When do you learn how to read

When Do Kids Learn to Read?

By Tara Drinks

At a glance

Learning to read is a process that involves different skills.

Kids start to learn to read at different ages.

Some kids need extra help learning how to read.

Learning to read is a process that involves different language skills. It happens over time, so it’s hard to say exactly when kids learn to read. To some people, reading means being able to sound out words and recognize words that can’t be sounded out. To others, reading means being able to read and understand sentences and text.

Learning to read is different for every child. Some kids start to learn to read in daycare or preschool. Others start gaining the skills in kindergarten or first grade. Read on to learn more.

At what age do kids learn to read?

Kids develop reading skills at their own pace. And some kids learn earlier and more quickly than others. Here’s what reading typically looks like at different ages:

- By age 2, kids often start to recite the words to their favorite books. They also start to answer questions about what they see in books.

- In preschool, kids typically start to recognize about half the letters of the alphabet. They also start to notice words that rhyme.

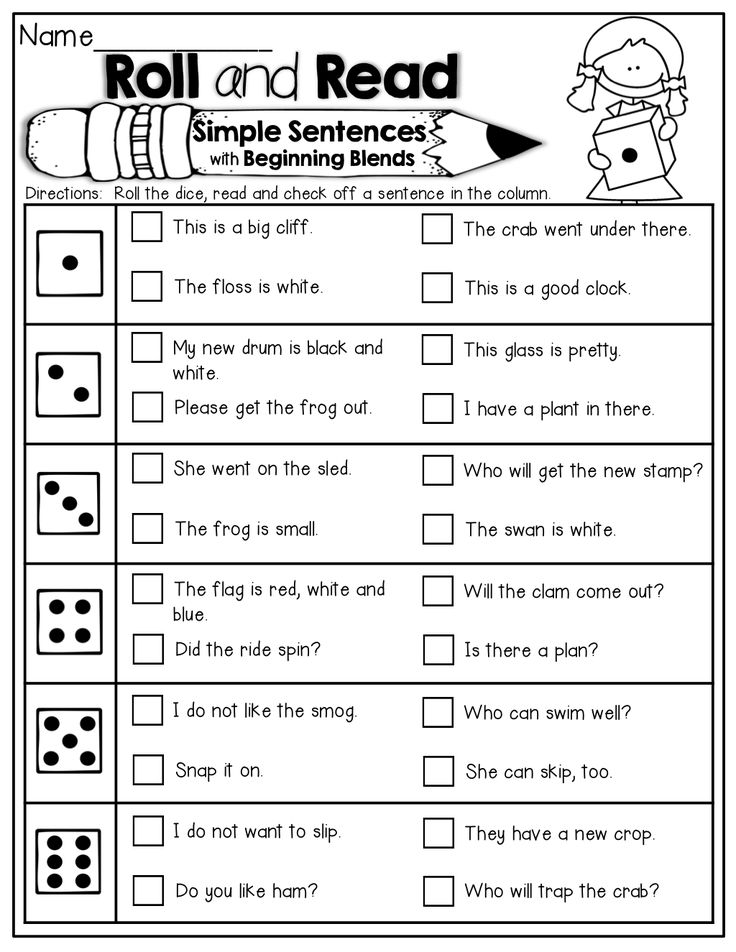

- In kindergarten, kids often start matching letters to sounds. They also start to recognize some words by sight without having to sound them out.

- By second grade, most kids can sound out and recognize words and can read and understand sentences. Most people consider this as having learned to read.

Keep in mind that every child is different. Not all kids develop reading skills at the same rate. Taking longer doesn’t mean they’re not on track to become good readers.

Why kids might have trouble learning to read

Learning how to read can be challenging for some kids. But that doesn’t mean they’re not smart. They just may need extra time and support to become full-fledged readers.

But that doesn’t mean they’re not smart. They just may need extra time and support to become full-fledged readers.

There are many reasons why kids have trouble learning to read. Some have a hard time understanding how language works. For example, they may struggle with recognizing sounds in words or matching sounds to letters.

In some cases, the type of reading instruction plays a role. Learn more about what can cause trouble with reading.

