Emergent writer definition

Emergent Writing | ECLKC

Emergent Writing

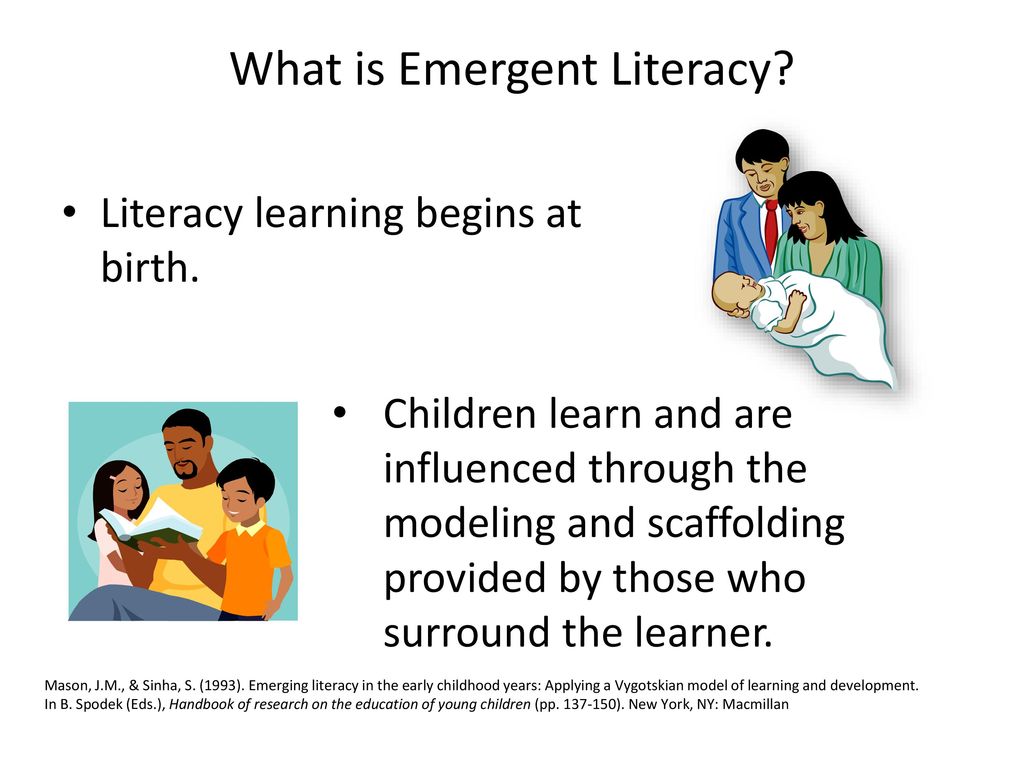

Narrator: Welcome to this presentation of the 15-minute In-Service Suite on Emergent Writing. This presentation describes what emergent writing looks like in young children and shares practical ways that you can begin to support emergent writing at home and in early childhood programs.

The framework for effective practice, or house framework, helps us think about the elements needed to support children's preparation and readiness for school. The elements are the foundation, the pillars, and the roof. When connected to one another, they form a single structure that surrounds the family in the center, because as we implement each component of the house in partnership with parents and families, we foster children's learning and development.

Implementing research-based curricula and effective teaching practices helps support children as they develop the skills necessary to engage in emergent writing. This presentation on emergent writing is one in a series of modules designed to help adults support young children as they learn positive behaviors, develop skills in STEAM, math, and writing, and engage in dramatic play.

