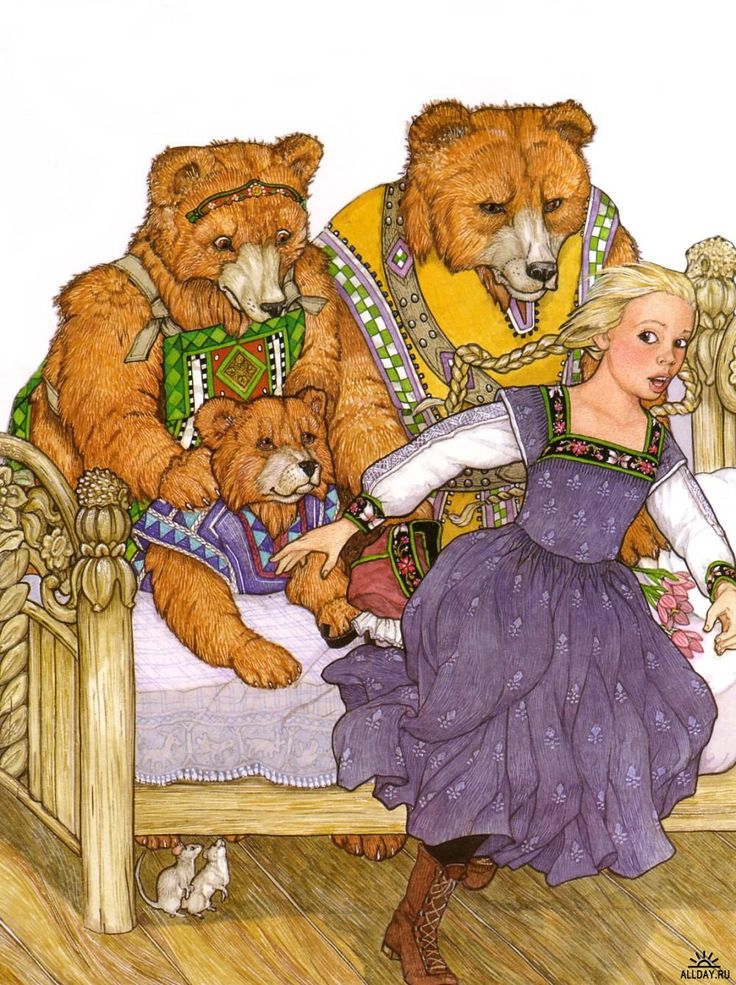

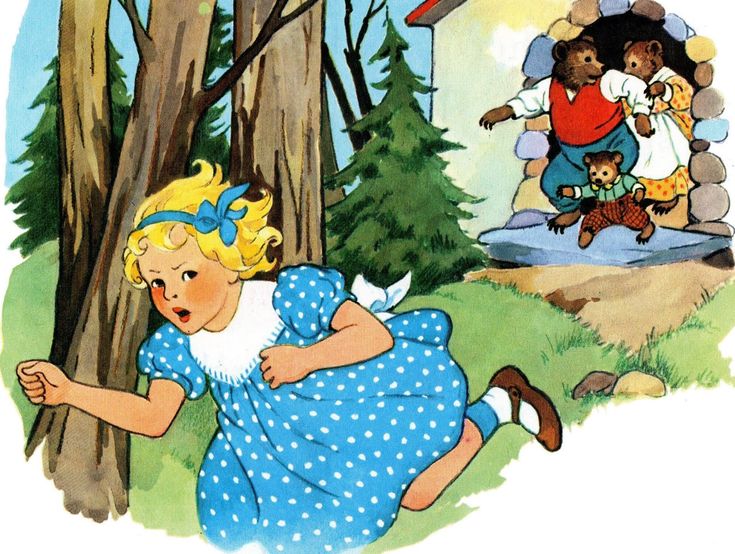

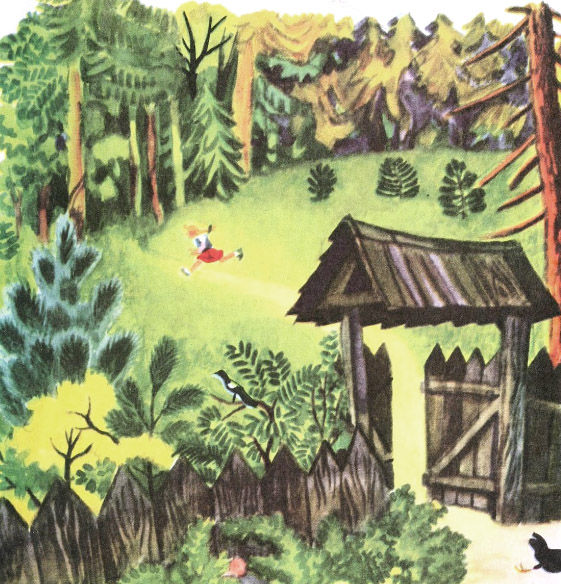

Goldilocks running away

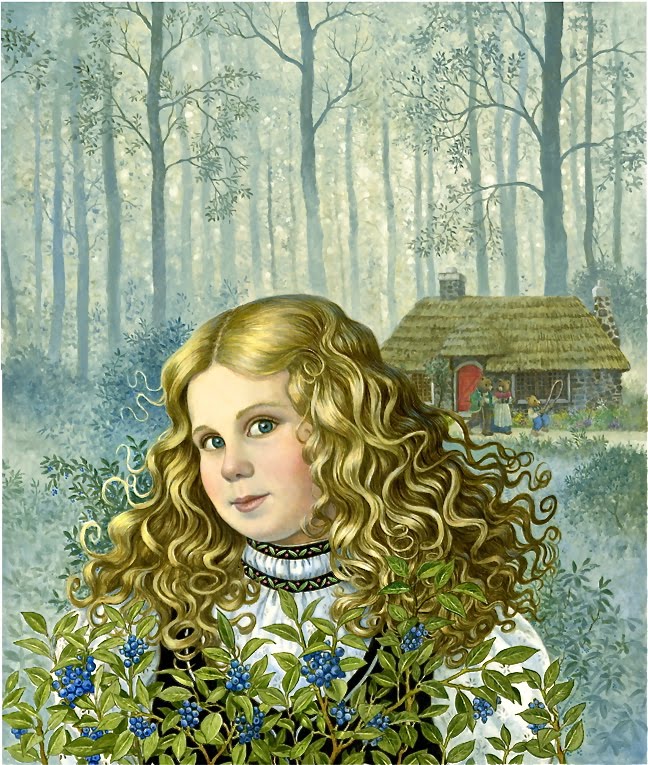

She Doesn’t Always Get Away: Goldilocks and the Three Bears

It’s such a kind, cuddly story—three cute bears with a rather alarming obsession with porridge and taking long healthy walks in the woods (really, bears, is this any example to set to small children), one small golden haired girl who is just hungry and tired and doesn’t want porridge that burns her mouth—a perfectly understandable feeling, really.

Or at least, it’s a kind cuddly story now.

In the earliest written version, the bears set Goldilocks on fire.

That version was written down in 1831 by Eleanor Mure, someone we know little of besides the name. The granddaughter of a baron and daughter of a barrister, she was apparently born around 1799, never married, was at some point taught how to use watercolors, and died in 1886. And that’s about it. We can, however, guess that she was fond of fairy tales and bears—and very fond of a young nephew, Horace Broke. Fond enough to write a poem about the Three Bears and inscribe it in his very own handcrafted book for his fourth birthday in 1831.

It must have taken her at least a few weeks if not more to put the book together, both to compose the poem and paint the watercolor illustrations of the three bears and St. Paul’s Cathedral, stunningly free of any surrounding buildings. In her version, all animals can talk. Three bears (in Mure’s watercolors, all about the same size, although the text claims that the third bear is “little”) take advantage of this speaking ability to buy a nice house in the neighborhood, already furnished.

Almost immediately, they run into social trouble when they decide not to receive one of their neighbors, an old lady. Her immediate response is straight from Jane Austen and other books of manners and social interactions: she calls the bears “impertinent” and to ask exactly how they can justify giving themselves airs. Her next response, however, is not exactly something that Jane Austen would applaud: after getting told to go away, she decides to walk into the house and explore it—an exploration that includes drinking out of their three cups of milk, trying their three chairs (and breaking one) and trying out their three beds (breaking one of those as well). The infuriated bears, after finding the milk, the chairs and the beds, decide to take their revenge—first throwing her into a fire and then into water, before finally throwing her on top of the steeple of St. Paul’s Cathedral and leaving her there.

