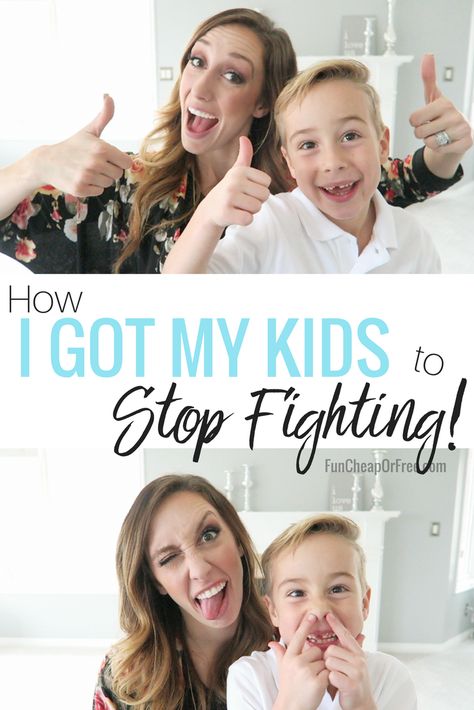

Kids fighting parents

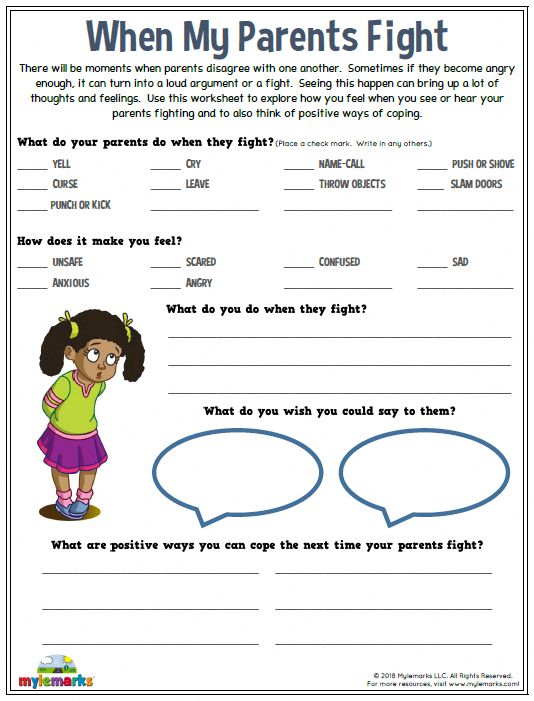

What Happens to Kids When Parents Fight

When I was a child, my parents’ fights could suck the oxygen out of a room. My mother verbally lashed my father, smashed jam jars, and made outlandish threats. Her outbursts froze me in my tracks. When my father fled to work, the garage, or the woods, I felt unprotected.

“Children are like emotional Geiger counters,” says E. Mark Cummings, psychologist at Notre Dame University, who, along with colleagues, has published hundreds of papers over twenty years on the subject. Kids pay close attention to their parents’ emotions for information about how safe they are in the family, Cummings says. When parents are destructive, the collateral damage to kids can last a lifetime.

My experience led me to approach marriage and parenthood with more than a little caution. As a developmental psychologist I knew that marital quarrelling was inevitable. According to family therapist Sheri Glucoft Wong, of Berkeley, California, just having children creates more conflicts, even for couples who were doing well before they became parents.

“When kids show up, there’s less time to get more done,” she says. “All of a sudden you’re not as patient, not as flexible, and it feels like there’s more at stake.”

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

But I also knew that there had to be a better way to handle conflict than the one I grew up with. When my husband and I decided to have children, I resolved never to fight in front of them. “Conflict is a normal part of everyday experience, so it’s not whether parents fight that is important,” says Cummings. “It’s how the conflict is expressed and resolved, and especially how it makes children feel, that has important consequences for children.”

Watching some kinds of conflicts can even be good for kids—when children see their parents resolve difficult problems, Cummings says, they can grow up better off.

What is destructive conflict?

In their book Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective, Cummings and colleague Patrick Davies at the University of Rochester identify the kinds of destructive tactics that parents use with each other that harm children:

- Verbal aggression like name-calling, insults, and threats of abandonment;

- Physical aggression like hitting and pushing;

- Silent tactics like avoidance, walking out, sulking, or withdrawing;

- Capitulation—giving in that might look like a solution but isn’t a true one.

When parents repeatedly use hostile strategies with each other, some children can become distraught, worried, anxious, and hopeless. Others may react outwardly with anger, becoming aggressive and developing behavior problems at home and at school. Children can develop sleep disturbances and health problems like headaches and stomachaches, or they may get sick frequently. Their stress can interfere with their ability to pay attention, which creates learning and academic problems at school. Most children raised in environments of destructive conflict have problems forming healthy, balanced relationships with their peers. Even sibling relationships are adversely affected—they tend to go to extremes, becoming overinvolved and overprotective of each other, or distant and disengaged.

