Click clack moo cows that type story pdf

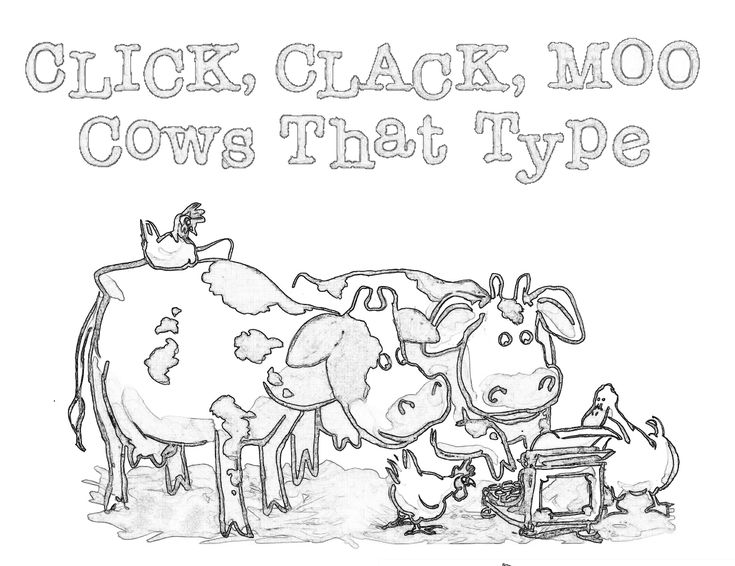

Click Clack Moo: Cows That Type

None Read along about when the cows unite to improve their working conditions. Click, clack, moo! Click, clack, moo! Clickety, clack, moo! Farmer Brown can’t believe his ears. “Cows that type?” he says. Then he sees what they’re typing—their demands! It gets cold in the barn at night so they want electric blankets! Farmer Brown refuses to meet their demands and receives another note. The cows go on strike—no milk! Cows refusing to give milk? They’re cows! Farmer Brown still refuses and gets ANOTHER typed note. Now the hens are getting involved. Read along to this amusing story about a farmer in a demanding situation. Who do you agree with? Why? show full description Show Short DescriptionAnimals

Enjoy fun, animal stories for kids including bedtime favorites like Is Your Mama a Llama and Piggies in the Pumpkin Patch.

view all

Is Your Mama a Llama?

All About Kangaroos

Aggie and Ben: The Surprise

Aggie and Ben: Just Like Aggie

Aggie and Ben: The Scary Thing

Aggie the Brave: Get Well Soon

Aggie the Brave: A Visit to the Vet

Aggie the Brave: The Long Day

Good Dog, Aggie: Aggie At School

Good Dog, Aggie: Aggie in Training

Mechanimals

Click Clack Moo: Cows That Type

Who Am I? Wild Animals

Sweet Tweets: Five Little Ducks

Piggies in the Pumpkin Patch

One membership, two learning apps for ages 2-8.

TRY IT FOR FREE

Full Text

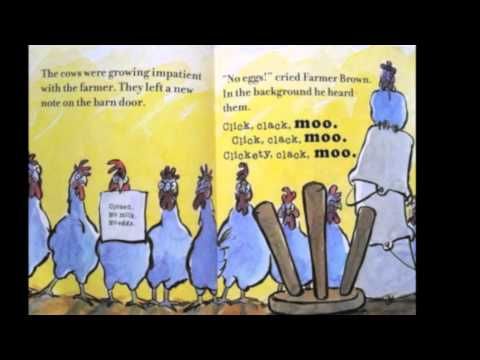

Farmer Brown has a problem. His cows like to type. All day long he hears Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. At first, he couldn’t believe his ears. Cows that type? Impossible! Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. Then, he couldn’t believe his eyes. \t“Dear Farmer Brown, \tThe barn is very cold at night. \tWe’d like some electric blankets. \tSincerely, \tThe Cows” It was bad enough the cows had found the old typewriter in the barn. Now they wanted electric blankets! “No way,” said Farmer Brown. “No electric blankets.” So the cows went on strike. They left a note on the barn door: \t“Sorry. \tWe’re closed. \tNo milk today.” “No milk today!” cried Farmer Brown. In the background, he heard the cows busy at work: Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. The next day, he got another note: “Dear Farmer Brown, The hens are cold too. They’d like electric blankets. Sincerely, The Cows” The cows were growing impatient with the farmer. They left a new note on the barn door: “Closed. No Milk. No Eggs.” “No eggs!” cried Farmer Brown. In the background he heard them. Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. “Cows that type. Hens on strike! Whoever heard of such a thing? How can I run a farm with no milk and no eggs?” Farmer Brown was furious. Farmer Brown got out his own typewriter. “Dear Cows and Hens: There will be no electric blankets. You are cows and hens. I demand milk and eggs. Sincerely, Farmer Brown” Duck was a neutral party, so he brought the ultimatum to the cows. The cows held an emergency meeting. All the animals gathered around the barn to snoop, but none of them could understand Moo. All night long, Farmer Brown waited for an answer. Duck knocked on the door early the next morning. He handed Farmer Brown a note: “Dear Farmer Brown, We will exchange our typewriter for electric blankets.

They’d like electric blankets. Sincerely, The Cows” The cows were growing impatient with the farmer. They left a new note on the barn door: “Closed. No Milk. No Eggs.” “No eggs!” cried Farmer Brown. In the background he heard them. Click, clack, moo. Click, clack, moo. Clickety, clack, moo. “Cows that type. Hens on strike! Whoever heard of such a thing? How can I run a farm with no milk and no eggs?” Farmer Brown was furious. Farmer Brown got out his own typewriter. “Dear Cows and Hens: There will be no electric blankets. You are cows and hens. I demand milk and eggs. Sincerely, Farmer Brown” Duck was a neutral party, so he brought the ultimatum to the cows. The cows held an emergency meeting. All the animals gathered around the barn to snoop, but none of them could understand Moo. All night long, Farmer Brown waited for an answer. Duck knocked on the door early the next morning. He handed Farmer Brown a note: “Dear Farmer Brown, We will exchange our typewriter for electric blankets. Leave them outside the barn door and we will send Duck over with the typewriter. Sincerely, The Cows” Farmer Brown decided this was a good deal. He left the blankets next to the barn door and waited for Duck to come with the typewriter. The next morning he got a note: Dear Farmer Brown, The pond is quite boring. We’d like a diving board. Sincerely, The Ducks Click, clack, quack. Click, clack, quack. Clickety, clack, quack.

Leave them outside the barn door and we will send Duck over with the typewriter. Sincerely, The Cows” Farmer Brown decided this was a good deal. He left the blankets next to the barn door and waited for Duck to come with the typewriter. The next morning he got a note: Dear Farmer Brown, The pond is quite boring. We’d like a diving board. Sincerely, The Ducks Click, clack, quack. Click, clack, quack. Clickety, clack, quack.