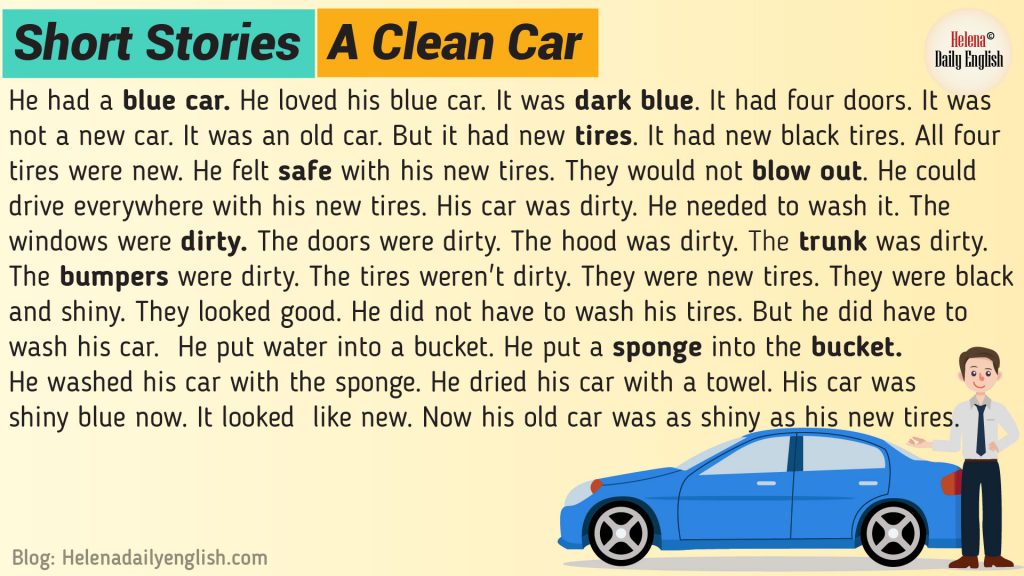

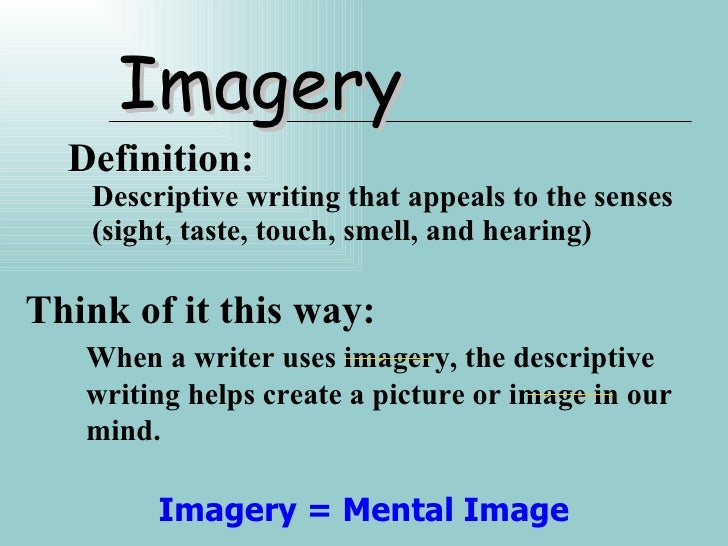

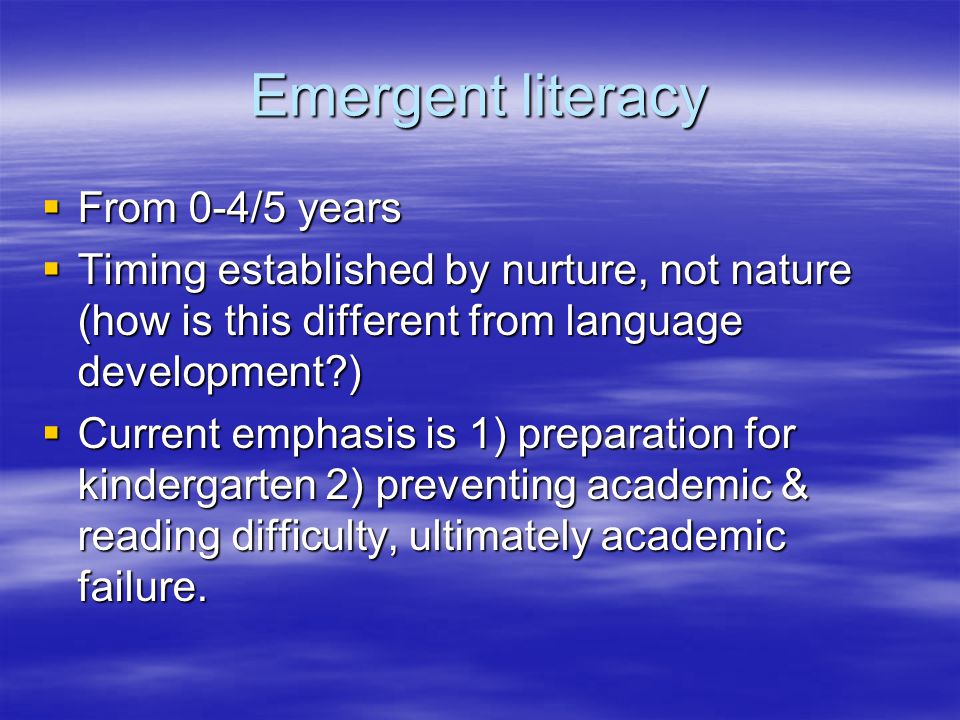

Learning to write goes beyond the process of proper spelling and grammar. Writing is a means of written communication that can be understood by others because it follows a particular set of shared rules. Children as young as 2 years begin to understand that text has meaning and can be used to express ideas, feelings, and stories. Emergent writing is children's earliest attempt at written communication.

