Where did jack and the beanstalk originate

Jack and the Beanstalk Origins – Fairy Tale Central

“Jack be nimble, Jack be quick, Jack jump over the—”

Oh wait—wrong Jack.

Or is it?

“Jack and the Beanstalk” is considered one of many “Jack” tales: stories told about the same trickster-like archetype. According to The Center For Children’s Books, the character “is lucky, both a trickster and an unlikely hero, sometimes clever, often naïve, but always successful.” Considered a staple of Cornish and English folklore, other “Jack” tales include “Jack the Giant Killer,” “Little Jack Horner,” and even “Jack Frost.” (Are they the same person? Well that would make for some interesting retellings!)

While “Jack and the Beanstalk” has a long oral history, the first written version comes from a 1734 publication,

Round About our Coal Fire, or “Christmas Entertainments,” where the story is titled “The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean.” Yes, Jack has a last name–at least in this version! And if you’re wondering, the giant’s name is “Gogmagog” (a figure who is, by the way, not relegated solely to Jack’s story; rather, he’s a legendary giant in Welsh folklore). Occasionally, another legendary giant, “Blunderbore,” (who makes an appearance in “Jack the Giant Killer”) stands in as an antagonist in other versions of the tale.

Surprisingly, we don’t see many other written versions of “Jack and the Beanstalk” until 1807. However, the most popular version that most of us are familiar with was published in 1890 in Joseph Jacobs’s English Fairy Tales. Jacobs’s story is based on the oral versions of the story he heard as a child, and as such some scholars believe his version to be the most accurate of the versions published in the nineteenth century (as opposed to, say, the highly moralistic 1807 version from Benjamin Tabart).

But “Jack and the Beanstalk’s” history goes far, far beyond the written word–it has been told orally for hundreds of years! And its origins may reach back even farther than you’d likely expect. According to a recent article from the BBC, researchers at Durham University have classified “Jack and the Beanstalk” as a “Boy Who Stole Ogre’s Treasure” tale, a classification which has origins that could be “traced back to when Eastern and Western Indo-European languages split more than 5,000 years ago. ” Some of these researchers surmise that these tales not only predate languages such as Italian, German, and French, but also Classical mythology!

” Some of these researchers surmise that these tales not only predate languages such as Italian, German, and French, but also Classical mythology!

Evidently, we humans have always relished stories about unlikely heroes!

Sources & further reading:

The Folklore Tradition of the Jack Tales: https://web.archive.org/web/20140410004237/http://ccb.lis.illinois.edu/Projects/storytelling/jsthomps/tales.htm

E-copy of “Christmas Entertainments”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Round_about_our_Coal_Fire,_or,_Christmas_Entertainments,_4th_edn,_1734.pdf

BBC News Article: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-35358487

SurlaLune’s history of “Jack and the Beanstalk:” http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/jackbeanstalk/history.html

The beanstalk's roots – The Irish Times

`FE fo fi fum/ I smell the blood of an Englishman/ Be he living or be he dead/ I'll grind his bones to be my bread." That's what giants say, of course, and have done for centuries, in stories, nursery rhymes, children's games - and especially in Jack and the Beanstalk. Although the rhyme is much older than the fairytale, and is even quoted by Edgar in King Lear, it has crept into versions of Jack and the Beanstalk over the past 150 years, and no pantomime adaptation would be the same without it - accompanied by monstrous, thudding footsteps.

Although the rhyme is much older than the fairytale, and is even quoted by Edgar in King Lear, it has crept into versions of Jack and the Beanstalk over the past 150 years, and no pantomime adaptation would be the same without it - accompanied by monstrous, thudding footsteps.

The earliest printed version of Jack and the Beanstalk was published in England in the 1730s as The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, in a satirical collection of folktales. It is one of the best known of a cycle of Jack stories, including Jack the Giant Slayer; versions of it circulated widely in "chapbooks", the popular English publications printed on a single, folded sheet of paper, illustrated by crude woodcuts and sold for a few pence by pedlars or "chapmen". In 1804 Benjamin Tabart published a Collection of Popular Stories for the Nursery, which included The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk, set "in the days of King Alfred". This was widely sold in his children's bookshop in Soho by the radical political philosopher, William Godwin, who perhaps detected regicidal impulses in the story. A few years later, the tale appeared in verse form as A History Of Mother Twaddle and the Marvellous Atchievements of her son Jack, which differs from Tabart's version in a number of respects.

