Feelings of a child

How to Decipher the Emotions Behind Your Child’s…

My four-year-old daughter: You CAN’T comb my hair!

Me: It’s late—we have to leave for school in five minutes. I need to comb your hair.

My daughter: I’ll never let you comb my hair! I want wild hair!

Some version of this battle occurred daily over a very long three weeks, during which I tried five different types of brushing implements—from wide-toothed combs to wet brushes—three different kinds of spray-on conditioners, myriad forms of distraction (songs, books, TV), and, of course, the promise of lots of rewards. Yet nothing worked, for this kiddo did not want to have her hair combed. It was no use.

Quite often, we parent in what could be considered non-ideal circumstances—when we’re physiologically and emotionally running on empty and tending to many other demands. Understandably, this can result in us becoming frustrated and upset when our children refuse to heed our advice or when they continually engage in what we perceive as harmful habits.

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

When it comes to many parenting challenges with typically developing kids, simple strategies can go a long way. However, every so often, a particularly irksome parenting challenge crops up—the kind that just won’t back down in response to our go-to positive reinforcement, clear limit-setting, or distraction.

Clearly, some situations require us to dig deeper. Research suggests that parental mentalizing—the capacity to seek to understand our own and our child’s behaviors from the perspective of underlying mental states, such as thoughts, feelings, and needs—can help us get to the heart of the trickiest parenting issues.

The power of parental mentalizing

Parents who have the ability to mentalize can perceive the less obvious and less immediately apparent causes of their children’s behaviors.

When a child is angry, for example, we might be tempted to respond by giving a firm consequence, such as a time-out, or by removing something that the child likes, such as a prized toy or technology time. But a parent who mentalizes may see the hurt underneath the child’s outward anger and respond in a way that directly addresses that pain and gets to the root of the problem—for instance, by slowing down to ask the child whether they are upset and want to talk about it. In so doing, the parent may be able to remove the reason behind the anger, rather than addressing only the symptom of the problem, and may actually give the child a tool to address this issue in the future: reaching out for support.

But a parent who mentalizes may see the hurt underneath the child’s outward anger and respond in a way that directly addresses that pain and gets to the root of the problem—for instance, by slowing down to ask the child whether they are upset and want to talk about it. In so doing, the parent may be able to remove the reason behind the anger, rather than addressing only the symptom of the problem, and may actually give the child a tool to address this issue in the future: reaching out for support.

It turns out that parents who mentalize see a wide range of benefits in their children. For one, their kids develop greater attachment security, which transpires when children feel safe and secure in their relationships with their parents. Further, in one experiment, parents who mentalized more for their own children persisted longer in trying to soothe a pretend crying baby. This vividly illustrates how being able to reflect on children’s thoughts and feelings may give us the mental flexibility to try multiple approaches in responding to their distress. In turn, not surprisingly, children of parents who mentalize more are able to take better care of their own emotions, engaging in better self-regulation and -soothing.

In turn, not surprisingly, children of parents who mentalize more are able to take better care of their own emotions, engaging in better self-regulation and -soothing.

In addition, recent research suggests that mentalizing may be especially important when parents or kids are experiencing higher levels of stress or trauma. Among mothers who seemed to be more prone to stress, those who mentalized more behaved the most sensitively toward their children. After another stressful night when our toddler refuses to sleep, learning to focus on their mental states and needs could help us respond sensitively to them, and even reduce these types of battles in the future.

Mentalizing also has advantages for the parents themselves. Mentalizing can allow us to reflect on our own emotions in the parenting role, providing clarity on why our children’s behaviors activate such strong reactions in us. For instance, after being criticized for incompetence by her colleague at work one day, a mother might be able to recognize that her frustration about her child’s limit-testing behavior is exaggerated—ultimately more related to her work challenges than to her own child. Such clarity can help us identify the true source of our feelings, which in turn can assist us in regulating them. Ultimately, research suggests that parents higher in mentalizing experience greater well-being in their roles as parents.

Such clarity can help us identify the true source of our feelings, which in turn can assist us in regulating them. Ultimately, research suggests that parents higher in mentalizing experience greater well-being in their roles as parents.

OPENing up to your child

Although mentalizing sounds like a complicated concept, implementing it with your child involves only a few simple steps, represented by the term OPEN.

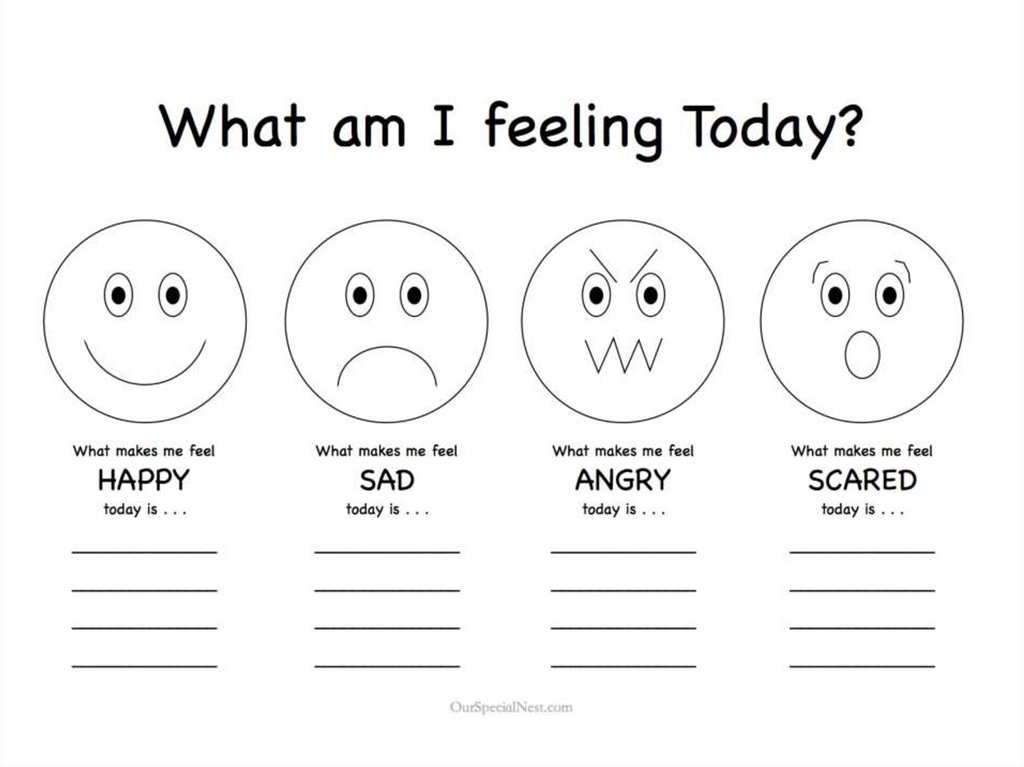

1. Reflect on your Own emotions. When you’re feeling stressed, pause and think about how you’re feeling, what you’re thinking, and what the impact of that might be on your child. Your stress is a good guide to how your child is probably feeling.

