Early emergent reading

A Guide to Emergent Readers and Stages of Development – AdaptEd4SpecialEd

Krystie Yeo on

As a teacher, you know each of your students is unique. Never is that more apparent than with developing readers.

But you have lesson plans to propose and an entire class of students to teach.

You don't have time to design a reading development strategy for each of your little readers. Instead, you need a plan that will meet your students where they are, wherever that may be.

That's where the stages of reading development come in.

From early emergent readers to fluent readers, this simple breakdown helps you understand what stage each of your students is in so you can better meet their needs.

Want to know how to keep your readers on track and engaged?

Check out this guide to designing an instruction plan that addresses student readers of all stages.

What Is an Emergent Reader?

The emergent reader stage is one of the most vital in a student's journey. After all, 65% of 4th-grade students read at or below an early fluent reading level, which is only one step above the emergent reader stage.

Making sure a student progresses beyond emerging reader status with confidence and excitement, then, is important for assuring they improve beyond a basic level of reading comprehension.

Compared to an early emergent reader, emergent readers have learned the alphabet and have a handle on a large vocabulary of CORE words.

They've progressed beyond picture books and books with small regions of text. Now, your emergent readers have a good understanding of phonics and are starting to comprehend word meanings in addition to word sounds.

Emergent readers will typically read books with increasingly larger blocks of text. They can handle more complex sentences and rely less on pictures for comprehension.

While they may read books on familiar topics like home and family life, these stories go into greater depth than their early emergent reader precursors.

What's more, these students will have more confidence in recognizing high-frequency words.

They're venturing into both fiction and non-fiction stories. And most excitingly, emerging readers have begun to discover that reading has many uses and purposes beyond the classroom.

How to Engage and Excite Your Emergent Reader

Engaging and exciting your emergent reader is all about choosing the right books and offering assistance only when needed. The reasons behind this latter point are twofold.

First, your student needs to know they are supported and that you're there for assistance with sounding out words or comprehending definitions if needed.

But secondly, too much help can actually be detrimental to the child's confidence in their abilities.

They need to know that you think they can read independently. That way, it gives them the space to form their own confidence in reading independently.

The other tips for engaging and exciting your students is a no-brainer.

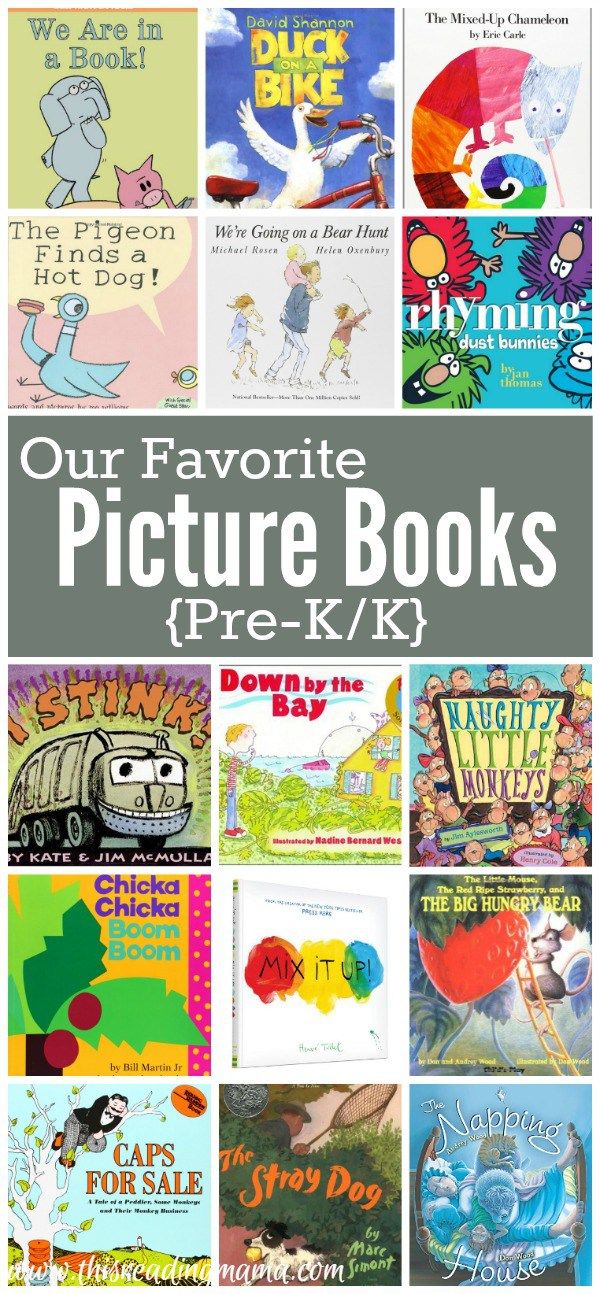

Choosing the right books that are challenging but not so challenging that the student feels defeated is vital to helping emerging readers move into the next stage of development. Our phonics collection starts at the very beginning.

Here are three books that we think are perfect for your emerging reader:

- A Giraffe and a Half by Shel Silverstein

- Look What I Can Do by Jose Aruego

- Do You Want to Be My Friend? by Eric Carle

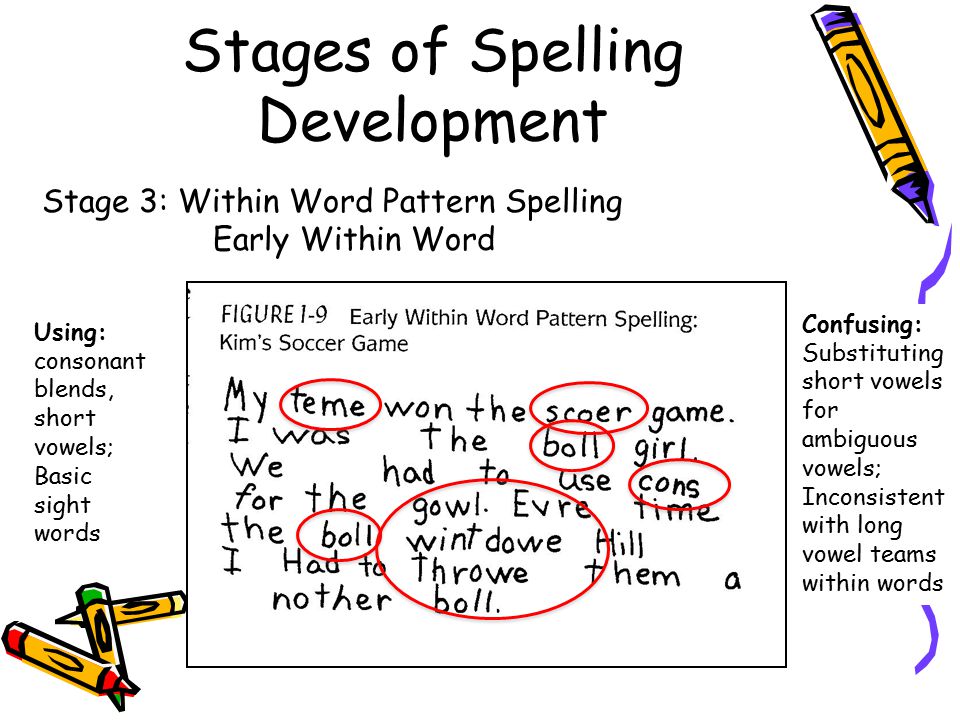

The 4 Stages of Reading Development

If you have a student who is still struggling to achieve emergent reader status despite your very best efforts, it's time to return to the four stages of development.

That way, you can see where your student is lagging while also exciting your little reader with all the learning they have to look forward to.

