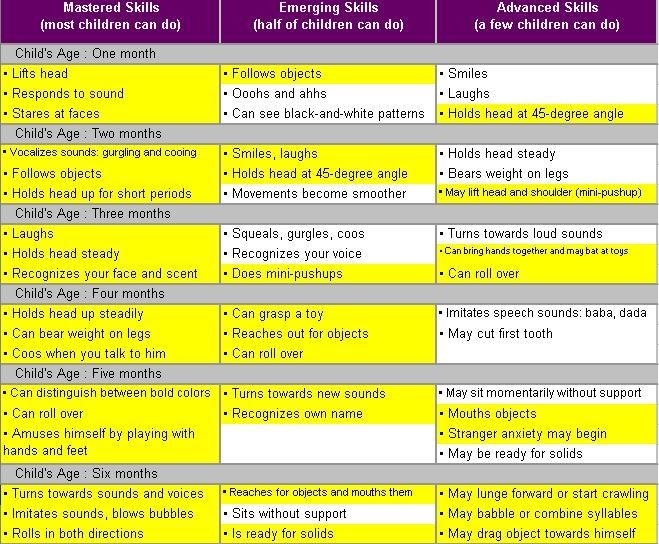

Goldilocks original story

Goldilocks and the Three Bears

seek 00.00.00 00.00.00 loading- Download

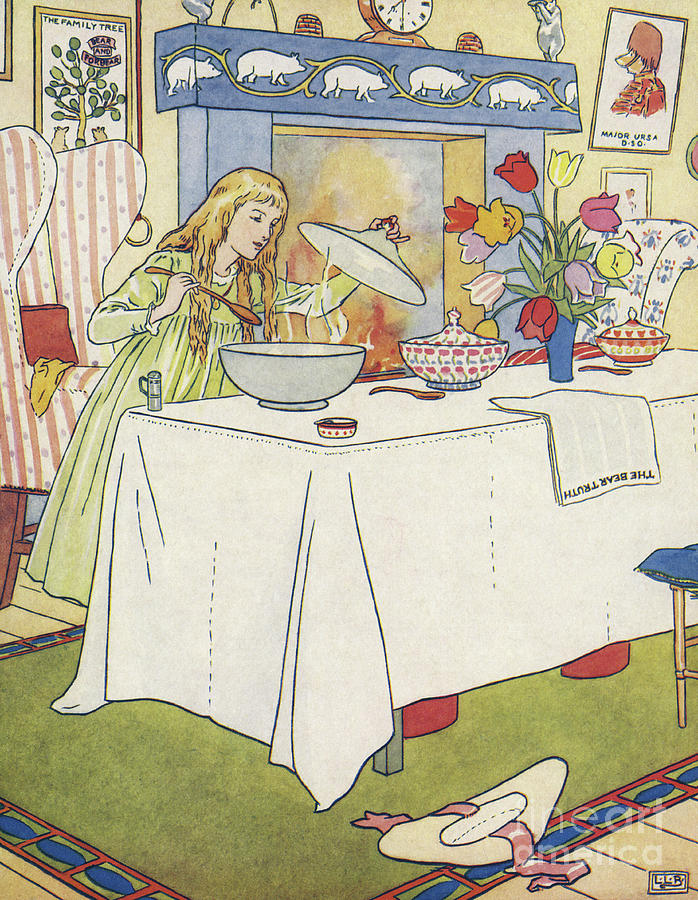

Picture by Bertie - a retake of the classic illustration by Walter Crane.

Duration 3:15.

Based on the Charming version by the Victorian writer Andrew Lang.

Read by Natasha.

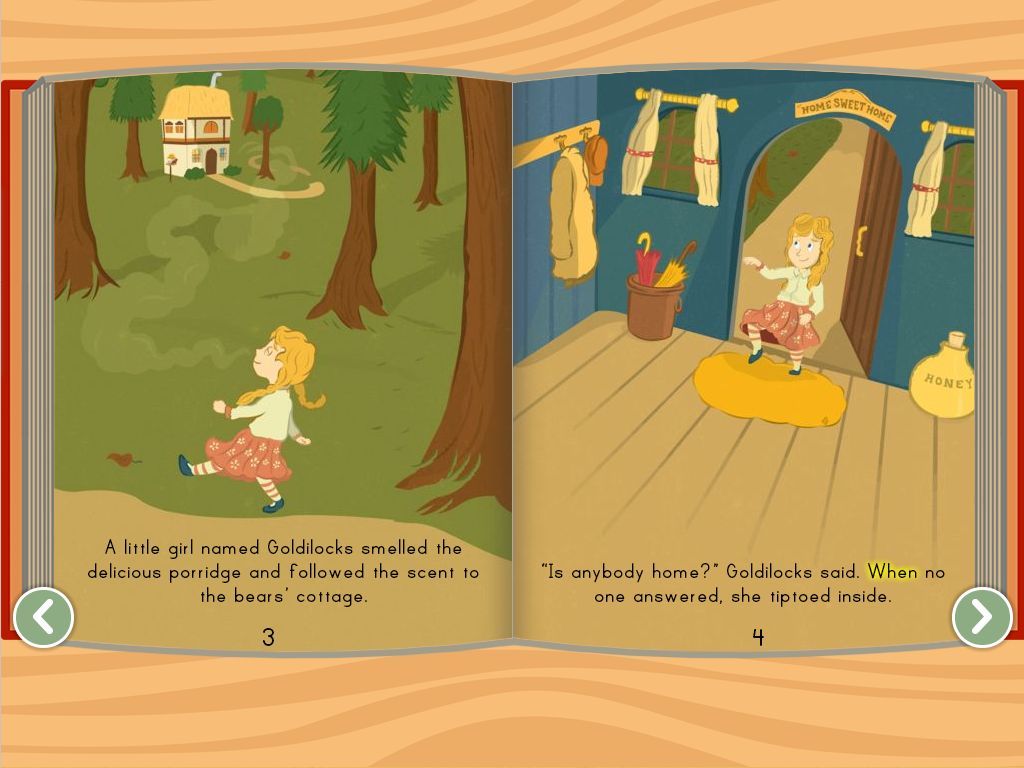

Once upon a time there were three bears, who lived together in a house of their own in a wood. One of them was a little, small wee bear; one was a middle-sized bear, and the other was a great, huge bear.

