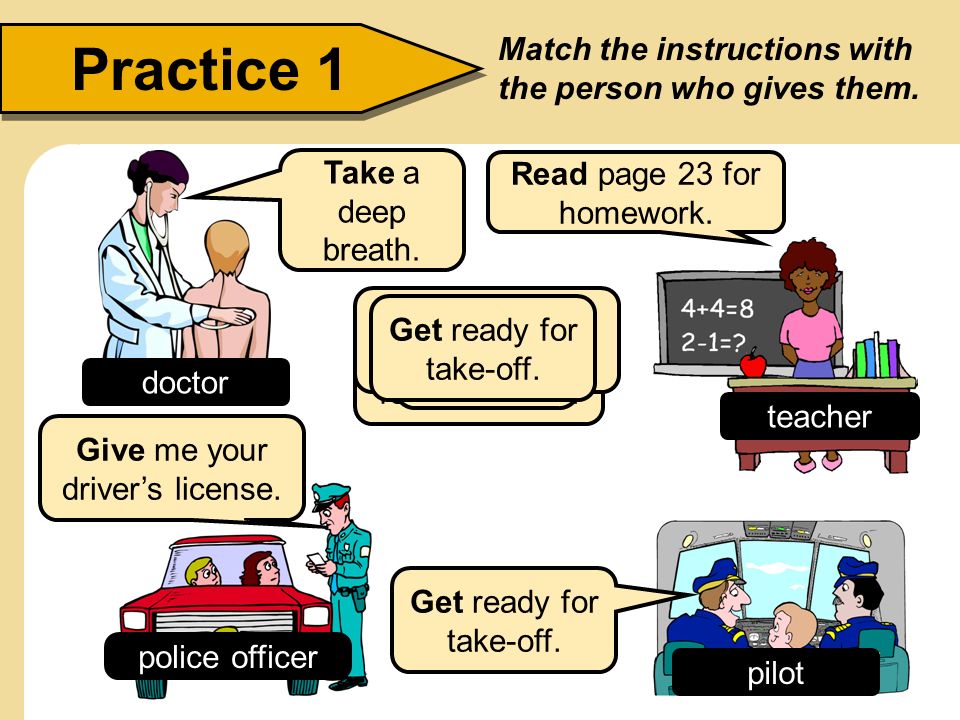

Following instructions is very important

The Psychology of Following Instructions and Its Implications

Am J Pharm Educ. 2020 Aug; 84(8): ajpe7779.

doi: 10.5688/ajpe7779

, PharmD,a, BS,a and , PhDa,b

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

The ability to follow instructions is an important aspect of everyday life. Depending on the setting and context, following instructions results in outcomes that have various degrees of impact. In a clinical setting, following instructions may affect life or death. Within the context of the academic setting, following instructions or failure to do so can impede general learning and development of desired proficiencies. Intuitively, one might think that following instructions requires simply reading instructional text or paying close attention to verbal directions and performing the intended action afterward. This commentary provides a brief overview of the cognitive architecture required for following instructions and will explore social behaviors and mode of instruction as factors further impacting this ability.

Keywords: following instructions, working memory, metacognition, social psychology, teach-back method

Following instructions is an important ability to practice in everyday life. Within an academic setting, following instructions can influence grades, learning subject matter, and correctly executing skills. In this commentary, we provide an overview of the primary factors that influence the ability of an individual to follow instructions. We translate these findings from the psychological literature into practical guidelines to follow in the educational setting.

Literature on following instructions first surfaced in the late 1970s.1 Researchers observed a subset of housewives who demonstrated a preference to tinker with a new home appliance to get it started or watch a demonstration video on how to set it up rather than read the accompanying instruction manual. Since then, numerous factors that influence following instructions have been investigated including a person’s working memory capacity,2-6 societal rules,

7-9 history effects,7 self-regulatory behavior,10,11 and instruction format. 3,6 Although not completely independent of each other, these factors warrant some individual attention to better understand their implications on following instructions.

3,6 Although not completely independent of each other, these factors warrant some individual attention to better understand their implications on following instructions.

Working Memory and Following Instructions

Working memory is the brain’s workbench, linking perception, attention, and long-term memory.12,13 As an example, in the classroom setting, learners may receive information visually from slides and/or auditorily from instructor narration. However, only items that learners pay attention to within the environment enter their working memory. These items are then processed, resulting in the formation of a mental representation (ie, encoding) that effectively moves from working memory to long-term storage. Thus, working memory performance is an important intermediary between perception and learning. Because working memory capacity is limited,

14 a person’s ability to follow instructions may be impacted if the instructional load is greater than that capacity, ultimately leading to information loss (for more information, explore cognitive load theory15,16). This loss of information may be more pronounced when a task must be performed immediately and the presentation rate of instructions cannot be controlled by the user. Imagine a student named Dennis. During class, Dennis is nervous about an upcoming examination and this emotional state preoccupies his working memory, leading to, in that moment, a lower working memory performance. As a result, when the professor gives verbal instructions for an upcoming assignment, the amount of instructional load supersedes Dennis’ capacity to hold on to those instructions in his working memory. Because he cannot hold on to those instructions, he is less likely to store them in his long-term memory and will not be able to refer to them later when completing the task. To summarize, the ability to hold instructions within working memory is necessary to execute the desired function; thus low working memory performance can compromise a student’s ability to follow instructions.

2 If a student cannot process or hold instructions in working memory, they will probably fail to complete a given task correctly.

This loss of information may be more pronounced when a task must be performed immediately and the presentation rate of instructions cannot be controlled by the user. Imagine a student named Dennis. During class, Dennis is nervous about an upcoming examination and this emotional state preoccupies his working memory, leading to, in that moment, a lower working memory performance. As a result, when the professor gives verbal instructions for an upcoming assignment, the amount of instructional load supersedes Dennis’ capacity to hold on to those instructions in his working memory. Because he cannot hold on to those instructions, he is less likely to store them in his long-term memory and will not be able to refer to them later when completing the task. To summarize, the ability to hold instructions within working memory is necessary to execute the desired function; thus low working memory performance can compromise a student’s ability to follow instructions.

