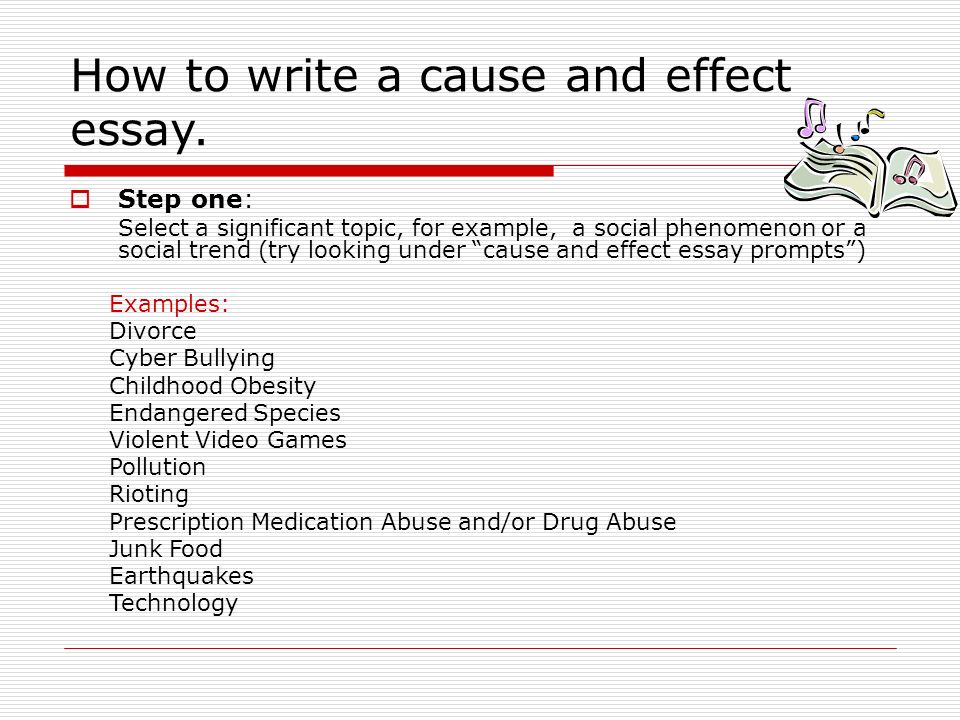

How to write games

Video Game Script Writing - How It’s Done

Most video games are full of words. But where do these words come from? They’re written by writers of course! Like any creative industry, writers are an essential part of video game design. However, video game script writing is distinct from that of films or stage productions for a number of key reasons…

This article gives you a rundown of what it means to write video games scripts, how you can build a career writing for games, and how to write a script that warps a player into the world you’ve created for them.

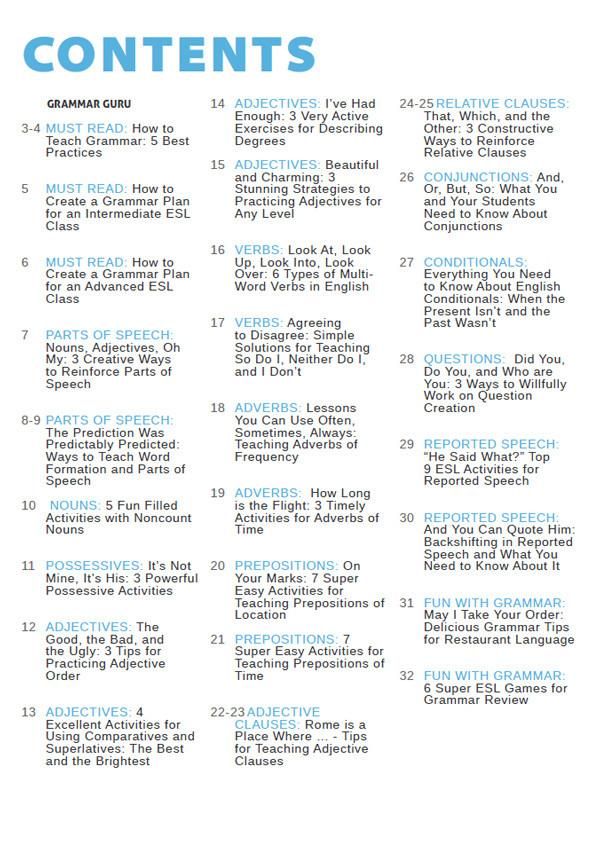

Contents

- What is a video game script?

- How to write a video game script

- What makes the best video game script?

- Examples of video game scripts

- Are voice acting scripts for games different?

- How to become a video game scriptwriter

- What is ‘scripting’ in video games?

What is a video game script?

| Traditional script traits | Game script traits |

| Typically finished before production | Part of the production process |

| Linear/plot-driven | Non-linear/interactive |

| Fewer, traditional forms of text; dialogue, stage direction | Wider variety of texts; flavour text, game lore; item descriptions etc. |

| Principle screenwriter(s)/less collaborative | Multiple writers taking on different roles |

| Written more independently from production team | Written by working closely with designers, voice actors etc. |

Broadly speaking, a script encompasses all of the written text relating to an entertainment production – plays, films, radio broadcasts, video games, and so on.

As shown in the table above, there are quite a few differences between traditional scripts and video game scripts. Video game designer Ian Bogost explains it best:

“…games abandon the dream of becoming narrative media and pursue the one they are already so good at: taking the tidy, ordinary world apart and putting it back together again in surprising, ghastly new ways.”

While traditional narratives do have a place in video gaming, the majority of stories told through video games involve what Bogost calls ‘procedural rhetoric’, a term he coined. This is the idea that a story can be told through the audience interacting with, and learning from, a new world of rules and processes.

This is the idea that a story can be told through the audience interacting with, and learning from, a new world of rules and processes.

Components of a video game script

Plot/narrative: Plumber saves mushroom princess from… a dinosaur? A dragon maybe? While Bogost firmly believes in a future where games present only the environment in which the player builds their own story, most games like to offer a bit more. (FYI Bowser is actually a ‘great demon king’).

Characters: Choose your fighter! Character descriptions and biographies occur in traditional scripts as well. A good character profile is helpful because it keeps all the information you have on a character in one place, creating a kind of handy reference sheet if you need to figure out how they might act in a situation or conversation. The MasterClass staff cover the basics of character profile creation.

Dialogue: “Hey, listen!” Game dialogue can be very different from a film, for example. This is because unless an actor is forgetting their lines or ad libbing, they are supposed to stick to the exact conversation outlined in the script. Even when actors are improvising, a conversation only ever happens once; with the exception of time travel. In video gaming however, decision trees, friendship meters, alignments, replayability, and more can turn one interaction into a multitude of possible routes. For more info, check out these game dialogue tips from the New York Film Academy.

This is because unless an actor is forgetting their lines or ad libbing, they are supposed to stick to the exact conversation outlined in the script. Even when actors are improvising, a conversation only ever happens once; with the exception of time travel. In video gaming however, decision trees, friendship meters, alignments, replayability, and more can turn one interaction into a multitude of possible routes. For more info, check out these game dialogue tips from the New York Film Academy.

