When do kids learn sight words

When to Teach Sight Words, and When Not to…

Inside: This post helps parents and caregivers understand when it’s best to teach sight words. We also review which early literacy skills children should master before jumping into sight words.

We spent a lot of time working on sight words when my own children were small.

Yes, we played games and made the experience playful. But, in hindsight, I wonder if we should’ve been emphasizing other things.

The more I learn, the more convinced I am of this.

Lately, I’ve been teacher-geeking out, reading sight word research of Linnea Ehri, Marilyn Jager Adams, and others. But don’t worry – if that’s not your cup of tea, this post will make a handy cheat sheet for you.

I had a blog reader write to me recently asking if I had any suggestions for her 4-year-old who was struggling to learn sight words. I know she’s not alone, and so this post is for her and other parents and childcare providers with similar concerns.

What Do You Mean by “Sight Words”?

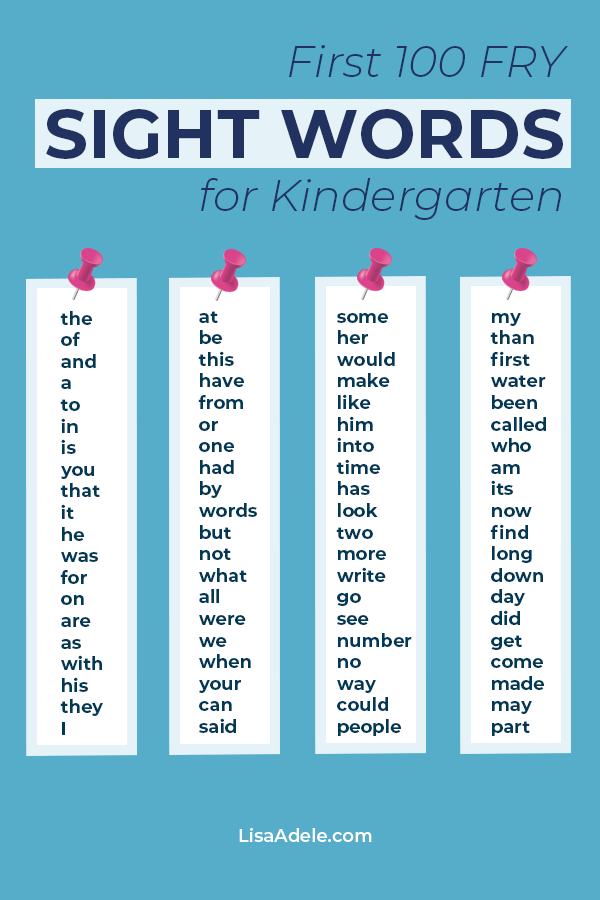

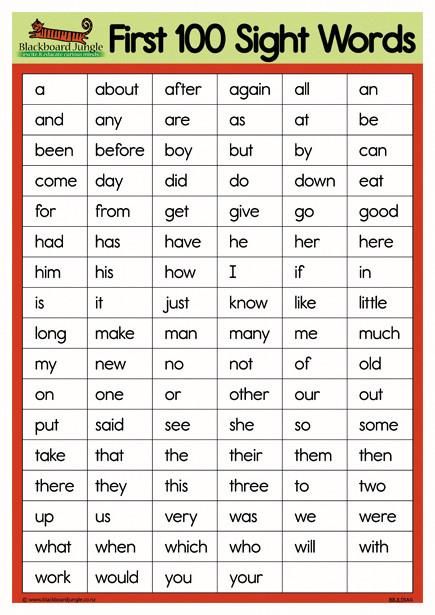

So, not everyone defines “sight words” the same way. Some educators reserve that term for words that kids can’t sound out with beginning phonics skills – such as the, one, and you.

Others broaden the meaning to also include high frequency words – meaning words children will encounter often as they begin reading, even if they’re easy to sound out – such as it, had, and run.

For both groups of words, kids must learn to decipher them at a glance. If they can’t read them quickly and fluently, they’ll lose the thread of meaning and struggle with comprehension.

(Yes, for you and me, just about every word is a sight word… more advanced readers generally only need to figure out a word once before internalizing it.)

So when speaking casually with parents and other teachers, I take sight words to mean any of the words that beginning readers need to learn to read instantly on sight – whether or not they’re ‘sound-out-able’.

When to Teach Sight Words

Not every child is ready for sight words at the same time, and that’s okay!

Here are a few ways to gauge if a child is ready to start learning sight words.

Age

The first (and most imprecise!) suggestion is age. If a child has developmentally been on track for other milestones such as crawling, walking, and talking, then odds are they will be ready for sight words at age 5.

In fact, in many states in the US, the curriculum for sight words does not start until Kindergarten, with the only “sight word” requirement for reading and writing in Pre-K being their own name.

However, age is just one reference point to use when assessing a child’s readiness for sight words.

Luckily, we have two more precise ways to tell if a child is ready for this step in the literacy process.

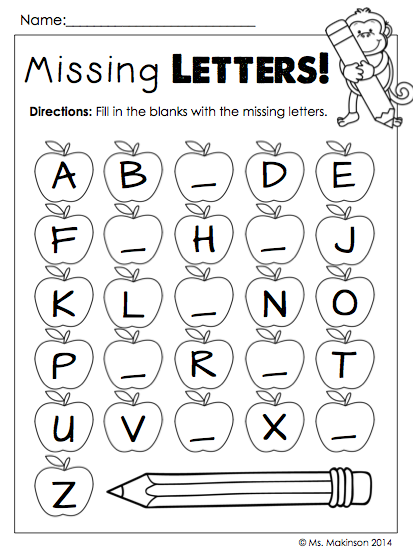

Letter Knowledge

Before teaching sight words, make sure the child can identify most letters and their initial sound.

There are fancy assessment tools, but you can also check letter and letter sound knowledge on the fly. Just hold up a flashcard with a letter, and see if the child can correctly tell you the letter name and sound it makes. If they can, then they’re on their way to being ready for sight words!

Just hold up a flashcard with a letter, and see if the child can correctly tell you the letter name and sound it makes. If they can, then they’re on their way to being ready for sight words!

However, I’m NOT saying you should drill children with flashcards. Please don’t. I’m all for working on letter knowledge in a playful, hands-on way, like this fun alphabet sensory play activity.

Then, when you think they’re ready, you can make a quick game out of testing them with flashcards.

RELATED: Phonics vs Sight Words: What Parents Should Know

Phonemic Knowledge

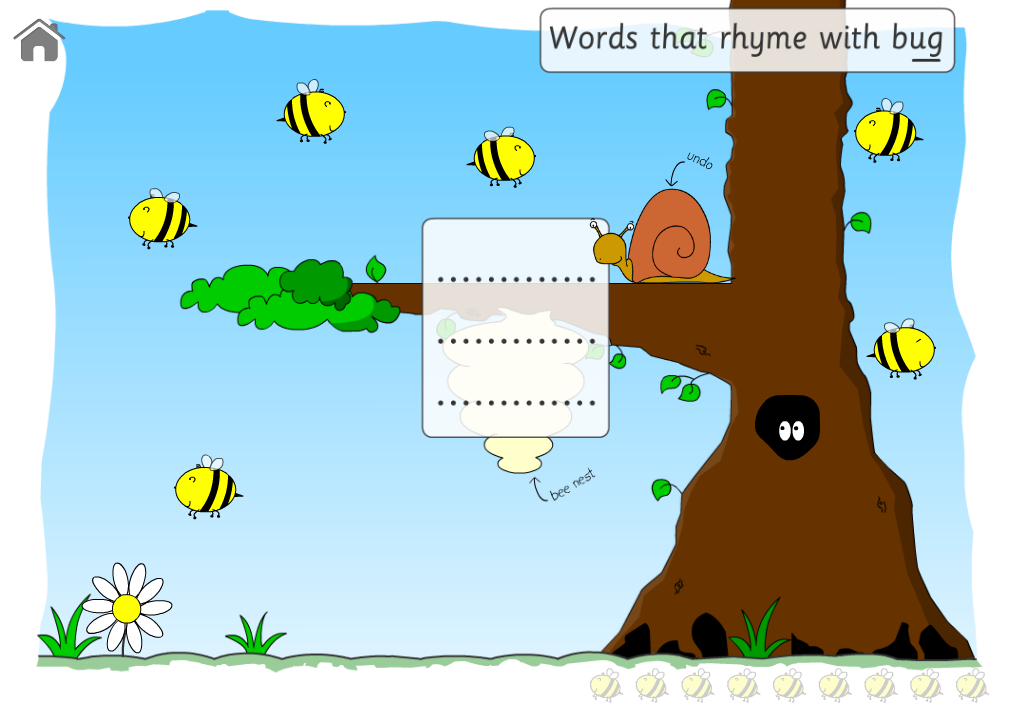

Believe it or not, being able to orally manipulate the sounds in words is an important foundation for teaching sight words too.

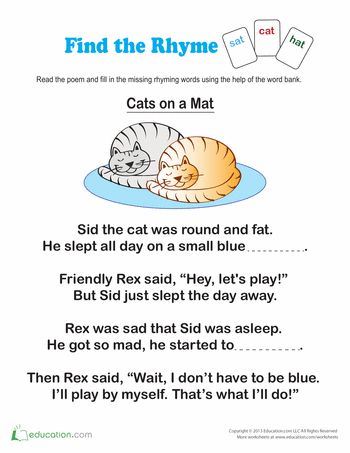

Children should be able to produce rhymes and segment words into their individual sounds, or phonemes. For example, when you orally give them the word “ship” they should be able to break it into 3 parts: /sh/ /i/ /p/.