Some research suggests that children as young as six months register their parents’ distress. Studies that follow children over a long period of time show that children who were insecure in kindergarten because of their parents’ conflicts were more likely to have adjustment problems in the seventh grade. A recent study showed that even 19-year-olds remained sensitive to parental conflict. Contrary to what one might hope, “Kids don’t get used to it,” says Cummings.

A recent study showed that even 19-year-olds remained sensitive to parental conflict. Contrary to what one might hope, “Kids don’t get used to it,” says Cummings.

In a remarkable 20-year-old study of parental conflict and children’s stress, anthropologists Mark Flinn and Barry England analyzed samples of the stress hormone cortisol, taken from children in an entire village on the east coast of the island of Dominica in the Caribbean. Children who lived with parents who constantly quarreled had higher average cortisol levels than children who lived in more peaceful families. As a result, they frequently became tired and ill, they played less, and slept poorly. Overall, children did not ever habituate, or “get used to,” the family stress. In contrast, when children experienced particularly calm or affectionate contact, their cortisol decreased.

More recent studies show that while some children’s cortisol spikes, other children’s cortisol remains abnormally low and blunted, and these different cortisol patterns seem to be associated with different kinds of behavioral problems in middle childhood. Other physiological regulatory systems can become damaged as well, such as the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system—these help us respond to a perceived threat but are also the “brakes” that rebalance and calm us.

Other physiological regulatory systems can become damaged as well, such as the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system—these help us respond to a perceived threat but are also the “brakes” that rebalance and calm us.

In 2002, researchers Rena Repetti, Shelley Taylor, and Teresa Seeman at UCLA looked at 47 studies that linked children’s experiences in risky family environments to later issues in adulthood. They found that those who grew up in homes with high levels of conflict had more physical health problems, emotional problems, and social problems later in life compared to control groups. As adults, they were more likely to report vascular and immune problems, depression and emotional reactivity, substance dependency, loneliness, and problems with intimacy.

Avoiding conflict is not a solution

-

Conflict Tips

Courtesy of Sheri Glucoft Wong.

1. Lead with empathy: Open the dialog by first letting the other person know that you see them, you get them, and you can put yourself in their shoes.

2. Give your partner the benefit of the doubt: Assume the best intentions and help yourself remember that you love each other by adding an endearment.

3. Remember that you’re on the same team. Deal with issues by laying all the cards on the table and looking at them together to solve a dilemma rather than digging in on opposing sides. Then problem-solve with one another.

4. Constructive criticism only works when your partner can do something about what happened. If the deadline for soccer signup was already missed, remedy the current situation as best as possible and talk about how to do it better next time. Blaming won’t fix anything that’s already happened.

5. Anything that needs to be said can be said with kindness. Disapproval, disappointment, exasperation—all can be handled better with kindness.

Some parents, knowing how destructive conflict can be, may think that they can avoid affecting their children by giving in, or capitulating, in order to end an argument. But that’s not an effective tactic. “We did a study on that,” Cummings said. According to parents’ records of their fights at home and their children’s reactions, kids’ emotional responses to capitulation are “not positive.” Nonverbal anger and “stonewalling”—refusing to communicate or cooperate—are especially problematic.

But that’s not an effective tactic. “We did a study on that,” Cummings said. According to parents’ records of their fights at home and their children’s reactions, kids’ emotional responses to capitulation are “not positive.” Nonverbal anger and “stonewalling”—refusing to communicate or cooperate—are especially problematic.

“Our studies have shown that the long-term effects of parental withdrawal are actually more disturbing to kids’ adjustment [than open conflict],” says Cummings. Why? “Kids understand hostility,” he explains. “It tells them what’s going on and they can work with that. But when parents withdraw and become emotionally unavailable, kids don’t know what’s going on. They just know things are wrong. We’re seeing over time, that parental withdrawal is actually a worse trajectory for kids. And it’s harder on marital relationships too.”

Kids are sophisticated conflict analysts; the degree to which they detect emotion is much more refined than parents might guess. “When parents go behind closed doors and come out acting like they worked it out, the kids can detect that,” says Cummings. They’ll see you’re pretending. And pretending is actually worse in some ways. As a couple, you can’t resolve a fight you’re not acknowledging you’re having. Kids will know it, you’ll know it, but nothing will be made in terms of progress.”

They’ll see you’re pretending. And pretending is actually worse in some ways. As a couple, you can’t resolve a fight you’re not acknowledging you’re having. Kids will know it, you’ll know it, but nothing will be made in terms of progress.”

On the other hand, he says, “When parents go behind closed doors and are not angry when they come out, the kids infer that things are worked out. Kids can tell the difference between a resolution that’s been forced versus one that’s resolved with positive emotion, and it matters.”

How to make conflict work

“Some types of conflicts are not disturbing to kids, and kids actually benefit from it,” says Cummings. When parents have mild to moderate conflict that involves support and compromise and positive emotions, children develop better social skills and self-esteem, enjoy increased emotional security, develop better relationships with parents, do better in school and have fewer psychological problems.

