Children learning to write

5 Ways to Support Children Learning to Write

One of the most common referrals I get as a school-based occupational therapist and evaluator is in regard to students’ difficulty with handwriting skills. These referrals have at least tripled during the pandemic because kids are on the computer more and have less exposure to handwriting practice, pencil-to-paper tasks, and other related activities that build on complex underlying skills that lead to functional handwriting output.

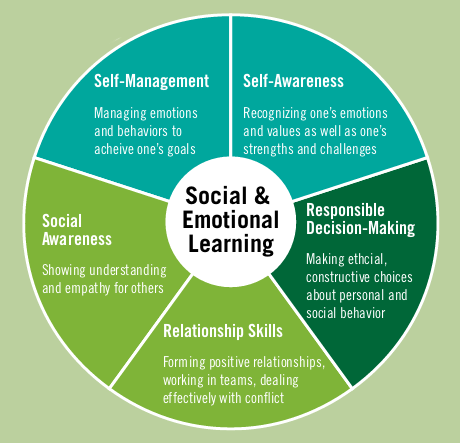

Writing is a developmental and whole-body process. It incorporates all the systems of the body, including the visual-motor, cognitive-perceptual, ocular motor (control of voluntary eye movement), proprioceptive (sense of self-movement and body positioning), and vestibular (balance), and even social and emotional skills and self-regulation. These all need to work together in order in the seemingly simple task of writing, so it’s no wonder that many children find learning to write a challenge.

If you’re an educator, therapist, or caregiver, it’s important to understand why a child might struggle with handwriting, including the underlying skills that can impact functional handwriting legibility. Gross motor skills, fine motor skills, attention, sensory processing, and visual motor skills all play a role.

Over time, strategies that are concrete and routine can build on the underlying component skills connected to the physiological and cognitive mechanics of handwriting.

Introducing Handwriting Strategies

Be sure to introduce therapeutic handwriting strategies when the child is calm and regulated, and make sure they have as much control over the process as possible. For example, ask them what parts of the handwriting process feel difficult, and have them choose the specific supplies or tools they will use to improve their handwriting. Be sure to explain each strategy to them as you are giving them instructions.

Also, be aware of the fact that when a child is struggling with handwriting, it’s often because of a combination of underlying skill component difficulties affecting handwriting (e.g., sensory processing and fine motor, among the others listed below), so they may need a combination of strategies to make progress.

Visual Motor: ‘I-Spy Bean Bag’

An I-spy bean bag can be created out of various materials, including a pencil case filled with small objects such as magnetic refrigerator letters, beads, and even small toys.

Tell the child that when they search for the letters for a sight word (e.g., t-h-e) in an I-spy bean bag, they’re strengthening their eyes and their brain. Then, when they follow up by writing the word, they’re strengthening their eyes and working on their handwriting simultaneously.

Fine Motor: ‘Motor Tool Box’

A motor tool box is a bin of different fun items (e.g., Lego pieces, putty, Play-Doh, and coloring books) that, when handled, can help children build up strength in the small muscles of their hands.

When a child starts to engage with items in the motor tool box, explain to them that doing so helps strengthen the “intrinsic” (inside) muscles of their hands—the muscles that are important for writing.

Attention: ‘Toe Touch Cross’

This is a simple whole-body exercise to do before a child starts writing, especially if they have issues with staying focused. It’s centered around what occupational therapists call crossed midline input, which means that it allows the two sides of the brain to connect. Touch Toe Cross also provides vestibular input, meaning that it engages the balance system and helps keep the body and head steady in space because the head goes below the level of the heart—a calming body posture.

It’s centered around what occupational therapists call crossed midline input, which means that it allows the two sides of the brain to connect. Touch Toe Cross also provides vestibular input, meaning that it engages the balance system and helps keep the body and head steady in space because the head goes below the level of the heart—a calming body posture.

Try telling the child that being focused and calm, while feeling their body, is essential to being able to get their ideas on paper. Tell them to do the following:

1. Stand up with their legs shoulder-width apart.

2. Spread their arms out.

3. Cross their right arm, reaching it across their midsection to touch their left foot.

4. Repeat on the other side.

Sensory Processing: ‘Sensory Bin Writing’

A sensory bin is a tub, bowl, or tray full of rice, moon sand, noodles, or dried beans that a child can “write” in with their fingers, helping them to remember what they write. A sensory bin adds an important tactile aspect that reinforces letter and number shapes in muscle memory.

Have the child choose which material they would like to use, or try different things on different days. They can practice writing letters, numbers, or words with their fingers in the bin. This activity also gives children a sensory break; tell them it’s like a change of scene for when their hands get bored by writing all the time.

Often they like to hear that sensory bin practice is a great strategy to use if their body is feeling wiggly or their mind is becoming overwhelmed.

Gross Motor: ‘Trace the 8’

A simple figure 8 or infinity sign can help guide a child’s hands and build gross motor skills.

Tell the child to picture an “8” lying on its side and pretend that they’ve drawn it. Ask them to picture how it looks and imagine that it’s right in front of them. Tell them to take their right hand and trace the imagined 8 carefully, using the whole arm and the shoulder as well, and then repeat with their left hand. Then they can take both hands together, with one fist on top of the other, and trace over the 8 with both hands.

Learning to Read and Write: What Research Reveals

Children learn to use symbols, combining their oral language, pictures, print, and play into a coherent mixed medium and creating and communicating meanings in a variety of ways. From their initial experiences and interactions with adults, children begin to read words, processing letter-sound relations and acquiring substantial knowledge of the alphabetic system. As they continue to learn, children increasingly consolidate this information into patterns that allow for automaticity and fluency in reading and writing. Consequently reading and writing acquisition is conceptualized better as a developmental continuum than as an all-or-nothing phenomenon.

But the ability to read and write does not develop naturally, without careful planning and instruction. Children need regular and active interactions with print. Specific abilities required for reading and writing come from immediate experiences with oral and written language. Experiences in these early years begin to define the assumptions and expectations about becoming literate and give children the motivation to work toward learning to read and write. From these experiences children learn that reading and writing are valuable tools that will help them do many things in life.

Experiences in these early years begin to define the assumptions and expectations about becoming literate and give children the motivation to work toward learning to read and write. From these experiences children learn that reading and writing are valuable tools that will help them do many things in life.

The beginning years (birth through preschool)

Even in the first few months of life, children begin to experiment with language. Young babies make sounds that imitate the tones and rhythms of adult talk; they "read" gestures and facial expressions, and they begin to associate sound sequences frequently heard words with their referents (Berk 1996). They delight in listening to familiar jingles and rhymes, play along in games such as peek-a-boo and pat-a-cake, and manipulate objects such as board books and alphabet blocks in their play. From these remarkable beginnings children learn to use a variety of symbols.

In the midst of gaining facility with these symbol systems, children acquire through interactions with others the insight that specific kinds of marks print also can represent meanings. At first children will use the physical and visual cues surrounding print to determine what something says. But as they develop an understanding of the alphabetic principle, children begin to process letters, translate them into sounds, and connect this information with a known meaning. Although it may seem as though some children acquire these understandings magically or on their own, studies suggest that they are the beneficiaries of considerable, though playful and informal, adult guidance and instruction (Durkin 1966; Anbar 1986).

At first children will use the physical and visual cues surrounding print to determine what something says. But as they develop an understanding of the alphabetic principle, children begin to process letters, translate them into sounds, and connect this information with a known meaning. Although it may seem as though some children acquire these understandings magically or on their own, studies suggest that they are the beneficiaries of considerable, though playful and informal, adult guidance and instruction (Durkin 1966; Anbar 1986).

Considerable diversity in children's oral and written language experiences occurs in these years (Hart & Risley 1995). In home and child care situations, children encounter many different resources and types and degrees of support for early reading and writing (McGill-Franzen & Lanford 1994). Some children may have ready access to a range of writing and reading materials, while others may not; some children will observe their parents writing and reading frequently, others only occasionally; some children receive direct instruction, while others receive much more casual, informal assistance.

