When do most kids learn to read

When Do Kids Learn To Read: A Helpful Guide

Whether you are about to have your first child or you’re in the middle of raising number two or three, you may be wondering: when do kids learn to read?

This is a legitimate question, but there is no one-size-fits-all answer. That’s why we’re here to show you how to encourage your child and help them learn to read in fun, uplifting ways!

Cracking The Reading Code

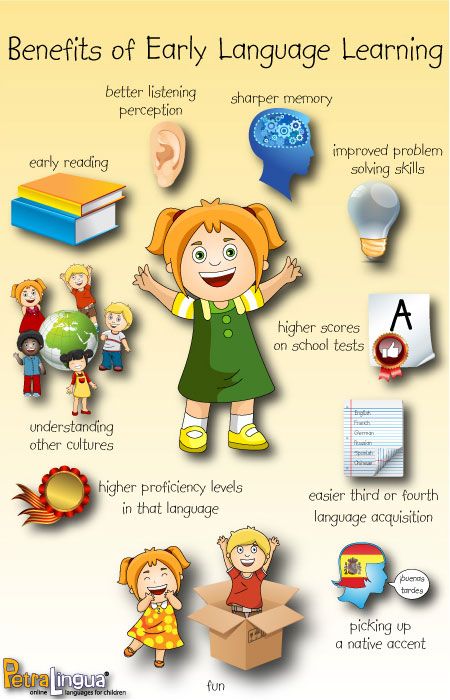

Most children learn to speak — either verbally or in sign — through exposure. This happens naturally and without direct instruction. But the more you speak with your child the more you impact their receptive and expressive language which, in turn, can impact their reading.

Unlike speaking, children can’t pick up reading through natural language processes. Instead, we have to teach them how to “crack the code” of written language.

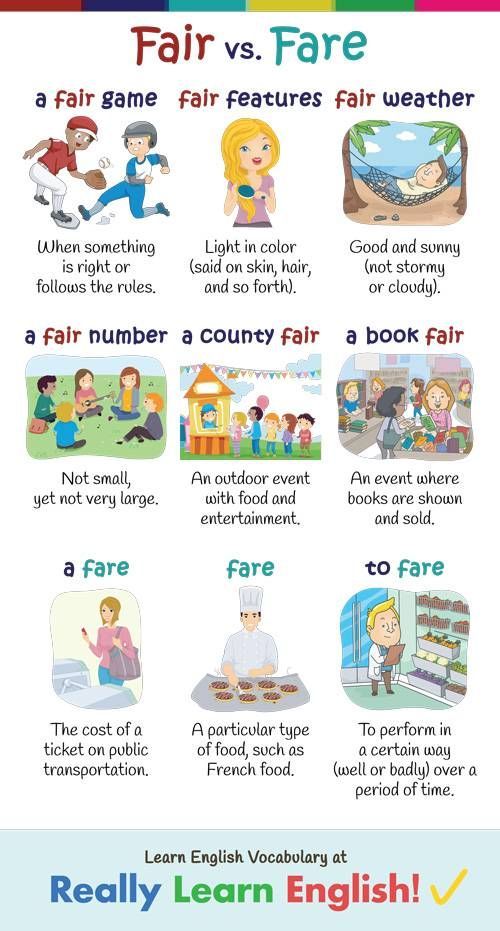

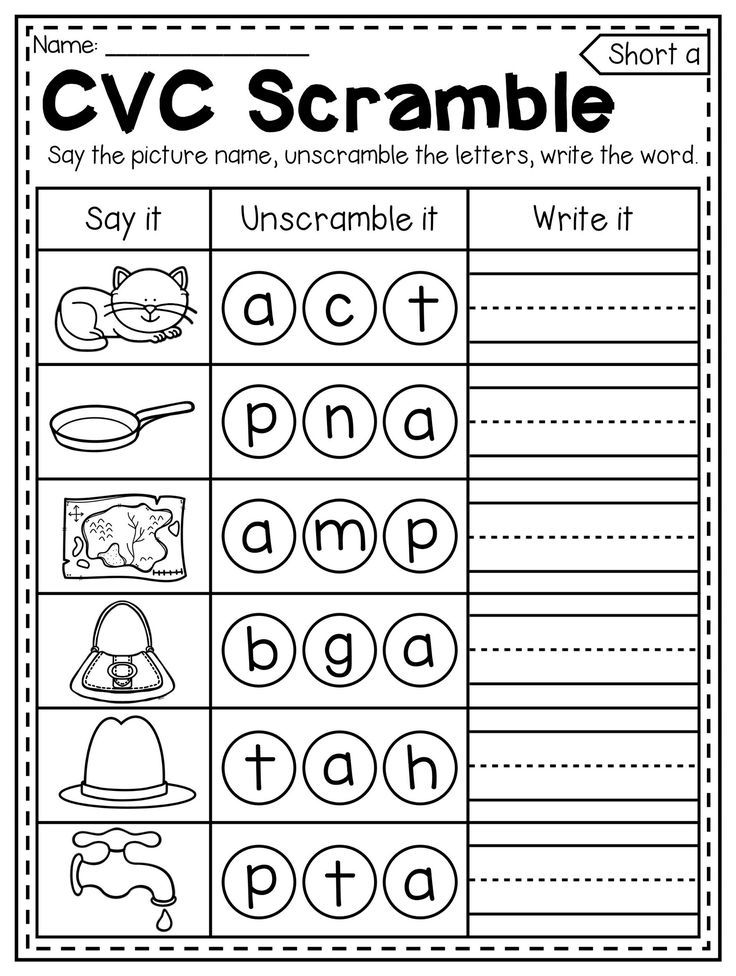

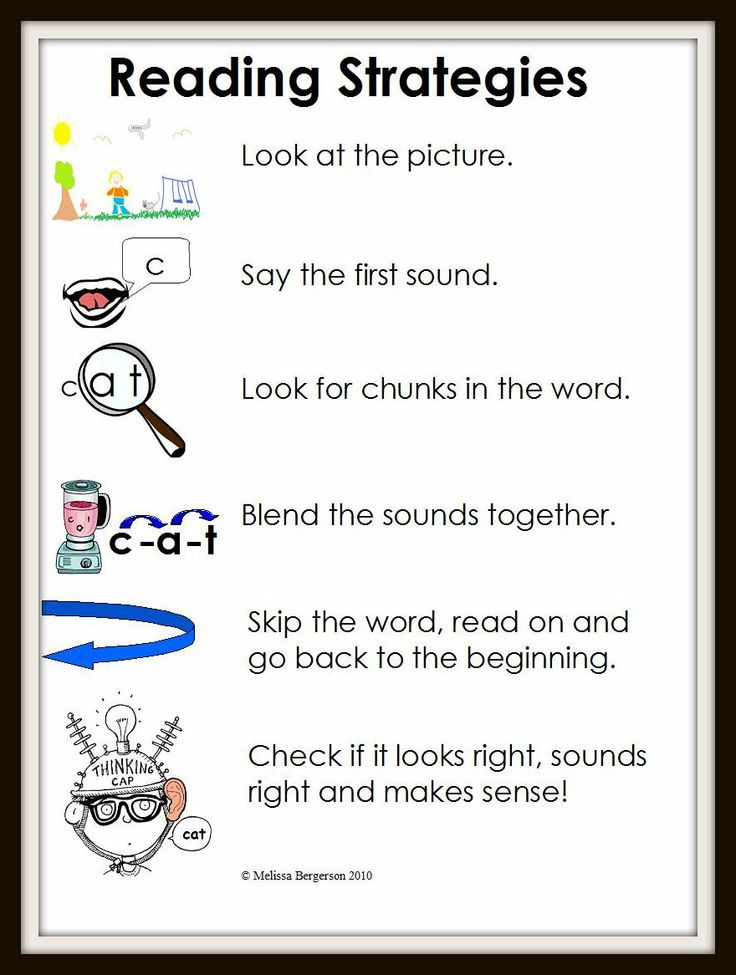

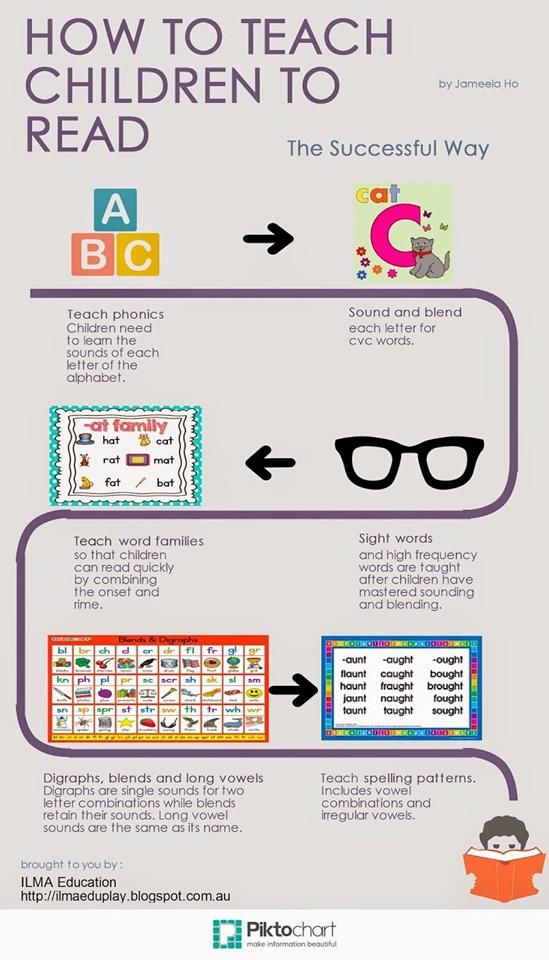

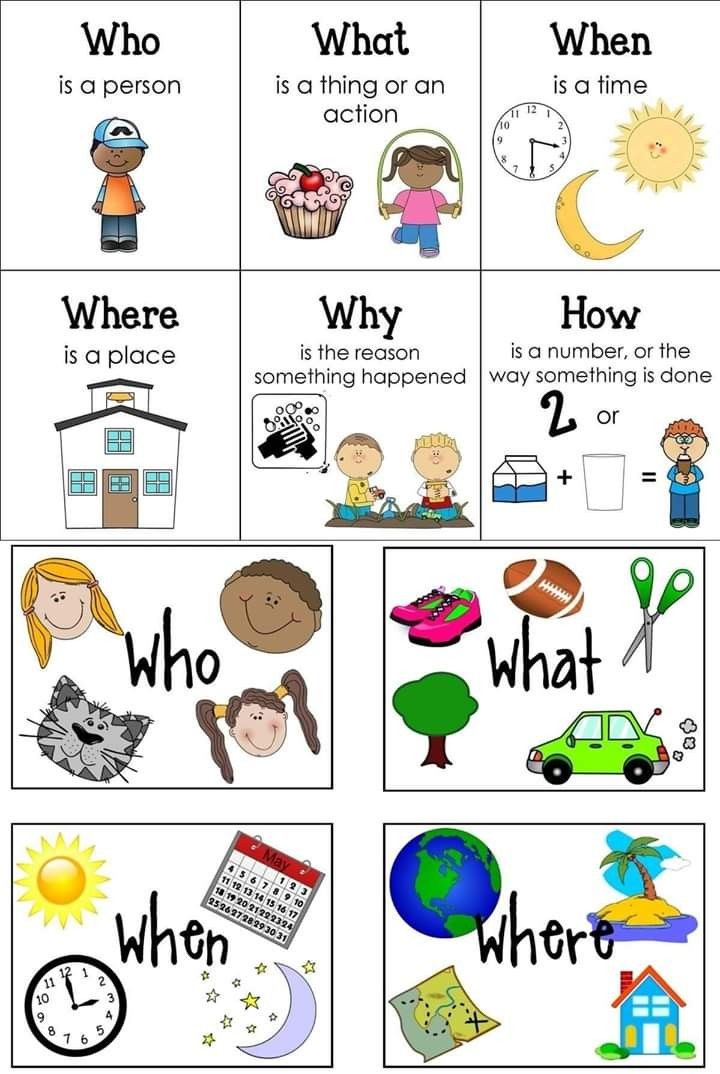

First, children must understand that words are made up of individual sounds (or phonemes) and that each sound is matched to a letter. To crack the reading code, a child must learn to hear sounds in words and to pair them with letters, eventually blending the sounds together to read.