1

We take your child's unique passions

2

Add their current reading level

3

And create a personalized learn-to-read plan

4

That teaches them to read and love reading

TRY IT FOR FREE

Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type

We have updated our Privacy Policy Please take a moment to review it. By continuing to use this site, you agree to the terms of our updated Privacy Policy.

"Farmer Brown has a problem.

His cows love to type.

All day long he hears

Click, clack, moo.

Click, clack, moo.

Clickety, clack, moo."

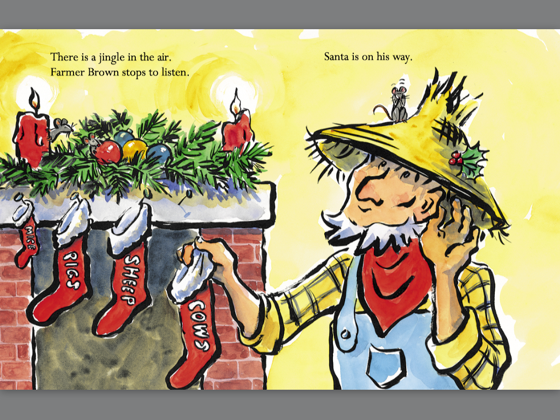

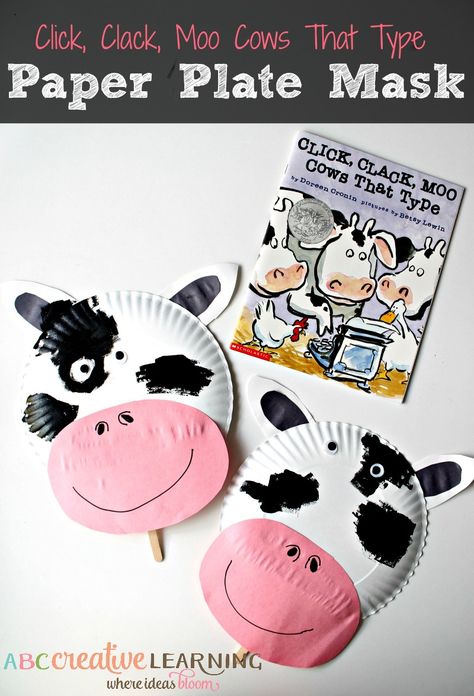

Have you ever read a more absurd and hilarious first page of a picture book? The black-lined double-page watercolors of the big-nosed, white-bearded, straw-hatted, red-bandanna and denim-overalled Farmer Brown and his black and white, pink-nosed, smiling cows with their old-fashioned typewriter, not to mention 10 chickens and Duck, won Betsy Lewin her first Caldecott Honor, and no wonder. The paintings look so goofy and slapdash, but they're the height of bovine nirvana.

Farmer Brown can't believe his ears and his eyes when his cows post on the barn door a typed demand for electric blankets. "Cows that type? Impossible!" The farmer refuses to accede, so the cows go on strike. Their new note reads, "Sorry. We're closed. No milk today." Pretty soon, the demands escalate, with the chickens wanting electric blankets, too. They withhold their eggs. Farmer Brown is furious. "How can I run my farm with no milk and no eggs?" The frustrated old guy gets out his own typewriter and demands milk and eggs. Duck, a neutral party, brings the ultimatum to the cows, who hold an emergency meeting in the barn. Here is one of my favorite sentences ever: "All the animals gathered around the barn to snoop, but none of them could understand Moo." Cows and farmer hammer out a compromise. The cows will send Duck over with their typewriter in exchange for electric blankets. Farmer Brown agrees to it. Duck, of course, has a whole other plan.

They withhold their eggs. Farmer Brown is furious. "How can I run my farm with no milk and no eggs?" The frustrated old guy gets out his own typewriter and demands milk and eggs. Duck, a neutral party, brings the ultimatum to the cows, who hold an emergency meeting in the barn. Here is one of my favorite sentences ever: "All the animals gathered around the barn to snoop, but none of them could understand Moo." Cows and farmer hammer out a compromise. The cows will send Duck over with their typewriter in exchange for electric blankets. Farmer Brown agrees to it. Duck, of course, has a whole other plan.

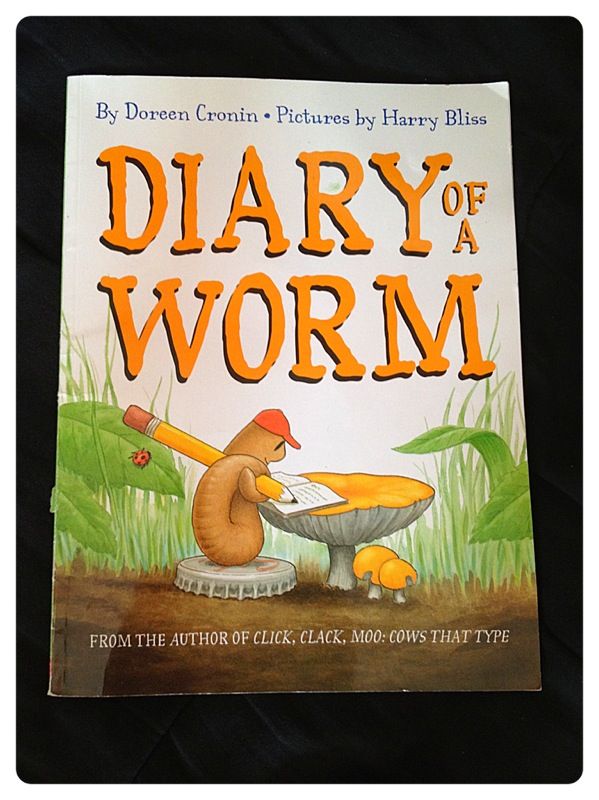

For those of you adults who have ever been involved with any kind of job action at work, this book gives new meaning to terms like negotiation, compromise, and strongarm tactics. Note the back flap with the unsurprising tidbit that Doreen Cronin is an attorney (and now the author of many delectable picture books, including Diary of a Worm), who collects antique typewriters. Note, too, that your techno-hyped children may not know just what a typewriter is, so if you have one lurking in your barn, bring it out to demonstrate the click and the clack of the keys. Or just use the updated version, a computer keyboard. Don't be surprised if they start writing persuasive letters demanding more allowance, candy, and better vacations.

Or just use the updated version, a computer keyboard. Don't be surprised if they start writing persuasive letters demanding more allowance, candy, and better vacations.

Themes : ANIMALS. CHICKENS. COWS. DUCKS. HUMOR.