What this means is that no one teaching method or approach is likely to be the most effective for all children (Strickland 1994). Rather, good teachers bring into play a variety of teaching strategies that can encompass the great diversity of children in schools. Excellent instruction builds on what children already know, and can do, and provides knowledge, skills, and dispositions for lifelong learning. Children need to learn not only the technical skills of reading and writing but also how to use these tools to better their thinking and reasoning (Neuman 1998).

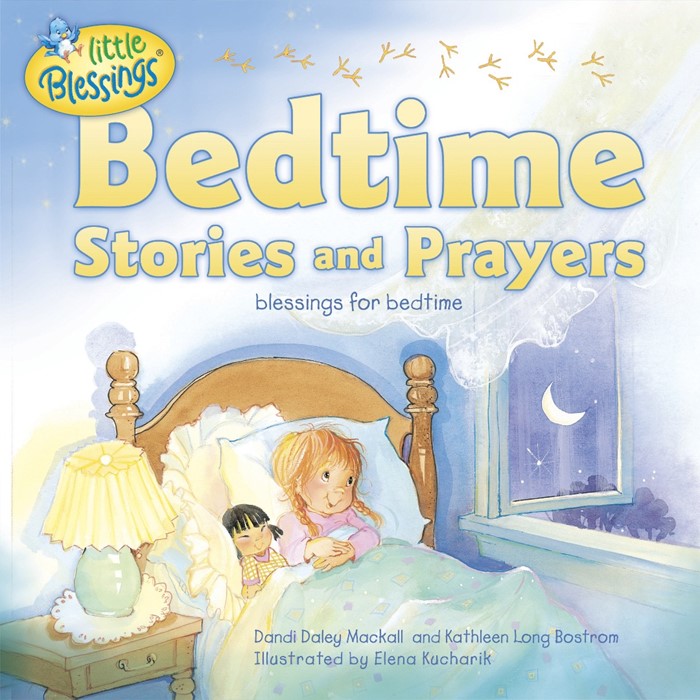

The single most important activity for building these understandings and skills essential for reading success appears to be reading aloud to children (Wells 1985; Bus, Van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini 1995). High-quality book reading occurs when children feel emotionally secure (Bus & Van Ijzendoorn 1995; Bus et al. 1997) and are active participants in reading (Whitehurst et al. 1994). Asking predictive and analytic questions in small-group settings appears to affect children's vocabulary and comprehension of stories (Karweit & Wasik 1996). Children may talk about the pictures, retell the story, discuss their favorite actions, and request multiple rereadings. It is the talk that surrounds the storybook reading that gives it power, helping children to bridge what is in the story and their own lives (Dickinson & Smith 1994; Snow et al. 1995). Snow (1991) has described these types of conversations as "decontextualized language" in which teachers may induce higher-level thinking by moving experiences in stories from what the children may see in front of them to what they can imagine.

Children may talk about the pictures, retell the story, discuss their favorite actions, and request multiple rereadings. It is the talk that surrounds the storybook reading that gives it power, helping children to bridge what is in the story and their own lives (Dickinson & Smith 1994; Snow et al. 1995). Snow (1991) has described these types of conversations as "decontextualized language" in which teachers may induce higher-level thinking by moving experiences in stories from what the children may see in front of them to what they can imagine.

A central goal during these preschool years is to enhance children's exposure to and concepts about print (Clay 1979, 1991; Holdaway 1979; Teale 1984; Stanovich & West 1989). Some teachers use Big Books to help children distinguish many print features, including the fact that print (rather than pictures) carries the meaning of the story, that the strings of letters between spaces are words and in print correspond to an oral version, and that reading progresses from left to right and top to bottom. In the course of reading stories, teachers may demonstrate these features by pointing to individual words, directing children's attention to where to begin reading, and helping children to recognize letter shapes and sounds. Some researchers (Adams 1990; Roberts 1998) have suggested that the key to these critical concepts, such as developing word awareness, may lie in these demonstrations of how print works.

In the course of reading stories, teachers may demonstrate these features by pointing to individual words, directing children's attention to where to begin reading, and helping children to recognize letter shapes and sounds. Some researchers (Adams 1990; Roberts 1998) have suggested that the key to these critical concepts, such as developing word awareness, may lie in these demonstrations of how print works.

Children also need opportunity to practice what they've learned about print with their peers and on their own. Studies suggest that the physical arrangement of the classroom can promote time with books (Morrow & Weinstein 1986; Neuman & Roskos 1997). A key area is the classroom library a collection of attractive stories and informational books that provides children with immediate access to books. Regular visits to the school or public library and library card registration ensure that children's collections remain continually updated and may help children develop the habit of reading as lifelong learning. In comfortable library settings children often will pretend to read, using visual cues to remember the words of their favorite stories. Although studies have shown that these pretend readings are just that (Ehri & Sweet 1991), such visual readings may demonstrate substantial knowledge about the global features of reading and its purposes.

In comfortable library settings children often will pretend to read, using visual cues to remember the words of their favorite stories. Although studies have shown that these pretend readings are just that (Ehri & Sweet 1991), such visual readings may demonstrate substantial knowledge about the global features of reading and its purposes.

Storybooks are not the only means of providing children with exposure to written language. Children learn a lot about reading from the labels, signs, and other kinds of print they see around them (McGee, Lomax, & Head 1988; Neuman & Roskos 1993). Highly visible print labels on objects, signs, and bulletin boards in classrooms demonstrate the practical uses of written language. In environments rich with print, children incorporate literacy into their dramatic play (Morrow 1990; Vukelich 1994; Neuman & Roskos 1997), using these communication tools to enhance the drama and realism of the pretend situation. These everyday, playful experiences by themselves do not make most children readers. Rather they expose children to a variety of print experiences and the processes of reading for real purposes.

Rather they expose children to a variety of print experiences and the processes of reading for real purposes.

For children whose primary language is other than English, studies have shown that a strong basis in a first language promotes school achievement in a second language (Cummins 1979). Children who are learning English as a second language are more likely to become readers and writers of English when they are already familiar with the vocabulary and concepts in their primary language. In this respect, oral and written language experiences should be regarded as an additive process, ensuring that children are able to maintain their home language while also learning to speak and read English (Wong Fillmore, 1991). Including non-English materials and resources to the extent possible can help to support children's first language while children acquire oral proficiency in English.

