How to writing for kids

Writing Basics | Reading Rockets

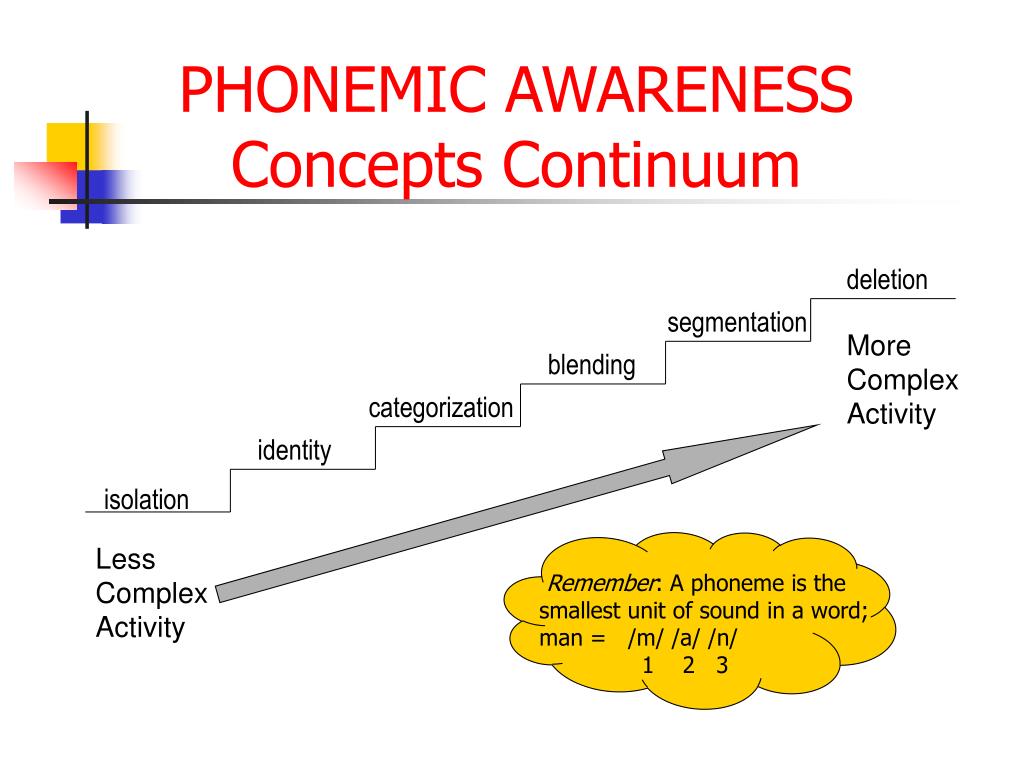

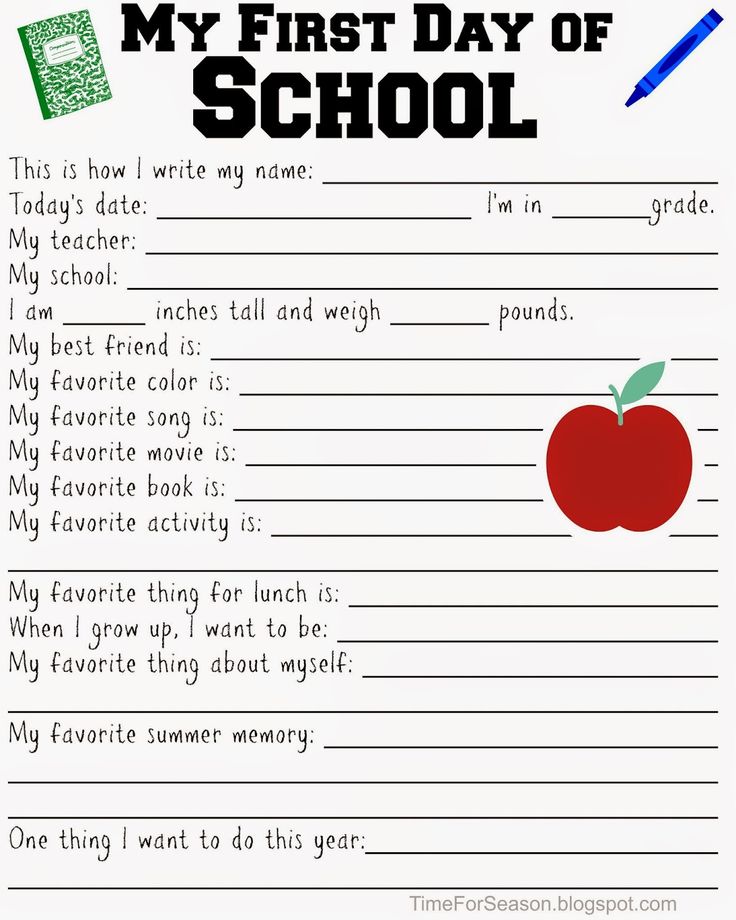

Part of early print awareness is the realization that writing can be created with everyday tools such as pens, pencils, crayons, and markers. Children begin to imitate the writing that they see around them. What often starts as scribbling ends up being important clues to a young child’s understanding that print carries meaning.

How writing develops

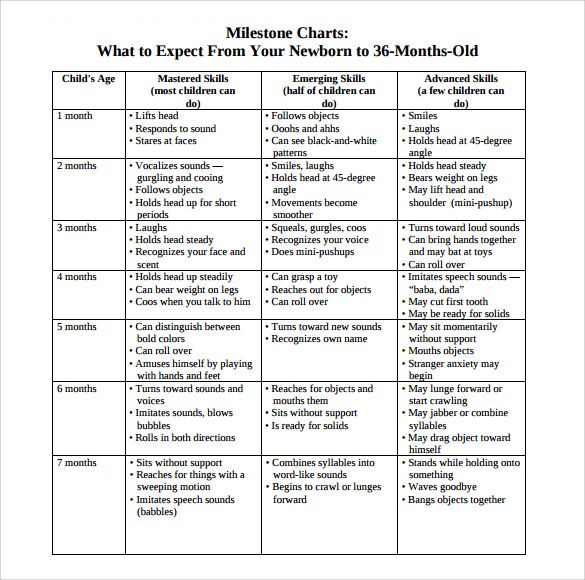

Young children move through a series of stages as they are learning to write. The stages reflect a child's growing knowledge of the conventions of literacy, including letters, sounds and spacing of words within sentences. Almost every interaction in a child's world is preparing them to become a reader and writer.

It's important to remember that every child is different and there are variations in the way kids move through writing stages — it may not happen in the same way or at the same time and the lines between the stages can be blurry.

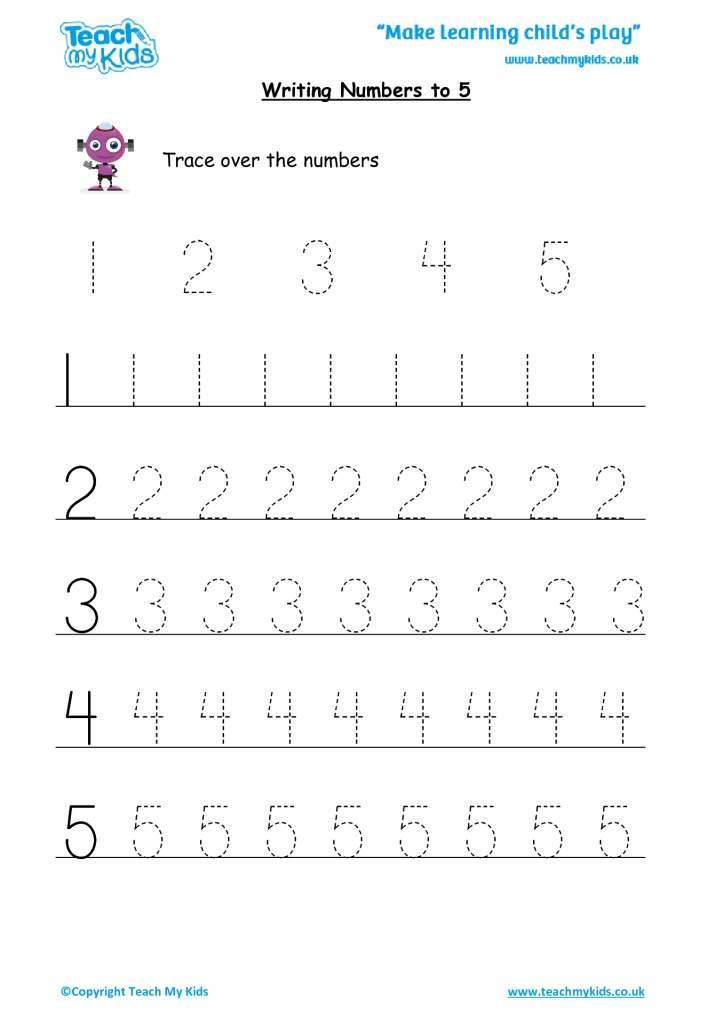

Scribbling/drawing

Most children begin their writing career by scribbling and drawing. Grasping the crayon or pencil with a full fist, a young scribbling child is exploring with space and form. He is creating a permanent record of his ideas and thoughts. These first scribbles can be proud accomplishments! Thick markers, crayons, and unlined paper are good writer's tools for this stage.