A few years later, the tale appeared in verse form as A History Of Mother Twaddle and the Marvellous Atchievements of her son Jack, which differs from Tabart's version in a number of respects.

In some versions, Jack is an almost chivalric figure, overcoming adversity, slaying giants and surviving trials like any medieval knight; in others he is a cunning trickster figure (a type recognisable from folktales all over the world, especially Africa) who outwits the giant. In the Jack the Giant Killer series of tales, set in Cornwall, the ogres are particularly obtuse and the heroic dragon-slayer figure of myth and epic - Perseus, Heracles, Theseus, St George and Beowolf - has become a comical adventurer with a taste for violence. Jack digs a huge pit for the giant to fall into and then hacks him to death with an pick-axe. In another version, Jack wraps his stomach with cloths to make a huge pouch, which he fills with offal and then slits open, persuading the giant, Blunderbore, that this is a way of enjoying his dinner twice. When the giant slits his own stomach in imitation, "out dropt his Tripes and Trollybubs".

When the giant slits his own stomach in imitation, "out dropt his Tripes and Trollybubs".

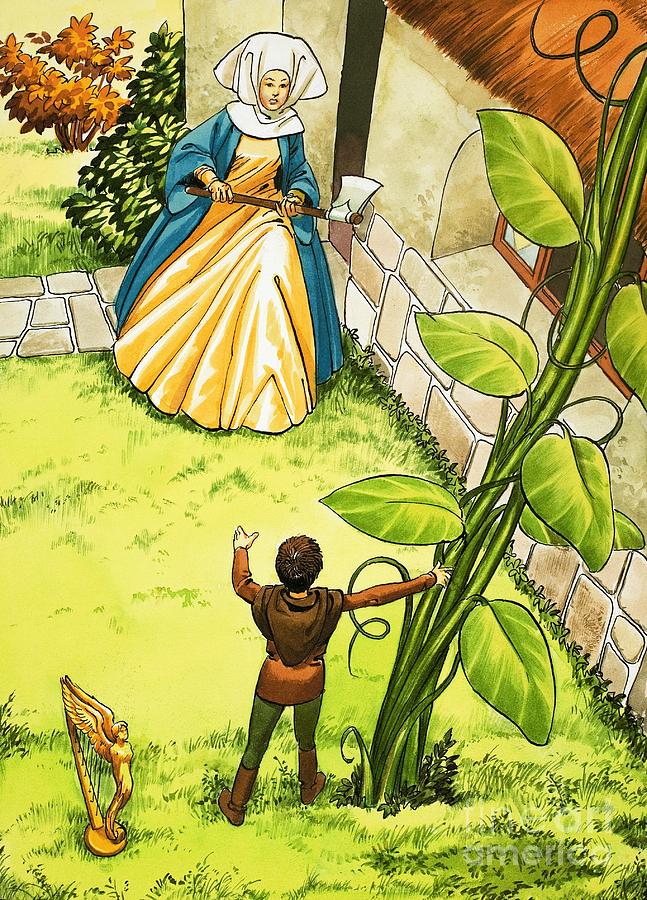

In the version of Jack and the Beanstalk current today, based largely on Joseph Jacobs's English Fairytales (1890), Jack is a simpleton, constantly belittled by his sharp-tongued mother for being a lazy good-for-nothing. He is sufficiently gullible to part with his mother's cow, Milky White, in exchange for a handful of beans from a butcher. In another variant, Jack and his Bargains, Jack is in conflict with his father, not his mother, and he swaps the cow for a magic stick rather than beans. The stick beats his father to a pulp ("up stick and at it") and Jack is established as head of the household.

READ MORE

In The History of Mother Twaddle, Jack is sold the beans by a strange, dwarf-like man with a huge head and magic powers. In her most recent book, No Go the Bogeyman, Marina Warner links this man and the magic beans to the secret, pre-Christian Pythagorean cult. All versions agree that when Jack returns to his anxious mother, she throws the beans out of the window in disgust and when she and Jack wake up the next day, they find that the beans have taken root: "The stalks were of an immense thickness, and had so entwined that they formed a ladder nearly like a chain in appearance."

All versions agree that when Jack returns to his anxious mother, she throws the beans out of the window in disgust and when she and Jack wake up the next day, they find that the beans have taken root: "The stalks were of an immense thickness, and had so entwined that they formed a ladder nearly like a chain in appearance."