What helps kids learn to read

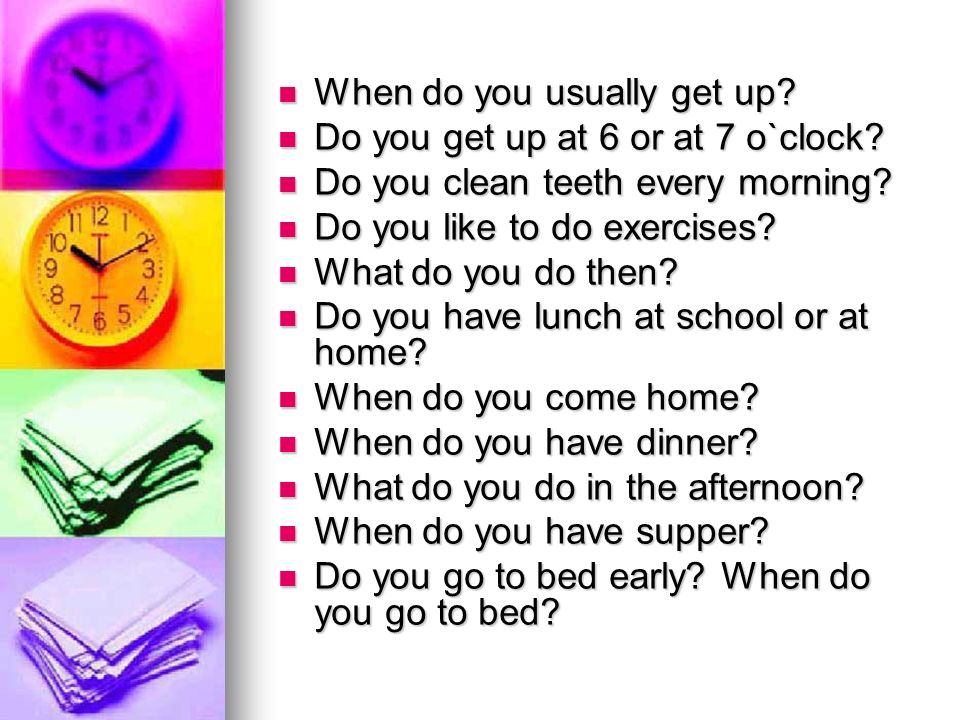

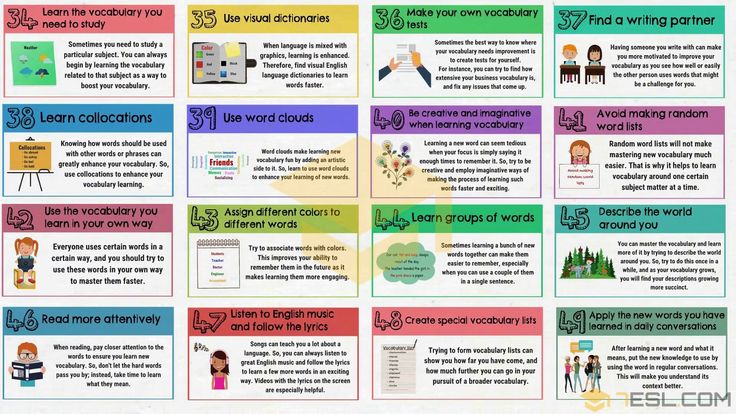

Practicing at home can help kids improve reading skills. Here are some ideas parents and caregivers can try and teachers can suggest:

- Make reading a habit. Kids learn from what they observe. Try reading a book together every night before bedtime.

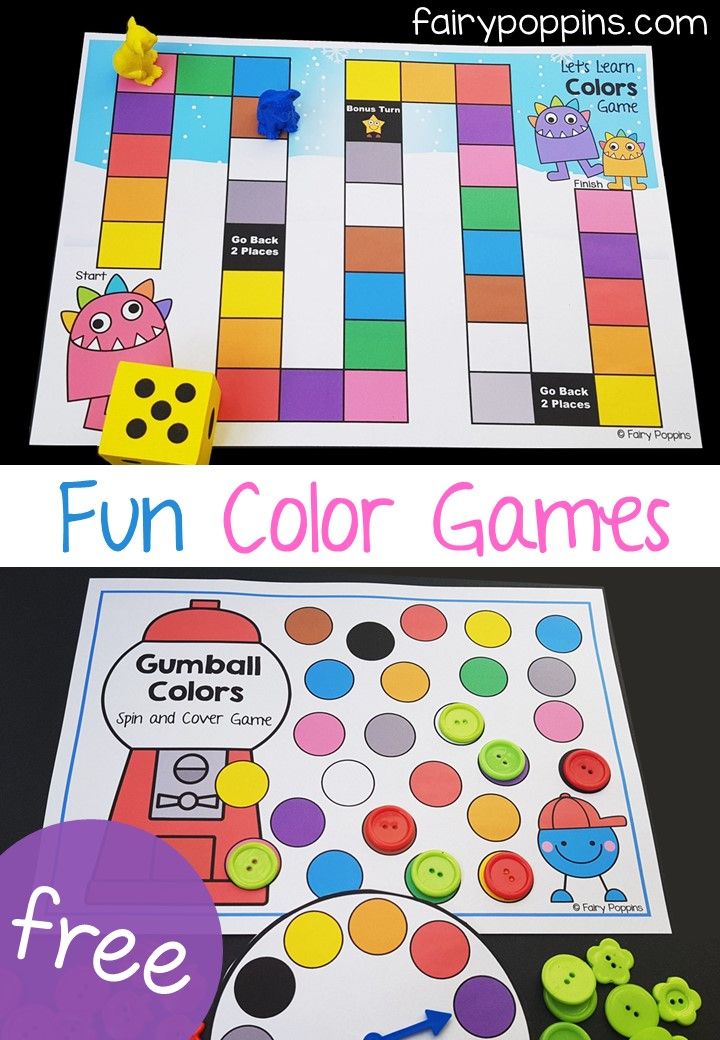

- Play reading games. While running errands, have kids read the road signs out loud. Or play rhyming games together.

- Have conversations. Talk about things you’re seeing or feeling and ask questions so kids can do the same.

This helps build the language skills kids need to be strong readers.

This helps build the language skills kids need to be strong readers.

Get more ideas to help kids with reading.

Key takeaways

By second grade, many kids can read and understand sentences.

Play reading games and have conversations to help kids learn to read.

Learning to read can be challenging for some kids, but that doesn’t mean they’re not smart.

Related topics

Reading and writing

Tell us what interests you

About the author

About the author

Tara Drinks is an associate editor at Understood.

Reviewed by

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Babbin, EdD is an instructional specialist at Lower Macungie Middle School in Macungie, Pennsylvania.

When Do Kids Learn To Read: A Helpful Guide

Whether you are about to have your first child or you’re in the middle of raising number two or three, you may be wondering: when do kids learn to read?

This is a legitimate question, but there is no one-size-fits-all answer. That’s why we’re here to show you how to encourage your child and help them learn to read in fun, uplifting ways!

That’s why we’re here to show you how to encourage your child and help them learn to read in fun, uplifting ways!

Cracking The Reading Code

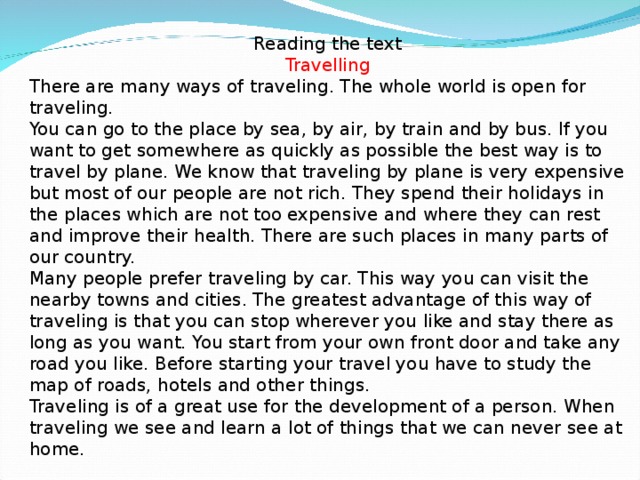

Most children learn to speak — either verbally or in sign — through exposure. This happens naturally and without direct instruction. But the more you speak with your child the more you impact their receptive and expressive language which, in turn, can impact their reading.