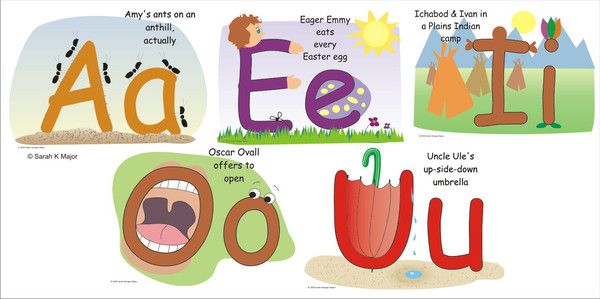

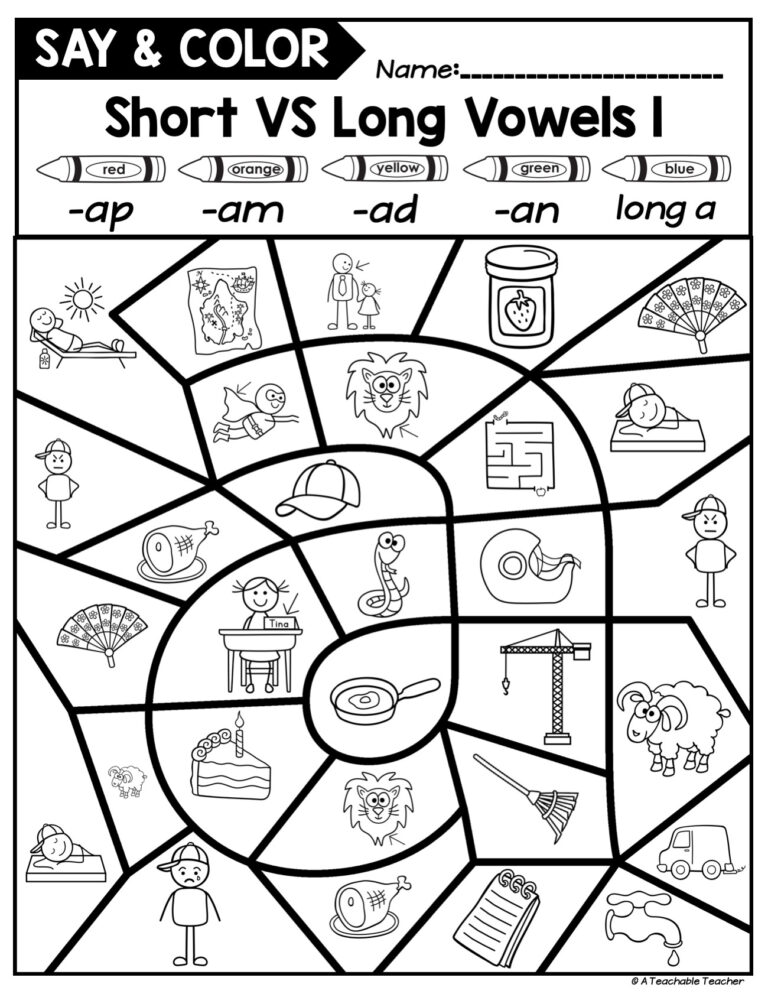

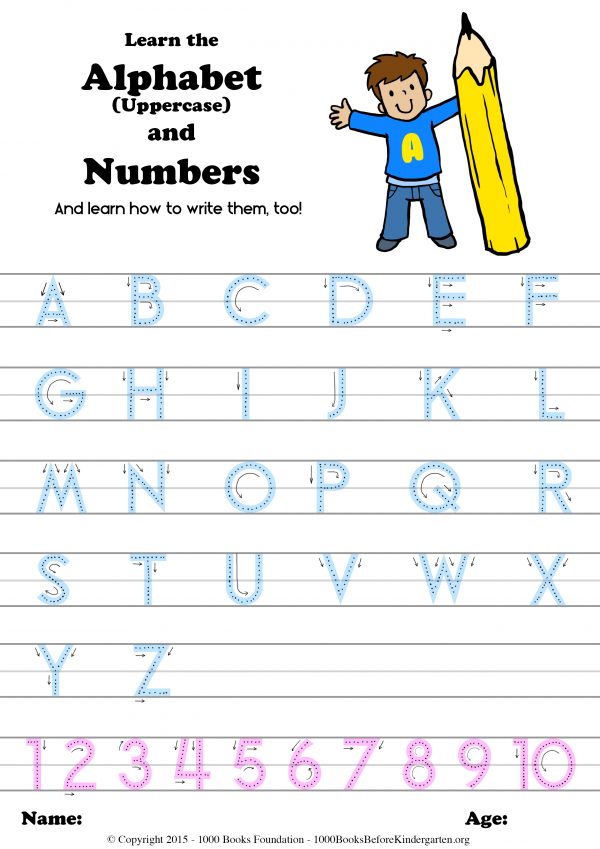

A fundamental insight developed in children's early years through instruction is the alphabetic principle, the understanding that there is a systematic relationship between letters and sounds (Adams 1990). The research of Gibson and Levin (1975) indicates that the shapes of letters are learned by distinguishing one character from another by its type of spatial features. Teachers will often involve children in comparing letter shapes, helping them to differentiate a number of letters visually. Alphabet books and alphabet puzzles in which children can see and compare letters may be a key to efficient and easy learning.

The research of Gibson and Levin (1975) indicates that the shapes of letters are learned by distinguishing one character from another by its type of spatial features. Teachers will often involve children in comparing letter shapes, helping them to differentiate a number of letters visually. Alphabet books and alphabet puzzles in which children can see and compare letters may be a key to efficient and easy learning.

At the same time children learn about the sounds of language through exposure to linguistic awareness games, nursery rhymes, and rhythmic activities. Some research suggests that the roots of phonemic awareness, a powerful predictor of later reading success, are found in traditional rhyming, skipping, and word games (Bryant et al. 1990). In one study, for example (Maclean, Bryant, & Bradley 1987), researchers found that three-year-old children's knowledge of nursery rhymes specifically related to their more abstract phonological knowledge later on. Engaging children in choral readings of rhymes and rhythms allows them to associate the symbols with the sounds they hear in these words.

Although children's facility in phonemic awareness has been shown to be strongly related to later reading achievement, the precise role it plays in these early years is not fully understood. Phonemic awareness refers to a child's understanding and conscious awareness that speech is composed of identifiable units, such as spoken words, syllables, and sounds. Training studies have demonstrated that phonemic awareness can be taught to children as young as age five (Bradley & Bryant 1983; Lundberg, Frost, & Petersen 1988; Cunningham 1990; Bryne & Fielding-Barnsley 1991). These studies used tiles (boxes) (Elkonin 1973) and linguistic games to engage children in explicitly manipulating speech segments at the phoneme level.

Yet, whether such training is appropriate for younger-age children is highly suspect. Other scholars find that children benefit most from such training only after they have learned some letter names, shapes, and sounds and can apply what they learn to real reading in meaningful contexts (Cunningham 1990; Foorman et al. 1991). Even at this later age, however, many children acquire phonemic awareness skills without specific training but as a consequence of learning to read (Wagner & Torgesen 1987; Ehri 1994). In the preschool years sensitizing children to sound similarities does not seem to be strongly dependent on formal training but rather from listening to patterned, predictable texts while enjoying the feel of reading and language.

1991). Even at this later age, however, many children acquire phonemic awareness skills without specific training but as a consequence of learning to read (Wagner & Torgesen 1987; Ehri 1994). In the preschool years sensitizing children to sound similarities does not seem to be strongly dependent on formal training but rather from listening to patterned, predictable texts while enjoying the feel of reading and language.

Children acquire a working knowledge of the alphabetic system not only through reading but also through writing. A classic study by Read (1971) found that even without formal spelling instruction, preschoolers use their tacit knowledge of phonological relations to spell words. Invented spelling (or phonic spelling) refers to beginners' use of the symbols they associate with the sounds they hear in the words they wish to write. For example, a child may initially write b or bk for the word bike, to be followed by more conventionalized forms later on.

Some educators may wonder whether invented spelling promotes poor spelling habits. To the contrary, studies suggest that temporary invented spelling may contribute to beginning reading (Chomsky 1979; Clarke 1988). One study, for example, found that children benefited from using invented spelling compared to having the teacher provide correct spellings in writing (Clarke 1988). Although children's invented spellings did not comply with correct spellings, the process encouraged them to think actively about letter-sound relations. As children engage in writing, they are learning to segment the words they wish to spell into constituent sounds.

To the contrary, studies suggest that temporary invented spelling may contribute to beginning reading (Chomsky 1979; Clarke 1988). One study, for example, found that children benefited from using invented spelling compared to having the teacher provide correct spellings in writing (Clarke 1988). Although children's invented spellings did not comply with correct spellings, the process encouraged them to think actively about letter-sound relations. As children engage in writing, they are learning to segment the words they wish to spell into constituent sounds.