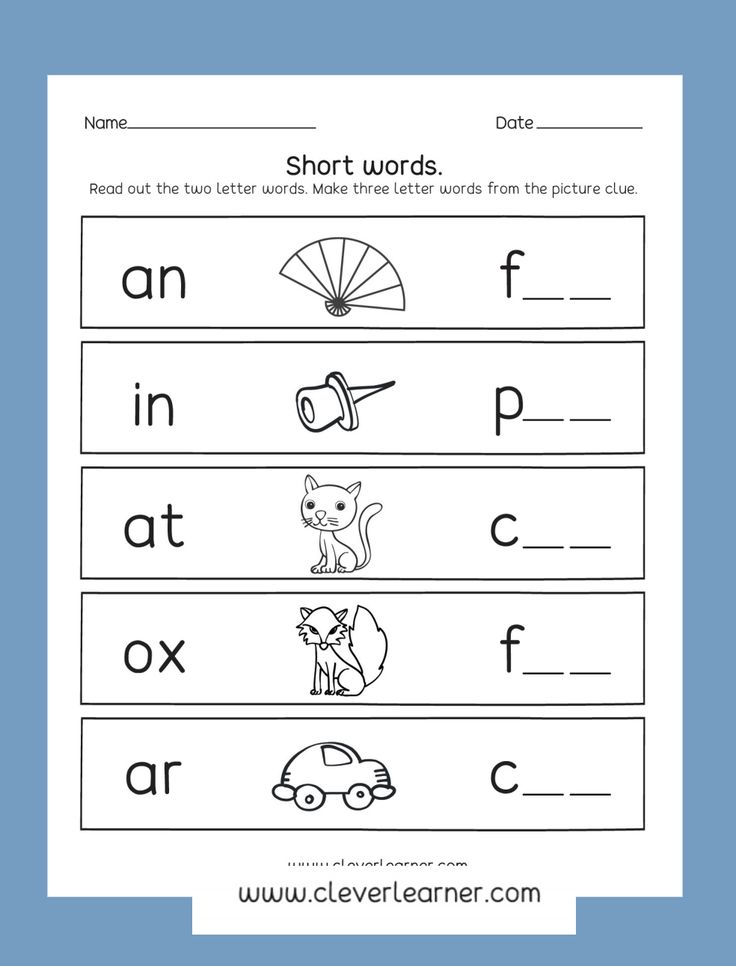

Letter-like forms and shapes

At this stage of writing development, children begin to display their understanding that writers use symbols to convey their meaning. Writing begins to include shapes (circles, squares) and other figures. A writer in this stage will often write something and ask, "What does this say?" There's little orientation of forms and shapes to space (i.e., they appear in random places within the writing or drawing). Tubs of markers, crayons, and paper remain good writer's tools.

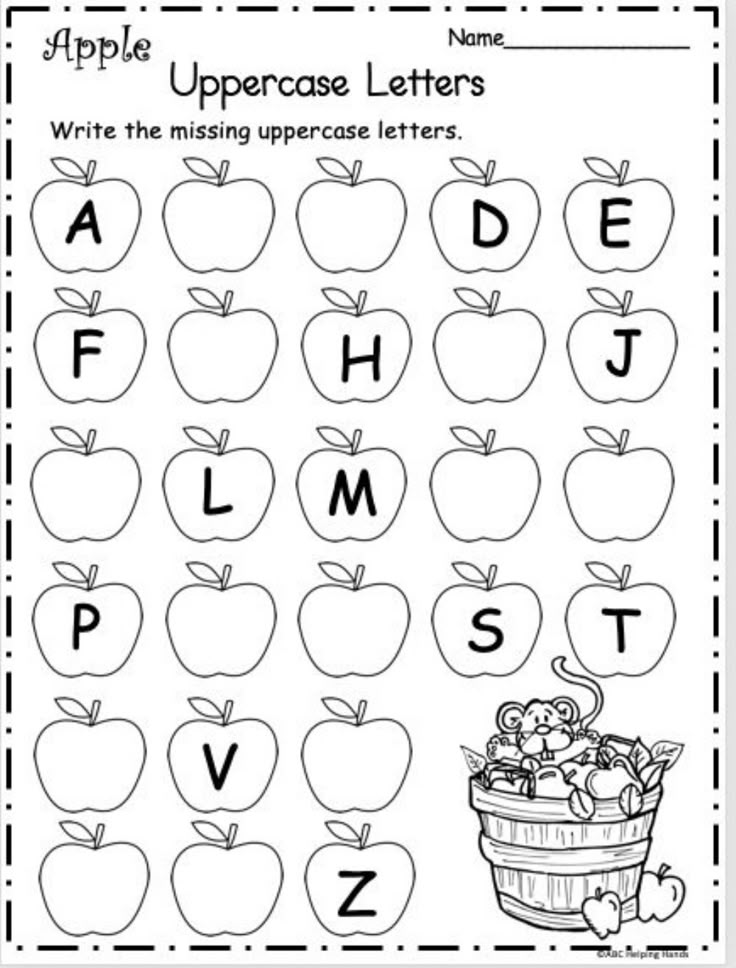

Letters!

