Examples of non fictional stories

Nonfiction Novel Overview & Examples | What is a Nonfiction Novel?

English Courses / SAT Subject Test Literature: Tutoring Solution Course / Literary Genres: Tutoring Solution Chapter

Miranda Schouten, Bryanna Licciardi- Author Miranda Schouten

Miranda has a BA in English from the University of Iowa and is currently pursuing her MA in secondary education. Throughout her coursework she has written and implemented several lesson plans in the classroom setting.

View bio - Instructor Bryanna Licciardi

Bryanna has received both her BA in English and MFA in Creative Writing. She has been a writing tutor for over six years.

View bio

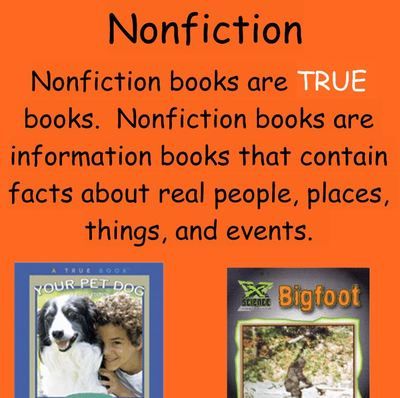

Explore the nonfiction genre in literature. Understand the meaning and features of fiction and nonfiction through examples of fiction and nonfiction novels. Updated: 02/15/2022

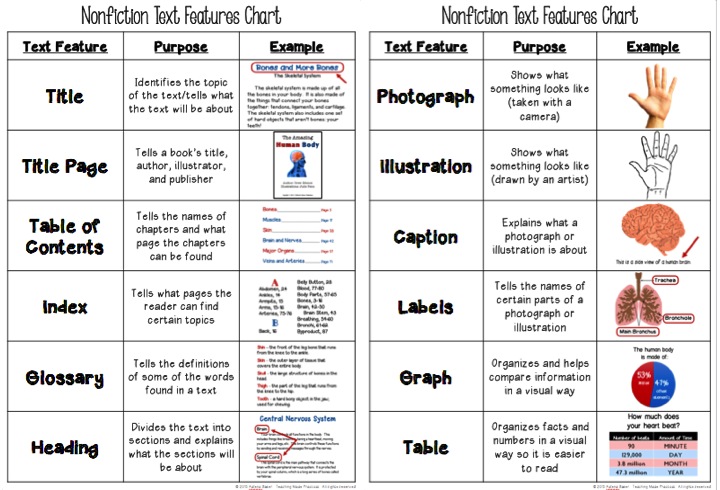

Table of Contents

- What Is Considered a Novel?

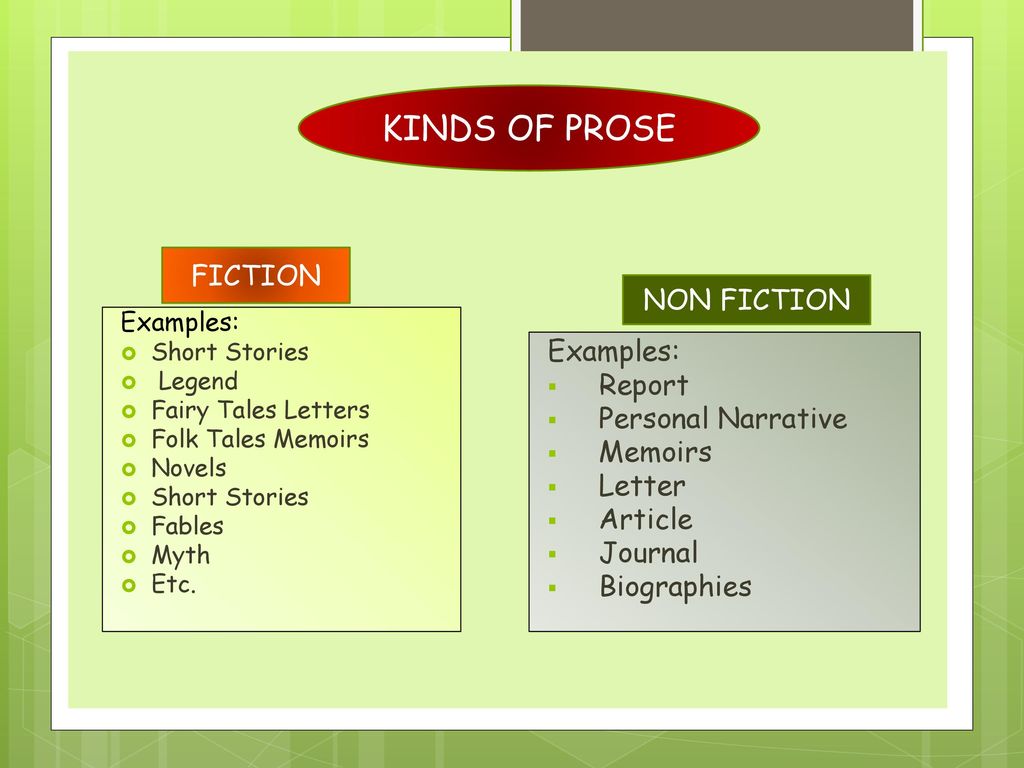

- Fiction and Nonfiction Meaning

- Nonfiction Genre

- Examples of Nonfiction Books

- Lesson Summary

What Is Considered a Novel?

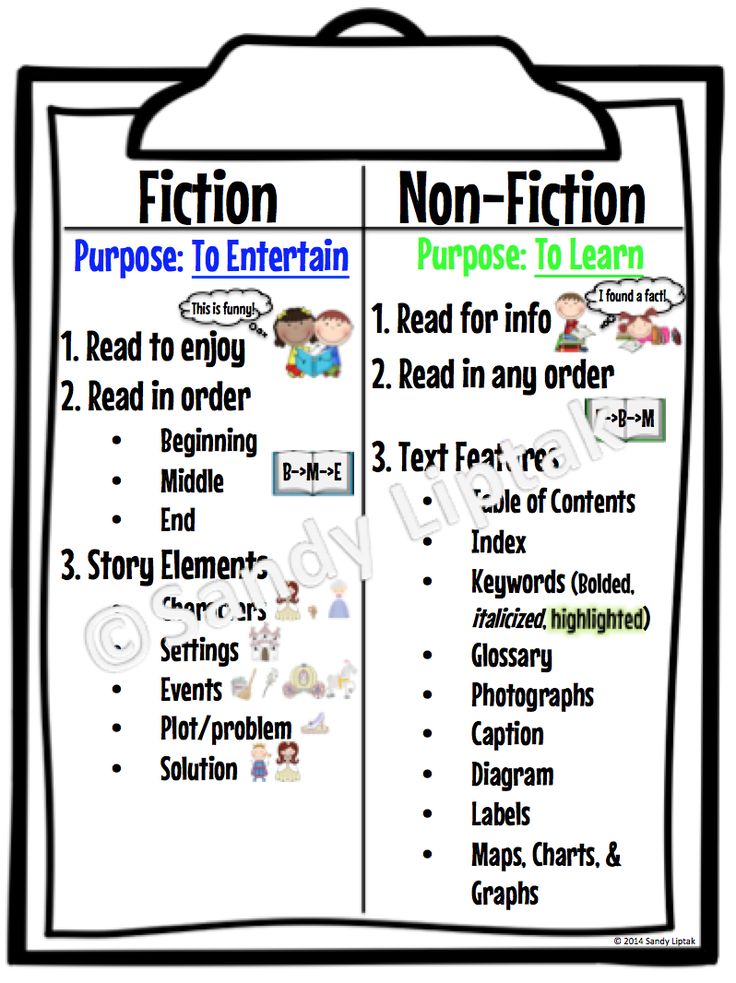

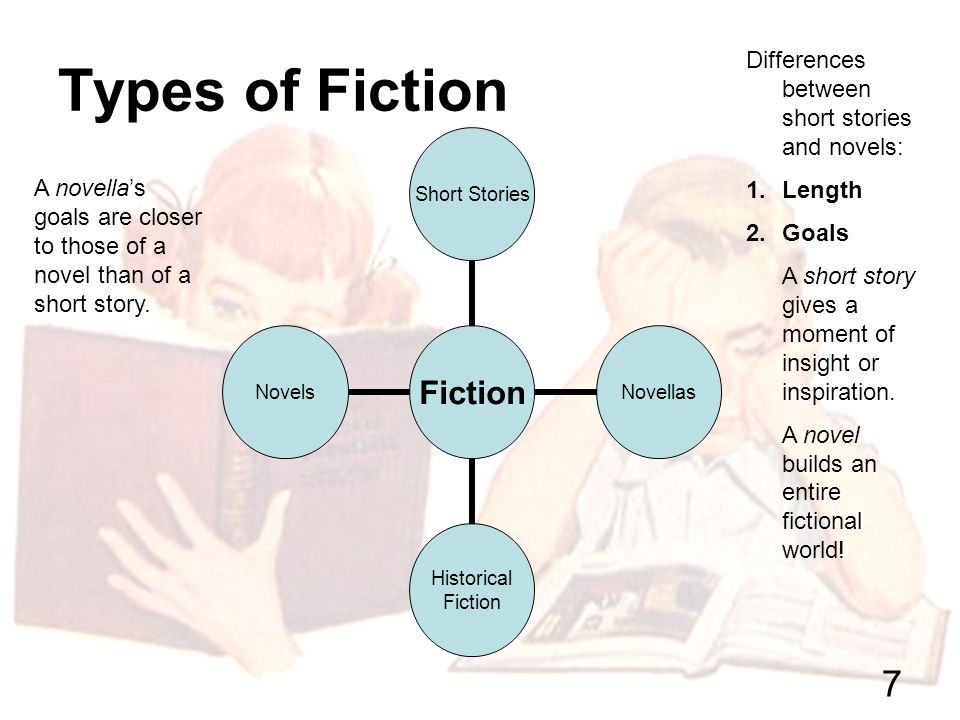

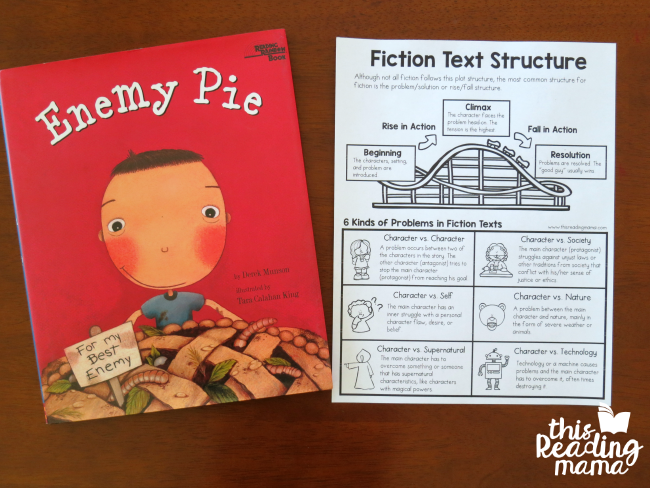

A novel is a written work that is intended to entertain readers. Written in story form, novels contain characters and a continuous plot. Novels engage the reader in a way that requires continual reading for full immersion in the story. Although it is less common, a novel can be nonfiction. Nonfiction novels are stories that incorporate actual people and events into the dramatic, immersive experience of a novel.

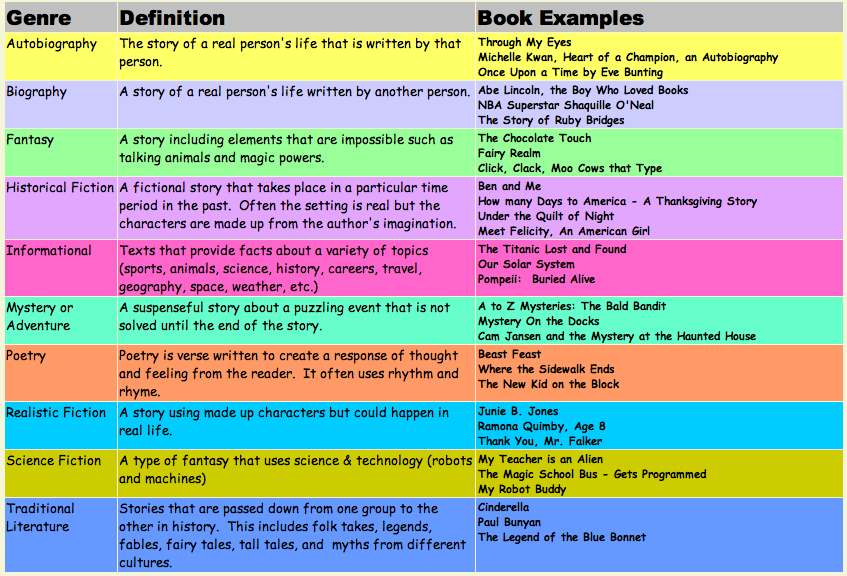

Definition

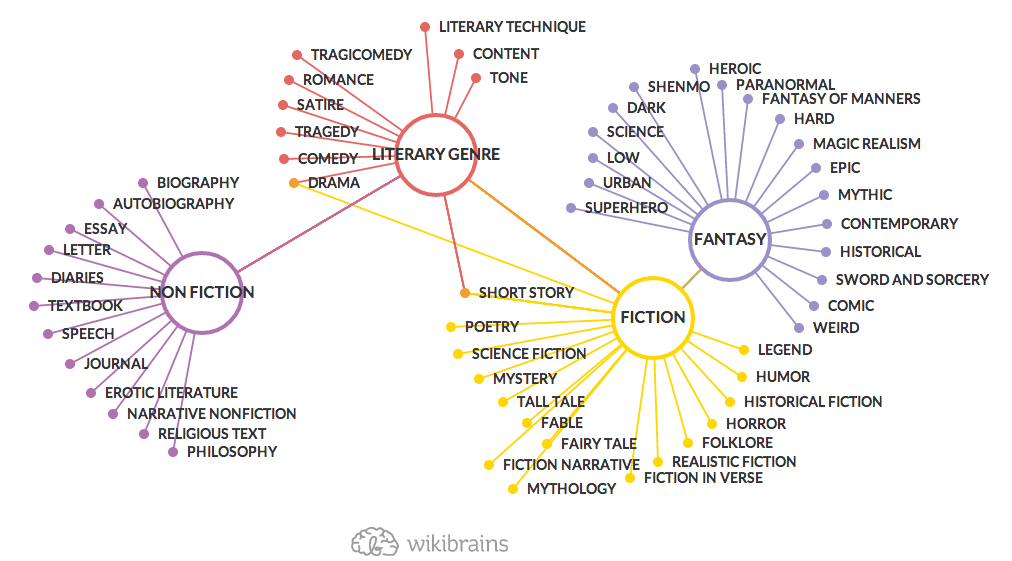

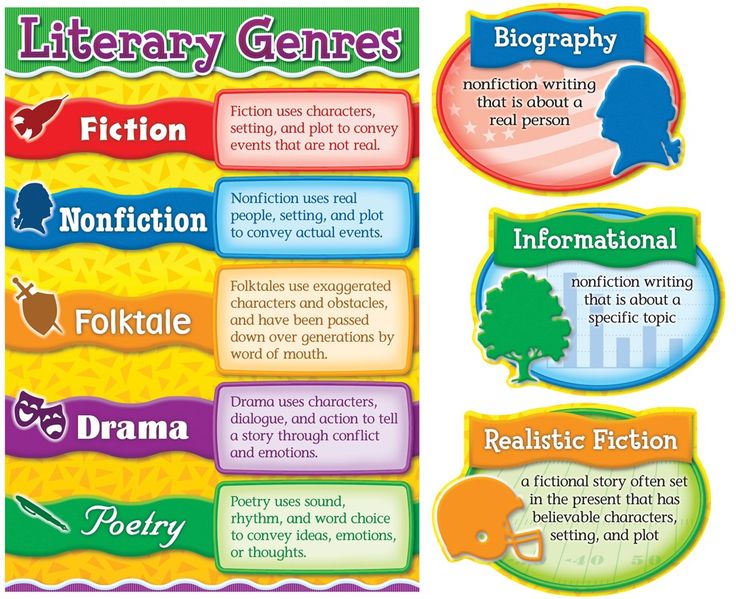

Nonfiction is a genre in literature in which real events are depicted using story-telling techniques. Though the people and situations written about are true, the writer has creative license with how to tell the story. This makes the genre's definition rather flexible. Many nonfiction novels are written in such categories as biographies, historical events, travel, science, religion, philosophy, and art.

Though the people and situations written about are true, the writer has creative license with how to tell the story. This makes the genre's definition rather flexible. Many nonfiction novels are written in such categories as biographies, historical events, travel, science, religion, philosophy, and art.

While some critics argue nonfiction has been around for centuries, Truman Capote claimed to have been the creator of this genre with his 1966 crime novel In Cold Blood. Whether or not Capote created the genre, he did give it a name. He claims the genre was inspired by his idea to integrate narrative journalistic reportage and creative writing techniques. However, unlike journalism, his idea of nonfiction would rely on creative writing to tell factual events, and rather than imbedding himself into the story, he would imply his credibility through his use of empathy and truth of the events.

