How to learn by reading

How to Retain More of Every Book You Read

There are many benefits to reading more books, but perhaps my favorite is this: A good book can give you a new way to interpret your past experiences.

Whenever you learn a new mental model or idea, it's like the “software” in your brain gets updated. Suddenly, you can run all of your old data points through a new program. You can learn new lessons from old moments. As Patrick O'Shaughnessy says, “Reading changes the past.”1

Of course, this is only true if you internalize and remember insights from the books you read. Knowledge will only compound if it is retained. In other words, what matters is not simply reading more books, but getting more out of each book you read.

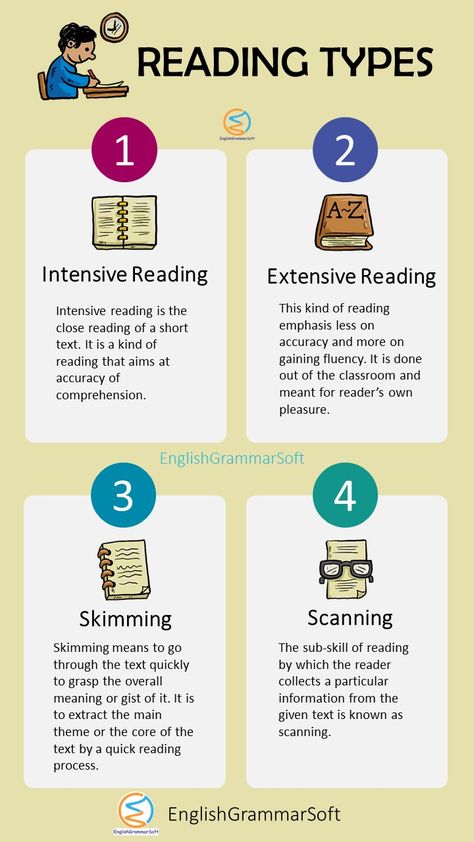

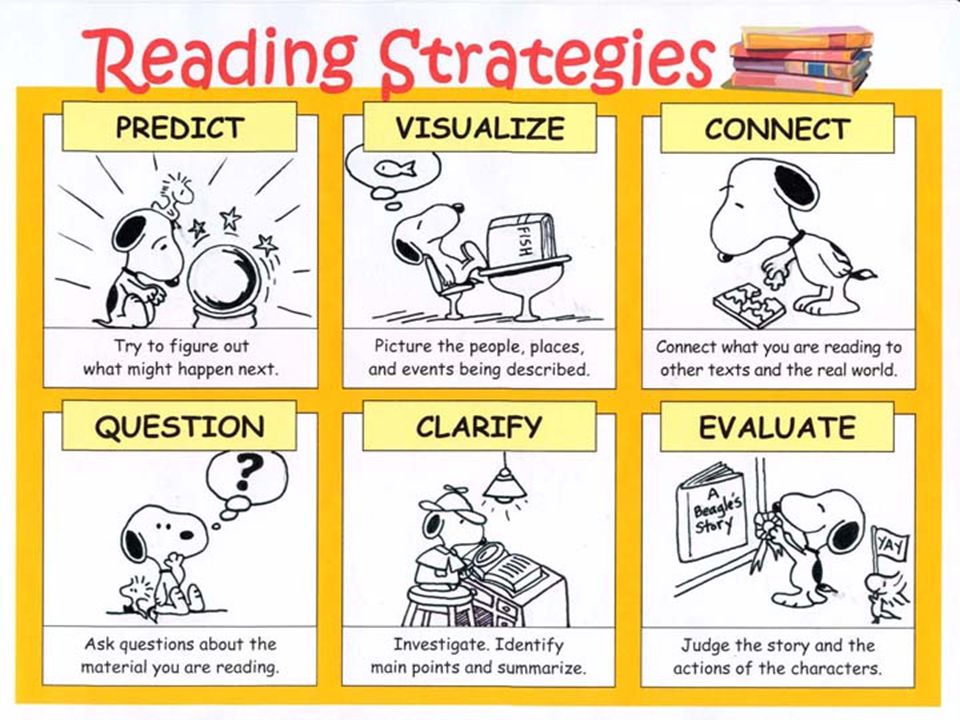

Gaining knowledge is not the only reason to read, of course. Reading for pleasure or entertainment can be a wonderful use of time, but this article is about reading to learn. With that in mind, I'd like to share some of the best reading comprehension strategies I’ve found.

1. Quit More Books

It doesn't take long to figure out if something is worth reading. Skilled writing and high-quality ideas stick out.

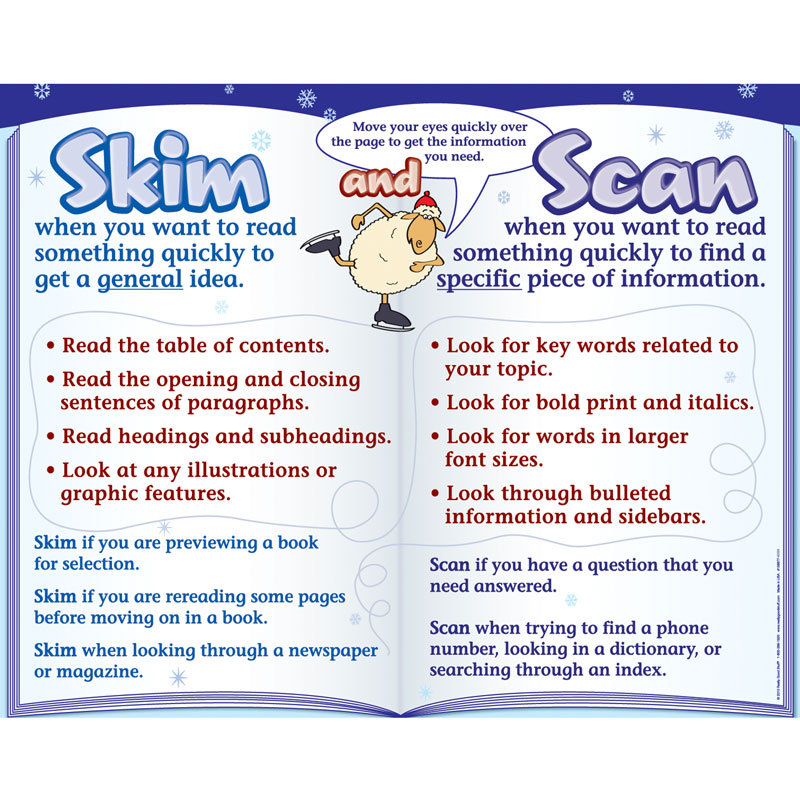

As a result, most people should probably start more books than they do. This doesn't mean you need to read each book page-by-page. You can skim the table of contents, chapter titles, and subheadings. Pick an interesting section and dive in for a few pages. Maybe flip through the book and glance at any bolded points or tables. In ten minutes, you'll have a reasonable idea of how good it is.

Then comes the crucial step: Quit books quickly and without guilt or shame.

Life is too short to waste it on average books. The opportunity cost is too high. There are so many amazing things to read. I think Patrick Collison, the founder of Stripe, put it nicely when he said, “Life is too short to not read the very best book you know of right now.”

Here's my recommendation:

Start more books. Quit most of them. Read the great ones twice.

2. Choose Books You Can Use Instantly

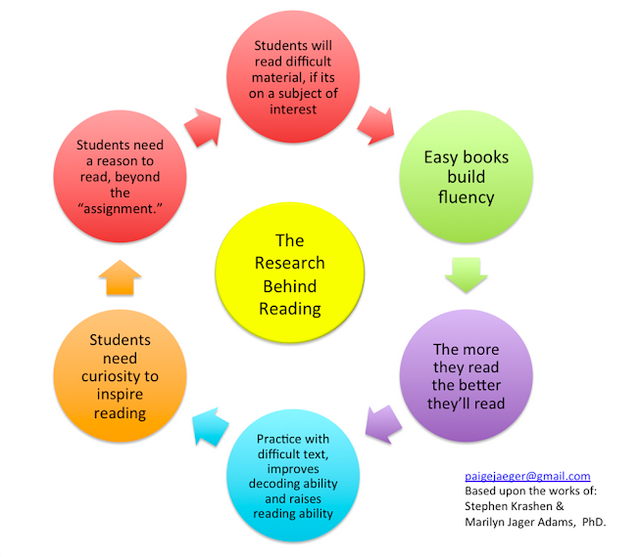

One way to improve reading comprehension is to choose books you can immediately apply. Putting the ideas you read into action is one of the best ways to secure them in your mind. Practice is a very effective form of learning.

Choosing a book that you can use also provides a strong incentive to pay attention and remember the material. That’s particularly true when something important hangs in the balance. If you’re starting a business, for example, then you have a lot of motivation to get everything you can out of the sales book you’re reading. Similarly, someone who works in biology might read The Origin of Species more carefully than a random reader because it connects directly to their daily work. 2

Of course, not every book is a practical, how-to guide that you can apply immediately, and that's fine. You can find wisdom in many different books. But I do find that I'm more likely to remember books that are relevant to my daily life.

