’re sad?

- How can we help someone else when they’re feeling sad?

Lisette at the Where Imagination Grows blog suggests a helpful variation on this game. She uses the characters from the movie Inside Out to represent different emotions.

She cuts out images of the characters and glues each character onto an index card. The performer then draws an index card from a bucket and acts out that emotion. The other children hold up the corresponding Inside Out character figurine to guess the emotion.

The other children hold up the corresponding Inside Out character figurine to guess the emotion.

Use pictures.

Visuals are another great way to help children learn. If your child seems to have trouble recognizing and/or labeling emotions, cut out pictures from magazines or print pictures from the Internet that show sad, angry, or happy faces. You can also work up to more complex emotions like scared, embarrassed, disappointed, frustrated, etc.

As you discuss how the people in the pictures are feeling, you can also ask children about times they felt the same way. Provide examples from your own life too, showing that even adults grapple with big emotions and that it’s perfectly normal.

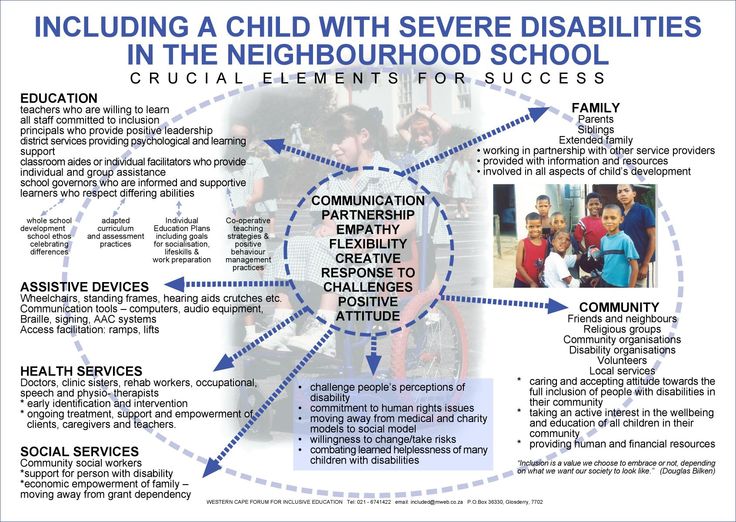

Embrace diversity.

A major component of empathy is respecting others from different backgrounds.

Give your child opportunities to play with children of different races, backgrounds, ability levels, sexes, and so on. You can also read books or watch shows featuring children who are different from your child. Help children understand and focus on what they have in common with others.

Help children understand and focus on what they have in common with others.

Observe others.

Deepen your child’s understanding of nonverbal cues by playing a game where you observe other people in a busy public place, like a park.

Note the body language of others and guess how they might be feeling. “That child’s head is down, and his shoulders are hunched like this. I think he might be feeling sad. I wonder why he feels that way?”

Teach healthy limits and boundaries.

As your children grow older, it’s important that they also understand empathy doesn’t mean taking on the problems and needs of everyone around them. It doesn’t mean always saying “yes” or dropping everything to help others.

Teach your children to understand and respect their own needs by following these 3 steps.

- Create a plan for how your child can respond in certain scenarios. If, for example, another child gives an unwanted hug, your child can say, “I don’t like that.

Please don’t touch me.” If a child calls your child a name, your child can say, “My name is ________. Call me that instead.”

Please don’t touch me.” If a child calls your child a name, your child can say, “My name is ________. Call me that instead.” - Create a list of scenarios in which it’s necessary to ask an adult for help, like a child refusing to take no for an answer or any situation that feels dangerous or uncomfortable. In addition, explain that being helpful to others should not involve breaking any rules or doing anything that your child isn’t comfortable with.

- Respect your child’s boundaries. If your child doesn’t like to be tickled or doesn’t want to be picked up and spun around, don’t push the issue. Say, “I understand. I won’t do it again.” This models the way your child should expect others to behave when he or she says “no.”

Don't forget to download our FREE 21-Day Family Gratitude Challenge and make this challenge a part of your family's routine!