Unlike speaking, children can’t pick up reading through natural language processes. Instead, we have to teach them how to “crack the code” of written language.

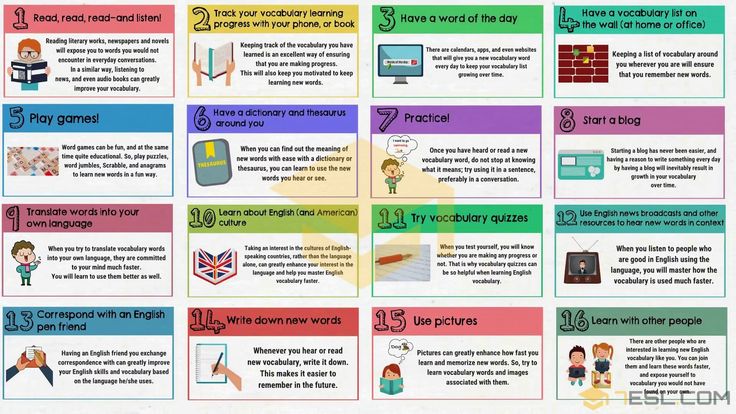

First, children must understand that words are made up of individual sounds (or phonemes) and that each sound is matched to a letter. To crack the reading code, a child must learn to hear sounds in words and to pair them with letters, eventually blending the sounds together to read.

As you might have guessed, learning to read can take time. So, to give you a clearer picture of the overall learning process, here’s a brief look at the pre-reading skills your child will develop (in no particular order) throughout their literacy journey.

Pre-Reading Skills

Phonological Awareness

Phonological awareness is an understanding of sounds in our language and how they relate to each other. This includes segmenting sounds and syllables in words, rhyming, and blending syllables and sounds together to form words.

Alphabet Knowledge

As the name suggests, alphabet knowledge is the ability to both recognize and name the letters of the alphabet.

Print Awareness

Print awareness is a broad term that includes familiarity with different forms of text (books, menus, newspapers, magazines, etc.), understanding print structure, and knowing how to hold these sources of information correctly.

Without print awareness, it’s hard to connect text in a meaningful way and understand the words and phrases on a page.

Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate sounds in a written word.

This skill is often mistaken for phonological awareness, but it is actually a subset of phonological awareness. Phonemic awareness focuses on identifying and manipulating individual sounds, known as phonemes.

Phonemic awareness focuses on identifying and manipulating individual sounds, known as phonemes.

While it might take your child a while to master each of the skills above, they are the building blocks of the reading (and writing) journey. With practice and patience, your young learner will be grabbing their favorite book and reading it all by themselves before you know it.

When that will happen depends on several factors and varies from child to child. Let’s take a closer look!

When Do Kids Learn To Read?

When it comes to reading, all kids are different. When your child learns to read and when another child their age learns to read may be a year (or more) apart. That’s OK! It’s all part of kids’ uniqueness.

When your child learns to read may also depend on their pre-reading engagement — in other words, how often they’re exposed to reading.

For example, kids who are read to, who have parents modeling a love of reading, and who have books as part of their everyday life tend to be more excited to learn to read. These children also develop essential pre-literacy skills, such as print awareness.

These children also develop essential pre-literacy skills, such as print awareness.

Another thing to keep in mind is that your child’s reading development is directly impacted by how much they read, especially independently.

Rather than worrying about a precise timeline, it’s better to keep in mind a generalized idea of what milestones your child can reach at different ages.

Let’s take a look at those milestones (or benchmarks) below.

Reading Benchmarks By Age

Babies (Under 1 Year Old)

Babies may begin using board books or soft books to play with.

Books with lots of colorful illustrations and dynamic storytelling will help engage your baby and foster a love of reading right from the start.

Although your baby can’t talk yet, keep an ear out for any noises they make in response to your reading. Cooing and other noises can help signify that your baby is paying attention, having fun, and bonding with you while learning.

Toddlers (1 To 2 Years Old)

As they grow older, your baby’s cooing might evolve into some very enthusiastic baby babble. They may giggle and chatter in their own unique baby language in response to your story narrations.

They may giggle and chatter in their own unique baby language in response to your story narrations.

By 18 months, most children move on from babbling to using words. Their vocabulary increases every day! You can take advantage of this vocabulary explosion when you share books that have pictures of things they love.

To encourage them, you can point to illustrations or pictures and ask, “What’s that?”

