Importance of fluency

Fluency: Instructional Guidelines and Student Activities

Guidelines for instruction

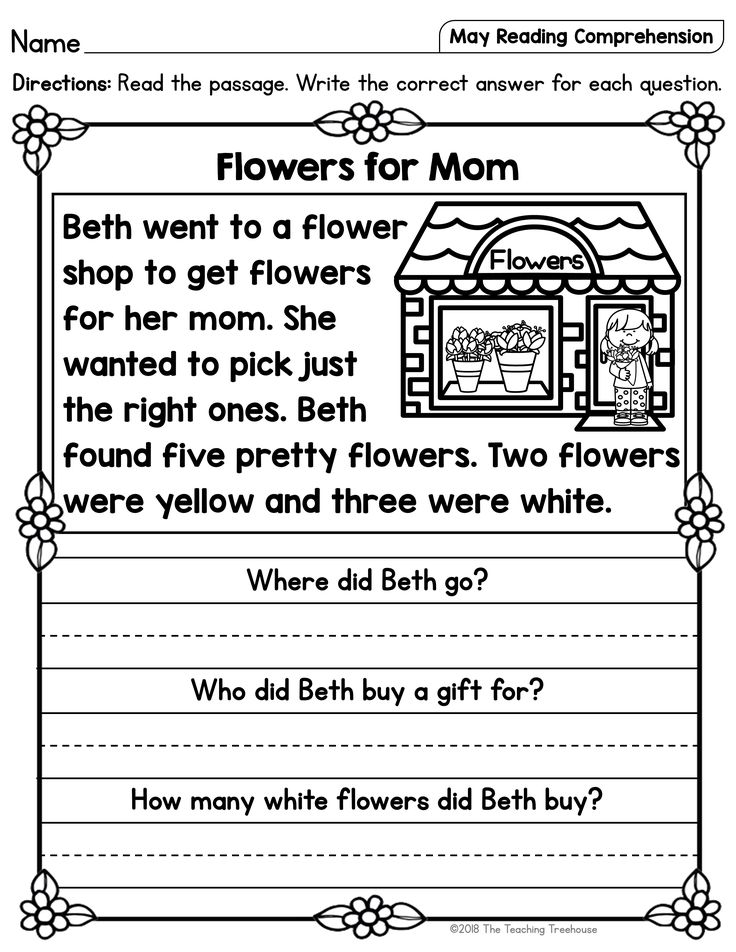

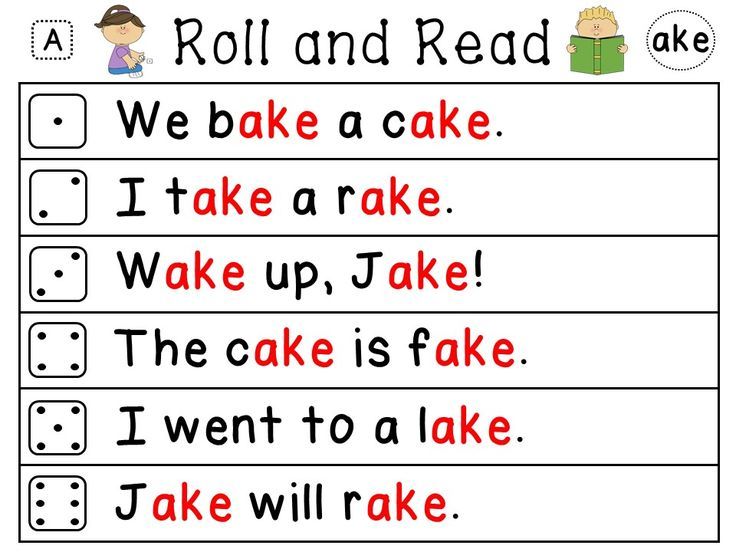

- Provide children with opportunities to read and reread a range of stories and informational texts by reading on their own, partner reading, or choral reading.

- Introduce new or difficult words to children, and provide practice reading these words before they read on their own.

- Include opportunities for children to hear a range of texts read fluently and with expression.

- Suggest ideas for building home-school connections that encourage families to become involved actively in children's reading development.

- Encourage periodic timing of children's oral reading and recording of information about individual children's reading rate and accuracy.

- Model fluent reading, then have students reread the text on their own.

What students should read

Fluency develops as a result of many opportunities to practice reading with a high degree of success. Therefore, your students should practice rereading aloud texts that are reasonably easy for them that is, texts containing mostly words that they know or can decode easily. In other words, the texts should be at the students' independent reading level.

A text is at students' independent reading level if they can read it with about 95% accuracy. If the text is more difficult, students will focus on word recognition and will not have an opportunity to develop fluency.

The text your students practice rereading orally should also be relatively short probably 50-200 words, depending on the age of the students. You should also use a variety of reading materials, including stories, nonfiction, and poetry. Poetry is especially well suited to fluency practice because poems for children are often short and they contain rhythm, rhyme, and meaning, making practice easy, fun, and rewarding.

Model fluent reading

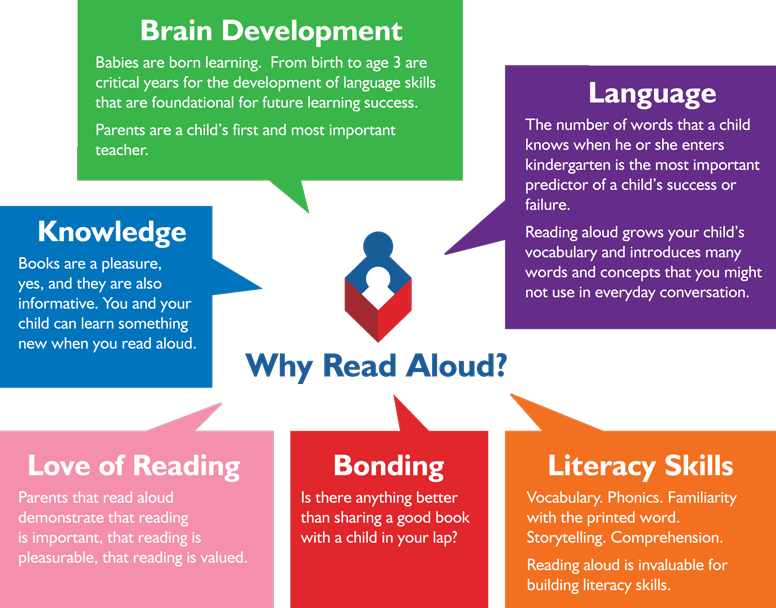

By listening to good models of fluent reading, students learn how a reader's voice can help written text make sense. Read aloud daily to your students. By reading effortlessly and with expression, you are modeling for your students how a fluent reader sounds during reading.