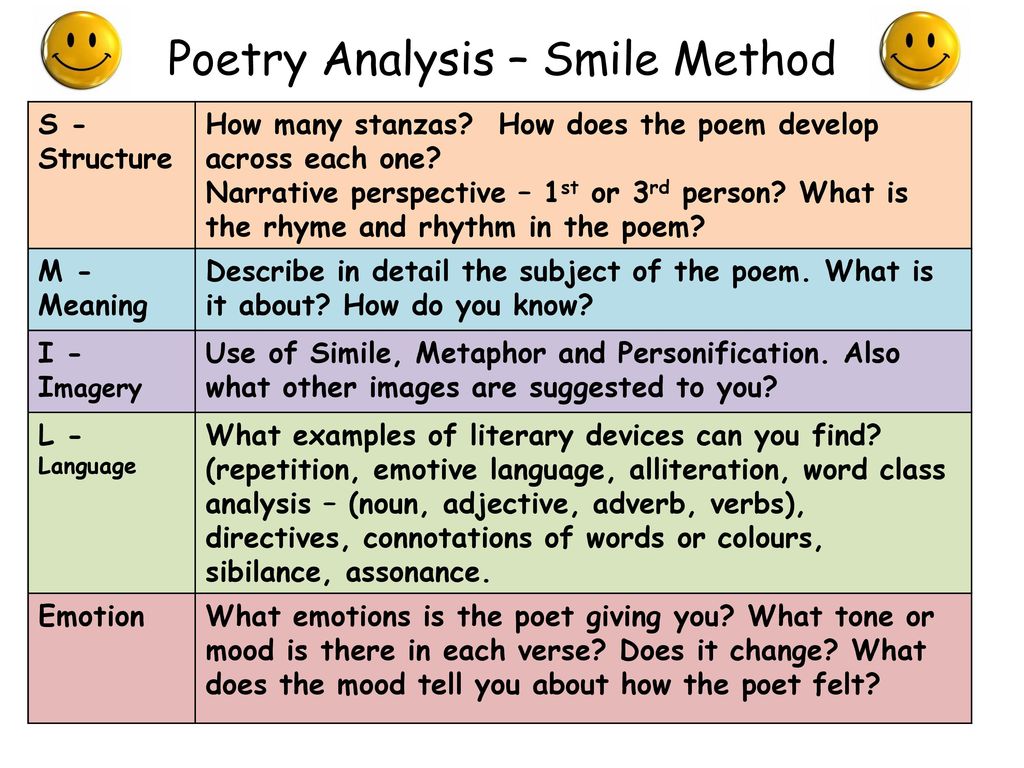

7-9 YearsEngage in high-level discussions about book characters.

Read more advanced books and engage in high-level discussions about what the characters think, believe, want, and feel. How do we know?

How do we know?

For example, read "The Invisible Boy" by Trudy Ludwig, in which a boy named Brian struggles with feeling like he is invisible. He’s never invited to parties or included in games. When a new student named Justin arrives, Brian is the first to make him feel welcome. When the boys team up on a class project, Brian finds a way to shine. The book teaches children that small acts of kindness can help kids feel included and allow them to flourish.

After reading, ask questions like:

- Why did Brian feel invisible?

- How do you think being “invisible” makes Brian feel?

- How did Brian help Justin feel welcome?

- How did Justin help Brian feel more “visible?”

- Have you ever felt left out or invisible? What would have helped you feel more included or visible?

