Phonological awareness definition for parents

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: Activities for Your First Grader

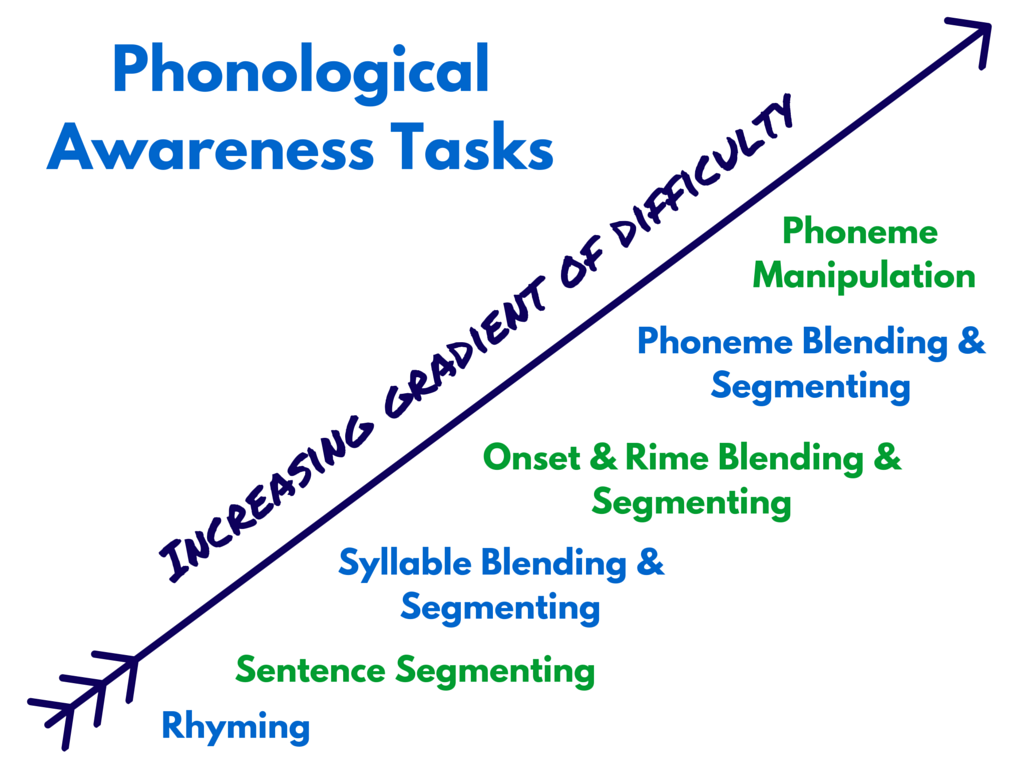

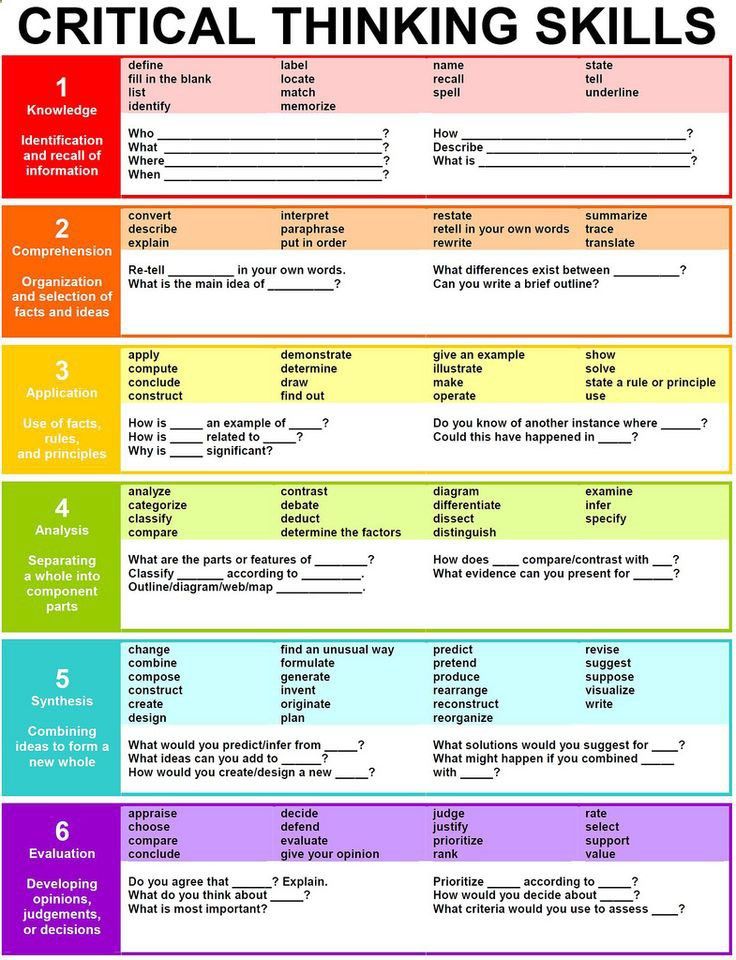

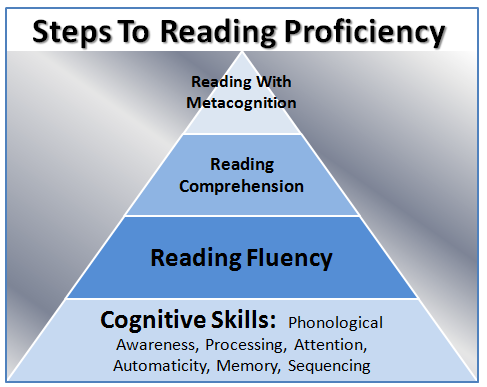

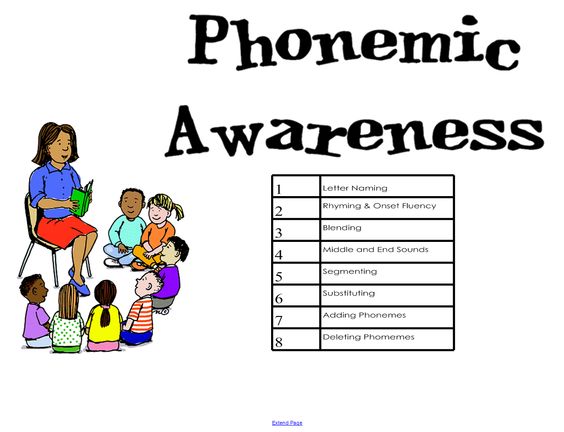

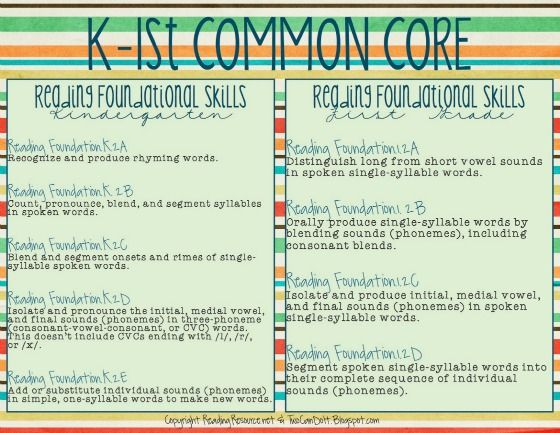

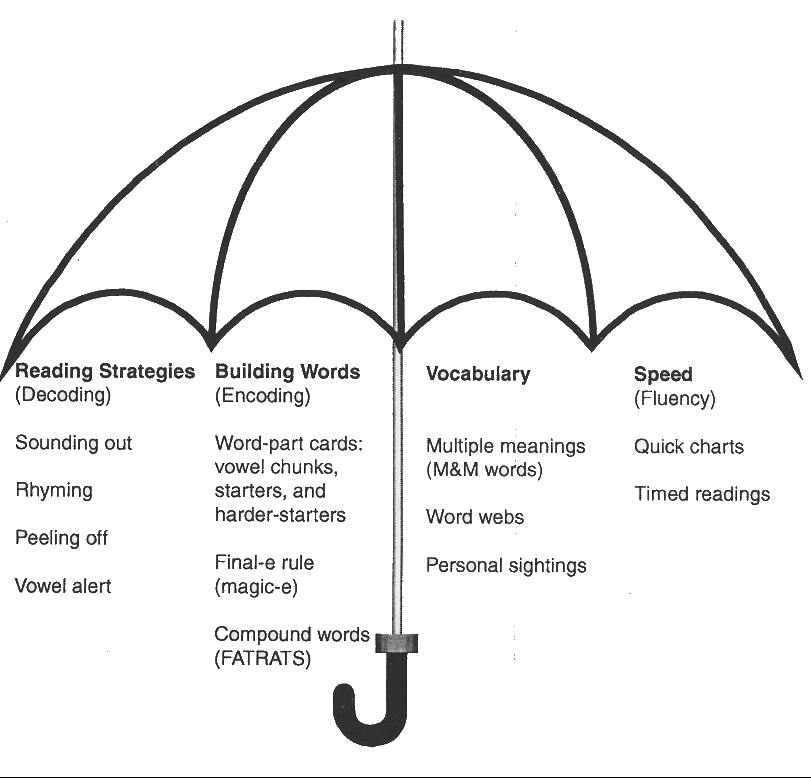

