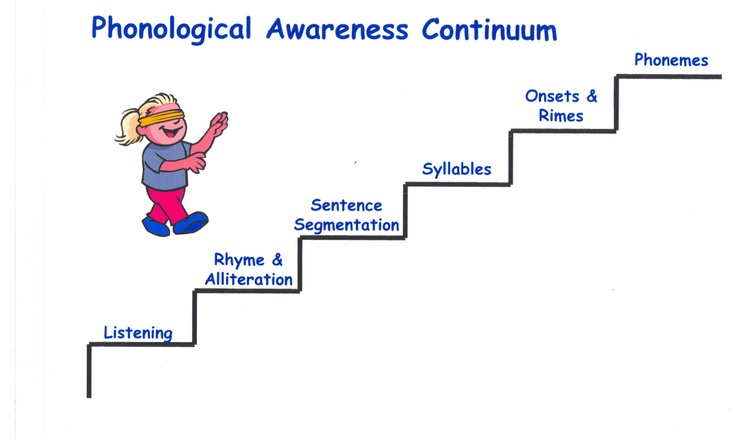

Level of phonological awareness

Phonemic Awareness | Phonological Awareness :: Read Naturally, Inc.

What Is Phonemic Awareness?

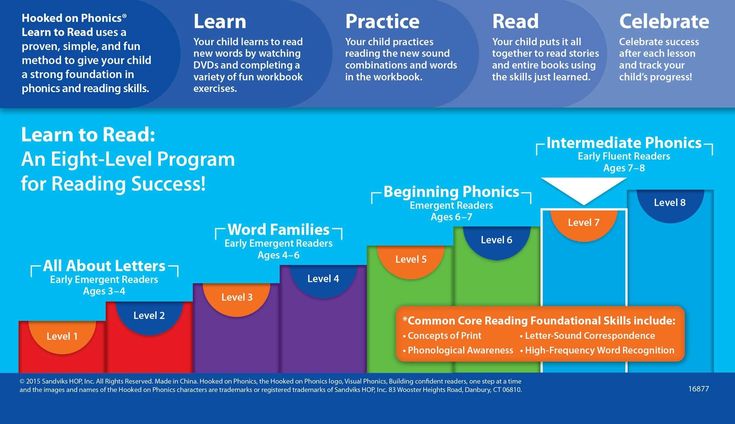

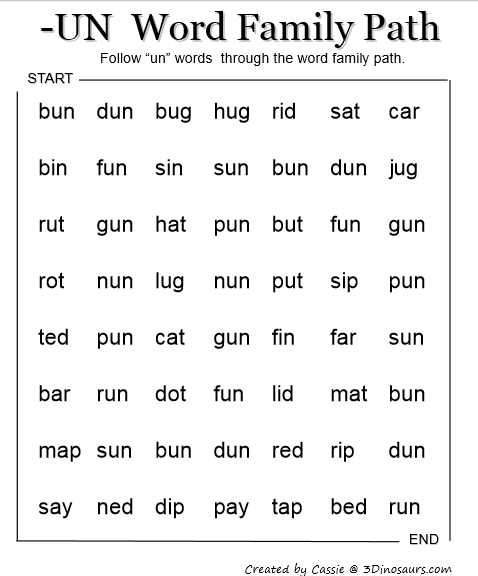