(There are several steps before this. If you’re interested you can read up on phonological awareness.)

If you’re interested you can read up on phonological awareness.)

Again, there are formal tools to assess phonemic knowledge, but as a parent you can do an informal evaluation.

You can work on this skill by singing fun children’s songs like “Apples and Bananas” and Willoughby Wallaby Woo:

Reading aloud picture books with rhymes is also helpful. And there are so many good ones!

Reasons NOT to Teach Sight Words Early

I had to bite my tongue recently – actually my typing fingers – when an acquaintance posted that she was working on letters and sight words with her 3-year-old.

I was pretty sure her sweet boy wasn’t really ready to learn sight words.

If she’d asked me when to teach sight words, I would’ve had some advice for her. But I didn’t want to burst her proud mama bubble.

But I didn’t want to burst her proud mama bubble.

Instead, I’m just quietly hoping that she won’t experience any of these negative consequences:

Frustration

We want our children to love reading, and so to teach them something too challenging so early on might turn them off to the idea of reading forever!

Reading should always be fun, and if you sense your child is getting frustrated, take a break and the next time you read together, select a fun book that you know your child will love!

False Understanding

Conversely, even if your child seems to “get it,” this may not actually be the case. If you teach sight words too early you could be wasting time or even doing damage.

Your child needs foundational alphabetic and phonemic knowledge to truly grasp sight words and how they work. Research backs this up.

A child who can memorize sight words and a child who can understand why a sight word is what it is are two different levels of readers.

Just because a child can see a word and speak it back to you correctly doesn’t necessarily mean they have a deep understanding of the mechanics of literacy.

Slower Acquisition

Children who start working on sight words too early will tend to acquire those words more slowly. This is because they don’t have the mental literacy framework yet for more rapid learning.

Think of it this way: I could memorize words in Greek, but if I didn’t understand the Cyrillic alphabet it would still be really hard for me to read similar words (of course, it would help if I knew anything about their language beyond the names of hurricanes this extra-long storm season!)

Your time will be better spent building a strong foundation of early literacy skills and nurturing a love of books.

And relax! Research shows that teaching sight words in preschool doesn’t even necessarily have an impact on achievement by the end of kindergarten.

Why You SHOULD Teach Sight Words

All of this isn’t to say that you should ignore sight words forever. You shouldn’t. They really are important to learn when a child is ready.

You shouldn’t. They really are important to learn when a child is ready.

By learning sight words your child will be able to read faster, more fluently, and gain confidence in their literacy skills. Plus, they won’t stumble through common words that can be tricky for early readers, such as the silent “e” at the end of “like.”

Overall, sight words are a foundational must for beginner readers!

I hope this article helped you understand when the best time is to begin working on sight words. If I had known when my kids were small what I know now, I would have spent our early sight word time singing rhyming and segmenting songs together, and setting up lots of playful letter sound activities.

I hope you’re able to do the same.

Happy Teaching!

Heather

When to teach sight words

Is your little one getting ready to enter preschool or kindergarten? Then this is a great age to try teaching them sight words!

