Childrens learn to read

Learn to Read

"Multimedia can be very beneficial for young children. For example, research shows that children who see a story's action animated are more likely to remember it," says early reading expert Susan B. Neuman, a professor of education at the University of Michigan. “Plus, computer programs enable children to hear a story repeated many times until they master its language. But there's no substitute for a parent reading to a child. Parents can mediate the process, and help a child connect their book to their own lives. This is critical to the learning process."

How to Shop Smart

To help make sense of the many "learn to read" CDs, Web sites, and toys available, ask yourself these questions:

- Is the program age-appropriate? (Is the font size suitable for your child? Is there too much text on each screen? Is the vocabulary level suitable?)

- Does the program encourage a sense of discovery? Does it allow your child to solve problems and make his own decisions?

- Does the program offer "intelligent" feedback? (When a child makes a mistake, how does the program respond?)

- Is the educational content presented systematically? (Does it build sequentially? Are there opportunities for children to demonstrate what they know days and even weeks after the initial "lesson"?)

- Does the program keep track of your child's progress?

- Might the program inspire your child to learn to read in other contexts? (What opportunities are there for connecting with physical books at home and in school?)

- How easily can your child control the features by himself? Are the audio instructions and feedback clear?

- Does the program include information for parents that clearly outlines the educational goals?

Every Child Is Different

Whether you are purchasing software, borrowing DVDs from the library, or visiting online learning sites, remember some basic notions about literacy education. First, every child will learn to read at her own pace. No two children become "literate" quite the same way. So multiple approaches, including technology, are useful. Scholastic's ClickSmart Reading, for example, uses animated adventures to motivate your child as she reads online storybooks and practices phonics, word recognition, and other early literacy skills. Don't miss Scholastic's apps for iPhone, iPod Touch and iPad to help promote literacy at home.

Second, learning to read is a very gradual process. There is no panacea that will make your child learn to read overnight. As long as he is presented with a variety of approaches, and receives support from you, he will most likely learn to read with skill and relative ease.

Finally, while the latest technology might seem essential, keep in mind that children learned to read long before there were computers or DVD players. There is nothing as powerful as having your child sit on your lap as you take him through one of your favorite stories. If he can't wait to turn the page, then he is headed in the right direction.

If he can't wait to turn the page, then he is headed in the right direction.

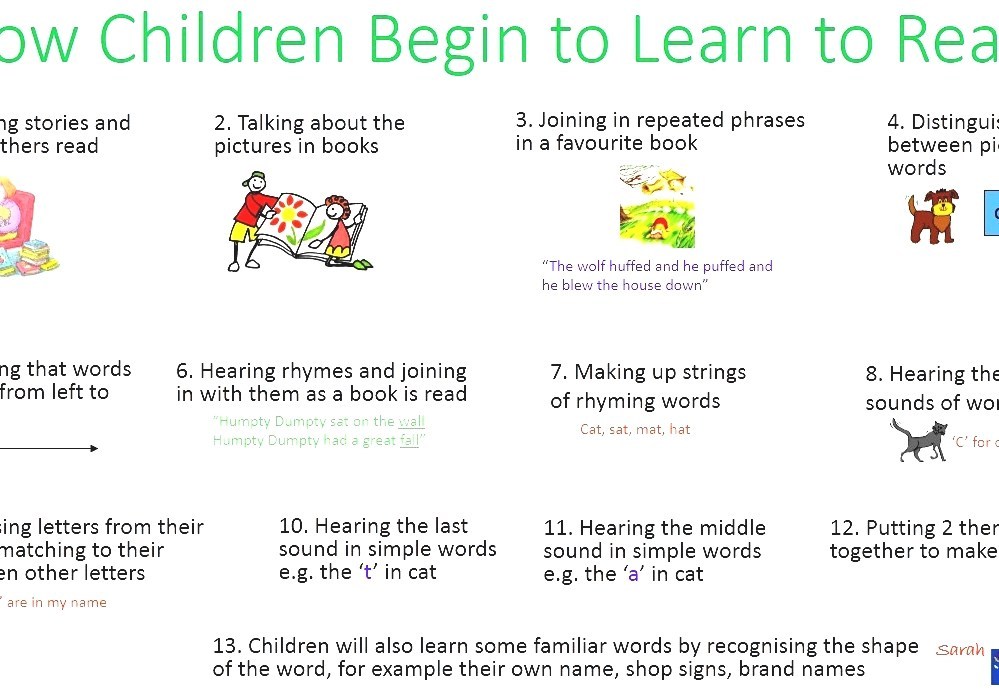

How Most Children Learn to Read

By: Derry Koralek, Ray Collins

Between the ages of four and nine, your child will have to master some 100 phonics rules, learn to recognize 3,000 words with just a glance, and develop a comfortable reading speed approaching 100 words a minute. He must learn to combine words on the page with a half-dozen squiggles called punctuation into something – a voice or image in his mind that gives back meaning. (Paul Kropp, 1996)

Emerging literacy

Emerging literacy describes the gradual, ongoing process of learning to understand and use language that begins at birth and continues through the early childhood years (i.e., through age eight). During this period children first learn to use oral forms of language (listening and speaking) and then begin to explore and make sense of written forms (reading and writing).

Listening and speaking

Emerging literacy begins in infancy as a parent lifts a baby, looks into her eyes, and speaks softly to her. It's hard to believe that this casual, spontaneous activity is leading to the development of language skills. This pleasant interaction helps the baby learn about the give and take of conversation and the pleasures of communicating with other people.

It's hard to believe that this casual, spontaneous activity is leading to the development of language skills. This pleasant interaction helps the baby learn about the give and take of conversation and the pleasures of communicating with other people.

Young children continue to develop listening and speaking skills as they communicate their needs and desires through sounds and gestures, babble to themselves and others, say their first words, and rapidly add new words to their spoken vocabularies. Most children who have been surrounded by language from birth are fluent speakers by age three, regardless of intelligence, and without conscious effort.

Each of the 6,000 languages in the world uses a different assortment of phonemes – the distinctive sounds used to form words. When adults hear another language, they may not notice the differences in phonemes not used in their own language. Babies are born with the ability to distinguish these differences. Their babbles include many more sounds than those used in their home language. At about 6 to 10 months, babies begin to ignore the phonemes not used in their home language. They babble only the sounds made by the people who talk with them most often.

At about 6 to 10 months, babies begin to ignore the phonemes not used in their home language. They babble only the sounds made by the people who talk with them most often.

During their first year, babies hear speech as a series of distinct, but meaningless words. By age 1, most children begin linking words to meaning. They understand the names used to label familiar objects, body parts, animals, and people. Children at this stage simplify the process of learning these labels by making three basic assumptions:

- Labels (words) refer to a whole object, not parts or qualities (Flopsy is a beloved toy, not its head or color).