Read aloud daily to your students. By reading effortlessly and with expression, you are modeling for your students how a fluent reader sounds during reading.

Repeated reading

After you model how to read the text, you must have the students reread it. By doing this, the students are engaging in repeated reading. Usually, having students read a text four times is sufficient to improve fluency. Remember, however, that instructional time is limited, and it is the actual time that students are actively engaged in reading that produces reading gains.

Have other adults read aloud to students. Encourage parents or other family members to read aloud to their children at home. The more models of fluent reading the children hear, the better. Of course, hearing a model of fluent reading is not the only benefit of reading aloud to children. Reading to children also increases their knowledge of the world, their vocabulary, their familiarity with written language ("book language"), and their interest in reading.

Activities for students to increase fluency

There are several ways that your students can practice orally rereading text, including student-adult reading, choral (or unison) reading, tape-assisted reading, partner reading, and readers' theatre.

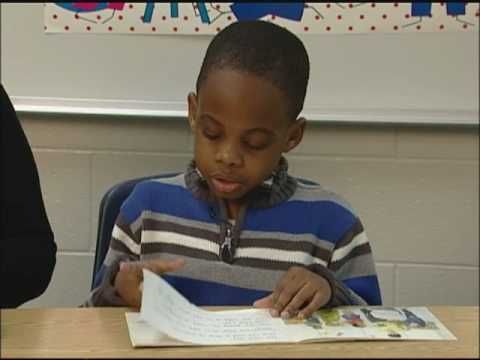

Student-adult reading

In student-adult reading, the student reads one-on-one with an adult. The adult can be you, a parent, a classroom aide, or a tutor. The adult reads the text first, providing the students with a model of fluent reading. Then the student reads the same passage to the adult with the adult providing assistance and encouragement. The student rereads the passage until the reading is quite fluent. This should take approximately three to four rereadings.

Choral reading

In choral, or unison, reading, students read along as a group with you (or another fluent adult reader). Of course, to do so, students must be able to see the same text that you are reading. They might follow along as you read from a big book, or they might read from their own copy of the book you are reading. For choral reading, choose a book that is not too long and that you think is at the independent reading level of most students. Patterned or predictable books are particularly useful for choral reading, because their repetitious style invites students to join in. Begin by reading the book aloud as you model fluent reading.

For choral reading, choose a book that is not too long and that you think is at the independent reading level of most students. Patterned or predictable books are particularly useful for choral reading, because their repetitious style invites students to join in. Begin by reading the book aloud as you model fluent reading.

Then reread the book and invite students to join in as they recognize the words you are reading. Continue rereading the book, encouraging students to read along as they are able. Students should read the book with you three to five times total (though not necessarily on the same day). At this time, students should be able to read the text independently.

Tape-assisted reading

In tape-assisted reading, students read along in their books as they hear a fluent reader read the book on an audiotape. For tape-assisted reading, you need a book at a student's independent reading level and a tape recording of the book read by a fluent reader at about 80-100 words per minute. The tape should not have sound effects or music. For the first reading, the student should follow along with the tape, pointing to each word in her or his book as the reader reads it. Next, the student should try to read aloud along with the tape. Reading along with the tape should continue until the student is able to read the book independently, without the support of the tape.

The tape should not have sound effects or music. For the first reading, the student should follow along with the tape, pointing to each word in her or his book as the reader reads it. Next, the student should try to read aloud along with the tape. Reading along with the tape should continue until the student is able to read the book independently, without the support of the tape.

Partner reading

In partner reading, paired students take turns reading aloud to each other. For partner reading, more fluent readers can be paired with less fluent readers. The stronger reader reads a paragraph or page first, providing a model of fluent reading. Then the less fluent reader reads the same text aloud. The stronger student gives help with word recognition and provides feedback and encouragement to the less fluent partner. The less fluent partner rereads the passage until he or she can read it independently. Partner reading need not be done with a more and less fluent reader. In another form of partner reading, children who read at the same level are paired to reread a story that they have received instruction on during a teacher-guided part of the lesson. Two readers of equal ability can practice rereading after hearing the teacher read the passage.

Two readers of equal ability can practice rereading after hearing the teacher read the passage.

Readers' theatre

In readers' theatre, students rehearse and perform a play for peers or others. They read from scripts that have been derived from books that are rich in dialogue. Students play characters who speak lines or a narrator who shares necessary background information. Readers' theatre provides readers with a legitimate reason to reread text and to practice fluency. Readers' theatre also promotes cooperative interaction with peers and makes the reading task appealing.

Fluency Norms Chart (2017 Update)

In 2006, Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal completed an extensive study of oral reading fluency. The results of their study were published in a technical report entitledOral Reading Fluency: 90 Years of Measurement, archived in The Reading Teacher: Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers.

In 2017, Hasbrouck and Tindal published an Update of Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) Norms, compiled from three widely-used and commercially available ORF assessments (DIBELS, DIBELS Next, and easy CBM), and representing a far larger number of scores than the previous assessments.

The table below shows the mean oral reading fluency of students in grades 1 through 6, as determined by Hasbrouck's and Tindal's 2017 data. You can also see an analysis of how the 2017 norms differ from the 2006 norms.

Oral reading fluency (ORF)

Of the various CBM measures available in reading, ORF is likely the most widely used. ORF involves having students read aloud from an unpracticed passage for one minute. An examiner notes any errors made (words read or pronounced incorrectly, omitted, read out of order, or words pronounced for the student by the examiner after a 3-second pause) and then calculates the total of words read correctly per minute (WCPM).

This WCPM score has 30 years of validation research conducted over three decades, indicating it is a robust indicator of overall reading development throughout the primary grades.