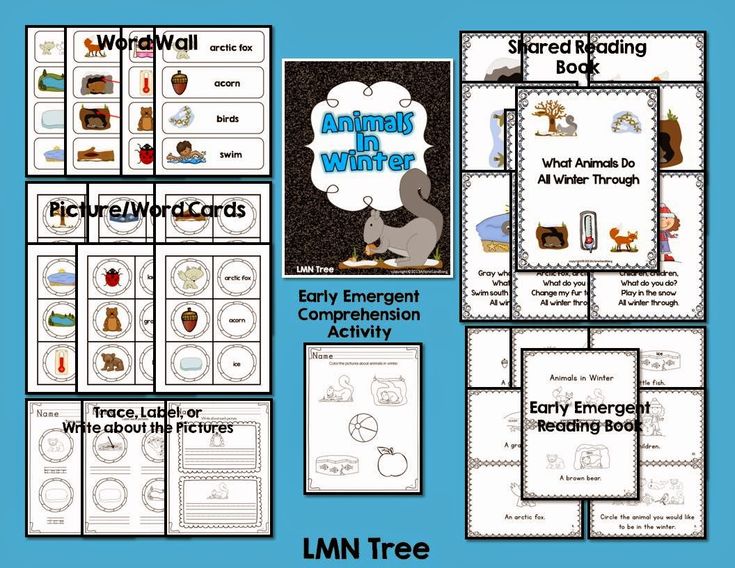

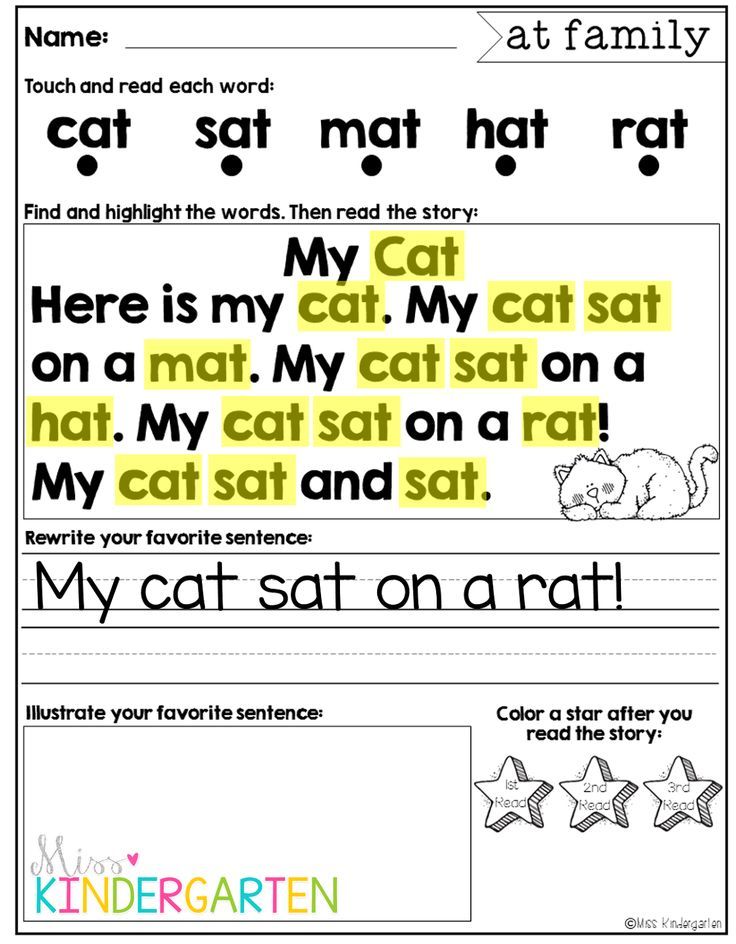

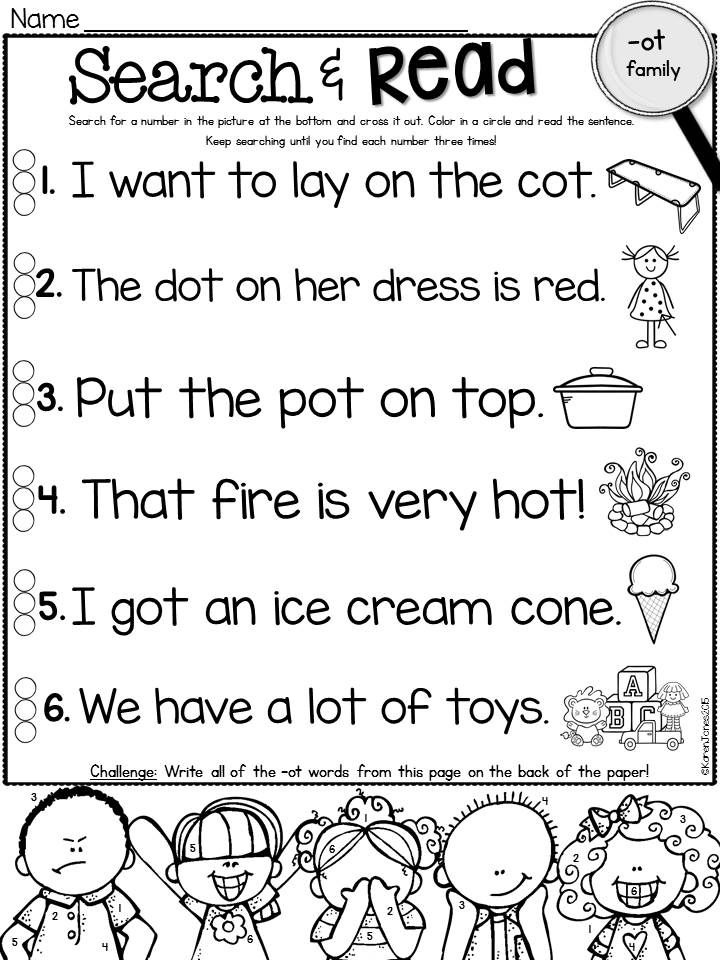

1. Early Emergent Readers

Early emergent readers are just beginning their reading journey.

These students are typically 6 months to 6 years old and are learning the alphabet.

As they advance, these readers begin to recognize the difference in uppercase and lowercase letters.

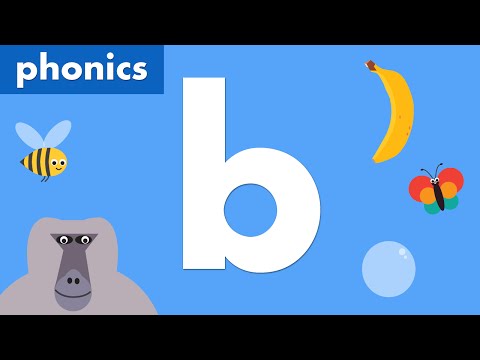

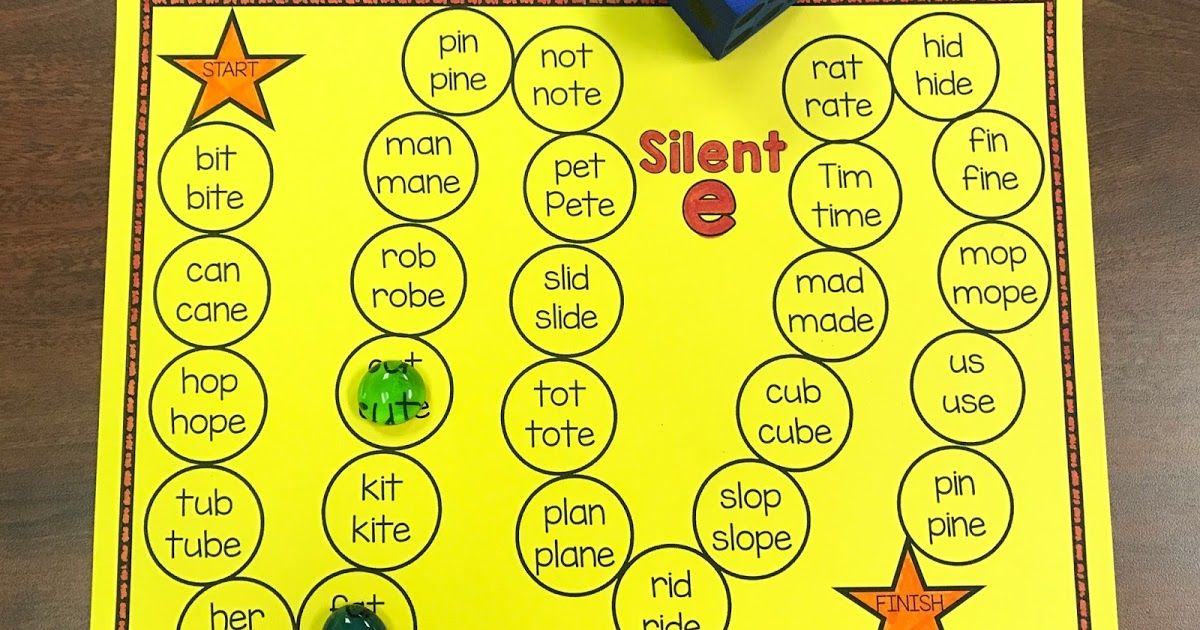

Aside from the alphabet, early phonics is extremely important during this phase.

Children should be learning the relationship between the way a letter looks and its associated sound, beginning with the differences in vowels and consonants.

You'll know your early emergent reader is on the cusp of becoming an emergent reader when they begin to automatically recognize high-frequency words (core vocabulary words).

Also, your almost-emergent readers will be able to read consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words.

2. Emergent Readers

As we mentioned above, emergent readers have learned the alphabet and are beginning to understand early phonics.

They can often read independently with assistance if needed.

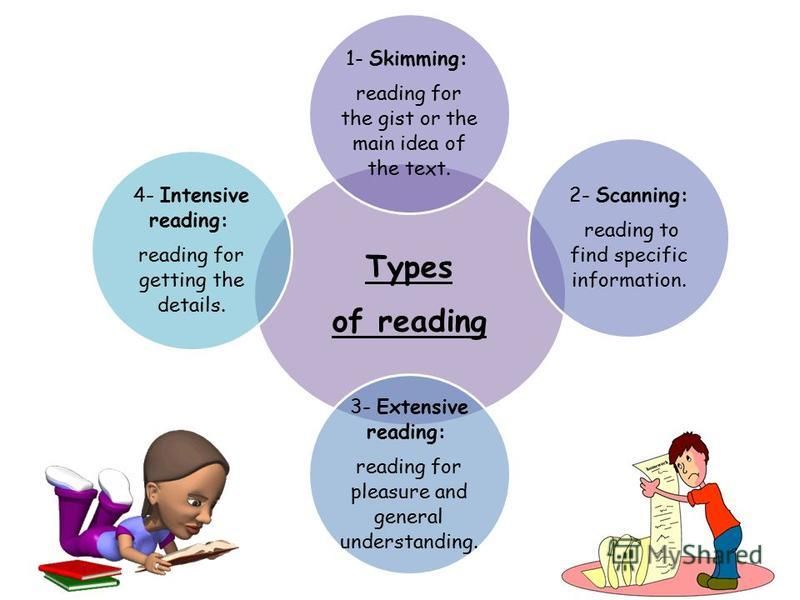

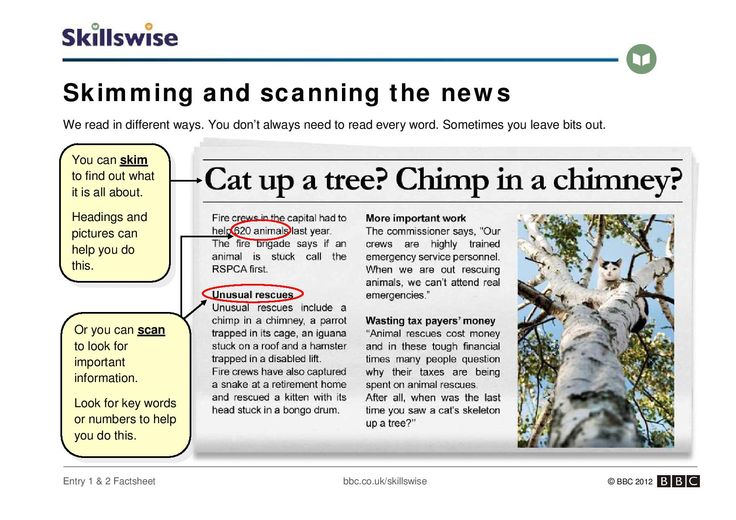

You know your emerging reader is moving on to the next stage if they're starting to comprehend word meaning more automatically instead of focusing on word recognition alone.

