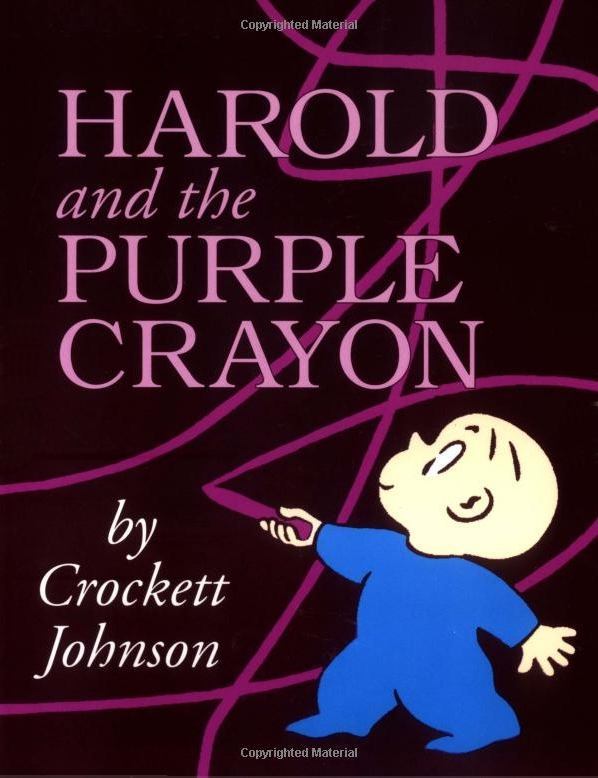

Harry and the purple crayon

Harold and the Purple Crayon - Teaching Children Philosophy

by Crockett Johnson

FILTERS: mind, reality, grade-1-2, prek-k

Book Module Navigation

Summary »

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion »

Questions for Philosophical Discussion »

Summary

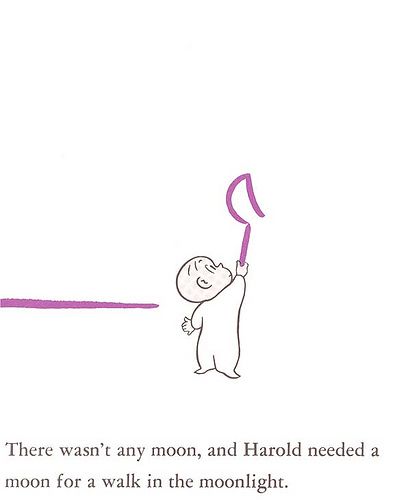

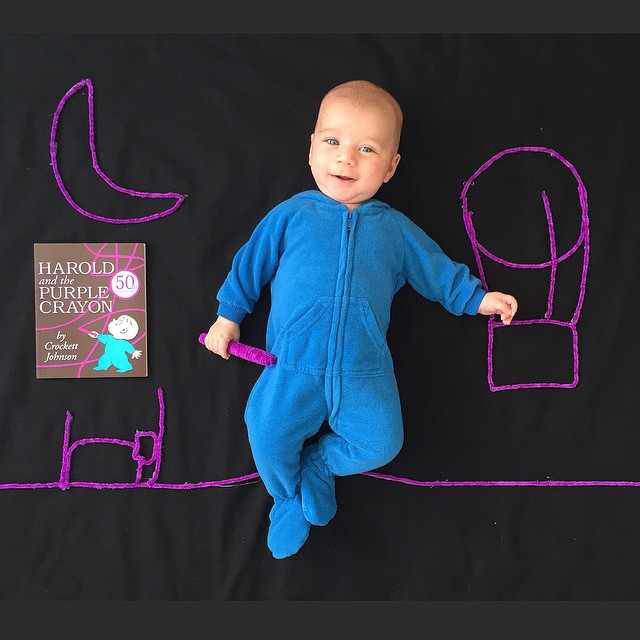

Harold and the Purple Crayon examines a number of difficult questions about the nature of reality.Harold thinks it over for some time and decides to go for a walk in the moonlight. This may seem unremarkable, but it is not. There is no moon. There is nothing to walk on. There is nowhere to go. The only things that are real are Harold and the purple crayon.