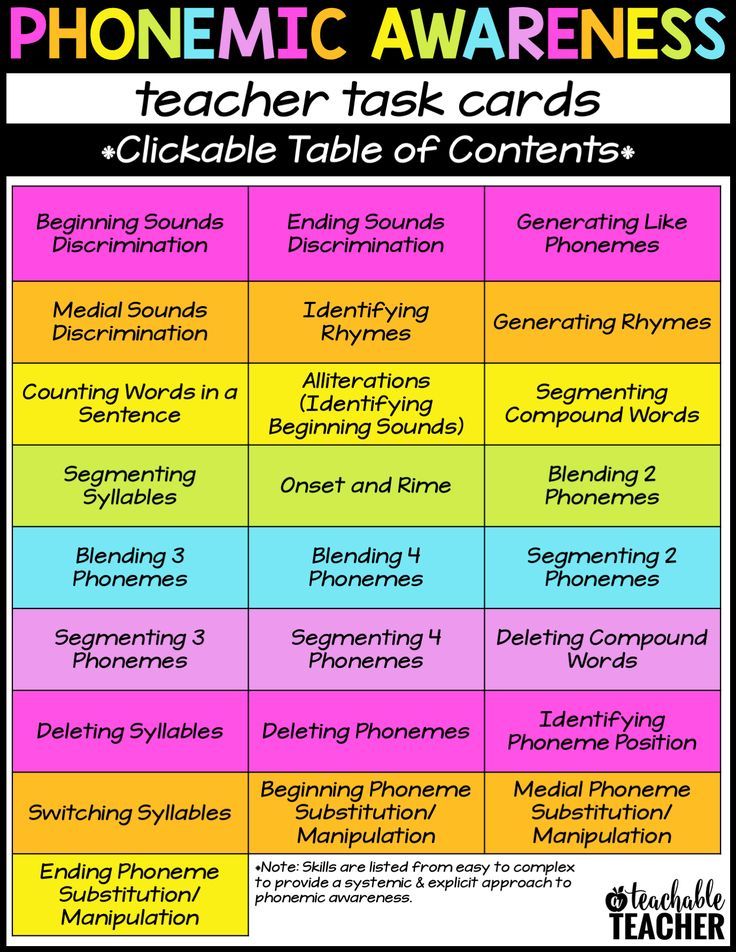

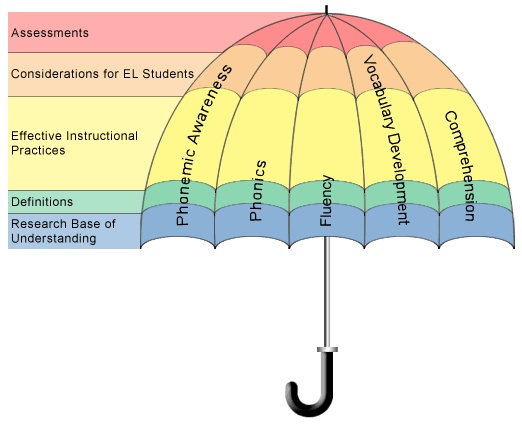

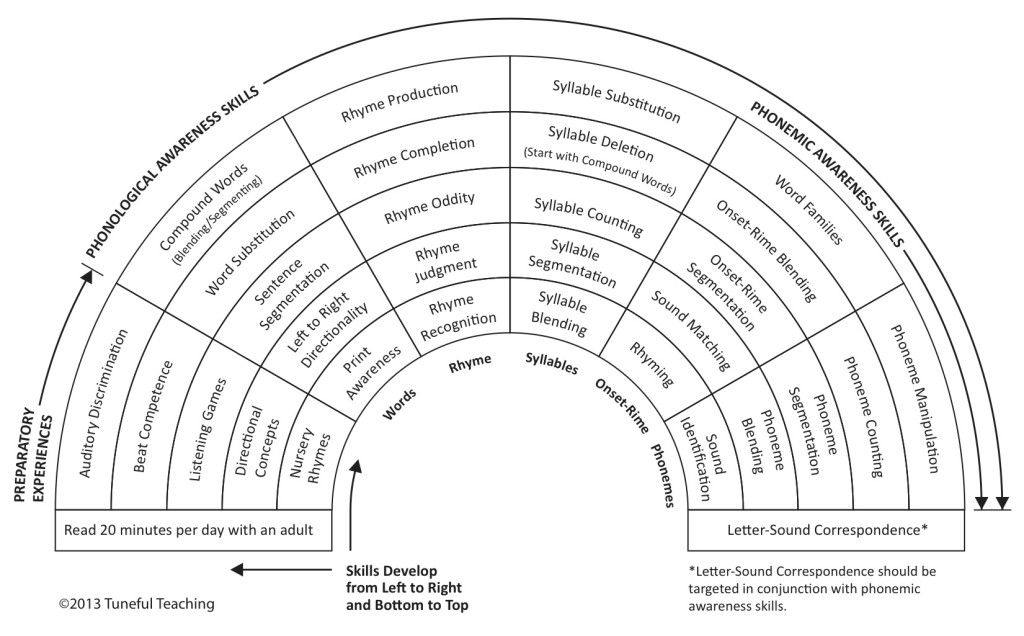

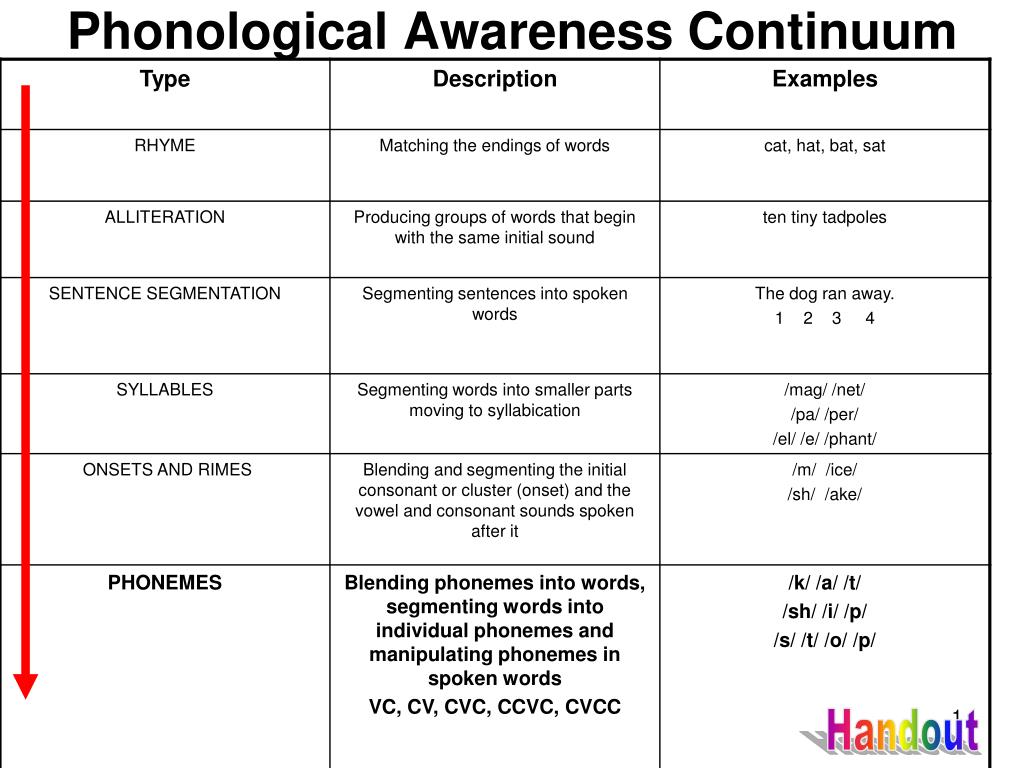

That's a complicated sounding term, but it's meaning is simple: the ability to hear, recognize, and play with the sounds in spoken language. Phonological awareness is really a group of skills that include a child's ability to:

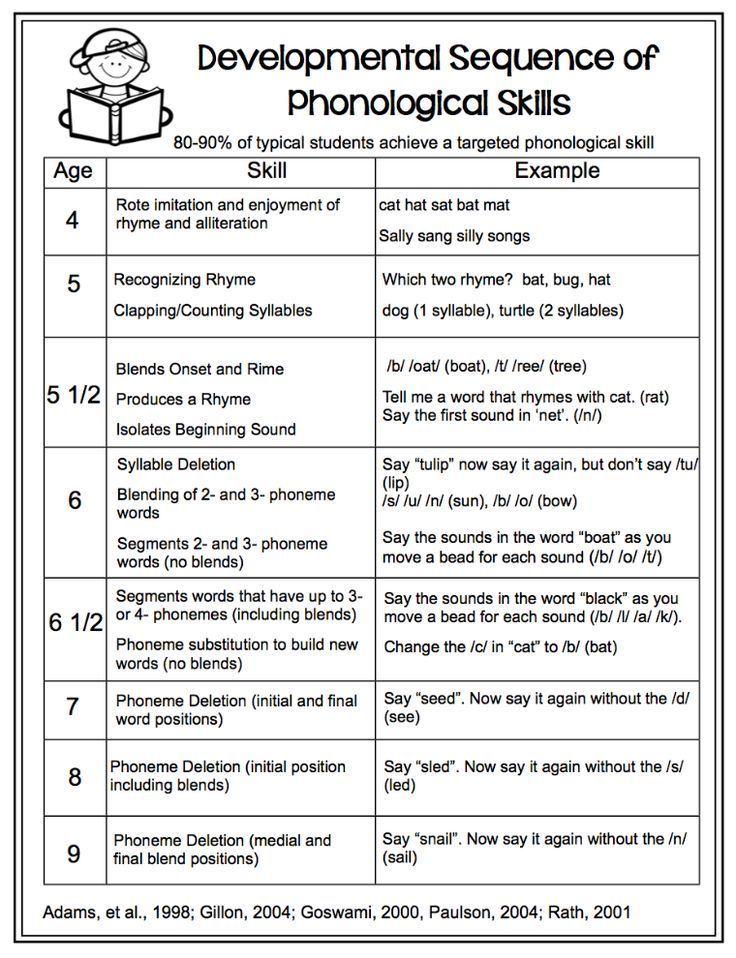

The most sophisticated phonological awareness skill (and the last to develop) is called phonemic awareness — the ability to hear, recognize, and play with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. When playing with the sounds in word, children learn to:

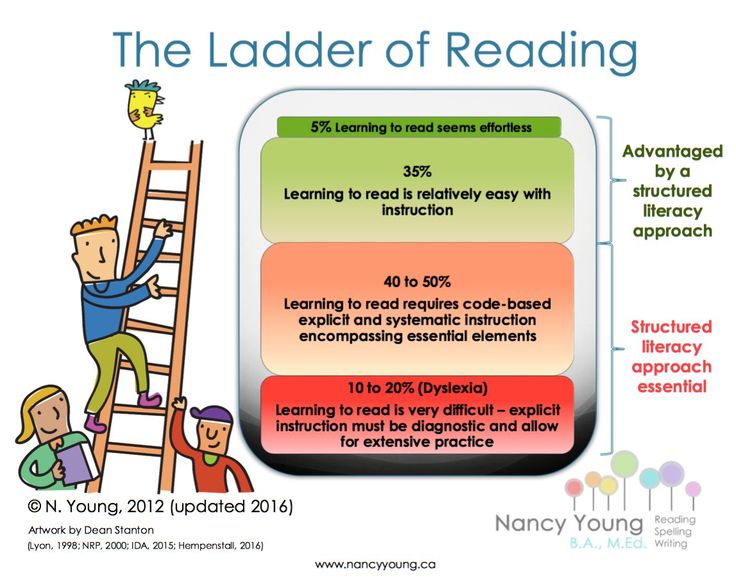

Strong phonemic awareness is one of the strongest predictors of later reading success. Children who struggle with reading, including kids with dyslexia, often have trouble with phonemic awareness, but with the right kind of instruction they can be successful. Learn some of the warning signs for dyslexia in this article, Clues to Dyslexia in Early Childhood.

Your first grader should be able to recognize rhyming words and create their own rhyming word pairs or sets (big, dig, fig). See if your child can also identify the first, middle and last sounds they hear in a word, and show you how many sounds are in simple one-syllable words using their fingers (sit = s-i-t = 3 sounds).

Parents can make a big difference in helping their children become readers by practicing these pre-reading oral skills at home. Try some of the simple rhyming and word sound games described here.

Why phonemic awareness is the key to learning how to read

This video is from Home Reading Helper, a resource for parents to elevate children’s reading at home provided by Read Charlotte. Find more video, parent activities, printables, and other resources at Home Reading Helper.

Try these speech sound activities at home

Syllable shopping

While at the grocery store, have your child tell you the syllables in different food names. Have them hold up a finger for each word part. Eggplant = egg-plant, two syllables. Pineapple = pine-ap-ple, three syllables. Show your child the sign for each and ask her to say the word.

Have them hold up a finger for each word part. Eggplant = egg-plant, two syllables. Pineapple = pine-ap-ple, three syllables. Show your child the sign for each and ask her to say the word.

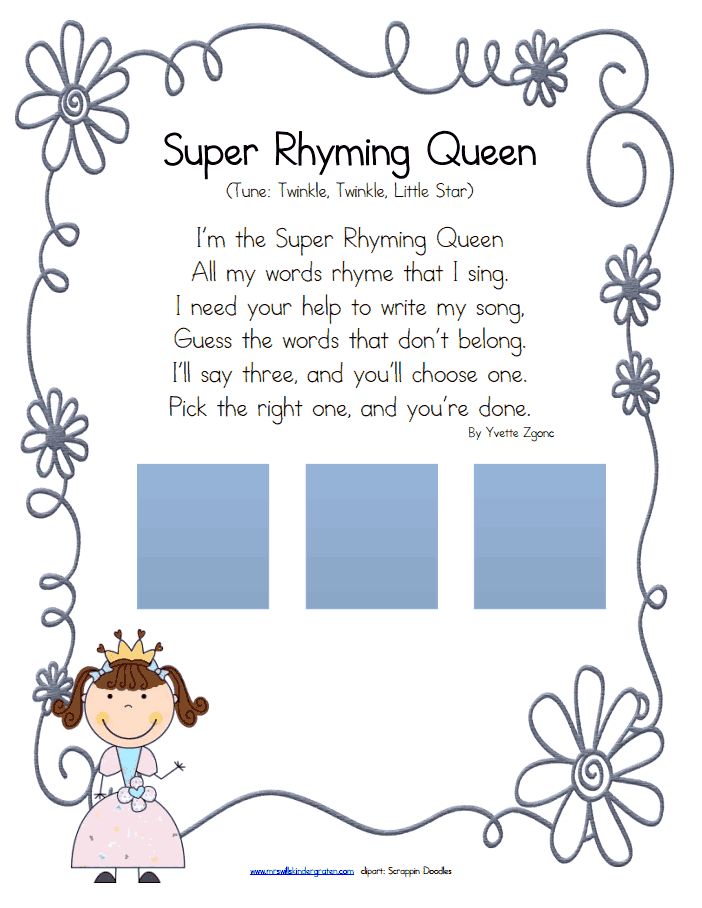

Rhyme time

“I am thinking of an animal that rhymes with big. What's the animal?” Answer: pig. What else rhymes with big? (dig, fig, wig)

Road trip rhymes

While you're out driving in the car, spot something out the window and ask your child, "what rhymes with tree or car or shop?" Then switch roles and have your child spot something and ask you for a rhyme. This can turn into a game of nonsense rhymes ("What rhymes with tree stump?") but that's great for practicing sounds, too!

Word families

Word families are sets of words that rhyme. Start to build your family by giving your child the first word, for example, cat. Then ask your child to name all the "kids" in the cat family, such as:

bat, fat, sat, rat, pat, mat, hat, flat. This will help your child hear patterns in words.

This will help your child hear patterns in words.

Silly tongue twisters

Sing songs, read rhyming books, and say silly tongue twisters. These help your child become sensitive to the sounds in words.

Sound games

Practice blending sounds into words. Ask "Can you guess what this word is? m - o - p." Hold each sound longer than normal.

One sound at a time

Certain sounds, such as /s/ or /m/are great sounds to start with. The sound is distinct, and can be exaggerated easily. "Please pass the mmmmmmmmilk." "Look! There's a ssssssssssnake!" It's also easy to describe how to make the sound with your mouth. "Close your mouth and lips to make the sound. Now put your hand on your throat. Do you feel the vibration?"

Tongue ticklers

Alliteration or "tongue ticklers" — where the sound you're focusing on is repeated over and over again — can be a fun way to provide practice with a speech sound. Try these:

- For M: Miss Mouse makes marvelous meatballs!

- For S: Silly Sally sings songs about snakes and snails.

- For F: Freddy finds fireflies with a flashlight.

"I Spy" first sounds

Practice beginning sounds with this simple game: ask your child questions like, “I spy something red that starts with /s/.”

Sound sleuth

Choose a letter sound, then have your child find things around your house that start with the same sound. “Can you find something in our house that starts with the letter “p” pppppp sound? Picture, pencil, pear”

"I Spy" blending

Here's an easy phoneme blending game you can play while talking a walk. For blending, you can say, “I see a sign that says s-t-o-p” Then your child has to blend the sounds to guess your word — stop. (Remember to say only the sounds in the word — not the letters.) Keep the words short, moving from two to three to four sounds depending on your child’s skill level.