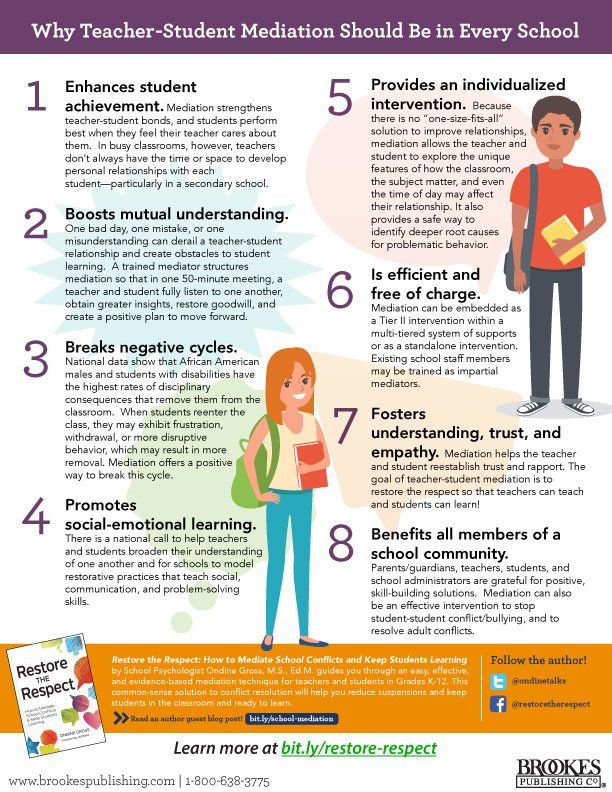

In one experimental study, 110 school kids (aged seven years) were enrolled in a reading program. Some students were randomly assigned to engage in conversations about the emotional content of the stories they read. Others were asked only to produce drawings about the stories.

Others were asked only to produce drawings about the stories.

After two months, the kids in the conversation group showed greater advances in emotion comprehension, the theory of mind, and empathy, and the positive outcomes "remained stable for six months."

You can select books to read with your children that are directly related to empathy. Alternatively, notice what your children are reading and engage them in conversations about the characters, their emotions, and what your child might think, feel, or do in similar situations.

Loving-kindness and compassion meditation.

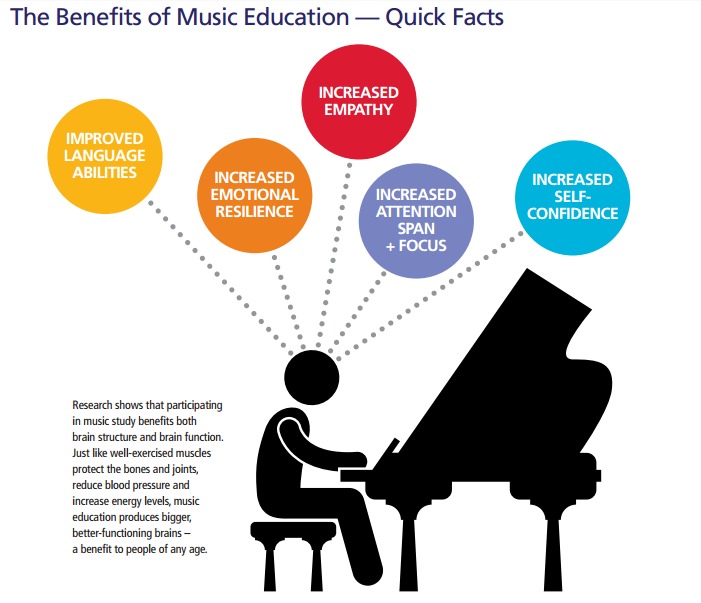

Studies show that as little as two weeks of training in compassion and kindness meditations can lead to changes in brain chemistry that are linked to an increase in positive social behaviors, including empathy. These meditations also lead to increased positive emotions and social connectedness, in addition to improved health.

Loving-kindness meditation involves thinking of loved ones and sending them positive thoughts. Later, your child can expand her positive thoughts to more neutral people in her life as well.

Later, your child can expand her positive thoughts to more neutral people in her life as well.

The four traditional phrases for this meditation are, “May you feel safe. May you feel happy. May you feel healthy. May you live with ease.” The exact wording you and your child use aren’t important; it’s about generating feelings of kindness and warmth.

With compassion training, children visualize experiences in which they felt sad or upset, then relate to these experiences with warmth and care. They then repeat the exercise with other people, starting with close loved ones, followed by a difficult person, and finally extending compassion to humanity in general.

