Learning how to write alphabets

Learning How To Write Letters - Children Need 3 Key Skills

The steps to learning how to write letters for children is actually quite complex. The skill of handwriting requires many motor learning experiences prior to the actual act of writing letters. These experiences are not with a pencil either but with gross motor skills, fine motor skills, visual perceptual skills and cognitive skills.

The development of handwriting is a complex task that requires motor skills, cognitive skills and neuromotor skills. It is not always easy to identify exactly what piece of the “puzzle” is missing if a child is having difficulties with handwriting. The three skills needed to help children develop the skill of learning how to write letters are:

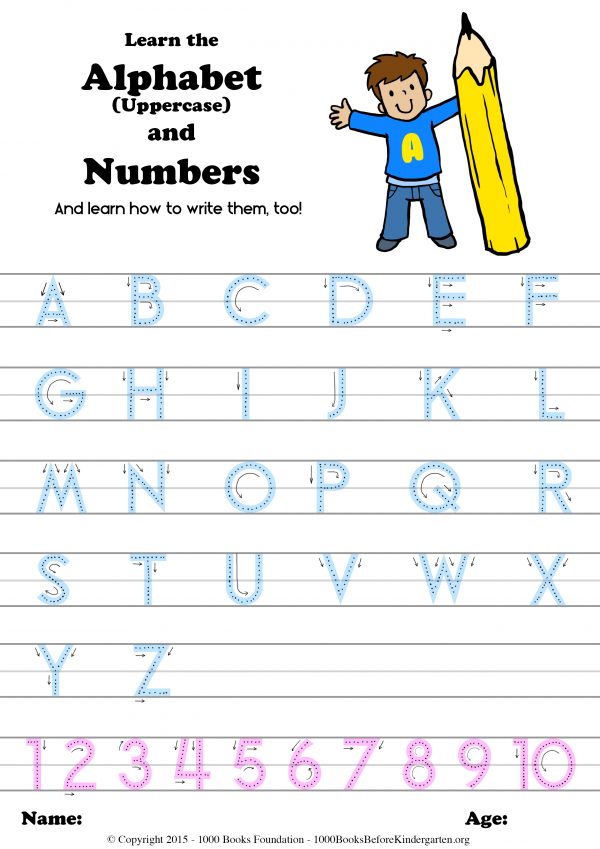

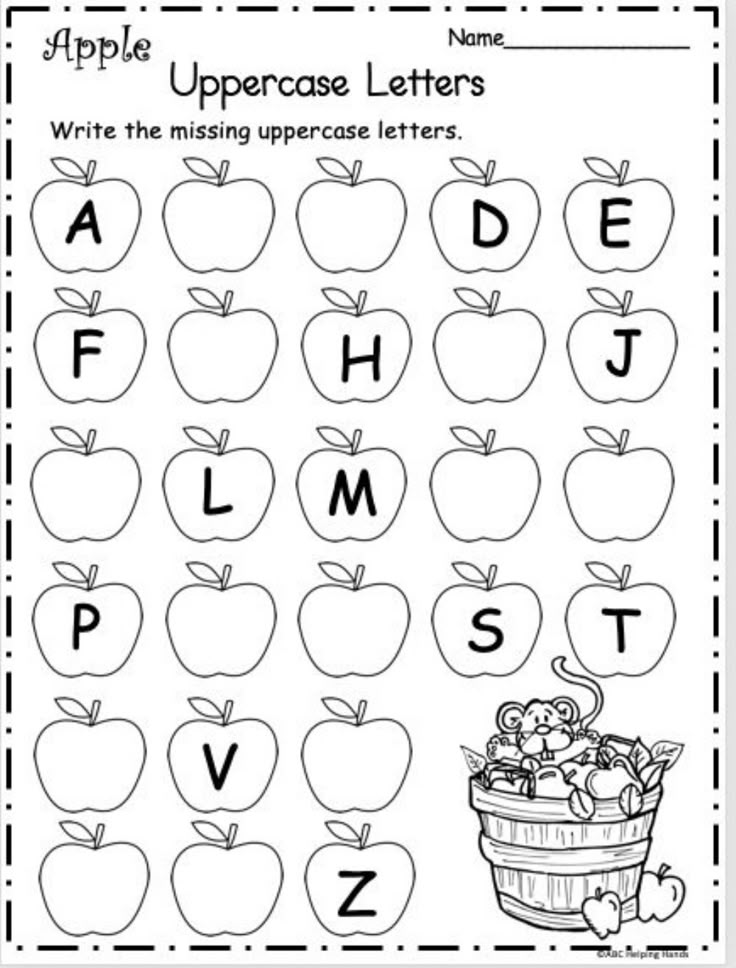

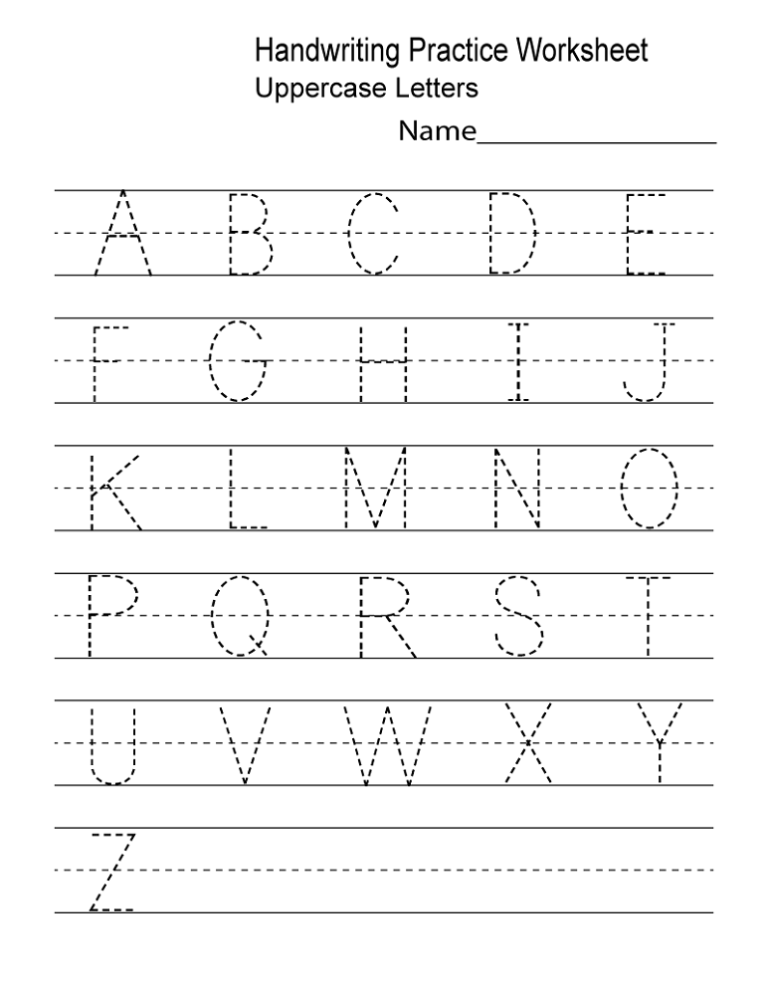

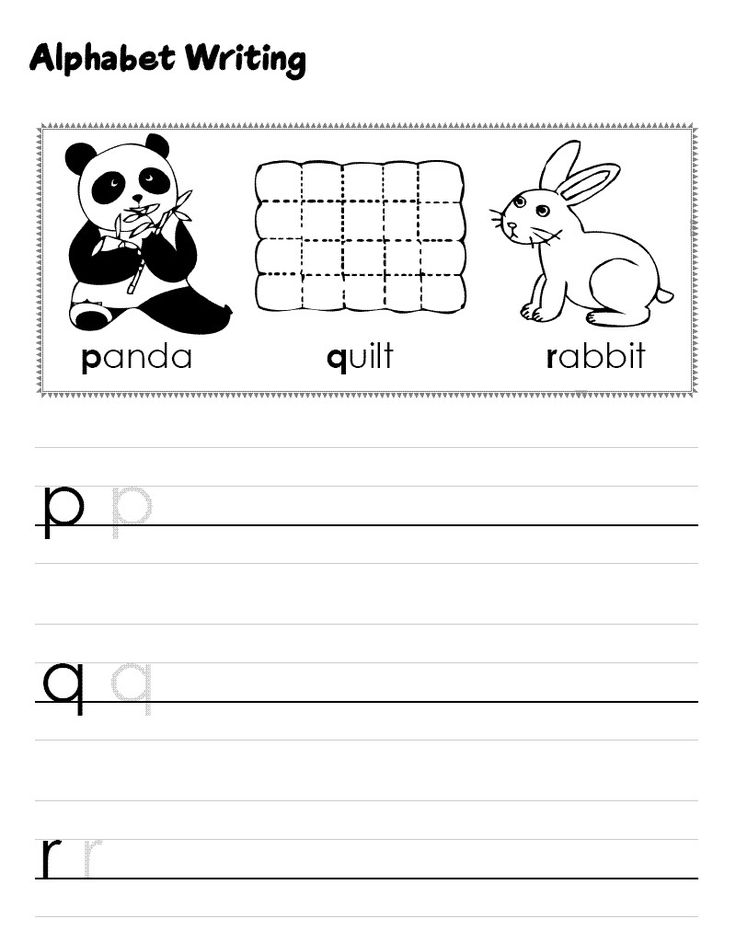

Complete visual representation of the letter

Can the child accurately identify the letters that you are practicing? Provide children with letter cards or alphabet charts for proper letter formation. An example of alphabet charts are Classroom Wall Cards and Alphabet Strips.

Another example for alphabet charts is Alphabet Wall Cards Handwriting Without Tears Style Font.

Read more about the four components of letter recognition.