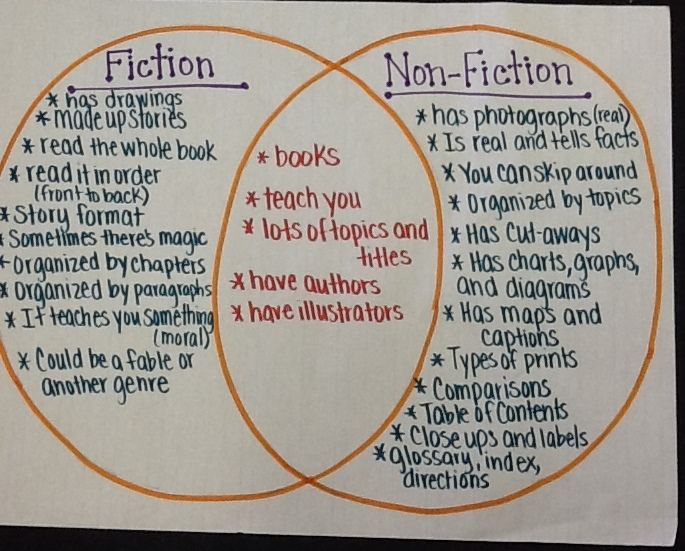

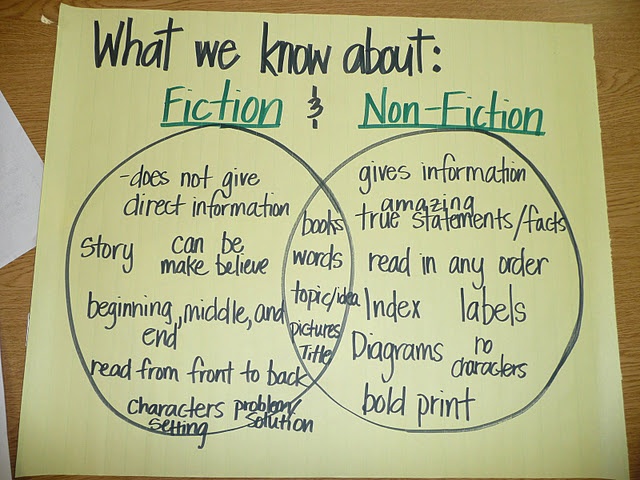

Fiction and Nonfiction Meaning

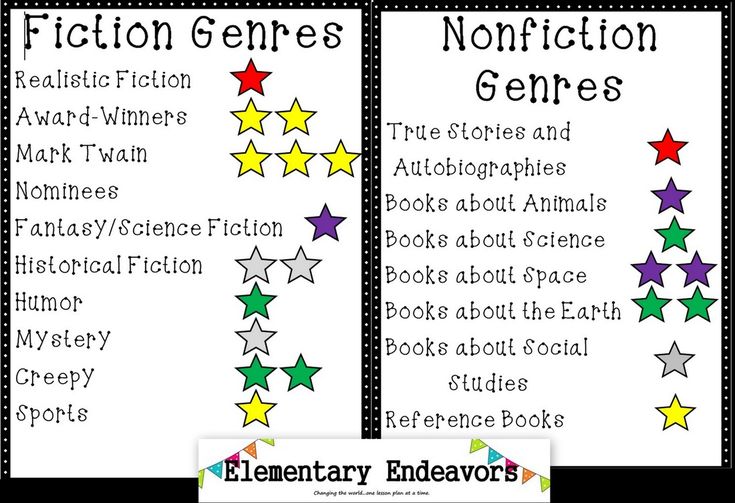

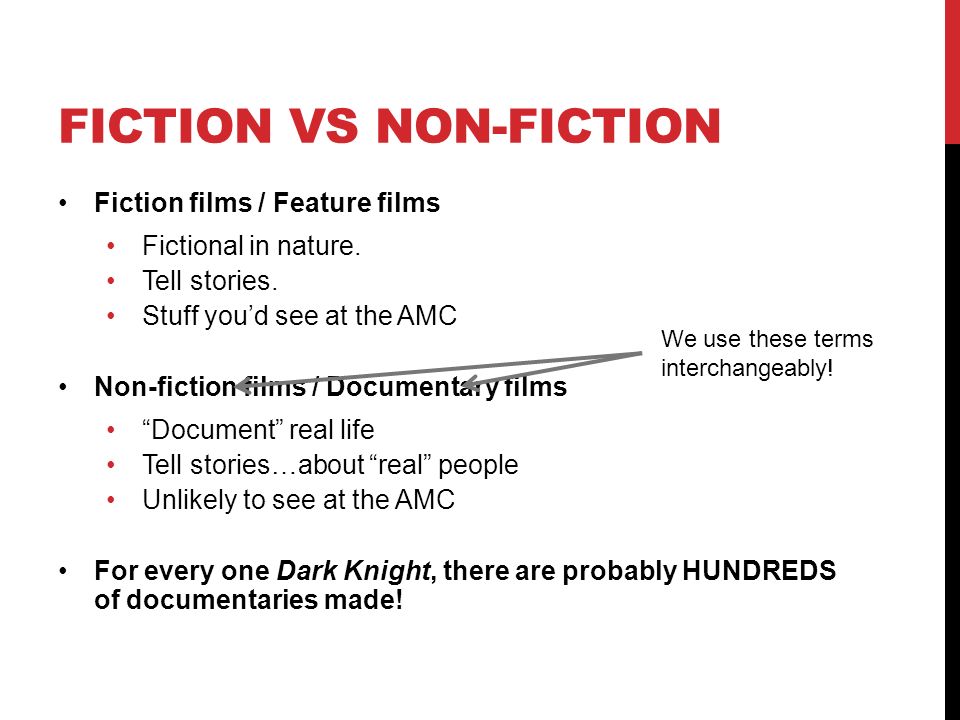

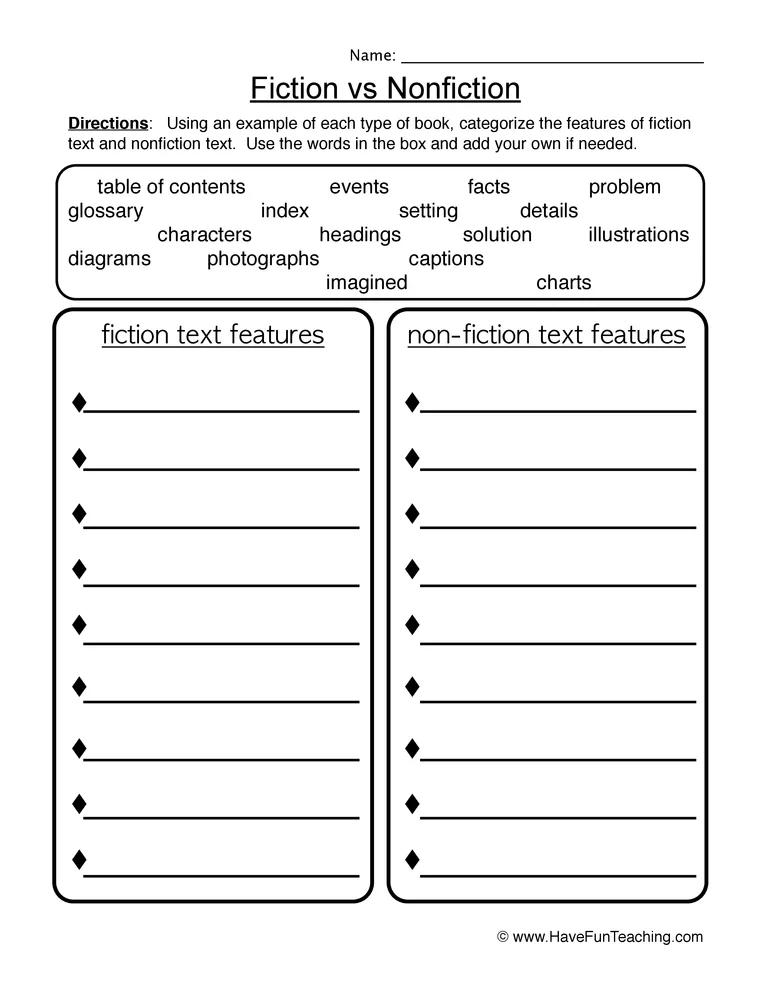

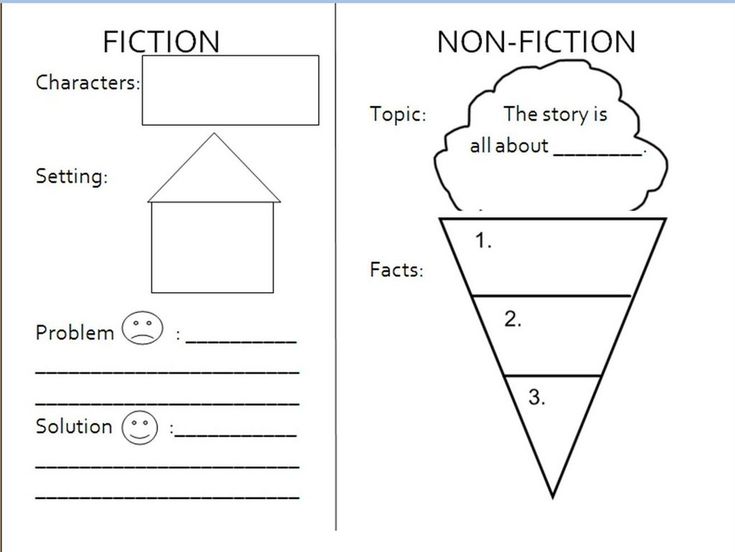

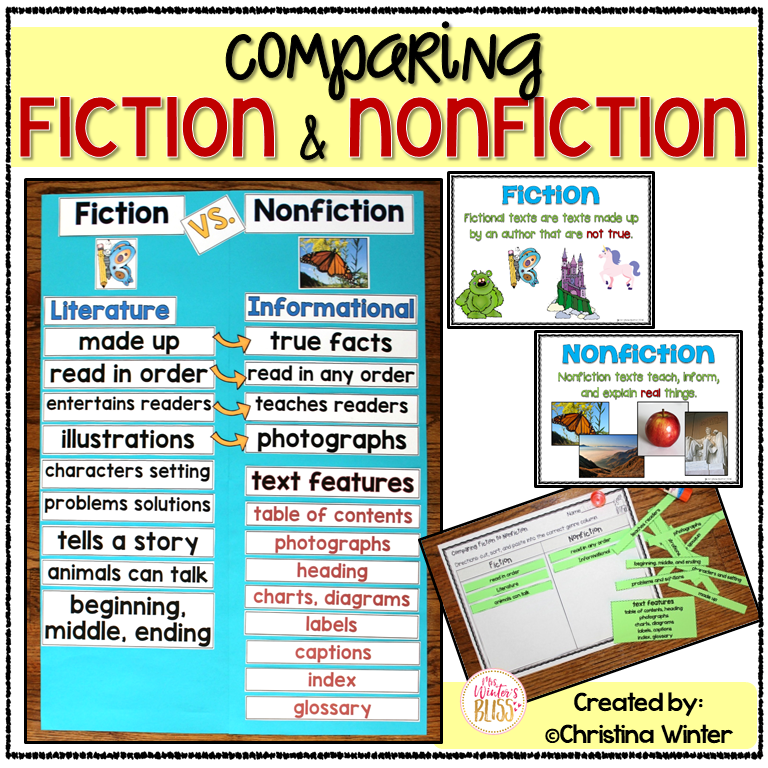

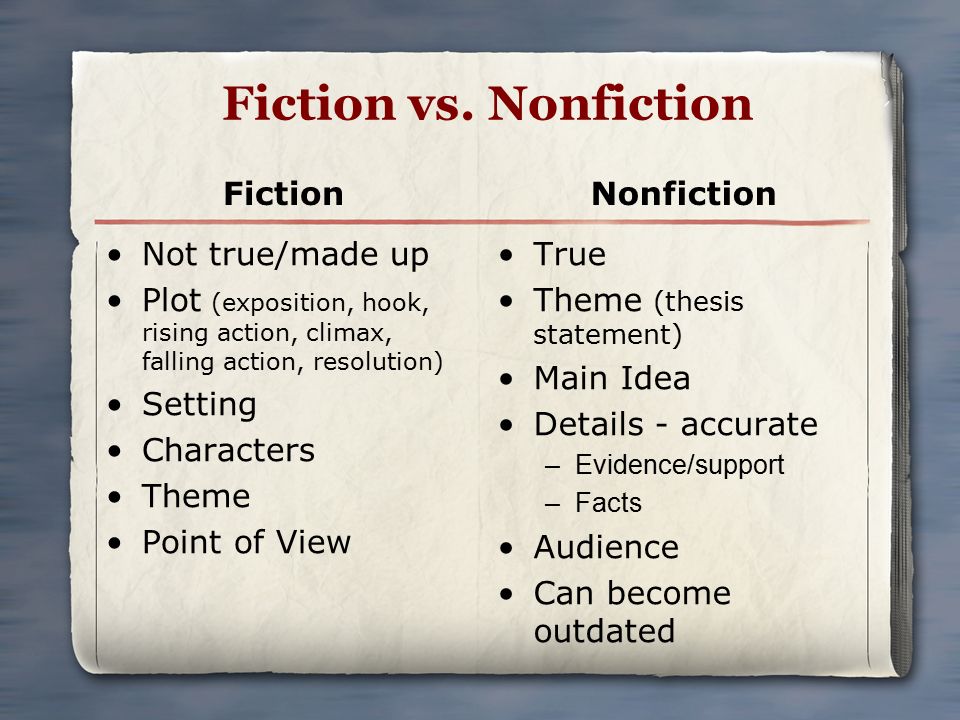

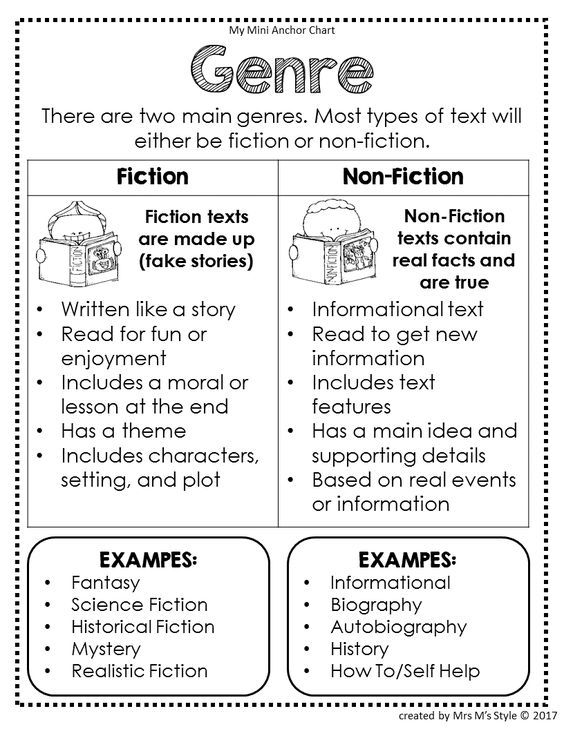

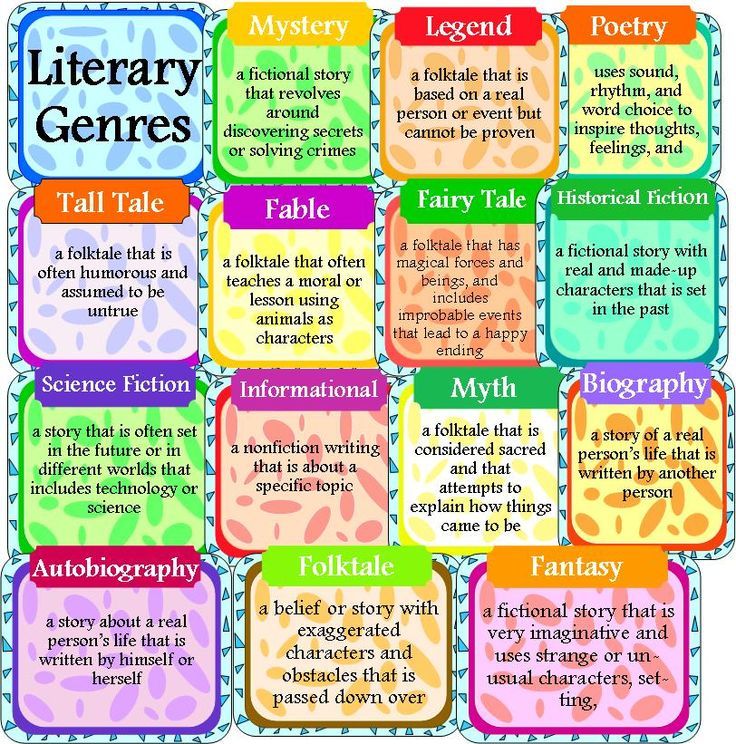

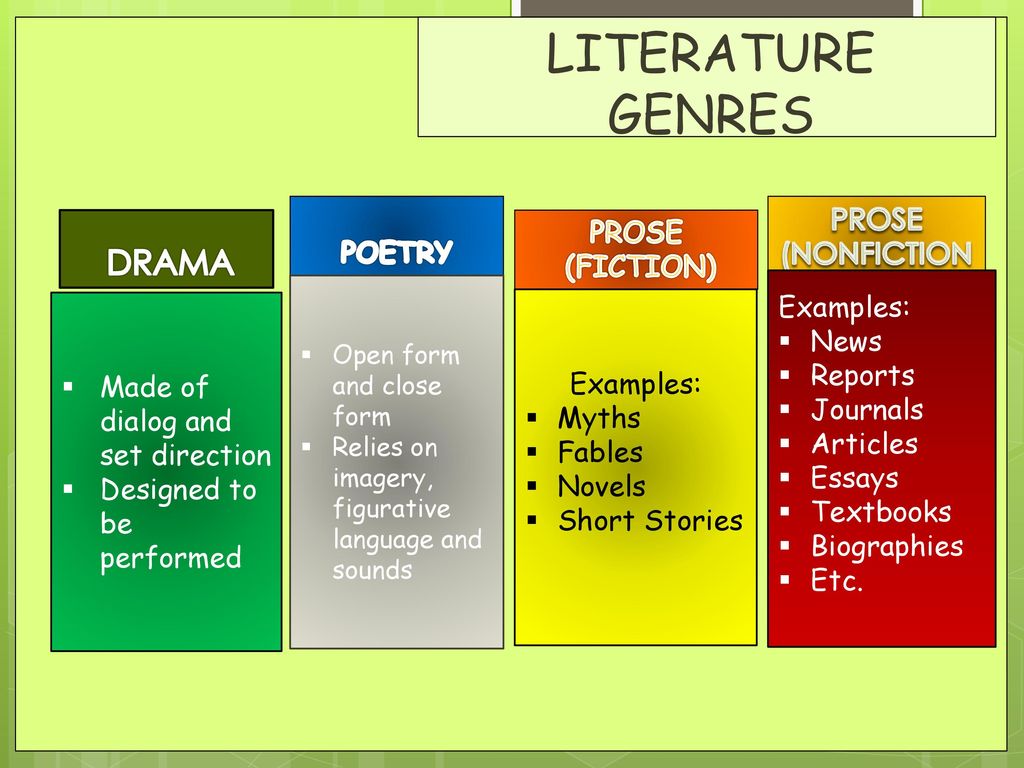

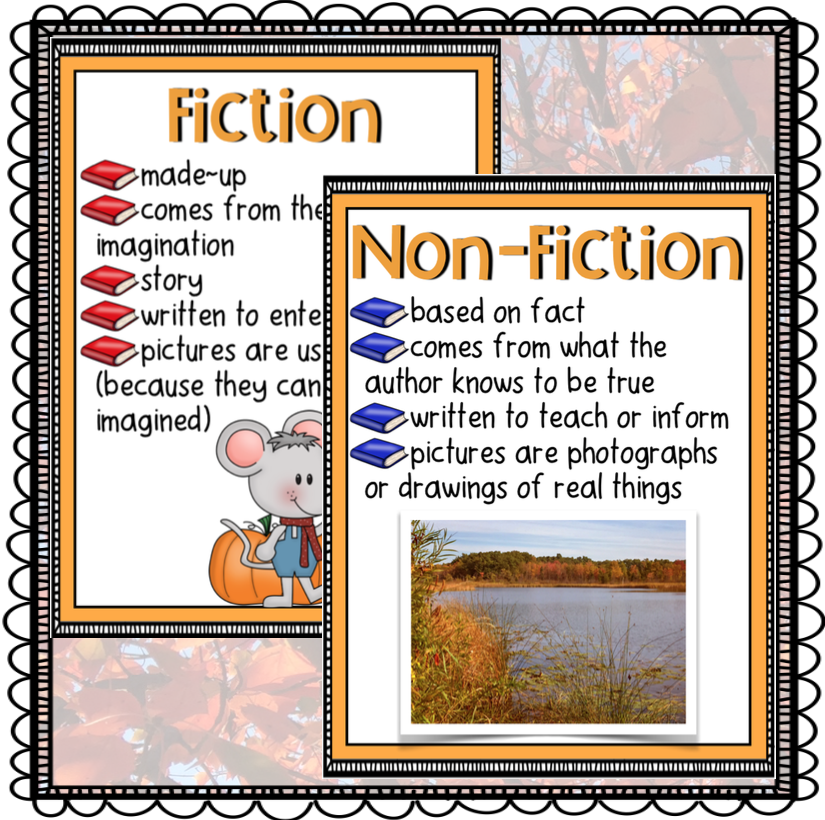

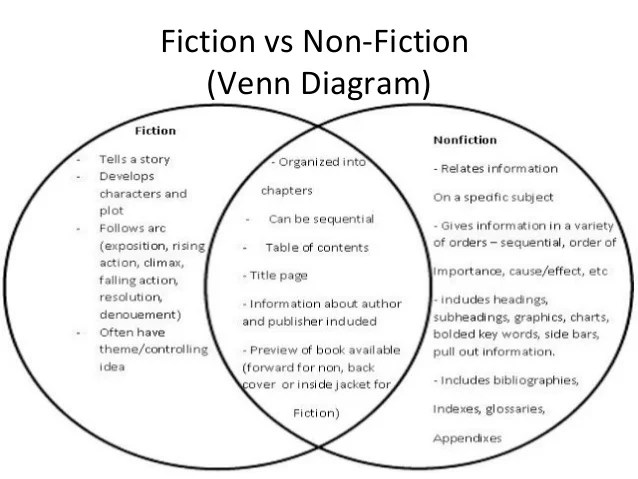

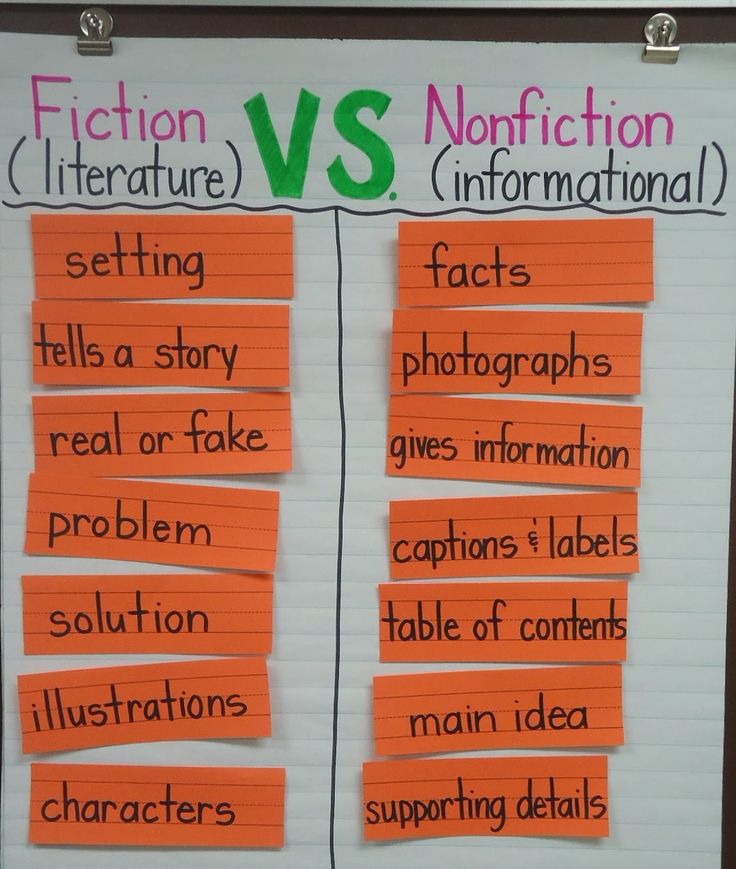

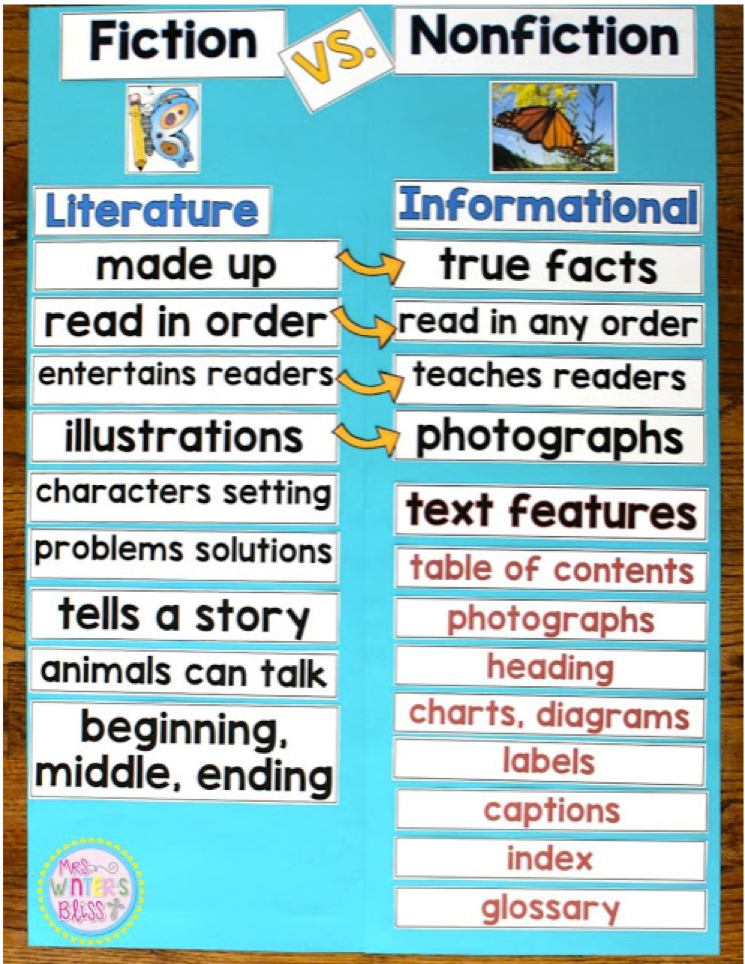

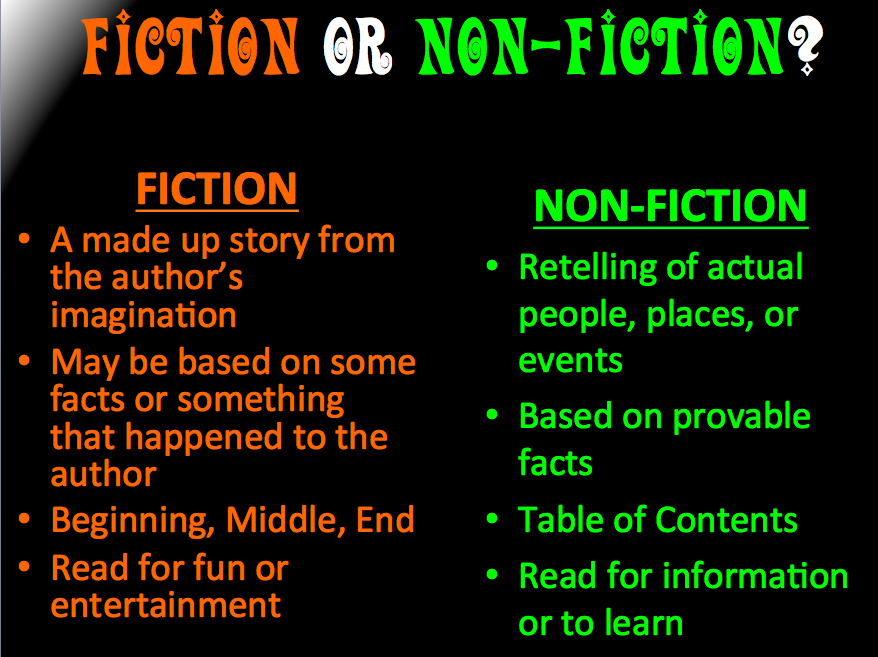

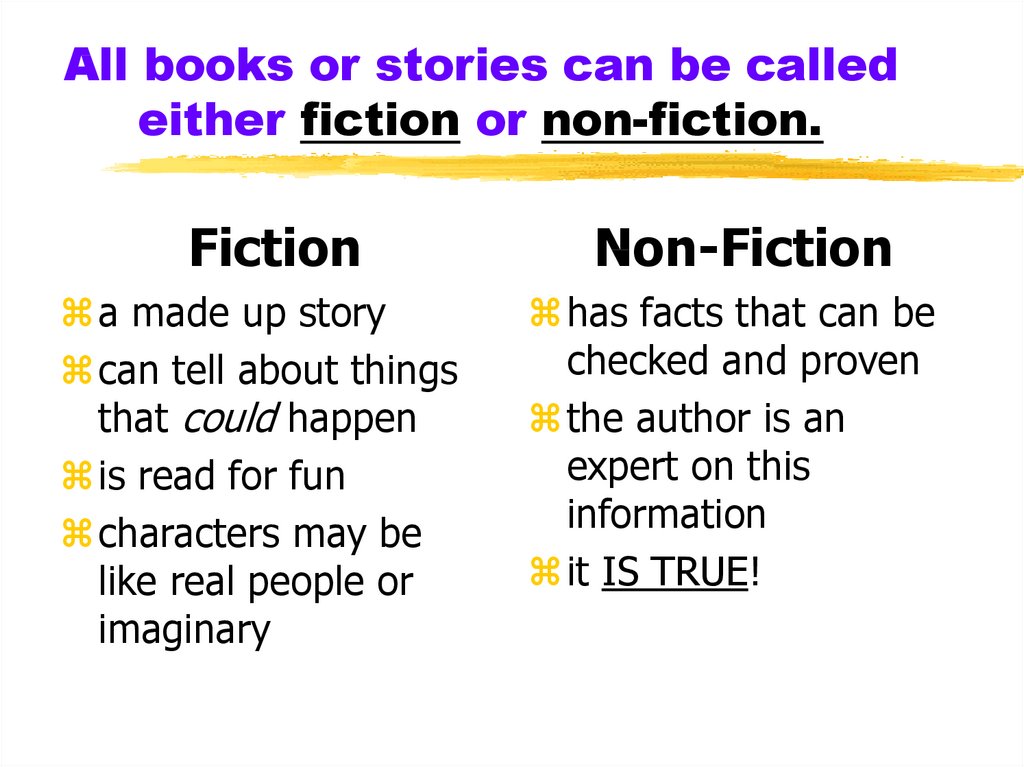

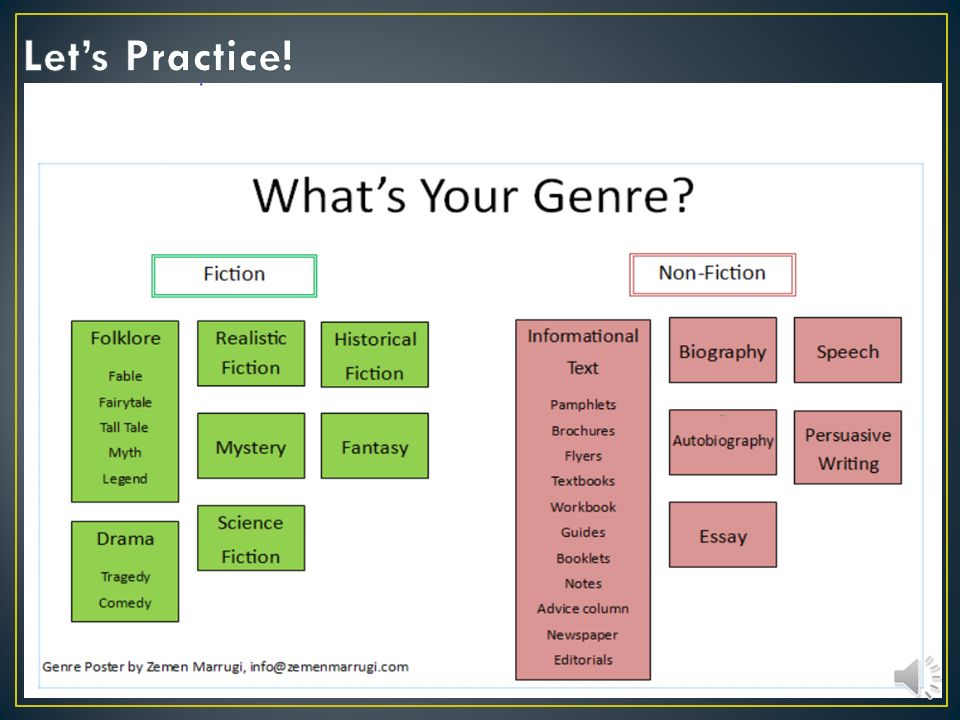

Fiction and nonfiction, meaning imaginative and factual, respectively, are the two main genres that encompass all literary works. Fictional literature is imaginative writing that is subjective, taking the writer's feelings and opinions into consideration, or those they hope to pass on to the reader, in order to create a captivating story. Because fictional literature is created by the writer, it is not essential for the writer to spend a great deal of time doing research, although it can be helpful in certain genres.

Fictional literature is imaginative writing that is subjective, taking the writer's feelings and opinions into consideration, or those they hope to pass on to the reader, in order to create a captivating story. Because fictional literature is created by the writer, it is not essential for the writer to spend a great deal of time doing research, although it can be helpful in certain genres.

Unlike fiction, nonfiction writing is based on fact and typically intended to be objective, meaning it should not be influenced by the author's personal feelings or opinions. Years of research and data collection go into writing a nonfiction novel because of the importance of factual accuracy. If a nonfiction piece includes information about a person that is later proven to be false, the writer can be sued for libel, which is defined as publishing a false statement that is damaging to a person's image or reputation.

Fiction and Nonfiction Examples

It can be difficult at times to tell whether a written piece is fiction or nonfiction. Below are several fiction and nonfiction examples that will help clarify the definition of each.

Below are several fiction and nonfiction examples that will help clarify the definition of each.