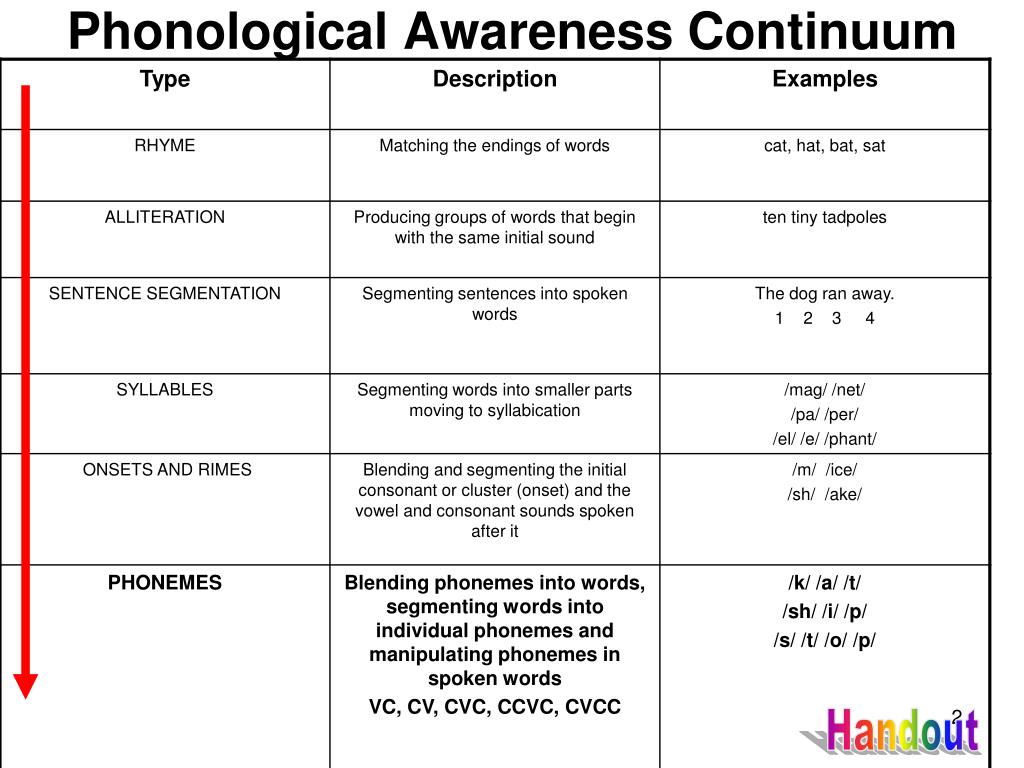

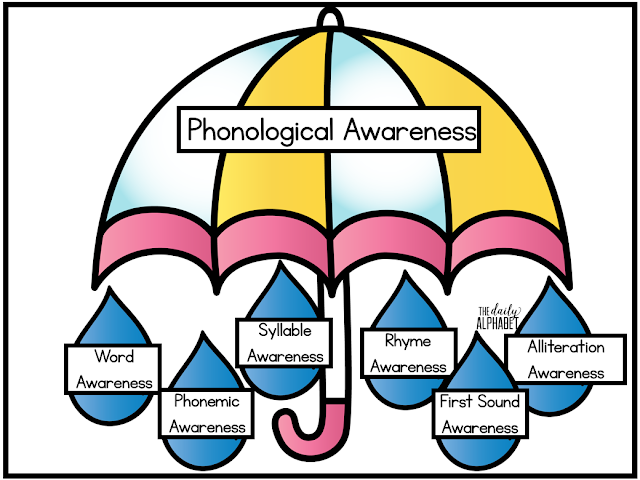

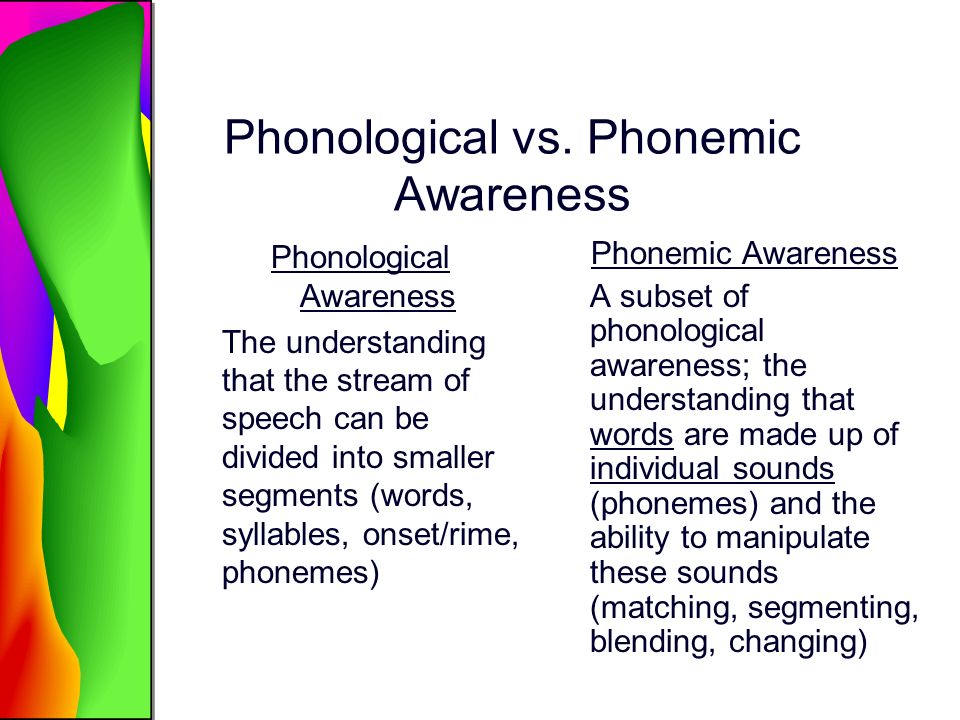

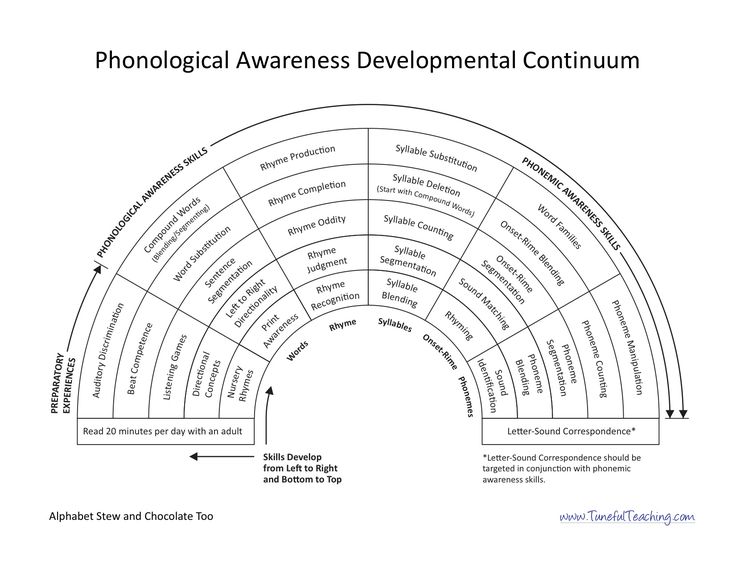

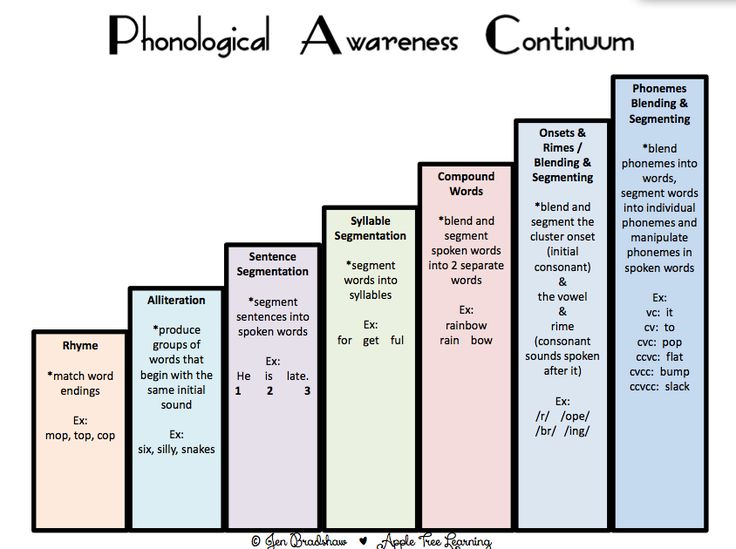

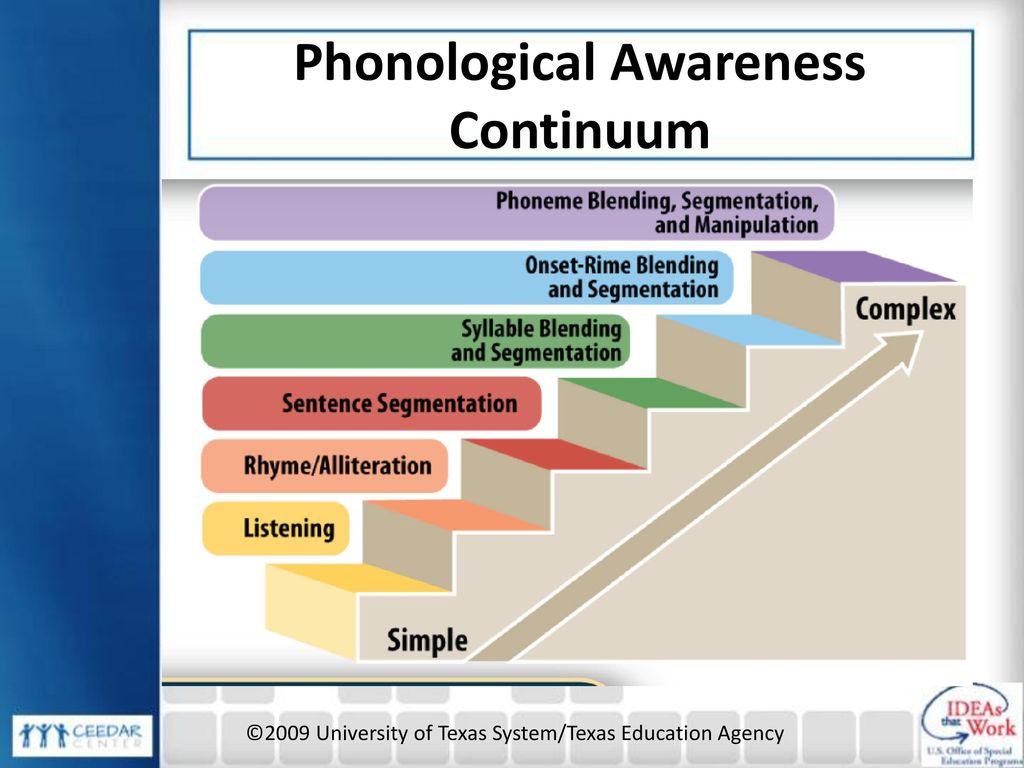

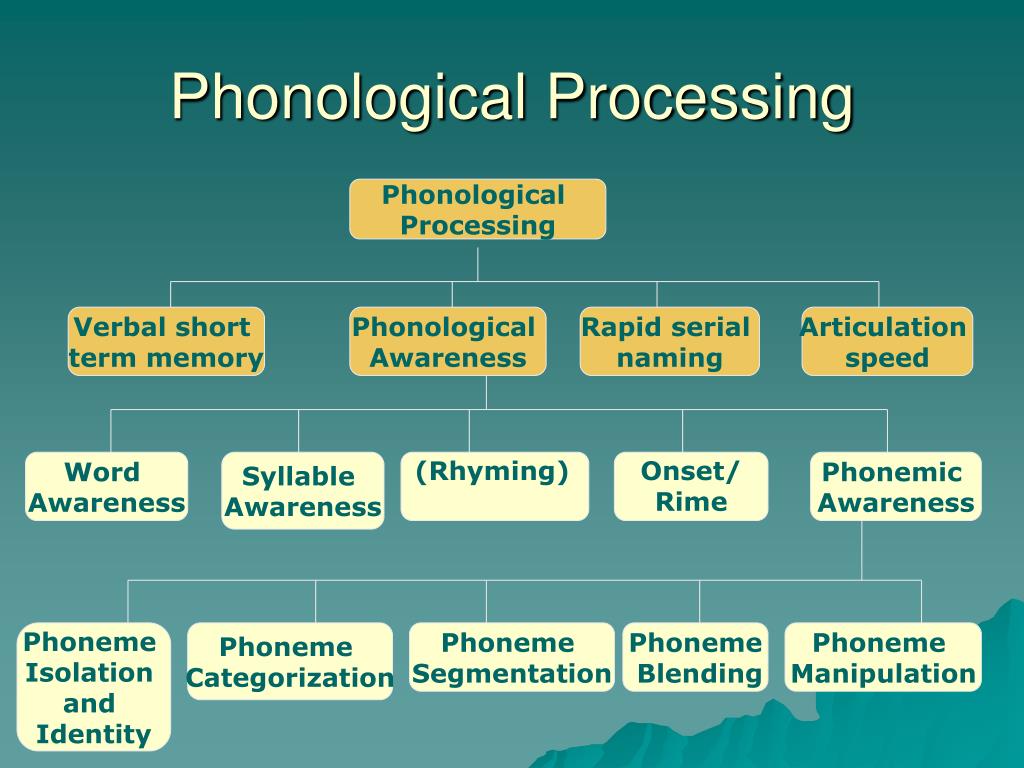