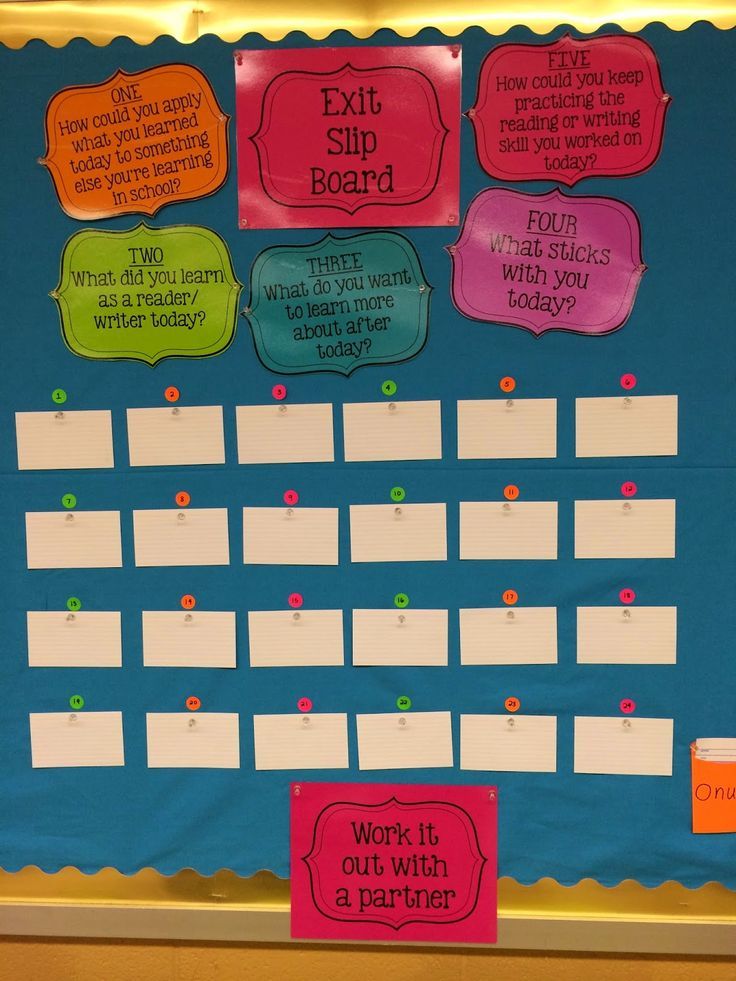

3. Create Searchable Notes

Keep notes on what you read. You can do this however you like. It doesn't need to be a big production or a complicated system. Just do something to emphasize the important points and passages.

I do this in different ways depending on the format I'm consuming. I highlight passages when reading on Kindle. I type out interesting quotes as I listen to audiobooks. I dog-ear pages and transcribe notes when reading a print book.

But here's the real key: store your notes in a searchable format.

There is no need to leave the task of reading comprehension solely up to your memory. I keep my notes in Evernote. I prefer Evernote over other options because 1) it is instantly searchable, 2) it is easy to use across multiple devices, and 3) you can create and save notes even when you're not connected to the internet.

I get my notes into Evernote in three ways:

I. Audiobook: I create a new Evernote file for each book and then type my notes directly into that file as I listen.

II. Ebook: I highlight passages on my Kindle Paperwhite and use a program called Clippings to export all of my Kindle highlights directly into Evernote. Then, I add a summary of the book and any additional thoughts before posting it to my book summaries page.

III. Print: Similar to my audiobook strategy, I type my notes as I read. If I come across a longer passage I want to transcribe, I place the book on a book stand as I type. (Typing notes while reading a print book can be annoying because you are always putting the book down and picking it back up, but this is the best solution I've found.)

Of course, your notes don't have to be digital to be “searchable.” For example, you can use Post-It Notes to tag certain pages for future reference. As another option, Ryan Holiday suggests storing each note on an index card and categorizing them by the topic or book.

The core idea is the same: Keeping searchable notes is essential for returning to ideas easily. An idea is only useful if you can find it when you need it.

An idea is only useful if you can find it when you need it.

4. Combine Knowledge Trees

One way to imagine a book is like a knowledge tree with a few fundamental concepts forming the trunk and the details forming the branches. You can learn more and improve reading comprehension by “linking branches” and integrating your current book with other knowledge trees.

For example:

- While reading The Tell-Tale Brain by neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, I discovered that one of his key points connected to a previous idea I learned from social work researcher Brené Brown.

- In my notes for The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, I noted how Mark Manson's idea of “killing yourself” overlaps with Paul Graham's essay on keeping your identity small.

- As I read Mastery by George Leonard, I realized that while this book was about the process of improvement, it also shed some light on the connection between genetics and performance.

I added each insight to my notes for that particular book.

Connections like these help you remember what you read by “hooking” new information onto concepts and ideas you already understand. As Charlie Munger says, “If you get into the mental habit of relating what you’re reading to the basic structure of the underlying ideas being demonstrated, you gradually accumulate some wisdom.”

When you read something that reminds you of another topic or immediately sparks a connection or idea, don’t allow that thought to come and go without notice. Write about what you’ve learned and how it connects to other ideas.

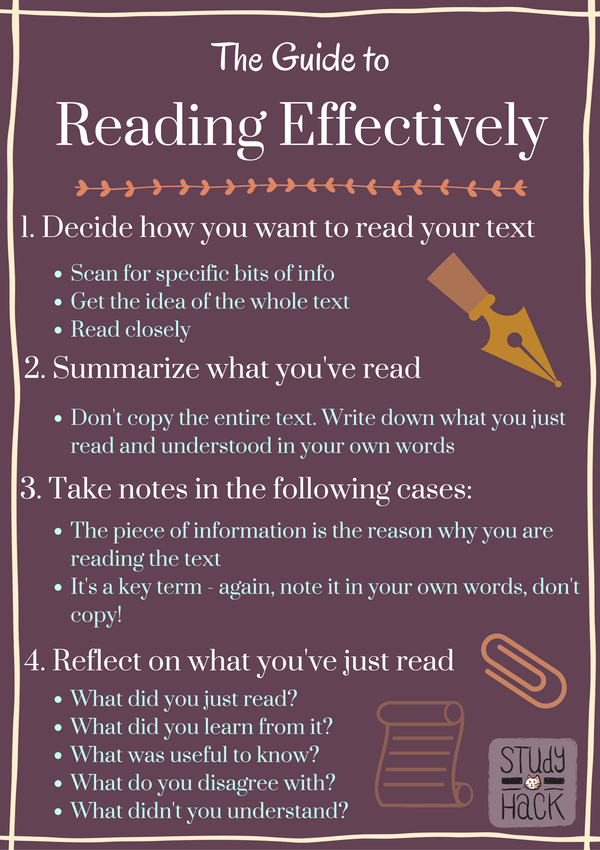

5. Write a Short Summary

As soon as I finish a book, I challenge myself to summarize the entire text in just three sentences. This constraint is just a game, of course, but it forces me to consider what was really important about the book.

Some questions I consider when summarizing a book include:

- What are the main ideas?

- If I implemented one idea from this book right now, which one would it be?

- How would I describe the book to a friend?

In many cases, I find that I can usually get just as much useful information from reading my one-paragraph summary and reviewing my notes as I would if I read the entire book again. 3

3

If you feel like you can’t squeeze the whole book into three sentences, consider using the Feynman Technique.

The Feynman Technique is a note-taking strategy named after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. It’s pretty simple: Write the name of the book at the top of a blank sheet of paper, then write down how you’d explain the book to someone who had never heard of it.

If you find yourself stuck or if you see that there are holes in your understanding, review your notes or go back to the text and try again. Keep writing it out until you have a good handle on the main ideas and feel confident in your explanation.

I’ve found that almost nothing reveals gaps in my thinking better than writing about an idea as if I am explaining it to a beginner. Ben Carlson, a financial analyst, says something similar, “I find the best way to figure out what I’ve learned from a book is to write something about it.” 4

6. Surround the Topic

I often think of the quote by Thomas Aquinas, “Beware the man of a single book. ”

”

If you only read one book on a topic and use that as the basis for your beliefs for an entire category of life, well, how sound are those beliefs? How accurate and complete is your knowledge?

Reading a book takes effort, but too often, people use one book or one article as the basis for an entire belief system. This is even more true (and more difficult to overcome) when it comes to using our one, individual experience as the basis for our beliefs. As Morgan Housel noted, “Your personal experiences make up maybe 0.00000001% of what's happened in the world but maybe 80% of how you think the world works. We're all biased to our own personal history.” 5

One way to attack this problem is to read a variety of books on the same topic. Dig in from different angles, look at the same problem through the eyes of various authors, and try to transcend the boundary of your own experience.

7. Read It Twice

I'd like to finish by returning to an idea I mentioned near the beginning of this article: read the great books twice. The philosopher Karl Popper explained the benefits nicely, “Anything worth reading is not only worth reading twice, but worth reading again and again. If a book is worthwhile, then you will always be able to make new discoveries in it and find things in it that you didn’t notice before, even though you have read it many times.”

The philosopher Karl Popper explained the benefits nicely, “Anything worth reading is not only worth reading twice, but worth reading again and again. If a book is worthwhile, then you will always be able to make new discoveries in it and find things in it that you didn’t notice before, even though you have read it many times.”

Additionally, revisiting great books is helpful because the problems you deal with change over time. Sure, when you read a book twice maybe you'll catch some stuff you missed the first time around, but it's more likely that new passages and ideas will be relevant to you. It's only natural for different sentences to leap out at you depending on the point you are at in life.

You read the same book, but you never read it the same way. As Charles Chu noted, “I always return home to the same few authors. And, no matter how many times I return, I always find they have something new to say.” 6

Of course, even if you didn't get something new out of each reading, it would still be worthwhile to revisit great books because ideas need to be repeated to be remembered. The writer David Cain says, “When we only learn something once, we don’t really learn it—at least not well enough for it to change us much. It may inspire momentarily, but then becomes quickly overrun by the decades of habits and conditioning that preceded it.”7 Returning to great ideas cements them in your mind.

The writer David Cain says, “When we only learn something once, we don’t really learn it—at least not well enough for it to change us much. It may inspire momentarily, but then becomes quickly overrun by the decades of habits and conditioning that preceded it.”7 Returning to great ideas cements them in your mind.

Nassim Taleb sums things up with a rule for all readers: “A good book gets better at the second reading. A great book at the third. Any book not worth rereading isn’t worth reading.”

Where to Go From Here

Knowledge compounds over time.

In Chapter 1 of Atomic Habits, I wrote: “Learning one new idea won’t make you a genius, but a commitment to lifelong learning can be transformative.”

One book will rarely change your life, even if it does deliver a lightbulb moment of insight. The key is to get a little wiser each day.