Read aloud video by Harper Kids

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The overarching theme of Harold and the Purple Crayon is deciphering reality. As a rather ambiguous idea, the discussion of “reality” will throw the children into a fun and active topsy-turvy discussion of what it means to be real, and how one gives objects the power of reality. In a world represented by a blank page, Harold is free to draw his surroundings with his big purple crayon. Is Harold playing make-believe? Is that different from what is real? The questions in this set revolve around the children’s perception of reality. Harold interacts with his drawings in a very “real” way.

The first question in this set addresses a secondary character that follows Harold throughout the story: the moon. The idea of the moon as a constant in the night sky is one children tend to agree with. What complicates this situation, however, is the fact that when the moon is absent in Harold’s world, he draws it with his purple crayon above him in the “sky”. This is left the children to question the validity or reality of Harold’s world. If Harold can draw a moon in the sky, it seems that he could not possibly be existing in the “real” world. And furthermore, he must simply be pretending because, as the children may point out, no one could draw a “real” moon in the sky. Or could they? What makes the moon we observe any more “real” than Harold’s moon? This line of questioning leads the children to discuss the relationship between perception and reality. Must things be experiential in order to be real? Or can they exist simply in our minds? In philosophical study, this may seem similar to the debate of the empiricists versus the rationalists. Rationalists like Descartes tended to believe that the reality of objects was in our ability to rationally understand them. At the same time, empiricists like Locke felt that the interaction with objects in a physical way gave them a sense of universal reality. Obviously, the children will not be familiar with this philosophical distinction, but through the debate and discussion over the reality of Harold’s objects, they can come to know the issues involved.

Or could they? What makes the moon we observe any more “real” than Harold’s moon? This line of questioning leads the children to discuss the relationship between perception and reality. Must things be experiential in order to be real? Or can they exist simply in our minds? In philosophical study, this may seem similar to the debate of the empiricists versus the rationalists. Rationalists like Descartes tended to believe that the reality of objects was in our ability to rationally understand them. At the same time, empiricists like Locke felt that the interaction with objects in a physical way gave them a sense of universal reality. Obviously, the children will not be familiar with this philosophical distinction, but through the debate and discussion over the reality of Harold’s objects, they can come to know the issues involved.

The second and third question sets revolve around Harold’s experience. As the questions in the second set indicate, Harold seems to be in danger during part of the story; he may even be afraid of the objects he draws. For some of the students, this may indicate a level of reality that is not at first apparent. To have feelings, either sensory or emotional, about an object indicates that the object holds some form of power over its observer. This power is translated to designate a level of “reality” as compared to the surrounding world. Then the task is outlining the differences or definitions that make something real. These qualities in Harold’s drawings further blur the line between what is presumably the “real” world outside of the story. When Harold falls from the hill that he climbs, and when he stumbles into the ocean, he has drawn, it seems as though his life is seriously in danger. This fear is a form of power Harold has passively given to his drawings.

For some of the students, this may indicate a level of reality that is not at first apparent. To have feelings, either sensory or emotional, about an object indicates that the object holds some form of power over its observer. This power is translated to designate a level of “reality” as compared to the surrounding world. Then the task is outlining the differences or definitions that make something real. These qualities in Harold’s drawings further blur the line between what is presumably the “real” world outside of the story. When Harold falls from the hill that he climbs, and when he stumbles into the ocean, he has drawn, it seems as though his life is seriously in danger. This fear is a form of power Harold has passively given to his drawings.

On the other hand, one may question if that gives the ocean or the rock the physical reality to harm Harold. Physical reality and the scientific properties therein sometimes indicate a kind of absolute reality that is independent of Harold. The children can then begin to explore the idea how we know whether objects continue to exist when no one is there to observe them. The physical properties, such as atoms and molecules seem to give objects a sense of absolute reality. However, the majority of people will never see a tree at a purely molecular level; they will see a tree as brown bark and green leaves, using subjective measurements that exist within each individual. The students will then be able to draw their own connections about whether believing in something or fearing it gives it reality for the observer and consequently an absolute reality independent of the observer.