Some questions to ask yourself include:

- How am I feeling right now?

- What’s happening in my body?

- What thoughts or feelings am I having that could be impacting my parenting or my child?

For example, during a stressful parenting moment, you may realize that you’re worried about arriving late somewhere and that pressure could be impacting your behavior, making you clench your fists and grit your teeth. It may also be spilling over into your interactions with your child, causing you to speak more sternly with them.

It may also be spilling over into your interactions with your child, causing you to speak more sternly with them.

Engaging in some mindfulness practices—in the moment or at other times in your day—may also help you to avoid any destructive emotional responses to your child. Learning to check in with yourself and pay attention to your current thoughts and feelings without judgment can help you attend to your own and your child’s experiences.

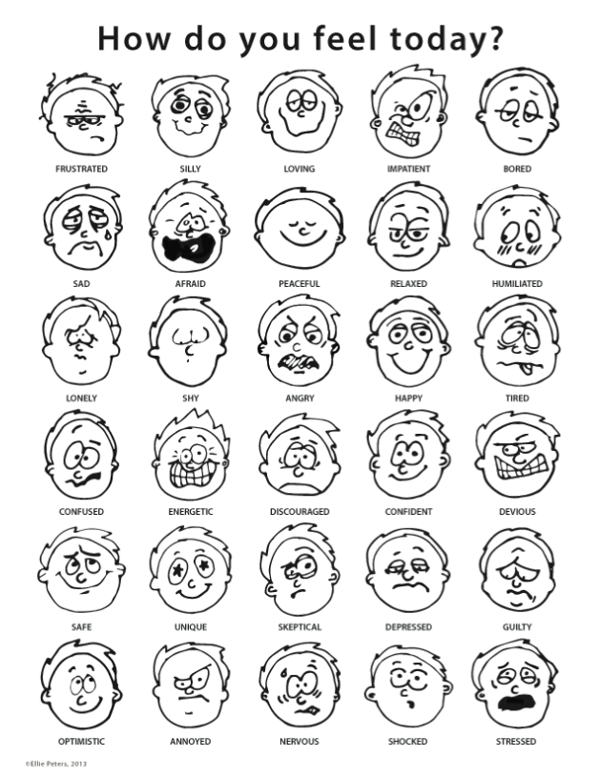

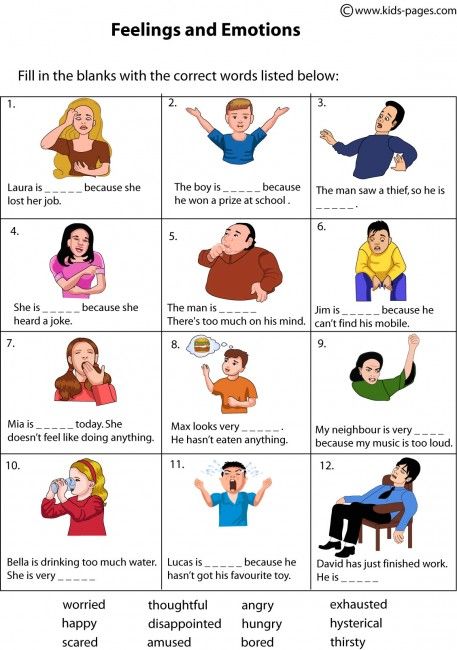

2. Pause to reflect on your child’s thoughts and feelings. When your child is exhibiting a behavior that is perplexing or upsetting to you, pause to allow yourself to think of all the different potential internal explanations for this behavior, such as the thoughts, feelings, or desires your child might have. Here, it is important to remember that often our emotions are layered, such that we may show one feeling but are actually experiencing others.

Some questions to ask yourself include:

- Is it possible my child is worried, sad, or angry right now?

- Even though my child’s behavior makes it seem as though they are angry, is it possible they are actually feeling something else that they are too scared to show?

- What underlying need might my child have that they are trying to express through their actions? How can I help them give voice to this need?

For example, if your child stomped off to a different room after an interaction with his sibling, it would be easiest to assume that he is angry. If you paused to check on what he might be feeling, you may learn that he is feeling rejected or excluded, and talking about the feelings or getting help from a parent to feel included in his sibling’s play may help him feel better.

If you paused to check on what he might be feeling, you may learn that he is feeling rejected or excluded, and talking about the feelings or getting help from a parent to feel included in his sibling’s play may help him feel better.

Trying to take a third-person perspective on the situation can help you figure out what your child may be experiencing without adding your own interpretation into the mix.

3. Engage. Slow down and ask your child what they are experiencing. Use open-ended questions and convey curiosity in understanding your child’s true thoughts and feelings, wherever they may take you. Make sure to do this at a time when your child does not have any time pressure or competing demands on their attention (a hard thing for a parent to accomplish, we know!).

Statements and questions such as the following may help set the desired tone:

- Is something on your mind?

- I’m wondering if you are feeling upset about something.

- I always want to know how you’re really doing.

4. Be open to New experiences. Once you have created the right environment to talk about your child’s thoughts and feelings, it is important to continue to convey a state of openness to new experiences. Maybe your child has always hated being the center of attention, so when a group of kids sing happy birthday to her, it would be easy to assume that she’s embarrassed. But remember to ask before assuming; you might be surprised to learn that the reason she’s actually upset is that her friends forgot to call her by her preferred nickname. It’s important to remember that, just like us, our children’s thoughts, feelings, and preferences are constantly evolving.

Past experiences serve as a database for us to reference when we encounter new situations. However, we must remain OPEN to the always-evolving child, continually revising this database. Once OPEN, always OPEN.

It turns out that my daughter’s hatred of hair combing had nothing to do with simple defiance, garden-variety limit testing, or avoidance of combing-induced pain. She did not want to comb her extremely blond hair because kids at school made comments about it when it was combed—she is the only kid in her after-school program with blond hair, which makes her stand out, something she detests. Apparently, the groomed look accentuates what makes her “different” from other kids at school, and she was nervous about getting this kind of attention. I happened upon this information when we had a conversation about the combing struggle during a nightly pre-bedtime talk—notably, a less stressful time of day, when emotions run calmer and time pressure is lower.

She did not want to comb her extremely blond hair because kids at school made comments about it when it was combed—she is the only kid in her after-school program with blond hair, which makes her stand out, something she detests. Apparently, the groomed look accentuates what makes her “different” from other kids at school, and she was nervous about getting this kind of attention. I happened upon this information when we had a conversation about the combing struggle during a nightly pre-bedtime talk—notably, a less stressful time of day, when emotions run calmer and time pressure is lower.