“When kids witness a fight and see the parents resolving it, they’re actually happier than they were before they saw it,” says Cummings. “It reassures kids that parents can work things through. We know this by the feelings they show, what they say, and their behavior—they run off and play. Constructive conflict is associated with better outcomes over time.” Children feel more emotionally secure, their internal resources are freed up for positive developmental growth, and their own pro-social behavior toward others is enhanced. In fact, many child behavior problems can be solved not by focusing on the child, or even the parent-child relationship, but simply by improving the quality of the parents’ relationship alone, which strengthens children’s emotional security.

“It reassures kids that parents can work things through. We know this by the feelings they show, what they say, and their behavior—they run off and play. Constructive conflict is associated with better outcomes over time.” Children feel more emotionally secure, their internal resources are freed up for positive developmental growth, and their own pro-social behavior toward others is enhanced. In fact, many child behavior problems can be solved not by focusing on the child, or even the parent-child relationship, but simply by improving the quality of the parents’ relationship alone, which strengthens children’s emotional security.

Even if parents don’t completely resolve the problem but find a partial solution, kids will do fine. In fact, their distress seems to go down in proportion to their parents’ ability to resolve things constructively. “Compromise is best, but we have a whole lot of studies that show that kids benefit from any progress toward resolution,” says Cummings.

Both Cummings and Glucoft Wong agree that children can actually benefit from conflict—if parents manage it well. “Parents should model real life…at its best,” says Glucoft Wong. “Let them overhear how people work things out and negotiate and compromise.”

“Parents should model real life…at its best,” says Glucoft Wong. “Let them overhear how people work things out and negotiate and compromise.”

However, both also agree that some content is best kept private. Discussions about sex or other tender issues are more respectfully conducted without an audience. Glucoft Wong encourages parents to get the help they need to learn to communicate better—from parenting programs, from books, or from a therapist.

My own parents’ conflict no longer has the hold on me that it once did, thanks to careful work and a loving marriage of my own of thirty years. Our two daughters are now in their twenties and secure in their own loving partnerships, and I hope that the lessons of their childhood hold. When they were preschoolers and interrupted our disagreements with concern, my husband and I would smile and reassure them with our special code: I held my fingers an inch apart and reminded them that the fight was this big, but that the love was this big—and I held my arms wide open.

What Happens to Children When Parents Fight — Developmental Science

When I was a child, my parents’ fights could suck the oxygen out of a room. My mother verbally lashed my father, broke jam jars, and made outlandish threats. Her outbursts froze me in my tracks. When my father fled to work, the garage, or the woods, I felt unprotected. Years later, when my husband and I decided to have children, I resolved never to fight in front of them.

“Children are like emotional Geiger counters,” says E. Mark Cummings, psychologist at Notre Dame University, who, along with colleagues, has published hundreds of papers over twenty years on the subject. Kids pay close attention to their parents’ emotions for information about how safe they are in the family, Cummings says. When parents are destructive, the collateral damage to kids can last a lifetime.

As a developmental psychologist I knew that marital quarreling was inevitable but I also knew that there had to be a better way to handle it. Cummings confirms: “Conflict is a normal part of everyday experience, so it’s not whether parents fight that is important. It’s how the conflict is expressed and resolved, and especially how it makes children feel that has important consequences for children.” Watching some kinds of conflicts can even be good for kids—when children see their parents resolve difficult problems, Cummings says, they can grow up better off.

Cummings confirms: “Conflict is a normal part of everyday experience, so it’s not whether parents fight that is important. It’s how the conflict is expressed and resolved, and especially how it makes children feel that has important consequences for children.” Watching some kinds of conflicts can even be good for kids—when children see their parents resolve difficult problems, Cummings says, they can grow up better off.

What is destructive conflict?

In their book Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective, Cummings and colleague Patrick Davies from the University of Rochester identify the kinds of destructive tactics that parents use with each other that harm children: verbal aggression like name-calling, insults, and threats of abandonment; physical aggression like hitting and pushing; silent tactics like avoidance, walking out, sulking or withdrawing; or even capitulation—giving in that might look like a solution but isn’t a true one.

When parents repeatedly use hostile strategies with each other, some children can become distraught, worried, anxious and hopeless. Others may react outwardly with anger, becoming aggressive and developing behavior problems at home and at school. Children can develop sleep disturbances and health problems like headaches and stomachaches, or they may get sick frequently. Their stress can interfere with their ability to pay attention and create learning and academic problems at school. Most children raised in environments of destructive conflict have problems forming healthy, balanced relationships with their peers. Even sibling relationships are adversely affected—they can become overinvolved and overprotective of each other, or distant and disengaged.

Some research suggests that children as young as six months register their parents’ distress. Studies that follow children over a long period of time show that children who were insecure in kindergarten because of their parents’ conflicts were more likely to have adjustment problems in the seventh grade. A recent study showed that even 19-year-olds remained sensitive to parental conflict. Contrary to what one might hope, “Kids don’t get used to it,” says Cummings.

A recent study showed that even 19-year-olds remained sensitive to parental conflict. Contrary to what one might hope, “Kids don’t get used to it,” says Cummings.