Interpreting ORF scores

ORF is used for two primary purposes: Screening and progress monitoring. When ORF is used to screen students, the driving questions are, first: “How does this student’s performance compare to his/her peers?” and then: “Is this student at-risk of reading failure?”

To answer these questions, the decision-makers rely on ORF norms that identify performance benchmarks at the beginning (fall), middle (winter), and end (spring) of the year. An individual student’s WCPM score can be compared to these benchmarks and determined to be either significantly above benchmark, above benchmark, at the expected benchmark, below benchmark, or significantly below benchmark.

An individual student’s WCPM score can be compared to these benchmarks and determined to be either significantly above benchmark, above benchmark, at the expected benchmark, below benchmark, or significantly below benchmark.

Those students below or significantly below benchmark are at possible risk of reading difficulties. They are good candidates for further diagnostic assessments to help teachers determine their skill strengths or weaknesses, and plan appropriately targeted instruction and intervention (Hasbrouck, 2010. Educators as Physicians: Using RTI Data for Effective Decision-Making. Austin, TX: Gibson Hasbrouck & Associates.

When using ORF for progress monitoring the questions to be answered are: “Is this student making expected progress?” and “Is the instruction or intervention being provided improving this student’s skills?”

When ORF assessments are used to answer these questions, they must be administered frequently (weekly, bimonthly, etc.), the results are placed on a graph for ease of analysis, and a goal determined. The student’s goal can be based on established performance benchmarks or information on expected rates of progress. Over a period of weeks, the student’s graph can show significant or moderate progress, expected progress, or progress that is below or significantly below expected levels.

The student’s goal can be based on established performance benchmarks or information on expected rates of progress. Over a period of weeks, the student’s graph can show significant or moderate progress, expected progress, or progress that is below or significantly below expected levels.

Based on these outcomes, teachers can decide whether to (a) make small or major changes to the student’s instruction, (b) continue with the current instructional plan, or (c) change the student’s goal (Hosp, Hosp, & Howell, 2007. The ABCs of CBM: A Practical Guide to Curriculum-based Measurement. NY: Guilford Press).

Using the data

You can use the information in this table to draw conclusions and make decisions about the oral reading fluency of your students.

Students scoring 10 or more words below the 50th percentile using the average score of two unpracticed readings from grade-level materials need a fluency-building program.

In addition, teachers can use the table to set the long-term fluency goals for their struggling readers.

2017 Oral reading fluency (ORF) data

| Grade | %ile | Fall WCPM* | Winter WCPM* | Spring WCPM* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 97 | 116 | |

| 75 | 59 | 91 | ||

| 50 | 29 | 60 | ||

| 25 | 16 | 34 | ||

| 10 | 9 | 18 | ||

| 2 | 90 | 111 | 131 | 148 |

| 75 | 84 | 109 | 124 | |

| 50 | 50 | 84 | 100 | |

| 25 | 36 | 59 | 72 | |

| 10 | 23 | 35 | 43 | |

| 3 | 90 | 134 | 161 | 166 |

| 75 | 104 | 137 | 139 | |

| 50 | 83 | 97 | 112 | |

| 25 | 59 | 79 | 91 | |

| 10 | 40 | 62 | 63 | |

| 4 | 90 | 153 | 168 | 184 |

| 75 | 125 | 143 | 160 | |

| 50 | 94 | 120 | 133 | |

| 25 | 75 | 95 | 105 | |

| 10 | 60 | 71 | 83 | |

| 5 | 90 | 179 | 183 | 195 |

| 75 | 153 | 160 | 169 | |

| 50 | 121 | 133 | 146 | |

| 25 | 87 | 109 | 119 | |

| 10 | 64 | 84 | 102 | |

| 6 | 90 | 185 | 195 | 204 |

| 75 | 159 | 166 | 173 | |

| 50 | 132 | 145 | 146 | |

| 25 | 112 | 116 | 122 | |

| 10 | 89 | 91 | 91 |

* WCPM = Words Correct Per Minute

The 2017 chart is available as a PDF: 2017 Hasbrouck & Tindal Oral Reading Norms

Comparison of ORF norms for 2006 and 2017

| %iles | Grade 1 | F | W | S | Grade 2 | F | W | S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 2017 | 97 | 116 | 2017 | 111 | 131 | 148 | |||

| 90 | 2006 | 81 | 111 | 2006 | 106 | 125 | 142 | |||

| Difference | 16 | 5 | Difference | 5 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| 75 | 2017 | 59 | 91 | 2017 | 84 | 109 | 124 | |||

| 75 | 2006 | 47 | 82 | 2006 | 79 | 100 | 117 | |||

| Difference | 12 | 9 | Difference | 5 | 9 | 7 | ||||

| 50 | 2017 | 29 | 60 | 2017 | 50 | 84 | 100 | |||

| 50 | 2006 | 23 | 53 | 2006 | 51 | 72 | 89 | |||

| Difference | 6 | 7 | Difference | -1 | 12 | 11 | ||||

| 25 | 2017 | 16 | 34 | 2017 | 36 | 59 | 72 | |||

| 25 | 2006 | 12 | 28 | 2006 | 25 | 42 | 61 | |||

| Difference | 4 | 6 | Difference | 11 | 17 | 11 | ||||

| 10 | 2017 | 9 | 18 | 2017 | 23 | 35 | 43 | |||

| 10 | 2006 | 6 | 15 | 2006 | 11 | 18 | 31 | |||

| Difference | 3 | 3 | Difference | 12 | 17 | 12 |

| %iles | Grade3 | F | W | S | Grade 4 | F | W | S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 2017 | 134 | 161 | 166 | 2017 | 153 | 168 | 184 | ||