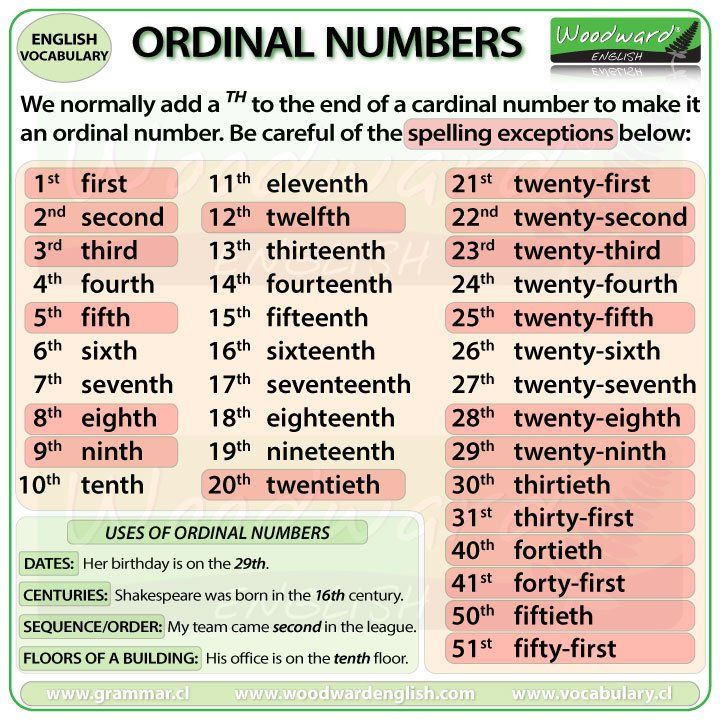

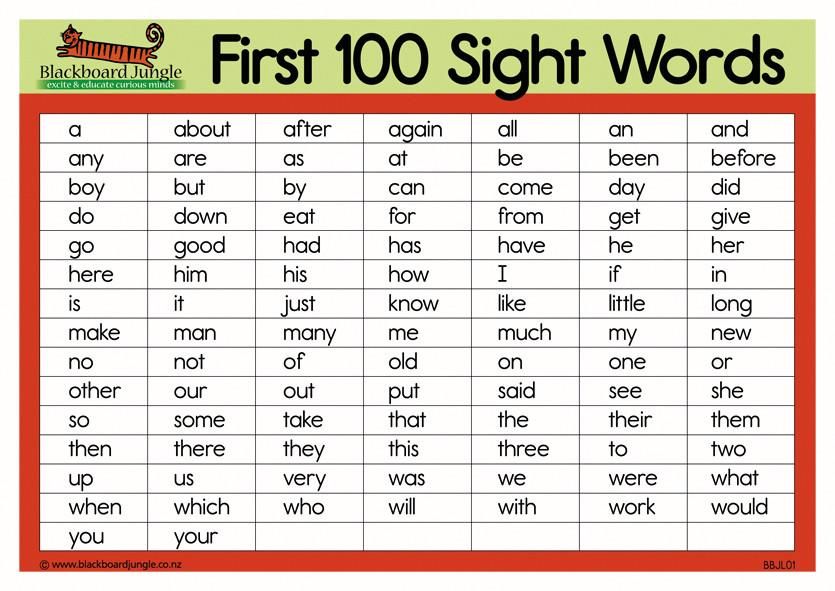

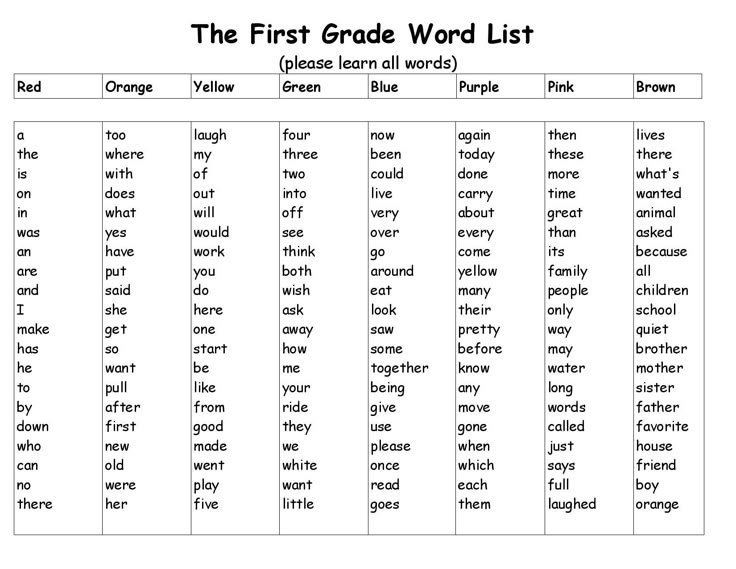

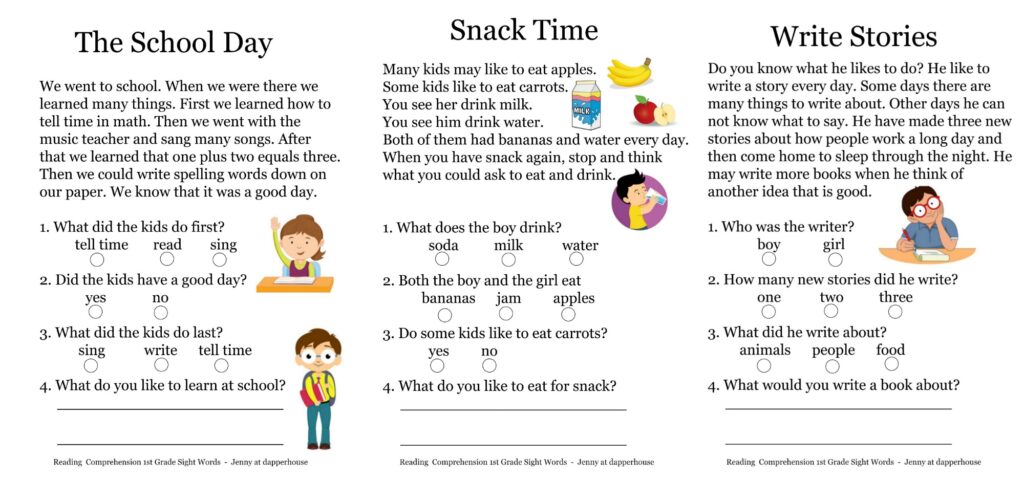

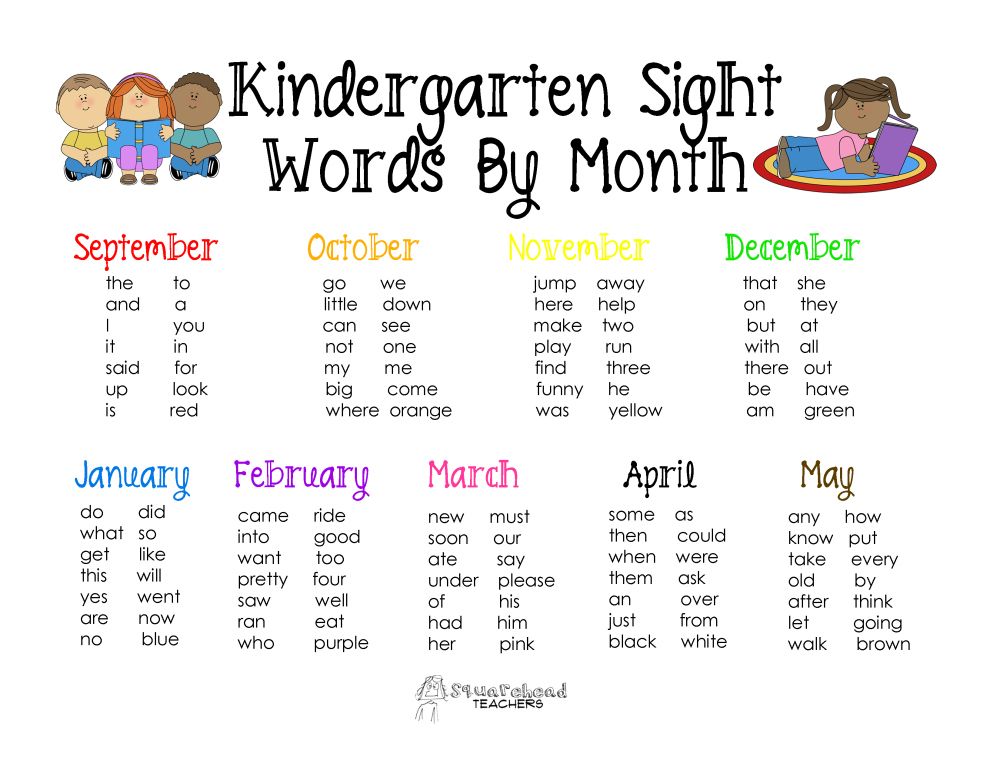

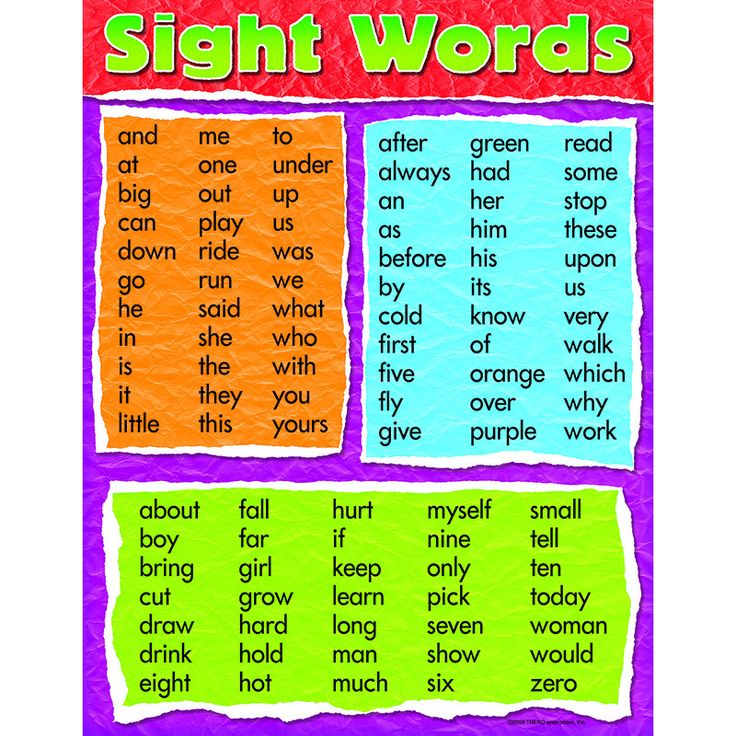

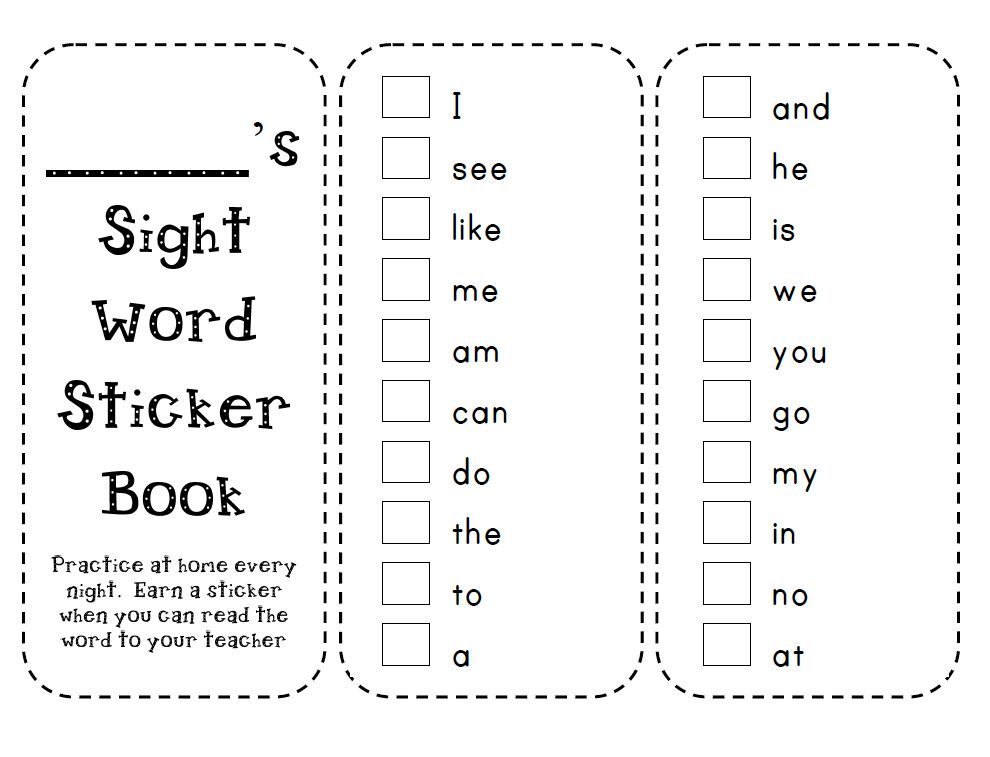

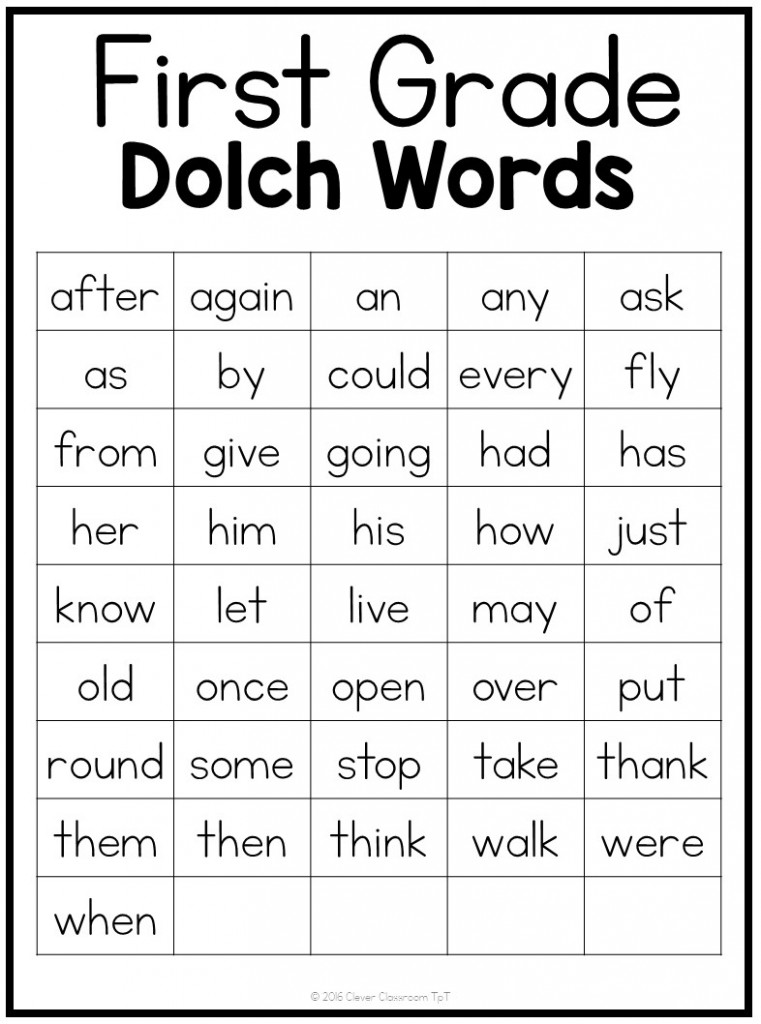

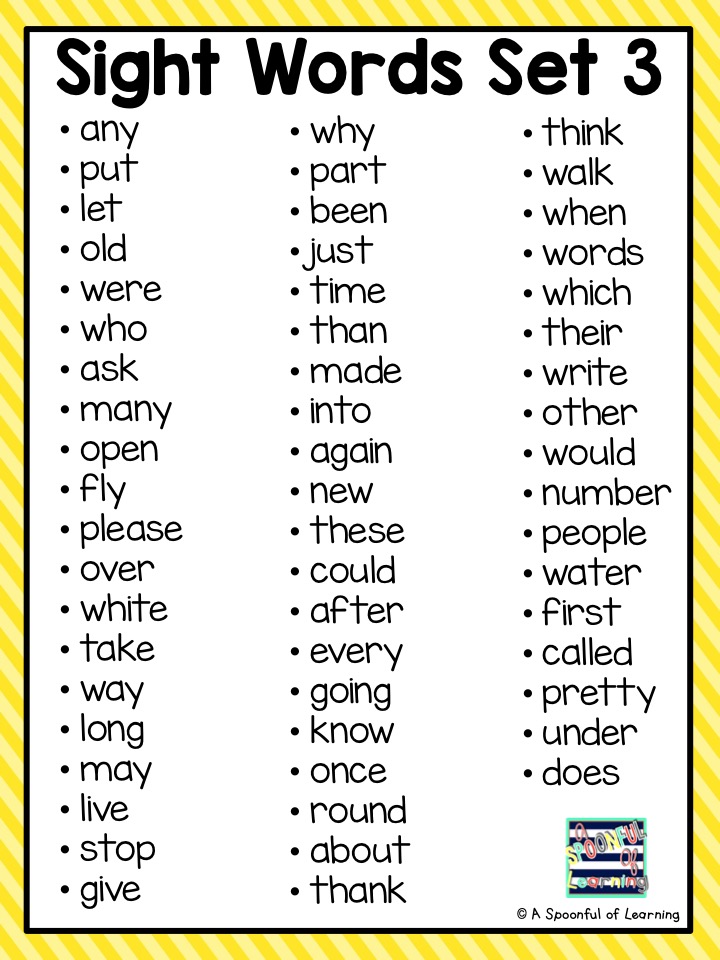

Sight words are most commonly introduced at the preschool level when children are approximately four years old. A preschooler’s first 40 sight words generally include small numbers (one, two, three), primary colors (red, blue, yellow), and basic pronouns (me, we, you). By Kindergarten, at approximately five years old, many kids are expanding their sight word recognition to words for higher digits, more colors, more pronouns, some prepositions, and common adjectives.

A preschooler’s first 40 sight words generally include small numbers (one, two, three), primary colors (red, blue, yellow), and basic pronouns (me, we, you). By Kindergarten, at approximately five years old, many kids are expanding their sight word recognition to words for higher digits, more colors, more pronouns, some prepositions, and common adjectives.

Wondering exactly when to introduce your child to high-frequency words? Keep reading!

When to teach sight wordsWhat are sight words?

Sight words are the words that you will find on almost every page of a book. These sight words – or “High-Frequency Words” are the ones that your child will come across when they read almost any text. From books to worksheets and letters to Santa, these words are found everywhere. So, if your little one has a head start on learning how to read them, they will be set up for success as they enter kindergarten!

Words like a, I, me, my, see, and, you, and the are examples from the Pre-K level.

A great resource to check out is Dolch Sight Words, which lists the words by age, group, or alphabetical order. They’ve also got lessons, games, and flashcards, too!

Why are they important?