Classrooms that provide children with regular opportunities to express themselves on paper, without feeling too constrained for correct spelling and proper handwriting, also help children understand that writing has real purpose (Graves 1983; Sulzby 1985; Dyson 1988). Teachers can organize situations that both demonstrate the writing process and get children actively involved in it. Some teachers serve as scribes and help children write down their ideas, keeping in mind the balance between children doing it themselves and asking for help. In the beginning these products likely emphasize pictures with few attempts at writing letters or words. With encouragement, children begin to label their pictures, tell stories, and attempt to write stories about the pictures they have drawn. Such novice writing activity sends the important message that writing is not just handwriting practice children are using their own words to compose a message to communicate with others.

In the beginning these products likely emphasize pictures with few attempts at writing letters or words. With encouragement, children begin to label their pictures, tell stories, and attempt to write stories about the pictures they have drawn. Such novice writing activity sends the important message that writing is not just handwriting practice children are using their own words to compose a message to communicate with others.

Thus the picture that emerges from research in these first years of children's reading and writing is one that emphasizes wide exposure to print and to developing concepts about it and its forms and functions. Classrooms filled with print, language and literacy play, storybook reading, and writing allow children to experience the joy and power associated with reading and writing while mastering basic concepts about print that research has shown are strong predictors of achievement.

Back to top

In kindergarten

Knowledge of the forms and functions of print serves as a foundation from which children become increasingly sensitive to letter shapes, names, sounds, and words. However, not all children typically come to kindergarten with similar levels of knowledge about printed language. Estimating where each child is developmentally and building on that base, a key feature of all good teaching, is particularly important for the kindergarten teacher. Instruction will need to be adapted to account for children's differences. For those children with lots of print experiences, instruction will extend their knowledge as they learn more about the formal features of letters and their sound correspondences.

However, not all children typically come to kindergarten with similar levels of knowledge about printed language. Estimating where each child is developmentally and building on that base, a key feature of all good teaching, is particularly important for the kindergarten teacher. Instruction will need to be adapted to account for children's differences. For those children with lots of print experiences, instruction will extend their knowledge as they learn more about the formal features of letters and their sound correspondences.

For other children with fewer prior experiences, initiating them to the alphabetic principle, that a limited set of letters comprises the alphabet and that these letters stand for the sounds that make up spoken words, will require more focused and direct instruction. In all cases, however, children need to interact with a rich variety of print (Morrow, Strickland, & Woo 1998).

In this critical year kindergarten teachers need to capitalize on every opportunity for enhancing children's vocabulary development. One approach is through listening to stories (Feitelson, Kita, & Goldstein 1986; Elley 1989). Children need to be exposed to vocabulary from a wide variety of genres, including informational texts as well as narratives. The learning of vocabulary, however, is not necessarily simply a byproduct of reading stories (Leung & Pikulski 1990). Some explanation of vocabulary words prior to listening to a story is related significantly to children's learning of new words (Elley 1989). Dickinson and Smith (1994), for example, found that asking predictive and analytic questions before and after the readings produced positive effects on vocabulary and comprehension.

Repeated readings appear to further reinforce the language of the text as well as to familiarize children with the way different genres are structured (Eller, Pappas, & Brown 1988; Morrow 1988). Understanding the forms of informational and narrative texts seems to distinguish those children who have been well read to from those who have not (Pappas 1991). In one study, for example, Pappas found that with multiple exposures to a story (three readings), children's retelling became increasingly rich, integrating what they knew about the world, the language of the book, and the message of the author. Thus, considering the benefits for vocabulary development and comprehension, the case is strong for interactive storybook reading (Anderson 1995). Increasing the volume of children's playful, stimulating experiences with good books is associated with accelerated growth in reading competence.

In one study, for example, Pappas found that with multiple exposures to a story (three readings), children's retelling became increasingly rich, integrating what they knew about the world, the language of the book, and the message of the author. Thus, considering the benefits for vocabulary development and comprehension, the case is strong for interactive storybook reading (Anderson 1995). Increasing the volume of children's playful, stimulating experiences with good books is associated with accelerated growth in reading competence.

Activities that help children clarify the concept of word are also worthy of time and attention in the kindergarten curriculum (Juel 1991). Language experience charts that let teachers demonstrate how talk can be written down provide a natural medium for children's developing word awareness in meaningful contexts. Transposing children's spoken words into written symbols through dictation provides a concrete demonstration that strings of letters between spaces are words and that not all words are the same length. Studies by Clay (1979) and Bissex (1980) confirm the value of what many teachers have known and done for years: Teacher dictations of children's stories help develop word awareness, spelling, and the conventions of written language.

Studies by Clay (1979) and Bissex (1980) confirm the value of what many teachers have known and done for years: Teacher dictations of children's stories help develop word awareness, spelling, and the conventions of written language.

Many children enter kindergarten with at least some perfunctory knowledge of the alphabet letters. An important goal for the kindergarten teacher is to reinforce this skill by ensuring that children can recognize and discriminate these letter shapes with increasing ease and fluency (Mason 1980; Snow, Burns, & Griffin 1998). Children's proficiency in letter naming is a well-established predictor of their end-of-year achievement (Bond & Dykstra 1967, Riley 1996), probably because it mediates the ability to remember sounds. Generally a good rule according to current learning theory (Adams 1990) is to start with the more easily visualized uppercase letters, to be followed by identifying lowercase letters. In each case, introducing just a few letters at a time, rather than many, enhances mastery.

At about the time children are readily able to identify letter names, they begin to connect the letters with the sounds they hear. A fundamental insight in this phase of learning is that a letter and letter sequences map onto phonological forms. Phonemic awareness, however, is not merely a solitary insight or an instant ability (Juel 1991). It takes time and practice.

Children who are phonemically aware can think about and manipulate sounds in words. They know when words rhyme or do not; they know when words begin or end with the same sound; and they know that a word like bat is composed of three sounds /b/ /a/ /t/ and that these sounds can be blended into a spoken word. Popular rhyming books, for example, may draw children's attention to rhyming patterns, serving as a basis for extending vocabulary (Ehri & Robbins 1992). Using initial letter cues, children can learn many new words through analogy, taking the familiar word bake as a strategy for figuring out a new word, lake.

Further, as teachers engage children in shared writing, they can pause before writing a word, say it slowly, and stretch out the sounds as they write it. Such activities in the context of real reading and writing help children attend to the features of print and the alphabetic nature of English.

There is accumulated evidence that instructing children in phonemic awareness activities in kindergarten (and first grade) enhances reading achievement (Stanovich 1986; Lundberg, Frost, & Petersen 1988; Bryne & Fielding-Barnsley 1991, 1993, 1995). Although a large number of children will acquire phonemic awareness skills as they learn to read, an estimated 20% will not without additional training. A statement by the IRA (1998) indicates that "the likelihood of these students becoming successful as readers is slim to none

This figure [20%], however, can be substantially reduced through more systematic attention to engagement with language early on in the child's home, preschool and kindergarten classes. "

"

A study by Hanson and Farrell (1995), for example, examined the long-term benefits of a carefully developed kindergarten curriculum that focused on word study and decoding skills, along with sets of stories so that children would be able to practice these skills in meaningful contexts. High school seniors who early on had received this type of instruction outperformed their counterparts on reading achievement, attitude toward schooling, grades, and attendance.

In kindergarten many children will begin to read some words through recognition or by processing letter-sound relations. Studies by Domico (1993) and Richgels (1995) suggest that children's ability to read words is tied to their ability to write words in a somewhat reciprocal relationship. The more opportunities children have to write, the greater the likelihood that they will reproduce spellings of words they have seen and heard. Though not conventional, these spellings likely show greater letter-sound correspondences and partial encoding of some parts of words, like SWM for swim, than do the inventions of preschoolers (Clay 1975).

To provide more intensive and extensive practice, some teachers try to integrate writing in other areas of the curriculum, like literacy-related play (Neuman & Roskos 1992), and other project activities (Katz & Chard 1989). These types of projects engage children in using reading and writing for multiple purposes while they are learning about topics meaningful to them.