| 90 | 2006 | 128 | 145 | 162 | 2006 | 145 | 166 | 180 | ||

| Difference | 6 | 15 | 4 | Difference | 8 | 2 | 4 | |||

| 75 | 2017 | 104 | 137 | 139 | 2017 | 125 | 143 | 160 | ||

| 75 | 2006 | 99 | 120 | 137 | 2006 | 119 | 139 | 152 | ||

| Difference | 5 | 17 | 2 | Difference | 6 | 4 | 8 | |||

| 50 | 2017 | 83 | 97 | 112 | 2017 | 94 | 120 | 133 | ||

| 50 | 2006 | 71 | 92 | 107 | 2006 | 94 | 112 | 123 | ||

| Difference | 12 | 5 | 5 | Difference | 0 | 8 | 10 | |||

| 25 | 2017 | 59 | 79 | 91 | 2017 | 75 | 95 | 105 | ||

| 25 | 2006 | 44 | 62 | 78 | 2006 | 68 | 87 | 98 | ||

| Difference | 15 | 17 | 13 | Difference | 7 | 8 | 7 | |||

| 10 | 2017 | 40 | 62 | 63 | 2017 | 60 | 71 | 83 | ||

| 10 | 2006 | 21 | 36 | 48 | 2006 | 45 | 61 | 72 | ||

| Difference | 19 | 26 | 15 | Difference | 15 | 10 | 11 |

| %iles | Grade 5 | F | W | S | Grade 6 | F | W | S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 2017 | 179 | 183 | 195 | 2017 | 185 | 195 | 204 | ||

| 90 | 2006 | 166 | 183 | 194 | 2006 | 177 | 195 | 204 | ||

| Difference | 13 | 1 | 1 | Difference | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 75 | 2017 | 153 | 160 | 169 | 2017 | 159 | 166 | 173 | ||

| 75 | 2006 | 139 | 156 | 168 | 2006 | 153 | 167 | 177 | ||

| Difference | 14 | 4 | 1 | Difference | 6 | -1 | -4 | |||

| 50 | 2017 | 121 | 133 | 146 | 2017 | 132 | 145 | 146 | ||

| 50 | 2006 | 110 | 127 | 139 | 2006 | 127 | 145 | 150 | ||

| Difference | 11 | 6 | 7 | Difference | 5 | 5 | -4 | |||

| 25 | 2017 | 87 | 109 | 119 | 2017 | 112 | 116 | 122 | ||

| 25 | 2006 | 85 | 99 | 109 | 2006 | 98 | 111 | 122 | ||

| Difference | 2 | 10 | 10 | Difference | 14 | 5 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 2017 | 64 | 84 | 102 | 2017 | 89 | 91 | 91 | ||

| 10 | 2006 | 61 | 74 | 83 | 2006 | 68 | 82 | 93 | ||

| Difference | 3 | 10 | 19 | Difference | 21 | 9 | -2 |

Average differences in ORF for each grade level

| Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Fall | Winter | Spring | Average * |

| 1 | 41 | 30 | 7 | |

| 2 | 32 | 61 | 47 | 9 |

| 3 | 57 | 80 | 39 | 12 |

| 4 | 28 | 30 | 36 | 6 |

| 5 | 43 | 30 | 38 | 8 |

| 6 | 54 | 18 | -10 | 4 |

* Average across all percentile range values.

Fluency - Musical Corpuscle

Fluency - i.e. the ability to sing in fast motion - is also a necessary quality of a professional singing voice. Singing in rapid motion - coloratura technique - is necessary for the performance of a large number of vocal works. At all times and eras, composers have used this type of technique to convey mainly the emotions of fun, joy, cheerfulness. In the bel canto era in the second half of the 17th and 18th centuries, works were built almost exclusively on coloratura, which was obligatory for all types of voices. In the 19th century after Rossini, coloratura in its purest form was used in Western music mainly in parts of high female voices. However, even later, individual elements of coloratura are found in many works.

Possession of this type of technique is mandatory for all professional voices, since each singer must be able to sing works of various eras and national schools. However, only for coloratura sopranos this type of technique is the main one in singing. It was for this type of voice that coloratura works were written in the 19th century. And until now, the coloratura remains the property, first of all, of high female voices.

It was for this type of voice that coloratura works were written in the 19th century. And until now, the coloratura remains the property, first of all, of high female voices.

Russian vocal art did not survive the era of coloratura like Italian. The coloratura found in Russian classical operas has a different character than the Italian coloratura. Coloratura in Italian operas, even by Verdi, not to mention Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and earlier authors, is somewhat formal and abstract. It is not directly related to the musical characteristics of this or that character.

We can easily imagine Rosina using the coloratura of the Figaro part, and Figaro using the coloratura of Rosina or Almaviva. Even in Verdi, coloratura, which remain mainly in high female voices, are not as closely connected with the characterization of the image as in Russian operas. Antonida's coloratura from Glinka's "Ivan Susanin" is unique to her. Ludmila's coloratura from "Ruslan and Lyudmila" creates the image of a cheerful, young, cheerful Russian girl and also cannot be transferred to another character. Rimsky-Korsakov's coloratura is highly characteristic, with which, for example, he endows Volkhova. Decorations and fast movements in the parts of the Snow Maiden and the Swan Princess are characteristic, creating a musical image of these characters.

Rimsky-Korsakov's coloratura is highly characteristic, with which, for example, he endows Volkhova. Decorations and fast movements in the parts of the Snow Maiden and the Swan Princess are characteristic, creating a musical image of these characters.

Therefore, Russian coloratura singers must master coloratura to an even greater extent than Italian singers. The performing tasks that they face are deeper and more complex than those of Italian singers. A Russian singer who performs roles written for a coloratura or lyric-coloratura soprano must possess not only a perfect, formal coloratura, but also be able to reveal the essence of the image through coloratura. The best representatives of Russian vocal art, such as Zabela-Vrubel, Nezhdanova, Stepanova, were able to do this in the highest degree convincingly.

The huge romance repertoire also contains many works that require fluency from all voices. The singer must be able to sing in rapid motion all the basic elements that make up a melody: scale sequences, arpeggios, passages, up and down intervals, grace notes, groupettos, mordents, trills.

Every singer can develop fluency, but for some, mastering the technique of fluency is a very simple task, while for others it is very difficult. There are voices "mobile by nature", for them the technique of fluency is very easy. Moreover, this quality is not necessarily related to the nature of the voice. It happens that a large, heavy, low voice, for example, a bass, easily lends itself to the development of fluency technique, and another - a light tenor - coloratura is given with great difficulty. The quality of voice mobility is undoubtedly a special ability and is associated with the activity of the central nervous system. It should be associated with the mobility of the nervous processes that characterize a given individual.