One day, after they had made porridge for their breakfast, they walked out into the wood while the porridge was cooling. And while they were walking, a little girl came into the house. This little girl had golden curls that tumbled down her back to her waist, and everyone called her by Goldilocks.

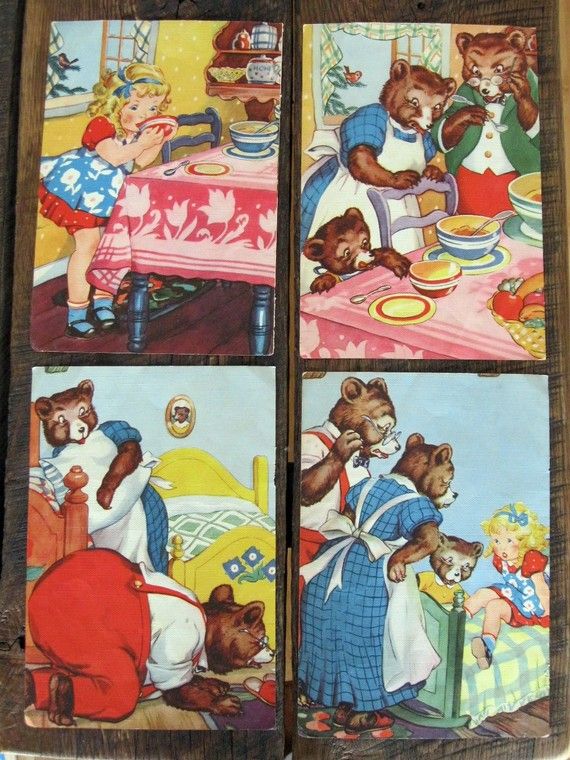

Goldilocks went inside. First she tasted the porridge of the great, huge bear, and that was far too hot for her. And then she tasted the porridge of the middle bear, and that was too cold for her. And then she went to the porridge of the little, small wee bear, and tasted that. And that was neither too hot nor too cold, but just right; and she liked it so well, that she ate it all up.

Then Goldilocks went upstairs into the bed chamber and first she lay down upon the bed of the great, huge bear, and then she lay down upon the bed of the middle bear and finally she lay down upon the bed of the little, small wee bear, and that was just right. So she covered herself up comfortably, and lay there until she fell fast asleep.

By this time, the three bears thought their porridge would be cool enough, so they came home to breakfast.

“SOMEBODY HAS BEEN AT MY PORRIDGE!” said the great huge bear, in his great huge voice.

“Somebody has been at my porridge!” said the middle bear, in his middle voice.

Then the little, small wee bear looked at his, and there was the spoon in the porridge pot, but the porridge was all gone.

“Somebody has been at my porridge, and has eaten it all up!” said the little, small wee bear, in his little, small wee voice.

Then the three bears went upstairs into their bedroom.

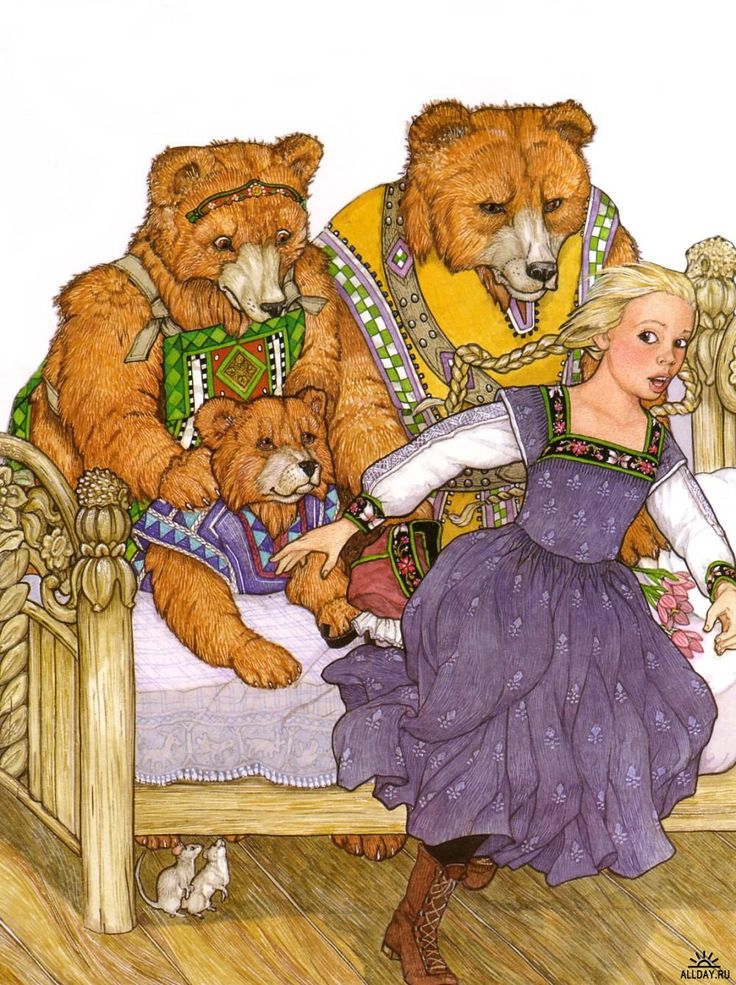

“SOMEBODY HAS BEEN LYING IN MY BED!” said the great, huge bear, in his great, rough, gruff voice.

