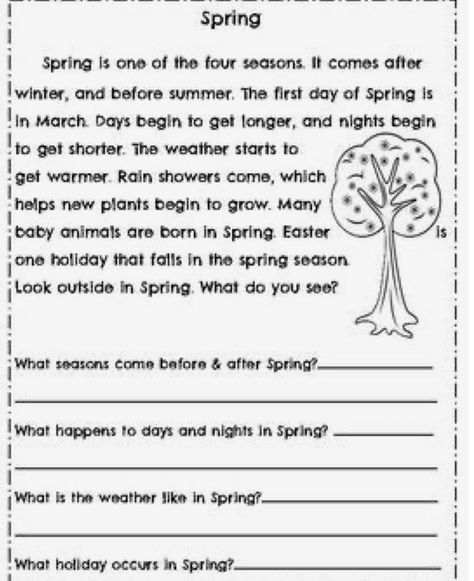

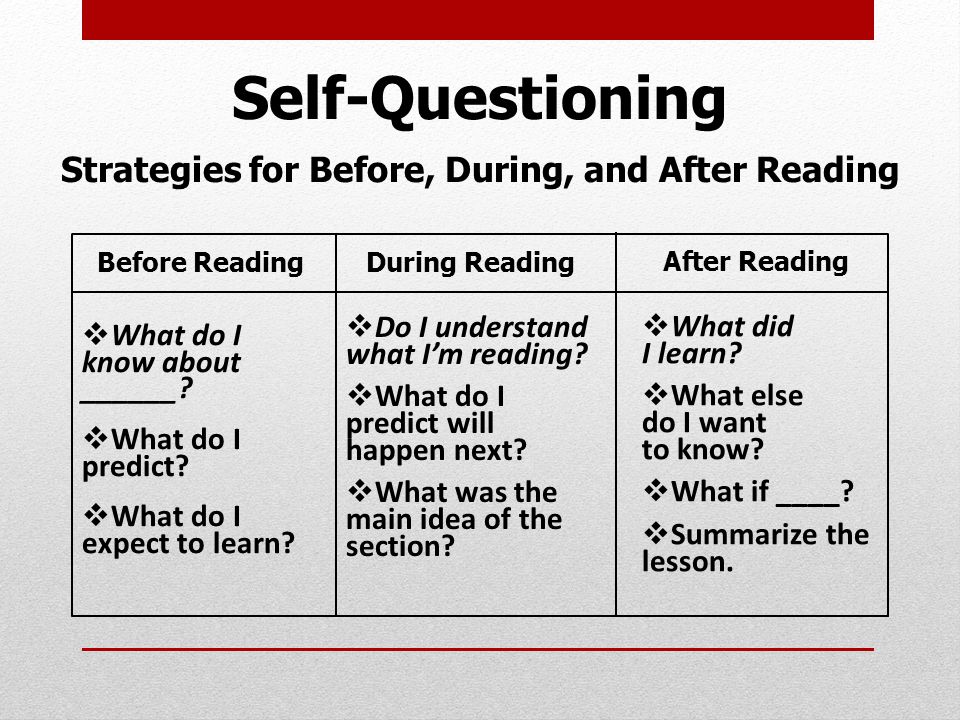

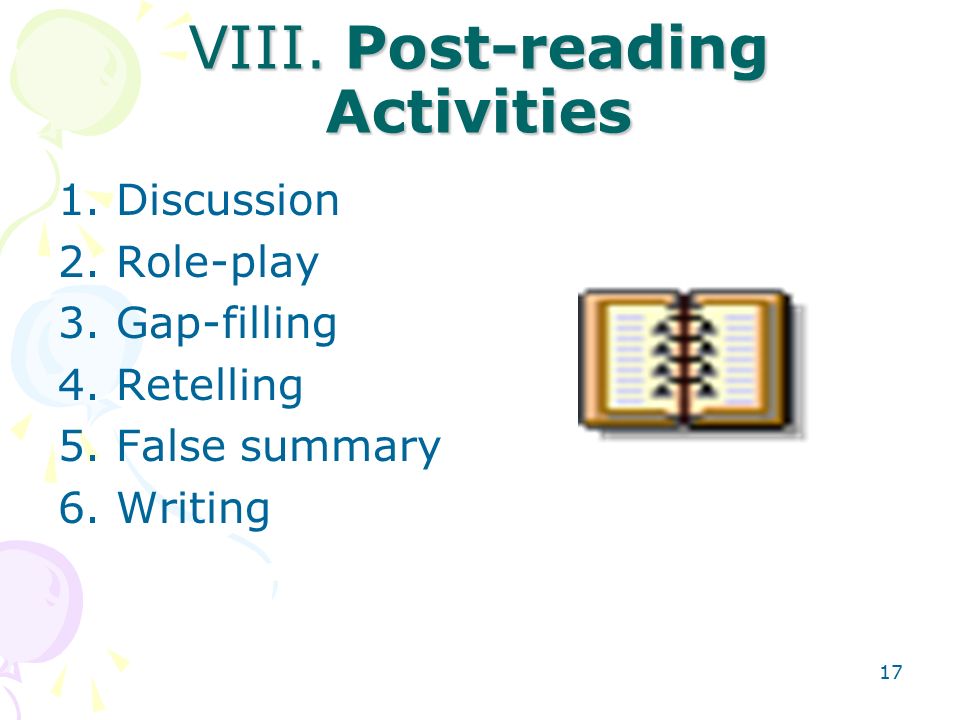

After reading activity

After-Reading Activities | SEA - Supporting English Acquisition

Students often finish a reading, close the book, and don't think about it again until they arrive in class. The following activities can be used after a reading to help students analyze concepts for a deeper understanding of ideas and organize information for later retrieval:

Graphic Organizers

Encourage students to use graphic organizers (charts or concept "maps") to help them visualize concepts and key relationships between ideas from their readings. These should be started right after students have completed a reading, whereas revisions and additions can be done after class discussions.