2 If a student cannot process or hold instructions in working memory, they will probably fail to complete a given task correctly.

There are two potential strategies to assist the learner in this situation. One strategy is to have the learner immediately act on the received information.17 A common example of this is the teach-back method, which is a practice of enactment. The practice of enactment has demonstrated greater retention of new information.4,5 This line of research has shown that the accuracy of recalling instructions was increased when immediately after instruction, actions were performed at both the initial learning phase (ie, encoding) and later during recall. The second strategy is to use different forms of instructions (eg, written and verbal), which allows the learner to control the rate of presentation. If the learner can control the rate, they can review the instructions as needed or go at a slower pace to fully encode the instructions.18,19

Societal Rules and History Effects

Following instructions is a behavior, and most human behavior depends on social context. Part of the social context is the presence of another individual. The mere presence effect is the phenomenon that human behavior changes when another human is around.9 The presence of another person can make an individual more pliant. Being more or less pliant, or pliance, describes behavior that is controlled by a socially mediated consequence. As an example, if an instructor tells a student to write their name at the top of a test sheet and the student does so to gain the instructor’s approval, this is a ply and the student is being pliant. Imagine a student, Angela. She follows instructions because she feels it is a professional expectation that her mentors and peers have. Angela will be pliant because following instructions has a social consequence. For this to occur, however, the instructor must monitor the completion of the task, possess the ability to impose a consequence, and observe the effect of the consequence on the student. Donadeli and colleagues8 explored the effect of the magnitude of nonverbal consequences, monitoring, and social consequences on instruction following.

Part of the social context is the presence of another individual. The mere presence effect is the phenomenon that human behavior changes when another human is around.9 The presence of another person can make an individual more pliant. Being more or less pliant, or pliance, describes behavior that is controlled by a socially mediated consequence. As an example, if an instructor tells a student to write their name at the top of a test sheet and the student does so to gain the instructor’s approval, this is a ply and the student is being pliant. Imagine a student, Angela. She follows instructions because she feels it is a professional expectation that her mentors and peers have. Angela will be pliant because following instructions has a social consequence. For this to occur, however, the instructor must monitor the completion of the task, possess the ability to impose a consequence, and observe the effect of the consequence on the student. Donadeli and colleagues8 explored the effect of the magnitude of nonverbal consequences, monitoring, and social consequences on instruction following. They observed that the presence of an observer and social reprimand for not following instructions improved the rates at which people followed instructions. This suggests that societal constructs, such as following authority figures and the fear of reprimand, may be drivers in motivating people to follow directions.

They observed that the presence of an observer and social reprimand for not following instructions improved the rates at which people followed instructions. This suggests that societal constructs, such as following authority figures and the fear of reprimand, may be drivers in motivating people to follow directions.

There are two possible ways to address societal effects on following instructions. The first way is to establish an expectation of professionalism by explaining why instruction following is important. This would be consistent with aspects of social identity theory.20,21 The second way is to create the fear of reprimand. In this case, faculty members hold students responsible for following the rules. This could be with respect to assignment formatting, assignment deadlines, or other aspects that might be tied to a penalty.

Following instructions is affected by the presence of another person even if there is no history of reinforcement for such behavior, suggesting that instructional control may be strengthened by social contingencies. 7,8 However, societal rules can lead to history effects. If students never receive feedback on or consequences for their inability to follow instructions, history effects dictate they will continue that behavior. Now imagine a student named Amber. Amber wrote down the instructions during class but did not follow them because she generally does well on her assignments despite not completely following the instructions. As such, she abstained from following the rules because a consequence was not associated with not following them.

7,8 However, societal rules can lead to history effects. If students never receive feedback on or consequences for their inability to follow instructions, history effects dictate they will continue that behavior. Now imagine a student named Amber. Amber wrote down the instructions during class but did not follow them because she generally does well on her assignments despite not completely following the instructions. As such, she abstained from following the rules because a consequence was not associated with not following them.

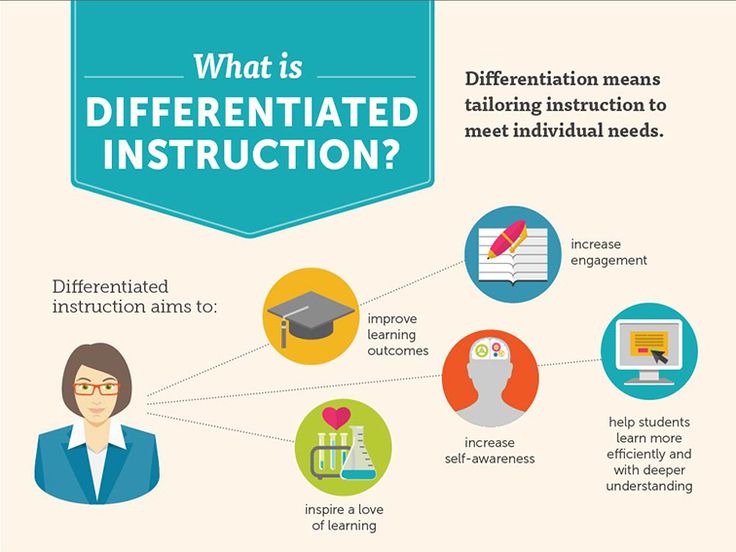

Metacognition and Self-regulation

Following instructions also depends on self-regulation, ie, a person’s awareness of their own behavior to act in a manner that optimizes their best long-term interests.22 To do so, an individual must be aware of their own thoughts and actions. This awareness plays a role in metacognitive monitoring, or a person’s monitoring of their own thoughts and behaviors.

Metacognition has been described as thinking about thinking. 23 At its core, it is about planning, monitoring making progress, and evaluating the completion of a process. For instance, if a student is asked to conduct a journal club meeting, the planning stage would involve gaining an understanding of what is required to successfully complete a journal club meeting. This could include time needed for completion or where to look for an article. The monitoring phase is the awareness to review the article and pull out key information. The final part, evaluation, involves checking the work to determine whether goals were met.