According to Dolch, sight words from the Pre-K level to 3rd grade make up 80% of the words that you will find in most children’s books. This tells us that in order for your child to successfully read children’s books, they’ve got to have a solid understanding of sight words.

Another bonus is that once your child has mastered reading sight words, they can focus on learning the other words in their books. By not having to focus on every single word, their reading becomes more natural, and their reading fluency increases.

Plus, teaching high-frequency words helps beginning readers recognize common words while increasing essential phonics skills that they will use as they continue to practice literacy skills in school. Enhancing their phonemic awareness builds a strong foundation for early readers.

When to start teaching sight words

I want to stress one thing first: If your child doesn’t pick up on reading sight words right away, that is okay. Literacy is a huge part of Kindergarten and they aren’t necessarily going to fall behind if they start the year not knowing some (or any) of these words! Their teachers are equipped with the skills and resources to teach them effective phonics instruction and have the support to assist struggling readers, too.

But, if your child expresses an interest in books and a desire to read, why not try teaching them sight words? By learning these with you, you are promoting a love of literacy that will stick with them for a long time to come.

Preschool

A good time to start introducing your child to these words is at the age of around 4. I say around because some may show an earlier interest in reading and others later. Since this is the age where most children are introduced to learning via pre-k, and will soon be entering the school system, now is a good time to give it a try!

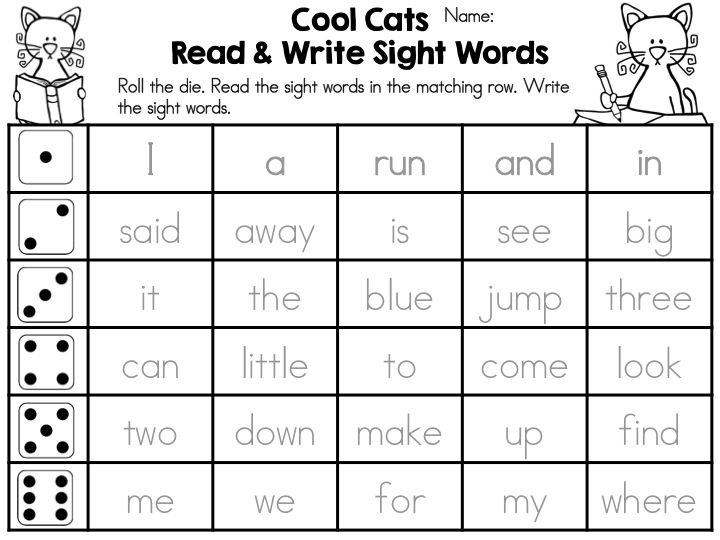

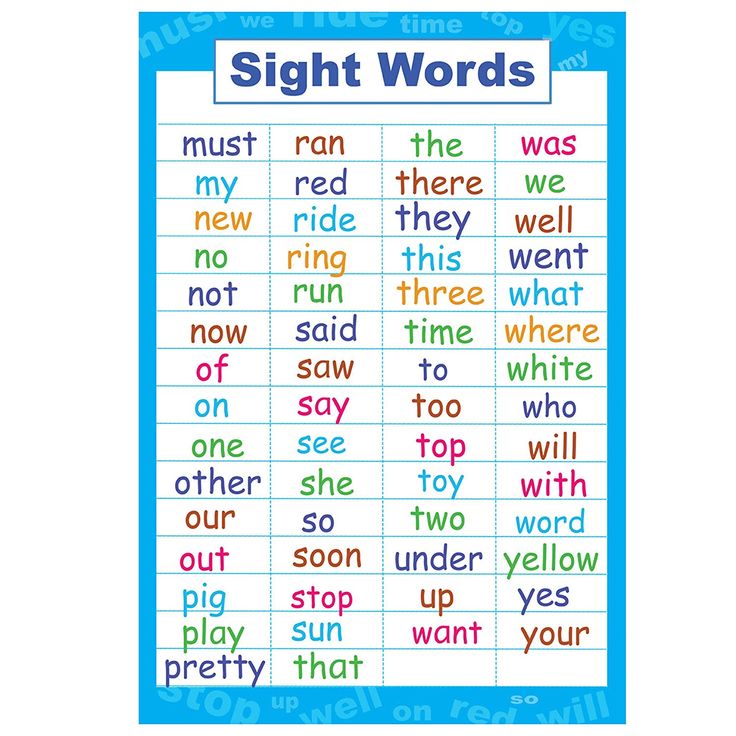

Here’s a list of the sight words to expect at preschool level:

a, and, away, big, blue, can, come, down, find, for, funny, go, help, here, I, in, is, it, jump, little, look, make, me, my, not, one, play, red, run, said, see, the, three, to, two, up, we, where, yellow, you

The list above is directly from Dolch’s list, but if you click this link there’s a PDF with all 40!