Jump, skip, hop!

Create simple picture cards that you draw or cut out of magazines. Have your child, identify what's in the picture, and then break that word into its individual sounds. For example dog is d-o-g, three sounds (phonemes). Three sounds? You and your child do three jumping jacks, skips, or hops (followed by a high-five). You can also do this game outdoors without the cards, just call out simple words for your child.

For example dog is d-o-g, three sounds (phonemes). Three sounds? You and your child do three jumping jacks, skips, or hops (followed by a high-five). You can also do this game outdoors without the cards, just call out simple words for your child.

Snail talk

Tell your child you're going to communicate in "snail talk" and they need to figure out what you're saying. Take a simple word and stretch it out very slowly (e.g., /fffffllllaaaag/), then ask your child to tell you the word. Switch roles and have your child stretch out a word for you.

First sounds

When you’re reading together with your child, pick a word from the book and say it with emphasis on the first sound. Pick another word and compare them. “Zzz-zookeeper and rrr-rhinoceros. Can you hear what sound zzz-zookeeper starts with? Is it the same as rrr-rhinoceros?

Sound counting

Using LEGO bricks, beads, or pennies, say a word and have your child show you how many sounds the word makes. For example, top = t-o-p = three sounds, so your child would place three objects in a row. Then have them tap each object as they say the sound. Remember, your child is just showing you the sounds they hear. So the word bike would be = b-i-k (silent e) = only three sounds.

For example, top = t-o-p = three sounds, so your child would place three objects in a row. Then have them tap each object as they say the sound. Remember, your child is just showing you the sounds they hear. So the word bike would be = b-i-k (silent e) = only three sounds.

Rime house

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Rime House. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

Phoneme dominoes

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Phoneme Dominoes. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

Picture slide

Try this activity from the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR). The FCRR "At Home" series was developed especially for families! Watch the video and then download the activity: Picture Slide. See all FCRR phonological awareness activities here.

More phonological and phonemic awareness resources

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness | Reading Rockets

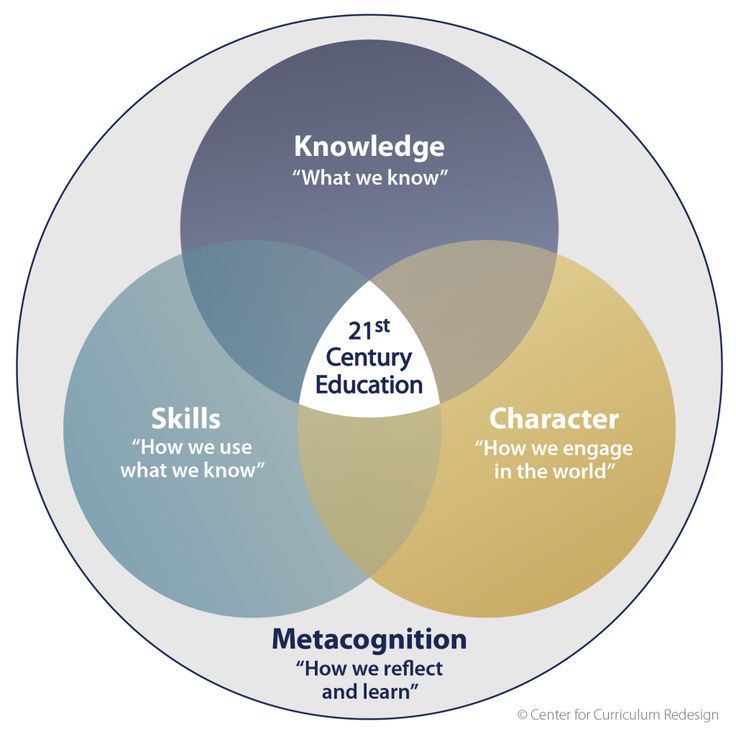

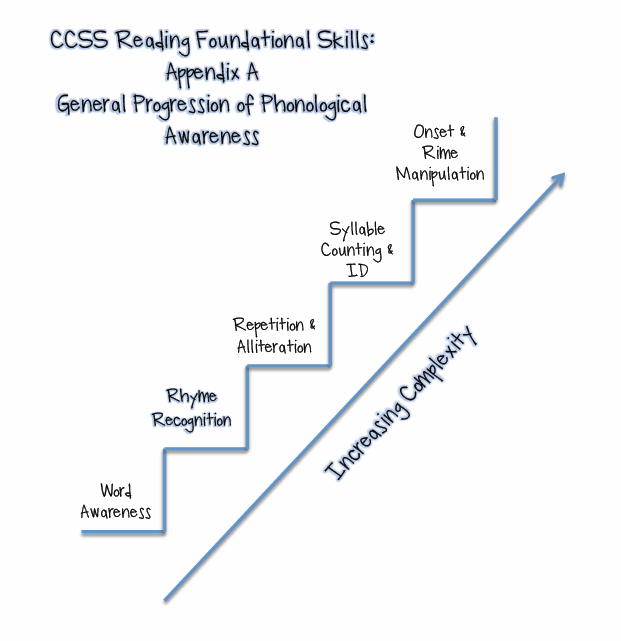

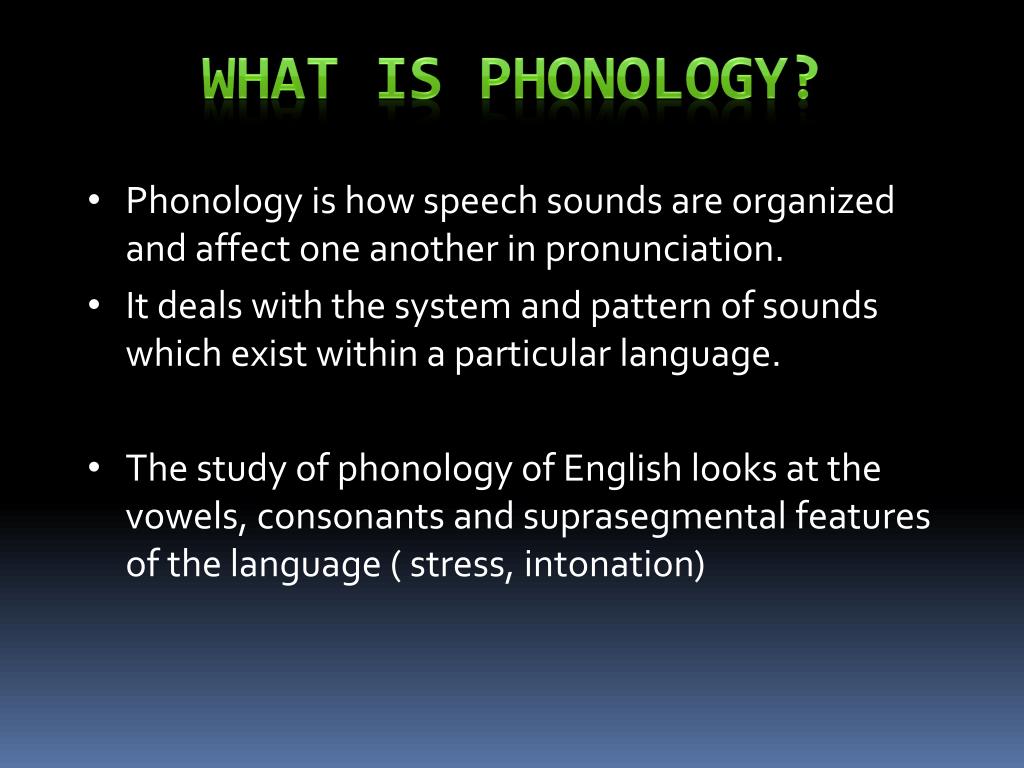

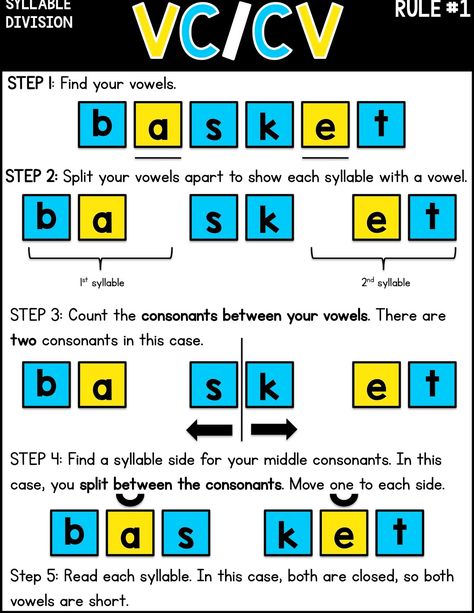

Phonological awareness is a broad skill that includes identifying and manipulating units of oral language – parts such as words, syllables, and onsets and rimes. Children who have phonological awareness are able to identify and make oral rhymes, can clap out the number of syllables in a word, and can recognize words with the same initial sounds like 'money' and 'mother.'