A ladder reaching to the heavens is a beautifully resonant image which brings to mind Jacob's ladder in the Old Testament; the iconography of medieval paintings in which the celestial realm is depicted as an upper storey of a building; and the Norse cycle of cosmological tales, the Edda, in which the world tree, Yggdrassil, stretches up to Heaven, while its roots reach down to Hell. The ascent to the upper world by means of a tree is one of the many universal folktale motifs in Jack and the Beanstalk which ensure its enduring appeal and announce that we have entered a realm of enchantment and wonder: the seemingly foolish bargain which provides something enchanted, the quest-journey of the hero towards independence, the concealment of the hero by the giant's wife, the series of three thefts - of the goose that lays golden eggs, of the sack filled with gold and the harp - the magical speaking object. The psychoanalyst, Bruno Bettelheim, who wrote extensively about the symbolic function of fairytales as psychological paradigms, reads Jack and the Beanstalk as a depiction of the struggle to reach social and sexual maturity - specifically, to assert adult masculine sexuality. He emphasises the obvious phallic symbolism of the beanstalk growing in the night, and links this to childish anxiety about masturbation. In this somewhat reductive interpretation, all is safely resolved within the confines of the story: "In cutting down the beanstalk, Jack . . . relinquishes his belief in the magic power of the phallus as the means for gaining him all the good things in life. As the story ends, Jack is ready to give up phallic and oedipal fantasies and instead try to live in reality." Happy ever after, of sorts.

The psychoanalyst, Bruno Bettelheim, who wrote extensively about the symbolic function of fairytales as psychological paradigms, reads Jack and the Beanstalk as a depiction of the struggle to reach social and sexual maturity - specifically, to assert adult masculine sexuality. He emphasises the obvious phallic symbolism of the beanstalk growing in the night, and links this to childish anxiety about masturbation. In this somewhat reductive interpretation, all is safely resolved within the confines of the story: "In cutting down the beanstalk, Jack . . . relinquishes his belief in the magic power of the phallus as the means for gaining him all the good things in life. As the story ends, Jack is ready to give up phallic and oedipal fantasies and instead try to live in reality." Happy ever after, of sorts.

Late 19th-century versions attempted to sanitise the story to ensure the moral protection of children by introducing the character of a fairy who meets Jack in the upper world and tells him that the giant had killed Jack's father long ago: desire for retribution then becomes Jack's justification for stealing from the giant. But this is unnecessary: Jack steals from the giant because he is physically overpowering and could kill him; in the tradition of giant slaying and outwitting, he wants to get his retaliation in first.

But this is unnecessary: Jack steals from the giant because he is physically overpowering and could kill him; in the tradition of giant slaying and outwitting, he wants to get his retaliation in first.

Whether the impulse is to depose authority figures, to kill or emasculate fathers, to overthrow tyranny, or to simply to keep evil forces at bay, giant-killing in myth, legend and folktale has a timeless appeal, offering great psychological and emotional satisfactions. The attempt to disempower grotesque, terrifying ogres is a venerable one. Brute force and gigantic scale are repeatedly defeated by moral superiority or low cunning in mythical traditions extending in the West as far back as Hesiod's Theogony (8th century B.C.) in which Zeus overpowers a monster with 100 snake-heads, Typhoeus, in his battle for supremacy over the gods, while in Homer's Odyssey, dating from roughly the same period, Odysseus and his men escape from the cyclops, Polyphemus, by blinding him and disguising themselves among his sheep.

We may no longer live in remote villages enveloped in darkness for months and beset by unnamable terrors, but fear is still part of our experience - as adults as well as children - and stories help us to express and allay it. But what is frightening in one culture and period does not necessarily retain its power over succeeding generations. The form inevitably changes, and we can easily become too precious and reverential about the "classic" fairytales, forgetting that even the beloved canon of Grimm and Perrault stories began as anarchic oral folktales, which were constantly adapted and modified in transmission.

Contemporary children's books about giants such as Roald Dahl's Big Friendly Giant and Raymond Brigg's Jim and the Beanstalk take a gleefully comic approach to the old themes. Even the illustrations of Jack and the Beanstalk now tend to be benign, almost cuddly; in children's literature the grotesque is domesticated and real fear has migrated to spectacular screen images, generated by special effects. The pantomime form, too, makes us laugh at what we fear: since the first stage adaptation in 1819 (Harlequin and the Ogre), the resilient pantomime tradition of Jack and the Beanstalk has portrayed the giant as a burlesque figure rather than a threatening, cannibalistic ogre. "Fe fi fo fum"? What's that?