“Somebody has been lying in my bed!” said the middle bear, in his middle voice.

And when the little, small, wee bear came to look at his bed, upon the pillow there was a pool of golden curls, and the angelic face of a little girl snoring away, fast asleep.

“Somebody has been lying in my bed, and here she is!” Said the little, small wee bear, in his little, small wee voice.

Goldilocks jumped off the bed and ran downstairs, out of the door and down the garden path. She ran and she ran until she reached the house of her grandmama. When she told her grandmama about the house of the three bears who lived in the wood, her granny said: “My my, what a wild imagination you have, child!”

(Updated with shorter version September, 13, 2016).

She Doesn’t Always Get Away: Goldilocks and the Three Bears

It’s such a kind, cuddly story—three cute bears with a rather alarming obsession with porridge and taking long healthy walks in the woods (really, bears, is this any example to set to small children), one small golden haired girl who is just

hungry and tired and doesn’t want porridge that burns her mouth—a perfectly understandable feeling, really.

Or at least, it’s a kind cuddly story now.

In the earliest written version, the bears set Goldilocks on fire.

That version was written down in 1831 by Eleanor Mure, someone we know little of besides the name. The granddaughter of a baron and daughter of a barrister, she was apparently born around 1799, never married, was at some point taught how to use watercolors, and died in 1886. And that’s about it. We can, however, guess that she was fond of fairy tales and bears—and very fond of a young nephew, Horace Broke. Fond enough to write a poem about the Three Bears and inscribe it in his very own handcrafted book for his fourth birthday in 1831.

It must have taken her at least a few weeks if not more to put the book together, both to compose the poem and paint the watercolor illustrations of the three bears and St. Paul’s Cathedral, stunningly free of any surrounding buildings. In her version, all animals can talk. Three bears (in Mure’s watercolors, all about the same size, although the text claims that the third bear is “little”) take advantage of this speaking ability to buy a nice house in the neighborhood, already furnished.

Almost immediately, they run into social trouble when they decide not to receive one of their neighbors, an old lady. Her immediate response is straight from Jane Austen and other books of manners and social interactions: she calls the bears “impertinent” and to ask exactly how they can justify giving themselves airs. Her next response, however, is not exactly something that Jane Austen would applaud: after getting told to go away, she decides to walk into the house and explore it—an exploration that includes drinking out of their three cups of milk, trying their three chairs (and breaking one) and trying out their three beds (breaking one of those as well). The infuriated bears, after finding the milk, the chairs and the beds, decide to take their revenge—first throwing her into a fire and then into water, before finally throwing her on top of the steeple of St. Paul’s Cathedral and leaving her there.

The poetry is more than a bit rough, as is the language—I have a bit of difficulty thinking that anyone even in 1831 would casually drop “Adzooks!” into a sentence, although I suppose if you’re going to use “Adzooks” at all (and Microsoft Word’s spell checker, for one, would prefer that you didn’t) it might as well be in a poem about bears. Her nephew, at least, treasured the book enough to keep it until his death in 1909, when it was purchased, along with the rest of his library, by librarian Edgar Osborne, who in turn donated the collection to the Toronto Public Library in 1949, which publicized the find in 1951, and in 2010, very kindly published a pdf facsimile online which allows all of us to see Mure’s little watercolors with the three bears.

Her nephew, at least, treasured the book enough to keep it until his death in 1909, when it was purchased, along with the rest of his library, by librarian Edgar Osborne, who in turn donated the collection to the Toronto Public Library in 1949, which publicized the find in 1951, and in 2010, very kindly published a pdf facsimile online which allows all of us to see Mure’s little watercolors with the three bears.

Mure’s poem, however, apparently failed to circulate outside of her immediate family, or perhaps even her nephew, possibly because of the “Adzooks!” It was left to poet Robert Southey to popularize the story in print form, in his 1837 collection of writings, The Doctor.

Southey is probably best known these days as a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (the two men married two sisters). In his own time, Southey was initially considered a radical—though he was also the same radical who kindly advised Charlotte Bronte that “Literature is not the business of a woman’s life. ” To be somewhat fair, Southey may have been thinking of his own career: he, too, lacked the funds to focus completely on poetry, needing to support himself through nonfiction work after nonfiction work. Eventually, he accepted a government pension, accepting that he did not have a large enough estate or writing income to live on. He also moved away from his earlier radicalism—and some of this friends—though he continued to protest living conditions in various slums and the growing use of child labor in the earlier part of the 19th century.

” To be somewhat fair, Southey may have been thinking of his own career: he, too, lacked the funds to focus completely on poetry, needing to support himself through nonfiction work after nonfiction work. Eventually, he accepted a government pension, accepting that he did not have a large enough estate or writing income to live on. He also moved away from his earlier radicalism—and some of this friends—though he continued to protest living conditions in various slums and the growing use of child labor in the earlier part of the 19th century.