- Labels refer to classes of things rather than individual items (Doggie is the word for all four-legged animals).

- Anything that has a name can only have one name (for now, Daddy is Daddy, and not a man or Jake).

As children develop their language skills, they give up these assumptions and learn new words and meanings. From this point on, children develop language skills rapidly. Here is a typical sequence:

From this point on, children develop language skills rapidly. Here is a typical sequence:

- At about 18 months, children add new words to their vocabulary at the astounding rate of one every 2 hours.

- By age 2, most children have 1 to 2,000 words and combine two words to form simple sentences such as: "Go out." "All gone."

- Between 24 to 30 months, children speak in longer sentences.

- From 30 to 36 months, children begin following the rules for expressing tense and number and use words such as some, would, and who.

Reading and writing

At the same time as they are gaining listening and speaking skills, young children are learning about reading and writing.

At home and in child care, Head Start, or school, they listen to favorite stories and retell them on their own, play with alphabet blocks, point out the logo on a sign for a favorite restaurant, draw pictures, scribble and write letters and words, and watch as adults read and write for pleasure and to get jobs done.

Young children make numerous language discoveries as they play, explore, and interact with others. Language skills are primary avenues for cognitive development because they allow children to talk about their experiences and discoveries. Children learn the words used to describe concepts such as up and down, and words that let them talk about past and future events.

Many play experiences support children's emerging literacy skills. Sorting, matching, classifying, and sequencing materials such as beads, a box of buttons, or a set of colored cubes, contribute to children's emerging literacy skills. Rolling playdough and doing fingerplays help children strengthen and improve the coordination of the small muscles in their hands and fingers. They use these muscles to control writing tools such as crayons, markers, and brushes.

As their language skills grow, young children tell stories, identify printed words such as their names, write their names on paintings and creations, and incorporate writing in their make-believe play. After listening to a story, they talk about the people, feelings, places, things, and events in the book and compare them to their own experiences.

After listening to a story, they talk about the people, feelings, places, things, and events in the book and compare them to their own experiences.

Reading and writing skills develop together. Children learn about writing by seeing how the print in their homes, classrooms, and communities provides information. They watch and learn as adults write – to make a list, correspond with a friend, or do a crossword puzzle. They also learn from doing their own writing.

The chart below offers examples of activities preschool and kindergarten children engage in, and describes how they are related to reading and writing.

What children might do | How it relates to reading and writing |

|---|---|

| Make a pattern with objects such as buttons, beads, small colored cubes. | By putting things in a certain order, children gain an understanding of sequence.  This will help them discover that the letters in words must go in a certain order. This will help them discover that the letters in words must go in a certain order. |

| Listen to a story, then talk with their families, teachers, or tutors and each other about the plot, characters, what might happen next, and what they liked about the book. | Children enjoy read-aloud sessions. They learn that books can introduce people, places, and ideas and describe familiar experiences. Listening and talking helps children build their vocabularies. They have fun while learning basic literacy concepts such as: print is spoken words that are written down, print carries meaning, and we read from left to right, from the top to the bottom of a page, and from the front to the back of a book. |

| Play a matching game such as concentration or picture bingo. | Seeing that some things are exactly the same leads children to the understanding that the letters in words must be written in the same order every time to carry meaning. |

Move to music while following directions such as, put your hands up, down, in front, in back, to the left, to the right. Now wiggle all over. Now wiggle all over. | Children gain an understanding of concepts such as up/down, front/back, and left/right, and add these words to their vocabularies. Understanding these concepts leads to knowledge of how words are read and written on a page. |

| Recite rhyming poems introduced by a parent, teacher, or tutor, and make up new rhymes on their own. | Children become aware of phonemes – the smallest units of sounds that make up words. This awareness leads to reading and writing success. |

| Make signs for a pretend grocery store. | Children practice using print to provide information – in this case, the price of different foods. |

| Retell a favorite story to another child or a stuffed animal. | Children gain confidence in their ability to learn to read. They practice telling the story in the order it was read to them – from the beginning to the middle to the end. |

Use invented spelling to write a grocery list at the same time as a parent is writing his or her own list. | Children use writing to share information with others. By watching an adult write, they are introduced to the conventions of writing. Using invented spelling encourages phonemic awareness. |

| Sign their names (with a scribble, a drawing, some of the letters, or "correctly") on an attendance chart, painting, or letter. | Children are learning that their names represent them and that other words represent objects, emotions, actions, and so on. They see that writing serves a purpose to let their teacher know they have arrived, to show others their art work, or to tell someone who sent a letter. |

Becoming readers and writers

By the time most children leave the preschool years and enter kindergarten, they have learned a lot about language. For five years, they have watched, listened to, and interacted with adults and other children. They have played, explored, and made discoveries at home and in child development settings such as Head Start and child care.

Kindergarten

Beginning or during kindergarten, most children have naturally developed language skills and knowledge. They…

Know print carries meaning by:

- Turning pages in a storybook to find out what happens next

- "writing" (scribbling or using invented spelling) to communicate a message

- Using the language and voice of stories when narrating their stories

- Dictating stories

Know what written language looks like by:

- Recognizing that words are combinations of letters

- Identifying specific letters in unfamiliar words

- Writing with "mock" letters or writing that includes features of real letters

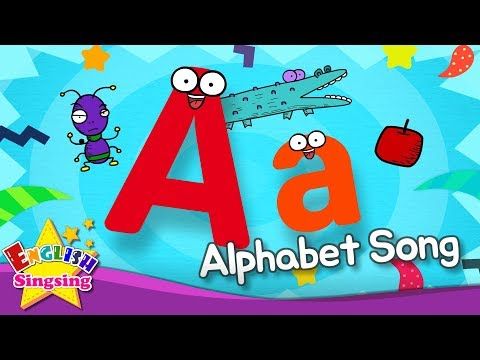

Can identify and name letters of the alphabet by:

- Saying the alphabet

- Pointing out letters of the alphabet in their own names and in written texts

Know that letters are associated with sounds by:

- Finger pointing while reading or being read to

- Spelling words phonetically, relating letters to the sounds they hear in the word

Know the sounds that letters make by:

- Naming all the objects in a room that begin with the same letter

- Pointing to words in a text that begin with the same letter

- Picking out words that rhyme

- Trying to sound out new or unfamiliar words while reading out loud

- Representing words in writing by their first sound (e.

g., writing d to represent the word dog)

g., writing d to represent the word dog)

Know using words can serve various purposes by:

- Pointing to signs for specific places, such as a play area, a restaurant, or a store

- Writing for different purposes, such as writing a (pretend) grocery list, writing a thank-you letter, or writing a menu for play

Know how books work by:

- Holding the book right side up

- Turning pages one at a time

- Reading from left to right and top to bottom

- Beginning reading at the front and moving sequentially to the back

Because children have been learning language since birth, most are ready to move to the next step – mastering conventional reading and writing. To become effective readers and writers children need to:

- Recognize the written symbols letters and words used in reading and writing

- Write letters and form words by following conventional rules

- Use routine skills and thinking and reasoning abilities to create meaning while reading and writing

The written symbols we use to read and write are the 26 upper and lower case letters of the alphabet. The conventional rules governing how to write letters and form words include writing letters so they face in the correct direction, using upper and lower case versions, spelling words correctly, and putting spaces between words.