The pantomime form, too, makes us laugh at what we fear: since the first stage adaptation in 1819 (Harlequin and the Ogre), the resilient pantomime tradition of Jack and the Beanstalk has portrayed the giant as a burlesque figure rather than a threatening, cannibalistic ogre. "Fe fi fo fum"? What's that?

Jack and the Beanstalk is at the Gaiety at varying times daily: 1.30 p.m., 3 p.m., 6.30 p.m., 8 p.m. Booking from: 01-677 1717.

90,000 Jack and the Beanstalk is an English fairy tale. The story of the boy Jack.A tale about a poor widow's son, Jack, who traded his family's only breadwinner, a cow, for magic beans. With the help of them and their ingenuity, Jack and his mother got rich.

Once upon a time there lived a poor widow. She had an only son named Jack and a cow named Belyanka. The cow gave milk every morning, and the mother and son sold it in the bazaar - this is how they lived. But suddenly Belyanka stopped milking, and they simply did not know what to do.

— How can we be? What to do? the mother repeated in despair.

— Cheer up, mother! Jack said. - I'll get someone to work with.

— Yes, you already tried to get hired, but no one hires you, — answered the mother. “No, apparently, we will have to sell our Belyanka and open a shop with this money.

“Well, okay, Mom,” Jack agreed. - Today is just a market day, and I will quickly sell Belyanka. And then we'll decide what to do.

And Jack took the cow to the market. But he did not have time to go far when he met a funny, funny old man, and he said to him:0003

- Good morning, Jack!

— Good morning to you too! - Jack answered, and was surprised to himself: how does the old man know his name.

— Well, Jack, where are you going? asked the old man.

- To the market, to sell a cow.

— Yes, yes! Who should trade cows if not you! the old man laughed. “Tell me, how many beans do I have?”

- Exactly two in each hand and one in your mouth! - answered Jack, apparently, not a small mistake.

- That's right! said the old man. “Look, here are those beans!” And the old man showed Jack some strange beans. “Since you’re so smart,” the old man continued, “I’m not averse to trading with you—I’m giving these beans for your cow!”

— Go on your way! Jack got angry. “That would be better!”

"Uh, you don't know what beans are," said the old man. “Plant them in the evening, and by morning they will grow to the sky.

— Yes, well? Truth? Jack was surprised.

- The real truth! And if not, take your cow back.

- Coming! - Jack agreed, gave the old man Belyanka, and put the beans in his pocket.

Jack turned back home, and since he did not have time to go far from home, it was not dark yet, and he was already at his door.

- Are you back yet, Jack? mother was surprised. - I see Belyanka is not with you, so you sold her? How much did they give you for it?

— You'll never guess, Mom! Jack answered.

— Yes, well? Oh my good! Five pounds? Ten? Fifteen? Well, twenty something will not give!

- I said - you can't guess! What can you say about these beans? They are magical. Plant them in the evening and...

Plant them in the evening and...

— What?! cried Jack's mother. “Are you really such a simpleton that you gave my Belyanka, the most milking cow in the whole area, for a handful of some bad beans?” It is for you! It is for you! It is for you! And your precious beans will fly out the window. So that! Now live to sleep! And don’t ask for food, you won’t get it anyway - not a piece, not a sip!

And then Jack went up to his attic, to his little room, sad, very sad: he angered his mother, and he himself was left without supper. Finally, he did fall asleep.

And when he woke up, the room seemed very strange to him. The sun illuminated only one corner, and everything around remained dark, dark. Jack jumped out of bed, dressed and went to the window. And what did he see? What a strange tree! And these are his beans, which his mother threw out of the window into the garden the day before, sprouted and turned into a huge bean tree. It stretched all the way up, up and up to the sky. It turns out that the old man was telling the truth!

It turns out that the old man was telling the truth!

The beanstalk grew just outside Jack's window and went up like a real staircase. So Jack had only to open the window and jump onto the tree. And so he did. Jack climbed the beanstalk and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he finally reached the sky. There he saw a long and wide road, as straight as an arrow. I went along this road and kept walking and walking and walking until I came to a huge, huge tall house. And at the threshold of this house stood a huge, enormous, tall woman.