His prose version of “The Three Bears” was published after he had accepted that government pension and joined the Tory Party. In his version, the bears live not in a lovely, furnished country mansion, but in a house in the woods—more or less where bears might be expected to be found. After finding that their porridge is too hot, they head out for a nice walk in the woods. At this point, an old woman finds their house, heads in, and starts helping herself to the porridge, chairs and the beds.

It’s a longer, more elaborate version than either Mure’s poem or the many picture books that followed him, thanks to the many details Southey included about the chair cushions and the old lady—bits left out of most current versions. What did endure was something that doesn’t appear in Mure’s version: the ongoing repetition of “SOMEBODY’S BEEN EATING MY PORRIDGE,” and “SOMEBODY’S BEEN SITTING IN MY CHAIR.” Whether Southey’s original invention, or something taken from the earlier oral version that inspired both Mure and Southey, those repetitive sentences—perfect for reciting in different silly voices—endured.

Southey’s bears are just a little bit less civilized than Mure’s bears—in Southey’s words, “a little rough or so,” since they are bears. As his old woman: described as an impudent, bad old woman, she uses rough language (Southey, knowing the story would be read to or by children, does not elaborate) and doesn’t even try to get an invitation first. But both stories can be read as reactions to changing social conditions in England and France. Mure presents her story as a clash between established residents and new renters who—understandably—demand to be treated with the same respect as the older, established residents, in a mirror of the many cases of new merchant money investing in or renting older, established homes. Southey shows his growing fears of unemployed, desperate strangers breaking into quiet homes, searching for food and a place to rest. His story ends with the suggestion that the old woman either died alone in the woods, or ended up getting arrested for vagrancy.

Mure presents her story as a clash between established residents and new renters who—understandably—demand to be treated with the same respect as the older, established residents, in a mirror of the many cases of new merchant money investing in or renting older, established homes. Southey shows his growing fears of unemployed, desperate strangers breaking into quiet homes, searching for food and a place to rest. His story ends with the suggestion that the old woman either died alone in the woods, or ended up getting arrested for vagrancy.

Southey’s story was later turned into verse by a certain G.N. (credited as George Nicol in some sources) on the basis that, as he said:

But fearing in your book it might

Escape some little people’s sight

I did not that one should lose

What will them all so much amuse,

As you might be gathering from this little excerpt, the verse was not particularly profound, or good; the book, based on the version digitized by Google, also contained numerous printing errors. (The digitized Google version does preserve the changes in font size used for the bears’ dialogue.) The illustrations, however, including an early one showing the bears happily smoking and wearing delightful little reading glasses, were wonderful—despite the suggestion that the Three Bears were not exactly great at housekeeping. (Well, to be fair, they were bears.)

(The digitized Google version does preserve the changes in font size used for the bears’ dialogue.) The illustrations, however, including an early one showing the bears happily smoking and wearing delightful little reading glasses, were wonderful—despite the suggestion that the Three Bears were not exactly great at housekeeping. (Well, to be fair, they were bears.)

To be fair, some of the poetic issues stem from Victorian reticence:

Somebody in my chair has been!”

The middle Bear exclaim’d;

Seeing the cushion dented in

By what may not be named.

(Later Victorians, I should note, thought even this—and the verse that follows, which, I should warn you, suggests the human bottom – was far too much, ordering writers to delete Southey’s similar reference and anything that so much as implied a reference to that part of the human or bear anatomy. Even these days, the exact method that Goldilocks uses to dent the chair and later break the little bear’s chair are left discreetly unmentioned. )

)

Others stem from a seeming lack of vocabulary:

She burn’d her mouth, at which half mad

she said a naughty word;

a naughty word it was and bad

As ever could be heard.

Joseph Cundall, for one, was unimpressed, deciding to return to Southey’s prose version of the tale for his 1849 collection, Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. Cundall did, however, make one critical and lasting change to the tale: he changed Southey’s intruder from an elderly lady to a young girl called Silver-Hair. Cundall felt that fairy tales had enough old women, and not enough young girls; his introduction also suggests that he may have heard another oral version of the tale where the protagonist was named Silver Hair. Shortly after publishing this version, Cundall went bankrupt, and abandoned both children’s literature and printing for the more lucrative (for him) profession of photography.

The bankruptcy did not prevent other Victorian children’s writers from seizing his idea and using it in their own versions of the Three Bears, making other alterations along the way. Slowly, the bears turned into a Bear Family, with a Papa, Mama and Baby Bear (in the Mure, Southey, G.N. and Cundall versions, the bears are all male). The intruder changed names from Silver Hair to Golden Hair to Silver Locks to, eventually, Goldilocks. But in all of these versions, she remained a girl, often a very young one indeed, and in some cases, even turned into the tired, hungry protagonist of the tale—a girl in danger of getting eaten by bears.

Slowly, the bears turned into a Bear Family, with a Papa, Mama and Baby Bear (in the Mure, Southey, G.N. and Cundall versions, the bears are all male). The intruder changed names from Silver Hair to Golden Hair to Silver Locks to, eventually, Goldilocks. But in all of these versions, she remained a girl, often a very young one indeed, and in some cases, even turned into the tired, hungry protagonist of the tale—a girl in danger of getting eaten by bears.

I suspect, however, that like me, many small children felt more sympathy for the small bear. I mean, the girl ate his ENTIRE BREAKFAST AND BROKE HIS CHAIR. As a small child with a younger brother who was known for occasionally CHEWING MY TOYS, I completely understood Baby Bear’s howls of outrage here. I’m just saying.