The conventional rules governing how to write letters and form words include writing letters so they face in the correct direction, using upper and lower case versions, spelling words correctly, and putting spaces between words.

Routine skills refer to the things readers do automatically, without stopping to think about what to do. We pause when we see a comma or period, recognize high-frequency sight words, and use what we already know to understand what we read. One of the critical routine skills is phonemic awareness – the ability to associate specific sounds with specific letters and letter combinations.

Research has shown that phonemic awareness is the best predictor of early reading skills. Phonemes, the smallest units of sounds, form syllables, and words are made up of syllables. Children who understand that spoken language is made up of discrete sounds – phonemes and syllables – find it easier to learn to read.

Many children develop phonemic awareness naturally, over time. Simple activities such as frequent readings of familiar and favorite stories, poems, and rhymes can help children develop phonemic awareness. Other children may need to take part in activities designed to build this basic skill.

Simple activities such as frequent readings of familiar and favorite stories, poems, and rhymes can help children develop phonemic awareness. Other children may need to take part in activities designed to build this basic skill.

Thinking and reasoning abilities help children figure out how to read and write unfamiliar words. A child might use the meaning of a previous word or phrase, look at a familiar prefix or suffix, or recall how to pronounce a letter combination that appeared in another word.

First and second grades

By the time most children have completed the first and second grades, they have naturally developed the following language skills and knowledge. They…

Improve their comprehension while reading a variety of simple texts by:

- Thinking about what they already know

- Creating and changing mental pictures

- Making, confirming, and revising predictions

- Rereading when confused

Apply word-analysis skills while reading by:

- Using phonics and simple context clues to figure out unknown words

- Using word parts (e.

g., root words, prefixes, suffixes, similar words) to figure out unfamiliar words

g., root words, prefixes, suffixes, similar words) to figure out unfamiliar words

Understand elements of literature (e.g., author, main character, setting) by:

- Coming to a conclusion about events, characters, and settings in stories

- Comparing settings, characters, and events in different stories

- Explaining reasons for characters acting the way they do in stories

Understand the characteristics of various simple genres (e.g., fables, realistic fiction, folk tales, poetry, and humorous stories) by:

- Explaining the differences among simple genres

- Writing stories that contain the characteristics of a selected genre

Use correct and appropriate conventions of language when responding to written text by:

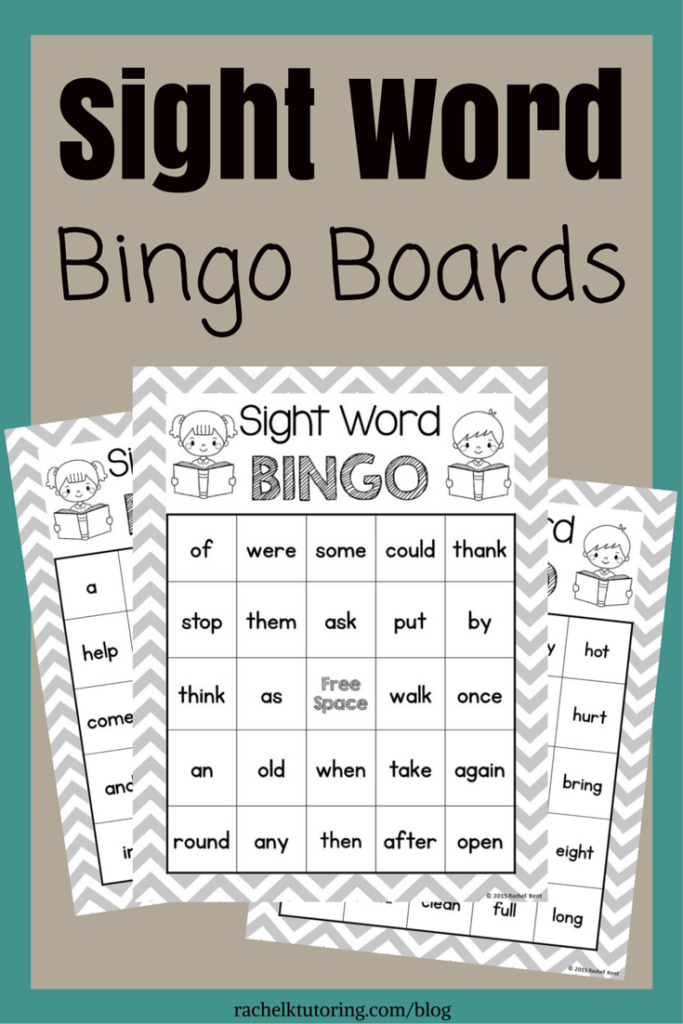

- Spelling common high-frequency words correctly

- Using capital letters, commas, and end punctuation correctly

- Writing legibly in print and/or cursive

- Using appropriate and varied word choice

- Using complete sentences

The chart below offers examples of activities children engage in and describes how they are related to reading and writing.

What children might do | How it relates to reading and writing |

|---|---|

| Discuss the rules for an upcoming field trip, watch their teacher write them on a large sheet of paper, and join in when she reads the rules aloud. | Children experience first-hand how different forms of language – listening, speaking, reading, and writing – are connected. They see language used for a purpose, in this case to prepare for their field trip. They see their words written down and hear them read aloud. |

| Look in a book to find the answer to a question. | Children know that print provides information. They use books as a resource to learn about the world. |

| Read and reread a book independently for several days after the teacher reads it aloud to the class. | Children read and reread the book because it's fun and rewarding. They can recall some of the words the teacher reads aloud and figure out others because they remember the sequence and meaning of the story. They can recall some of the words the teacher reads aloud and figure out others because they remember the sequence and meaning of the story. |

| Read some words easily without stopping to decode them. | Children gradually build a sight vocabulary that includes a majority of the words used most often in the English language. They can read these words automatically. |

| Read words they have never seen before. | Children use what they already know about letter combinations, root words, prefixes, suffixes, and clues in the pictures or story to figure out new words. |

| Use new words while talking and writing. | Children build their vocabularies by reading and talking, sharing ideas, discussing a question, listening to others talk, and exploring their interests. Using new words helps them fully understand the meaning of the words. |

Recognize their own spelling mistakes and ask for help to make corrections. | Children understand that spelling is not just matching sounds with letters. They are learning the basic rules that govern spelling and the exceptions to the rules. |

| Ask questions about what they read. | Children understand that there is more to reading than pronouncing words correctly. They may ask questions to clarify what they have read or to learn more about the topic. |

| Choose to read during free time at home, at school, and in out-of-school programs. | Children learn to enjoy reading independently, particularly when they can read books of their own choosing. The more children read, the better readers they become. |

Key points about development

- Children develop in four, interrelated areas – cognitive and language, physical, social, and emotional.