23 At its core, it is about planning, monitoring making progress, and evaluating the completion of a process. For instance, if a student is asked to conduct a journal club meeting, the planning stage would involve gaining an understanding of what is required to successfully complete a journal club meeting. This could include time needed for completion or where to look for an article. The monitoring phase is the awareness to review the article and pull out key information. The final part, evaluation, involves checking the work to determine whether goals were met.

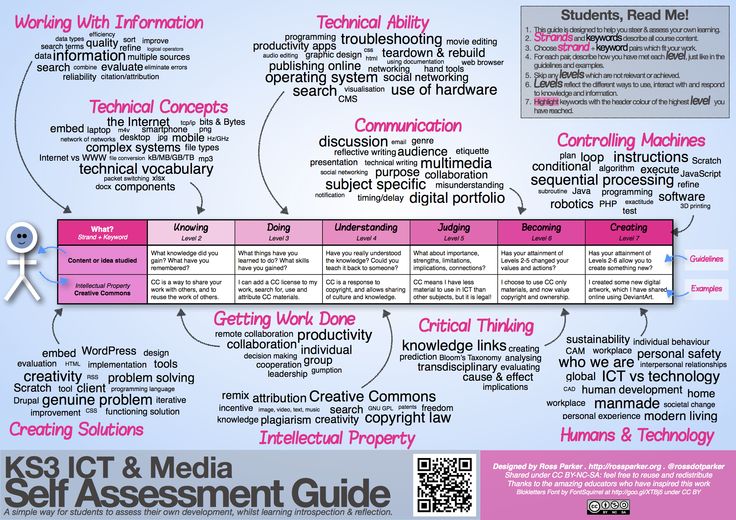

Imagine a student named Craig. Craig wrote down instructions for an assignment, but after completing the assignment, he did not review the instructions to ensure he followed them correctly. He failed to monitor his progress. As such, the ability to be metacognitively aware can be a key piece in following instructions. In this case, individuals may not follow instructions because they are poor monitors of their learning. 22,24-28 Students may not adequately plan before tackling their assignment, such as by reading instructions beforehand. Next, they may not monitor their progress during completion of the assignment. And finally, once students think they have completed the task, they may not go back and read the instructions to ensure they have fulfilled all expectations. To help them with this and other aspects of instruction, students may need to use accountability (societal rules) as a primary source of motivation. Without accountability, students may not follow instructions, thus perpetuating poor metacognitive skills, leading to unawareness of what they know, what they do not know, and the process to correct errors. A strategy may be the use of checklists to help students monitor their thoughts during a process (see Tanner29 and Medina and colleagues30 for a review of methods to develop metacognition).

22,24-28 Students may not adequately plan before tackling their assignment, such as by reading instructions beforehand. Next, they may not monitor their progress during completion of the assignment. And finally, once students think they have completed the task, they may not go back and read the instructions to ensure they have fulfilled all expectations. To help them with this and other aspects of instruction, students may need to use accountability (societal rules) as a primary source of motivation. Without accountability, students may not follow instructions, thus perpetuating poor metacognitive skills, leading to unawareness of what they know, what they do not know, and the process to correct errors. A strategy may be the use of checklists to help students monitor their thoughts during a process (see Tanner29 and Medina and colleagues30 for a review of methods to develop metacognition).