The infuriated bears, after finding the milk, the chairs and the beds, decide to take their revenge—first throwing her into a fire and then into water, before finally throwing her on top of the steeple of St. Paul’s Cathedral and leaving her there.

The poetry is more than a bit rough, as is the language—I have a bit of difficulty thinking that anyone even in 1831 would casually drop “Adzooks!” into a sentence, although I suppose if you’re going to use “Adzooks” at all (and Microsoft Word’s spell checker, for one, would prefer that you didn’t) it might as well be in a poem about bears. Her nephew, at least, treasured the book enough to keep it until his death in 1909, when it was purchased, along with the rest of his library, by librarian Edgar Osborne, who in turn donated the collection to the Toronto Public Library in 1949, which publicized the find in 1951, and in 2010, very kindly published a pdf facsimile online which allows all of us to see Mure’s little watercolors with the three bears.

Mure’s poem, however, apparently failed to circulate outside of her immediate family, or perhaps even her nephew, possibly because of the “Adzooks!” It was left to poet Robert Southey to popularize the story in print form, in his 1837 collection of writings, The Doctor.

Southey is probably best known these days as a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (the two men married two sisters). In his own time, Southey was initially considered a radical—though he was also the same radical who kindly advised Charlotte Bronte that “Literature is not the business of a woman’s life.” To be somewhat fair, Southey may have been thinking of his own career: he, too, lacked the funds to focus completely on poetry, needing to support himself through nonfiction work after nonfiction work. Eventually, he accepted a government pension, accepting that he did not have a large enough estate or writing income to live on. He also moved away from his earlier radicalism—and some of this friends—though he continued to protest living conditions in various slums and the growing use of child labor in the earlier part of the 19th century.

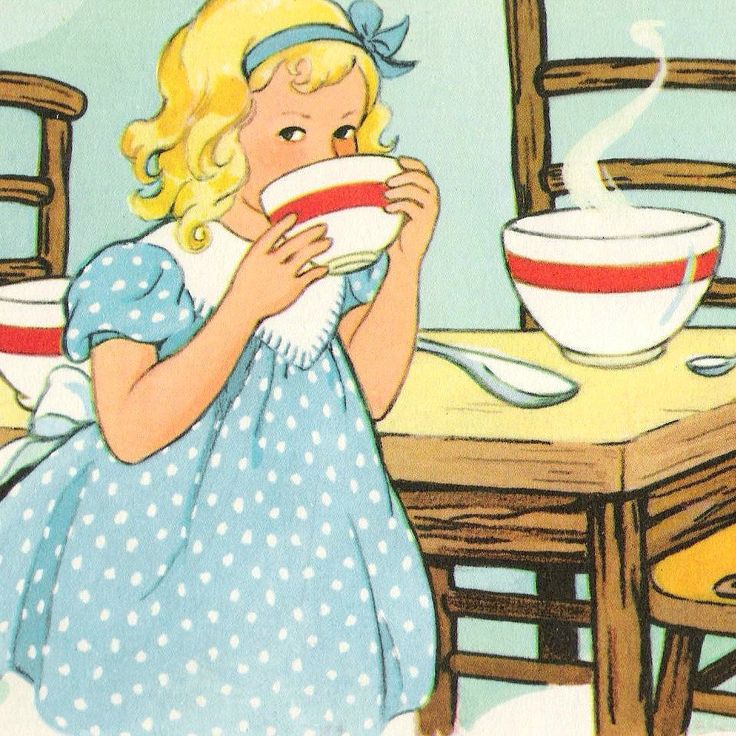

His prose version of “The Three Bears” was published after he had accepted that government pension and joined the Tory Party. In his version, the bears live not in a lovely, furnished country mansion, but in a house in the woods—more or less where bears might be expected to be found. After finding that their porridge is too hot, they head out for a nice walk in the woods. At this point, an old woman finds their house, heads in, and starts helping herself to the porridge, chairs and the beds.

