Jack in nursery rhymes

The House That Jack Built: An English Nursery Rhyme

The House That Jack Built: An English Nursery Rhymeedited by

D. L. Ashliman

© 2009

- This is the house that Jack built.

- This is the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the cow with the crumpled horn,

That toss'd the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the maiden all forlorn,

That milk'd the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.![]()

- This is the man all tatter'd and torn,

That kissed the maiden all forlorn,

That milk'd the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the priest all shaven and shorn,

That married the man all tatter'd and torn,

That kissed the maiden all forlorn,

That milked the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.- This is the cock that crow'd in the morn,

That waked the priest all shaven and shorn,

That married the man all tatter'd and torn,

That kissed the maiden all forlorn,

That milk'd the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That kill'd the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.

- This is the farmer sowing his corn,

That kept the cock that crow'd in the morn,

That waked the priest all shaven and shorn,

That married the man all tatter'd and torn,

That kissed the maiden all forlorn,

That milk'd the cow with the crumpled horn,

That tossed the dog,

That worried the cat,

That killed the rat,

That ate the malt

That lay in the house that Jack built.

- Source: James Orchard Halliwell [Halliwell-Phillipps], The Nursery Rhymes of England: Collected Chiefly from Oral Tradition, 4th edition (London: John Russell Smith, 1846), no. 398, pp. 175-78.

- Links to additional nineteenth-century versions:

- Bentley's Miscellany, vol. 13 (London: Richard Bentley, 1843), p. 481. This is a parody of the traditional rhyme. It was first published in the Morning Chronicle, September 22, 1809.

- [William Hone], The Political House That Jack Built, illustrated by George Cruikshank (1819).

This is a parody of the traditional rhyme.

This is a parody of the traditional rhyme. - "A New House That Jack Built," The Examiner: A Sunday Paper on Politics, Domestic Economy and Theatricals, for the year 1819 (London: John Hunt, 1819), p. 652. This is a parody of the traditional rhyme.

- A Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young People (London: Sampson Low and Son, 1856), no. 5, pp. 1-16. Each story in this volume is numbered separately.

- Laura Valentine, Games for Family Parties and Children (London: Frederick Warne and Company, 1869), p. 66.

- William Alexander Clouston, Popular Tales and Fictions: Their Migrations and Transformations, vol. 1 (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1887), pp. 289-91.

Return to D. L. Ashliman's folktexts, a library of folktales, folklore, fairy tales, and mythology.

Revised May 1, 2009.

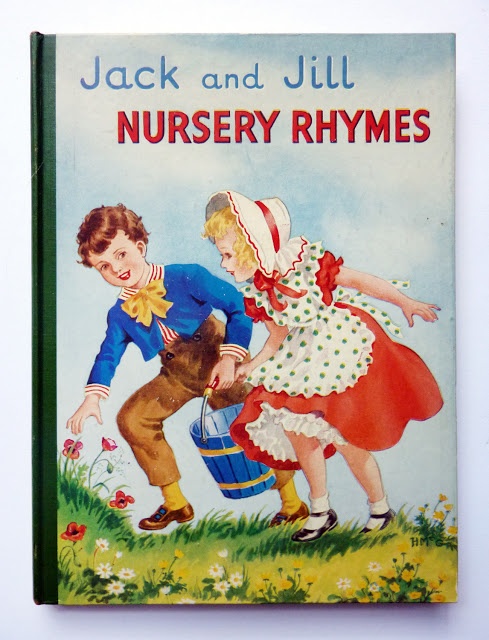

A Short Analysis of the ‘Jack and Jill’ Nursery Rhyme – Interesting Literature

LiteratureThe origins of a classic children’s rhyme – analysed by Dr Oliver Tearle

‘Jack and Jill went up the hill’: we all know these words that call back our early childhoods so vividly, yet where did they come from and what does this rhyme mean? It can be dangerous to try to probe or analyse the meaning of nursery rhymes too deeply – much like analysing the nonsense verse of Edward Lear or Lewis Carroll, we are likely to come upon a hermeneutic dead-end. But ‘Jack and Jill’ is so well-known that a closer look at its meaning and origins seems justified.

But ‘Jack and Jill’ is so well-known that a closer look at its meaning and origins seems justified.