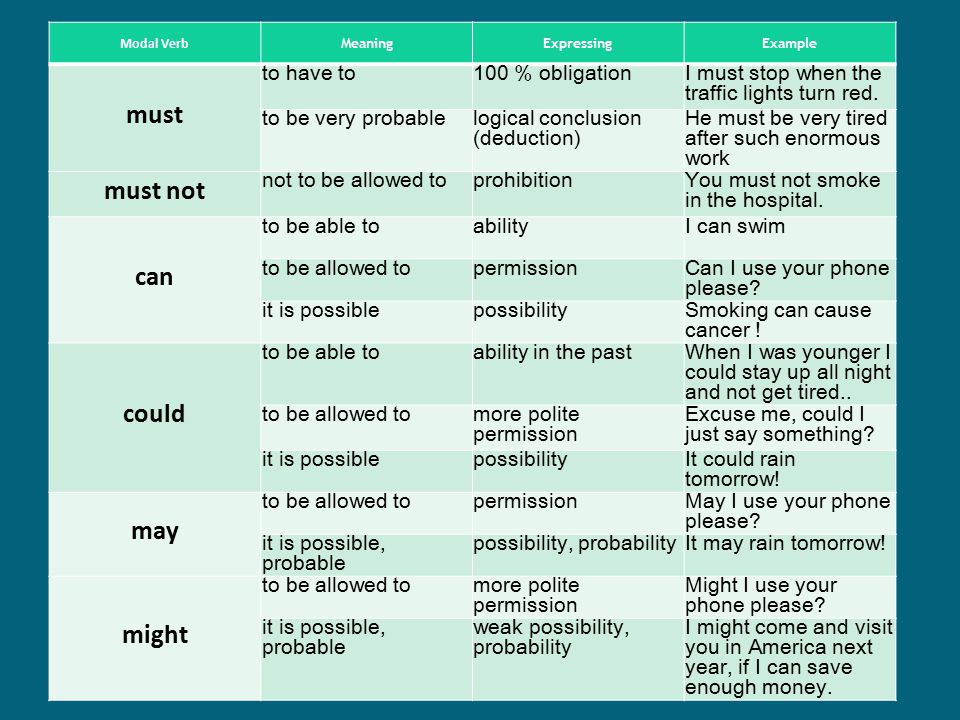

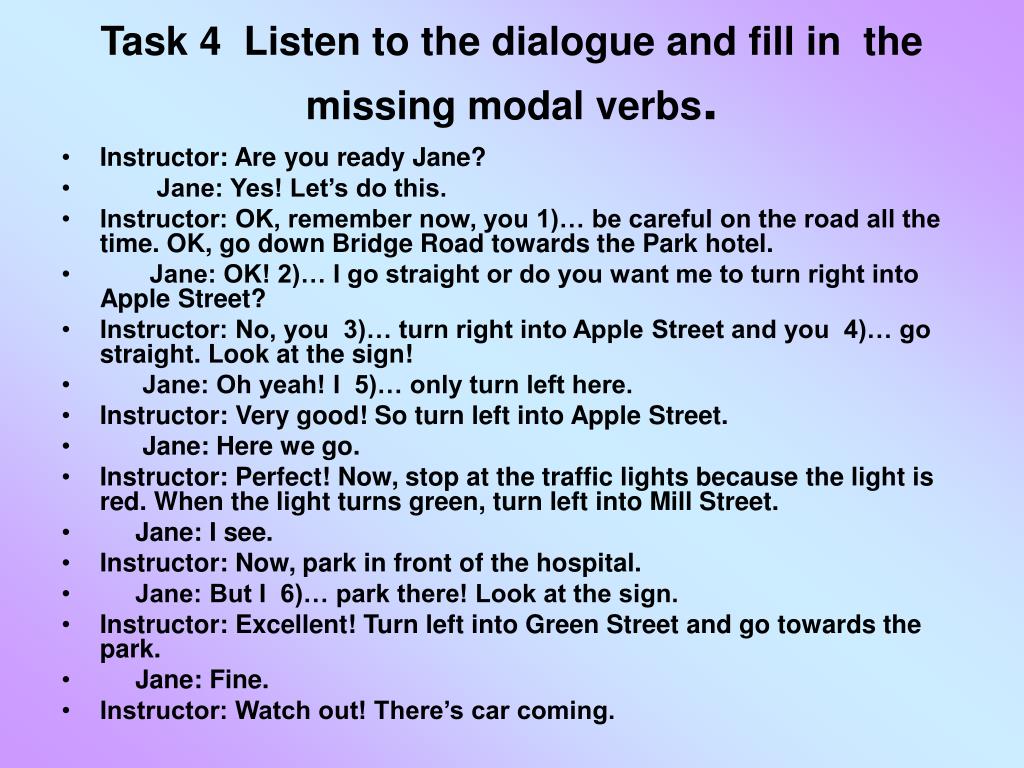

Verbal vs Written Instructions

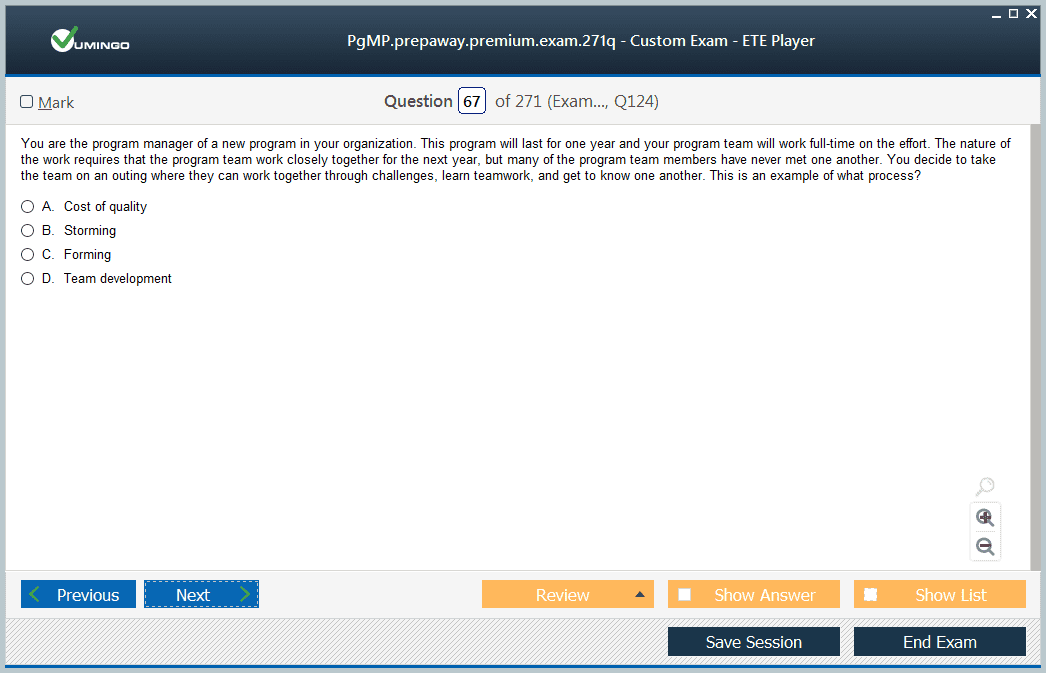

When examining best practices for conveying instructions to learners, the instructor should consider whether instructions are best retained and applied if received in a verbal versus a written format. To date, no published studies have examined whether one format offers greater benefit over another; however, one study explored both formats in relation to working memory.6

To date, no published studies have examined whether one format offers greater benefit over another; however, one study explored both formats in relation to working memory.6