It’s a longer, more elaborate version than either Mure’s poem or the many picture books that followed him, thanks to the many details Southey included about the chair cushions and the old lady—bits left out of most current versions. What did endure was something that doesn’t appear in Mure’s version: the ongoing repetition of “SOMEBODY’S BEEN EATING MY PORRIDGE,” and “SOMEBODY’S BEEN SITTING IN MY CHAIR.” Whether Southey’s original invention, or something taken from the earlier oral version that inspired both Mure and Southey, those repetitive sentences—perfect for reciting in different silly voices—endured.

Southey’s bears are just a little bit less civilized than Mure’s bears—in Southey’s words, “a little rough or so,” since they are bears. As his old woman: described as an impudent, bad old woman, she uses rough language (Southey, knowing the story would be read to or by children, does not elaborate) and doesn’t even try to get an invitation first. But both stories can be read as reactions to changing social conditions in England and France. Mure presents her story as a clash between established residents and new renters who—understandably—demand to be treated with the same respect as the older, established residents, in a mirror of the many cases of new merchant money investing in or renting older, established homes. Southey shows his growing fears of unemployed, desperate strangers breaking into quiet homes, searching for food and a place to rest. His story ends with the suggestion that the old woman either died alone in the woods, or ended up getting arrested for vagrancy.

Southey’s story was later turned into verse by a certain G. N. (credited as George Nicol in some sources) on the basis that, as he said:

N. (credited as George Nicol in some sources) on the basis that, as he said:

But fearing in your book it might

Escape some little people’s sight

I did not that one should lose

What will them all so much amuse,

As you might be gathering from this little excerpt, the verse was not particularly profound, or good; the book, based on the version digitized by Google, also contained numerous printing errors. (The digitized Google version does preserve the changes in font size used for the bears’ dialogue.) The illustrations, however, including an early one showing the bears happily smoking and wearing delightful little reading glasses, were wonderful—despite the suggestion that the Three Bears were not exactly great at housekeeping. (Well, to be fair, they were bears.)

To be fair, some of the poetic issues stem from Victorian reticence:

Somebody in my chair has been!”

The middle Bear exclaim’d;

Seeing the cushion dented in

By what may not be named.

(Later Victorians, I should note, thought even this—and the verse that follows, which, I should warn you, suggests the human bottom – was far too much, ordering writers to delete Southey’s similar reference and anything that so much as implied a reference to that part of the human or bear anatomy. Even these days, the exact method that Goldilocks uses to dent the chair and later break the little bear’s chair are left discreetly unmentioned.)

Others stem from a seeming lack of vocabulary:

She burn’d her mouth, at which half mad

she said a naughty word;

a naughty word it was and bad

As ever could be heard.

Joseph Cundall, for one, was unimpressed, deciding to return to Southey’s prose version of the tale for his 1849 collection, Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. Cundall did, however, make one critical and lasting change to the tale: he changed Southey’s intruder from an elderly lady to a young girl called Silver-Hair. Cundall felt that fairy tales had enough old women, and not enough young girls; his introduction also suggests that he may have heard another oral version of the tale where the protagonist was named Silver Hair. Shortly after publishing this version, Cundall went bankrupt, and abandoned both children’s literature and printing for the more lucrative (for him) profession of photography.

Cundall felt that fairy tales had enough old women, and not enough young girls; his introduction also suggests that he may have heard another oral version of the tale where the protagonist was named Silver Hair. Shortly after publishing this version, Cundall went bankrupt, and abandoned both children’s literature and printing for the more lucrative (for him) profession of photography.

The bankruptcy did not prevent other Victorian children’s writers from seizing his idea and using it in their own versions of the Three Bears, making other alterations along the way. Slowly, the bears turned into a Bear Family, with a Papa, Mama and Baby Bear (in the Mure, Southey, G.N. and Cundall versions, the bears are all male). The intruder changed names from Silver Hair to Golden Hair to Silver Locks to, eventually, Goldilocks. But in all of these versions, she remained a girl, often a very young one indeed, and in some cases, even turned into the tired, hungry protagonist of the tale—a girl in danger of getting eaten by bears.

I suspect, however, that like me, many small children felt more sympathy for the small bear. I mean, the girl ate his ENTIRE BREAKFAST AND BROKE HIS CHAIR. As a small child with a younger brother who was known for occasionally CHEWING MY TOYS, I completely understood Baby Bear’s howls of outrage here. I’m just saying.

The story was popular enough to spawn multiple picture books throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which in turn led to some authors taking a rather hard look at Goldilocks. (Like me, many of these authors were inclined to be on the side of Baby Bear.) Many of the versions took elaborate liberties with the story—as in my personal recent favorite, Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs, by Mo Willems, recommended to me by an excited four year old. Not only does it change the traditional porridge to chocolate pudding, which frankly makes far more sense for breakfast, it also, as the title might have warned, has dinosaurs, though I should warn my adult readers that alas, no, the dinosaurs do not eat Goldilocks, which may be a disappointment to many.

For the most part, the illustrations in the picture books range from adequate to marvelous—a far step above the amateur watercolors so carefully created by Mure in 1837. But the story survived, I think, not because of the illustrations, but because when properly told by a teller who is willing to do different voices for all three bears, it’s not just exciting but HILARIOUS, especially when you are three. It was the start, for me, of a small obsession with bears.