The children can then begin to explore the idea how we know whether objects continue to exist when no one is there to observe them. The physical properties, such as atoms and molecules seem to give objects a sense of absolute reality. However, the majority of people will never see a tree at a purely molecular level; they will see a tree as brown bark and green leaves, using subjective measurements that exist within each individual. The students will then be able to draw their own connections about whether believing in something or fearing it gives it reality for the observer and consequently an absolute reality independent of the observer.

In the third question set, the conclusions from the second set can be reevaluated. Although the emotions or physical danger that Harold may experience as “real”, where do they exist? In this stage, the children can begin to question the idea that Harold could be dreaming this entire purple-crayon-created world. If Harold is dreaming all of this, it seems easier to swallow: we as an audience can attribute these “fantasies” to something we know and also experience. However, the next step in the debate is a discussion of the reality of dreams. Are dreams “real” in the way we have previously defined the term (see question set 1)? The students may then choose to reevaluate their definition of “real”.

However, the next step in the debate is a discussion of the reality of dreams. Are dreams “real” in the way we have previously defined the term (see question set 1)? The students may then choose to reevaluate their definition of “real”.

In the fourth question set, we begin to discuss the idea of Harold as a character in these drawings. If these are Harold’s drawings and they belong to him, could accidents happen within them? In this way the students will continue to discuss and stretch the reality of Harold’s world. The role of ownership is undefined in the story and in the lives of the children themselves. Do people have control over the events that occur in their lives, are they purely accidental, or can they be attributed to another force? The students can describe Harold’s accidents and relate them to their own in a connection that will help them to understand the concept universally.

The fifth question set explores how Harold also is subject to being lost in his own drawing, lost in the world he created. He travels on a long and perilous journey to find his bedroom window, and when he finally does, the audience is left to wonder whether he even needed to walk through the cities of windows to find his own at all. If this crayon gives Harold the power to create his bedroom anywhere, then it is strange that he is so intent on searching for his “real” window. Being so submerged in his own creations might give Harold an ultimate sense of power and reality, but at this point of the story, as Harold frantically searches for his window, he fears that he cannot escape the world he has created. This leads the students to question the world “outside” of Harold’s world. They can compare themselves with Harold and thus apply his story to their own existence.

He travels on a long and perilous journey to find his bedroom window, and when he finally does, the audience is left to wonder whether he even needed to walk through the cities of windows to find his own at all. If this crayon gives Harold the power to create his bedroom anywhere, then it is strange that he is so intent on searching for his “real” window. Being so submerged in his own creations might give Harold an ultimate sense of power and reality, but at this point of the story, as Harold frantically searches for his window, he fears that he cannot escape the world he has created. This leads the students to question the world “outside” of Harold’s world. They can compare themselves with Harold and thus apply his story to their own existence.

The final question set asks the children to address an event common to their own lives and understand the role of reality in it. All the children are likely to relate to Harold’s nine-pie picnic, in that they have enjoyed pretending to have a picnic with pretend food. However, in the illustration and description of the book, it is obvious that Harold is drawing the pies in one moment and then has supposedly eaten them in another. This picnic is reminiscent of a make-believe tea party that you throw for you and your stuffed animals to enjoy. In this case, it is a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine that interacts with Harold. For the children who may have previously defined Harold as un-realistic, this is an example intended to make them define their positions. What is going on in this story? Is it make-believe, a dream, reality, or something else? Encouraging the students to back up their beliefs with reasons and evidence will help them to formulate and understand this debate-style dialogue.

However, in the illustration and description of the book, it is obvious that Harold is drawing the pies in one moment and then has supposedly eaten them in another. This picnic is reminiscent of a make-believe tea party that you throw for you and your stuffed animals to enjoy. In this case, it is a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine that interacts with Harold. For the children who may have previously defined Harold as un-realistic, this is an example intended to make them define their positions. What is going on in this story? Is it make-believe, a dream, reality, or something else? Encouraging the students to back up their beliefs with reasons and evidence will help them to formulate and understand this debate-style dialogue.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him. We know that Harold wants to go on a journey under the moonlight, but when he does not see the moon shining, he uses his purple crayon to draw a moon in the sky.