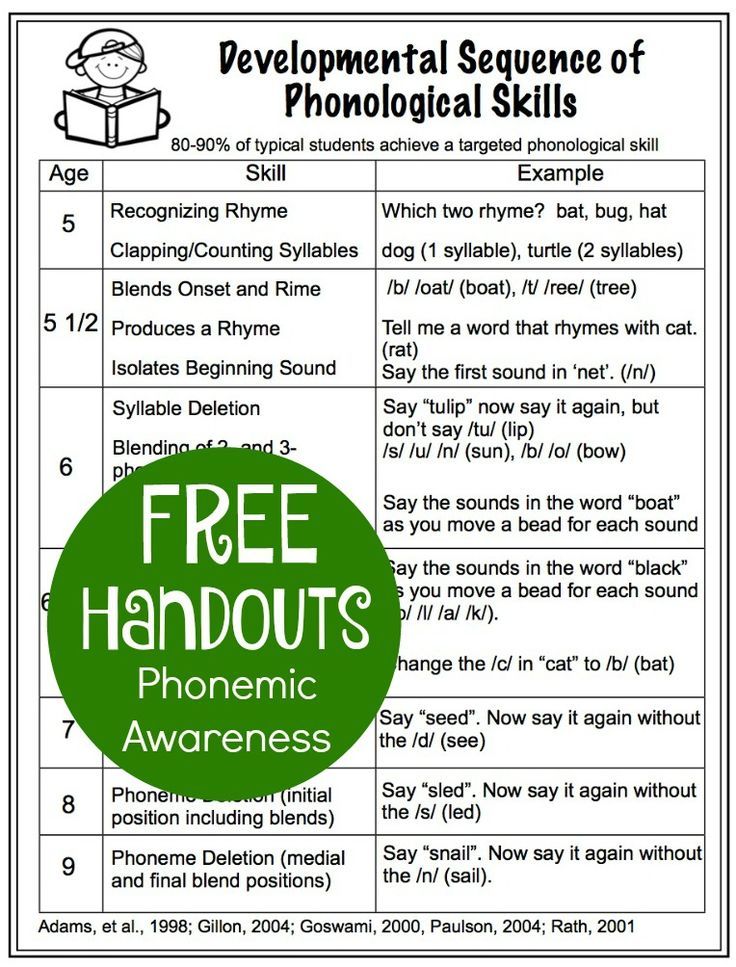

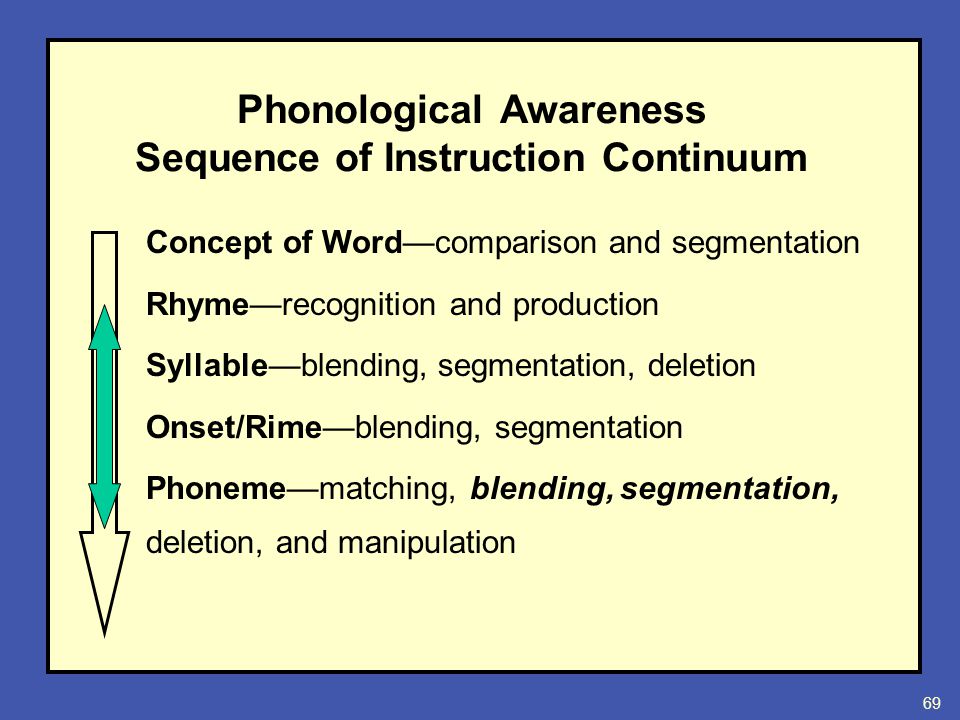

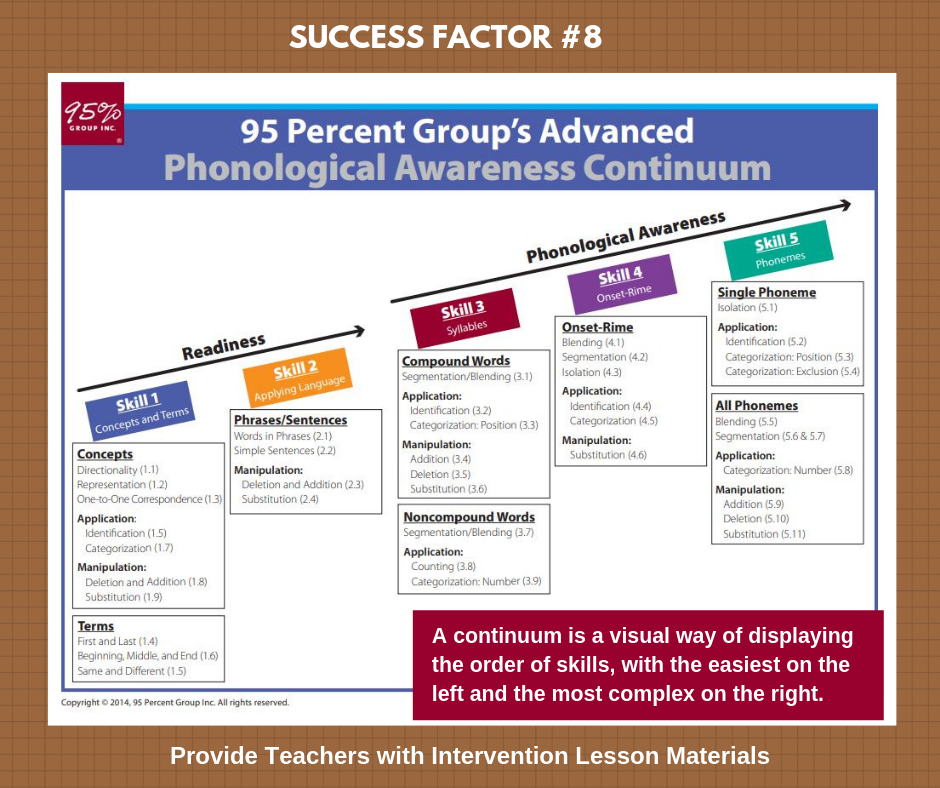

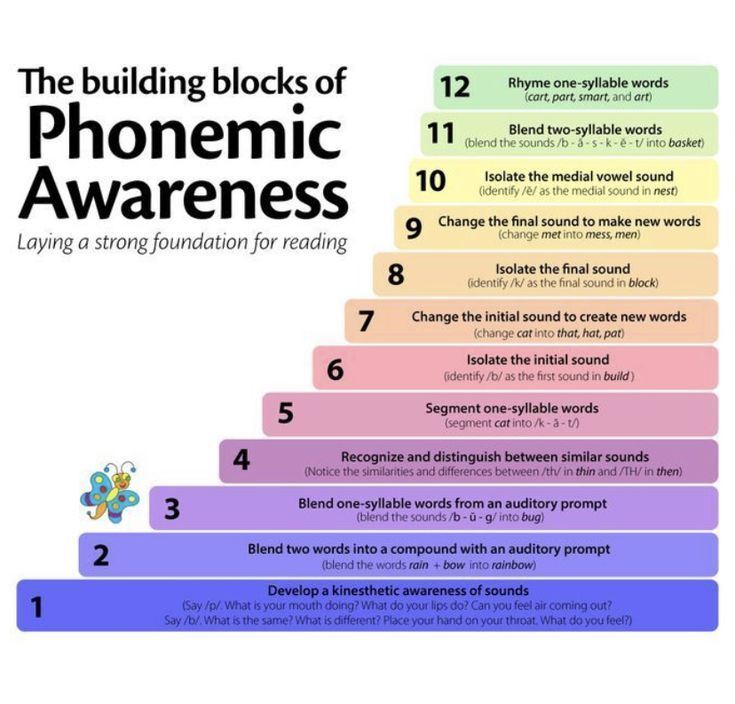

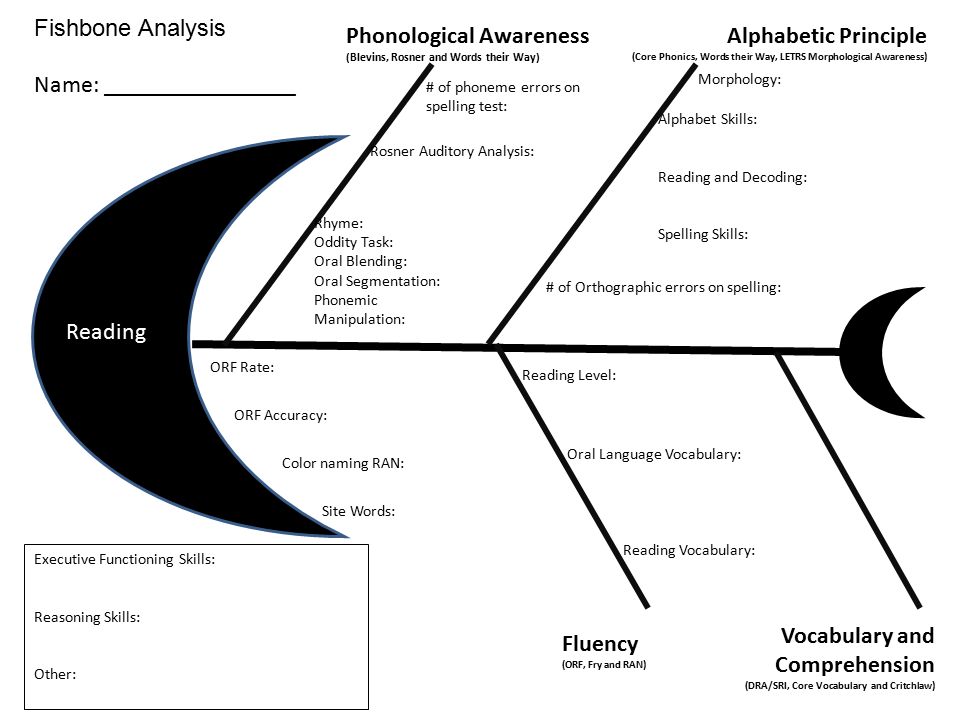

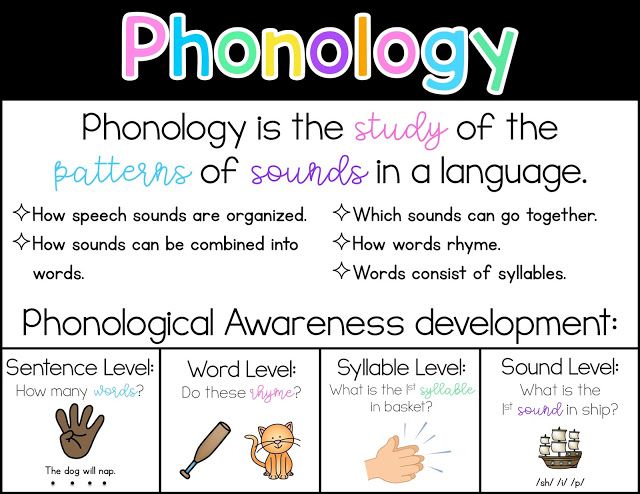