In 2002, researchers Rena Repetti, Shelley Taylor, and Teresa Seeman at UCLA looked at 47 studies that linked children’s experiences in risky family environments to later issues in adulthood. They found that those who grew up in homes with high levels of conflict had more physical health problems, emotional problems, and social problems later in life compared to control groups. As adults, they were more likely to report vascular and immune problems, depression and emotional reactivity, substance dependency, loneliness, and problems with intimacy.

Some parents may think that they can avoid impacting their children by giving in, or capitulating, to end an argument. But that’s not an effective tactic. “We did a study on that,” Cummings said. According to parents’ records of their fights at home and their children’s reactions, kids’ emotional responses to capitulation are “not positive. ” Nonverbal anger and “stonewalling”—refusing to communicate or cooperate—are especially problematic.

” Nonverbal anger and “stonewalling”—refusing to communicate or cooperate—are especially problematic.

“Our studies have shown that the long-term effects of parental withdrawal are actually more disturbing to kids’ adjustment [than open conflict],” says Cummings. Why? “Kids understand hostility,” he explains, “it tells them what’s going on and they can work with that. But when parents withdraw and become emotionally unavailable, kids don’t know what’s going on. They just know things are wrong. We’re seeing over time, that withdrawal is actually a worse trajectory for kids. And it’s harder on marital relationships too.”

Kids are sophisticated conflict analysts; the degree to which they detect emotion is much more refined than parents might guess. “When parents go behind closed doors and come out acting like they worked it out, the kids can detect that,” says Cummings. They’ll see you’re pretending. And pretending is actually worse in some ways. As a couple, you can’t resolve a fight you’re not acknowledging you’re having. Kids will know it, you’ll know it, but nothing will be made in terms of progress.”

Kids will know it, you’ll know it, but nothing will be made in terms of progress.”

On the other hand, he says, “When parents go behind closed doors and are not angry when they come out, the kids infer that things are worked out. Kids can tell the difference between a resolution that’s been forced versus one that’s resolved with positive emotion, and it matters.”

How do researchers study conflict?

Researchers use several methods to see how parents’ conflicts affect their children, in the home and in the laboratory. At home, parents are trained to keep records or diaries of their fights, including when they fought, what they fought about, the strategies they used, and how they thought their children reacted. In the laboratory, parents are recorded while discussing a difficult topic, and their strategies are analyzed. Children are shown videotapes of adults’ or even their own parents’ conflicts and are asked about their reactions: How would you feel if your parents did that; how would you describe what your parents are doing? Some studies also gather information from teachers, school records, or even record children’s physiological responses while watching a videotape of adults or their own parents fighting.

In a remarkable 20-year old study of interparental conflict and children’s stress, anthropologists Mark Flinn and Barry England analyzed samples of the stress hormone cortisol, taken from children in an entire village on the east coast of the island of Dominica in the Caribbean. Children who lived with parents who constantly quarreled and fought had higher average cortisol levels than children who lived in more peaceful families. As a result, they frequently became tired and ill, they played less, and slept poorly. Overall, children did not ever habituate, or “get used to,” the family stress. In contrast, when children experienced particularly calm or affectionate contact, their cortisol decreased. Both animal and human studies show that chronic activation of the stress response can change the architecture of a developing brain: turning on or off genes that regulate stress; damaging the hippocampus which can lead to impairments in learning and memory as well as the stress response; and interfering with myelination of the brain which affects the quality of nerve signal transmission.

The long-term protection of constructive conflict

“Some types of conflicts are not disturbing to kids, and kids actually benefit from it,” says Cummings. When parents have mild to moderate conflict that involves support and compromise and positive emotions, children develop better social skills and self-esteem, enjoy increased emotional security, develop better relationships with parents, do better in school and have fewer psychological problems.

“When kids witness a fight and see the parents resolving it, they’re actually happier than they were before they saw it,” says Cummings. “It reassures kids that parents can work things through. We know this by the feelings they show, what they say, and their behavior—they run off and play. Constructive conflict is associated with better outcomes over time.”

Even if parents don’t completely resolve the problem but find a partial solution, kids will do fine. “Compromise is best, but we have a whole lot of studies that show that kids benefit from any progress toward resolution,” says Cummings.

Fighting escalates when partners become parents.

According to family therapist Sheri Glucoft Wong, of Berkeley, California, just having children creates more conflicts, even for couples who were doing well before they became parents. “When kids show up, there’s less time to get more done,” she says. “All of a sudden you’re not as patient, not as flexible, and it feels like there’s more at stake. People who make that adjustment successfully talk about it. They make the implicit explicit. Have compassion,” she adds.

What do parents fight about?

“I’ve been doing family therapy for four decades, and digital issues have really, really added new challenges to families,” says Glucoft Wong. “How much screen time is okay, can kids text in the car, expectations about immediate connectivity, and resentment when someone doesn’t return a call right away. Couples’ relationship time is diminished because partners are spending more time interacting with online relationships, dinnertime conversations are interrupted to fact-check, and entertainment is constantly available. There is a whole new etiquette to work out.”