CRITICS HAVE SAID

- Cronin humorously turns the tables on conventional barnyard dynamics; Lewin’s bold, loose-lined watercolors set a light and easygoing mood that matches Farmer Brown’s very funny predicament. Kids and underdogs everywhere will cheer for the clever critters that calmly and politely stand up for their rights, while their human caretaker becomes more and more unglued.

–Publishers Weekly

IF YOU LOVE THIS BOOK, THEN TRY:

- Babcock, Chris. No Moon, No Milk. Crown, 1993.

- Becker, Suzy. Manny’s Cows: The Niagara Falls Tale. HarperCollins, 2006.

- Choldenko, Gennifer. Moonstruck: The True Story of the Cow Who Jumped Over the Moon. Hyperion, 1997.

- Cronin, Doreen. Diary of a Worm. HarperCollins, 2003. (And others in the Diary series.)

- Cronin, Doreen. Dooby Dooby Moo. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Cronin, Doreen. Duck for President. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- Cronin, Doreen. Giggle, Giggle, Quack. Simon & Schuster, 2002.

- Cronin, Doreen. Thump, Quack, Moo: A Whacky Adventure. Simon & Schuster, 2008.

- Cronin, Doreen. Wiggle. Atheneum, 2005.

- Demuth, Patricia Brennan. The Ornery Morning. Dutton, 1991.

- Doyle, Malachy. Cow. McElderry, 2002.

- Egan, Tim. Metropolitan Cow. Houghton Mifflin, 1996.

- Egan, Tim. Serious Farm. Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

- Feiffer, Jules. Bark, George. HarperCollins, 1999.

- Himmelman, John. Chickens to the Rescue. Henry Holt, 2006.

- Johnson, Paul Brett. The Cow Who Wouldn’t Come Down. Orchard, 1993.

- Kirby, David, and Allen Woodman.

The Cows Are Going to Paris. Caroline House, 1991.

The Cows Are Going to Paris. Caroline House, 1991. - Krosoczka, Jarrett J. Punk Farm. Knopf, 2005.

- Palatini, Margie. Moo Who? HarperCollins, 2004.

- Rostoker-Gruber, Karen. Rooster Can’t Can’t Cock-a-Doodle-Doo. Dial, 2004.

- Shannon, David. Duck on a Bike. Scholastic, 2002.

- Speed, Toby. Two Cool Cows. Putnam, 1995.

- Vail, Rachel. Over the Moon. Orchard, 1998.

- Waddell, Martin. Farmer Duck. Candlewick, 1992.

- Willems, Mo. Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! Hyperion, 2003.

DIALOGUES WITH A COW | Science and life

Yuri Borisovich Przhiemsky retired, ended up in the village and, being a solid man, bought a cow. The city dweller had to learn how to water, feed, graze, milk and treat his pet. Neighbors dealt with cows with loud shouts, swearing, twigs or sticks. They laughed at the "urban" and predicted deplorable results. But the predictions did not come true. The cow and the former city dweller have lived in perfect harmony for 14 years, the cow has brought 8 calves. According to the "rules" it is high time to put her on the meat, and she increases milk yield, "communicates" with the owners, helps them live. They began to need each other. In the city, Yuri Borisovich was engaged in technology, but I was always amazed by the stories about bears, dogs, birds that he brought from travels around the country. His powers of observation played a decisive role in establishing contact with the cow. Their relationship developed in several stages. The first one - acquaintance ("if you don't touch us - we won't touch you, if you touch us, we won't let you down") - was a success. Yuri Borisovich turned out to be a talented student, and then, at the second stage, the training in mutual understanding was continued in the language of "postures and gestures." Observations of Yury Borisovich and his wife (psychologist, candidate of sciences, associate professor of Moscow State University) give reason to believe that cows listen very carefully to people's conversations and understand them.

But the predictions did not come true. The cow and the former city dweller have lived in perfect harmony for 14 years, the cow has brought 8 calves. According to the "rules" it is high time to put her on the meat, and she increases milk yield, "communicates" with the owners, helps them live. They began to need each other. In the city, Yuri Borisovich was engaged in technology, but I was always amazed by the stories about bears, dogs, birds that he brought from travels around the country. His powers of observation played a decisive role in establishing contact with the cow. Their relationship developed in several stages. The first one - acquaintance ("if you don't touch us - we won't touch you, if you touch us, we won't let you down") - was a success. Yuri Borisovich turned out to be a talented student, and then, at the second stage, the training in mutual understanding was continued in the language of "postures and gestures." Observations of Yury Borisovich and his wife (psychologist, candidate of sciences, associate professor of Moscow State University) give reason to believe that cows listen very carefully to people's conversations and understand them. It's amazing! After lectures on dolphins, I am usually bombarded with stories about the absolutely amazing abilities of pets - cats, parrots, dogs. Their owners, more often women, are observant and enthusiastic people, great psychologists, connoisseurs of the souls of "our smaller brothers." Cows have so far been bypassed by the attention of zoopsychologists. I would like to hope that the notes offered to the attention of readers will slightly open a new facet of the reality surrounding us.

It's amazing! After lectures on dolphins, I am usually bombarded with stories about the absolutely amazing abilities of pets - cats, parrots, dogs. Their owners, more often women, are observant and enthusiastic people, great psychologists, connoisseurs of the souls of "our smaller brothers." Cows have so far been bypassed by the attention of zoopsychologists. I would like to hope that the notes offered to the attention of readers will slightly open a new facet of the reality surrounding us.

Science and life // Illustrations

Science and life // Illustrations

‹

›

View full size

Doctor of Biological Sciences V. Belkovich.

If you think that cows are just cows, you are wrong...

Seton-Thompson

Having retired, my wife and I ended up in the outback of Tver, where for more than ten years we have been running a small peasant farm, in which there is also a cow. Circumstances have developed in such a way that in recent years I had to serve it mainly. I once participated in the development of the latest electronic information processing systems, and over the years I have developed the skill of tracking causal relationships. This helped me establish contact with my "ward" and allowed me to learn a lot of amazing things about the life of cows.

I once participated in the development of the latest electronic information processing systems, and over the years I have developed the skill of tracking causal relationships. This helped me establish contact with my "ward" and allowed me to learn a lot of amazing things about the life of cows.

In the winter at the beginning of 1991, we brought a young heifer Lysa from the collective farm, which after a few days calved and became a cow. At first (while we were making our barn) she lived with a neighbor along with his cow Beley, several years older than her. Maybe that's why Belya became Lysa's closest friend and indisputable authority. From my communication with this couple, most of the information presented below is gleaned.