Now that you know how to get more out of each book you read, you might be looking for some reading recommendations. Feel free to check out my book summaries or my public reading list.

Footnotes

See tweet on December 2, 2016.

I'd like to acknowledge Simon Eskildsen, who also wrote about the idea of choosing books that are relevant to your interests and current life circumstances. You can read his thoughts on reading here.

Writing about a book also forces you to practice spaced repetition. Maybe you started reading a book a few days ago and writing a summary a few days later is a natural way to employ “spaced repetition” and reinforce the concepts.

“How To Read” by Morgan Housel

“Ideas That Changed My Life” by Morgan Housel

It’s Okay to “Forget” What You Read by Charles Chu

“If It's Important, Learn It Repeatedly” by David Cain

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

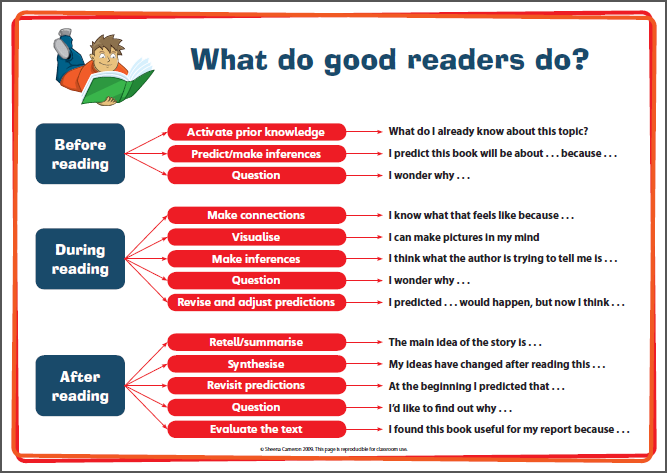

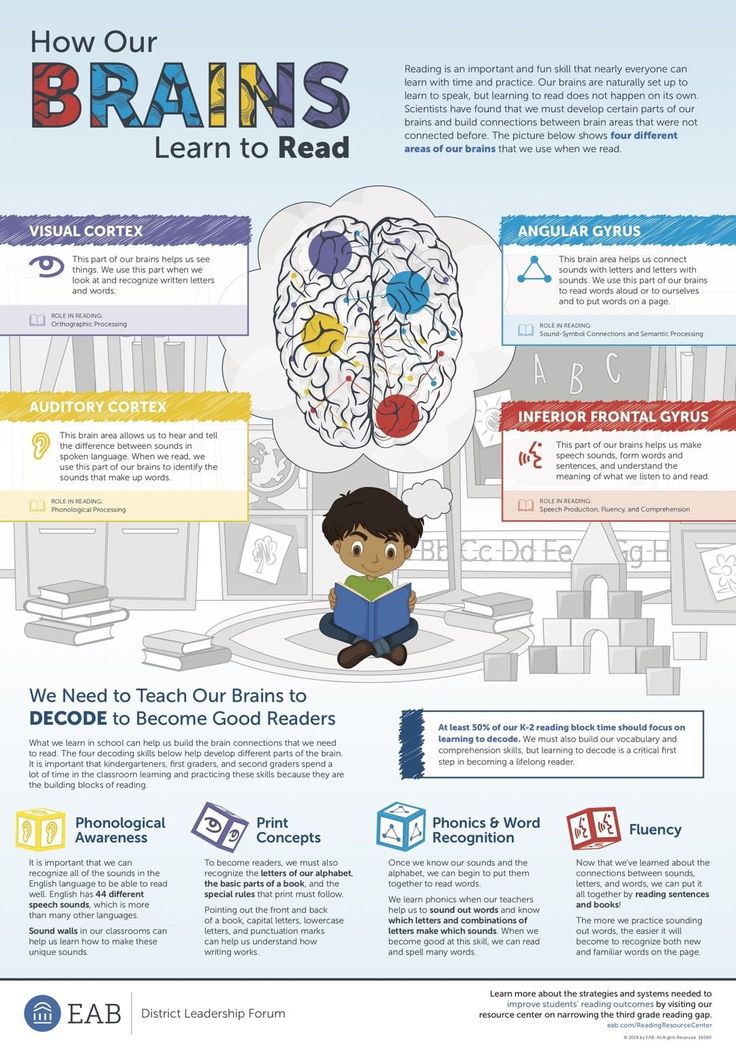

How do kids actually learn how to read?