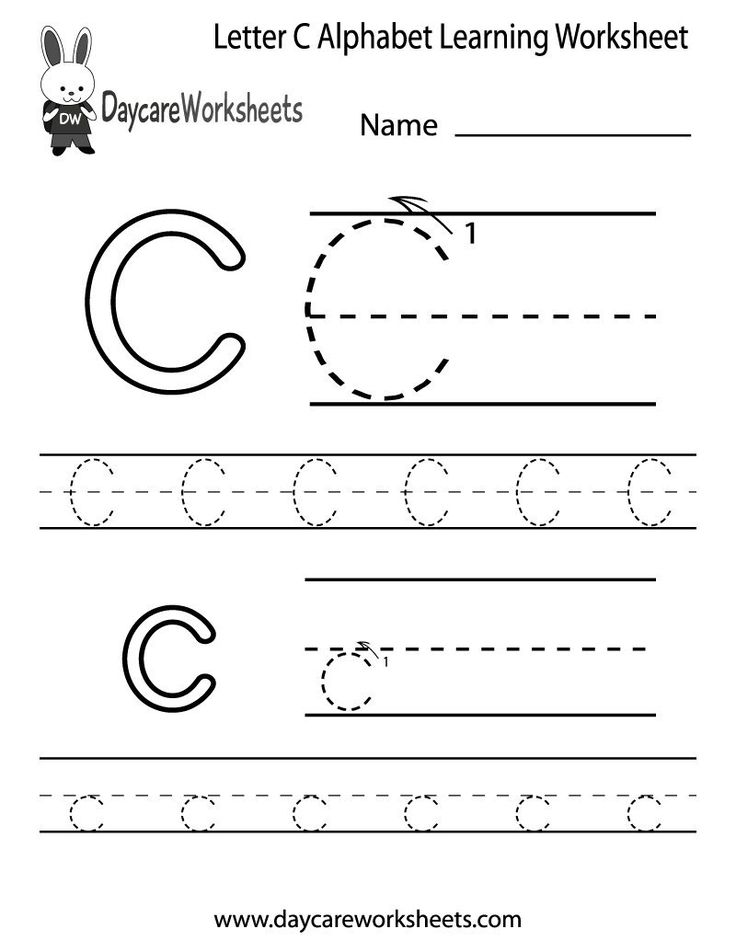

Recognition of the line segments that form the letter

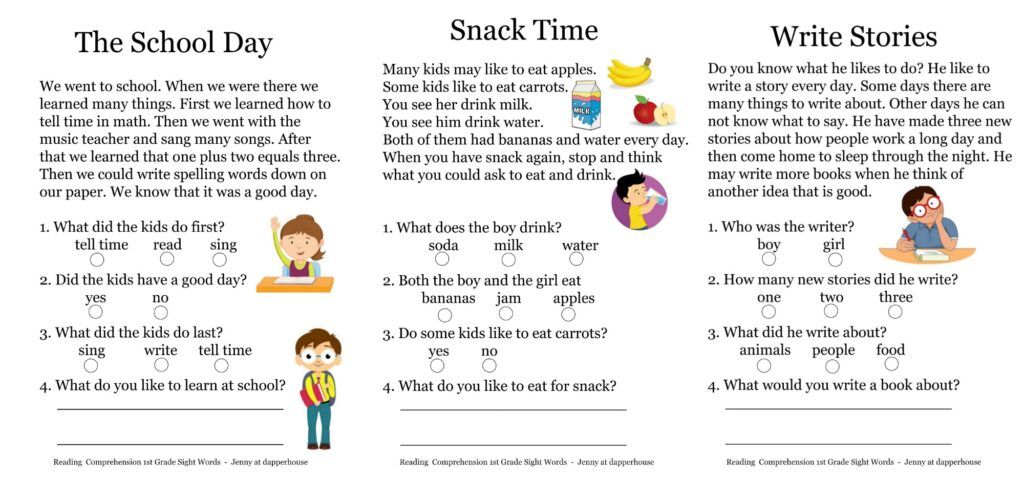

Can the child recognize horizontal, vertical and curved lines? This skill requires cognitive skills, visual memory and visual spatial skills. Many children today start writing letters at too early of an age resulting in poor habits. When children practice pre-writing skills before learning how to write letters, they may develop better handwriting skills.

If you are working with very young children (early preschool age) there are other skills that can be practiced that do not require a pencil. Read about 10 activities to get children ready for pre-writing skill here.

When children are learning how to write letters and ready to start practicing line segments, these resources may be helpful:

Prewriting Activity Pages includes 50 black and white pictures to trace and color. This is a “just right” activity for children who are learning to write, draw and color. Each picture has dotted lines for the child to trace to practice visual motor skills. Once completed, the child can paint or color the picture. Various prewriting practice strokes are included throughout the packet such as vertical lines, horizontal lines, diagonal lines, curves, circles, squares, loops, wavy lines and more! FIND OUT MORE.

This is a “just right” activity for children who are learning to write, draw and color. Each picture has dotted lines for the child to trace to practice visual motor skills. Once completed, the child can paint or color the picture. Various prewriting practice strokes are included throughout the packet such as vertical lines, horizontal lines, diagonal lines, curves, circles, squares, loops, wavy lines and more! FIND OUT MORE.

Fading Lines and Shapes includes worksheets that gradually increase in visual motor difficulty while decreasing visual input for line and shape formation. There are 18 worksheets for line formations ie horizontal, vertical, curves, waves, diagonals, spikes and combinations. There are 9 worksheets for shape formations ie circle, cross, square, rectangle, X, triangle, diamond, oval and heart. This download is great for push in therapy, therapy homework or consultation services in the classroom. FIND OUT MORE.

The Weekly and Daily Sign In Sheets for Early Writers provides a progression of pre-writing skills:

- vertical lines (2 years old)

- horizontal lines

- horizontal curved lines

- vertical curved lines

- circles

- plus sign

- squares

- diagonal lines

- X shape

- triangles (5 years+ years)

- Full name

The goal of the Weekly and Daily Sign In Sheets is to:

- infuse the day with pre-writing skills in the student’s natural environment

- prevent bad habits from developing when writing letters

- practice visual motor skills

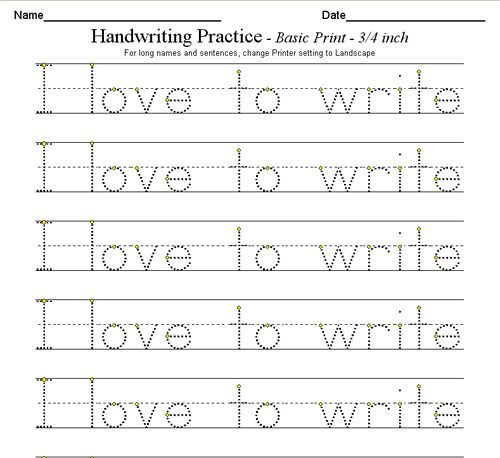

Ability to reproduce the sequence and direction of the line segments to form the letters

When it comes to learning how to write letters, can the child coordinate all the cognitive and motor skills needed to form letters? They need to be able to write lines in different directions and patterns with fluency and speed. For children who struggle with coordination skills, this can be where the task of handwriting becomes very difficult.

For children who struggle with coordination skills, this can be where the task of handwriting becomes very difficult.

