What is phonological knowledge

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: In Depth

Learn more about the development of phonological awareness skills in young children, why it's so important to teach this skill, and the value of multisensory instruction. You'll also find sample lessons for teaching phonological awareness.

In this section

The development of phonological awareness skills

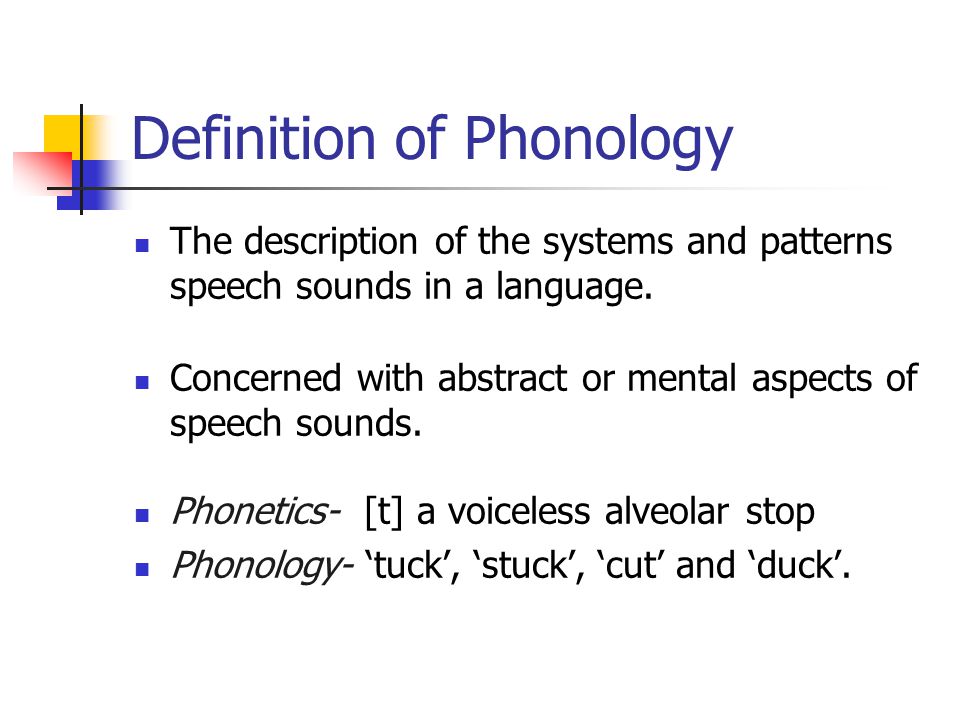

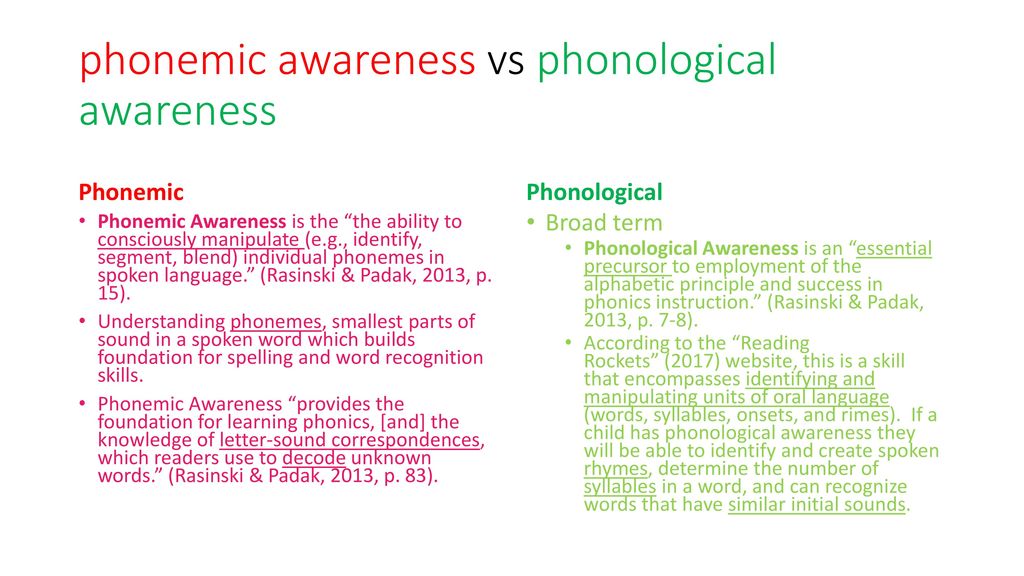