Cutscenes: Skippable, if you’re lucky… Cutscenes are probably the closest you’ll get to traditional scripts during video game production. This makes sense, since cutscenes are usually short video sequences designed to provide exposition, as well as breaking up levels or sections within levels of a game. As writer/director Greg Buchanan explains in detail:

“It is therefore crucial… to be able to practice and excel at non-branching narrative.”

Other non-dialogue texts: Perhaps the archives are incomplete. As mentioned in the table above, there’s a wider range of texts in a game than in traditional media. While much of these texts are optional for the reader, they are important for fleshing out the world that’s being created and providing a richer experience for those interested few looking to immerse themselves deeper into your game. Examples include:

As mentioned in the table above, there’s a wider range of texts in a game than in traditional media. While much of these texts are optional for the reader, they are important for fleshing out the world that’s being created and providing a richer experience for those interested few looking to immerse themselves deeper into your game. Examples include:

- Flavour texts

- In-game lore

- Item/environment descriptions (it’s bread)

- Instructions/tutorials/options menus etc.

How to write a video game script

9 (or 10?) steps for writing a game script

- Either

a. Outline your plot

b. Outline your game design - And then do the other one

- Preproduction

- Worldbuilding

- Character design

- Create your story flowchart

- Write your narrative

- Flesh out your script

- Review

Outline your plot ⇌ design: The chicken-script or the game-design-egg?

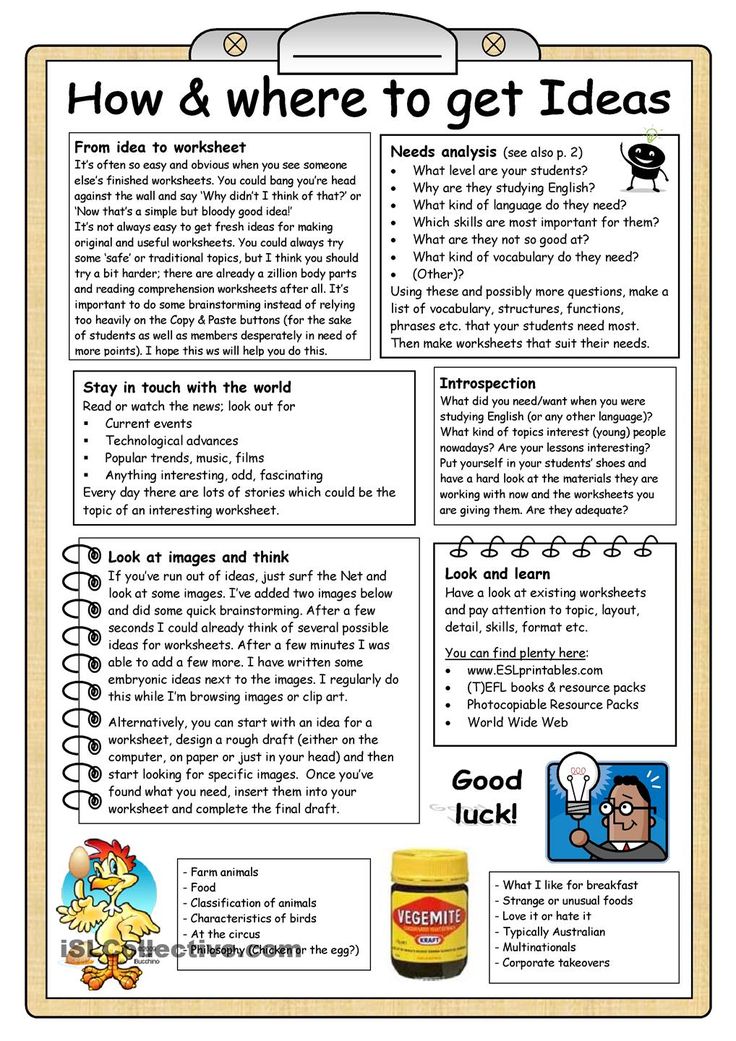

Whether story or design come first in gaming is a tricky question. It can be the case that you have a concept for a game and you then create a story in which to embed your game mechanics. Or for more narrative-based interactive story games you may want to outline a plot first and then decide how your story will literally ‘play out’. Have no idea where to even begin?! – Let writers.com get you going.

It can be the case that you have a concept for a game and you then create a story in which to embed your game mechanics. Or for more narrative-based interactive story games you may want to outline a plot first and then decide how your story will literally ‘play out’. Have no idea where to even begin?! – Let writers.com get you going.

Preproduction: Where to start before starting. The preproduction stage is an important place to cement the idea for your game before spending any money. Part of that process is a prototype script which will give the gist of the story you’re planning to tell, before you spend time and money telling it in full.

Worldbuilding: It began with the forging of the Great Rings… Even a 2D platformer has a backdrop (Mario 3 was a play dontcha know?). When writing a game, you need a place for your game to take place, for the player to explore, and for your characters and events to exist and take place. MasterClass strikes again with their guide to starting worldbuilding.

Character design: Round 2, fight! As mentioned above in our ‘what is a video game script?’ section, character design and profiles help to envision and consolidate aspects of a character to help you decide how they would and should behave during your story. This includes heroes, villains, supporting characters etc.

Story flowchart: If ‘yes’, read on… Now you have the ‘where’ and the ‘who’, you need to figure out the ‘what’ and the ‘when’. This is going to be a meaty (or meat-substitute-y) task because you need to document what is going on at each stage of your story, across all possible story routes, and how the stages of your story flow into and out of one another.

The structure of each stage of a story flowchart will usually be:

- The starting node of a stage

- Nodes describing what is going on (visual environment, music/sound effects, characters, actions)

- Choice/challenge nodes, where decision or dice rolls affect what comes next

- Storylines splitting based on the outcome of nodes at step 3.

- A repeat of steps 2. to 4. for each branching storyline

- One or more ending nodes

At any step after 1., branching storylines can merge again. This happens very often during game scripts because otherwise you’d end up with an unmanageable number of unique storylines to write and create. See this handy guide from Game Developer.

Writing your narrative: Putting pen to paper code. Once the outline, design, world, characters, and structure are all in place, you’re free to enjoy writer’s block! Hopefully not, but it can be tough getting your full narrative written. ACMI have a great guide to the 4 main points of good video game narrative:

- Metaphor

- Plot

- Point of view

- Setting

Fleshing things out: The lawful-evil devil’s in the details. Even when your main narrative is written, there will likely be plenty left to work on. Side quests, alongside the other non-dialogue texts listen in our ‘what is a video game script?’ section above, require lots of additional writing. As long as they’re consistent with your tone and don’t contradict your main narrative then it’s just a matter of getting them done (and a chance to show a little flair and imagination).

As long as they’re consistent with your tone and don’t contradict your main narrative then it’s just a matter of getting them done (and a chance to show a little flair and imagination).