There is a whole new etiquette to work out.”

“Roommate issues” are the second big category, according to Glucoft Wong: who does what, when; comings and goings; sleeping times and arrangements, and carving out time for the parents to connect with each other. And finally, there are the usual issues of money, in-laws, friends, values, parenting, discipline, and roles.

Should parents work out their conflicts in front of their kids?

Both researcher Cummings and therapist Glucoft Wong are circumspect. Cummings: “You should be careful about the fights you have in front of your kids. What our research is showing is that parents tend to have worse fights in front of their kids. They’re unable to regulate themselves.”

Glucoft Wong’s philosophy is that home is a training ground for real life: “Little eyes are watching, and little ears are listening,” she says.

Both Cummings and Glucoft Wong agree that children can benefit if parents manage conflict well. “Parents should model real life…at its best,” says Glucoft Wong. “Let them overhear how people work things out and negotiate and compromise.” But both agree that some content is best kept private. Discussions about sex or other tender issues are more respectfully conducted without an audience. Glucoft Wong encourages parents to get the help they need to learn to communicate better—from parenting programs, from books, or from a therapist.

“Let them overhear how people work things out and negotiate and compromise.” But both agree that some content is best kept private. Discussions about sex or other tender issues are more respectfully conducted without an audience. Glucoft Wong encourages parents to get the help they need to learn to communicate better—from parenting programs, from books, or from a therapist.

My own parents’ conflict no longer has the hold on me that it once did, thanks to careful work and a loving marriage of my own of thirty years. Our two daughters are now in their twenties and forming partnerships of their own, and I hope that the lessons of their childhood hold. When they were preschoolers and interrupted our disagreements with concern, my husband and I would smile and reassure them with our special code: I held my thumb and finger an inch apart and reminded them that the fight was this big, but that the love was this big – and I held my arms wide open.

Tips for Resolving Conflict

Glucoft Wong shares her top five tips to help parents resolve conflict, maintain a loving relationship, and role-model effective problem-solving for children:

Lead with empathy: Open the dialog by first letting the other person know that you see them, you get them, and you can put yourself in their shoes.

Example: “I know it must be hard to leave work….”

Example: “I know it must be hard to leave work….”Give your partner the benefit of the doubt. Assume the best intentions and help yourself remember that you love each other by adding an endearment. Example: “I know you didn’t mean to team up with the kids against me, Sweetheart….”

Remember that you’re on the same team. Deal with issues by laying all the cards on the table and looking at them together to solve a dilemma rather than digging in on opposing sides. Then problem-solve with one another. That way you both “own” the solution.

Constructive criticism only works when your partner can do something about what happened. If the deadline for soccer signup was already missed, remedy the current situation as best as possible and talk about how to do it better next time. Blaming won’t fix anything that’s already happened.

Anything that needs to be said can be said with kindness. Disapproval, disappointment, exasperation—all can be handled better with kindness.

Children fight so much that mom is scared

We discussed this problem with a medical psychologist, researcher at the National Medical Research Center for Children's Health Maria Afonina .

– Let's imagine a situation: there are two children in a family, 10 and 7 years old. Outside the family, the boys act together, but they fight among themselves so that mom is scared.

Reason 1: children fight for their parents' attention

– Each child wants to be the only one in the family. From birth, the eldest child is constantly in the center of attention, and often not only parents, but the whole large family, they admire him, rejoice at his successes, devote all their free time.

With the birth of the youngest, the status of being the only one disappears, the child becomes the “senior”, which provokes feelings of envy, jealousy, a subconscious desire to “return as it was”.

The situation is somewhat different with the younger child. He has never been the only one, he constantly has to share parental love, care with someone else. Of course, he also wants to become the only one for his parents.

He has never been the only one, he constantly has to share parental love, care with someone else. Of course, he also wants to become the only one for his parents.

These desires and feelings are not always realized by a child, although from many children at the peak of emotions one can hear: “It would be better if you did not give birth to him!” "I wish I were alone!" - and other words frightening parents.

In such situations, it is important to tell the baby that you love him very much, that you want to be with him, spend time, share important moments.

The feeling of jealousy in the older child often decreases at the moment of the birth of the third baby: finally, he alone has to compete for the attention of his parents, now the middle child has to do it too. It is believed that middle children are in the most unfavorable position - on the one hand, they are commanded by the elders, on the other hand, the baby still gets more attention from the mother.

Reason 2: children are encouraged to compete Maria Afonina, clinical psychologist, researcher at the National Medical Research Center for Children's Health.

Photo: Pavel Smertin

Photo: Pavel Smertin Our society is built on competition and comparison, and this applies not only to adults, but also to children. For example, parents, educators, grandparents constantly say about one: “Such a good fellow! How fast do you get dressed! How well you eat!”

And about the second child, they note that he digs, hesitates, is constantly serious, sad. Such an assessment, even if the parents themselves do not want to compare children, can be perceived by one and the other baby as a comparison, as if someone is better and someone is worse.

– But this is the favorite method of some older relatives! They find it motivating.