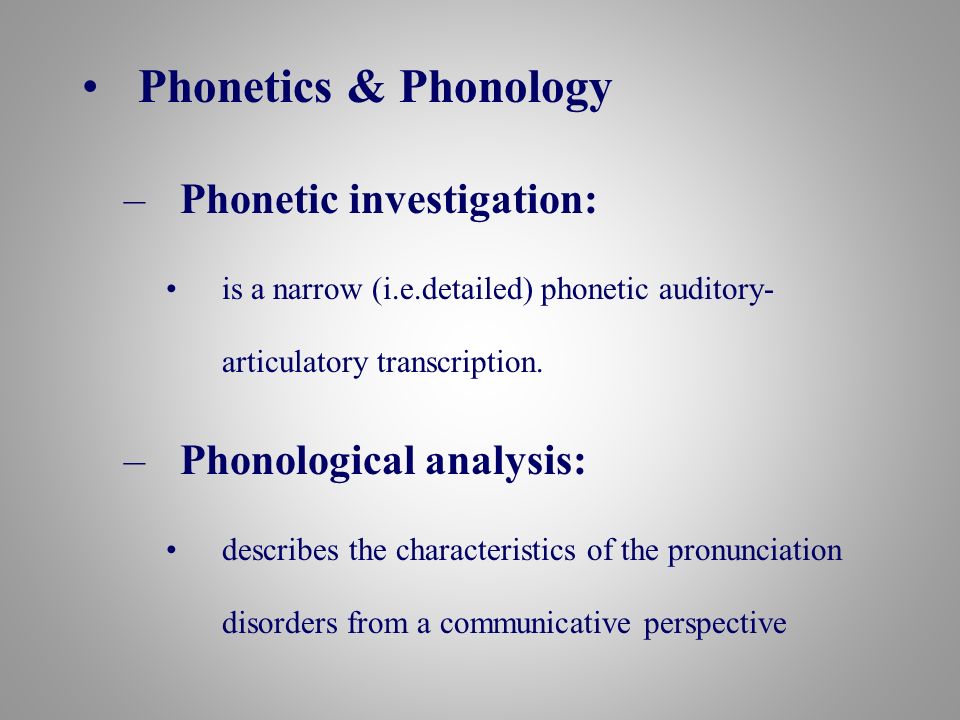

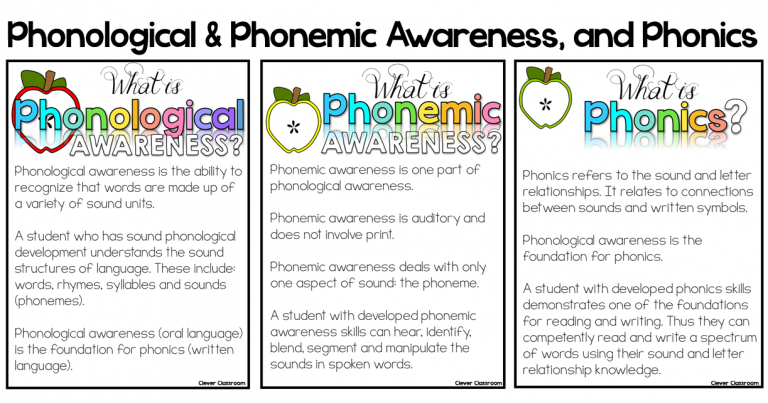

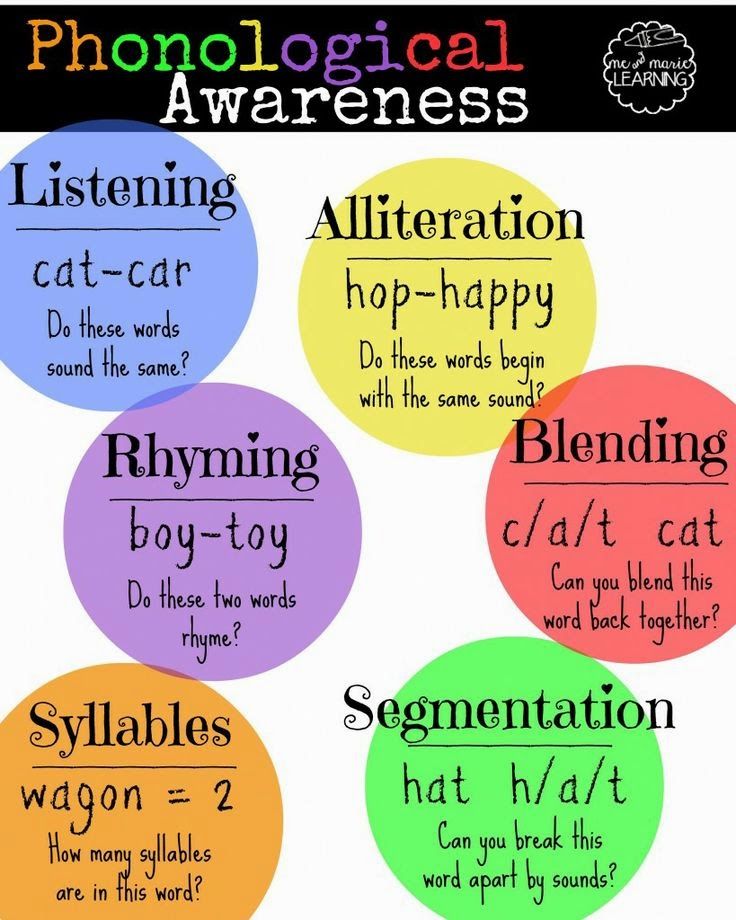

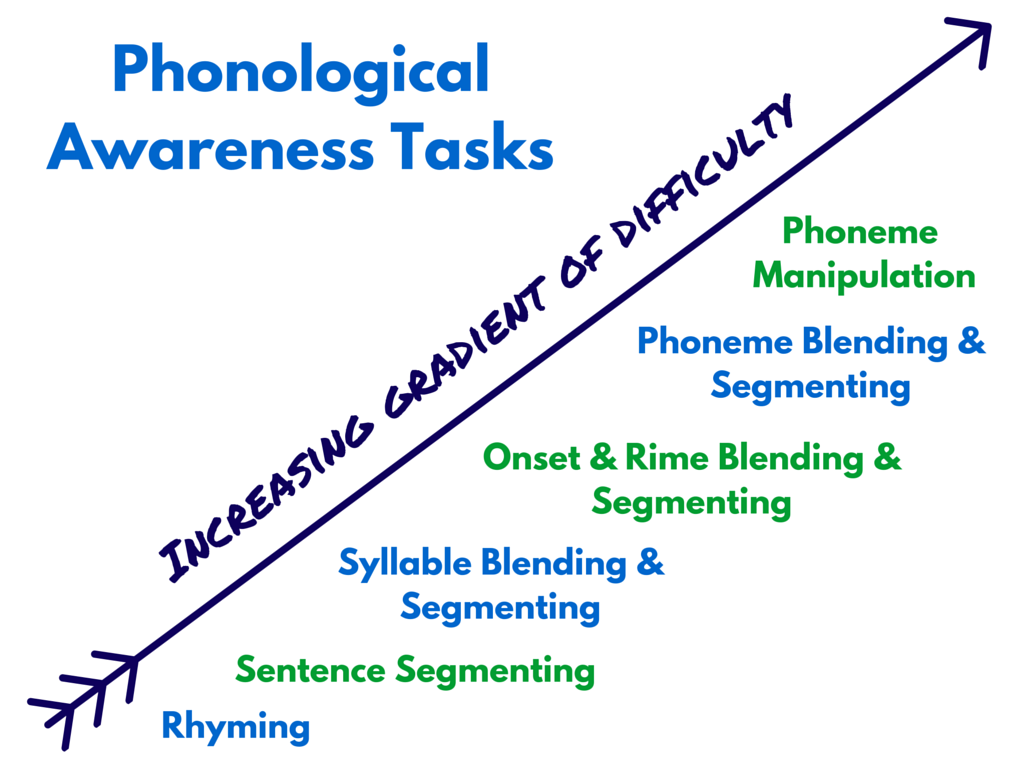

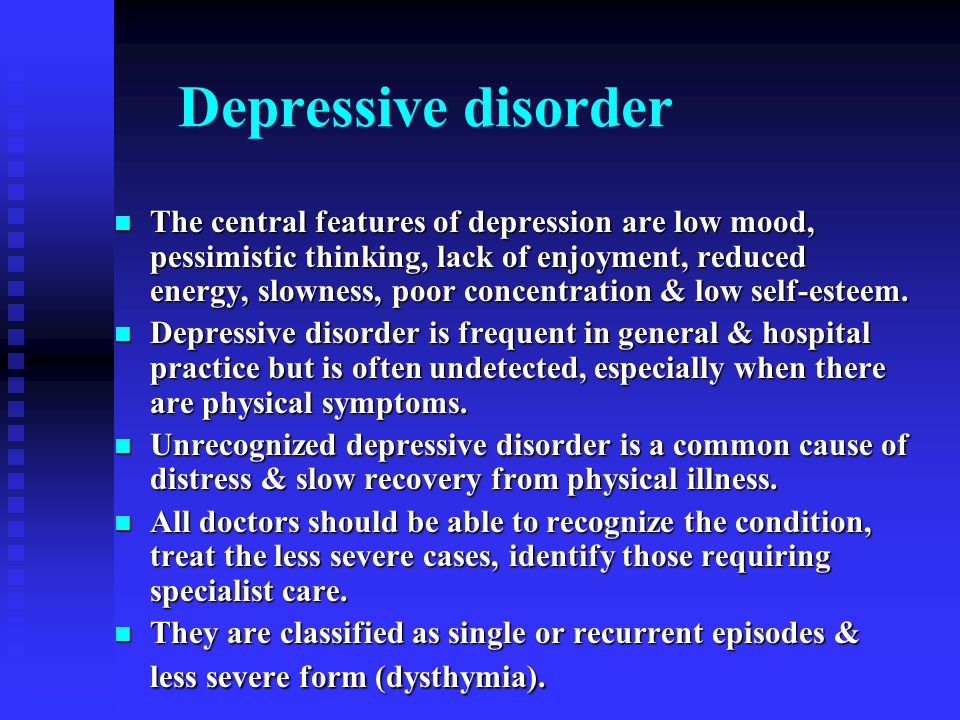

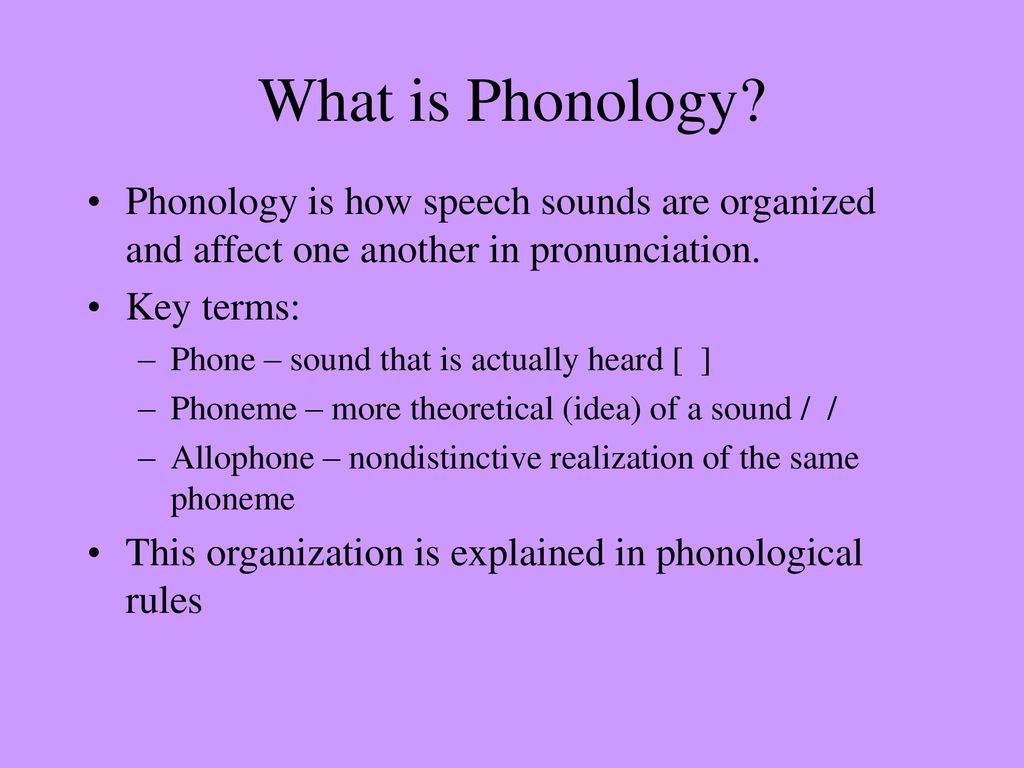

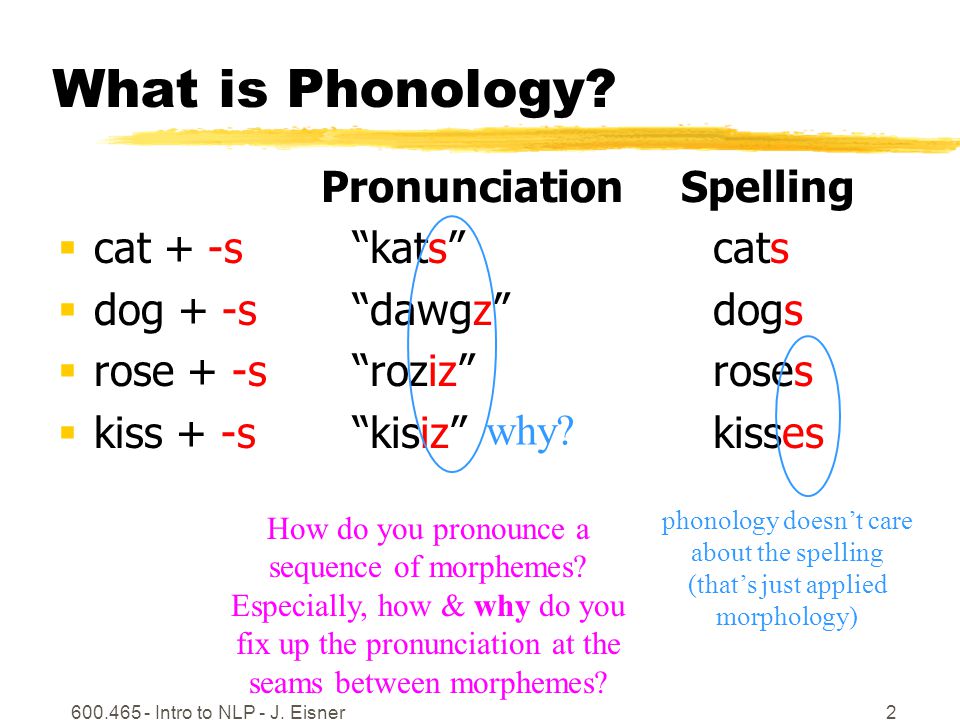

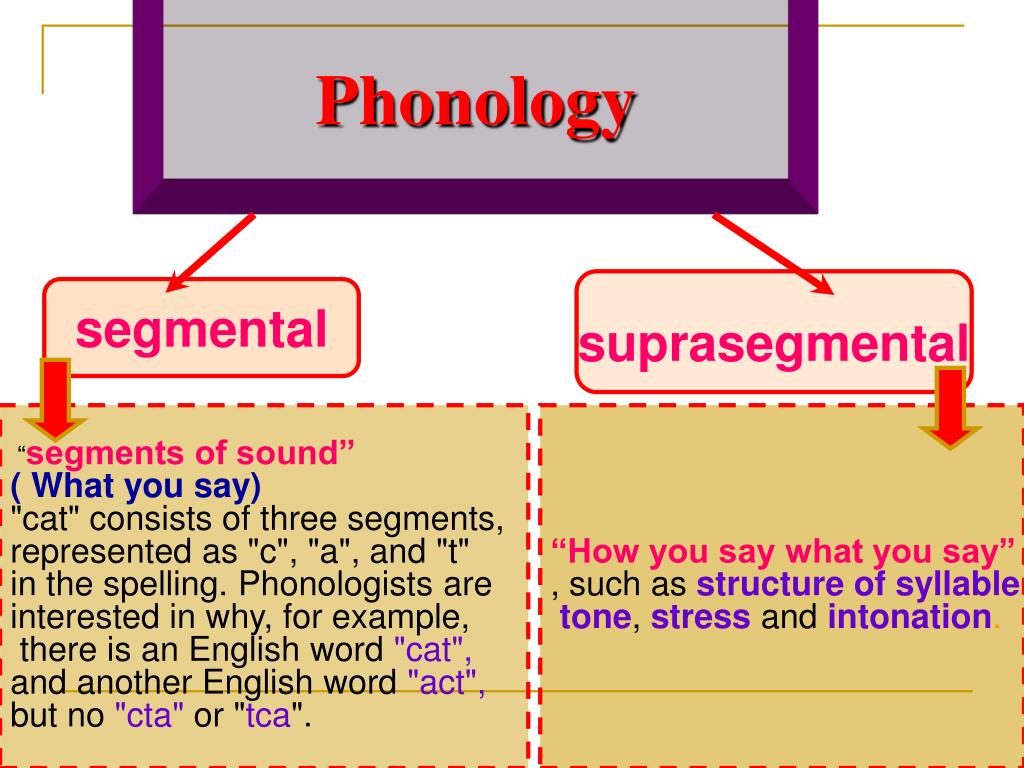

Phonological awareness refers to a global awareness of, and ability to manipulate, the sound structures of speech.