Engage in cooperative board games or cooperative construction.

Research shows that successful experiences with cooperation encourage us to cooperate more in the future. Collaborating with others can encourage children to build positive relationships and to be open to developing more positive relationships in the future.

These experiences also involve discussions and debate, teaching children to consider other perspectives.

Ideas for cooperative board games or cooperative construction include:

- Play with Legos, working together to build something specific

- Race to the Treasure! (a board game in which children collaborate to build a path and beat an ogre to the treasure)

- Outfoxed! (a cooperative whodunit game)

- Stone Soup (an award-winning cooperative matching game)

- The Secret Door (a mystery board game in which children ages 5+ work together to solve the mystery behind the secret door)

Sign up for acting classes.

If your child is interested, get him involved in theater or acting classes. Stepping into the role of another person is a great way to build empathy, just as playing pretend helps young children develop understanding and compassion for others.

Create empathy maps.

Empathy maps include four sections: Feel, Think, Say, and Do. Choose an emotion, then brainstorm what you might say, think, and do when you feel that way.

Choose an emotion, then brainstorm what you might say, think, and do when you feel that way.

For example: “When I feel worried, I might think I’m making a lot of mistakes or that something bad is going to happen. I say, ‘I’m sorry’ too much or, ‘I can’t do this.’ Sometimes when I’m worried, I do nothing at all. Something helpful that I can do is to take deep breaths and remind myself that everything will be okay.”

If it comes up, you can highlight the fact that what we say or do is sometimes the opposite of what we’re really feeling. You can discuss why that is and how we can relate that to showing empathy and understanding for others.

Ages 12+Discuss current events.

Learn about current events and develop empathy by reading newspapers, news magazines, or watching the news together. Alternatively, you can do this activity when your child mentions a current event to you.

Ask questions like:

- How might the people involved in this situation be feeling?

- How would you feel in a similar situation?

- Is there anything we can do to help?

Encourage your child to choose volunteer work.

Encourage your child to choose volunteer work that he or she is passionate about. As children get older, they can take a more direct role in helping the community or society in general. They may even want to start their own projects or charitable organizations to solve a problem they feel strongly about.

It’s important for kids to explore the world beyond themselves. Our Big Life Journal - Teen Edition includes a section where older kids can write down and map out ways they can make a difference in the world. They can take these passions and turn them into opportunities to serve their communities.

Walk the line.

This activity is perfect for classrooms, summer camps, or other places with a large group of older children/teens. “Walk the Line” was demonstrated in the movie Freedom Writers.

Put a line of tape in the middle of the group, with students facing each side’s line. Read a series of statements. If the statement is true for the student, they go stand on the line.

This could include statements like “I’ve lost a family member,” “I’ve been bullied at school,” and so on. Students can also help create the prompts.

The activity shows the struggles they have in common and helps them understand what their peers experience and feel. At the end of the activity, students return to their seats to reflect through writing or discussion.

One option is to have students write a letter (that they can deliver or keep to themselves) to a student who walked to the line on one of the same prompts they moved on, sharing more about this experience or offering words of encouragement.

Empathy can be taught and developed over time, and it will give your child a foundation on which to build sound judgment, success, and positive and healthy relationships throughout their life. Choose one or two activities from this list and get started!

Looking for additional resources to help teach your child about empathy? The Big Life Journal helps children develop strong Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) and growth mindset skills through inspiring stories, colorful illustrations, and engaging guided activities.

How to develop empathy in a child, what is empathy and how important is empathy for children

What is empathy

Empathy is the ability to understand the feelings of another person. Its manifestation does not mean at all that the empath will certainly help another in trouble. Empathy is most often about the level of understanding of feelings and emotions, rather than specific actions.