But I must admit, as comforting as it is on some level to know that in most versions, Goldilocks does get safely away (after all, in the privacy of this post, I must admit that my brother was not the only child who broke things in our house, and it’s kinda nice to know that breaking a chair won’t immediately lead to getting eaten by bears) it’s equally comforting to know that in at least one earlier version, she didn’t.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

citation

Goldilocks and the Three Bears - Teaching Children Philosophy

+

Search for:by Candice Ransom

FILTERS: ethics, grade-1-2, prek-k

Book Module Navigation

Summary »

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion »

Questions for Philosophical Discussion »

Summary

Looking at this classic tale through a philosophical lens can prompt discussions about selfishness, ownership, and perfectionism.

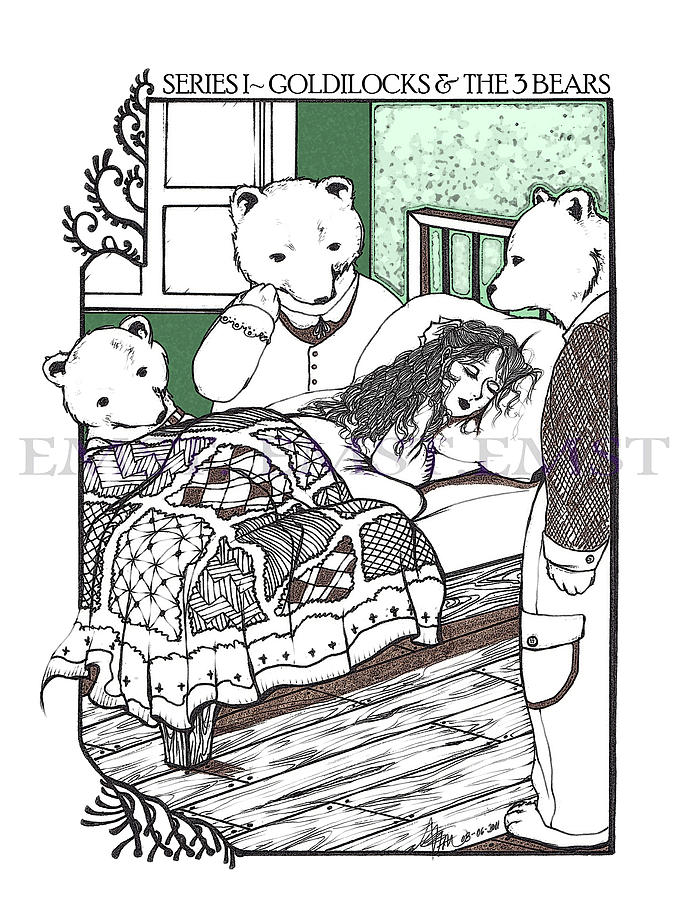

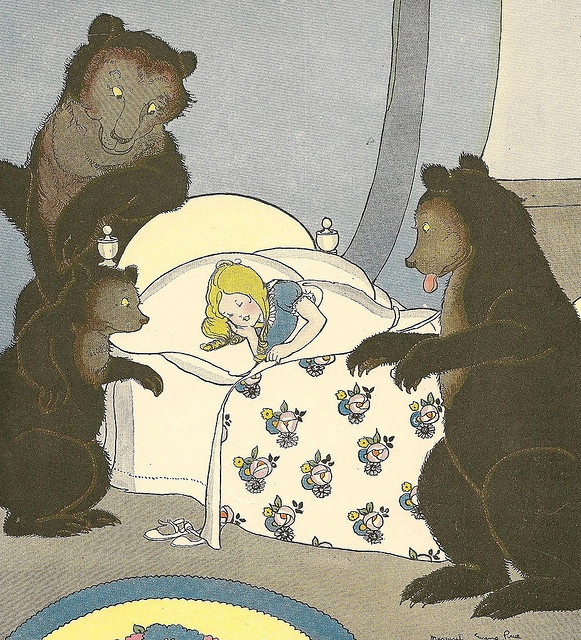

Goldilocks goes for a walk in the forest and comes upon a house. She enters and helps herself to porridge, sits in the chairs, and sleeps in the beds. Meanwhile, the bears who own the house come home and much to their surprise they discover the outcome of what Goldilocks has done to their porridge, chairs and their beds. Goldilocks wakes with a fright when she sees and hears the bears; she jumps from the bed and runs away as fast as she can.

Read aloud video by Read to My Child

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Robert Southey is one of many modern interpretations of one of the most popular fairy tales in the English language. Readers are often relieved to discover that Goldilocks makes a quick escape out of the window, running back into the forest, saving her from what could have otherwise been a devastating conclusion. The moral reasoning of the story is strung between self concern/preservation and transgressive social rule breaking.

Most of the students in the class have probably encountered the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears before. The facilitator of the philosophical discussion can thus ask if anyone has not heard of the story before. The teacher can also request that as Goldilocks and the Three Bears is being read, the students should be listening as if they are the bears themselves.

The theme in the story–how your actions might hurt others–is illustrated through the concept of trespassing (or possibly “breaking and entering”). When Goldilocks hears no answer after knocking on the cottage door, she enters and helps herself to the bears’ porridge, sits in their chairs, and finally falls asleep in the comfiest bed. Goldilocks has made herself right at home; apparently she does not consider whose house she is in and when they will be returning home. The first question set will guide the students in an explorative discussion on the definition of trespassing while asking them to refer to their own experiences.

The second philosophical discussion surrounds the issue of Goldilocks being motivated by selfishness. The common fable repetition of three involves Goldilocks trying three of everything until she finds something that is just right! Goldilocks feels a sense of entitlement to what does not belong to her. Modern terminology such as a “Goldilocks planet” or a “goldilocks economy,” named after the fairytale girl, suggest this driving towards perfect satisfaction. The second question set addresses how the students determine what is “just right”!