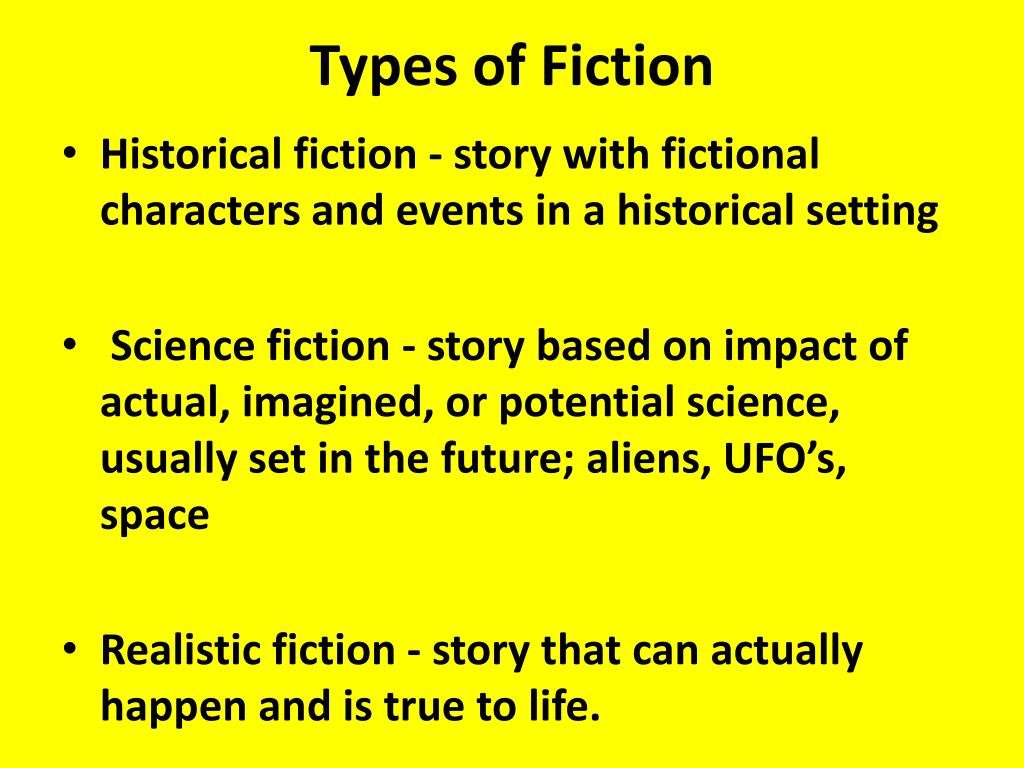

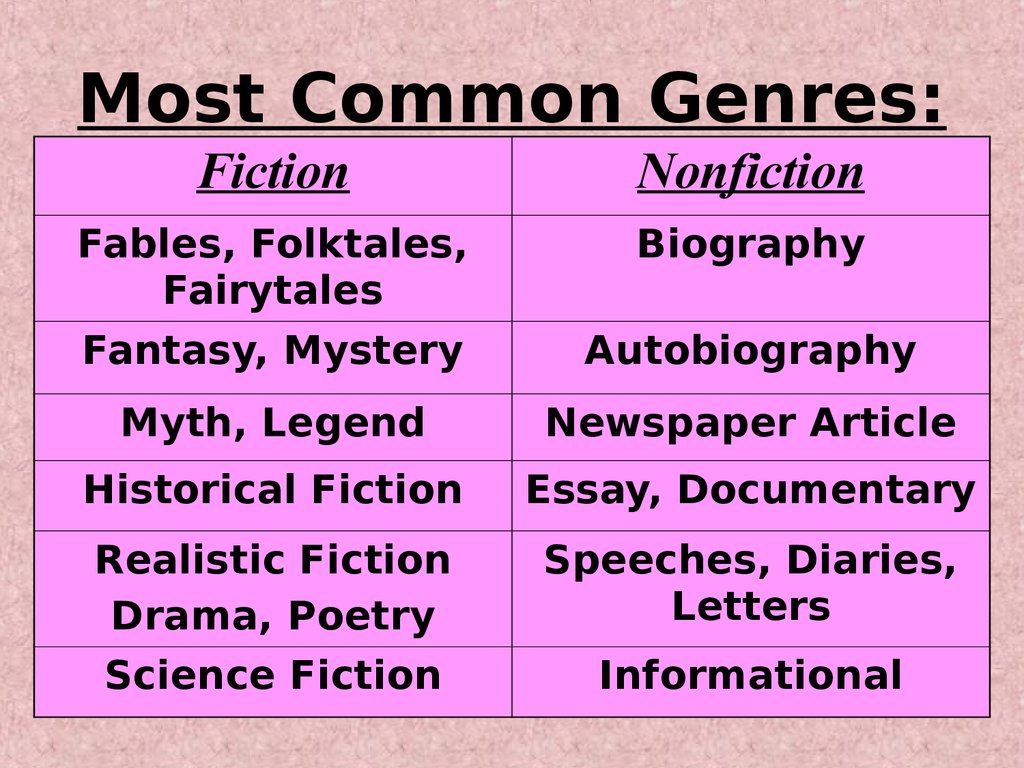

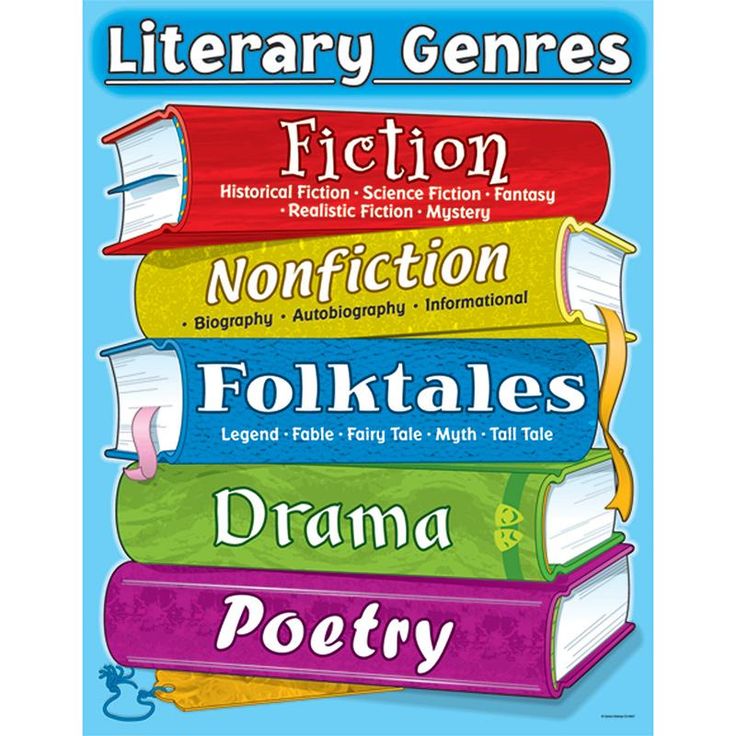

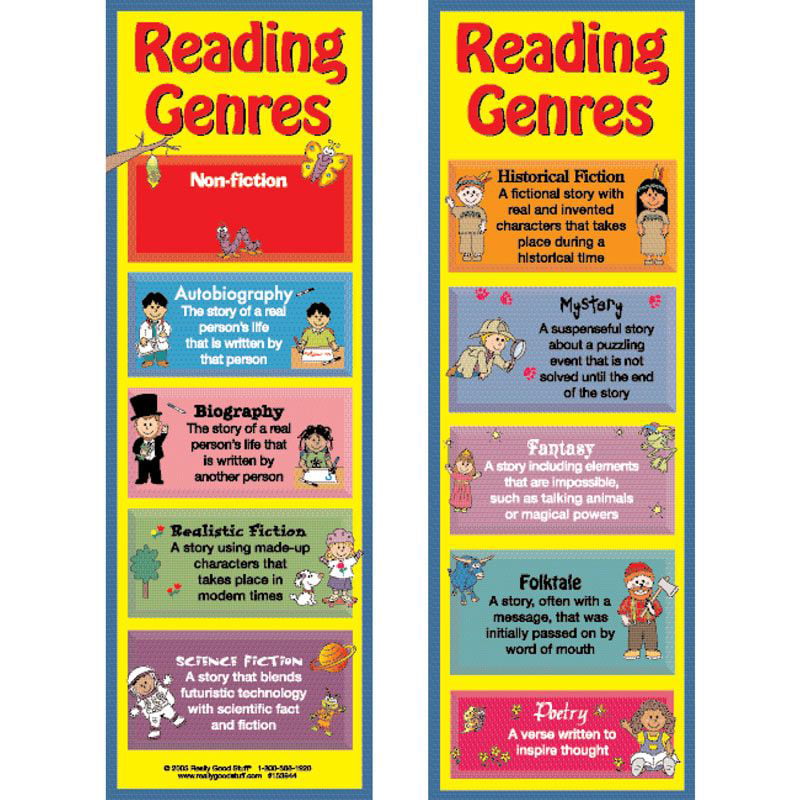

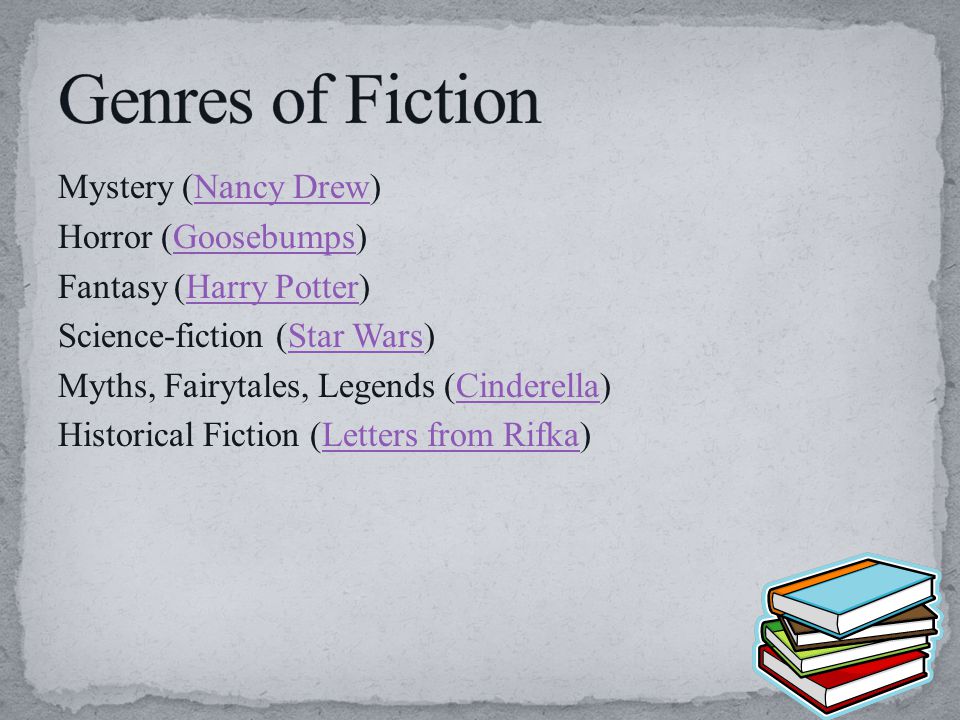

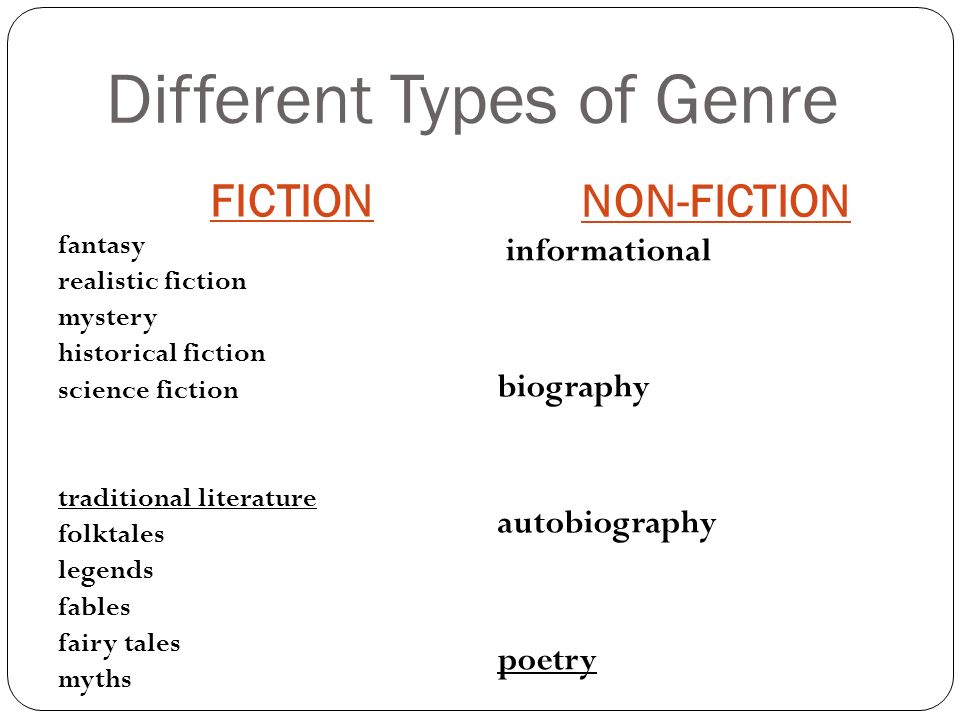

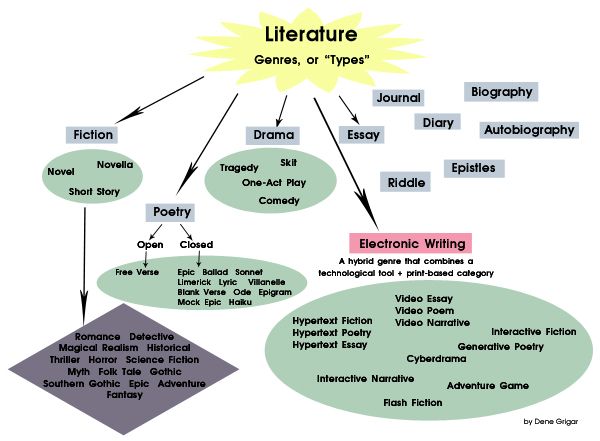

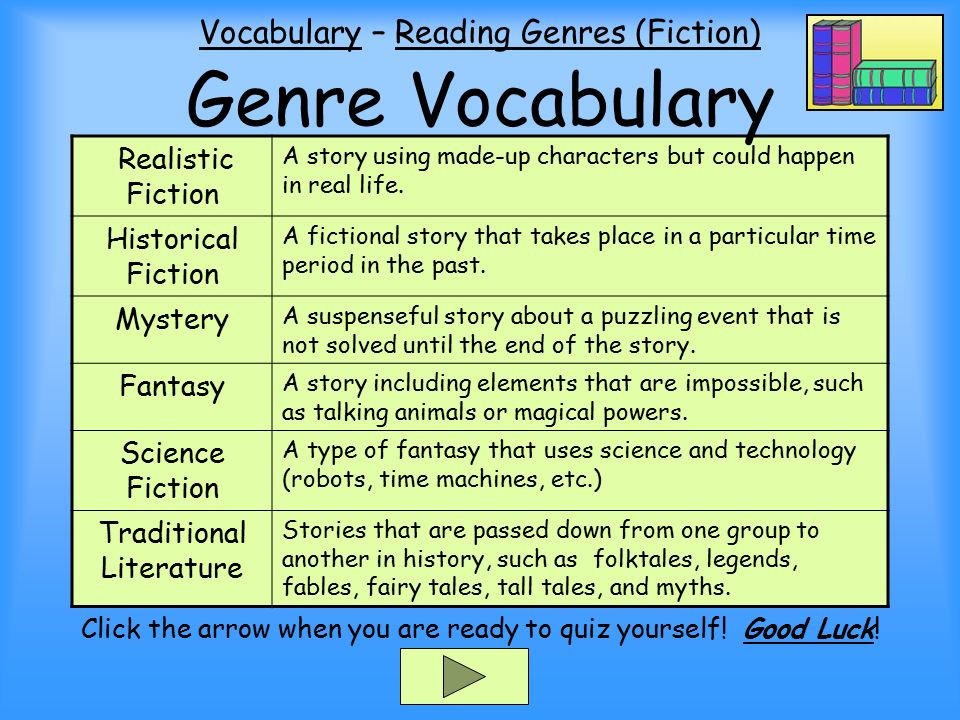

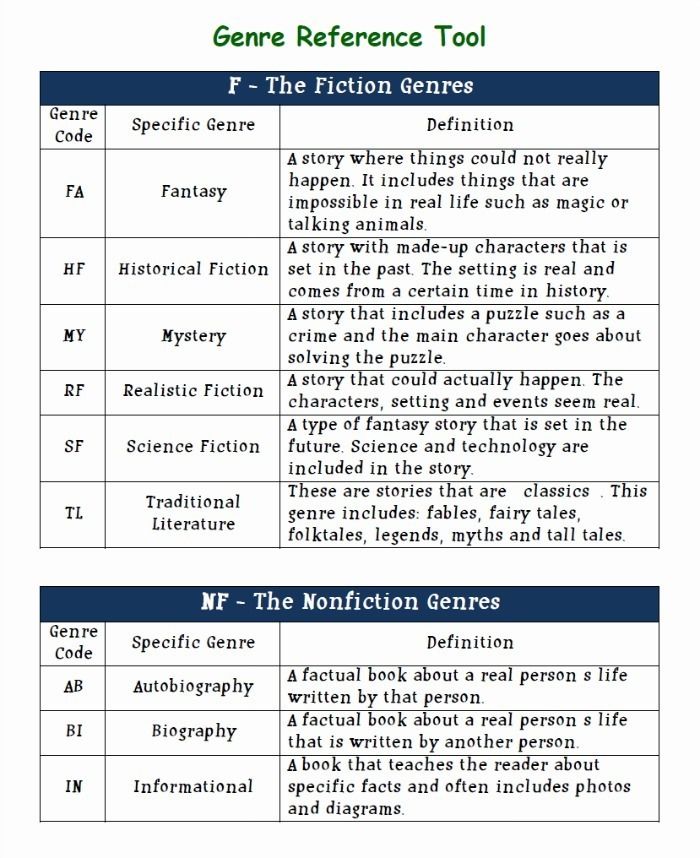

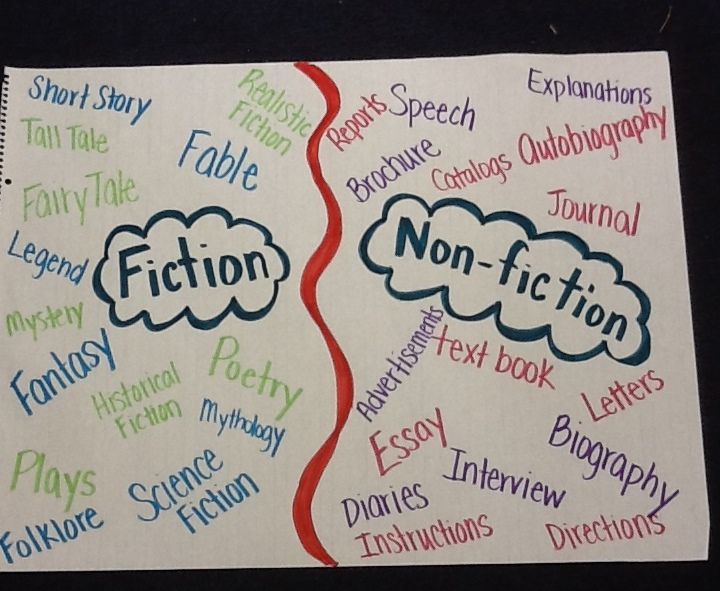

The fiction category includes a variety of genres, including crime, fantasy, romance, science fiction, and horror. Some examples of popular fiction novels are:

- The Lord of the Rings trilogy, J. R. R. Tolkien - Fantasy

- Frankenstein, Mary Shelley - Science fiction

- The Shining, Stephen King - Horror

- Pretty Girls, Karin Slaughter - Crime

- The Notebook, Nicholas Sparks- Romance

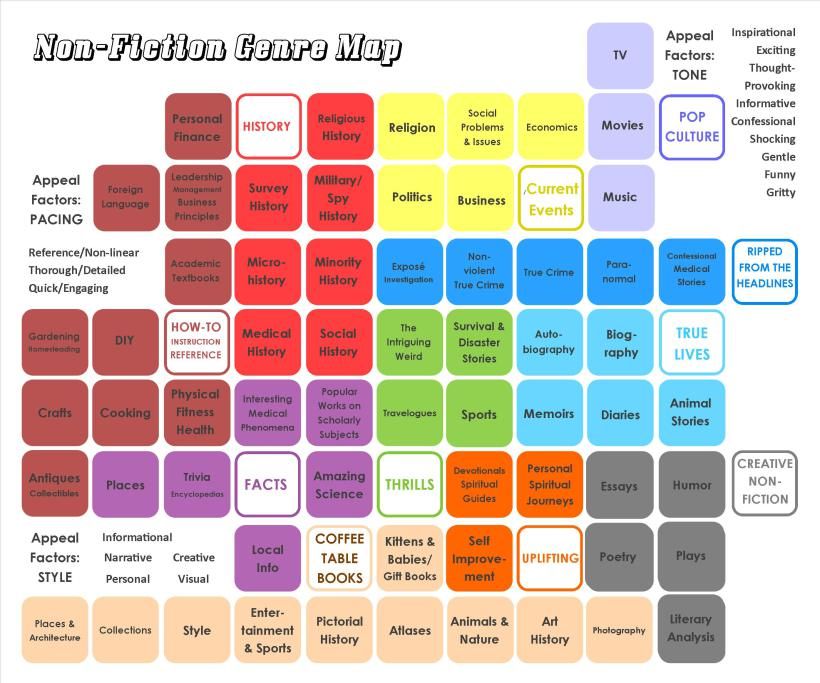

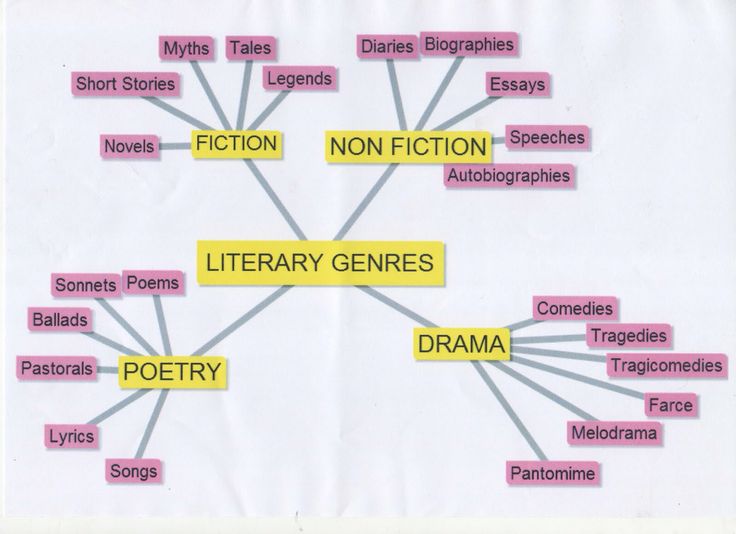

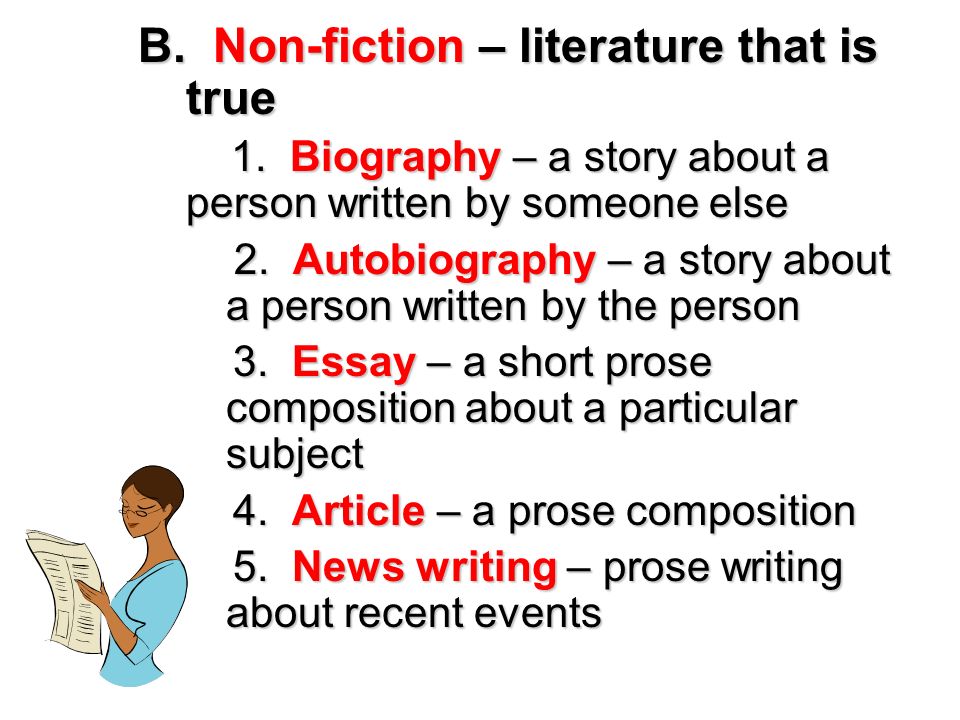

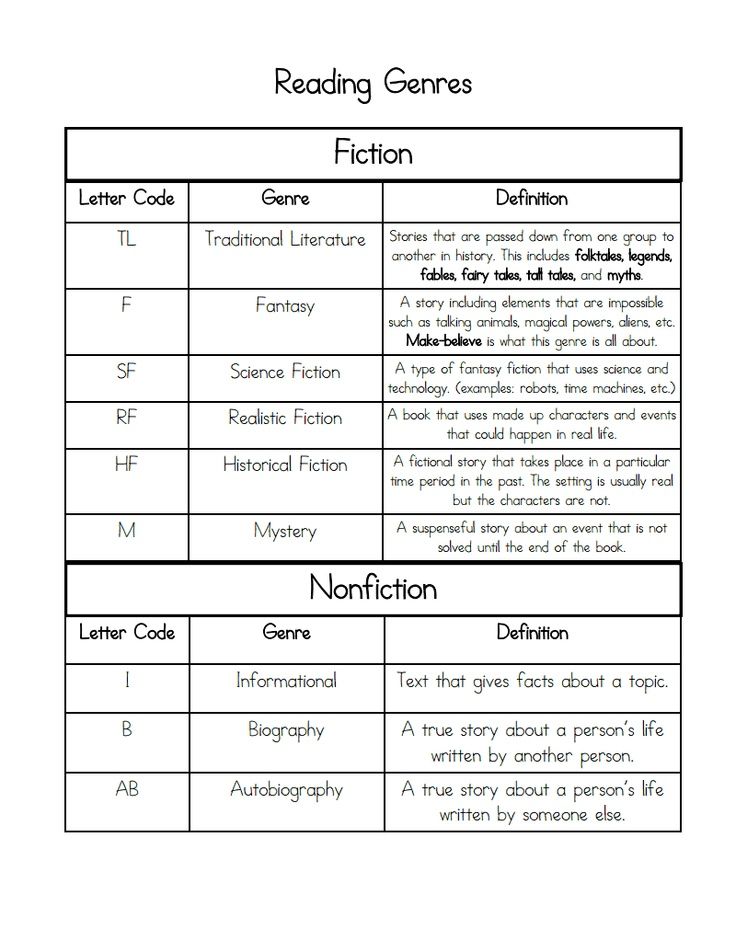

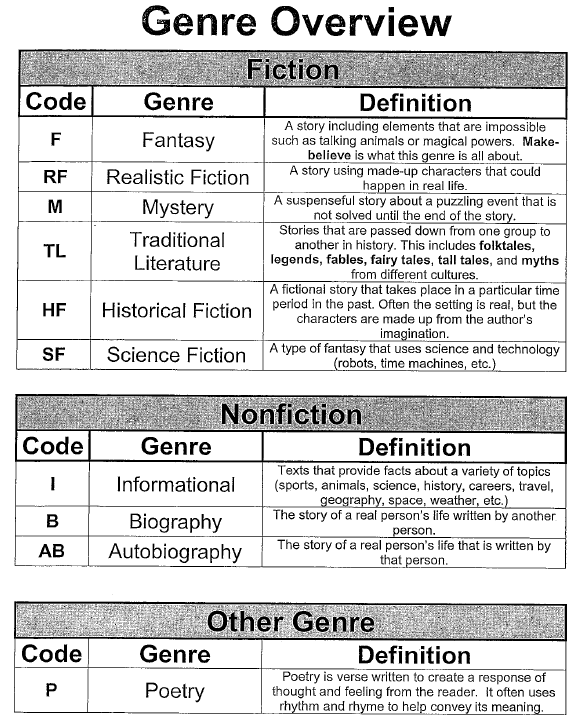

Because the nature of nonfiction is entirely factual, it must contain categories that differ from those within fiction. Nonfiction genres include:

- History: True accounts of historical events, including true crime novels. Example: Midnight in Chernobyl by Adam Higginbotham

- Biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs: Focuses on facts and events of the subject's life story. Biographies are accounts written by someone else, autobiographies are written by the subject, and a memoir is a historical account based on the author's personal memories.

Example: Know My Name by Chanel Miller

Example: Know My Name by Chanel Miller - Travel guides and travelogues: Travelogues tell the author's specific experience while traveling somewhere while travel guides are more practical and instructive, offering suggestions for travelers heading to a specific destination. Example: A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail by Bill Bryson

- Academic texts: Designed to educate readers on a particular subject. Example: A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking. All the textbooks used to teach specific subjects in schools are also academic nonfiction texts.

- Self-help and instruction: These books provide informative tips to bettering one's self in a variety of ways, including business success, confidence, organization, relationship advice, healthy living, financial management and more. Example: Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones by James Clear

- Guides and how-to manuals: Similar to the above category, but more focused on a single skill.

A couple of examples are cookbooks and tutorials for at-home hobbies. Example: Joshua Weissman: An Unapologetic Cookbook by Joshua Weissman

A couple of examples are cookbooks and tutorials for at-home hobbies. Example: Joshua Weissman: An Unapologetic Cookbook by Joshua Weissman

Nonfiction Genre

The nonfiction genre encompasses a number of categories. Truman Capote claims to have invented the genre with his 1966 novel, In Cold Blood, the true crime story of the murder of a rural Kansas family. Capote spent six years researching and interviewing neighbors, friends and the two convicted murderers. He tells the story from the different points of view of the characters and avoids including his own opinions or false information, though after publication he was criticized for lack of objectivity and including facts that were later proven to be false. While it is always the goal for nonfiction writers to be objective, authors frequently add in conversations or thoughts in a way that supports the story, though it contradicts the goal of total objectivity. News reports do not fit into this category because reporters do not have the license to be creative. A news report must contain facts and have recorded evidence to back up everything they say.

A news report must contain facts and have recorded evidence to back up everything they say.

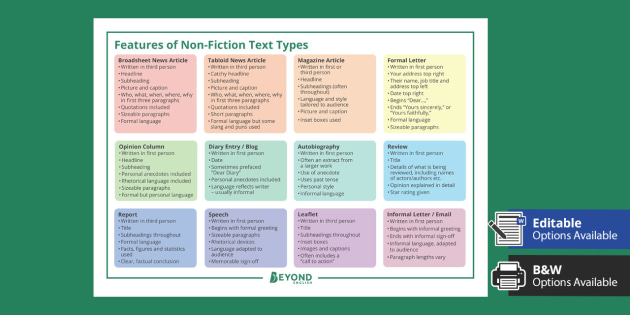

Types of Nonfiction

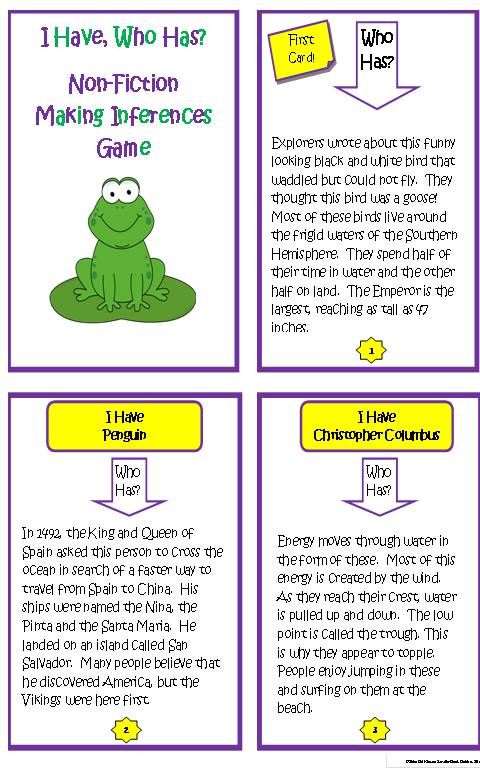

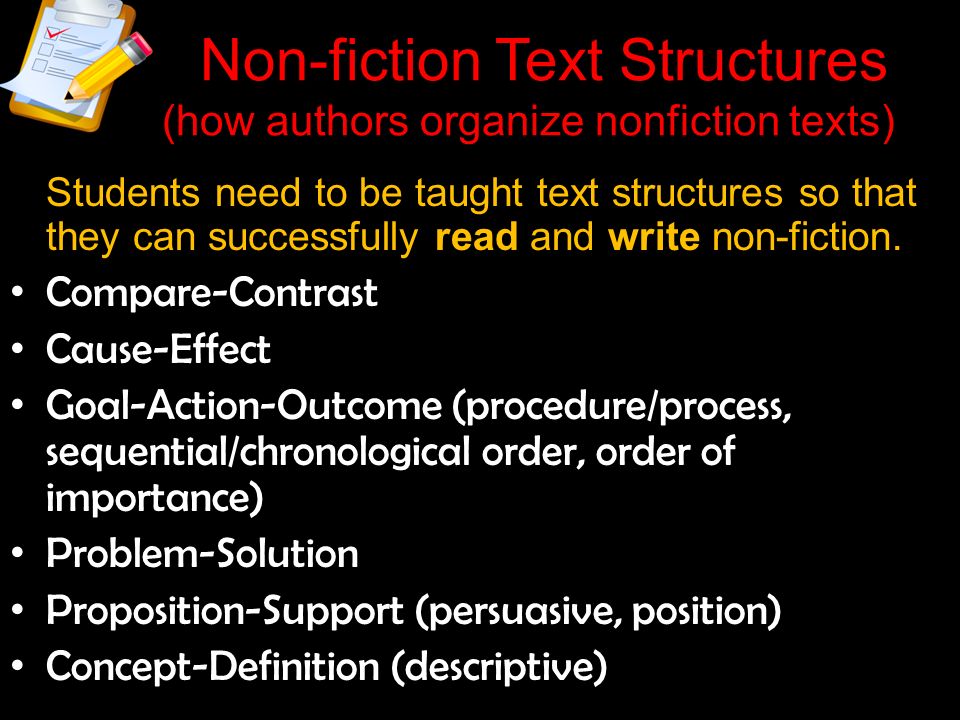

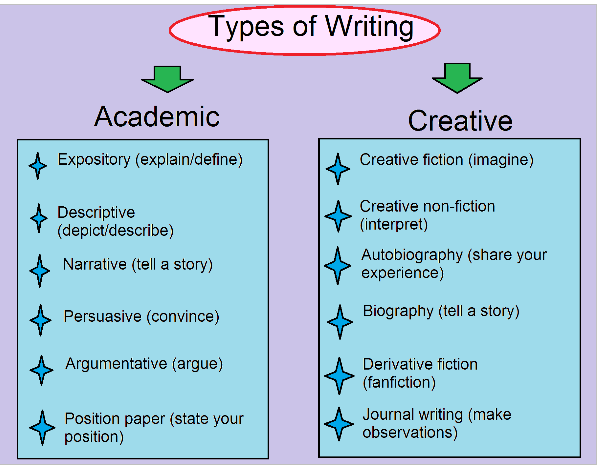

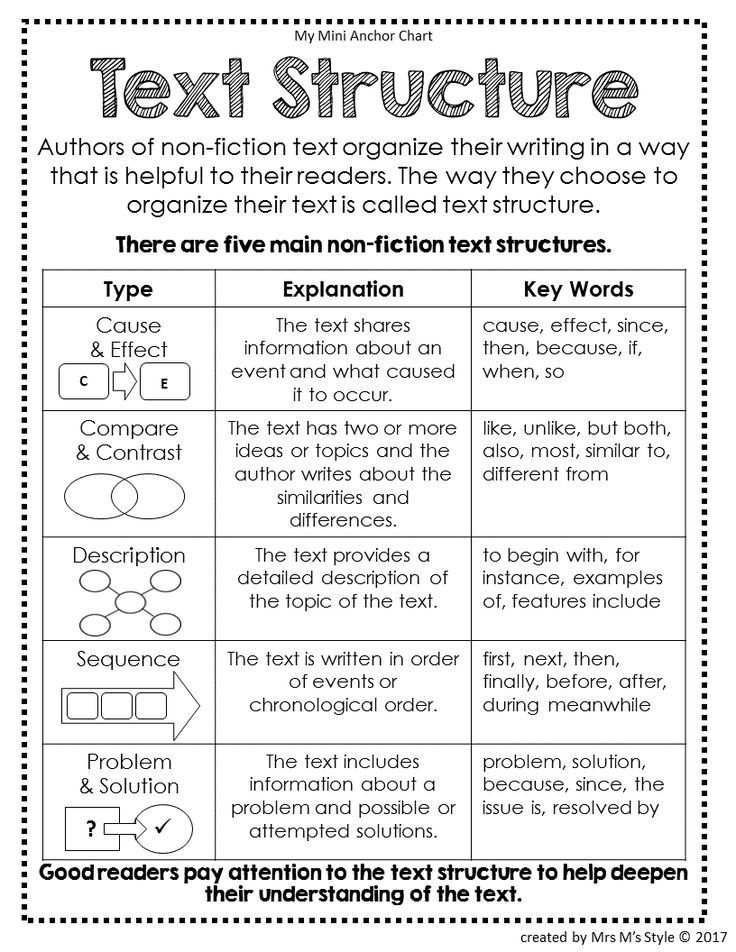

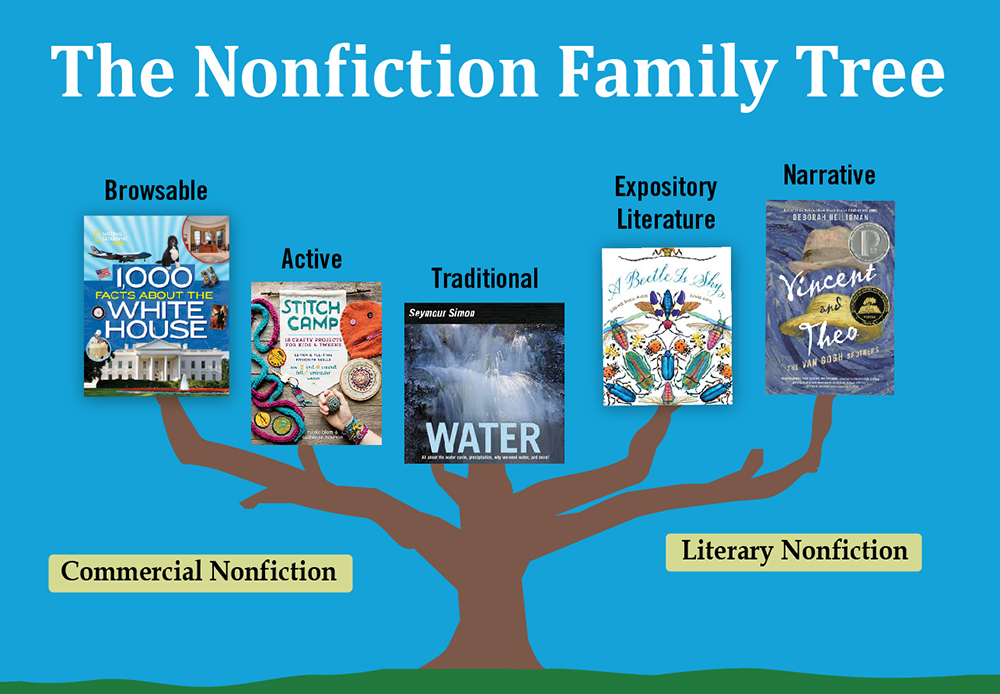

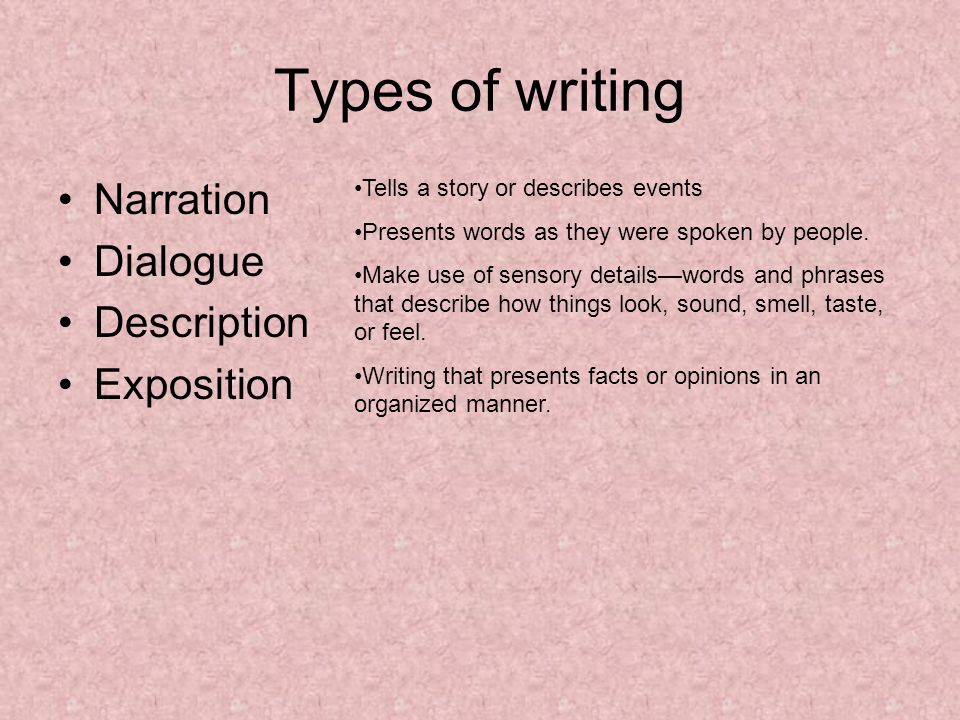

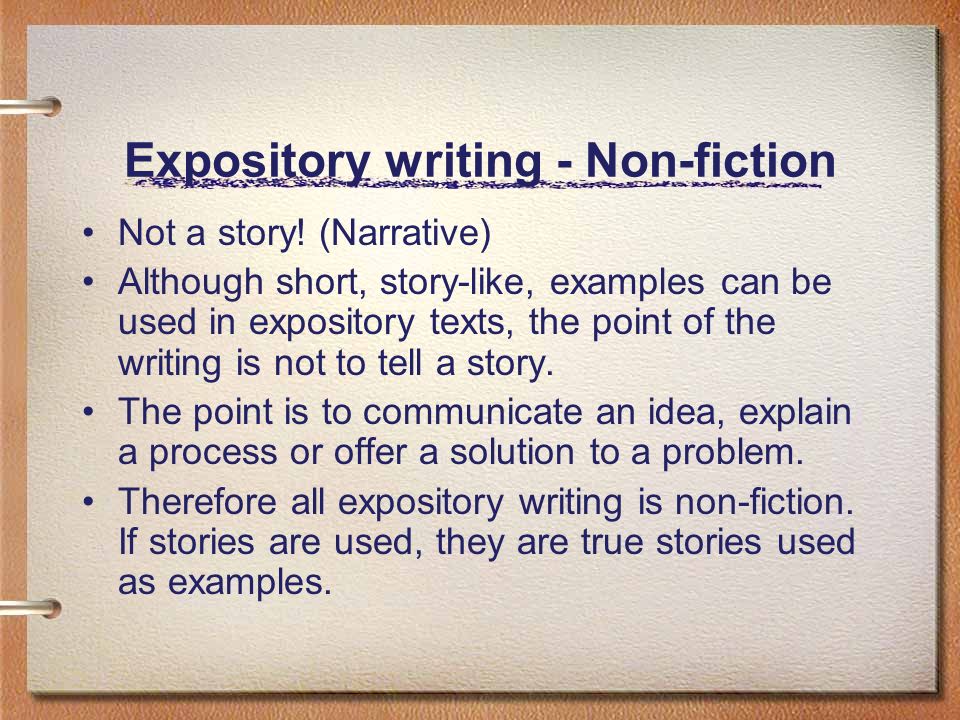

There are three different types of nonfiction writing: expository nonfiction, argumentative nonfiction, and narrative nonfiction. The difference between the three is not in the validity of the information provided, but in the manner in which it is presented.