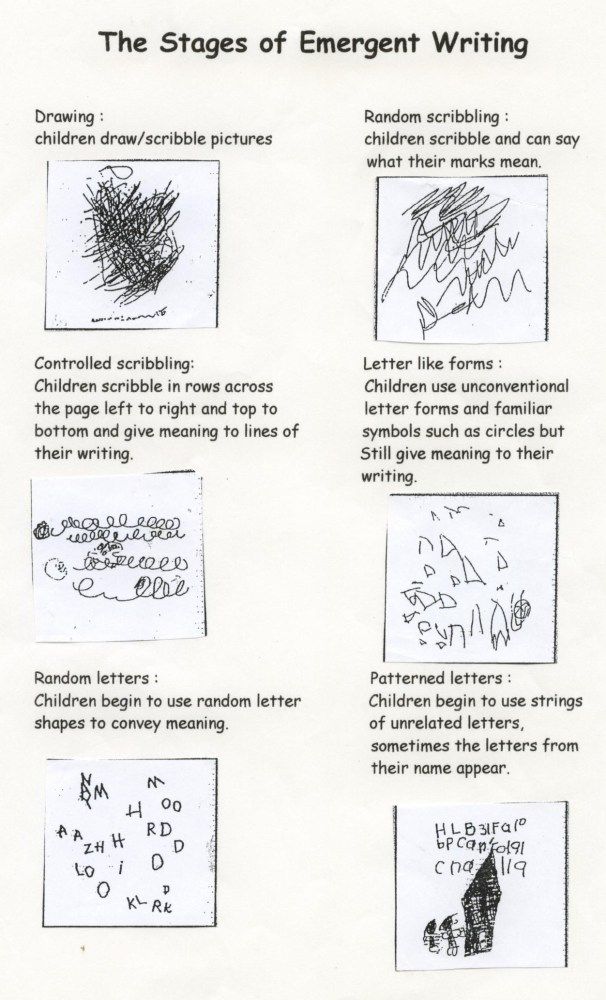

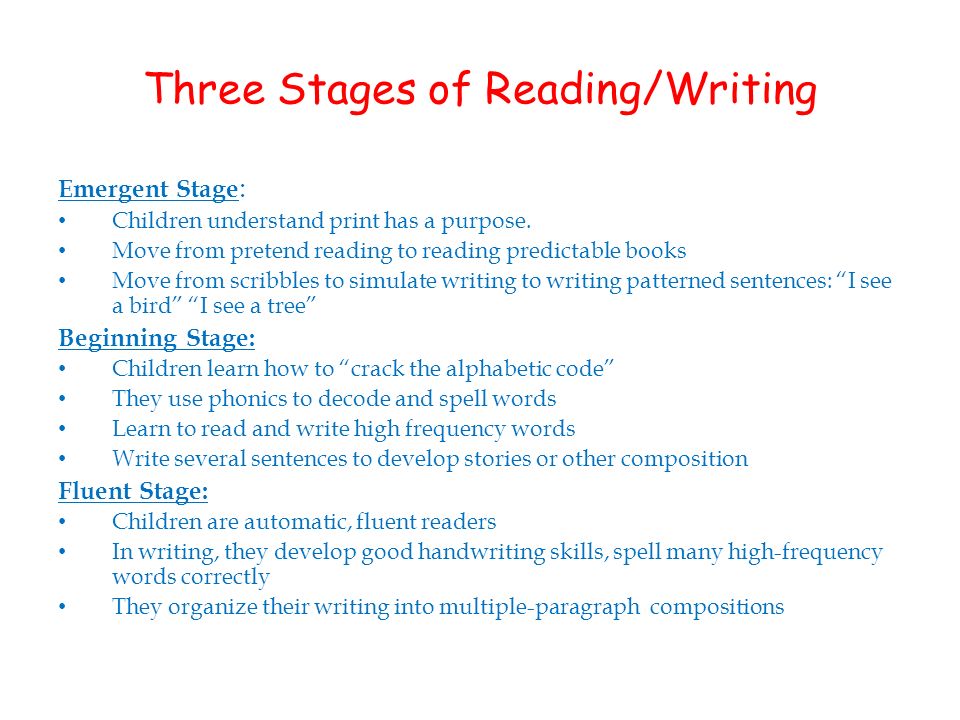

In its earliest stages, writing looks like scribbling and drawing and eventually begins to include letters of the alphabet, invented spelling, conventional spelling, and basic grammar. Most children go through predictable key stages on the path to emergent writing. However, as with nearly all areas of child development, children progress at different paces and may often display skills across multiple stages at the same time. Thus, the stages we present here are guidelines for teachers and home visitors to support individual children's efforts to communicate in writing and develop their skills.

Thus, the stages we present here are guidelines for teachers and home visitors to support individual children's efforts to communicate in writing and develop their skills.

In the earliest stages of writing development, children's writing does not include the intentional use of letters, but instead resembles scribbling or drawings. At first, children make random marks and attach no meaning to them, but later, the child intends the marks to be writing that conveys a message.

You can support the earliest stages of writing by providing children with a variety of writing materials and implements and encouraging their use. Don't be afraid to let children explore making different kinds of marks on paper, or other writing surfaces.

If your children can talk, be sure to ask them questions about their drawing and model writing skills by writing down what children say under their picture. Equally important is revisiting their drawings and what they said about their drawings the next day. This helps instill the idea that writing is read the same way each time and its meaning doesn't change.

This helps instill the idea that writing is read the same way each time and its meaning doesn't change.

In the middle stages of writing development, children begin to understand that there are rules to writing that are unique to their home language. These rules include using letters, symbols, and characters and following the directional order of writing, such as top to bottom and left to right. During this stage, children write their names but may not yet make the connection between the letters they write and their specific letter sound.

In the late stages of writing development, which may emerge in the late preschool years, children intentionally use letters to represent particular phonetic sounds. We often refer to this as "invented spelling" because it's based on what the child hears. Eventually, the child learns conventional spelling, including the irregularities in words, such as silent "Es" at the end of words like "cake." They also begin to write short phrases and begin to follow grammatical rules, such as using punctuation and starting sentences with uppercase letters.

Supporting the middle and later stages of writing usually begins by helping children write their names. This experience helps children to learn that strings of letters have meaning, a purpose, and are associated with particular sounds.

Teachers and other staff, as well as family members, can also serve as intentional writing models throughout the day, carefully pointing out the process of writing or practicing sounding out or spelling a word. Importantly, teachers and parents can provide authentic opportunities for peer scaffolded and independent writing across the day.