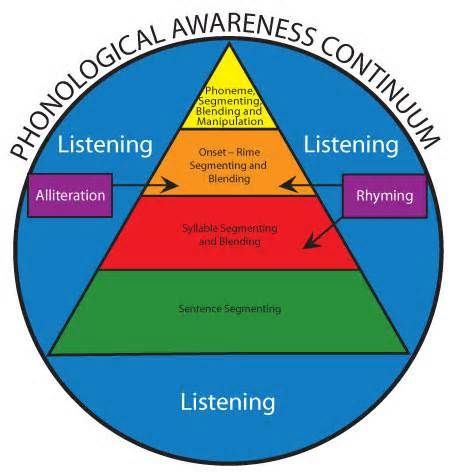

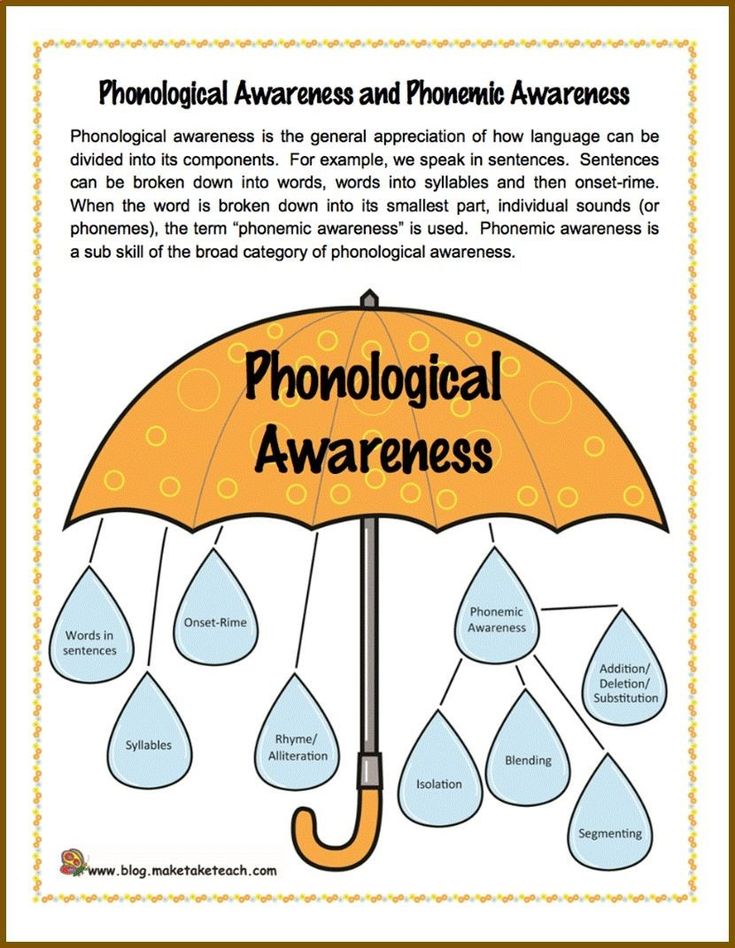

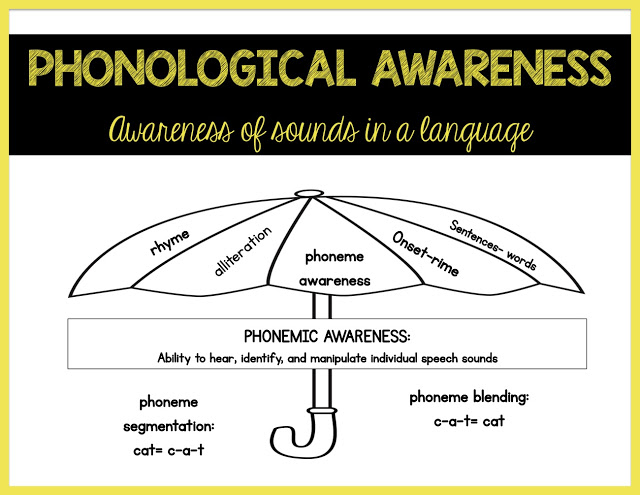

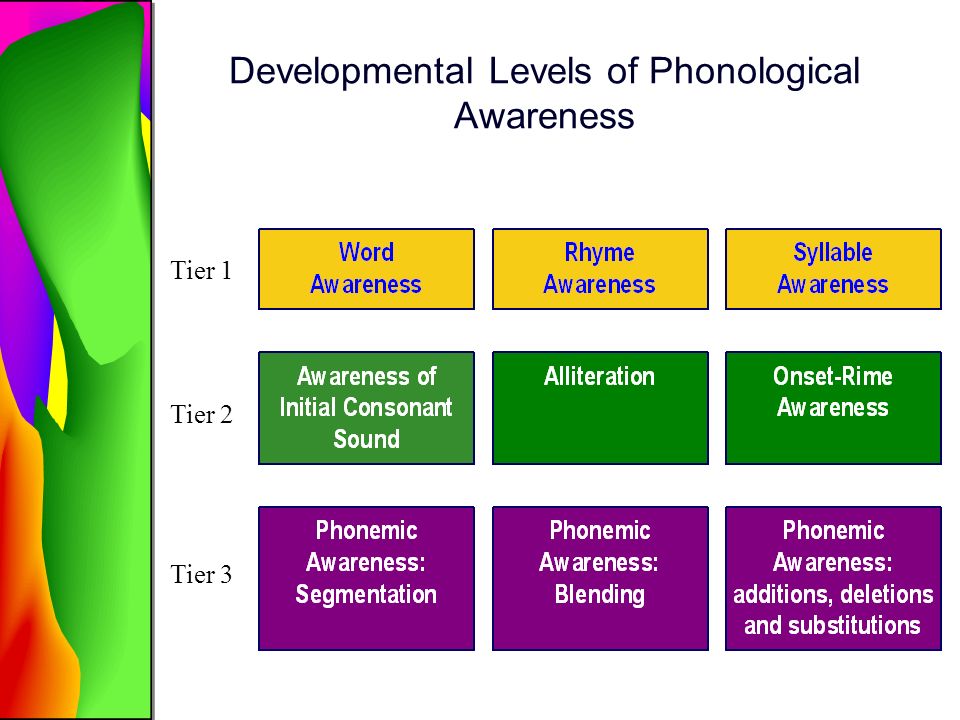

Phonological awareness is an umbrella term that includes four developmental levels:

- Word awareness

- Syllable awareness

- Onset-rime awareness

- Phonemic awareness

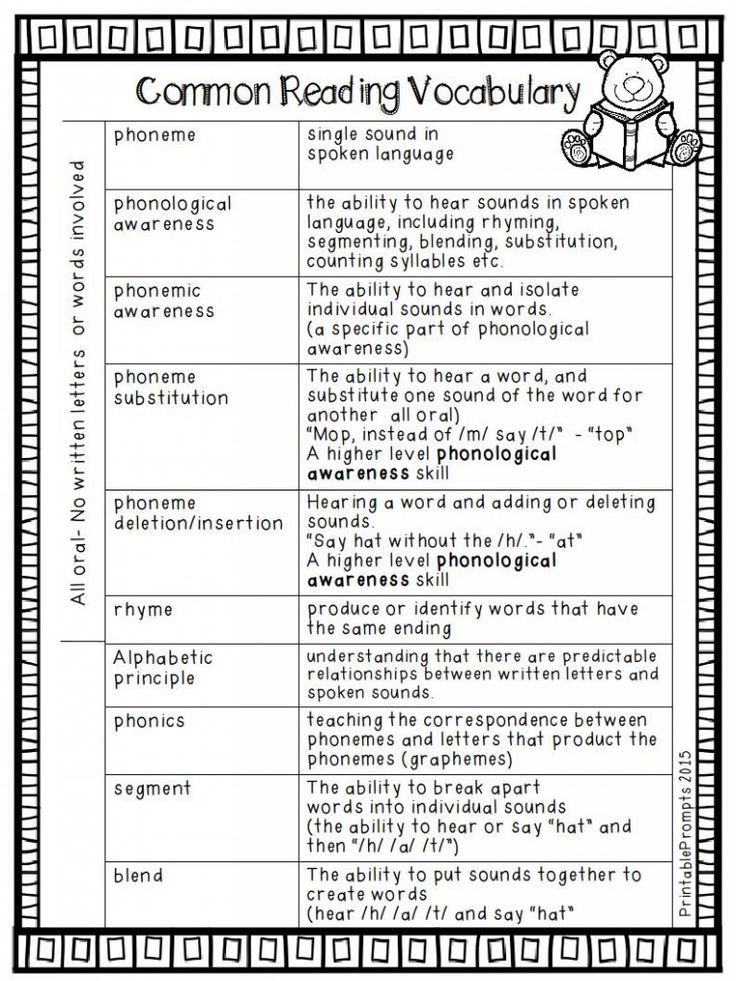

Phonemic awareness is the understanding that spoken language words can be broken into individual phonemes—the smallest unit of spoken language.