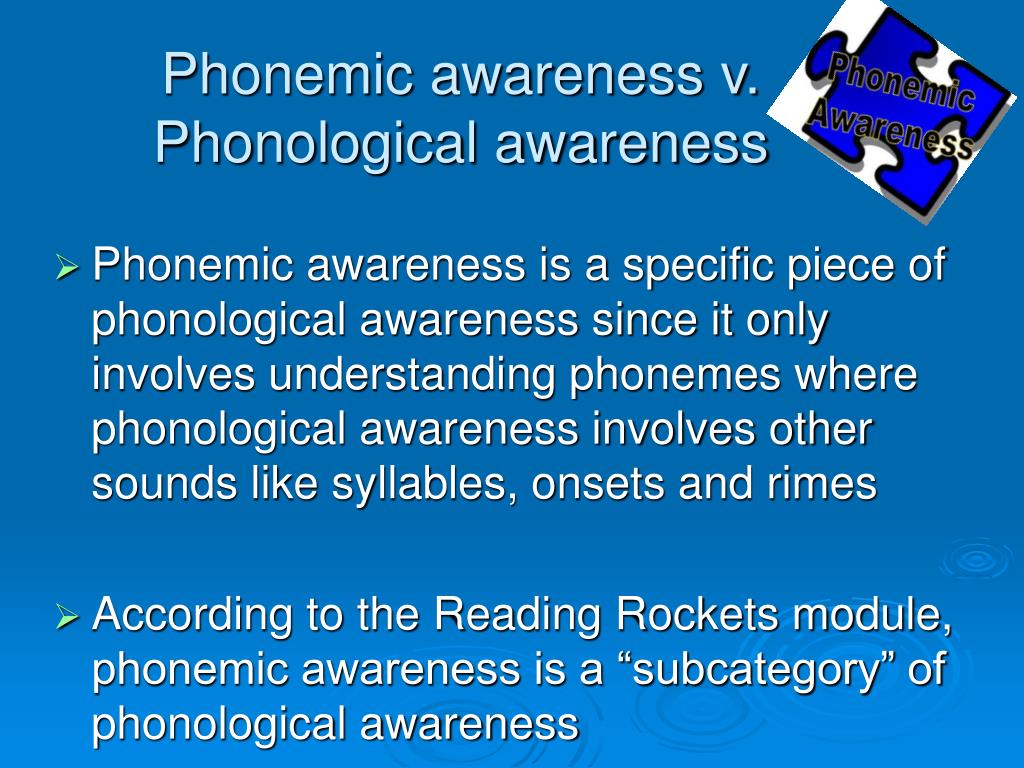

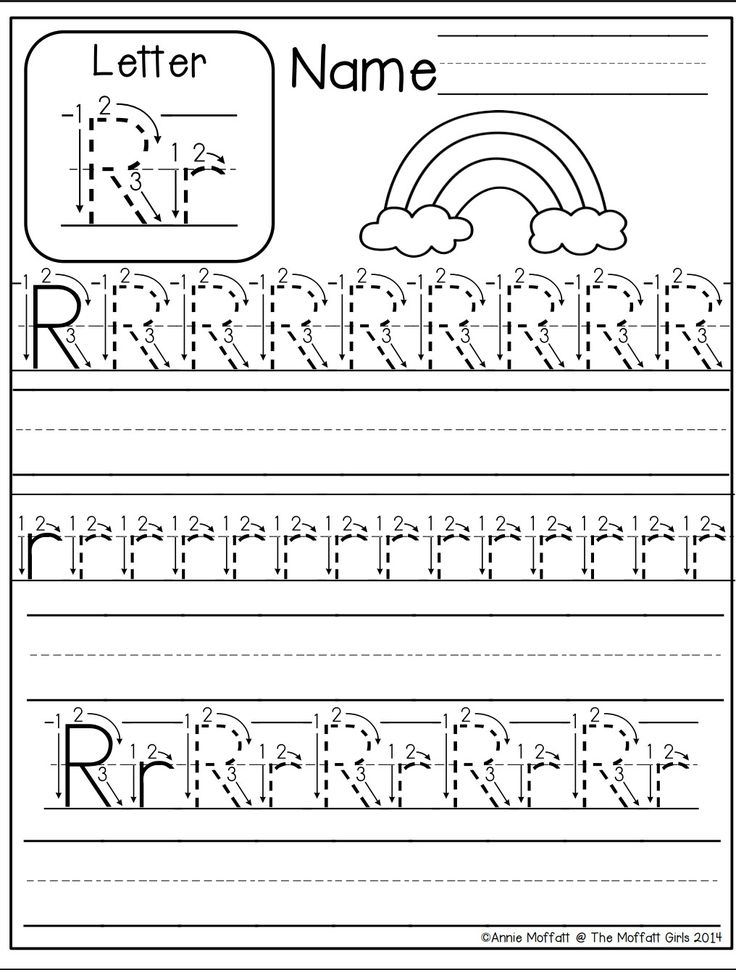

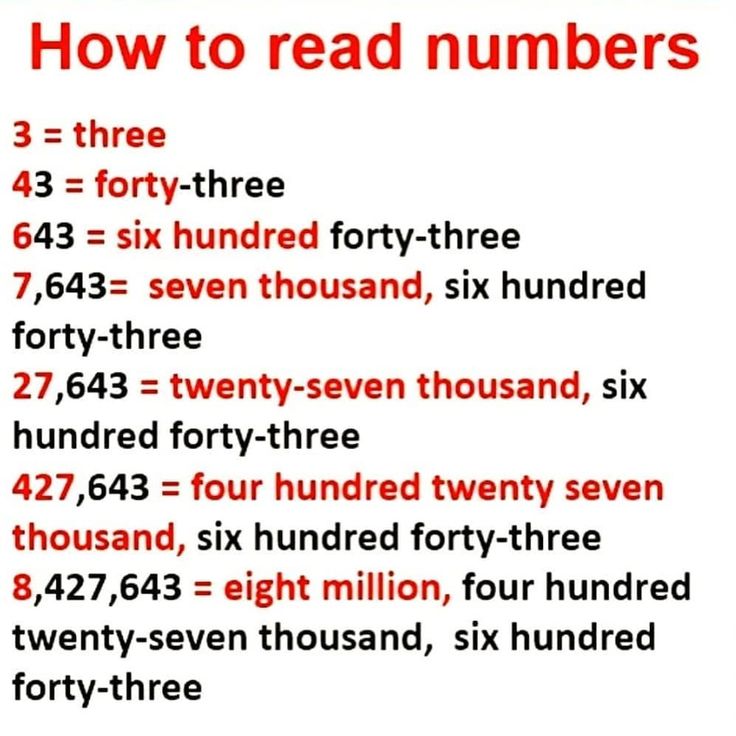

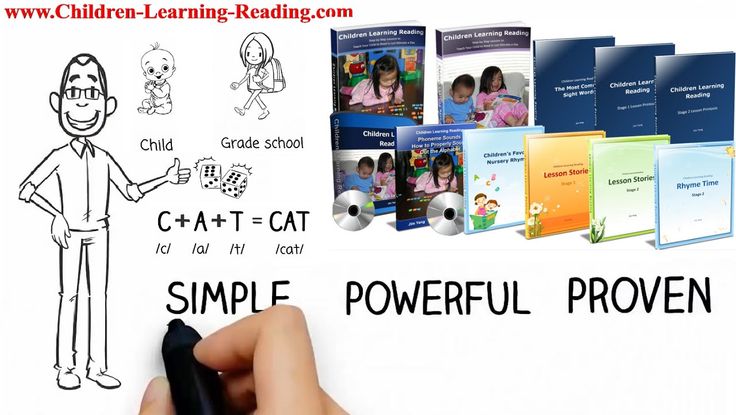

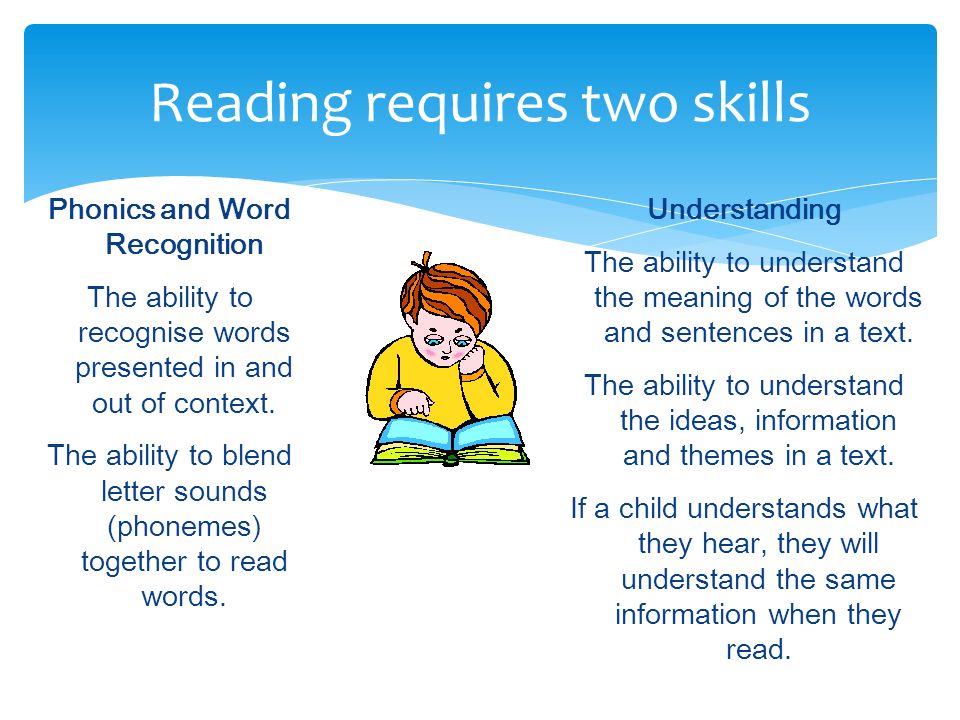

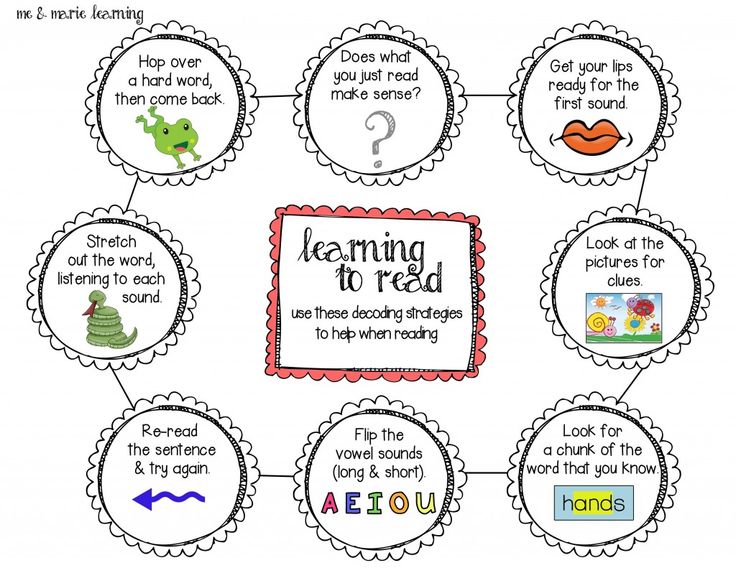

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

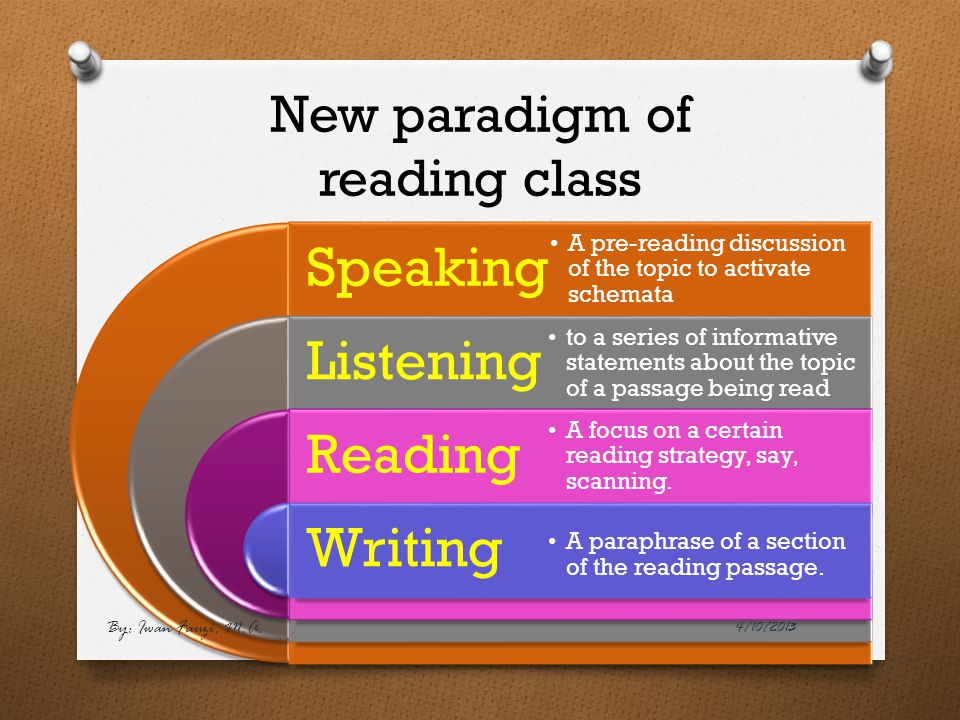

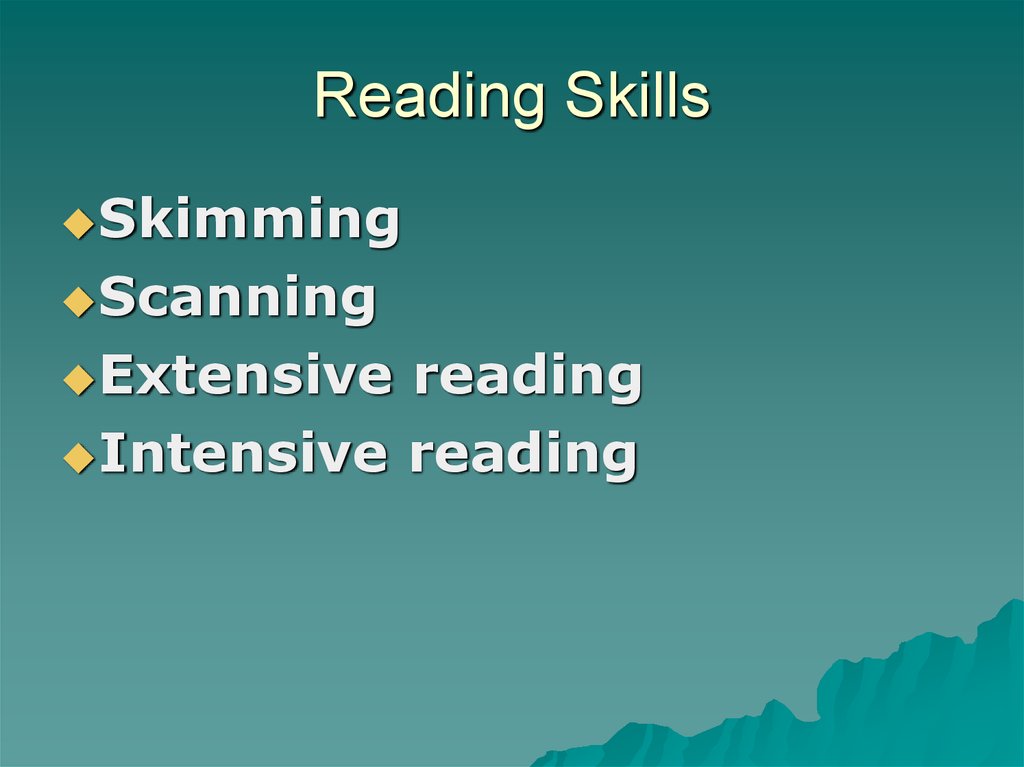

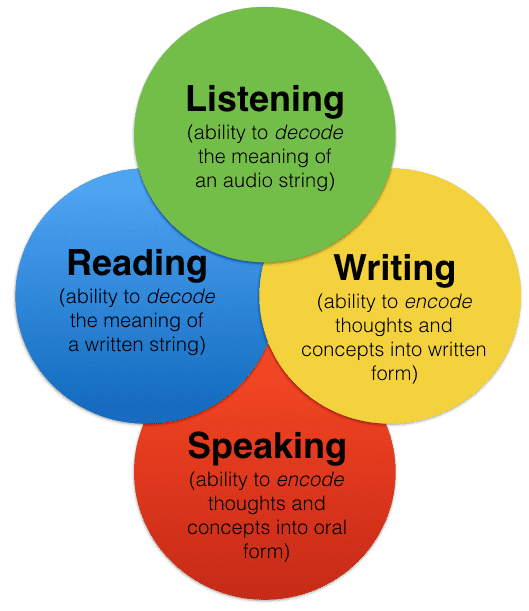

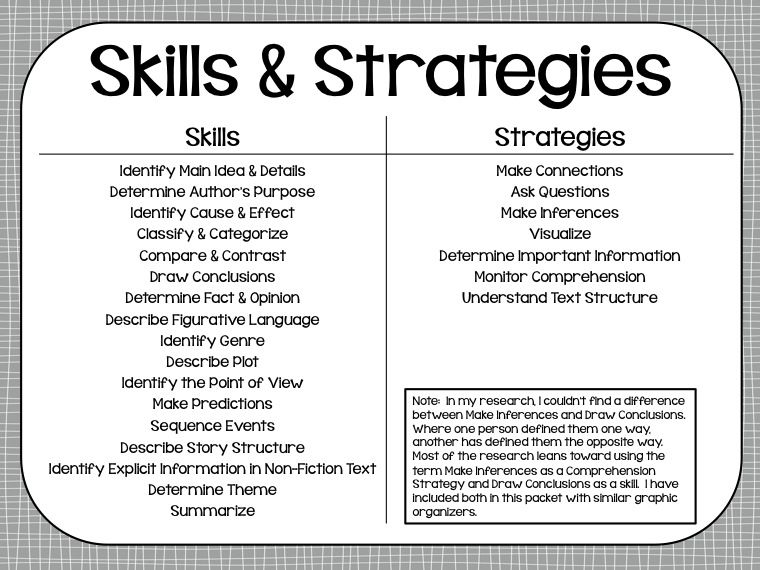

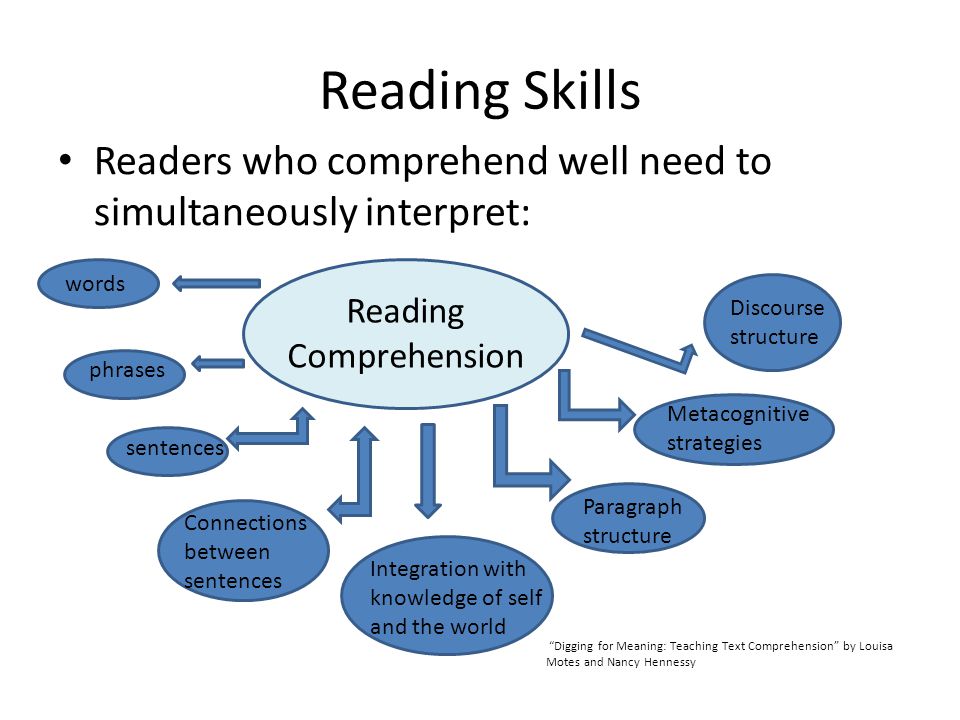

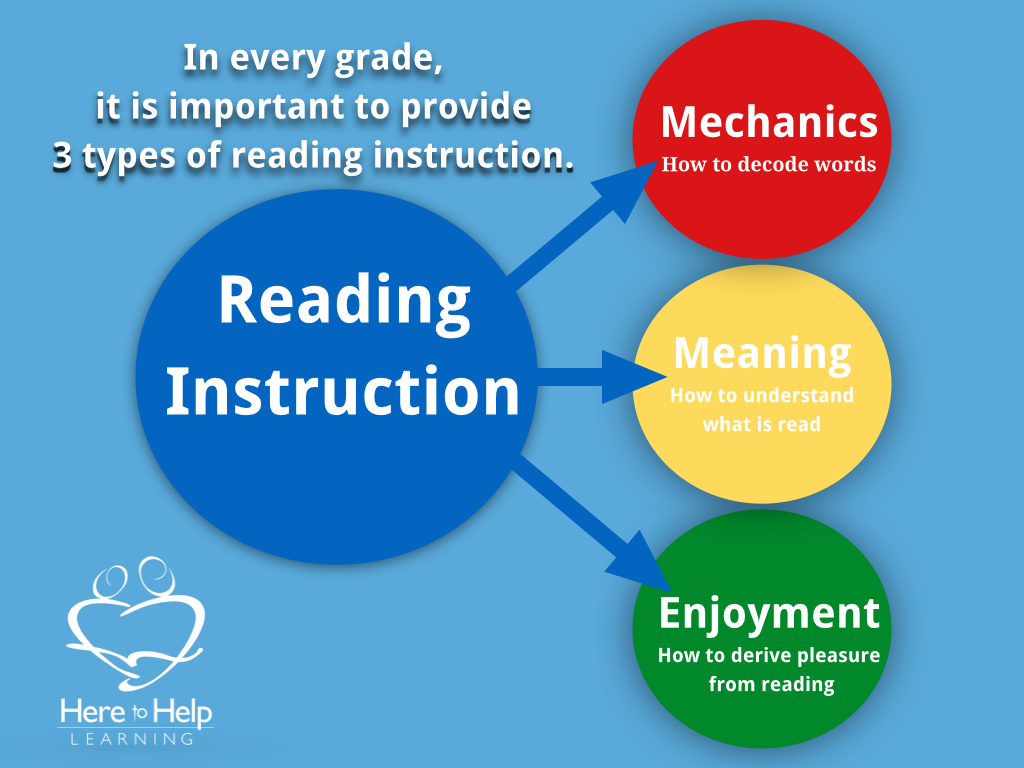

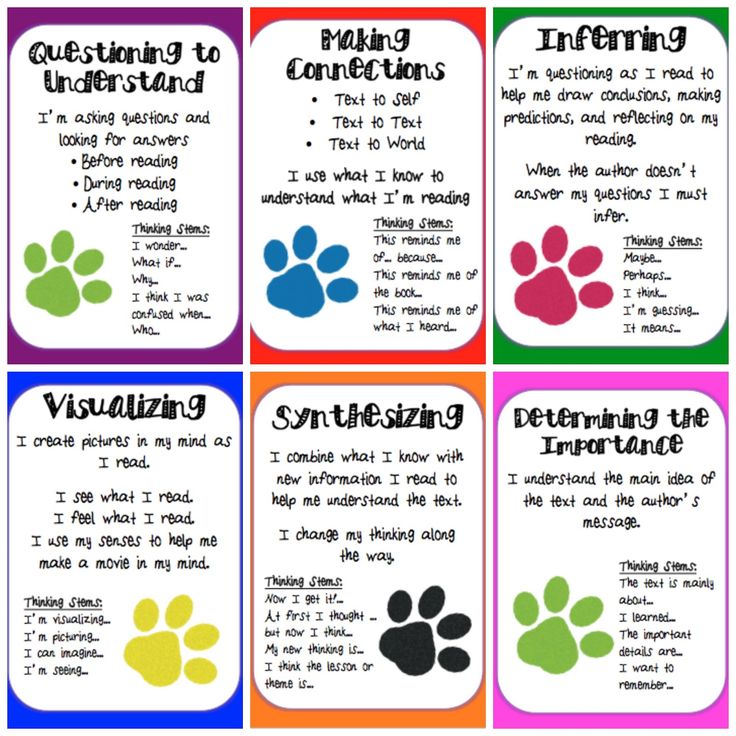

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

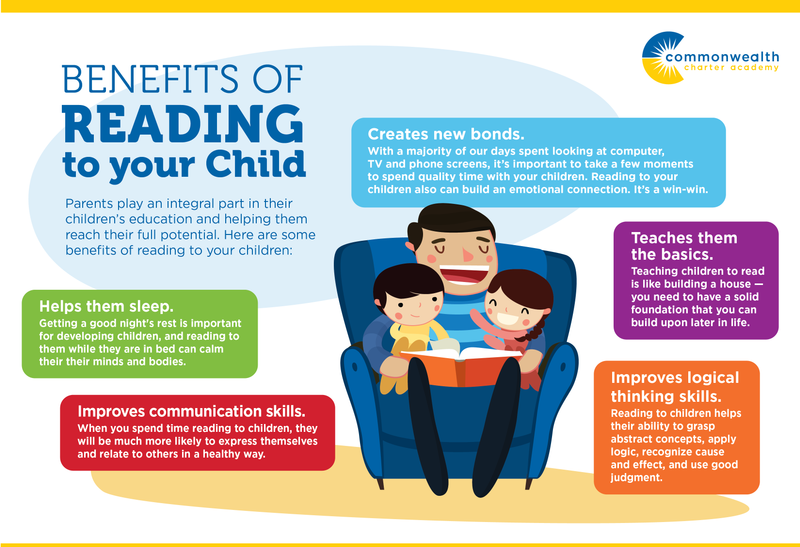

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

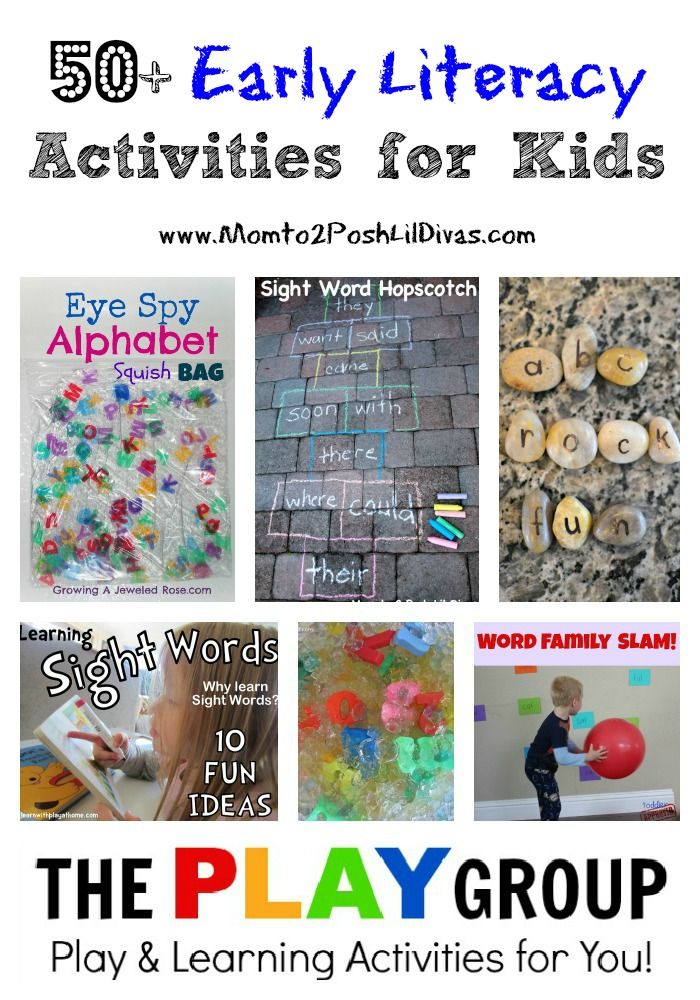

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

how to read books as efficiently as possible

American philosopher Mortimer Adler believed that learning to read is not an easy task that requires patience, rigor and lack of vanity (reading a book for the sake of an Instagram photo is not immediately possible). First you need to determine what problems the author is trying to solve, then find out exactly how he does it, and only then move on to criticism and subjective assessments. T&P publishes an excerpt from Adler's Guide to Reading on how to learn to read non-fiction.

How to read books. Great Reading Guide

Mortimer Adler

Mann, Ivanov and Ferber. 2019

Ways of reading

[…] First of all, you must master what is offered as knowledge. Then you need to decide if this knowledge is acceptable to you. In other words, the first task is to understand the book, and the second is to be critical of it . In the future, you will see more than once that they differ significantly.

Then you need to decide if this knowledge is acceptable to you. In other words, the first task is to understand the book, and the second is to be critical of it . In the future, you will see more than once that they differ significantly.

The process of understanding can also be divided into components. To understand a book, you first need to learn to perceive it as a structured whole, and then as an object that has a complex of linguistic and semantic units.

So there are three different ways of reading.

I. The first method is structural or analytical. At the same time, the reader moves from the whole to the particular.

II. The second way is interpretative or synthetic. Here the reader moves from the particular to the whole.

III. The third way is critical, or evaluative. The reader evaluates the author and decides whether he agrees with his point of view.

Each of the three main methods involves the performance of several actions, which means that they take into account several rules. Three rules of the second way of reading: 1) discover and interpret the most important words in the book; 2) do the same with the most important sentences , and 3) do the same with paragraphs containing the main provisions. The fourth - and last - rule is this: you need to find out what problems the author has solved in this book, and what problems he has not coped with.

Three rules of the second way of reading: 1) discover and interpret the most important words in the book; 2) do the same with the most important sentences , and 3) do the same with paragraphs containing the main provisions. The fourth - and last - rule is this: you need to find out what problems the author has solved in this book, and what problems he has not coped with.