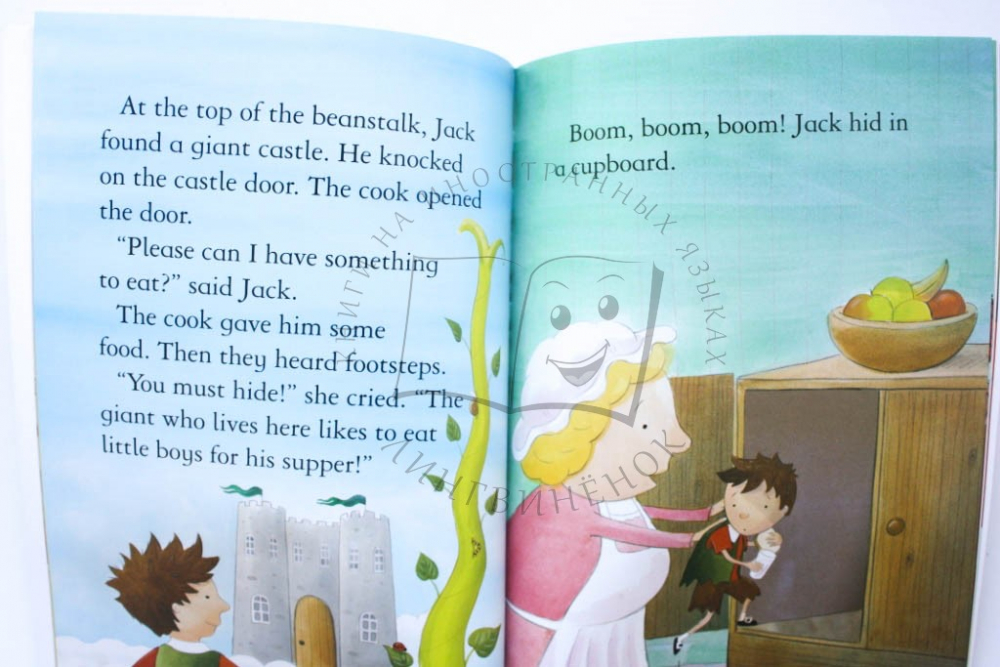

— Good morning, ma'am! Jack said very politely. “Be so kind as to give me breakfast, please!”

After all, the day before Jack had been left without supper, you know, and now he was as hungry as a wolf.

— Would you like to have breakfast? - said a huge, enormous, tall woman. “You yourself will get another for breakfast if you don’t get out of here!” My husband is a giant and a cannibal, and he loves nothing more than boys fried in breadcrumbs.

— Oh, madame, I beg you, give me something to eat! Jack didn't hesitate. “I haven’t had a crumb in my mouth since yesterday morning. And it doesn't matter if they fry me or I'll die of hunger.

Well, the ogre's wife was not a bad woman after all. So she took Jack to the kitchen and gave him a piece of bread and cheese and a jug of fresh milk. But before Jack had time to finish with half of all this, when suddenly - top! Top! Top! - the whole house even shook from someone's steps.

- Oh my God! Yes, that's my old man! gasped the giantess. - What to do? Hurry, hurry, jump over here!

And just as she pushed Jack into the oven, the ogre himself entered the house.

Well, he was really great! Three calves dangled from his belt. He untied them, threw them on the table and said:

— Come on, wife, fry me a couple for breakfast! Wow! What does it smell like?

Fi-fi-fo-foot,

I smell the spirit of the British here.

Whether he is dead or alive,

Will go to my breakfast.

— What are you, hubby! his wife told him. - You've got it. Or maybe it smells like that lamb that you liked so much yesterday at dinner. Come on, wash your face and change, and in the meantime I will prepare breakfast.

The ogre came out and Jack was about to get out of the oven and run away, but the woman wouldn't let him.

“Wait until he falls asleep,” she said. He always likes to take a nap after breakfast.

And so the giant had breakfast, then went to a huge chest, took out two sacks of gold from it and sat down to count the coins. He counted and counted, finally began to nod off and began to snore so that the whole house began to shake again.

Then Jack slowly got out of the oven, tiptoed past the sleeping ogre, grabbed one bag of gold and God bless! — straight to the beanstalk. He dropped the bag down into his garden, and he began to descend the stem, lower and lower, until at last he found himself at home.

Jack told his mother about everything, showed her a bag of gold and said:

— Well, Mom, did I tell the truth about these beans? You see, they are really magical!