Children who have phonological awareness are able to identify and make oral rhymes, can clap out the number of syllables in a word, and can recognize words with the same initial sounds like 'money' and 'mother.'

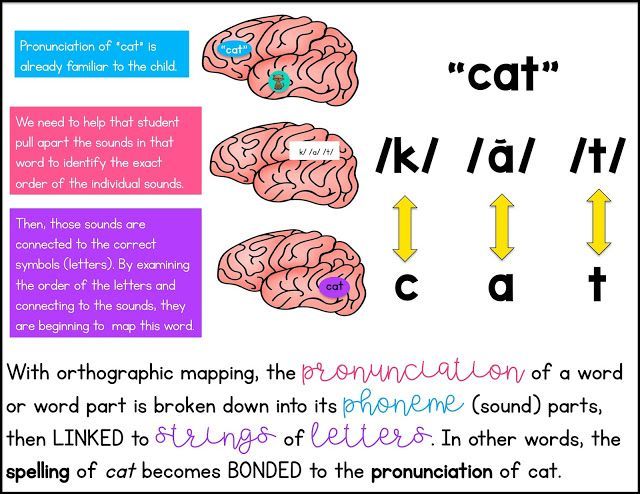

Phonemic awareness refers to the specific ability to focus on and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. Phonemes are the smallest units comprising spoken language. Phonemes combine to form syllables and words. For example, the word 'mat' has three phonemes: /m/ /a/ /t/. There are 44 phonemes in the English language, including sounds represented by letter combinations such as /th/. Acquiring phonemic awareness is important because it is the foundation for spelling and word recognition skills. Phonemic awareness is one of the best predictors of how well children will learn to read during the first two years of school instruction.

Students at risk for reading difficulty often have lower levels of phonological awareness and phonemic awareness than do their classmates. The good news is that phonemic awareness and phonological awareness can be developed through a number of activities. Read below for more information.

The good news is that phonemic awareness and phonological awareness can be developed through a number of activities. Read below for more information.

What the problem looks like

A kid's perspective: What this feels like to me

Children will usually express their frustration and difficulties in a general way, with statements like "I hate reading!" or "This is stupid!". But if they could, this is how kids might describe how difficulties with phonological or phonemic awareness affect their reading:

- I don't know any words that rhyme with cat.

- What do you mean when you say, "What sounds are in the word brush?"

- I'm not sure how many syllables are in my name.

- I don't know what sounds are the same in bit and hit.

A parent's perspective: What I see at home

Here are some clues for parents that a child may have problems with phonological or phonemic awareness:

- She has difficulty thinking of rhyming words for a simple word like cat (such as rat or bat).

- She doesn't show interest in language play, word games, or rhyming.

A teacher's perspective: What I see in the classroom

Here are some clues for teachers that a student may have problems with phonological or phonemic awareness:

- She doesn't correctly complete blending activities; for example, put together sounds /k/ /i/ /ck/ to make the word kick.

- He doesn't correctly complete phoneme substitution activities; for example, change the /m/ in mate to /cr/ in order to make crate.

- He has a hard time telling how many syllables there are in the word paper.

- He has difficulty with rhyming, syllabication, or spelling a new word by its sound.

How to help

With the help of parents and teachers, kids can learn strategies to cope with phonological and/or phonemic awareness problems that affect his or her reading. Below are some tips and specific things to do.

What kids can do to help themselves

- Be willing to play word and sounds games with parents or teachers.

- Be patient with learning new information related to words and sounds. Giving the ears a workout is difficult!

- Practice hearing the individual sounds in words. It may help to use a plastic chip as a counter for each sound you hear in a word.

- Be willing to practice writing. This will give you a chance to match sounds with letters.

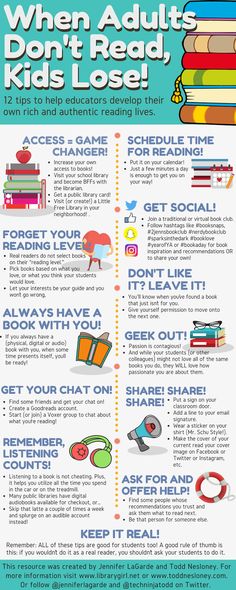

What parents can do to help at home

- Check with your child's teacher or principal to make sure the school's reading program teaches phonological, phonemic awareness, and phonics skills.

- If your child is past the ages at which phonemic awareness and phonological skills are taught class-wide (usually kindergarten to first or second grade), make sure he or she is receiving one-on-one or small group instruction in these skills.

- Do activities to help your child build sound skills (make sure they are short and fun; avoid allowing your child to get frustrated):

- Help your child think of a number of words that start with the /m/ or /ch/ sound, or other beginning sounds.

- Make up silly sentences with words that begin with the same sound, such as "Nobody was nice to Nancy's neighbor".

- Play simple rhyming or blending games with your child, such as taking turns coming up with words that rhyme (go – no) or blending simple words (/d/, /o/, /g/ = dog).

- Help your child think of a number of words that start with the /m/ or /ch/ sound, or other beginning sounds.

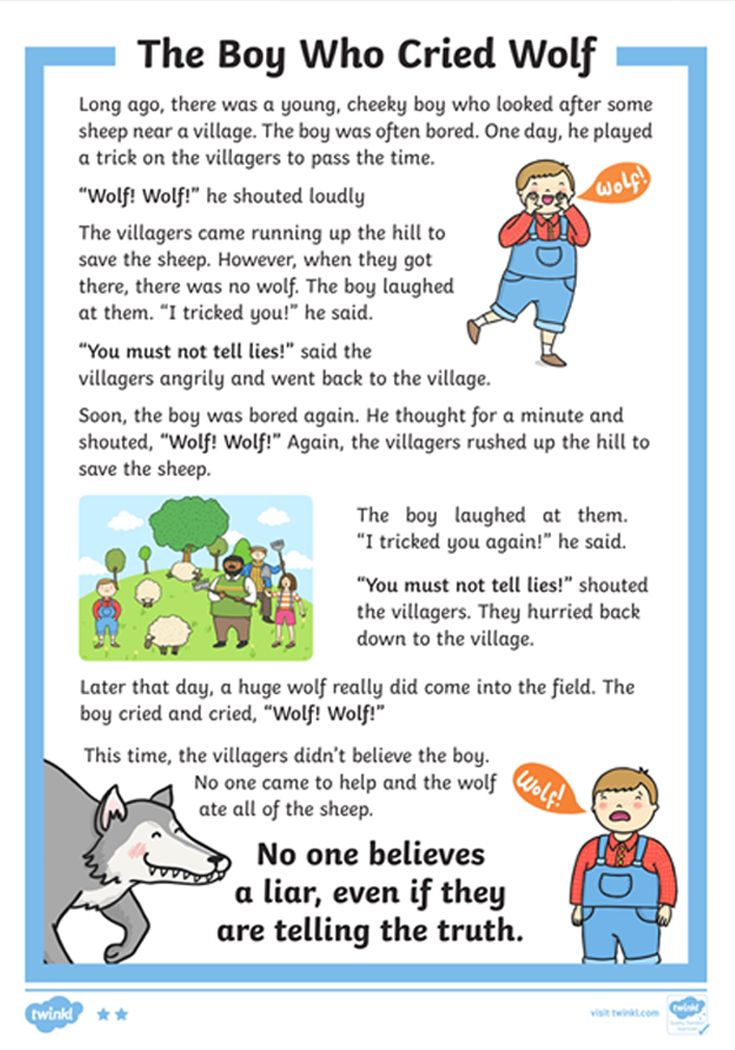

- Read books with rhymes. Teach your child rhymes, short poems, and songs.

- Practice the alphabet by pointing out letters wherever you see them and by reading alphabet books.

- Consider using computer software that focuses on developing phonological and phonemic awareness skills. Many of these programs use colorful graphics and animation that keep young children engaged and motivated.

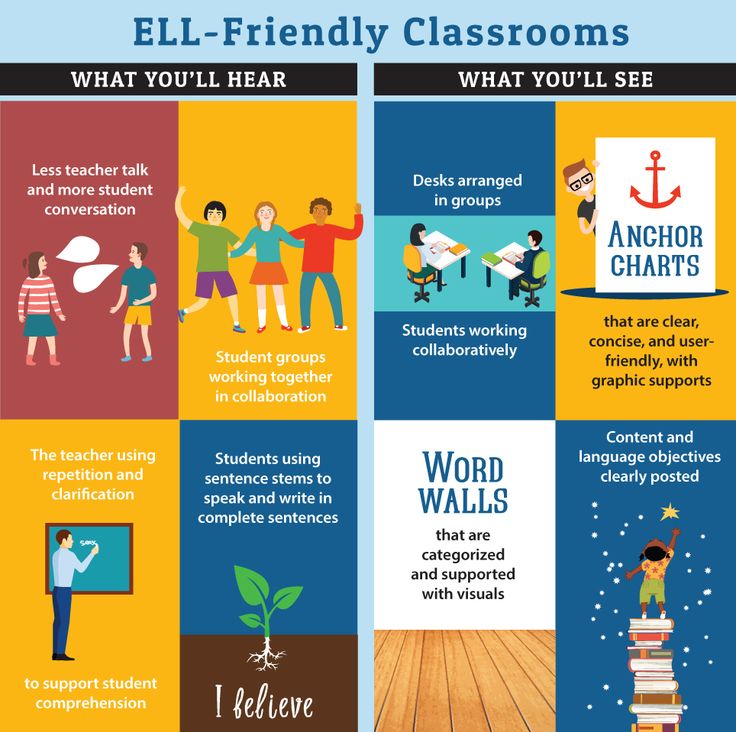

What teachers can do to help at school

- Learn all about phonemes (there are more than 40 speech sounds that may not be obvious to fluent readers and speakers).