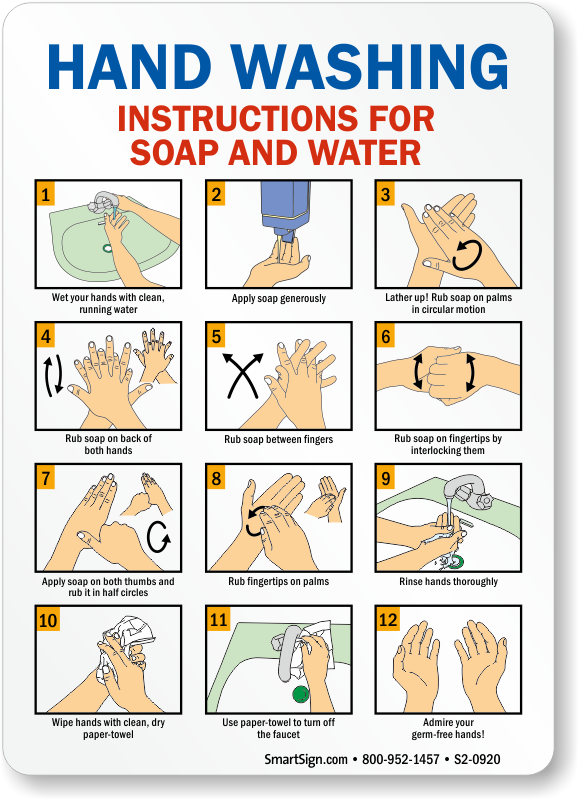

Written instructions are efficient because large amounts of detail can be provided that students can read rapidly. Thus, step-by-step manuals can be found for almost all electronic devices. While there is a large body of literature describing the mechanics of how we read, there are some important points to underscore.6 When reading and following instructions, a person will act in the same sequence in which action items are presented in the text. In the television show MASH (season 1, episode 20), one of the characters was instructed to “…cut wires leading to the clockwork fuse at the head, but first remove the fuse.” He proceeded to cut the wires before removing the fuses. He acted in the same sequence in which the instructions were presented but failed to follow the actual instructions. This raises an important point: individuals are more likely to remember instructions when the order is consistent with how events occur. 6 Writing instructions according to the sequence of actions the reader needs to take may lead to better results. For example, “do A before doing B’ is a superior form of wording instructions than stating, “before doing A, do B,” as illustrated in the above scenario.

6 Writing instructions according to the sequence of actions the reader needs to take may lead to better results. For example, “do A before doing B’ is a superior form of wording instructions than stating, “before doing A, do B,” as illustrated in the above scenario.

Spoken instructions are advantageous in face-to-face interactions (eg, within the classroom). Spoken instructions are processed through the phonological loop, a component of working memory focused on verbal information, which is more flexible and convenient. Intrinsically, listening requires less effort than reading. Spoken words can also be paired with visual aids to guide action, such as in measuring blood pressure or administering an immunization.6 Remarkably, individuals cannot read and follow visual objects at the same time. Combining text with pictures can be more taxing to working memory than combining spoken words and visuals. A drawback associated with spoken words is the rate of presentation. While the speed at which text is read can be controlled by the end user, the instructor’s speed of speech cannot. The phonological loop mediates the ability to hold and process auditory information.13,31 Items (bits of information) in the phonological store can rapidly decay, and because items are usually chained in such a way that an item primes the next item,31 one lost step can lead to the loss of all subsequent steps (eg, if a student cannot remember step 3, she is unlikely to recall any step after that). To prevent this loss, people tend to “rehearse” following instructions by repeating the instructions to themselves.3 Access to both written instructions and verbal instructions may prove beneficial, as written instructions can be referred to if any verbal instruction is missed.

While the speed at which text is read can be controlled by the end user, the instructor’s speed of speech cannot. The phonological loop mediates the ability to hold and process auditory information.13,31 Items (bits of information) in the phonological store can rapidly decay, and because items are usually chained in such a way that an item primes the next item,31 one lost step can lead to the loss of all subsequent steps (eg, if a student cannot remember step 3, she is unlikely to recall any step after that). To prevent this loss, people tend to “rehearse” following instructions by repeating the instructions to themselves.3 Access to both written instructions and verbal instructions may prove beneficial, as written instructions can be referred to if any verbal instruction is missed.

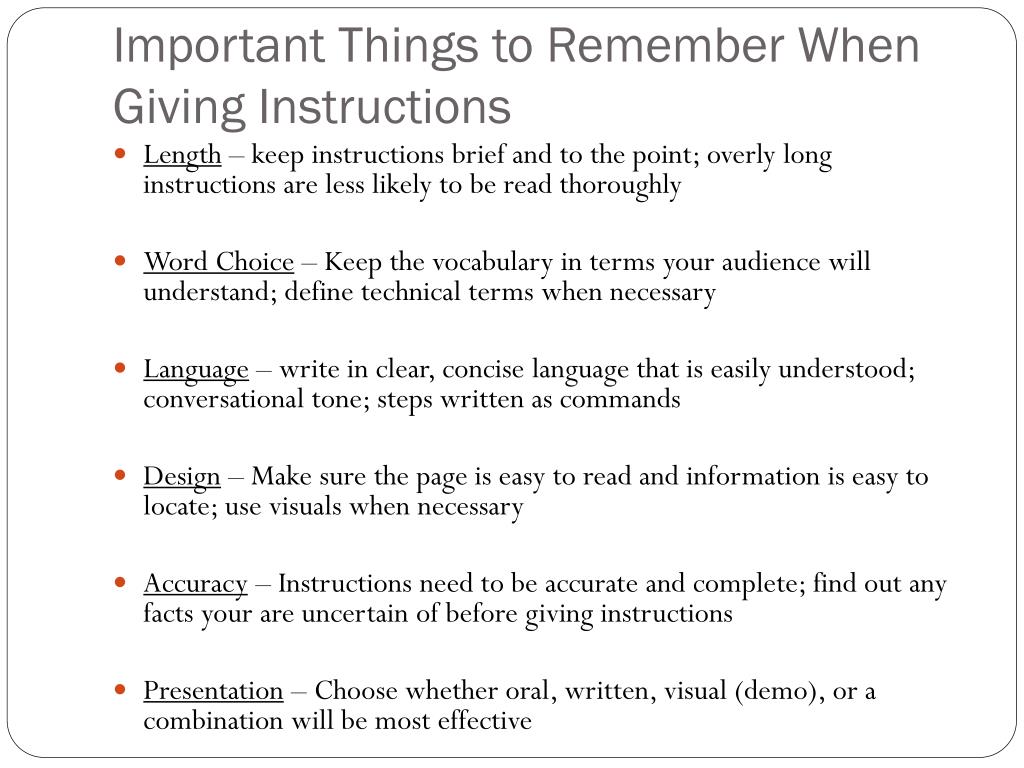

Several factors can impact a student’s ability to follow instructions. Recommendations to increase the probability of learners following instructions are available within the literature (). While these modalities may not guarantee success, these recommendations should increase the probability that most students will follow instructions. Although we cannot extrapolate from current literature whether one mode of instruction delivery is preferred over another, we can apply some of these findings to pharmacy students in a learning environment where instructions are used to guide the completion of deliverables. The first thing the instructor can do is provide both written and verbal instructions. These instructions should be concise, written in student-friendly language, and given in order of operation (ie, step A then step B). Students can read (and reread the written instructions), which should minimize errors resulting from not paying attention or insufficient working memory. Although distracted when verbal instructions were given, a student can review written instructions in a self-paced manner, thus reducing cognitive load and increasing the probability of remembering them.