We can support the emergent writing of all children by first remembering that we're supporting a process, not an outcome. This process supports a child's school readiness, since writing skills develop across the primary school years and beyond. It's important to take the time to identify if a child is in the beginning, middle, or later stages of writing, in order to provide the proper support and learning experiences to help them develop in this area. Having a sense of what stage of writing a child is in will help you to anticipate potential problems with writing, as well as what you can do to help children grow and develop.

Having a sense of what stage of writing a child is in will help you to anticipate potential problems with writing, as well as what you can do to help children grow and develop.

We hope you have new ideas to expand on the ways teachers can create environments and activities to support emergent writing skills. For more information and more ideas, see the complete 15-minute Suite on emergent writing and take a look at our tips and tools and helpful resources.

Close

Stages of Emergent Writing | Thoughtful Learning K-12

Emergent writers discover many ways to send written messages. The writing samples on this page demonstrate different kinds of writing evident in a kindergarten classroom. Each sample demonstrates one or more of the qualities of effective writing.

Drawing and Imitative Writing

The child writes a message with scribbling that imitates “grown-up” writing. It shows individuality and an attempt to communicate with others.

Copying Words

The child copies words from handy resources like books, posters, and word walls. The writing makes sense and shows knowledge of letter formation and the concept of words.

Drawing and Strings of Letters

The child writes with random letters to convey a message. The letters are formed well, but have no relationship to sounds. The writer is aware that print and art convey meaning.

Early Phonetic Writing

The child writes words using letters (mostly consonants) to represent words and sounds. The writing shows individuality, focuses on a topic, and makes sense.

Phonetic Writing

The child writes words using letters to represent each sound that is heard. The words make sense and may be used for writing longer texts.

Conventional/Some Phonetic Writing

The child focuses on a topic and uses close-to-correct copy. The writing demonstrates an emerging voice.

Drawing and Imitative Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes a message or shares ideas with others through drawings and imitative writing. Scribbling and random letters are often considered to be an imitation of “grown-up” writing.

Scribbling and random letters are often considered to be an imitation of “grown-up” writing.

The first example here shows individuality. Notice the use of made-up letters to imitate writing.

The second example shows an attempt at appropriate formation of letters and words.

Copying Words

In this type of early writing, the child copies words from handy resources like books, posters, and word walls. The writer may or may not be aware of the meaning of the words.

The first sample here shows the child’s ability to use art, form letters, and copy a title from a book. The writing focuses on the topic “My Favorite Story.”

In the second sample, the writer copies a string of unrelated words for the topic “Fishy Words.” The writing shows a beginning use of words and formation of letters.

Drawing and Strings of Letters

In this type of early writing, the child writes with random letters but has a definite message to convey. The letters often have no relationship to conventional letter sounds or spelling. (Sometimes a teacher or scribe translates the message into conventional form.)

(Sometimes a teacher or scribe translates the message into conventional form.)

The writer of the first sample translates her string of letters as “playing with my baby sister.” Through art, the child focuses on the topic. A beginning ability to form letters is shown.

According to the writer of the second sample, the title is “Riding My Bike.” An early attempt at forming letters is shown. The illustration supplies some of the meaning.

Early Phonetic Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes connected letters (mostly consonants) to represent words. Sometimes the sound of the letter itself is used for a word; for example, “r” is the word are.

This writing translates as follows: “I ask my dad if he will call a playmate for me.” The writing focuses on a topic and shows an early attempt at writing a sentence.

In this sample, symbols and consonant sounds are used to show that the writer loves her dollhouse. This writing displays individuality, an early example of voice.

Phonetic Writing

In this type of early writing, the child writes words using letters to represent each sound that is heard. Consonants and vowels are used. Some punctuation may also be used.

This writing focuses on a topic and makes sense. The writer shows an awareness of consonant and vowel sounds and uses words and sentences. The art complements the writing.

The writer of this sample uses both consonants and vowels to spell words and write a sentence. The art carries details and demonstrates an emerging voice.

Conventional/Some Phonetic Writing

In this type of writing, the child increasingly writes with conventional spellings and structures. Formation of letters is also more conventional.

This writer focuses on a topic and shows individuality. The writing uses words and sentences appropriately.

The writer’s message makes sense and shows an understanding of the friendly letter. The writing exhibits the appropriate use of words and sentences.

Understanding the concept of emergence

Most of us find it difficult to grasp the concept of emergence because it is only entering our consciousness. When something new comes up, we don't have a simple shorthand for it. The words we're trying to use seem jargon. So we stumble upon words, images and analogies to convey that smell in the air that we can barely smell. We know it exists because something doesn't fit easily into what we already know.

Emergence disturbs, creates dissonance. We understand the meaning of the confusion that arises, in part, due to the development of language that helps us identify useful differences. As the vocabulary to describe what appears becomes more familiar, our understanding increases. For example, anxiety, disruption, and dissonance are part of the language of attracting emergence. These terms are cousins and are often used interchangeably. Violation is the most important of the three words. If something has to do with an emotional nuance, it's likely that the disturbance is called anxiety. When a conflict is complex or a breakup is particularly irritating, in the absence of agreement or harmony, its dissonance should probably be referred to.