- Narrative nonfiction tells a chronological story, complete with real characters, setting and plot. It draws on the writer's own life experiences is often used in combination with informational (expository) passages to provide the reader with a deeper understanding of the story.

- Expository nonfiction is informational writing used to explain, describe and inform readers about a specific topic. Expository writing requires research to ensure accuracy.

- Argumentative nonfiction is persuasive or opinionated writing where the writer makes a claim and gathers evidence to back up their argument through research.

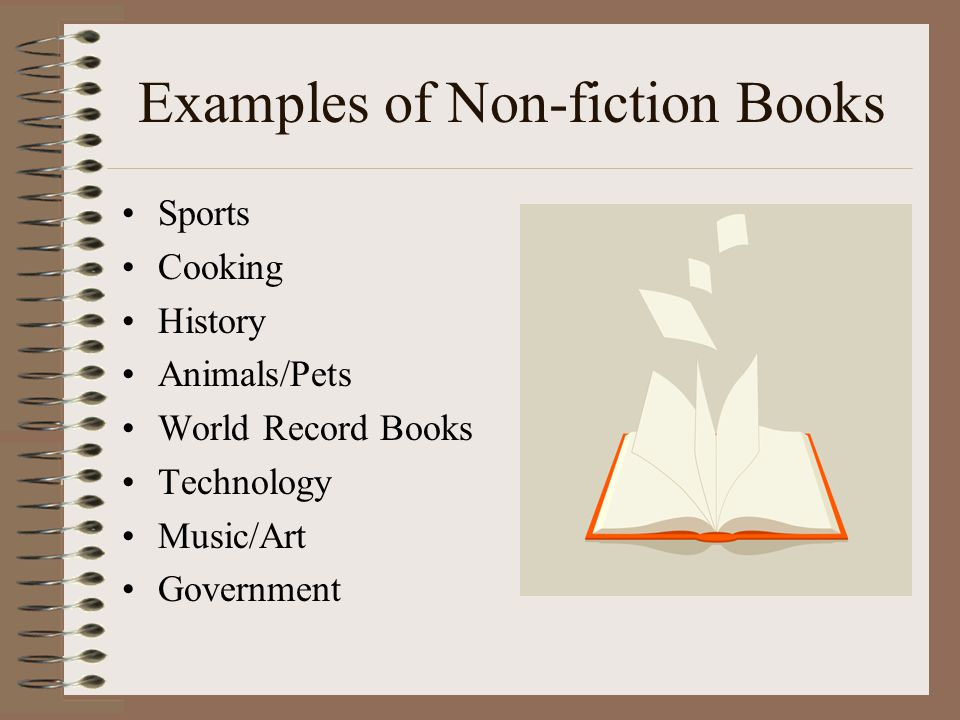

Examples of Nonfiction Books

There are several categories of nonfiction spanning a variety of genres. Below are some examples of nonfiction books, including nonfiction novels, scientific pieces, and autobiographical works:

Into the Wild, Jon Krakauer, 1996 - A novel about a young man named Chris who took to the road after college, leaving behind his old life in search of freedom from societal expectation. Two years after he embarked on his trip, his body was found in Alaska on a bus he used as a shelter. Into the Wild explains who Chris was, pieces together his journey, and explores why he died.

The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank, 1947 - A book of journal entries from the diary kept by Anne Frank, a young girl who hid with her family for two years during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption, Laura Hillenbrand, 2014 - The story of a young man who fought to survive unthinkable hardships during WWII.

On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin, 1859 - One of the most important works of scientific study ever published. In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin writes his theories of evolution by natural selection.

The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud, 1899 - In this book, Freud introduces his theory of the unconscious regarding dream interpretation, explaining why we dream and why dreams matter.

Lesson Summary

Fictional writing is imaginative, created by the author with the purpose of entertaining the readers. Nonfiction writing is based on fact and must present information objectively, without the opinion of the author present. While novels are most commonly fictional works, a novel can be nonfiction. Nonfiction novels depict real historical events and real people in combination with the craft of fictional storytelling. Truman Capote is said to have invented the nonfiction genre with his 1959 novel, In Cold Blood, a true-crime novel about the murder of a rural Kansas family.

While novels are most commonly fictional works, a novel can be nonfiction. Nonfiction novels depict real historical events and real people in combination with the craft of fictional storytelling. Truman Capote is said to have invented the nonfiction genre with his 1959 novel, In Cold Blood, a true-crime novel about the murder of a rural Kansas family.

The nonfiction genre includes many types of books, including self-help, historical, biographies, academic texts, travelogues and more. Types of nonfiction writing include expository (informational), argumentative (persuasive), and narrative, which tells a story. It is important that the author fact-checks rigorously when writing nonfiction; if an author publishes information about a person that is false, the author can be sued for libel. While news reports are factual, news reporters have no license to creativity, so their work would not be considered a nonfiction piece. Some examples of nonfiction books are: Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer, The Diary of a Young Girl, a collection of diary entries by Anne Frank, A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, and, of course, In Cold Blood by Truman Capote.

What's Okay for Fiction, but Not for Nonfiction

Making Things Up

In fiction, there is no demand for fact checking. While it can be helpful, it is not necessary because a fictitious novel can make up anything and everything. In a nonfiction novel, however, fact checking is imperative. The trick with writing a nonfiction novel is to balance the truth with creativity. Because of this, it is up to the writer to make sure the events captured cannot be countered or disproven. If it can be disproven, especially if the information is about a person still living, the writer can be sued for libel, which is the public defamation of a person.

Being Indirect

In fiction, it's okay to be indirect, to let the readers work their own ways through symbolism and abstractions. However, readers of nonfiction expect the writer to be more direct about time, truth, and other information.

Inserting Opinion Over Fact

In fiction, the writer does not need to worry about truth and therefore paints whatever opinion of the story he or she chooses. However, in nonfiction, it is vital that the writer understand the information that he or she is providing, and therefore, how best to present the information. It is up to the writer to show the information and tell the readers what to think about the information.

Famous Examples

In Cold Blood describes the true events of a family murdered and the events that followed. What made this novel so famous is that it is told from the killers' points of view. Capote visited the killers in jail for several years to get their stories, developing his novel from their interviews. The purpose of his novel was to depict such horrific events in a new light, by creating a relationship between reader and killer, establishing even a sense of empathy for the killers.

Due to Capote's self-proclaimed brilliant new genre, his novel and its 'real-life events' depicted came under much scrutiny. After fact checking his novel, mistakes were eventually discovered in the way the true events were described. Though no legal action was taken, it is imperative that both the writer and editor catch any aspect of the nonfiction novel that can be disproved.

After fact checking his novel, mistakes were eventually discovered in the way the true events were described. Though no legal action was taken, it is imperative that both the writer and editor catch any aspect of the nonfiction novel that can be disproved.

Another famous nonfiction novel is Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, written by Eric Schlosser in 2001. In this novel, investigative journalist Schlosser scrutinizes the effects of fast food in America. Schlosser intertwines historical and present-day facts with grotesque and witty descriptions to get across his main point--that fast food is ruining the nation. The novel's popularity eventually led to a screenplay and then a movie in 2006.

Other Famous Nonfiction Novels

- Hiroshima (1946) by John Hersey. Synopsis: Journalist Hersey documents six survivors' accounts of the day the first atomic bomb hit the city of Hiroshima.

- The Diary of a Young Girl (1952) by Anne Frank. Synopsis: Taken from the Dutch writings of Anne Frank's diary, in which she describes her life in hiding from the Nazis in World War II.

- Why We Can't Wait (1964) by Martin Luther King, Jr. Synopsis: MLK explores the historical events leading up to the Civil Rights Movement.

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) by Maya Angelou. Synopsis: Angelou's autobiography capturing her and her brother's struggle through childhood.

- A Brief History of Time (1988) by Stephen Hawking. Synopsis: Hawking, a world-famous scientist, examines the science of cosmology, which is the exploration of the universe's origin.

- A Child Called 'It': One Child's Courage to Survive (1995) by Dave Pelzer. Synopsis: Pelzer describes in gory detail his experiences with his childhood abuse, one of the worst documented cases of child neglect and abuse in California to date.

Summary

A nonfiction novel depicts real-life events in a creative and literary way. The writer uses literary techniques to establish drama and intrigue, but keeps the story true and accurate. This requires the writer to execute extensive fact checking and direct language. While Truman Capote is famous for creating the genre, many novels have been written throughout time and utilize many techniques of nonfiction.

The writer uses literary techniques to establish drama and intrigue, but keeps the story true and accurate. This requires the writer to execute extensive fact checking and direct language. While Truman Capote is famous for creating the genre, many novels have been written throughout time and utilize many techniques of nonfiction.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member.

Create your account

Definition

Nonfiction is a genre in literature in which real events are depicted using story-telling techniques. Though the people and situations written about are true, the writer has creative license with how to tell the story. This makes the genre's definition rather flexible. Many nonfiction novels are written in such categories as biographies, historical events, travel, science, religion, philosophy, and art.

While some critics argue nonfiction has been around for centuries, Truman Capote claimed to have been the creator of this genre with his 1966 crime novel In Cold Blood. Whether or not Capote created the genre, he did give it a name. He claims the genre was inspired by his idea to integrate narrative journalistic reportage and creative writing techniques. However, unlike journalism, his idea of nonfiction would rely on creative writing to tell factual events, and rather than imbedding himself into the story, he would imply his credibility through his use of empathy and truth of the events.

Whether or not Capote created the genre, he did give it a name. He claims the genre was inspired by his idea to integrate narrative journalistic reportage and creative writing techniques. However, unlike journalism, his idea of nonfiction would rely on creative writing to tell factual events, and rather than imbedding himself into the story, he would imply his credibility through his use of empathy and truth of the events.

What's Okay for Fiction, but Not for Nonfiction

Making Things Up

In fiction, there is no demand for fact checking. While it can be helpful, it is not necessary because a fictitious novel can make up anything and everything. In a nonfiction novel, however, fact checking is imperative. The trick with writing a nonfiction novel is to balance the truth with creativity. Because of this, it is up to the writer to make sure the events captured cannot be countered or disproven. If it can be disproven, especially if the information is about a person still living, the writer can be sued for libel, which is the public defamation of a person.

If it can be disproven, especially if the information is about a person still living, the writer can be sued for libel, which is the public defamation of a person.

Being Indirect

In fiction, it's okay to be indirect, to let the readers work their own ways through symbolism and abstractions. However, readers of nonfiction expect the writer to be more direct about time, truth, and other information.

Inserting Opinion Over Fact

In fiction, the writer does not need to worry about truth and therefore paints whatever opinion of the story he or she chooses. However, in nonfiction, it is vital that the writer understand the information that he or she is providing, and therefore, how best to present the information. It is up to the writer to show the information and tell the readers what to think about the information.

Famous Examples

In Cold Blood describes the true events of a family murdered and the events that followed. What made this novel so famous is that it is told from the killers' points of view. Capote visited the killers in jail for several years to get their stories, developing his novel from their interviews. The purpose of his novel was to depict such horrific events in a new light, by creating a relationship between reader and killer, establishing even a sense of empathy for the killers.

Capote visited the killers in jail for several years to get their stories, developing his novel from their interviews. The purpose of his novel was to depict such horrific events in a new light, by creating a relationship between reader and killer, establishing even a sense of empathy for the killers.

Due to Capote's self-proclaimed brilliant new genre, his novel and its 'real-life events' depicted came under much scrutiny. After fact checking his novel, mistakes were eventually discovered in the way the true events were described. Though no legal action was taken, it is imperative that both the writer and editor catch any aspect of the nonfiction novel that can be disproved.

Another famous nonfiction novel is Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, written by Eric Schlosser in 2001. In this novel, investigative journalist Schlosser scrutinizes the effects of fast food in America. Schlosser intertwines historical and present-day facts with grotesque and witty descriptions to get across his main point--that fast food is ruining the nation. The novel's popularity eventually led to a screenplay and then a movie in 2006.

The novel's popularity eventually led to a screenplay and then a movie in 2006.

Other Famous Nonfiction Novels

- Hiroshima (1946) by John Hersey. Synopsis: Journalist Hersey documents six survivors' accounts of the day the first atomic bomb hit the city of Hiroshima.

- The Diary of a Young Girl (1952) by Anne Frank. Synopsis: Taken from the Dutch writings of Anne Frank's diary, in which she describes her life in hiding from the Nazis in World War II.

- Why We Can't Wait (1964) by Martin Luther King, Jr. Synopsis: MLK explores the historical events leading up to the Civil Rights Movement.

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) by Maya Angelou. Synopsis: Angelou's autobiography capturing her and her brother's struggle through childhood.

- A Brief History of Time (1988) by Stephen Hawking.

Synopsis: Hawking, a world-famous scientist, examines the science of cosmology, which is the exploration of the universe's origin.

Synopsis: Hawking, a world-famous scientist, examines the science of cosmology, which is the exploration of the universe's origin. - A Child Called 'It': One Child's Courage to Survive (1995) by Dave Pelzer. Synopsis: Pelzer describes in gory detail his experiences with his childhood abuse, one of the worst documented cases of child neglect and abuse in California to date.

Summary

A nonfiction novel depicts real-life events in a creative and literary way. The writer uses literary techniques to establish drama and intrigue, but keeps the story true and accurate. This requires the writer to execute extensive fact checking and direct language. While Truman Capote is famous for creating the genre, many novels have been written throughout time and utilize many techniques of nonfiction.

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member.

Create your account

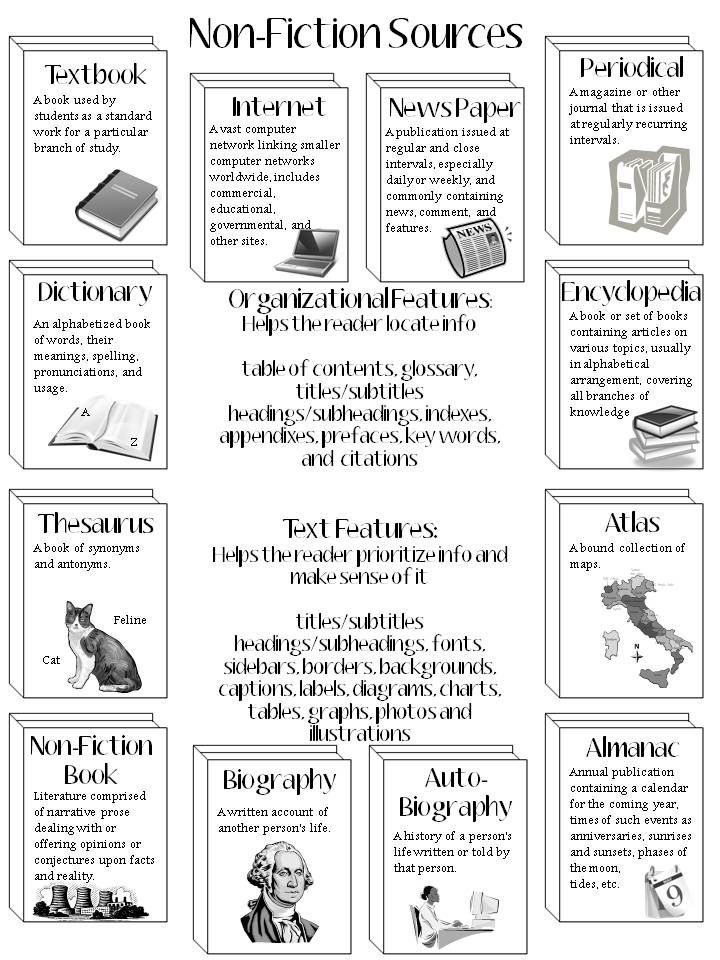

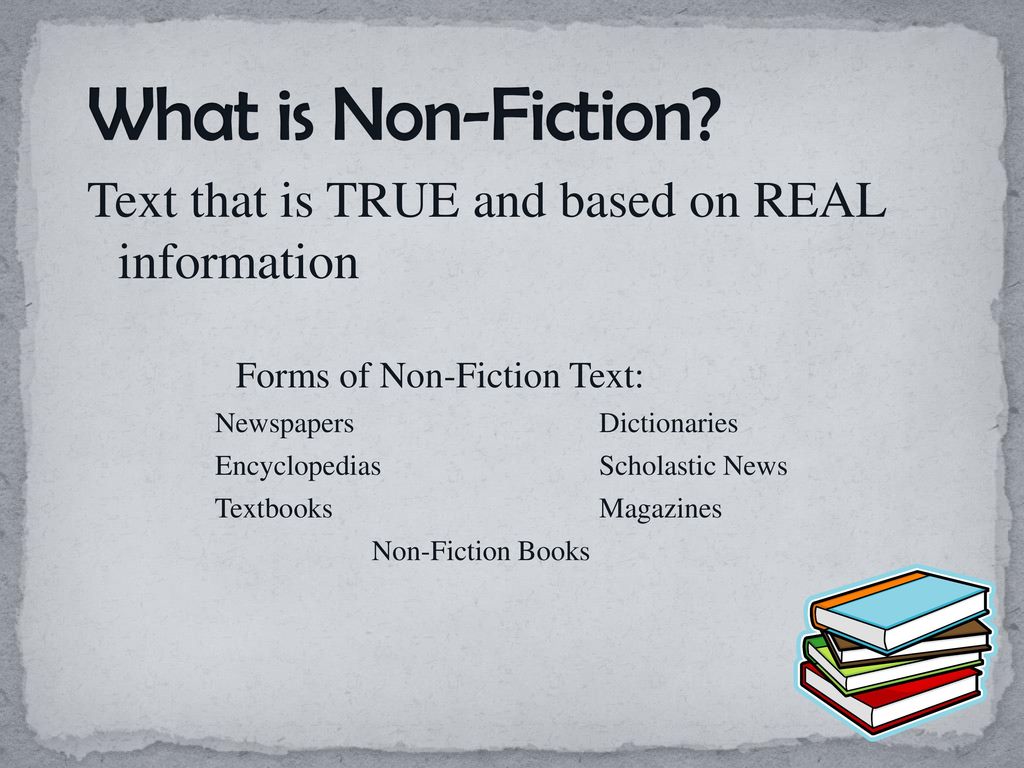

What are nonfiction books?

"Nonfiction" refers to fact-based works of literature that are written about people or events that actually occurred. Some examples of nonfiction categories include biographies, cooking, health and fitness, home improvement, travel, self-help and true crime.

Some examples of nonfiction categories include biographies, cooking, health and fitness, home improvement, travel, self-help and true crime.

What are some examples of nonfiction?

A nonfiction book is a factual work based on actual people, places, or events. Examples of popular nonfiction novels are Into the Wild and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil: A Savannah Story. Other nonfiction genres include biographies, historical texts, academic texts and self-help books, to name a few.

Register to view this lesson

Are you a student or a teacher?

Unlock Your Education

See for yourself why 30 million people use Study.com

Become a Study.com member and start learning now.

Become a Member

Already a member? Log In

Back

Resources created by teachers for teachers

Over 30,000 video lessons & teaching resources‐all in one place.

Video lessons

Quizzes & Worksheets

Classroom Integration

Lesson Plans

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

Jennifer B.