It's a good idea to show students several examples of graphic organizers and explain which ones work well with different text patterns. Many reading skills texts have examples of various graphic organizers with explanations of how they might best be used. Here is an example of one type of graphic organizer for comparing two concepts:

Quiz Questions

After students read a chapter or section of a chapter in the course textbook, ask them to develop questions for a quiz. (This can also be done with other reading materials.) This activity forces them to analyze the information in the chapter and decide on the most important concepts to remember.

Formulating questions can also help them to organize the concepts into logical chunks of information for easier retrieval. Working in groups on this activity is helpful for further discussion of concepts.

Students can then present their questions to the class and see who can answer them correctly. The students trying to answer the questions may offer suggestions on how to write a question more clearly so that it can be easily understood. Teachers might also offer suggestions for revision of questions. Other SEA Site modules, for example, "WH-Questions" and "Passive Voice" can be useful for teachers in providing guidance in using structures that will be more easily understood by students.

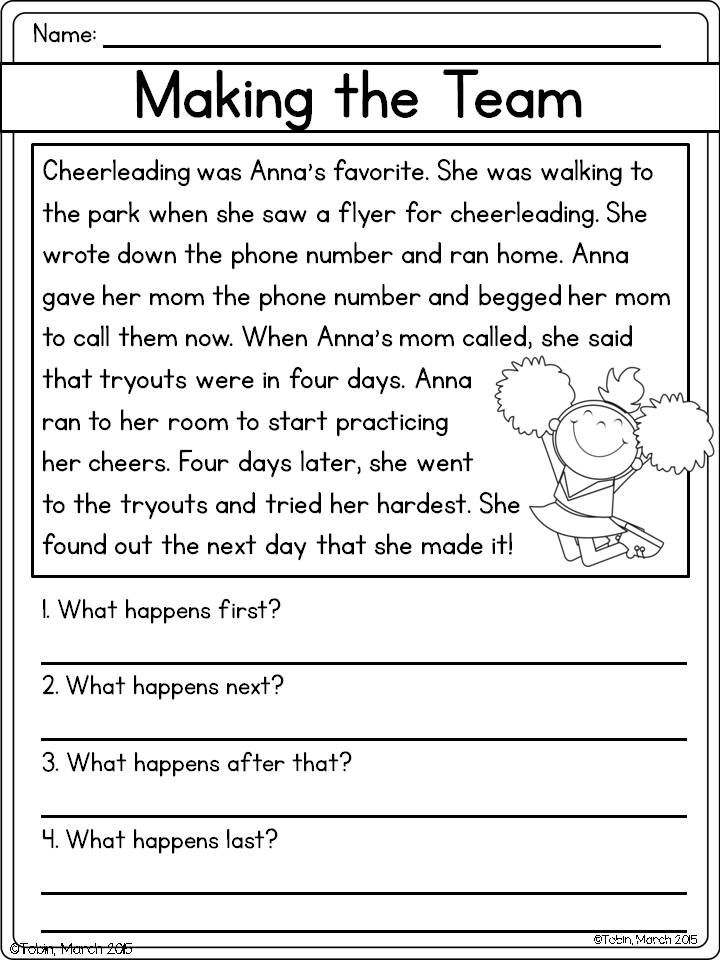

Summary Writing

Ask students to write a summary of the main points of a text or passage. Figuring out what to include in a summary is often a difficult task for students, so passing out a handout with the criteria for a good summary can serve as a reminder to students.

Figuring out what to include in a summary is often a difficult task for students, so passing out a handout with the criteria for a good summary can serve as a reminder to students.

Modeling the process of good summary writing during class is also helpful. For example, when students have finished a portion of text, begin a discussion of the most important points from the text. Write all the points that students suggest on the board. Discuss which ideas should be included in the summary. In addition, show how ideas can be paraphrased and written in the student's own words.

Remember to emphasize that minor details,specific examples, and opinions should not be included in a summary of a text.

Outlining

Writing outlines is also a good way to organize and remember concepts. The emphasis here should be on how students see the relationships between ideas being presented. Don't worry if students don't use the correct Roman numerals or other markers. What is important is that they are able to distinguish the main ideas from the supporting details and organize the information in a logical format.

What is important is that they are able to distinguish the main ideas from the supporting details and organize the information in a logical format.

Creative Testing

To evaluate how much of a text students understood, and to see how confident students are when answering questions about a text, you can try the following quiz method I saw used by a colleague, Vicki Robinson, in a physics class at NTID. This method also encourages valuable small group discussion of concepts. Here's how it works:

Students read an assigned number of pages for homework. (The number of pages assigned usually depends on the level of difficulty of the text.) They are told that they will be quizzed on the information the next day.