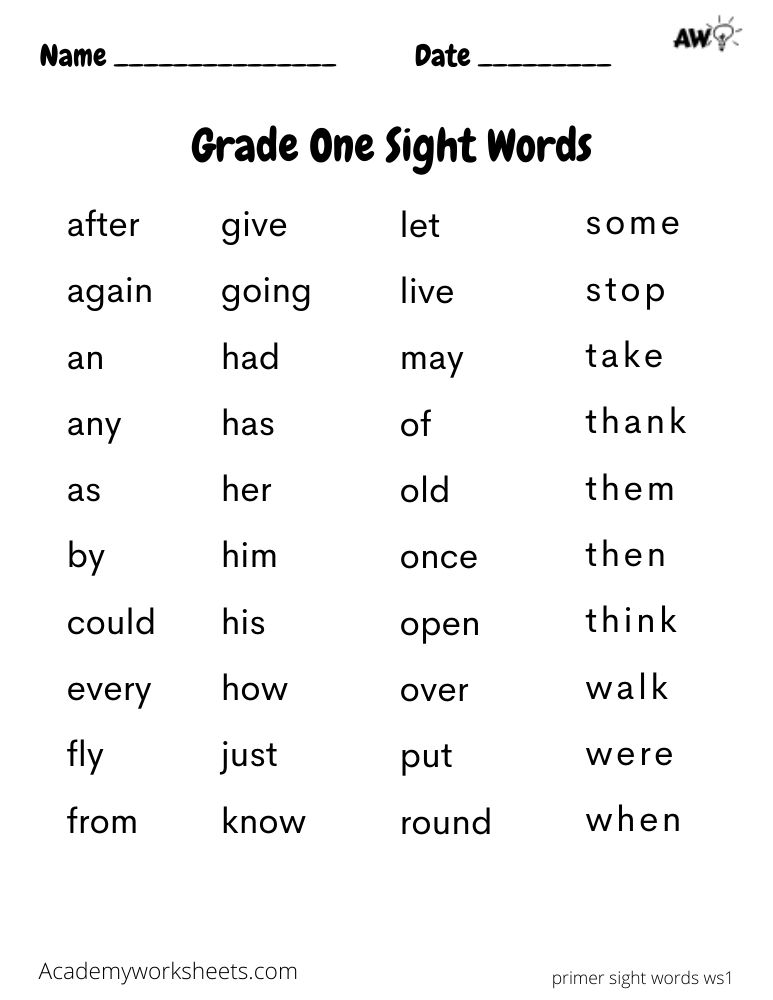

Kindergarten

If your child is already at kindergarten age and you haven’t yet started sight words, don’t fret! You can always start now!

At Kindergarten age, you can expect sight words such as:

all, am, are, at, ate, be, black, brown, but, came, did, do, eat, four, get, good, have, he, into, like, must, new, no, now, on, our, out, please, pretty, ran, ride, saw, say, she, so, soon, that, there, they, this, too, under, want, was, well, went, what, white, who, will, with, yes

Again, those are from Dolch’s list! If you want to see the full 52, use this PDF.