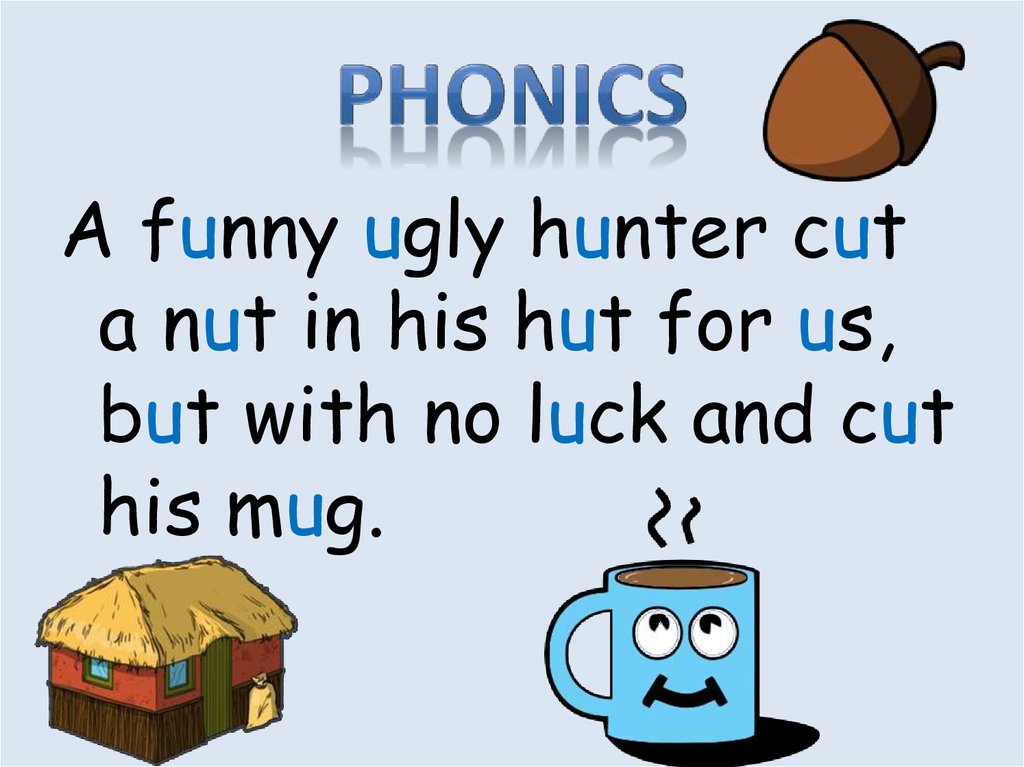

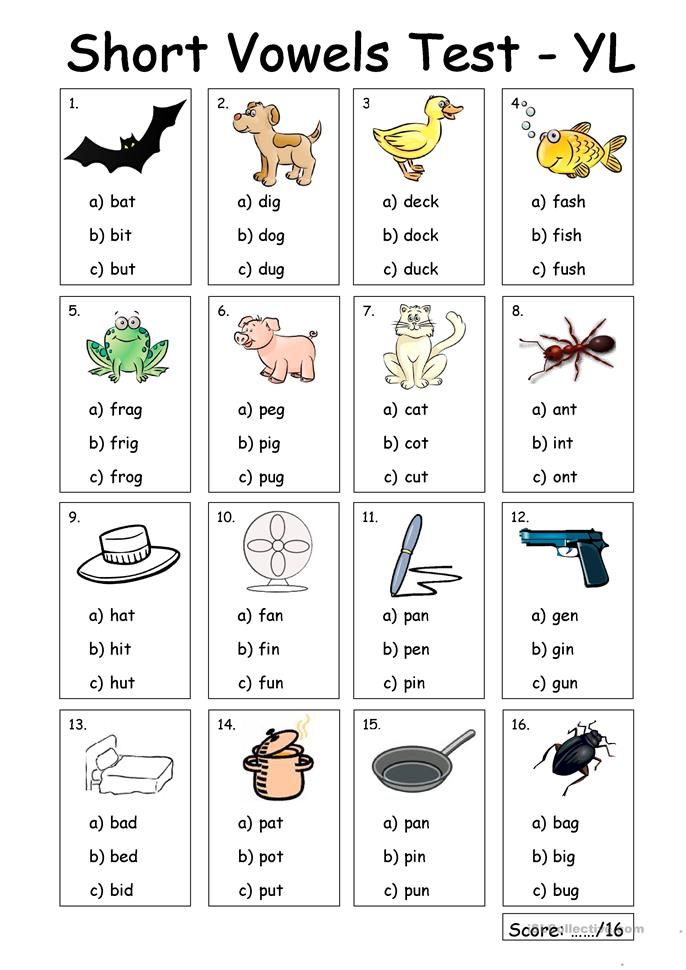

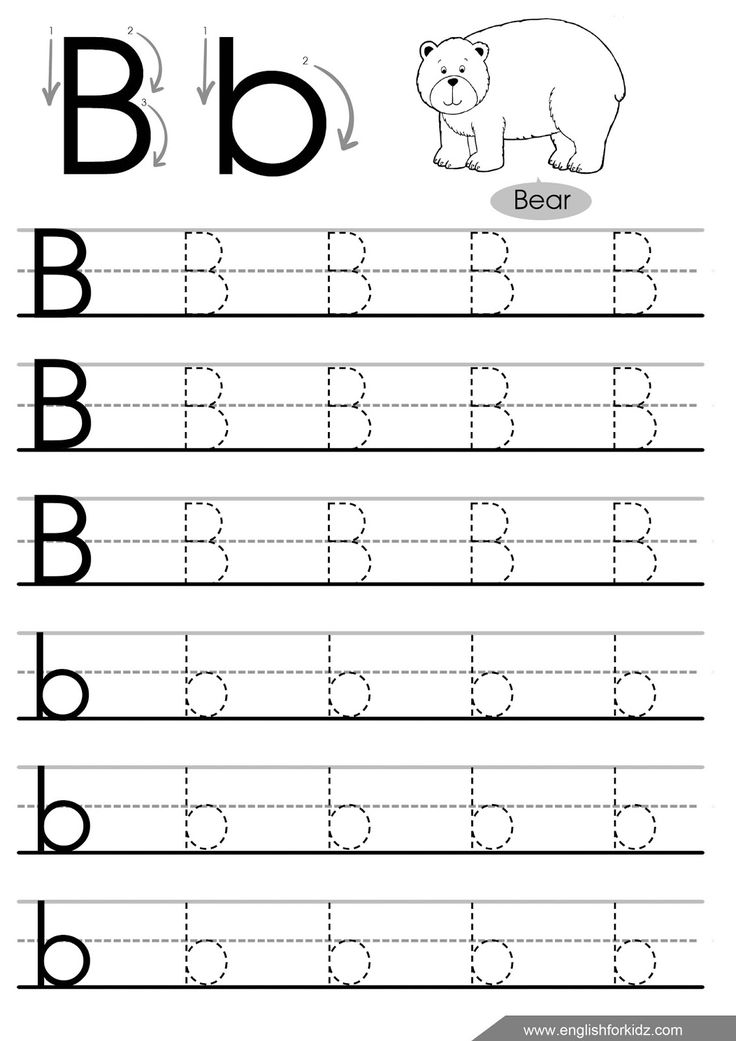

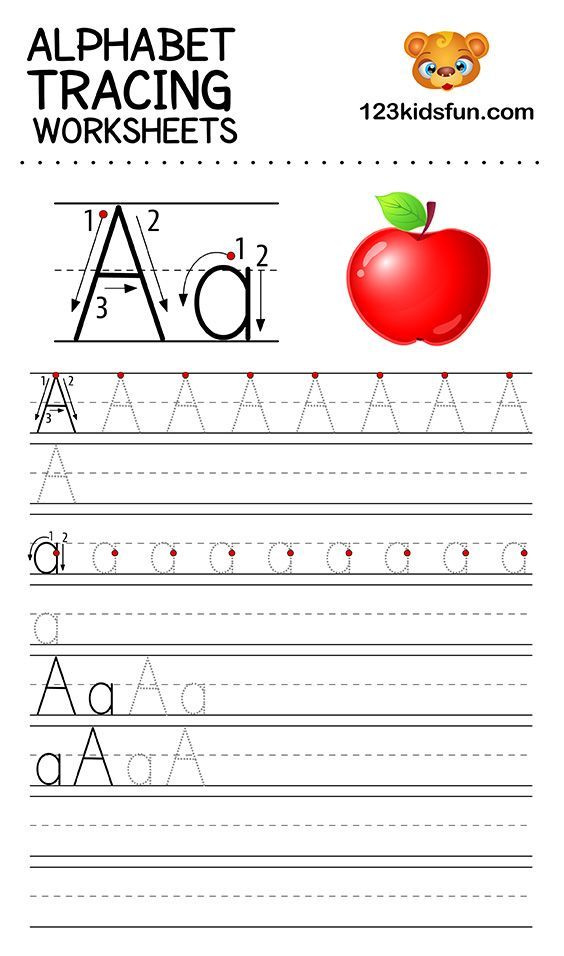

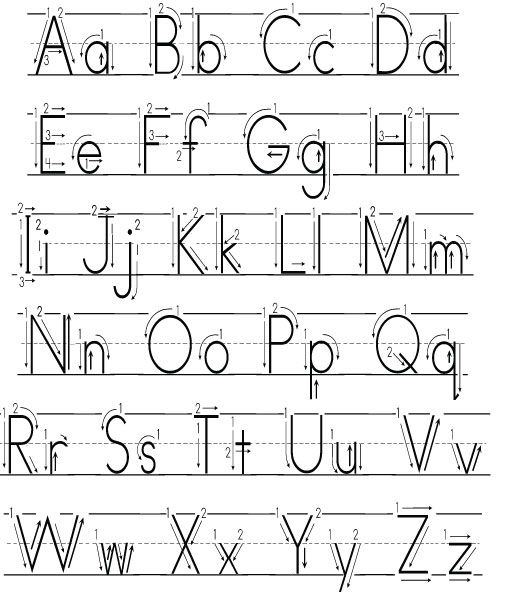

As a child's writing continues to develop, she will begin to use random letters. Most children begin with consonants, especially those in the author's name. Pieces of writing are usually strings of upper-case consonants, without attention to spaces between words or a sense that writing moves left to right and top to bottom. At the beginning of this stage, there remains a lack of sound-to-symbol correspondence between the words they are trying to write and the letters they use. Later efforts may include letters for the key sounds in words and include the author's own name. Different types of paper, including memo pads, envelopes, lined paper and some smaller pens and pencils are good writer's tools at this stage. Tubs of foam letters and letter magnets are also handy.

At the beginning of this stage, there remains a lack of sound-to-symbol correspondence between the words they are trying to write and the letters they use. Later efforts may include letters for the key sounds in words and include the author's own name. Different types of paper, including memo pads, envelopes, lined paper and some smaller pens and pencils are good writer's tools at this stage. Tubs of foam letters and letter magnets are also handy.