- Is the moon that Harold draws the same as the moon we can see in the sky at night?

- Which moon is the “real” moon?

- What makes it “real”?

When Harold falls into the “ocean” that he draws, do you think his life is in danger? Do you think he could drown?

- Do you think Harold is afraid of the ocean?

- Does his fear make the drawing more “real”?

- Do emotions and beliefs make things real?

The boat seems to save Harold from drowning. Do you think that what is happening to Harold is real?

- Are the things happening to Harold in his mind or somewhere else?

- Could it be that everything happening to Harold is a dream?

- Are dreams real?

When Harold steps over the edge of the mountain, he begins to fall through the air. Do you think that it was an accident?

- Did Harold know that was going to happen to him?

- Can there be accidents in Harold’s world even if he’s drawing them?

- Can you make an accident happen?

If Harold is drawing his own world, why does it take him so long to find his window?

- Do you think Harold could get lost in the world he is drawing?

- Could he be imagining that he is lost?

- What does it mean to be lost?

Harold draws himself a picnic with nine different pies.

- Have you ever had an imaginary tea party or an imaginary picnic?

- Is that what Harold is doing in the story? Is he playing make-believe?

- Or could the events “really” be happening to him?

- What’s the difference between “make-believe” and “real”?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Claire Bartholome. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.

Download & PrintEmail Book Module View en Español Back to All Books

Harold and the Purple Crayon

None Harold’s creativity and imagination know no bounds in this timeless classic. Harold wanted to go on a walk but didn’t have a path to walk on or a moon to light his way. With his purple crayon in hand, he drew himself a path and a moon that followed him. And so began his journey through his own imagination. Walking along the path, he decided that he needed a forest, so he drew a tree—he didn’t want to get lost! One idea growing from another, Harold’s story kept on until he made it into his bed and, exhausted from his adventure, fell fast asleep with his purple crayon next to him. What imaginative adventure will you draw with your crayon? show full description Show Short Description

And so began his journey through his own imagination. Walking along the path, he decided that he needed a forest, so he drew a tree—he didn’t want to get lost! One idea growing from another, Harold’s story kept on until he made it into his bed and, exhausted from his adventure, fell fast asleep with his purple crayon next to him. What imaginative adventure will you draw with your crayon? show full description Show Short Description Classics

Share your favorite stories with your child. Enjoy classic bedtime stories from your childhood like Chicka Chicka Boom Boom, Chicken Little, Where the Wild Things Are, and Harold and the Purple Crayon.

view all

Chicka Chicka Boom Boom

Harry the Dirty Dog

Wheels on the Bus

Chicken Little

The Snowy Day

The Dot

Where the Wild Things Are

Duck on a Bike

Swimmy

Harold and the Purple Crayon

One membership, two learning apps for ages 2-8.

TRY IT FOR FREE

Full Text

One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight. There wasn’t any moon, and Harold needed a moon for a walk in the moonlight. And he needed something to walk on. He made a long straight path so he wouldn’t get lost. And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him. But he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere on the long straight path. So he left the path for a shortcut across a field. And the moon went with him. The shortcut led right to where Harold thought a forest ought to be. He didn’t want to get lost in the woods, so he made a very small forest with just one tree in it. It turned out to be an apple tree. The apples would be very tasty, Harold thought, when they got red. So he put a frightening dragon under the tree to guard the apples. It was a terribly frightening dragon. It even frightened Harold. He backed away. His hand, holding the purple crayon, shook. Suddenly, he realized what was happening. But by then, Harold was over his head in an ocean. He came up thinking fast. And in no time, he was climbing aboard a trim little boat. He quickly set sail. And the moon sailed along with him. After he had sailed long enough, Harold made land without much trouble. He stepped ashore on the beach, wondering where he was. The sandy beach reminded Harold of picnics. And the thought of picnics make him hungry. So he laid out a nice simple picnic lunch. There was nothing but pie. But there were all nine kinds of pie that Harold liked best. When Harold finished his picnic, there was quite a lot left over. He hated to see so much delicious pie go to waste, so Harold left a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine to finish it up. And, off he went, looking for a hill to climb to see where he was. Harold knew that the higher up he went, the farther he could see. So he decided to make the hill into a mountain. If he went high enough, he thought, he could see the window of his bedroom.