3. Early Fluent Readers

This stage is where the magic starts to happen. Early fluent readers are typically between the ages of 7 years and 10 years old.

And at this point, not only can students identify word sounds on their own but they can also comprehend those word meanings independently.

These readers should be given books of different varieties now so that they can appreciate the diversity of the form.

This is a great time to introduce students to genre fiction, an excellent way to excite your early fluent readers with fun, engaging stories.

Complete independence while reading and comprehending is a signal that your early fluent reader is ready to progress.

4. Fluent Readers

If your student or child has made it to this stage, congratulations!

Considering that only 34% of 8th graders achieved National Assessment of Educational Progress "Proficient" reader scores in 2018, this is truly an accomplishment for the record books.

A hallmark of this stage is the ability to read aloud with proper pauses for punctuation.

Fluent readers need absolutely no assistance with reading comprehension. And they are starting to actually understand the meaning behind what they read instead of just comprehending word meanings.

At this point, your fluent reader should begin to choose their own books and form preferences about what they like to read.

This is an exciting time in a student's reading development journey. But it's also an exciting point, in general, since becoming a fluent reader is a major pit stop along the road to true independence.

Special Education for Your Struggling Reader

Are your emergent readers struggling to move on to the next stage of development?

Check out AdaptEd's carefully curated selection of books to engage and excite your child or students today!

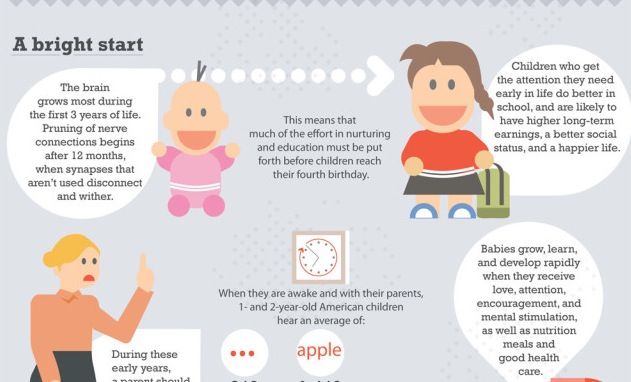

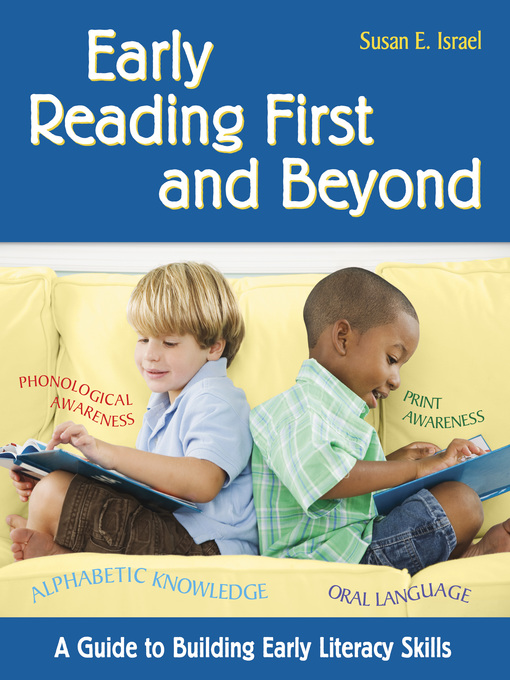

Early Emergent Literacy

Literacy begins at birth and builds on relationships and experiences that occur during infancy and early childhood. For example, introducing a child to books at an early age contributes to a later interest in reading. Reading together while he or she sits on your lap promotes bonding and feelings of trust. The give-and-take nature of babbling, lap games, songs, and rhymes set the stage for sharing favorite picture books. Exposure to logos, signs, letters, and words leads to the knowledge that symbols have meaning. The acquisition of skills such as looking, gesturing, recognizing and understanding pictures, handling books, and scribbling lay the groundwork for conventional reading and writing.

For example, introducing a child to books at an early age contributes to a later interest in reading. Reading together while he or she sits on your lap promotes bonding and feelings of trust. The give-and-take nature of babbling, lap games, songs, and rhymes set the stage for sharing favorite picture books. Exposure to logos, signs, letters, and words leads to the knowledge that symbols have meaning. The acquisition of skills such as looking, gesturing, recognizing and understanding pictures, handling books, and scribbling lay the groundwork for conventional reading and writing.

A love of books, of holding a book, turning its pages, looking at its pictures, and living its fascinating stories goes hand-in-hand with a love of learning." (Laura Bush, 2003)

- Model reading and writing behaviors.

- Embed the use of objects, symbols or words throughout the child's day.

- Incorporate rhythm, music, finger plays and mime games.

- Provide opportunities for handling and exploring reading and writing materials.

- Teach print and book awareness.

- Teach name, name sign and/or personal identifier of child and those the child interacts with on a regular basis.

- Embed literacy learning activities into routines.

Children with combined vision and hearing loss miss out on many of the experiences that happen incidentally for other children, but rich early learning experiences can be provided when families, teachers, and caregivers build trusting relationships with these children, know what their favorite objects and activities are, and recognize their array of communication signals.

As you foster early literacy skills in a child who is deaf-blind, expect to see the child handling and exploring books and writing materials using all of his or her senses (sometimes in unconventional ways). Watch for the child to show signs of anticipation while playing turn-taking games or move in rhythm to songs and music you've listened to together. Allow children to get "up close and personal" to reading and writing items around the house. Point out and talk about signs, symbols, and words you see at school, day care, the grocery store, and out in the community.

Allow children to get "up close and personal" to reading and writing items around the house. Point out and talk about signs, symbols, and words you see at school, day care, the grocery store, and out in the community.

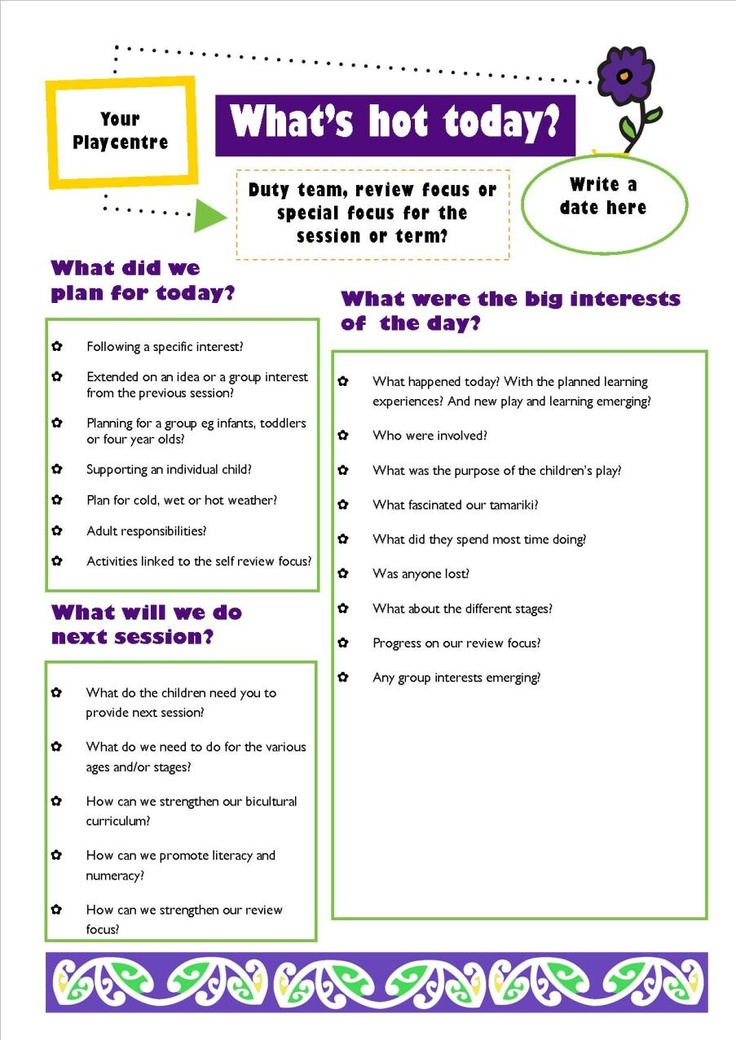

It takes intentional planning to provide meaningful early learning experiences on which to build literacy skills. Following a child's lead provides a wealth of information about what will be most interesting and motivating to a particular child. Incorporating familiar and favorite objects, people, and activities into early learning experiences is essential to achieving positive results.

Literacy skills should not be taught in isolation because they relate to numerous developmental and academic standards often being addressed by a child's educational team. Awareness of interrelated skills assists teams in IEP development and planning holistic instruction.

Attention and Response

Joint attention; response to people, objects, familiar sound/rhythm/movement; response to communication and/or literacy partner; attention/response to informational cues; attention/response to literacy activities

Interaction and Communication

Anticipation; turn-taking; use of pre-linguistic forms of communication (touch, object, gestures and/or cues; ability to access communication and/or literacy partner; active engagement with communication and/or literacy partner; full/partial participation in instructional activities

Sensory

Use of other sensory skills such as smell, taste, movement to gather information; localization to presented sounds; auditory discrimination; visual fixation; eye gaze

Tactile/Motor

Exploration of items using touch; imitation of simple motor tasks; reaches or scans to search for an object; picking up objects; holding objects; pincer grasp; tactile discrimination; eye-hand coordination

Cognitive

Object permanence; one-to-one correspondence; spatial and positional concepts such as front/back, top/bottom; use of emergent symbolic forms (e. g., pictures and/or line drawings)

g., pictures and/or line drawings)

Everyday activities link to literacy

Examples of different ways to use exploration with children.