Early literacy activities teach children a great deal about writing and reading but often in ways that do not look much like traditional elementary school instruction. Capitalizing on the active and social nature of children's learning, early instruction must provide rich demonstrations, interactions, and models of literacy in the course of activities that make sense to young children. Children must also learn about the relation between oral and written language and the relation between letters, sounds, and words. In classrooms built around a wide variety of print activities, then in talking, reading, writing, playing, and listening to one another, children will want to read and write and feel capable that they can do so.

Back to top

The primary grades

Instruction takes on a more formal nature as children move into the elementary grades. Here it is virtually certain that children will receive at least some instruction from a commercially published product, like a basal or literature anthology series.

Although research has clearly established that no one method is superior for all children (Bond & Dykstra 1967; Snow, Burns, & Griffin 1998), approaches that favor some type of systematic code instruction along with meaningful connected reading report children's superior progress in reading. Instruction should aim to teach the important letter-sound relationships, which once learned are practiced through having many opportunities to read. Most likely these research findings are a positive result of the Matthew Effect, the rich-get-richer effects that are embedded in such instruction; that is, children who acquire alphabetic coding skills begin to recognize many words (Stanovich 1986). As word recognition processes become more automatic, children are likely to allocate more attention to higher-level processes of comprehension. Since these reading experiences tend to be rewarding for children, they may read more often; thus reading achievement may be a by-product of reading enjoyment.

As word recognition processes become more automatic, children are likely to allocate more attention to higher-level processes of comprehension. Since these reading experiences tend to be rewarding for children, they may read more often; thus reading achievement may be a by-product of reading enjoyment.

One of the hallmarks of skilled reading is fluent, accurate word identification (Juel, Griffith, & Gough 1986). Yet instruction in simply word calling with flashcards is not reading. Real reading is comprehension. Children need to read a wide variety of interesting, comprehensible materials, which they can read orally with about 90 to 95% accuracy (Durrell & Catterson 1980). In the beginning children are likely to read slowly and deliberately as they focus on exactly what's on the page. In fact they may seem "glued to print" (Chall 1983), figuring out the fine points of form at the word level. However, children's reading expression, fluency, and comprehension generally improve when they read familiar texts. Some authorities have found the practice of repeated rereadings in which children reread short selections significantly enhances their confidence, fluency, and comprehension in reading (Samuels 1979; Moyer 1982).

Some authorities have found the practice of repeated rereadings in which children reread short selections significantly enhances their confidence, fluency, and comprehension in reading (Samuels 1979; Moyer 1982).

Children not only use their increasing knowledge of letter-sound patterns to read unfamiliar texts. They also use a variety of strategies. Studies reveal that early readers are capable of being intentional in their use of metacognitive strategies (Brown, & DeLoache 1978; Rowe 1994) Even in these early grades, children make predictions about what they are to read, self-correct, reread, and question if necessary, giving evidence that they are able to adjust their reading when understanding breaks down. Teacher practices, such as the Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (DRTA), effectively model these strategies by helping children set purposes for reading, ask questions, and summarize ideas through the text (Stauffer 1970).

But children also need time for independent practice. These activities may take on numerous forms. Some research, for example, has demonstrated the powerful effects that children's reading to their caregivers has on promoting confidence as well as reading proficiency (Hannon 1995). Visiting the library and scheduling independent reading and writing periods in literacy-rich classrooms also provide children with opportunities to select books of their own choosing. They may engage in the social activities of reading with their peers, asking questions, and writing stories (Morrow & Weinstein 1986), all of which may nurture interest and appreciation for reading and writing.

These activities may take on numerous forms. Some research, for example, has demonstrated the powerful effects that children's reading to their caregivers has on promoting confidence as well as reading proficiency (Hannon 1995). Visiting the library and scheduling independent reading and writing periods in literacy-rich classrooms also provide children with opportunities to select books of their own choosing. They may engage in the social activities of reading with their peers, asking questions, and writing stories (Morrow & Weinstein 1986), all of which may nurture interest and appreciation for reading and writing.

Supportive relationships between these communication processes lead many teachers to integrate reading and writing in classroom instruction (Tierney & Shanahan 1991). After all, writing challenges children to actively think about print. As young authors struggle to express themselves, they come to grips with different written forms, syntactic patterns, and themes. They use writing for multiple purposes: to write descriptions, lists, and stories to communicate with others. It is important for teachers to expose children to a range of text forms, including stories, reports, and informational texts, and to help children select vocabulary and punctuate simple sentences that meet the demands of audience and purpose. Since handwriting instruction helps children communicate effectively, it should also be part of the writing process (McGee & Richgels 1996). Short lessons demonstrating certain letter formations tied to the publication of writing provide an ideal time for instruction. Reading and writing workshops, in which teachers provide small-group and individual instruction, may help children to develop the skills they need for communicating with others.

They use writing for multiple purposes: to write descriptions, lists, and stories to communicate with others. It is important for teachers to expose children to a range of text forms, including stories, reports, and informational texts, and to help children select vocabulary and punctuate simple sentences that meet the demands of audience and purpose. Since handwriting instruction helps children communicate effectively, it should also be part of the writing process (McGee & Richgels 1996). Short lessons demonstrating certain letter formations tied to the publication of writing provide an ideal time for instruction. Reading and writing workshops, in which teachers provide small-group and individual instruction, may help children to develop the skills they need for communicating with others.

Although children's initial writing drafts will contain invented spellings, learning about spelling will take on increasing importance in these years (Henderson & Beers 1980; Richgels 1986). Spelling instruction should be an important component of the reading and writing program since it directly affects reading ability. Some teachers create their own spelling lists, focusing on words with common patterns, high-frequency words, as well as some personally meaningful words from the children's writing. Research indicates that seeing a word in print, imagining how it is spelled, and copying new words is an effective way of acquiring spellings (Barron 1980).

Spelling instruction should be an important component of the reading and writing program since it directly affects reading ability. Some teachers create their own spelling lists, focusing on words with common patterns, high-frequency words, as well as some personally meaningful words from the children's writing. Research indicates that seeing a word in print, imagining how it is spelled, and copying new words is an effective way of acquiring spellings (Barron 1980).

Nevertheless, even though the teacher's goal is to foster more conventionalized forms, it is important to recognize that there is more to writing than just spelling and grammatically correct sentences. Rather, writing has been characterized by Applebee (1977) as "thinking with a pencil." It is true that children will need adult help to master the complexities of the writing process. But they also will need to learn that the power of writing is expressing one's own ideas in ways that can be understood by others.

As children's capabilities develop and become more fluent, instruction will turn from a central focus on helping children learn to read and write to helping them read and write to learn. Increasingly the emphasis for teachers will be on encouraging children to become independent and productive readers, helping them to extend their reasoning and comprehension abilities in learning about their world. Teachers will need to provide challenging materials that require children to analyze and think creatively and from different points of view. They also will need to ensure that children have practice in reading and writing (both in and out of school) and many opportunities to analyze topics, generate questions, and organize written responses for different purposes in meaningful activities.

Increasingly the emphasis for teachers will be on encouraging children to become independent and productive readers, helping them to extend their reasoning and comprehension abilities in learning about their world. Teachers will need to provide challenging materials that require children to analyze and think creatively and from different points of view. They also will need to ensure that children have practice in reading and writing (both in and out of school) and many opportunities to analyze topics, generate questions, and organize written responses for different purposes in meaningful activities.

Throughout these critical years accurate assessment of children's knowledge, skills, and dispositions in reading and writing will help teachers better match instruction with how and what children are learning. However, early reading and writing cannot simply be measured as a set of narrowly-defined skills on standardized tests. These measures often are not reliable or valid indicators of what children can do in typical practice, nor are they sensitive to language variation, culture, or the experiences of young children (Shepard & Smith 1988; Shepard 1994; Johnston 1997).