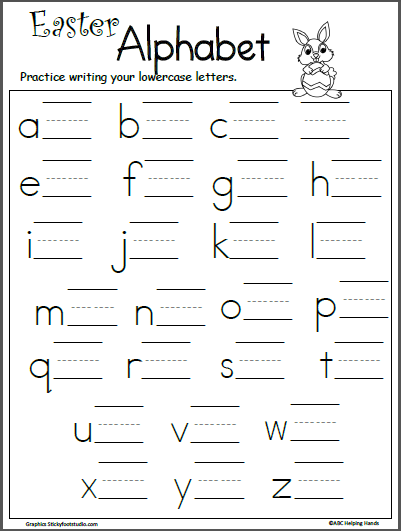

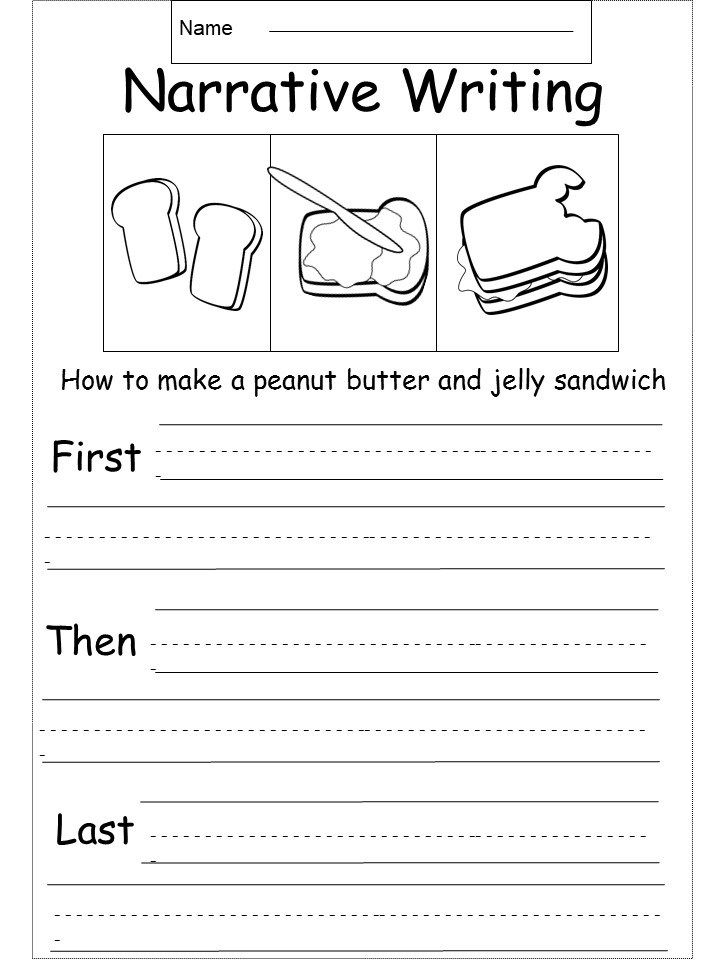

Letters and spaces

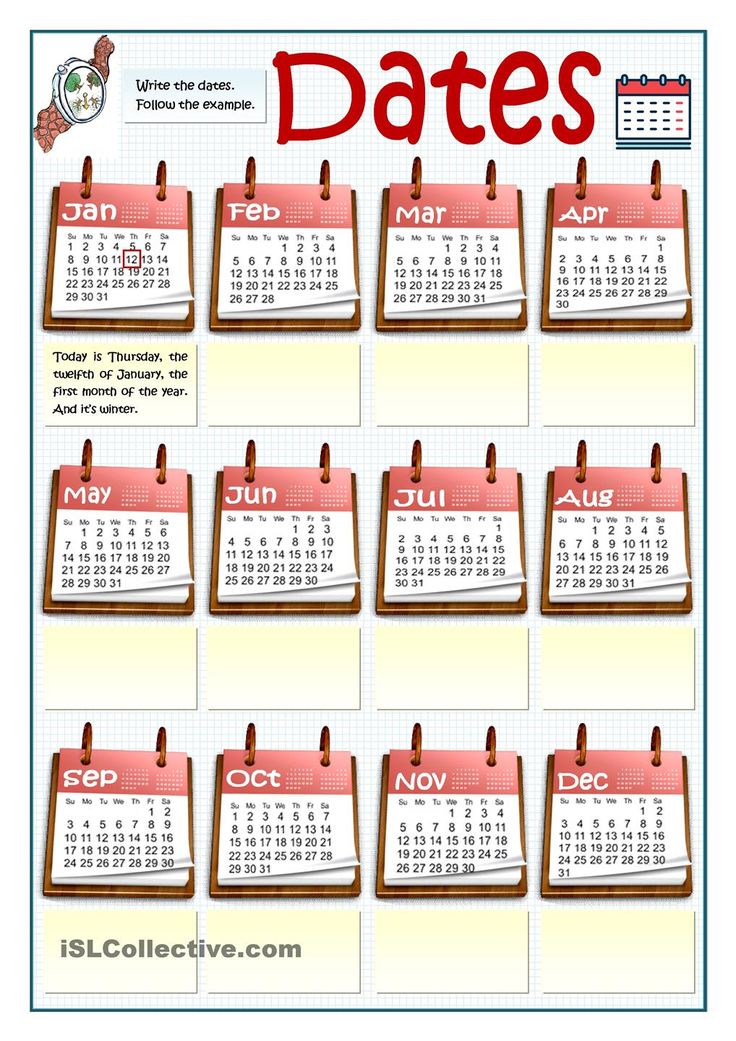

As beginning writers practice their craft, they are learning many concepts about print. When a child points to individual words on a page when reading, and works to match their speech to a printed word, a "concept of word" is developin — the awareness of the purpose and existence of spaces separating words and that spoken words match to printed words. It's a watershed event of kindergarten! Adults watch young writers insert these important spaces in their own work. Guided either by an index finger in-between each word or by lines drawn by the parent or teacher, children demonstrate one-to-one correspondence with words.

At this stage, children write with beginning and ending sounds. They also may begin to spell some high frequency words correctly. Vowels may be inserted into words. As children transition to more conventional writers, they will begin to write words the way they sound. Punctuation begins as writers experiment with forming sentences.