- Make sure the school's reading program and other materials include skill-building in phonemes, especially in kindergarten and first grade (these skills do not come naturally, but must be taught).

- If children are past the age at which phonemic awareness and phonological skill-building are addressed (typically kindergarten through first or second grade), attend to these skills one-on-one or in a small group. Ask your school's reading specialist for help finding a research-based supplemental or intervention program for students in need.

- Identify the precise phoneme awareness task on which you wish to focus and select developmentally appropriate activities for engaging children in the task. Activities should be fun and exciting – play with sounds, don't drill them.

- Make sure your school's reading program and other materials include systematic instruction in phonics.

- Consider teaching phonological and phonemic skills in small groups since students will likely be at different levels of expertise. Remember that some students may need more reinforcement or instruction if they are past the grades at which phonics is addressed by a reading program (first through third grade).

More information

Additional resources

See the Reading Issues section on Understood.

next page >

15 Learning Disorder Terms Parents Need to Know

If your child has a speech, reading, or learning or attention disorder, you may have come across these terms on social media, forums, or at professional appointments. .

Terms such as phonological awareness, auditory processing disorder, auditory accuracy, phonological memory…

Understanding these 15 terms will help you better organize the help you need for your child:

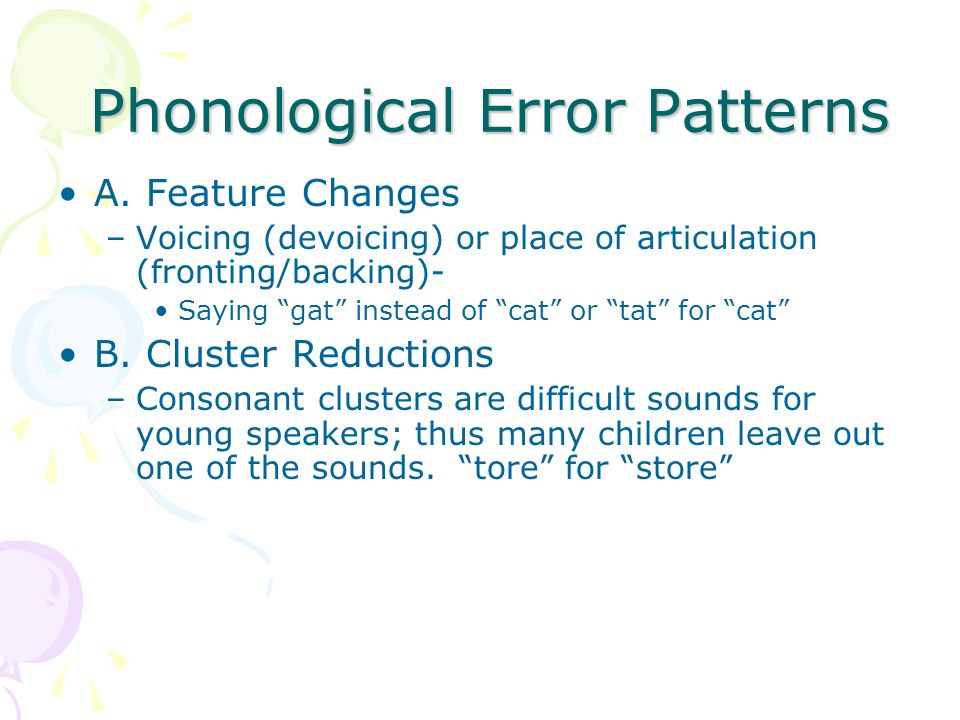

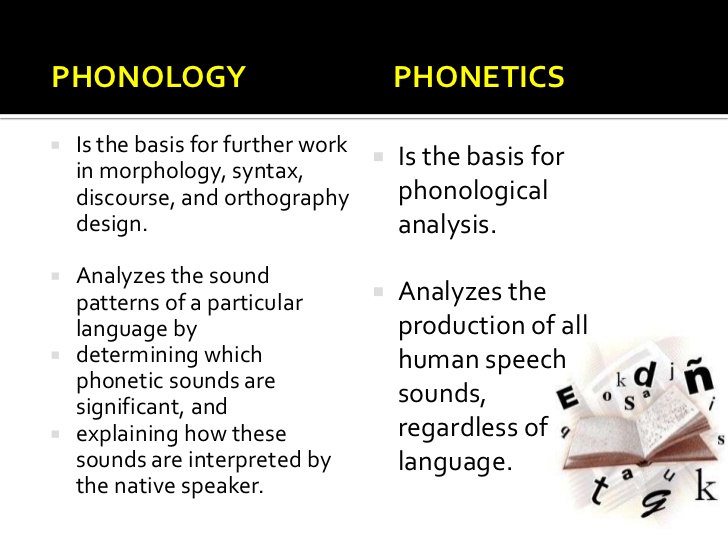

1. Phonetics

Phonetics - this term refers to the sound structure of the language: the relationship between a letter or a combination of letters (for example: chi, shu, cha, yes) and the speech sounds they represent.

Phonetics is the foundation of reading and writing skills. Thanks to phonetics, the child decodes written words in the process of reading.

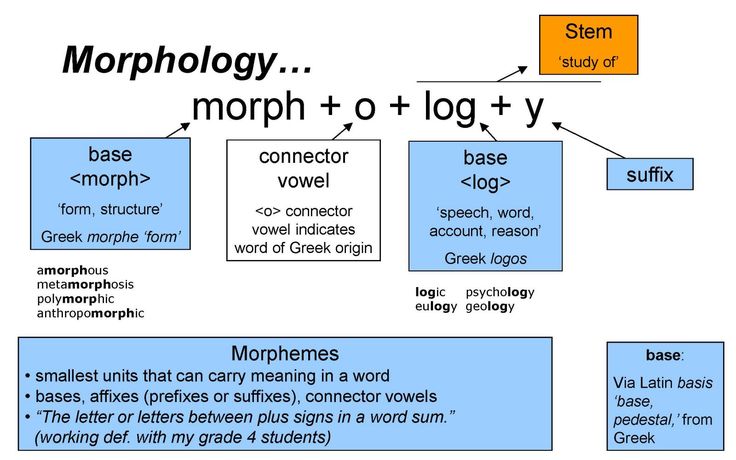

2. Phonemes

A phoneme is the sound of speech. When we speak Russian, we make 42 different speech sounds. But there are only 33 letters in the Russian alphabet. This is one of the reasons why Russian is difficult to learn.

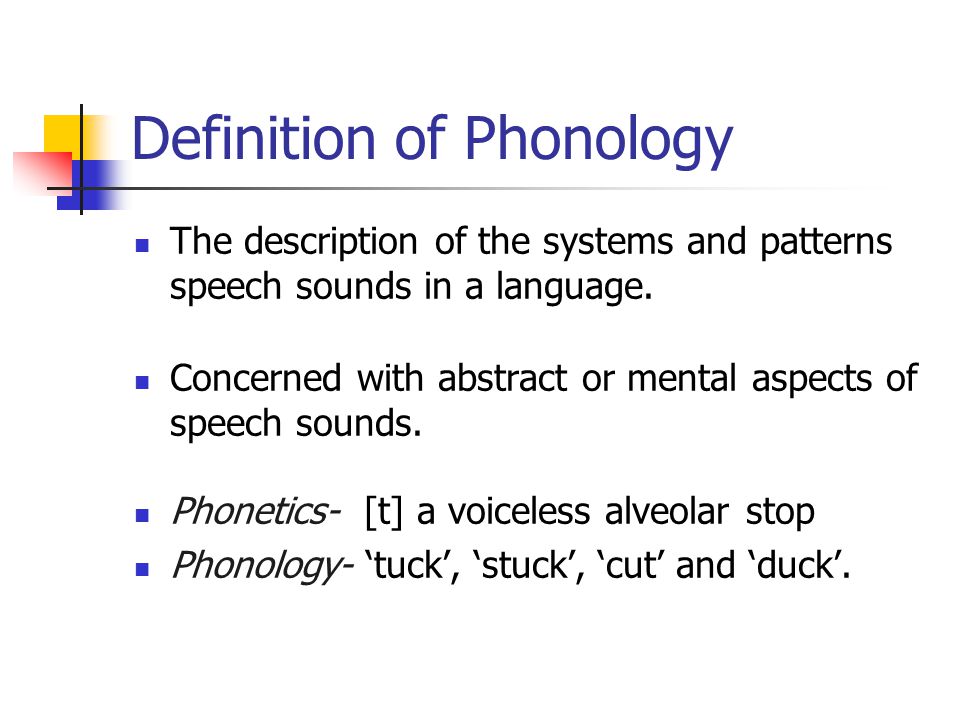

3. Phonemic perception

Phonemic perception is the ability to perceive individual speech sounds (phonemes) in words and work with them.