To read this or that text in the first way, you must: 1) know what kind of book you are reading, that is, understand its main subject. Next, you need to realize: 2) what is the main meaning of the book; 3) what semantic or structural parts it is divided into, and 4) what main problems the author seeks to solve. This method also contains four actions and four rules.

Please note that the parts you single out as a result of the analysis of the whole on the first reading will not necessarily coincide with those parts from which you will form a holistic view on the second reading. In the first case, they will become a set of factors that characterize the author's attitude to the subject or problem. In the second, they will turn out to be terms, judgments and syllogisms, that is, thoughts, statements and arguments of the author.

In the first case, they will become a set of factors that characterize the author's attitude to the subject or problem. In the second, they will turn out to be terms, judgments and syllogisms, that is, thoughts, statements and arguments of the author.

The third way of reading also involves certain steps. There are several general rules for forming a critical opinion and four important actions associated with them. The rules of the third way of reading explain what you should pay attention to. […]

Knowing what the meaning of the book as a whole is and what its main components are, it is always easier to isolate the main terms and statements. If you were able to understand the key points and arguments of the author, it will be easier for you to identify the meaning of his words and the main structural units.

In the first way of reading, at the very beginning it is necessary to identify the problem or problems that the author seeks to solve. The last step in the second way of reading should be understanding whether the author has solved his problems and what questions he managed to find answers to. You see that these methods are closely interconnected and are combined at the final stage.

You see that these methods are closely interconnected and are combined at the final stage.

As you develop your skill, you will learn to read in two ways at the same time. The better you get at this, the more one method will contribute to the application of the other. But the third way can never accompany the other two. Even the most experienced reader has to somehow separate the first two ways and the third.

Understanding the position of the author always precedes criticism or evaluation of his text.

Critics, not readers

I have met many "readers" who started with the third method, sometimes ignoring the first and second altogether. They picked up a book and soon confidently told what was wrong with it. They were simply bursting with a sense of their own importance, and therefore the book in their arsenal became just an excuse for narcissism. It is hardly possible to call such people readers. Rather, it would be more correct to rank them among those who consider conversation an occasion for self-affirmation and monologue. It makes no sense to talk to these people, it is usually not worth listening to them either.