A neighbor, a former shepherd, was skeptical about our purchase: “It won’t give much milk: the tail is not the right length, the asterisk is not located on the forehead, the head is big, and the character will cry.” One veterinarian rated her as nervous, and another rated her as feisty. The cow was really capricious, unpredictable and very easily excited over all sorts of trifles: she began to wind her horns, run and jump, dig the ground, "throw backwards." When she ran down the street, people shunned her. The first years of the absurd character manifested itself in everything. For example, if I tried to turn her to the right with a reason, then she turned left, and in order to go in the right direction, we made a 270-degree turn with her.

The cow was really capricious, unpredictable and very easily excited over all sorts of trifles: she began to wind her horns, run and jump, dig the ground, "throw backwards." When she ran down the street, people shunned her. The first years of the absurd character manifested itself in everything. For example, if I tried to turn her to the right with a reason, then she turned left, and in order to go in the right direction, we made a 270-degree turn with her.

Konrad Lorenz wrote that the more armed an animal species is, the less its individuals are inclined to use their "weapon" when clarifying the relationship between themselves. A dove can peck an opponent to death, while a wolf will limit itself to disassembly at the informational level. The cow is closer to the wolves in this respect. Horns, hooves and a "weight category" that is incomparable with a person make cows not as harmless as they might seem from the outside. So, in our district, a cow "for no reason at all" broke the owner's arm. There were other accidents as well.

There were other accidents as well.

During the first years, Lysa tried to bring the necessary information to our attention with the help of posture, gestures and actions. She began by demonstrating her fighting abilities. When I, bending down, cleaned the barn with a pitchfork, she quietly approached from behind and slipped the horn under my padded jacket. I looked around and saw in her eyes: "Well, grandfather, is it very scary?" She quickly realized that this did not frighten me, and began to show how skillfully she knew how to kick: left, right, forward, backward, obliquely to the side.

One day for the second winter, she jumped out into the covered courtyard where I was cleaning. In the corner stood the remnant of a roll of straw about half a meter in diameter. The bald man ran up to him and began to beat with his horns, left, right, left ... Then he lifted the "doll" with his horns and threw it over himself. She turned, ran up to the lying "doll", knelt down with her front legs and pressed her chest to the ground. She got up, put her hind leg on the "doll", turned her head and looked at me: "I saw what I can do if they offend me!" This is where the intimidation ended. Of the entire demonstrated arsenal, only a weak go-ahead obliquely back with the right hind leg remained. This eloquently meant: "Leave me alone!"

She got up, put her hind leg on the "doll", turned her head and looked at me: "I saw what I can do if they offend me!" This is where the intimidation ended. Of the entire demonstrated arsenal, only a weak go-ahead obliquely back with the right hind leg remained. This eloquently meant: "Leave me alone!"

I soon realized that waving the horn in my direction meant, "Don't do it!" I have seen more than once how other cows use a similar gesture in the same sense in communicating with each other. Quickly swinging his horns from side to side, Lysa expresses his displeasure. Most often this happens when service is too slow, in her opinion: for example, when there is a delay in laying out hay or grass in a manger. She is very impatient and shakes her horns often and on every trifling occasion.

Cows determine their rating in the herd as follows: they approach each other head to head, sniff their muzzle, “scratch” horns on horns, and then, resting their foreheads, press each other, trying to move the rival back. The strongest cow will be the main one.

The strongest cow will be the main one.

Another and probably the main reason that cows are able to solve their problems by exchanging information is due to life in a herd - a community of their own kind. And, of course, the centuries-old life next to man, in close interaction and in complete dependence on him, could not but affect.

For the first year or two, Lysa expressed her request to do something for her by touching her hand with her nose or lips. It could mean: "Give me something tasty" or "Let's go to our mowing, there is a good aftertaste." If the request is very serious, for example, about the fate of her calf, then she intensively licks her hands before and after calving. It expresses gratitude in the same way. However, the same request: "Scratch!" - she expresses in different ways, depending on which place she asks to be scratched. If the withers, then she will scratch it herself with a little horn. If it is on the side, back or leg, then it will lick this place a couple of times and look at you pleadingly. When a cow asks another to lick her face and neck, she comes close and lowers her head. It seems that the ranking of the cow in the herd or the circumstances that make you show sympathy for her matter.

When a cow asks another to lick her face and neck, she comes close and lowers her head. It seems that the ranking of the cow in the herd or the circumstances that make you show sympathy for her matter.

At first, I was afraid to indulge all the requests of Lysa: "would she sit on my neck." However, practice has shown that the cow feels the need for mutual concessions and compromises, and in extreme situations, the final decision is left to the owners. I was pleasantly surprised that she understands the meaning of "prepayment" well, and if she does not want to follow any instruction, for example, go home, then she will not even take an apple in advance. And vice versa, if she has already stocked up and is not averse to going home, she will turn her head to you and look expressively: "I'm already full. Give me a bite, and I'll go home if you say so." On the way to the house, he often puts a "bun" and starts up a "fountain", which is very convenient for the owners. At the same time, she turns her head: "Grandfather, have you seen? Give. " Several times she refused to take the "tasty piece" given to her at the end of the milking, if I blamed her for bad behavior. With her character, it was possible to achieve much more by praising rather than scolding.

" Several times she refused to take the "tasty piece" given to her at the end of the milking, if I blamed her for bad behavior. With her character, it was possible to achieve much more by praising rather than scolding.

If the cow has reason to believe that the person with whom she is dealing will try to understand her and favorably react to her desires, then she will be very persistent and inventive both in inventing new gestures to express her desires, and in revealing their meaning. So, one summer, when there were a lot of midges, on the way to the house, Lysa licked the vein that runs from the udder along the belly a couple of times and looked at me pleadingly. I understood and carefully stroked my hand along the vein. Then she licked the folds of skin at the transition from the neck to the chest. I began to stroke them along the same length and immediately received a go-ahead with the horn. After that, she herself licked the folds a couple of times. This went on for over a week. I did not understand her behavior, but I tried to understand. Finally it dawned on me - in this case, the signal with the horn had a slightly different meaning: "Don't do so !" She wanted me to stroke the folds the way she showed - across, not along the neck. I began to stroke them across. The fingers fell into the hollows between the folds, where a lot of midges accumulated. When I finished ironing, Bald turned her head, and in her eyes I read: “I finally understand. However, you are dumb, grandfather!" Since then, this request has become everyday: "Stroke the vein from the right side, the folds on the neck, and now the vein from the left side." Moreover, this request often meant additionally: "I have already eaten full and not against going to the house if you really ask."

I did not understand her behavior, but I tried to understand. Finally it dawned on me - in this case, the signal with the horn had a slightly different meaning: "Don't do so !" She wanted me to stroke the folds the way she showed - across, not along the neck. I began to stroke them across. The fingers fell into the hollows between the folds, where a lot of midges accumulated. When I finished ironing, Bald turned her head, and in her eyes I read: “I finally understand. However, you are dumb, grandfather!" Since then, this request has become everyday: "Stroke the vein from the right side, the folds on the neck, and now the vein from the left side." Moreover, this request often meant additionally: "I have already eaten full and not against going to the house if you really ask."