As you might have guessed, learning to read can take time. So, to give you a clearer picture of the overall learning process, here’s a brief look at the pre-reading skills your child will develop (in no particular order) throughout their literacy journey.

Pre-Reading Skills

Phonological Awareness

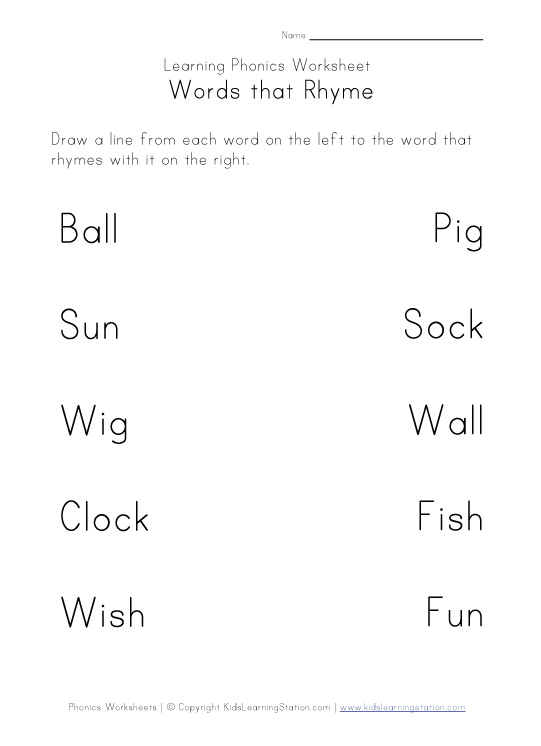

Phonological awareness is an understanding of sounds in our language and how they relate to each other. This includes segmenting sounds and syllables in words, rhyming, and blending syllables and sounds together to form words.

Alphabet Knowledge

As the name suggests, alphabet knowledge is the ability to both recognize and name the letters of the alphabet.

Print Awareness

Print awareness is a broad term that includes familiarity with different forms of text (books, menus, newspapers, magazines, etc. ), understanding print structure, and knowing how to hold these sources of information correctly.

), understanding print structure, and knowing how to hold these sources of information correctly.

Without print awareness, it’s hard to connect text in a meaningful way and understand the words and phrases on a page.

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate sounds in a written word.

This skill is often mistaken for phonological awareness, but it is actually a subset of phonological awareness. Phonemic awareness focuses on identifying and manipulating individual sounds, known as phonemes.

While it might take your child a while to master each of the skills above, they are the building blocks of the reading (and writing) journey. With practice and patience, your young learner will be grabbing their favorite book and reading it all by themselves before you know it.

When that will happen depends on several factors and varies from child to child. Let’s take a closer look!

When Do Kids Learn To Read?

When it comes to reading, all kids are different. When your child learns to read and when another child their age learns to read may be a year (or more) apart. That’s OK! It’s all part of kids’ uniqueness.

When your child learns to read and when another child their age learns to read may be a year (or more) apart. That’s OK! It’s all part of kids’ uniqueness.

When your child learns to read may also depend on their pre-reading engagement — in other words, how often they’re exposed to reading.

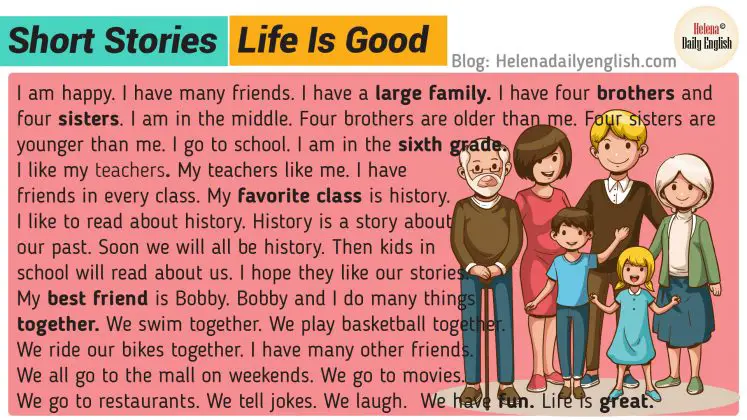

For example, kids who are read to, who have parents modeling a love of reading, and who have books as part of their everyday life tend to be more excited to learn to read. These children also develop essential pre-literacy skills, such as print awareness.

Another thing to keep in mind is that your child’s reading development is directly impacted by how much they read, especially independently.

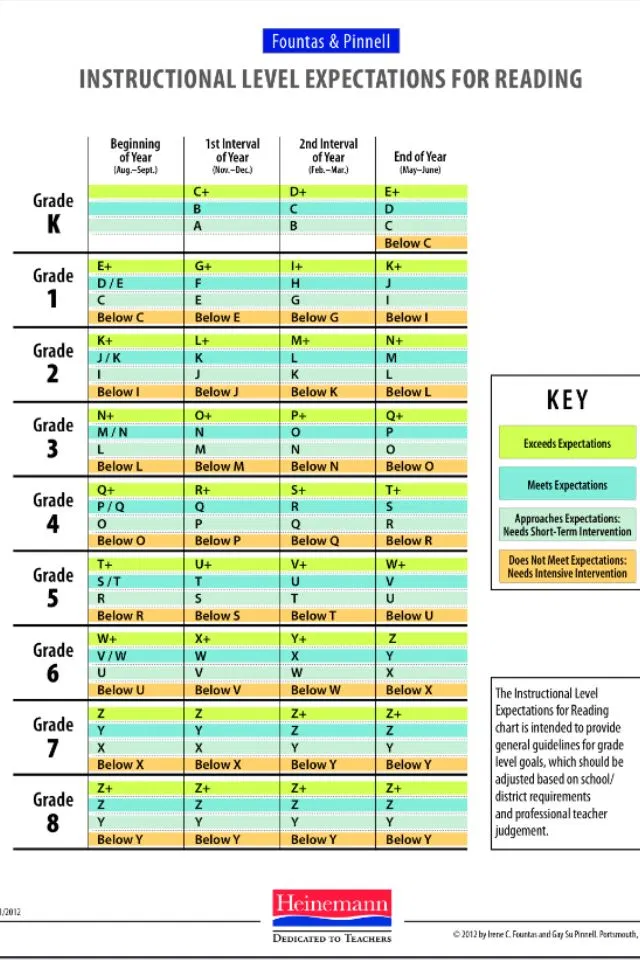

Rather than worrying about a precise timeline, it’s better to keep in mind a generalized idea of what milestones your child can reach at different ages.

Let’s take a look at those milestones (or benchmarks) below.

Reading Benchmarks By Age

Babies (Under 1 Year Old)

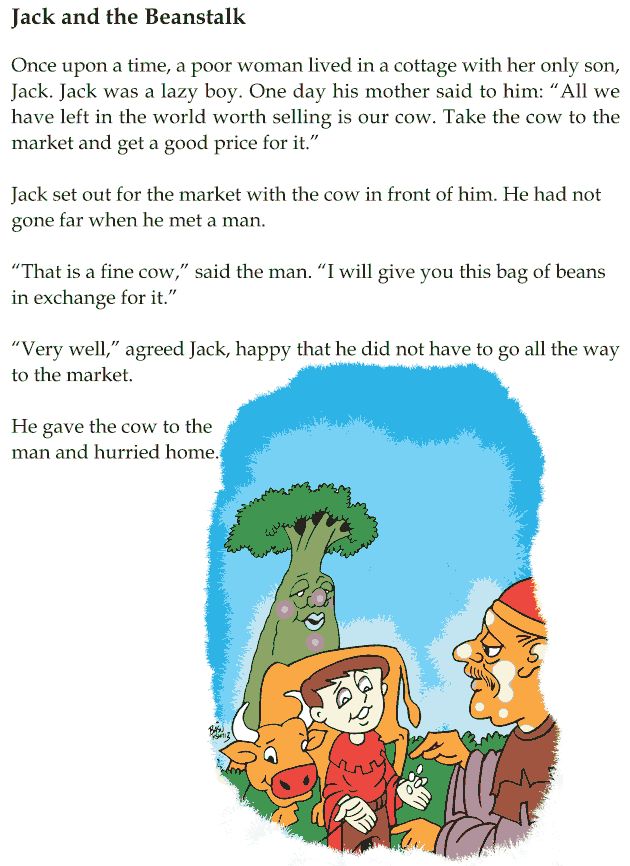

Babies may begin using board books or soft books to play with.

Books with lots of colorful illustrations and dynamic storytelling will help engage your baby and foster a love of reading right from the start.

Although your baby can’t talk yet, keep an ear out for any noises they make in response to your reading. Cooing and other noises can help signify that your baby is paying attention, having fun, and bonding with you while learning.

Toddlers (1 To 2 Years Old)

As they grow older, your baby’s cooing might evolve into some very enthusiastic baby babble. They may giggle and chatter in their own unique baby language in response to your story narrations.

By 18 months, most children move on from babbling to using words. Their vocabulary increases every day! You can take advantage of this vocabulary explosion when you share books that have pictures of things they love.

To encourage them, you can point to illustrations or pictures and ask, “What’s that?”

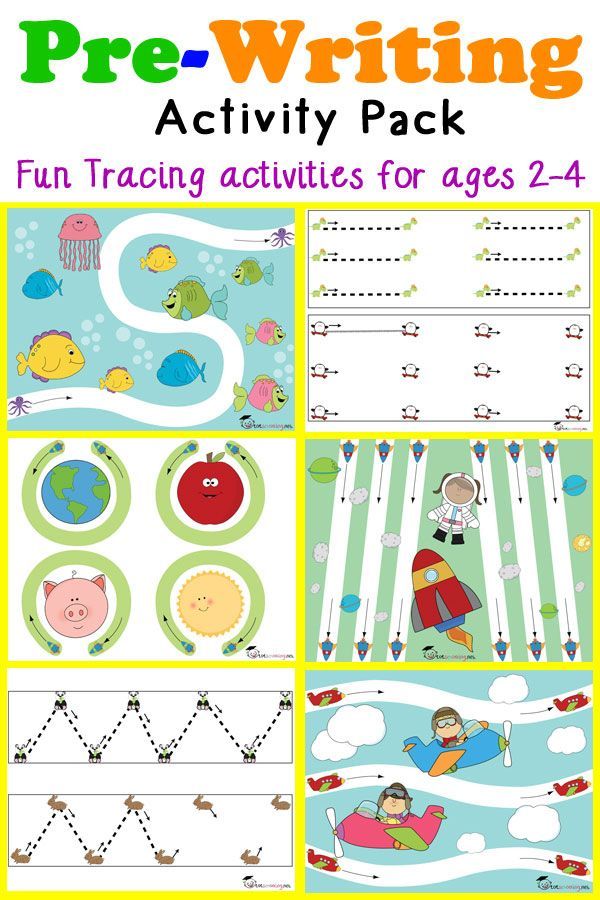

Getting them physically involved helps, too. If you would like to try this, start by holding their hand in yours as they turn the page. This will develop their motor skills and mimic what real reading feels like.

This will develop their motor skills and mimic what real reading feels like.

You can also run your finger along the print, showing that the words are important and that you follow them from left to right. This helps develop print awareness.

Preschool-Aged (3 To 4 Years Old)

Now is when the initial groundwork you laid when your child was a baby begins to pay off! Keep in mind, though, that there is a large difference in what a beginning three-year-old and a late four-year-old can do.