This is something I, a child psychologist who studies mentalizing, never would have guessed on my own. It wouldn’t have been the fourth or even the tenth explanation I would have come up with as an account for her behavior.

Knowing that my daughter was nervous about the extra attention of combed hair allowed us to come up with a plan to address the issue in a way that would mutually achieve her parents’ goals (non-tangly hair) and her goals (not attracting undue attention): gradually exposing her to increasing amounts of combing each day over a week.

Although there will undoubtedly be challenges that stump even the most gifted mentalizers, this parenting trick is a good one to have in your back pocket—even better than those amazing wet brushes—especially when all of the rewards in the world can’t untangle the situation.

Acknowledging your child’s feelings will lead to resilient kids – Child & Adolescent Behavioral Health

“One of the most important tasks of parenthood is helping children learn to deal with their emotions. All children experience periods of stress in their lives and need the emotional skills to deal with it. Children’s emotional resilience, or ability to cope with their feelings is important to their long-term happiness, wellbeing and success in life. Emotional resilience involves six key skills: recognizing and accepting feelings, expressing feelings appropriately, having a positive outlook, developing effective ways of coping, being able to deal with negative feelings, and being able to manage stressful life events. ” – Triple P: Positive Parenting Program, Raising Resilient Children Seminar Series

” – Triple P: Positive Parenting Program, Raising Resilient Children Seminar Series