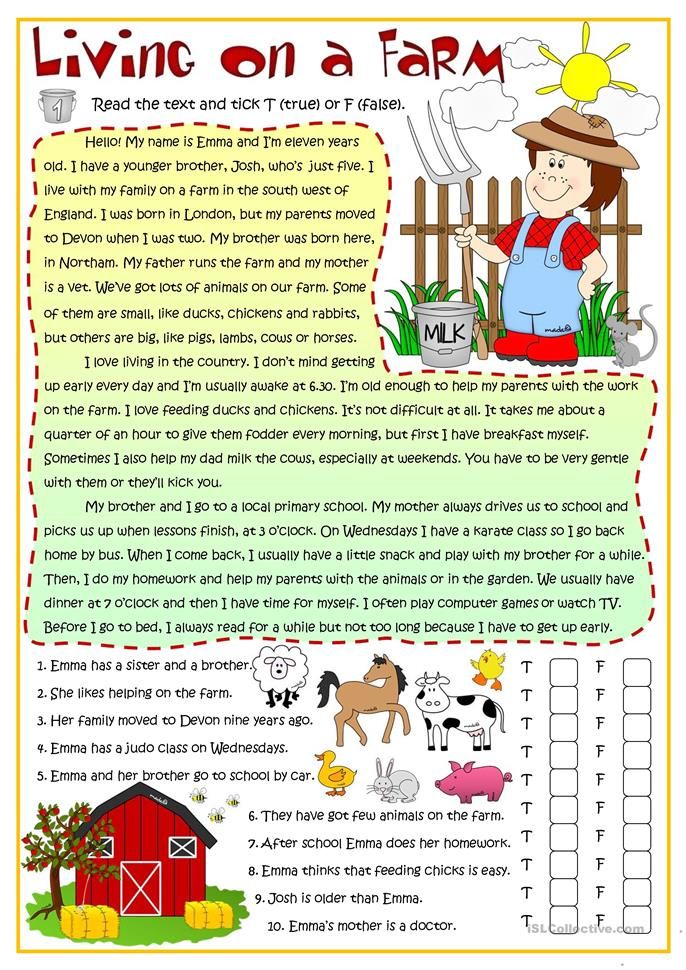

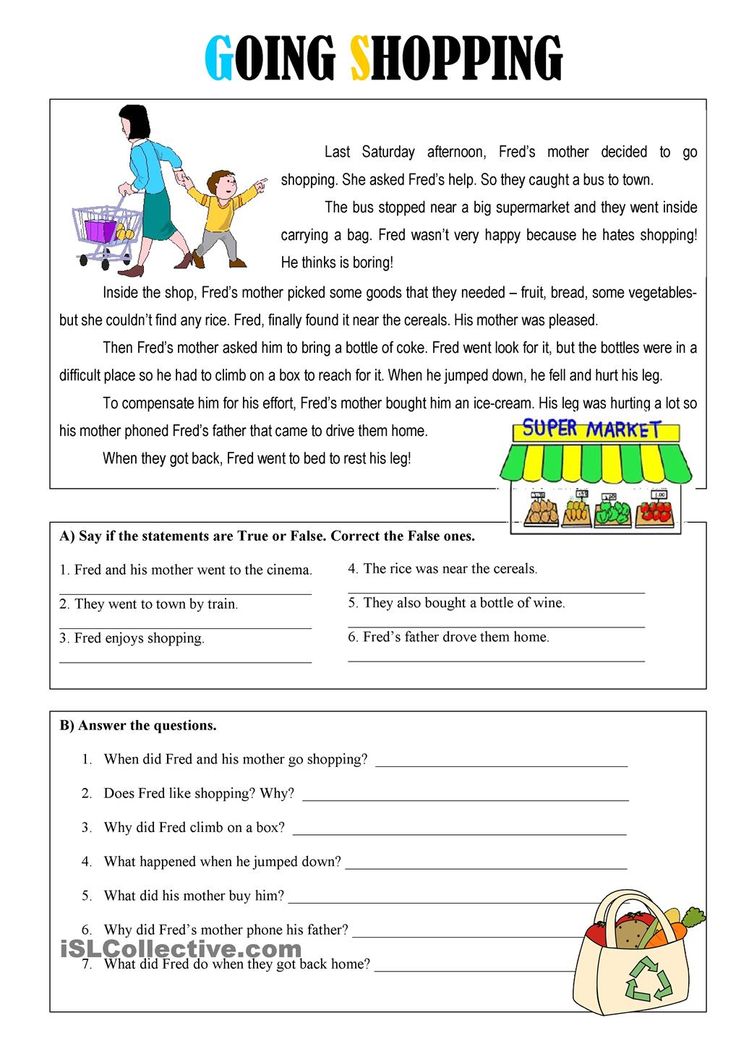

When the students arrive for class the following day, they are each given a quiz and asked to complete it individually. The quiz involves a series of TRUE/FALSE (T/F) questions where the students are required to write three answers for each question.

Here's an example of a quiz question:

Newton's third law of motion is: For every force (action), there is an equal and opposite force (reaction).