- The evaluation situation is not useful for any child.

The one who gets the most praise gets used to the fact that everything in his life should be appreciated by others.

And if suddenly at some point he is not evaluated, praised, he will feel helpless, will not be able to understand whether he is doing the right thing or not. That is, in order for him to feel confident, he needs a constant external positive assessment.

That is, in order for him to feel confident, he needs a constant external positive assessment.

A child who is evaluated negatively will get used to the fact that he is a "loser", which will lead to the formation of low self-esteem, a negative image of "I".

A child should be praised for what he is successful in, without comparing with anyone. For example, you should not say: “Pasha got dressed faster than Vasya today.”

It is better to point to specific achievements: “Yesterday you didn’t know how to tie your shoelaces, but today you can already do it, well done”, “Yesterday you had more mistakes in your notebook, but you worked.”

It is useful to focus on the efforts, diligence, ability to overcome difficulties, bring the work started to the end, note the interests and inclinations of the child. For example: "It's nice that you are interested in history, doing projects, it's great when a person has an interest and favorite activity."

Reason 3: children feel something like injustice

The feeling of injustice arises in the older preschool age, but is especially acutely felt by adolescents. Of course, with age, this feeling changes, acquiring a more complex structure and other content.

Of course, with age, this feeling changes, acquiring a more complex structure and other content.

For example, at the age of six, it would be unfair if someone suddenly broke the rules in the game.

For a younger student, it's injustice when the older one can go out until 11 pm, but he can't.

And it is unfair for a teenager that he has to wash the dishes, while the younger ones do not.

Reason 4: the child is deprived of personal space Photo: Alena Darmel/pexels.com

A very common reason for conflicts is when the younger one is “hung up” on the older one. For example, an older teenage child wants to go somewhere with friends, and parents ask to take their younger brother or sister with them. Or they should go to a New Year's holiday, a concert together.

Parents act out of good intentions - they think that if the children are together all the time, they will become friends.

But an older child, especially a teenager, already wants to have his own personal territory, and parents should listen to him.

The fact that each of the children has their own activities, interests, social circle and the opportunity to exchange impressions of their lives with each other will only strengthen their relationship.

Time of fights: from three to nine, then less often

The real fights between siblings start when the youngest is able to answer - around the age of two or three. At this age, the youngest child begins to realize himself, to understand and feel his own interests, desires, opportunities. He enters the era of the crisis of three years, the motto of which is the words: "I myself!".

Therefore, if the older brother or sister continues to lead, command, indicate what they should play together, how to spend time, the younger one will start to fight, demanding that his opinion be listened to.

Fighting will subside a little in elementary school - when children with a small difference in age are already in the same status. Teenagers also have little to share, as well as children with a big age difference.

Children will never name the real reason Photo: RODNAE Productions/pexels.com

Children will most likely name the cause of the fight as some action that actually just became a “trigger”: one child threw a toy, another called something. In fact, the causes of fights are hidden throughout the life of the child. It is clear that if a child is in a stable emotional state, during the day in kindergarten or at school he did not have exciting events, he ate, slept, nothing hurts him, he will not even notice that his brother took his toy or how laughed at him.

And if he quarreled with the children in the kindergarten, he was tired, he didn't feel well, he didn't eat, and he was yelled at by his mother, who returned after a busy day, and she was in trouble at work, a fight would break out much more likely.

By the way, if the mother herself is in a calm state, conflict situations in children will occur less frequently. Just because the children know that they can come up to their mother at any time and discuss something.

Fights, as a rule, happen at the moment when the mother is least ready for it - annoyed, upset when she does not have the resource to communicate with the children.

During stressful periods in family life - when parents quarrel, someone gets sick or changes jobs, fights happen more often. Emotional contact with the mother is so important for children that if the mother is distracted from the children by something else and it is impossible to return her attention in other ways, the children begin to fight.

It is very important in this situation not to start looking for the “magic button”, after pressing which the child will immediately stop fighting, lying or being afraid of the dark.

I must first assess my condition and see if I can do this now. If the mother's condition is unstable, it is worth looking for an adult assistant to whom you can shift some of your problems, or who will stop fights and talk to the children.

Fight prevention Photo: Polesie Toys/pexels.

com

com Step 1: Spend some time alone with your elder

Fight prevention starts the moment you expect your second baby or the moment your baby is born. It is very important for parents to remember that with the advent of the younger, the older child does not automatically become an adult.

It is very important for each of the parents to continue to spend time alone with the older child, and not just the three of us with the baby. It is important that the mother notice the feelings of the older child and recognize that he can be upset and angry, can be aggressive. And this happens not because he is angry or bad, but because he is upset.

A mother might say to an older child, for example, “I can see that you are upset and angry. But now I will feed the little one, and then we will play your favorite game with you.

If this is done constantly, from the very moment the second child appears in the family, most likely, the elder will not fight for parental love so fiercely.

Step 2. Give each child time

Time should be divided according to need. Naturally, a very young child needs it more than an older child. To the one who is ill, more than to the healthy. A child who has just gone to kindergarten has more than one who has been going there for a long time. A child who has responsible competitions or performances is more than one who does not have them.