The story was popular enough to spawn multiple picture books throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which in turn led to some authors taking a rather hard look at Goldilocks. (Like me, many of these authors were inclined to be on the side of Baby Bear. ) Many of the versions took elaborate liberties with the story—as in my personal recent favorite, Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs, by Mo Willems, recommended to me by an excited four year old. Not only does it change the traditional porridge to chocolate pudding, which frankly makes far more sense for breakfast, it also, as the title might have warned, has dinosaurs, though I should warn my adult readers that alas, no, the dinosaurs do not eat Goldilocks, which may be a disappointment to many.

) Many of the versions took elaborate liberties with the story—as in my personal recent favorite, Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs, by Mo Willems, recommended to me by an excited four year old. Not only does it change the traditional porridge to chocolate pudding, which frankly makes far more sense for breakfast, it also, as the title might have warned, has dinosaurs, though I should warn my adult readers that alas, no, the dinosaurs do not eat Goldilocks, which may be a disappointment to many.

For the most part, the illustrations in the picture books range from adequate to marvelous—a far step above the amateur watercolors so carefully created by Mure in 1837. But the story survived, I think, not because of the illustrations, but because when properly told by a teller who is willing to do different voices for all three bears, it’s not just exciting but HILARIOUS, especially when you are three. It was the start, for me, of a small obsession with bears.

But I must admit, as comforting as it is on some level to know that in most versions, Goldilocks does get safely away (after all, in the privacy of this post, I must admit that my brother was not the only child who broke things in our house, and it’s kinda nice to know that breaking a chair won’t immediately lead to getting eaten by bears) it’s equally comforting to know that in at least one earlier version, she didn’t.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

citation

Goldilocks and the Three Bears: aneitis — LiveJournal

"As Carl Levi-Strauss wrote: 'Let's start with the facts'"Let's follow this motto.

In his article, Leonid Chernov writes: "The fairy tale "Three Bears" today is perceived and presented as a folk tale, but meanwhile, it was invented by Tolstoy and is purely his author's work. Tolstoy's talent and the irony of time do their job in relation to this particular fairy tale - this tale is perceived as a folk tale" .

He is right about one thing - the fairy tale is really perceived as a folk tale. True, Tolstoy's talent has nothing to do with it, because it is popular. After looking through the collections of "Russian Folk Tales" by A. N. Afanasyev and not finding anything similar to the plot of "The Three Bears", Chernov, with his characteristic courage, comes to the conclusion: "there must be a primary source, and since it was not possible to find it, we believe, that it simply does not exist, and we consider this tale to be the work of Tolstoy" .

He believes so in vain - just in those blessed times of a careless attitude towards copyright, Tolstoy did not consider it necessary to mention the original source, and how could one guess that one should look for it not in Russian folklore, but in English. Now Wikipedia will tell anyone who is interested that this is a popular English fairy tale, well known since at least the beginning of 19centuries. However, in the pre-Internet era, it was probably not so easy to find out about this, and even now few people are interested, and therefore few people know. At best, they will remember that Tolstoy wrote it, but usually they continue to consider it Russian folk.

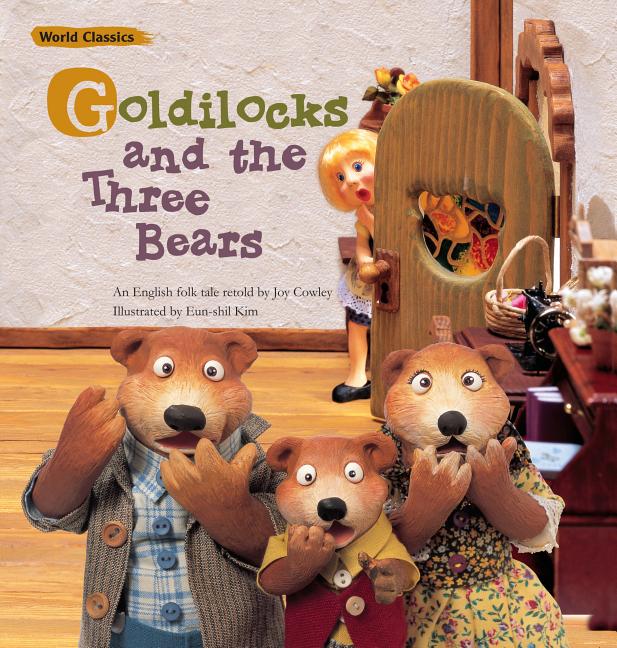

I also thought so and was quite surprised by this discovery when G. Spirin's book "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" fell into my hands:

The Three Bears is really an English fairy tale? - no one knew, and everyone was also very surprised)

But unexpectedly, the overseas origin is not the most surprising thing in the history of this tale. She is amazing in itself, if you look closely, here Leonid Chernov is right again, and how right.

She is amazing in itself, if you look closely, here Leonid Chernov is right again, and how right.

This fairy tale really stands out from the series of fairy tales about a girl who ended up in the forest, and there are many such: about Masha and the bear, about Snegurushka, about Snow White, about the dead princess, about Morozko, etc.

Firstly, the heroine impersonal. Nothing is said about her, she doesn't even have a name. It is not known how she got into the forest. That is, it is mentioned that she “left home for the forest” and got lost there, but we don’t know why she left - did her evil stepmother kick her out, did she run away herself, or simply went into the forest “for mushrooms, for berries”, but Why was she alone then? Such an ontogenetic gap is completely uncharacteristic of fairy tales - some description of the initial situation and motivation for the actions of the heroine is always given.