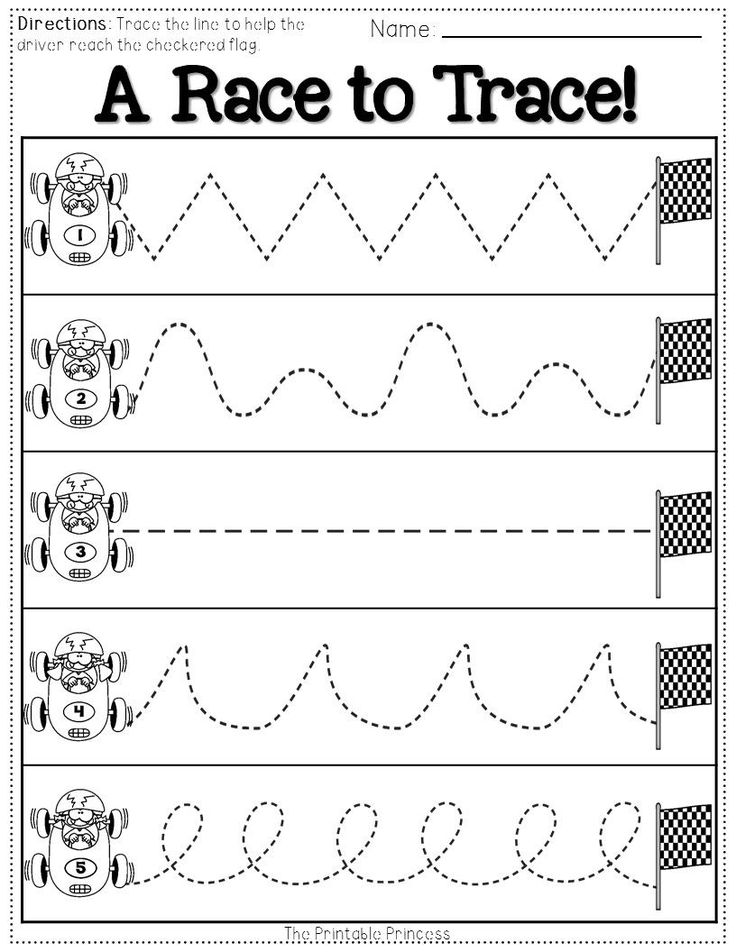

Getting them physically involved helps, too. If you would like to try this, start by holding their hand in yours as they turn the page. This will develop their motor skills and mimic what real reading feels like.

You can also run your finger along the print, showing that the words are important and that you follow them from left to right. This helps develop print awareness.

Preschool-Aged (3 To 4 Years Old)

Now is when the initial groundwork you laid when your child was a baby begins to pay off! Keep in mind, though, that there is a large difference in what a beginning three-year-old and a late four-year-old can do.

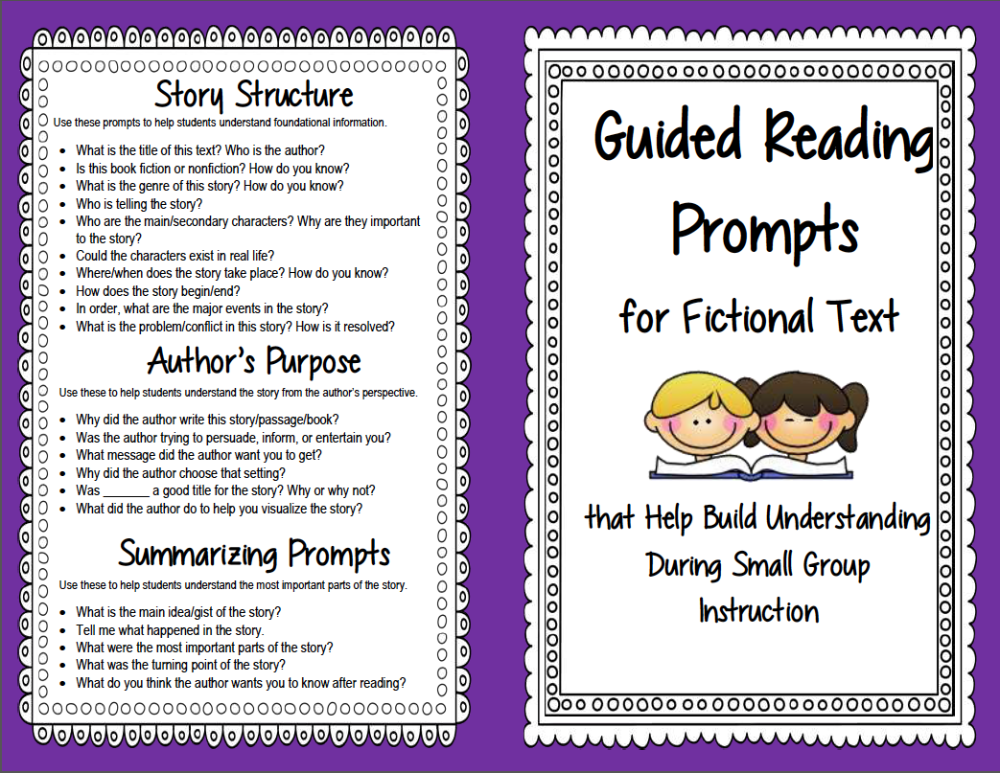

As your child moves through preschool education, they’re introduced to more fundamentals about books and reading. A three-year-old may start to understand how to identify different parts of a book — the spine, title, cover, and author.

They may also be able to tell you what the story was about in basic terms (a shark who loves cupcakes, a puppy who can ride a bike, and so on).

Three- and four-year-olds are beginning to develop ideas about the alphabet and to attribute sounds to letters. They are also ready to engage in listening games that will promote their ability to use phonics as beginning readers.

You can boost their phonics confidence by singing lullabies or nursery rhymes with them. Enrich the experience by clapping!

Learning to sing the alphabet also usually comes by the end of the preschool years. This is a great time to encourage your child to explore recognizing at least half of the alphabetic letters and having a go at writing their own name.

Kindergarteners (5 To 6 Years Old)

Formal introduction to “sounding out” or decoding words begins at this age. As part of this work, your child will benefit from learning to hear individual phonemes (single letter sounds) in words — a foundational skill for sounding out words.

As part of this work, your child will benefit from learning to hear individual phonemes (single letter sounds) in words — a foundational skill for sounding out words.

Beginning to learn sight words is also important at this age, as sight words don’t always follow regular phonemic patterns (they don’t sound the way they’re spelled).

For ideas on how to incorporate sight word learning into your routine, check out our article 4 Highly Effective and Fun Sight Word Games To Help Your Kids Learn.

To help build your Kindergartener’s reading confidence, prompt them to summarize what happened in the story while you read with them. To make it fun, you can play the silly, forgetful parent!

Asking simple questions about the story helps your child get their brain working and helps you know if they understood the book.

Young Elementary (6 To 7 Years Old)

At this age, children learn more advanced phonics, such as:

- Silent e

- Vowel teams like ai and oa

- Vowels controlled by R to make er, ir, ur, ar, or

- And more.

Your child may begin receiving weekly vocabulary word banks to learn. They will also be exposed to common spelling rules and patterns.

Additionally, when you see your child re-reading their favorite books, know that they’re building strong fluency. This helps them engage more deeply with the texts and investigate words that might be unfamiliar.

To foster a love of reading in your child at this age, you can help them draw conclusions and parallels between things in their life and the things they read.