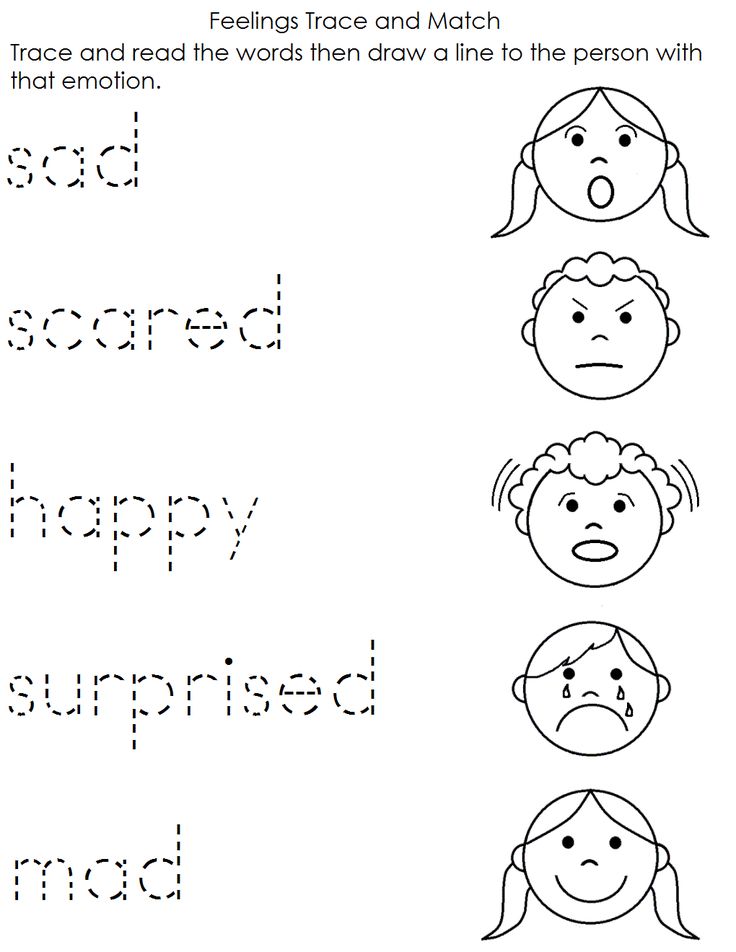

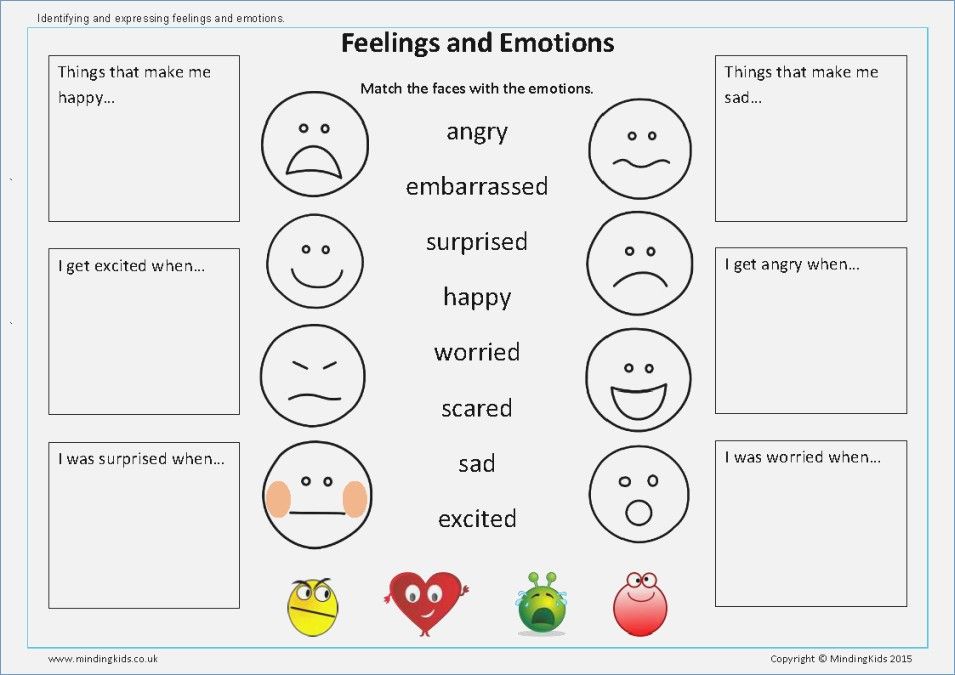

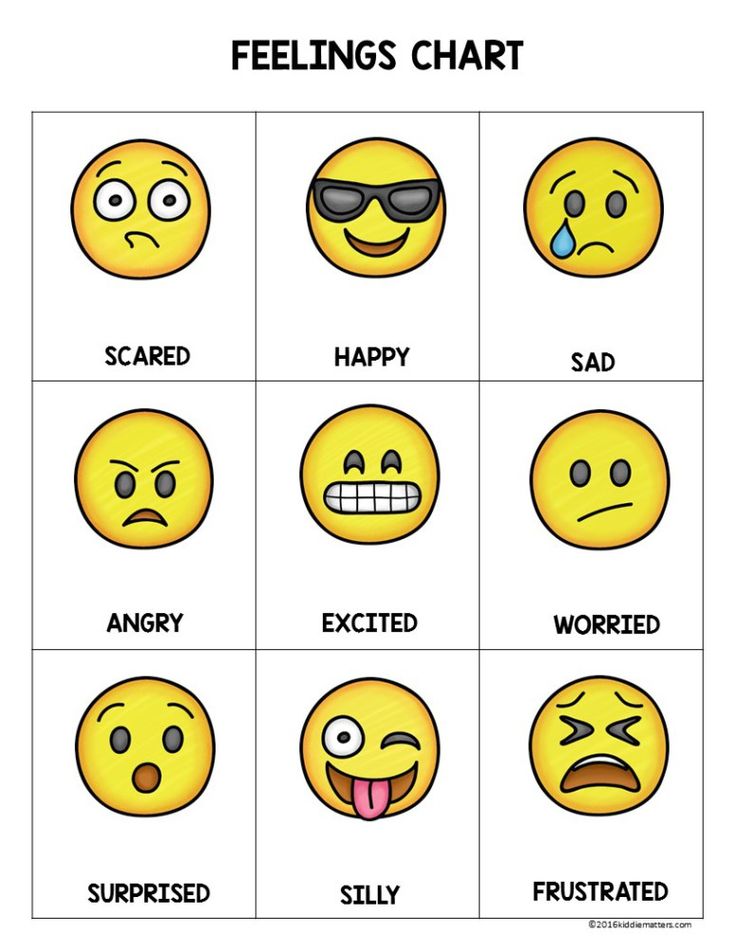

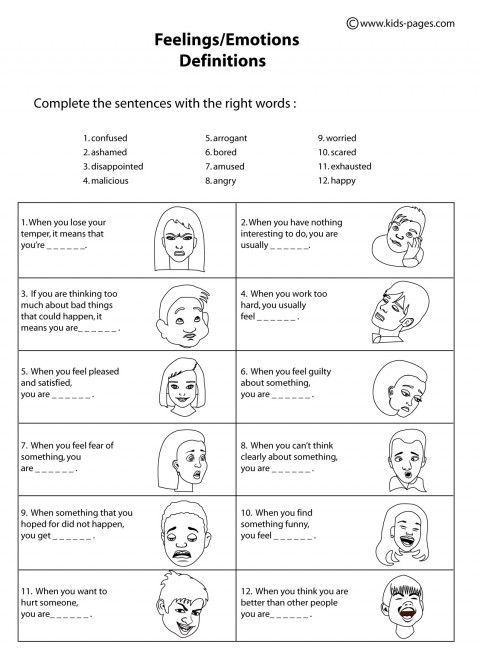

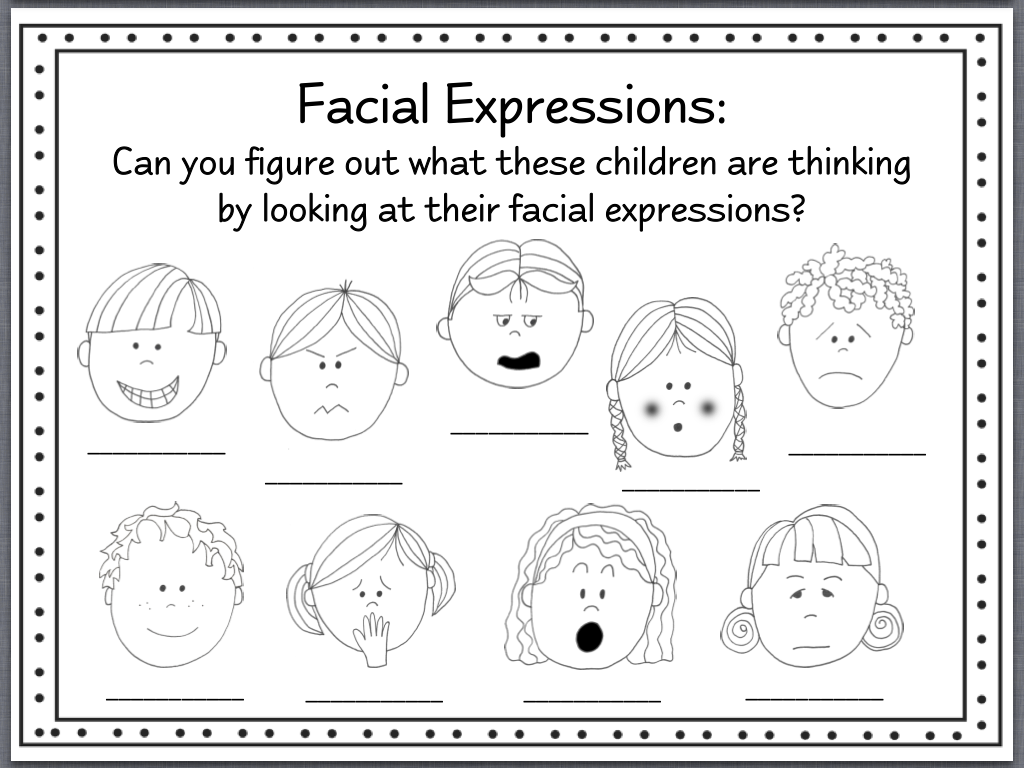

Throughout a child’s development they are receiving messages and information from the world around them, shaping the way they acknowledge and understand feelings. Some simple ways to help children enhance this development follow.