Rather, a sound assessment should be anchored in real-life writing and reading tasks and continuously chronicle a wide range of children's literacy activities in different situations. Good assessment is essential to help teachers tailor appropriate instruction to young children and to know when and how much intensive instruction on any particular skill or strategy might be needed.

By the end of third grade, children will still have much to learn about literacy. Clearly some will be further along the path to independent reading and writing than others. Yet with high-quality instruction, the majority of children will be able to decode words with a fair degree of facility, use a variety of strategies to adapt to different types of text, and be able to communicate effectively for multiple purposes using conventionalized spelling and punctuation. Most of all they will have come to see themselves as capable readers and writers, having mastered the complex set of attitudes, expectations, behaviors, and skills related to written language.

Back to top

How to teach a child to write: advice from a neuropsychologist | Chalk

In the age of the Internet and technology, more and more parents are wondering if their child will need handwriting skills and why this is given such attention in schools. We asked Anna Polishchuk, clinical and perinatal psychologist, child neuropsychologist, author of the educational project "Children Ready for the Future", to talk about the importance of writing and proper preparation for it.

Knowing how to write is really important

Written language is not just the ability to write letters. This is a complex integrative process. When we master writing, almost all areas of the brain work at the same time - and they do it in a coordinated manner, creating a whole functional system.

The visual areas are responsible for reproducing and retaining in the working memory the image of a word and the image of a letter; auditory - for working with a phoneme. That is why, when children first begin to write, they pronounce each word aloud. The motor and deep parts of the brain are responsible for sufficient muscle tone, correct subtle movements, and jewelry switching between positions. And of course, all this is accompanied by an analysis and search for semantically suitable words.

The motor and deep parts of the brain are responsible for sufficient muscle tone, correct subtle movements, and jewelry switching between positions. And of course, all this is accompanied by an analysis and search for semantically suitable words.

Can you imagine how many tasks a child's brain solves per second when it prints a letter?

We are not just learning to write - we are creating a new functional system, linking all parts of the brain into a single network. The brain changes even morphologically. Try to do old Russian calligraphy - and you will feel how much concentration, tone, and attention it requires.

If schools replace writing with typing on a keyboard, this will certainly facilitate the learning process, but this will affect the cognitive functions of children.

When to start preparing

Beautiful writing largely depends on how ready the child's hand is. We are talking here about the general tone, and about the posture that the child takes for writing, and, of course, about motor skills.

It is rare to find a clumsy child with good handwriting - because problems with gross motor skills drag along and difficulties with fine motor skills.

Photo: Juriah Mosin / ShutterstockPreparing the hand for writing naturally starts at birth: even just playing in the sandbox, the child develops motor skills. Jumping, jumping rope games, hopscotch, cycling, rope parks contribute to the same goal.

Today, the idea of early - anticipatory - development is popular among parents, but there is simply no point in actively putting a child at prescription before 4-5 years old. By this age, it is enough to be able to hold a pencil correctly.

A child is ready to learn to write if he has the following skills:

- circular brush amplitudes, including the ability to draw wavy lines;

- the ability to draw straight solid lines: first vertical and horizontal, then diagonally;

- the ability to draw broken lines in different directions (hatching).

How to get interested in writing

Writing is a complex integrative function, and in order to generate interest in it, it is important to understand where it starts.

Written speech is always the transmission of information. From a child to an adult. And it starts with a drawing! When a child scribbles, brings sloppy colored pictures to mom, or gives dad scribbled paper, he is trying to share his thoughts. Adults need to encourage this. The child encodes his words in lines and dashes, tries to convey an idea through an image - this is an analogue of the encryption system in a letter: we also encode the meaning in letters.

It is therefore very important to initiate drawing. Offer pencils, crayons, paints and brushes, try to draw with your fingers, put dots on paper, traces of palms, learn to color, paint over, depict the first "cephalopod" men.

Often today's children do not like to draw because of problems with general tone or its asymmetry. Gadgets, physical inactivity, incorrect posture - all this affects health, it is difficult for children to hold the pressure of a pencil.

Gadgets, physical inactivity, incorrect posture - all this affects health, it is difficult for children to hold the pressure of a pencil.

Children love to be adults, and this is the whole secret of learning: write yourself!

Leave notes, write stories, read to each other and show vivid emotions when the child repeats after you. Praise for trying. Tell us how you like to receive colorful notes and hang beautiful drawings on the refrigerator.

Start a gallery and save all the creations of children! Show that you care about what the child wants to convey to you in this image!

All this is the basis of written speech. The pleasure of drawing gradually turns into the pleasure of writing letters, and then words. If a child does not have such a desire by the age of 5–6, return to the previous levels: draw and make scribble notes.

How can I help my child learn to write?

First of all, in a natural way, through everyday life. Cooking, cleaning, washing - it's all about motor skills.

It would be useful to include drawing, passing mazes, playing with geoboards and mosaics, and graphic dictations in your daily activities.

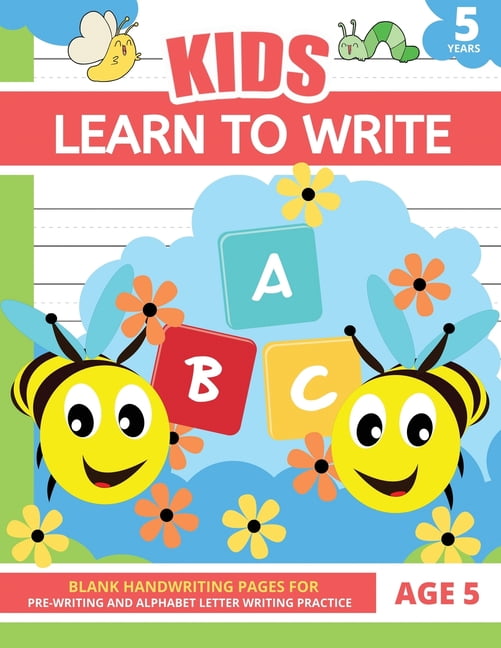

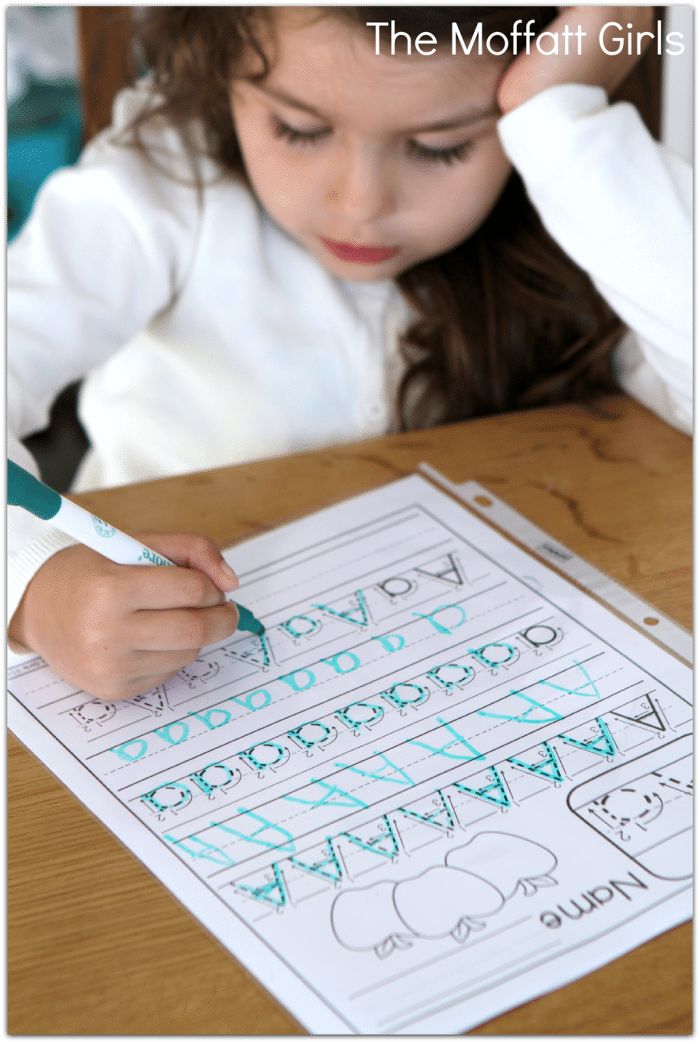

Photo: sakkmesterke / ShutterstockYou can also use special training aids for orientation on the sheet and in the image of the letter. For example, KUMON notebooks "Spatial Thinking" and "Learning to write block letters of the Russian alphabet."