It makes no sense to talk to these people, it is usually not worth listening to them either.

The first two ways of reading can be combined because they are aimed at understanding the book. The third is distinguished by the fact that it involves criticism after understanding has occurred. Nevertheless, the combination of the first two ways leaves the reader the opportunity to identify and separate them at any time, which is very important. You can check your way of reading by decomposing the whole process into components. You may need to revise it step by step, although by then it will be perceived as a whole, as the process of reading will become a habit.

In this regard, it is important to remember that the various rules always remain autonomous, even when, in your understanding, the boundaries between them are blurred, forming a single complex skill. If you cannot access each of these rules separately, it will interfere with the reading process as a whole. So, an English teacher, checking a student's work and explaining his notes, always points out a violation of one or another specific rule. At the same time, the student must remember all the rules, but at the same time, the teacher does not want his student to check their complete list at every step. He wants the ability to write well becomes a habit in the student, so that the rules become an integral part of his intellectual baggage. The same goes for reading.

At the same time, the student must remember all the rules, but at the same time, the teacher does not want his student to check their complete list at every step. He wants the ability to write well becomes a habit in the student, so that the rules become an integral part of his intellectual baggage. The same goes for reading.

Source: ilbusca / istockphoto.com

Seeing relationships

But one more difficulty remains. Being able to read a book in three ways is not enough - it is important to learn how to read several related books in order to master any of them qualitatively. I'm not saying that one should learn to "handle" any combination of books qualitatively. We are talking only about interconnected books that are united by a common meaning or deal with the same problems. If you don't know how to "coherently" read such books, then you probably won't be able to master any of them properly. The authors express the same idea, agree with each other or argue, but where is the guarantee that you understand at least one of them without seeing the coincidences and differences in their opinions?

Here you need to fix the difference between limited and extended reading. I hope that these words will not mislead you. I cannot put it differently. I call limited the reading of the book itself, without any connection with other sources. Extended reading is the study of a book in the context of other books related to it by a common meaning. Sometimes this is just reference literature, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, almanacs. Sometimes - secondary books, that is, useful comments and digests. Sometimes great books become contextual. In addition, such reading is often aided by relevant experience, which we refer to in order to understand the book. It can be both laboratory and vital, purchased daily. Limited and extended reading are usually combined in the actual process of understanding or even critiquing the same book.