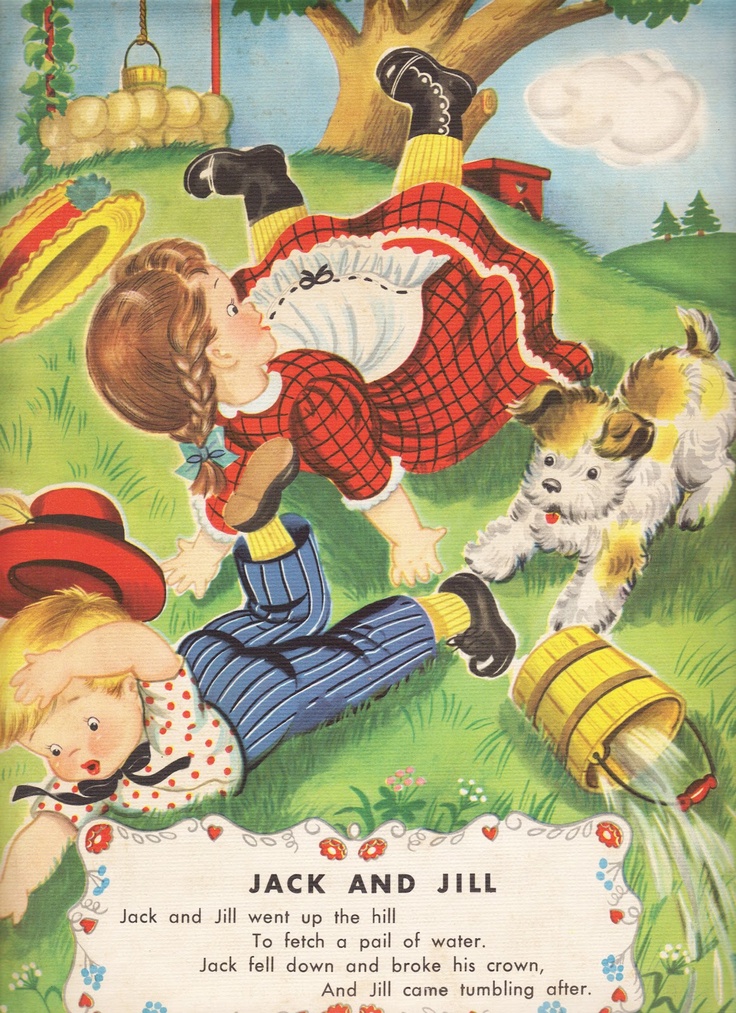

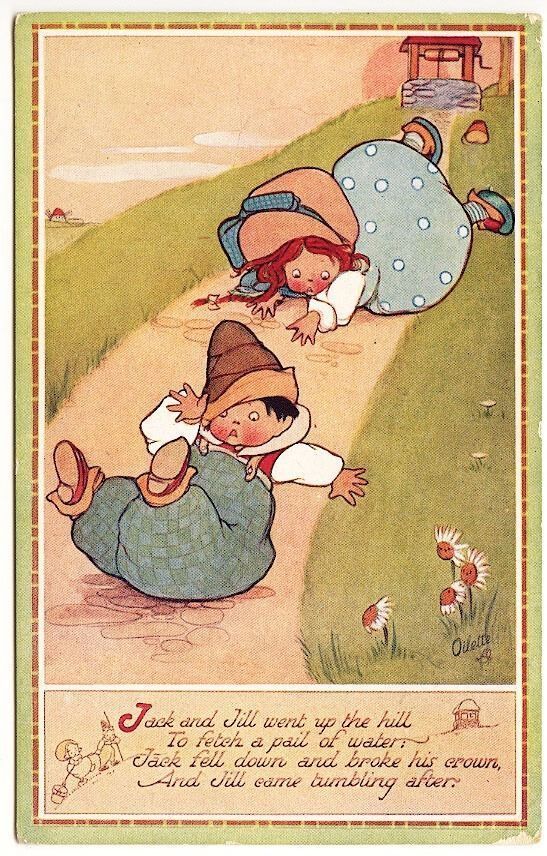

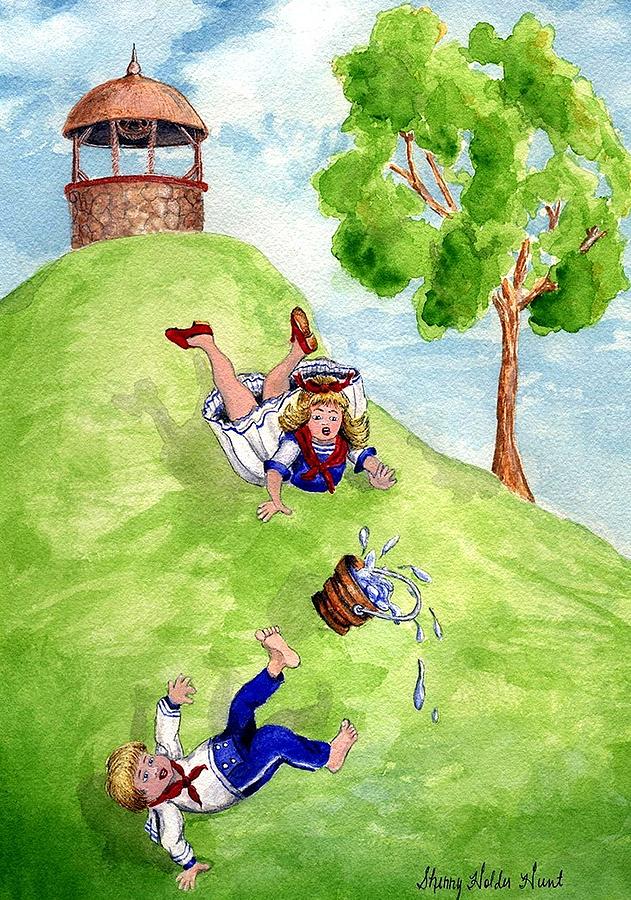

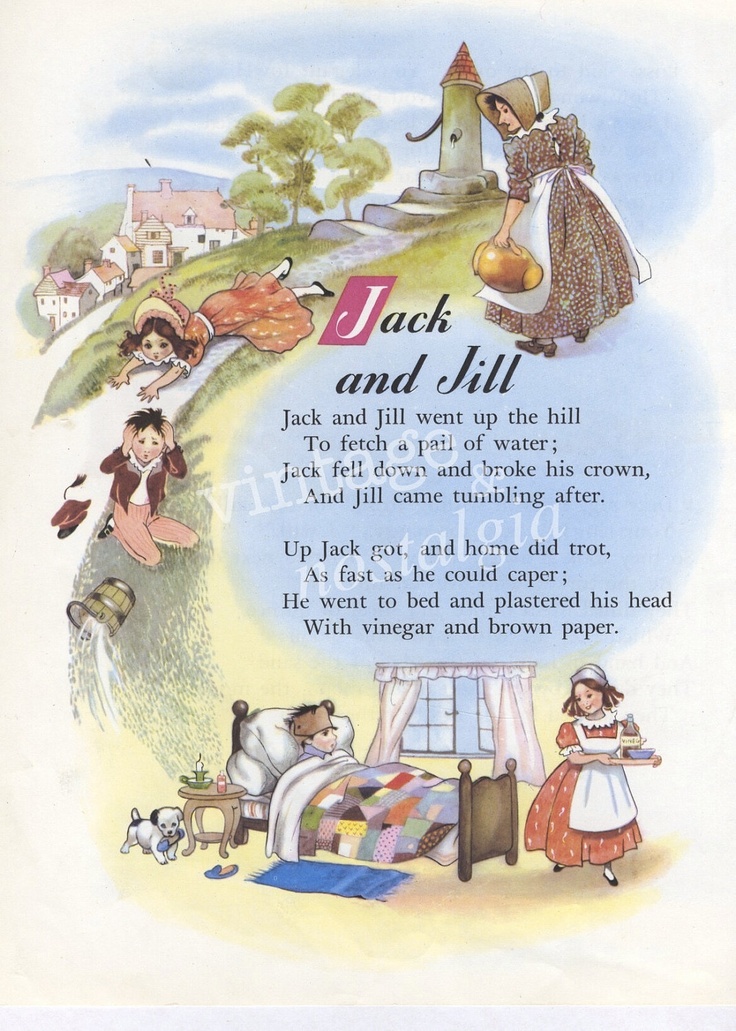

Jack and Jill went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water;

Jack fell down and broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

Up Jack got, and home did trot,

As fast as he could caper,

To old Dame Dob, who patched his nob

With vinegar and brown paper.

Summary

Is this the complete rhyme of ‘Jack and Jill’? That depends on when you read it, or where. The first stanza is by far the oldest, and seems to have been the sum total of the ‘Jack and Jill’ rhyme in the eighteenth century, when it’s first recorded. The second stanza appeared in the early nineteenth century when the vogue for chapbooks – short illustrated books containing extended versions of popular nursery rhymes – arose. (The chapbook for ‘Old Mother Hubbard’, for instance, was a huge bestseller in the first few decades of the nineteenth century.)