Suddenly, he realized what was happening. But by then, Harold was over his head in an ocean. He came up thinking fast. And in no time, he was climbing aboard a trim little boat. He quickly set sail. And the moon sailed along with him. After he had sailed long enough, Harold made land without much trouble. He stepped ashore on the beach, wondering where he was. The sandy beach reminded Harold of picnics. And the thought of picnics make him hungry. So he laid out a nice simple picnic lunch. There was nothing but pie. But there were all nine kinds of pie that Harold liked best. When Harold finished his picnic, there was quite a lot left over. He hated to see so much delicious pie go to waste, so Harold left a hungry moose and a deserving porcupine to finish it up. And, off he went, looking for a hill to climb to see where he was. Harold knew that the higher up he went, the farther he could see. So he decided to make the hill into a mountain. If he went high enough, he thought, he could see the window of his bedroom. He was tired, and he felt he ought to be getting to bed. He hoped he could see his bedroom window from the top of the mountain. But as he looked down over the other side he slipped— and there wasn’t any other side of the mountain. He was falling in thin air. But luckily he kept his wits and his purple crayon. He made a balloon, and he grabbed onto it. And he made a basket under the balloon big enough to stand in. He had a fine view from the balloon, but he couldn’t see his window. He couldn’t even see a house. So he made a house with windows. And he landed the balloon on the grass in the front yard. None of the windows was his window. He tried to think where his window ought to be. He made some more windows. He made a big building full of windows. He made lots of buildings full of windows. He made a whole city full of windows. But none of the windows was his window. He couldn’t think where it might be. He decided to ask a policeman. The policeman pointed the way Harold was going anyway, but Harold thanked him.

He was tired, and he felt he ought to be getting to bed. He hoped he could see his bedroom window from the top of the mountain. But as he looked down over the other side he slipped— and there wasn’t any other side of the mountain. He was falling in thin air. But luckily he kept his wits and his purple crayon. He made a balloon, and he grabbed onto it. And he made a basket under the balloon big enough to stand in. He had a fine view from the balloon, but he couldn’t see his window. He couldn’t even see a house. So he made a house with windows. And he landed the balloon on the grass in the front yard. None of the windows was his window. He tried to think where his window ought to be. He made some more windows. He made a big building full of windows. He made lots of buildings full of windows. He made a whole city full of windows. But none of the windows was his window. He couldn’t think where it might be. He decided to ask a policeman. The policeman pointed the way Harold was going anyway, but Harold thanked him. And he walked along with the moon, wishing he was in his room and in bed. Then, suddenly, Harold remembered. He remembered where his bedroom window was when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon. And then Harold made his bed, got in it, and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.

And he walked along with the moon, wishing he was in his room and in bed. Then, suddenly, Harold remembered. He remembered where his bedroom window was when there was a moon. It was always right around the moon. And then Harold made his bed, got in it, and he drew up the covers. The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.

1

We take your child's unique passions

2

Add their current reading level

3

And create a personalized learn-to-read plan

4

That teaches them to read and love reading

TRY IT FOR FREE

Pencil skirt. History | Vogue Russia

The history of the pencil skirt began with an anecdotal incident. In 1908, American Mrs. Edith Hart O. Burt became the first woman passenger in an airplane, a marvel of engineering invented by the Wright brothers. To prevent the fluffy skirt typical of that time from fluttering during the flight and not getting stuck in the mechanisms, O. Burt tied it below the knees with twine. According to legend, such a silhouette inspired fashion designers, in particular Paul Poiret, to create the so-called hobble skirt - a narrow skirt with a slightly flared hem. Be that as it may, this style, which forced women to move with quick short steps, soon became a mass fashion and, moreover, became an object of ridicule. Newspapers and magazines published satirical illustrations that ridiculed women's desire to look beautiful despite comfort. On the streets of New York and Los Angeles, there were even special carriages designed for women in tight skirts. Unfortunately or fortunately, the century of this trend turned out to be short-lived: already in the 19In the 1920s, it was replaced by shorter dresses and straight, loose-fitting skirts.