Using object cues as part of daily routines

Examples of cues used to communicate.

Label ObjectsDevleop print awareness by labeling objects with both pictures and words. You might also add braille. |

RecipeUsing an object recipe embeds literacy into daily living skills instruction. |

Work on literacy while making choicesThis communication flip chart combines pictures and words with colors and contrast customized to the child's needs and interests. Pairing pictures with print sets the stage for moving to print by fading the pictures. |

Work on literacy while playing a gameAn adapted game of Cootie is a great way to work on matching objects to pictures and putting together/taking apart. |

Literacy and Deaf-BlindnessIntroduction to a variety of techniques for creating/adapting books and literacy activities to make them interesting and relevant to students with deaf-blindness. |

Handling BooksThis typically developing eight-month-old is shown handling a book. She has been read to every day of her life. Notice that there are toys around her, but she is more interested in her book. Children with significant disabilities are not often given the opportunity to handle books, which is a very important component of literacy. |

Early Literacy for Students with Multiple Disabilities or Deafblindness

Webcast that includes an introduction to literacy, challenges related to literacy for this population, literacy learning activities and adapted books.

Tangible Symbols

Webcast explaining what tangible symbols are and how they can be used to support communication development in children who are unable to use abstract symbols.

Experience Books

Overview, videos, and FAQs from Washington Sensory Disabilities Services on experience books and how to use them to encourage literacy for children with deaf-blindness and/or multiple disabilities.

Literacy for Persons Who Are Deaf-Blind

Introduction to an expanded view of literacy, written in everyday language and including a variety of practical tips.

Calendar Systems for Young Children with Sensory Impairments

Discusses the developmental considerations connected to creating a meaningful calendar system and strategies for preparing a young child to use one.

Tangible Symbols Systems Primer

Provides basic information about the use of tangible symbol systems, including practical examples, tips from the field and troubleshooting suggestions.

The Path to Symbolism

Easy-to-read overview of how children with significant learning challenges, including deaf-blindness move from early forms of intentional communication to more abstract forms requiring the use of symbols.

Center for Early Literacy (CELL)

Overview of the CELL approach to early literacy learning in home and classroom settings (Literacy-rich environments, Child interests, Everyday literacy activities, and Responsive teaching).

Every Child Is a Potential Reader

Introduction to the importance of literacy for all children with examples of literacy materials and activities including story boxes, literacy kits and assistive technology. (Begins on page 6)

Calendars for Students with Multiple Impairments Including Deafblindness

Written for students who need help structuring and organizing their time and activities through the use of an individualized system. Available for purchase.

Available for purchase.

Tactile Symbols Directory

A directory of tactile symbols used at the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

Early teaching of a child to read, write, count: benefit or harm?

A.A. Davidovich, Ph.D., Associate Professor

Year by year the popularity and number of early education and development schools is growing. Advertising schools "Mom's genius", "Smart baby", "Reading from the cradle", etc. metro cars are full of prints. Most often, reading and counting skills are offered to develop in children of pre-preschool and primary school age. The growth in the supply of such educational services is adequately proportional to the growth in demand: a study carried out within the framework of the student research laboratory "Children with Learning Difficulties in a General Education School" (BSPU named after M. Tank) showed that 80% of children of primary preschool age attend this kind of educational institutions. Several legitimate questions arise:0007

Several legitimate questions arise:0007

— What is the reason for the intensive growth in the number of such educational institutions in the last 6-8 years?

— Is it really expedient to teach a child to read, write, and count at pre-school and early pre-school age? What tasks does it solve?

— What are the negative consequences of early teaching a child to read, write, and count?

The answer to the first question requires an analysis of the cultural and historical context, an appeal to the concepts of "culture of utility" and "culture of dignity", which were introduced by V.I. Vernadsky. Within these coordinates, we, following A.G. Asmolov [1], we consider the problems of the existing education system, including preschool education. nine0007

The real trend in the development of the modern education system in accordance with the principles of the "culture of usefulness" society, and not the declared principles of the "culture of dignity" society, the orientation towards obtaining a "useful member of society" as the end product of educational efforts leads to a reduction in childhood time, intensification of preschool education , the loss of the value of the role-playing game as the leading type of activity that sets the preschool development of a problem-search, creative character. nine0007

nine0007

Orientation of the education system towards a “functional” person leads to the consolidation of the image of a normally developing child as a child who reads, counts, etc. This phenomenon objectifies itself in the requirements that are imposed on a child at the stage of senior preschool age, in the criteria by which his readiness for schooling is assessed, in modified training and development programs in kindergarten, where none of the sections presents gaming activity ( see, for example, "Instructive and methodological letter of the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus for the 2012/2013 academic year. Institutions of preschool education" [2]). nine0007

Parents of children, being partly hostages of the situation, are forced to start teaching the child to read, write, count at preschool and early preschool age in order for him to correspond to the teacher's, psychologist's ideas about normal development. On the other hand, the organization of the child's intellectual and developmental leisure, his visits to circles, schools, studios, etc. significantly minimizes the opportunities for joint activities (playing, reading and discussing books, drawing, modeling, physical activity, just talking) between the parent and the child, saves energy and time resources of parents. The aforementioned study based on preschool institutions revealed the following dominant attitudes among parents of children attending early education and development schools: “The child is busy and I have time for something”, “Let professionals take care of the child, I understand little about this”, “I I pay money in order to be sure that I gave the child the best, did everything for his future”, “I can’t cope with him (with the child), and there he does everything he is told.” nine0007

significantly minimizes the opportunities for joint activities (playing, reading and discussing books, drawing, modeling, physical activity, just talking) between the parent and the child, saves energy and time resources of parents. The aforementioned study based on preschool institutions revealed the following dominant attitudes among parents of children attending early education and development schools: “The child is busy and I have time for something”, “Let professionals take care of the child, I understand little about this”, “I I pay money in order to be sure that I gave the child the best, did everything for his future”, “I can’t cope with him (with the child), and there he does everything he is told.” nine0007

Parents rarely play role-playing games with their children, analysis of the research materials allows us to conclude that if parents play with children, then in 70% of cases these are games according to the rules, mostly didactic (“Nikitin’s Cubes”, “Adding puzzles”, “Pick the right word”, “Logic chains”, various options for computer training programs, etc. ).

).

This situation is aggravated (the shift of the plot-role-playing game from the position of the leading type of activity) by another negative cultural phenomenon, designated by the authors as “the disappearance of courtyard culture” [3]. The transfer of any cultural activity can be carried out through the direct involvement of a person in this activity, its observation (an example of activity) and special training (where the activity is divided and transferred to the individual element by element). Since play activity in our society belongs to children, it also has a specific living carrier (carrier of play culture) - this is a group of children of different ages. As long as children's groups of different ages exist, play can be passed on in a spontaneous, traditional way from one generation of children to another. This is the natural transmission mechanism of the game. Everyone had to watch the kids, who can stand for a long time and watch what is being done on the playground, how older children play. Gradually, small children are drawn into a common game: at first, as executors of orders, instructions from older children who already know how to play, who lack partners, and then they become full members of the playing group. Naturally folded play groups include children of different ages (from teenagers to preschoolers) with different play experiences. The renewal of the composition of such groups occurs gradually - the kids are drawn in and gaining playing experience, and older children, growing up, participate less and less in the life of the play group. This gradualness ensures the continuity of the gaming culture, its preservation. The gradual disappearance of the “yard culture” also led to a decrease in the share of the traditional way of transmitting game culture, described above [3]. nine0007

Gradually, small children are drawn into a common game: at first, as executors of orders, instructions from older children who already know how to play, who lack partners, and then they become full members of the playing group. Naturally folded play groups include children of different ages (from teenagers to preschoolers) with different play experiences. The renewal of the composition of such groups occurs gradually - the kids are drawn in and gaining playing experience, and older children, growing up, participate less and less in the life of the play group. This gradualness ensures the continuity of the gaming culture, its preservation. The gradual disappearance of the “yard culture” also led to a decrease in the share of the traditional way of transmitting game culture, described above [3]. nine0007

Thus, the reasons why play loses its character as the leading type of activity at preschool age can be schematically outlined as follows: we don't play in the garden because we are learning; we do not play with parents, because there is no time, opportunities, motivational readiness of the parent for "jointness"; we do not play with other children, because there is nowhere, older children are busy with intensive studies, etc.

An empirical study conducted in May 2012 by 4th-year student D. Gurinovich on the basis of one of the kindergartens in Minsk showed that the majority (75%) of older preschool children do not have the necessary level of formation of motivational readiness for schooling. In addition, in the course of this study, it was revealed that the game of modern preschoolers is characterized by a number of features that are not characteristic of a full-fledged game as the leading type of activity at preschool age: the poverty of the plot, the reduction of the game to the repetition of actions of the same type, the lack of interaction that reflects real relationships between people, small the number of substitute objects, the rules of the game, the underdevelopment of the imaginary situation, etc. These results confirm the data obtained in the course of a number of other modern studies (E. O. Smirnova, I. A. Ryabkova, etc.). Thus, along with the death of the child of the role-playing game, the full-fledged conditions for the formation of motivational readiness for schooling also disappear. In many ways, this problem is a consequence of the simplification of the concept of a child's readiness for schooling: understanding it only as the accumulation of learning skills. nine0007

In many ways, this problem is a consequence of the simplification of the concept of a child's readiness for schooling: understanding it only as the accumulation of learning skills. nine0007

Obviously, the benefit of early teaching a child of sign activities for his further education at school (and this is the main task declared by adherents of early education systems) is more than doubtful. Let us turn to one more aspect of the problem, connected with the neuropsychological level of analysis of the situation of a child's early education.