Reviewing: It was the ‘blurst’ of times?! While this is last on our list, since it’s the last thing you’ll be doing, it doesn’t mean you’re meant to leave it all until now. Like most things in life, iterating (doing something over and over, improving it each time) when writing game scripts is best. So, you should be reviewing your script continuously as you go through the design and production processes. Also, reviewing doesn’t just include fixing smelling mistakes or errors between grammar (although these things are important!), it’s also about improving the overall quality of your script by ensuring it has the right tone, is fit for purpose, and all ties together properly.

What makes the best video game script?

Personal preference: Can’t please everyone… Some love a detailed story, some see it as getting in the way of gameplay. Some love epic, large-scale conflict, some love personal journeys. It’s impossible to write a script to please everyone – so pick a story you want to tell and do that well.

Some love epic, large-scale conflict, some love personal journeys. It’s impossible to write a script to please everyone – so pick a story you want to tell and do that well.

The player-character dynamic: Do as I do, not as I wouldn’t do. Coming back to the interactive vs linear debate, when a player is able to make their character behave as they would, it helps immersion. But, giving a player complete control over a game inhibits the designer’s ability to tell a story (The Stanley Parable anyone?). Again there’s no perfect way to balance this dynamic, but it’s an important consideration as you write your script.

Helping the player explore the story: There’s no knowing where you might be swept off to. Regardless of how much control the player has over the story, it should still be presented in a way that allows them to engage with it and encourages them to explore at least ideas and emotions, if not also environments.

5 tips for writing a great video game script

- Consider your audience – think about who you’re making the game for and adjust the complexity and tone accordingly.

- Focus on believability – even in a world of fiction or fantasy, the story needs to be cohesive and plausible.

- Set rules and stick to them – by deciding what does and doesn’t fit into your narrative, you can help maintain the themes and feel of your game.

- Done is better than perfect – don’t let perfectionism stop your writing. You’ll have a chance to improve your work as you review and iterate.

- Be passionate and creative – have fun writing and do what feels right for you. This will shine through your script and your audience will pick up on it.

Examples of video game scripts

- Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead

- What Remains of Edith Finch

- Bioshock

- The Last of Us

- Silent Hill 2

Above are links to fan wikis (and IGN) that contain transcriptions of video games known for exceptional storytelling and impressive scripting. While they aren’t full scripts in the way you’d expect to write one for your own game (mostly just dialogue with description/stage direction), they can give you a sense of what a successful script includes. We’ve excluded games with literary source materials, since they won’t be relevant if you’re looking to write a novel script of your own.

While they aren’t full scripts in the way you’d expect to write one for your own game (mostly just dialogue with description/stage direction), they can give you a sense of what a successful script includes. We’ve excluded games with literary source materials, since they won’t be relevant if you’re looking to write a novel script of your own.

BunnyStudio also have a great article with example excerpts from successful video game scripts, and explanations of why they work so well.

How to become a video game scriptwriter

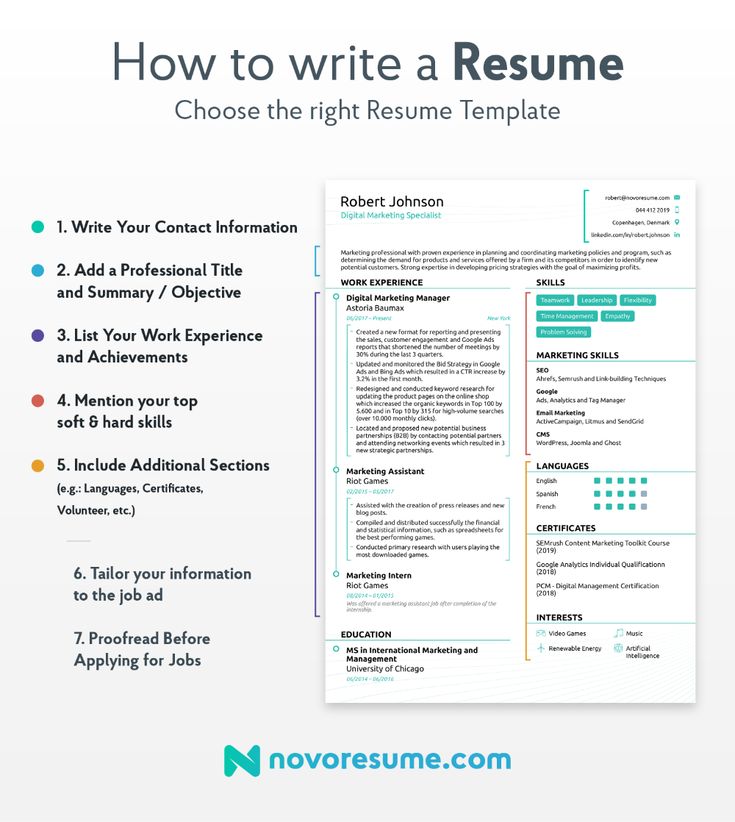

Here’s 6 steps for to building a career in video game writing:

- Get educated – most jobs in game writing require you to have finished school at least. It’s likely a degree will help your prospects too, particularly one in Computer Science or English.

- Immerse yourself in the gaming industry – sort of obvious really but being interested in gaming will help. But also, researching the industry and being interested in making games (not just playing them) will help.

- Read and write really regularly – writing every day is good practice to hone your skills. Things like entering writing competitions, or keeping a diary or blog are great ideas. And it goes without saying that reading, particularly around video game scripts, will be beneficial.

- Learn to code – while you won’t be coding the game yourself, a basic understanding is likely to be beneficial and get you a second glance over your CV from a potential recruiter.

- Get experience and credentials – while we don’t think you should have to work for free, unfortunately volunteering can get you experience and publications to put on your C.V. Also, starting your own project might be the way to go, perhaps with a friend who can code extensively.

- Set yourself up as a freelancer and apply – video game writers often work freelance since it allows for flexible project management and for you to work as needed across multiple projects.

Make sure you know how to set up a portfolio, and how to write good applications and ace job interviews.

Make sure you know how to set up a portfolio, and how to write good applications and ace job interviews.

What is ‘scripting’ in video games?

If you’ve made it down this far and you’re wondering how a masterfully crafted narrative helps people get headshots every time then you’ve probably realised video games script and scripting in video games aren’t particularly related.

Scripting means writing code that performs a function in a video game. More specifically, the term is used to refer to writing a script to help you perform better at a game (often meaning cheating at the game). It’s generally frowned upon and will typically result in a ban if used in online competitive games.

How to Write a Good Video Game Story — E.M. Welsh

Whether you’ve been playing video games since you were a kid or have recently noticed them as an exciting new medium to tell your story in, you may be wondering how to write a good video game story.

After all, video games seem deeply complex and overwhelming—not to mention all the development work behind them. Is writing a video game on your own really possible, let alone a good one?

Is writing a video game on your own really possible, let alone a good one?

Like with any storytelling skill, writing a video game story takes practice. But the barrier to entry is much lower than you may realize. And while you shouldn’t just dive into a 100+ hour video game script on your own, writing a shorter game is completely plausible.

The trick is in the organization of your approach! Using this three-part series on how to write a video game, you’ll have the foundation you need to start writing your first video game script.