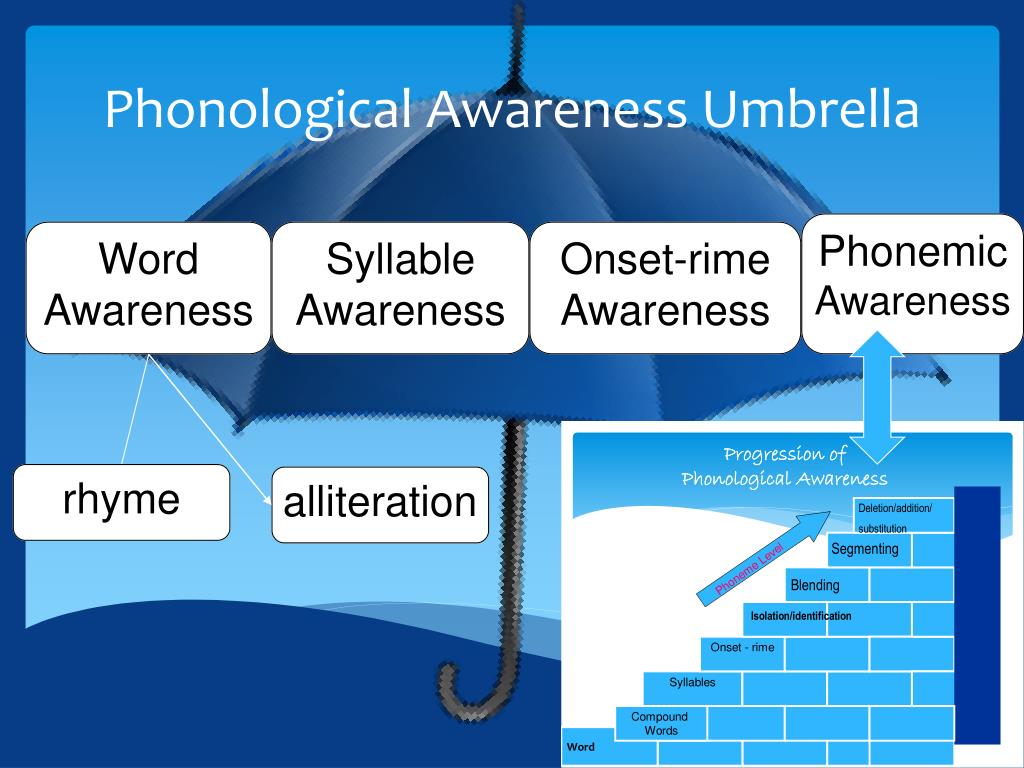

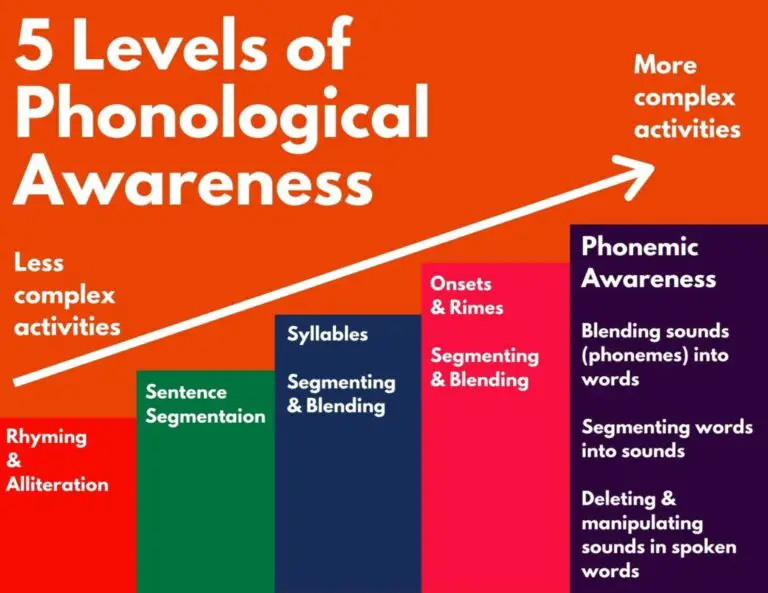

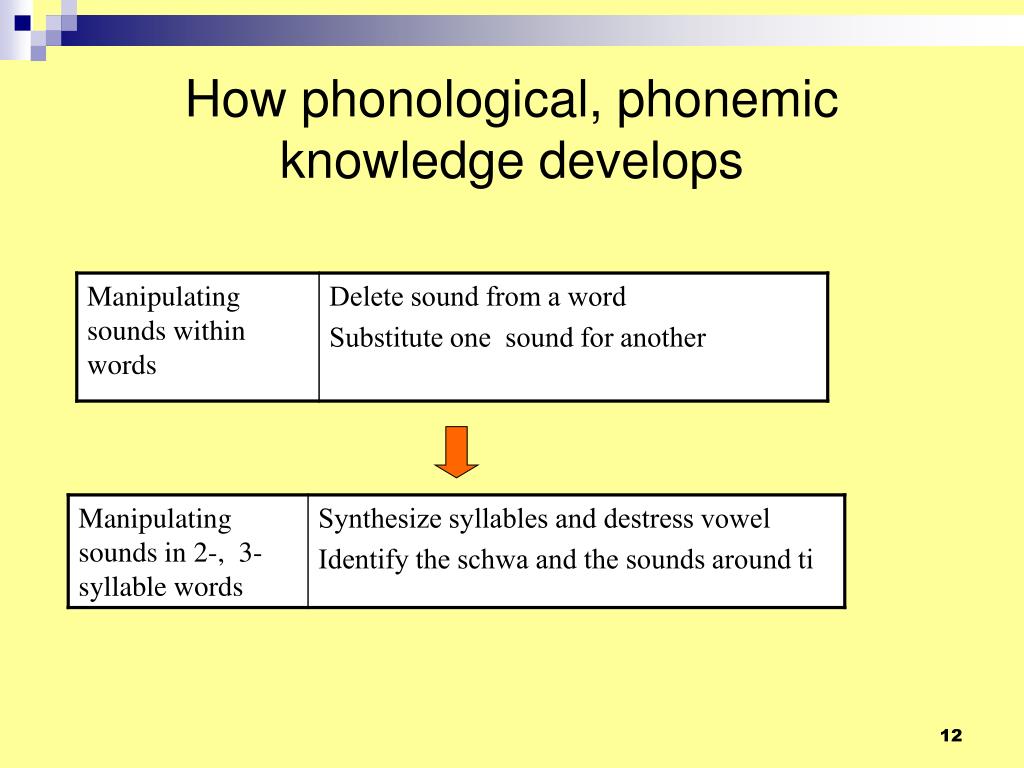

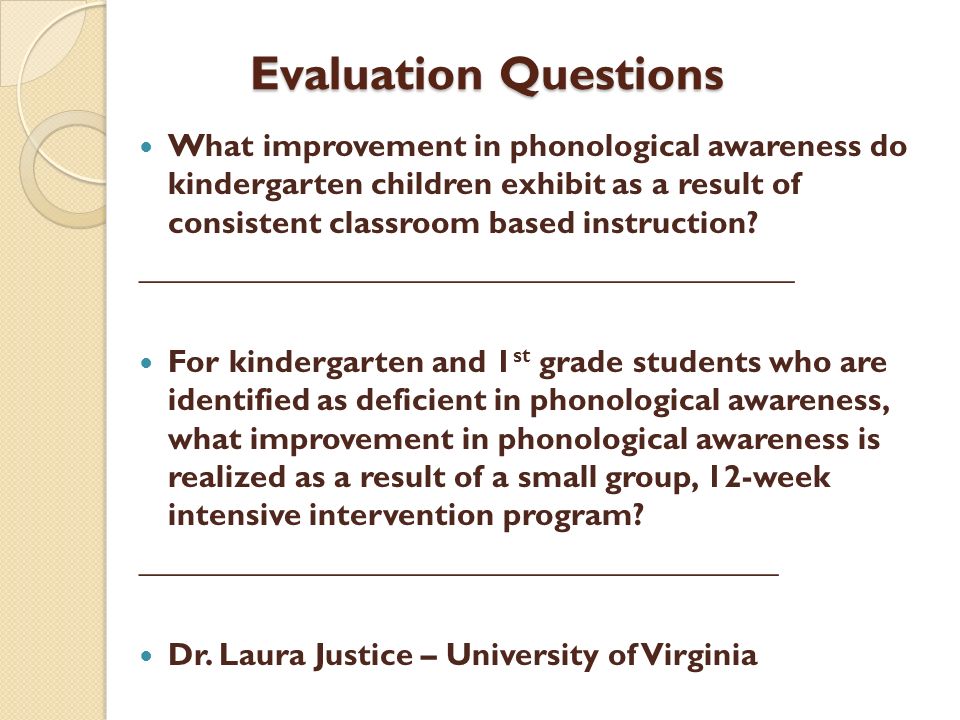

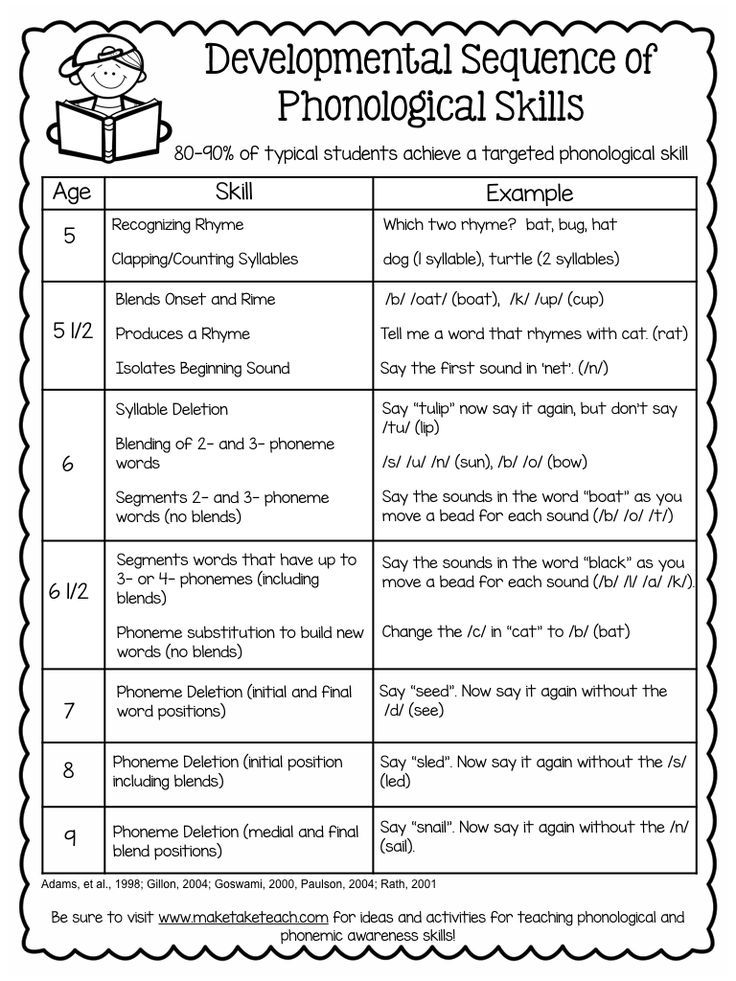

The diagram below shows the development of phonological awareness in typical children, from the simplest, most rudimentary phonological awareness tasks, to full phonemic awareness.

| Phonological awareness skills from simplest to most complex | ||

|---|---|---|

| Word* | Counting words in a sentence | Simplest |

| Syllable | Counting syllables | |

| Onset-rime** | Blending onset and rime | Complex |

| Phonemic awareness | Saying sounds in isolation | Most complex |

*Words (counting words in a sentence) is a language comprehension skill and not a phonological awareness skill. This step is included in the continuum for a reason. Children with low-language skills and English language learners may struggle with language at this level. A weakness at this level will hamper success at phonological awareness skills.

**The onset is the initial consonant or consonant cluster of a one-syllable word, and the rime is the vowel and any consonants that follow it.

Back to top

Benefits of teaching phonological awareness

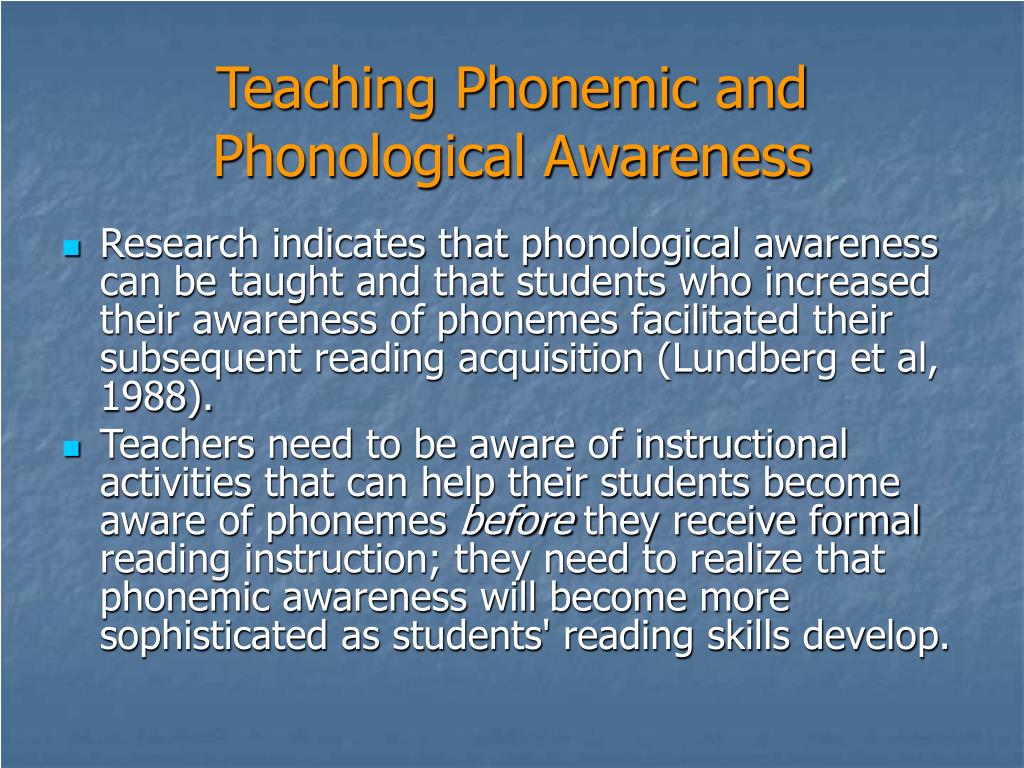

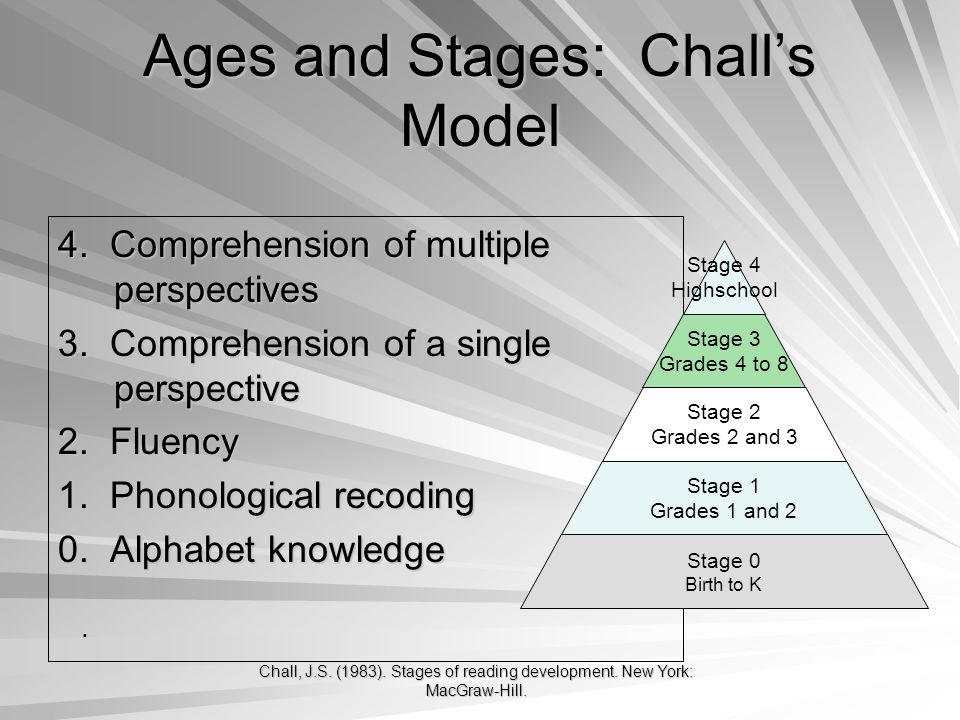

Our brains are wired to process the sounds of speech in oral language There is an area of the brain devoted to this task, which occurs unconsciously when we are listening. However, our brains aren’t pre-wired to translate the speech sounds we hear into letters. When children learn to read they must become consciously aware of phonemes, because learning to decode in English requires matching the sounds in spoken words to individual printed letters.

When children learn to read they must become consciously aware of phonemes, because learning to decode in English requires matching the sounds in spoken words to individual printed letters.

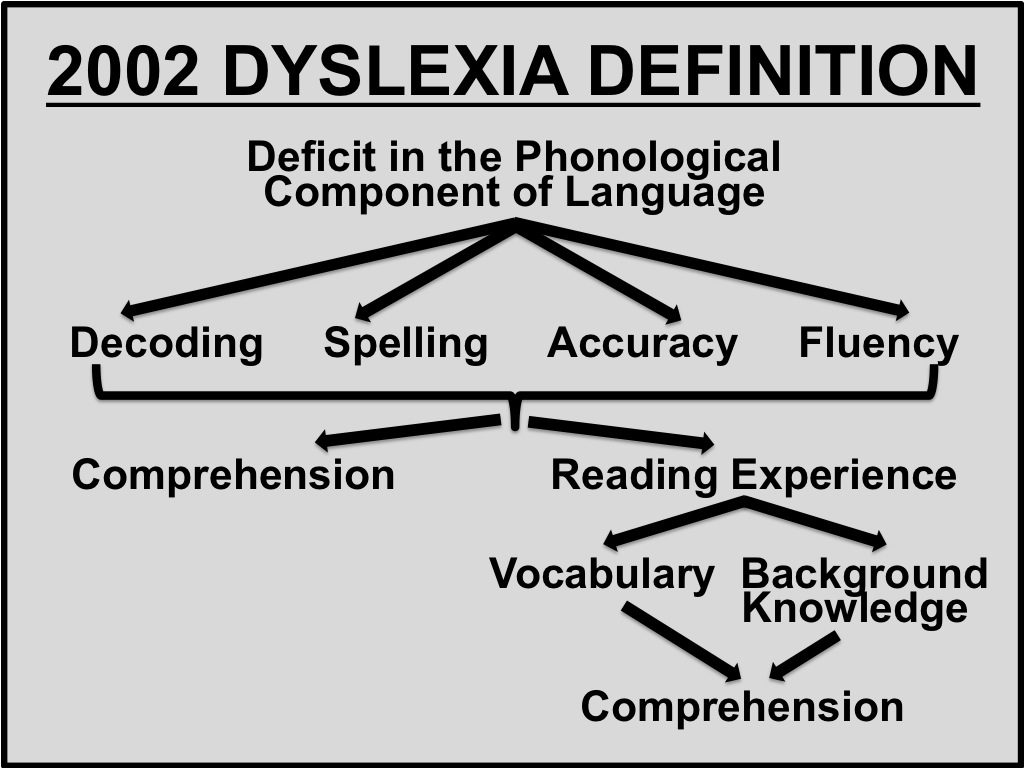

Children with dyslexia often struggle with phonological awareness. They have trouble processing the sounds in spoken language and need additional explicit instruction to strengthen their phonological awareness skills. Learn more about reading, the brain, and dyslexia in this article by Professor Guinevere Eden: How Reading Changes the Brain.

English language learners may also have difficulties with phonological and phonemic awareness. Learn more in this article: What Does Research Tell Us About Teaching Reading to English Language Learners?