- Most children follow the same sequence and pattern for development, but do so at their own pace.

- Language skills are closely tied to and affected by cognitive, social, and emotional development.

- Children first learn to listen and speak, then use these and other skills to learn to read and write.

- Children's experiences and interactions in the early years are critical to their brain development and overall learning.

- Emerging literacy is the gradual, ongoing process of learning to understand and use language.

- Children make numerous language discoveries as they play, explore, and interact with others.

- Children build on their language discoveries to become conventional readers and writers.

- Effective readers and writers recognize letters and words, follow writing rules, and create meaning from text.

- Successful programs to promote children's reading and literacy development should be based on an understanding of child development, recent research on brain development, and the natural ongoing process through which most young children acquire language skills and become readers and writers.

methods of teaching reading to the first grade

When to teach a child to read

There are early development studios where children are taught to read from the first years of life. However, pediatricians do not recommend rushing and advise starting learning to read no earlier than 4 years old, best of all - at 5–6. By this age, most children already distinguish sounds well, can correctly compose sentences and pronounce words. Therefore, most often parents think about how to teach their child to read, already on the eve of school.

However, pediatricians do not recommend rushing and advise starting learning to read no earlier than 4 years old, best of all - at 5–6. By this age, most children already distinguish sounds well, can correctly compose sentences and pronounce words. Therefore, most often parents think about how to teach their child to read, already on the eve of school.

How to know if your child is ready to learn to read

Before you start teaching your child to read, you need to make sure that the child is ready and wants to learn. To do this, try to answer the following questions:

- Does the child know the concepts of “right-left”, “big-small”, “inside-outside”?

- Can he generalize objects according to these characteristics?

- Can he distinguish between similar and dissimilar forms?

- Is he able to remember and execute at least three instructions?

- Does he form phrases correctly?

- Does he pronounce words clearly?

- Can he retell a story he heard or experienced?

- Can he formulate his feelings and impressions?

- Can you predict the ending of a simple story?

- Does he manage to participate in the dialogue?

- Can he listen without interrupting?

- Can he rhyme words?

- Do the letters attract his attention?

- Does the child have a desire to independently look at the book?

- Does he like being read aloud to him?

If you answered “yes” to these questions, your child is ready and will soon learn to read correctly.

Methods for teaching reading

Most of the methods involve learning while playing, so that the child is not bored and learns knowledge better.

<

Zaitsev's Cubes

For more than twenty years, these cubes have been introducing children to letters and teaching how to form words and syllables. They allow you to understand how vowels and consonants, deaf and voiced sounds differ. There are 52 cubes in total, each of which depicts warehouses (combinations of a consonant and a vowel). The cubes vary in color and size, the large ones depict hard warehouses, while the small ones are soft. During classes, parents are encouraged to pronounce or sing warehouses so that the child remembers them better.

K Zaitsev's ubikiSource: moya-lyalyas.ru

Vyacheslav Voskobovich's "towers" and "folds"

windows. You can put cubes in them to make syllables. And from several towers you can make a word.

Voskobovich's "towers"Source: catalog-chess.

ru

ru Skladushki is a book with pictures, educational rhymes and songs. Parents sing them and in parallel show the warehouses in the pictures. The author of the methodology claims that a child of six years old can be taught to read in a month using "folds".

A page from V. Voskobovich's "folds"

Doman's cards

This method of teaching a child to read is based on memorizing whole words, from simple to more complex. First, the child masters the first 15 cards, which the parent shows him for 1-2 seconds and pronounces the words on them. Then the child tries to memorize phrases. This technique helps not only to learn more words, but also develops memory well in general.

Doman cardsSource: friendly-life.ru/kartochki-domana-dlya-samyh-malenkih

Maria Montessori's method of teaching reading

The essence of the Montessori method is that the child is first asked to feel the writing of a letter, and then pronounce it. For this, didactic materials are used - cardboard plates with pasted letters, the outline of which the child traces with his finger, naming the sound. After studying consonants and vowels, you can move on to words and phrases. The Montessori method not only helps to learn to read, but also develops fine motor skills, logic, and the ability to analyze.

For this, didactic materials are used - cardboard plates with pasted letters, the outline of which the child traces with his finger, naming the sound. After studying consonants and vowels, you can move on to words and phrases. The Montessori method not only helps to learn to read, but also develops fine motor skills, logic, and the ability to analyze.

Source: hendmeid.guru

Olga Soboleva's technique

The author of this technique believes that you need to start learning not from the abstract alphabet, but immediately in practice - by analyzing simple texts. The Soboleva program allows you to teach a child to read from the age of five - at this age, children are already able to keep their attention on a line of text. Different approaches are offered depending on how it is easier for a child to perceive the world - by eye, by ear or by touch. In addition to reading skills, the technique develops interest in creativity, imagination, attention and memory.

How to teach a child to read by syllables

Teaching a child to read by syllables should be done in stages. First, explain to him that sounds are vowels and consonants, deaf and voiced. Say them with the child - he must understand how they differ. Letters and sounds can be learned while walking: draw your child's attention to the letters on signs and announcements, and soon he will learn to recognize them.

When the child has mastered the letters and sounds, start teaching him to read simple words - "mom", "dad". Then move on to more complex ones - “grandmother”, “dog”, “apartment”. Show your child that syllables can be sung.