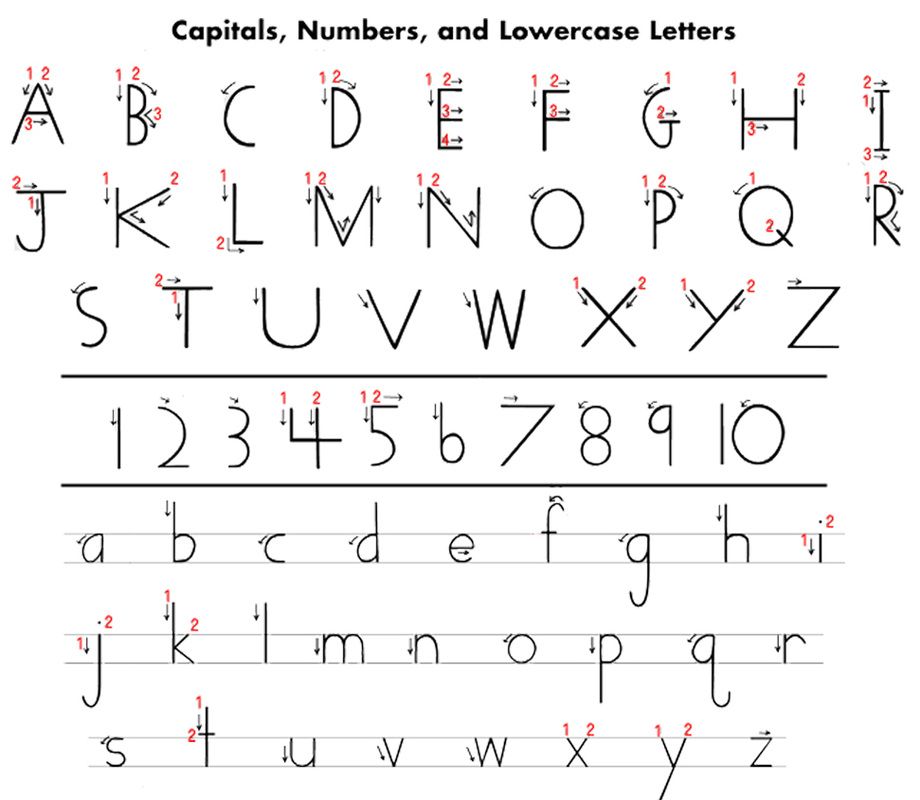

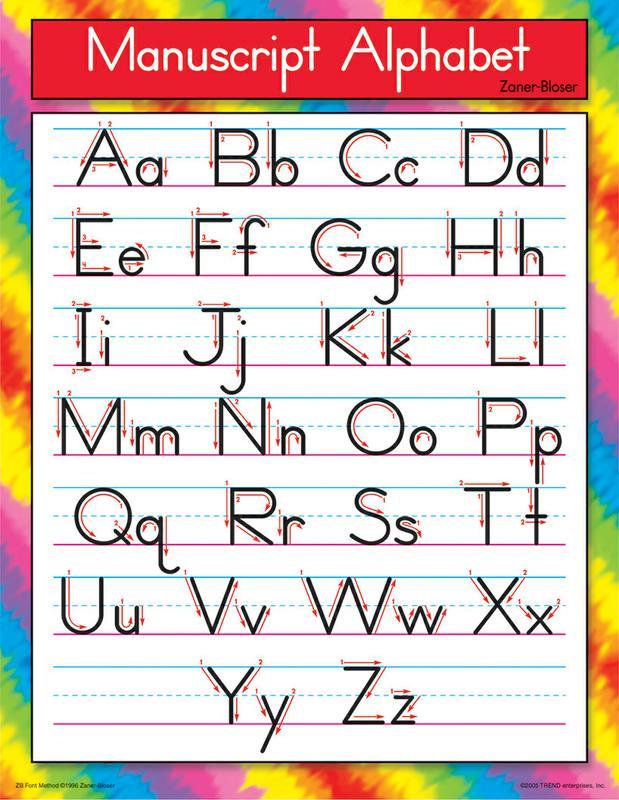

Handwriting Stations include the materials to create a handwriting station on a tri-fold or in a folder. The station includes proper letter formation for capital and lower case letters, correct posture, pencil grip, warm up exercises, letter reversals tips and self check sheet. In addition, there are 27 worksheets for the alphabet and number practice (Handwriting without Tears® style and Zaner-Bloser® style). This download is great for classroom use, therapy sessions or to send home with a student. FIND OUT MORE

Reference: Schickedanz JA (1999)Much More than the ABCs: The Early Stages of Reading and Writing.Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Want more freebies? Check out these Alphabet Bingo Printables.

Concerned about letter formation and reversals? Read more about Letter Reversals.

Learning to write the alphabet

Learning to write the alphabet is one of the first stages of writing literacy. For early modern English children, this meant first learning to read the letters of the alphabet (printed in black letter) from a hornbook.

For early modern English children, this meant first learning to read the letters of the alphabet (printed in black letter) from a hornbook.

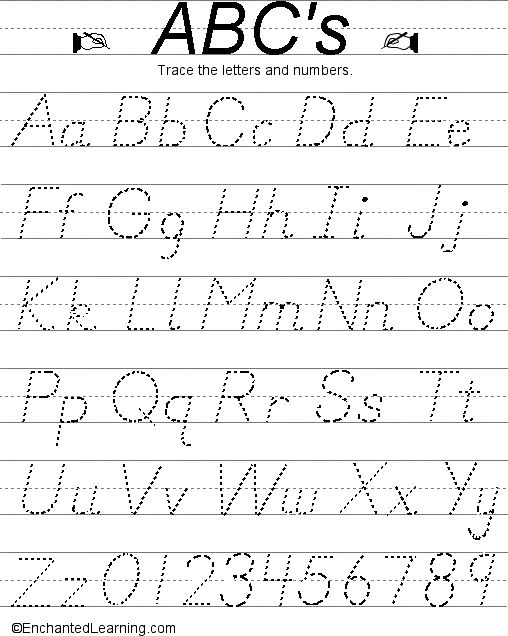

They then learned to write the letters of the alphabet in one or both of the two main handwritten scripts, secretary and italic. For this, they relied on manuscript or printed copybooks or exemplars, usually supplemented by instruction from a writing master at a writing school, a private tutor or family member, or usher in a grammar school. 1