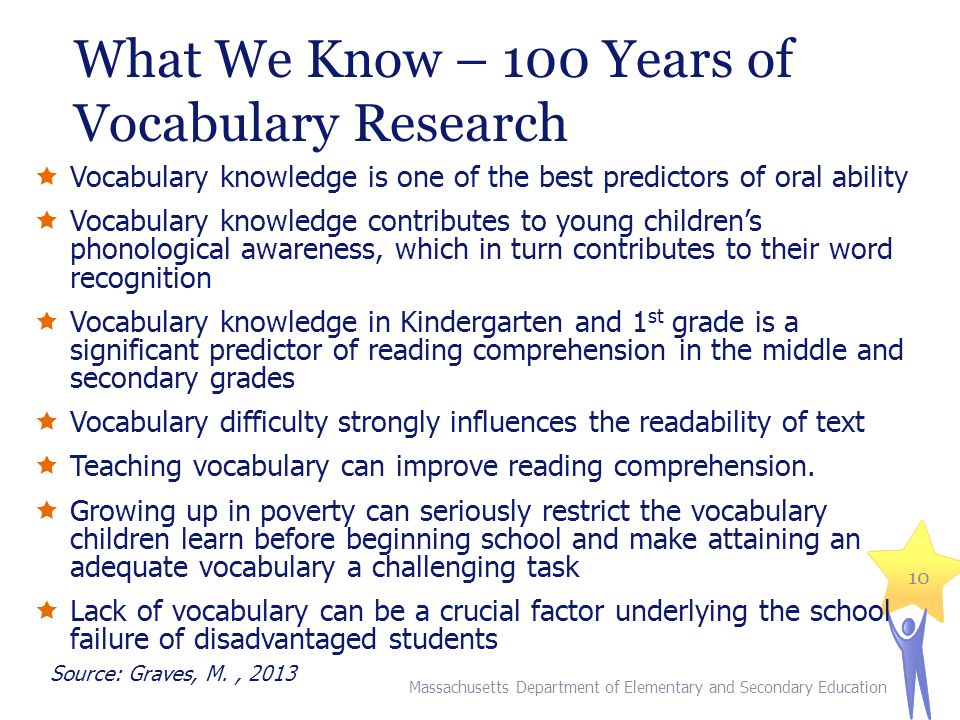

Phonological awareness skills are best taught in kindergarten and early Grade 1 so they can be applied to sounding out words as phonics instruction begins. Research summarized in the National Reading Panel report suggested that even very modest amounts of instruction — as little as 5 to 18 hours in total — in phonological awareness at this stage can yield significant benefits to children’s reading and spelling achievement (Ehri, 2004).

Dr. David Kilpatrick identifies phonological awareness as the single most important factor in differentiating struggling from successful readers and in differentiating between effective and ineffective interventions. In Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties Kilpatrick (2015) tells us that research suggests that “phonological manipulation tasks are the best measures of the phonological awareness, skills needed for reading because they are the best predictors of word-level reading proficiency” because phoneme manipulation (adding, deleting, and substituting) is actually the layer of phonemic awareness that is the most closely related to reading connected text. Learn more in this article by Kilpatrick: Phonological Awareness & Intervention.

Some children, particularly those who have serious decoding difficulties, may continue to need instruction to help strengthen phonemic awareness beyond an early Grade 1 level.

Back to top

Intervention

The activities for teaching phonological awareness in intervention are the same as teaching it to pre-readers, although children who need intervention may require much greater intensity of instruction (e. g., smaller group size, more opportunities for practice) to develop phonological awareness. For children who are old enough for formal reading instruction (i.e., kindergarten and up), phonological awareness instruction should generally be integrated with phonics instruction.

g., smaller group size, more opportunities for practice) to develop phonological awareness. For children who are old enough for formal reading instruction (i.e., kindergarten and up), phonological awareness instruction should generally be integrated with phonics instruction.

For example, as children learn to segment spoken words into phonemes, they also learn to match the appropriate letters to those phonemes. The most important phonological awareness skills for children to learn at these grade levels are phoneme blending and phoneme segmentation, although for some children, instruction may need to start at more rudimentary levels of phonological awareness such as alliteration or rhyming. As skills are mastered, instruction moves to more difficult skills.

Video: Blending Sounds in Syllables with Autumn, Kindergartner

In this video, reading expert Linda Farrell works one-on-one with Autumn to master specific pre-reading skills, with a focus on strengthening her phonological awareness and giving Autumn extra practice with onset and rime. See more videos here: Looking at Reading Interventions.

See more videos here: Looking at Reading Interventions.

Back to top

Multisensory instruction

Instruction is supported by using the body and manipulatives. Students benefit from watching our mouth positions. They can also watch their own mouths with hand mirrors. Instruction is described in detail in the In-Practice section of this module.

Back to top

Phonological awareness lessons

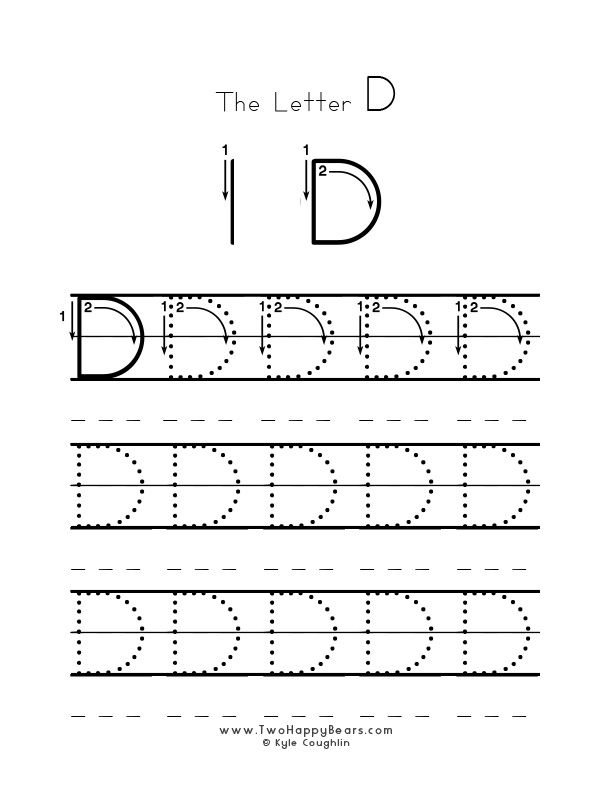

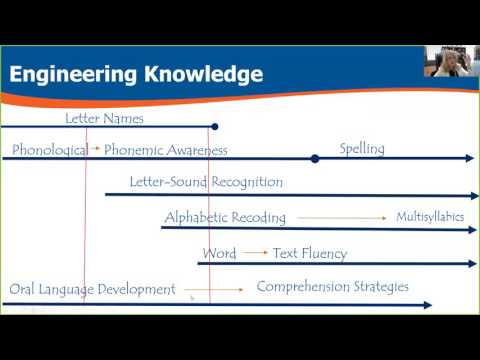

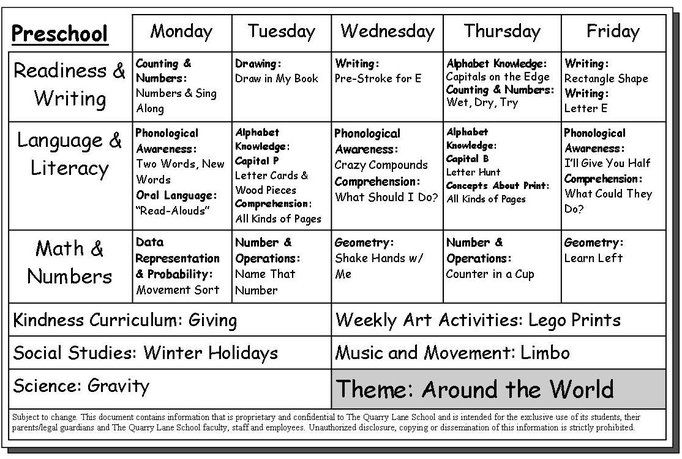

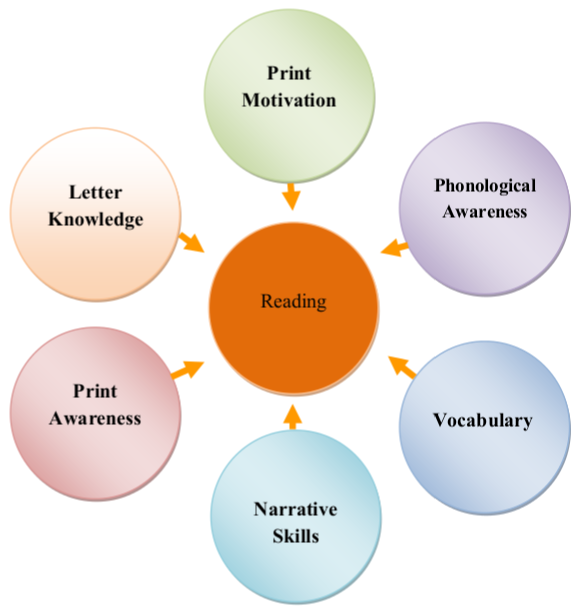

Phonological awareness lessons occur concurrently with teaching letter names and sounds. Teaching should include the following elements, taught concurrently:

| Orthographic Pre-reading Skills | Phonological Pre-reading Skills | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill | Activity | Skill | Activity |

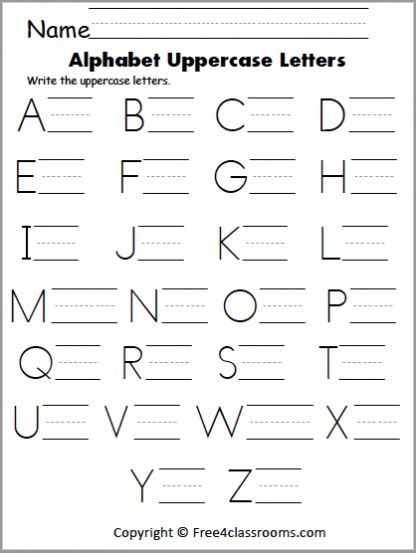

| Letter names: small | Printing small letters | Syllable Activities | Single phonemes (no print) |

| Letter names: capitals | Printing capital letters | Teach consonant sounds, and identify each consonant in the initial and final position | |

| Onset-rime | Teach each short vowel sound, label each one, and identify each one in the initial position | ||

| Teach the long vowels, label each one, and identify each one in initial and final position | |||

| Phonemic Awareness | Teach the r-controlled vowels, label each one, and identify each one in initial and final position * | ||

| Teach other vowels (e. | |||

* Teaching r-controlled and other vowel sounds in isolation can wait until after phonics instruction has started — this may depend on the amount of time available and whether students have mastered prior skills.

Back to top

Video: Mastering Short Vowels and Reading Whole Words with Calista, First Grader

In this video, reading expert Linda Farrell works one-on-one with early stage reader Calista on short vowel sounds, blending and manipulating sounds, reading whole words, and fluency. See more videos here: Looking at Reading Interventions

Next: Phonological and Phonemic Awareness In Practice >

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: In Practice

These activities will work effectively for most students, but children will vary in their response to these activities. Some students will need much more practice than others, and what works well for most students will not necessarily be effective for everyone.

Some students will need much more practice than others, and what works well for most students will not necessarily be effective for everyone.

Language comprehension activities

In this section

Counting words in a sentence

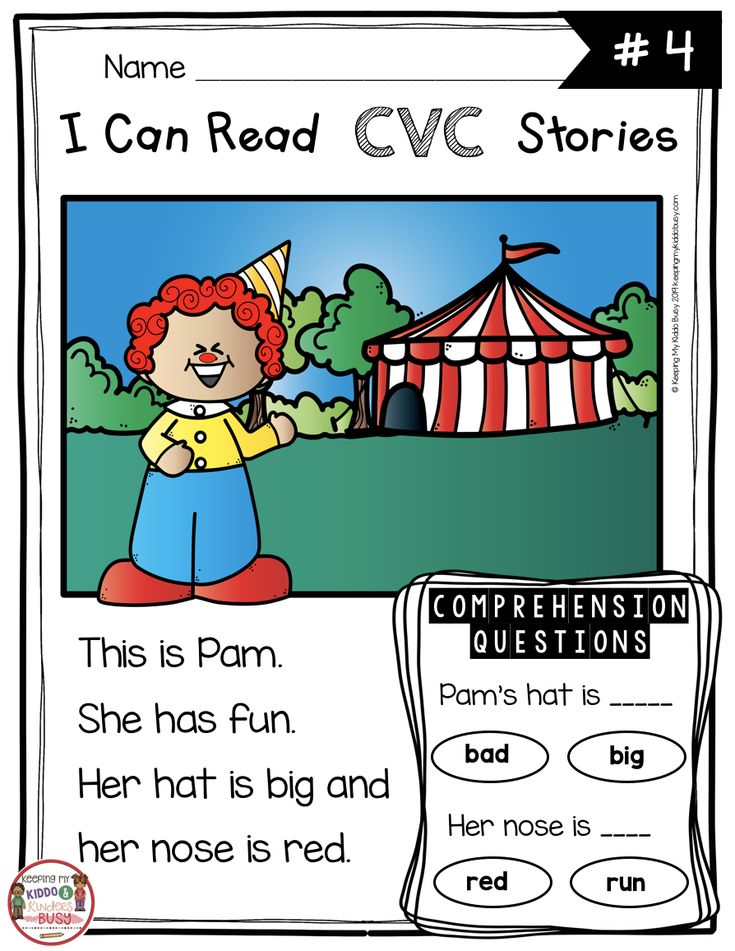

Counting the words in a sentence may seem simple. But when we speak, we run words together. It’s important for young children to learn that the stream of speech is composed of individual words. For children with low language skills or children learning English, this activity is especially crucial. It is perfectly fine to take sentences from a story. The language should be close to common speech.

Steps:

- Give each child a manipulative or manipulatives with which to count the words in a sentence.

- Dictate a sentence. The sentences should be articulated clearly but not in a halting, artificial manner. The words should run together as in natural speech.

- Avoid dictating haltingly: “Mom [pause] went [pause] to [pause] the [pause] store.

”

” - Be careful when dictating phrases such as ‘going to’, ‘would have’, ‘used to’ to pronounce two words. Avoid saying, ‘gonna’, ‘woulda’, ‘useta’, and so on.

- All students repeat the sentence.

- One student uses the manipulatives to count the words.

- All students use the manipulatives to count the words in the same sentence.

Repeat these steps with as many as 10 sentences.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

One manipulative that has been used is a paper bunny cut out and attached to a wooden stick. Students ‘hop the bunny’ for each word in the sentence. Other manipulatives are bingo chips or bottle caps which are counted out for each word.