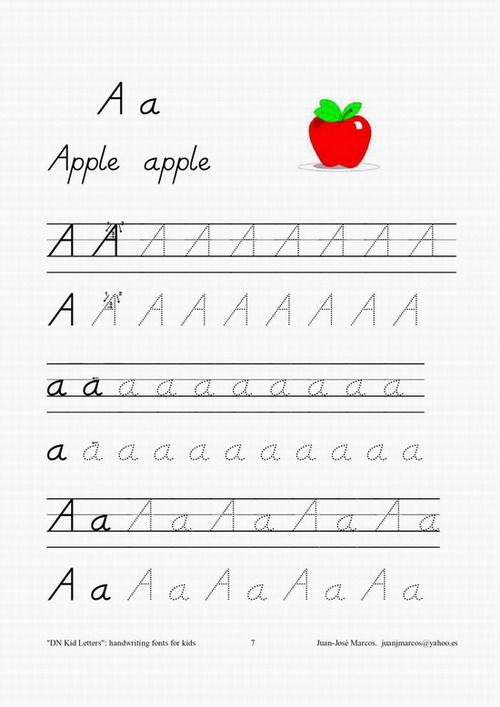

Conventional writing and spelling

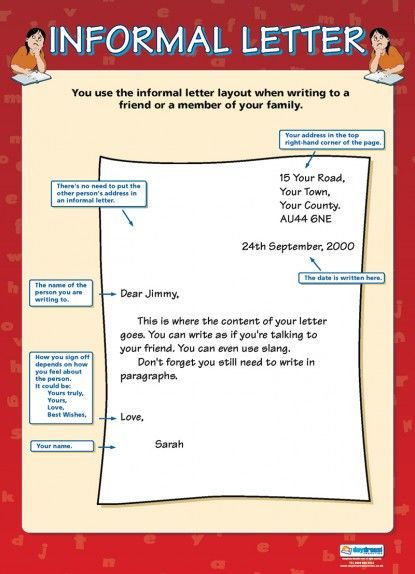

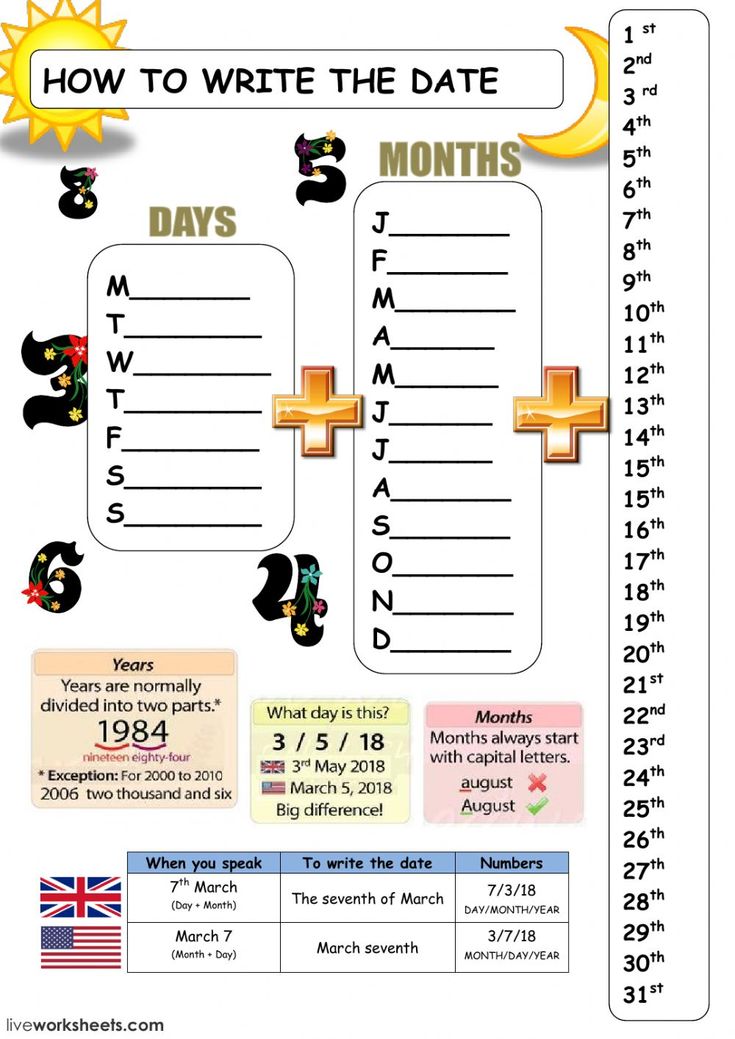

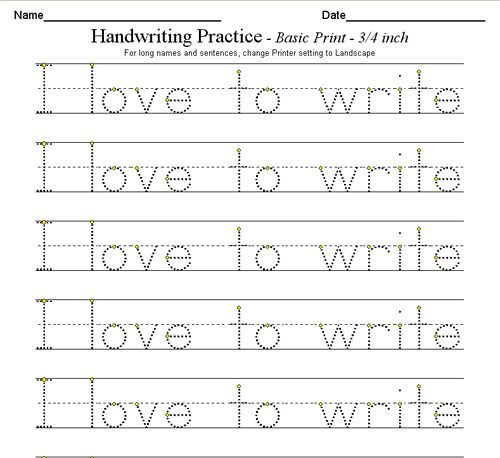

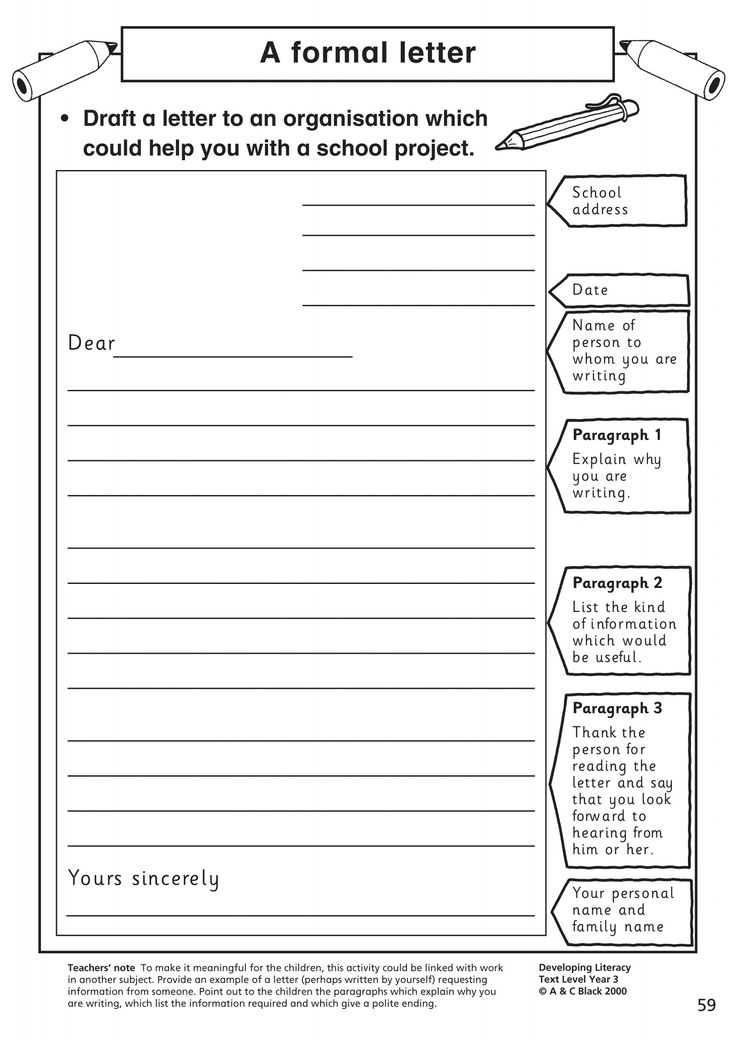

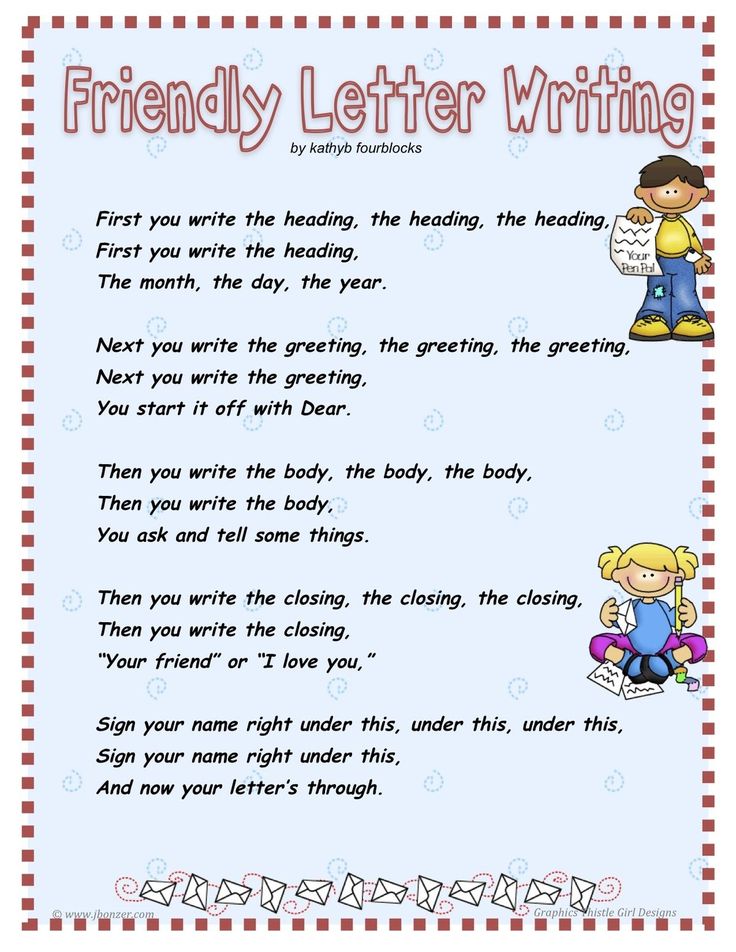

At this stage, children spell most words correctly, with a reliance on phonics knowledge to spell longer words. Writers use punctuation marks correctly and use capital and lower case letters in the correct places. Writing for different purposes becomes more important. First and second grade students often write signs for their bedroom doors or a letter to a friend. Storybook language, "Once upon a time," and "happily ever after," become a part of writing samples as the child joins the league of writers with a storytelling purpose. As students progress through the writing stages, various pieces become more automatic and fluent. Handwriting becomes easier, as does the spelling of a majority of words.

Handwriting becomes easier, as does the spelling of a majority of words.

At all stages, it's important to honor the writing efforts of your young child. Find opportunities to have your child share his work with others. Display efforts on the wall or on the refrigerator. Ask your child to read his work at the dinner table or by sitting in a special author's chair.