In this post, you’ll learn how to write a good video game story—meaning the exact order to approach your writing—and in the following two posts afterward you’ll learn more about world building and character development. Then, you’ll be ready to write your first quest and eventually the whole story!

What makes a good video game story?

There are so many features of a good video game—the combat, the world, the mechanics, the interactivity. But these features aside, what makes a good video game story?

But these features aside, what makes a good video game story?

Just like with any storytelling medium out there, there is no secret formula to what makes a good video game story. One video game can have turn-based combat, last over 100 hours, and have zero choices for the player to make, whereas another game can be 20 minutes long and have nothing but choices.

This doesn’t even account for preferences, which always dominate what we believe makes a good story, no matter the medium. Some people can’t stand a game that is all story—they want exploration and time to pursue random side quests or odd jobs—whereas others would be okay if video games didn’t have combat at all!

Despite all these differences, there remains one element that every video game has and must consider—the player-character dynamic.

No matter your preferences, a good video game keeps this unique dynamic in mind, the dynamic that says both you—the player—and the main character are one, so no matter what, you cannot allow the main character to do something the player does not believe they would do.

In other words, the player is playing a video game—versus watching a movie—because they want to feel they have control, and every good video game story gives the player that sensation, even if there aren’t any choices to be made or no visible story to follow.

What are the elements of a video game narrative?

The two elements of any good video game narrative are:

While we’ve already discussed the player-character dynamic, to dive into it a bit further, this dynamic ensures that the player never has a moment when they think to themselves, “Wait, my character wouldn’t do that.” (Which is often why second-person in prose hardly works.)

A good video game story understands that balance, even if their main character has a distinct personality, like Aloy in Horizon Zero Dawn. Sure, she may have certain traits that are unlike the players, but she never refers to instances that the players aren’t aware of or speaks of things in her past they didn’t already know about. This is so often why many video games rely on the crutch of amnesia—something to avoid, for the most part. It makes that player-character dynamic easy.

This is so often why many video games rely on the crutch of amnesia—something to avoid, for the most part. It makes that player-character dynamic easy.

In addition to the strong player-character dynamic, there is also interactivity. How interactive the game and story can be varies, but every video game story must offer some form of interaction, otherwise it’s a movie, albeit a very long one.

This interactivity comes in many different forms. In Persona 5, it can be something like choosing to water plants versus watching TV, or it can be the exploration of an entire world like it is in Skyrim, where every item can be touched and picked up. Though this element may not be the first thing you think of when writing a story, it is just as important to remember when writing your video game script as the player-character dynamic.

How do you write a video game?

Though writing a video game isn’t as simple as just following a few steps, there is an approach that is the most efficient and leads to fewer problems in the long-run. This means starting big and broad, then getting specific as you know more and more. And of course, always keep that player-character dynamic in mind.

This means starting big and broad, then getting specific as you know more and more. And of course, always keep that player-character dynamic in mind.

Step 1. Outline the major storyline

Whether you have several different possibilities for an ending or one canon story, you’ll want to start out writing your script by outlining the major storyline.

If your story has a lot of different endings or outcomes, you may find this difficult. However, it’s important you have a major outline of the canon story, despite all these possibilities. Writing this outline often means noting all the major events every character—regardless of their decisions—must go through and listing three different ending possibilities.

Of course, if you are writing a linear story without possibility, then the major storyline is a bit easier to write, as you don’t have to allow your story room to have alternate endings and outcomes.

But no matter your story’s path—with possibility or not—providing yourself with a large outline of the major plot points will save you an enormous amount of trouble later on, even if you consider yourself someone who doesn’t outline.

Step 2. Decide what type of game it will be

After you know the general structure of your story and how things will go, you’ll want to decide what type of game it will be.

You might be thinking the game’s mechanics don’t matter to you as a writer, but they absolutely do. Think of it like trying to write a novel without deciding whether it’s in first or third person—it’s just not possible and it’s a not a light decision—it changes the entire framework of your story.

So, before you go any further with your story, decide what type of game it will be:

There are other types, of course, and many hybrids between two—such as an action RPG—but these are the core games you’ll find. The more you play, the easier it will be for you to distinguish and decide which type of game would be best for your story.

Step 3. Develop your world

After you’ve decided what your game will be, you’ll want to begin developing your world. You may feel inclined to create your main character first, and if you have a strong vision for them, that is okay.

But more often than not, the main character is far less important than the world. This is because your players will be viewing the world a lot more than they will be viewing themselves, even if it’s a third-person game.

In a video game, the world is from your character’s perspective, so in many ways, it’s how players experience character development.

For that reason, you’ll want to flesh out your world, its culture, lore, and so forth before you dive into all your character development, in addition to determining just how much “world” your players can explore, something we will discuss in part two of this series.

Step 4. Create your main characters

Once you have your world established—or at least as much as possible—you can then move on to creating your main character and any other prominent characters, such as villains, companions, and so forth.

Creating characters for video games isn’t much different than creating them for other stories until you introduce possibilities to the narrative that can change how characters behave. You also interact with these characters from a first-person mindset, so approaching that relationship can be tricky for new writers, something we’ll cover in the third and final installment of this series.

You also interact with these characters from a first-person mindset, so approaching that relationship can be tricky for new writers, something we’ll cover in the third and final installment of this series.

Step 5. Create a flowchart of your major story

After you have the characters and the world of your story, you’ll want to create a flowchart of your main story. This will show any deviations in the story, should they emerge or small changes if certain things occur. You can also use this flowchart to show where side quests could appear, though it is best to focus on the main story for now/

Step 6. Start writing the major story

Once you have all the major pieces of your story, you can start actually writing the major story. Focus on canon cutscenes or one version of the story at first, then deviate after you have one core version.

You can write the main story either as a summary, or you can actually begin to dive into scene-writing.

How you do it is up to you, but starting with cutscenes that have minimal interactivity is a great basis to ground your story in. If you don’t believe me, consider the fact that most video games have “cutscene only” versions on YouTube where you can watch the story like a movie. Use those cutscene versions as inspiration, and write that bare-bones version of your story before you begin to dive into interactivity, side quests, and other possibilities.

If you don’t believe me, consider the fact that most video games have “cutscene only” versions on YouTube where you can watch the story like a movie. Use those cutscene versions as inspiration, and write that bare-bones version of your story before you begin to dive into interactivity, side quests, and other possibilities.

Step 7. Add in side quests, NPCs, and other small details

Once you’ve written the major story, you can add in all the fun stuff.

For some, that may mean adding in side quests or filling the world with non-playable characters. For others, it may mean it’s time to start writing out the alternate versions of your story and planning how different players achieve different endings.

If you’re not sure where to start, here are some common things you can add to fill out your story:

Non-playable characters - People who your player can interact with. Often they may just have fun “barks” where they express their opinion, reveal information about the world, or even give you hints.

Other NPC’s offer side quests and rewards with a more expansive storyline.

Other NPC’s offer side quests and rewards with a more expansive storyline.Side quests - If your story is big enough, you may want sidequests sprinkled throughout your world. These side quests can be related to the world, culture, lore, or explore backstories of some of your other characters. They don’t have to affect the main plot at all, or they can be detrimental to the success of the mission.