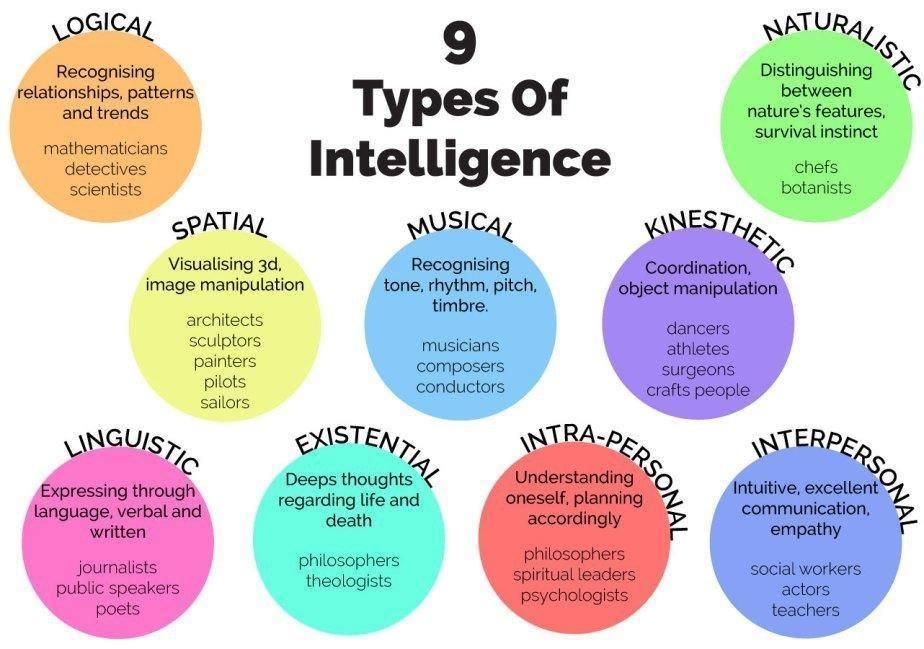

Psychologists distinguish three types of empathy.

Cognitive empathy. We make sense of other people's feelings through data analysis and processing: for example, we draw parallels with fiction and cinema. The character in The Catcher in the Rye felt like this in such and such a situation, and I sympathize with my friend, because I understand that he now feels the same way.

Emotional empathy. We make sense of the feelings of others by associating them with our experience. For example, we understand that a person is feeling bad now, because they themselves were in a similar situation.

Effective empathy. We not only comprehend the feelings of others, but also move on to actions: for example, we offer a person specific help.

How to understand if a child has enough empathy

Empathy is not an innate ability, but a consequence of upbringing. Its foundations must be laid at an early age.

Even then, parents can observe the difference between a child prone to empathy and a child to whom empathy is alien: the former is able to pity someone and sympathize, while the latter will remain indifferent or even gloat.

By age 3-4, children should be able to respond to other people's feelings and show empathy. If a five-year-old does not have enough empathy - for example, laughs when a peer is hurt - this is an alarm signal for parents. Here are a few ways to tell if a child has empathy.

<

The child picks up the emotions of others and reacts correctly. For example, it reads when mom came home from work in a bad mood - even if mom does not say anything - and asks: “Mom, did something happen?”, “Mom, are you sad?”.

The child is not selfish . For example, he can make a compromise when playing on the playground: let the younger kid swing first on the swing.

The child empathizes with characters in fairy tales and cartoons. If a son or daughter cries while watching Monsters, Inc. or reading the children's novel No Family, this means that he has a high level of empathy.

Source: freepik.com / @freepic-dillerHow to purposefully develop empathy

If you are afraid that your child lacks emotional responsiveness and the ability to empathize with others, this skill can and should be developed.

1. Pay attention to other people's feelings

Invite your child to feel sorry for someone who is feeling bad right now. For example, on the playground, a boy fell down a hill and was crying. You can approach and feel sorry for him, offer help. If you see that the boy is already being helped, you can limit yourself to a discussion with the child: “Look, you have fallen. Poor guy, he's in pain. Well, nothing, his grandmother will regret it, and everything will pass. If the child offended someone, you should not just demand “apologize immediately”, but describe in detail the feelings of the one who was offended.