If something has to do with an emotional nuance, it's likely that the disturbance is called anxiety. When a conflict is complex or a breakup is particularly irritating, in the absence of agreement or harmony, its dissonance should probably be referred to.

Definition of emergence

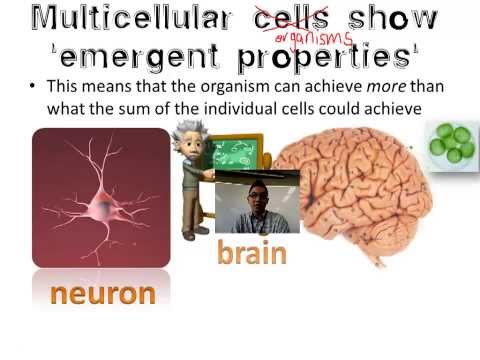

Let's define what emergence is: order emerging from chaos. A more detailed definition is the higher order complexity that emerges from the chaos in which new coherent structures come together through interactions between the various entities of the system. Emergence occurs when these interactions break down, causing the system to differentiate and eventually merge into something new.

The key elements of this definition are chaos and novelty. Chaos is random interactions between different entities in a given context. Imagine people at a cocktail party. Chaos does not contain clear patterns or rules of interaction. Make it a cocktail party that isn't dominated by any single culture so no one knows how close to stand with others, whether to look them in the eye, whether to use their first or last name. Emergent order occurs when a new, more complex system is formed. Often this is an unexpected, almost magical obstacle. The cocktail is really a surprise party and everyone knows where to hide and when to sing "Happy Birthday".

Emergent order occurs when a new, more complex system is formed. Often this is an unexpected, almost magical obstacle. The cocktail is really a surprise party and everyone knows where to hide and when to sing "Happy Birthday".

Emergence creates new systems - consistent interactions between entities that follow basic principles. In his best-selling book Emergence, science writer Steven Johnson puts it this way: “ Agents who are on the same scale begin to do things that are one scale above them: ants create colonies; citizens create neighborhoods; simple pattern recognition software learns to represent new books.” The emergence of human systems has led to the emergence of new technologies, cities, democracy, and, as some would say, consciousness - the ability to self-reflection.

Differences between weak and strong emergence

Scientists distinguish between two forms of emergence: weak and strong. Understanding this distinction removes some confusion. Predictable patterns of emergent phenomena such as traffic and anthills are examples of weak emergence. On the contrary, a strong emergence is perceived as a shock. When disruptions abruptly change the shape of a system, as in revolutions and renaissances, there is a strong emergence.

Predictable patterns of emergent phenomena such as traffic and anthills are examples of weak emergence. On the contrary, a strong emergence is perceived as a shock. When disruptions abruptly change the shape of a system, as in revolutions and renaissances, there is a strong emergence.

Weak emergence describes new properties that emerge in a system. The child is completely different from its parents, but mostly predictable in form. In the case of weak emergence, the rules or principles act as an authority, providing a context for the functioning of the system. In essence, they eliminate the need for someone in charge. Road systems are a simple example.

A strong manifestation occurs when a completely unpredictable new form appears. We could not guess its properties, understanding what happened before. Nor can we trace its roots to its components or their interactions. We are watching a story on television. However, we could not predict this form of storytelling from the books.

When strong emergence occurs, the rules or assumptions that form the system are no longer reliable. The system becomes chaotic. In our social systems, perhaps the situation is too complex for the traditional hierarchy to solve. For example, self-organizing emergency response. Such circumstances give him a reputation for being frightening obstacles to faith.

However, emergent systems increase order even in the absence of command and central control: useful things happen without any direction. Open systems extract information and organize their environment. They bring consistency to increasingly complex shapes. In the processes of emerging change, clear intentions, creating an enabling environment, and inviting different people to connect do the job. Think of it like a long cocktail party with a purpose.

Learning how to use emergence

The history of emergence is still young. We struggled with its existence, described some of its properties and gave it a name. We understand early on what this means for social systems—organizations, communities, and sectors such as politics, health, and education. We are just learning how to work with it to support positive change and deep transformation.

We understand early on what this means for social systems—organizations, communities, and sectors such as politics, health, and education. We are just learning how to work with it to support positive change and deep transformation.

In social systems, emergence can push us toward opportunities that serve enduring needs, intentions, and values. Forms can change, preserving core truths while introducing innovations that were not possible before. In journalism, the traditional values of accuracy and transparency are permeating the blogosphere, social networking sites, and other emerging media.

Emergence is a process, continuous and endless. It emphasizes interaction as much as the interacting people or elements. Most of us focus on what we can observe—an animal, a project result, an object. Emergence also means paying attention to what is happening - an arriving stranger with different cultural perspectives that permeate an organization or community.

Emergence is a product of the interaction of various entities. Because interactions don't exist in a vacuum, context also matters. This is why simply bringing together different people will not necessarily lead to a promising result. The initial conditions set the context. The way the invitation is crafted, the quality of the reception, the questions asked, the physical space all influence whether a fight breaks out or a warm, unexpected partnership develops.

Because interactions don't exist in a vacuum, context also matters. This is why simply bringing together different people will not necessarily lead to a promising result. The initial conditions set the context. The way the invitation is crafted, the quality of the reception, the questions asked, the physical space all influence whether a fight breaks out or a warm, unexpected partnership develops.