Items - The objects your characters use go beyond weapons and armor. There can be notes, letters, and other things that help with quests to include as well. A jewel can have a story behind it or an abandoned home can be filled with things left behind. The sky's the limit when it comes to items—so get creative! (And use a spreadsheet to keep track of all your ideas.)

There are more tiny details in a game, but these are the most common ones you’ll see and often where you’ll have a lot of fun and be able to really differentiate your story!

What do you need to write video games?

Contrary to what you may think, you don’t need much to write a video game. Depending on the scope of your game, you may only need yourself—or you may need a team of writers. But beyond that, until you get to development, you only need two things:

Depending on the scope of your game, you may only need yourself—or you may need a team of writers. But beyond that, until you get to development, you only need two things:

Experience playing video games

Just as the saying goes that if you want to be a writer, you’ve got to read a lot, so it goes that if you want to be a video game writer, you’ve got to play a lot of games.

While I think this is true for all types of writing—if you want to write movies, you absolutely must watch them—it’s especially true for video games because you must not only consider the story but the gameplay element.

True, writers typically don’t code the games and really determine the gameplay mechanics. But when video game writers don’t consider the mechanics of the game as part of the story, there can be cause for serious disconnect amongst players.

For instance, in games like Horizon Zero Dawn and The Witcher, the heroes are hunters often tasked with taking down beasts and other troublesome foes. This changes how the world interacts with them and the quests they’re given as much as it shapes how combat feels.

This changes how the world interacts with them and the quests they’re given as much as it shapes how combat feels.

Additionally, it’s incredibly difficult to imagine and write movement in a video game—and all the possibility—if you’ve hardly ever played one. Though you may not need to figure out different types of ammo or weapon upgrades, you need to be able to envision how your story moves in a three-dimensional world filled with possibility, not just a linear narrative.

For more information on this and a list of different games to play, check out why video games help all types of storytelling.

Video game writing script software

Though there is no “official” way to write a video game script, there are a few different software you can turn to for help.

Word Processor - Yes. As simple as it may seem, a word processor like Google Docs or Pages can be used to write a video game script. Don’t believe me? Check out the template I used to write my first quest here.

FinalDraft - Though this software is used for writing screenplays, it can also be used to write video game scripts as well!

Twine - While I’ve never used Twine, it is said to be a great way to write a non-linear story. Plus, you can publish your work anywhere after it’s done to find fellow developers to help you work on it!

Inklewriter - Though technically Inklewriter is a permanent beta, it offers a nice alternative to Twine should you wish to write a more interactive story instead of the branching style that Twine offers.

Keep in mind that no matter what software you choose, it is much better to have a finished game than to have an unfinished game. Even a quest completed becomes something you can show in your portfolio, so choose whatever software and style best suits you, and then write the game that comes most easily to you.

Often this is going to be the more simple idea, so try not to write a triple-A RPG for your first go. A whole team is behind those types of games, so shoot for something like Undertale or A Stanley Parable for your first try.

A whole team is behind those types of games, so shoot for something like Undertale or A Stanley Parable for your first try.

How to start writing games / Habr

Original: Starting out on Game Programming

The path to the game development industry is not close. This article is intended to help you understand where to start this journey.

You have just completed your first C++ course and want to start making games. Someone pointed you to this site and you may have experimented a bit with the guide. You've gone through a few concise examples but haven't found a guide on how to make an entire game. And there is a reason for that.

Tutorials are good for learning something step by step, like how to move a point image around the screen. In order to put the game together, you need problem-solving skills that come with experience. It's not something you can learn from manuals. The best way to learn how to make games is to start making them.

Project selection

So where do you start? It is easier to answer where not to start, namely with large projects, such as a full-fledged 3D FPS, MMO, or even a long platformer of the 16-bit era. The most common mistake new developers make is to start with a big project based on a Cool Idea, or take a project that seems simple and end up with a half-finished bunch of spaghetti code. Start with small projects first.

In early projects, your main focus is learning, not implementing Cool Ideas. By keeping the project small, you can focus on learning new techniques instead of spending a lot of time on code management and refactoring. While your Big Idea may be awesome, the reality of the development industry is that the bigger the project, the more likely it is to make an architectural mistake. And the larger the project, the more expensive this mistake is. Remember the story of Daedalus and his son Icarus? Daedalus created wings from wax and feathers for his son. He warned Icarus not to fly them too close to the sun. But Icarus ignored the warning and the wings melted, and that's when gravity caught up with him.

He warned Icarus not to fly them too close to the sun. But Icarus ignored the warning and the wings melted, and that's when gravity caught up with him.

So remember: don't fly too close to the sun with your new programming wings.

With all that said, here are a couple of tips to get you started.

Graphics and event handling

If you've never programmed anything graphics or GUI related, you should start with something small to get your feet wet. My first project was tic-tac-toe, so even I had humble beginnings. A couple of ideas for the first project:

- One Armed Bandit Simulator

- Black Jack

- Tic-tac-toe

- Four in a row

The goal of your first project is to move from console development to development of event-driven graphical applications. It will also teach you the fundamentals of game logic and architecture. I recommend something turn-based because motion games are a whole other beast.

I recommend something turn-based because motion games are a whole other beast.

Try to keep the project simple so that you can complete it and not lose interest halfway through and never finish the game. It's important to finish a game because you don't learn how to develop if you have a few unfinished games on your hard drive.

There is one point that I want to point out to those who will be doing tic-tac-toe or four in a row. Don't worry too much about artificial intelligence right now. Making the game only for two players, or playing with a computer that makes random moves is enough to get you started.

If you've dealt with graphics and event handling before and feel comfortable in that area, you can go straight to the next step.

Synchronization, motion, collision, animation

Now that you've played around with the graphics, it's time to do something in real time. Here are a couple of suggestions:

- Duck Hunt

- Pong

- Space Invaders

- Galaga

- Tetris

Here you will learn about motion, timing, animation, collision detection, game loop, scoring, win/loss calculations and other important basic concepts used in every game.

Duck Hunt and Pong are good projects for those who already have experience in graphics and events programming. They have simple collision detection and all the essential basics of real-time gaming.

Space Invaders and Galaga are good choices for a second/third project. They have levels, so you will need to learn how to move from level to level using a state machine. You can read about state machines here. Shoot 'em up games also require you to create simple behavior patterns for your enemies, which is a step towards artificial intelligence.

Tetris is good for the second/third project. It has very little logic needed to create a puzzle game. It's a decently sized game, so you'll have to learn how to split your program into multiple source files, which you can read more about here. Don't underestimate Tetris. I underestimated and just look at this terrible mess in the Lazy Blocks code.

Reengineering

A typical rookie mistake is trying to make the Greatest Game of All Time, ending up in over-engineering. That is, when he tries to write the best game / engine and it all ends up using only a small part of what was written.

That is, when he tries to write the best game / engine and it all ends up using only a small part of what was written.

When I was a beginner I reengineered the AI for tic-tac-toe. I wanted to make a game with invincible AI. I managed to achieve this by programming the computer to know all possible traps. Sounds cool doesn't it? It took almost 40,000 lines of mostly copied code and a month of my free time.