Below are two plates from Jehan de Beau-Chesne’s and John Baildon’s A booke containing diuers sortes of hands, as well the English as French secretarie with the Italian, Roman, chancelry & court hands (London, 1602 [first ed. 1570]) (Folger STC 6450.2) that depict versions of secretary and italic hand:

“The secretarie Alphabete” from Jehan de Beau-Chesne and John Baildon, A booke containing diuers sortes of hands (London, 1602). This was the first English-language writing manual, first published in 1570.“Italique hande”

This was the first English-language writing manual, first published in 1570.“Italique hande”On both of these leaves, someone has tried to imitate the letter forms. In the top example, the brand new writer got through some of the minuscule and majuscule forms of the letter A (“a a a A A [upside down!] a a a”) before smudging out his or her work. Further progress is made on the “Italique hande” leaf, where the letters A through J (and perhaps an attempt at the letter K) are awkwardly and painstakingly formed underneath the exemplar. 2

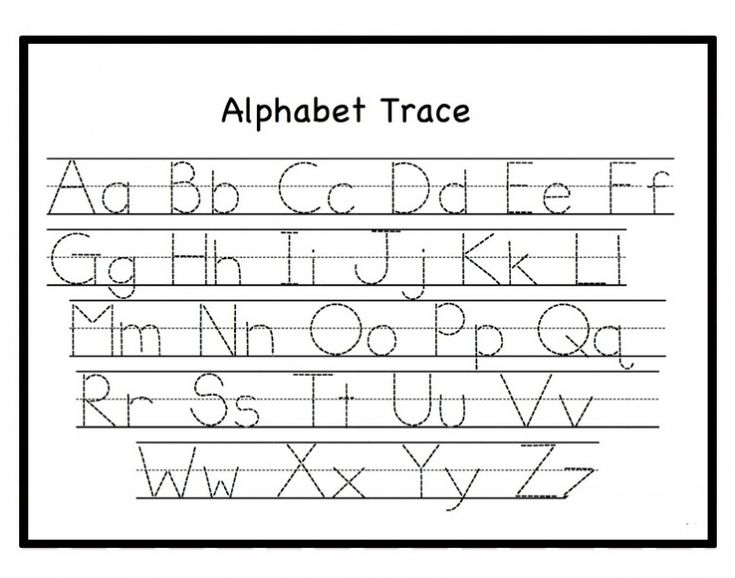

Children learned their letters by repeatedly tracing and copying strokes, letters, alphabets, pangrams (sentences that contain all the letters of the alphabet), and aphorisms. Beau-Chesne’s copybook was not the only one to contain the verse instructions, “Rules made by E.B. for children to write by,” that describe the ideal quill, ink, and posture for a child’s first experiences with writing. The instructions even advise on how the teacher should prepare the paper:

… Scholler to learne, it may do you pleasure,

To rule him two lines iust of a measure:

Those two lines betweene to write very iust,

Not aboue or below write that he must:

The same to be done is best with blacke lead,

Which written betweene, is cleansed with bread.

Your pen from your booke, but seldome remoue,

To follow strange hand with drie pen first proue: (copied from Folger STC 6450.2)

That is, use a graphite pencil to rule a piece of paper with sets of double lines for the child to write between. Then write some exemplar letters for the child to copy. He or she can trace them with an inkless quill in the first instance, and then proceed to use ink. The pencil lines can be erased with bread.

The result might be something like below, in which one Stephen Poynting, possibly a student at the Free School in Gloucester, practices a pangram, “Job a Righteous man of uz waxed poor Quickly” (i/j and u/v counting as single graphs). He writes it twenty-one times, and his spacing between words grows larger and larger so that he can no longer fit the last word of the sentence (he appears to be writing one word of the sentence at a time, in columnar format). If you look closely at the piece of paper, you can see that it is blind-ruled; that is, guidelines have been made with an inkless quill to help him write in a straight line.

In two competing pamphlets printed within weeks of each other in 1591, the early writing masters William Panke and Peter Bales provide detailed instructions for learning to write the letters of the alphabets in terms of breaks (the individual strokes that make up each letter) and joins (the strokes required to connect letters to each other if one is writing in secretary hand). 3 Breaking and joining instruction disappeared from copybooks in the first half of the seventeenth century, but was revived by Edward Cocker in the 1650s.

The example below shows how one Thomas Robinson, in 1698, used Cocker’s plate of “The Breakes of sett Secretary Letters” as a worksheet, completing the unfinished letters in ink, and making it up to the letter K in his imitation of the sample alphabet at the bottom of the leaf.

Edward Cocker, The tutor to writing ad arithmetick (London, 1664).The number of surviving copybooks from the Elizabethan and Jacobean period is tiny, with scholars assuming that they were genres that were either “used to death” or discarded once they were no longer needed. Most surviving examples of alphabet practice appear on blank spaces in printed and manuscript books and are usually not noted in catalog records. An advanced search in Hamnet for “alphabet” under “All notes” led to some good examples of what the very earliest attempts at an alphabet look like. 4

Most surviving examples of alphabet practice appear on blank spaces in printed and manuscript books and are usually not noted in catalog records. An advanced search in Hamnet for “alphabet” under “All notes” led to some good examples of what the very earliest attempts at an alphabet look like. 4

This notebook from a barrister riding on the Midland circuit in 1610 includes alphabet practice by a member of the Jeffreys family of Acton, Denbighshire, ca. 1650-ca. 1660, on three separate leaves (Folger MS V.a.489). All examples are minuscule secretary letters, except for the initial majuscule A.