Poor guy, he's in pain. Well, nothing, his grandmother will regret it, and everything will pass. If the child offended someone, you should not just demand “apologize immediately”, but describe in detail the feelings of the one who was offended.

It is not necessary to look for live situations. Focus on someone's feelings when you play with your child. For example: “My doll bought a balloon, and it accidentally flew into the sky. She is sad." Come up with situations and discuss with the child - how does the hero feel? What is it like for him? Can we help?

2. Be an example

The upbringing and education of children is built on the repetition of the actions and reactions of a teaching, significant adult. Don't hide your feelings when you feel bad - talk openly about them.

Show empathy towards the child, even if his problems seem far-fetched - for example, in the sandbox he did not share a bucket with someone. If you are sensitive to the emotional state of the child, he will adopt it. Important: never tell your child how he “should” feel right now.

Important: never tell your child how he “should” feel right now.

One must be able to cope with even the most difficult emotional state of a son or daughter, regardless of their age. Don't laugh or make fun of your child's negative emotions. Such emotions are an opportunity for rapprochement. As a rule, children who could easily trust adults in childhood felt secure, received support and affection at the right moments - there are no problems with empathy.

3. Socialize

Social connections are important at any age - this is how a child learns to get along with others. The more contact a child has with peers, the easier it is for him to learn empathy. Team games accelerate the emotional and cognitive development of the child. Interacting with others, the child receives a lot of empathic experiences, learns to put himself in the place of others, to help and find help in difficult times.

You can offer your child to organize joint activities with peers. There are games that specifically develop empathy.

"Transmission of feelings". An adult presenter chooses a child and suggests in his ear what mood to think of. The child chain conveys this mood - with the help of facial expressions, gestures, touches. Each next child guesses what mood they are talking about and thinks out how to pass it on to the next in the chain. When the circle closes, you need to discuss what kind of mood was intended.

Quiet conversation. An adult facilitator whispers a phrase into the child's ear. All children sit in a circle. The task of the child is to non-verbally say this phrase to the others. Children guess what exactly this phrase is.

Heroes' emotions. An adult leader reads a story or a fairy tale to the children. Children are given symbolic cards with images of different moods in advance. In the process of reading, the children correlate the cards with the emotional state of the hero of the work and explain their choice.

4. Discuss emotions

Ask the child how he feels at the moment. But the younger the child, the more difficult it is for him to recognize his emotions. Children do not know how to determine whether they are sad now or they are angry - as long as their parents do not teach them to distinguish one from the other.

Speak out the emotions of your son or daughter: “You are now angry because...”, “You are upset because of...”, “So-and-so offended you...”. When a child recognizes his own emotions, it is easier to understand others.

When talking about your own emotions, use the "I-statement": "I feel like this", "I feel like this right now." Do not shift the responsibility for your emotions to the child: “You are such and such, you brought me!”.

<

What is the result

Empathy is the ability to understand the feelings of others. You need to educate it from childhood: set an example, pay attention to the emotional state of others, allow the child to play a lot with peers and talk about the inner world.

Foxford Home School not only teaches the school curriculum, but also develops emotional intelligence, including empathy.

The school has mentors - personal family assistants who know the answers to all questions about learning and help the child develop soft skills - the so-called "soft skills". Soft skills help to act effectively and independently in different situations. Empathy is one of the most important skills.

5 simple steps instead of forced "sorry"

How to teach your baby empathy: 5 simple steps instead of forced "sorry"© unsplash.com

Helpful Hints

Very often we force our baby to "immediately apologize", worrying about what strangers will think of us. And now the child sings "I'm sorry" and after five minutes again begins to hit his friend on the head with a scoop. Finding out how to teach kids to actually see the connection between their own behavior and the emotions of others.

Lauren Selenza

Teacher, scientist, columnist

When we say "Say you're sorry," we're teaching kids exactly what is to say . But do they really regret?

Just imagine: your five-year-old is playing with another child, suddenly an argument flares up over a toy, your child pushes someone else's child, he falls and starts to sob. What will you do? Usually, we jump up to the child with lightning and hiss: “Come on, apologize immediately!”. And that's okay.