If students feel strongly that this statement is true, they would write T, T, T as their three answers to the question. If they are fairly confident that this statement is true, but not totally sure, they could write T, T, F. If they feel strongly that this is an incorrect statement, they could answer F, F, F, and so on. Each question is worth three points, so it is possible to receive partial credit.

After students answer all the questions, their papers are collected by the teacher. Then the students are divided into groups and given the same quiz. Students discuss the questions, give their opinions, and try to support their answers with information they remember from the text. They write their own TRUE and FALSE answers to the questions again based on the discussion with their group.

The teacher collects the papers and has the option of keeping both scores for each student, combining the scores for both quizzes and recording the average, or keeping the higher of the two scores.

103 Things to Do Before, During, or After Reading

- Pantomime

Act out a scene you choose or the class calls out to you while up there.

- Dramatic monologue

Create a monologue for a character in a scene. What are they thinking/feeling at that moment? Why?

- Dramatic monologue

Dive into Reading Rockets' summer initiative, Start with a Book. You'll find theme-related children's books, hands-on activities, and other great resources to encourage reading, exploring, and learning all summer long.

Create a monologue for a character while they are out of the book. Where are they? Why? What are they thinking?

- Business card book

Write the story in the most compelling way you can on paper the size of a business card.

- Postcard

Write to a friend, the author, or to a character about this book. Write as if you were the character or author and write to yourself.

- Mapmaker

Draw a map of the book's setting.

- Moviemaker

Write a one page "pitch" to a producer explaining why the story would or would not make a great movie.

- Trailer

Movie previews always offer a quick sequence of the best moments that make us want to watch it – storyboard or narrate the scenes for your trailer. Focus on verbs.

- Billboard

As in the movies, take what seems the most compelling image(s) and create an ad.

- Adjective-itis

Pick five adjectives for the book or character(s), and explain how they apply.

- Collage

Create an individual or class collage around themes or characters in the book.

- Haiku/Limerick

Create one about a character.

- CliffsNotes

Have each student take a chapter and, using the CliffsNotes format, create their own.

- Roundtable

Give students a chance to talk about what intrigues, bothers, confuses them about the book.

- Silent roundtable

The only rule is the teacher cannot say anything during the period allotted for class discussion of book.

- Silent conversation

A student writes about a story on paper, then passes it to another who responds to what they said. Each subsequent respondent "talks" to/about all those before.

- Fishbowl

Impromptu or scheduled, two to four students sit in middle of circle and talk about a text. The class makes observations about the conversation then rotate into the circle.

- Movie review

Students write a review of (or discuss) a movie based on a story.

- Dear author

After reading a book the student(s) write the author via the publisher (who always forwards them).

- Dig deeper on the Web

Prior to, while, or after reading a book, research the book, its author, or its subject online.

- Inspirations

Watch a film inspired by a story (e.g., Franny and Alexander is inspired by Hamlet) and compare/contrast.

- Timeline

Create a timeline that includes both the events in the novel and historical information of the time.

Try using Post-Its on a whiteboard or butcher paper!

Try using Post-Its on a whiteboard or butcher paper! - Mandala

Create a mandala with many levels to connect different aspects of a book, its historical time, and culture.

- Transparencies

Copy portions of the text to a transparency. Kids annotate with markers and then get up to present their interpretations to the class.

- Gender-bender

Rewrite a scene and change the gender of the characters to show how they might act differently (e.g., Lord of Flies). You can also have a roundtable on gender differences.

- Picture this

Bring in art related to book's time or themes. Compare, describe, and discuss.

- Kids books

Bring in children's books about related themes and read these aloud to class.

- Downgrade

Adapt myths or other stories for a younger audience. Make into children's books or dramatic adaptation on video or live.

- Draw!

Translate chapters into storyboards and cartoons; draw the most important scene in the chapter and explain its importance and action.

- Oprah bookclub

Host a talkshow: students play the host, author, and cast of characters. Allow questions from the audience.

- Fictional friends

Who of all the characters would you want for a friend? Why? What would you do or talk about together?

- State of the Union

The President wants to recommend a book to the nation: tell him one important realization you had while reading this book and why he should recommend it.

- Interview question

When I interview prospective teachers, my first question is always, "What are you reading and do you like it?"

- Dear diary

Keep a diary as if you were a character in the story. Write down events that happen during the story and reflect on how they affected the character and why.

- Rosencrantz and Gildenstern

Write a story or journal from the perspective of characters with no real role in the story and show us what they see and think from their perspective.

- Improv

Get up in front of class or in a fishbowl and be whatever character the class calls out and do whatever they direct. Have fun with it.

- What if

Write about or discuss how the story would differ if the characters were something other than they are: a priest, another gender or race, a different age, or social class.

- Interrupted conversations

Pair up and trade-off reading through some text. Any time you have something to say about some aspect of the story, interrupt the reader and discuss, question, argue.

- Found poetry

Take sections of the story and, choosing carefully, create a found poem; then read these aloud and discuss.

- 13 views

Inspired by Stevens's poem "13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird," write a poem where each stanza offers a different view of a character or chapter.

- Personal ad

What would a particular character write in a personal ad for the newspaper? After posting on board, discuss.

- Holden meets Hamlet

What would one character (or set of them) in one story say to another if given the chance to talk or correspond? Write a dialogue, skit, or letter.

- Character analysis

Describe a character as a psychologist or recruiting officer might: what are they like? Examples? Why are they like that?