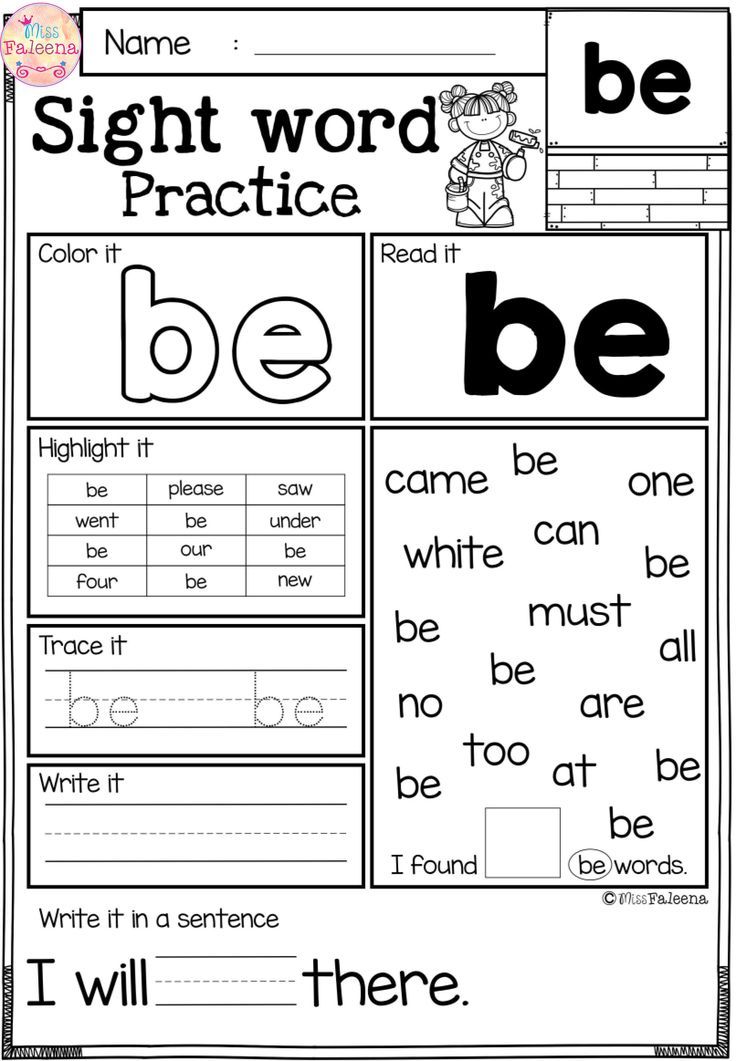

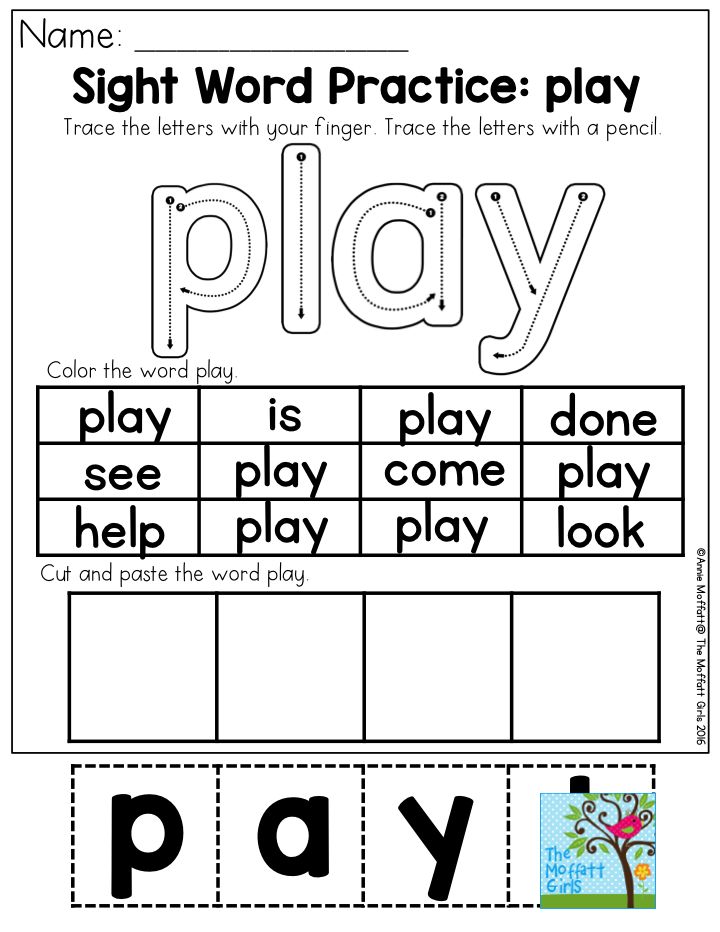

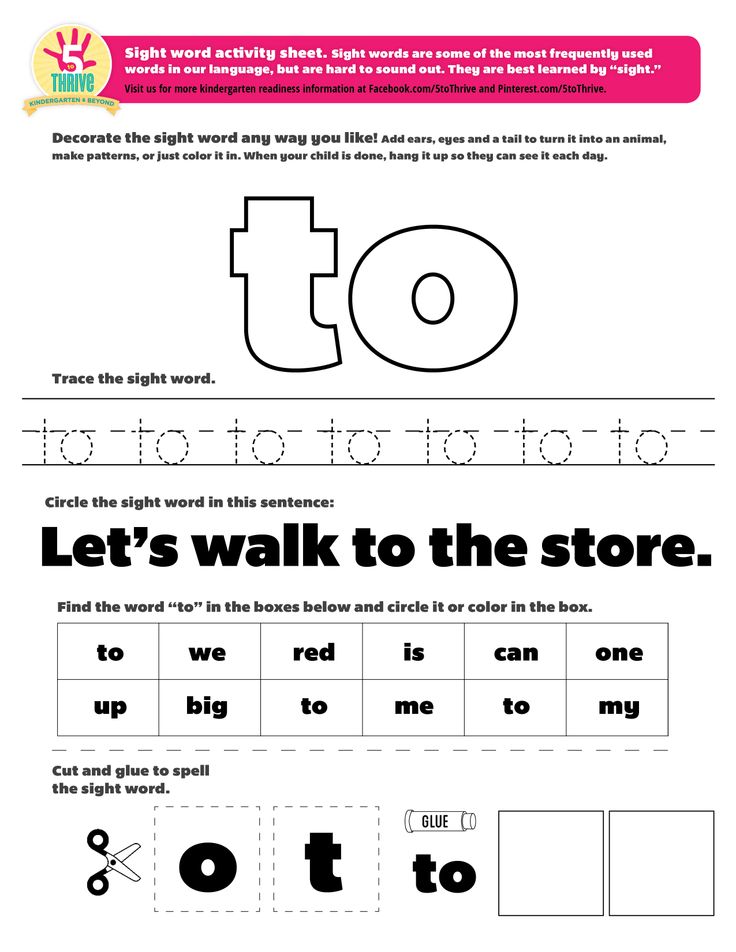

How to teach sight words

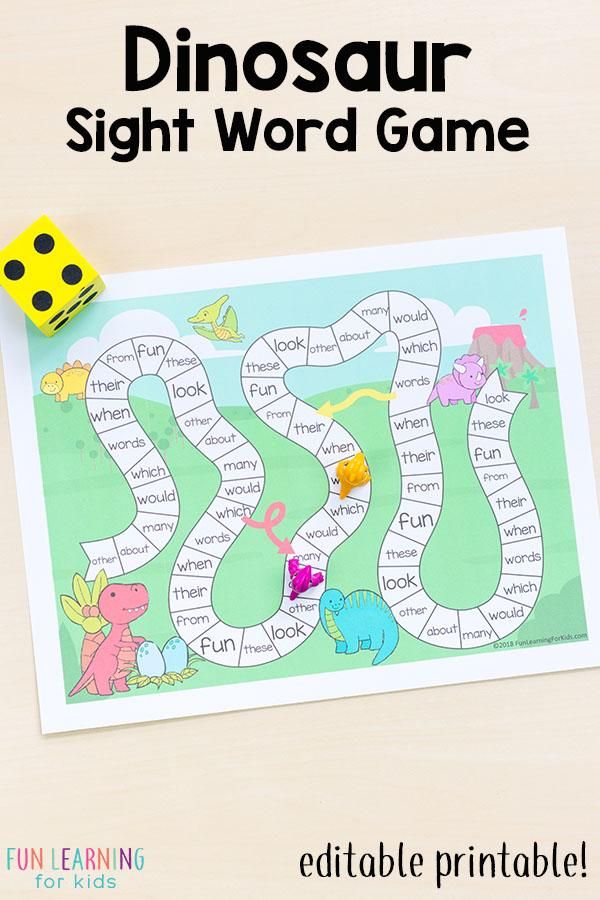

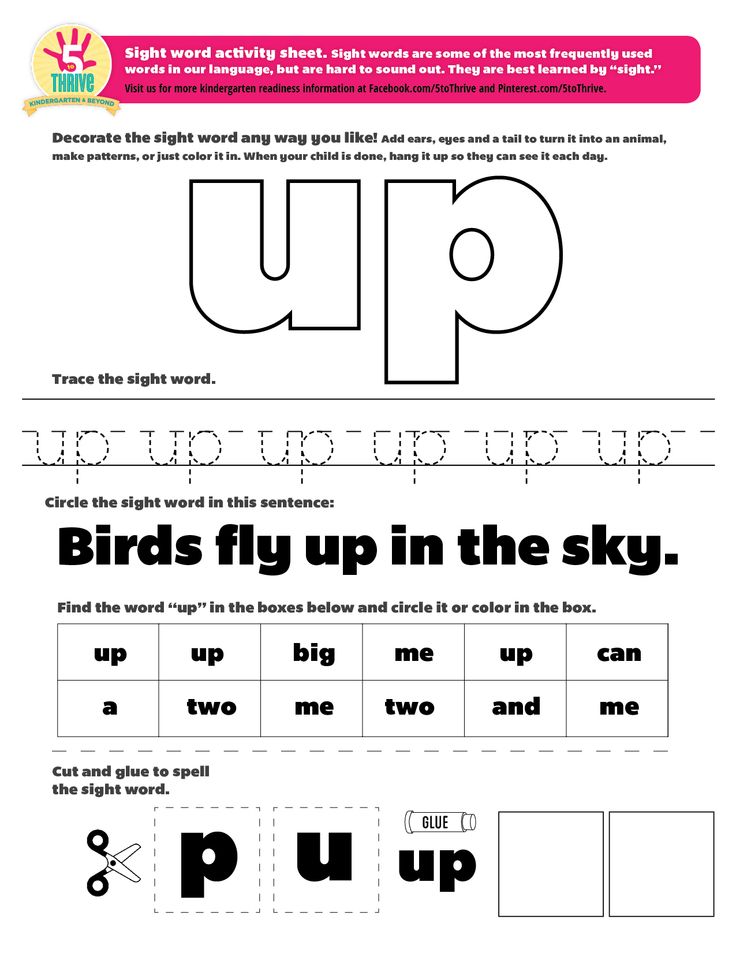

I’ve got a whole post on this (linked here), so I won’t get into deep detail here. What I will say, though, is that keeping reading a low-stress and highly enjoyable activity will promote a deep love of reading in your children. Don’t focus too much on how many words they know or how well they read, especially at such a young age! The important thing is to make reading a positive experience.

The best thing you can do for your emergent readers is to teach them that reading is not only important to learn, but that it’s fun too. By using a variety of resources and a range of book types, you’ll surely find something that will get them excited about reading while letting them explore topics they’re interested in!