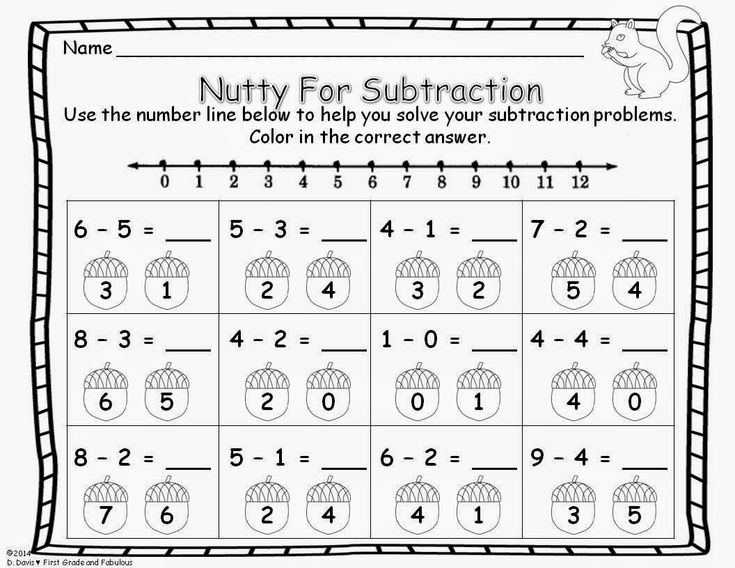

Syllabary for learning to read

Next, move on to word formation. You can cut cards with syllables and invite the child to make words out of them. When he gets comfortable, move on to reading short texts. It is better to start with two or three phrases, and a little later switch to texts of five to ten sentences.

To enroll in Foxford Online Elementary School, a child must have at least basic reading, numeracy and writing skills. To check the readiness of the child for school, we offer to pass a small test that does not require special preparation.

Source: freepik.com

Exercises for learning to read

There are many exercises on the Internet that help children learn to read, you can print them out and start learning right away. Start with exercises that teach you to recognize letters and tell correct spellings from incorrect spellings.

From O. Zhukova's manual “Learning to read. Simple Exercises.Source: mishka-knizhka.ru

When the child gets used to the letters, move on to the exercises for syllables. For example, like this:

Geometric hint exercise. For greater clarity, blocks with words can be cut out.

Such exercises not only teach reading, but also develop logical thinking well:

Gradually move on to exercises where you need not only to read correctly, but also write words:

One of the most difficult and entertaining exercises is fillords: you need to find and cross out the words on the field of letters.

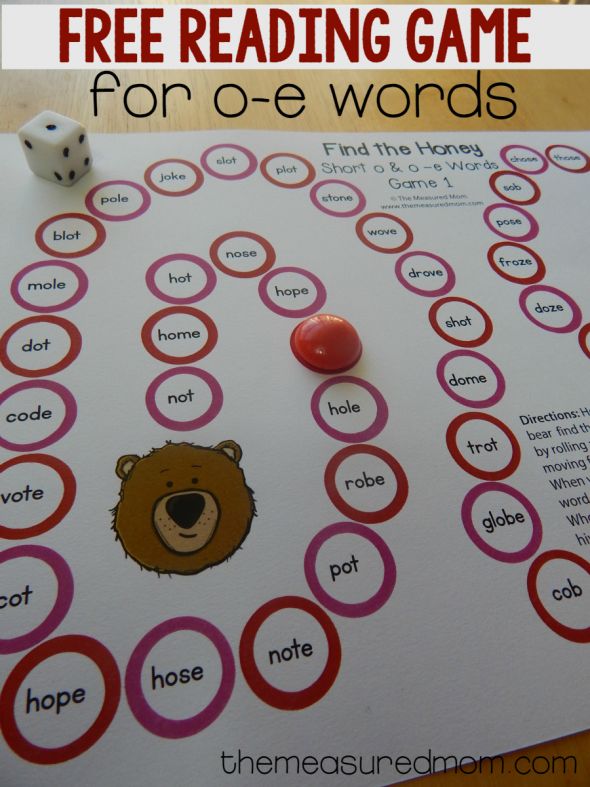

Games for learning to read

With the help of cubes or cards with letters and syllables, you can play different educational games with your child. Let's take a few examples.

Garages

Take a word of 3-4 syllables and place the cards in random order on the floor. Explain to the child how these syllables are read. These will be garages. Give the child different toys and offer to send them to the garage as you wish: for example, the car goes to the TA garage, the bear goes to the RA garage, the ball rolls to the KE garage, and so on. Make sure your child is positioning the toys correctly. At the end of the game, invite the child to make a word from garage syllables. Perhaps not the first time, but he will get a "ROCKET". Gradually introduce new syllables into the game.

<

Store

Lay out images of various goods on the table - this is a store, and you are a seller. Give your child a stack of cards with syllables - they will function as money. The child needs to buy all the items in the store, but each item is only sold for the syllable it starts with. For example, fish can only be bought for the syllable "RY", milk - for the syllable "MO", and so on. Give your child a few extra cards to make the task more difficult. When he gets used to it, change the conditions of the game: for example, sell goods not for the first, but for the last syllables. The game is both simple and complex: it will allow the child to understand that words are not always spelled the way they are pronounced. After all, a cow cannot be bought for the syllable "KA", for example.

The child needs to buy all the items in the store, but each item is only sold for the syllable it starts with. For example, fish can only be bought for the syllable "RY", milk - for the syllable "MO", and so on. Give your child a few extra cards to make the task more difficult. When he gets used to it, change the conditions of the game: for example, sell goods not for the first, but for the last syllables. The game is both simple and complex: it will allow the child to understand that words are not always spelled the way they are pronounced. After all, a cow cannot be bought for the syllable "KA", for example.

Lotto

Game for several people. Give the children several cards with syllables. Take out the cubes with syllables one by one from the box and announce them. Whoever has a card with such a syllable - he takes it. The first person to complete all the cards wins. During the game, children will accurately remember the syllables that they had on their hands.

Summary

Finally, a few more tips on how to teach a child to read:

- It is better to start teaching children to read by memorizing letters.

It is important that the child can recognize and name them without hesitation.

- In the early stages, pronounce the consonants as they are read in words: not [em], [el], [de], but [m], [l], [d] - this way it will be easier for the child to find his bearings.