Secondly, having got into a strange house in a dense forest, the girl again behaves completely uncharacteristically. That is, it is not typical for a positive heroine, who in such a situation must show all her best sides: be modest, show housekeeping and care - tidy up, cook dinner (and not eat someone else's) and wait for the owners to return. The girl in The Three Bears behaves exactly like a "bad sister", whose repulsive behavior in such tales is only intended to shade the virtues of the main character. But the bad sister at the end of the tale will certainly be punished.

That is, it is not typical for a positive heroine, who in such a situation must show all her best sides: be modest, show housekeeping and care - tidy up, cook dinner (and not eat someone else's) and wait for the owners to return. The girl in The Three Bears behaves exactly like a "bad sister", whose repulsive behavior in such tales is only intended to shade the virtues of the main character. But the bad sister at the end of the tale will certainly be punished.

However, thirdly, there is no punishment for wrong behavior at the end of the tale. The girl, who has pissed on a cute bear family for nothing, just jumps out the window and runs away - "and the bears did not catch up with her." It is not clear whether the girl is a positive heroine or a negative one.

It is pointless to look for answers to all these questions from Tolstoy, since he only made a slightly adapted translation without making any significant changes, so you have to turn to the original version. To begin with, to the same Russian translation of an English fairy tale made by G. Spirin (you can see it in full here).

Spirin (you can see it in full here).

And then the first surprise awaited me. The tale of Goldilocks and the three bears does not begin with Goldilocks at all, but with bears!

x

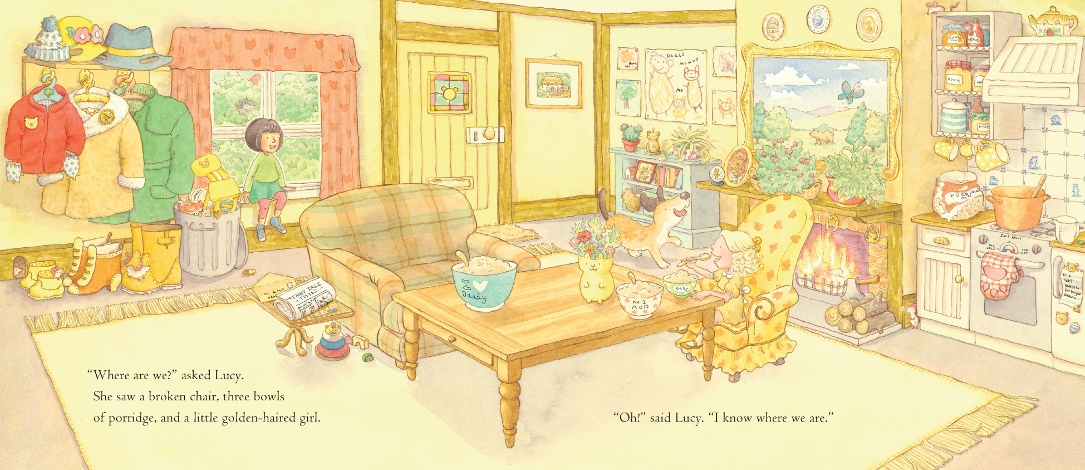

And this is not a trifle - after all, in this case, according to the logic of a fairy tale, the main characters are bears, and not a girl. And the initial situation turns out to be in place - it describes the life of bears:

True, no clear explanations of the reason for the appearance of Goldilocks in the forest are given here either: she invades the narrative just as unexpectedly as in the house of bears:

A little girl walks alone in the forest, wanders to an unfamiliar house and climbs in the window! Where are her parents and what are they thinking? This question remains as yet unanswered.

On the other hand, it becomes clear that the same initial situation is actually preserved in Tolstoy's fairy tale, albeit in a truncated form. He simply removed her from her rightful place at the beginning of the tale, which is why she was no longer perceived by readers as the original one. Why did he do it? Obviously, in order to make the main character a girl, not bears. And this is logical: it is the girl who is the only active character here. Bears, in the English version, formally occupying the place of the main characters, behave passively throughout the story: they are only indignant, discovering new traces of intrusion into their home, and only the most injured baby bear cub tries to bite the girl, who, however, manages to escape with impunity from angry bears.

Why did he do it? Obviously, in order to make the main character a girl, not bears. And this is logical: it is the girl who is the only active character here. Bears, in the English version, formally occupying the place of the main characters, behave passively throughout the story: they are only indignant, discovering new traces of intrusion into their home, and only the most injured baby bear cub tries to bite the girl, who, however, manages to escape with impunity from angry bears.

A strange picture emerges: the adults in this tale are completely passive and helpless. The girl's absent parents neglect her upbringing and safety concerns, leaving her free to roam where she pleases, behave inappropriately and get herself into dangerous situations; the bear cub's parents do not try to protect him: the baby, who has experienced a real shock - his dinner is eaten, his high chair is broken, his bed is occupied by an alien - is forced to independently defend his place in his home. Children do not receive instructions, support, or evaluation of their behavior from anyone. Finally, the girl disappears into the forest as mysteriously as she appeared: it is not known whether she got home (and whether she has one at all) and whether she (and the child-listener with her) made the conclusion from what happened that it is possible encroach on someone else's property with impunity and you won't get anything for it, the main thing is to run away in time. However, it is quite possible that a prosperous child will associate himself more with a bear cub who has parents, a house, a blue cup, a high chair with a blue pillow and his own bed, than with a homeless girl who has arisen out of nowhere and violates all established rules, and in this case he will be left wondering why her misbehavior had no consequences.