While these modalities may not guarantee success, these recommendations should increase the probability that most students will follow instructions. Although we cannot extrapolate from current literature whether one mode of instruction delivery is preferred over another, we can apply some of these findings to pharmacy students in a learning environment where instructions are used to guide the completion of deliverables. The first thing the instructor can do is provide both written and verbal instructions. These instructions should be concise, written in student-friendly language, and given in order of operation (ie, step A then step B). Students can read (and reread the written instructions), which should minimize errors resulting from not paying attention or insufficient working memory. Although distracted when verbal instructions were given, a student can review written instructions in a self-paced manner, thus reducing cognitive load and increasing the probability of remembering them. The instructor could then employ metacognitive monitoring and assess the student’s understanding of the instructions by including a checklist within the assignment, ie, a strategy to help Craig monitor his learning and check his work (much like journals have checklists for authors). Finally, the instructor should penalize students for not following the instructions thereby using the social context to reinforce their need to follow instructions. Amber benefits by learning there are consequences for not following instructions. For Dennis and Craig, the threat of punishment in the form of lost points may motivate them to review the instructions to ensure they have done their work correctly, a process which can improve their attention (Dennis) and metacognitive monitoring (Craig).

The instructor could then employ metacognitive monitoring and assess the student’s understanding of the instructions by including a checklist within the assignment, ie, a strategy to help Craig monitor his learning and check his work (much like journals have checklists for authors). Finally, the instructor should penalize students for not following the instructions thereby using the social context to reinforce their need to follow instructions. Amber benefits by learning there are consequences for not following instructions. For Dennis and Craig, the threat of punishment in the form of lost points may motivate them to review the instructions to ensure they have done their work correctly, a process which can improve their attention (Dennis) and metacognitive monitoring (Craig).

Table 1.

Common Errors in Following Instructions and Recommendations to Enhance the Probability of Instruction Following

Open in a separate window

1. Wright P, Wilcox P. Following instructions: an exploratory trisection of imperatives. In: Levelt WJM, FLores d' Arcais GB, eds. Studies in the Perception of Language. New York: Wiley;1978. [Google Scholar]

In: Levelt WJM, FLores d' Arcais GB, eds. Studies in the Perception of Language. New York: Wiley;1978. [Google Scholar]

2. Bergman-Nutley S, Klingberg T. Effect of working memory training on working memory, arithmetic and following instructions. Psychol Res. 2014;78(6):869-877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Yang T-x, Allen RJ, Gathercole SE. Examining the role of working memory resources in following spoken instructions. J Cogn Psychol. 2016;28(2):186-198. [Google Scholar]

4. Jaroslawska AJ, Gathercole SE, Allen RJ, Holmes J. Following instructions from working memory: why does action at encoding and recall help? Memory Cogn. 2016;44(8):1183-1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Jaroslawska AJ, Gathercole SE, Logie MR, Holmes J. Following instructions in a virtual school: does working memory play a role? Memory Cogn. 2016;44(4):580-589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Yang T. The role of working memory in following instructions. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing - Dissertation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

ProQuest Dissertations Publishing - Dissertation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

7. Kroger-Costa A, Abreu-Rodrigues J. Effects of historical and social variables on instruction following. Psychol Record. 2012;62(4):691-706. [Google Scholar]

8. Donadeli JM, Strapasson BA. Effects of monitoring and social peprimands on instruction-following in undergraduate students. Psychol Record. 2015;65(1):177-188. [Google Scholar]

9. Guerin B. Mere presence effects in humans: a review. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(1):38-77. [Google Scholar]

10. de Bruin ABH, van Gog T. Improving self-monitoring and self-regulation: from cognitive psychology to the classroom. Learn Instruct. 2012;22(4):245-252. [Google Scholar]

11. Bruin ABH, Dunlosky J, Cavalcanti RB. Monitoring and regulation of learning in medical education: the need for predictive cues. Med Educ. 2017;51(6):575-584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Baddeley A. Working memory. Current Biol. 2010;20(4):R136-R140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Cowan N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):197-223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24(1):87-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Van Merriënboer JJG, Sweller J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: design principles and strategies: cognitive load theory. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):85-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Young JQ, Van Merrienboer J, Durning S, Ten Cate O. Cognitive load theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach. 2014;36(5):371-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Allen RJ, Waterman AH. How does enactment affect the ability to follow instructions in working memory? Memory Cogn. 2015;43(3):555-561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Grech V. The application of the Mayer multimedia learning theory to medical PowerPoint slide show presentations. J Visual Comm Med. 2018;41(1):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Visual Comm Med. 2018;41(1):36-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning: evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. Am Psychol. 2008;63(8):760-769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Jha V, Brockbank S, Roberts T. A framework for understanding lapses in professionalism among medical students: applying the theory of planned behavior to fitness to practice cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1622-1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Burford B. Group processes in medical education: learning from social identity theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(2):143-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Sitzmann T, Ely K. A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: what we know and where we need to go. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(3):421-442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Flavell JH. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):906-911. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

24. Dunning D, Heath C, Suls JM. Flawed self-assessment: implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2004;5(3):69-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Kornell N, Bjork RA. The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonom Bull Rev. 2007;14(2):219-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Dunlosky J, Lipko AR. Metacomprehension: a brief history and how to improve its accuracy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(4):228-232. [Google Scholar]

27. Dunlosky J, Rawson KA. Overconfidence produces underachievement: inaccurate self evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learn Instruct. 2012;22(4):271-280. [Google Scholar]

28. Bjork RA, Dunlosky J, Kornell N. Self-regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Ann Rev Psychol. 2013;64(1):417-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Tanner KD. Promoting student metacognition. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11(2):113-120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM. Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM. Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Baddeley AD, Larsen JD. The phonological loop unmasked? a comment on the evidence for a "perceptual-gestural" alternative. Quart J Exp Psychol. 2007;60(4):497-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

What Is the Importance of Following Instructions?