Once, when she came home from the paddock, she stood with her right side towards me, turned her head and, looking into my face, pointed her nose at her raised hind leg: "Grandfather, my leg hurts. Help me!" All the while I was carefully examining and feeling the hoof and around it, I kept my leg elevated. The bruise soon stopped hurting.

Help me!" All the while I was carefully examining and feeling the hoof and around it, I kept my leg elevated. The bruise soon stopped hurting.

Another time she showed how she cleans her tail. She turned it over to her right side, took the dirty brush in her mouth and chewed it. Some time later, when the tail became dirty again, she also bent it on its side, turned her head and, looking at me, pointed to the dirty brush with her nose: “Grandfather, clean it. I don’t want to suck the manure!” So the "washing" of the tail has become traditional with us. It is very convenient to communicate this request during milking by placing a dirty tail on my left hand or hitting me with it.

There were other situations when she pointed her nose at something to me.

*

At one time, my neighbor and I grazed our pair together. Then we decided to walk with them in turn. When I first went alone to graze them, I took a twig just in case - a neighbor always pastured Belya with a stick. Belya kept looking at me warily. I don’t remember why, I took a few steps towards her. She cringed all over, turned her head and jumped sideways. I stopped. After a while, he tried again. Everything repeated exactly. I had a hunch and I decided to test it. Belin's nose pointed exactly at the twig clamped under the arm of my left hand. I immediately defiantly threw the twig on the ground. Bela immediately relaxed and began to graze calmly. So, on her initiative, I began a strong friendship with her for many years.

Belya kept looking at me warily. I don’t remember why, I took a few steps towards her. She cringed all over, turned her head and jumped sideways. I stopped. After a while, he tried again. Everything repeated exactly. I had a hunch and I decided to test it. Belin's nose pointed exactly at the twig clamped under the arm of my left hand. I immediately defiantly threw the twig on the ground. Bela immediately relaxed and began to graze calmly. So, on her initiative, I began a strong friendship with her for many years.

Moreover, Belya has become my faithful assistant. The fact is that Lysa was terribly afraid of being alone in the pen, and if she tried to jump out through the fence, she could be crippled. Therefore, we took her from the corral a little earlier than other cows. This opened up unlimited opportunities for her to show her absurd character. She deliberately "did not hear" that her name was called, she did not go to the gate, but to the far corner of the paddock, and so on. Over time, Belya began to help me. When, standing at the gate, I called to Lysa, Belya came towards me with a determined step. Lysa could not stand this and followed her. Of course, "delicious pieces" received both. True, Lysa did not take hers at the gate, but after walking a little along the street. To take a "piece" in front of other cows, she apparently considered it degrading to her dignity.

Over time, Belya began to help me. When, standing at the gate, I called to Lysa, Belya came towards me with a determined step. Lysa could not stand this and followed her. Of course, "delicious pieces" received both. True, Lysa did not take hers at the gate, but after walking a little along the street. To take a "piece" in front of other cows, she apparently considered it degrading to her dignity.

One day at the end of spring I came for Lysa earlier than usual. All the cows were lying on the green grass, the gentle sun was shining, a gentle breeze was blowing, there were no horseflies yet. I go up to the fence and say: "Lysa, get up. Let's go home." She puts her head on the grass, shakes it from side to side and looks at the main cow lying next to her. She repeats Lysin's gesture, then raises her head and defiantly licks her breasts. Alternates both gestures several times and all this time looks at my face: "Grandfather, it's so nice to lie down, leave her with us." And Lysa lies quietly. With such authoritative intercession, I decided to take my cow later, along with everyone else. I later saw both of these gestures in the same meaning more than once, both with Lysa and with other cows. Lysa sometimes reports the same thing by scratching his back or side with his horn.

With such authoritative intercession, I decided to take my cow later, along with everyone else. I later saw both of these gestures in the same meaning more than once, both with Lysa and with other cows. Lysa sometimes reports the same thing by scratching his back or side with his horn.

During the first years, Lysa ran away to the neighboring village three or four times during the summer for no reason at all. And far from immediately, I realized that this is how she punishes me for showing the slightest attention to other cows. Moreover, it soon became clear that I was not allowed to talk to the mistresses of some cows. The punishment for this was the same. The only cow who was allowed to communicate with and was allowed to give "delicious pieces" was her friend Belya.

Cows can joke. Once I was grazing Lysa and Belya near a copse. Suddenly I see Belya walking at a walking pace along the edge of the forest, and Lysa "hung" on her tail. Realizing that it was useless to run a race with cows, he decided to overtake them at a very fast pace. I’m already walking nearby, first at the level of Beli’s tail, and then at the shoulder. I see a mischievous eye carefully watching me: "Well, press it again, grandfather! Well, just a little more!" I press with all my might. There is no more than half a meter left when it will be possible to hook and turn Belya. Then she goes into a barely noticeable trot, and I again find myself at the level of her tail. And the eye urges: "Well, click, grandfather! You walk so fast!" All this is repeated several times while we are moving along the edge. Suddenly I skip past Beli, turn to her and see a surprised face: "Where did you run so fast? Here in the hollow there is such good grass. Lysa and I are staying!"

I’m already walking nearby, first at the level of Beli’s tail, and then at the shoulder. I see a mischievous eye carefully watching me: "Well, press it again, grandfather! Well, just a little more!" I press with all my might. There is no more than half a meter left when it will be possible to hook and turn Belya. Then she goes into a barely noticeable trot, and I again find myself at the level of her tail. And the eye urges: "Well, click, grandfather! You walk so fast!" All this is repeated several times while we are moving along the edge. Suddenly I skip past Beli, turn to her and see a surprised face: "Where did you run so fast? Here in the hollow there is such good grass. Lysa and I are staying!"

*

It so happened that Lysa always calved with me. The first time or two it was by accident, and later - at her discretion. When the time of calving approached (she calved in winter and more often in the morning), I looked into her barn more often, and also at night. On one of her visits, she showed with all her appearance and behavior that she would calve in a few hours. After that, I went to her every hour and a half. Finally, at my appearance, she turns several times, sniffing the litter, lies down and shows me with her nose where I should stand to receive the calf. All the time of calving, he looks me in the face: "Grandfather, help me!" If the calf was large and walked slowly, he dragged him by the legs during the attempts. Once upon a time, more serious help was needed. The calf was big-headed and large and did not come out in any way. I told Lysa to wait. I went to the hut, washed my hands and took the lavsan braid. Returning to the cow, he first found one leg, and then the one that was stuck, straightened it out. When pulling out the calf, the cow and I acted in concert. After short breaks on the command "Come on!" The bald man pushed hard, brought his hind legs under his stomach, and I pulled the front legs of the calf with a ribbon.