After all, reading is about making new connections to familiar facts that your child knows and loves, as well as exploring unfamiliar ideas!

Older Elementary (8 To 10 Years Old )

During these years, your child is likely moving away from learning to read — instead, they’re reading to learn.

They may choose to read independently more often. They may read for pleasure or to explore their own interests, as well as answering questions about the text and looking for real-world examples.

That being said, even after children are independent readers, it’s a good idea to continue to read aloud. This is an opportunity to share books that are more difficult for them to read on their own.

It can also be good for you to read books that your child reads either on their own or for school and talk about them together, like a book club! This can be a fun way to connect with your child and spend more time together.

Tips For Boosting Your Child’s Reading Confidence

There are plenty of simple things you can do to help your child learn to read — but first and foremost, we want to help your child think of reading as fun, relaxing, and rewarding.

While you’re reading with your little one, consider treating reading aloud as a bonding time or a special activity, rather than a school lesson. We don’t want you or your child stressed out!

Remember: reading confidence comes with time and practice. It’s OK if your child learns differently than their friends –– that’s completely normal!

With that said, here are some bonus tips to help boost your child’s confidence and encourage them to read.

Read, Talk, And Sing To Your Baby

If you want to get a head start on encouraging a love of reading in your child, talk and read to them as much as possible when they’re a baby, and don’t stop — even after your child is an independent reader!

While you’re reading, you can react to illustrations and repeat words for an even bigger impact. Although your baby can’t speak yet (so you’re not sure if it’s paying off), we promise it’s worth it!

Finally, as we mentioned earlier, singing lullabies and nursery rhymes is also a great way to expose babies, toddlers, and preschool children to words.

Show Your Child That Words Are Everywhere

Once your child has moved into the toddler stage — and as they continue to grow — point out letters and numbers to them as you walk along in everyday life. They will begin to take notice (and probably want to read themselves!).

You can even make it fun by turning it into a game once your little one starts learning sight words (“I spy with my little eye the word red”).

Talk In Order To Read

This one sounds simple, but talking to your child helps to improve their vocabulary and knowledge base. If you’re looking for ways to talk to your child more, here are some ideas:

- Ask specific questions (such as “What did you do at school today?”)

- Explain what you’re doing while cooking

- Tell them about a favorite memory from your own childhood

Conversations help children with speaking and listening skills, and familiarity with new words and subjects will help when they read books. As a bonus, having conversations with your child helps you connect as a family!

Take Turns Reading

It’s important for kids to know what fluent reading sounds like. Listening to you can be a huge help!

If you’d like to try this during storytime, take turns reading pages. (You read a page, then your child reads a page.) You can customize the split depending on your child’s energy, reading level, or how much time you have.

Switching on and off will give them a mental break in-between pages and keep them excited about reading with you!

4 Fun Activities To Develop Reading Skills

In addition to the tips above, here are some fun activities to try at home with your young learner as they develop their reading skills.

1) Sight Word Scavenger Hunt

Sight words are words that appear often in text. These are words such as the, on, have, was, what, etc. These words can be tricky because they aren’t easy to sound out or decode, so we need to memorize them or recognize them by sight.

Since they are seen so frequently, helping children get comfortable with sight words allows them to read more confidently and fluently.

To practice this skill, one of our favorite sight word games is Sight Word Scavenger Hunt. All you need for this game is a marker, index cards, and a sheet of paper.

Start by writing down 10 sight words (one on each card), and then hide these cards in places around the house. (Be sure to choose spots familiar to your child.)

(Be sure to choose spots familiar to your child.)

The goal of this game is simple: Have your child find all the cards by listening to clues you’ve written down on your sheet of paper.

For example:

- I climbed ____ the chair — On!

- What word rhymes with buzz? — Was!

As you call out each clue, your child will search for the sight word that matches. You can also write the sight words on a separate piece of paper as a reference for them if needed.

And to make things even more interesting, feel free to add a timer into the game and see how fast they can find the cards!

2) Become An Author

Children are natural storytellers. They want to share their adventures, ideas, and thoughts. In fact, it is sometimes hard to get them to stop talking!

You can take advantage of this love of oral language to make a bridge toward written language. How? Write a book together.

All you’ll need is an empty booklet (this can be blank pieces of paper stapled together), a pencil, and some crayons. Start writing the story by asking your child to describe something meaningful to them, such as what they did at school or while visiting their grandparents.

Start writing the story by asking your child to describe something meaningful to them, such as what they did at school or while visiting their grandparents.

As your child narrates their story, write down about one to two sentences on each page. Keep in mind that you don’t actually need to write the exact words. It is fine to write a sentence that expresses the main parts of your child’s dictation.

You might need to ask prompting questions to give the story more details, such as:

- Was it a hot or cold day?

- Was your grandma wearing a sweater? What color was it?

- What did you have for lunch on that day?

Once the story is complete, your child can add some illustrations to help bring it to life. And just like that, you have a homemade storybook that you can enjoy reading together!

3) What Starts With…

Learning the alphabet and letter-sound connections is an essential step to reading fluently. You can help your child work on these skills by playing a guessing game that focuses on all their favorite words.

What letter does balloon start with? How about pizza?

When your child guesses correctly, encourage them to come up with more words that start with the same letter. For example, “Balloon starts with a b! So does basket, butterfly, baby, bubbles, buttons, and ball!”

This repetition will help reinforce the letter-sound connections that play an important role in reading (and writing).

4) Pick The Word

This game also focuses on sight words. To get started, write six sight words down on index cards, one word per card. On a separate sheet of paper, list the same words twice. One list will be for you and the other for your child.

Next, place the index cards with the words facing down on a flat surface (i.e., table). Begin playing by picking a word from your list. Then, flip four cards over so the words are facing up. If you flip over the word you selected, cross it off your list and flip the other cards back over.

If you don’t find the word you were looking for, you’ll need to wait for your next turn to try to find another one. Remember to mix the cards up before the next player starts.

Remember to mix the cards up before the next player starts.

The first player to cross off four words from their list wins!

This is a great game for continued sight word exposure. The more familiar your child gets with them, the more confident they’ll be while reading.