As your child moves through preschool education, they’re introduced to more fundamentals about books and reading. A three-year-old may start to understand how to identify different parts of a book — the spine, title, cover, and author.

They may also be able to tell you what the story was about in basic terms (a shark who loves cupcakes, a puppy who can ride a bike, and so on).

Three- and four-year-olds are beginning to develop ideas about the alphabet and to attribute sounds to letters. They are also ready to engage in listening games that will promote their ability to use phonics as beginning readers.

They are also ready to engage in listening games that will promote their ability to use phonics as beginning readers.

You can boost their phonics confidence by singing lullabies or nursery rhymes with them. Enrich the experience by clapping!

Learning to sing the alphabet also usually comes by the end of the preschool years. This is a great time to encourage your child to explore recognizing at least half of the alphabetic letters and having a go at writing their own name.

Kindergarteners (5 To 6 Years Old)

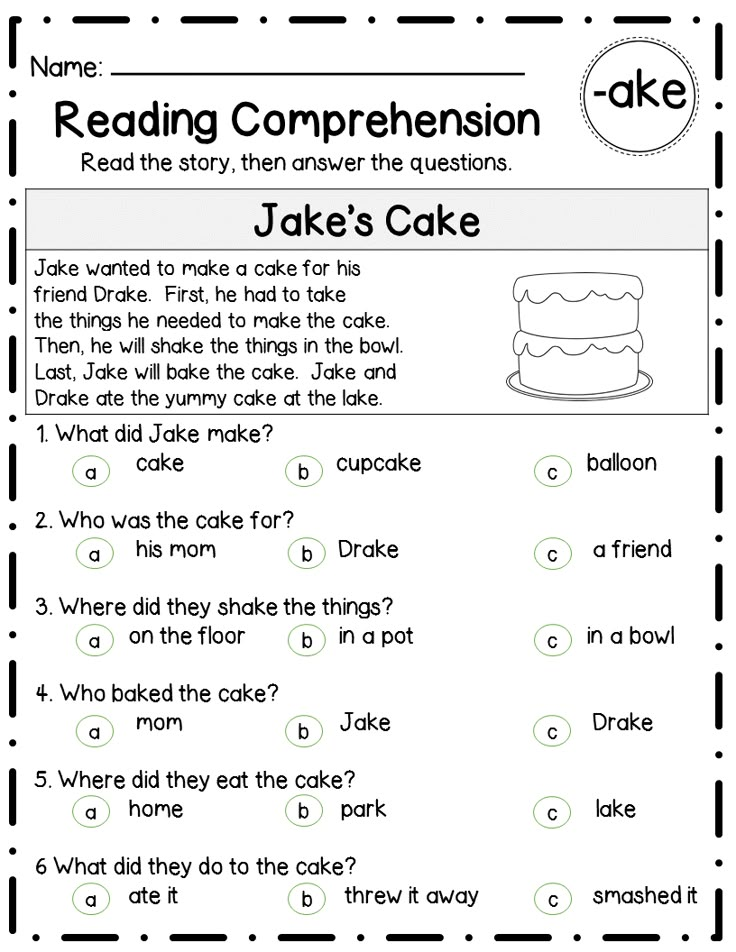

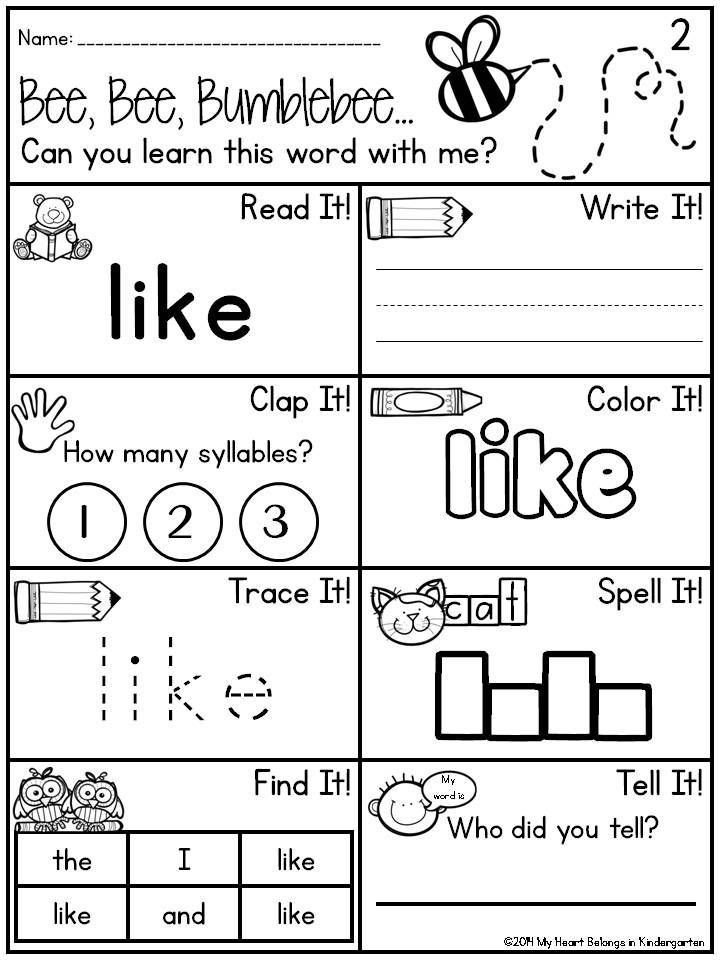

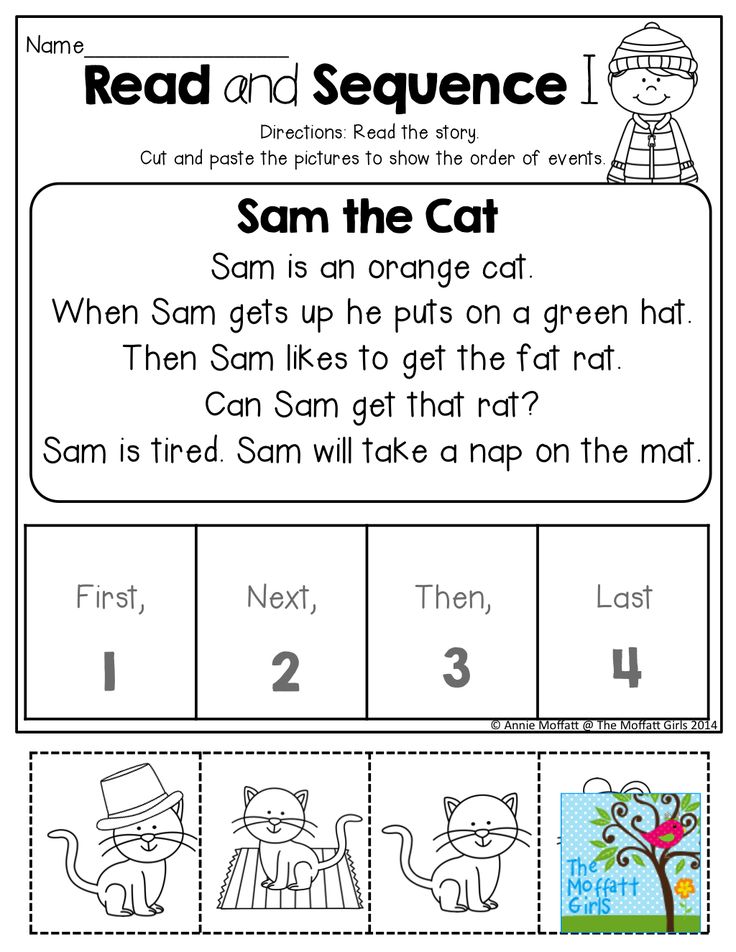

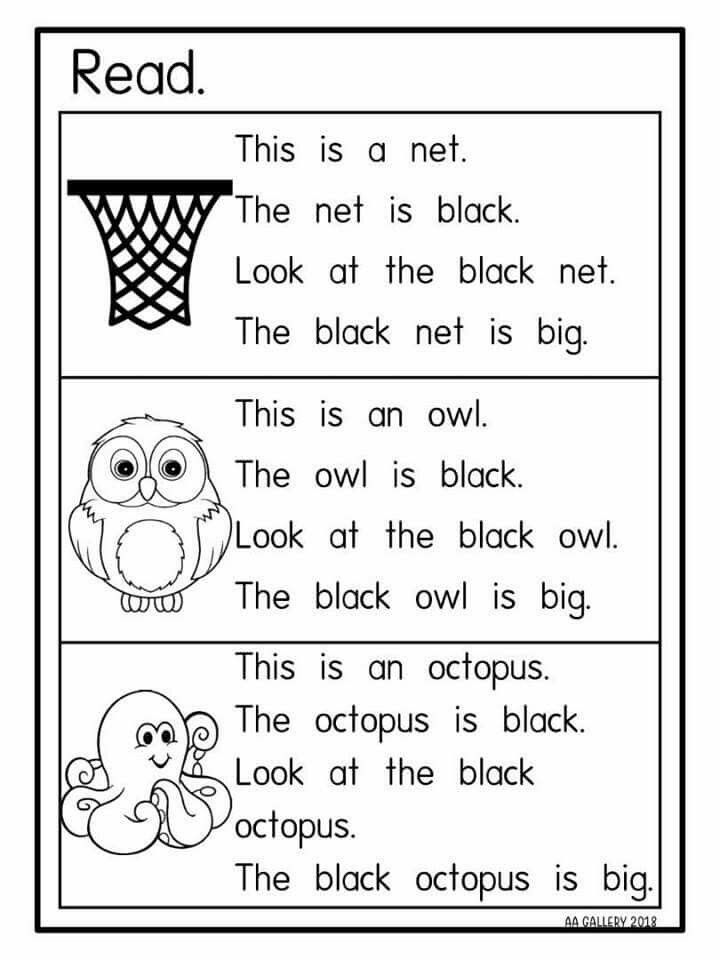

Formal introduction to “sounding out” or decoding words begins at this age. As part of this work, your child will benefit from learning to hear individual phonemes (single letter sounds) in words — a foundational skill for sounding out words.