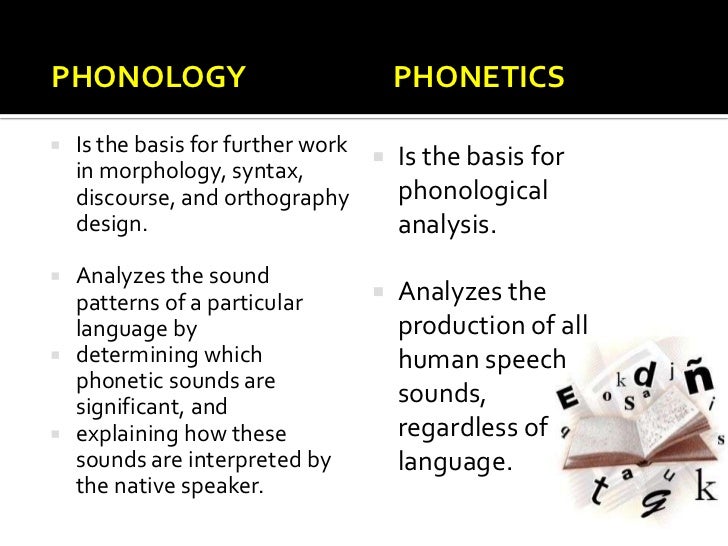

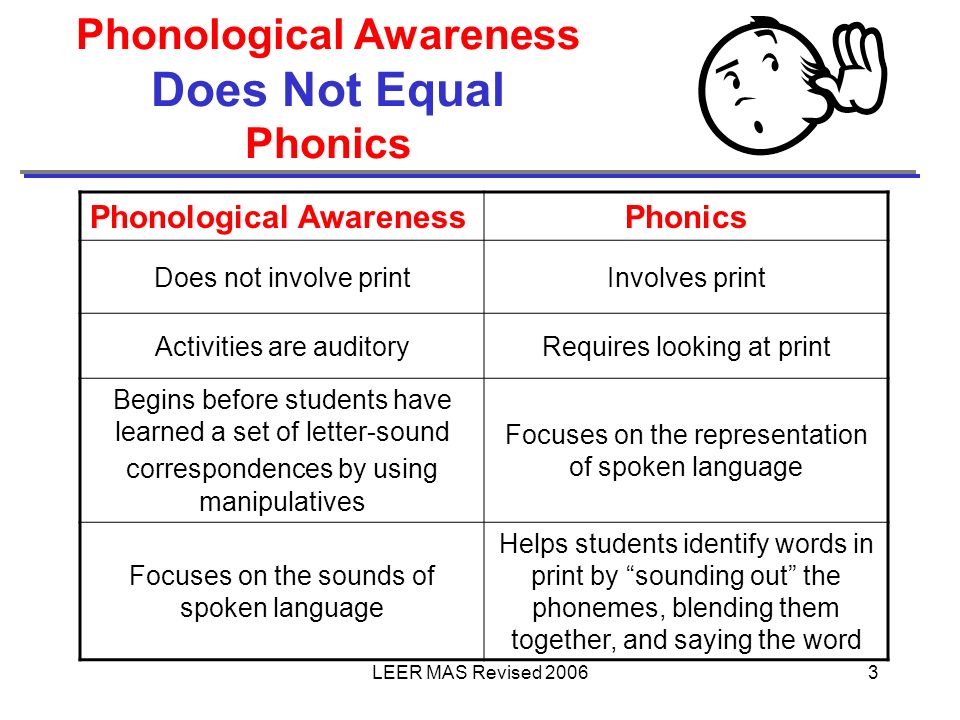

Phonemic awareness is not the same as phonics—phonemic awareness focuses on the individual sounds in spoken language. As students begin to transition to phonics, they learn the relationship between a phoneme (sound) and grapheme (the letter(s) that represent the sound) in written language.

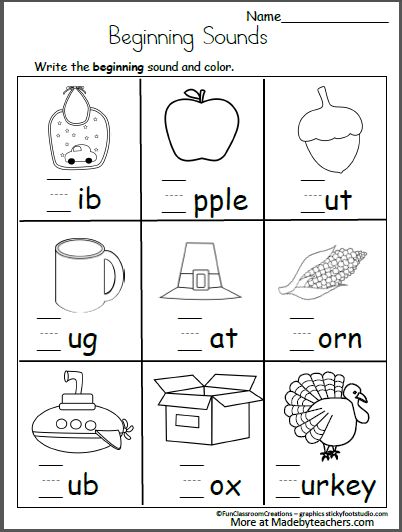

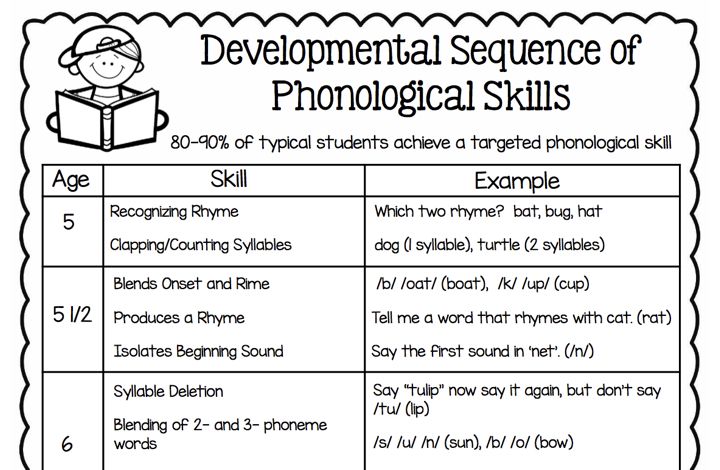

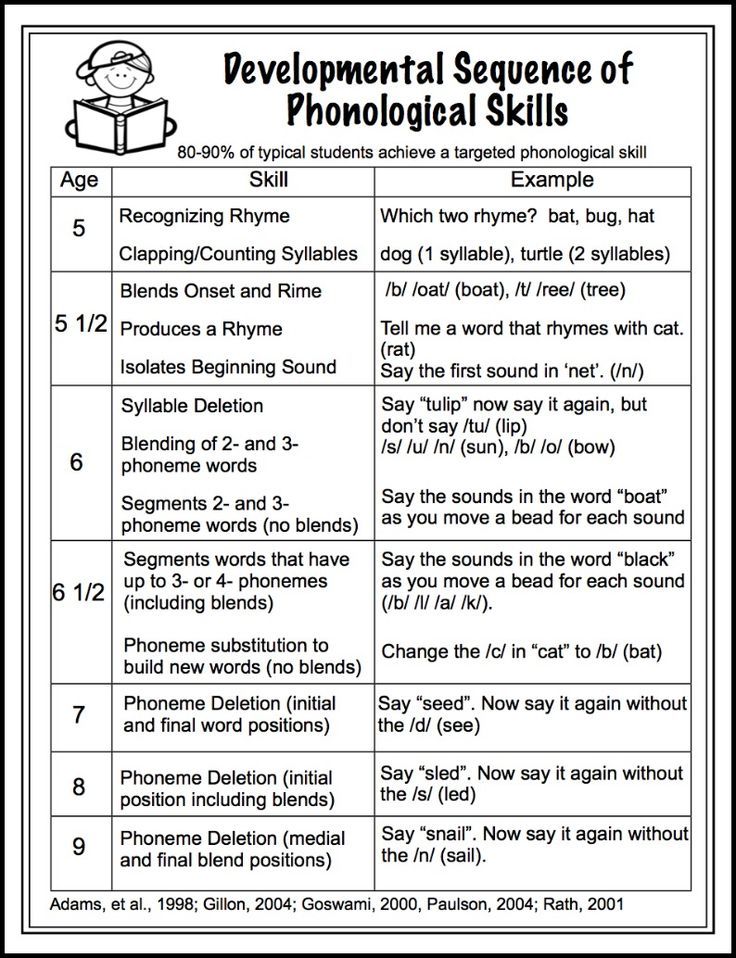

To develop phonological awareness, kindergarten and first grade students must demonstrate understanding of spoken words, syllables, and sounds (phonemes).

Read Naturally programs that develop phonemic awareness

Why Phonemic Awareness Is Important

First of all, phonemic awareness performance is a strong predictor of long-term reading and spelling success (Put Reading First, 1998). Students with strong phonological awareness are likely to become good readers, but students with weak phonological skills will likely become poor readers (Blachman, 2000). It is estimated that the vast majority—more than 90 percent—of students with significant reading problems have a core deficit in their ability to process phonological information (Blachman, 1995).

In fact, phonemic awareness performance can predict literacy performance more accurately than variables such as intelligence, vocabulary knowledge, and socioeconomic status (Gillon, 2004). The good news is that phonological awareness is one of the few factors that teachers are able to influence significantly through instruction—unlike intelligence, vocabulary, and socioeconomic status (Lane and Pullen, 2004).

Many students (75%) enter kindergarten with proficient phonemic awareness skills. The 25% of students who have not mastered these skills are from all socio-economic backgrounds and need explicit instruction in phonemic awareness. When instruction is engaging and developmentally appropriate, researchers recommend that all kindergarten students receive phonemic awareness instruction (Adams, 1990).

When instruction is engaging and developmentally appropriate, researchers recommend that all kindergarten students receive phonemic awareness instruction (Adams, 1990).