Thomas Blakesley’s secretary alphabet, copied in 1613, is slightly more practiced than the previous example. He practices in a heavily annotated copy of Girolamo Ruscelli’s The secretes of the reuerende Maister Alexis of Piemount. Containyng excellente remedies against diuers diseases, woundes, and other accidents, with the manner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, diynges, colours, fusions and meltynges. … Translated out of Frenche into Englishe, by Wyllyam Warde (London, 1558) (Folger STC 293 copy 2). It is possible that the alphabet of minuscule and majuscule secretary letters was copied and spaced so that a younger learner could practice in between the lines.

… Translated out of Frenche into Englishe, by Wyllyam Warde (London, 1558) (Folger STC 293 copy 2). It is possible that the alphabet of minuscule and majuscule secretary letters was copied and spaced so that a younger learner could practice in between the lines.

Jeremiah Milles has added his alphabets and practice sentences to the backs of the front and rear covers and the endleaves of William Gouge’s Panoplia tou Theou. The vvhole-armor of God or The spirituall furniture which God hath prouided to keepe safe euery Christian souldier from all the assaults of Satan. First preached, and now published for the good of all such as well vse itt (Folger STC 12122 copy 2). His four attempts at the alphabet are either incomplete, or, as in the second example, missing the letter “p.” This causes problems for him in the fourth image, his transcription of Psalm 124 from the King James Bible, where he clearly thinks that the letter “q” is a “p”: see the words “up” (“uq”) and “proud” (“qroud”), for example. And in the third image, Milles’ transcription of the opening lines from John Fell’s The life of the most learned, reverend and pious Dr. H. Hammond (London, 1661), he somewhat corrects his initial confusion, although he still writes “attempted” as “attemqted.”

And in the third image, Milles’ transcription of the opening lines from John Fell’s The life of the most learned, reverend and pious Dr. H. Hammond (London, 1661), he somewhat corrects his initial confusion, although he still writes “attempted” as “attemqted.”

Another alphabet appears in a Folger copy of the 1605 edition of Sir Philip Sidney’s The Countesse of Pembrokes Arcadia (London, 1605) (Folger STC 22543 copy 4), but in this instance it is acting as a key to a rather unsophisticated cipher.