Later, I learned data structures and learned about the Minimax algorithm, which, with a smaller code size, not only did the right thing, but also did it better.

So learn from my mistakes and don't be too ambitious. Focus on learning how to make games instead of just making them.

Planning, collision analysis, physics, levels, artificial intelligence

Now that you have two or three small games under your belt, it's time to make your first big project.

So far, you've probably been programming as you go. It will end at this point. In the real world, most development processes are completed before the first line of code is written. Nothing can be worse than realizing that in order to add what you want to your game, you have to throw out all the code you wrote, because you didn’t plan everything in advance. Now that you have some experience in making games, you know what the development process is all about. Now you can plan games before you start making them.

It will end at this point. In the real world, most development processes are completed before the first line of code is written. Nothing can be worse than realizing that in order to add what you want to your game, you have to throw out all the code you wrote, because you didn’t plan everything in advance. Now that you have some experience in making games, you know what the development process is all about. Now you can plan games before you start making them.

Now about your next game. Break Out and Puzzle Bobble are good for a third project because they include advanced collision detection and physics. Physics is important because it gives the game a realistic feel. Even Super Mario Brothers has a sense of gravity and momentum. Billiards is an excellent project for those who want to strain their brains with physics.

In games like billiards, you not only need to detect collisions, but also process them in a specific order. Collision handling is very different from collision detection. While creating a pool table or a 2D platformer may seem like a simple matter, analyzing collisions in the right order is a tricky process and shouldn't be underestimated.

While creating a pool table or a 2D platformer may seem like a simple matter, analyzing collisions in the right order is a tricky process and shouldn't be underestimated.

Break out and Puzzle Bobble also include level design and require their resources to be loaded and freed. It would be a good experience to create a level editor for the game. Editors allow you to easily create levels without having to solder them into the application. I have an article about creating a level editor.

You might also want to practice writing artificial intelligence (AI). One option is to go back to tic-tac-toe or four in a row and write an invincible AI. By now you should already know data structures and will be able to use your knowledge of trees to use the Minimax algorithm. With this algorithm, you can calculate all possible outcomes of tic-tac-toe and create an invincible AI. It's fun to upset your friends with it. You may also want to make different levels of difficulty. A game isn't fun if it can't be won.

Pac Man is a great way to practice writing AI. You will need to know tree/graph structures and search algorithms like A* in order for the ghosts to get through the maze. You will also need to make the ghosts work in a team. All this will come in handy when you make games with complex AI, such as real-time strategy games. You can read about the basics of AI here.

Platformers, Action/Adventure, RPG, RTS, Engines

Now that you've had experience creating a well-planned game, you're ready to create an Action/Adventure/Platformer. It will be the culmination of graphics, motion, animation, collision analysis/detection, physics, AI, software architecture, and everything else you've learned up to this point. Those who are more ambitious can be offered to make a real-time strategy (RTS) or role-playing game (RPG). Be careful because RPG and RTS are really huge projects.

RPGs have a complex architecture and require a lot of planning. You will need to plan every weapon, armor, trinket, attack, item, spell, summon, enemy, map, boss, dungeon, etc. down to the smallest detail. It all has to work smoothly, and, to put it mildly, this is not an easy task. So if your design project looks like a script or a comic, you need to do 9 more0141 many works.

You will need to plan every weapon, armor, trinket, attack, item, spell, summon, enemy, map, boss, dungeon, etc. down to the smallest detail. It all has to work smoothly, and, to put it mildly, this is not an easy task. So if your design project looks like a script or a comic, you need to do 9 more0141 many works.

RTS are also architecturally complex and require a lot of AI. You will need to do pathfinding for units, receiving commands, different behavior depending on the received commands. If you've never done AI before, it's best to start with a Pac Man clone to start with.

This is probably the first time you'll have to build an engine for your game. What should be avoided is creating a generic engine. When creating an engine, do not try to make it suitable for any game. If your game requires x, y, and z, make an engine that can x, y, and z. Engines are created based on what is needed for a particular game, and not on the basis of what any game could potentially need.

Another common mistake among beginners is trying to create an engine as a first project. And usually it is a universal engine. You don't need a fancy graphics engine to make Pong or Space Invaders. When programming, it's easy to dig into the details. Focus on the big picture and complete your games.

Network

Everyone seems to want to make the next big MMO. Making online games is not something you can quickly grasp. I figured this out when I tried to do online poker right after finishing tic-tac-toe.

Adding a network makes the game much more difficult. When one player does something, you must send information about it to everyone else. It's like your right hand doesn't know what your left hand is doing. You will also have to choose between server load and what it can control. The more the backend does, the less chance the client has to cheat, but it also means more load on the server. For action and other high paced games, you'll have to worry about network latency and packet loss.

You should complete at least one well-planned game before attempting a multiplayer game. As your first networking project, try doing something that is not speed critical. For example, a simple chat server/client would be good practice. You can also return to tic-tac-toe / four in a row and add the ability to play online to them. Alternatively, try making an online card or board game.

After your first network project is ready, try doing something in real time. In your first networking application, you probably used TCP to make sure that the data you received arrived in the order you sent it. For games with a lot of action, the delays introduced by TCP will probably be too high, so you will have to use UDP. UDP does not guarantee the order of delivery, nor does it guarantee delivery at all. Because UDP doesn't do extra integrity checks, it's faster. You have to sacrifice the ease of use of TCP in exchange for the speed of UDP and the need to check data integrity yourself when creating a game.

3D games

Before making 3D games, you should make at least one well planned game and have a good understanding of 3D vector math, linear and Newtonian physics. Here you have to deal with vertices, textures, lighting, shadows, defining interaction with objects in three-dimensional space, loading models and other complex sounding things.

The good news is that if you've already made 4 or 5 games, you already know the basics needed to create a game. You are already familiar with the development process and know your capabilities as a programmer. Whether it's a 3D shooter or a 2D shooter, it's still a shooter. 2D RPG or 3D RPG is still RPG.

Don't take this as an excuse to skip 2D and go straight to 3D. Before you can learn to run, you must learn to walk.

Quick way

Are you saying that you learn faster if you jump right in and just write your 3D MMOFPSRTSRPG and learn what you need as needed? Well, here are a couple of tips to help you:

- Go to the local market

- Buy a whole fish.

I recommend taking salmon or cod, although catfish is also suitable. Trout, by the way, is also quite effective

I recommend taking salmon or cod, although catfish is also suitable. Trout, by the way, is also quite effective - Go home and turn on the computer

- Launch your favorite IDE

- Now take the fish you bought and hit yourself in the head

- Repeat step 5 until thoughts of a quick way leave you

You don't learn algebra by solving computational problems. You learn the basics and build on them. It's the same with programming. If you're looking for a quick fix, I'm here to tell you there isn't one. Don't rush yourself. Once again: learn the basics and build on them. Otherwise, you will fail.