After the conclusion of the story and philosophical discussion, the teacher can follow up with optional activities. Such activities include the students pretending to be Goldilocks and writing an apology letter to the Three Bears, or another creative writing project that asks the student to be the author of the story, making it from the perspective of the Three Bears. The third question set offers possible resolutions to Goldilocks and the Three Bears which could serve as tools in the follow up activities.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

In the story, Goldilocks goes into the house and uses the things in the house without permission.

- Has anyone ever used something that belonged to you without your permission? How did you feel? Why did you feel this way?

- Who can give examples of cases when it is okay to use something that belongs to someone without their permission? What makes these situations different?

- Imagine that everything was owned by one person. Would you need that person’s permission to have a drink of water? Alternatively, what if everything was owned by others, but you didn’t own anything?

- Why do we own things anyway? For any answer that is given, challenge students to find at least one example that questions that answer.

The story abruptly concludes with Goldilocks running back into the forest.

- Why did Goldilocks run away?

- How do you think the bears felt that someone was in their house without their permission?

- How do the bears feel that Goldilocks ran away with no explanation or apology?

- What could be another way to end the story?

- Was Goldilocks sorry or was she just afraid? Can these ever be the same thing?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Joseph LaCoste and Mikala Smith..jpg) Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.

Download & PrintEmail Book Module Back to All Books

Back to All Books

Module by Joseph LaCoste and Mikala Smith

Download & PrintEmail Book Module

About the Prindle Institute

As one of the largest collegiate ethics institutes in the country, the Prindle Institute for Ethics’ uniquely robust national outreach mission serves DePauw students, faculty and staff; academics and scholars throughout the United States and in the international community; life-long learners; and the Greencastle community in a variety of ways. In 2019, the Prindle Institute partrnered with Thomas Wartenberg and became the digital home of his Teaching Children Philosophy discussion guides.

Further Resources

Some of the books on this site may contain characterizations or illustrations that are culturally insensitive or inaccurate. We encourage educators to visit the Association for Library Service to Children’s resource guide for talking to children about issues of race and culture in literature. They also have a guide for navigating tough conversations. PBS Kids’ set of resources for talking to young children about race and racism might also be useful for educators.

We encourage educators to visit the Association for Library Service to Children’s resource guide for talking to children about issues of race and culture in literature. They also have a guide for navigating tough conversations. PBS Kids’ set of resources for talking to young children about race and racism might also be useful for educators.

Philosophy often deals with big questions like the existence of a higher power or death. Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our resources page.

Visit Us.

LOCATION

2961 W County Road 225 S

Greencastle, IN 46135

P: (765) 658-4075

GET DIRECTIONS

BUILDING HOURS

Monday - Friday: 8AM - 5PM

Saturday-Sunday: closed

Monday - Friday: 8AM - 5PM

JUMP TO TOP

Three Bears - Wiki

This term has other meanings, see Three Bears (meanings).

Masha (still "one girl") runs away from three bears.

Illustration by Yuri Vasnetsov for the 1935 edition of Leo Tolstoy's fairy tale.

The Three Bears (also Goldilocks and the Three Bears in English and Masha and the Three Bears in Russian) is a popular English children's fairy tale translated into many languages of the world. In Russian, it was widely used in the retelling of Leo Tolstoy. In the most common English version, the girl's name is Goldilocks (eng. Goldilocks, literally "Golden-haired"). For Tolstoy, the heroine initially had no name and was simply called “one girl” [1] . Later, in the Russian version of the fairy tale, the name Masha (a diminutive of Maria) was assigned to the girl due to contamination with the heroine of the popular Russian fairy tale "Masha and the Bear" [2] .

Contents

- 1 History of

- 2 Plot

- 3 Interesting facts

- 4 Screen versions

- 5 See also

- 6 Notes

- 7 Links

Creation story

Goldilocks is running away from three bears.

1912 American edition.

Modern folklorists trace the roots of the English version of the tale to the similar Scottish tale of three bears and a cunning fox [3] . Having climbed into the house of bears and played pranks there, the fox fell asleep in the bed of the smallest bear, was caught there by the returning owners and was forced to flee. In the tale, his name is simply "sly fox." In John D. Batten's [en] "returned to the roots" version of the tale 1894 years old fox named Scrapefoot [4] .

The tale was introduced into literary tradition in 1837 by Robert Southey as The Story of the Three Bears [5] . In his version, the protagonist is not a fox, but a “little old woman” with a hooligan character. There is an assumption [3] that Southey heard this story in childhood from his uncle William Tuller and as a child understood the word vixen not in its basic meaning ("fox"), but figuratively ("extremely grumpy woman"). This, however, does not explain why he made her an old woman.

This, however, does not explain why he made her an old woman.

In Southey's tale, three anthropomorphic male bears, "a small bear, a medium bear and a huge bear", live together in a house in the woods. Southey describes them as good-natured, trusting, harmless, neat and hospitable. Each of them has their own bowl of porridge, a chair and a bed. They went for a walk in the forest while the porridge was cooling. The woman was kicked out of her family because she was a disgrace to them. She is described at various points in the story as a brazen, bad, foul-mouthed, ugly, dirty vagrant who deserves to be in a penitentiary. A woman in the woods stumbles upon a house of bears, looks through the window, peeks through the keyhole, lifts the latch and, making sure no one is home, enters.

As early as 1813 (before publication in 1837) Southey was telling his version of the tale to friends and acquaintances. In 1831, Eleanor Mure transcribed the tale she heard into verse and presented it in a handwritten album to her nephew Horace Brock for his birthday. Southey's and Muir's variants differ in details. Southey's bears eat oatmeal, while Muir's bears drink milk. Southey's old woman has no reason to break into the house, and Muir's old woman was offended when she was denied a courtesy visit. Eleanor Muir's version turned out and remained the most bloodthirsty in the history of the plot. In all other versions, a fox, an old woman or a girl flees through the window and nothing is said about their further fate. In Muir, an old woman jumps out the window of a high-rise building in Rome and impales herself on the spire of St. Paul's Cathedral [6] .