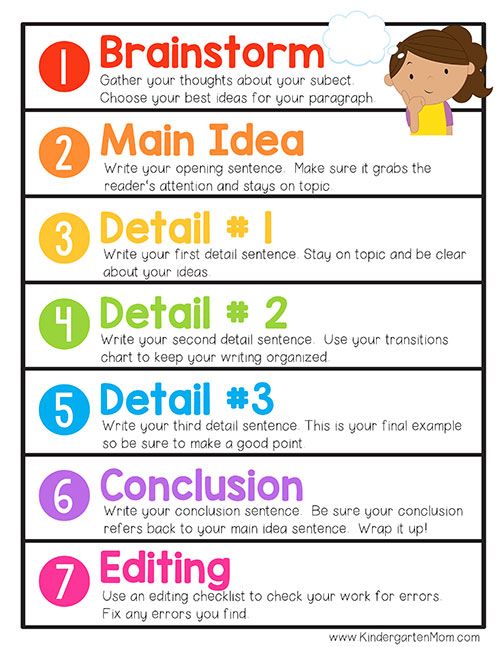

To write well, children need a broad set of skills

- Basic writing skills: These include spelling, capitalization, punctuation, handwriting or keyboarding, and sentence structure (for example, elimination of run-ons and sentence fragments). Basic writing skills are sometimes called the “mechanics” of writing.

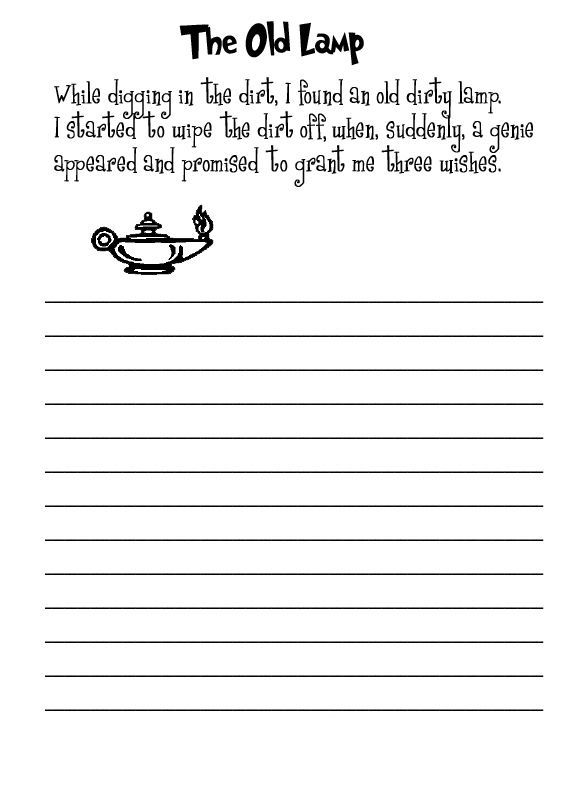

- Text generation: Text generation means translating your thoughts and ideas into language — the “content” of writing. Text generation includes word choice (vocabulary), details that add meaning, and clear expression.

- Writing processes: Good writing involves planning, revising, and editing.

These processes are extremely important to success in writing, and become even more important throughout a child's schooling.

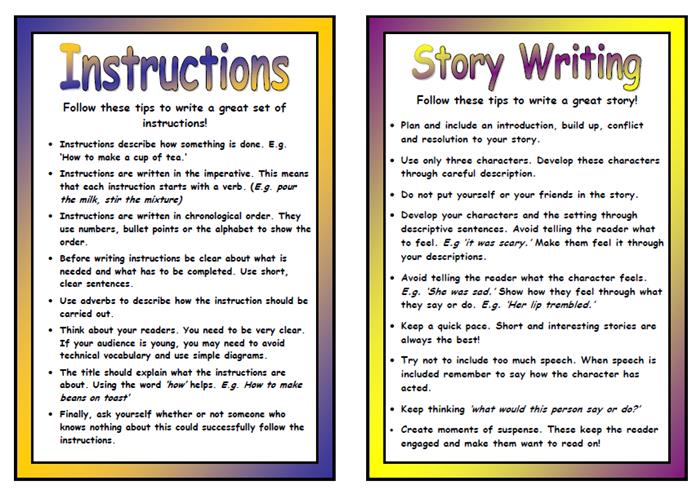

These processes are extremely important to success in writing, and become even more important throughout a child's schooling. - Writing knowledge: Writing knowledge includes an understanding types of writing (genre) — for example, understanding that narrative writing or descriptive writing is organized differently than informational writing or persuasive writing. Another eimportant part of writing knowledge is understanding the audience you are writing for.

"The primary goals of writing are to communicate, to persuade, to inform, to learn, to reflect about yourself, and also to entertain others. What really makes writing motivating for young children is sharing it and being successful with it."

Foster a love of writing at home for your child

This video is from Home Reading Helper, a resource for parents to elevate children’s reading at home provided by Read Charlotte. Find more video, parent activities, printables, and other resources at Home Reading Helper.

How to Write for Children in the Twenty-First Century

When writing for children, you have to strike a balance between being entertaining but not confusing; engaging but never patronising, and never making things unnecessarily complex.

How to write for children

First, and most importantly:

1. Read, Read, READ!

This is true for all writing, but it’s truer for YA and children’s fiction.

These are the age groups that are most flexible and ever-changing. It’s good to read what others are writing for your chosen age group(s). It helps to see how other authors tackle tone and complexity.

Adults tend to write in the style of books they grew up reading, which can be much-loved brilliant classics, but this doesn’t mean children of today will find them engaging. If the dialogue is dated, children will notice and feel alienated.

If the dialogue is dated, children will notice and feel alienated.

Write for the generation of today, not what you would’ve wanted to read when you were a child.

[bctt tweet=”Write for the generation of today, not what you would’ve wanted to read when you were a child.” username=”aivlislopez”]

Children today DO have phones, tablets, access to the internet and to a whole array of technology. Keep this in mind when writing for them. So read, read, READ as many books as you can. Listen to children talk and interact (preferably children that are related to you– I don’t recommend hanging out at parks).

2. Be VERY aware of what age you’re aiming for

This will affect how you approach your writing.

Children’s fiction is comprised of various age groups, leading up to YA. After YA you have Adult Fiction, with the upcoming New Adult Fiction bridging the gap between them.

There’s a reason the children’s fiction shelves are split up according to age group. What interests an eight-year-old won’t hold an eleven-year-old’s attention.

What interests an eight-year-old won’t hold an eleven-year-old’s attention.

Younger children tend to prefer happy ‘safer’ endings, where order is re-established, whilst older kids like a bit more danger in the narrative—that’s not to say they don’t like their happy ‘safe’ endings too, just that the road to them can be slightly rockier. Explore the shelves at your local bookstore or library, have a look at the blurbs, and take note of what each age range prefers.

[bctt tweet=”Younger children tend to prefer happy ‘safer’ endings, where order is re-established…” username=”aivlislopez”]

3. Know that kids are honest readers

And by this I mean brutally honest.

If your book bores them, they will likely be vocal about it—they might complain to their parents who bought it for them, or the teacher who assigned it as reading material. This will make them less likely to buy or recommend your books in the future.

Children will put the book down and never come back to it. They don’t have the attention span or patience adults have where they think, ‘Oh, maybe the narrative will pick up in a few pages.’ No. This does not work at early ages (and to be honest, you shouldn’t be doing this in other fiction either).

They don’t have the attention span or patience adults have where they think, ‘Oh, maybe the narrative will pick up in a few pages.’ No. This does not work at early ages (and to be honest, you shouldn’t be doing this in other fiction either).

Keep things immediate—every chapter needs to move the story along—and yes, this does go for ALL writing but is way more unforgivable in children’s fiction.

4. Trust children as readers

Don’t talk (or write) down to them—they can tell when you are.

Children are far more perceptive than some adults give them credit for.

Don’t dumb plots down for the sake of fitting into an age range. Instead, spend some time adding a few explanations and allow them to piece it together for themselves without getting too complex.

[bctt tweet=”Don’t dumb plots down for the sake of fitting into an age range.” username=”aivlislopez”]

Stories for children must be clear and easy to follow. Kids won’t spend the time puzzling out an overly-complicated plot.

This doesn’t mean to say that you must spell everything out for them, just keep it simple—no unnecessarily complex sentences or ideas that go around in circles. I’ll reiterate my earlier point: it’s all about striking a balance.

5. Remember adult and children’s senses of humour are very different things

Children and adults don’t find the same things funny. This seems quite an obvious statement, but when writing for children and you’re ‘in the zone’ things can slip onto the paper that you yourself as an adult will find amusing, but will not go down as well with children.