Sentences should start at two to five words in length, then should get a little longer, but generally should not exceed eight words.

Back to top

Phonological awareness activities

Counting syllables

Counting syllables requires the student to know what a syllable is. Introduce the vocabulary word: syllable. Syllables can be explained to children in this manner:

Introduce the vocabulary word: syllable. Syllables can be explained to children in this manner:

“Words are made up of syllables. Some words have 1 syllable. Some words have lots of syllables. Our mouth knows where the syllables are. Let’s use our mouth to feel syllables. Watch me. I will use something called clamped lips to feel syllables. I will close my lips tightly and shout the word ‘classroom’.”

Close your lips tightly and shout ‘classroom’. Students will hear two muffled shouts.

“I heard two shouts. I felt two pushes of air. I wanted to open my mouth 2 times. That means ‘classroom’ has two syllables. I hold up two fingers to show how many syllables are in ‘classroom’. Do it with me.” Then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate words in a natural manner.

- Avoid dictating haltingly: “mon [pause] ster”

- Dictate words as they are said, not as they are spelled. For example, say ‘DOC-ter’ not ‘doct-OR’.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students shout the word with clamped lips.

- All students show how many syllables using their fingers.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words. Early lessons should include words with one and two syllables. Then include words with three syllables. When students are proficient, introduce some challenge words with four or more syllables. Remember to include one-, two-, and three-syllable words as well.

After some practice, take away the scaffold of using clamped lips:

Steps:

- We dictate words in a natural manner.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students show how many syllables using their fingers.

Back to top

Segmenting syllables

Segmenting syllables is easily taught after students can use clamped lips to count syllables. It is best to restrict this activity to words with three or fewer syllables.

“I can say a word, then say each syllable in the word. As I say each syllable, I will lay down a card. I will lay the cards left to right. Watch me. I say the whole word: ‘Peanut’. I say each syllable and put down a card: ‘pea’ [place a card] ‘nut’ [place a card so it appears left-to-right for students]. Now I sweep my finger below the cards and say the whole word: ‘peanut’ [sweep finger below the cards left-to-right]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate words in a natural manner.

- All students repeat the word.

- One student uses the manipulatives to segment the syllables.

- All students use the manipulatives to segment the syllables.

Repeat these steps with 10 to 15 words. Early lessons should include words with one and two syllables. Then include words with three syllables.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

Manipulatives can be cards, felts, bingo chips, bottle caps, or other objects.

Back to top

Identifying first, last, middle syllables

Identifying syllables requires the student to segment the word, then say just the target syllable. It is best to restrict this activity to words with three or fewer syllables. First, middle, and last are sufficient for this task. When students move to print, the student can carry this skill into sounding out longer words for spelling and reading.

“I can say each syllable in the word. Then I can say just the first syllable. As I say each syllable, I will lay down a card. Watch me. I say the whole word: ‘sunset’. I say each syllable and put down a card: ‘sun’ [place a card] ‘set’ [place a card so it appears left-to-right for students]. I say the whole word: ‘sunset’ [sweep finger below the cards left-to-right]. I touch and say just the first syllable: ‘sun’ [touch the first card]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate words in a natural manner.

- All students repeat the word.

- One student uses the manipulatives to segment the syllables.

- Introduce this by saying, “One student will be our voice, everyone else will segment the syllables silently.”

- [Name], segment [word].

- All students (silently) use the manipulatives to segment the syllables.

- A different student identifies just the first syllable.

- Everyone, what is the first syllable?

- All students touch and say the first syllable.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words. Start with one and two syllable words. Start with just identifying the first syllable. Introduce identifying the last syllable. Combine identifying the first and last syllable with one, two and three syllable words. Add three syllable words. Introduce identifying the middle syllable.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

Back to top

Blending syllables

Blending syllables should be taught after students can segment. It is best to restrict this activity to words with three or fewer syllables.

“I can say each syllable in a word and then I can blend the syllables to say the word. As I say each syllable, I will lay down a card. I will lay the cards left to right. Watch me. I say each syllable and put down a card: ‘lap’ [place a card] ‘top’ [place a card so it appears left-to-right for students]. Now I sweep my finger below the cards and say the whole word: ‘laptop’ [sweep finger below the cards left-to-right]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate syllables.

- All students repeat the syllables and place the cards.

- One student blends the syllables.

- All students blend the syllables.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words. Early lessons should include words with one and two syllables. Then include words with three syllables.

Then include words with three syllables.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

Back to top

Manipulating syllables (adding, deleting, substituting)

Adding

Manipulating syllables should generally be taught in this sequence: add, delete, substitute. Adding syllables is very similar to blending syllables. Students already know what to do with the cards. As such, it is the easiest manipulation.

“I can add syllables to make a new word. Watch me. I say the first syllable and put down a card: ‘lap’ [place a card]. I add the last syllable: ‘top’ [place a card so it appears left-to-right for students]. I touch and say the syllables: ‘lap’, ‘top’, ‘laptop’ [sweep finger below the cards left-to-right]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate the first syllable and places a card.

- All students repeat the syllable and place a card.

- We dictate the second syllable and place a card.

- All students repeat the syllable and place a card.

- All students touch and say, then blend the syllables to say the word.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 two-syllable words.

Deleting

“Watch me take away a syllable from a word. The word is: ‘pencil’. ‘Pen’ ‘cil’ [place a card for each syllable so it appears left-to-right for students]. ‘Pencil’ [sweep finger below the syllables and say the word]. I take away ‘cil’ [remove the card]. ‘Pen’ is left [touch remaining card]. Do it with me.”; We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate the word and place the cards.

- All students repeat the word and place the cards.

- All students touch and say, then blend the syllables to say the word.

- We dictate the syllable to remove, alternating between first and last.

- All students touch and say the remaining syllable.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 two-syllable words.

Substituting

“I can change one syllable in a word to form a new word. Watch me. I will change ‘suntan’ to ‘sunset’. Which syllable is different in ‘suntan’ and ‘sunset’? I will use the cards. The first word is ‘suntan’ [say syllables, lay cards, touch and say syllables, blend word]. I want to change ‘suntan’ to ‘sunset’. [Touch below the cards, say new syllables, blend new word]. The second syllable is different. I’ll change the cards to and say the new syllable: [pick up second card and say ‘tan’, lay down new card and say ‘set’]. I’ll touch and say the new word: [say syllables, lay cards, touch and say syllables, blend word].

Steps:

- We dictate old word to new word.

- All students repeat old word to new word, and lay cards for each syllable.

- All students touch and say, then blend the old word.

- We repeat the new word.

- Below the cards, all students touch and say, then blend the new word.

- We ask: syllable going out?

- All students touch and say the syllable, removing the card.

- We ask: syllable going in?

- All students touch and say the syllable, adding a card.

- All students touch and say, then blend the new word.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words.

Back to top

Blending onset and rime

An onset is the initial consonant or consonant cluster of a one-syllable word. A rime is the vowel and any consonants that follow the onset. So in the word “map,” /m/ is the onset and /ap/ is the rime.

Unlike with syllables, we do not need to teach the vocabulary terms of onset-rime. This skill is a scaffold to phonemic awareness skills, and not one with enduring usefulness. Blending onset-rime is more easily taught after students can blend syllables. Use only words with a single onset sound. Blends can be taught in phonics instruction.

We are modeling facing students. We work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students.

We work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students.

“I can blend two parts of a syllable to make a word. Watch me. /M/ [we put right fist on the table], /ap/ [we put left fist on table], ‘map’ [we slide our fists together to touch in front of her]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate onset [pause] rime, using fists to represent onset and rime.

- All students repeat the sounds and use their fists to represent the sounds.

- One student blends the onset and rime to say the word.

- All students blend the onset and rime to say the word.

Repeat these steps with as many as 10 words. Remember to use words with only one onset sound. For example, use /ch/ /in/ but avoid /sw/ /im/.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

Back to top

Onset-rime completion

As with all onset-rime activities, use only words with a single onset sound.

We are modeling facing students. We work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students.

“I will say a word and give you the first part. Then you say the last part. Watch me. The word is ‘tape’. The first part is /t/ [we put right fist on the table]. What’s the rest of the word? /Ape/ [we put left fist on table]. The word is ‘tape’ [we slide our fists together to touch in front of her]. Do it with me.”; We then lead the group through two examples.

Steps:

- We dictate onset, using a fist to represent the onset sound.

- All students repeat the onset sound and put a fist down.

- One student adds the rime and puts the right fist down, then blends the onset and rime to say the word.

- All students blend the onset and rime to say the word.

Repeat these steps with as many as 10 words.

Following these steps, students have individual turns and group practice to ensure the maximum amount of practice in a brief activity.

Back to top

Do these words rhyme?

For students to learn whether words rhyme, and to generate rhyming words, they must understand what rhyming is. Introduce the vocabulary word: rhyme. Rhyming can be explained to children in this manner:

We are modeling facing students. We work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students.

“Words rhyme when they end with the same sounds. For example, I can check to see whether ‘make’ and ‘take’ rhyme. Watch me. I blend two parts of each word. /M/ [we put right fist on the table], /ake/ [we put left fist on table], ‘make’ [we slide our fists together to touch in front of her]. /T/ [we put right fist on the table], /ake/ [we put left fist on table], ‘take’ [we slide our fists together to touch in front of us]. The ending sounds for both words were the same: /ake/ [hold up left fist when facing the students to show the ends were the same]. I will do a few and you tell me whether they rhyme.”

We then lead the group through two more examples, one that doesn’t rhyme and one that does. We direct the students to show thumbs up or down to indicate whether the words rhyme.

We direct the students to show thumbs up or down to indicate whether the words rhyme.

Steps:

- We dictate two words. Don’t say anything between the words; a brief pause will suffice.

- All students repeat the words.

- All students show the two parts of the first word using their fists.

- All students show the two parts of the second word using their fists.

- All students show thumbs up or down to indicate whether the words rhyme.

After some practice, take away the scaffold of segmenting the onset and rime:

Steps:

- We dictate two words.

- One student shows thumbs up or down to indicate whether the words rhyme.

- All students show thumbs up or down to indicate whether the words rhyme.

This activity can be extended to include three words. We ask students which two words rhyme.

Repeat these steps with as many as 10 sets of words.

Back to top

Generating rhyming words

For students with poor phonological awareness, coming up with words that rhyme is a difficult task. For other students, it will be hard to keep them from blurting out rhyming words. To make the task easier, allow nonsense words as well as real words.

For other students, it will be hard to keep them from blurting out rhyming words. To make the task easier, allow nonsense words as well as real words.

“I can say two words that rhyme. Watch me. ‘Watch’ ‘notch’. They rhyme. I can say a word that rhymes. It doesn’t have to be a real word. ‘Watch’ ‘zotch’. ‘Zotch isn’t a real word, but it rhymes with ‘watch’ because both words end with the same sounds.”

We then lead the group through two more examples. Then we dictate a word and asks individual students to provide words that rhyme. If the student struggles, we can provide a new onset sound and have the student blend to create a rhyme.

Repeat these steps with as many as 10 words.

Back to top

Single phoneme instruction

New consonant sounds

We should ensure they are articulating the consonant sounds correctly before starting instruction. Be sure to say a consonant sound without a trailing /uh/ sound at the end. For example, the first sound in ‘foot’ is /fffff/ not /fuh/. Adding the trailing /uh/sound interferes with blending sounds to sound out words. It is critical that we articulate sounds correctly, so they can learn the sounds correctly. See Ehri (2020): Connected Phonation is More Effective than Segmented Phonation for Teaching Beginning Readers to Decode Unfamiliar Words.

Adding the trailing /uh/sound interferes with blending sounds to sound out words. It is critical that we articulate sounds correctly, so they can learn the sounds correctly. See Ehri (2020): Connected Phonation is More Effective than Segmented Phonation for Teaching Beginning Readers to Decode Unfamiliar Words.

Here is a list of the 44 sounds (phonemes) of the English language. Below, watch a video showing how each of the sounds is pronounced.

Teaching sounds in isolation can start with children as young as age 4, but articulation may interfere with repeating some sounds. Consonant sounds can be introduced in this way:

Steps:

- We say: “You will learn a new consonant sound. The sound is: [sound]. Listen again: [sound].”

- Students repeat the sound 4 or 5 times as we walk through the room listening.

- Ensure all students are saying the sound correctly and not adding the /uh/ to the trailing end of the consonant.

- For correction, describe how the sound is formed (lips, teeth, tongue), use hand mirrors so students can see themselves making the sounds.

- We call on 6 to 10 individual students to say the sound.

- All students say the sound.

Back to top

New vowel sounds

Again, we should ensure they are articulating the vowel sounds correctly before starting instruction.

Vowel sounds can be introduced in this way:

Steps:

New sound

- We say: “You will learn a new vowel sound. The sound is: /ăăăă/. Listen again: /ăăăă/.”

- Students repeat the sound 4 or 5 times as we walk through the room listening. Ensure that all students are saying the sound correctly.

- For correction, describe how the sound is formed (lips, teeth, tongue), use hand mirrors so students can see themselves making the sounds.

- We call on 6 to 10 individual students to say the sound.

- All students say the sound.

Teach the label

- We say: “A label is what we call something. The label for the sound /ăăăă/ is short a.”

- All students repeat the label.

- We call on 6 to 10 individual students and asks 2 questions in a different order: “What’s the short a sound? What’s the label for the sound /ăăăă/?”

- All students say the sound.

- All students say the label.

Back to top

Match the new sound in the initial position

After learning the new (consonant or vowel) sound, teach students to hear the new sound in the initial position. Introduce the activity:

Now you will listen for [sound] at the start of words. You will tell me whether or not the word starts with the sound [sound]. Watch me. I’ll say a word. I’ll show a thumbs up if the word starts with the sound [sound]. I’ll show a thumbs down if the word doesn’t start with the sound [sound]. ”

”

[We say a word that starts with the target sound, pauses, then shows a thumbs up. We say another word that doesn’t start with the target sound, pauses, then shows a thumbs down.]

“Let’s do some together.”

[We lead the group through two examples, one with a word that starts with the target sound and one that does not start with the target sound.]