After that, I went to her every hour and a half. Finally, at my appearance, she turns several times, sniffing the litter, lies down and shows me with her nose where I should stand to receive the calf. All the time of calving, he looks me in the face: "Grandfather, help me!" If the calf was large and walked slowly, he dragged him by the legs during the attempts. Once upon a time, more serious help was needed. The calf was big-headed and large and did not come out in any way. I told Lysa to wait. I went to the hut, washed my hands and took the lavsan braid. Returning to the cow, he first found one leg, and then the one that was stuck, straightened it out. When pulling out the calf, the cow and I acted in concert. After short breaks on the command "Come on!" The bald man pushed hard, brought his hind legs under his stomach, and I pulled the front legs of the calf with a ribbon.

Bald, as the locals say, refers to the "strict" cows. He only allows his wife and me to the udder, and only in one place - at the manger in the barn. He beats other milkmaids with his hoof, so no one could help us milk. At first, my wife milked, but when she had to leave unexpectedly for a long time, I had to master the milking. Unfortunately, before that I had never been able to see how professional milkmaids do it. Lysa taught me how to milk. She pointed out my mistakes and wrong actions by raising her hind leg, more often the right one. It could mean: "Lubricate your nipples better", "Move to another nipple. Not this one!", "Don't press that nipple so hard!", "Stop milking with both hands. Finish milking with one right!" If I did not correct the mistake, then she lightly knocked on my knee with her back foot.

He beats other milkmaids with his hoof, so no one could help us milk. At first, my wife milked, but when she had to leave unexpectedly for a long time, I had to master the milking. Unfortunately, before that I had never been able to see how professional milkmaids do it. Lysa taught me how to milk. She pointed out my mistakes and wrong actions by raising her hind leg, more often the right one. It could mean: "Lubricate your nipples better", "Move to another nipple. Not this one!", "Don't press that nipple so hard!", "Stop milking with both hands. Finish milking with one right!" If I did not correct the mistake, then she lightly knocked on my knee with her back foot.

Lysa used the "capital punishment" only a few times - she raised her hind leg high, quickly lowered it into the pail and immediately took it out of there, turned her head and watched me, upset, pour out the spoiled milk. When she used the "rig" for the last time, after much thought, I switched from pinch milking to the more efficient and apparently more enjoyable fist milking for the cows. The bald man was clearly pleased with this. About a year and a half later, she suggested in the same way to change the sequence of teat milking - to start milking from the back. During milking, Lysa very carefully monitors compliance with the consistent and timely change of nipples. Milking ends with collecting "drops" on all nipples mixed. Here Lysa demands that I change the nipples more often, and do not touch the empty ones at all.

The bald man was clearly pleased with this. About a year and a half later, she suggested in the same way to change the sequence of teat milking - to start milking from the back. During milking, Lysa very carefully monitors compliance with the consistent and timely change of nipples. Milking ends with collecting "drops" on all nipples mixed. Here Lysa demands that I change the nipples more often, and do not touch the empty ones at all.

Due to our inexperience, we taught Lysa to milk at a manger full of hay or grass. In late autumn, finding good grass can be difficult. If she does not like the feeding, she starts to step over her feet, throw grass out of the nursery, and sometimes even leaves the milking in the yard, but she never touches the pail with her feet. It was a very dry autumn and the grass burned down. I brought for milking gray, apparently sick, mouse peas, because where I was this time, I did not find anything better. The bald came out of the milking almost immediately. I put it back in place. Soon she went out a second time (which never happened), quickly went up to the other, almost empty mangers standing in the yard, took out from them a green twig of a flowering meadow rank and, turning, showed me her yellow little flower. He promised her not to bring such bad peas again, returned her to the barn, tied her up and finished milking.

I put it back in place. Soon she went out a second time (which never happened), quickly went up to the other, almost empty mangers standing in the yard, took out from them a green twig of a flowering meadow rank and, turning, showed me her yellow little flower. He promised her not to bring such bad peas again, returned her to the barn, tied her up and finished milking.

From the above, it is clear that there is a discrepancy between the limited number of gestures and actions used by the Bald in milking, and the large amount and variety of information reported. However, often a gesture or action serves only as a signal of dissatisfaction or a request. I will note three poses expressing the daily desires of a cow. When Lysa was in the yard and wanted to drink, she stood with her right side to the entrance to the hut and turned her head to the door leading to the hallway. If she wanted to eat, she stood with her head to the door leading to the street, or to the manger. When she asked to be scratched all over with a comb, she stood obliquely in the middle of the yard, licked her back or side, looking pleadingly at me.

*

The language of sounds in cows, it seems to me, is very poor. They either moo loudly (the locals say "yell"), or "torment" with their mouths closed, referring to the calf. The sound of each cow's moo is slightly different from the other cows' moo, but I did not notice that it changed depending on the situation. Mistresses recognize their cows by their voice. Some cows moo often, others do not open their mouths for months. Only once did I hear a "conversation" between Beli and Lysa. They were grazing together at the far end of the paddock and far apart. When I came to pick up Lysa, Belya saw me and very shortly told Lysa about it. She immediately raised her head from the tall grass, turned in my direction and followed Beley to me.

One day, towards the fall, Lysa coughed violently all evening. I decided to go to the vet, but the next day everything was calm. Then another cough, a break and another cough. Since we abandoned the formula "for no reason at all" for a long time, I began to think about situations when she coughs, and I realized that Lysa had come up with a convenient way for her to sound appeal to her owners: "Kykh, kykh!" Hearing a cough, you begin to think about why Lysa turned to you, and surprisingly quickly you catch the essence of the matter.

For example, in the fall, Lysa would come out of the barn so that it would be convenient for me to remove the manure, straighten the bedding, and put the hay in the manger. When severe colds came, in the morning she stopped going out, and with her I performed the same sequence of actions. After a while I hear: "Kykh, kykh." After a little thought, he first began to spread the hay in the manger, and then do the cleaning. The cough was gone. The bald-head moved her legs in half a word, so that it would be convenient for me to clean up, and she herself ate hay from the manger. I involuntarily recalled how, at the beginning of her life with us, she communicated the same request to me, butting with her horns the pitchfork with which I cleaned the barn.

A cough can also express dissatisfaction with our actions or inaction. So, when we piled up a pile of firewood against the wall of the barn, then a prolonged cough was heard from it: "Don't knock!" At the end of a long milking, you can hear a cough, which means: "Quickly finish it. Tired!"

Tired!"