Teacher

Try it now

Back

The 20 Best Works of Nonfiction of the Decade ‹ Literary Hub

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels, the best short story collections, the best poetry collections, the best memoirs of the decade, and the best essay collections of the decade. But our sixth list was a little harder—we were looking at what we (perhaps foolishly) deemed “general” nonfiction: all the nonfiction excepting memoirs and essays (these being covered in their own lists) published in English between 2010 and 2019.

Reader, we cheated. We picked a top 20. It only made sense, with such a large field. And 20 isn’t even enough, really. But so it goes, in the world of lists.

It only made sense, with such a large field. And 20 isn’t even enough, really. But so it goes, in the world of lists.

The following books were finally chosen after much debate (and multiple meetings) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

***

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow (2010)I read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow when it first came out, and I remember its colossal impact so clearly—not just on the academic world (it is, technically, an academic book, and Alexander is an academic) but everywhere. It was published during the Obama Administration, an interval which many (white people) thought signaled a new dawn of race relations in America—of a kind of fantastic post-racialism. Though it’s hard to look back on this particular zeitgeist now (when, and I still can’t believe I’m writing this, Donald Trump is president of the United States) without decrying the ignorance and naiveté of this mindset, Alexander’s book called out this the insistence on a phenomenon of “colorblindness” in 2012, as a veneer, as a sham, or as, simply, another form of ignorance. “We have not ended racial caste in America,” she declares, “we have merely redesigned it.” Alexander’s meticulous research concerns the mass incarceration of black men principally through the War on Drugs, Alexander explains how the United States government itself (the justice system) carries out a significant racist pattern of injustice—which not only literally subordinates black men by jailing them, but also then removes them of their rights and turns them into second class citizens after the fact. Former convicts, she learns through working with the ACLU, will face discrimination (discrimination that is supported and justified by society) which includes restrictions from voting rights, juries, food stamps, public housing, student loans—and job opportunities.

Though it’s hard to look back on this particular zeitgeist now (when, and I still can’t believe I’m writing this, Donald Trump is president of the United States) without decrying the ignorance and naiveté of this mindset, Alexander’s book called out this the insistence on a phenomenon of “colorblindness” in 2012, as a veneer, as a sham, or as, simply, another form of ignorance. “We have not ended racial caste in America,” she declares, “we have merely redesigned it.” Alexander’s meticulous research concerns the mass incarceration of black men principally through the War on Drugs, Alexander explains how the United States government itself (the justice system) carries out a significant racist pattern of injustice—which not only literally subordinates black men by jailing them, but also then removes them of their rights and turns them into second class citizens after the fact. Former convicts, she learns through working with the ACLU, will face discrimination (discrimination that is supported and justified by society) which includes restrictions from voting rights, juries, food stamps, public housing, student loans—and job opportunities. “Unlike in Jim Crow days, there were no ‘Whites Only’ signs.” Alexander explains. “This system is out of sight, out of mind.” Her book, which exposes this subtler but still horrible new mode of social control, is an essential, groundbreaking achievement which does more than call out the hypocrisy of our infrastructure, but provide it with obvious steps to change. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

“Unlike in Jim Crow days, there were no ‘Whites Only’ signs.” Alexander explains. “This system is out of sight, out of mind.” Her book, which exposes this subtler but still horrible new mode of social control, is an essential, groundbreaking achievement which does more than call out the hypocrisy of our infrastructure, but provide it with obvious steps to change. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies (2010)

In this riveting (despite its near 600 pages) and highly influential book, Mukherjee traces the known history of our most feared ailment, from its earliest appearances over five thousand years ago to the wars still being waged by contemporary doctors, and all the confusion, success stories, and failures in between—hence the subtitle “a biography of cancer,” though of course it is also a biography of humanity and of human ingenuity (and lack thereof).

Mukherjee began to write the book after a striking interaction with a patient who had stomach cancer, he told The New York Times. “She said, ‘I’m willing to go on fighting, but I need to know what it is that I’m battling.’ It was an embarrassing moment. I couldn’t answer her, and I couldn’t point her to a book that would. Answering her question—that was the urgency that drove me, really. The book was written because it wasn’t there.”

“She said, ‘I’m willing to go on fighting, but I need to know what it is that I’m battling.’ It was an embarrassing moment. I couldn’t answer her, and I couldn’t point her to a book that would. Answering her question—that was the urgency that drove me, really. The book was written because it wasn’t there.”

His work was certainly appreciated. The Emperor of All Maladies won the 2011 Pulitzer in General Nonfiction (the jury called it “An elegant inquiry, at once clinical and personal, into the long history of an insidious disease that, despite treatment breakthroughs, still bedevils medical science.”), the Guardian first book award, and the inaugural PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award; it was a New York Times bestseller. But most importantly, it was the first book many laypeople (read: not scientists, doctors, or those whose lives had already been acutely affected by cancer) had read about the most dreaded of all diseases, and though the science marches on, it is still widely read and referenced today. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

As a strongly humanities-focused person, it’s difficult for me to connect with books about science. What can I say besides that public education and I failed each other. When I read The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I found myself thinking that if all scientific knowledge were part of this kind of incredibly compelling and human narrative, I would probably be a doctor by now. (I mean, it’s possible.) Rebecca Skloot tells the story of Henrietta Lacks, a black woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951, and her cells (dubbed HeLa cells) which were cultured without her permission, and which were the first human cells to reproduce in a lab—making them immensely valuable to scientists in research labs all over the world. HeLa cells have been used for the development of vaccines and treatments as well as in drug treatments, gene mapping, and many, many other scientific pursuits. They were even sent to space so scientists could study the effects of zero gravity on human cells.

They were even sent to space so scientists could study the effects of zero gravity on human cells.

Skloot set a wildly ambitious project for herself with this book. Not only does she write about the (immortal) life of the cells as well as the lives of Lacks and her (human, not just cellular) descendants, she also writes about the racism in the medical field and medical ethics as a whole. That the book feels cohesive as well as compelling is a great testament to Skloot’s skills as a writer. “Immortal Life reads like a novel,” writes Eric Roston in his Washington Post review. “The prose is unadorned, crisp and transparent.” For a book that encompasses so much, it never feels baggy. Nearly ten years later, it remains an urgent text, and one that is taught in high schools, universities, and medical schools across the country. It is both an incredible achievement and, simply, a really good read. –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands (2010)

Timothy Snyder’s brilliant Bloodlands has changed World War II scholarship more, perhaps, than any work since Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, an apt comparison given that Bloodlands includes within it a response to Arendt’s theory of the banality of evil (Snyder doesn’t buy it, and provides convincing proof that Eichmann was more of a run-of-the-mill hateful Nazi and less a colorless bureaucrat simply doing his job). Snyder reads in 10 languages, which is key to his ability to synthesize international scholarship and present new theories in an accessible way. But before I continue praising this book, I should probably let y’all know what it’s about—Bloodlands is a history of mass killings in the Double-Occupied Zone of Eastern Europe, where the Soviets showed up, killed everyone they wanted to, and then the Nazis showed up and killed everyone else. By focusing on mass killings, rather than genocide, Snyder is able to draw connections between totalitarian regimes and examine the mechanisms by which small nations can suddenly and horrifyingly become much smaller. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Snyder reads in 10 languages, which is key to his ability to synthesize international scholarship and present new theories in an accessible way. But before I continue praising this book, I should probably let y’all know what it’s about—Bloodlands is a history of mass killings in the Double-Occupied Zone of Eastern Europe, where the Soviets showed up, killed everyone they wanted to, and then the Nazis showed up and killed everyone else. By focusing on mass killings, rather than genocide, Snyder is able to draw connections between totalitarian regimes and examine the mechanisms by which small nations can suddenly and horrifyingly become much smaller. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010)

Wilkerson’s history of the Great Migration is a revelation. When we talk about migration in the context of American history, we tend to focus on triumphalist stories of immigrants coming to America, but what about the vast migrations that have happened internally? Between 1920 and 1970, millions of African-Americans migrated North from the prejudice-ridden South, lured by relatively high-paying jobs and relatively less racism. It takes a whole lot to make someone leave their home, and Wilkerson does an excellent job at reminding us how awful life in the South was for Black people (and still is, in many ways). The Warmth of Other Suns is not only fascinating—it’s also thrilling, taking us into the lives of hard-scrabble folk who were equal parts refugees and adventurers, and truly epic, telling a great story on a grand scale. Don’t think that means there aren’t small moments of humanity seeded throughout the book—for every sentence about the conduct of millions, there’s a detail that reminds us that we’re reading about individuals, with their own hopes, wishes, dreams, and struggles. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

It takes a whole lot to make someone leave their home, and Wilkerson does an excellent job at reminding us how awful life in the South was for Black people (and still is, in many ways). The Warmth of Other Suns is not only fascinating—it’s also thrilling, taking us into the lives of hard-scrabble folk who were equal parts refugees and adventurers, and truly epic, telling a great story on a grand scale. Don’t think that means there aren’t small moments of humanity seeded throughout the book—for every sentence about the conduct of millions, there’s a detail that reminds us that we’re reading about individuals, with their own hopes, wishes, dreams, and struggles. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Robert A. Caro, The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson (2012)

While Robert Caro first came to prominence for The Powerbroker, his 1974 biography of divisive urban planner Robert Moses, it’s Caro’s ongoing multi-volume biography of LBJ, America’s most unjustly maligned president (fight me, Kennedy-heads!), that has cemented his legacy. It’s hard to pick one in particular to recommend, but The Passage of Power, which covers the years 1958-1964, captures the most tumultuous period of LBJ’s life in politics, as he went from feared senator, to side-lined VP, to suddenly becoming the post powerful figure in the world. There’s something profoundly moving about the vastness of these works—Caro is 83 now, and has dedicated an enormous part of his life to this singular project. His wife is his only approved research assistant, and together, they’ve upended half a century of LBJ criticism to reveal the complex, problematic, but always striving core of a sensitive soul.

It’s hard to pick one in particular to recommend, but The Passage of Power, which covers the years 1958-1964, captures the most tumultuous period of LBJ’s life in politics, as he went from feared senator, to side-lined VP, to suddenly becoming the post powerful figure in the world. There’s something profoundly moving about the vastness of these works—Caro is 83 now, and has dedicated an enormous part of his life to this singular project. His wife is his only approved research assistant, and together, they’ve upended half a century of LBJ criticism to reveal the complex, problematic, but always striving core of a sensitive soul.

I had a teacher in high school who spent 20 years working on her dissertation on LBJ. She’d spend each weekend at the LBJ Library at UT Austin, while working full time as a public school teacher, and kicked ass at both. There’s something about LBJ that inspires people to dedicate their entire lives to trying to figure him out, and in the process, trying to understand the world that made him, and that he made. Thanks to Caro, we can all understand LBJ a little bit better. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Thanks to Caro, we can all understand LBJ a little bit better. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Tom Reiss, The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (2012)

Tom Reiss opens his biography of Thomas Alexandre-Dumas, father of author Alexandre Dumas, with a scene that seems right out of an academic heist film. At a library in rural France, Reiss convinces a town official to blow open a safe whose combination was held only by the late librarian. What Reiss discovers are the rudiments of a grand and, until then, largely unknown story of the man who inspired some of his son’s most beloved tales. The Black Count is also a case study of complex racial politics during the age of revolutionary France. Dumas was born in 1762 in Saint-Domingue, the French Caribbean colony that would become Haiti. As the son of a French marquis and a freed black slave, Dumas was subject both to the privileges of the former and the kind of indignities suffered by the latter. His father, for instance, sells him into slavery when he is 12 only to purchase his freedom later and bring him to France, where the young man receives an aristocratic education. A final rift from his father prompts Dumas to join the military. Reiss creates a dynamic, if somewhat speculative portrait of Dumas based on letters, reports from battlefields, Dumas’ own writings, and more. By the time he is 30, Dumas has vaulted in the ranks from corporal to general and commands a division of more than 50,000 soldiers. It’s no accident that the thrilling militaristic feats Reiss describes sound like events out of The Count of Monte Cristo or The Three Musketeers. Though the general becomes a cavalry commander under Napoleon Bonaparte, Reiss suggests that it was Napoleon himself who ruined Dumas not only from a personal standpoint, but civilizational as well. Napoleon reintroduced slavery in Haiti, after all, in contradiction to the republican dreams of Dumas’ contemporary, Toussaint Louverture, another rare and successful 18th-century general of African descent.

His father, for instance, sells him into slavery when he is 12 only to purchase his freedom later and bring him to France, where the young man receives an aristocratic education. A final rift from his father prompts Dumas to join the military. Reiss creates a dynamic, if somewhat speculative portrait of Dumas based on letters, reports from battlefields, Dumas’ own writings, and more. By the time he is 30, Dumas has vaulted in the ranks from corporal to general and commands a division of more than 50,000 soldiers. It’s no accident that the thrilling militaristic feats Reiss describes sound like events out of The Count of Monte Cristo or The Three Musketeers. Though the general becomes a cavalry commander under Napoleon Bonaparte, Reiss suggests that it was Napoleon himself who ruined Dumas not only from a personal standpoint, but civilizational as well. Napoleon reintroduced slavery in Haiti, after all, in contradiction to the republican dreams of Dumas’ contemporary, Toussaint Louverture, another rare and successful 18th-century general of African descent. Reiss unearths the ultimately tragic story of a man who was infamous in his own time for enjoying social and professional advantages that would’ve been unheard of for a mixed-race man in the US, a nation which of course went through its own revolution one generation earlier. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Reiss unearths the ultimately tragic story of a man who was infamous in his own time for enjoying social and professional advantages that would’ve been unheard of for a mixed-race man in the US, a nation which of course went through its own revolution one generation earlier. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction (2014)

The premise of Elizabeth Kolbert’s Pulitzer-prize-winning book is a simple scientific fact: there have been five mass extinctions in the history of the planet, and soon there will be six. The difference, Kolbert explains, is that this one is caused by humans, who have drastically altered the earth in a short time. She points out on the first page that humans (which is to say, homo sapiens, humans like us) have only been around for two hundred thousand or so years—an incredibly short amount of time to do damage enough to destroy most of earthly life. Kolbert’s book is so unique, though, because she combines research from across disciplines (scientific and social-scientific) to prepare an extremely comprehensive, sweeping argument about how our oceans, air, animal populations, bacterial ecosystems, and other natural elements are dangerously adapting to (or dying from) human impact, while also tracing the history of both the approaches to these things (theories of evolution, extinction, and other principles). It’s a depressing and horrifying argument on the face of it, but it’s made so delicately, even poetically—Kolbert’s concerned, occasional first-person narration, and her many interviews with professionals capable of the pithiest, most perfect quotes (not to mention that she interviews these experts, sometimes, over pizza) make this book a conversation, more than a treatise. Kolbert talks us through the headiest, most complicated science, breaking down this mass disaster morsel by morsel. This might be The Sixth Extinction’s greatest achievement—it is so smart while also being so quotidian, so urgent while also being so present. And this fits the tone of her argument: our current mass extinction doesn’t feel like an asteroid hitting the planet. It’s amassed by the small ways in which we live our lives. We are crawling, she illuminates, towards the end of the world. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

It’s a depressing and horrifying argument on the face of it, but it’s made so delicately, even poetically—Kolbert’s concerned, occasional first-person narration, and her many interviews with professionals capable of the pithiest, most perfect quotes (not to mention that she interviews these experts, sometimes, over pizza) make this book a conversation, more than a treatise. Kolbert talks us through the headiest, most complicated science, breaking down this mass disaster morsel by morsel. This might be The Sixth Extinction’s greatest achievement—it is so smart while also being so quotidian, so urgent while also being so present. And this fits the tone of her argument: our current mass extinction doesn’t feel like an asteroid hitting the planet. It’s amassed by the small ways in which we live our lives. We are crawling, she illuminates, towards the end of the world. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me (2015)

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me 1) won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2015, 2) was a #1 New York Times bestseller, and 3) was deemed “required reading” by Toni Morrison. What else is there to say? To call it “timely” or “urgent” or even “a prime example of how the personal is, in fact, political” (as I am tempted to do) does not quite capture the unique, grounding, heartbreaking experience of reading this book. Framed as a letter to his teenage son, Between the World and Me is both a biting interrogation of American history and today’s society and an intimate look at the concerns and hopes a father passes down to his son. In just 152 pages, this book touches on the creation of race (“But race is the child of racism, not the father”), the countless acts of violence enacted on black bodies, gun control, and anecdotes from the writer’s own life. Ta-Nehisi Coates, a correspondent for The Atlantic, exercises a journalist’s concision and clarity and fuses it with the flourish of a novelist and the caring instinct of a father. It is a wonderful hybrid. The way the topics, the tones, bleed into one another reads so naturally: “I write you in your fifteenth year.

What else is there to say? To call it “timely” or “urgent” or even “a prime example of how the personal is, in fact, political” (as I am tempted to do) does not quite capture the unique, grounding, heartbreaking experience of reading this book. Framed as a letter to his teenage son, Between the World and Me is both a biting interrogation of American history and today’s society and an intimate look at the concerns and hopes a father passes down to his son. In just 152 pages, this book touches on the creation of race (“But race is the child of racism, not the father”), the countless acts of violence enacted on black bodies, gun control, and anecdotes from the writer’s own life. Ta-Nehisi Coates, a correspondent for The Atlantic, exercises a journalist’s concision and clarity and fuses it with the flourish of a novelist and the caring instinct of a father. It is a wonderful hybrid. The way the topics, the tones, bleed into one another reads so naturally: “I write you in your fifteenth year. I am writing you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, and that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store…” The list, of course, goes on. Between the World and Me brilliantly forces us to confront these tragedies again—to remember our own experiences watching the news coverage, to see them in the context of history filtered through Ta-Nehisi Coates’ unsurprised perspective, and to see them anew through the eyes of his disillusioned young son. There is an amazing generosity to these personal glimpses, the moments when the writer turns to his son (says “you”). They catch you off guard. (There are even photographs throughout, like a scrapbook you aren’t sure if you’re allowed to look through.) There have been many books about race, about violence and institutionalized injustice and identity, and there will be more, but none quite so beautifully shattering as this.

I am writing you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, and that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store…” The list, of course, goes on. Between the World and Me brilliantly forces us to confront these tragedies again—to remember our own experiences watching the news coverage, to see them in the context of history filtered through Ta-Nehisi Coates’ unsurprised perspective, and to see them anew through the eyes of his disillusioned young son. There is an amazing generosity to these personal glimpses, the moments when the writer turns to his son (says “you”). They catch you off guard. (There are even photographs throughout, like a scrapbook you aren’t sure if you’re allowed to look through.) There have been many books about race, about violence and institutionalized injustice and identity, and there will be more, but none quite so beautifully shattering as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Andrea Wulf, The Invention of Nature (2015)

Andrea Wulf’s 2015 biography of 18th-century German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt—one of the most famous men of his time, for whom literally hundreds of towns, rivers, currents, glaciers, and more are named—is so much more than the story of a single life. Aside from chronicling a remarkably fertile moment in the history of European ideas (Von Humboldt was good buddies with his neighbor in Weimar, Goethe) Wulf reveals in Humboldt a true forebear of present-day ecology, a jack-of-all-trades scientist less concerned with the reduction of the natural world into its constituent specimens than with our place in a broader ecosystem.