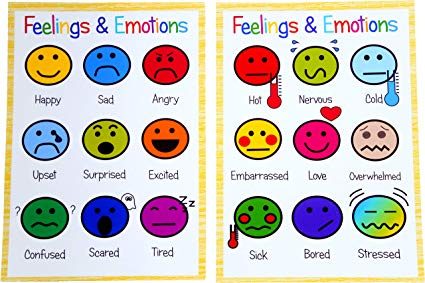

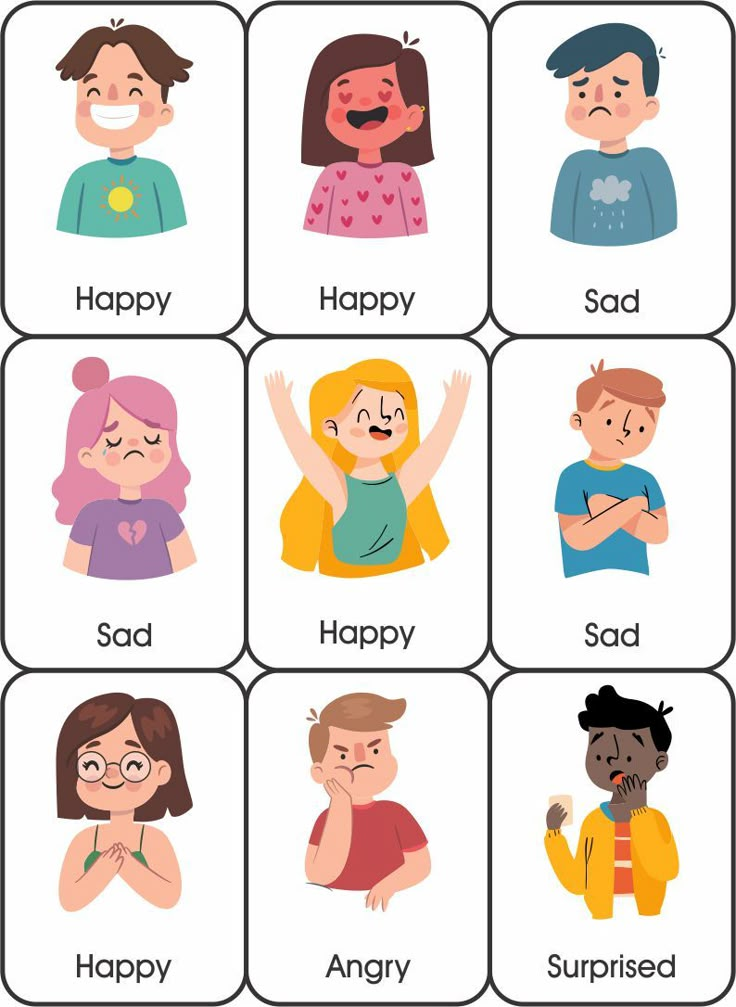

Accept different emotions – Often children receive the unwritten message that the only acceptable emotion is happy, do your best to acknowledge and accept more than just happy.

Accept all emotions; the good, the bad and the ugly. Letting children know it is okay to feel the tough and challenging emotions of mad, sad, disappointed, frustrated and more.

Talk about feelings –Talk about them regularly. Pointing out how a character on their favorite show or in their favorite book are simple ways to start these conversations.

Share your own feelings - It is okay to express our own emotions at times, modeling that we too feel sad, upset and even angry from time to time.

Help your child recognize emotions – When your child is expressing an emotion, label it. Tell them what you are seeing or hearing them do that leads you to believe they are feeling a specific emotion.

Express feelings appropriatelyChildren learn by watching, this is no different when learning how to handle, express and cope with feelings. They are constantly watching us, the adults, when we are expressing and responding to small and big emotions. It is important to do our best and modeling socially appropriate ways to express and manage emotions. Acceptable ways of expressing emotions are related to cultural and family expectations. It is important for children to learn about culture through rituals and traditions relating to emotions. Weddings, funerals and festivals teach children how their family and culture deal with celebration and loss.

Help your child talk about feelings – Avoid telling children how to feel, rather encourage them to share with you what they are thinking and feeling about the events happening around them or to them. When they start to talk to you about their feelings, stop what you are doing and give them your undivided attention. You can summarize what they share with the classic sentence starter “It sounds like you feel…”.

When they start to talk to you about their feelings, stop what you are doing and give them your undivided attention. You can summarize what they share with the classic sentence starter “It sounds like you feel…”.

Reward appropriate expression of feelings – Give positive feedback and praise to children when they do express their emotions in a developmentally appropriate way. For example, “I think you handled your anger well. I saw you get very upset, take a deep breath and walk away. Wow!”

Deal with inappropriate expression of feelings – Decide how you plan to handle the inappropriate expression of feelings like being hurtful, disrespectful, yelling, swearing or hitting others. Consistent consequences that help children learn more acceptable ways of expressing their feelings are best.

- Acknowledge the negative emotion and problem first.

- Tell them specifically and clearly what to stop doing. Short, sweet and to the point.

- Implement a logical consequence like quiet time to encourage self-regulation.

Feelings are related to what children are thinking about and telling themselves. They can only pull from the experiences they have had so far. Parents can help children develop a positive sense of self through optimism.

Encourage Optimism – Looking on the bright side of situations and finding the positive is a skill, one that can be taught and encourages. We must model this optimism. Encourage children to set realistic goals and their use of creativity and initiative to meet them. Helping children find clubs or activities they are interested in and can find success after hard work helps teach this skill.

Encourage Curiosity – Curiosity can truly become a challenge to us as parents; the questions of “why”, taking things apart or getting into things we wish they would not. Going back to the above statement, have optimism, looking at this curiosity as a strength. Curiosity is how children learn about and become interested in the world around them. Encourage this by supporting their interests in new activities, let them explore and learn about the world around them. Be available when they are excited to show you something, ask questions and teach them how to find more information about it.

Encourage this by supporting their interests in new activities, let them explore and learn about the world around them. Be available when they are excited to show you something, ask questions and teach them how to find more information about it.

Encourage Contentment – Helping children have contentment involves teaching them to be accepting, tolerant and appreciative of what they have. Model being appreciative and grateful. Talk to children about the highlight of their day. Encourage empathy and discussing other people’s point of view. Discussing acceptance of the things we cannot control or change. Boredom is an acceptable feeling to have.

Developing coping skillsCoping skills are the tools we use to help us regulate our emotions and solve the problems that may be causing or influencing negative emotions.

Help Your Child Become a Problem Solver – Sometimes we as parents fall into the trap of solving all our children’s problems. We do not like to see them upset and sometimes it is just easier to do things ourselves. You are encouraged to allow children to be in the “yuck” for a bit. Ask them questions that will help them develop skills to solve problems on their own. Encourage them to solve the problem lets them know you believe in them and develops their ability to solve problems independently one day.

We do not like to see them upset and sometimes it is just easier to do things ourselves. You are encouraged to allow children to be in the “yuck” for a bit. Ask them questions that will help them develop skills to solve problems on their own. Encourage them to solve the problem lets them know you believe in them and develops their ability to solve problems independently one day.

- State the problem clearly.

- Come up with some possible solutions.

- Think about the good points and bad points of the possible solutions.

- Decide on the best solution or plan.

- Try it out by putting the plan in to action.

- Review how the solution worked and make any necessary changes.

Encourage Positive Thinking – Encouraging again that positive thinking and self-talk is helpful here too. Encouraging children to think about the same thing in a different way to effect how they feel about it. Play games that prompt your child to imagine what someone might be thinking or feeling. Point out helpful and unhelpful ways of thinking about a situation.

Point out helpful and unhelpful ways of thinking about a situation.

Help Your Child Learn to Relax – many of our days are go, go, go. The skill of relaxation is something that must be taught. Provide a good role model of how to manage stress by looking after yourself and taking time to relax. There are many tools, apps and websites that can help with teaching yoga, belly breathing, muscle relaxation and more.