Mobility can be greatly improved in any individual under the influence of systematic training. But the advantages, of course, will remain with those who have natural mobility, which is improved many times over under the influence of training.

If for coloratura and lyric-coloratura voices virtuosity in the technique of fluency is mandatory, which determines their professional capabilities, then for other types of voices it is also necessary, although usually it does not reach such great perfection. Both the bass, the baritone and the tenor, as well as the mezzo-soprano and the dramatic soprano, always contain numerous works in the repertoire that require mastery of the technique of fluency. Let us recall, for example, Farlaf's rondo from Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila or Don Basilio's aria from Rossini's The Barber of Seville, at the bass; the arias of Figaro from the same opera and the aria of Don Giovanni from Mozart's baritone opera, the part of Almaviva from The Barber of Seville, Rossini at the tenor; Natasha's coloratura in Dargomyzhsky's Mermaid by the dramatic soprano or Ratmir's aria from Ruslan and Lyudmila by the contralto.

Both the bass, the baritone and the tenor, as well as the mezzo-soprano and the dramatic soprano, always contain numerous works in the repertoire that require mastery of the technique of fluency. Let us recall, for example, Farlaf's rondo from Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila or Don Basilio's aria from Rossini's The Barber of Seville, at the bass; the arias of Figaro from the same opera and the aria of Don Giovanni from Mozart's baritone opera, the part of Almaviva from The Barber of Seville, Rossini at the tenor; Natasha's coloratura in Dargomyzhsky's Mermaid by the dramatic soprano or Ratmir's aria from Ruslan and Lyudmila by the contralto.

Fluency develops mainly on specially selected exercises and vocalizations. A remarkable contribution to the domestic vocal and methodological literature of recent times is a collection of exercises and vocalizations for the development of the fluency technique of high female voices, compiled by Professor of the Kyiv Conservatory M. E. Donets-Tesseir.

In all schools of singing and in any collection of vocalizations there is a part of exercises or vocalizations designed to develop fluency technique.

Good material for the development of fluency technique is provided by the mobile vocalizations of Zeidler, Konkone, Panofka and Lutgen.

The main principle of mastering singing in fast movement is a great gradualness in the complication of vocal tasks, both in terms of the very texture of the exercises, and in relation to the speed of execution. Unacceptable is excessively fast singing exercises when the student has not yet mastered it in a moderate movement. Only when the exercise is well learned and practiced in moderate movement can the pace be gradually accelerated. Unreasonably fast performance without sufficient preparation for it leads to lubrication of notes, to singing them in incorrect coordination. First you should master singing in fast movement of small scales, small arpeggiated moves, grace notes, gruppettos, leaving large, extended cadences, passages and trills for later stages.

Training the vocal apparatus on exercises and vocalizations in fast movement, in addition to instilling the necessary element of high technique, has a beneficial effect on the voice. Exercises in fast movement are a kind of gymnastics for the vocal apparatus, especially for the larynx. Under the influence of exercises in rapid movement, the larynx becomes more flexible, elastic, pliable to various adaptations to change movement, timbre colors. Properly selected exercises in fast movement help to liberate the vocal apparatus from unnecessary tension, stiffness, tightness or excessive promiscuity of its muscles.

One of the most common shortcomings of a young voice is its stiffness, heavy sound and congestion with breathing. The best means of combating these shortcomings is the development of fluency technique. An overloaded voice is clumsy, constrained. Until the singer finds a more correct relationship between the work of the larynx and breathing, fluency will not develop. Fluency makes the vocal apparatus find a different, more correct mode of its work. If a singer's voice is very difficult to develop in terms of the development of fluency technique, is not capable of quick movements, then this serves as a signal for the need to find a lighter sound that is more correct for this student.

If a singer's voice is very difficult to develop in terms of the development of fluency technique, is not capable of quick movements, then this serves as a signal for the need to find a lighter sound that is more correct for this student.

Forced voices happen to singers who use the power of their voices immoderately and usually sing badly in fast movement. Singing in slow motion, smooth singing allows the singer to force the sound. Rapid movement does not allow one to linger for a long time on one sound, and the singer, who is inclined to force, does not have time to develop a great sounding power on it. Therefore, fluency is one of the best means of combating forcing. The same need to quickly change notes does not allow the student to feel constrained or to make the sound heavy. His attention is occupied with having time to sing the required number of notes in the right rhythm, and the muscles of the vocal apparatus are tuned to perform this task, not having time to show vicious coordination, giving tightness or heaviness of the sound. Therefore, work on exercises in rapid movement leads to an improvement in sound formation in all students, if they are used moderately and reasonably.

Therefore, work on exercises in rapid movement leads to an improvement in sound formation in all students, if they are used moderately and reasonably.

In exercises in fast movement, another interesting property of the vocal apparatus is manifested, which can be called a kind of physiological inertia. Every teacher knows that the upper notes that fail in a student with smooth singing can be easier to take if they are made passing. In this case, they will turn out, as it were, by inertia; the same as everyone else, lower. In passing motion, the voice sounds equally even, even on those sounds on which it is distorted in slow motion. As we remember, this is due to the property of the inertia of the nervous system, which retains the once established type of activity and for which the transition to a different nature of work is associated with overcoming the established one.

This property of inertia in the implementation of movements is widely used by vocal pedagogy. Having adjusted the student to some type of sound or character of voice movement, the teacher translates him to difficult combinations of sounds, alternates good and bad sounds, counting on the transfer of good sound, due to the inertia of movements. The development of the upward range, so difficult for many singers, is also carried out in rapid movement drills. In slow movement, the singer tends to create additional efforts to sing unsuccessful sounds, and thereby distorts the correct operation of the vocal apparatus. In rapid movement, the voice apparatus learns to take. these notes for a short moment, but in correct coordination, the same with the previous sounds. The same quality of inertia is used in other cases, for example, when working on transitional sounds, in the development of mixed sounds, etc.