Steps:

- We tell students to listen for words that start with the sound [sound].

- We dictate a word.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students show a thumbs up or down to indicate whether the word starts with the target sound.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words in a lesson. Start with consonants, then move to short vowels, then long vowels. Do not use words with blends at the beginning.

Back to top

Match the new sound in the final position

Immediately after listening for a new sound in the initial position, students can listen for the same target sound in the final position. This cannot be done with short vowels, of course, as English words do not end in short vowel sounds. Introduce the activity:

This cannot be done with short vowels, of course, as English words do not end in short vowel sounds. Introduce the activity:

“Now you will listen for [sound] at the end of words. You will tell me whether or not the word ends with the sound [sound]. Watch me. I’ll say a word. I’ll show a thumbs up if the word ends with the sound [sound]. I’ll show a thumbs down if the word doesn’t end with the sound [sound].”

[We say a word that ends with the target sound, pauses, then shows a thumbs up. We say another word that doesn’t end with the target sound, pauses, then shows a thumbs down.]

“Let’s do some together.”

[We lead the group through two examples, one with a word that end with the target sound and one that does not end with the target sound.]

Steps:

- We tell students to listen for words that end with the sound [sound].

- We dictate a word.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students show a thumbs up or down to indicate whether the word ends with the target sound.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words in a lesson

Start with consonants, resume the activity when teaching long vowels. Do not use words with blends at the beginning.

Back to top

Phonemic awareness activities

Even though segmenting sounds is harder than simply identifying the first or last sound, this is a reasonable next step if students have mastered onset-rime. This activity starts with segmenting, and later includes identifying individual sounds.

Segmenting sounds in a syllable

“Words can be broken into individual sounds. We call this segmenting sounds. A segment is a piece of something. We will break words into pieces or segments.”

[Distribute 3 manipulatives per student — in this example, bottle caps.]

When we are modeling, we may have to work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students. If we are working on the board, we can work left-to-right.

“First I will show you how to use the caps. I will count 1, 2, 3 and put a cap out for each number. Watch me. 1 [slide a cap forward], 2 [slide a cap working from students’ left-to-right], 3 [slide a cap working from students’ left-to-right]. You do it.”

I will count 1, 2, 3 and put a cap out for each number. Watch me. 1 [slide a cap forward], 2 [slide a cap working from students’ left-to-right], 3 [slide a cap working from students’ left-to-right]. You do it.”

[Push the caps into a pile to show the start of a new word.]

“Now I will segment sounds in a word, and I will use the caps to show each sound. Watch me. The word is ‘feet’, /f/ [slide a cap], /ee/ [slide a cap], /t/ [slide a cap], feet [sweep finger below the caps blending the sounds]. I’ll do another.”

We model one or two more words, then leads the group through two examples. Do not use words that contain the letter ‘x’ or ‘qu’ because those represent 2 phonemes each (x=ks; qu=kw). Use words with one, two, or three sounds. Do not use words with blends until all students have mastered segmenting three sound words. Do not use words with r-controlled or strong diphthongs (oy and ou) until students have learned those sounds in isolation.

Steps:

- We dictate a word.

- All students repeat the word.

- One student segments the sounds, sliding a cap for each sound and sweeping a finger below to blend the sounds back into the word.

- All students segment the sounds, sliding a cap for each sound and sweeping a finger below to blend the sounds back into the word.

- Another student points and says the first sound.

- [after that skill is mastered add:]

- Another student points and says the last sound.

- [after that skill is mastered add:]

- Another student points and says the vowel sound (i.e., /ă/).

- Another student points and says the vowel label (i.e., short a)

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words in a lesson.

We can align this activity with vowel sounds being taught in isolation. We may have taught the short a sound and label earlier in the day. Then we select short a words to segment. In this manner, students master the vowel sounds and labels in the context of spoken words. It takes more effort in word selection. It yields powerful results by providing solid basis for spelling and reading.

It takes more effort in word selection. It yields powerful results by providing solid basis for spelling and reading.

Watch and learn

Dr. Louisa Moats helps a kindergarten teacher learn a technique for teaching phonemic segmentation using chips — to help students learn to identify the individual sounds within a word. Letters can be introduced later.

Back to top

Blending sounds

[Distribute three manipulatives per student — in this example, bottle caps.]

“We can blend sounds to say a word. Watch me. The sounds are /s/ [slide a cap], /ō/ [slide a cap], /p/ [slide a cap]. I will touch and say, then blend. /s/ [touch first cap], /ō/ [touch middle cap], /p/ [touch last cap], soap [sweeping a finger below the caps]. Do it with me.”

When we are modeling, we may have to work right-to-left so it appears left-to-right for students. If we are working on the board, we can work left-to-right.

[Push the caps into a pile to show the start of a new word.]

We lead the group through two examples. Remember, do not use words that contain the letter ‘x’ or ‘qu’ because those represent 2 phonemes each. Use words with one, two, or three sounds. Do not use words with blends until all students have mastered segmenting three sound words. Do not use words with r-controlled or strong diphthongs (oy and ou) until students have learned those sounds in isolation.

Steps:

- We dictate the sounds, using caps to show the sounds.

- All students repeat the the sounds, using caps to show the sounds.

- One student touches and says the sounds, then sweeps a finger below to blend the sounds into a word.

- All students touch and say the sounds, then sweep a finger below to blend the sounds into a word.

- Another student points and says the first sound.

- [after that skill is mastered add:]

- Another student points and says the last sound.

- [after that skill is mastered add:]

- Another student points and says the vowel sound (i.e., /ō/).

- Another student points and says the vowel label (i.e., long o)

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words in a lesson. As with segmenting, words can be selected that reinforce sounds being taught in isolation.

Back to top

Manipulating sounds (adding, substituting, deleting)

This phonemic awareness activity is the most difficult of all the phonological awareness activities. It is the pinnacle skill. Keep in mind that poor phonological awareness is the most common area of weakness for struggling readers. Students who master this skill are on a solid footing for reading success.

Adding sounds

It generally makes sense to teach the manipulation of sounds in this sequence: add, substitute, delete, for pragmatic reasons. One needs sounds to delete, so adding and substituting must occur before deleting. Manipulating sounds is similar to manipulating syllables.

Manipulating sounds is similar to manipulating syllables.

Remember, do not use words that contain the letter ‘x’ or ‘qu’ because those represent 2 phonemes each. Use words with one, two, or three sounds. Do not use words with blends until all students have mastered segmenting three sound words. Do not use words with

r-controlled or strong diphthongs (oy and ou) until students have learned those sounds in isolation.

“I can add sounds to make new word. Watch me. I say the first sound and slide a cap: /ī/ [slide a cap]. I add the last sound: /s/ [slide a cap so it appears left-to-right for students]. I touch and say the syllables: /ī/, /s/, ‘ice’ [sweep finger below the caps left-to-right]. The first sound is /ī/ [touch first cap]. The vowel sound is /ī/ [touch first cap]. The vowel label is long i [touch first cap]. The last sound is /s/ [touch last cap]. Do it with me.” We then lead the group through two examples.

Note: We can add sounds in this manner: /m/ /ĭ/, /m/ /ĭ/ /s/, or /ĭ/ /s/, /m/ /i/ /s/. The only change in procedure is to announce whether adding a sound at the start or end of the word.

The only change in procedure is to announce whether adding a sound at the start or end of the word.

[Push the caps into a pile to show the start of a new word.]

Steps:

- We say a sound and slides a cap.

- All students repeat the sound and slide a cap.

- We say whether adding a starting or ending sound, then dictates the sound and slides a cap.

- All students repeat.

- All students touch and say, and then blend the sounds into a word.

- All students touch and say, then blend the syllables to say the word.

- One student touches and says the first sound.

- Another student touches and says the last sound.

- Another student touches and says the vowel sound.

- Another student touches and says the vowel label.

Repeat these steps with as many as 15 words

Substituting sounds

“I can change one sound in a word to form a new word. Watch me. I will change ‘make’ to ‘bake’. Which sound is different in ‘make’ and ‘bake’? I will use the caps to find the sound that changes.”

I will change ‘make’ to ‘bake’. Which sound is different in ‘make’ and ‘bake’? I will use the caps to find the sound that changes.”

[We use the caps to touch and say, then blend ‘make’. Below the caps, we touch and say, then blends ‘bake’.]

“The first sound in make is /m/. The first sound in bake is /b/. I remove the first cap, and slide a new cap.”

[We remove the first cap, saying /m/. We slide in a new cap, saying /b/.]

“Not I’ll touch and say the new word. /b/ [touch first cap], /ā/ [touch middle cap], /k/ [touch last cap], ‘bake’ [sweep finger below caps].”

We model one more example, then leads the group through two examples.

Steps:

Starting word

- We dictate a starting word.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students slide caps to show each sound, then sweep a finger below to blend the sounds into a word.

Substituting a sound

- We say: “Change [old word] to [new word].

Repeat.”

Repeat.” - All students repeat “Change [old word] to [new word].”

- All students touch and say, then blend old word.

- All students touch and say, then blend new word [pointing below caps].

- We instruct students to point at the sound that changes.

- One student removes the cap, saying the sound going out.

- Another student puts a new cap in, saying the sound going in.

- All students touch and say, then blend the new word.

Repeat these steps with 4 to 6 words in a lesson.

Substitute just the first sound for several lessons. Substitute the first and last sounds for several lessons. Finally teach substituting the middle sound. Practice substituting sounds for several lessons. Then reintroduce adding sounds. Practice adding and substituting sounds for several lessons before introducing deleting sounds.

Deleting sounds

“I can delete one sound in a word to form a new word. Watch me. I will change ‘bike’ to ‘by’. Which sound is removed in ‘bike’ to ‘by’? I will use the caps to find the sound that is removed.”

Watch me. I will change ‘bike’ to ‘by’. Which sound is removed in ‘bike’ to ‘by’? I will use the caps to find the sound that is removed.”

[We use the caps to touch and say, then blend ‘bike’. Below the caps, we touch and say, then blends ‘by’.]

“The last sound in ‘bike’ is /k/. The last sound in ‘by’ is /ī/. I will remove the last cap.”

[We remove the last cap, saying /k/.]

“Now I’ll touch and say the new word. /b/ [touch first cap], /ī/ [touch last cap], ‘by’ [sweep finger below caps].”

We model an example of deleting the first sound and the last sound. We lead the group through two examples, once deleting the first sound and once deleting the last sound.

Steps:

Starting word

- We dictate a starting word.

- All students repeat the word.

- All students slide caps to show each sound, then sweep a finger below to blend the sounds into a word.

Deleting a sound

- We say: “Change [old word] to [new word].

Repeat.”

Repeat.” - All students repeat “Change [old word] to [new word].”

- All students touch and say, then blend old word.

- All students touch and say, then blend new word [pointing below caps].

- We instruct students to point at the sound that will be removed.

- One student removes the cap, saying the sound going out.

- All students touch and say, then blend the new word.

Repeat these steps with 6 to 8 words in a lesson. Delete sounds for several lessons. Then reintroduce adding and substituting sounds.

These additions, substitutions and deletions will form sound chains — not spelling chains. For example: ick to sick, to lick, to like, to lime, to dime, to die, to I.

Once you’ve introduced the skills of adding, substituting, and deleting sounds, you can continue to have the students practice these skills.

Back to top

References

Ehri, L. C. (2004). Teaching phonemic awareness and phonics: An explanation of the National Reading Panel meta-analyses. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 153-186). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co.

In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 153-186). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co.

O’Connor, R. E. (2011). Phoneme awareness and the alphabetic principle. In R. E. O’Connor & P. F. Vadasy (Eds.), Handbook of reading interventions (pp. 9-26). New York: Guilford.

What Abilities a Child Affects Successful Mastering of Mathematics – News – IQ Research and Education Portal – National Research University Higher School of Economics

associated with his mathematical achievements in elementary school. However, the relationship between sound speech sensitivity and math acquisition varies depending on the socioeconomic status of the child's family.Research results published in preprint The effect of phonological ability on math is modulated by socioeconomic status in elementary school.

According to many researchers, mathematical skills are the key to mastering the school curriculum in the field of exact and natural sciences. Mathematical achievement is considered an important factor in choosing educational paths and professional development in the field of science and technology. That is why many studies in the field of education are aimed at identifying early cognitive predictors (prognostic parameters) of mathematical achievement. This allows, among other things, to identify children for whom the development of mathematics is problematic and to plan possible correction programs.

Mathematical achievement is considered an important factor in choosing educational paths and professional development in the field of science and technology. That is why many studies in the field of education are aimed at identifying early cognitive predictors (prognostic parameters) of mathematical achievement. This allows, among other things, to identify children for whom the development of mathematics is problematic and to plan possible correction programs.