Help Your Child Look for Support – Discuss with children that everyone needs to talk about their feelings, especially when they become overwhelming. Finding safe people to talk to is important. Help them find a trusted family member, friend, teacher or counselor.

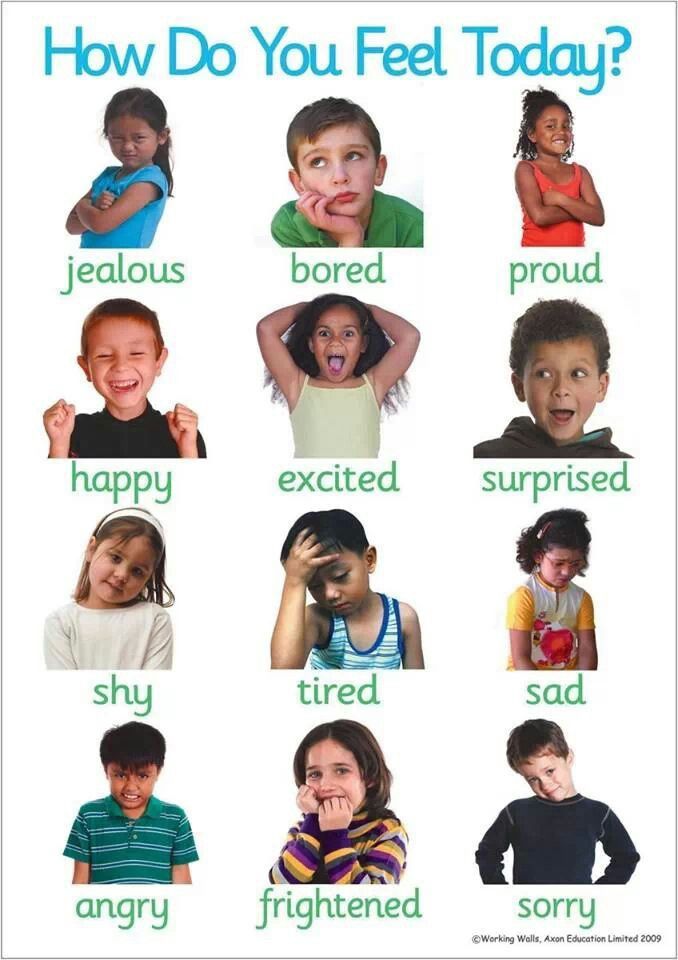

Dealing with Negative FeelingsNegative emotions are part of everyday life, we need to help children not let them become overwhelming by teaching them how to manage them. Common negative emotions include anger, anxiety, boredom, disappointment, distress, guilt, jealousy, loneliness, loss, rejection and sadness. It is not our job to protect our children from these emotions, but rather help them work through them by prompting problem solving.

It is not our job to protect our children from these emotions, but rather help them work through them by prompting problem solving.

Help Your Child Manage Negative Emotions – Notice when your child is upset and pay attention. Asking them what is wrong and listening to what they say. Label their feelings and help coach them through ways to solve the problem and feel better. Sometimes they simply want us to listen and sit in the yuck with them.

Help Your Child Learn to Cope on Their Own – Help your children deal with these negative emotions on their own by setting a good example of remaining calm. Talking with them about their anxious feelings and giving them small things to try when they want to feel better. Remember to praise them when they try new things and face their fears, reminding them when they were successful and overcoming a challenge. Simply saying, “I believe in you”, sends a positive message that you believe in them.

Coping with Stressful Life EventsWhen children are stressed by uncertainty due to a specific event ensure them of their safety and be available to help them through their emotions when needed. Allow them to be upset and encourage them to talk about it when they are ready. Encourage them to use the skills you have been working on to enhance their resiliency and check in with them often. Often in times of stress we can all struggle to remember how to solve a problem or cope. Seek professional advice if the stressful event is causing more long-term effects on you or your child.

Allow them to be upset and encourage them to talk about it when they are ready. Encourage them to use the skills you have been working on to enhance their resiliency and check in with them often. Often in times of stress we can all struggle to remember how to solve a problem or cope. Seek professional advice if the stressful event is causing more long-term effects on you or your child.

Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health's Early and Middle Childhood Program Manager Larissa Haring (LPC, OCPC, ECMHC) is an expert in the field of early childhood development with 20 years of experience. Larissa is the facilitator of the Positive Parenting Program (Triple P), which engages parents in topics parents are struggling with to be better parents. If you are looking for help to be a better parent, call C&A at 330-433-6075 or text @triplepca to 81010.

Big feelings of little children | PSYCHOLOGIES

For ParentsPractices how toKnow Yourself

“When I'm worried, it doesn't cost me anything to cry…” “I can't talk about my feelings. And why? “I am a very calm person, but sometimes – rarely – I can scream at someone terribly, and then I think: what came over me?”

And why? “I am a very calm person, but sometimes – rarely – I can scream at someone terribly, and then I think: what came over me?”

Why are we so different? Why, even in the same circumstances, each of us will always react differently? “I have such a character, I have always been like that,” we usually think. And yet there are doubts that it is exactly as we are at the present moment - timid or angry, enthusiastic or withdrawn - that we are born from the mother's womb.

First emotional experience

“The very first bodily sensations of an infant are emotionally colored,” says developmental psychologist Galina Burmenskaya. It is no coincidence that we say that in life something “touches” us, “hurts” us, because a person receives the primary emotional experience through the body.

“A baby's tactile or gustatory sensations can be pleasant, bringing comfort and pleasure, or, conversely, painful, frightening,” continues Galina Burmenskaya. “New emotions are imprinted in his memory, gradually adding to those that the child has experienced before. ”

”

But if we all start our emotional development from the same “starting position”, then where do these differences between us come from? The answer is simple: emotions come to us in one way, but how exactly they affect our further development is purely individual. The way in which a child can (or not) accept his emotions, feel them and express them, depends not only on himself.

“A child is formed not by himself, but in interaction with the people who surround him,” emphasizes Galina Burmenskaya. It is relatives that have an unusually strong influence on the emotional development of the child: they serve as an example, but also help him understand what he himself feels.

How to express emotions at home

The relationship that a child will establish with emotions depends primarily on how his parents relate to what they themselves feel. It is very difficult for children of those who are in the power of experiences and do not know how to cope with them.

“Such an explosive experience of emotions, even if it is not directed at the child, the inability to adequately express one's anger, one's aggressiveness, constant screaming and irritation are very traumatic for children,” warns Galina Burmenskaya. “It is about children from such affective families that one can hear:“ He only reacts to a cry! ”Being under constant emotional shelling, they very quickly stop responding and learn not to hear.”

“It is about children from such affective families that one can hear:“ He only reacts to a cry! ”Being under constant emotional shelling, they very quickly stop responding and learn not to hear.”