Flexibility is very important, not too rigid rules; on some day someone needs two hours, on another 15 minutes is enough for him.

Step 3. Protecting personal space

It is good for all family members to have personal space - not only for children, but also for mom and dad. When you have your own world where you can retire, and you know for sure that no one will break into it, this helps to preserve emotional resources and well-being.

If someone can come and taunt you at any moment - whether you are doing your homework, talking to a friend, or laying out your collection of your favorite cars - this creates a feeling of threat.

Then you want to protect your personal space.

This feeling of threat is common to all family members, but it becomes especially acute when the child enters adolescence.

If you have already fought Photo: Victoria_Art/pixabay.com

Step 1. Separate the participants

A fight is always an extreme point. But parents should understand that children fight and say unpleasant words to each other simply because they cannot express in another way that they feel bad. A fight is a signal that the child has some kind of internal trouble. And you need to deal with the cause, and not put out the fight as a symptom.

If a fight has already started and the parents see it, it is important to stop it and separate the participants into different rooms.

Step 2. Discuss what happened with everyone

When the participants calm down, discuss the incident with each of them. At the same time, it is important not to look for someone to blame: "Who started it first, why the fight happened. " It is important to state the fact - "you got into a fight" - and try to find ways to avoid this in the future.

" It is important to state the fact - "you got into a fight" - and try to find ways to avoid this in the future.

Prohibitive methods ("If you fight again, everyone will be left without ice cream") is ineffective.

Children may stop fighting and even get offended and unite against their parents. But avoiding conflicts in the future will not be learned.

Prohibitory measures and any actions of parents on emotions in this situation reflect only the state of parents - helplessness, impotence, irritation, fatigue.

How to teach a child to manage aggression

The child needs to explain the relationship between emotions and behavior. For example, one of the children, having lost in checkers, begins to scatter them, swing at his brother, swear, cry. It is important to accept his feelings, to give the right to them: “Yes, losing is really very difficult, unpleasant ... I even want to scatter everything and beat the opponent ...”

In the future, it will be important to teach the child to enjoy the process of the game itself (for example, from a coup), and not just from winning at the end. You can also teach your child to recognize irritation in advance: “You are already starting to get very angry ... Probably afraid to lose? Do you remember how you scattered all the checkers last time?”

You can also teach your child to recognize irritation in advance: “You are already starting to get very angry ... Probably afraid to lose? Do you remember how you scattered all the checkers last time?”

Even these words will greatly ease the experience of the baby. In the future, you can show him other ways of expressing irritation, resentment, anger.

All this can be used from preschool age, complicating the content of the conversation in the course of growing up and developing the child.

It is important to remember that the baby will not suddenly learn to control himself, you should be patient and help him on this difficult path.

In addition, it is important to understand the reason for a particular fight - maybe it was a busy day and the children were just tired, maybe an old grudge makes itself felt or something had to be urgently changed, but the child was not warned about this in advance and he feels deceived .

It is important to teach children to recognize their emotional state. To do this, you need to talk with the children, preferably the next day after the fight, when emotions calm down.

To do this, you need to talk with the children, preferably the next day after the fight, when emotions calm down.

Active listening should be used in conversation : for example, an adult describes what happened at the time of the fight, naming the child’s emotions (“You are tired, your brother said something offensive or at the wrong time, and you got angry”, “You are tired, brother grabbed your toy, and it seemed very unfair”), and listens to how the children comment on what was said.

It is important to have a calm dialogue, get to the bottom of the incident and call all emotions by their proper names. Keeping the conversation going, you need to figure out how you can act in similar situations without bringing the matter to a fight. For example: “If you are tired, you should not talk, but go to sleep”, “If you are annoyed, it is better to go to a separate room.”

Active listening involves the parent naming the feelings the children are experiencing (the children may not be able to recognize them all) as well as the feelings the parent is experiencing: "I get very upset when you fight. "

"

Unfortunately, many adults also do not know how to recognize their feelings and do not consider it necessary to sincerely share their own experiences with their children. Of course, children should not be devoted to all the details of personal problems.

However, if parents indicate that they are tired, not feeling well, a little upset, or, on the contrary, very happy, full of energy and strength, this will help children to be more conscious of their experiences and the feelings of another. Which in the future will help you better understand yourself, the reasons for your actions, act not under the influence of emotions and circumstances, but make informed decisions.

“What if we have the wrong children?” Photo: Victoria_Art/pixabay.com

You can talk to children once and there will never be fights again, never happens. New circumstances arise all the time, and until the children learn to control themselves and cope with them, it will take some time.

A separate problem is that parents whose children are fighting start to worry very much.

What will people say?

What if they have the wrong children?

What if they themselves are wrong parents and raised their children wrong?

In fact, even if children know how to listen to themselves and negotiate, they will be able to restrain themselves in 80% of cases. In the other 20% they will scream or fight. This does not mean that they hate each other, it means that they simply do not control their own aggression. And this must be learned.