Learn how to develop phonemic awareness from an early age.

4. Phonological awareness

Phonological awareness is the awareness that words are made up of smaller parts (such as syllables and sounds).

The term includes a range of sound-related skills that a student needs to develop reading skills. As the child develops phonological awareness, he/she not only comes to understand that words are made up of small sound units (phonemes), but also learns that words can be broken down into larger sound "chunks" known as syllables. .

.

5. Phonological accuracy

Phonological accuracy refers to the ability to correctly distinguish between individual phonemes (e.g., in similar-sounding words that begin with the same sound) or other aspects of phonology (e.g., rhyming, number of syllables).

Phonological accuracy is key to listening and reading skills. This allows the student to make a clear distinction between similar-sounding words (e.g. "heron" and "saber" or "picture" and "basket"), including morphological differences that can drastically change the word's meaning and/or grammatical function (e.g. " known" and "unknown" or "inserted" and "exposed").

The ability to quickly and accurately identify speech sounds is critical to learning the rules of phonetics and matching spoken language to text correctly.

A child with well-developed phonological accuracy will more easily develop decoding skills, understand word and sentence structure, develop vocabulary, follow instructions, and participate more actively in class work.

Well developed phonological precision helps in:

-

Understanding and following verbal instructions

-

Listening skills

-

Development of reading skills

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

6. Phonological fluency

Phonological fluency is the understanding that words are made up of different sounds and the ability to quickly and accurately identify and manipulate these sounds.

Phonological fluency is critical to learning to read. This allows the student to memorize sequences of sounds and manipulate them quickly and accurately. This makes it easier to both write words and decode them. The more effectively the reader is able to decode, the more of his cognitive resources (mental abilities) he can focus on understanding the text.

A student with good phonological fluency will also find it easier to learn new words while reading. When confronted with a new word, a student who can accurately pronounce the word is more likely to recognize and understand its meaning.

When confronted with a new word, a student who can accurately pronounce the word is more likely to recognize and understand its meaning.

Well-developed phonological fluency helps in:

-

Learning the rules of phonetics

-

Development of reading skills

-

Development of writing skills

7. Phonological memory

Phonological memory is the ability to retain speech sounds in memory. This is essential for spoken language and tasks such as comparing phonemes and making connections between phonemes and letters. It also helps with listening and reading understanding of sentences, as it allows you to remember the sequence of words in order.

Phonological memory plays a key role in the development of oral and written language skills. This allows the student to:

-

Memorize and manipulate sound sequences

-

Associate spoken words with written ones

-

Memorize new words by determining their meanings

-

Remember the beginning of a sentence by listening to it to the end.

The ability to remember speech sounds is important for the correct understanding of sentences when changing the order of words in a sentence changes its meaning (for example, "The monkey bites the boy" and "The boy bites the monkey").

Accurate memory of word order also contributes to building accurate ideas about sentence structure and acquiring knowledge of syntax.

A student with a well-developed phonological memory develops phonemic perception and decoding skills more easily, knowledge of vocabulary and sentence structure is formed. Such a student follows instructions better and takes a more active part in class work with presentations, etc.

8. Auditory Processing / Auditory Perception

Auditory processing refers to what the brain does with the audio information it "hears". This includes various skills such as identifying and locating sounds, listening to background noise, and processing what is heard when the sound is fuzzy.

When a student manipulates the auditory information he has heard, but it doesn't sound right, this is called an auditory processing disorder (or auditory perception disorder).

This can happen if the child has difficulty understanding speech in background noise or has difficulty identifying where the sound is coming from. Or it could be a problem in distinguishing speech sounds that sound similar.

Find out 5 common hearing loss (HAI) myths!

9. Sequencing of audio information

Sequencing of audio information refers to the ability to identify and remember the order in which a series of sounds were presented. This is very important for matching sound sequences to letter sequences in decoding and writing.

Organizing audio information is critical to developing speaking and writing skills. The ability to identify and remember the order of sounds in words is important for recognizing subtle differences between words (such as "pot" and "top") and for developing phonemic perception and decoding skills.

A student who has a well-developed ordering of sound information understands and absorbs information better, develops better oral and written speech skills and concentrates attention. Such a student becomes an expert reader and a successful student.

See also: How do weak cognitive skills affect learning?

10. Listening word comprehension

Listening word comprehension refers to the ability to accurately identify words heard based on auditory cues alone, without the aid of visual or contextual cues.

Listening comprehension of words is critical to the development of spoken language and vocabulary, and therefore essential to the development of reading and writing. This skill allows the student to accurately and efficiently identify words in speech and helps him form a correct understanding of the information presented by ear.

A student with well developed listening comprehension will find it easier to follow instructions and participate in class discussions; it is easier to answer questions, complete tasks and remember information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader.

He will also find it easier to carry on a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

11. Hearing accuracy

Hearing accuracy is the ability to accurately identify differences between sounds and correctly identify sound sequences.

Accuracy in listening is the foundation of speech and reading skills. This skill allows the student to quickly and accurately identify and distinguish between rapidly changing sounds, which is very important for distinguishing between phonemes (the smallest units of speech that distinguish one word from another).

A student with well-developed listening comprehension will find it much easier to follow instructions and participate in class work; it is easier to remember questions, tasks and information; and it's much easier to become a proficient reader. He will also be able to:

-

Read and write fast

-

Focus on verbally presented information

-

Maintain a conversation in a noisy environment or when there are distractions.

12. Listening comprehension

Listening comprehension is the ability to understand consecutive sentences and extract meaning from what is heard.

Listening comprehension is one of the foundations of oral and written speech. To develop more complex speech skills, a child needs to develop good listening comprehension. Well developed listening comprehension allows the student to recognize the meanings formed by combinations of words and series of sentences.

A student with good listening comprehension will find it much easier to respond to assignments and class discussions; it will be easier to answer questions and remember information; and it is easier to become a proficient reader and a successful learner. He will also be able to do well:

-

Focus on oral information

-

Making sense of history

-

Correctly follow verbal instructions

-

Correctly understand and answer questions

Reading disorders in children - Logoprofy.

ru

ru Reading is a fundamental skill for learning and success in life. Unfortunately, children with early speech disorders tend to have additional difficulties when they begin to learn written language. It is important for speech therapists to pay attention to reading when working with children with early language disorders.

Read more about reading disorders and dyslexia here!

Prevention of reading difficulties in children with speech disorders.

1. It has been assumed for some time that children with language impairments are at increased risk of reading difficulties. This is true?

Yes, there is consistent evidence that children with language disorders, such as children with language developmental disabilities, than normally developing children. More than 50% of children with language developmental disorders have poor reading skills in primary grades.

2. Children with speech disorders have problems developing literacy in preschools. Do the problems go away with time?

Do the problems go away with time?

Unfortunately, the opposite can also be true. The study examined the developmental trajectory of reading in children with speech impairments compared to typically developing peers. In kindergarten, children with disabilities had a significantly lower reading speed. However, over time, the gap between the two groups widened. Such work has led to great interest in determining how reading impairments can be prevented among children with disabilities, perhaps by improving children's early literacy skills before formal school entry and the rigor of kindergarten reading instruction.

3. What is the difference between reading difficulties and reading disorders?

I use the term "reading difficulties" to refer to children who do not read at the level they should, given age, school year, background, and so on. Data obtained from the National Assessment of Educational Progress shows that approximately 36% of fourth graders are savvy readers; conversely, 64% do not. Children who are not experienced readers may have difficulty reading. Many of these children are inexperienced due to the influence of poverty and upbringing, and may attend schools with limited attention to reading or with chronic problems. By comparison, I use the term "reading disability" to describe children who have unexplained problems with reading development, such as dyslexia.

Children who are not experienced readers may have difficulty reading. Many of these children are inexperienced due to the influence of poverty and upbringing, and may attend schools with limited attention to reading or with chronic problems. By comparison, I use the term "reading disability" to describe children who have unexplained problems with reading development, such as dyslexia.

4. Why are speech therapists concerned about reading difficulties?

Reading difficulties are the biggest “problem” faced by children with speech disorders. If someone cannot read, they are unlikely to succeed in education and in other areas of life (social relations, secondary education, etc.)