Southey's and Muir's variants differ in details. Southey's bears eat oatmeal, while Muir's bears drink milk. Southey's old woman has no reason to break into the house, and Muir's old woman was offended when she was denied a courtesy visit. Eleanor Muir's version turned out and remained the most bloodthirsty in the history of the plot. In all other versions, a fox, an old woman or a girl flees through the window and nothing is said about their further fate. In Muir, an old woman jumps out the window of a high-rise building in Rome and impales herself on the spire of St. Paul's Cathedral [6] .

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie [en] (Iona and Peter Opie) point out in their 1999 book The Classic Fairy Tales that the tale of the three bears is a partial analogue of Snow White: the lost princess enters the house of the dwarves, tastes their food and falls asleep in one of the beds. In a manner similar to three bears, the gnomes cry: "Someone was sitting in my chair!", "Someone ate from my plate!" and "Someone was sleeping in my bed!". The opies also point to similarities with the Norwegian tale of a princess who takes refuge in a cave inhabited by three Russian princes dressed in bearskins. She eats their food and hides under the bed.

The opies also point to similarities with the Norwegian tale of a princess who takes refuge in a cave inhabited by three Russian princes dressed in bearskins. She eats their food and hides under the bed.

An important step in bringing the fairy tale to a modern look was made by the English writer Joseph Candall [en] . In 1850 his Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children [7] was published. In his version of The Three Bears, a little girl becomes the hero, and any motive of hooliganism is removed: the girl tries to eat and sleep, simply because she got lost in the forest, tired and hungry. True, the girl's name is not Goldilocks yet, but Silver-Hair. In the preface, Candall explained his choice as follows [6] :

|

After the appearance in a new form, the heroine often changed names depending on the publications. At first, her hair color was silver: Silver-Hair (1850), Silver-Locks (1858), Silverhair (1867). Since the 1868 edition, the hair color has changed and the girl became Goldilocks (Golden Hair) in the 19 edition that was finally established04 version of Goldilocks (literally Golden-haired , or, keeping the diminutive from the original, Golden Curls ) [8] .

In Russia, the tale appeared and quickly became popular in the retelling and adaptation of Leo Tolstoy (the first edition is the "New ABC" of 1875, the fairy tale "Three Bears" [ source not specified 1995 days ] [9] ). His name is simply “one girl”, however, in the English versions at the end of the 19th century, the final name has not yet been settled. But all three bears get names: the father's name is Mikhail Ivanovich, his wife is Nastasya Petrovna, and their little son is Mishutka.

But all three bears get names: the father's name is Mikhail Ivanovich, his wife is Nastasya Petrovna, and their little son is Mishutka.

Plot

A little girl, lost in the forest, finds an empty dwelling and enters it. She discovers three items of different sizes - plates, chairs, beds - and tries to use them, while two items from each set turn out to be unacceptable for her for one reason or another, and the third is “just right”. After she falls asleep, the owners return to the dwelling - a bear, a bear and a bear cub, who are outraged that someone touched their things, and the awakened girl flees through the window.

interesting facts too far away and cold. Also similar in meaning to it, the term "Goldilocks Stars" is found to refer to K-class stars.

The main character is the Eskimo girl Alu-Ki (English Aloo-ki), the action of the tale takes place in the north, and the bears are white [10] .

The main character is the Eskimo girl Alu-Ki (English Aloo-ki), the action of the tale takes place in the north, and the bears are white [10] . Screen adaptations

- The 'Teddy' Bears - American film 1907 directed by Edwin Porter based on the English fairy tale "Goldilocks and the Three Bears".

- "Three Bears" - a Soviet cartoon of 1937 based on a fairy tale retelling by Leo Tolstoy.

- "Three Bears" - Soviet cartoon of 1958, also based on the fairy tale by Leo Tolstoy. The main character is called, oddly enough, Varvarushka.

- In 1962 and 1971 filmstrips based on this fairy tale were produced in the USSR (also according to Leo Tolstoy's version).

- In 1983, the program "Alarm Clock" showed a musical interpretation of the fairy tale "Three Bears" with the participation of Sergei and Nastya Prokhanov, the dance group of the Big Children's Choir, trainers Ibragimovs and three circus bears. The music for the soundtracks was written by Grigory Gladkov, the lyrics were written by Leonid Yakhnin.

- "Three Bears" - Soviet cartoon-opera.

- In the children's media franchise Ever After High, one of the recurring characters is the daughter of the now-grown-up Goldilocks, her name is Blondie Lockes. In her name, the full homonymy of lock is used both as a “curl of hair” and as a “castle”. Therefore, her name can be translated as "Blond Curls", and her main talent is the ability to open any locks.

- In Grimm, the episode "Bears Remain Bears" in the second episode of the first season is based on the fairy tale "The Three Bears".

- Animated series-crossover "Goldie and Bear".

- In a cat in boots 2, it appears as a gang

cm. Also

- Zlatovlask (values)

Notes

- ↑ Tolstoy L. N. Three Bear (neopr.) . Magazine "Bonfire". Retrieved 30 March 2013. Archived 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Masha and the Bear / Under revision M.

1 2 Graham Seal. Goldilocks // Encyclopedia of folk heroes. - US: ABC-CLIO, 2001. - S. 90-92. — ISBN 1576072169.

1 2 Graham Seal. Goldilocks // Encyclopedia of folk heroes. - US: ABC-CLIO, 2001. - S. 90-92. — ISBN 1576072169. - ↑ "Scrapefoot" in Wikisource

- ↑ "The Story of the Three Bears" in Wikisource

- ↑ 1 2 Iona Opie, Peter Opie. The Classic fairy tales . - UK: Oxford University Press, 1992. - P. 200. - ISBN 0192115596.

- ↑ Joseph Cundall. A treasury of pleasure books for young children (undefined) . Retrieved 30 March 2013. Archived April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Maria Tatar. The annotated classic fairy tales. - US: WW Norton & Company, 2002. - P. 245. - ISBN 0393051633.