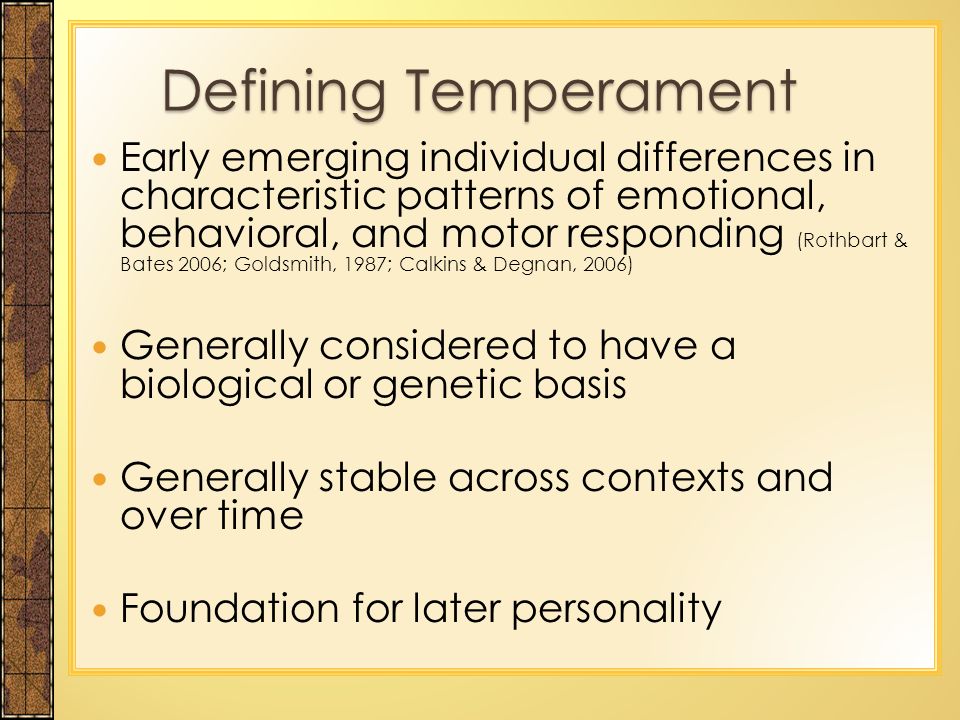

The central concept of childhood neuropsychology is the concept of developmental heterochrony. Various structures of the child's brain, their interaction, and, consequently, the brain systems of which they are the morphological basis, reach their maturity at different ages of the child. These functional systems are formed in stages, unevenly, in accordance with the changing forms of the child's interaction with the environment. Restructuring and complication of individual functional systems proceed in a certain chronological sequence. Each of the mental functions has its own chronological formula, its own cycle of development, that is, a sensitive period of its rapid formation and a period of relative slowness of formation [4]. nine0007

Each of the mental functions has its own chronological formula, its own cycle of development, that is, a sensitive period of its rapid formation and a period of relative slowness of formation [4]. nine0007

Thus, from a neuropsychological point of view, sensitivity means the achievement by certain brain centers of a level of maturity at which their sensitivity to the corresponding environmental influences sharply increases [5]. In the presence of adequate stimulation of these centers, the rate of their achievement of functional maturity accelerates, which, in turn, leads to the active formation of those links of mental functions that are provided by these centers. Obviously, the nature of the interaction between brain morphogenesis and social influences is two-sided: the maturation process is determined not only by the genetic program, but also by environmental influences. For the appearance of a certain function, a certain degree of maturity of the nervous system is required, on the other hand, the functioning itself affects the maturation of the corresponding structural elements [6]. nine0007

nine0007

Now let's turn to the logic of the development of the structural and functional organization of the child's brain. For these purposes, we use the concept of A.R. Luria about the three functional blocks of the brain.

Table 1Structural and functional model of the brain as a substrate of

mental activity [7]

Teaching a child to write, read, and count appeals mainly to the second and third functional block of the brain (FBM). An example is the model of the functional composition of T.V. Akhutina [8], the neuropsychological structure of the intellectual activity of counting [9].

Table 2Neuropsychological structure of the intellectual activity of counting

Correlation of the data given in Tables 1 and 2 allows us to conclude that teaching reading, writing, counting in the pre-preschool and early preschool age violates the law of heterochrony, since it is realized in that the period when the second and third FBM have not yet reached their morphological and functional maturity. The load on the still immature structures of the child's central nervous system adversely affects the work of the first (energy) functional block of the brain, which has already completed its development and now works "for three". As a result, the child learns to read (write, count), but at the same time:

The load on the still immature structures of the child's central nervous system adversely affects the work of the first (energy) functional block of the brain, which has already completed its development and now works "for three". As a result, the child learns to read (write, count), but at the same time:

- the child may not sleep well, he may have symptoms of enuresis, he may often suffer from somatic diseases, various dysfunctions associated with the functioning of the endocrine system, etc. are possible;

- the regulation of various emotional states, as well as motivational processes, may be disturbed in him - the child is overly excitable, capricious, etc.

The following logical question arises, which is directly related to the above concept of sensitivity: “Why, why waste energy, time, motivation, energy resources of the central nervous system of a child of preschool age for teaching him to read (writing, counting)?” Based on the concept of sensitivity and common sense, it becomes clear that if at three years it takes a year and a half to systematically teach a child to read, then at five or six years it takes a month, at most, two. Many of us went to school without knowing how to read or count, but everything was resolved successfully in the first quarter of the first grade. nine0007

Many of us went to school without knowing how to read or count, but everything was resolved successfully in the first quarter of the first grade. nine0007

Negative, from a neuropsychological point of view, the consequences of early teaching a child to read, write, and count are not limited to dysfunctions in the work of the first functional block of the brain.

A child of pre-preschool and early preschool age who attends developmental classes related to learning to read, write, and count finds himself in a situation where he is forced to carry out activities in an "unmotivated" environment. It is hard to disagree that a one-year-old child is hardly interested in reading a book on his own. It's hard to imagine that a two-year-old would trade sandbox digging and ball games for tracing letters or folding counting sticks. The productivity of the child's activity in such a situation is supported by a close external motive: praise from a parent, teacher, competitive motive, etc. These superficial, external motives, a program of activity “alien” to age, replace curiosity, a thirst for discovery, independent cognitive activity, when a child learns letters because he wants to read a book or begins to draw squiggles because he wants to study at school as soon as possible, etc. In fact, we are realizing a task that is paradoxical in ontogenetic terms: first, an activity, and then a motive is applied to it. The child does not have the opportunity to independently program, control and organize his own activities in a situation of solving tasks adequate to his age. Rigid external regulation does not allow control to become self-control, and organizations - self-organization. In the future, such children expect from an adult the usual external regulation of cognitive, educational activities, often they are not able to independently formulate the goal of the activity, deploy the program and exercise independent control over its course. Having come to the first grade, such children are again forced to implement learning activities in a "non-motivated" environment, because they are offered already well-known material - a task that does not involve cognitive motivation, search, heuristic activity. nine0007

In fact, we are realizing a task that is paradoxical in ontogenetic terms: first, an activity, and then a motive is applied to it. The child does not have the opportunity to independently program, control and organize his own activities in a situation of solving tasks adequate to his age. Rigid external regulation does not allow control to become self-control, and organizations - self-organization. In the future, such children expect from an adult the usual external regulation of cognitive, educational activities, often they are not able to independently formulate the goal of the activity, deploy the program and exercise independent control over its course. Having come to the first grade, such children are again forced to implement learning activities in a "non-motivated" environment, because they are offered already well-known material - a task that does not involve cognitive motivation, search, heuristic activity. nine0007

Later, these children often show learning difficulties [10]. Often they say about such children: “He can study, but does not want to.” Violations of the motivational component of educational activity are combined with violations of volitional regulation. According to our data, the number of such students among other children with learning difficulties is 18% [9].

Often they say about such children: “He can study, but does not want to.” Violations of the motivational component of educational activity are combined with violations of volitional regulation. According to our data, the number of such students among other children with learning difficulties is 18% [9].

A.V. Semenovich unites these children into the syndromic group "Children with functional underdevelopment of the frontal parts of the brain" [11]. As the main radical of mental disorders, A.V. Semenovich highlights "... the lack of self-regulation, programming and control over the course of one's own activity" [12, p. 26]. The famous neurologist V.I. Garbuzov defines such a variant of deviant development as one of the variants of mental infantilism, which is entirely due to improper upbringing associated with hyperprotection on the part of parents, excessive demands on the achievements of the child, and hypersocialization [13]. Violations that occur as a result of inadequate educational influences are not only functional, but also, over time, functional-organic in nature. As we have pointed out above, the development of the brain structure-function relationship is a two-vector process of interaction: not only does function depend on structure, but brain architecture also depends on the experience of functioning. Inadequate external, educational influences lead to deviations or delays in the development and maturation of nerve cells. This group of children suffers from functional systems that have a long “path” of ontogenetic development – formations of the frontal parts of the cerebral cortex [ibid.]. nine0035 The stated positions are certainly problematic and require discussion. Nevertheless, one cannot deny the obvious negative consequences of the change in the goals and values of preschool education, which were cited above. “In reality, in any social systems, both tendencies are simultaneously realized through education: both to preserve and to change systems. The whole question is to find such an optimal combination of them, which, while providing the national standard of education inherent in this civilization, at the same time would open up the greatest opportunities for the development of the child’s personality, and not his cognitions” [1, p.

As we have pointed out above, the development of the brain structure-function relationship is a two-vector process of interaction: not only does function depend on structure, but brain architecture also depends on the experience of functioning. Inadequate external, educational influences lead to deviations or delays in the development and maturation of nerve cells. This group of children suffers from functional systems that have a long “path” of ontogenetic development – formations of the frontal parts of the cerebral cortex [ibid.]. nine0035 The stated positions are certainly problematic and require discussion. Nevertheless, one cannot deny the obvious negative consequences of the change in the goals and values of preschool education, which were cited above. “In reality, in any social systems, both tendencies are simultaneously realized through education: both to preserve and to change systems. The whole question is to find such an optimal combination of them, which, while providing the national standard of education inherent in this civilization, at the same time would open up the greatest opportunities for the development of the child’s personality, and not his cognitions” [1, p. 52]. nine0007

52]. nine0007

Literature

1. Asmolov, A.G. Education in Russia: from a culture of utility to a culture of dignity / A.G. Asmolov, A.M. Kondakov // Notebooks of the International University: scientific papers. / Ed. house Intl. university in Moscow; ed. V.A. Nikonov. - Moscow, 2004. - V.2. - P. 48-56.