Finally, the girl disappears into the forest as mysteriously as she appeared: it is not known whether she got home (and whether she has one at all) and whether she (and the child-listener with her) made the conclusion from what happened that it is possible encroach on someone else's property with impunity and you won't get anything for it, the main thing is to run away in time. However, it is quite possible that a prosperous child will associate himself more with a bear cub who has parents, a house, a blue cup, a high chair with a blue pillow and his own bed, than with a homeless girl who has arisen out of nowhere and violates all established rules, and in this case he will be left wondering why her misbehavior had no consequences.

The result of the tale is so unsatisfactory that parents and educators feel obliged to complete the "correct" beginning and end - or at least conduct an educational conversation after reading to make sure that the child does not draw undesirable conclusions. This often manifests itself when transferring a fairy tale to the screen. In our 1958 cartoon, the girl gets a name and a grandmother, who gives her granddaughter the necessary instructions at the beginning and the necessary teachings at the end:

This often manifests itself when transferring a fairy tale to the screen. In our 1958 cartoon, the girl gets a name and a grandmother, who gives her granddaughter the necessary instructions at the beginning and the necessary teachings at the end:

However, we have another, not so straightforward version 1984 years old - in it the original interpretation is achieved by other methods:

In numerous English cartoons, it is always emphasized at the end that Goldilocks was very scared and never went into the forest again.

However, it is worth mentioning that not always everything ended so happily for Goldilocks: in some early versions, the bears ate her. However, now the girl simply explains that she was hungry and tired, repents and asks for forgiveness, and the softened bears send the bear cub to accompany her home.

In one variation, Goldilocks and the bear cub then play together and become friends.

In another, mom is shown pouring porridge out of her bowl for a baby bear, while dad is fixing his chair.

The girl has a house and a mother who reminds her that she should not go into the forest (or at least go far), and it is noteworthy that often the story begins with a show not of the bear's house, but of Goldilocks, that is, she moves to her the rightful place of the main character.

It remains unclear why the original story exists in such an "unfinished" form, clearly in need of improvement.

Leonid Chernov, who considers Tolstoy the author of the tale, believes that Tolstoy “trimmed” it deliberately, prompting parents to invent the missing elements on their own. I don’t know why Tolstoy would have this, who even included multi-page explanations and teachings in his works for adults, not trusting the reader to draw conclusions on his own, but we already know that Tolstoy only translated a folk tale (and it’s rather surprising that he didn’t add anything from myself). And for folklore, such semi-finished products are completely uncharacteristic.

I had to dig further - the explanation could be found in older versions of the tale, because sometimes the story undergoes significant changes over time.

And then a second surprise awaited.

What really happened in the original fairy tales

Pinocchio

In the original version by Carlo Collodi, published in 1883, there were no fairies or miracles at all. The poor wooden boy at the very beginning of the book fell asleep by the fire and his legs were burned, and before that he managed to kill a talking cricket. Yes, yes, the cutest creature that we liked in cartoons. After all this, Pinocchio is turned into a donkey, tied to a stone and thrown off a cliff ... but his misadventures do not end there. While he was a donkey, they bought him at the fair and they wanted to make a drum out of him, then they almost put him in prison, and generally mocked Pinocchio as best they could.

What was the instructive part of the original fairy tale difficult to understand. Don't cut boys out of wood, will it end badly? Be that as it may, the modern version with Karabas Barabas or the wooden boy's longing to turn into a real one sounds just magical when you know the real story.

Snow White

The gnomes in the original version of the fairy tale didn’t even pass by, but instead of a stepmother, Snow White had a real mother, who nevertheless sent the huntsman to kill her own daughter in the forest and bring back only her liver, lungs and heart to pickle and eat. According to some versions - for eternal beauty and youth. In the story of the Brothers Grimm in 1812, the cruel mother was nevertheless punished: she came to the wedding of Snow White and danced in red-hot iron shoes until she fell dead.

Little Red Riding Hood

In the original story from which Perrault created the legendary fairy tale (and this was already in 1697), the wolf was not the charming Johnny Depp, as in the new film, but a werewolf. After eating his grandmother, he invites the little red riding hood not to discuss the size of his ears and eyes, but to immediately undress and go to bed, throwing clothes into the fire. Further versions diverge - in Perrault's fairy tale, the wolf eats Little Red Riding Hood in bed, in the original story the girl says she wants to go to the toilet and she manages to escape. The latter version sounds quite positive, if we recall that in the Brothers Grimm version of 1812, the girl and grandmother are freed by cutting the belly of the wolf.

The latter version sounds quite positive, if we recall that in the Brothers Grimm version of 1812, the girl and grandmother are freed by cutting the belly of the wolf.

Cinderella

In the retelling of the Brothers Grimm, namely in the 7th edition of 1857, the fairy tale sounds much more sinister than that of Charles Perrault, who created the original story 200 years after that. By the way, it is this eerie version that we see in the new film "The further into the forest ...". Why Hollywood chose this one of all the good retellings of the fairy tale is not clear, but the fact remains: according to the Brothers Grimm, the beautiful and evil sisters of Cinderella wanted to marry the prince at any cost and in desperation one cut off her finger, and the other cut off her heel, so that her leg fit in a shoe. Pigeons, friends of Cinderella, notice that the shoes are filled with blood and, having discovered the sisters' deceit, peck out their eyes. Well, the prince at this time realizes that Cinderella is his only one.