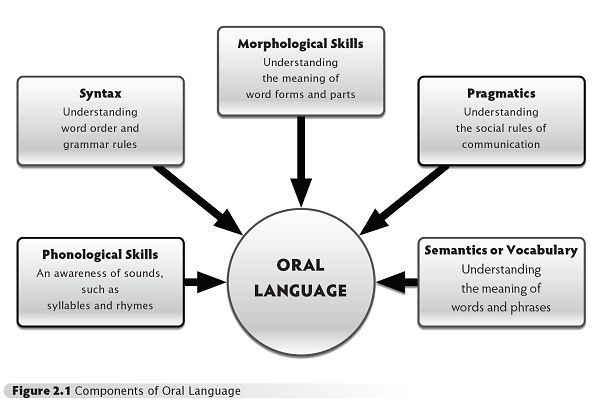

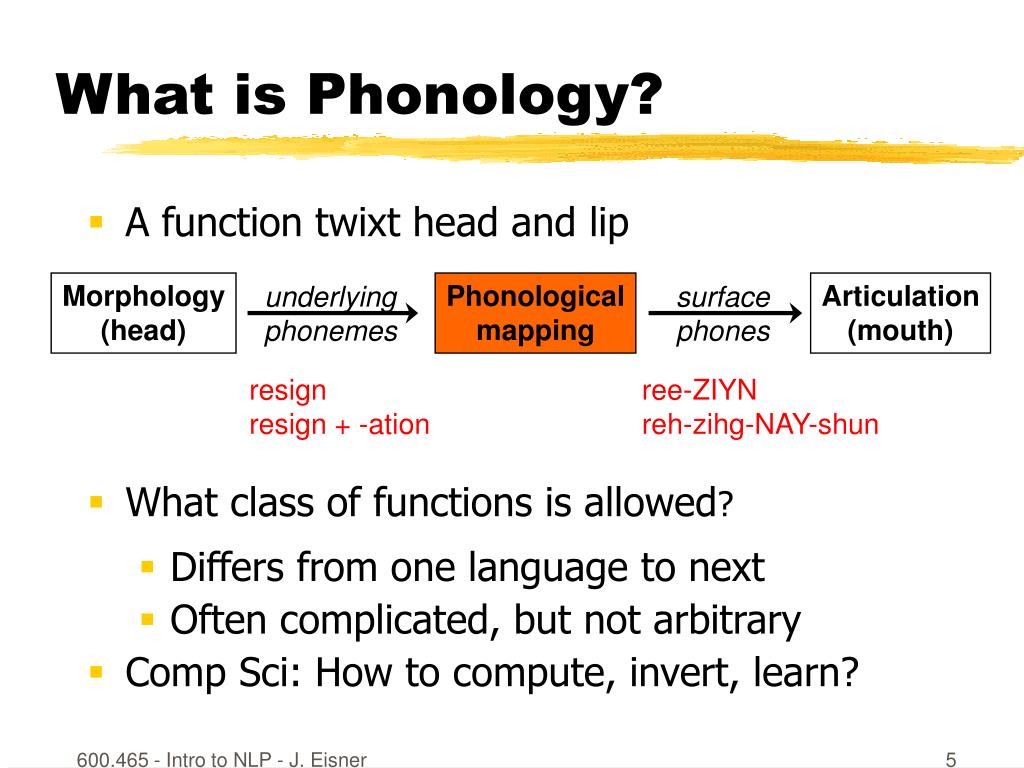

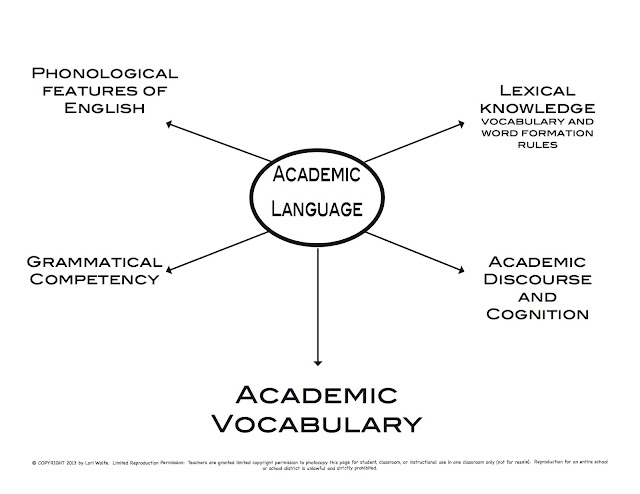

When discussing the prerequisites for mathematical achievement, many researchers distinguish between non-specific (general) cognitive predictors and specific ones (only for mathematics). General cognitive abilities include, for example, intelligence or working memory. These are the factors that are associated with academic achievement in any field, whether it be mathematics, reading or a foreign language. Specific mathematical predictors include, for example, knowledge of numbers and understanding of their sequence, spatial abilities. Phonological ability in this classification refers to specific predictors for reading.

Phonological ability in this classification refers to specific predictors for reading.

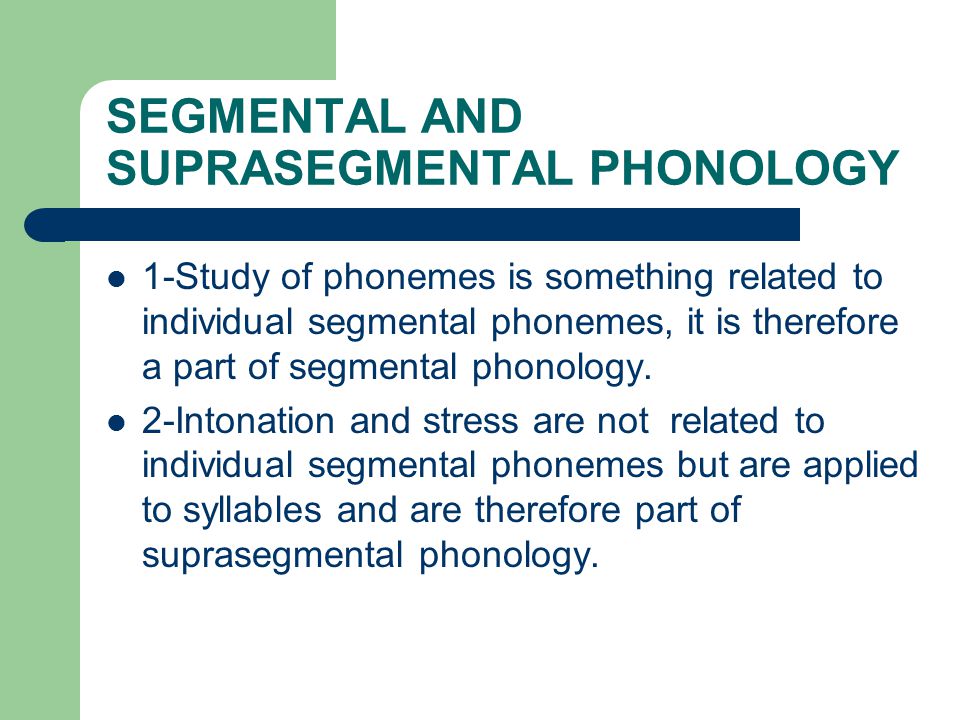

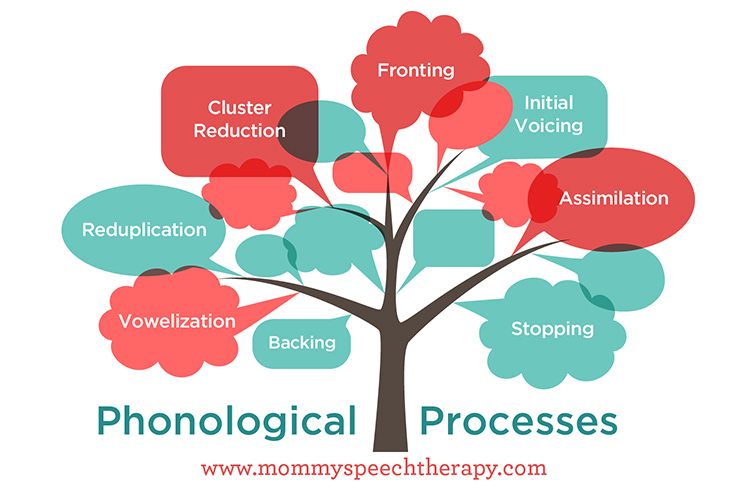

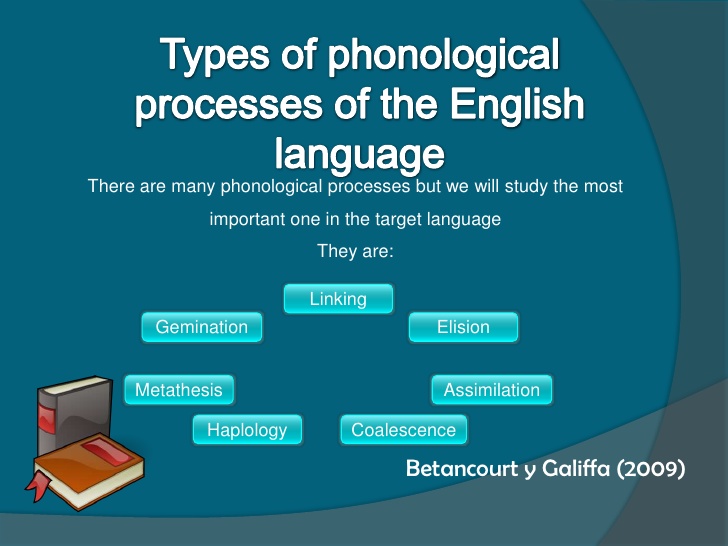

Phonological abilities in a broad sense are understood as sensitivity to the sound structure of speech. More narrowly, three main components of phonological abilities are also distinguished: phonological awareness (awareness), i.e. the ability to recognize and operate with individual speech sounds, phonological memory and lexical access.

More recently, a hypothesis has arisen that phonological abilities are also important for mastering mathematics. For example, when solving text problems, the ability to translate visual information into sound information and vice versa may be involved. Also, some studies have shown that phonological awareness is required to perform those mathematical operations that involve retrieving facts from long-term memory, such as when performing addition and multiplication. In addition, when solving mathematical problems, working memory is used, one of the elements of which is the phonological loop, where information is stored in a sound format.

Phonological is a component of working memory that is involved in the processing of sound information. The words to be memorized are "spoken out" by the inner voice with the help of the phonological loop.

At the same time, it remained unclear whether phonological abilities are directly related to mathematical achievement, or whether this relationship can be explained by the fact that children with a higher level of phonological abilities master reading better. And this gives them advantages, for example, when solving word problems.

In terms of the number of respondents, the work of the Center for Monitoring the Quality of Education of the National Research University Higher School of Economics has become one of the largest studies of the relationship between phonological abilities and mathematical achievements of first-graders. The sample included 2948 first grade students. Their phonological abilities and mathematical achievements were measured twice - at the beginning of the school year (October 2017) and at the end (May 2018).

Mathematical achievements were assessed using the Russian-language version of the iPIPS (International Performance Indicator in Primary School) tool, which was adapted and validated in 2013-2015.

To measure phonological abilities, children were asked to complete two types of tasks. The first is for phonological memory. The child was told either a real-life word or an invented one, and he had to quickly repeat it. The second is phonological awareness. The child had to find a rhyme to the proposed word from the four available options.

Examples of addition and subtraction of two-digit numbers and word problems were included in the tasks for assessing mathematical achievements. The ability to correctly name two-, three- and four-digit numbers, which were visually presented, was also assessed separately.

In addition, the speed and ease of reading of the child and the extent to which he is able to understand the read text were taken into account.

The researchers also looked at the socioeconomic status (SES) of the student's family. Previous research has shown that children with low SES perform worse in both math and reading. The presence or absence of higher education in the mother of the child, as well as the number of books in the family, were used as SES indicators.

Previous research has shown that children with low SES perform worse in both math and reading. The presence or absence of higher education in the mother of the child, as well as the number of books in the family, were used as SES indicators.

In addition, the researchers took into account the possible bilingualism of the student. Since the study was conducted in Kazan, some of the children, according to their parents, used the Tatar language at home. At the same time, school teaching for all was in Russian.

The results of the study showed that children who have a higher level of phonological abilities demonstrate better achievements in mathematics. At the same time, the relationship of phonological abilities with mathematical success remains significant even when reading skills and knowledge of numbers are taken into account. This reflects the independent contribution of phonological abilities to mathematical achievement.

First-graders from families in which mothers had higher education showed better results both at the beginning of the school year and higher progress during the year. Meanwhile, indicators of cultural capital (number of books and knowledge of a second language) had no effect on the mathematical achievements of children at the beginning and end of the first grade.

Meanwhile, indicators of cultural capital (number of books and knowledge of a second language) had no effect on the mathematical achievements of children at the beginning and end of the first grade.

In addition, it was found that the relationship of phonological abilities with mathematical performance differs for children with different SES. For children from families with more books at home, this relationship was higher than for children with fewer books at home. This may indicate a higher involvement of phonological processes in the course of solving mathematical problems. Previous studies show that families with higher levels of cultural capital are characterized by higher levels of verbal interactions in the family, higher frequency of reading books and other verbal activities. It is possible that in the process of development, children from such families are better trained to operate with words, including numbers, in comparison with children with lower indicators of cultural capital.

The same goes for bilingual children. For those children who used a second language at home, a closer relationship was found between phonological abilities and mathematics.

The results obtained can be of practical use. First, the development of phonological abilities can be taken into account when planning various developmental programs for mathematics in elementary school or in preparation for it. Secondly, in a situation where some programs are planned aimed at narrowing the gap in mathematical achievements between children with different SES, it should be taken into account that children with low SES have a lower level of phonological abilities and use phonological resources to a lesser extent. Accordingly, for such children, it is necessary to use visual methods of presenting information and instructions more often.

IQ

Authors of the study:

Yulia Kuzmina, Research Fellow, Center for Monitoring the Quality of Education, National Research University Higher School of Economics

Alina Ivanova, Junior Researcher, Center for Monitoring the Quality of Education, National Research University Higher School of Economics

Intern Diana Researchers HSE

Text author: Tarasova Alena Yurievna, February 19, 2019

All materials of the author

Education children School

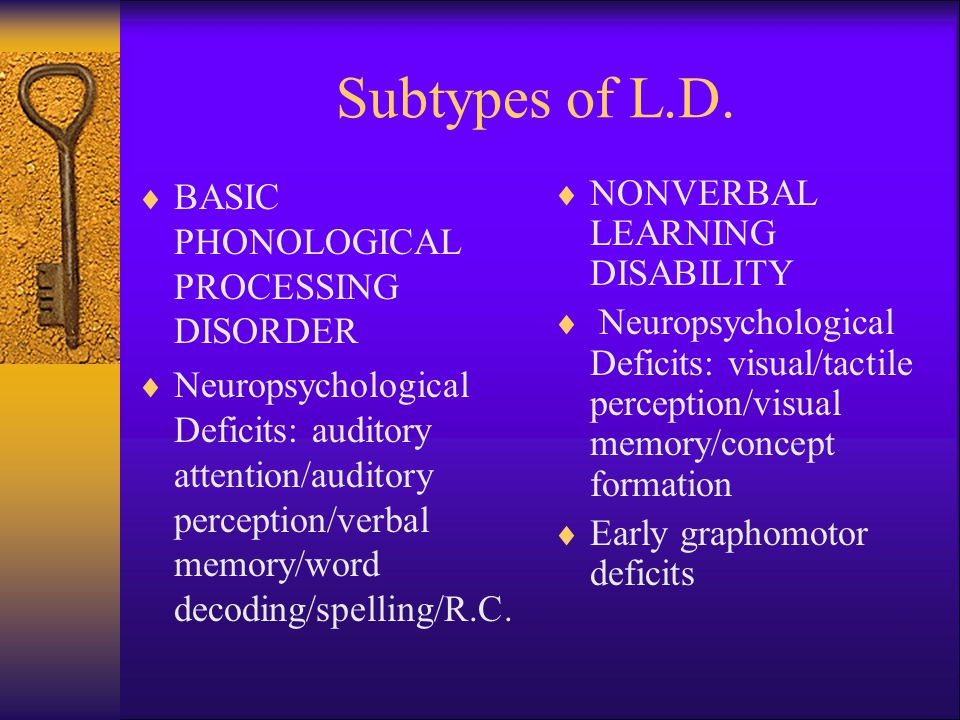

15 Learning Disorder Terms Parents Need to Know

If your child has a speech, reading, or learning or attention disorder, you may have come across these terms on social media, forums, or at professional appointments. .