If you’ve ever watched a children’s film with kids, you’ll notice you will laugh or chuckle at different parts. Make note of what makes them laugh and use that knowledge within your writing.

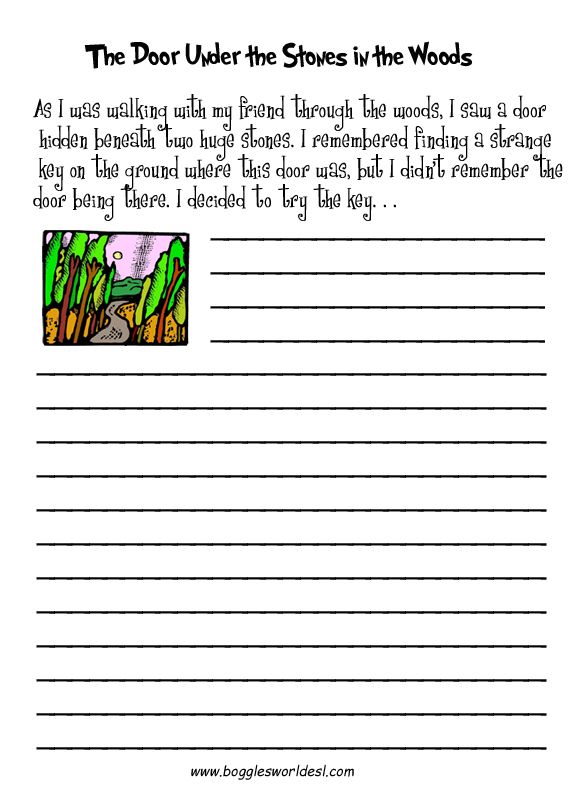

6. Keep it visual

Don’t overcomplicate set-ups. If things are hard to picture, you could lose a child’s interest. This includes the physicality of scenes such as who’s standing where during a playground face-off. These can be important things children will pick up on.

These can be important things children will pick up on.

7. Avoid two-dimensional characters

Characters in children’s books must immediately jump off the page and grab your attention. There’s no time to delve into long backstories. That’s not to say you can’t add some background in, just that a lot rides on first impressions of characters. A boring main character that you can’t get a grasp on and find it hard to identify with can damage your story in any kind of writing.

[bctt tweet=”A boring main character that readers find it hard to identify with can damage your story.” username=”aivlislopez”]

And finally, just in case I haven’t said it enough:

Read, Read, READ!

Over to You

What tips do you have for writing for children? What’s your favourite/least favourite thing about writing for them? Let us know in the comments below!

Last updated: 29/01/17

How to write a children's book - step by step instructions

We talk about genres of children's literature, features of children's books and audiences of different ages.

What is children's literature?

Children's literature is intended for children from 0 to 16 years old. These books perform several functions: on the one hand, they entertain young readers, and on the other, they educate and teach new and useful things.

According to the genre in children's literature, the following areas are distinguished:

Fiction. This includes fairy tales and epics, poems, short stories, stories, novels and comics.

Popular science literature: reference books, encyclopedias and monographs.

Developing and educational literature

By age, books for children are divided into:0012 age (7-10 years old)

Youth literature (11-16 years old). Recently, works for children of senior school age have been separated into their own direction, called Young Adult, or books for young adults.

Which children's books are popular in electronic form?

It is believed that children do not read in e-books, because parents tend to limit the use of electronic gadgets, and e-books will not convey some qualities of a paper book (for example, tactility).

However, if a child only reads from a tablet screen, then let him learn to read in a way that is convenient for him. Since he is still sitting with the gadget, why not spend this time on something useful?

Encyclopedias, books about space, professions and growing up, educational publications, adventure novels and fairy tales, as well as the works of Astrid Lindgren, Eleanor Potter, Mark Twain, Kir Bulychev, Ian Larry and Mayne Reid.

Most importantly, remember that even if the reader of the e-book is a child, the decision to purchase will be made by the parents, first of all, by the mother, so it will be necessary to interest her.

What is important for a children's book

If you want to write a book for children, you should consider the following points:

Topics should be interesting to children and understandable to parents.

Equal conversation.

As a rule, children's literature is required to be written in simple and understandable language. However, the child will understand a few incomprehensible words (after all, learning new things is one of the main functions of books for children), but he may not forgive lisping and condescension. He will have enough instructive tone in conversations with parents, teachers and educators, but if an interesting book written by an adult appeals to him on an equal footing, you will become his best friend for many years.

The hero must be his own.

If you are writing fiction for children, then the main character should be close to your audience, preferably the same age as her or a little older, so that the reader can identify with him. He has a characteristic feature that distinguishes him from the general background. The goals of the protagonist are clear to the audience, and he himself is a positive character, but has a number of shortcomings that he has to deal with.

He has a characteristic feature that distinguishes him from the general background. The goals of the protagonist are clear to the audience, and he himself is a positive character, but has a number of shortcomings that he has to deal with.

Happy ending.

Leave bad endings for adult literature and real life, in children's books at the end, good must triumph over evil, and good characters must triumph. The bad pirates will be defeated and remain on the island, Luke Skywalker will blow up the Death Star, and Tom Sawyer will repaint the fence. Only this way, and nothing else.

How to write a children's book

Decide on an audience

Who do you write for, girls or boys? And what age? Everything depends on the gender and age of your readers, from the subject and volume of the book to the development of the plot and the number of words in a sentence. The younger the reader, the shorter the sentences and the simpler the words. An older reader will already prefer more complex and entertaining stories (adventure, science fiction, horror stories), so morality will have to be hidden deeper.

An older reader will already prefer more complex and entertaining stories (adventure, science fiction, horror stories), so morality will have to be hidden deeper.

Research the market and meet the competition

Look for unhackneyed topics that are of personal interest to you. Reread the classics and analyze what exactly made this or that work a classic. Fairy tales are an inexhaustible (and still in the public domain) source of archetypal plots that can be twisted in your own way, while at the same time preserving images recognizable to the reader. The author of children's books will receive invaluable help from The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, Morphology of a Fairy Tale by Vladimir Propp, and The Golden Bough by James Fraser.

Decide on the topic of the book

Ask yourself two questions: what do I want to teach them and what topics to cover?

Decide on how to submit

Do you write fiction or non-fiction?

Be simpler

As we have already understood, a young reader will master a couple of clever words. However, if the whole book is written in boring abstruse language, the child will quickly get bored and lose interest. Keep sentences shorter, avoid borrowed and obscure words, and try to speak in plain language. Don't split the story into too many parallel storylines. And be specific in the descriptions - the child's imagination will work better if he knows that not just a bird is sitting on a tree, but, say, a ruffled tiny titmouse with gray wings and a bright yellow belly.

However, if the whole book is written in boring abstruse language, the child will quickly get bored and lose interest. Keep sentences shorter, avoid borrowed and obscure words, and try to speak in plain language. Don't split the story into too many parallel storylines. And be specific in the descriptions - the child's imagination will work better if he knows that not just a bird is sitting on a tree, but, say, a ruffled tiny titmouse with gray wings and a bright yellow belly.

Learn something

A book can teach anything from the importance of friendship, love, and family to the difficulty of sailing and the need to obey traffic rules, but a child should know a little more at the end of the book than at the beginning .

Get ready for serialization

Children love reading stories about their favorite characters, and this opens up a lot of room for creativity. The scheme of all stories may be the same, but the scenery must change - this will allow readers to learn and learn much more. Tom Sawyer can become a detective and go abroad, Dunno can visit the Moon and the Sunny City, and Tufo the red cat can get into the village, school, television and even a ship.

Tom Sawyer can become a detective and go abroad, Dunno can visit the Moon and the Sunny City, and Tufo the red cat can get into the village, school, television and even a ship.

Do not limit the flow of imagination

Dream. Remember how you yourself were children and what stories you made up in childhood. If you have children, ask what interests them. Find something mysterious and magical in the banal and mundane.

Many authors say they became writers by deciding to write a book that they would be interested in reading for themselves. A children's writer thus writes a book that he himself lacked in childhood . Well, if you already have children, write a book that they would like to read.

| Publish your book |

Was this article helpful to you?

Other articles on our blog:

The best children's and teen books. February 2021

Think for yourself: an open ending in books

How to write regularly?

How to write a novel

How to write and publish children's books - T&P

To become a smart adult, you need to read books from childhood.

But who and how creates and publishes literature for schoolchildren and preschoolers? T&P contacted writer Stanislav Vostokov and editor-in-chief of the Samokat publishing house Irina Balakhonova to find out how to write a children's book and what difficulties those who publish such books face.