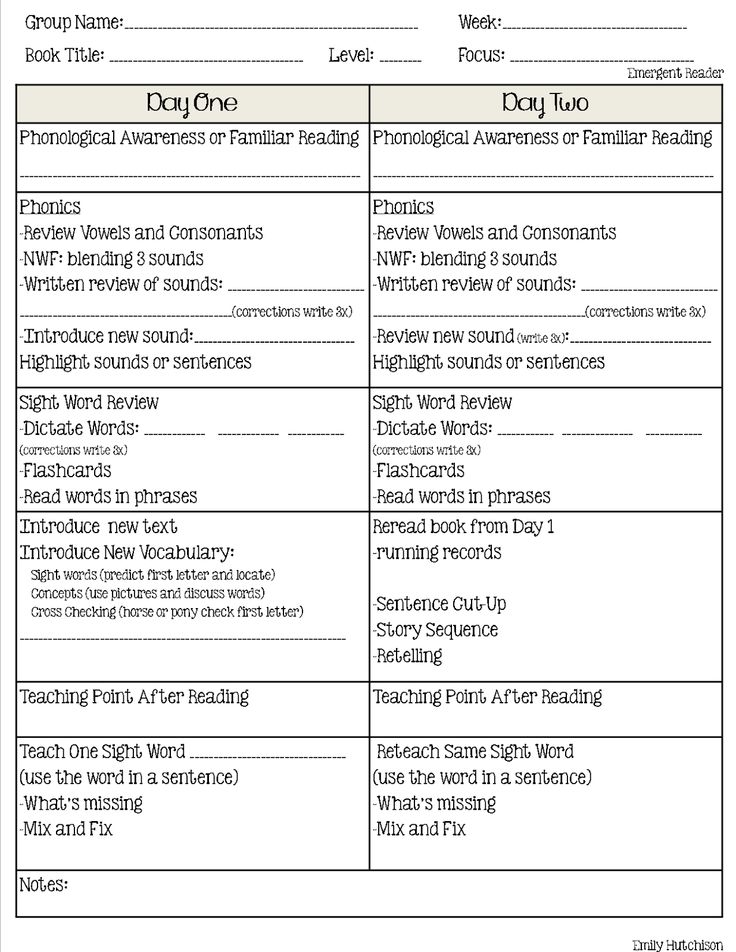

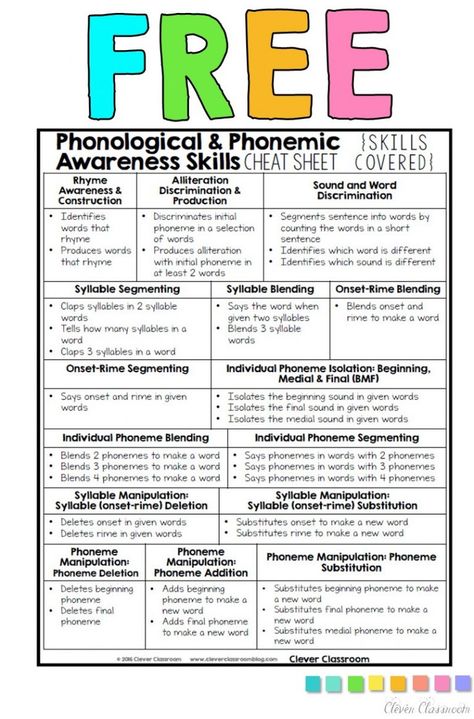

Phonological Awareness Skills

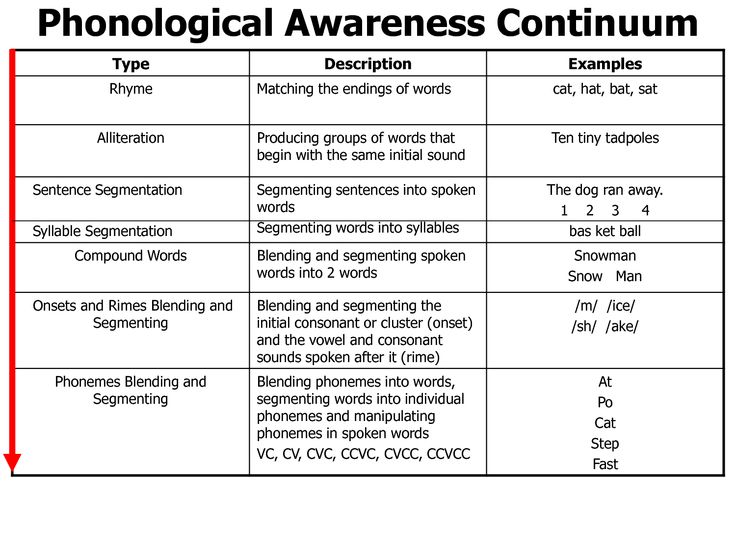

The following table shows how the specific phonological awareness standards fall into the four developmental levels: word, syllable, onset-rime, and phoneme. The table shows the specific skills (standards) within each level and provides an example for each skill.

| Less Complex | | More Complex | ||

| Word Awareness | Syllable Awareness | Onset-Rime Awareness | Phoneme Awareness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Complex | Sentence Segmentation Tap one time for every word you hear in the sentence:

I like cookies. | Rhyme Recognition Do these two words rhyme: ham, jam? (yes) | Isolation What is the first sound in fan? (/f/) What is the last sound in fan? (/n/) What is the middle sound in fan? (/a/) | |

| | Rhyme Generation Tell me a word that rhymes with nut. (cut) | Identification Which word has the same first sound as car: fan, corn, or map? (corn) | ||

| Categorization Which word does not belong: mat, sun, cat, fat? (sun) | Categorization Which word does not belong? bus, ball, house? (house) | |||

| Blending Listen as I say two small words: rain … bow.  Put the two words together to make a bigger word. (rainbow) | Blending Put these word parts together to make a whole word: rock•et. (rocket) | Blending What word am I saying? /b/ … /ig/? (big) | *Blending What word am I saying /b/ /ĭ/ /g/? (big) | |

| Segmentation Clap the word parts in rainbow. (rain•bow) How many times did you clap? (two) | Segmentation Clap the word parts in rocket. (roc•ket) | Segmentation Say big in two parts. (/b/ … /ig/) | *Segmentation How many sounds in big? (three) Say the sounds in big. (/b/ /ĭ/ /g/) | |

| Deletion Say rainbow. Now say rainbow without the bow. (rain) | Deletion Say pepper.  Now say pepper without the /er/. (pep) | Deletion Say mat . Now say mat without the /m/. (at) | Deletion Say spark. Now say spark without the /s/. (park) | |

| Addition Say park. Now add /s/ to the beginning of park. (spark) | ||||

| More Complex | Substitution The word is mug. Change /m/ to /r/. What is the new word? (rug) | |||

*Integrated instruction in phoneme segmenting and blending provides the greatest benefit to reading acquisition (Snider, 1995).

Instruction should be systematic. Notice the arrow across the top. The levels become more complex as students progress from the word level to syllables, to onset and rime, and then to phonemes.

Notice the arrow along the left-hand side. Students progress down each level—learning increasingly more complex skills within a level.