But when it comes to children under five, things are different. They do not even really understand what it is and why it is necessary - to apologize. They don't feel that way. And we, in theory, need to teach them this.

I'm not just saying this. I had to deal with this every day. First I was a kindergarten teacher, and now I'm doing early development research for a large company. Well, besides, I was the mother of a three-year-old, so I know perfectly well how it happens. In general, I realized that instead of just saying “Come on, apologize!”, I can really explain to the child what an apology is and why it is needed.

I had to deal with this every day. First I was a kindergarten teacher, and now I'm doing early development research for a large company. Well, besides, I was the mother of a three-year-old, so I know perfectly well how it happens. In general, I realized that instead of just saying “Come on, apologize!”, I can really explain to the child what an apology is and why it is needed.

So here's what you can do:

If you walk up to your child and kneel down so that your eyes are at the level of his eyes, it will be easier for him to take in information and listen to you. When an adult hangs like a rock, it immediately seems to the child that he is being scolded, and he becomes isolated. To avoid this effect, become as small as your child and speak in a soft, low voice.

Empathy is the most important factor in understanding what "I'm sorry" really means. So, in order for a child to understand what exactly he is asking for forgiveness, he must first understand how the other person feels. Sometimes I would say things like, “Oh my God, look at his face, it's all in tears. Poor! Do you think he's doing well now?" With such phrases it is very easy to start a conversation about the feelings and emotions of another child and quickly find the right word for them (he is scared, confused, upset, and so on).

So, in order for a child to understand what exactly he is asking for forgiveness, he must first understand how the other person feels. Sometimes I would say things like, “Oh my God, look at his face, it's all in tears. Poor! Do you think he's doing well now?" With such phrases it is very easy to start a conversation about the feelings and emotions of another child and quickly find the right word for them (he is scared, confused, upset, and so on).

First, we discussed how the second baby feels, and now we need to find out why he feels the way he does. Ask something like, “Why do you think he is so upset and crying? Maybe something happened that upset him? This will help the child to understand the connection between their actions and the state of another person.

Now that the baby understands the connection between his action and the feelings of another child, help him imagine how he would feel in the place of the offended: “Imagine if you were pushed so hard? Would you be upset?" Then bring the conversation to your specific situation: “I wouldn't want someone to ever push you that hard and make you feel that bad. And I don't want anyone else to be pushed like that. I have to protect you and other children."

And I don't want anyone else to be pushed like that. I have to protect you and other children."

Instead of making me apologize, I'd rather ask if the child wants to say something to the crying baby. If a child is aware of the existence of the word "sorry", he himself will think of it before. But if it doesn't, then you can say something like, “You know, sometimes we hurt others when we don't mean to. And then we say “forgive me” so that the person offended by us feels better. And let him know that this will not happen again.” Now ask the child again if he wants to say something. Usually this is enough. The child consciously apologizes, and I tell how you can share the toy next time without a quarrel.

Afterward, try aloud to note their ability to deal with such situations. For example, you can say: “How great you play together! I am very proud that you are so calmly waiting for your turn to take this toy! I know it's not easy for you!"

It seems that all these explanations will take years, but in fact such a conversation takes a couple of minutes. A three-year-old baby is simply not able to withstand a conversation longer. So you need to be quick, concise and intelligible.

A three-year-old baby is simply not able to withstand a conversation longer. So you need to be quick, concise and intelligible.

It is clear that from one time to the child may not reach. Just try to explain again and again. By the way, to parents who are outraged that you do not make your child apologize right now, you can also talk about this system. And over time, you will understand that even the youngest children are able to understand this concept, and you will see how their behavior will change.

By using these five simple steps, we can help our children develop empathy and learn to apologize with meaning. This way, they will really think about their actions and their consequences, instead of just straining "I'm sorry."

- emotional intellect

- hysterics

- empathy

- upbringing

- 6-10 years old

- 3-6 years old

We will send you important and best materials in a week.