The latter has several advantages:

- the child learns to write letters from simple to complex;

- different directions and arm amplitudes are trained;

- in each exercise there are landmarks - arrows, with the help of which it is easier to remember the spelling and the vector of hand movement when writing. But many teachers at school face this: children write letters in the opposite direction, against gravity, or mirror.

We must not forget an important criterion: such benefits should be offered to a child only when he is already approaching the age of learning to read, that is, closer to 5 years.

Do I need to correct errors

Mirroring letters, writing from right to left are all normal stages of learning. You can gently correct the child, explain how to do it right. The only thing you definitely shouldn’t pay attention to before the first grade is spelling.

If the problems have not gone away naturally by the age of 6.5–7 years, it is worth contacting a neuropsychologist.

And one more thing: if a child tears paper with a pen or pencil while writing, most often this indicates muscle hypertonicity. In this case, it makes sense to consult an orthopedist and try hand trainers and various relaxation techniques.

Cover image: ANDREI_SITURN / Shutterstock

step-by-step instructions with expert advice

And then the first letter, the first word, appears on a piece of paper. Uneven and uncertain. But long-awaited. How to teach a child to write? How can I help him develop writing skills at home? The answers are in our material

Alena Gerashchenko

Author of the KP

Anna Shumilova

Methodist of the Uchi. ru platform

ru platform

Almaz Marsov

Principal of the Ponyatno online school

Writing is an important skill that is learned in preschool and elementary school. The opinions of experts differ: someone thinks that it is better not to put a letter to the child at home, someone, on the contrary, is convinced that it is the parent who opens the world of writing to the child. We believe that you can start developing the skill of writing letters at home - learn to draw pictograms, connect dots on paper, draw - not write - letters. Leave the capital letters and intricate, ornate words to the schoolteachers. Teach your child the basics. Get him interested in drawing, help develop spatial perception of reality, teach hand-finger coordination. We will tell you step by step how to teach your child the basics of writing before school.

Step-by-step instructions for teaching a child to write

Everything needs a system. In training, a systematic, everyday contribution to the development of skills is very important. Compliance with the following steps will lay the foundation for high-quality development of the child's writing.

In training, a systematic, everyday contribution to the development of skills is very important. Compliance with the following steps will lay the foundation for high-quality development of the child's writing.

Step #1. Get interested

Start telling children in a fun way about what writing is, why it is needed, how it originated and developed. The main thing is to present the story not with dry facts. Do it brightly, colorfully, picturesquely. Show your child photographs of the walls of the Egyptian pyramids, which depict various drawings and hieroglyphs. Tell your son or daughter the story of the Novgorod boy Onfim, who wrote birch bark letters in the 13th century, show his monument, and the letters and drawings. The emotional presentation of the story, coupled with illustrative material - all this will resonate with the child. Also invite the child to do the exercises during the stories. Here are a couple of activities to accompany stories that will help your child understand the nature of writing and want to learn to write on their own as soon as possible.

Exercise 1

Show your child pictograms (wall pictures that our ancestors used to communicate information to each other), invite him to fantasize and make up an oral story based on the pictures he saw.

Exercise 2

And vice versa: make up a story with the child and invite him to illustrate it in detail with the help of pictures. Such tasks, among other things, develop fantasy, speech and storytelling skills.

After the pictograms, go on to explain ideographic writing. It sounds complicated, but in fact, ideography uses simplified pictograms - symbols. The Chinese language is built on symbolism (principle 1 character = 1 word), designations in the transport sector. Acquaintance with the symbols will be interesting to the child if you pay attention to them during a walk.

You can teach a child to draw simple images with meaning: for example, two wavy horizontal lines symbolize a pond; crossed circle - prohibition, the word "no" and so on. Stories about ideographic writing and "practical ideography" will expand the horizons of the baby, teach him to perceive the world around him more sensitively, develop creative thinking, and teach spatial perception.

Stories about ideographic writing and "practical ideography" will expand the horizons of the baby, teach him to perceive the world around him more sensitively, develop creative thinking, and teach spatial perception.

If you feel that the kid is ready for more (asks questions, draws a lot), tell him about modern writing, about languages. Explain that the Egyptians wrote from right to left - it was inconvenient: hieroglyphs, drawings were smeared by hand. Show your child that writing like this is not very convenient. Tell us that we inherit the experience of the ancient Greeks - we write from left to right. Take a digression into history and tell the fidget that Latin was developed from the ancient Greek language, and it became the official language of the church. Latin formed the basis of many other languages (English, German). And our ancestors developed Slavic writing, the Russian language. Conclude that today we use the Russian script, an alphabet of 33 letters. Show the child a primer, study each letter with him. Invite the child to circle each of them with a finger.

Invite the child to circle each of them with a finger.

Step #2: Practice Moderately

Spend no more than 15 minutes a day on letter-drawing. Let the child during this time repeat the outlines of the letters from the primer. Let him try to draw them. If the letters are crooked - it's not scary. It should not scare you that the signs crawling out from under the pencil of a novice writer do not quite look like letters. Transform the process of learning to write into a game - sit next to the baby and draw incomprehensible signs of eyes, smiles, legs and arms. So the child will have more fun. He will trust you, the process, the primer, and next time he will accurately draw a letter, and not a hippopotamus or a fat cat. The main rule is to learn to draw letters for a quarter of an hour. Let the child rest. Even the creativity that the kid is passionate about can exhaust him and discourage him from learning to write.

Spend no more than 15 minutes a day on letter-drawing. Photo: globallookpress.com

Photo: globallookpress.com

Step No. 3. “We wrote, we wrote, our fingers were tired!” Develop fine motor skills

Together with your child, do modeling from plasticine, build towers and wonder animals from the designer, draw, color, make applications, lay out mosaics, embroider with a cross. Practice daily, captivate your child with creativity and at the same time help him develop fine motor skills of his hands. If he learns to manipulate various small objects, it will be easier for him to learn to write. Fine motor skills training allows you to develop the temporal regions of the brain that are responsible for speech. If the baby has good motor skills, he writes well, then it will also not be difficult for him to tell a poem beautifully or come up with a story and vividly present it to his family, classmates, teacher. In man, everything is very subtly interconnected.

See also

"Mom, buy": how to deal with children's requests in the shopping center, parental abuse in response: perhaps each of us was an unwitting witness to such heartbreaking scenes. Together with the teacher-psychologist Ekaterina Bolysheva, we learn to avoid mistakes that can lead to children's tantrums in the store0005

Together with the teacher-psychologist Ekaterina Bolysheva, we learn to avoid mistakes that can lead to children's tantrums in the store0005

The child's back must not be bent by the wheel. Incorrect posture will negatively affect the health of the internal organs of the baby, his psychological state, even the activity of his thinking. Do sports with your child (gymnastics, swimming). Show him how to walk correctly - straight with a slightly raised chin, rushing the top of his head up. Teach him to sit at the table correctly: the child should bend in the lower back, the shoulders should be slightly relaxed, lowered. The kid should not lean heavily on the back of the chair and shift the entire body weight onto the table. The muscles of the upper body should be toned and slightly tense, but the neck should not be pulled forward. A slight tilt of the head is acceptable. In any case, consult with your pediatrician about how to properly seat your child at the table. He will suggest effective practices for controlling the muscles of the back, neck, arms and will talk in detail about why it is so important to develop the habit of sitting at the table correctly.