Source https://peggyholman.com

Read also: What helps female leaders get more than 2000% revenue growth

Who is a narrative designer and how to become one - Gamedev on DTF

Differences from a screenwriter and necessary skills.

11,800 views

Game Designer course instructors in Netology — Maria Kochakova, CEO of Narratorika online school, and Anton Tokarev, Apella Games Lead Technical Game Designer, in a column for DTF talk about what a narrative designer is in the gaming industry, how he differs from a screenwriter and how to become one.

What is narrative and why players need it

The main feature of game art is its interactivity. Unlike cinema, in a game you are not just a spectator, but an active participant in events who can influence its outcome with your decisions and actions. The moment the gameplay stops being mere lines of code, and the script and characters come to life and begin to "engage" the player in the story, a narrative emerges.

Even in those games where it seems that the narrative is not needed at all, it is there. For example, in the arcade game Pong, where players vertically move their paddles across the field to defend the goal, the narrative emerges through a location, a tennis court. Or in hyper-casual games, where there is only one mechanic per game, there is also a minimal narrative, which is expressed through the visual component, the game interface.

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

In fact, there are two views on what a narrative is and whether all games have it. For example, from an academic point of view, narrative is an integral part of how the human brain works, because we constantly invent and tell stories in our head: about ourselves, the world, people around. In this sense, narrative is present in all games, even abstract ones.

For example, from an academic point of view, narrative is an integral part of how the human brain works, because we constantly invent and tell stories in our head: about ourselves, the world, people around. In this sense, narrative is present in all games, even abstract ones.

Recall Tetris, from an academic point of view, it has a narrative, because in the process of passing we can tell ourselves a story: “I don’t come across a long stick for a long time”, “I put the piece wrong”, “everything went wrong”, “the speed of movement of elements increases, I don’t have time for anything” and so on. The second point of view is practical. What game developers call narrative is the purposeful effort to create a story in a game, that is, the presence of content and how it is presented to the player. It turns out that in a primitive sense, there is no narrative in Tetris.

But not everything is so simple, besides this, in narrative design there is a division into “built-in” and “emergent” stories. Built-in is when the creators came up with the plot and integrated it into the work. And emergent is when the player himself creates a story with his actions.

Built-in is when the creators came up with the plot and integrated it into the work. And emergent is when the player himself creates a story with his actions.

Some researchers, in particular Cathy Salen and Eric Zimmerman, in the book “Rules of Play” (not translated into Russian) say that emergence is an inherent property of games in principle, because they always have the freedom of choice of the player, that is, interactive And if you remove this component, then the game will turn into a book or a movie. If we return to the Tetris example, it turns out that it does not have a built-in narrative, but there is an emergent one.

Today it is almost impossible to find a game that has only emergent or only embedded narrative. The exception is abstract games. But in most works, one way or another, both types will occur in different proportions. For example, in Skyrim and The Witcher 3, the proportions are approximately equal, while in Dragon Age there is more built-in narrative.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

Generally speaking, narrative design is the art of telling a story through gameplay. In good games, the narrative is, in fact, the gameplay.

In The Game Narrative Toolbox, a textbook for narrative designers, the authors describe narrative design as the art of telling stories in games using all available means, techniques, methods and tools. I use another definition: narrative design is the organization of the player's experience into a story that is optimal for solving the problems of the developers.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

The role of the narrative designer in game development

It may seem that a narrative designer is an artificial position, because scriptwriters and game designers are already working on the game story. In fact, this person acts as an important link between different development departments and makes sure that the user does not have a feeling of ludonarrative dissonance (a contradiction between the mechanics of the game and its plot).

Often, writers who come into game development from other arts don't understand how games tell stories. They come up with a plot, and then insert it however you want. Game designers, in turn, can be talented mathematicians and at the same time understand nothing at all in dramaturgy. All this leads to the fact that the story in the game is separate, the gameplay is separate. Hence the need arose for a third person who would speak two languages and serve as a translator between game designers and scriptwriters.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

In some ways, the work of the narrative designer is reminiscent of the haiku addition mini-game from Ghost of Tsushima: in it, the main character leaves the battlefield for a while and, under the guidance of the player, "collects" poems from his experiences and references to the events of the game.

Likewise, a narrative designer chooses disparate game art tools and media (mechanics, dialogue, animations, etc. ) and connects them to the gameplay, trying to create the most addictive and complex game experience. Its task is to make sure that the player can gradually form a story through their actions and believe in the world that the developers have created for them.

) and connects them to the gameplay, trying to create the most addictive and complex game experience. Its task is to make sure that the player can gradually form a story through their actions and believe in the world that the developers have created for them.

In game design, there are two different concepts that are closely related to the gaming experience - involvement (engagement) and immersion (immersion).

involvement is always about gameplay and interesting in-game activities. As a rule, other game designers work on it.

And for the narrative designer, the “sacred cow” is immersion . The narrative designer, during the process of creating the game, makes sure that nothing breaks the immersion in the story and does not break the player's trust in the world and the events taking place inside it.

Work on any project in the gaming industry is divided into three stages: pre-production, production and post-production. True, the specific responsibilities of a narrator are highly dependent on the team or studio, so there is no universal scheme or system. In addition, the games are very different from each other: they have different genres, gameplay, settings and target audience.