“I don’t know what these beans are,” answered the mother, “but as for the cannibal, I think it’s the one who killed your father and ruined us!”

And I must tell you that when Jack was only three months old, a terrible ogre appeared in their area. He grabbed anyone, but especially did not spare the kind and generous people. And Jack's father, although he was not rich himself, always helped the poor and the losers.

He grabbed anyone, but especially did not spare the kind and generous people. And Jack's father, although he was not rich himself, always helped the poor and the losers.

“Oh, Jack,” the mother finished, “to think that the cannibal could eat you too!” Don't you dare climb that stem ever again!

Jack promised, and they lived with their mother in full contentment with the money that was in the bag.

But in the end the bag was empty, and Jack, forgetting his promise, decided to try his luck at the top of the beanstalk one more time. One fine morning he got up early and climbed the beanstalk. He climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, until he finally found himself on a familiar road and reached along it to a huge, enormous tall house. Like last time, a huge, enormous, tall woman was standing at the threshold.

“Good morning, ma'am,” Jack told her as if nothing had happened. “Be so kind as to give me something to eat, please!”

- Get out of here, little boy! the giantess replied. “Or my husband will eat you at breakfast.” Uh, no, wait a minute, aren't you the youngster who came here recently? You know, on that very day my husband missed one sack of gold.

“Or my husband will eat you at breakfast.” Uh, no, wait a minute, aren't you the youngster who came here recently? You know, on that very day my husband missed one sack of gold.

— These are miracles, ma'am! Jack says. “It’s true, I could tell you something about it, but I’m so hungry that until I eat at least a piece, I won’t be able to utter a word.

The giantess was so curious that she let Jack into the house and gave him something to eat. And Jack deliberately began to chew slowly, slowly. But suddenly - top! Top! Top! they heard the steps of the giant, and the kind woman again hid Jack in the furnace.

Everything happened just like last time. The ogre came in and said: “Fi-fi-fo-foot…” and so on, had breakfast with three roasted bulls, and then ordered his wife:

- Wife, bring me a chicken - the one that lays the golden eggs!

The giantess brought it, and he said to the hen: “Come on!” And the hen laid a golden egg. Then the cannibal began to nod and began to snore so that the whole house shook.

Then Jack slowly got out of the oven, grabbed the golden hen and was out the door in no time. But then the hen cackled and woke up the ogre. And just as Jack was running out of the house, he heard the giant's voice behind him:

— Wife, leave the golden hen alone! And the wife answered:

- Why are you, my dear!

That's all Jack could hear. He rushed with all his might to the beanstalk and almost flew down it.

Jack returned home, showed his mother the miracle chicken and shouted: "Go!" And the hen laid a golden egg.

Since then, every time Jack told her, "Rush!" The hen laid a golden egg.

Mother scolded Jack for disobeying her and going to the cannibal again, but she still liked the chicken.

And Jack, a restless guy, after a while decided to try his luck again at the top of the beanstalk. One fine morning he got up early and climbed the beanstalk.

He climbed and climbed and climbed and climbed until he reached the very top. True, this time he acted more carefully and did not go straight to the cannibal's house, but crept up slowly and hid in the bushes. I waited until the giantess came out with a bucket for water, and darted into the house! I climbed into the copper cauldron and waited. He didn’t wait long, suddenly he hears the familiar “top! Top! Top!", and now the ogre and his wife enter the room.

True, this time he acted more carefully and did not go straight to the cannibal's house, but crept up slowly and hid in the bushes. I waited until the giantess came out with a bucket for water, and darted into the house! I climbed into the copper cauldron and waited. He didn’t wait long, suddenly he hears the familiar “top! Top! Top!", and now the ogre and his wife enter the room.

- Fi-fi-fo-foot, I smell the spirit of the British here! shouted the cannibal. “I can smell it, wife!”

— Can you really hear it, hubby? says the giantess. “Well, then, this is the tomboy who stole your gold and the goose with golden eggs. He's probably in the oven.

And both rushed to the stove. Good thing Jack wasn't hiding there!

- Always you with your fi-fi-fo-foot! grumbled the ogre's wife, and began preparing breakfast for her husband.

The ogre sat down at the table, but still could not calm down and kept mumbling:

— Still, I can swear that… — He jumped up from the table, rummaged through the pantry, and chests, and sideboards…

He searched all the corners, only he didn’t guess to look into the copper cauldron. Finally finished breakfast and shouted:

Finally finished breakfast and shouted:

- Hey, wife, bring me a golden harp! The wife brought the harp and put it on the table.