When Do Kids Learn To Read: FAQs

Why Does My Child Have Trouble Reading?

If your child isn’t the first to read in their class, it doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with them. They may just need some more time and support to develop their abilities. That’s OK! Every child learns at their own pace.

Learning to read is quite a lengthy process and involves a multitude of skills, and some kids may find it more challenging than others. There are various reasons for this.

Some children might struggle with the type of reading instruction used in class. Others may find it difficult to understand how language works (e.g., matching sounds to letters or recognizing the sounds in words).

No matter what the reason is, there are things you can do to help.

Supporting children in their early years is essential to the HOMER team. That’s why our Learn & Grow app focuses on multiple key developmental areas, including early childhood reading.

Our experts developed it to provide a personalized pathway that builds essential skills — from letters and sounds to sight words and, eventually, reading and spelling.

Why Is My Youngest Child Not Reading When My Oldest Did?

When it comes to children’s literacy journeys, the last thing you want to do is compare your own children to each other, their friends, cousins, or peers in school. As you already know, kids are very different, so they will hit milestones at different times.

If your oldest started reading at four or five years old, that’s great, but don’t expect your youngest to do the same.

Also, keep in mind that while some kids might start earlier, according to the U.S Department of Education, children generally begin reading at around six or seven years of age (first or second grade).

Who Can I Reach Out To If I Think Something’s Wrong?

Even though it’s normal for children to learn to read at different ages, sometimes medical concerns may get in the way. Or, in some cases, children have trouble reading because they have a learning difference and might need special instruction before they can learn to read fluently.

If you suspect this is the case with your child, talk to the teacher or ask to meet with the school learning specialist. They will know if the issue is developmental or if there are underlying problems you’ll want to address.

You can also reach out to a local reading specialist (outside of your child’s school) who may be able to assess your child first and help you determine if there are additional things to address. They’ll be able to guide you in the right direction.

There Is No “Right” Time

No matter when your child learns to read, don’t worry! With a little love and support from you, they will get there in their own time. If you’re ever concerned, feel free to reach out to your child’s teacher or another professional.

If you’re ever concerned, feel free to reach out to your child’s teacher or another professional.

As you continue to help your child learn to read, keep the benchmarks and tips we mentioned above in mind. But remember that what’s most important is engaging your child in ways that are fun, stimulating, and don’t add stress to your family’s already busy schedule.

Making reading time fun and light helps build your child’s confidence and love for learning!

Finally, if you find yourself needing a little support along the way, try our HOMER Learn & Grow app to help your child thrive on their reading journey!

Author

Home - for the population

- Maps of medical organizations

- Vaccination

- Dispensirization

- Fluorography

- Address and work clinic

- Trauma 9000

- Oncology

- Where to hand over the test for HIV 9000 9000 Cabinet

- Services

- CVD Prevention

- Disease Prevention

- World Patient Safety Day

- Newspaper "Medical News"

- Ask a question to a specialist FOLLOWING SPIRITUAL HARMONY

“About children, even about babies, it can be said that the environment of mechanical perfection is not very suitable for them.

They need human beings around who can both succeed and fail.

They need human beings around who can both succeed and fail. I like to use the words "good enough". Good enough parents are good enough for children, and good enough parents are you and me. To be consistent and therefore predictable for children, we need to be ourselves.”

Donald Woods Winnicott

"Conversation with parents"

This article is devoted to the entry of the child into the mode of schooling, i.e. adaptation to a new class and to a new social role.

How to help a child adapt to a new class and a new social role?

The tone of the child's learning and communication at school is probably set by the teacher, but the shades of interaction in a particular class depend on all participants in the training: students and teachers, parents and school administration. Therefore, tune in “to the positive” yourself and set up the child:

1) The child feels the mood of the adult, be ready to let the child go into the "new waters".

Avoid the school bullying method (“Are you making mistakes again!? At school you will be given a deuce for this”), form a positive attitude towards school and emphasize its importance for all family members.

2) Tell your child what a school is for (this is a place where a person receives knowledge accumulated over generations and learns to acquire new ones), what he will get in it (learn why the leaves turn red in autumn, how the Internet works, how to sew a dress yourself, etc. .). It is necessary that the school attract the child with its main activity - teaching (“I will learn to read”, “I want to study in order to be like a mother”).

Explain that at school the child has his own rights and obligations, that there is a certain structure of communication with the teacher (tell us about your school childhood, show school photos, tell in detail about the rules of conduct).

3) Remember yourself that the family will gradually fade into the background, but still play a significant role in the life of the child.

And one of the tasks of parents is to be reliable, consistent, to be “good enough” to provide support and help the child to realize himself.

And one of the tasks of parents is to be reliable, consistent, to be “good enough” to provide support and help the child to realize himself. 4) Get to know the school, the teacher, the class in advance.

5) Choose with your child his future school supplies (uniform, backpack, pens, paints, notebooks, etc.): this will support his desire to complete educational tasks. Gather the whole family for a festive dinner, go to the cinema, etc.: show the child and yourself that a new, exciting, but significant stage in the life of the child, his growing up, has begun.

The period of adaptation of the child is not particularly difficult if you understand what is happening with the child at this stage

Usually, by the age of 6-7, the child is physiologically, emotionally, mentally, etc., ready to change the type of activity: playing to learning. Moreover, he looks forward to a new learning experience: children are ready to “step over the fence”, into the unknown, they are drawn to the new.

On the other hand, this new is sometimes frightening, so the child must feel that he will be able to return back to the familiar world in order to gain strength, relax and go “outside the fence” again. The desire for such a return is usually manifested in past and forgotten forms of behavior (distorting speech, whims, a finger in the mouth, turning to forgotten toys, etc.). Feeling your support, the child will be ready to explore new horizons.