I hope that these words will not mislead you. I cannot put it differently. I call limited the reading of the book itself, without any connection with other sources. Extended reading is the study of a book in the context of other books related to it by a common meaning. Sometimes this is just reference literature, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, almanacs. Sometimes - secondary books, that is, useful comments and digests. Sometimes great books become contextual. In addition, such reading is often aided by relevant experience, which we refer to in order to understand the book. It can be both laboratory and vital, purchased daily. Limited and extended reading are usually combined in the actual process of understanding or even critiquing the same book.

Everything I have said about the ability to read related books applies especially to great books. In my lectures on education, I often refer to them. Usually after that, students write to me with a request to provide them with a list of such books. I recommend using the list published by the American Library Association called "Western Classics" or the list published by St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland. Later, my listeners report that reading these books turns out to be an extremely difficult process for them. The excitement that prompted them to find this list and start reading is often replaced by a hopeless feeling of powerlessness.

I recommend using the list published by the American Library Association called "Western Classics" or the list published by St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland. Later, my listeners report that reading these books turns out to be an extremely difficult process for them. The excitement that prompted them to find this list and start reading is often replaced by a hopeless feeling of powerlessness.

There are two reasons for this. The first, of course, is that they do not know how to read correctly. But that's not all. The second reason lies in the conceit of readers - they are convinced that they will be able to understand the first book they choose without studying others that are closely related to it. They were probably trying to read the Federalist Papers without paying attention to the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution. Or intended to read all this without thinking [French writer, philosopher and jurist Charles-Louis] Montesquieu "On the Spirit of Laws", "The Social Contract" [French writer, thinker, composer Jean-Jacques] Rousseau or John Locke's essay on civil government❓ Available referring to the book "Two Treatises on Government", in which Locke outlined his concept of the socio-political structure, which influenced the formation of the principles of American statehood. — Note T&P .

— Note T&P .

In step with the times

Great books are not only interconnected. We must not forget that they were written in a certain sequence, which must be taken into account in the reading process. Obviously, the later author was influenced by the predecessor writer. Reading a book by an earlier author first will help you understand a later book.

Reading books in their relationship and in chronological order is the basic rule of extended reading.

[…] There is one limitation in the application of all these rules, which you might have already guessed. I have repeatedly emphasized that their purpose is to help you read book in its entirety . At least the main goal. It would be a mistake to use these rules primarily for reading passages out of context. You can't learn to read by spending fifteen minutes a day on a book, as the Harvard Classics Handbook says ❓Harvard Business Review Classics book series featuring the best articles from the Harvard Business Review. — Note T&P .

— Note T&P .

The point is not that fifteen minutes a day is not enough, but that one should not read a little, as the guide recommends. On the Five Foot Shelf❓The informal name of the Harvard Classics literary series, which includes 418 works of world literature recognized as the foundation of liberal arts education in the United States. The books were selected by Dr. Charles Eliot, President of Harvard University.— Note. T&P you can find many great books, but among them there are also quite banal works. In most cases, the texts of the books in this series are published in full, but sometimes there are just large passages. But no one recommends studying the book in its entirety or reading any part of it. Therefore, you are invited to gather some nectar there, sniff some honey here. Fine, but this way you will become an ordinary literary butterfly, and not an experienced reader.

For example, today you will read six pages of Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, tomorrow eleven pages of the early poems of Milton, and the day after tomorrow ten pages of Cicero's On Friendship. ". Next, you will study eight pages of Hamilton from the Federalist Papers, then fifteen-page notes by Edmund Burke, and twelve more pages from Rousseau's Essay on Inequality. The only thing that will determine the sequence of your reading in this case is the historical connection between any passage and a certain day of the week. But it is hardly reasonable to rely only on the calendar in choosing books.

". Next, you will study eight pages of Hamilton from the Federalist Papers, then fifteen-page notes by Edmund Burke, and twelve more pages from Rousseau's Essay on Inequality. The only thing that will determine the sequence of your reading in this case is the historical connection between any passage and a certain day of the week. But it is hardly reasonable to rely only on the calendar in choosing books.

The passages are too short for a serious effort in learning to read. In addition, their sequence does not allow one to feel the integrity of the proposed selection or understand one passage in the context of another. The Harvard Classics Reading Plan makes great books as incomprehensible as self-selected college courses. Perhaps this plan is designed to celebrate Dr. Eliot, the founding father of free choice education and the Five Foot Shelf literary series. In any case, The Five Foot Shelf is a perfect example of what not to do if we want to save our brains from the St. - Note T&P .

Education, not entertainment

Our reading rules have another limitation. We are only interested in one of the purposes of reading, namely reading for learning, not for entertainment. This goal applies equally to both the reader and the author. The object of our attention is books designed to teach something, aimed at transferring knowledge. In the first chapters, I have already explained the main difference between reading for knowledge and reading for pleasure, emphasizing that it is the former that interests us. We must now take the next step and identify two large classes of books that differ in the goals of the authors and the ability to satisfy the intellectual demands of readers. This is important because our rules only cover one type of book and one purpose of reading.

There are no generally accepted standard names for these classes of books. It would be too tempting to call one of them poetry or fiction, and the other non-fiction or non-fiction. But today the word "poetry" usually means poetry, and not all fiction, which was once called fiction. Similarly, the term "nonfiction" is rarely used in relation to books on history and philosophy, although both of these disciplines involve the transfer of knowledge. If we ignore the terminology, it becomes clear that the difference lies in the intention of the author. The poet or writer practices the fine arts, seeks to please or excite delight through beautiful works, just as does the musician or sculptor. Scientist or any specialist in the field Humanities strives to teach others by speaking the truth. […]

Similarly, the term "nonfiction" is rarely used in relation to books on history and philosophy, although both of these disciplines involve the transfer of knowledge. If we ignore the terminology, it becomes clear that the difference lies in the intention of the author. The poet or writer practices the fine arts, seeks to please or excite delight through beautiful works, just as does the musician or sculptor. Scientist or any specialist in the field Humanities strives to teach others by speaking the truth. […]

The greatest books often combine the two main dimensions of literature. Plato's dialogue "Republic" ❓ In the Russian-language anthology, the name of this dialogue often sounds like "The State, or About Justice." The work is included in the Eighth Tetralogy of Plato's Dialogues. — Approx. T&P must be read both as a play and as an intellectual conversation. Dante's Divine Comedy is not only a brilliant poem, but also a serious philosophical study. Knowledge cannot be conveyed without sensual and creative accompaniment; and feelings and images are invariably permeated with thought.

However, the two arts of reading are different. It would be a mistake to assume that the rules considered here apply equally to poetry and science. […]

Perhaps you will disagree with my point of view and say that I artificially erected a barrier where there is none. You can argue that there is only one way to read for all books, or, conversely, that any book can be read in a variety of ways.

I foresaw these objections even at the moment when I argued that many books have several dimensions, for example, artistic and scientific. I even said that most books, especially great ones, can be read both ways. But this does not mean that the two ways of reading should be confused or confused with each other. We must not forget the original purpose of reading or the main intention of the author in creating the book. I think most authors know whether they are primarily poets or scientists. Of course, all great writers know this.

A good reader should understand what he expects from a book first of all - knowledge or pleasure.

Therefore, by choosing a book with a similar intention of the author, he can more easily achieve his goal. In search of knowledge, it is wiser to read books whose main goal is learning. If you need knowledge in a particular area, it is better to turn to books on the relevant topics. Interested in astronomy, it is hardly worth reading the history of Rome.

This does not mean that the same book cannot be read in different ways and for different purposes. An author can have many intentions, although, in my opinion, one of them always dominates, dictating the general character of the book. A book, as we have already said, can have two dimensions - primary and secondary. For example, Plato's Dialogues is first and foremost a philosophy, and only then a play; The Divine Comedy is first and foremost a poem, and only then a philosophy. The reader, in turn, can view any book from a similar position. If he wishes, he can reverse the author's intentions and read Plato's Dialogues as plays, and see the Divine Comedy primarily as a philosophical treatise. Here it would be appropriate to draw parallels with other areas. A piece of music, conceived as an example of high art, can be used to lull an infant. A chair designed for sitting can be made into a museum piece and admire its beauty.

Here it would be appropriate to draw parallels with other areas. A piece of music, conceived as an example of high art, can be used to lull an infant. A chair designed for sitting can be made into a museum piece and admire its beauty.

Such a duality of goals and a change in the positions of the main and secondary do not affect the main idea. No matter how you read, no matter what goal you put in the first place, you must know what you are doing and follow the rules of this activity. You will not make a mistake if you read a poem as a philosophical work or a scientific study as poetry. The main thing is to be aware of which method you are using and how to use it correctly. Then you will have no doubts about the correctness of your choice and method of action. You will understand that rules matter a lot.

However, in this case, one should beware of two possible errors, which I call purism and obscurantism.

Purism ❓ An exaggerated desire for the purity and simplicity of the literary language, for the exclusion of any extraneous elements from it. In art - the search for simple functional forms that can combine the aesthetic category with the mechanical rational world. - Approx. T&P in my interpretation is the erroneous assumption that the book can only be read in one way. But books are inherently heterogeneous in nature, because the human mind, with which we read or write, is subject to feelings and imagination. It affects emotions, generating a variety of literary means and forms.

In art - the search for simple functional forms that can combine the aesthetic category with the mechanical rational world. - Approx. T&P in my interpretation is the erroneous assumption that the book can only be read in one way. But books are inherently heterogeneous in nature, because the human mind, with which we read or write, is subject to feelings and imagination. It affects emotions, generating a variety of literary means and forms.