The word ‘crown’, by the way, almost certainly refers to Jack’s head (or the very top of it), rather than suggesting royal connotations (e. g. Jack is a prince or portraying a monarch of some sort). Jack and Jill are just an ordinary boy and girl (or young man and young woman, potentially).

g. Jack is a prince or portraying a monarch of some sort). Jack and Jill are just an ordinary boy and girl (or young man and young woman, potentially).

If you read one of these old chapbook versions, you encounter a ‘Jack and Jill’ rhyme that is a whopping fifteen stanzas long:

Then JILL came in,

And she did grin,

To see JACK’S paper plaster,

Her mother put her,

A fools cap on,

For laughing at Jack’s disaster.

This made JILL pout,

And she ran out,

And JACK did quickly follow,

They rode dog Ball,

Jill got a fall,

How Jack did laugh and hollow.

The DAME came out,

To know all about,

Jill said Jack made her tumble

,Says Jack I’ll tell,

You how she fell,

Then judge if she need grumble.

And so it goes on for another ten now-thoroughly-forgotten stanzas.

Thankfully for our purposes here, the most familiar version for modern readers is the two-stanza rendering quoted above. (Many readers will be familiar with an alternative version of that penultimate line, which reads ‘He went to bed to mend his head / With vinegar and brown paper. ’ Don’t worry, we’ll come to ‘nob’ in due course.)

’ Don’t worry, we’ll come to ‘nob’ in due course.)

Analysis

But although it was first written down in the eighteenth century, the original rhyme of Jack and Jill may be of a considerably older vintage. Iona and Peter Opie, in their endlessly informative and illuminating The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford Dictionary of Nusery Rhymes)

, suggest that the rhyming of ‘water’ with ‘after’ is a probable indication of the poem’s seventeenth-century origins, since it was common for ‘water’ (wahter) and ‘after’ (ahter) to sound remarkably and surprisingly similar in the 1600s, just as Shakespeare’s endless rhyming of ‘love’ with ‘move’ may not have been mere eye-rhyme but an indication that he, and his contemporaries, pronounced ‘move’ as muhve.

Jack and Jill as the generic names for a boy and girl (or man and woman) can be traced back to Shakespeare, of course, when Puck asserts in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: ‘Jack shall have Jill; / Nought shall go ill’. But does the nursery rhyme’s tale of a water-fetching trip gone awry (have you had an accident at work that wasn’t your fault?) hide any particular meaning?

But does the nursery rhyme’s tale of a water-fetching trip gone awry (have you had an accident at work that wasn’t your fault?) hide any particular meaning?

It’s worth mentioning the long-standing tradition of boys and girls rolling down Greenwich Hill on Whit Monday. The fact that a boy and a girl are involved in this hillside adventure does certainly suggest a romantic theme or subtext to the rhyme.

Theories about its origins

It’s almost inevitable that once a nursery rhyme attains a certain measure of fame, some exciting but far-fetched origin story will become attached to it, which endeavours to explain the rhyme’s origins in some historical figure or event, or in some myth or legend. And ‘Jack and Jill’ is no different.

The main culprit in the case of ‘Jack and Jill’ was Sabine Baring-Gould, who, when he wasn’t writing the words to the hymn ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ or forgetting what his own children looked like, was putting about exotic but unlikely stories concerning the origins of the ‘Jack and Jill’ nursery rhyme. In his Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (1866), Baring-Gould asserted that the rhyme ‘refers to the Eddaic Hjuki and Bil’.

In his Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (1866), Baring-Gould asserted that the rhyme ‘refers to the Eddaic Hjuki and Bil’.

In the Edda or Scandinavian myth that contains Hjuki and Bil, they are two children captured by Mani, the moon, while they were drawing water. The idea is that when we have a full moon, as the Opies summarise the myth, Hjuki and Bil can be seen with the bucket on a pole between them. But the tenuous similarity between the names, and the water-drawing connection, are appealing but not entirely conclusive. Mind you, sillier theories about classic nursery rhymes have been proposed.