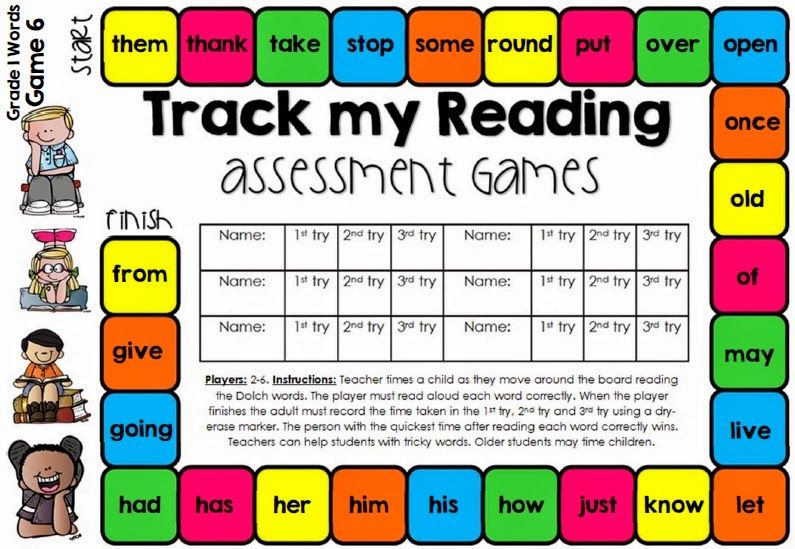

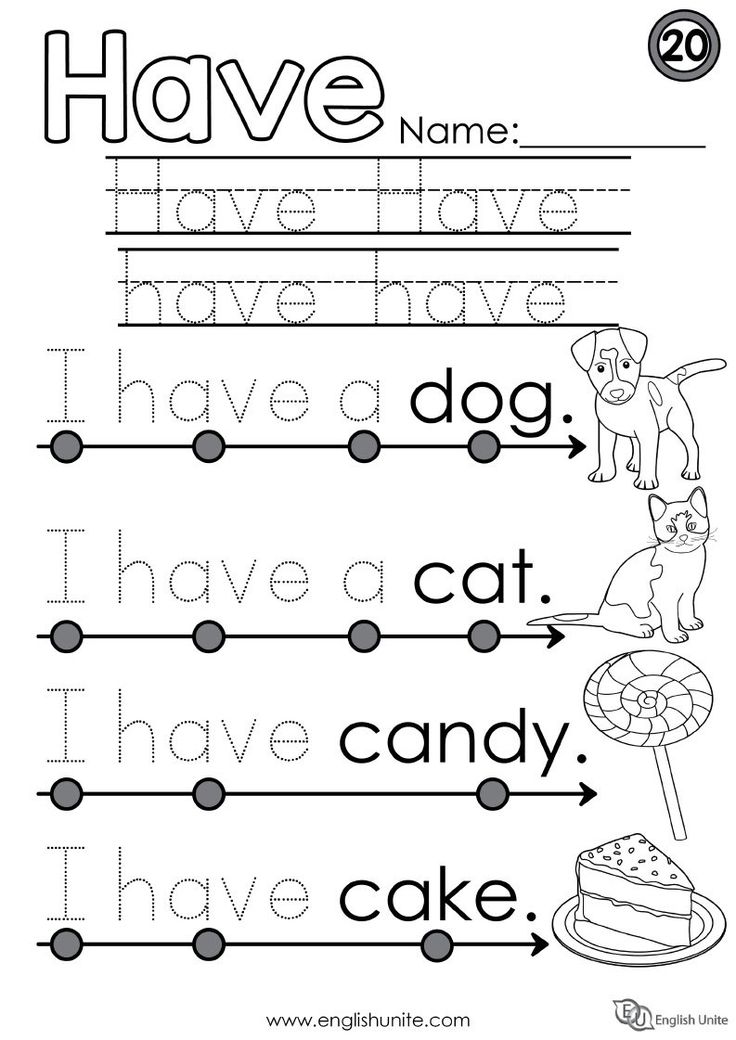

Beginning to learn sight words is also important at this age, as sight words don’t always follow regular phonemic patterns (they don’t sound the way they’re spelled).

For ideas on how to incorporate sight word learning into your routine, check out our article 4 Highly Effective and Fun Sight Word Games To Help Your Kids Learn.

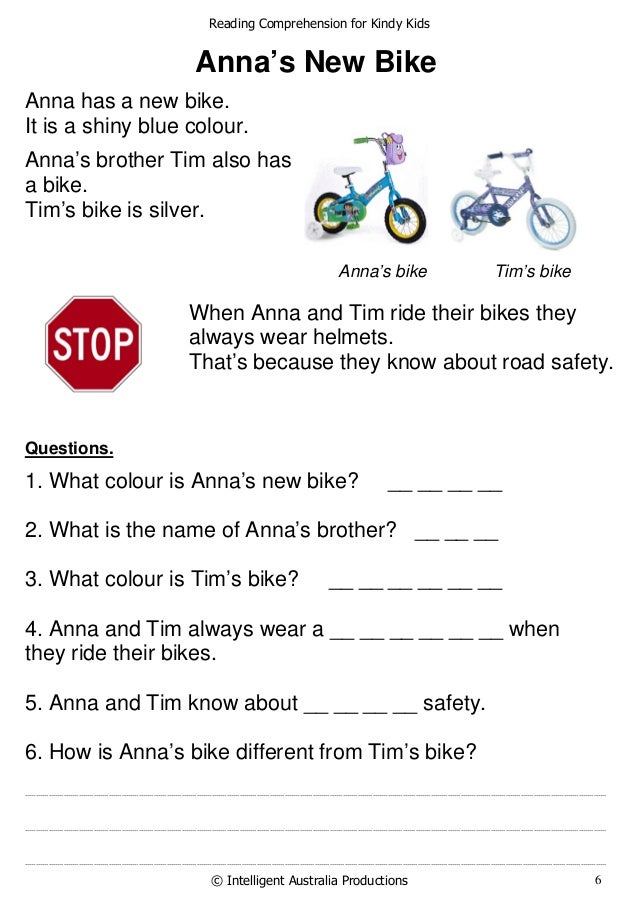

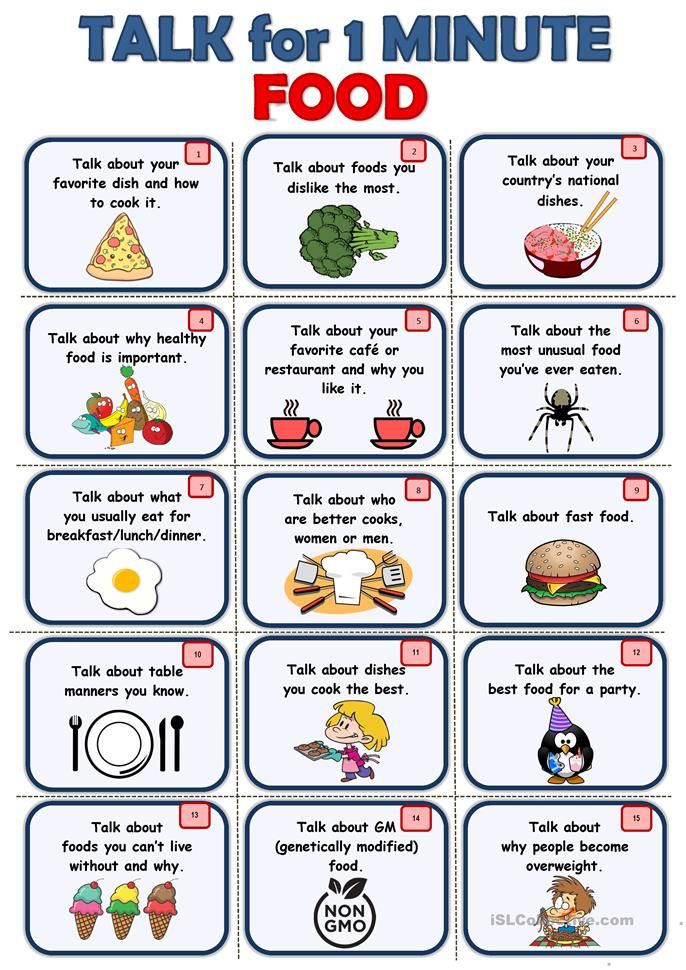

To help build your Kindergartener’s reading confidence, prompt them to summarize what happened in the story while you read with them. To make it fun, you can play the silly, forgetful parent!

Asking simple questions about the story helps your child get their brain working and helps you know if they understood the book.

Young Elementary (6 To 7 Years Old)

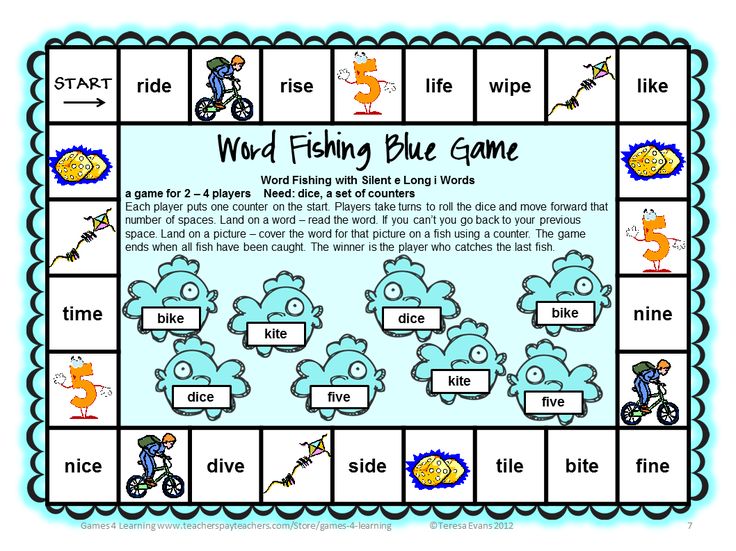

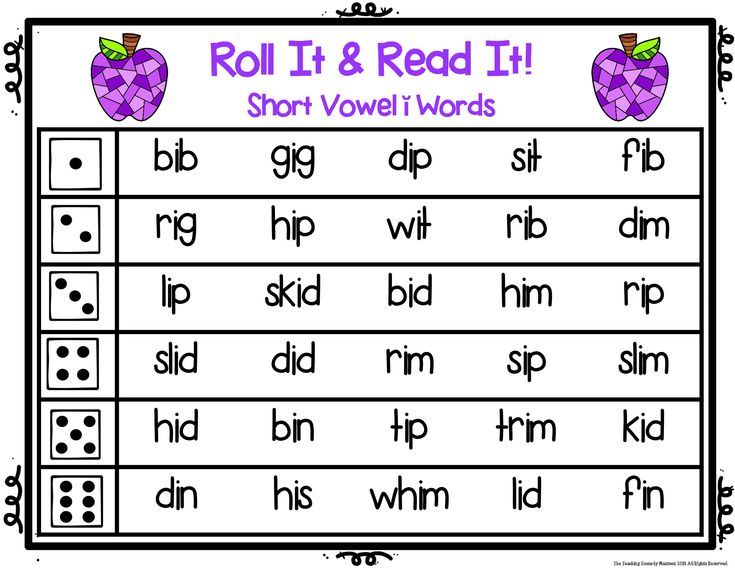

At this age, children learn more advanced phonics, such as:

- Silent e

- Vowel teams like ai and oa

- Vowels controlled by R to make er, ir, ur, ar, or

- And more.

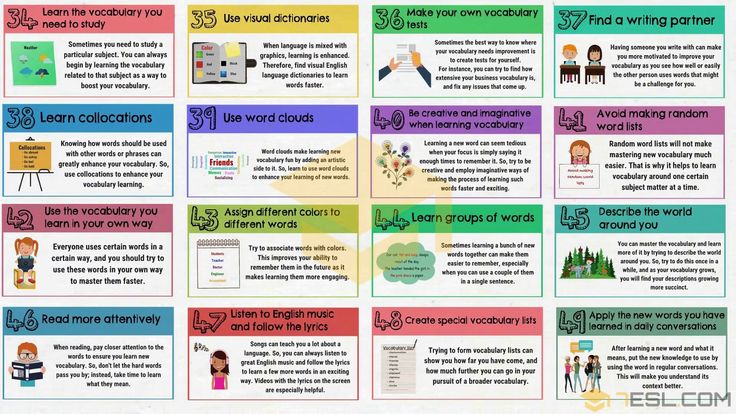

Your child may begin receiving weekly vocabulary word banks to learn. They will also be exposed to common spelling rules and patterns.

Additionally, when you see your child re-reading their favorite books, know that they’re building strong fluency. This helps them engage more deeply with the texts and investigate words that might be unfamiliar.

To foster a love of reading in your child at this age, you can help them draw conclusions and parallels between things in their life and the things they read.

After all, reading is about making new connections to familiar facts that your child knows and loves, as well as exploring unfamiliar ideas!

Older Elementary (8 To 10 Years Old )

During these years, your child is likely moving away from learning to read — instead, they’re reading to learn.

They may choose to read independently more often. They may read for pleasure or to explore their own interests, as well as answering questions about the text and looking for real-world examples.

That being said, even after children are independent readers, it’s a good idea to continue to read aloud. This is an opportunity to share books that are more difficult for them to read on their own.

It can also be good for you to read books that your child reads either on their own or for school and talk about them together, like a book club! This can be a fun way to connect with your child and spend more time together.

Tips For Boosting Your Child’s Reading Confidence

There are plenty of simple things you can do to help your child learn to read — but first and foremost, we want to help your child think of reading as fun, relaxing, and rewarding.