Burt tied it below the knees with twine. According to legend, such a silhouette inspired fashion designers, in particular Paul Poiret, to create the so-called hobble skirt - a narrow skirt with a slightly flared hem. Be that as it may, this style, which forced women to move with quick short steps, soon became a mass fashion and, moreover, became an object of ridicule. Newspapers and magazines published satirical illustrations that ridiculed women's desire to look beautiful despite comfort. On the streets of New York and Los Angeles, there were even special carriages designed for women in tight skirts. Unfortunately or fortunately, the century of this trend turned out to be short-lived: already in the 19In the 1920s, it was replaced by shorter dresses and straight, loose-fitting skirts.

Vogue US, 1960

The pencil skirt as we know it today came much later, in 1954, when Christian Dior presented his H-line collection. In terms of cut, they resembled the outlines of the Latin letter H - straight lines, emphasized waist - and looked favorably on the figure, as they visually lengthened the legs and shifted the focus to the hips. In addition, this collection has become an alternative to the new look silhouette, which has had time to get bored, with its immense skirts and meters of fabric. Of course, Dior was not a pioneer. Back at 19In the 1940s, skirt cuts began to become tighter and more boxy - an example of this can be seen in the movie To Have or Not to Have, starring Lauren Bacall. It is worth paying tribute to other authoritative couturiers of that era, for example, Cristobal Balenciaga, who, with his clothes, sought to emphasize the natural lines of the female body, and not distort them with overlays and crinolines.

In addition, this collection has become an alternative to the new look silhouette, which has had time to get bored, with its immense skirts and meters of fabric. Of course, Dior was not a pioneer. Back at 19In the 1940s, skirt cuts began to become tighter and more boxy - an example of this can be seen in the movie To Have or Not to Have, starring Lauren Bacall. It is worth paying tribute to other authoritative couturiers of that era, for example, Cristobal Balenciaga, who, with his clothes, sought to emphasize the natural lines of the female body, and not distort them with overlays and crinolines.

Popular

Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not, 1944

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the pencil skirt became the defining piece of clothing. A woman in such a skirt could be an elegant intellectual, like Grace Kelly in Rear Window. Or a sexy seductress like Sophia Loren, who wore them with striped tops and fitted jackets. Audrey Hepburn's little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany's is another variation of the pencil skirt. And Marilyn Monroe, whose image is largely associated with this garment, brought it to the status of a cult: thanks to her, the pencil skirt became a symbol of absolute femininity, and the hourglass figure became the standard of beauty. Like hobble skirt 1910s, such an outfit required a certain gait, which can be seen performed by Monroe in the films Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Only Girls in Jazz.

Audrey Hepburn's little black dress in Breakfast at Tiffany's is another variation of the pencil skirt. And Marilyn Monroe, whose image is largely associated with this garment, brought it to the status of a cult: thanks to her, the pencil skirt became a symbol of absolute femininity, and the hourglass figure became the standard of beauty. Like hobble skirt 1910s, such an outfit required a certain gait, which can be seen performed by Monroe in the films Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Only Girls in Jazz.

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in the film “Window to the Dvor”, 1954

Popular

Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe in the film “Gentlets prefer blondes”, 1953

to a word, that word. the fact that the pencil skirt literally changes the walk of its wearer made it a symbol of sex appeal (Stockard Channing's heroine in Grease), and later a hallmark of strong women (such as Joan Collins in Dynasty). The culmination of the erotic overtones is an addiction to tight skirts, especially those made of leather or latex, representatives of the fetish culture. Dita Von Teese comes to mind first, of course. The pencil skirt can also be considered a harbinger of super-tight sheath dresses, which experienced their boom in the 2000s and are now back at the peak of relevance, thanks to the Kardashian clan.