- Epistle poem

Write a poem in the form and voice of a letter: e.g., Phoebe to Holden from Catcher in the Rye.

- Write into

Find a "hole" in the story where the character disappears (off camera) for a time and describe what they do when we can't see them.

- The Woody Allen

In Take the Money, Allen interviews the parents of a man who became a bank robber. Write an imaginary interview with friends and family of a character whom they try to help you understand.

- Author interview

Write an interview or letter in which the character in a story asks the author a series of questions and reflects on how they feel about the way they were made.

- The Kuglemass

Woody Allen wrote a story in which the character can throw any book into a time machine and it takes you inside the book and the era. What would you do, say, think if you "traveled" into the story you are reading?

- Time machine

Instead of traveling into the book, write a scene or story in which the character(s) travel out of the book into today.

- Biography

Write a biography of one of the characters who most interests you.

- Autobiography

Have the character that most interests you write their autobiography of the time before, during, or after the story occurs.

- P.S.

After you read the story, write an epilogue in which you explain – using whatever tense and tone the author does – what happened to the character(s) next.

- Board game

Have groups design board games based on stories then play them. This is especially fun and works well with The Odyssey.

- Life graph

Using the Life Graph assignment, plot the events in the character's life during the story and evaluate their importance; follow up with discussion of graphs.

- Second chance

Talk or write about how it would change the story if a certain character had made a different decision earlier in the story (e.g., what if Huck of Huckleberry Finn had not run away?)

- Poetry connection

Bring in poems that are thematically related to the story. Integrate these into larger discussion. Use Poetry Index.

- Reader response

Pick the most important word/line/image/object/event in the chapter and explain why you chose it. Be sure to support all analysis with examples.

- Notes and quotes

Draw a line down the middle of the page. On one side write down important quotes, on the other comment on and analyze the quotes.

- Dear classmate

Using email or some other means of corresponding, write each other about the book as you read it, having a written conversation about the book.

- Convention introduction

You have been asked to introduce the book's author to a convention of English teachers.

What would you say? Write and deliver your speech.

What would you say? Write and deliver your speech. - Sing me a song

Write a song/ballad about the story, a character, or an event in the book.

- Write your own

Using the themes in the story, write your own story, creating your own characters and situation. It does not have to relate to the story at all aside from its theme.

- Executive summary

Take a 3x5 card and summarize what happened on one side. On the other, analyze the importance of what happened and the reasons it happened.

- Read aloud

One student starts the reading and goes until they wish to pass. They call on whomever they wish and that person picks up and continues reading for as long as they wish.

- Quaker reading

Like a Quaker meeting, one person stands and reads then sits and whomever wishes to picks up and reads for as long as with wish… and so it goes.

- Pageant of the Masters

In Los Angeles this remarkable event asks groups to stage different classical paintings in real life.

People would try to do a still life of some scene from a book or play. The class should then discuss what is going on in this human diorama.

People would try to do a still life of some scene from a book or play. The class should then discuss what is going on in this human diorama. - Create a diorama

Create a diorama of a particularly important scene such as the courtroom or Ewells' house in To Kill a Mockingbird.

- Day in court

Use the story as the basis for a court trial; students can be witnesses, expert witnesses called to testify, judge, jury, bailiff, reporter; great fun for a couple days.

- Censorship defense

Imagine that the book you are reading has been challenged by a special interest group. Students must write a letter defending the book, using specific evidence from the book to support their ideas.

- Call for censorship

In order to better understand all sides to an argument, imagine you are someone who feels this particular book should not be read and write a letter in which you argue it should be removed.

- Speculation

Based on everything you know now in the story, what do you think will happen and why do you think that?

- Questions anyone?

Students make a list of a certain number of questions they have about a particular character or aspect of the book; use these as the basis for class discussion.

- Newspaper connection

Have students read the newspapers and magazines to find articles that somehow relate to issues and ideas in the book(s) you are reading. Bring those articles in and discuss.

- Jigsaw

Organize the class into groups, each one with a specific focus. After a time rotate so that new groups are formed to share what they discussed in their previous group.

- Open mind

Draw an empty head and inside of it draw any symbols or words or images that are bouncing around in the mind of the character of a story. Follow it up with writing or discussion to explain and explore responses.

- Interrogation

A student must come up before the class and, pretending to be a character or the author, answer questions from the class.

- Post-Its

If they are using a school book in which they cannot make notes or marks, encourage them to keep a pack of Post-Its with them and make notes on these.

- Just the facts, ma'am

Acting as a reporter, ask the students the basic questions to facilitate a discussion: who, what, where, why, when, how?

- SQ3R

When reading a textbook or article, try this strategy:

1.

(S)urvey the assigned reading by first skimming through it

(S)urvey the assigned reading by first skimming through it2. then formulate (Q)uestions by turning all chapter headings and subheadings into questions to answer as you read

3. next (R)ead the assigned section and try to answer those questions you formulated

4. now (R)ecite the information by turning away from the text as soon as you've finished reading the assigned section and reiterate it in your own words

5. finally, (R)eview what you read by going back to your questions, the chapter headings, and asking yourself what they are all referring to, what they mean

- Brainstorming/Webbing

Put a character or other word in the middle of a web. Have students brainstorm associations while you write them down, then have them make connections between ideas and discuss or write about them.