And a vicious circle is created: in order to get through to the child, parents start shouting even louder…

In other families, on the contrary, emotions are forbidden. Here they don’t talk about what they feel, you can’t admit that you are afraid, you can’t rejoice violently or get angry - it’s indecent. The prohibition may be unspoken, but the child very quickly learns that he must silence any manifestations of his soul. It's like he's turning the sound off.

“A child cannot kill his emotions, but, fearing to lose his parents' disposition, he will force them out,” explains Galina Burmenskaya. “However, such psychological defense is unproductive: the repressed problem does not disappear, experiences only accumulate. ”

”

Special case: emotional mask of parents. “I don’t understand why I perceive everything in life so tragically,” the grown child will later say. “After all, my father was always so cheerful and relaxed!” But if the constant struggle with depression was actually hiding behind the father's arousal, it is clear that the child perceived depression, which he unconsciously felt, as a model of behavior.

Whatever the mask behind which the truth of adults hides, it is with it that children identify themselves.

What can parents teach?

If a child depends on the way of life of his mother and father, he also depends on the way in which parents help him to get acquainted with his own emotions.

“A child needs the words of adults to get used to what he feels,” says Galina Burmenskaya. - He himself is still in the power of his feelings, they overwhelm him, but he does not know how to talk about them. The great role of an adult is to teach a child to put emotions into words, to make them truly “his own”. And such help from parents is especially important when the child enters public life.

And such help from parents is especially important when the child enters public life.

The first disappointments, the first friendly quarrels, the first insults, the first refusals - this is the emotional everyday life of a child who first joined the circle of his peers in a nursery, kindergarten, school. How many dramas worthy of the pen of Shakespeare, which are played out day after day in the school corridors ... and which adults often do not attach importance to!

When a child's feelings are underestimated

Whatever their personal relationship with emotions in adults, they, without realizing it, find themselves captives of the conventional view: the child is regarded as an immature person, who is presented in proportion to his height - small.

Hence everything else: adults underestimate the words of the child, underestimate the importance of his emotions: “Just think, it’s a great thing – he will cry and forget!” They question the strength of his attachments: “Well, yes, we changed the nanny, but nothing, he will get used to it . ..” They believe that the child does not yet understand what is happening around, and therefore cannot feel as strongly as adults.

..” They believe that the child does not yet understand what is happening around, and therefore cannot feel as strongly as adults.

Think (not only) about good things

Moreover, adults often believe that they protect children if they protect them from strong emotions, for example, hiding the death of someone close, illness, divorce. “And by doing this, they make a mistake, because children always feel the untruth,” says Galina Burmenskaya. “Out of good intentions, wanting to protect, adults, on the contrary, deprive the child of a sense of security: how can you feel safe if parents lie or hush up something terrible?”

In such a situation, the child cannot express his feelings: “If my mother hides this from me, I cannot tell her that I know about it and that it makes me feel bad. After all, if I tell her, she will be upset and maybe even angry. And between the child and his emotions an abyss is formed.

“Of course, it is necessary to talk to a child, given his age,” explains Galina Burmenskaya. “But to cleanse his life of everything unpleasant, sad, tragic means not to let him become a person to whom both joy and sorrow are intended by nature - and this is her great wisdom.”

“But to cleanse his life of everything unpleasant, sad, tragic means not to let him become a person to whom both joy and sorrow are intended by nature - and this is her great wisdom.”

The child is excited. How to help him?

When children are confronted with something unfamiliar, unexpected or frightening, it is not always easy for parents to find the right words to ease their feelings. How to do it?

Recall: every parent does what he can - no one has a “perfect solution”. What will be said in a difficult situation is both important and unimportant at the same time. Because the most important thing for a child is:

-

For the words to be spoken. Thanks to this, his sadness will “speak” and move from the status of a crushing “blow” to another, of course, also painful, but which can be overcome.

-

That a loving adult is willing to listen. He recognizes him as a person who is trustworthy and arousing interest. He shares his grief and will always lend his shoulder.

What can I say? And to do?

1. Sudden death

The truth is always painful, but never destructive - just the opposite. If the child is supported, then the situation turns out to be favorable for him in the end. He comes out of it matured, as he is taken seriously. Therefore, it is very important to tell the truth, to give him the right to share grief with adults.

2. A quarrel broke out between the parents

It is important that the child knows that:

-

It is not his parents who are quarreling, but the husband and wife, a couple that was formed apart from his participation.

-

He is not the cause of the quarrel, even if it started with a problem that concerns children.

-

It is not for him to be a judge or a comforter.

Having indicated this, it is important to show that he can express his feelings (anxiety, fear) that the quarrel caused him.

3. He says that his friend does not want to be friends with him

Explain to the child that:

-

This does not mean that he is not worthy of love.

-

Whatever he is, he cannot be loved by everyone without exception.

-

Perhaps he reminds a friend of someone he doesn't like. Or he did something, unwittingly, that his friend did not like.

-

There are many other children around. Who can he count on in class? What new friend could he make?

4. If he is angry

Important:

-

Separate anger from the reason that causes it. Emotion is always legal, each of us has the right to "get nervous", even if others do not approve of it.

-

Show sympathy, sympathize with him and talk to him about what causes anger.

-

If anger is caused by a ban, this does not prevent you from supporting it: "I understand that this is difficult to accept, but the rule is necessary." Having said this and making sure that the child is speculating on his anger, you can advise him to show emotions in a different way, for example, with the help of words.

Or send him to deal with anger in another room, depriving him of the audience ...

Or send him to deal with anger in another room, depriving him of the audience ...

To help your child express emotions, you must also prevent him from speculating with them and teach him not to let them overwhelm him.

Associate Professor, Department of Developmental Psychology, Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov, scientific editor of the bestseller "Affection" by John Bowlby.

Personal website

Text: Daria Mikheeva Photo source: Getty Images

New on the site

“I fell in love with a colleague who just decided to have fun with me”

A cry from the soul: what kind of injuries our voice can tell about

How to stop worrying about what others think: 8 important tips - listen to them

No bad mood: 5 ways to brighten up your life

Stop it now! Psychotherapist on how porn addiction destroys our lives and how to overcome it

“Fear of death translates into denial of peace”: what is the book “The Water Strider” about - read the excerpt

3 main causes of eating disorders

“Young man listens more to the blogger by relationship than to me”

The world of your child's emotions and feelings and their manifestation in behavior

The world of a child's emotions and feelings is diverse and rich in content. Speaking about these feelings and emotions, I would like to bring to your attention a metaphor for a jar of feelings and emotions.

Speaking about these feelings and emotions, I would like to bring to your attention a metaphor for a jar of feelings and emotions.