2. Instructive-methodical letter of the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus for the 2012/2013 academic year. Institutions of preschool education: approved. Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Belarus V.A. Budkevich 06/28/2012. / Praleska.– 2012– No. 7.– P. 28-37. nine0007

3. Osorina, M.V. The secret world of children in the space of the world of adults / M.V. Osorina. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2011. - 368 p.

4. Mikadze, Yu.V. Neuropsychology of childhood: textbook. allowance / Yu.V. Mikadze. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 1994. - 288 p.

5. Glozman, Zh.M. Neuropsychology of childhood: textbook. allowance / Zh.M. Glozman. – M.: Academy, 2009.– 272 p.

– M.: Academy, 2009.– 272 p.

6. Tsvetkova, L.S. Scientific foundations of neuropsychology of childhood / L.S. Tsvetkova // Actual problems of neuropsychology of childhood: textbook. allowance / L.S. Tsvetkova [and others]; ed. L.S. Tsvetkova.– M.: Moscow Psychological and Social Institute, 2001.– P. 16–84. nine0007

7. Luria, A.R. Fundamentals of neuropsychology: textbook. allowance / A.R. Luria. - M .: Publishing Center "Academy", 2003.- 384 p.

8. Akhutina, T.V. Difficulties in writing and their neuropsychological diagnostics / T.V. Akhutina // Writing and reading: learning difficulties and correction / T.V. Akhutina [and others]; ed. ABOUT. Inshakova.– M.: Mosk. Psychological and social institute.– P. 7-20.

9. Davidovich, A.A. Assimilation of the concept of number and counting operations by first-graders with neuropsychological syndromes of deviant development: dis. … cand. psychol. Sciences: 19.00.10 / A.A. Davidovich. - Minsk, 2007. - 129 p.

10. Akhutina, T.V. Overcoming learning difficulties: a neuropsychological approach / T.V. Akhutina, N.M. Pylaeva. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2008. - 320 p.

Akhutina, T.V. Overcoming learning difficulties: a neuropsychological approach / T.V. Akhutina, N.M. Pylaeva. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2008. - 320 p.

11. Semenovich, A.V. Neuropsychological syndromes of deviant development / A.V. Semenovich // Tauride Journal of Psychiatry. - 1999. - T. 3. - No. 3. - P. 15-21.

12. Semenovich, A.V. Neuropsychological diagnostics and correction in childhood: textbook. allowance for university students / A.V. Semenovich. - M .: Academy. - 2002. - 232 p. nine0007

13. Garbuzov, V.I. Nervous children: doctor's advice / V.I. Garbuzov.– L.: Medicine, 1990.– 186 p.

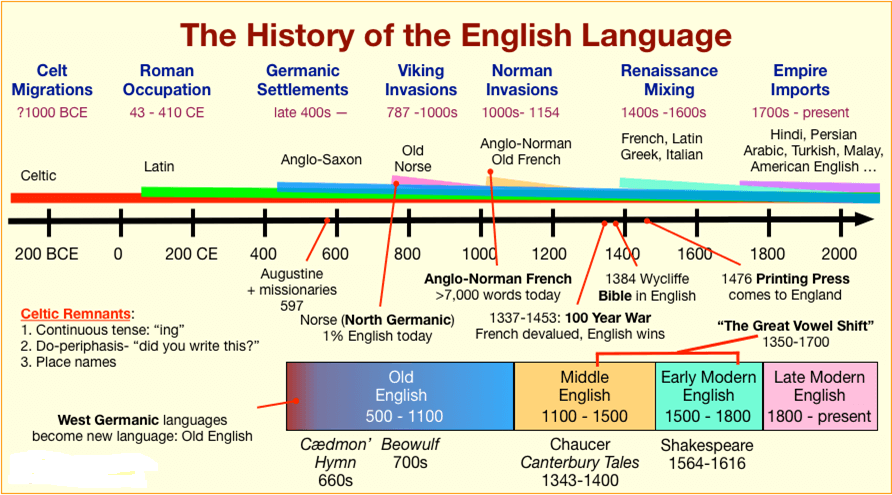

On the dangers of early learning to read: Why is prematurely developed phonemic hearing bad?

Up to now I have thought that early learning to read (before the age of four or five), although useless, can still not bring any harm. Therefore, if it so happened that parents, having become infected with the ideas of early development, start reading from the cradle, then there is no big trouble in this. Parental impatience is quite understandable: what if, in fact, Doman is right - and it is already hopelessly late to teach a seven-year-old child to read - just as hopelessly as teaching to speak? Let Doman not give any experimental confirmation of his theory (except for experiments on rats), but there is logic in his reasoning! It is so? nine0007

Parental impatience is quite understandable: what if, in fact, Doman is right - and it is already hopelessly late to teach a seven-year-old child to read - just as hopelessly as teaching to speak? Let Doman not give any experimental confirmation of his theory (except for experiments on rats), but there is logic in his reasoning! It is so? nine0007

My confidence in the harmlessness of early reading was greatly shaken after meeting Lev Sternberg, the author of the rebus method, with the help of which he taught more than a thousand children of kindergarten age to read. The fact is that Sternberg strongly discourages reading with children under the age of five, and he considers classes with kids under the age of four to be completely unacceptable. This is the rarest case when a person publicly defends a point of view that is in blatant contradiction with his mercantile interests. For that alone, she deserves to be taken seriously. nine0007

In contrast to Doman, Sternberg argues that, according to his observations, children who are prematurely taught to read usually lose their apparent advantage after two or three years and become noticeably dumber than their peers. They have more problems with logical thinking, foreign languages are more difficult for them and, paradoxically, they show less interest in reading.

They have more problems with logical thinking, foreign languages are more difficult for them and, paradoxically, they show less interest in reading.

— Where is the proof? I yelled indignantly, immediately remembering that I started teaching my eldest son to read when he was two years old. Where is the experimental evidence? nine0007

My interlocutor did not have any experimental confirmation, but he readily shared with me the theoretical arguments substantiating his correctness. I must admit that Sternberg's theory is no less logical than Doman's, and perhaps even more so. I present it in a brief free retelling.

As you know, teaching a small child letters is not a problem. Difficulties begin when we write two letters in a row - for example, "ba" - and ask the baby to pronounce the resulting syllable together. It turns out that this task is not up to him. The question is why? What, it would seem, is difficult here? nine0007

Let's ask ourselves a question: why did we ask the child to read the syllable "ba" and, say, not the syllable "be"? Understandable why. The child will certainly not cope with the syllable "be". Indeed, in the syllable "be" the letters "b" and "e" are pronounced differently from how they are read when they stand separately, by themselves. In the syllable "be", the letter "b" becomes soft, and the initial iotation disappears from the letter "e". No matter how quickly we pronounce the two letters “b” and “e” one after another, they will not merge into the syllable “be”.

The child will certainly not cope with the syllable "be". Indeed, in the syllable "be" the letters "b" and "e" are pronounced differently from how they are read when they stand separately, by themselves. In the syllable "be", the letter "b" becomes soft, and the initial iotation disappears from the letter "e". No matter how quickly we pronounce the two letters “b” and “e” one after another, they will not merge into the syllable “be”.

But the situation is exactly the same with the syllable "ba"! Let's try to quickly pronounce the sounds in a row, transmitted by the separate letters "b" and "a". Do they merge into one syllable "ba"? Nothing like this! nine0007

For those who have mastered phonetics well from the school course, this result should seem unexpected. In school, we are told that the graphic symbol "b" represents the sound [b], and the graphic symbol "a" represents the sound [a]. Therefore, it would seem that if we read the letter “b” first, and then “a”, then it should sound like [ba]. Why doesn't this actually work?

Why doesn't this actually work?

Let's listen more closely to the sound we make when we read the letter "b". Better yet, take a microphone and record this sound in an audio editor:

We see that our sound consists of two parts, the first part is quieter, the second is louder, and each with its own special sound wave pattern. Listening to these parts separately, it is easy to make sure that by ear none of them even remotely resembles the sound [b]. It turns out that the sensation of sound [b] is created by nothing more than a transition from one part to another.

And now let's read and write down the syllable "ba" in the audio editor:

Isn't it true, the picture turned out surprisingly similar? Here are the same two parts: one is quieter, the other is louder, only the wave pattern of the second part is not the same as before. (However, when I was preparing this picture, I deliberately pronounced the syllable "ba" very briefly, so that the duration of the sound of both recordings was approximately the same. )

)

Thus, the single letter "b" and the letter combination "ba" generate sounds of exactly the same structure. But if in the sound generated by two letters “ba”, we can distinguish a consonant and a vowel component, then the sound generated by a single letter “b” should have exactly the same composition. Indeed, voicing the letter “b”, we end, albeit with a short, but still almost unhindered exhalation, which has all the formal features of a vowel and resembles something between [o] and [s]. A hundred years ago, in the Russian alphabet, to convey this vowel, there was a special letter, which was called "er" and was designated as "b". If we lived in those days, we would not write "b", but "b". However, during the post-revolutionary reform of Russian spelling, the letter "b" was deprived of its main role and renamed into a "hard sign". nine0007

As for spelling, this is, in principle, a conditional thing: as we agree, we will write. But when we want to display the pronunciation of a word as a transcription, here we must be as precise as possible. Therefore, the sound transmitted by the free-standing letter "b" should be written as [b]. It is important to note that although we needed two characters to record this sound, nevertheless it is one indivisible sound: we do not pronounce [b] and [b] separately, but only together - [b].