It soon became clear that Lysa understood human speech well, and to "control" the cow, we began to use words and "tasty pieces" instead of a stick and a whip. We started with a simple one: “Give me the horns, I’ll put on (take off) the reins”, “Go to your place!”, “Get out of the barn”, “Let me pass”, “Move over”. However, it also happens that you say: "Come here!", And she stands and chews gum with an impenetrable look. "I'll scratch." Immediately jumps up to me: "I would have said so right away."

At the very beginning, it turned out that Lysa does not tolerate walking behind someone on a leash, as many domestic cows walk. When I tried to lead her, for example, from a paddock, she, after walking a little, stood up in her tracks, and it was very difficult to move her in the right direction. And so several times at short intervals. When I realized that this was a test: "We are going together or they are dragging me along," I also immediately began to stop. After standing for quite a bit, Lysa moved on. After several such checks, we calmly walked in the right direction. Now I walk on the side of her shoulder and carry the end of the rein. If the path is narrow or we are walking through tall grass, I walk behind and hold the reins. I discuss in advance where we are going: to the paddock, to the cows, to the hillock, to the field, etc. For a long time the problem of the first step in the right direction remained difficult if she did not want to go where I said. Finally I thought to tell her: "Go ahead!"

After several such checks, we calmly walked in the right direction. Now I walk on the side of her shoulder and carry the end of the rein. If the path is narrow or we are walking through tall grass, I walk behind and hold the reins. I discuss in advance where we are going: to the paddock, to the cows, to the hillock, to the field, etc. For a long time the problem of the first step in the right direction remained difficult if she did not want to go where I said. Finally I thought to tell her: "Go ahead!"

There were also situations when Lysa had to act on information that was communicated to her in words for the first and only time. So, my wife grazed her in the forest near the edge, I did not know where they were, and went to look for them, calling out to my wife. Since I can't hear well, it was pointless for me to answer, and my wife said: "Bald, grandfather is looking for us. Let's go quickly to him!" Soon I saw a cow with its head held high, making its way towards me through the thickets, and behind it - my wife.

*

Over the years, I developed a habit, dealing with Lysa and Belya, and then with other cows from our village, without hesitation, telling them everything that I needed to bring to their attention. Usually they correctly understood the verbal instructions associated with their movement: "Go, I will open the gate to the paddock (from the paddock)", "Get out of here", "Turn back", etc.

One day the four of us took the cows out to a small open pasture. Among the cows was Milka - small, affectionate, nimble and, as the mistress said, "fidgety". The cows were grazing next to us, and we had a general conversation, in which I spoke warmly about Milk in a few phrases. Before I could finish the thought, I feel that someone is pushing my hand. I turn around and see: Milka is licking my elbow. Everyone saw this and laughed in unison. And Milka began to lick my hands, and so insistently that the hostess drove her away.

Once, quite a long time ago, he asked Lysa to pick me up from the bench after the end of the milking. She pulled back a little, turned and lowered her head towards me so that I could grab it well with both hands, and famously lifted me up and forward. After that, it remains only to give her a "delicious piece." This has become the traditional end of milking. If she was very dissatisfied with my actions during milking, then she could refuse to lift me. Once I could not understand why she stopped lifting me, because I did everything right. True, during milking I mentally imagined how I would milk another cow in the Moscow region. When after that I asked to pick me up, Lysa turned her head, but did not lower it and looked at me with a condemning look. I decided to be more careful in my thoughts - during milking, think only about our affairs with Lysa. At the next milking, she raised me almost to the ceiling and her eyes were cheerful.

She pulled back a little, turned and lowered her head towards me so that I could grab it well with both hands, and famously lifted me up and forward. After that, it remains only to give her a "delicious piece." This has become the traditional end of milking. If she was very dissatisfied with my actions during milking, then she could refuse to lift me. Once I could not understand why she stopped lifting me, because I did everything right. True, during milking I mentally imagined how I would milk another cow in the Moscow region. When after that I asked to pick me up, Lysa turned her head, but did not lower it and looked at me with a condemning look. I decided to be more careful in my thoughts - during milking, think only about our affairs with Lysa. At the next milking, she raised me almost to the ceiling and her eyes were cheerful.

In summer and autumn, we kept some stock of cut grass on the porch for feeding, and often in the evening discussed with my wife what and how much grass to put in the manger. If they looked into the yard, they saw Lysa standing in the corner closest to the porch with splayed ears and genuine interest in her eyes. We used to discuss the more serious issues of cow maintenance over morning tea, when Lysa was still at home in a barn or covered yard behind two or three log walls. However, she knew about the decisions made before it was communicated by words or actions. So, she became gloomy and intensely licked our hands when we decided to give her calf away. Usually, when she came home from the corral, she greeted her calf with "torment" before she entered the barn and did not see him. On the day when the calf was taken away, she certainly knew about it, although she could not see how it was taken away. Arriving home darker than a cloud, she did not "torment" and did not even deign to look at the empty calf-house. It seemed that she was always aware of all our decisions concerning her at the moment they were made.

If they looked into the yard, they saw Lysa standing in the corner closest to the porch with splayed ears and genuine interest in her eyes. We used to discuss the more serious issues of cow maintenance over morning tea, when Lysa was still at home in a barn or covered yard behind two or three log walls. However, she knew about the decisions made before it was communicated by words or actions. So, she became gloomy and intensely licked our hands when we decided to give her calf away. Usually, when she came home from the corral, she greeted her calf with "torment" before she entered the barn and did not see him. On the day when the calf was taken away, she certainly knew about it, although she could not see how it was taken away. Arriving home darker than a cloud, she did not "torment" and did not even deign to look at the empty calf-house. It seemed that she was always aware of all our decisions concerning her at the moment they were made.

From highly experienced fellow villagers I heard more than once that the cows know when the owners decide to slaughter them. Some of them even cry as they are led to the slaughter.

Some of them even cry as they are led to the slaughter.

The death of Beli, which the owners sold for meat, was a tragedy for Lysa. All summer, as she passed her barn to the paddock and back, she turned her head to him and seemed to listen. She had been a coward before, but now she was terribly afraid of everything unfamiliar and incomprehensible. A year later, having come to the stream, where she always ran to drink with Beley, she got drunk, and then looked around and began to cry. We did not manage to bring her to the watering place to this stream, although otherwise she became incomparably more obedient.

*

It seems to me that based on my experience with cows, the following assumptions can be made. To exchange information among themselves, they use jointly or separately sound, postures, actions, gestures and the direct transmission of their thoughts and images. Cows and bulls understand well both human speech directly addressed to them, and people's conversations among themselves. Moreover, they also learn what we do not say, but only think. They cannot be deliberately deceived.

Moreover, they also learn what we do not say, but only think. They cannot be deliberately deceived.