The development of the upward range, so difficult for many singers, is also carried out in rapid movement drills. In slow movement, the singer tends to create additional efforts to sing unsuccessful sounds, and thereby distorts the correct operation of the vocal apparatus. In rapid movement, the voice apparatus learns to take. these notes for a short moment, but in correct coordination, the same with the previous sounds. The same quality of inertia is used in other cases, for example, when working on transitional sounds, in the development of mixed sounds, etc.

Singing in fast motion allows you to make the most of the momentum of the movement.

When working on exercises in fast movement, one should always carefully monitor intonational accuracy, clarity of attack and accuracy of singing all notes. If for some reason they come out blurry, then you should first of all check whether they are sufficiently fixed by hearing. Often, students clearly know from which note the passage comes and to which note it leads, but they do not accurately imagine the intermediate sounds . .. To check, you should offer to sing it slowly or play it on the piano. If the passage fits well in the head, but still does not work out, it should be sung at a slower pace in staccato or with syllables. Rhythmic figurations and accents play an important role in developing the evenness of passages and scales. By moving accents or changing the rhythm of figures, it is possible to achieve evenness and clarity of various fast figurations.

.. To check, you should offer to sing it slowly or play it on the piano. If the passage fits well in the head, but still does not work out, it should be sung at a slower pace in staccato or with syllables. Rhythmic figurations and accents play an important role in developing the evenness of passages and scales. By moving accents or changing the rhythm of figures, it is possible to achieve evenness and clarity of various fast figurations.

About the concepts of "fluency" and "correctness" in teaching foreign languages

Language teaching methods | Philological Aspect: Methods of Teaching Language and Literature Methods of Teaching Language and Literature October 2020 - November 2020 No. 3 (6)

State University, RF, St. Petersburg, [email protected]

Annotation: This article is devoted to the peculiarities of the communicative approach to learning a foreign language. The focus of the work is on the issue of correctness and fluency of speech. When determining the need to choose in favor of the correctness or fluency of speech, the author indicates their direct relationship for successful communication.

Keywords: communicative approach, foreign language teaching, aspect, teaching methods, speech fluency, speech literacy.

Varnaeva Maria Lvovna

assistant professor, Saint Petersburg State University, Russia, Saint Petersburg

Abstract: The two particular issues of the communicative approach to learning and teaching a foreign language are scrutinized. Much attention is given to the issue of Accuracy and Fluency of speech. When deciding in favor of either Accuracy or Fluency of speech, the author denotes their close interconnection and interdependence to make the communication successful

Keywords: communicative approach, foreign language teaching, aspect, teaching methods, fluency, accuracy.

Reference

Varnaeva M.L. On the concepts of "fluency" and "correctness" in teaching foreign languages // Philological aspect: international scientific and practical journal. Ser.: Methods of teaching language and literature.2020. No. 03 (06). Access mode: https://scipress.ru/fam/articles/o-ponyatiyakh-beglost-i-pravilnost-v-obuchenii-inostrannym-yazykam.html (Date of access: 11/26/2020)

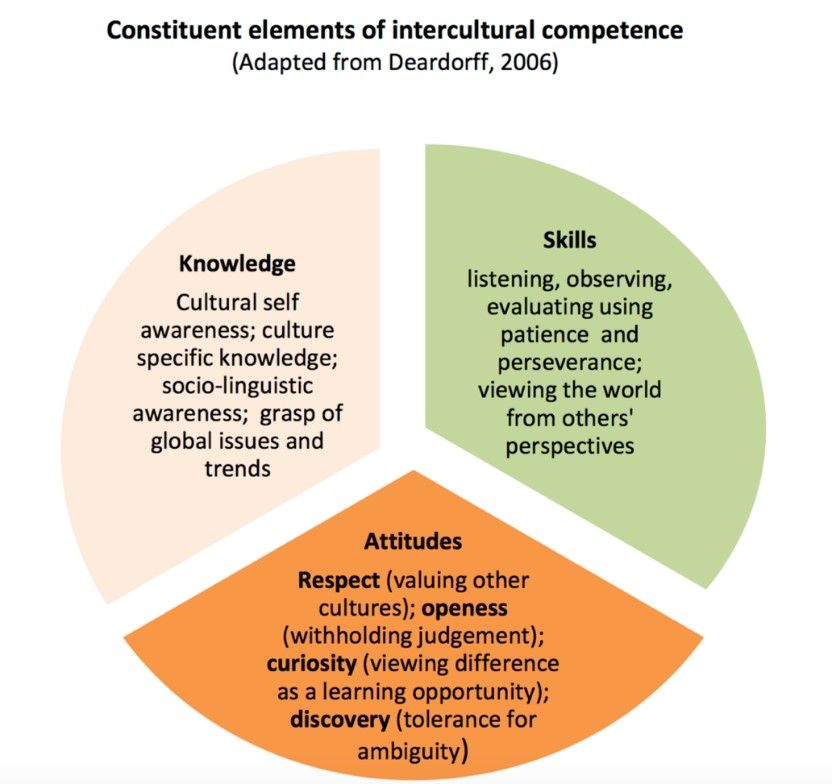

Language learning has always played an important role in both primary and higher education, and this remains unchanged. However, over time, the approach to teaching and learning languages has changed. At present, in the teaching of foreign languages in the Russian Federation, as well as throughout the world, a communicative approach to teaching foreign languages has been established: almost all teaching aids and materials used in secondary and higher schools, and even in numerous foreign language courses, have a communicative orientation, then there are we - teachers and lecturers - we teach (or should we teach?) our students not just a language, but oral and written communication in a foreign language. One of the fundamental contradictions in the communicative methodology, discussions about which do not stop, is the opposition of the concepts of "fluency" - "fluency" and "accuracy" - "accuracy, correctness, literacy". [ten; 8, p.166-174]

[ten; 8, p.166-174]

Theoretically, the teacher is well aware that students understand the speaker despite mistakes, and the communicative technique requires not to stop or correct the speaker when developing fluency, but this is often difficult, since the teacher is psychologically still focused on the literacy of the statement [11, p . 56-57]. It seems that here we should turn to the origins of the discussion about fluency and correctness and recall the detailed interpretation of these concepts by the founders of the communicative approach, where fluency is not understood as the speed of speech, but the ability to adequately express one's thoughts, albeit not always correctly. [11, p. 51-57], that is, the criterion of success is the successful communication.