On the other hand, this new is sometimes frightening, so the child must feel that he will be able to return back to the familiar world in order to gain strength, relax and go “outside the fence” again. The desire for such a return is usually manifested in past and forgotten forms of behavior (distorting speech, whims, a finger in the mouth, turning to forgotten toys, etc.). Feeling your support, the child will be ready to explore new horizons. An important acquisition of the child, approximately from the age of 6, will be a sense of "skill" (or, in the case of a negative passage of the stage, a sense of "inferiority"): the child's interest in how things are arranged, how they can be used and adapted. If adults give the child the opportunity to make, build, study, help to bring the matter to the end, cooperate with him, praise him for the result, then the child develops “skill” and a creative attitude towards the world, diligence develops, a feeling arises: “I like to act and achieve results, it gives me the recognition of others.

The child begins to form his self-esteem, based on real achievements, in the future this will form his idea of himself as a competent, capable person.

The child begins to form his self-esteem, based on real achievements, in the future this will form his idea of himself as a competent, capable person. It is very important for a child to know how parents evaluate him and what they expect from him. All the nuances, shades that the child feels in relation to his parents are extremely important for him. From them, the child develops a sense of faith, empathy and love of parents.

Let's imagine a situation: a schoolchild shows his parents a class work with a mark of "5". The reaction of parents may be different, for example:

- “Did anyone help you with this work? Have you copied from someone?

- "I told you (a) - you can whenever you want"

- "I am pleased with you (happy)"

- "Well done. I'm happy for you".

As a rule, parents do not think about the emotional meaning of these remarks, and for a child they can carry a different emotional burden. These phrases for a child can mean the following:

- "I don't believe you did it yourself"

- "I know you are lazy"

- “I am satisfied (happy) with you only when you get fives.

You study for me"

- "I share your joy with pleasure."

Teach your child to evaluate the result of their activities (but do not evaluate the personality of your child). Compare: “you went beyond the outline of the drawing” and “you are always so sloppy when you learn to be attentive!”. Do not demand from the child to be an excellent student, but support the child's self-confidence: give him the opportunity to correct a mistake, remember that a mistake is a natural, normal and inevitable phenomenon.

It is quite difficult to predict what will happen at school, but you can prepare yourself and your child. The most common adaptation difficulties are:

1) "Regular difficulties" consist in the inability to perform certain training moments at a strictly defined time, as well as the need not just to do something, but to pay attention to the quality of work.

Often the tension is due to the fact that someone in the learning process needs to be slower, and someone faster.

If you know what to expect from your child, then talk to a teacher who knows all these patterns well and who is ready to “let go of the leash” and help your child. It is possible that he will give you a series of exercises or help with advice: for example, do tasks with the child (but not instead of him), tell a fairy tale or story (the so-called game form of learning), or help you find information about ways to develop memory, attention .

If you know what to expect from your child, then talk to a teacher who knows all these patterns well and who is ready to “let go of the leash” and help your child. It is possible that he will give you a series of exercises or help with advice: for example, do tasks with the child (but not instead of him), tell a fairy tale or story (the so-called game form of learning), or help you find information about ways to develop memory, attention . For successful entry into the school regime, the physical health of the child is also important - this is the reserve of strength that largely determines the success of both the first year of study and the entire school marathon. Develop the child's motor sphere: for example, with the help of psycho-gymnastics exercises (which brings muscles into optimal tone and improves the state of the nervous system), physical education and walks, and an optimal study-rest regimen. The articles in this booklet will tell you about the prevention of childhood diseases.

2) "Communication difficulties" - unwillingness to make contact with others or inability to organize communication, as well as difficulties arising in relationships with the teacher. Try to understand what is happening, what caused this behavior and find a solution that satisfies all parties.

Talk to the teacher and find the cause of the difficulties: your child may lack attention (and then you can ask him to include him in some class activities or give simple assignments in which he feels his importance) or the child may be lonely due to the fact that it is difficult for him to get acquainted (and then you can play the game “Let's get acquainted” with him, etc.).

Try not to express any dissatisfaction with the child until you establish contact with him, especially at the time of his return from school.

Be creative, be kind, be flexible. Remember that the growth of a child is not all honey for him, and for the mother it is often a bitter cup.

3) Personal safety issues (eg injuries during breaks). As a rule, the school administration gives parents recommendations for the prevention of such situations at school meetings.

At home, convey these safety rules to your child: for example, that if everyone rides from the railing, then it is not necessary to repeat this, but you can run in the gym.

School age is the period when a child needs support and understanding from his parents, empathy for his joys and sorrows. The main task of parents in this period is to help the child accept a new social role - the role of a schoolchild.

In conclusion, we note that parents intuitively understand all of the above and act as they should, and when parents ask questions, they often need not advice on how to act and what to do, but an understanding of what is happening.

You have the right to expect your child to show insecurity, anxiety, fear. Trust that he can do it, and know that from time to time he will want and need to return from the outside world to his own enclosure: the familiar environment, your presence, love, support and acceptance - which the family ultimately provides.

For qualified assistance, you can contact:

To the psychologist of UIA "City Center for Medical Prevention", tel. (343) 295-14-90, and also, ask a question by mail [email protected]

90,000 adaptation of the child to schoolHome - for the population

- Medical Organizations Map

- Vaccination

- Dispensirization

- Fluorography

- Addresses and work clinic

- Trauma 9000

- Where to pass the test for HIV 9000 9000 9000 healthy child

- Services

- CVD prevention

- Disease prevention

- World Safety Day

- Medical Vesti newspaper

- Ask a specialist

- Health School

-Advisory Department

- Psychological Assistance

- Group Interactive classes

- Psychological training school 9000 9000 Useful articles

- Tests

- Paid non-medical services

– Useful articles

- Group therapy

- Friends or psychologists

- The charm of maturity

- Why do people fall in love more often in spring?

- Save money on a psychologist.

Memo to parents

Memo to parents - For parents and children

- For students

- About stress and depression

- About the benefits of laughter

- Family traditions

- Music therapy

This article is devoted to the entry of the child into the mode of schooling, i.e. adaptation to a new class and to a new social role.

How to help a child adapt to a new class and a new social role?

The tone of the child's learning and communication at school is probably set by the teacher, but the shades of interaction in a particular class depend on all participants in the training: students and teachers, parents and school administration. Therefore, tune in “to the positive” yourself and set up the child:

- The child feels the mood of an adult, be ready to let the child go into the "new waters". Avoid the school bullying method (“Are you making mistakes again!? At school you will get an F for this”), form a positive attitude towards the school and emphasize its significance for all family members.