Journey begins

Now, so that you have a general understanding of what to do after all, it's time to start doing game development. I do not expect you to follow this guide word for word. Everyone learns differently and at different speeds. If there's one thing you should take away from this article, it's three things:

- Pick your pace

- Finish games to the end

- Focus on learning, not just creating

Good luck on your game development journey!

How to start making a game? Step-by-step instructions - Gamedev on DTF

This article is for beginners in game development. For those who want to make a game but don't know where to start.

For those who want to make a game but don't know where to start.

117 866 views

I will try, step by step, to explain the whole process from desire to release. Let's go!

Who am I?

My name is Alexander Dudarev

Alexander Dudarev E-mail: [email protected]

I am a game designer with 10 years of experience. Worked in many companies, for example in Playgendary. He did different things: both casual games for mobile phones, and a tank shooter for PC.

Now I'm an indie developer. I live by selling my games. Released 4 games for PC and Consoles. Now I am developing the game They Are Here: Alien Abduction Horror - a horror from the 1st person, about the abduction by aliens.

They Are Here: Alien Abduction Horror

Step 1: Be Enthusiastic

Enthusiasm is the fuel you burn in development. It will allow you to make a game after work, when you are tired, when you want to relax.

How to replenish the supply of enthusiasm? Watch documentaries, read developer success stories. It's motivating!

For example, here is a great documentary about indie games Indie Game: The Movie

Look around: other games, films, movies, new technologies. The desire to learn something new or do something similar is what you need.

Step 2. Gather a team or do it yourself!

One is easier. It's easier to come up with an idea and make decisions. No need to argue and describe tasks. Making a game alone is possible. For example, I made 4 games alone.

It's better with a team. Better quality. Your decisions are criticized and the result is improved. You can distribute responsibilities and make the game faster. The last game I do is in a team with my wife. She is responsible for the story, criticizes my decisions, helps with art, looks for streamers.

In short - there is a team, cool! There is no team - do everything yourself, it's not difficult.

Typical indie developer

Step 3. Formulate the development goal

It is very important to understand - why do you need all this?

For example:

1. Employment in a game development company.

Product portfolio. The priority is the quality of performance.

Questions: What position would you like to apply for? Which company(s)? What kind of games does the company(s) do? What needs to be learned?

2. Learn how to make games, master a skill.

Prototype product. Priority is new knowledge.

Questions: What skill to master? How to do a specific thing?

3. Tell about something important.

Product Manifesto. The priority is to convey the idea to the masses.

Questions: Will my idea be understood? How to make the product more popular?

4. Make the game you dreamed about.

The product is a dream. The priority is to realize your vision.

Questions: What do I want to see? What can be neglected? How to finish a project?

5. Build your business.

Product - active. The priority is to earn income.

Questions: Which games sell best? How long will development take? How to reduce this time?

There can be more than one target. Goals can change from game to game.

In short - you have to answer the question - why am I making this game?

Really, why?

Step 4. Remember what you can do or love

For example, my wife and I are fans of horror films about aliens. Type "Signs", "Dark Skies", "X-Files". Therefore, it is easier for us to work on ideas and script for They Are Here

Or maybe you draw anime girls in your spare time. And your friend is studying AI programming. So it will be easier for you to make a game about girls who will chat with the player as if they were alive.

Tian approves of starting from skills and hobbies

In short - your skills and hobbies are your advantages. Consider them when choosing a platform, engine, game genre. For now, just think about it.

Step 5. Choose a platform

If it's simple, then there are 2 ways: Mobile phones or PC + Consoles .

Based on the goals and skills of , you will need to choose one thing. These are different platforms, with different games, audience and monetization.

Path 1. Mobiki

Audience:

- Mass audience. Children, pensioners, bored saleswomen. These are not gamers. Everything should be very clear and simple.

- Play for 1 - 5 minutes. On breaks, in line, at work. To kill time.

- Simple bright graphics are appreciated.

- Focus on simple yet addictive core gameplay.

Pros:

- Some genres (puzzles, arcades) are the easiest to develop. You can make a small prototype (1-5 levels) and show it to the employer, for example.

- Pretty or complex graphics are not required. The main thing is to be clear.

- Simple gameplay and game design.

- It will be a plus if he is used to mobile devices and games.

Cons:

- Very. High. competition. There are millions of games and almost all of them are free. Players come only from ads. No ads - no players. No money.

- Monetization. You need to embed ads or in-game purchases into the game. Know where and how. Test to make it all work.

- Analytics. You need to understand what LTV is. Why should it be > than CPI. Embed analytics in the game.

- Be prepared to make 20 prototypes or improve the product until LTV > CPI.

- Earn money for a small team, you can only with a publisher. I personally don't know any other way.

In short - mobile phones, this is a huge super market. On the shelf is something that pays for advertising. It's advertising budget competition. If you want to make money on mobile phones, then I advise you to make hyper-casual games and work with a publisher.

If you don't care about income, it's a cool, lightweight platform.

If you dare, learn more about:

- Hyper-casual games (everything related to game design and production).

- How to find a publisher for hyper-casual games.

- Casual graphics.

- Low-poly graphics.

- Casual players (casual difficulty and tutorials).

- Mobile game analytics (CPI, LTV, Retention).

- Monetization of mobile games.

- Optimization of mobile games.

- Google Play and App Store.

Registering a developer account. Rules and recommendations. SEO.

Registering a developer account. Rules and recommendations. SEO. - Advertising mediators and networks (Iron Source, AdMob, etc.).

- Market analytics services for mobile games (Sensor Tower, App Annie).

Path 2. PC + Consoles

Audience:

- Hardcore gamers.

- Play for several hours. At home. To dive into the game.

- Realistic or stylish graphics are valued.

- Emphasis on an interesting story or deep gameplay.

Pros:

- Less competition than on mobile phones. Especially on consoles.

- Easier to get players and reviews.

- You can make good money by porting the game to the console, with the help of a publisher.

- Don't bother with analytics and monetization.

- From childhood, a clear platform (PC / Console) and audience (Gamers).

- The audience loves original, creative, interesting games.

- It will be a plus if you yourself play on a computer or console.

Minuses:

- Simple games (puzzles, arcades) are bad. Gamers want to get experience, get used to the role. Stick for a long time. The game should not look like something for a couple of minutes.

- Games are longer in production. But you can be tricky - make small games that look like big ones, and also use ready-made assets.

- We need to work on an interesting idea. Find distinctive features (USP) that will make the project stand out.

- You need to think of an interesting story or gameplay.

- More complex game design.

- High demands on the quality of graphics.

In short - PCs and especially Consoles is a luxury boutique. On the shelf is what is in demand. This is quality competition. If you want to make money, then make an interesting game, and be sure to port it to the console (through a publisher). Think about how to save on production!

If you dare, learn more about:

- Game design for computer games.

- Narrative, storytelling.

- How to pitch games.

- Game features / USP.

- What is a vertical slice.

- Steam. Registering a developer account. Page layout. Tags. Rules and recommendations.

- Marketing and promotion of indie games on Steam (I recommend http://howtomarketagame.com/) How to make a cool poster, trailer, screenshots, GIFs.

- Porting games to consoles.