The volume, nature and method of transmitting information to a decisive extent depend on whether the cow hopes that the person with whom she is dealing will try to understand her, and, having understood, will favorably react to her requests and desires. To communicate their wishes to a person, they can try to use all the same methods as when communicating with each other, or they can come up with something new, such as coughing.

The question involuntarily arises why such amazing abilities of cows have gone unnoticed by zoopsychologists. And fiction also ignored them, although among the animal heroes there are foxes, cats, and horses ... There are no cows in the circus either. The attitude towards cows is condescending. There are apparently several reasons for this.

First, in cows, the "instrument of production" is their digestive organs. A lot of milk requires a lot of hay and grass, and therefore a lot of manure, which is not the most pleasant job.

Secondly, the cow is everyday rural prose. They are here at hand, even now there are almost every village. This is, first of all, milk, sour cream, cottage cheese. It is much more interesting to study dolphins that swim in the seas and oceans. The customer for such research is the navy, which means big money and long business trips. In general, "pure" and great science.

And where are the rural owners of cows looking? Here, apparently, the second cow "profession" influenced - they are suppliers of beef. Moreover, they are cut in the prime of life, you won’t take much for the meat of an old cow. Some owners of cows, like the cows themselves, cry at the same time. They cry and cut. Probably, it is easier for most owners to cut brainless cattle, so they try not to see what they, cows, really are.

Photo by I. Konstantinov.

Do you want to keep peace in your soul? Hug the cow more often

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Cow hugging (koe knuffelen in Dutch) is more than a wellness trend, and certainly more than just "mi-mi-mi". This activity, it turns out, is incredibly beneficial for mental health - no wonder its popularity is growing all over the world.

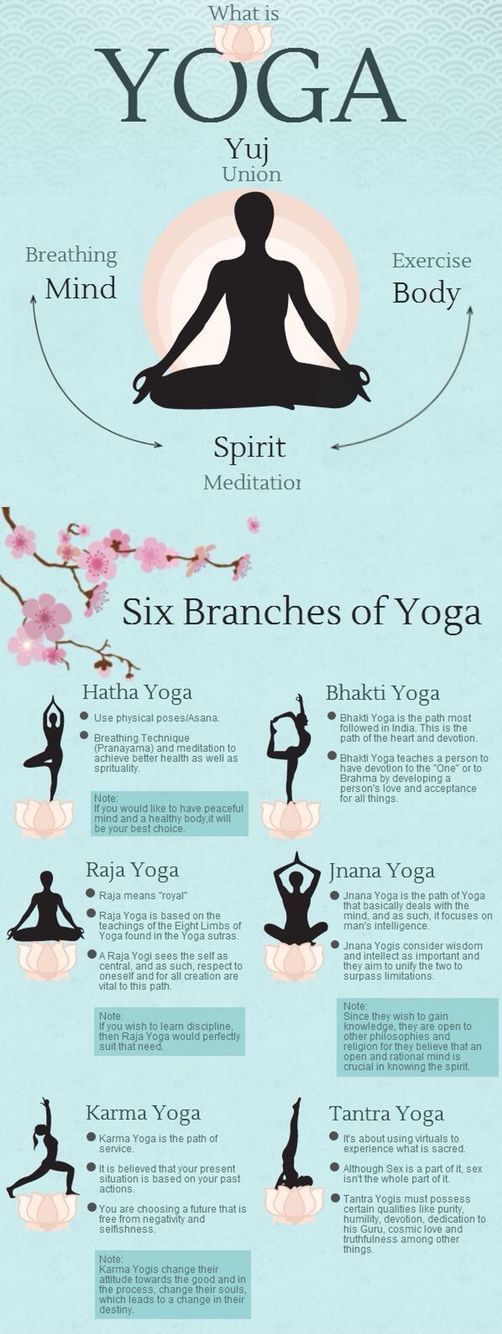

The world of wellness is full of whimsical trends - all to soothe our body and soul. For the sake of peace of mind, we are ready to do yoga surrounded by goats (here is a video about it) or take sound baths, plunging us into a pleasant nap in which we forget about all problems and, as some say, "clear" (see video).

And here's another self-help practice. She was born in the Netherlands, which is not surprising - after all, we are talking about cows, and the Dutch cow, as you know, is one of the oldest breeds of dairy cattle. But it turns out, not milk alone.

Hug a Dutch cow - and your state of mind will begin to change, you will feel serene and peaceful, adherents of the practice say.

Are you smiling already? You see, it is useful even just to imagine how you hug a cow.

- Strange friendship between animals of different species - what connects them?

- A woman or a cow: who is more important in India?

- "Save Penka". Bulgarian cow ran into EU bureaucracy

- Why do cows line up?

But seriously, koe knuffelen uses the natural healing properties of close and friendly contact between man and animal.

Do you still not understand? Think back to how you feel when you pet a cat curled up in your lap. Or hug your dog, standing up on its hind legs, to show how much he loves you.

Physical contact with a living being, from whom you do not expect anything bad, to whom you can comfortably snuggle up - this is the essence of what happens during hugging with cows.

Yes, they are much bigger than a cat or a dog, but that's the point. The more friend, the more heat comes from him.

The more friend, the more heat comes from him.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,The bigger the friend, the more warm they are

To become an avid cow hugger, you can start by visiting a special farm where you'll find exactly the kind of animals that love it too. (Not all cows are suitable for hugging. Some of them do not like closeness with a person at all - such is their nature.)

Cows have a slightly higher body temperature than humans and have a slower heartbeat. And, of course, there is something to hug. In combination, this acts healing for our psyche and incredibly soothing.

Some visitors to the farm spend two or three hours cuddled up next to a large and warm cow.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,The future cow for hugging can be seen already in her calf, say the owners of the farm. And if a cow licks you - this is the height of confidence.

"Cows are generally very calm animals. They don't fight, they don't get into trouble," explains the owner of one such farm in the Netherlands. "We have special cuddling cows, next to which you can sit or lie down - as you like."

They don't fight, they don't get into trouble," explains the owner of one such farm in the Netherlands. "We have special cuddling cows, next to which you can sit or lie down - as you like."

"Special cuddling cows are usually more calm and patient. You can already see the future cuddling cow in the calf - the character can be seen almost immediately," she says in the video below. to impose on the animal. When the cow gets bored, she just gets up and leaves."

Cow hugging is believed to bring a positive outlook on life and reduce stress by increasing the level of oxytocin in the human body, a hormone important in human relationships.

Oxytocin is known to induce feelings of contentment, reduced anxiety, and a sense of calm around a friend - in this case, a friendly cow.

The soothing, calming effect we feel when we stretch out on a couch with a cat by our side seems to be enhanced when we pet a larger mammal.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Feeling calm with a friend and surrounded by friendly cows

This healthy pastime was born over a decade ago in the Dutch countryside and is now part of a wider local movement to get people back to nature and rural life.