5. Why is it so important to continuously develop reading?

The development of reading is extremely difficult. It is considered a multi-component skill that is difficult to develop. The growth of reading is influenced by numerous aspects of the environment, as well as the basic cognitive and affective capabilities of a person. Unfortunately, progress in reading is easy to stall; For example, very poor quality elementary school attendance can have serious consequences for student achievement. At the same time, the presence of cognitive problems that affect the skills and processes that reading relies on, such as the visual, linguistic, and auditory systems, can also compromise development.

Unfortunately, progress in reading is easy to stall; For example, very poor quality elementary school attendance can have serious consequences for student achievement. At the same time, the presence of cognitive problems that affect the skills and processes that reading relies on, such as the visual, linguistic, and auditory systems, can also compromise development.

6. Is it true that children can't read because their parents don't care about reading or don't read regularly to their children?

There are parents who, for many reasons, do not understand the development of early literacy enough to give their children an important early reading experience. However, when children have trouble reading, it's not because "something" happened or didn't happen in their lives. Typically, reading difficulties reflect a conglomeration of problems that rise to the threshold in order to bypass the development of a child's reading. For example, it may happen that a child is born with significant intellectual disabilities, which motivates him to read very little. In turn, parents (and teachers, and others) read less to these children and develop low expectations for the future child as a reader. As mentioned earlier, the development and complexity of reading is an extremely complex phenomenon.

In turn, parents (and teachers, and others) read less to these children and develop low expectations for the future child as a reader. As mentioned earlier, the development and complexity of reading is an extremely complex phenomenon.

7. Is there a prevailing theory or conceptual framework that can be used to understand more about reading?

I like the "simple view of reading" as a theoretical basis for conceptualizing reading. She argues that reading (R) is the production of decoding (D) and linguistic understanding (L), or C = D x L. Simply put, decoding is the ability to apply the alphabetical principle to decode words, while linguistic comprehensiveness is more or less, their language skills. Therefore, we can conceptualize a child with reading difficulties as problems with deciphering and/or linguistic comprehension that can compromise reading ability.

8. What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a special group of readers with an impairment who have an adequate level of linguistic understanding but very poor decoding skills. Thus, people with dyslexia can understand complex texts they hear but cannot decode them. There is a mismatch between their linguistic skills and their decoding skills. A subset of children with language disorders have decoding problems and can be described as dyslexic.

Thus, people with dyslexia can understand complex texts they hear but cannot decode them. There is a mismatch between their linguistic skills and their decoding skills. A subset of children with language disorders have decoding problems and can be described as dyslexic.

9. There is a theory that dyslexia is caused by problems with phonology. If this is true, can't we solve the problem of phonology in order to solve reading problems?

I wish it were true. There is a strong relationship between dyslexia (reading problems related to transcription) and phonological skills such as phonological processing. Providing these children with treatment that addresses underlying phonological problems can improve their reading skills. However, since the skill of reading is difficult, it is usually not a "magic bullet". Often children with dyslexia are not identified early enough to resolve their phonological problems and they may lose valuable learning time in reading development and fall quite far behind. In addition, they may have motivational problems due to the inability to read class-level texts. It is important not to be deceived into thinking that there is one program or approach that can easily eliminate dyslexia. This is often a lifelong issue that requires constant, close attention.

In addition, they may have motivational problems due to the inability to read class-level texts. It is important not to be deceived into thinking that there is one program or approach that can easily eliminate dyslexia. This is often a lifelong issue that requires constant, close attention.

10. Some children have good decoding skills (i.e. they are not dyslexic), but they do not seem to understand what they are reading. What's up with that?

These children are commonly referred to as "poor comprehensions" - these children have good decoding (and phonological processing) skills but do not understand what they are reading. These children tend to have poor basic language skills, including problems with grammar and vocabulary that compromise their ability to understand what they read. Often, these children develop "subclinical language problems": language problems that are not severe enough to justify professional intervention by a speech therapist. Thus, it seems that "bad understanders" are in serious danger of falling through the cracks.

1 1. How can we prevent children from reading problems?

The key to preventing reading difficulties in young children is to address the problems that cause reading problems early in a child's life. For many children, reading development formally begins in kindergarten or first grade, when they are taught to read by their elementary school teachers. However, there are preliminary skills upon which this reading development and learning to read will be based. If we - parents, teachers, speech language pathologists - help children come to read development with these preliminary skills, they are much more likely to respond and begin to develop by starting to read.

12. What are some of the preliminary skills?

The most talked about preschool skills, often referred to as early literacy skills, include vocabulary, grammar, storytelling, phonological awareness and print proficiency. The first three are the usual language areas most likely to be familiar to speech therapists. These skills are important precursors to linguistic understanding. The last two, phonological awareness and print awareness, are important precursors to decoding. Phonological awareness represents young children's growing sensitivity to sound structures in spoken language, while print proficiency represents young children's growing knowledge of the forms and functions of print. All of these preliminary skills have a strong, longitudinal relationship with future reading achievement.

These skills are important precursors to linguistic understanding. The last two, phonological awareness and print awareness, are important precursors to decoding. Phonological awareness represents young children's growing sensitivity to sound structures in spoken language, while print proficiency represents young children's growing knowledge of the forms and functions of print. All of these preliminary skills have a strong, longitudinal relationship with future reading achievement.

13. Isn't reading problems the responsibility of a reading teacher?

Firstly, there is no "reading teacher" in the elementary grades. Children have a general teacher who is responsible for all areas of learning, including reading. Secondly, teachers working as elementary school students receive reading training, usually several courses on the basics of reading development and methods of teaching reading. However, they are likely to lack the skills to conduct the specialized assessments and interventions needed to determine how to deal with a given child's problems. When children experience reading difficulties, providing a sufficient level of response to correct these problems is often far more than a primary school teacher can undertake. For this reason, schools often have numerous professionals who can intervene and provide additional support, including school psychologists, special education teachers, and speech therapists. Therefore, reading problems are not the responsibility of the reading teacher. Reading difficulties are a major concern for many, and we need to be "all hands on deck" so to speak, to identify and address these issues when they arise.

When children experience reading difficulties, providing a sufficient level of response to correct these problems is often far more than a primary school teacher can undertake. For this reason, schools often have numerous professionals who can intervene and provide additional support, including school psychologists, special education teachers, and speech therapists. Therefore, reading problems are not the responsibility of the reading teacher. Reading difficulties are a major concern for many, and we need to be "all hands on deck" so to speak, to identify and address these issues when they arise.

14. Why are children with language disorders susceptible to reading problems?

Much work has been done on this subject, and the general evidence suggests that the same underlying problems that contribute to the diagnosis of a language disorder are also associated with reading difficulties. This is because reading, at least part of reading linguistic understanding, is language. However, that's not all. There is some evidence to suggest that children with language disorders may be less motivated to participate in literacy activities, resulting in reduced experience in the types of experiences that can increase reading. It is also true that language problems tend to run in families, so children with language disorders may have parents who themselves have language problems and related reading problems. In turn, such parents may provide a less secure home literacy environment for their children. Finally, it is also possible that teachers and psychotherapists may lower their expectations of reading achievement for children with language impairments. If this happened, they could provide fewer opportunities for learning, further hindering the growth of their reading.

However, that's not all. There is some evidence to suggest that children with language disorders may be less motivated to participate in literacy activities, resulting in reduced experience in the types of experiences that can increase reading. It is also true that language problems tend to run in families, so children with language disorders may have parents who themselves have language problems and related reading problems. In turn, such parents may provide a less secure home literacy environment for their children. Finally, it is also possible that teachers and psychotherapists may lower their expectations of reading achievement for children with language impairments. If this happened, they could provide fewer opportunities for learning, further hindering the growth of their reading.

15. Are there effective measures to improve the literacy skills of children with language impairments?

Yes! In the last decade, this issue has received considerable attention in the scientific literature. The researchers tested ways to increase phonological awareness among children with language disorders, as well as knowledge of written language. Perhaps the biggest limitation of such work, however, is that there is little long-term evidence to suggest that early literacy interventions for children with language disabilities have long-term benefits for reading success. However, one recent study found that children with language disorders who received a preschool literacy intervention maintained their early literacy gains up to one year after the intervention.

The researchers tested ways to increase phonological awareness among children with language disorders, as well as knowledge of written language. Perhaps the biggest limitation of such work, however, is that there is little long-term evidence to suggest that early literacy interventions for children with language disabilities have long-term benefits for reading success. However, one recent study found that children with language disorders who received a preschool literacy intervention maintained their early literacy gains up to one year after the intervention.

16. When parents read to their children, it can improve their reading performance. This is true?

There is evidence that home reading between parents and their children can influence their children's early reading development. However, it is definitely not a "magic bullet". At best, regular reading at home modestly improves early reading skills in children, and allowing parents to read to their children daily will not be enough to address significant reading difficulties.