Photo Courtesy: svetikd/Getty ImagesFollowing instructions can simplify tasks, increase effectiveness, eliminate confusion, and save time. Not to mention, it makes for a safer building process. But instruction-following also has some added benefits. For one, when instructions are properly followed, things work well — and people work well together. In fact, folks who follow instructions show that they are cooperative, intelligent, and dependable, while those who disregard instructions can cause obstacles — and safety concerns — down the line.

Failure to Follow Instructions

Humans learn to follow directions from an early age. It quickly becomes clear, even before we are conscious of it, that following instructions is important for safety. As we continue to grow, we also begin to learn that following instructions comes with many other benefits outside of keeping us safe.

Photo Courtesy: FreshSplash/Getty ImagesTypically, properly following instructions involves listening or reading carefully and asking questions when necessary. Those who follow instructions tend to find it easier to complete the task at hand. However, when a person fails to follow instructions, it can often lead to a lot of frustration and chaos, no matter the environment. Completing the task then becomes a lot more difficult and stressful.

Many people don’t realize it, but following instructions is an important life skill that can apply to almost every setting, from school and work to public transportation. For example, failure to follow instructions in an academic setting can negatively impact how well a person learns the subject matter, and, as a result, their grades may suffer. Another example? Failure to follow a recipe when cooking can cause you to end up eating something that doesn’t taste very good. And, finally, failure to follow instructions while driving can cause car accidents, which can lead to hefty fines, expensive car repairs, or injury.

Another example? Failure to follow a recipe when cooking can cause you to end up eating something that doesn’t taste very good. And, finally, failure to follow instructions while driving can cause car accidents, which can lead to hefty fines, expensive car repairs, or injury.

Following instructions at work can have different implications depending on the employment setting. In certain job situations, following instructions is a matter of safety (or, in some settings, it’s even a matter of life and death). In others, it can impact opportunities for career advancement. In virtually every work environment, following instructions has the potential to impact one’s day-to-day stress levels and overall quality of life.

Photo Courtesy: Morsa Images/Getty ImagesFollowing instructions can be a serious matter in terms of safety when it comes to the healthcare industry. Doctors, nurses, and administrative staff must follow instructions when dealing with patients to protect their health and the health of their patients. If a doctor does not follow the proper procedures during surgery, it could result in a patient’s injury or death. If a nurse does not follow instructions for administering medication, it can put a patient’s well-being in jeopardy as well.

If a doctor does not follow the proper procedures during surgery, it could result in a patient’s injury or death. If a nurse does not follow instructions for administering medication, it can put a patient’s well-being in jeopardy as well.

Moreover, safety on the job goes hand-in-hand with following instructions in other fields too. For example, factory and construction workers handle heavy machinery, and not following directions could put themselves or others in great danger. This includes the direct danger that can come with dealing with machines and equipment in general. It also involves making sure to put things together correctly so that the finished product does not endanger anyone. If a construction worker decided not to follow instructions properly when building a house, for example, it could end up being unstable, making it an eventual danger to the people living in it.

Even in settings that don’t deal directly with public health or safety, following instructions at work is important. In an office job, following instructions can significantly impact a person’s well-being. When someone does their work right the first time, everyone involved is happy and it creates a positive and productive work environment. Moreover, the employee is happy because they did their job well and likely have received positive feedback from their boss. On the other hand, if an employee does not follow instructions on a task, it can lead to a lot of stress for everyone involved, impacting a person’s mood and the company’s bottom line. If the issue of not following instructions becomes an ongoing one, one might face disciplinary actions, which, in turn, impact one’s quality of life.

In an office job, following instructions can significantly impact a person’s well-being. When someone does their work right the first time, everyone involved is happy and it creates a positive and productive work environment. Moreover, the employee is happy because they did their job well and likely have received positive feedback from their boss. On the other hand, if an employee does not follow instructions on a task, it can lead to a lot of stress for everyone involved, impacting a person’s mood and the company’s bottom line. If the issue of not following instructions becomes an ongoing one, one might face disciplinary actions, which, in turn, impact one’s quality of life.

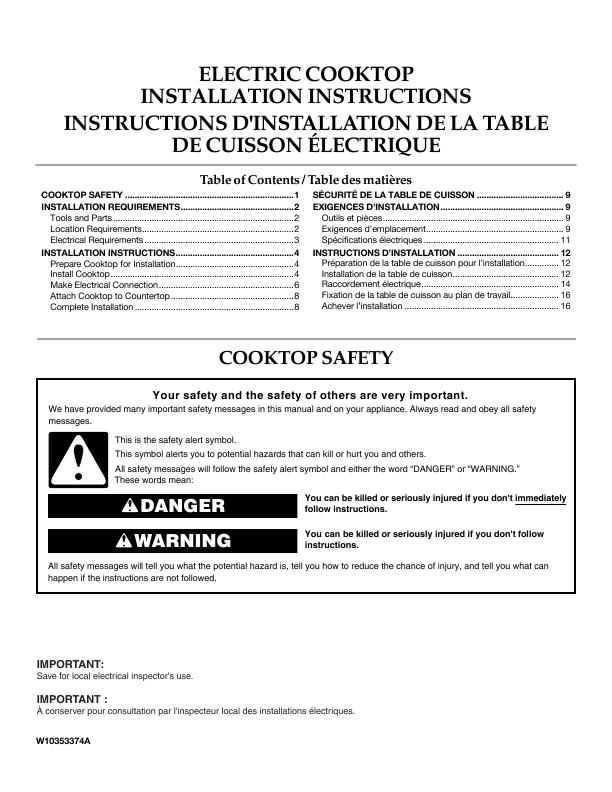

Following Manufacturer’s Instructions

Most products, no matter how simple they might seem to be, come with manufacturer’s instructions. If you happen to lose them, they are almost always available online and can be downloaded for free.