Popular questions and answers

How to teach a child to write beautifully?

Anna Shumilova, methodologist of the Uchi.ru platform:

— Is it really necessary to demand beautiful handwriting and perfectly clean notebooks from a child? Some parents are worried when teachers lower their children's grades for the design of notebooks, and they believe that the main thing is to write down the exercise without errors, give the correct answer to the question, and find the right solution to the problem. Other parents, on the contrary, force the child to rewrite the work with blots and expect the teacher to spend enough time on calligraphy in the classroom. The truth, as always, lies somewhere in the middle. Any teacher knows from his own experience that in dirty, untidy notebooks there are rarely work without errors. Order and accuracy help to form a harmonious, logical thinking. If the student writes quickly and readably, this becomes a huge advantage for him in mastering the school material. We are of the opinion that the teacher should teach children to write. Any adult person knows for himself that it is quite difficult to change handwriting or the way letters are written. Incorrect spelling of letters will not help either the first grader or his teacher, but, on the contrary, will cause additional difficulties. However, a parent can help.

If the student writes quickly and readably, this becomes a huge advantage for him in mastering the school material. We are of the opinion that the teacher should teach children to write. Any adult person knows for himself that it is quite difficult to change handwriting or the way letters are written. Incorrect spelling of letters will not help either the first grader or his teacher, but, on the contrary, will cause additional difficulties. However, a parent can help.

If you want to help your child prepare for writing, it is best to start with block letters and do no more than 20 minutes at a time. You should also explain to the future student the basic principles of writing.

1. The line is the letter house. It has a floor and a ceiling. You can not break through the floor and stick out the legs of the letters from there. You can't break through the ceiling and stick your head out like a giraffe. If such a nuisance nevertheless happened with the letters, you can give the child a colored pencil and ask them to underline the hooligan letters and ask what exactly is wrong with them. After that, be sure to underline the letters that turned out to be written correctly, and praise the child. Another great exercise is coloring. We select a small part of the picture and ask to color it without going beyond the outline of the figure. For little naughty fingers, it's not so easy.

After that, be sure to underline the letters that turned out to be written correctly, and praise the child. Another great exercise is coloring. We select a small part of the picture and ask to color it without going beyond the outline of the figure. For little naughty fingers, it's not so easy.

2. When we write letters, we imagine the rails on which the train travels. If the rails cross, the train will derail and fall. The letters should not dance on the line, but stand like soldiers. After the kid writes a line, you can take a ruler and draw vertical lines through the letters. If the rails are straight everywhere, then the train arrived wonderfully, and you can put a big fat plus on this line! Over time, the rails may become slanted, but should remain parallel.

3. Written letters consist of a certain set of elements: sticks, hooks, loops and ovals. As we wrote above, it’s better not to collect letters without a teacher, but it’s worth practicing writing sticks of different lengths. To work with an oval, we can draw a box. The oval should look out the window and not get stuck in it. If a child draws a circle, then his chubby cheeks will not crawl through the window. Cheeks will have to be erased. In addition to writing, we advise you to have an A4 lined notebook. If you don't have one, the regular one will do. First, the parent himself draws a large beautiful printed letter. The child paints its elements in different colors. Then we write giant letters (several centimeters high). At the beginning of the line, the parent puts dots, the child circles them, and only then appends the line on his own. Next come the middle letters and, towards the end of the page, the midget letters. While the child is writing, you can ask him to pronounce the sound of a capital letter in a rough voice, the sound of a middle letter in a normal voice, and squeak the sound of a midget letter. That will be much more fun!

To work with an oval, we can draw a box. The oval should look out the window and not get stuck in it. If a child draws a circle, then his chubby cheeks will not crawl through the window. Cheeks will have to be erased. In addition to writing, we advise you to have an A4 lined notebook. If you don't have one, the regular one will do. First, the parent himself draws a large beautiful printed letter. The child paints its elements in different colors. Then we write giant letters (several centimeters high). At the beginning of the line, the parent puts dots, the child circles them, and only then appends the line on his own. Next come the middle letters and, towards the end of the page, the midget letters. While the child is writing, you can ask him to pronounce the sound of a capital letter in a rough voice, the sound of a middle letter in a normal voice, and squeak the sound of a midget letter. That will be much more fun!

How to teach a child to write quickly?

Anna Shumilova:

— A quick letter is a continuous letter. He will be taught by a teacher at school. As soon as the literacy period ends (around February 1st grade) and the Russian language begins, you can dictate very short dictations to your child. You can use the collection of O. V. Uzorova. You can come up with short funny sentences about your child yourself. This will generate additional interest in the letter. Only practice and control over the maximum continuity of the hand while writing one word will help to write quickly. So that the child does not forget what this or that letter looks like (which happens up to grade 3), it is necessary to spend minutes of calligraphy.

He will be taught by a teacher at school. As soon as the literacy period ends (around February 1st grade) and the Russian language begins, you can dictate very short dictations to your child. You can use the collection of O. V. Uzorova. You can come up with short funny sentences about your child yourself. This will generate additional interest in the letter. Only practice and control over the maximum continuity of the hand while writing one word will help to write quickly. So that the child does not forget what this or that letter looks like (which happens up to grade 3), it is necessary to spend minutes of calligraphy.

Read also

A child's motivation to study at school

"Komsomolskaya Pravda" tells why children are so looking forward to Knowledge Day, but after a week they suddenly start to get sick and tell how to make the child motivated to study

How to teach a child to write at home?

Almaz Marsov, director of the online school "It's clear":

- Learning to write can be divided into 2 stages: preparing the hand for writing and writing itself. At the preparatory stage, you need to teach the child to coordinate brush movements. To do this, play and create with your child. Coloring pages, hatching tasks, as well as graphic exercises will help you: graphomotor tests, labyrinths, tasks of the series “connect by dots”, “connect by dotted lines”, “draw the second half” and so on. In a word, these are the tasks that will teach a child to use a pencil or pen - to set the direction of the lines, control the force of pressure, control the size of the image, the clarity of the lines and smoothness. After that, you can start writing letters and numbers.

At the preparatory stage, you need to teach the child to coordinate brush movements. To do this, play and create with your child. Coloring pages, hatching tasks, as well as graphic exercises will help you: graphomotor tests, labyrinths, tasks of the series “connect by dots”, “connect by dotted lines”, “draw the second half” and so on. In a word, these are the tasks that will teach a child to use a pencil or pen - to set the direction of the lines, control the force of pressure, control the size of the image, the clarity of the lines and smoothness. After that, you can start writing letters and numbers.

The main principle is to go from simple to complex. First, you can learn to write part of a letter or number, then the letter or number in full. It is important to show the child the correct sequence of writing letters and numbers: from left to right, from top to bottom. Too many children come to school with the wrong letter and are faced with the need to relearn. To avoid this, we recommend that you complete tasks with the children and control the correct spelling until they develop a writing skill.

Of course, the best helper is prescription. As soon as the child masters the letter with a hint, you can move on to a more difficult option - writing in a notebook. The more practice, the more confident and better the child's writing. Finally, the skill needs to be consolidated and improved. Write everywhere: sign drawings and crafts, write on asphalt with crayons, on misted glass with your finger - turn writing into a game and an interesting activity for a child. The more you practice, the faster and more beautiful the child will write.

What kind of games help develop writing skills in a child?

Anna Shumilova:

— Almost any exercise can be turned into a game. It depends on the submission of the material. You can draw letters with your nose in the air, collect letters from sweets. You can color the letters, circle them with dots, and then give them gifts. If the letter is oval, it is necessary to give objects that also contain an oval in their image.