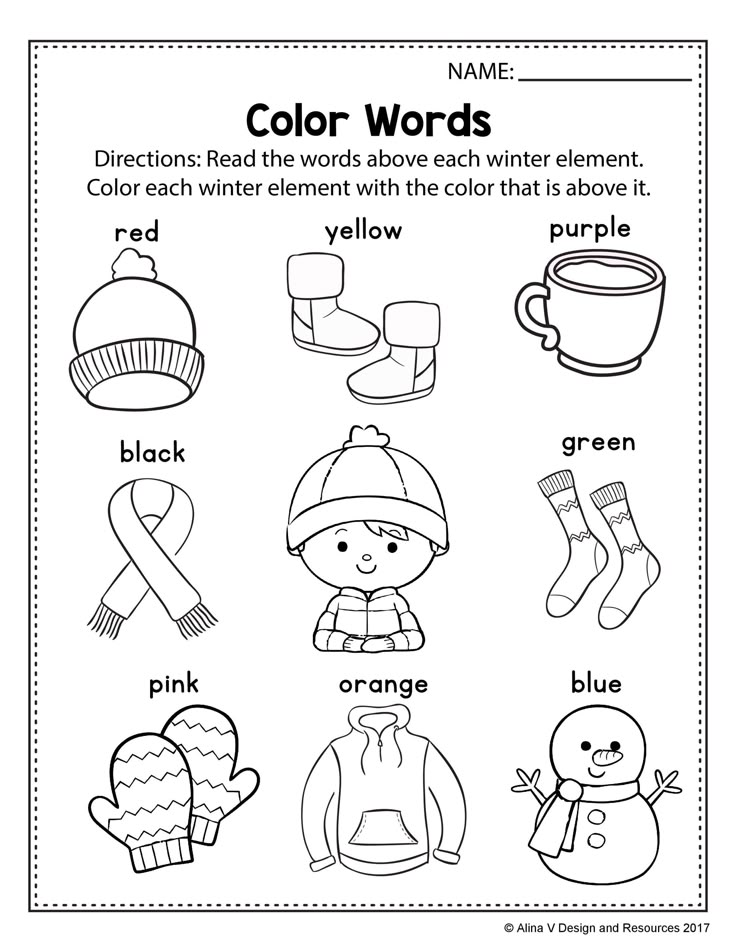

- Sculpt letters from plasticine, draw and color, buy an alphabet with voice acting - use all the channels of the child's perception.

- Gradually build letters into syllables and then into words. Play rearranging letters and syllables, let the child experiment.

- Teach your child rhymes about the letters of the alphabet, look at the primer, use cards with letters and pictures. Thanks to the illustrations, the child will be able to memorize the symbols faster.

- Distribute the load: fifteen minutes a day is better than an hour twice a week. Alternate entertaining and serious tasks.

- You can hang signs with their names on objects in the child's room - the child will quickly learn to recognize them in texts.

- Read aloud regularly to your child and gradually introduce them to independent reading. Every evening, offer to read at least a few lines from a well-known book on your own.

- Lead by example. For a child to want to learn to read, he must regularly see you with a book.

We hope that our recommendations will help you teach your preschooler to read. Even if your child is just learning to read, at Foxford Elementary School he will be able to improve his skills.

Children learn to read independently - "Freedom in Education". Home schooling and unschooling in Russia and around the world

Freedom in education implies not only (and maybe not so much) freedom of action, but also freedom of inaction. Home education gives such freedom not only to children, but also to parents. For example, you can abandon primers and not teach children to read - let them learn on their own! Dodging slippers flying in my direction and something worse, I still dare to recommend to your attention an article by Peter Gray with true stories about how unschoolers learn to read at home , outside of any methods - and, characteristically, with minimal participation from side of the parents.

Unschoolers' stories about how their children learned to read.

Author: Peter Gray

Translation: Elena Moshkova

specially for the Freedom in Education project

Posted February 24, 2010 in Freedom to Learn

In our culture, children should be taught to read. There is a lot of research on how it is better to do this from a scientific point of view. In the library of any pedagogical university there are several rows of books and a bunch of magazines devoted to a single topic: how to teach reading correctly. For decades there has been a bitter debate in educational circles - sometimes even called "reading wars" - between advocates of learning with a primary focus on phonetics of the language and those who adhere to the principles of teaching "language as a whole". In an attempt to compare the effectiveness of one technique with another, a lot of scientific experiments were carried out, with kindergarten students or primary school students as guinea pigs. Proponents of the phonetic approach say that their methods have proven to be more effective, while their competitors believe that the results have been manipulated.

General education schools complain that reading is difficult for children. Much of the time spent in kindergarten and elementary school is dedicated to teaching children to read. In addition to this, the education system encourages parents to teach their children to read at home so that they can then read school instructions or explanations for them. An entire industry has grown out of the development, printing, and distribution of reading instructions. There is no end to interactive computer applications, video tutorials, and purpose-built books—scientifically optimal, their creators claim—that teach letters, sounds, and provide an endless database of simple words for beginning readers.

I recently read an article by two cognitive scientists who argue that the next step in the development of methods for teaching reading will be individual instructions [1]. According to the authors of the article, modern methods of studying mental activity will be used to determine a unique learning method for each child, and based on this data, a digital program will be able to compose texts and teach children to read according to their individual characteristics. The authors and their colleagues are actually working on creating such systems. This seems stupid to me. The unique needs of each child that affect learning are embedded not only in the features of the functioning of their brain, but in the daily, every second individual experience of each child, his or her desires and whims, which are subject only to himself or herself. I will believe these scientists only when they prove that their ways of studying the brain can predict in advance the content of any dream.

In stark contrast to all the fuss about learning to read stands out the opinion of people involved in the practice of unschooling (home education), or associated with the "anti-school" school in Sudbury. They say that you don't need to learn to read at all!

Children who grow up in a literate society, surrounded by people who can read, gradually learn themselves. They may ask questions along the way and receive some prompting from those who can already read, but the initiative in the learning process will come from the children themselves, and they themselves will figure out how best to organize it.

This is individual learning, but it does not require any brain research or cognitive scientists, nor much effort on the part of anyone other than the child who is learning to read. Each child knows exactly what his or her individual learning style is, knows exactly what they are ready for at the moment, and therefore learns to read in their own unique way, on their own individual schedule.

D

21 years ago, my graduates conducted a study on how students learn to read at Sudbury Valley School, where they are completely free and do whatever they want all day (I wrote about this in my article about this school) [2] . They found sixteen students in Sudbury who had learned to read at school without any systematic instruction on the subject, and then interviewed themselves, their parents, and school staff to understand when, why, and how exactly each of the children learned to read.

The results of this study did not lend themselves to the slightest generalization. The age at which children began to read fluctuated in a very wide range - from 4 to 14 years. Some students learned to read very quickly, taking several weeks to go from complete inability to fluent reading, while others learned much more slowly.

Several people worked on reading consciously, constantly studying the sounds and asking others for advice. Others simply "grabbed on the fly." The latter simply realized one day that they can read - and have no idea how this happened. There was no relationship between the age at which students started reading and how engaged they were in reading at the time of the survey. Some active and voracious readers learned to read early, others quite late.

My son, who works at Sudbury Valley School, says the study is outdated. In his impression, most school students today learn to read at an early age, making even less conscious effort than before, because they are immersed in a cultural environment where people constantly communicate, and often through text: in computer games, via electronic mail, social networks, SMS messages, etc. For today's children, the written word is not much different from the spoken word, and therefore the biological mechanisms that each of us have for learning oral speech are more or less automatically connected to the process of learning to read or write (print).

I'd love to learn this process in some way, but I don't see how I can do it without interfering with the learning itself.