Photo Courtesy: Oscar Wong/Getty ImagesReading manufacturers’ instruction manuals helps you understand how to properly use a product and utilize all of its features. Without reading those guides, it becomes easy to miss important details about how something works and any safety protocols that are necessary to follow to avoid property damage or personal injury. They can not only help with setting up or installing the product, but also with troubleshooting any issues that might arise later on.

Without reading those guides, it becomes easy to miss important details about how something works and any safety protocols that are necessary to follow to avoid property damage or personal injury. They can not only help with setting up or installing the product, but also with troubleshooting any issues that might arise later on.

Product instructions also come with items that you have to assemble yourself, such as a bookshelf or a table. Trying to build an item like this without looking at the instructions often results in incorrect assembly. In this case, you’ll likely have to take it apart and start over again, causing a lot of frustration — not to mention, a loss of your valuable time.

MORE FROM REFERENCE.COM

Why it is important to follow instructions essay example

Following instructions is not just an important learning skill; it's a vital skill. From coloring the right frame in preschool to applying for Social Security, referrals are an important part of everyone's life. However, many seem to have trouble following them. Parents tell us that we toddlers shouldn't touch anything that could be potentially dangerous. If we don't heed these directions, we'll either get hurt or have "wait time" to learn our lesson. Throughout childhood and adolescence, instruction in following directions must be strengthened through the education of the individual. Many activities have been designed for this single purpose. nine0003

However, many seem to have trouble following them. Parents tell us that we toddlers shouldn't touch anything that could be potentially dangerous. If we don't heed these directions, we'll either get hurt or have "wait time" to learn our lesson. Throughout childhood and adolescence, instruction in following directions must be strengthened through the education of the individual. Many activities have been designed for this single purpose. nine0003

Standardized written exams also test this skill, as many students fail each year due to "not following directions." In the traditional classroom, teachers have developed non-traditional tools to demonstrate the importance of following directions. Some teachers have students follow a recipe for a favorite, age-appropriate food, but intentionally leave out an important ingredient. Others used a simple worksheet, numbered 1 to 10, with task #1 asking students to read all the instructions before doing anything. The result of this lesson is task #10, which will simply say: Now that you have read all the instructions, please go back and just complete #1 and #2. read everything first. nine0003

read everything first. nine0003

The steps above can be duplicated by homeschooling parents teaching a lesson to young people. At Time4Writing, our goal is not only to help students improve their writing skills; We also want to highlight the importance of the following areas. At the beginning of each course, there are a series of guidelines that students should read before beginning.

They should copy and paste their assignment instructions into their individual text boxes so they can see them in full as they work. Students are expected to follow these directions as closely as possible. So, perhaps in the coming years, students who take Time4Writing courses won't need to reapply for driver's licenses, turn down insurance forms, or spit out tax returns because they were filled out incorrectly. They will remember that online writing course that showed them how to write and how to follow instructions. nine0003

Myths about whey protein for women

10/30/2020 No Comments

Men have ruled the fitness industry for a very long time. It's no surprise that women are head-to-head with men in the fitness industry. They are also looking for the perfect body,

It's no surprise that women are head-to-head with men in the fitness industry. They are also looking for the perfect body,

Read more »

The problem of self-identification in the film “Virginity”

10/30/2020 No Comments

In Girlhood (2014), Mariem (Karija Toure) is faced with the question of self-identification. Worried about poor school performance and an abusive older brother, Marie joins a gang of

Read more »

Homosexuality and modern society

10/30/2020 No comments

Homosexuality is nothing but sexual attraction to a person of the same sex. In most parts of the world, this is considered taboo. Different societies react differently to

Read more »

Why do some children have difficulty completing tasks?

We bring to your attention one of the successful strategies for teaching a child (and not only) to follow instructions:

I am a mother of two daughters. My youngest, Anyuta, was restless and had attention problems, which prevented her from completing my tasks. When she was about 7 years old, she often refused to do what I asked.

My youngest, Anyuta, was restless and had attention problems, which prevented her from completing my tasks. When she was about 7 years old, she often refused to do what I asked.

At school Anya was nice, accommodating and helpful. But at home, my seven-year-old became stubborn and cocky when asked to do simple housework. Requests to put away their toys and brush their teeth were ignored or carried out with conditions or tears.

My husband and I tried everything we could think of:

Logic: "Anna, if you don't put the Lego away, you might lose the pieces and then you won't be able to play any more."

Negotiation: “Okay, you can watch TV for another 10 minutes and then you can leave.”

Threats: “I count to five, if you don't get away, I'll take your Lego. Five... four... three...”

Typical result: an epic hour-long fight with tears and screams.

What I regret - what I didn't know before: I need to give simple commands

My husband and I described the vicious circle we found ourselves in to a psychologist. The doctor explained that we had to give simple commands - one-step or two-step. An assignment with more than two steps—for example, “Go to the nursery, put away toys, brush your teeth, and pick up clothes from the floor”—may be too difficult for a child to remember and follow. nine0003

The doctor explained that we had to give simple commands - one-step or two-step. An assignment with more than two steps—for example, “Go to the nursery, put away toys, brush your teeth, and pick up clothes from the floor”—may be too difficult for a child to remember and follow. nine0003

We also had to stop negotiating, begging and threatening.

The psychologist gave us a specific set of instructions, which were: Look your child straight in the eyes, calmly say her name, pause, give the two-step task, and end with "now." "Anna, go to the bathroom, brush your teeth, now."

Further, according to the instructions, we had to wait 15 - 18 seconds and stay 1-1.5 meters from Anya. If she followed instructions, we should praise her for her obedience. If she did not complete the task, we should calmly repeat the task. nine0003

That same night I tried: “Anna, go to the bathroom, brush your teeth, now.” I mentally counted to 18, forcing myself to ignore everything she said or did in between.