- ↑ FEB: Gusev. Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy: Materials for a biography from 1870 to 1881.

- 1963 (text) (unspecified) . feb-web.ru. Retrieved 8 May 2017. Archived 16 September 2014.

- 1963 (text) (unspecified) . feb-web.ru. Retrieved 8 May 2017. Archived 16 September 2014. - ↑ Summary/reviews: The three snow bears (unspecified) (link unavailable) . Retrieved 26 March 2017. Archived 26 March 2017.

Links

- The fairy tale "Three Bears" in the retelling of Leo Tolstoy (neopr.) . RVB. Retrieved: March 30, 2013.

- Emelyanova O. V. Three bears. Scenario for staging the fairy tale by L. N. Tolstoy in the puppet theater (unspecified) . Retrieved March 30, 2013

Three Bears (also Goldilocks and Three Bears in English and "Masha and the Three Bears" in Russian) is a popular English children's fairy tale translated into many languages of the world.

In Russian, it was widely used in the retelling of Leo Tolstoy. In the most common English version, the girl's name is Goldilocks (English Goldilocks, literally "Golden-haired"). In Tolstoy, the heroine initially had no name and was simply called “one girl” . Later, in the Russian version of the fairy tale, the name Masha (a diminutive of Maria) was assigned to the girl due to contamination with the heroine of the popular Russian fairy tale "Masha and the Bear" .

In Russian, it was widely used in the retelling of Leo Tolstoy. In the most common English version, the girl's name is Goldilocks (English Goldilocks, literally "Golden-haired"). In Tolstoy, the heroine initially had no name and was simply called “one girl” . Later, in the Russian version of the fairy tale, the name Masha (a diminutive of Maria) was assigned to the girl due to contamination with the heroine of the popular Russian fairy tale "Masha and the Bear" . Masha (still "one girl") runs away from three bears.

Illustration by Yuri Vasnetsov for the 1935 edition of Leo Tolstoy's fairy tale.Contents

- 1History of creation

- 2Story

- 3Interesting facts

- 4Screenings

- 5See. See also

- 6Notes

- 7References

Goldilocks runs away from three bears.

1912 American edition.Modern folklorists trace the roots of the English version of the tale to the similar Scottish tale of three bears and a cunning fox .

Having climbed into the house of bears and played pranks there, the fox fell asleep in the bed of the smallest bear, was caught there by the returning owners and was forced to flee. In the tale, his name is simply "sly fox." In John D. Batten's "back to the basics" version of the 1894 tale, the fox is called Scrapefoot .

Having climbed into the house of bears and played pranks there, the fox fell asleep in the bed of the smallest bear, was caught there by the returning owners and was forced to flee. In the tale, his name is simply "sly fox." In John D. Batten's "back to the basics" version of the 1894 tale, the fox is called Scrapefoot . The tale was introduced into the literary tradition in 1837 by Robert Southey as The Story of the Three Bears . In his version, the protagonist is not a fox, but a "little old woman" (a little old Woman) with a hooligan character. There is an assumption that Southey heard this story in childhood from his uncle William Tuller and as a child understood the word vixen not in its basic meaning ("fox"), but figuratively ("extremely grumpy woman"). This, however, does not explain why he made her an old woman.

In Southey's tale, three anthropomorphic male bears, "a small, medium and huge bear", live together in a house in the woods. Southey describes them as good-natured, trusting, harmless, neat and hospitable.

Each of them has their own bowl of porridge, a chair and a bed. They went for a walk in the forest while the porridge was cooling. The woman was kicked out of her family because she was a disgrace to them. She is described at various points in the story as a brazen, bad, foul-mouthed, ugly, dirty vagrant who deserves to be in a penitentiary. A woman in the woods stumbles upon a house of bears, looks through the window, peeks through the keyhole, lifts the latch and, making sure no one is home, enters.

Each of them has their own bowl of porridge, a chair and a bed. They went for a walk in the forest while the porridge was cooling. The woman was kicked out of her family because she was a disgrace to them. She is described at various points in the story as a brazen, bad, foul-mouthed, ugly, dirty vagrant who deserves to be in a penitentiary. A woman in the woods stumbles upon a house of bears, looks through the window, peeks through the keyhole, lifts the latch and, making sure no one is home, enters. As early as 1813 (before publication in 1837) Southey was telling his version of the tale to friends and acquaintances. In 1831, Eleanor Mure transcribed the tale she heard into verse and presented it in a handwritten album to her nephew Horace Brock for his birthday. Southey's and Muir's variants differ in details. Southey's bears eat oatmeal, while Muir's bears drink milk. Southey's old woman has no reason to break into the house, and Muir's old woman was offended when she was denied a courtesy visit.

Eleanor Muir's version turned out and remained the most bloodthirsty in the history of the plot. In all other versions, a fox, an old woman or a girl flees through the window and nothing is said about their further fate. In Muir, an old woman jumps out the window of a high-rise building in Rome and impales herself on the spire of St. Paul's Cathedral .

Eleanor Muir's version turned out and remained the most bloodthirsty in the history of the plot. In all other versions, a fox, an old woman or a girl flees through the window and nothing is said about their further fate. In Muir, an old woman jumps out the window of a high-rise building in Rome and impales herself on the spire of St. Paul's Cathedral . Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie [en] (Iona and Peter Opie) point out in their 1999 book "The Classic Fairy Tales" that the tale of the three bears is a partial analogue of "Snow White": the lost princess enters the house of the dwarfs, tries their food and falls asleep in one of the beds. In a manner similar to three bears, the gnomes cry: "Someone was sitting in my chair!", "Someone ate from my plate!" and "Someone was sleeping in my bed!". The opies also point to similarities with the Norwegian tale of a princess who takes refuge in a cave inhabited by three Russian princes dressed in bearskins. She eats their food and hides under the bed.