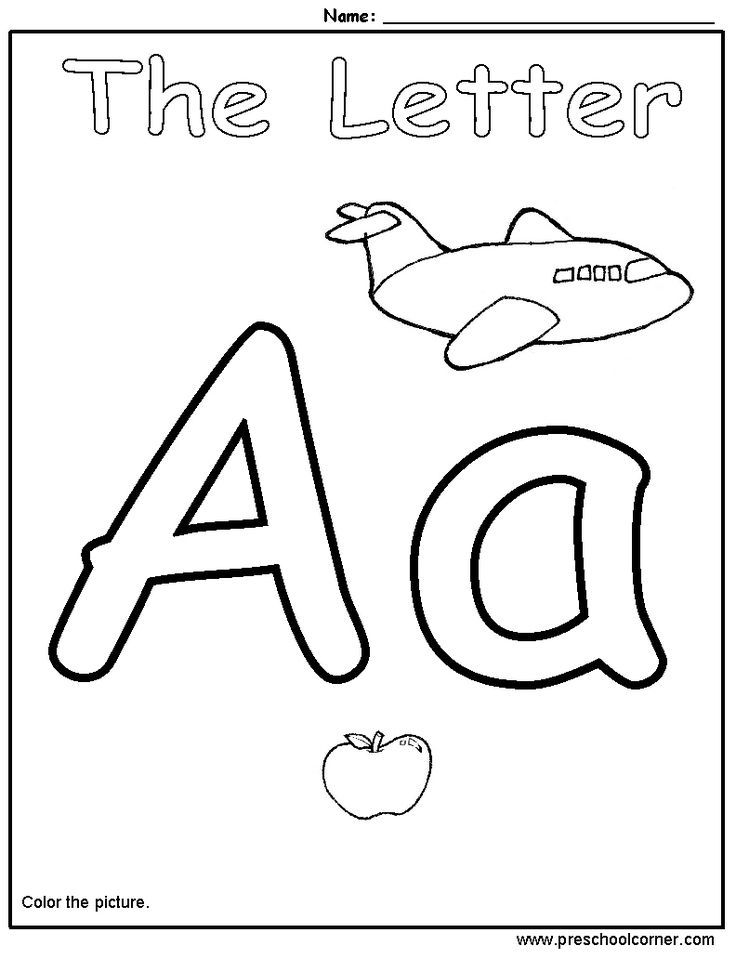

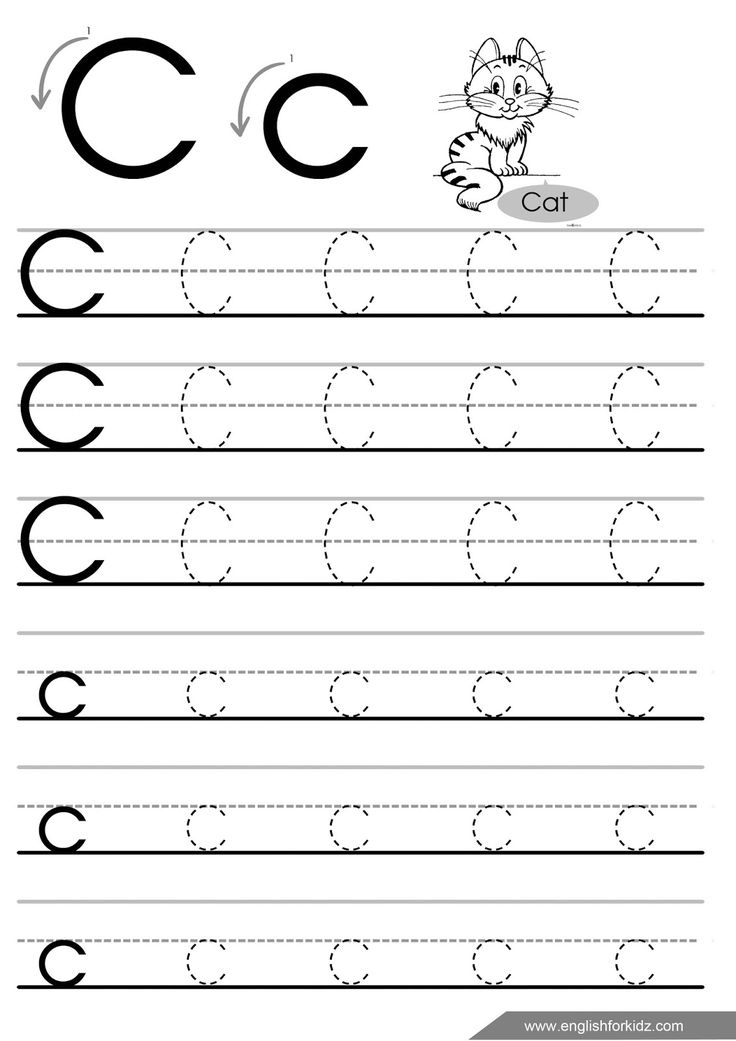

For any of you who have taught young children to write, now is the moment to acknowledge how little has changed in handwriting instruction in the past four hundred years (well, except that early modern children had the added challenges of having to learn to cut a quill nib and make iron gall ink). Worksheets from the Zaner-Bloser handwriting program illustrate the order in which the strokes are made and how the letters are joined together, and provide top, bottom, and middle guide lines. Modern handwriting programs such as Zaner-Bloser, Handwriting without Tears, and the Peterson Directed Method, encourage tracing letters before forming them freestyle, just like “Rules made by E.B. for children to write by” from 1570. 5

Modern handwriting programs such as Zaner-Bloser, Handwriting without Tears, and the Peterson Directed Method, encourage tracing letters before forming them freestyle, just like “Rules made by E.B. for children to write by” from 1570. 5

I happen to live with a four year old who is just learning to write her name and the alphabet. Just like Elizabethan children, she had to learn to grip her pencil correctly, in the “dynamic tripod grasp,” a new-fangled phrase for the second hold on the left, below.

“How you ought to hold your penne”I created double-ruled guidelines for her and an exemplar alphabet. She gamely copied the letters below, after tracing my lightly-written A and B. The results are one of those moments when the early modern and modern worlds seem to collide.

A 4-year-old’s efforts to copy the alphabet from models written by her mother.

- See Herbert C. Schulz, “The Teaching of Handwriting in Tudor and Stuart Times,” The Huntington Library Quarterly (4), August 1943: 381-425.

- By the way, the aphorism on this leaf is from Cicero.

- Simran Thadani’s recently defended PhD dissertation, Penmanship in Print: English Copy-Books and their Makers, 1570-1763 (University of Pennsylvania, 2013), provides an account of the battle for authority between these two writing masters

- I’m sure there are many other instances that haven’t yet been recorded, and that if one searched all the examples of “pen trials” under “All notes,” other examples of letter-formation practice would be revealed.

- Despite the fact that the Common Core Standards no longer require elementary school students in the U.S. to learn cursive handwriting, many states are still opting to include it in the curriculum, and research highlights the many benefits of learning to write (in both print and cursive hands), in terms of cognitive development, motor skills, and reading comprehension. For a good general overview of the debate, see here and here, as well as the recent New York Times debate, “Is Cursive Dead?”

Learning to write block letters of the Russian alphabet.

Trainer

Trainer Electronic library

Raising children, today's parents educate the future history of our country, and hence the history of the world.