In 2004, Chris Roberts, a librarian at the University of East London, suggested that ‘Jack and Jill’ is a story about two young people who lose their virginity together, with Jill conceiving a child (perhaps) and Jack running away from his new paternal responsibility. In Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme

, Roberts draws attention to the surprising presence of the word ‘nob’ in the second stanza of the nursery rhyme, or at least the version cited by the Opies (and the one we’ve reproduced above).

‘Nob’ has meant ‘head’ since the seventeenth century (a ‘nob-thatcher’ was a wigmaker, although it sounds like some sort of euphemism or slur), but as a slang word it’s more often applied to another part of the male anatomy. Why it should need patching by Dame Dob with vinegar and brown paper afterwards isn’t clear, and this interpretation is, again, interesting but not necessarily persuasive.

But then what is ‘Jack and Jill’ about? Sadly, we will probably never know for sure – assuming, that is, that the rhyme ever had an actual ‘meaning’. Many nursery rhymes originated as counting or dancing songs to be sung while children played a game together. But the fact that the nursery rhyme has attracted these two very different interpretations says something about our desire to understand and interpret these timeless children’s rhymes. But as for an ultimate meaning? That remains as elusive as ever.

About nursery rhymes

For most of us, nursery rhymes are the first poems we ever encounter in life. They can teach us about rhythm, and about constructing a story in verse, and, occasionally, they impart important moral lessons to us. Sometimes, though, they make no sense at all, and should be enjoyed purely as ‘nonsense’, as a forerunner to the Victorian nonsense verse so expertly practised by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll.

They can teach us about rhythm, and about constructing a story in verse, and, occasionally, they impart important moral lessons to us. Sometimes, though, they make no sense at all, and should be enjoyed purely as ‘nonsense’, as a forerunner to the Victorian nonsense verse so expertly practised by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll.

Some nursery rhymes appear to have emerged as simple rhymes to accompany counting or dancing games played by children. Sometimes, very specific historical subtexts for famous nursery rhymes have been proposed (many of them relating to the English Reformation of the sixteenth century, when King Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established the Church of England).

Many of these origin-myths turn out to be just that: myths, or retrospective attempts to find a deeper ‘meaning’ to rhymes which are, after all, children’s songs to be sung or chanted during play. For instance, the idea that the rhyme ‘Ring a Ring o’ Roses’ was written about the bubonic plague has been thoroughly debunked, as has the notion that ‘Humpty Dumpty’ was originally about a cannon in the English Civil War.

Discover the stories behind more classic nursery rhymes with our analysis of ‘London Bridge is Falling Down’, our commentary on the Little Bo Peep rhyme, and our post delving into the history of the ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ nursery rhyme.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

Image: Jack and Jill by William Wallace Denslow, via Wikimedia Commons.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Tags: Analysis, English Literature, History, Jack and Jill, Literary Criticism, Nursery Rhymes, Origins, Poetry, Summary

Literary lounge "Children's English rhymes"

We once heard - in the earliest childhood, heard and remembered for life the counting rhyme: month out of the fog, took out a knife from his pocket. ..

..

sighs as he walks...

For the English, acquaintance with poetry is also begins with similar nursery rhymes - nursery rhymes.

English nursery translates as nursery.

This refers to a separate room, which allocated for a small child. Rhyme's word literal translation - rhyme; it is included in combinations that represent different types poems:

game rhymes - game choruses, counting rhymes;

riddle rhymes

proverb rhymes - rhyming sayings.

Sometimes in Russian nursery rhymes the most fantastic things. For example: long-eared a pig made a nest on an oak tree.

English children also love this "nonsense"; their fables are called nonsense rhymes.

And here is the first fable: Jerry Hall.

Jerry Hall,

He is so small

A rat could eat him

Hat and all.

The next verse is an address to a boy Jack.

Jack be nimble,

Jack be quick

Jack jump over

The candlestick.

We see that Jack is the same "thumb boy", like Jerry in the previous stories. By the way, the name Jack is short for John.

You can't talk about boys all the time. Next rhyme - Betty Botta.

Betty Botta bought a bit of butter,

But she said: “This butter's bitter,

If I put it in my batter,

It will make my batter bitter.”

And in another rhyme we hear about adventures Jack and his friend Jill:

Jack and Jill went up the hill To fetch a pail of water;

Jack fell down and broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

After listening to the rhyme, one might think that Jack, fell and broke his crown. Yes, English crown translates both as a crown and as the top of the head, and, moreover, as the crown of a tree, a wreath, a crown and crest on the bird's head.