The Sleeping Beauty

In the collection of fairy tales of 1634 by the storyteller Giambattista Basile, who was one of the first to write down fairy tales that people told from generation to generation, and which were then copied by the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault, the tale of the sleeping beauty is also looks different. It is based on the story "The Sun, the Moon and the waist (name)" by Giambattista Basile. Princess Thalia falls into a deep sleep, and the prince finds her, but does not kiss her, but, fascinated by her beauty, rapes her. She becomes pregnant and gives birth to twins. One of them begins to suck his finger instead of his chest in search of food and sucks out a fragment of an enchanted needle. The princess wakes up in shock, it turns out that she is already a mother. The king who raped her, having learned about the miraculous resurrection of the princess, quickly kills his former wife and remains with his new lover. This is how it all gets resolved.

Pied Piper

The most famous version of the Pied Piper tale today, in a nutshell, is this:

The city of Hameln was invaded by hordes of rats. And then a man with a pipe appeared and offered to rid the city of rodents. The people of Hamelin agreed to pay a generous reward, and the rat-catcher fulfilled his end of the bargain. When it came to payment - the townspeople, as they say, "threw" their savior. And then the Pied Piper decided to rid the city of children too!

In more modern versions, the Pied Piper lured the children into a cave away from the city, and as soon as the greedy townspeople paid off, he sent everyone home. In the original, the Pied Piper took the children into the river, and they drowned (except for one cripple, who fell behind everyone else).

The Little Mermaid

Disney's film about The Little Mermaid ends with Ariel and Eric's magnificent wedding, where not only people, but also sea inhabitants have fun. But in the first version, written by Hans Christian Andersen, the prince marries a completely different princess, and the grief-stricken Mermaid is offered a knife, which she must plunge into the heart of the prince in order to be saved. Instead, the poor child jumps into the sea and dies, turning into sea foam.

But in the first version, written by Hans Christian Andersen, the prince marries a completely different princess, and the grief-stricken Mermaid is offered a knife, which she must plunge into the heart of the prince in order to be saved. Instead, the poor child jumps into the sea and dies, turning into sea foam.

Then Andersen slightly softened the ending, and the Little Mermaid became no longer sea foam, but a “daughter of the air”, who is waiting for her turn to go to heaven. But it was still a very sad ending.

Initially, the little mermaid had to die in order for the prince and his kingdom to prosper. This is such a sacrifice. As a result, the mermaid soul becomes free for good deeds. I wonder what happens in the end with the soul of the prince. He certainly acted dishonorably.

Rapunzel

The Brothers Grimm put together a story from pieces of dark deeds, and it took the Disney producers a lot of work to remake it. In fact, the story of Rapunzel's flight ends with her jumping from the tower, trying to commit suicide, but survives. Then she goes blind and already blind is looking for the prince. Finds or not, is not said. Later, the prince finds Rapunzel, and she lives in the forest with two children. Whose - also remains a mystery, apparently illegitimate, from the prince. Yeah, not really a childish legend.

Then she goes blind and already blind is looking for the prince. Finds or not, is not said. Later, the prince finds Rapunzel, and she lives in the forest with two children. Whose - also remains a mystery, apparently illegitimate, from the prince. Yeah, not really a childish legend.

beauty and the beast

What do you think? There is a catch here too. The Disney story is based on a French fairy tale by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont. But that's where the similarity with the original story ends. Jeanne wrote that Beauty was the youngest daughter, and she had two sisters. And then the fairy tale exactly repeats our Scarlet Flower. What a terrible thing. In fact, the beauty was sent to die without food and help in the deep forest. The sisters hoped that a terrible monster would devour her there.

Hansel and Gretel

Although the Brothers Grimm provided the fairy tale with a happy ending, the events that haunted the brother and sister can leave dark traces in the soul of children. Two parents left the kids in the forest to die because they could not feed themselves (what a noble message, instilled in children's minds). Once in the abode of the forest witch, the children barely escaped. The only thing supposedly fair in the tale is that the mother cuckoo dies a strange death at the end. Although, too, this: what kind of inoculation of vindictive ideas?

Two parents left the kids in the forest to die because they could not feed themselves (what a noble message, instilled in children's minds). Once in the abode of the forest witch, the children barely escaped. The only thing supposedly fair in the tale is that the mother cuckoo dies a strange death at the end. Although, too, this: what kind of inoculation of vindictive ideas?

Rumplestiltskin

A tale of a vicious dwarf who could spin gold from straw. In the original version of the Brothers Grimm's fairy tale, he helps the miller's daughter, who lies to the king that she can spin gold from straw. The dwarf asks in return for the favor of her unborn child. When the child is born, and the girl does not agree to return it to the dwarf, he says that if she guesses his name, he will leave the child to her. The girl accidentally hears a song and says the name of the dwarf. In the last edition of the tale, the dwarf simply runs away in anger. But initially, he falls under the floor, and, trying to get out, pulls his leg and tears into two parts in front of the girl. A very uplifting story.

A very uplifting story.

The Princess and the Frog (The Frog King)

The fairy tale was also written by the Brothers Grimm. If in Russian fairy tales the frog turns out to be a princess, then there is a prince. And if in the later version of the tale, refusing to kiss meant the eternal imprisonment of the young prince in the body of a frog, then in the early version, the wrong spell that replaced the kiss flattened the unfortunate frog against the wall. Then the corpse of the frog lost its head and spontaneously ignited. Obviously, animal rights were not heard at the time of the creation of fairy tales.

Masha and the three bears

This cute fairy tale features a little golden-haired girl who got lost in the forest and ended up in the house of three bears. The child eats their food, sits on their chairs, and falls asleep on the bear's bed. When the bears return, the girl wakes up and runs out of the window out of fear.

This tale (published for the first time in 1837) has two originals.