While you’re reading with your little one, consider treating reading aloud as a bonding time or a special activity, rather than a school lesson. We don’t want you or your child stressed out!

Remember: reading confidence comes with time and practice. It’s OK if your child learns differently than their friends –– that’s completely normal!

With that said, here are some bonus tips to help boost your child’s confidence and encourage them to read.

Read, Talk, And Sing To Your Baby

If you want to get a head start on encouraging a love of reading in your child, talk and read to them as much as possible when they’re a baby, and don’t stop — even after your child is an independent reader!

While you’re reading, you can react to illustrations and repeat words for an even bigger impact. Although your baby can’t speak yet (so you’re not sure if it’s paying off), we promise it’s worth it!

Finally, as we mentioned earlier, singing lullabies and nursery rhymes is also a great way to expose babies, toddlers, and preschool children to words.

Show Your Child That Words Are Everywhere

Once your child has moved into the toddler stage — and as they continue to grow — point out letters and numbers to them as you walk along in everyday life. They will begin to take notice (and probably want to read themselves!).

You can even make it fun by turning it into a game once your little one starts learning sight words (“I spy with my little eye the word red”).

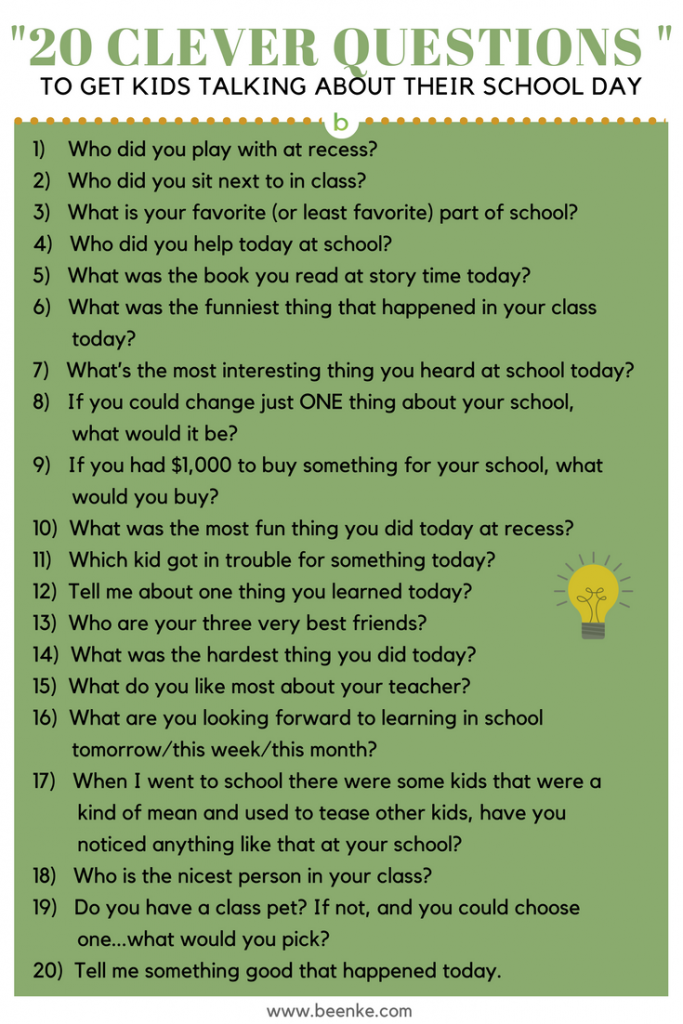

Talk In Order To Read

This one sounds simple, but talking to your child helps to improve their vocabulary and knowledge base. If you’re looking for ways to talk to your child more, here are some ideas:

- Ask specific questions (such as “What did you do at school today?”)

- Explain what you’re doing while cooking

- Tell them about a favorite memory from your own childhood

Conversations help children with speaking and listening skills, and familiarity with new words and subjects will help when they read books. As a bonus, having conversations with your child helps you connect as a family!

Take Turns Reading

It’s important for kids to know what fluent reading sounds like. Listening to you can be a huge help!

Listening to you can be a huge help!

If you’d like to try this during storytime, take turns reading pages. (You read a page, then your child reads a page.) You can customize the split depending on your child’s energy, reading level, or how much time you have.

Switching on and off will give them a mental break in-between pages and keep them excited about reading with you!

4 Fun Activities To Develop Reading Skills

In addition to the tips above, here are some fun activities to try at home with your young learner as they develop their reading skills.

1) Sight Word Scavenger Hunt

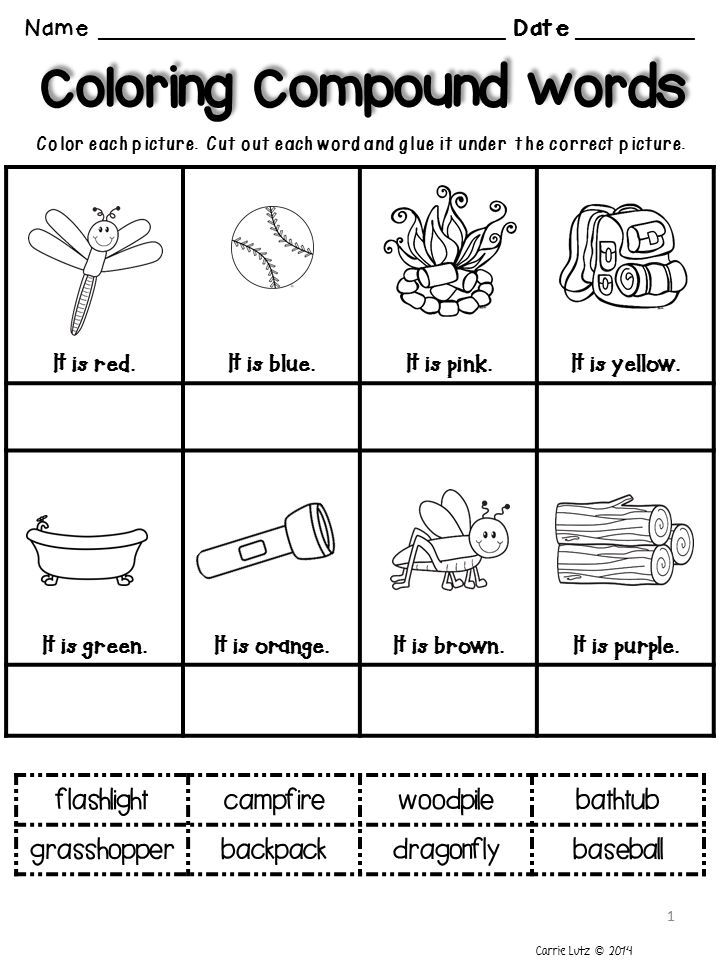

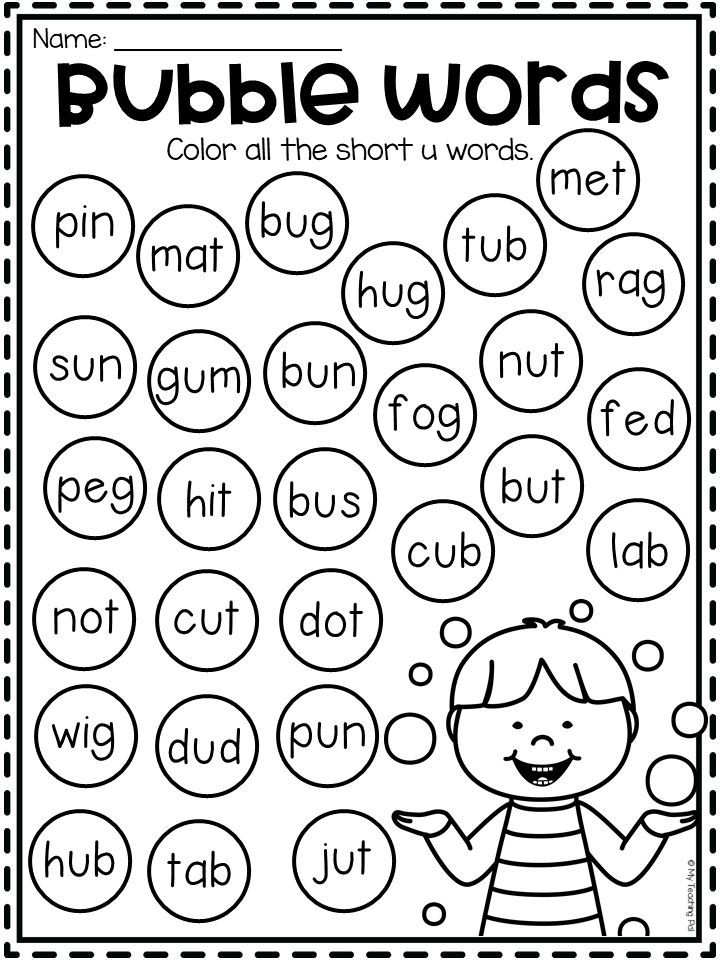

Sight words are words that appear often in text. These are words such as the, on, have, was, what, etc. These words can be tricky because they aren’t easy to sound out or decode, so we need to memorize them or recognize them by sight.

Since they are seen so frequently, helping children get comfortable with sight words allows them to read more confidently and fluently.

To practice this skill, one of our favorite sight word games is Sight Word Scavenger Hunt. All you need for this game is a marker, index cards, and a sheet of paper.

Start by writing down 10 sight words (one on each card), and then hide these cards in places around the house. (Be sure to choose spots familiar to your child.)

The goal of this game is simple: Have your child find all the cards by listening to clues you’ve written down on your sheet of paper.

For example:

- I climbed ____ the chair — On!

- What word rhymes with buzz? — Was!

As you call out each clue, your child will search for the sight word that matches. You can also write the sight words on a separate piece of paper as a reference for them if needed.

And to make things even more interesting, feel free to add a timer into the game and see how fast they can find the cards!

2) Become An Author

Children are natural storytellers. They want to share their adventures, ideas, and thoughts. In fact, it is sometimes hard to get them to stop talking!

They want to share their adventures, ideas, and thoughts. In fact, it is sometimes hard to get them to stop talking!

You can take advantage of this love of oral language to make a bridge toward written language. How? Write a book together.

All you’ll need is an empty booklet (this can be blank pieces of paper stapled together), a pencil, and some crayons. Start writing the story by asking your child to describe something meaningful to them, such as what they did at school or while visiting their grandparents.

As your child narrates their story, write down about one to two sentences on each page. Keep in mind that you don’t actually need to write the exact words. It is fine to write a sentence that expresses the main parts of your child’s dictation.

You might need to ask prompting questions to give the story more details, such as:

- Was it a hot or cold day?

- Was your grandma wearing a sweater? What color was it?

- What did you have for lunch on that day?

Once the story is complete, your child can add some illustrations to help bring it to life. And just like that, you have a homemade storybook that you can enjoy reading together!

And just like that, you have a homemade storybook that you can enjoy reading together!

3) What Starts With…

Learning the alphabet and letter-sound connections is an essential step to reading fluently. You can help your child work on these skills by playing a guessing game that focuses on all their favorite words.

What letter does balloon start with? How about pizza?

When your child guesses correctly, encourage them to come up with more words that start with the same letter. For example, “Balloon starts with a b! So does basket, butterfly, baby, bubbles, buttons, and ball!”

This repetition will help reinforce the letter-sound connections that play an important role in reading (and writing).

4) Pick The Word

This game also focuses on sight words. To get started, write six sight words down on index cards, one word per card. On a separate sheet of paper, list the same words twice. One list will be for you and the other for your child.

Next, place the index cards with the words facing down on a flat surface (i.e., table). Begin playing by picking a word from your list. Then, flip four cards over so the words are facing up. If you flip over the word you selected, cross it off your list and flip the other cards back over.