Dita Von Teese comes to mind first, of course. The pencil skirt can also be considered a harbinger of super-tight sheath dresses, which experienced their boom in the 2000s and are now back at the peak of relevance, thanks to the Kardashian clan.

Popular

Prince Harry and Megan Markle in Boss and & Other Stories in London, October 2018

and 1960s in the pencil skirts were conceived as an exclusively practical clothing item. They served as an everyday uniform for working women, especially if they were complemented by a small slit at the back. And they are still a mandatory part of the office dress code in many corporate organizations. It is hard to imagine the wardrobe of first ladies like Michelle Obama and Meghan Markle without such a skirt. Today, a pencil skirt does not necessarily convey sexuality: its more calm, basic variations can be found, for example, at Victoria Beckham and Rejina Pyo.

Victoria Beckham, Art School, Rejina Pyo Autumn-Winter 2019

Popular

Sensual or strict, perfectly crushed or with rawed edges, which refers to the 1950s. to be like your moms, or to drag culture - although the pencil skirt is considered a classic wardrobe item, its history and visual diversity is much richer than it seems at first glance. And, judging by the collections of autumn-winter 2019, in the near future, designers are not going to ignore this piece of clothing.

to be like your moms, or to drag culture - although the pencil skirt is considered a classic wardrobe item, its history and visual diversity is much richer than it seems at first glance. And, judging by the collections of autumn-winter 2019, in the near future, designers are not going to ignore this piece of clothing.

Vogue US, 1985

Sign up and be one step closer to fashion professionals.

Photo: Arthur Elgort

Meghan Markle's makeup secrets that won over Prince Harry

Meghan Markle has long been considered the standard of modern fashion. Each outfit or accessory that appeared on the Duchess is sold out in a matter of hours. The same excitement is caused by the makeup of the Sussex. Megan carefully monitors her physical condition and follows the regime, because healthy skin is beautiful skin, on which a light tone, bronzer or highlighter will look natural and gentle. After Meghan became part of the royal family, she preferred naturalness for herself, abandoning bright makeup, which made her even more attractive.

After Meghan became part of the royal family, she preferred naturalness for herself, abandoning bright makeup, which made her even more attractive.

Sussex recently wowed the audience at the Salute To Freedom gala at the Intrepid Museum of Sea, Air and Space with her new look. The Duchess appeared in a bright red dress with a plunging neckline and a thigh-high slit from Carolina Herrera, which was designed by Wes Gordon. Many were surprised by Megan's audacity, but fans liked the Duchess's femininity. Sussex complemented her image with a smooth high beam, but in makeup she decided to experiment a little. The image for the celebration was helped by the same specialists who prepared Megan for her wedding.

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle at the 2021 Salute To Freedom Gala

The Duchess' makeup artist shared that he was inspired by Audrey Hepburn for Sussex's eye make-up. Hairstylist Serge Norman worked alongside makeup artist Daniel Martin to achieve red carpet perfection. “ It was a lot of fun to get us all together again. It was cool and calm, like the old gang got back together. Harry joked a lot and Meghan is very funny. We laughed heartily ,” Martin said. Daniel Martin's idea for " Wing Arrows " was a hit with the Duchess.

“ It was a lot of fun to get us all together again. It was cool and calm, like the old gang got back together. Harry joked a lot and Meghan is very funny. We laughed heartily ,” Martin said. Daniel Martin's idea for " Wing Arrows " was a hit with the Duchess.

Meghan Markle at the 2021 Salute To Freedom Gala

« Creating this symmetry with eyeliner was something to try. I wanted the Audrey Hepburn-inspired eyes to not be too bright, so we used purple instead of black. I just love the combination of red and purple ,” Martin shared. It turned out that Harry really liked this makeup: “ He thought it was cool ,” the makeup artist said. Megan has a very dramatic look, so this make-up technique absolutely suits her.

Meghan Markle at the Salute To Freedom Gala 2021

Daniel used products from completely different brands to stun the audience with a bright and shiny look. “What thrilled me was that I was able to introduce Meghan to brands that she had never heard of,” Martin shared.:strip_icc()/pic234639.jpg)