- Cultural literacy

Find out what students already know and address what they need to know before reading a story or certain part of a story.

- Storyboard

Individually or in groups, create a storyboard for the chapter or story.

- Interactive story

If you have a student who is a computer genius, have them create a multimedia, interactive version of the story.

- Cyber guides

Search the Web for interactive trailers or virtual tours based on the books you might be studying.

- Tableau

Similar to the Pageant of the Masters, this option asks you to create a still life setting; then someone steps up to touch different characters who come alive and talk from their perspective about the scene.

- Audio books

There are many audio editions of books we teach now available – some are even read by famous stars who turn the book into its own audio performance. Recommend audio books to students with reading difficulties or play portions of them in class.

- Sound off!

Play a video version of a book you are reading – only turn off the sound while they watch it.

Have them narrate or discuss or write about what is happening, what the actors are revealing about the story through their gestures. Then compare what you saw with what you read.

Have them narrate or discuss or write about what is happening, what the actors are revealing about the story through their gestures. Then compare what you saw with what you read. - Narrate your own reading

Show kids how you read a text by reading it aloud and interrupting yourself to explain how you grapple with it as you go. Model your own thinking process; kids often don't know what it "looks like" to think.

- Magnetic poetry

If working with a poem, enlarge it on copier or computer and cut all words up into pieces; place in an envelope and have groups create poems from these words. Later on discuss using the same words for different texts. Heavier stock paper is ideal for this activity.

- Venn diagram

Use a Venn diagram to help you organize your thinking about a text as you read it. Put differences between two books or characters on opposite sides and similarities in the middle.

- Write an essay

Using one of the different rhetorical modes, write an essay in which you make meaningful connections between the text and your own experiences or other texts you have read.

- P.O.V.

How would it change the story if you rewrote it in a different point of view (e.g., changed it from first to third person)? Try it!

- Daily edition

Using the novel as the basis for your stories, columns and editorials, create an newspaper or magazine based on or inspired by the book you are reading.

- Read recursively

On occasion circle back around to the beginning of the chapter or text to keep yourself oriented as to "the big picture." This is especially important if you have questions to answer based on reading.

- Oral history

If you are reading a historical text, have students interview people who have some familiarity with that time period or the subject of the book.

- Guest speaker

If you are reading a book that deals with a subject an expert might help them better understand, invite one in. Try the Veterans of Foreign Wars, for example, if reading about war.

- Storytelling

After reading a story, pair up with others and tell the story as a group, recalling it in order, piecing it together, and clarifying for each other when one gets lost.

- Reciprocal teaching

A designated student or group reads a section of a text and comes prepared to present or teach it to the class. Follow up with discussion for clarification.

- Make your own test

Have students create their own test or essay questions about the text. This allows them to simultaneously think about the story and prepare for the test on it.

- Recasting the text

Students rewrite a poem as a story, a short story as a poem or play. All rewrites should then be read and discussed so as to understand how the different genre work.

- Debates

Students reading controversial texts or novels with debatable subjects such as 1984 should debate the issues.

- Literature circles

Students gather in groups to discuss the text and then report out to the class for full-class discussion.

- That was then, this is now

After reading the text, create a Before/After list to compare the ways in which characters or towns have changed over the course of the story.

Follow up with discussion of reasons.

Follow up with discussion of reasons.

Effect of reading on brain activity

Author: Thomas Oppong

Reading makes the brain work.

Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body.

It allows us to surf the vastness of space, time, history, and offers us a deeper look at various ideas, concepts and the very essence of knowledge.

Roberto Bolagno says: "Reading is like thinking, praying, talking to a friend, expressing your thoughts, listening to others' ideas, enjoying music, seeing beautiful scenery and walking along the beach." nine0005

Our brain works when we read - it develops, changes, creates new connections and different images depending on what we read.

Reading increases the density of neural connections

When we read, our brain changes and develops in amazing ways.

As you read these words, your brain is decoding a series of abstract symbols and synthesizing the result into complex ideas.

This is an amazing process.

The brain while reading can be compared to the cohesiveness of playing a symphony orchestra during a live performance - while reading, different parts of the brain are involved in the same way to increase the ability to decode text.

Reading "reflashes" parts of our brain. Mariann Wolfe explains in her book Proust and the Squid: The Fiction and Science of the Human Reading Brain

In the 1950s, the squid's long central axial cylinder showed scientists how neurons fire and communicate information to each other. The image of a squid contains a metaphor for comparing literature and science - approx. trans.) :

People invented reading only a couple of millennia ago. With this invention, we have rewired the organization of our brains, which in turn has expanded our ways of thinking, and this has reshaped the intellectual evolution of us as a species. <...> This skill became available to our ancestors only because the human brain has an amazing ability to create new connections among existing structures.This process was made possible by the ability of the brain to change in the course of acquiring new experiences. nine0036

Reading engages several brain functions, including visual and auditory processes, phonemic recognition, fluency, comprehension, and more.

According to ongoing research at Haskins Laboratories on spoken and written word cognition, reading provides more time for reflection, processing, visualization, and internal interpretation than viewing or listening. nine0005

Daily reading can slow down age-related cognitive decline and keep your brain sharp.