If you don’t find the word you were looking for, you’ll need to wait for your next turn to try to find another one. Remember to mix the cards up before the next player starts.

The first player to cross off four words from their list wins!

This is a great game for continued sight word exposure. The more familiar your child gets with them, the more confident they’ll be while reading.

When Do Kids Learn To Read: FAQs

Why Does My Child Have Trouble Reading?

If your child isn’t the first to read in their class, it doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with them. They may just need some more time and support to develop their abilities. That’s OK! Every child learns at their own pace.

Learning to read is quite a lengthy process and involves a multitude of skills, and some kids may find it more challenging than others. There are various reasons for this.

Some children might struggle with the type of reading instruction used in class. Others may find it difficult to understand how language works (e.g., matching sounds to letters or recognizing the sounds in words).

No matter what the reason is, there are things you can do to help.

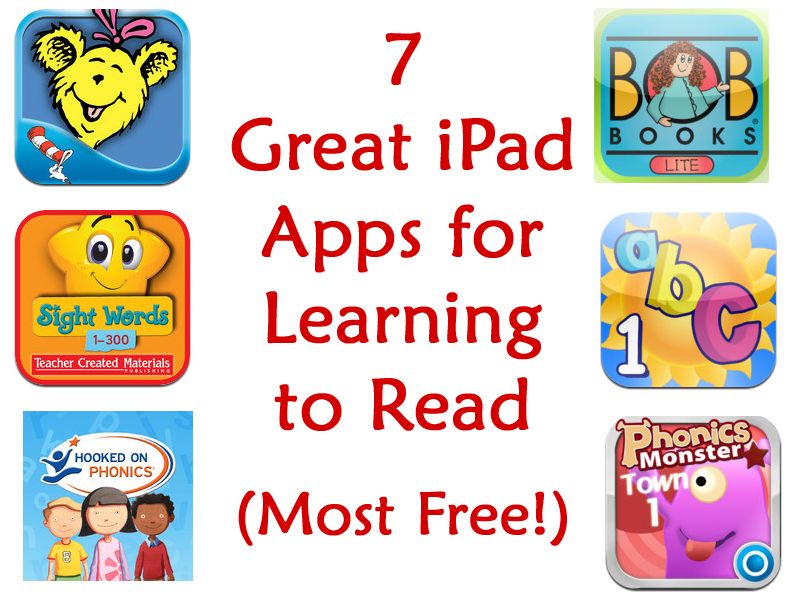

Supporting children in their early years is essential to the HOMER team. That’s why our Learn & Grow app focuses on multiple key developmental areas, including early childhood reading.

Our experts developed it to provide a personalized pathway that builds essential skills — from letters and sounds to sight words and, eventually, reading and spelling.

Why Is My Youngest Child Not Reading When My Oldest Did?

When it comes to children’s literacy journeys, the last thing you want to do is compare your own children to each other, their friends, cousins, or peers in school. As you already know, kids are very different, so they will hit milestones at different times.

As you already know, kids are very different, so they will hit milestones at different times.

If your oldest started reading at four or five years old, that’s great, but don’t expect your youngest to do the same.

Also, keep in mind that while some kids might start earlier, according to the U.S Department of Education, children generally begin reading at around six or seven years of age (first or second grade).

Who Can I Reach Out To If I Think Something’s Wrong?

Even though it’s normal for children to learn to read at different ages, sometimes medical concerns may get in the way. Or, in some cases, children have trouble reading because they have a learning difference and might need special instruction before they can learn to read fluently.

If you suspect this is the case with your child, talk to the teacher or ask to meet with the school learning specialist. They will know if the issue is developmental or if there are underlying problems you’ll want to address.

You can also reach out to a local reading specialist (outside of your child’s school) who may be able to assess your child first and help you determine if there are additional things to address. They’ll be able to guide you in the right direction.

There Is No “Right” Time

No matter when your child learns to read, don’t worry! With a little love and support from you, they will get there in their own time. If you’re ever concerned, feel free to reach out to your child’s teacher or another professional.

As you continue to help your child learn to read, keep the benchmarks and tips we mentioned above in mind. But remember that what’s most important is engaging your child in ways that are fun, stimulating, and don’t add stress to your family’s already busy schedule.

Making reading time fun and light helps build your child’s confidence and love for learning!

Finally, if you find yourself needing a little support along the way, try our HOMER Learn & Grow app to help your child thrive on their reading journey!

Author

When Do Kids Learn to Read?

By Tara Drinks

At a glance

Learning to read is a process that involves different skills.

Kids start to learn to read at different ages.

Some kids need extra help learning how to read.

Learning to read is a process that involves different language skills. It happens over time, so it’s hard to say exactly when kids learn to read. To some people, reading means being able to sound out words and recognize words that can’t be sounded out. To others, reading means being able to read and understand sentences and text.

Learning to read is different for every child. Some kids start to learn to read in daycare or preschool. Others start gaining the skills in kindergarten or first grade. Read on to learn more.

At what age do kids learn to read?

Kids develop reading skills at their own pace. And some kids learn earlier and more quickly than others. Here’s what reading typically looks like at different ages:

- By age 2, kids often start to recite the words to their favorite books. They also start to answer questions about what they see in books.

- In preschool, kids typically start to recognize about half the letters of the alphabet. They also start to notice words that rhyme.

- In kindergarten, kids often start matching letters to sounds. They also start to recognize some words by sight without having to sound them out.

- By second grade, most kids can sound out and recognize words and can read and understand sentences. Most people consider this as having learned to read.

Keep in mind that every child is different. Not all kids develop reading skills at the same rate. Taking longer doesn’t mean they’re not on track to become good readers.

Why kids might have trouble learning to read

Learning how to read can be challenging for some kids. But that doesn’t mean they’re not smart. They just may need extra time and support to become full-fledged readers.

There are many reasons why kids have trouble learning to read. Some have a hard time understanding how language works. For example, they may struggle with recognizing sounds in words or matching sounds to letters.

For example, they may struggle with recognizing sounds in words or matching sounds to letters.

In some cases, the type of reading instruction plays a role. Learn more about what can cause trouble with reading.

What helps kids learn to read

Practicing at home can help kids improve reading skills. Here are some ideas parents and caregivers can try and teachers can suggest:

- Make reading a habit. Kids learn from what they observe. Try reading a book together every night before bedtime.

- Play reading games. While running errands, have kids read the road signs out loud. Or play rhyming games together.

- Have conversations. Talk about things you’re seeing or feeling and ask questions so kids can do the same. This helps build the language skills kids need to be strong readers.

Get more ideas to help kids with reading.

Key takeaways

By second grade, many kids can read and understand sentences.

Play reading games and have conversations to help kids learn to read.

Learning to read can be challenging for some kids, but that doesn’t mean they’re not smart.

Related topics

Reading and writing

Tell us what interests you

About the author

About the author

Tara Drinks is an associate editor at Understood.

Reviewed by

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Babbin, EdD is an instructional specialist at Lower Macungie Middle School in Macungie, Pennsylvania.

At what age should a bilingual child be taught to read Russian?

I am very glad to all your questions and continue my Christmas stories about the wonderful world of sounds and letters. It's time to move on to one of the most important questions:

- At what age can a child be taught to read?

- I must say right away that this does not depend on age. It's time for a child to start learning to read then, when he is ready for this . And when answering this question, searching the Russian-speaking Internet will not help you. For the simple reason that it correctly and in detail describes the situation of readiness to learn to read for a monolingual child who is preparing for school, that is, 6-7 years old.

It's time for a child to start learning to read then, when he is ready for this . And when answering this question, searching the Russian-speaking Internet will not help you. For the simple reason that it correctly and in detail describes the situation of readiness to learn to read for a monolingual child who is preparing for school, that is, 6-7 years old.

Our situation is completely different - children go to school from the age of 4, and they are bilingual. And here we have another main task of teaching reading, no matter how paradoxical it may sound. We teach to read, first of all, in order to develop and retain the Russian language . So that the child has a visual support as early as possible in the form of a syllable, a word and a short sentence, which will allow him to develop phrasal speech, expand his vocabulary and, thus, preserve the Russian language, which after 4 years is on the periphery of his speech activity - a few hours after school with a Russian-speaking parent, and sometimes less. And it is not the main language of knowledge of the world, that is, the language of the educational and play activities of the child. The task of enjoying reading, of regularly reading books in Russian, arises only at the second, later stage, when Russian is preserved. By the way, this stage begins approximately at the age of the beginning of the first grade in Russian-speaking countries - from 6 years old.

And it is not the main language of knowledge of the world, that is, the language of the educational and play activities of the child. The task of enjoying reading, of regularly reading books in Russian, arises only at the second, later stage, when Russian is preserved. By the way, this stage begins approximately at the age of the beginning of the first grade in Russian-speaking countries - from 6 years old.

It is also important to understand that readiness criteria for learning to read in a bilingual child is formed in two languages and may not be developed in the same way in each language . And if in the Russian language some moment is not fully formed, but it is formed in English, then this does not interfere with starting to teach the child to read in Russian.

What are these criteria for a child's readiness to learn to read ?

Experts consider three main aspects of a child's readiness to learn to read: psychological, speech and phonemic . What exactly do they mean and what are the key points for us to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian and what can we turn a blind eye to?

What exactly do they mean and what are the key points for us to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian and what can we turn a blind eye to?

Psychological readiness for reading is associated with the development of the child's cognitive activity and his readiness for learning activities in general. How to define it? Ask yourself the following questions:

Does the book itself arouse curiosity in the child? When you walk into a bookstore or library, do the books spark a keen interest? Does your child like looking at books?

Does he try to "write" his own "book" by sticking pictures on a folded piece of paper or drawing them?

Does he ask adults to read him a book? Would he prefer reading a book or looking at pictures to a TV or a computer? Does he enjoy a bedtime reading ritual, if there is such a thing?

Does he try to “read” the book himself, imitating reading and imitating adults?

For parents of bilingual children, it is clear that it is not very important whether the child is drawn to Russian or English books. It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

Speech readiness , according to monolingual criteria, includes a rich vocabulary, the ability to speak in extended extended sentences, knowledge of poems and songs, the ability to listen and retell fairy tales, solve riddles. Of course, we should take such criteria calmly.

It must be remembered that we are going to teach a bilingual child to read in Russian in order to develop his speech and move towards the named criteria. And do not start, relying on them. Our baby can sing in English and not know a single Russian song, not be able to solve Russian riddles, but I would not particularly worry about this. His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

But , the phonemic readiness of is a key point for us. But there is some amazing news! It consists in the fact that this readiness in bilingual baby is formed easier than precisely because he had to learn to hear and pronounce twice as many sounds very early and his phonemic perception developed more intensively. In the world of sounds, a bilingual child is a much more serious expert than a monolingual child. It is very important for us to support and preserve this “experience of absorbing sounds” in order to develop literacy in Russian on its basis. Our language is phonetic, we write by ear. Spelling is important, but secondary to auditory writing skill.

What exactly do we need to form for a child's phonemic readiness? Let's make a short list:

The ability to clap words by syllables and the ability to say how many times clapped (name the number of syllables).

The ability to distinguish the first sound in a word.

The ability to name words for a given sound. For example, to the sound O or the sound A. (Not to the letter! The child will only learn letters🙂, while he already hears the sounds.)

The ability to select words to rhyme. And it doesn't really matter what language. Although, of course, it is very desirable that the child could name “words that sound similar” in Russian. For example, poppy varnish.

The ability to hear a certain sound in a word and the same sound in other words. For example, in the word mouse-sh-sh-shka you hear "wind song: sh-sh-sh-sh". Show objects that also have “wind song” in their name. You need to select pictures whose names contain the sound [Ш] from a set of cards on which, for example, are drawn: skis, tires, sleds, a car, a wheel. That is, the child must be able to differentiate consonants by ear. In this case W-W-S.