- Console game publishers.

- Indie game contests and festivals.

- Work with influencers (youtubers, streamers).

- Realistic graphics.

- Stylized graphics.

- Tag and genre analytics services (SteamDB, Steamspy, SteamCharts, Game Data Crunch).

- Key distribution services (Keymailer, Woovit)

Step 6. Learn about game design and game production

Get interested in how games are made (great podcast in your headphones)

I recommend to google about:

- Game mechanics, genres and settings.

- Game design. There is a book by Jesse Schell, it's good, but big. You can google about a specific genre.

- Core gameplay and Meta gameplay.

- Level design.

It's better to google about a particular genre.

It's better to google about a particular genre.

- User interface (UI) in games.

- Assets and marketplaces.

In short - first learn superficially about all incomprehensible terms. Explore only what you need to develop your specific game in depth.

Step 7. Choose an engine and look at the tutorials

The engine is the program that builds the game. This is a big food processor that has everything. Logic is programmed there, levels are assembled, lighting is set, animation is set up, materials are created, sounds are inserted, etc.

Many articles have been written about the choice of engine - google it.

If you are alone and don't know programming languages, I recommend Unreal Engine 4.

- Blueprints are there - this is visual programming. It's easier than writing code.

- Nice render out of the box.

- There is a large marketplace with gov assets

- This is a popular commercial engine that is used to make a lot of games.

- You can make a game for all platforms. You can embed advertising, inaps, analytics.

- Lots of levels. I recommend Unreal Engine Rus

- Cool interface.

- A bunch of built-in functions.

- Free up to a lama bucks income.

Unreal Engine 4 Blueprints

Before starting to work on the game, make a couple of very simple table fakes.

Make a snake, ping-pong, etc. Don't care about quality, don't care about game design. The main thing is to practice "on cats", to feel the functions of the engine.

The whole team will work in the engine - so everyone should study it, at least superficially. You must understand each other, and also help the programmer build the game.

You must understand each other, and also help the programmer build the game.

In short - read about the choice of engine. Take the time to study it.

Step 8. Choose a Genre

Genre is your niche. Genre is very important. There are genres that no one plays. And for some you need to study a lot of additional material.

It is better to choose a genre which:

- Popular on the platform. Games of this genre are often bought or downloaded. Use sites for genre analytics.

- Not too difficult to manufacture. MMORPG is not your choice.

- Like you or the team. You understand it or played a lot as a child.

Sales of games in different genres

Once you have decided on a genre, google everything about the production of games in this genre. Game design, graphics, levels, sounds. What to focus on?

Play the best games in this genre. Watch videos about this genre.

Watch videos about this genre.

In short - choose a genre and learn everything you can about it!

Step 9 Come up with an idea, concept, USP

An idea is the core of your game. The seed from which the project will grow.

What is a good idea?

- Clear. Should be clear to everyone. For example, your mom.

- Interesting. I already want to play it! People love risk and new experiences that they want but can't experience in real life. For example, GTA is a tough guy simulation that everyone wants to be but can't.

- Popular. This is not an arthouse, not something strange or specific. The idea appeals to understandable images from life or mass culture.

- Eye-catching. This was not the case before. Or was, but for a long time. Or in another genre. Or in a different style. Or badly done.

What will help you choose an idea?

- Catalog of games on your platform.

See what's popular. Think about how to change it, put it from a different angle. Hmm…a top railroad building game. What if we play as a driver?

See what's popular. Think about how to change it, put it from a different angle. Hmm…a top railroad building game. What if we play as a driver? - Service sites with tag and genre analytics on the platform. You can track the popularity of the genre, the number of games in it. You can cross individual tags with each other.

- Mass culture. Movies, books, comics, short films, gifs, pictures from the Internet.

You will most likely have many ideas. Write them down. Let me lie down. And then choose the one that haunts you and seems the best.

When I gave birth to the idea

Pro pitch

The idea may seem ambitious. But it has to fit in the Pitch to be understood by the players, the press, and your mom.

A pitch is a short sentence describing an idea. For example, They Are Here: Alien Abduction Horror is a horror movie about alien abduction. Read more about "How to pitch games".

Read more about "How to pitch games".

Based on Pitch, we describe the concept of the game. A more detailed description of the game on one page. Who are we playing for? What is the purpose? What can be done? What emotions do we evoke?

Pro USP

Think over the key features - USP, which will sell your project. They flow from your idea.

For example, Punk's idea is a mockery of mass culture and fashion.

Key features (USP) of Punk: defiant behavior, aggressive music and strange hairstyles.

Check out my USP, man!

Show your USP everywhere - in the trailer, screenshots, poster, game description. Talk about them communicating with the press and publishers. Poke them in the face!

For example, They Are Here has aliens, cornfields like in the movie Signs, and UFOs.

In short - read about the idea, concept, pitch, USP of the game. Formulate a clear vision for your project and communicate this vision to everyone. Without it, everything will fall apart and float.

Without it, everything will fall apart and float.

Step 10. List assets and tasks

Assets are the building blocks that make up games.

Make a list of things to do. At least in large strokes. Make a level, find music, insert a character. And you also need 20 types of swords.

Estimate the time and then multiply it by 2. Even if you think it's stupid. Multiply it by 2!

If you see that the project is large, cut off everything unnecessary. Unnecessary - everything that does not show the idea. Or rarely appears on the screen.

For example, if the idea of the game is ultra-violence, then you can not make 20 types of swords, but rather work out the physics of dismembering the body.

Estimate that for mobile hyper-casual games you need to make at least 30 minutes of gameplay. And for PC and Consoles, it is better to make the game for 2 hours. If you can do more, great!

Highly recommended!

Buy and use ready-made assets. This is the best way to reduce production time and not lose quality. It's not embarrassing, it's normal. It's actually fire!

This is the best way to reduce production time and not lose quality. It's not embarrassing, it's normal. It's actually fire!

Step 11. Organize the process

Write down everything that needs to be done. Every little thing. Otherwise, you will forget.

Set tasks. For myself and the team. I recommend Trello (easier) or Asana (more functional).

Gather project information in one place. You can use Miro boards or Notion wikis.

If you're alone or have a small team, don't worry about big and beautiful documentation. It is better to show an example, draw a diagram, explain on your fingers WHAT SHOULD be done.

Reference is the best task description for an artist! For example, I told my wife - I want a cover like Slender, but with an alien. That's enough!

Collect and store the necessary information. Links to great articles. Contacts of possible partners. Screenshots of bugs. And so on.

Step 12. Make a demo

Make a demo

Demo / Vertical slice / MVP are very similar concepts. This is a small piece of the final quality game.

Small but high quality demo

Demo version solves many problems:

- Helps you record videos, screenshots, gifs

- Shows the payback of a mobile game

- Will help you get a job

- Speed up wishlist recruitment on Steam

- Receive feedback from players and streamers

- Can participate in festivals and competitions

- Only with it you can find a publisher.

In short - make a demo version of the game. This is your calling card. Show it to everyone. Say - I will do the same, only more.

Step 13. Fuck! Break through to release!

I won't go into details about the release.