.

Terms such as phonological awareness, auditory processing disorder, auditory accuracy, phonological memory…

Understanding these 15 terms will help you better organize the necessary assistance for your child:

1. Phonetics cha, yes) and the speech sounds they represent.

Phonetics is the foundation of reading and writing skills. Thanks to phonetics, the child decodes written words in the process of reading.

2. Phonemes

A phoneme is the sound of speech. When we speak Russian, we make 42 different speech sounds. But there are only 33 letters in the Russian alphabet. This is one of the reasons why Russian is difficult to learn.

3. Phonemic perception

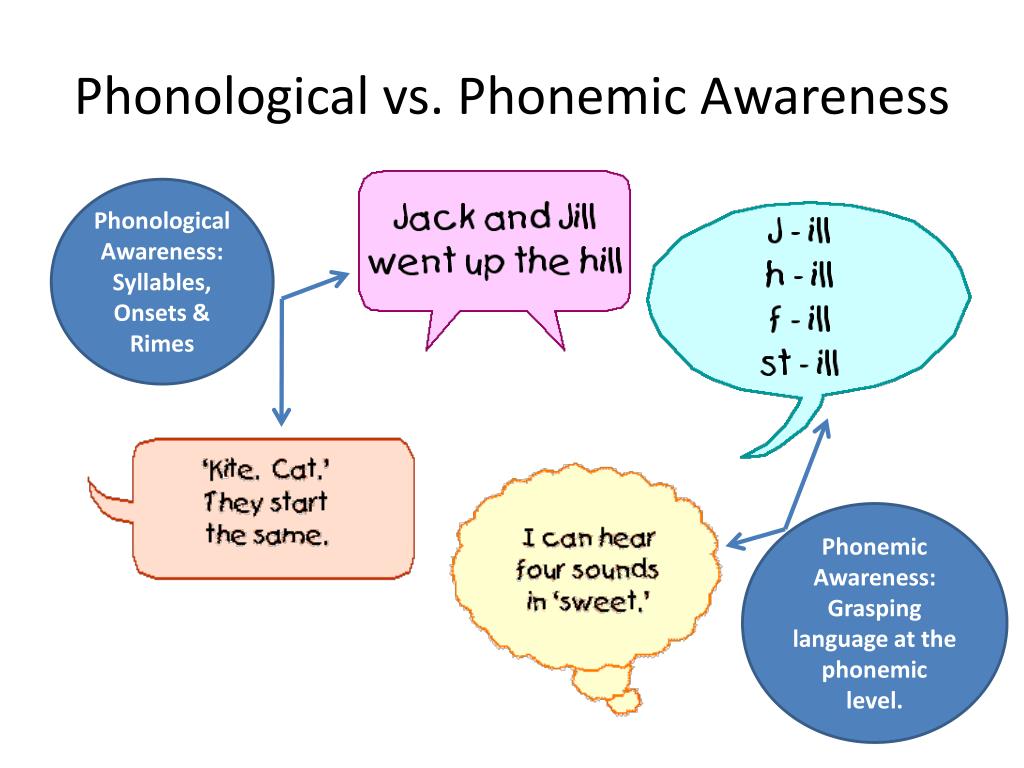

Phonemic perception is the ability to perceive individual speech sounds (phonemes) in words and work with them.

Learn how to develop phonemic awareness from an early age.

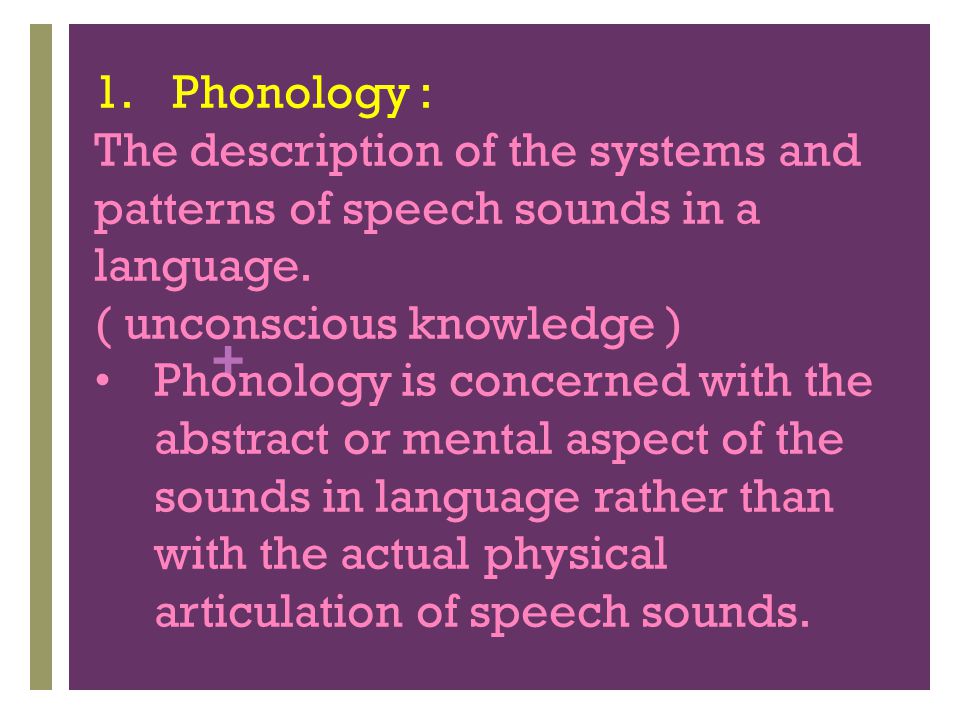

4. Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness is the awareness that words are made up of smaller parts (such as syllables and sounds).

The term includes a range of sound-related skills that a student needs to develop reading skills. As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. .

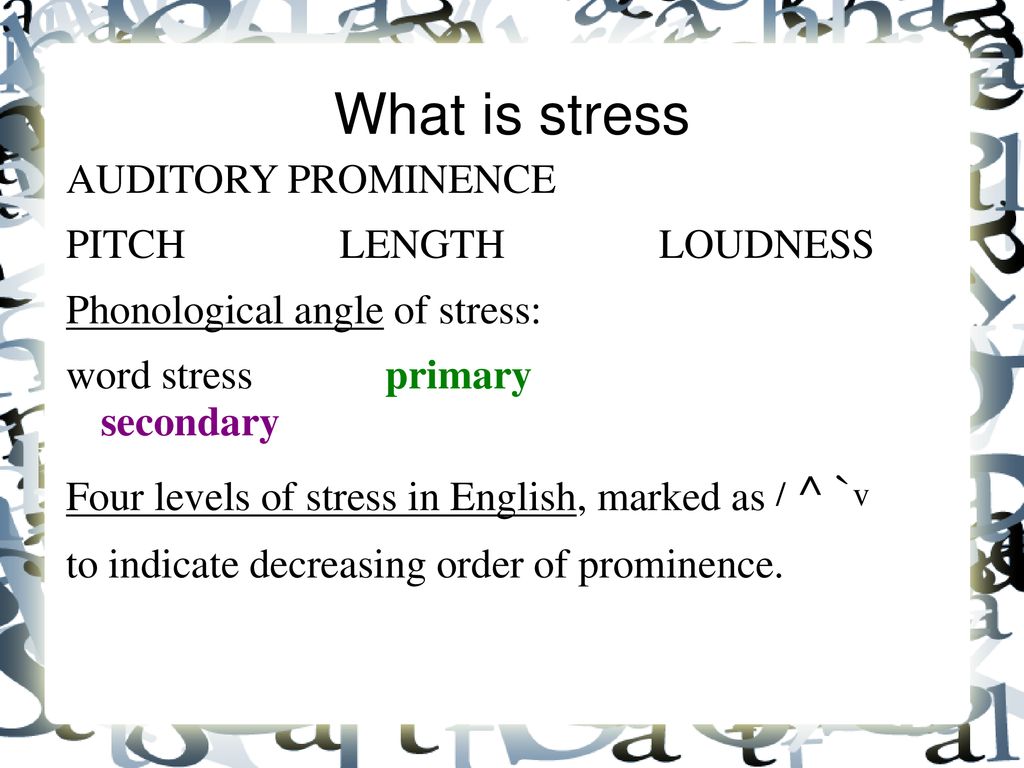

5. Phonological accuracy

Phonological accuracy refers to the ability to correctly distinguish between individual phonemes (e.g., in similar-sounding words that begin with the same sound) or other aspects of phonology (e.g., rhyming, number of syllables).

Phonological accuracy is key to listening and reading skills. This allows the student to make a clear distinction between similar-sounding words (e. g. "heron" and "saber" or "picture" and "basket"), including morphological differences that can drastically change the word's meaning and/or grammatical function (e.g. " known" and "unknown" or "inserted" and "exposed").

g. "heron" and "saber" or "picture" and "basket"), including morphological differences that can drastically change the word's meaning and/or grammatical function (e.g. " known" and "unknown" or "inserted" and "exposed").

The ability to quickly and accurately identify speech sounds is critical to learning the rules of phonetics and matching spoken language to text correctly.

A child with well-developed phonological accuracy will more easily develop decoding skills, understand word and sentence structure, develop vocabulary, follow instructions, and participate more actively in class work.

Well developed phonological accuracy helps in:

-

Understanding and following verbal instructions

-

Listening skills

-

Development of reading skills

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

6. Phonological fluency

Phonological fluency is the understanding that words are made up of different sounds and the ability to quickly and accurately identify and manipulate these sounds.

Phonological fluency is critical to learning to read. This allows the student to memorize sequences of sounds and manipulate them quickly and accurately. This makes it easier to both write words and decode them. The more effectively the reader is able to decode, the more of his cognitive resources (mental abilities) he can focus on understanding the text.

A student with good phonological fluency will also find it easier to learn new words while reading. When confronted with a new word, a student who can accurately pronounce the word is more likely to recognize and understand its meaning.

Well developed phonological fluency helps in:

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

-

Development of reading skills

-

Development of writing skills

7. Phonological memory

Phonological memory is the ability to retain speech sounds in memory. This is essential for spoken language and tasks such as comparing phonemes and making connections between phonemes and letters. It also helps with listening and reading understanding of sentences, as it allows you to remember the sequence of words in order.

This is essential for spoken language and tasks such as comparing phonemes and making connections between phonemes and letters. It also helps with listening and reading understanding of sentences, as it allows you to remember the sequence of words in order.

Phonological memory plays a key role in the development of oral and written language skills. This allows the student to:

-

Memorize and manipulate sound sequences

-

Associate spoken words with written ones

-

Memorize new words by determining their meanings

-

Remember the beginning of a sentence by listening to it to the end.

The ability to remember speech sounds is important for the correct understanding of sentences when changing the order of words in a sentence changes its meaning (for example, "The monkey bites the boy" and "The boy bites the monkey").

Accurate memorization of word order also contributes to the construction of accurate ideas about the structure of sentences and the acquisition of knowledge about syntax.

A student with a well-developed phonological memory develops phonemic perception and decoding skills more easily, knowledge of vocabulary and sentence structure is formed. Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc.

8. Auditory Processing / Auditory Perception

Auditory processing refers to what the brain does with the audio information it "hears". This includes various skills such as identifying and locating sounds, listening to background noise, and processing what is heard when the sound is fuzzy.

When a student manipulates the auditory information he has heard, but it doesn't sound right, this is called an auditory processing disorder (or auditory perception disorder).

This can happen if the child has difficulty understanding speech in background noise or has difficulty identifying where the sound is coming from. Or it could be a problem in distinguishing speech sounds that sound similar.

Or it could be a problem in distinguishing speech sounds that sound similar.

Find out 5 common hearing loss (HAI) myths!

9. Sequencing of audio information

Sequencing of audio information refers to the ability to identify and remember the order in which a series of sounds were presented. This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing.

Organizing audio information is critical to developing speaking and writing skills. The ability to identify and remember the order of sounds in words is important for recognizing subtle differences between words (such as "pot" and "top") and for developing phonemic perception and decoding skills.

A student who has a well-developed ordering of sound information understands and absorbs information better, develops better oral and written speech skills and concentrates attention. Such a student becomes an expert reader and a successful student.

See also: How do weak cognitive skills affect learning?

10. Listening word comprehension

Listening word comprehension refers to the ability to accurately identify words heard based on auditory cues alone, without the aid of visual or contextual cues.

Listening comprehension of words is critical to the development of spoken language and vocabulary, and therefore essential to the development of reading and writing. This skill allows the student to accurately and efficiently identify words in speech and helps him form a correct understanding of the information presented by ear.

A student with well developed listening comprehension will find it easier to follow instructions and participate in class discussions; it is easier to answer questions, complete tasks and remember information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader.

He will also find it easier to carry on a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

11. Hearing accuracy

Hearing accuracy is the ability to accurately identify differences between sounds and correctly identify sound sequences.

Accuracy in listening is the foundation of speech and reading skills. This skill allows the student to quickly and accurately identify and distinguish between rapidly changing sounds, which is very important for distinguishing between phonemes (the smallest units of speech that distinguish one word from another).

A student with well-developed listening comprehension will find it much easier to follow instructions and participate in class work; it is easier to remember questions, tasks and information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader. He will also be able to:

-

Read and write fast

-

Focus on verbally presented information

-

Maintain a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

g., /oy/, label each one, and identify each one in initial and final position *

g., /oy/, label each one, and identify each one in initial and final position *