That is, the child must be able to differentiate consonants by ear. In this case W-W-S.

Is it necessary for a bilingual child to pronounce all the sounds of the Russian language clearly in order to learn to read Russian? I will express a seditious thought - no, not necessarily. Moreover, teaching reading in our country leads to two very important results: a significant improvement in pronunciation in Russian and the prevention of an English accent in it. In children with an English accent that has already appeared, it goes away, softens, and with regular and not at all difficult exercises, you can remove it.

It is highly desirable that the child could hold a pencil - paint, be able to draw straight and oblique lines. But this is usually done by most British children by the age of 4-5. Namely, at this age it is optimal to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian. Some a little earlier, some a little later, of course. As far as readiness, psychological and phonemic first of all.

We will finish for today, tomorrow I will tell you about how to develop phonemic hearing, since this aspect is key for us.

Have a good evening, Vika Tyazhelnikova.

When is the time to teach a child to read and how best to do it: a review of methods - Parents.ru

Montessori teacher

Why and when to learn to read

In Russia, as in most countries of the world, the standard 1st grade curriculum includes reading skills. But by default, it is believed that by this age the child should already be able to read, and parents tend to develop these skills earlier. Ekaterina Tupitsina, a teacher, suggests that before starting classes, determine their goal: “Often, parents think not so much about the needs of the child as about their own ambitions, so first of all you need to decide whether reading and writing is really necessary for a child at a particular age. If parents see that without these skills, his development is hindered: he loves books, strives for new knowledge, wants to write and express himself, you need to help him. But at the same time, it is important to take into account the peculiarities of the physical and social and personal development of the child.

But at the same time, it is important to take into account the peculiarities of the physical and social and personal development of the child.

-

From birth to 6 years old in a child, in a certain sequence, the parts of the brain that are responsible for the perception of information from the outside world, its processing, analysis and feedback (for example: we hear a sound - analyze it - remember the image of a letter - write).

-

At the age of 1.5−4 years the child actively communicates, develops conversational speech, as well as the ability to distinguish the sounds of the language. This is the basis of competent listening comprehension (including spelling and punctuation). In parallel, fine motor skills develop - the ability to hold a pencil and a pen and easily "manage" them. All this determines readiness for writing.

-

At the age of 3.5-4.5 years the child develops an interest in writing.

He leaves signatures under the drawings, first in the form of scribbles, and then, in order to make his inscriptions understandable to other people, he strives to master the letters of his native language.

He leaves signatures under the drawings, first in the form of scribbles, and then, in order to make his inscriptions understandable to other people, he strives to master the letters of his native language. -

At the age of 5-7 years, develops the ability to analyze and generalize symbolic information (letters) and translate it into specific images (sounds and words). At the same age, the child begins to be more interested in the lives of other people, their opinion, wants to know what is written by them. All this provides the need for reading and readiness for it.

It is important that early learning to read and write does not interfere with other developmental games and activities. The technique should be suitable for the child by age and be sure to be exciting and interesting to him.

In addition, according to the teacher-speech therapist Tatyana Kupriyanova, teaching a child to letters should begin when he has mastered sound analysis. First you need to learn to clearly distinguish sounds, not to confuse them, to pronounce them correctly.

First you need to learn to clearly distinguish sounds, not to confuse them, to pronounce them correctly.

Both parents and teachers in kindergartens should draw his attention to the sound of words, read poetry, pronounce tongue twisters, ask questions: for example, what sound do you hear at the beginning of the word “mother”, what at the end, etc. At 3− 4 years old children are more interested in the sound side of speech, they experiment with sounds, come up with their own combinations, new words. After that, by the age of 5, he begins to be interested in the letter designations of sounds and he can naturally move on to reading.

If you teach a child to read at an age when he still does not speak very well, pronounces many sounds incorrectly, does not distinguish them by ear, this can lead to dyslexia - reading disorders, and subsequently to dysgraphia (writing disorders). The fact is that initially he will incorrectly associate letters with their sound counterparts: for example, in the word “track”, instead of “g”, he hears and pronounces “s”, and this is how he will read this letter, confuse it in words.

Important tips

-

Tell stories to your child and with him: pause so that the baby can insert a familiar word himself.

-

Tell your baby about what he sees around: make simple sentences, later stories. Invite others to tell about what he saw, what happened to him.

-

Sculpt, play finger games, puzzle, string beads, play with grains and water. The development of fine motor skills will help the child quickly master the letter.

-

Draw children's attention to the letters everywhere: on the street, in your favorite book, on the TV screen, in their names and the names of loved ones.

-

Develop imagination: discuss what (or who) this or that letter looks like, and draw an image letter: the letter B is like a kangaroo with a bag for a cub, F is like a snowflake, C is like an elephant's ear.

-

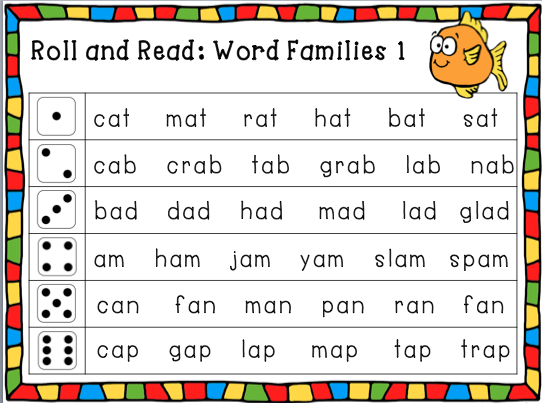

Play games with letters and syllables. For example, in a store, an adult calls the first syllable in a word (MA), and a child must find a product in which this syllable comes first (Pasta).

If your child likes to look at his photos, offer to come up with a one-word name for each (beach, park, football, etc.). Write the words on the cards and have your child arrange them under the corresponding pictures.

If your child likes to look at his photos, offer to come up with a one-word name for each (beach, park, football, etc.). Write the words on the cards and have your child arrange them under the corresponding pictures.

- Photo

- Getty Images/Westend61

Sound method

Until the middle of the 19th century, Russians were taught to read using the laborious letter-subjunctive method. First, the children memorized all the letters: az, beeches, lead, etc., then they crammed the syllables (beeches and az - “ba”), and only then did they start reading. This could take a long time, sometimes up to two years.

In contrast to the literal subjunctive method, teacher K.D. Ushinsky proposed to introduce the sound method of teaching literacy in schools. There is no need to memorize the names of letters, learning began with the selection of individual sounds from words, from which words are then formed. The teacher pronounced the sound, then showed how the corresponding letter was written. First, a simple vowel was taught (for example, "y"), and then a consonant was added (for example, "s"). The child was taught to draw a vowel sound and add a consonant to it. Then they read the syllable, where the consonant was the first, and the vowel was the second. To one syllable was added another, got the word. In general, according to this principle, education is conducted in the first grades to this day. It is used in primers, constantly refined and improved. The sound method is in good agreement with the structure of the Russian language - most words are read as they are written, there are few reading rules in Russian (unlike English or French).

The teacher pronounced the sound, then showed how the corresponding letter was written. First, a simple vowel was taught (for example, "y"), and then a consonant was added (for example, "s"). The child was taught to draw a vowel sound and add a consonant to it. Then they read the syllable, where the consonant was the first, and the vowel was the second. To one syllable was added another, got the word. In general, according to this principle, education is conducted in the first grades to this day. It is used in primers, constantly refined and improved. The sound method is in good agreement with the structure of the Russian language - most words are read as they are written, there are few reading rules in Russian (unlike English or French).

Sound method step by step:

-

Introduction to sounds and letters: the child learns to distinguish different sounds in words, learns that sounds are hard and soft, vowels and consonants, deaf and voiced, and that each sound has its own designation - letter.

-

Merging sounds into syllables: the child puts "m" and "a" into MA, etc. First there are syllables of two sounds, then of three or four, a soft and hard sign appears in them, several consonants go in a row or vowels.

-

Composing words from syllables: the child first puts together short words, and then more and more complex ones, gradually moves on to reading sentences and texts.

Method advantages: abundance of benefits, parents do not need special training to conduct classes. It is better to start targeted training using this method not earlier than 4-5 years old, because the child must understand the difference between deaf and voiced, soft and hard sounds, etc. Cons of the sound method: having learned to read in syllables, the child will read slowly mistakes. Perceiving the word in parts, children often do not understand the meaning of what they read (therefore, it is imperative to ask the child to say the whole word). The younger the child, the longer it will take to start reading cleanly.

The younger the child, the longer it will take to start reading cleanly.

Tatyana Kupriyanova, a speech pathologist, comments: “For teaching children at an early age, it is better to choose a speech therapy primer (authors Zhukova, Novotortseva). In them, letters are studied in a sequence that depends on the ease of pronouncing the corresponding sounds: first, the child gets acquainted with the designation of those sounds that he can accurately pronounce (simple vowels: a, o, y, etc.), and then with more complex ones. In school primers, the order of learning letters depends on the frequency of their use in Russian, and for a preschooler it can be difficult.

The method of whole words

The method, fundamentally opposite to the sound method, is known in Russia as the Glen Doman method. Doman created a system of physical rehabilitation, as well as the general development of intelligence, learning to count and read for children with disabilities, which later began to be applied to ordinary children.

The kid is asked to memorize whole words at once, which are written on a separate card in large red letters. According to Doman, having seen the word several times and hearing how it is pronounced, the child remembers it, and having learned a sufficient number of new words, he begins to read. Parents make cards and show them to the child several times a day, and you can start such classes from the first year of life. But kids are little interested in monotonous cards, and parents get tired of constantly making new ones. Or the child does not perceive words if they are not written on a card, but simply on a piece of paper with a pencil or printed in a book.

In addition, the technique was developed for the English language: it has complex reading rules and many short words that are easy to remember. The Russian language is arranged differently: the vast majority of words are pronounced the way they are written, and knowing the letters and sounds (or warehouses), you can read any new word without memorizing how it looks. In addition, words change in Russian, and memorizing, for example, the simple verb “is” in all its forms will be very laborious: I eat, you eat, he eats, etc. Therefore, experts recommend using such material as an addition to other classes on the development of speech and reading. Speech therapist teacher Tatyana Kupriyanova comments: “Doman's cards are effective for children with speech developmental disabilities: it is difficult for them to recognize the connection between sound and letter, and for them memorizing whole words is the key to starting reading. For ordinary children, cards can help develop visual memory, but they can’t teach them to fully read. If the goal is to make the child recognize individual words, captions under pictures, the technique will work, but the child can switch to conscious reading of new words only by learning to correlate letters with the sounds of his native speech. If the child remembers a lot of words from the cards, this will help him in the future to read faster those words that he already knows, but nothing more.

In addition, words change in Russian, and memorizing, for example, the simple verb “is” in all its forms will be very laborious: I eat, you eat, he eats, etc. Therefore, experts recommend using such material as an addition to other classes on the development of speech and reading. Speech therapist teacher Tatyana Kupriyanova comments: “Doman's cards are effective for children with speech developmental disabilities: it is difficult for them to recognize the connection between sound and letter, and for them memorizing whole words is the key to starting reading. For ordinary children, cards can help develop visual memory, but they can’t teach them to fully read. If the goal is to make the child recognize individual words, captions under pictures, the technique will work, but the child can switch to conscious reading of new words only by learning to correlate letters with the sounds of his native speech. If the child remembers a lot of words from the cards, this will help him in the future to read faster those words that he already knows, but nothing more.