- A.S. Makarenko

Learning to write block letters of the Russian alphabet. Trainer

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- Yo

- F

- W

- and

- Y

- K

- L

- M

- H

- O

- P

- R

- C

- T

- W

- F

- X

- C

- H

- W

- W

- b

- S

- b

- E

- Yu

- I

- Tasks

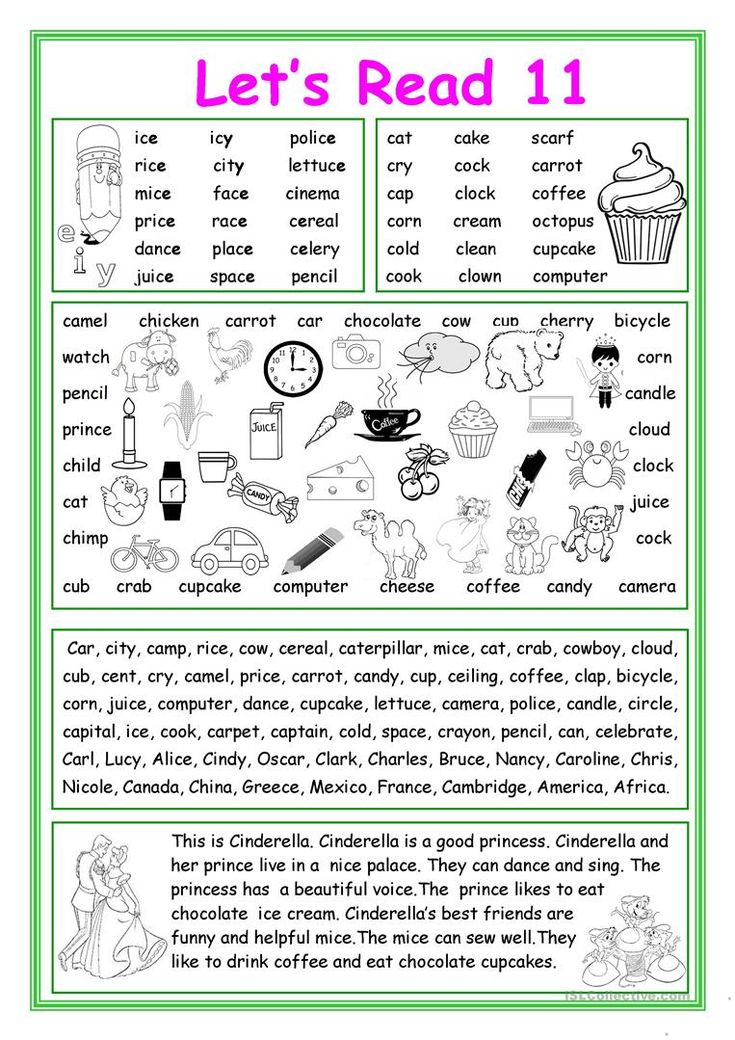

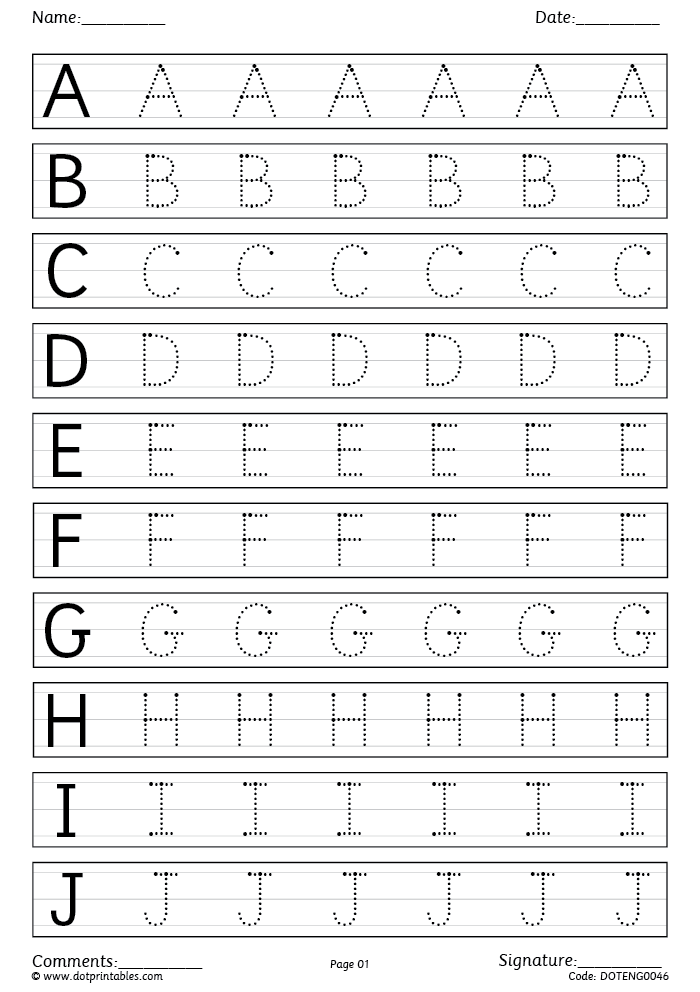

This section contains a simulator that teaches preschoolers 5-6 years old how to write the correct block letters of the Russian alphabet. The simulator consists of a collection of developing children's recipes, arranged in alphabetical order on colored tabs.

Red tabs contain copybooks for studying vowels, blue tabs for studying consonants, gray tabs for studying separating marks. The green tab contains developmental tasks and exercises to consolidate and practice the skills of writing in block letters.

Printing is part of learning to read and write early. This lesson develops attention, fine motor skills, graphic skills, promotes better memorization of the alphabet and improves literacy.

By completing developmental tasks and exercises, the child will get acquainted with block letters, learn how to write them, and also learn the Russian alphabet.

You can print as many copybooks as you need to repeatedly practice writing letters, reinforce your skills, and get a successful learning outcome.

Here various methods of teaching writing in block letters are proposed, which allows you to individually select the most suitable option for your child or put into practice all the proposed methods, making the learning process more interesting and varied for a preschooler.

Tips for working with spelling:

- Let's learn the vowels first. They are simpler and easier to pronounce and remember, at this stage of learning there are no problems even for children with speech disorders. Letters denoting the same vowel sound are recommended to be studied in pairs A - I, O - E, U - Yu, E - E, Y - I.

- After vowels, we study consonants. The sequence of study does not matter. As a rule, the letter P and other letters, the pronunciation of which is still difficult for the baby, are studied at the end. It is not recommended to study paired consonants in a row (B - P, G - K, D - T, Z - C, V - F, F - W) - it is difficult for a child at this age not to confuse them by ear.

- There are different approaches to the order of learning the letters, so you can use another, in your opinion, the most acceptable variant of the sequence of letters.

- Practice with your child for no more than 15 to 20 minutes.

- When completing tasks, the preschooler should hold the pen or pencil correctly, without straining the fingers too much.

- It is very important to properly organize the child's workplace: be sure to pay attention to whether it is comfortable for the child to sit at the table, and also where the light source is located. For right-handers, the lamp should be on the left side, and for left-handers, on the right.

- Don't forget to praise your child, even if he doesn't do well on tasks. From classes, a preschooler should receive only positive emotions. This is a prerequisite for further successful learning.

- Remember that learning should be in the form of an exciting game. In no case should a child be forced to fill out prescriptions - this can consolidate an aversion to learning to read and write for many years.

* 9 methods were used to create the simulator0119 VG Dmitrieva , O.S. Zhukova , M.O. Georgieva , M.P. Tumanovskaya .

- Views: 553797

Children speak

| "Mom, will you wake me up when I've had enough sleep?" - Vika, 4 years old |

New

- Lego speech games

- Neurologopedic prescriptions.