Reading stimulates logical thinking

Research shows that reading not only helps develop fluid intelligence but also conscious perception along with with emotional intelligence.

Fluid intelligence is the ability to solve problems, understand and recognize meaningful elements. nine0005

Reading can increase fluid intelligence, and it can improve conscious understanding of the text.

A Stanford study found a neurobiological difference between reading for pleasure and focused reading, such as when taking a test.

Blood enters different neural regions depending on how we read.

A study published in 2011 in the Annual Review of Psychology found an overlap in the areas of the brain responsible for text comprehension and the cellular structures used for interaction. nine0005

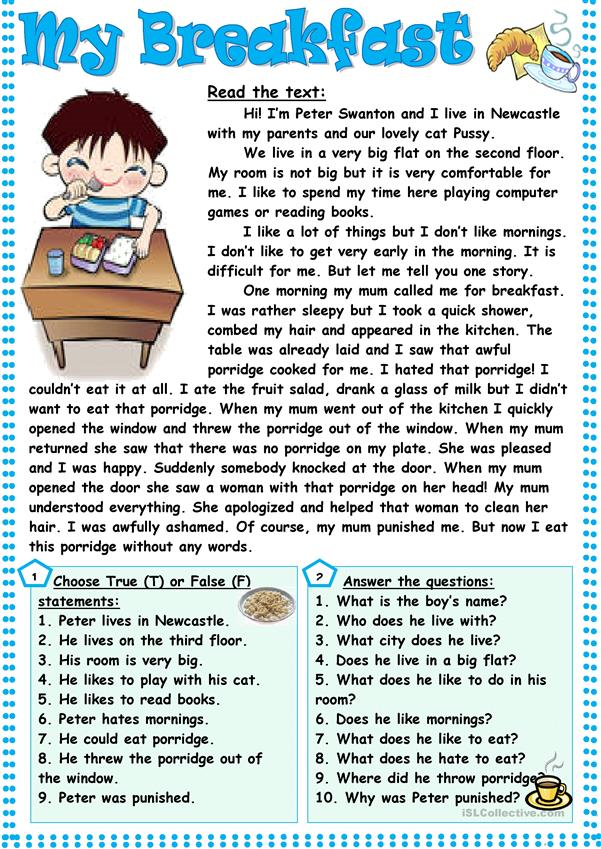

Reading makes us emotionally educated

Reading plays an important social role.

When we read fiction, we mentally imagine the event, situation, characters and other details described by the author.

This is a total immersion process.

In her book Anne LaMotte Bird by Bird. Notes on writing and life in general writes:

<...> for some of us, books are more precious than almost everything in the world. What a miracle that in these small, hard, almost flat bricks of paper, new worlds are hidden that sing to you, console, soothe or inspire you.Books help us understand who we are and how we should act. They explain what kinship and friendship are, show how to live and how to die. nine0036

Psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuel Castano of The New School (Private Research University in New York City - approx. Per.) proved that reading fiction contributes to the development of noticing and understanding the emotions of other people. This skill is extremely important for managing complex human relationships.

“Writers make you writers. In fiction, the incompleteness of characters forces your brain to try to understand the way others think,” says Kidd. nine0005

Researchers at Emory University found that reading a novel enhances neural connections in the area of the brain responsible for speech perception.

The work of the lead author, neuroscientist Gregory Burns, suggests that reading is also connected to a process known as embodied cognition Wednesday - approx. per.) . nine0005

“Neural changes that we found to be related to physical sensations and the motor system suggest that reading a novel can transport you into the protagonist's body.

<...> We already knew that good stories can make people feel like they're in a strange place, figuratively speaking. Now we see that changes can also occur at the biological level,” says Gregory Burns.

Reading improves concentration

In just one 30-minute time frame, the average person does a lot of work: working on a task, checking email, talking to colleagues, checking social media, and constantly responding to notifications. nine0005

Reading not only improves brain activity, but also allows you to extend the time of focus and concentration.

If you are having trouble concentrating, reading can help you increase your concentration time.

When you read a book, all your attention is focused on the plot or the desire to deepen knowledge in a certain area - the rest of the world disappears, and you can immerse yourself in the story, noticing every detail.

Well-structured books allow us to think consistently. Thus, the more we read, the more our brain develops the skill of connecting cause with effect.

nine0005

Try to read for 15-20 minutes in the morning before work (for example, while driving to work if using public transport).

You will be surprised how much more attentive you will become at work.

Dissolving in a book is an indescribable relaxation!

Develop the Habit of Reading

In a world where information is a new kind of currency, reading is the best source of continued learning, knowledge and acquisition of even more currency. nine0005

Reading requires patience, diligence and determination.

Reading is like any other skill. It has to be practiced regularly and constantly.

Whether you prefer the convenience of a smartphone with an alluring backlight or the feel of a real book in your hand, make time to read in any way.

The next time you're shopping for a book or downloading it on the Kindle, stop and think about what you're reading—reading always has an effect. nine0005

Dig Deeper

My new Thinking in Models course is open for enrollment.

It's designed to help you think clearly, solve complex problems, and make tough decisions with confidence. Join a community of people who have chosen as their mission to learn to think clearly, work better, solve problems of different levels of complexity and make difficult decisions with confidence!