- Photo

- Andrew Rich/Getty Images

The Montessori method

Montessori teacher Irina Gorbatko says: “The main differences of the Montessori method are a holistic approach to development, compliance with the natural needs of a child of each age, active use of fine motor skills and sensory perception. And unlike other methods, there is a completely different order of mastering skills: first, children learn to write letters, words, and even whole stories, and only then - to read. Learning to read according to the Montessori method is not a set of highly specialized manuals that are designed exclusively for teaching literacy, but a whole system of activities and games that gradually develop the child’s intellectual and motor abilities, preparing him for the emergence of writing and reading skills. The main idea of Montessori is that there is a time for everything: there is a natural period for the development of any skill, and if you impose something that is not interesting to him at the moment, there will be no result or the child will not use the skill. So, at about the age of 3.5-4 years, children accumulate a large vocabulary, are able to express thoughts with the help of words, achieve their goals (ask other children to do something, negotiate). Children of this age begin to be keenly interested in the symbolic designation of sounds - letters. They like to name sounds, play with letters, circle them, draw (after all, a letter is the same drawing). If this interest is maintained, at the age of 4-5 years, the child begins to spontaneously write single words and whole sentences. And by the age of 5, he learns to read without coercion, with interest, following the natural logic of speech development. The child writes to express his thoughts, and begins to read when he is able and willing to perceive the thoughts of another.

So, at about the age of 3.5-4 years, children accumulate a large vocabulary, are able to express thoughts with the help of words, achieve their goals (ask other children to do something, negotiate). Children of this age begin to be keenly interested in the symbolic designation of sounds - letters. They like to name sounds, play with letters, circle them, draw (after all, a letter is the same drawing). If this interest is maintained, at the age of 4-5 years, the child begins to spontaneously write single words and whole sentences. And by the age of 5, he learns to read without coercion, with interest, following the natural logic of speech development. The child writes to express his thoughts, and begins to read when he is able and willing to perceive the thoughts of another.

Montessori Reading:

-

Sound games. A box with compartments contains small items that have a certain sound in their name. Each cell has a letter representing that sound.

The teacher shows the objects and pronounces them, focusing on the desired sound. Thus, the child learns to isolate the sound at the beginning, in the middle, at the end of the word and subconsciously correlates it with the letter on the cell.

The teacher shows the objects and pronounces them, focusing on the desired sound. Thus, the child learns to isolate the sound at the beginning, in the middle, at the end of the word and subconsciously correlates it with the letter on the cell. -

Preparing the hand for writing. Using a special frame for preparing for writing and hatching, the child guides the pens through the slots, performing various movements containing letter elements. Exercises teach to correlate the movement of the hand and the eye, strengthen the fingers and make the child's hand more mobile.

-

Working with letters. One of the key benefits is "rough letters". These are letters made of rough material (like sandpaper). "Rough" letters are written because it is assumed that smooth circular motions are more accessible to children. The child remembers the alphabet better when tactile sensations are involved.

Training is carried out in a three-stage lesson. First, a presentation: an adult lays out a tablet, calls the sound (that is, not the letter “em”, but the sound “m”) and traces the outline of the letter with his finger. Gives the tablet to the child and invites him to circle the letter, naming it again. In one lesson, three letters are shown, in the next two already familiar and one or two new ones. At the second stage, the assimilation of information takes place: the adult asks one by one to show the letters or perform simple actions with them (put one letter on the edge of the table, take the second one for yourself or give it to another, etc.). If the second step is passed easily, we go to the third, if the child does not remember, we return him to the first step. The third stage is the verification and automation of knowledge. "What is it?" The teacher asks to name all three letters in turn, in order and randomly. After such a mini-lesson, the child is invited to repeat familiar letters on their own or try to depict them with their fingers on a tray of semolina.

First, a presentation: an adult lays out a tablet, calls the sound (that is, not the letter “em”, but the sound “m”) and traces the outline of the letter with his finger. Gives the tablet to the child and invites him to circle the letter, naming it again. In one lesson, three letters are shown, in the next two already familiar and one or two new ones. At the second stage, the assimilation of information takes place: the adult asks one by one to show the letters or perform simple actions with them (put one letter on the edge of the table, take the second one for yourself or give it to another, etc.). If the second step is passed easily, we go to the third, if the child does not remember, we return him to the first step. The third stage is the verification and automation of knowledge. "What is it?" The teacher asks to name all three letters in turn, in order and randomly. After such a mini-lesson, the child is invited to repeat familiar letters on their own or try to depict them with their fingers on a tray of semolina. Also, letters can be laid out from sticks or plasticine sausages. After some time, you can complicate the game - blindfold the child and offer to guess the letter by touch. It is even more difficult to put together a word from “rough” letters blindfolded.

Also, letters can be laid out from sticks or plasticine sausages. After some time, you can complicate the game - blindfold the child and offer to guess the letter by touch. It is even more difficult to put together a word from “rough” letters blindfolded.

-

Letter. The next stage - the child himself, when he is ready for this, begins to write letters with his finger on the semolina, with a stick on the sand, and then with a pencil on paper. Many children, in the words of Maria Montessori, have a real “explosion of writing”.

-

Compilation of words from the movable alphabet. In the cells of a wooden box, lowercase and uppercase letters are laid out, similar to "rough" letters. The teacher helps to match the letters in the mobile alphabet (also gradually, three or four letters at a time). Then he shows how they can be combined into syllables and words.

-

Reading. The actual reading begins with a series of cards.

Each card has a word and a picture representing the word. Depending on the level of difficulty, they are marked with a certain color. Pink - each letter in the word is pronounced as it is written. Green - words with iotized vowels after the consonant are added. Blue - difficulties in reading are introduced: unstressed vowels, unpronounceable consonants in the root, stunned consonants, b and b at the end of a word, combinations of ZhI-SHI, etc. The white series automates reading - there can be several different difficulties in a word. This is the so-called intuitive reading - when the child reads the whole word and the whole word is remembered. The child does not yet know how to read, but already reads, relying on his own intuition, visual memory and previously acquired knowledge.

Each card has a word and a picture representing the word. Depending on the level of difficulty, they are marked with a certain color. Pink - each letter in the word is pronounced as it is written. Green - words with iotized vowels after the consonant are added. Blue - difficulties in reading are introduced: unstressed vowels, unpronounceable consonants in the root, stunned consonants, b and b at the end of a word, combinations of ZhI-SHI, etc. The white series automates reading - there can be several different difficulties in a word. This is the so-called intuitive reading - when the child reads the whole word and the whole word is remembered. The child does not yet know how to read, but already reads, relying on his own intuition, visual memory and previously acquired knowledge. -

Development of reading skills. You can play a variety of games: lay out cards with words according to the domino principle (AngeL - Lemon - NosoK, etc.), make sentences from cards with individual words, pulling out strips of paper with tasks, perform them sequentially in order to eventually find the hidden “treasure”, etc.

Gradually, the child is offered simple picture books: at first it is just an object and its name, and then sentences and short texts.

Gradually, the child is offered simple picture books: at first it is just an object and its name, and then sentences and short texts.

The advantages of the Montessori method are development in several areas at once: general development of intelligence, development of speech, reading and writing skills, fine motor skills, logic. But classes according to the Montessori method require some preparation from an adult and the creation of special conditions - an equipped environment where children can fully communicate, play and learn.

- Photo

- Getty Images

The stock reading method

The stock method in teaching reading has been known since the time of Leo Tolstoy. It is not by letters and not immediately in whole words, but by warehouses that the baby begins to say: MA-MA, BA-BA. Hence the idea arose that it was easier and more natural for a child to read in warehouses.

Teaching children using the storage method requires parents to be constantly involved in the process: you need to systematically prepare for classes with the baby, come up with a variety of games so that he does not lose interest, because the learning material is always the same.

Zaitsev's Cubes

N.A. Zaitsev, who invented his famous cubes. A warehouse is a fusion of sounds: a consonant with a vowel, a consonant with a soft or hard sign, a separate vowel or consonant. For example, KO-RO-VA, KO-SH-KA and so on. Warehouses in Zaitsev's manual are located on the edges of cardboard cubes. These cubes differ in color, size, and the sound they make (thanks to the filling made of wood or "pieces of iron"). Such a variety helps children to feel the difference between vowels and consonants, voiced and deaf, soft and hard sounds. The set of manuals also includes tables on which all the warehouses of the Russian language are located at once, a book for adults with examples of tasks and a disk with songs-chants.

Methodist Oksana Oganezova comments: “You can start working with children using Zaitsev's cubes and tables from the age of one. First, children play with cubes: they build houses, roads, towers, trains out of them, listen to how they sound, pay attention to their color. Later, the guys begin to perform more complex tasks: for example, they line up all the cubes where there is a warehouse with the letter “o”, repeat the warehouses after the adult. All this helps the child to catch the patterns of reading. After some time, he begins to read the warehouses on his own, and then quietly moves on to reading whole words.

This technique requires adults to have a certain preparation and constant involvement: you need to systematically prepare for classes with the baby, constantly invent more and more new games to keep the child's interest (since the material is always the same). Zaitsev's manuals are more suitable for group activities in a development center or kindergarten, since many games have a competitive element. In addition, teachers, as a rule, combine work on blocks with other tasks - they introduce children to individual sounds and letters. If you manage to organize everything correctly, the child studies with pleasure, perceives learning as a game, and by the age of 3-4 masters reading.

In addition, teachers, as a rule, combine work on blocks with other tasks - they introduce children to individual sounds and letters. If you manage to organize everything correctly, the child studies with pleasure, perceives learning as a game, and by the age of 3-4 masters reading.

Skladushki by Voskobovich

Skladushki is a game for learning to read, created by Vyacheslav Voskobovich, the author of about 40 educational aids for children. Children 3-5 years old are introduced to reading in a warehouse system. Warehouses are located on 21 cards in two columns, from which you can build houses for the inhabitants of the city of Skladinsk, about which educational tales and songs are composed. The game comes with a book and a CD.

The child, together with an adult, examines the drawings on the cards, reads poetry, tells fairy tales and sings. He gradually memorizes warehouse songs, sings them, shows the corresponding warehouses with his finger on the cards. Then, having memorized warehouses, he learns to make words out of them, to read individual words, and then short sentences. The manual can be used in games of varying degrees of difficulty, so it is suitable for both three-year-olds and older preschoolers.

The manual can be used in games of varying degrees of difficulty, so it is suitable for both three-year-olds and older preschoolers.

In addition to "Skladushki" there are other games by Voskobovich: for example, a constructor, from the parts of which you can assemble letters in order to better remember how they look. Or the Chamomile lacing game, where the child needs to thread the string through the holes with letters in the sequence that corresponds to the spelling of a word.

The technique works most effectively if children study in a small group (4-7 people). The developers claim that by playing for half an hour twice a week, a three-year-old child can learn to read in six months, and six-year-olds in just a month.

Blocks “I read easily”

Another modern textbook for warehousing is the blocks developed by teacher Evgeny Chaplygin. They are intended for children from three years of age. The “I read easily” technique is based on a gradual, very smooth, development of reading; there are more games than in Zaitsev's program. The set of benefits compared to many other methods is modest: 10 simple wooden cubes, 10 double movable cubes and a “cheat book” for parents, which gives recommendations for conducting classes. Movable cubes connected by platforms can be scrolled to get new warehouses and new words. Children turn them with pleasure, turning the word MAMA into the word MASHA with one turn. The combinations of letters on the cubes are chosen in such a way that 20 words can be made from two dynamic cubes, and as many as 500 words from three.

The set of benefits compared to many other methods is modest: 10 simple wooden cubes, 10 double movable cubes and a “cheat book” for parents, which gives recommendations for conducting classes. Movable cubes connected by platforms can be scrolled to get new warehouses and new words. Children turn them with pleasure, turning the word MAMA into the word MASHA with one turn. The combinations of letters on the cubes are chosen in such a way that 20 words can be made from two dynamic cubes, and as many as 500 words from three.

In principle, there are no pictures in the manual so as not to confuse the child, because the child can understand the illustration for the word “dad” as “man”, “man”, “uncle” and as a result will remember the word incorrectly. If the child really wants a picture, he can draw it himself in the book for parents.

Advantages of the method: manuals do not need to be done by yourself, classes can be done at home, and no special training from an adult is required.