And while it doesn’t seem particularly radical now, Humboldt’s proto-environmentalist ideas about the wider world, much of which he mapped and explored, stood in stark contrast to prevailing notions of Christian dominion, that dubious theological position conjured up in aid of empire. Insofar as Humboldt was among the first to understand and articulate the complex systems of a living forest, he was also the first to sound the alarm about the impacts of deforestation (much of which he encountered on his epic journey across the northern reaches of South America). Part adventure yarn, part intellectual history, part ecological meditation, The Invention of Nature restores to prominence an exemplary life, and reminds us of the tectonic force of ideas paired to action. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Insofar as Humboldt was among the first to understand and articulate the complex systems of a living forest, he was also the first to sound the alarm about the impacts of deforestation (much of which he encountered on his epic journey across the northern reaches of South America). Part adventure yarn, part intellectual history, part ecological meditation, The Invention of Nature restores to prominence an exemplary life, and reminds us of the tectonic force of ideas paired to action. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Stacy Schiff, The Witches (2015)

It’s surprising that with a topic as popular and recurring in American culture as the Salem witch trials there have not been more books of this kind. Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the bestselling Cleopatra, Stacy Schiff takes to the Salem witch trials with curiosity and a historian’s magnifying glass, setting out to uncover the mystery that has baffled, awed, and terrified generations since. She pokes at the spectacle that Salem has become in mainstream and artistic depictions—how it has blended with folklore and fiction and has hitherto become a sensationalized event in American history which nonetheless has never been fully understood. Schiff writes that despite the imagination surrounding the Salem witch trials, in reality, there is still a gap in their history of—to be exact—nine months; so the impetus of the book and the intent of Schiff is to penetrate the mass hysteria and panic that ripped through Salem at the time and led to the execution of fourteen women and five men. In her opening chapter, Schiff chillingly sets up the atmosphere of the book and asks key questions that will drive its ensuing narrative: “Who was conspiring against you? Might you be a witch and not know it? Can an innocent person be guilty? Could anyone, wondered a group of men late in the summer, consider themselves safe?” At the heart of Schiff’s historical investigation is the Puritan culture of New England—but part of her masterful synthesis is that she picks apart at each thread of Salem’s culture and evaluates the witch trials from every perspective.

She pokes at the spectacle that Salem has become in mainstream and artistic depictions—how it has blended with folklore and fiction and has hitherto become a sensationalized event in American history which nonetheless has never been fully understood. Schiff writes that despite the imagination surrounding the Salem witch trials, in reality, there is still a gap in their history of—to be exact—nine months; so the impetus of the book and the intent of Schiff is to penetrate the mass hysteria and panic that ripped through Salem at the time and led to the execution of fourteen women and five men. In her opening chapter, Schiff chillingly sets up the atmosphere of the book and asks key questions that will drive its ensuing narrative: “Who was conspiring against you? Might you be a witch and not know it? Can an innocent person be guilty? Could anyone, wondered a group of men late in the summer, consider themselves safe?” At the heart of Schiff’s historical investigation is the Puritan culture of New England—but part of her masterful synthesis is that she picks apart at each thread of Salem’s culture and evaluates the witch trials from every perspective. Praised for her research as well as her prose and narrative capabilities, Schiff’s The Witches has been described by The Times (London) as “An oppressive, forensic, psychological thriller”; Schiff herself, by the New York Review of Books as having “mastered the entire history of early New England.” A phrase that still haunts me for its resonance throughout human history, is: “Even at the time, it was clear to some that Salem was a story of one thing behind which was a story about something else altogether.” –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Praised for her research as well as her prose and narrative capabilities, Schiff’s The Witches has been described by The Times (London) as “An oppressive, forensic, psychological thriller”; Schiff herself, by the New York Review of Books as having “mastered the entire history of early New England.” A phrase that still haunts me for its resonance throughout human history, is: “Even at the time, it was clear to some that Salem was a story of one thing behind which was a story about something else altogether.” –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Svetlana Alexievich, tr. Bela Shayevich, Secondhand Time (2016)

A landmark work of oral history, Svetlana Alexievich’s Second-hand Time chronicles the decline and fall of Soviet communism and the rise of oligarchic capitalism. Through a multitude of interviews conducted between 1991 and 2012 with ordinary citizens—doctors, soldiers, waitresses, Communist party secretaries, and writers—Alexievich’s account is as important to understanding the Soviet world as Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. Second-hand Time first appeared in Russia in 2013 and was translated into English in 2016 by Bella Shayevich. As David Remnick wrote in The New Yorker, “There are many worthwhile books on the post-Soviet period and Putin’s ascent…But the nonfiction volume that has done the most to deepen the emotional understanding of Russia during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union of late is Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history…” It is shockingly intimate, Alexievich’s interviewees sharing their darkest traumas and deepest regrets. In their kitchens, at gravesites, each character tells the story of a nation abandoned by the Kremlin. Like much of Alexievich’s work, it is radical in its composition, challenging with its polyphony of distinctive, human voices the “official history” of a society that presented itself as homogeneous and monolithic—an achievement the Nobel committee recognized when it cited the Belorussian journalist for developing “a new kind of literary genre…a history of the soul.

Second-hand Time first appeared in Russia in 2013 and was translated into English in 2016 by Bella Shayevich. As David Remnick wrote in The New Yorker, “There are many worthwhile books on the post-Soviet period and Putin’s ascent…But the nonfiction volume that has done the most to deepen the emotional understanding of Russia during and after the collapse of the Soviet Union of late is Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history…” It is shockingly intimate, Alexievich’s interviewees sharing their darkest traumas and deepest regrets. In their kitchens, at gravesites, each character tells the story of a nation abandoned by the Kremlin. Like much of Alexievich’s work, it is radical in its composition, challenging with its polyphony of distinctive, human voices the “official history” of a society that presented itself as homogeneous and monolithic—an achievement the Nobel committee recognized when it cited the Belorussian journalist for developing “a new kind of literary genre…a history of the soul. ” Like her more recent The Unwomanly Face of War and Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II, Alexievich’s project is one of the most important accounts being produced today. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

” Like her more recent The Unwomanly Face of War and Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II, Alexievich’s project is one of the most important accounts being produced today. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Jane Mayer, Dark Money (2016)

In addition to being an incredible work of reporting, Jane Mayer’s Dark Money is a historical document of what happened to America as a small group of plutocrats funded the rise of political candidates who espoused policies and beliefs that had been, until then, considered a part of the fringe right wing of the Republican Party. Mayer describes this group as “a small, rarefied group of hugely wealthy, archconservative families that for decades poured money, often with little public disclosure, into influencing how Americans thought and voted.” Mayer’s painstakingly reported work is a monumental achievement; she lays out, in as much detail as could possibly be available, the mechanisms that allowed this group to channel their wealth and power, with the help of federal law, to a set of institutions that aim to fight scientific advancement, justice-oriented movements, and climate change. In doing so, they have overhauled American politics. As Alan Ehrenhalt put it in a review of the book for The New York Times, she describes “a private political bank capable of bestowing unlimited amounts of money on favored candidates, and doing it with virtually no disclosure of its source.”

In doing so, they have overhauled American politics. As Alan Ehrenhalt put it in a review of the book for The New York Times, she describes “a private political bank capable of bestowing unlimited amounts of money on favored candidates, and doing it with virtually no disclosure of its source.”

The stakes here extend beyond American politics; Mayer points out that Koch money upholds some of the institutions most vigorously fighting climate activism and defending the fossil fuel industry. In 2017, she told the Los Angeles Times, “There are many things you can fix and you can bring back, and there are sort of cycles in American history and the pendulum swings back and forth, but there are things you can damage irreparably, and that’s what I’m worried about right this moment … And that’s why this particular book—because it’s about the money that is stopping this country from doing something useful on climate change.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

David France, How to Survive a Plague (2016)

To call How to Survive a Plague extensive would be an understatement; France’s account of the epidemic’s earliest days is overwhelmingly generous, letting the reader experience those days, and everything that followed, from within the community that faced it first. France recounts the ways in which scientists and doctors first responded to the virus, tracing the evolution of that understanding from within a small circle to a broad cry for awareness and resources; meanwhile, he shows how a community of people fighting for their lives mobilized alternative systems of communication, education, and support while facing an almost inconceivable wall of barriers to that work. The importance of language in this fight is at the forefront here, from the scientific question of what to call the virus, to its reputation in popular culture as “gay cancer,” to the disagreements within activist groups about how to tell their stories to an unsympathetic world.

France recounts the ways in which scientists and doctors first responded to the virus, tracing the evolution of that understanding from within a small circle to a broad cry for awareness and resources; meanwhile, he shows how a community of people fighting for their lives mobilized alternative systems of communication, education, and support while facing an almost inconceivable wall of barriers to that work. The importance of language in this fight is at the forefront here, from the scientific question of what to call the virus, to its reputation in popular culture as “gay cancer,” to the disagreements within activist groups about how to tell their stories to an unsympathetic world.

This is an enraging history, one of various institutional failures, missed opportunities, hypocrisies, and acts of malice toward a community in crisis, motivated by hatred and horror of queer people and gay men in particular. But I felt equally enraged and in awe. This is a humbling history to read, especially if, like me, you come from a generation of queer people that has been accused of forgetting it. I’m grateful for France’s testimony; it won’t let any of us forget. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

I’m grateful for France’s testimony; it won’t let any of us forget. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery (2016)

Reséndez’s The Other Slavery is nothing short of an epic recalibration of American history, one that’s long overdue and badly needed in the present moment. The story of the assault on indigenous peoples in the Americas is perhaps well-known, but what’s less known is how many of those people were enslaved by colonizers, how that enslavement led to mass death, and how complicit the American legal system was in bringing that oppression about and sustaining it for years beyond the supposed emancipation in regions in which indigenous peoples were enslaved. This was not an isolated phenomenon. It extended from Caribbean plantations to Western mining interests. It was part and parcel of the European effort to settle the “new world” and was one of the driving motivations behind the earliest expeditions and colonies. Reséndez puts the number of indigenous enslaved between Columbus’s arrival and 1900 at somewhere between 2.5 and 5 million people. The institution took many forms, but reading through the legal obfuscation and drilling down into the archival record and first-hand accounts of the eras, Reséndez shows how slavery permeated the continents. Native tribes were not simply wiped out by disease, war, and brutal segregation. They were also worked—against their will, without pay, in mass numbers—to death. It was a sustained and organized enslavement. The Other Slavery also tells the story of uprising—communities that resisted, individuals who fought. It’s a complex and tragic story that required a skilled historian to bring into the contemporary consciousness. In addition to his skills as a historian and an investigator, Resendez is a skilled storyteller with a truly remarkable subject. This is historical nonfiction at its most important and most necessary. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Reséndez puts the number of indigenous enslaved between Columbus’s arrival and 1900 at somewhere between 2.5 and 5 million people. The institution took many forms, but reading through the legal obfuscation and drilling down into the archival record and first-hand accounts of the eras, Reséndez shows how slavery permeated the continents. Native tribes were not simply wiped out by disease, war, and brutal segregation. They were also worked—against their will, without pay, in mass numbers—to death. It was a sustained and organized enslavement. The Other Slavery also tells the story of uprising—communities that resisted, individuals who fought. It’s a complex and tragic story that required a skilled historian to bring into the contemporary consciousness. In addition to his skills as a historian and an investigator, Resendez is a skilled storyteller with a truly remarkable subject. This is historical nonfiction at its most important and most necessary. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies (2016)

One night, facing a brief gap between plans with different people, I took Rebecca Traister’s All the Single Ladies to a bar. A few minutes after I ordered, deep in Traister’s incredible, extensive history of single women in America, a server came over to offer me another, more isolated seat at the end of the bar, “so you don’t feel embarrassed about being alone,” she said, quietly. I assured her I was okay, trying not to laugh. She was just so worried.

A few minutes after I ordered, deep in Traister’s incredible, extensive history of single women in America, a server came over to offer me another, more isolated seat at the end of the bar, “so you don’t feel embarrassed about being alone,” she said, quietly. I assured her I was okay, trying not to laugh. She was just so worried.

I turned back to my book to find Traister describing this kind of cultural distress—a woman, alone, in public?!—at a new generation of unmarried adult women, who are more autonomous and numerous today than ever before. Far from marking a crisis in the social order, Traister writes, this shift “was in fact a new order … women’s paths were increasingly marked with options, off-ramps, variations on what had historically been a very constrained theme.” She examines the history of unmarried women as a social and political force, including the activists who devoted their lives to establishing a greater range of educational, familial, and economic choices for women, with particular attention to the ways in which that history is also one of racial and economic justice in the US. Traister also highlights the networks of social support that women have created in order to survive patriarchy and establish lifestyles that did not depend on it; intimacy and communication among unmarried women, she shows, were the backbone of activist and reform movements that successfully challenged the dominant order.

Traister also highlights the networks of social support that women have created in order to survive patriarchy and establish lifestyles that did not depend on it; intimacy and communication among unmarried women, she shows, were the backbone of activist and reform movements that successfully challenged the dominant order.

The book draws on interviews from dozens of women of varying backgrounds, and their firsthand accounts are a portrait of life amid a historic shift toward female autonomy. Their stories, and Traister’s analysis, make it clear that even as options for many women are expanding, those options are not equally available or beneficial to all women. This is a stunning reckoning with the state of women’s independence and the policies that still seek to curtail it. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Caroline Fraser, Prairie Fires (2017)

Prairie Fires, Caroline Fraser’s Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Critics Circle Award-winning biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder is not just a painstakingly researched and lyrically realized account of how the Little House on the Prairie author decanted the poverty and precarity of her homesteader family’s existence into narratives of self-reliance and perseverance—although it is that—it is also a meditation on the human need “to transform the raw materials of the past into art. ” Full disclosure, I did not read the Little House on the Prairie books as a child and have no sentimental attachment to Laura, Pa or Ma. But in looking at the life behind the books, Wilder emerges as a tenacious, sometimes fragile figure, and as a literary operator of uncommon nous and self-awareness. Drawing on unpublished manuscripts, letters, diaries, and land and financial records, Prairie Fires has all the essentials of a great history book. Most importantly, Fraser’s great skill is in pulling back the veils of mythology that have enshrouded her subject and the era her works helped to define, enabling us to see both the real people and the myths themselves with fresh, critical eyes. There is no romanticizing of the Frontier, and a very real understanding of the sentimentality and bias of an overtly racist understanding of “westward expansion.” It is a remarkable book. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

” Full disclosure, I did not read the Little House on the Prairie books as a child and have no sentimental attachment to Laura, Pa or Ma. But in looking at the life behind the books, Wilder emerges as a tenacious, sometimes fragile figure, and as a literary operator of uncommon nous and self-awareness. Drawing on unpublished manuscripts, letters, diaries, and land and financial records, Prairie Fires has all the essentials of a great history book. Most importantly, Fraser’s great skill is in pulling back the veils of mythology that have enshrouded her subject and the era her works helped to define, enabling us to see both the real people and the myths themselves with fresh, critical eyes. There is no romanticizing of the Frontier, and a very real understanding of the sentimentality and bias of an overtly racist understanding of “westward expansion.” It is a remarkable book. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018)

In 2017, monuments commemorating heroes of the Confederacy were being debated, defaced and toppled throughout the United States. That same year, months before President Trump signed a law creating a commission to plan for the bicentennial of Frederick Douglass’ birth, he infamously seemed to suggest that Douglass was still around, doing an “amazing job” and “getting recognized more and more.” The irony was hard to miss: it was easy to eulogize a past that was not comprehensively, nor even fundamentally understood. One achievement of historian David Blight’s monumental study of the former slave turned abolitionist is the thoroughness with which it examines the man’s development across three autobiographies he produced in the span of ten years. The popular image of Douglass has long been that of a bushy-haired man affixed to Abraham Lincoln’s side, delivering rousing speeches on abolition and the sins of slavery. And while there is basic truth to that, Blight sets out to fill the gaps in public understanding, guiding readers from the Maryland slave plantation where Douglass was born to the many stops along his European speech circuit, when he established himself as one of the world’s most recognizable opponents of slavery.

That same year, months before President Trump signed a law creating a commission to plan for the bicentennial of Frederick Douglass’ birth, he infamously seemed to suggest that Douglass was still around, doing an “amazing job” and “getting recognized more and more.” The irony was hard to miss: it was easy to eulogize a past that was not comprehensively, nor even fundamentally understood. One achievement of historian David Blight’s monumental study of the former slave turned abolitionist is the thoroughness with which it examines the man’s development across three autobiographies he produced in the span of ten years. The popular image of Douglass has long been that of a bushy-haired man affixed to Abraham Lincoln’s side, delivering rousing speeches on abolition and the sins of slavery. And while there is basic truth to that, Blight sets out to fill the gaps in public understanding, guiding readers from the Maryland slave plantation where Douglass was born to the many stops along his European speech circuit, when he established himself as one of the world’s most recognizable opponents of slavery. The vague circumstances of Douglass’ birth (he was born to an enslaved woman and a white man who may also have been his owner) later compelled him to create his own life narratives, a task that he accomplished both in writing and oratory. Blight’s engagement with Douglass’ writing also marks the biography as a triumph of public-facing textual criticism. For decades before Prophet of Freedom astonished critics and general readers, Blight had been making his name as one of the leading Douglass scholars in the US. Blight’s work was not historical revisionism, but rather a considered analysis of a man who relied on actions as much as words. Many may be surprised to learn, for example, what a vocal supporter Douglass was of the Civil War and violence as a necessary means to dismantle the system that had nearly destroyed him. Prophet of Freedom feels as definitive as a Robert Fagles translation of Homer—we hope it’s not the final word, though it will take quite the successor to produce a worthwhile follow-up.

The vague circumstances of Douglass’ birth (he was born to an enslaved woman and a white man who may also have been his owner) later compelled him to create his own life narratives, a task that he accomplished both in writing and oratory. Blight’s engagement with Douglass’ writing also marks the biography as a triumph of public-facing textual criticism. For decades before Prophet of Freedom astonished critics and general readers, Blight had been making his name as one of the leading Douglass scholars in the US. Blight’s work was not historical revisionism, but rather a considered analysis of a man who relied on actions as much as words. Many may be surprised to learn, for example, what a vocal supporter Douglass was of the Civil War and violence as a necessary means to dismantle the system that had nearly destroyed him. Prophet of Freedom feels as definitive as a Robert Fagles translation of Homer—we hope it’s not the final word, though it will take quite the successor to produce a worthwhile follow-up. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

–Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Robert Macfarlane, Underland (2019)

One hesitates to label any book by a living writer his “magnum opus” but Macfarlane’s Underland—a deeply ambitious work that somehow exceeds the boundaries it sets for itself—reads as offertory and elegy both, finding wonder in the world even as we mourn its destruction by our own hand. If you’re unfamiliar with its project, as the name would suggest, Underland is an exploration of the world beneath our feet, from the legendary catacombs of Paris to the ancient caveways of Somerset, from the hyperborean coasts of far Norway to the mephitic karst of the Slovenian-Italian borderlands.

Macfarlane has always been a generous guide in his wanderings, the glint of his erudition softened as if through the welcoming haze of a fireside yarn down the pub. Even as he considers all we have wrought upon the earth, squeezing himself into the darker chambers of human creation—our mass graves, our toxic tombs—Macfarlane never succumbs to pessimism, finding instead in the contemplation of deep time a path to humility. This is an epochal work, as deep and resonant as its subject matter, and would represent for any writer the achievement of a lifetime. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

This is an epochal work, as deep and resonant as its subject matter, and would represent for any writer the achievement of a lifetime. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing: A True History of Memory and Murder in Northern Ireland (2019)