Obscurantism ❓ Hostile attitude towards education, science and progress in general; synonymous with "obscurantism". This term is often used to express a mindset in which, instead of being faithful to the truth and being responsible to it, preference is given to that which leads a person away from the truth, obscures it, makes it unclear.— Approx. T&P is also, in my opinion, an erroneous assumption that all books can be read in one way. Here it is easy to go to the extreme and become an adherent of aestheticization, when a person considers all books as fiction, neglecting other types of literature and ways of reading. The second, no less dangerous extreme is intellectualization, when a person considers all books as educational and sees in them only a source of knowledge. Both errors are very aptly described by [the English romantic poet] John Keats in a single line: “In beauty is truth, in truth is beauty.” What is capable of embellishing a solemn ode will be a false premise as a principle of criticism or a key to reading books. […]

The second, no less dangerous extreme is intellectualization, when a person considers all books as educational and sees in them only a source of knowledge. Both errors are very aptly described by [the English romantic poet] John Keats in a single line: “In beauty is truth, in truth is beauty.” What is capable of embellishing a solemn ode will be a false premise as a principle of criticism or a key to reading books. […]

In the "Open Reading" section, we publish excerpts from books in the form in which they are provided by the publishers. Minor abbreviations are indicated by ellipsis in square brackets.

The opinion of the author may not coincide with the opinion of the editors.

How to learn to read 3 times faster in 20 minutes

October 6, 2020Education

Grab a book and check the effect for yourself right now.

Iya Zorina

Author of Lifehacker, athlete, CCM

Share

0Background: Project PX

Back in 1998, Princeton University hosted a Project PX seminar on high speed reading. This article is an excerpt from that seminar and personal experience of speeding up reading.

This article is an excerpt from that seminar and personal experience of speeding up reading.

So, "Project PX" is a three-hour cognitive experiment that allows you to increase your reading speed by 386%. It was conducted on people who spoke five languages, and even dyslexics were trained to read up to 3,000 words of technical text per minute, 10 pages of text. Page in 6 seconds.

For comparison, the average reading speed in the US is between 200 and 300 words per minute. We have in connection with the peculiarities of the language - from 120 to 180. And you can easily increase your performance to 700-900 words per minute.

All you need is to understand how human vision works, what time is wasted in the process of reading and how to stop wasting it. When we analyze the mistakes and practice not making them, you will read several times faster and not mindlessly running your eyes, but perceiving and remembering all the information you read.

Preparation

For our experiment you will need:

- a book of at least 200 pages;

- pen or pencil;

- timer.

The book should lie in front of you without being closed (press the pages if it tends to close without support).

Find a book that does not need to be held so that it does not closeYou will need at least 20 minutes for one session of exercises. Make sure that no one distracts you during this time.

Helpful Hints

Before jumping straight into the exercises, here are a few quick tips to help you speed up your reading.

1. Make as few stops as possible when reading a line of text

When we read, the eyes move through the text not smoothly, but in jumps. Each such jump ends with fixing your attention on a part of the text or stopping your gaze at areas of about a quarter of a page, as if you are taking a picture of this part of the sheet.

Each eye stop on the text lasts ¼ to ½ second.

To feel this, close one eye and lightly press the eyelid with your fingertip, and with the other eye, try to slowly slide over the line of text. Jumps become even more obvious if you slide not along the letters, but simply along a straight horizontal line:

Jumps become even more obvious if you slide not along the letters, but simply along a straight horizontal line:

Well, how do you feel?

2. Try to go back as little as possible through the text

A person who reads at an average pace quite often goes back to reread a missed moment. This can happen consciously or unconsciously. In the latter case, the subconscious itself returns its eyes to the place in the text where concentration was lost.

On average, conscious and unconscious recalls take up to 30% of the time.

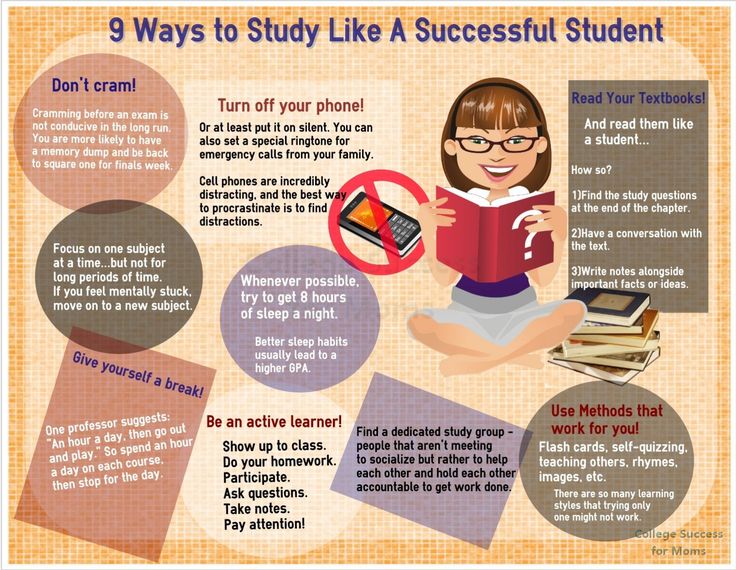

3. Improve concentration to increase word coverage in one stop

People with average reading speed use central focus rather than horizontal peripheral vision. Due to this, they perceive half as many words in one jump of vision.

4. Practice Skills Separately

The exercises are different and you don't have to try to combine them into one. For example, if you are practicing reading speed, don't worry about text comprehension. You will progress through three stages in sequence: learning technique, applying technique to increase speed, and reading comprehension.

You will progress through three stages in sequence: learning technique, applying technique to increase speed, and reading comprehension.

Rule of thumb: Practice your technique at three times your desired reading speed. For example, if your current reading speed is somewhere around 150 words per minute, and you want to read 300, you need to practice reading 900 words per minute.

Exercises

1. Determination of the initial reading speed

Now you have to count the number of words and lines in the book that you have chosen for training. We will calculate the approximate number of words, since calculating the exact value will be too dreary and time consuming.

First, we count how many words fit in five lines of text, divide this number by five and round it up. I counted 40 words in five lines: 40 : 5 = 8 - an average of eight words per line.

Next, we count the number of lines on five pages of the book and divide the resulting number by five. I got 194 lines, I rounded up to 39 lines per page: 195 : 5 = 39.

I got 194 lines, I rounded up to 39 lines per page: 195 : 5 = 39.

And the last thing: we count how many words fit on the page. To do this, we multiply the average number of lines by the average number of words per line: 39× 8 = 312.

Now is the time to find out your reading speed. We set a timer for 1 minute and read the text, calmly and slowly, as you usually do.

How much did you get? I have a little more than a page - 328 words.

2. Landmark and speed

As I wrote above, going back through the text and stopping the gaze take a lot of time. But you can easily cut them down with a focus tracking tool. A pen, pencil or even your finger will serve as such a tool.

Technique (2 minutes)

Practice using a pen or pencil to maintain focus. Move the pencil smoothly under the line you are currently reading and concentrate on where the tip of the pencil is now.

Lead with the tip of the pencil along the lines Set the pace with the tip of the pencil and follow it with your eyes, keeping up with stops and returns through the text. And don't worry about understanding, it's a speed exercise.

And don't worry about understanding, it's a speed exercise.

Try to go through each line in 1 second and increase the speed with each page.

Do not stay on one line for more than 1 second under any circumstances, even if you do not understand what the text is about.

With this technique, I was able to read 936 words in 2 minutes, so 460 words per minute. Interestingly, when you follow with a pen or pencil, it seems that your vision is ahead of the pencil and you read faster. And when you try to remove it, immediately your vision seems to spread out over the page, as if the focus was released and it began to float all over the sheet.

Speed (3 minutes)

Repeat the tracker technique, but allow no more than half a second to read each line (read two lines of text in the time it takes to say "twenty-two").

You probably won't understand anything you read, but that doesn't matter. Now you are training your perceptual reflexes, and these exercises help you adapt to the system. Do not slow down for 3 minutes. Concentrate on the tip of your pen and the technique for increasing speed.

Do not slow down for 3 minutes. Concentrate on the tip of your pen and the technique for increasing speed.

In the 3 minutes of this frenetic race, I read five pages and 14 lines, averaging 586 words per minute. The hardest part of this exercise is not to slow down the speed of the pencil. It's a real block: you've been reading all your life to understand what you're reading, and it's not easy to let go of that.

Thoughts cling to the lines in an effort to return to understand what it is about, and the pencil also begins to slow down. It is also difficult to maintain concentration on such useless reading, the brain gives up, and thoughts fly away to hell, which is also reflected in the speed of the pencil.

3. Expanding the field of perception

When you concentrate your eyes on the center of the monitor, you still see its outer areas. So it is with the text: you concentrate on one word, and you see several words surrounding it.

Now, the more words you learn to see in this way with your peripheral vision, the faster you can read. The expanded area of perception allows you to increase the speed of reading by 300%.

The expanded area of perception allows you to increase the speed of reading by 300%.

Beginners with normal reading speed spend their peripheral vision on fields, that is, they run their eyes through the letters of absolutely all the words of the text, from the first to the last. At the same time, peripheral vision is spent on empty fields, and a person loses from 25 to 50% of the time.

A boosted reader will not "read the fields". He will run his eyes over only a few words from the sentence, and see the rest with peripheral vision. In the illustration below, you see an approximate picture of the concentration of vision of an experienced reader: words in the center are read, and foggy ones are marked by peripheral vision.

Focus on central wordsHere is an example. Read this sentence:

The students once enjoyed reading for four hours straight.

If you start reading with the word "students" and end with "reading", you save time reading as many as five words out of eight! And this reduces the time for reading this sentence by more than half.

Technique (1 minute)

Use a pencil to read as fast as possible: start with the first word of the line and end with the last. That is, no expansion of the area of perception yet - just repeat exercise No. 1, but spend no more than 1 second on each line. Under no circumstances should one line take more than 1 second.

Technique (1 minute)

Continue to set the pace of reading with a pen or pencil, but start reading from the second word of the line and finish reading the line two words before the end.

Speed (3 minutes)

Start reading at the third word of the line and finish three words before the end, while moving your pencil at the speed of one line per half second (two lines in the time it takes to say "twenty-two" ).

If you don't understand anything you read, that's okay. Now you are training your reflexes of perception, and you should not worry about understanding. Concentrate on the exercise with all your might and don't let your mind drift away from an uninteresting activity.