However, another dilemma arises here: in all cases of real communication - not in the classroom - a fluent, but inaccurate statement from the point of view of literacy will testify to the success of communication? In informal communication with native English speakers, one often hears that the Russian language sounds rude, and the Russians themselves seem ill-mannered and straightforward [13]. It is clear about the Russian language: the sounds “r”, “zh”, the articulation of “t” and “d” and the intonation pattern of the utterance are very different from the sound of English speech, but the people themselves? An example of the “rudeness” of Russians can be examples of extremely polite phrases translated into English by a Russian-speaking participant in the dialogue. The most polite Russian formula would look like this: “Could you help me”, “Could you make me a cup of coffee, please”; the English semantic correspondence is “Could you make me a cup of coffe, please?”, the literal translation of which into Russian would be “could you make me ...” and in Russian it will no longer be a polite request, but a reproach. Those Russians who, speaking English, build their phrases based on translation from Russian make exactly this mistake - “Couldn’t you make me ...”, which will be perceived by an English speaker approximately as “What, couldn’t even make me a cup of coffee?” - a reproach, and in a rude way.

It is clear about the Russian language: the sounds “r”, “zh”, the articulation of “t” and “d” and the intonation pattern of the utterance are very different from the sound of English speech, but the people themselves? An example of the “rudeness” of Russians can be examples of extremely polite phrases translated into English by a Russian-speaking participant in the dialogue. The most polite Russian formula would look like this: “Could you help me”, “Could you make me a cup of coffee, please”; the English semantic correspondence is “Could you make me a cup of coffe, please?”, the literal translation of which into Russian would be “could you make me ...” and in Russian it will no longer be a polite request, but a reproach. Those Russians who, speaking English, build their phrases based on translation from Russian make exactly this mistake - “Couldn’t you make me ...”, which will be perceived by an English speaker approximately as “What, couldn’t even make me a cup of coffee?” - a reproach, and in a rude way. Meanwhile, a Russian person wanted to be very polite: in Russian, the most polite requests and questions include “not”: “Will you tell me”, “Don’t you know?” [9; 6, p. 137-152; 2]. Translated into English, such statements sound extremely rude, sometimes acquiring an offensive meaning: “Don't you know where the underground is near here”, and even with a Russian intonation, will be perceived approximately as “Well, you don’t know where underground!". Such errors are a normal phenomenon of interference - the influence of the native language on a foreign one in speech, but they not only do not contribute to successful communication, but, on the contrary, make it difficult and create a negative image of Russian among foreigners.

Meanwhile, a Russian person wanted to be very polite: in Russian, the most polite requests and questions include “not”: “Will you tell me”, “Don’t you know?” [9; 6, p. 137-152; 2]. Translated into English, such statements sound extremely rude, sometimes acquiring an offensive meaning: “Don't you know where the underground is near here”, and even with a Russian intonation, will be perceived approximately as “Well, you don’t know where underground!". Such errors are a normal phenomenon of interference - the influence of the native language on a foreign one in speech, but they not only do not contribute to successful communication, but, on the contrary, make it difficult and create a negative image of Russian among foreigners.

It is worth noting that any language is a reflection of the culture and character of the people. Even W. Humboldt pointed to the inseparability of language and thinking, to the fact that the grammatical forms inherent in a particular language reflect the mentality of the native speakers of this language. [3, p. 344–345].

[3, p. 344–345].

Widely known were his statements that "different languages in their essence, in their influence on different feelings are in fact different worldviews" and that "the originality of the language affects the essence of the nation, therefore a thorough study of the language should include everything that history and philosophy are associated with the inner world of man" [5, p. 370, 377]. He talks about the inner form of the language, which is a purely individual and unique formation, the spiritual mood of those who speak the same language, an individual impulse through which this or that people embodies their thoughts and feelings in the language [4, p. 100-107]. In order to learn to speak a foreign, in this case English, language, a certain system or teaching methodology is needed that would allow solving the tasks as fully as possible, namely: to acquire the skills of reading, understanding speech by ear, speaking and writing in the language being studied - Reading, Listening , Speaking and Writing skills [7]. Thus, the technique is understood as a set of tasks and exercises that helps to practice all the above skills in practice. Given that language abilities are different for everyone, and the tasks at different levels are different, the teacher constantly has to apply different approaches to learning and teaching.

Thus, the technique is understood as a set of tasks and exercises that helps to practice all the above skills in practice. Given that language abilities are different for everyone, and the tasks at different levels are different, the teacher constantly has to apply different approaches to learning and teaching.

In the communicative approach to language learning, the most important question is whether communication has taken place. The text should be clear, its purpose is to extract information. “All classes that are developed according to the principles of this modern method of teaching English are, if possible, conducted in a foreign language, or with a minimum inclusion of native speech. Moreover, the teacher only directs the students, asks them questions and creates a communicative situation, while 70% of the time of the entire lesson, the students speak” [7]. Based on this, it becomes obvious that the fundamental point is Fluency - fluency of speech, the correctness of speech - Accuracy - goes by the wayside. Much less time is devoted to grammar, not to mention the direct development of individual skills, and even more so grammatical structures. This often leads to a misunderstanding between two communicators, one of which is a native speaker, and the other is a student, i.e. there is a break in communication. The question arises - "What is more important, Fluency or Accuracy"? It turns out that if it is important for communication to take place, then fluency should not lead to a break in communication, which means that it is necessary to observe some grammatical norms, i.e. speech should be relatively literate - Accurate.

Much less time is devoted to grammar, not to mention the direct development of individual skills, and even more so grammatical structures. This often leads to a misunderstanding between two communicators, one of which is a native speaker, and the other is a student, i.e. there is a break in communication. The question arises - "What is more important, Fluency or Accuracy"? It turns out that if it is important for communication to take place, then fluency should not lead to a break in communication, which means that it is necessary to observe some grammatical norms, i.e. speech should be relatively literate - Accurate.

However, despite the fact that there are always at least two parties in communication (writer / speaker and reader / listener), it is necessary to distinguish between written speech and oral speech, when the interlocutor has the opportunity to ask again in order to clarify information.