A few weeks ago (see the January 6, 2010 post) I invited readers of my blog whose children are homeschooled or in non-standard schools such as the one in Sudbury to send me stories of how children learned to read without a formal learning to read. Eighteen people, most of whom introduced themselves as unschoolers' parents, responded and shared their experiences. Each story is unique. And just like my students in the study at Sudbury Valley, I can't point out any regularities in the process of teaching reading to children who do not attend school.

And yet, by listing and comparing the main points in each story, I have identified what I think can be called seven basic principles that can shed some light on the process of learning to read outside of school. The rest of this article is just written around these principles, each of which is backed up by quotations from a particular submitted story. Since some of the letter writers have requested that I not name their children or parents, I will apply this principle to everyone.

Seven principles of learning to read outside of school

In a general education school, it is very important that the child learn to read according to the schedule, within the time frame dictated by the program. If you fall behind, you can no longer catch up with the rest, you will be considered "underachieving", or left for the second year, or even considered mentally retarded. In the general education system, reading is the key to all other knowledge. First you learn to read, then you learn to learn. If you cannot read, you cannot understand anything in the rest of the program, because most of the learning materials are text. There is even evidence that students who fail to learn to read on time end up exhibiting bad behavior at school. One long-term study in Finland found that poor reading in kindergarten contributed to reading delays in later elementary school, as well as "problem behavior in the classroom", which primarily means unsanctioned speeches. [3]

The situation is quite different for children outside of school. They can learn to read at any moment, without any negative consequences. One of the readers of this blog sent me a whole bunch of stories of learning to read, where the age of coherent reading for twenty-one children was mentioned (reading and understanding of a coherent fictional text is implied). Among them were two examples of 4-year-olds, seven aged 5 to 6, six aged 7 to 8, five started reading at 9-10 years old, and one at 11 years old.

Even within the same family, children learned to read at different ages . Diana writes that the eldest daughter learned to read at the age of five, and the youngest at nine; Lisa W. reported that one son started reading at 4 and the other at 7; Beatrice writes that one daughter was not yet five, and the second began to read at eight.

None of these children have reading problems now. Beatrice wrote that the daughter who started reading at 8, now at 14 reads hundreds of books every year, wrote a novel and won several prizes in poetry competitions. However, do not think that late learning to read somehow stimulates literary talents! The passion for literature was noticeable in this girl long before she learned to read. Her mother writes that she could recite all the verses from Complete Mother Goose from memory when she was only a year and three.

P

Note: You can read about it for yourself on Beatrice Ekwa Ekoko's excellent blog

The most common thought in all of the submissions about learning to read is that children learned to read because no one forced them to, they had positive attitude towards reading and learning in general. Perhaps Jenny put it best when she wrote about her daughter, who is now 15 and did not read well until she was 11: experience to gain confidence that since she learned to read, she can learn everything. We never forced her to learn anything, and for that reason her curiosity didn't suffer. She is smart, curious, very passionate about everything that happens around.

In some cases, the transition from complete inability to read to confident reading seems to be instantaneous from the outside. For example, Lisa W. writes: “Our second child, a visually expressive child, could not read until he was seven years old. Prior to that, for several years, he either figured out everything he needed from the pictures, or turned to his older brother for help. I remember the day he started reading. He asked his older brother to read something to him on the monitor screen, and he replied: “I have more important things to do than read to you all day,” and the younger one left. confident.”

Diana writes: “In March, my eldest daughter turned five, and she still could not read, and by the end of that year she was already reading aloud fluently, without pauses or hesitations.” And Kate wrote that her son at the age of nine "learned to read on his own" in about a month. At this time, he constantly worked on his reading technique, on his own, and went from timid attempts and errors to fast and fluent reading, reaching a level much higher than that provided for by the school curriculum for his age.

Such breakthroughs in learning to read may occur, at least in part, because they are preceded by periods of covert learning, invisible to others, and sometimes to the students themselves. Karen attributes her son's rapid reading development to a sudden leap in his mind. She writes: “Over the last summer, son A (he is seven years old) has gone from hiding his ability to read to reading entire chapters of a book. In one summer! Now, six months later, he feels confident with books, and I often find him reading aloud to his younger sister in the morning. He even offers to read aloud to my father and to me. This is so unexpected, compared to last year, when he hid that he could read and was not at all confident in his skill. I'm glad we didn't push him!"

Three of the people who wrote to me told me that at some point they wanted to teach their children to read - and that those efforts seemed to backfire. Here's what they say.

Holy writes that her son was about three and a half years old when she decided to teach him to read. “It seems to me that the Bob Books series is too simple, even stupid, there are a lot of repetitions, but I chose some of them that were more interesting and tried to start learning with a child. ... He was really not yet ready, it seems to me, for real reading, but one way or another, the son objected to everything that happened not on his initiative, so he balked. ... I quickly realized that instead of success in learning to read, I would only get harm to my child, because he began to hate reading. I immediately stopped all attempts to teach and only read to the child every time he asked for it. Holy writes further that about two years later, his son "quite unexpectedly" began to pick up books on his own initiative and read a little, partially hiding his interest and continuing to train, since no one pressed him.

Beatrice writes about her daughter, who learned to read at age eight: “It’s my fault too, I tried to get my daughter to read when she was six, because I was worried that she would fall behind the children who study in school. After a couple of weeks of me persistently trying to get her to read and keeping a journal where I wrote the words and she copied them, the daughter indifferently told me to "leave her alone", that she would not take part in all this and would learn to read when "she was in the mood and ready. "

Finally, Kate, a mother from the UK, who teaches children at home, wrote the following about her attempts to teach her son to read: “Until the age of nine, he protested against any language lessons, and reading led to regular skirmishes. He resisted, considered it all boring, got upset, and, in the end, I stepped over my own pedagogy and tried a new method: let it go as it goes. I said that I would never again force him to read and even offer him ... Over the next month, he quietly and calmly, shutting himself in his room ... learned to read on his own. I spent four years teaching him the basics [when he had no interest], and now I'm sure he could master them in a couple of weeks."

There is an old joke - I first heard it about twenty years ago - about a child who did not speak until he was five years old. And then, one day at dinner, he suddenly said: “The soup is not salty!” Mom, almost fainting, exclaimed: “Son, you can talk like that! Why have you been silent until now?!” “Before that, everything was fine,” the boy replied.

This story is completely absurd from the point of view of teaching speech, and therefore is perceived as a joke. Children learn to speak, regardless of whether they need it for some applied purposes or not - they are genetically programmed for speech communication. But if you change this anecdote a little, it will become very plausible in terms of learning to read. Children learn to read on their own when they find a good reason to do so. This idea is supported by many stories. Here are just a few of them.