An important step in bringing the fairy tale to a modern look was made by the English writer Joseph Candall [en] . In 1850, his Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children, , was published. In his version of The Three Bears, a little girl becomes the hero, and any motive of hooliganism is removed: the girl tries to eat and sleep, simply because she got lost in the forest, tired and hungry. True, the girl's name is not Goldilocks yet, but Silver-Hair. In the preface, Candall explained his choice as follows :

The Tale of the Three Bears is a very old tale, but it has never been told so well by anyone as by the great poet Southey, whose version (with his permission) I share with you. Only a little girl invades my house, not an old woman. I did this because I find the Silver-Haired version better known, and because there are already so many other stories about old women.

Original text

The "Story of the Three Bears" is a very old Nursery Tale, but it was never so well told as by the great poet Southey, whose version I have (with permission) given you, only I have made the intruder a little girl instead of an old woman.

This I did because I found that the tale is better known with Silver-Hair, and because there are so many other stories of old women.

This I did because I found that the tale is better known with Silver-Hair, and because there are so many other stories of old women. After the appearance in a new form, the heroine often changed names depending on publications. At first her hair color was silver: Silver-Hair (1850), Silver-Locks (1858), Silverhair (1867). Since the 1868 edition, the hair color has changed and the girl has become Goldilocks (Golden Hair) in the version finally approved from the 1904 edition of Goldilocks (literally Golden-haired , or, keeping the diminutive from the original, Golden Curls ) .

In Russia, the tale appeared and quickly became popular in the retelling and adaptation of Leo Tolstoy (first edition - "New ABC" in 1875, the fairy tale "Three Bears" [ source not specified 1551 days ] ). His name is simply “one girl”, however, in the English versions at the end of the 19th century, the final name has not yet been settled.

But all three bears get names: the father's name is Mikhail Ivanovich, his wife is Nastasya Petrovna, and their little son is Mishutka.

But all three bears get names: the father's name is Mikhail Ivanovich, his wife is Nastasya Petrovna, and their little son is Mishutka. A little girl, lost in the forest, finds an empty dwelling and enters it. She discovers three items of different sizes - plates, chairs, beds - and tries to use them, while two items from each set turn out to be unacceptable for her for one reason or another, and the third is “just right”. After she falls asleep, the owners return to the dwelling - a bear, a bear and a bear cub, who are outraged that someone touched their things, and the awakened girl flees through the window.

- By analogy with the plot of a fairy tale, English-speaking astronomers came up with the term "Goldilocks Zone" - a zone around a star where life is possible, that is, not too close to the star and hot, but not too far from it and cold . Also similar in meaning to it, the term "Goldilocks Stars" is found to refer to K-class stars.

- A parody and modernized presentation of the plot of the tale is contained in the 1982 poetry collection Revolting Rhymes by Roald Dahl.

- American children's writer Jan Brett [en] (Eng. Jan Brett) in 2007 published the fairy tale "The Three Snow Bears" (The Three Snow Bears), based on the plot of the fairy tale about Goldilocks. The main character is the Eskimo girl Alu-Ki (English Aloo-ki), the action of the tale takes place in the north, and the bears are white .

- The 'Teddy' Bears is a 1907 American film directed by Edwin Porter based on the English fairy tale Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

- "Three Bears" - a Soviet cartoon of 1937 based on a fairy tale retelling by Leo Tolstoy.

- "Three Bears" - Soviet cartoon of 1958, also based on the fairy tale by Leo Tolstoy. The main character is called, oddly enough, Varvarushka.

- In 1962 and 1971 filmstrips based on this fairy tale (also based on Leo Tolstoy's version) were produced in the USSR.

- In 1983, in the program "Alarm Clock", a musical interpretation of the fairy tale "Three Bears" was shown with the participation of Sergei and Nastya Prokhanov, the dance group of the Big Children's Choir, trainers Ibragimovs and three circus bears.

The music for the soundtracks was written by Grigory Gladkov, the lyrics were written by Leonid Yakhnin.

The music for the soundtracks was written by Grigory Gladkov, the lyrics were written by Leonid Yakhnin. - "Three Bears" - Soviet cartoon-opera.

- In the children's media franchise Ever After High, one of the recurring characters is the daughter of the grown-up Goldilocks, her name is Blondie Lockes. In her name, the complete homonymy of lock is used both as a “curl of hair” and as a “castle”. Therefore, her name can be translated as "Blond Curls", and her main talent is the ability to open any locks.

- In the TV series Grimm, the plot of the episode "Bears remain bears" of the second episode of the first season is based on the fairy tale "The Three Bears".

- Animated series-crossover "Goldie and Bear".

- Goldilocks (disambiguation)

- Tolstoy L. N. (neopr.) . Magazine "Bonfire". Date of access: March 30, 2013.

- Masha and the bear / In processing M. A. Bulatova. - M.

: Detgiz, 1960.

: Detgiz, 1960. - Graham Seal. // Encyclopedia of folk heroes. - US: ABC-CLIO, 2001. - S. 90-92. — ISBN 1576072169.

- "Scrapefoot" in Wikisource

- "The Story of the Three Bears" in Wikisource

- Iona Opie, Peter Opie. The Classic fairy tales. - UK: Oxford University Press, 1992. - P. 200. - ISBN 0192115596.

- Joseph Cundall. (unspecified) . Accessed 30 March 2013. 18 April 2013.

- Maria Tatar. . - US: WW Norton & Company, 2002. - S. . — ISBN 0393051633.

- (unspecified) . feb-web.ru. Retrieved: May 8, 2017 Accessed 26 March 2017. 26 March 2017.

- (undefined) . RVB. Retrieved: March 30, 2013.

- Emelyanova O.V. Date of access: March 30, 2013 , three, bears, Russian, popular, English, children's, fairy tale, translated, into, many, languages, world.

Learn more

Only a little girl invades my house, not an old woman. I did this because I find the Silver-Haired version better known, and because there are already so many other stories about old women.

Only a little girl invades my house, not an old woman. I did this because I find the Silver-Haired version better known, and because there are already so many other stories about old women.