Additional ways to develop self-control

Some children may benefit from engaging in sports to control aggression. It is important to choose the type of activity individually, based on the characteristics of the temperament, abilities, interests of the child. For some, team sports (football, volleyball, etc.) are more suitable, for others, contact martial arts, for others, classes aimed at relaxation (swimming, yoga).

Any organized physical activity is a good way to throw out negative emotions, learn to control yourself.

On the other hand, for some of the children, on the contrary, it is easier to calm down and relieve stress by engaging in creativity, work, leisurely walks, calm communication with loved ones.

In each case, the issue of additional classes is decided individually, and there is no single recipe (for example, “martial arts will help stop fights between children in the family”) for everyone.

The child beats the parents, the child beats the mother. Advice from a practicing psychologist

Hello, dear readers of the accessible psychology blog.

We keep talking about childish aggression.

We have already discussed the topics:

— Children's aggression from one to seven years old

— Why do children fight?

For a detailed analysis of this issue, see the video: "Children's aggression".

As you can see, we answered the question “Why and why?” in detail, and now we will deal with another burning question:

I want to note right away that we will talk about children up to 3-3.5 years old. It is during this period that the issue of child aggression is usually particularly acute. Why so, you can read in the topic about children's aggression.

The first incidents usually occur when a one-year-old child fights. In these situations, most often the child beats the mother. Because it is his mother who is the closest person to him during this period. Often this happens simply from overwhelming emotions of the baby. After all, a child in a year cannot yet assess whether he is hurting another. And therefore it happens that from overflowing emotions the child clings to the mother SO much that it hurts her to tears.

In such situations, one must understand that the child does not cause pain to the mother on purpose.

Or there may be another option: the child hits his parents in the face for joy, or he is just wondering how this happens.

Adult task in this case:

- Exact feedback. Many parents laugh when such a small child hits them. After all, often it doesn’t even hurt, but from the outside it looks funny (like a Pug on an Elephant). But with our fun, we show the child that we approve of his behavior. And why then be surprised if such "entertainment" is fixed later? It is very important to correctly show your emotions to the child. If a child hit his mother, hurt her, she should be upset, say about it in words that she usually says to a child when it hurts. After all, how else will he learn to understand the consequences of his actions?!

- Demonstration of an acceptable way of expressing emotions. We explain to the child that you can’t beat your mother, but you can hug like this, or stroke like this. It is very important not only to prohibit, but also to give an alternative, because the child still needs to somehow express his emotions.

We explain to the child that you can’t beat your mother, but you can hug like this, or stroke like this. It is very important not only to prohibit, but also to give an alternative, because the child still needs to somehow express his emotions.

It also happens that a child beats his parents as a protest.

After all, when a child begins to walk, a large number of prohibitions suddenly appear: “Don't go there, don't get in here, don't touch that,” etc. Of course, this causes a protest among the little one, but it is most interesting for him to climb on the table and the window sill. And here screams, fists and teeth come into play.

A child beats his mother, who forbids him something. How can this be avoided?

First, we need to think over the system of prohibitions. That is, think about what is really dangerous for the little one, and what can be rearranged, raised higher to remove the child from access. A large number of prohibitions causes proportionally greater aggression in the child. Why should we provoke the child ourselves? There should not be many prohibitions, but they must be precise, firm and unshakable. Then the child will be much calmer to respond to them. The prohibition system is a rather complicated issue, which we discussed in detail in the Secrets of Education program

A large number of prohibitions causes proportionally greater aggression in the child. Why should we provoke the child ourselves? There should not be many prohibitions, but they must be precise, firm and unshakable. Then the child will be much calmer to respond to them. The prohibition system is a rather complicated issue, which we discussed in detail in the Secrets of Education program

Secondly, you need to think about distractions. Sometimes it happens that even if there are not many prohibitions, the child still persistently tries to break them. We need to figure out how we can distract him, come up with an alternative. Well, for example, you have an active kid who likes to climb on the back or side of the sofa and jump from there to the seat. Of course, every time you have a heart attack, because. the child may roll onto the floor. And when you forbid it, the child starts to fight. Solution: Find something safe that's just as fun to jump on. It can be a sports mat or an old mattress, or special soft large pillows. As a result, the child is happy, the mother is calm.

As a result, the child is happy, the mother is calm.

How to respond if a child hits the mother?

Many parents admit that they do not know how to react in such a situation.

— if a child constantly fights with his parents, then it is quite possible to predict such behavior. You can intercept your hand during the swing and very strictly, but without anger, say that you can’t fight. In this case, eye contact is very important. Then you voice the child’s emotions (“I understand that you are upset”), explain the reason for the ban (“we have to go to bed now, otherwise we won’t be able to go for a walk in the evening and won’t see your friends”), give an alternative or “lure” (“ let’s go to bed soon, there you are already waiting for, probably, a dream about Luntik”). Repeat if necessary.

- I personally consider hitting a child back as an extreme measure. Sometimes it works, but very often it looks like this: mother and daughter are sitting.