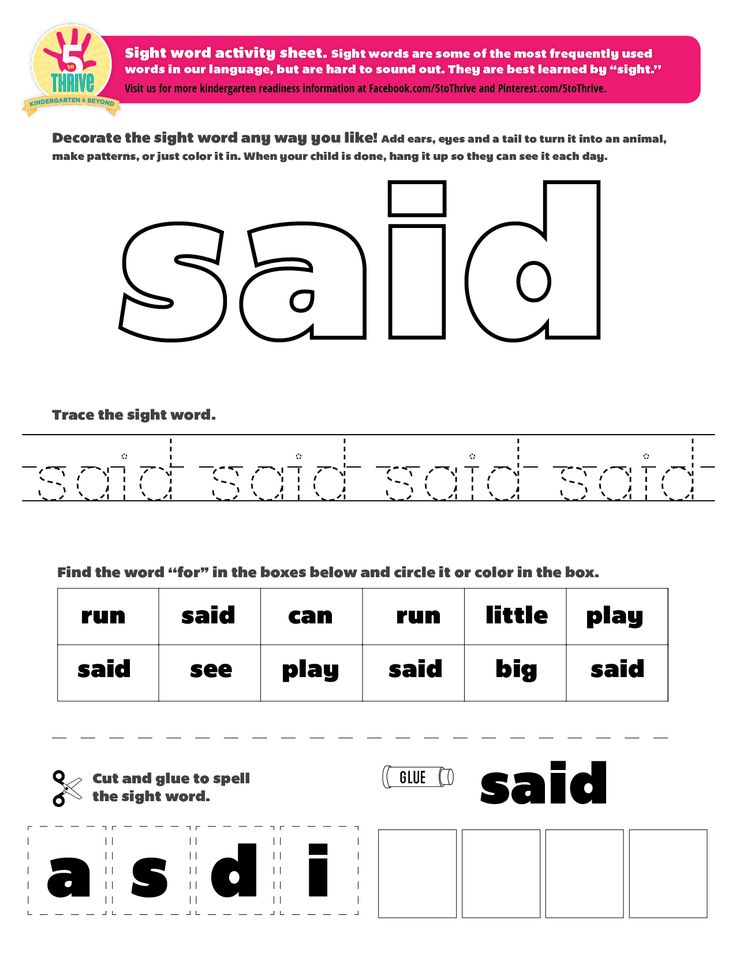

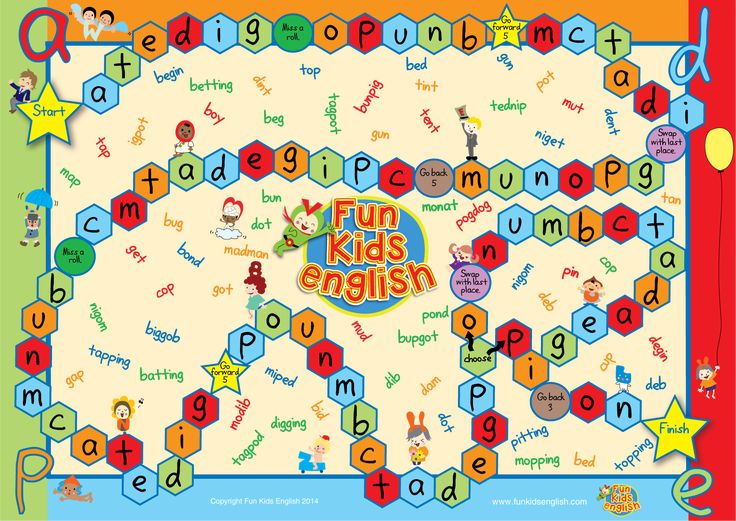

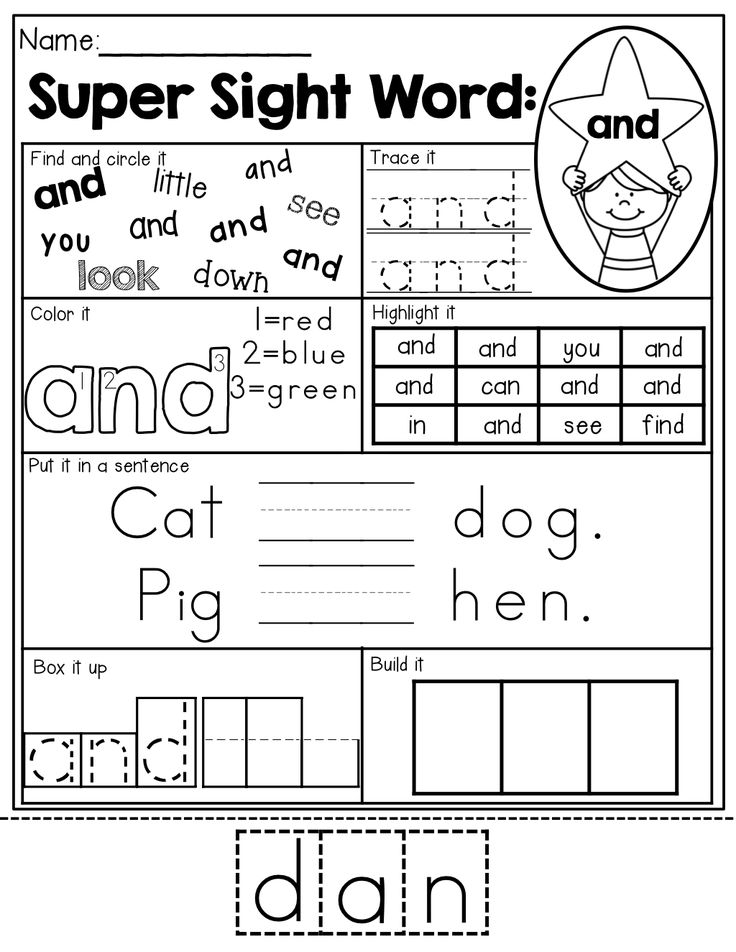

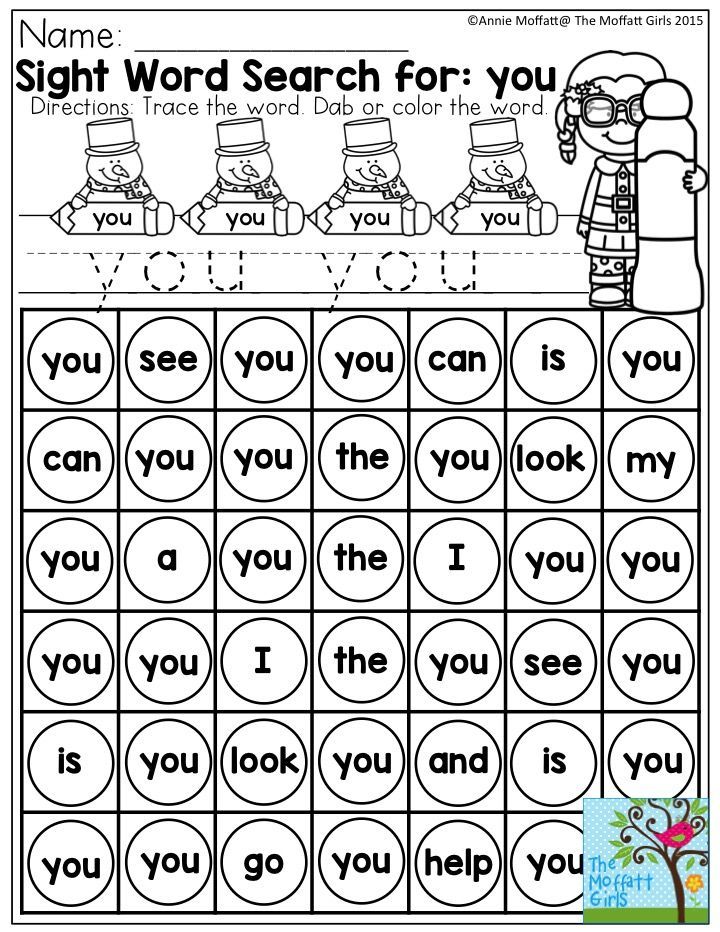

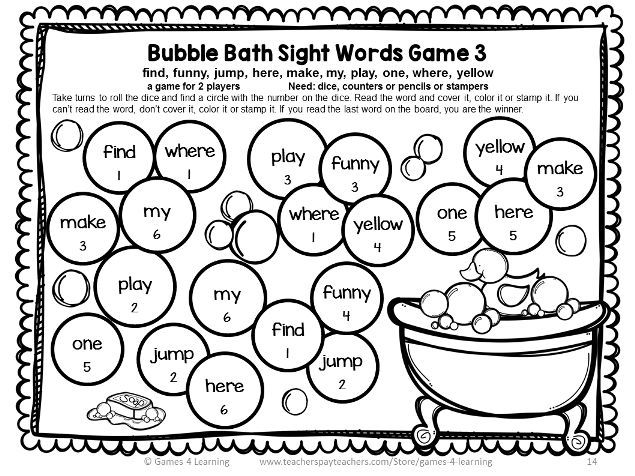

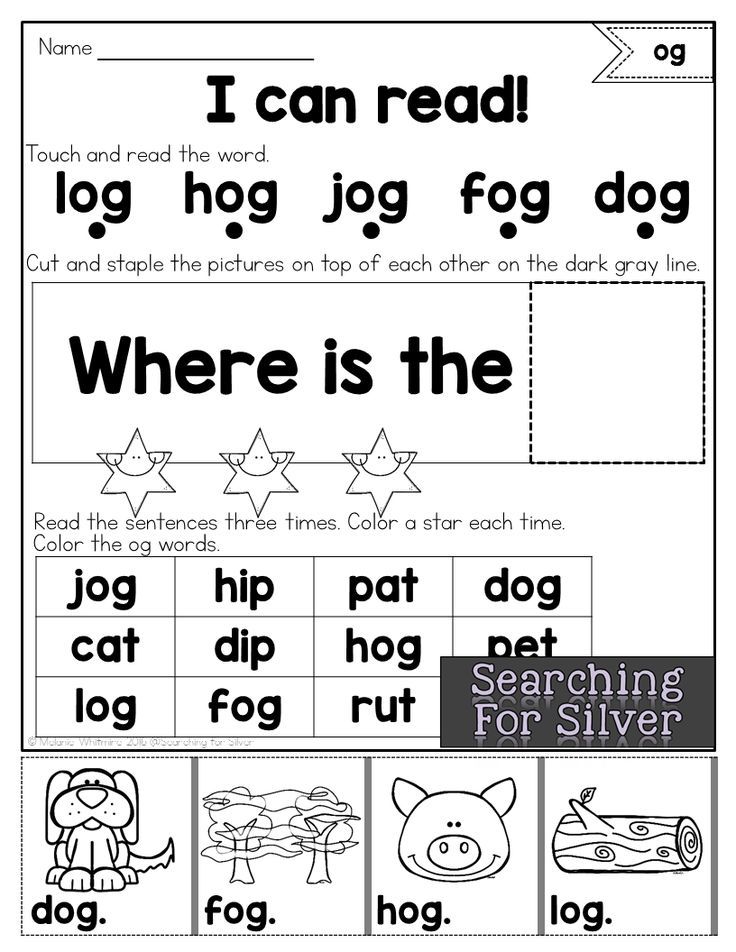

Try to keep things fun – Asking your kiddo to memorize lists of words isn’t a super effective way of teaching reading. Finding engaging activities will still boost their reading skills! Helping them learn sight words and practice how to recognize phonics patterns through fun games and activities will create more memorable phonics lessons.

Conclusion

While many parents want their children to have at least a little bit of experience reading and writing sight words, it’s all about meeting your child where they’re at. If they are showing interest in reading and writing, then it’s a good time to start learning sight words with them! Introducing sight words from the Dolch list will give them a strong literacy foundation as they continue to develop their skills in school.

Children learn best when they’re having fun, so be sure to keep the activities fun, light, and exciting for your young readers. Rather than just asking them to memorize words, find which method works best for them and offer lots of that type of resources. They may enjoy music-based learning, games, or worksheets, for example!

Whichever resources you provide, it’s important to be consistent in practice – Frequently writing words will develop muscle memory, and consistent practice reading will enhance their letter knowledge and ability to recognize sight words as they explore language.

Resources

Looking for more literacy-related posts? Check out some of these!

- Letter tracing ideas: Ways to make writing fun!

- Alphabet letter tracing worksheets from A-Z

- Sight word sentences for emergent readers

- The best books for a 1-Year-Old: Types and titles

- What is a board book?

Reading and writing with young learners

Reading sight words are just one of the many things your child will learn when it comes to reading and writing. Check out our literacy category for more articles about these topics (and teaching tips/ideas, too!).

At what age should a child speak?

Reviewer Kravtsova Elena Mikhailovna

93980 views

November 23, 2021

Speech is one of the important skills of a child, and its formation begins long before the baby speaks on his own. The baby perceives the speech of the parents and the adults around him, imitates it and subsequently relies on the acquired experience. When should a child start talking and how to help him?

The baby perceives the speech of the parents and the adults around him, imitates it and subsequently relies on the acquired experience. When should a child start talking and how to help him?

Standards for the development of speech in children

The development of speech occurs gradually. Each child is individual, so it can either be ahead of the age norms or a little behind. It is believed that girls start talking earlier than boys, and parents of boys do not always understand whether to worry or just wait. The reason is in physiological features: the maturation of some brain structures of girls is faster. Because of this, they improve their vocabulary at an early age. But not only the number of words, but also other signs are important for assessing the speech development of the child. They are universal for both boys and girls.

The speed and quality of speech development in children are individual, and the normative boundaries are conditional. To understand that everything is in order with the baby, the pediatrician will help. For a preliminary assessment of the development of speech, one can focus on the norms described by the Soviet psychologist Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky [1] .

To understand that everything is in order with the baby, the pediatrician will help. For a preliminary assessment of the development of speech, one can focus on the norms described by the Soviet psychologist Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky [1] .

Up to year

In the first months of life, the baby listens to his parents and the adults around him. He distinguishes the voices of people who are talking to him, turns his head towards the sound. First, the child masters vowel sounds, then by the age of three or four months, consonant sounds appear, and the baby begins to walk.