You can also subscribe to Postanly Weekly (my free daily digest of the best posts about behavioral changes that affect health, well-being and productivity). Subscribe and get a free copy of my new book One Hundred Percent Better: Small Cost, Maximum Value. Join over 45,000 people who are determined to build a better life. nine0005

A joint project of the Lingvopand Club and LL editors

What reading does to our brain

Actually, our brain is not naturally suited for reading: this ability develops only in those who are specially taught to distinguish letters. Despite this, the “unnatural” skill has changed us forever: we can imagine places we have never been, solve complex cognitive puzzles, and (perhaps) become smarter with every book we read.

We figure out how we manage to feel like a character in our favorite book and why we should learn to read as early as possible. nine0140

Brain reshaping

French neuroscientist Stanislas Dehan jokes that the children who participate in his research feel like astronauts when they lie down in an MRI machine that resembles a spaceship capsule. During the tests, Dean asks them to read and count in order to monitor the work of the brain. The scan shows how even one word read revitalizes the brain.

The brain acts logically, says Dean: at first, letters for it are just visual information, objects. But then he relates this visual code to the already existing knowledge about the letters. That is, a person recognizes the letters and only then understands their meaning and how they are pronounced. This is because nature did not assume that a person would invent this particular mechanism for transmitting information. nine0005

Reading is a revolutionary technique, an artificial interface that literally rebuilt our brain, which originally did not have a special department for recognizing linguistic characters.

The brain had to adapt the primary visual cortex for this, through which the signal passes through the fusiform gyrus, which is responsible for face recognition. In the same gyrus there is a repository of knowledge about languages - it is also called a "mail box".

Together with colleagues from Brazil and Portugal, Dean published a study, the conclusion of which is that the "mailbox" is active only for those who can read, and is stimulated only by letters known to man: it will not respond to characters if you do not know Chinese . Reading also affects the work of the visual cortex: it begins to recognize objects more accurately, trying to distinguish one letter from another. The perception of sounds is transformed: thanks to reading, the alphabet is built into this process - hearing a sound, a person imagines a letter. nine0005

Become a hero

There are mirror neurons in the temporal cortex and amygdala of the brain. It is thanks to them that people can repeat the movements of each other in a dance, parody someone or experience joy when looking at a smiling person.

“From the point of view of biological expediency, this is correct. It is more effective when the flock, the community has a single emotion: we all run away from danger together, fight the predator, celebrate the holidays, ”Vyacheslav Dubynin, Doctor of Biology, explains the importance of the mechanism. nine0005

An Emory University study proves that a person can feel empathy not only for a neighbor or passerby, but also for a character in a book. Reading participants in the experiment underwent a series of MRI scans, which showed increased activity in the central sulcus of the brain. Neurons in this region can translate thoughts into real sensations—for example, thoughts about future competitions into a feeling of exercise. And while reading, they literally put us in the shoes of our favorite hero. nine0005

“We don't know how long these neural changes can last. But the fact that the effect of even a casually read story was found in the brain after 5 days suggests that the most beloved books can influence you for much longer, Gregory Burns, lead researcher of the project, says.

For work and pleasure

However, not all books are meant to arouse empathy and interest in your brain. In her book Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel, Professor Lisa Zanshine writes that usually the favorite genre is the one that suits the reader's brain, for example, complex detective stories - lovers of logic problems. But to get to the feelings themselves, you often have to break through complex cognitive exercises that, for example, Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen included in their lyrics, Zunshine believes, such as the phrases “she understood that he thought she was laughing at herself, and that bothered her." Such constructions make you experience several emotions in succession. nine0005

Writer Maria Konnikova also remembers Jane Austen. In the article “What Jane Austen can teach us about how the brain pays attention,” she talks about an experiment by neuroscientist Natalie Phillips on different perceptions of text. The study involved English students unfamiliar with Austen's Mansfield Park.

At first, they read the text in a relaxed mode - just to have fun. Then the experimenter asked them to analyze the text, pay attention to the structure, main themes, and warned them that they would have to write an essay about what they had read. All this time, the students were in the MRI machine, which monitored the work of their brain. With more relaxed reading, the centers responsible for pleasure were activated in the brain. When immersed in the text, activity shifted to the area responsible for attention and analysis. In fact, having set different goals, the students saw two different texts. nine0005

Does reading make you smarter?

It is believed that reading is good for the intellect. But is it really so? An experiment by the Society for Research in Child Development among 1,890 identical twins aged 7, 9, 10, 12, and 16 showed that early reading skills affect the overall level of intelligence in the future. Children who were actively taught to read at an early age turned out to be smarter than their identical twins, who did not receive such help from adults.

And New York University researchers found that reading short fiction immediately improves the ability to recognize human emotions. The participants in this study were divided into groups and determined the emotions of the actors by photographs of their eyes after reading popular literature, non-fiction or fiction novels - the result of the latter group was much more impressive. nine0005

Many are skeptical about the results of these experiments. So, employees of Pace University conducted a similar experiment on guessing emotions and found that people who read more throughout their lives do indeed better decode facial expressions, but scientists urge not to confuse causality with correlation. They are not sure that the results of the experiment are related specifically to reading: perhaps these people read more precisely because they are empathic, and not vice versa. And MIT cognitive neuroscientist Rebecca Sachs notes that the research method itself is very weak, but scientists have to use it due to the lack of better technologies.