In addition, the games are very different from each other: they have different genres, gameplay, settings and target audience.

Pre-production always starts with a vision of the game and a concept document. At this stage, we are trying to understand what we want to do in general, and then we decide how to proceed. When the team has a vision for the story and gameplay, the tennis ball flies to the narrative designer. He comes up with how to combine these things and with what mechanics the story will be told. For example, we have a character - a space marine, we want to convey his experience to the player. To do this, the narrator explains to the screenwriter what is required of him and what tools he has in his arsenal. But talking about stages and a clear pipeline can only be very conditional: there are often games in which the script is written when everything else is almost ready.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

During production, a narrative designer works on various texts with scriptwriters, communicates closely with other team members, thinks through the mechanics and actions of characters, collects references and prepares technical specifications for artists, participates in choosing music and selecting voices for dubbing, and also controls the creation of a general atmosphere games.

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

At the post-production stage, the work of the narrative designer continues in two directions. Firstly, he can fix bugs in the story - that is, based on feedback from the players, correct things that are out of the plot and cause a negative experience. Secondly, for many games, work does not end on release, DLCs are released, updates continue. Therefore, narrative designers simply move on to creating new content.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

It is important to understand that games as a whole are a syncretic art form, on which different specialists work together. It is always a process of communication and exchange of experience between the game director, game designers, artists, scriptwriters, narrative designers and other team members. For example, one can easily imagine a situation where a narrative designer comes up with a mechanic together with a game designer, and an artist comes to the scriptwriter for advice. And vice versa.

And vice versa.

In large studios, many specialists work on the game's plot. For example, the lore designer is working on the structure of the universe (the word “lore” itself just means background information about the game world that is not related to the plot), the script writer writes the plot, the dialogue writer describes all the conversational scenes in the game.

And the narrative designer collects all these narrative elements of the game and combines them with mechanics and gameplay, protecting the interests of the story and the logic of the script, making sure that the story does not conflict with the gameplay. If the project team is small, the narrative designer himself describes all the parts and coordinates them with the specialists who will implement the project.

For example, a narrative designer comes to a level designer and says: “According to the lore, we should have a castle at this level, but according to the plot, a dragon attacks the castle.

At this time, the characters are having a dialogue in the main character's room. The room should tell us the story of this character, who he is, with all the regalia on the walls and details in the form of portraits of people dear to him on the desk. At the same time, in the dialogue, the player has several possible answers, and what he chooses depends on whether the dragon destroys the castle or not.”

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

Many people confuse the roles of a narrative designer and a game writer due to the fact that in the vacancies of studios there are constant requests for one specialist who will perform two functions at once. However, this does not mean that narrative designers must be able to write a script or dialogue. It is likely that the developers do not have enough funding and they are trying to save on an additional position.

Game scripting - about content, lore, plot, characters and their motivation, all in-game texts.

And narrative design is about how this content is presented in the game, with what tools we will do it: through gameplay, environment or through cut scenes, maybe through comic inserts ... The narrative designer decides, for example, whether the dialogue system will be interactive or not, whether the user will be able to replay the scene, how will he understand that the cut-scene has begun or ended.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

What a narrative designer should know and be able to do

Anyone who wants to be part of the gaming industry should be able to program. A game is a software product, and it is important for a production participant to understand the terminology in order to communicate with colleagues. In addition, in small development teams, narrative designers sometimes have to take part in writing scripts for dialogues or quests.

It is equally important to have the basic knowledge and skills of a game designer: understand the mechanics, understand how the balance is built in games, know what the game loop, meta, learning curve, and so on. By the way, knowledge of a foreign language can be an advantage. If you are at least a little familiar with the cultural background and characteristics of another people, this can be very useful in the production process.

By the way, knowledge of a foreign language can be an advantage. If you are at least a little familiar with the cultural background and characteristics of another people, this can be very useful in the production process.

Also important for a "narrator" is the skill of working with texts and narration. To do this, you need to understand the laws of dramaturgy, understand the basics of screenwriting and be able to work in different genres in form, volume and content in order to find the best way to visualize events, scenes and dialogues in the game.

Strange as it may seem, the favorite text editor of game scripters is Excel, in Word, as a rule, they write only non-interactive parts of texts, for example, cut scenes. Another important tool is flowcharts of various types, such as Draw.io or Miro. In addition, it is important to be able to use any prototyping tools and everything that helps to plan work. In general, everything that is in the arsenal of a game designer is also used by the narrator.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

The set of soft skills is standard: communication skills, stress resistance, time management skills, all this is important for a narrative designer as well as for other modern specialists.

How to Become a Narrative Designer

One of the easiest options is to take highly specialized courses, of which there are more and more of them lately. So you can understand the profession and earn yourself a small portfolio, it will become an advantage in further employment.

You can also grow into a narrative designer from a game designer. This does not mean that one of these specialists is higher in the hierarchy, just a game designer is a broader specialization, and narrative design is a narrower and more specific direction of development.

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

If you know for sure that you want to connect your life with games, but are not yet sure whether it is worth developing into a narrative designer, you can take the Netology Game Designer course. In the context of learning, there is a whole block devoted to narrative, which, in any case, will be useful, even if you realize that this direction is not for you. Conversely, if you decide to retrain as a narrative designer, with the accumulated knowledge base, it will be easier for you to develop the necessary skills.