- Sing! the giant ordered the harp.

And the golden harp sang so well that you will hear it! And she sang and sang until the ogre fell asleep and snored like thunder.

It was then that Jack lightly lifted the lid of the cauldron. He got out of it quietly, quietly, like a mouse, and crawled on all fours to the very table. He climbed onto the table, grabbed the harp, and rushed to the door.

But the harp called loudly:

— Master! Master!

The ogre woke up and immediately saw Jack running away with his harp.

Jack ran headlong, and the giant followed him. It cost him nothing to catch Jack, but Jack was the first to run, and therefore he managed to dodge the giant. And besides, he knew the road well. When he reached the bean tree, the ogre was only twenty paces away. And suddenly Jack was gone. Cannibal here, there - no Jack! Finally, he thought to look at the beanstalk and sees: Jack is trying with his last strength, crawling down. The giant was afraid to go down the shaky stalk, but then the harp called again:0003

The giant was afraid to go down the shaky stalk, but then the harp called again:0003

- Master! Master!

And the giant just hung on the beanstalk, and the beanstalk trembled all under its weight.

Jack descends lower and lower, and the giant follows him. But now Jack is right above the house. Then he screams:

- Mom! Mother! Bring the ax! Bring the ax!

Mother ran out with an ax in her hands, rushed to the beanstalk, and froze in horror: huge legs of a giant stuck out of the clouds.

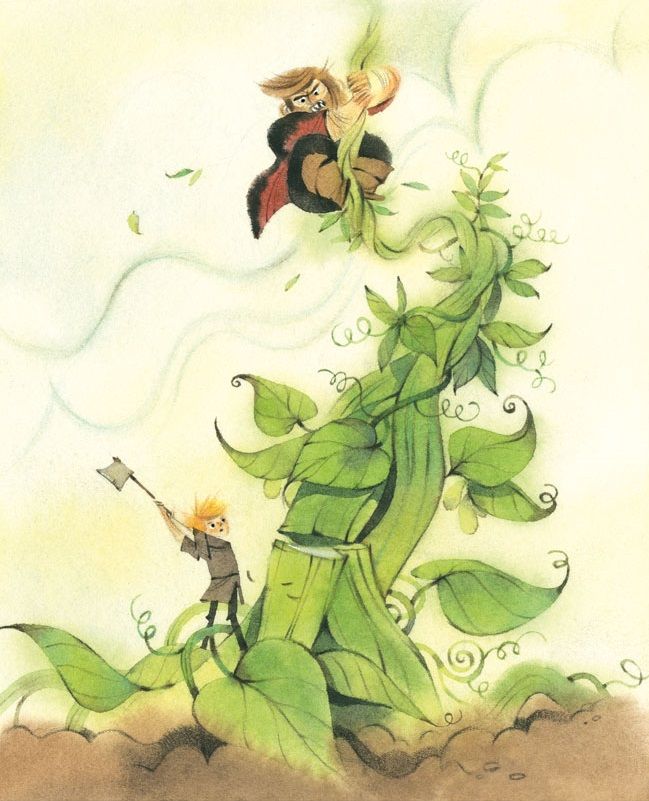

But then Jack jumped down to the ground, grabbed an ax and hacked at the beanstalk so hard that he almost cut it in half.

The ogre felt the stalk swaying and shaking and stopped to see what had happened. Here Jack strikes with an ax again and completely cuts the beanstalk. The stalk swayed and collapsed, and the ogre fell to the ground and twisted his neck.

Jack gave his mother a golden harp, and they began to live without grieve. And they did not remember about the giant.

Jack and beans. English Folk Tale - "An English tale of agility and that "fools are lucky""

Since childhood, I liked the fairy tale "Jack and the beanstalks". I had a book with beautiful illustrations, I liked to look at them.

It was so unusual. Beanstalk, stalk growing straight up into the sky, giants and so on.

I re-read it with pleasure, and maybe it even caused me to start eating beans. Not that I loved them, but at least I have always been loyal to them, and this very fairy tale has influenced this.

Jack and the Beanstalk - English Folk Tale

In culture: there are several adaptations of different times and even an anime cartoon. Moreover, the plot is interpreted in different ways. The canonical "Jack beans" and where he is presented as a villain.

Number of pages:

a small fairy tale. About 10 pages. That's why it's a fast read. It takes me about 7 minutes to read, although if you read it aloud, of course, it takes a little longer.