Therefore, the sound transmitted by the free-standing letter "b" should be written as [b]. It is important to note that although we needed two characters to record this sound, nevertheless it is one indivisible sound: we do not pronounce [b] and [b] separately, but only together - [b].

But if [b] is an indivisible sound, then [ba] is also an indivisible sound. We do not tear [b] from [a] in the same way as we do not tear [b] from [b]. Now it remains to find out what happens when we read the letter "a" by itself. Let's use the microphone again and look at the result in the audio editor.

This time the sound does not split into two parts. The sound wave pattern is almost the same everywhere. And yet, there is no need to talk about complete homogeneity, because the amplitude of the sound does not remain constant. If you listen carefully, it turns out that a sharp increase in amplitude at the very beginning of the recording is perceived by our ear as a slight click. This click is heard especially clearly (and not only heard, but also felt) if you try to read the letter "a" in a whisper. nine0007

nine0007

Scientifically, this click is called a “glottal stop”, and for those who know at least a little German, it is also known as a “hard attack” ( Knacklaut ). Perhaps the easiest way to feel what it is, on the example of the words "ay-ay-ay" and "oh-oh-oh." Usually we pronounce these interjections together: they sound as if they were written “a-ya-yay!” and “oh-oh-oh!”. Here the glottal stop is present only in the very first "ai" and in the very first "oh". But if you pronounce all subsequent “ay” and “oh” in the same way as the very first ones, then we get: “ay! ouch! ouch! and “oh! oh! oh!". Isn't it true that adding a glottal stop radically changes the sound of a word? nine0007

Some languages have special symbols for the glottal stop: for example, the letter א (aleph) in Hebrew or the icon ء (hamza) in Arabic. Linguists consider the glottal stop to be a full consonant. In the international phonetic alphabet, it corresponds to the symbol "ʔ". Thus, when we read the stand-alone letter "a", we pronounce one indivisible sound, which is conveyed by two characters [ʔa].

Thus, when we read the stand-alone letter "a", we pronounce one indivisible sound, which is conveyed by two characters [ʔa].

What then do the phonetic symbols taken by themselves, such as [b] and [ʔ], [a] and [b] mean? These symbols stand for abstract "halves of sounds", which are scientifically called phonemes. It is abstract phonemes (and not letters or sounds at all) that are consonants and vowels. Each speech sound has a consonant component, which is characterized by a consonant phoneme ([b], [ʔ], etc.), and a vowel component, which is characterized by a vowel phoneme ([a], [ъ], etc.). Similarly, the situation is with musical sounds displayed on the letter in the form of notes. Each note is defined by pitch and duration, two abstract characteristics that by themselves, one without the other, do not exist. nine0007

Now it is clear why a small child is not able to merge the letters "b" and "a" into one syllable "ba". Because the sounds [b] and [ʔa] in principle cannot merge into the sound [ba]. It is as if we played a half note "F" and a quarter note "A" to a child and expected him to sing the half note "A" to us in response. This requires a sufficiently developed abstract thinking, the ability to manipulate the "halves of sounds" that do not actually exist, and this is still beyond the power of the kids.

It is as if we played a half note "F" and a quarter note "A" to a child and expected him to sing the half note "A" to us in response. This requires a sufficiently developed abstract thinking, the ability to manipulate the "halves of sounds" that do not actually exist, and this is still beyond the power of the kids.

Traditional methods of teaching reading, designed for children of six or seven years of age, rely entirely on the ability of students to think abstractly. This ability is further developed with the help of the so-called phonemic hearing. An adult says to a child (who cannot yet read):

- I will now name two words, and you will clap your hands immediately after the one that begins with the sound "b". Listen carefully: "stick - beam."

According to the plan of an adult, the child should clap his hands after the word “beam”. nine0007

Further, more. An adult asks:

- What sound does the word "bank" begin with?

To this a child who has become proficient in phonemic hearing must answer:

— From the sound "b".

Such activities with a child are so commonplace that we do not notice how unnatural they are. Indeed, in reality, the word "beam" does not begin at all with the sound that is transmitted by the free-standing letter "b". The word [beam] begins with a single and indivisible sound [ba], and there is no sound [b] in this word at all. In fact, we teach the child to "hear" in our speech those sounds that we do not pronounce. nine0007

However, most children are smart enough to know what to say to please adults. Very little time passes - and the child, without blinking an eye, begins to assert that the word [bank] begins with the sound [b]. Phonemic hearing is considered to be successfully formed when a child “learns to hear” about four dozen sounds in Russian speech - such as [ʔа], [bъ], [b], [vb], [v], etc. - and not hear anything else . For example, in the word “bank” a good student hears the sounds [b], [ʔa], [nb], [kъ] and again [ʔa], and in the word “ball” - [m], [ʔa], [ch ], [ʔi] and [къ]. nine0007

nine0007

This phonemic awareness is said to be very useful for reading and writing. But at the same time, this is nothing more than the “ability to hear” what is not, and not to notice what is. Phonemic hearing is a grossly distorted perception of reality in favor of some artificial scheme. All the variety of human speech in a trained child is reduced to a limited set of standard sounds. This set includes only those sounds that can be transmitted by a single letter of the Russian language or by a pair of "consonant" + "ь". (At the same time, it should be noted that not every letter generates a standard sound. So, the separate letters “b” and “b” cannot be voiced, but in the iotized vowels “e”, “e”, “yu”, “I” of the child they teach to hear not one indivisible sound, but two at once - respectively [yy-ʔe], [yy-ʔo], [yy-ʔy] and [yy-ʔa]). nine0007

All this is as if glasses with filters were put on a child's eyes, which out of the whole variety of colors pass only four dozen, and even then - in a very distorted form. Such a child, instead of a full-fledged picture:

Such a child, instead of a full-fledged picture:

, begins to see something like this:

the letters "b" and "a" into the syllable "ba". Some children, however, do not lend themselves to such learning at all and stubbornly refuse, for example, to recognize that the word [bank] begins with the sound [b]. Well, they don't hear that sound there and that's it. These children are called dyslexics. They experience great difficulty in learning to read by traditional methods, although they may be higher in intelligence than their peers. School teachers usually send them to speech therapists so that they can convince them with their special professional methods that there is a sound [b] with the word [bank]. nine0007

Phonemic awareness is specific to each particular language. Therefore, having learned to decompose all words into sounds corresponding to the Russian alphabet, the child largely loses the ability to correctly perceive and reproduce foreign speech. He does not distinguish between the English "shit" and "sheet", and instead of the German "natürlich" he says "natürlich".

However, the abuse of the natural order of things is not limited to phonemic hearing alone. As soon as the child begins to grasp the logic underlying the lettering of words, it immediately turns out that this logic is violated at every step. It is written "him", but for some reason it is necessary to read "evo"; “what” is written, but it is necessary to read “what”, etc. nine0007

It is clear that we are all hostages of the culture in which we live. In our writing, letters do not convey sounds, but "halves of sounds" - phonemes, and very inaccurately and inconsistently. Whether we like it or not, sooner or later, when we begin to teach a child to read and write, we will be forced to spoil his innate speech hearing, replacing it with phonemic hearing. Sooner or later we will have to sow confusion in the child's mind by developing abstract logical thinking in the child and at the same time making it clear that logic is a very unreliable thing. The whole question is when exactly to do it: sooner or later? nine0007

The answer suggests itself: better later than , than before , and best of all shortly before the child really needs to read books. Modern methods - such as the rebus method - make it possible to teach reading in warehouses simply quickly: two or three months for a five-six-year-old child is enough. At the same time, children easily catch up and overtake their peers who were taught to read earlier.

Modern methods - such as the rebus method - make it possible to teach reading in warehouses simply quickly: two or three months for a five-six-year-old child is enough. At the same time, children easily catch up and overtake their peers who were taught to read earlier.

And, in fact, what kind of reading is this, which is demonstrated by a three-year-old reading? The kid still sorely lacks life experience in order to restore the richness of human speech, with all its intonations, emotions, humor - in a word, with everything that makes it interesting from a set of soulless symbols. This is completed for him in his imagination by benevolent adult listeners - mainly mothers and grandmothers. For the kid himself, reading is an incomprehensible, tedious activity that manages to get bored many times by the age when other children also learn to read and write and, in the wake of primary enthusiasm, begin to show interest in books. nine0007

Dubious acquisitions of early learning to read quickly disappear, and the losses may be irreplaceable. There is nothing good in forcing a child from the cradle to perceive the world through a filter of very approximate abstract schemes, which are the sequences of letters in relation to living speech. Let the child first listen well to adults, let him learn to speak well himself, and only then it already makes sense to structure his speech experience with the help of abstractions. Only then will the schemes in his mind be filled with full content. And if the filter is applied prematurely, then all the richness and variety of the sounds of human speech will simply pass by the child's ears. Thus, early learning to read is unambiguously harmful: it does not contribute to the development of the mind, but, on the contrary, to the stupidity. nine0192

There is nothing good in forcing a child from the cradle to perceive the world through a filter of very approximate abstract schemes, which are the sequences of letters in relation to living speech. Let the child first listen well to adults, let him learn to speak well himself, and only then it already makes sense to structure his speech experience with the help of abstractions. Only then will the schemes in his mind be filled with full content. And if the filter is applied prematurely, then all the richness and variety of the sounds of human speech will simply pass by the child's ears. Thus, early learning to read is unambiguously harmful: it does not contribute to the development of the mind, but, on the contrary, to the stupidity. nine0192

These are, in general terms, the arguments that I heard from Lev Sternberg. I recounted them as I understood them, and if I distorted something, it was not out of malicious intent, but because, in general, all ideas, migrating from one head to another, tend to be distorted.

In my opinion, the colors here are somewhat thickened. Still, youngsters are now being taught to read not according to traditional school methods, but according to Zaitsev's Cubes. Zaitsev taught us to break words not into letters, but into warehouses.