In written speech, it is important to take into account that for a correct understanding, its correct presentation is necessary. Therefore, while practicing reading skills (Reading Skills) and writing (Writing Skills) of texts, it is important not only to understand or know individual grammatical structures, but also to be able to use them to convey the necessary information. It is very important when you write that the addressee catches exactly what the author wanted to express, and the author expressed exactly what he wanted. And here, when there is no way to ask again or clarify information, the correct use of language units - Accuracy - comes to the fore. Otherwise, it will lead to a break in communication.

Therefore, while practicing reading skills (Reading Skills) and writing (Writing Skills) of texts, it is important not only to understand or know individual grammatical structures, but also to be able to use them to convey the necessary information. It is very important when you write that the addressee catches exactly what the author wanted to express, and the author expressed exactly what he wanted. And here, when there is no way to ask again or clarify information, the correct use of language units - Accuracy - comes to the fore. Otherwise, it will lead to a break in communication.

However, the above does not mean that there are no situations in oral speech when literacy or correctness - Accuracy - plays an important role and replaces fluency. Even speaking fluently, sometimes you can not make phonetic and intonation mistakes. There are communicative situations in which there are stable language formulas aimed at their correct use in terms of grammar and phonetics. The intonation pattern of the utterance is important. However, the communicative technique does not aim to work out the aspect of grammar - Accuracy. This can be explained by the fact that in real life we often encounter a situation where we feel more comfortable in the company of people who, although poorly, speak your native, understandable language, rather than in the company of those who will speak fluently, competently , observing all the rules of the language, but which will be alien and incomprehensible. It turns out, from a practical point of view, in real colloquial (oral) speech, fluency may play a more important role, but we, as teachers, should not put up with and accept these mistakes in speech, our task is to try to make sure that our students could speak not only fluently (Fluently), but also correctly (Accurately).

However, the communicative technique does not aim to work out the aspect of grammar - Accuracy. This can be explained by the fact that in real life we often encounter a situation where we feel more comfortable in the company of people who, although poorly, speak your native, understandable language, rather than in the company of those who will speak fluently, competently , observing all the rules of the language, but which will be alien and incomprehensible. It turns out, from a practical point of view, in real colloquial (oral) speech, fluency may play a more important role, but we, as teachers, should not put up with and accept these mistakes in speech, our task is to try to make sure that our students could speak not only fluently (Fluently), but also correctly (Accurately).

So, what is fluency in speech and how to develop literacy in it? Fluency is understood as the communicative quality of speech, which demonstrates the ability and ability for fluent spontaneous statements in accordance with the principles of oral speech, possession of various language means [1, p. 27]. This is the ability to easily and well express one's thoughts both in writing and orally, without the need to build a thought for a long time [12]. It is possible to achieve this, it is necessary already at the initial stage to work out certain conversational formulas to automatism - linguistic means that allow you to express greetings, farewells, requests, negotiations, etc. Knowledge and ability to correctly use these colloquial formulas, observing the correct intonation pattern, allow you to observe Accuracy with Fluency, i.e. fluency does not affect literacy.

27]. This is the ability to easily and well express one's thoughts both in writing and orally, without the need to build a thought for a long time [12]. It is possible to achieve this, it is necessary already at the initial stage to work out certain conversational formulas to automatism - linguistic means that allow you to express greetings, farewells, requests, negotiations, etc. Knowledge and ability to correctly use these colloquial formulas, observing the correct intonation pattern, allow you to observe Accuracy with Fluency, i.e. fluency does not affect literacy.

References

1. Azimov EG, Shchukin AN New dictionary of methodological terms and concepts (theory and practice of teaching languages). - Moscow, 2009. 448s.

2. Burikova S.A., Smirnova I.V. Intercultural approach in teaching foreign languages as a reflection of intercultural differences. // Society: sociology, psychology, pedagogy. - 2017, issue 11. / El. resource. / Access mode: https://doi.org/10.24158/spp. 2017.11. – (Last accessed 10.09.20)

2017.11. – (Last accessed 10.09.20)

3. Humboldt V. On the emergence of grammatical forms and their influence on the development of ideas. // Selected works on linguistics. Moscow: Progress, 1984. S. 327-350. 397 p.

4. Humboldt V. fon. On the difference in the structure of human languages and its influence on the spiritual development of mankind / / Selected works on linguistics. M.: Progress, 1984. S. 37-301. 397 p.

5. Humboldt V. fon. Language and philosophy of culture. M.: Progress, 1985. 450 p.

6. Larina TV Category of politeness and style of communication. M., 2009. 317 p.

7. Lim English. Methods of teaching foreign languages. /Email resource/. Access mode: https://lim-english.com/posts/metodiki-obycheniya-angliiskomy-yaziky/ – (Last accessed 12.09.2020).

8. Polyakov O.G., Tormyshova T.Yu. Fluency in speaking a foreign language as a linguistic and methodological problem. // Language and culture, 2014, issue 4(28). pp.166-174. /Email resource/. Access mode: https://cyberleninka. ru/viewer_images/15702478/f/1.png. – (Last accessed 11/10/20).

ru/viewer_images/15702478/f/1.png. – (Last accessed 11/10/20).

9. Speech etiquette. // Email resource/. Access mode: https://etikket.ru/rechevoj-etiket/prosba-v-rechevom-etikete.html. – (Last accessed 11/10/20).

10. Stepanova E. Glossary of terms on the methodology of teaching English. // Email resource. – Access mode: http://filolingvia.com/publ/80-1-0-1505. – (Last accessed 11/08/20).

11. Brumfit C. Communicative Methodology in Languge Teaching. The roles of fluency and accuracy. Cambridge University Press, 1992. 166 p.

12. Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus © Cambridge University Press. Year of publication Number of pages, p. 000. //El. resource. – Access mode: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/ru, – (Last accessed 11/10/20)

13.Spoken English //El. resource/. Access mode:

https://zen.yandex.ru/media/id/5beac6b6684fe000b389d9d3/pochemu-anglogovoriascim-russkie-kajutsia-grubymi-liudmi-5ecd382a06be4a5dc02717ab. – (Last accessed 02.11.20).