Initially, love lives in the heart of a child, and for the manifestation of his love, the child receives the love of his parents. But this does not always happen, and at some point, showing his love, he receives the displeasure of mom or dad.

And in response, there is resentment and pain from the fact that they did not understand, did not accept.

After experiencing resentment and pain, it is already scary to express your love again, and suddenly they will not understand again, they will not accept, they will push you away. There is fear and anxiety.

And when it becomes scary and anxious, you no longer want to express your love, and as a sign of protest, irritation and anger appear at someone who is not ready to accept my love and is not worthy of my love.

But anger and irritation cannot always be expressed, it is impossible to be angry, to be irritated too, and then a mask of indifference and indifference appears.

Let's look at where the child's negative behavior comes from. Here is another jar in front of you, revealing what is hidden behind the behavior of the child. And feelings are hidden behind any behavior, and these feelings are expressed in actions, which is directly the behavior itself. Let's see how it goes.

Anger, malice, aggression are manifested in the external behavior of a person through familiar name-calling and insults, quarrels and fights, punishments, actions “out of spite”, protest, etc.

Now let's think about what causes anger?

Psychologists note that: anger is a secondary feeling, and comes from experiences of a completely different kind, like pain, fear, resentment. All feelings of the second layer are suffering, they contain suffering (pain, fear, resentment).

Tell me, please, is it always easy for you to talk about your feelings? How can I do that? This can be done through the "I-messages" technique. Please name your feeling now using the pronoun "I" - "I feel . ..". They are not easy to express about them, they are usually hushed up, hidden. Why? For fear of humiliation, to appear weak. Sometimes a person himself does not realize them (I'm just angry, but I don't know why!). To hide feelings of resentment and pain is often taught from childhood: “Don’t cry, better learn to fight back!”

..". They are not easy to express about them, they are usually hushed up, hidden. Why? For fear of humiliation, to appear weak. Sometimes a person himself does not realize them (I'm just angry, but I don't know why!). To hide feelings of resentment and pain is often taught from childhood: “Don’t cry, better learn to fight back!”

For a person to discover what he feels means to open himself to another. What will the other person think of me? Will I be rejected? Will the other person think less of me? It is especially difficult for parents to become "transparent" to their children because they like to be seen as infallible - without weakness, vulnerability, inadequacy.

Many parents find it easier to hide their feelings behind a "You-message" that blames the child than to reveal their own humanity.

"You are acting like a child."

"You should have done that."

"You should know this."

But when a parent simply tells the child how some unacceptable behavior makes the parent feel, the message becomes "I-message.

"I worry and worry about you when you come home late." diagram and answer the question: why do negative feelings arise? Psychologists give the answer: the cause of pain, fear, resentment is in the dissatisfaction of needs. Every person, regardless of age and gender, needs food, security, communication. A person needs: to be loved, understood, recognized, respected.So that he was needed and close to someone: so that he had success in business, studies, so that he could realize himself, develop his abilities, improve himself, respect himself.These needs are always at risk!

Let's go back to the chart and see if there's anything below the layer of needs? It turns out there is! Attitude towards oneself.

Psychologists have devoted much research to such experiences of the self. They call them differently: self-perception, self-image, self-assessment, self-esteem. Renowned family therapist Virginia Satir called this a sense of self-worth. Several important factors have been proven that this greatly affects the life and even the fate of a person. In childhood, we learn about ourselves only from the words and attitudes of those close to us. The child has no inner vision. His image of himself is built from the outside; he begins to see himself as others see him. How to raise self-esteem in a child? However, in this process the child does not remain passive. There is another law of all living things at work here: to actively pursue that on which survival depends. A positive attitude towards oneself is the basis of psychological survival, and the child constantly seeks and even fights for it. He expects confirmation from us that he is good, they love him, that he can cope with feasible tasks. Whatever the child does, he needs our recognition of his success. At the bottom of the emotional jar, the most important “jewel” given to us by nature is the feeling of the energy of life. "I am" or more pathetically: "This is I" It is enough to see how he meets a new day: with a smile or cry, this is a feeling of inner well-being or trouble that the child experiences.

In childhood, we learn about ourselves only from the words and attitudes of those close to us. The child has no inner vision. His image of himself is built from the outside; he begins to see himself as others see him. How to raise self-esteem in a child? However, in this process the child does not remain passive. There is another law of all living things at work here: to actively pursue that on which survival depends. A positive attitude towards oneself is the basis of psychological survival, and the child constantly seeks and even fights for it. He expects confirmation from us that he is good, they love him, that he can cope with feasible tasks. Whatever the child does, he needs our recognition of his success. At the bottom of the emotional jar, the most important “jewel” given to us by nature is the feeling of the energy of life. "I am" or more pathetically: "This is I" It is enough to see how he meets a new day: with a smile or cry, this is a feeling of inner well-being or trouble that the child experiences. The further fate of this feeling is dynamic, and sometimes dramatic. With each appeal to the child - by word, deed, intonation, gesture, frowning eyebrows and even silence, we tell him not only about ourselves, our condition, but always about him, and often - mainly about him. The child often perceives punishment as a message: "You are bad", criticism of mistakes - "You cannot", avoidance - "You are not loved." Punishment, and even more so self-punishment of the child, only exacerbates his feeling of trouble and unhappiness.

The further fate of this feeling is dynamic, and sometimes dramatic. With each appeal to the child - by word, deed, intonation, gesture, frowning eyebrows and even silence, we tell him not only about ourselves, our condition, but always about him, and often - mainly about him. The child often perceives punishment as a message: "You are bad", criticism of mistakes - "You cannot", avoidance - "You are not loved." Punishment, and even more so self-punishment of the child, only exacerbates his feeling of trouble and unhappiness.

We are not always able to listen and feel the experiences of both our own and others. And sometimes we don’t know where to start and change the situation for the better. Now you can use the jar of emotions to better understand what level of problem you are dealing with in each case.

Active listening can help you understand your child's feelings and needs.

Active listening is a powerful tool in helping children discover their real needs and true feelings.

Active listening is a way for children to understand that their proposed solutions are understood by their parents and accepted.

"I-messages" are important to let children know how parents feel, without humiliating the child through blame and shame. "You-messages" in resolution Conflict usually provokes counter-"You-messages" and leads the discussion to an unproductive verbal fight, where each seeks to hurt the other more.

And in conclusion, I would like to give you a number of recommendations in communicating with your child.

1. Observe your child's behavior, track it and try to understand how your child feels when doing certain actions, what needs are hidden behind these feelings, how -I, self-image are related to these needs of your child, and where does he get such an idea of himself, maybe his true essence is completely different? Help him see his true nature, hidden behind the self-image created by the outside world.

2. Observe your child's emotions and feelings and try to understand what feeling is hidden behind the feeling that the child presents to you openly.