That is not so:

E-t-a s-t-r-o-c-a r-a-z-b-i-t-a n-a b-u-k-v-s.

And so:

E-ta s-t-ro-ka ra-z-bi-ta on s-k-la-dy.

Accordingly, if you spell it, it turns out

[ʔe-t'-ʔa s-t-r-ʔo-k'-ʔa r'-ʔa-z-b-ʔi-t'-ʔa n'-ʔa b'-ʔu- k-v-ʔy].

And if by warehouses, then -

[ʔe-ta s-t-ro-ka ra-z-bi-ta on s-k-la-dy].

Each warehouse is considered one indivisible symbol, and, as it is easy to see, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the Zaitsev warehouses and the single indivisible sounds of Sternberg. In order to learn how to read and write in warehouses, you need not phonemic hearing, but “warehouse”. In the classroom for the development of warehouse hearing, an adult should offer the child, obviously, such tasks:

- I will now say two words, and you will clap your hands immediately after the one that begins with the "ba" warehouse.

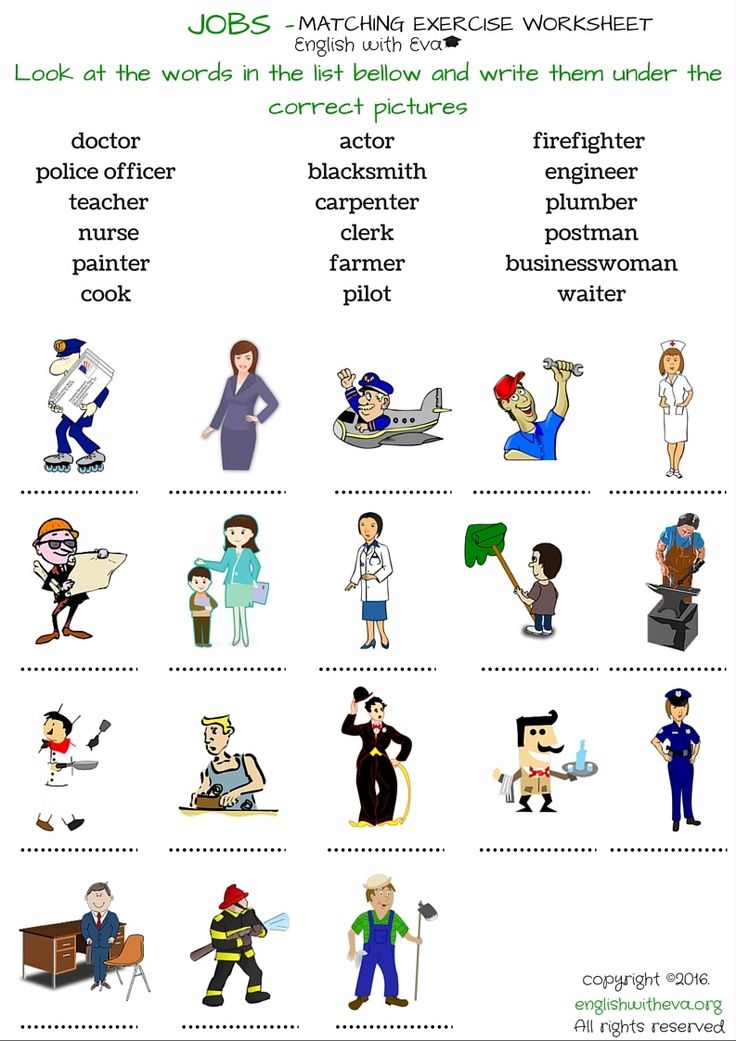

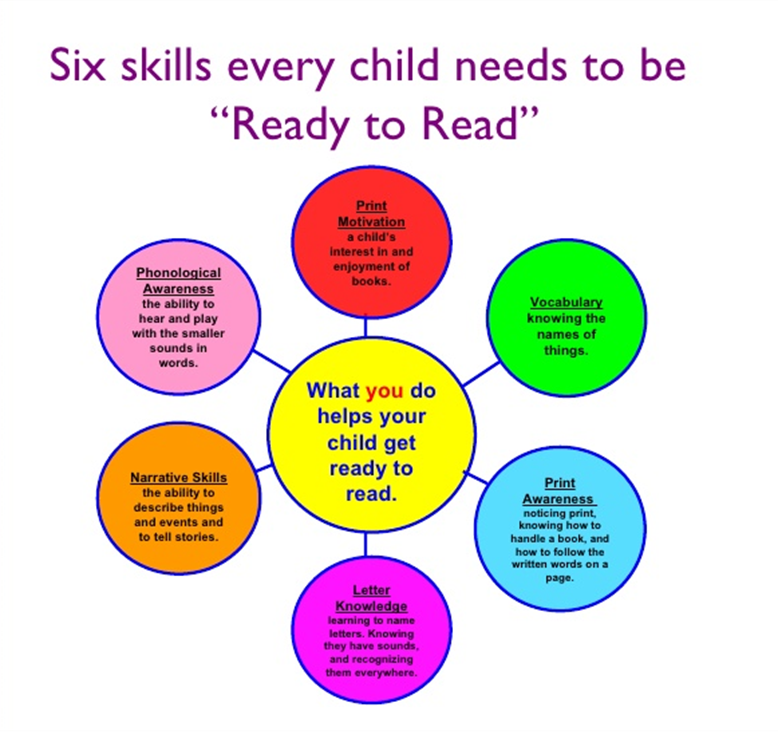

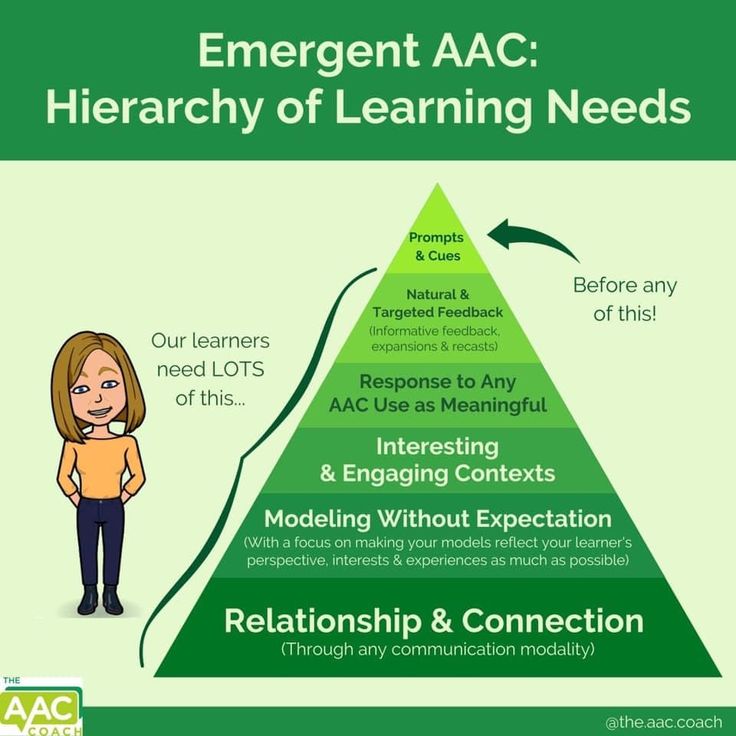

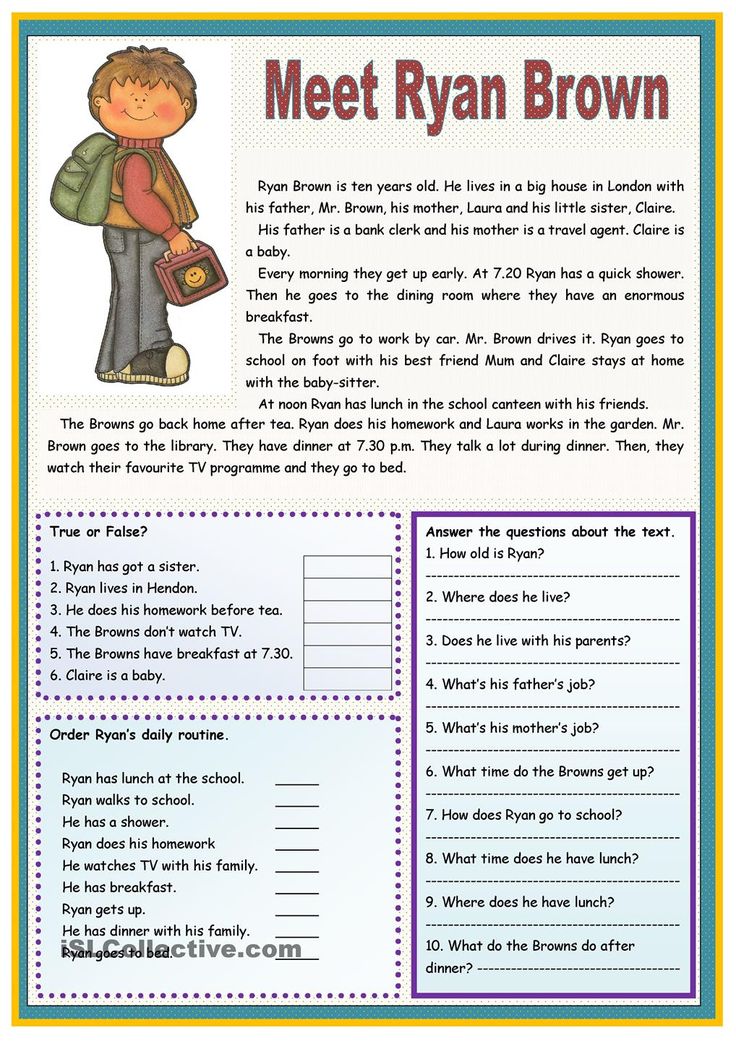

These are skills that help children learn that words represent objects, figure out new words and form sentences.

These are skills that help children learn that words represent objects, figure out new words and form sentences.