The next story is no less, and maybe even more dramatic than the previous one: there it was about a broken head, and here about love and jealousy.

Peter, Peter, pumpkin eater,

Had a wife and couldn't keep her.

He put her in a pumpkin shell

And there he kept her very well.

The next rhyme is about a crooked little man - known to us from the translation of Samuil Marshak:

Once upon a time there was a crooked man on the bridge,

He once walked a crooked mile...

He is also familiar to us from the translation of Korney Chukovsky:

There lived a man,

Crooked legs,

And he walked for a whole century

Down the crooked path...

The key word here is crooked crooked.

There was a crooked man,

And he walked a crooked mile,

He found a crooked sixpence

Against a crooked style.

He bought a crooked cat,

Which caught a crooked mouse,

And they all lived together

In a little crooked house.

So one person found the one and only coin, bought one cat that caught one mouse ... But if he found a whole treasure with coins? Then he would have bought many, many cats and they would have caught... But first he would have to count coins.

Six pence coins - sixpence - were in move until 1971, when England switched to a 10-digit system.

But the climb - stile is still "landmark" of the English village: these are 2-3 steps that allow the pedestrian overcome the fence.

Why not make a gate, leave pass?

Because through a passage or an unlocked gate yours can scatter over foreign fields horned-tailed creature.

Back to counting. Long time for learning counting in England, counting rhymes like this were used - about the girl Mary.

1, 2, 3, 4 -

Mary at the cottage door.

5, 6, 7, 8 -

Eating cherries off a plate.

And here is another rhyme:

One, two - look at your shoe,

Three, four - look at the door,

Five, six - look at the bricks,

Seven, eight - look at your plate,

Nine, ten - look at the pen,

Eleven, twelve - look at the shelf.