About 10 pages. That's why it's a fast read. It takes me about 7 minutes to read, although if you read it aloud, of course, it takes a little longer.

Where the events take place:

this is a fictional world. Countryside and house, next to the field. Then events will shift to the sky, where Jeev climbed up the beanstalk.

Main characters:

- Jack is the main character of the tale who seems too stupid and naive. But this did not prevent him from showing cunning and deceiving the Giant. That is, to sell the last cattle for 5 grains, he did not realize what was wrong. But I guessed to steal a bag of gold ... I still agree with the interpretation and in my opinion Jack is not as good as it seems and personally I perceive him more as a negative character;

- Jack's mother - Jack's mother is raising a child in poverty. For the fact that he blundered scolds him and leaves him without dinner.

But there is a connection between them and her son, and she unconditionally loves him in her own way. Jack, having become rich, immediately returns to her, and she helps get rid of the beanstalk;

But there is a connection between them and her son, and she unconditionally loves him in her own way. Jack, having become rich, immediately returns to her, and she helps get rid of the beanstalk; - The giant is a formidable inhabitant of the clouds. In addition to being a giant, he is also a cannibal He smells the smell of human flesh. He is engaged in robbery and robbery, robs other people, from this he has untold wealth in his house;

- The giant's wife is also a giantess. But unlike her husband, she is much kinder. She takes Jack into the house and hides him so that the Giant does not find him. Jack deceived her, but she still saved him a second time, and only then, unable to bear such a betrayal on his part, she tried to get rid of him. For which, by the way, I do not blame her.

Plot:

Jack's family lived in poverty and in order to feed themselves a little, Jack's mother sends him to the market to sell cattle.

I've always wondered why poverty flourished in fairy tales. Probably because such tales were passed from mouth to mouth, primarily among the common people. And stories about poor people who tried their luck and became rich always inspired and gave hope for the best.

Jack, going to the market, met a stranger who offered to exchange the cattle for some beans. Well, since our main character was of a small mind, he immediately agreed. In general, suppose how the stranger could know how events would develop. He could not germinate them, well, or he would have simply been eaten by the Ogre. This desire to cash in on the mentally retarded is simply disgusting.

Jack's mother was furious when she heard about this unequal deal. Scolded, rushed at him and even completely left him without dinner.

At the speed of light, magic beans, thrown out of the window by mom, sprouted. And a huge thick stalk rushed straight into the sky. Praise chance and luck)

Je climbed up there and saw a house there. The giantess' wife let him in. And then she showed her kindness and indifference. For the sake of a stranger, she deceived her husband and hid the boy, but in return the boy scammed them all and stole a bag of gold. At this point, I began to like Jack even less..

The giantess' wife let him in. And then she showed her kindness and indifference. For the sake of a stranger, she deceived her husband and hid the boy, but in return the boy scammed them all and stole a bag of gold. At this point, I began to like Jack even less..

He returned home with wealth, they did not grieve, but when the money ran out, he went back to the giant.

Impressions:

It seems to me that the moral of this tale is that the poor will surely achieve prosperity. That if you are persecuted and unhappy, then you will certainly achieve prosperity. In my opinion, this is wrong, because a fairy tale teaches us to hope for good luck. After all, not the mother, not Jack himself, did nothing for his happiness, but on the contrary achieved this by fraudulent means.

But if we consider that Jack is still a villain.

That fairy tale teaches not to trust strangers. because it may be "a wolf in sheep's clothing. " The giantess helped Jack, and for this he deceived her husband, which means he robbed her too.

" The giantess helped Jack, and for this he deceived her husband, which means he robbed her too.

And even the second time, his conscience didn't waver. The thirst for easy pressure and well-being in an easy way turned out to be stronger, and he once again returned to the house of the Giants to steal his belongings. And someone can say, but the Vedas and the Giant robbed. Yes, but Jay was not a Robin Hood, but he stole for himself so as not to work. Stealing from a thief is not an excuse, but the same crime. Hearing this tale, the child may draw the wrong conclusions. For example, what can be deceived for the sake of money. But this is extremely wrong, it would be better if he was taught to earn by honest work.

I don't understand why so many people see Jack as good, while giants are seen as villains. Everything is ambiguous here. And Jack's goodness is puzzling to me.

+ and -:

+ interesting story;

+ plot;

- ambiguous morality.