Amanda writes of her daughter attending a non-standard school modeled after Sudbury: “She kept telling everyone she couldn’t read until she baked a chocolate bar one November [at age seven]. cookie. At first she asked her father and me to bake her favorite cookies, but neither he nor I wanted to mess with it. After a while, she ran into the room and asked if I could turn on the oven for her and give her a "nine-ha-eleven" pan (she said "ha" instead of "9at 11"). I got her a baking sheet and turned on the oven. Later, she came running and asked for help putting the cookies in the oven. And then she said: "Mom, I think I learned to read." She immediately brought some books and read aloud to me until she jumped: “It smells like cookies are baked. Can you help me get them out?" ... Now she tells everyone that she can read and that she learned it herself.”

Iji, a 19-year-old female blogger, out of school, highly educated, sent me a link to a post on her personal blog with memories of learning to read. She, in particular, writes: “When I was 8-9 years oldMom was reading the first Harry Potter book out loud to my sister and me. But, of course, she had something to do besides reading, and besides, her voice would get worse if she read for a long time. And so, frustrated by the fact that the reading was going so slowly, impatiently to find out what would happen next, I picked up the book and began to read it myself.

Marie, mother of unschoolers, writes about her seven-year-old son: “[For him] the biggest incentive to learn to read well was playing in the local theater. He always liked to put on some kind of "performance", and now he is old enough to participate in real performances. He realized that reading is an integral part of the process, and therefore fell in love with this activity and received a powerful incentive to improve the skill. Recently he was given a role in the play "A Midsummer Night's Dream" - and he had to read and memorize Shakespeare. He never once needed "teacher's" instructions for this.

Jenny writes about her daughter, who didn't read until she was nine, because her mother's need for fairy tales was satisfied by her mother's reading aloud, movies, and audiobooks they borrowed from the library. She started reading because video games like ToonTown required it, and manga comics that no one wanted to read to her.

-

Reading, like many other skills, is acquired in communication, through joint participation in the process.

Observations of pupils at Sudbury Valley School and other schools that follow this model have shown that many children learn to read through games involving children of different ages. Reading and non-reading children play games together, including computer games, where text comes across. To continue the game, children who read read aloud the words, while children who do not read memorize them.

Vincent Lopez of Sudbury's Diablo Valley School sent this delightful example of mixed-age learning: “In the art room, kids make signs to play the TV show that has just started. In my opinion, this is a stupid, low ethical, populist show about free dating for everyone; I said this before. But they bring the future closer in their own way ... yes, I digress. The culmination of this whole process was an attempt by a five-year-old to read one of the tablets with the help of comrades of different ages ... The guys study because they want to understand jokes, to be smarter, like their older playmates.

Almost all stories of learning to read from parents of unschoolers contain episodes of shared reading. One of my favorite examples is story by Diana , who wrote that her daughter started reading at the age of five because she became interested in reading through regular family Bible readings. Before she could read, she insisted that she would also read in turn, “and just started making words when it was her turn!”

Others write about family games together using words or watching TV together using teletext read aloud by those who can read. At one point, non-reading children begin to need much less help: they begin to recognize words and read new words on their own. The most common example is shared reading, when parents, and sometimes older brothers or sisters, read to younger ones who cannot read - usually at night, before going to bed. Those who cannot read look at the words and at the pictures, sometimes they read individual words; in other cases, they memorize books that have been read to them many times, and then pretend to read, although they understand only individual words. The game of reading gradually turns into real reading.

In my previous articles, I referred to the outstanding Russian teacher and psychologist Lev Vygotsky, whose main idea in his works was that children first learn skills in a team, using the example of other, more developed comrades, and only then begin to reproduce these skills individually , for your purposes. This general principle applies very well to reading.

At least seven people who submitted their stories say their children became interested in writing—or typing—before or at the same time as they became interested in reading. Here are some examples.

Marie writes about her son, who is now 7 years old: “He is an artist and spends hours drawing stories and his inventions. Naturally, he wanted his paintings to “speak” with the help of direct speech, titles, explanations and quotations. ... There was a constant: “Maaam! How to write Superdog wants to come home?" I wrote a sentence, and after five minutes it began: "Maaam! How to write Superdog sees his home?" This boy learned to read in part by reading sentences he wrote.0005

Beatrice told a similar story about her youngest daughter, who started reading when she was less than five years old. “She learned to read because she really wanted to express her emotions and thoughts in writing. From the moment she learned to hold a pencil in her hands, she constantly tried to write poetry, songs, composed advertising slogans, and all the time I had to tell her how to write the words: “How to spell a beaver, how to spell an offer ?!”

Lisa R. spoke of her son, who is currently learning to read: “His reading skills involve trying to write. ...He composed short notes and headlines for fairy tales using his own phonetic script. Sometimes he asked how to write this or that word correctly. After some repetitions, the boy remembers the words.

Lisa W . wrote: "The eldest son learned to read at the age of 4 years. It was a by-product of trying to type at the computer in search of free online games. He opened the browser and asked me to tell you how to spell "free", "online", "games". And then all of a sudden he was able to read.”

I don't want you to get the impression after reading this article that I or the people who shared their experience have taught you something useful in the field of "how to help" or "how to teach" a child to read. No, no and NO. Every child is unique. Your child will tell him how to help him - or how not to interfere. I don't have the slightest idea how to do this, and neither do the so-called "expert educators." My only advice is: do not push, listen to your child, adequately answer his questions, but do not say in response more than he wanted to know. If you overdo it, the child will quickly learn not to ask questions.

Few of the writers expressed surprise at the order in which their children learned to read. Some first learned to read rare, exotic words, and only then simple ones. Some first learned to write, as I said, and then to read. Some learned pretty quickly, and then stopped at a certain level for several years, and only then there was further progress. We, adults, can enjoy watching the process, if we remember that it is not our task to interfere in it. We are observers and sometimes tools that our children use to achieve their own goals.

I

I am very grateful to those people who took the time to share their stories with me, writing them down so thoughtfully and in detail. I hope that many of you, after reading the article, will add your own stories to these stories in the comments. I think it's time to post a bunch of real stories about how each unschooler learns to read according to his own, special methodology, as opposed to the pile of books on teaching reading that are in the libraries of pedagogical universities.

And I can't help but tell a little story at the end of this article about how my son learned to read. He began to read very early, and one of his first successful attempts came at the age of three and a half, when we were together looking at a Civil War monument in a town square somewhere in New England. He looked at the inscription and asked me: "Why did people fight and die to save the bow [4]?"

----------

References

[1] D. Rose & B. Dalton (2009), Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain, and Education, 3, 74-83.

[2] R. M. Savio (1989), Self-initiative in the learning process; and A.