But who and how creates and publishes literature for schoolchildren and preschoolers? T&P contacted writer Stanislav Vostokov and editor-in-chief of the Samokat publishing house Irina Balakhonova to find out how to write a children's book and what difficulties those who publish such books face.

“We really miss books about the most common things: about the garden, about construction, about veterinarians”

Stanislav Vostokov

children's writer, naturalist

Anyone who wants to become a children's author, primarily a writer, must know children and imagine what they can understand and what not. This, in my opinion, is the main thing. Of course, you need to have a good command of the topic and be familiar with books written on this topic earlier, so as not to "reinvent the wheel". In general, in my opinion, it is important to know children's literature well - only then you can try to climb on the notorious "shoulders of giants". Although some believe that it is better, on the contrary, not to read the predecessors, so as not to fall under their influence. There is, of course, such a danger. But I rather share the first point of view.

There is, of course, such a danger. But I rather share the first point of view.

S. Vostokov, "The Winter Door"

To write a children's book, it is desirable to be young. Very few authors started writing late and succeeded. For example, Astrid Lindgren or Dick King-Smith. In general, the older the writer, the less children's books he writes. Although, of course, there are exceptions - for example, the wonderful Mikhail Yasnov.

No need to write long and complicated. As for the rest, it seems to me that the author needs to adhere to the same rules as in adult literature. For example, you should try not to fall into someone else's style. Although almost all authors went through this, including those who later became classics. At the first stage, it may even be useful to, say, learn some literary techniques. But it is important not to play another author. And of course, you need to avoid templates, different "fiery eyes" and "red dawns".

Children love to read about almost anything as long as it is well written. Of course, girls have a craving for princesses, and boys for superheroes, but this is also better to avoid. These topics already border on bad taste. At the same time, we really miss books about the most common: about the garden, about construction, about veterinarians... Books on these very necessary topics, unfortunately, are usually translated.

Of course, girls have a craving for princesses, and boys for superheroes, but this is also better to avoid. These topics already border on bad taste. At the same time, we really miss books about the most common: about the garden, about construction, about veterinarians... Books on these very necessary topics, unfortunately, are usually translated.

“The Winter Door”, Stanislav Vostokov, illustrations Maria Vorontsova

Should we simplify? Everything depends on the author. Yuri Koval is a wonderful master of prose, but for most children this test is too high, they simply do not understand it. Koval said that his books are "for the little Pushkin", in other words, for the prepared reader. And the books of no less remarkable Viktor Dragunsky (the author of "Deniska's stories" - approx. ed. ) and Eduard Uspensky (author of books about Cheburashka, Uncle Fyodor and others - approx. ed. ) - for everyone. Readers are different and writers, respectively, should be the same. And then, in a simple style, you can write about very complex things. "Deniska's stories" is far from being as simple as it might seem at first glance. The style of Vera Chaplina is simple. But what portraits are painted in this style!

And then, in a simple style, you can write about very complex things. "Deniska's stories" is far from being as simple as it might seem at first glance. The style of Vera Chaplina is simple. But what portraits are painted in this style!

A children's writer has many different tools at his disposal, for example, creative word formation. And here everything depends on the task of the author. If such word formation is in place, it can become an excellent “seasoning”. For example, the "Republic of SHKID" would have lost a lot if it did not include Vikniksor, Kostalmed and others. But the main thing here is not to overdo it.

“Due to government layout requirements, our books for toddlers will never be as beautiful as those of the French or Americans”

Irina Balakhonova

editor-in-chief of the Samokat publishing house

Different children and parents read different books. Toddlers who have not yet read, for example, enthusiastically accept the Elmer series, the series of books about Max Barbra Lindgren, and Suzanne Berner's "Town" by Rotraut. Parents see them as an opportunity to develop new skills in their child, and children like books in which you can find something other than the actual story.

Parents see them as an opportunity to develop new skills in their child, and children like books in which you can find something other than the actual story.

Poems are still in demand among kids, but Soviet classics are in the lead here, while many adults, especially the older generation, do not always notice modern poets, who are in no way inferior to familiar authors. We believe that children's poetry should be published regardless of its commercial success: sooner or later a good poet will be tasted and loved. It is customary for us to read poetry to young children, and they are looking for a simple, memorable rhythm, simple rhymes, and an understandable plot. But, in my opinion, children can read any poets at any age.

If we turn to prose, then both children and parents love both traditional books and new writers. Moreover, in Russia, sometimes something that has long become a classic in the world turns out to be new. So, for example, it happened with Tomi Ungerer and Roald Dahl, and with many other authors. Now publishers who take the risk of doing something new have translated books that have already entered the school curriculum in their native countries, and for us they are becoming a discovery. And, like everything new, readers sometimes perceive them ambiguously.

Now publishers who take the risk of doing something new have translated books that have already entered the school curriculum in their native countries, and for us they are becoming a discovery. And, like everything new, readers sometimes perceive them ambiguously.

"Sirs and Dragons", Stanislav Vostokov, illustrations by Natalia Gavrilova

Now there are many children's books that adults read with pleasure. Among our authors are Maria Parr, Rune Belswick, Daniel Pennack, Natalia Evdokimova, Peter van Gestel. Parents start reading such books to their children and get carried away themselves. Many modern authors write without trying to write "for children" - rather, they appeal to the child in themselves and thus resonate with adults. And this is not infantilism, not a desire to fall into childhood, but an attempt to regain a sense of wholeness.

Well, I must say separately about reissues. Now there is a huge amount of “vintage” on the market: not just texts are reproduced, but the entire publication is reproduced, with drawings and design “from our childhood”. This increases sales, parents are happy to take such books, but children are not always willing to read them. Because not everything is a classic that is called it. And after such purchases, adults often wonder why children do not want to read excellently published books that they themselves read. That's why it makes sense to check everyone's "favorites" for relevance to the current moment in time and honestly ask yourself the question: would I choose these books now, or do I love them because they remind me of childhood?

This increases sales, parents are happy to take such books, but children are not always willing to read them. Because not everything is a classic that is called it. And after such purchases, adults often wonder why children do not want to read excellently published books that they themselves read. That's why it makes sense to check everyone's "favorites" for relevance to the current moment in time and honestly ask yourself the question: would I choose these books now, or do I love them because they remind me of childhood?

Children's publishing houses also select foreign books for translation, and this is a very painstaking job. We follow the most important awards in the field of children's literature, national and international, consult with colleagues from foreign publishers, librarians and literary critics from Europe and America, with translators. We ask them what they consider to be the best, what books they like (and we ask them not to take into account the commercial success of the book), what their children liked most. And we also read foreign professional press, after preliminary selection of texts we give them to our readers, study and discuss their reviews, read them ourselves - and then we already conduct the final selection.

And we also read foreign professional press, after preliminary selection of texts we give them to our readers, study and discuss their reviews, read them ourselves - and then we already conduct the final selection.

"Sirs and Dragons", Stanislav Vostokov, illustrations by Natalia Gavrilova

To find Russian authors, we follow literary awards and competitions, although there are not many of them in Russia: "Kniguru", "Krapivinka". We read the texts of winners, nominees, and if we like the author, we contact him as soon as possible. Unfortunately, sometimes texts are nominated for awards that have not yet been shown to any of the publishers. Each award has its own specifics, so if the author wants to try his hand, he must first get acquainted with what texts were selected for the competition before, and understand whether his (perhaps brilliant) text falls within this framework. If not, it is better to send it to a publishing house that is ready to take financial risks by publishing texts on "difficult" topics - such as "Scooter", for example - specifying that you are planning to participate in the competition.

When we work with texts that come to the address of the editorial office, the first selection is made by the editor of the Russian direction. Then we sometimes give texts to readers: among them there are children, teenagers and even adults. The best texts are read and discussed by the entire editorial board. Our task is to select the best in comparison not only with other Russian texts, but also with the best foreign texts, which, unfortunately, we still have about 70%. Sometimes we are accused of making it difficult for a Russian-speaking author to get into Samokat, even though he can count on translation into other languages. But we do not make discounts for the language.

As for the layout of children's books, in Russia this is a complicated matter: quite strict standards are set here.

This is a problem, and because of it, our books for toddlers will never be as beautiful and attractive to children as the books of the French or Americans, for example. But since some uncles and aunts, who were infinitely interested in the health of our children, decided back in the days of the USSR that it’s better for a child not to pick up a book at all than to “break his eyes”, then what can you do - we typeset in accordance with requirements.