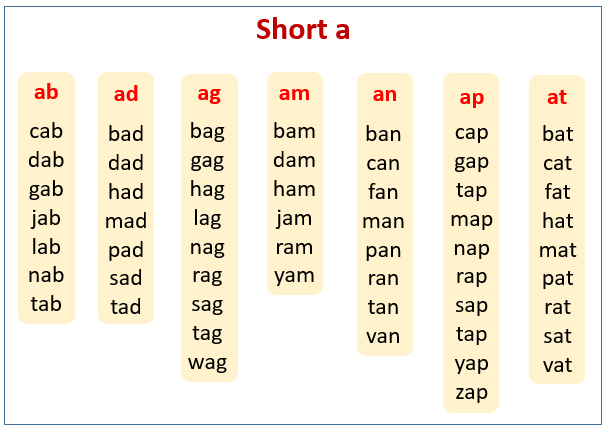

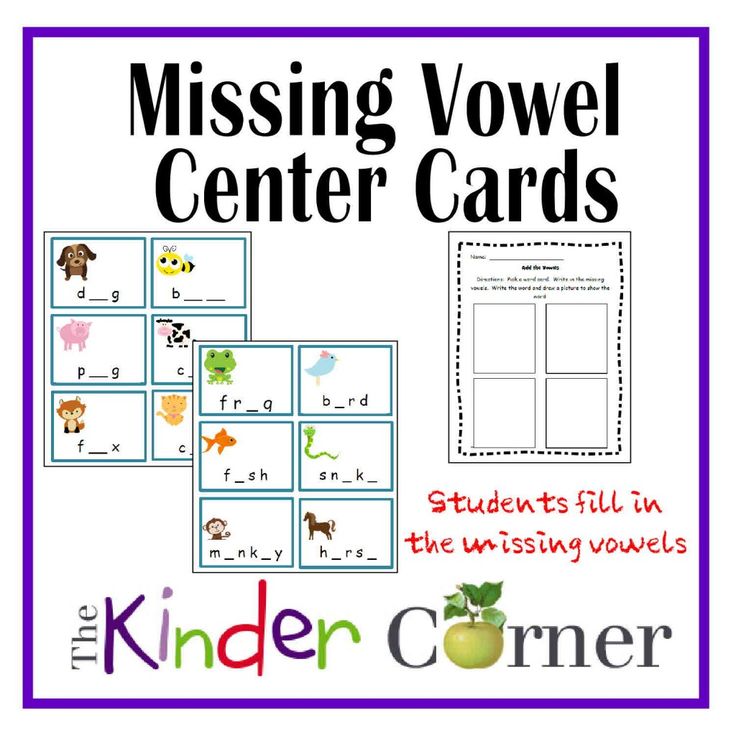

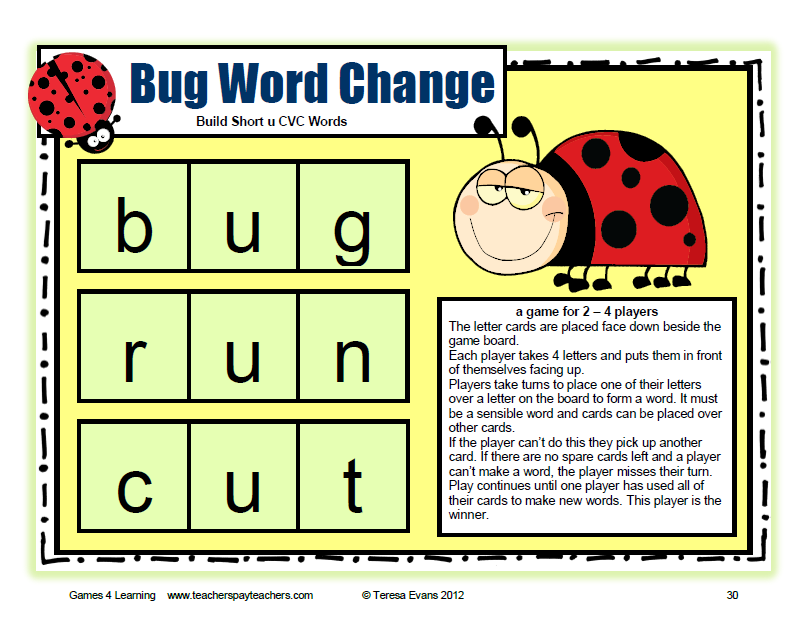

Some rhymes were invented in order to teach counting, others in order to remember alphabet.

Alphabet song “The ABC”.

There were also rhymes for memorizing the names of all days of the week. Agree, we sometimes “confused” Tuesday from Thursday.

Repeat all days of the week. For this we take scissors and along the way we will cut finger-nails.

Cut them on Monday, you cut them for health;

Cut them on Tuesday, you cut them for wealth.

Cut them on Wednesday, you cut them for news;

Cut them on Thursday, a new pair of shoes.

Cut them on Friday, you cut them for sorrow;

Cut them on Saturday, see your true love tomorrow.

Cut them on Sunday, the devil will be with you all

The week.

As you understand, this poem was written a very long time ago, at a time when people seriously believed in devils and witches, in heaven and hell. One from superstitions touched nails.

One from superstitions touched nails.

So, no work on Sunday: no bath, no haircut, care postpone the nails until Monday, Tuesday ... better until Saturday, which promises a meeting with loved ones.

Going to London, not bad consult with knowledgeable people: how is it in in general and in particular? They still go there left side? And the queen celebrates twice a year my birthday? Great Connoisseur of Parts royal customs is travel cat.

Pussy-cat, pussy-cat,

Where have you been?

I've been to London

To look at the Queen.

pussycat, pussycat,

Where did you there?

I frightened a mouse

under her chair.

And what is sitting on the hedge? Or rather, who such? This is Humpty Dumpty.

Humpty-Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty-Dumpty had a great fall;

All the King's horses and all the King's men

Couldn't put Humpty-Dumpty together again.

Climbing over the hedges, we reached village of Gotham, in Nottinghamshire. The inhabitants of this place have long been known "great sages".

Tells about 3 “wise men” from Gotem next verse:

Three wise men of Gotham

Went to sea in a bowl;

And if the bowl had been stronger,

My song would have been longer.

And finally, about the weather. The weather is one of the most conversational topics in England. Phrases about good or bad day often serve to fill awkward pauses. You should not complain about the weather - neither on the March wind, nor on the pouring rain.

March winds and April showers

Bring forth May flowers.

Some romantics claim that rain better than the sun, but the predominant part population in any country, prefers sun. In the next rhyme, the rain is driven away in side of Spain.

Rain, rain, go to Spain;

Come again another day:

When I brew and when I bake,

I'll give you a plum-cake.

Activity 9 structure0239

| stage no. | Stage | Tasks of the stage, types of activities. |

| 1. | Preliminary | Learning poems and songs on English lessons as phonetic exercises and speech warm-up. Selection of the best readers. Preparing a multimedia presentation. |

| 2. | Organizational | Preparing students for work (organizational moment), providing motivation (setting the goals of the event) |

3. |