- Tell your child what school is for. It is necessary that the school attract the child with its main activity - teaching (“I will learn to read”, “I want to study in order to be like a mother”). Explain that at school the child has his own rights and obligations, that there is a certain structure of communication with the teacher (tell us about your school childhood, show school photos, tell in detail about the rules of conduct).

- Remember yourself that the family will gradually fade into the background, but still play a significant role in the life of the child. And one of the tasks of parents is to be reliable, consistent, to be “good enough” to provide support and help the child to realize himself.

- Get to know the school, the teacher, the class in advance.

- Choose with your child his future school supplies (uniform, backpack, pens, paints, notebooks, etc.): this will support his desire to complete educational tasks. Gather the whole family for a festive dinner, go to the cinema, etc.

: show the child and yourself that a new, exciting, but significant stage in the life of the child, his growing up, has begun.

: show the child and yourself that a new, exciting, but significant stage in the life of the child, his growing up, has begun.

The period of adaptation of the child is not particularly difficult if you understand what is happening with the child at this stage.

Usually, by the age of 6-7, the child is physiologically, emotionally, mentally, etc., ready to change the type of activity: from playing to learning. Moreover, he looks forward to a new learning experience: children are ready to “step over the fence”, into the unknown, they are drawn to the new. On the other hand, this new is sometimes frightening, so the child must feel that he will be able to return back to the familiar world in order to gain strength, relax and go “outside the fence” again. The desire for such a return is usually manifested in past and forgotten forms of behavior (distorting speech, whims, a finger in the mouth, turning to forgotten toys, etc.). Feeling your support, the child will be ready to explore new horizons.

An important acquisition of the child, approximately from the age of 6, will be a sense of "skill" (or, in the case of a negative passage of the stage, a sense of "inferiority"): the child's interest in how things are arranged, how they can be used and adapted. If adults give the child the opportunity to make, build, study, help to bring the matter to the end, cooperate with him, praise him for the result, then the child develops “skill” and a creative attitude towards the world, diligence develops, a feeling arises: “I like to act and achieve results, it gives me the recognition of others. The child begins to form his self-esteem, based on real achievements, in the future this will form his idea of himself as a competent, capable person.

It is very important for a child to know how parents evaluate him and what they expect from him. All the nuances, shades that the child feels in relation to his parents are extremely important for him. From them, the child develops a sense of faith, empathy and love of parents.

Let's imagine a situation: a schoolchild shows his parents a class work with a mark of "5". The reaction of parents may be different, for example:

- “Did anyone help you with this work? Have you copied from someone?

- "I told you (a) - you can whenever you want."

- "I am pleased with you (satisfied)."

- "Well done. I'm happy for you".

As a rule, parents do not think about the emotional meaning of these remarks, and for a child they can carry a different emotional burden. These phrases for a child can mean the following:

- "I don't believe you did it yourself."

- "I know you're lazy."

- “I am satisfied (happy) with you only when you get fives. You are learning for me."

- "I share your joy with pleasure."

Teach your child to evaluate the result of their activities (but do not evaluate the personality of your child). Compare: “you went beyond the outline of the drawing” and “you are always so sloppy when you learn to be attentive!”. Do not demand from the child to be an excellent student, but support the child's self-confidence: give him the opportunity to correct a mistake, remember that a mistake is a natural, normal and inevitable phenomenon.

Do not demand from the child to be an excellent student, but support the child's self-confidence: give him the opportunity to correct a mistake, remember that a mistake is a natural, normal and inevitable phenomenon.

It is quite difficult to predict what will happen at school, but you can prepare yourself and your child. Most often, the following difficulties are distinguished during adaptation:

- “Difficulties of the regime” consist in the inability to complete certain training moments at a strictly defined time, as well as the need not only to do something, but to pay attention to the quality of work. Often, tension occurs due to the fact that someone then in the learning process you need to be slower, and someone faster. If you know what to expect from your child, then talk to a teacher who knows all these patterns well and who is ready to “let go of the leash” and help your child. It is possible that he will give you a series of exercises or help with advice: for example, do tasks with the child (but not instead of him), tell a fairy tale or story (the so-called game form of learning), or help you find information about ways to develop memory, attention .

For a successful entry into the school regime, the physical health of the child is also important - this is the reserve of strength that largely determines the success of both the first year of study and the entire school period of life. Develop your child's motor skills through exercise and walking.

For a successful entry into the school regime, the physical health of the child is also important - this is the reserve of strength that largely determines the success of both the first year of study and the entire school period of life. Develop your child's motor skills through exercise and walking. - "Communicative difficulties" - unwillingness to make contact with others or inability to organize communication, as well as difficulties arising in relationships with the teacher. Try to understand what is happening, what caused this behavior and find a solution that satisfies all parties. Talk to the teacher and find the cause of the difficulties: your child may lack attention (and then you can ask him to include him in some class activities or give simple assignments in which he feels his importance) or the child may be lonely due to the fact that it is difficult for him to get acquainted (and then you can play the game “Let's get acquainted” with him, etc.). Try not to express any dissatisfaction with the child until you establish contact with him, especially at the time of his return from school.

Be creative, be kind, be flexible.

Be creative, be kind, be flexible. - Personal safety issues (eg injuries during recess). As a rule, the school administration gives parents recommendations for the prevention of such situations at school meetings. At home, convey these safety rules to your child: for example, that if everyone rides from the railing, then it is not necessary to repeat this, but you can run in the gym.

School age is the period when a child needs support and understanding from his parents, empathy for his joys and sorrows. The main task of parents in this period is to help the child to accept a new social role - the role of a student.

In conclusion, we note that parents intuitively understand all of the above and act as they should, and when parents ask questions, they often need not advice on how to act and what to do, but an understanding of what is happening.

You have the right to expect your child to show insecurity, anxiety, fear. Trust that he can do it, and know that from time to time he will want and need to return from the outside world to his own enclosure: the familiar environment, your presence, love, support and acceptance - which the family ultimately provides.