In the context of learning, there is a whole block devoted to narrative, which, in any case, will be useful, even if you realize that this direction is not for you. Conversely, if you decide to retrain as a narrative designer, with the accumulated knowledge base, it will be easier for you to develop the necessary skills.

A more difficult, but also a good option is to assemble a team and create your own project, where you will be responsible for the story and its implementation in the gameplay. If your environment does not have the same enthusiasts, then you can participate in one of the game jams and join the spontaneous development team as a narrative designer. You can add this project to your portfolio later. For example, such game jams are held by the Indicator community.

To develop a portfolio, you can also create your own visual novel with interactive plot forks and different endings, for example, on the RenPy engine. This is an excellent training in writing the plot and dialogues, in the selection of references for the visual accompaniment of the game. Such an experience will be useful for both a narrative designer and a future video game writer.

Such an experience will be useful for both a narrative designer and a future video game writer.

Tips

Play games that are completely different

Playing games that are known to be good is very important to develop discernment. Check out AAA games like The Last of Us, Metal Gear Solid or Death Stranding. They have a narrative in the user interface, in the environment, in the dialogues. Also worth mentioning are Outer Wilds, Dishonored and Sekiro.

A very good story is served in Guardians of the Galaxy. Another example of a quality narrative is Apex Legends. It, like Overwatch, can be played without bothering with the study of the fate of the characters and other details. But, if it's interesting, you can immerse yourself in the history of the world, learn about the islands on which you are fighting, understand why all these competitions are needed, get to know each of the characters better and find out their true motives and roles.

Everything in this game has a narrative rationale.

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

There are games that are considered classics of narrative design, such as Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, Journey, Portal, Papers, Please, and basically everything that Lucas Pope does. Many will now be surprised, but narrative designers love Dark Souls. The game is very well done - it has a great storyline, all the elements are beautifully inscribed in the setting, and the presentation of the lore is one of the best in games of this type, when the background is restored by breadcrumbs. We can say that this is generally a separate gameplay, a separate mental task in the descriptions of the subject - to bring all the dots together, draw lines between them and understand what is happening in general. And my favorite game Subnautica is a pearl of narrative design, because every action of the player, all survival: searching for resources, recipes, crafting is all our story of passing.

What Remains of Edith Finch is another gem, where each room is a separate mechanic. And each mechanic is used to tell the story of one of the family members. Of the latest domestic games, I really like Loop Hero, the entire gameplay is explained by the setting, a seamless gaming experience. And one of my favorite indie games is The Longing. In general, I really like indie games, because it is there that some interesting narrative mechanics are created and “run in”.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

The narrative designer definitely needs to play what he is going to create. For example, if you're going into match-3 mobile development, play Homescapes, Gardenscapes, and Lily's Garden. Nevertheless, try to review and get the most versatile gaming experience. The portrait painters in the gallery, of course, pay great attention to portraits, but they also eagerly absorb the works of marine painters, landscape painters, and still life masters. After all, you never know where “that idea” will come from.

After all, you never know where “that idea” will come from.

If you are serious about narrative design, then you need to play everything and on all platforms to the maximum in order to collect mechanics, watch how the story is presented, what tools, how dialogues look and play, what they look like. While playing, it is very important to listen to yourself: try to understand where the immersion broke, and think about how you could fix it if you had infinite resources, and vice versa if there is no budget at all.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

Play games (board games) again

An interesting way to "pump up" your storytelling skills and writing imagination is to play with friends or like-minded people from the thematic community in the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop role-playing game.

This game takes place 99% in your imagination: participants describe all their actions, emotions and plans in words and in dialogues with party members, writing down only key steps and making notes during the battle. By participating in a D&D party as a player, you will be able to practice character design, backstory and motivation, as well as get acquainted with a variety of game mechanics invented by the authors.

By participating in a D&D party as a player, you will be able to practice character design, backstory and motivation, as well as get acquainted with a variety of game mechanics invented by the authors.

And if you decide to become a dungeon master and lead the players through the scenario, you will learn how to describe the plot in detail, create exciting events, role-play for numerous NPCs, develop level design and control the monsters that players meet in battle in their adventures. By the way, many celebrities have been playing D&D for years. Among them, for example, are Game of Thrones screenwriters David Benioff and D. B. Weiss, game designer and screenwriter Chris Avellone, and many others.

Read, watch, listen to developers

You can deconstruct various games or watch others do it. For example, Anna Musina from Mooshi Games periodically writes articles and notes on the review of the narrative. Including, collects diagrams of relationships of characters during the game.

Analyzing such deconstructs is very useful if you are a game designer or plan to become one.

Anton Tokarev, Lead Technical Game Designer, Apella Games

Watch Youtube channels about game design. For example, Mark Brown is a classic not only of game design analysis, but also of narrative design. It is also useful to listen to lectures from GDC developers or interviews with developers. Here you have passed It Takes Two - listen to Yousef Fares' interview about how it was created, you will get a lot of useful information from there.

Maria Kochakova, teacher of the Game Designer course at Netology

Read professional literature

Game writing and narrative design textbooks are very basic these days. They help complete beginners, so it's best to read game design textbooks, even though many books get outdated quickly. Here is a short list.

- Jesse Schell, Game Design.

Learn more