At the age of 6-12 months, the child imitates the sounds of adult speech more actively. Babble appears - the baby pronounces the same syllables, for example, “ma-ma-ma”, “pa-pa-pa”, “dya-dya-dya”. At about ten months, babies get used to responding to their name. By the age of a child, the first short meaningful words appear (“on”, “give”, “mother”). Vocabulary ranges from 3 to 20 words. In addition, a baby of this age responds correctly to requests to show or give something (performs or shakes his head negatively).

In addition, a baby of this age responds correctly to requests to show or give something (performs or shakes his head negatively).

One to two years

In a year, the baby repeats words that he often hears, adjectives appear in speech. The child uses sounds and gestures to attract attention, skips or replaces complex combinations of sounds, adapting speech for himself, for example: “bad - groin”. The kid moves more, begins to move independently and accumulates knowledge about the world around him. Vocabulary is actively replenished: up to one and a half years the child uses 30-40 words, closer to two years - 300-400. In girls, by the age of one and a half, in boys, by the age of two, phrasal speech begins to form. It arises and is primarily used for questions and the expression of simple needs ("Give me a drink").

Two to three years

At this age, the ability to speak in sentences of 2-3 words is actively developing. The child begins to use pronouns and prepositions. His speech becomes more understandable to adults, he can fulfill their two-part requests, for example: "Take your toy and give it to me." Vocabulary is replenished by 100 words per month. At two or two and a half years, the baby asks questions: “Why?”, “Where?” etc.

His speech becomes more understandable to adults, he can fulfill their two-part requests, for example: "Take your toy and give it to me." Vocabulary is replenished by 100 words per month. At two or two and a half years, the baby asks questions: “Why?”, “Where?” etc.

Three years

At three years old, a child actively communicates with adults and peers using simple sentences. He can explain his desires in words. The kid begins to use unions and uses almost all the main parts of speech, including generalized names (“animals”, “things”, etc.). At the same time, the child may still make sounds indistinctly. The kid likes to listen to familiar fairy tales and poems. He remembers the text well and reproduces it. Vocabulary is replenished every day [2] .

How to help a child speak

When children begin to speak the first words, they themselves really like it. The main way to help your child talk is to communicate with him as often as possible. In infancy, the baby understands speech on an emotional level, so you need to speak with him expressively. All activities associated with it - bathing, massage, feeding, etc. - accompany with emotionally charged words. Call the baby by name, pronounce the names of things, talk about what the child himself does and how well he does it, and also pick up and repeat all the sounds that he makes.

In infancy, the baby understands speech on an emotional level, so you need to speak with him expressively. All activities associated with it - bathing, massage, feeding, etc. - accompany with emotionally charged words. Call the baby by name, pronounce the names of things, talk about what the child himself does and how well he does it, and also pick up and repeat all the sounds that he makes.

As they grow older, it is better to use short and clear sentences so that the child can observe the movement of the lips and apply knowledge in his speech. You need to maintain a conversation with the baby, ask him questions and try to have a long conversation.

Read books and sing songs. You can read a book to your child and show the characters in the pictures. They will attract his attention, and auditory perception will help memorize new words. Joint learning of new songs and short rhymes develops the speech apparatus, and also strengthens the bond with the baby.

Develop fine motor skills. Fine motor skills - this is the performance of small movements with hands, fingers and toes, for example: sorting through cereals, playing with beads and buttons. The centers of the brain responsible for motor skills and speech are located next to each other, so when motor skills are stimulated, speech develops faster.

Develop vocabulary. You can show and name the surrounding objects to the child: at home, in the park, at a party. The meaning of objects should be explained in simple terms. So the child will expand knowledge about the world around him, learn new words and will learn to speak faster.

Abandon body language and mangling words. It is better for adults to refuse to distort words, because the child learns to speak on the basis of the speech that he hears around. If the baby replaces words with gestures, you can pretend that they are incomprehensible. This will encourage him to speak. You should not bring the child to crying or hysteria. It is worth acting gently - asking leading questions, pronouncing words one after another.

You should not bring the child to crying or hysteria. It is worth acting gently - asking leading questions, pronouncing words one after another.

Games for the development of the articulatory apparatus

Musical games help the child to develop speech breathing and provide an opportunity to develop a long pronunciation of vowels and a clear pronunciation of consonants. The following activities may help:

- songs with repetition of syllables, for example: “Pee-pee-pee-food! And only then - wake up-pi-nutrition ”;

- toys that reproduce the sounds of animals - they should be repeated together;

- musical instruments in the game: you need to ask the child to say the name of the instrument and repeat the sounds it makes.

Finger games are the image of any rhymes or stories with the help of fingers. Such activities help to quickly engage the speech center. In finger games, various hand movements are used - raising and lowering the palms, clapping, as well as bending and unbending the fingers. Familiar to everyone since childhood, “Ladushki, patty” and “Geese flew” are perfect for such exercises. More examples of finger games in the article.

Familiar to everyone since childhood, “Ladushki, patty” and “Geese flew” are perfect for such exercises. More examples of finger games in the article.

Articulatory gymnastics is aimed at developing the mobility of the speech organs. It includes exercises for the tongue, cheeks, lips and facial expressions. Suitable for the following classes:

- Grimaces: standing together in front of a mirror, smile broadly, show tongue, puff out cheeks.

- Simple games for breathing: blow off the candy wrapper from the palm of your hand, blow soap bubbles, blow on a dandelion.

- Games with the tongue: hide and show the tongue, make circular movements with the tongue like a clock hand, try to reach the tip of the nose with the tongue.

When to see a doctor

The development of speech in each child occurs individually, and it does not matter at what age or at how many months mom or dad started talking. In order to timely detect the backlog, you need to regularly undergo scheduled examinations with a pediatrician.

If during the next appointment the doctor reveals signs of a speech disorder, you should contact a neurologist and a speech therapist. Specialists will draw up a correction plan. It is important that parents actively participate in the treatment process and provide support to the child - the effect of the classes will depend on this.

Advice to parents

List of sources

1. Vygotsky L. S., Psychology of child development, M: Publishing House of Meaning, Publishing House of Eksmo, 2004. - 512 p. (Series "Library of World Psychology")

2. Stages of development of the child's speech and the reason for contacting a specialist L. G. Sokolova, FMBA of Russia

Reviewer Kravtsova Elena Mikhailovna

Psychologist, child and adolescent

All expert articles

How a small child learns new words - Child development

Preschoolers have a hard time learning new words. They hear unfamiliar words in a new environment. How do children learn what exactly an unfamiliar word means?

They hear unfamiliar words in a new environment. How do children learn what exactly an unfamiliar word means?

Even though a new word can mean almost anything, children learn new words surprisingly well. Shortly after a child speaks his first words, he builds up his vocabulary at an astonishing rate, absorbing the new words like a sponge.

How does he do it? This question has been wrestling with learning and development scientists for many years. Such progress in mastering new words seems so huge that it is like magic.

However, modern technologies allow us to take a different look at the process of speech development of children. It would be easier to understand this progress in the speech development of children if we could look at the world around us from the point of view of a child: having the same features of the body, undeveloped motor skills and limited mobility.

This can be achieved by putting a mini camera on the child's head and leaving it on for a while. Thanks to this, it is possible to see the world around him through his eyes.

Thanks to this, it is possible to see the world around him through his eyes.

American researchers, using such a camera, came to interesting conclusions. It turned out that the child's world was very dynamic and changeable. Many objects remained in the child's field of vision for only a second or a fraction of a second. But against the background of such dynamics, episodes stood out that were not like the rest. There was only one object in the child's field of vision, which was closer to the child and, accordingly, visually larger than the others.

In connection with this, researchers have a question: are the episodes when certain objects are close to the child optimal for memorizing the names of these objects?

To answer this question, scientists conducted an experiment. They created several fired clay objects that the children had definitely not encountered before. In total, 6 items of unique shape and texture were created. Then the objects were colored in pairs in blue, red and green. Next, the items were randomly assigned names: "zibi", "theme", "dodi", "hubl", "wawa" and "mapu".

Next, the items were randomly assigned names: "zibi", "theme", "dodi", "hubl", "wawa" and "mapu".

After that, preschool children (average age 1.5 years) were invited to the research laboratory. They were invited to sit opposite each other at a small white table in a white room with a white floor. Parents were given the names of six items, and the items were placed in small boxes. On the sides of the boxes were pictures of items and their names.

Parents encouraged children to interact with new objects. Then parents and children played with new items. The playing time was 4 periods of two minutes, in each of the periods the children were allowed to play with three toys.

The rules did not require parents to teach children the names of objects. Parents were also not told that they would later test the children's ability to remember the names of objects. The entire part of the experiment, during which the children played with the objects, was videotaped.

After that, a test was made of how well the children remembered the new names. They were shown 3 objects of different colors, after which they were asked to point to an object with a particular name. During testing, children in most cases correctly found the right items. Some of them correctly named all 6 items.

They were shown 3 objects of different colors, after which they were asked to point to an object with a particular name. During testing, children in most cases correctly found the right items. Some of them correctly named all 6 items.

After that, the scientists carefully studied the videos of the experiment, as a result of which they found a pattern. At the moments when the parents called the child a new object, it was often in the child's field of vision and was closer than the other objects. If this condition was met, the child memorized the name of the object.

Video recordings have shown that parents prefer to name an object to their child when the child sees and touches it. The more the child's visual attention is focused on an object, the more likely it is that the baby will remember its name.

Looking at the world through the eyes of a child, we can learn how the child compares objects with words. It is important that at the moment of naming there is only one object in front of the child, and the child understands that this particular object is being called to him.