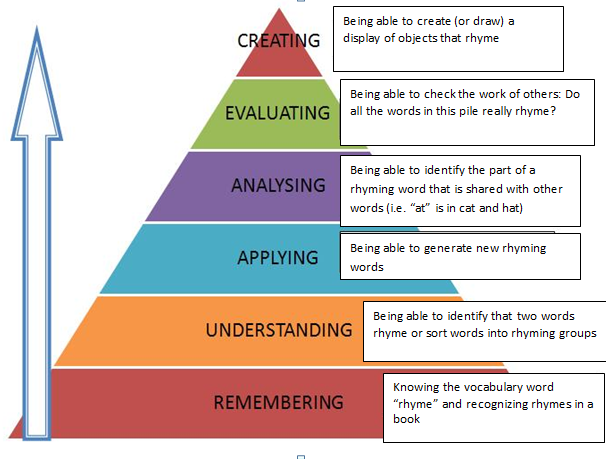

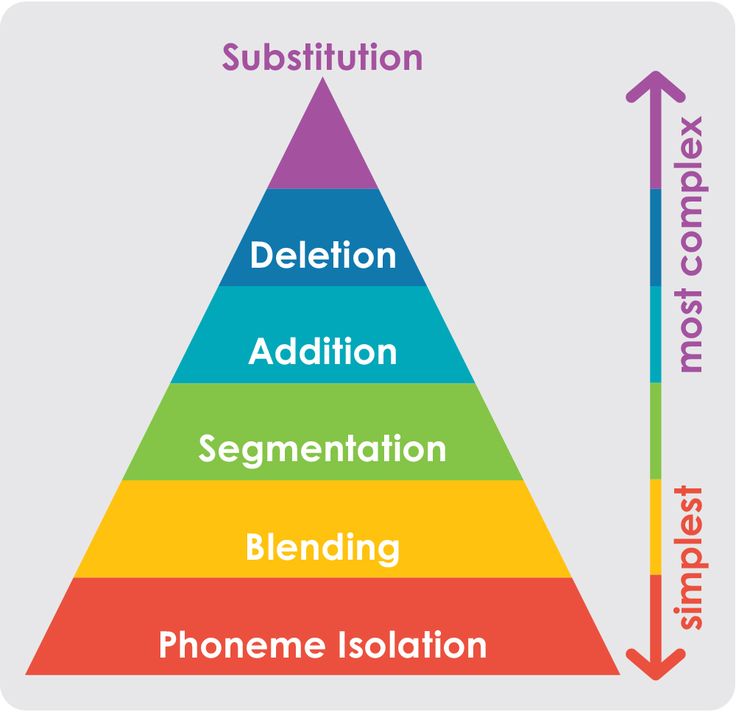

For example, look at the Phoneme Awareness column. Students learn to isolate, identify, and categorize phonemes first. Then students are taught to blend phonemes to make a word before they are taught to segment a word into phonemes—which is typically more difficult. The most challenging phonological awareness skills are at the bottom: deleting, adding, and substituting phonemes.

Blending phonemes into words and segmenting words into phonemes contribute directly to learning to read and spell well. In fact, these two phonemic awareness skills contribute more to learning to read and spell well than any of the other activities under the phonological awareness umbrella (National Reading Panel, 2000; Snider, 1995).

So, as we plan phonological awareness instruction, our goal is to systematically move students as quickly as possible toward blending and segmenting at the phoneme level.

Consonant Phonemes

There are two types of consonant phonemes:

| Type | Description | Phonemes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous sounds* | A sound that can be pronounced for several seconds without any distortion. | /f/ • /l/ • /m/ • /n/ • /r/ • /s/ • /v/ • /w/ •/y/ • /z/ • /a/ • /e/ • /i/ • /o/ • /u/ |

| Stop sounds | A sound that can be pronounced for only an instant. Avoid adding /uh/. | /b/ • /d/ • /g/ • /h/ • /j/ • /k/ • /p/ • /t/ |

*Blending words with continuous sounds is easier than blending words with stop sounds.

The continuous sounds can be pronounced for several seconds without distortion. The stop sounds can be pronounced only for an instant. It is important to avoid adding /uh/ to a stop sound as it is pronounced—which confuses students. As new phonological awareness skills are introduced, using continuous sounds may be easier at first.

Read Naturally Programs That Develop Phonemic Awareness

Funēmics: A Phonemic Awareness Program for Small GroupsRead Naturally’s Funēmics is a systematic, program for pre-readers or struggling beginning readers that teaches all of the phonological awareness standards. Each lesson builds on skills taught in previous lessons, adding just a few elements at a time. With minimal preparation, teachers or aides present scripted instruction to small groups of students, using an interactive display (with brightly illustrated pages and interactive widgets) viewed on a tablet or whiteboard. Funēmics is entirely pre-grapheme.

Learn more about how Funēmics teaches phonological awareness skills:

- Learn more about Funēmics

- Funēmics sampler

- Research basis for Funēmics

Other Programs That Support Phonemic Awareness

The following programs do not focus on phonemic awareness but include phonemic awareness activities as part of a broader scope of instruction:

| Read Naturally® GATE Teacher-led instruction for small groups of early readers.  Focuses on phonics and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary. Focuses on phonics and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary.Learn more about Read Naturally GATE |

| Word Warm-ups® A mostly independent, audio-supported program for developing automaticity in phonics and decoding. Focuses on phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness and fluency. Learn more about Word Warm-ups (reproducible masters with audio) Learn more about Word Warm-ups Live (web application) |

| Signs for SoundsTM Teacher-led, small-group instruction for teaching regular phonetic spelling patterns and high-frequency words through spelling. Focuses on spelling and phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness. Learn more about Signs for Sounds |

Bibliography

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Blachman, B. A. (2000). Phonological awareness. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Rosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, 3, pp. 483-502. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Blachman, B. A. (1995). Identifying the core linguistic deficits and the critical conditions for early intervention with children with reading disabilities. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Learning Disabilities Association, Orlando, FL, March 1995.

Gillon, G. T. (2004). Phonological awareness: From research to practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

Lane, H. B., and P. C. Pullen. (2004). A sound beginning: Phonological awareness assessment and instruction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

National Institute for Literacy. (1998). Put reading first. <http://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/PRFbooklet.pdf>

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

(2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Snider, V. A. (1995). A primer on phonemic awareness: What it is, why it’s important, and how to teach it. School Psychology Review, 24(3), pp. 443-456.

Phonological and Phonemic Awareness: Introduction

Learn the definitions of phonological awareness and phonemic awareness — and how these pre-reading listening skills relate to phonics.

Letter of completion

After completing this module and successfully answering the post-test questions, you'll be able to download a Letter of Completion.

Phonological awareness and phonemic awareness: what’s the difference?

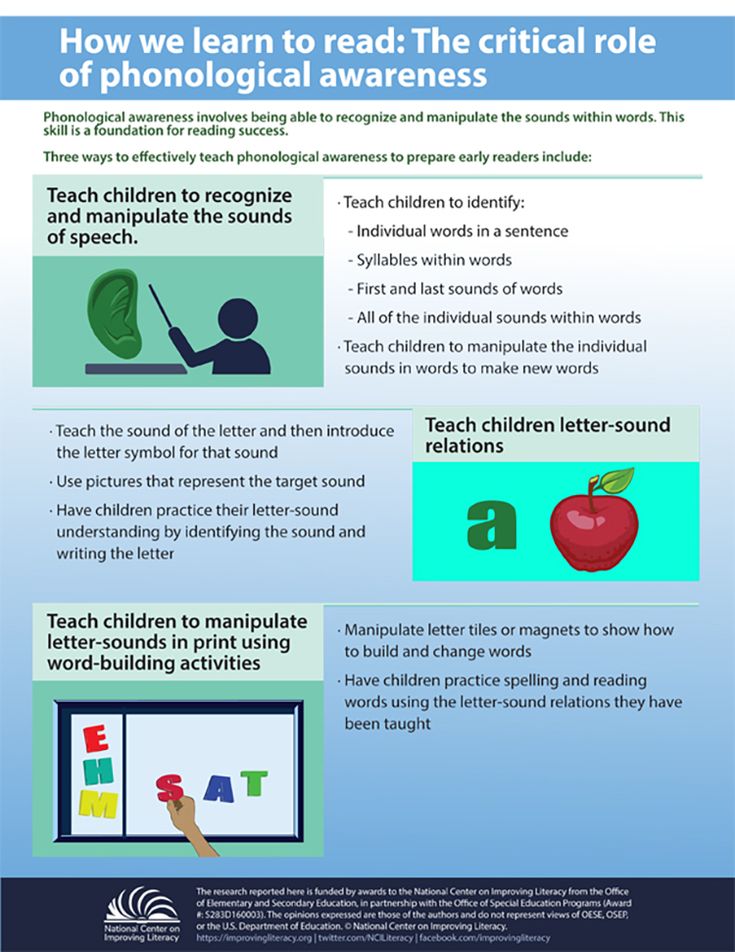

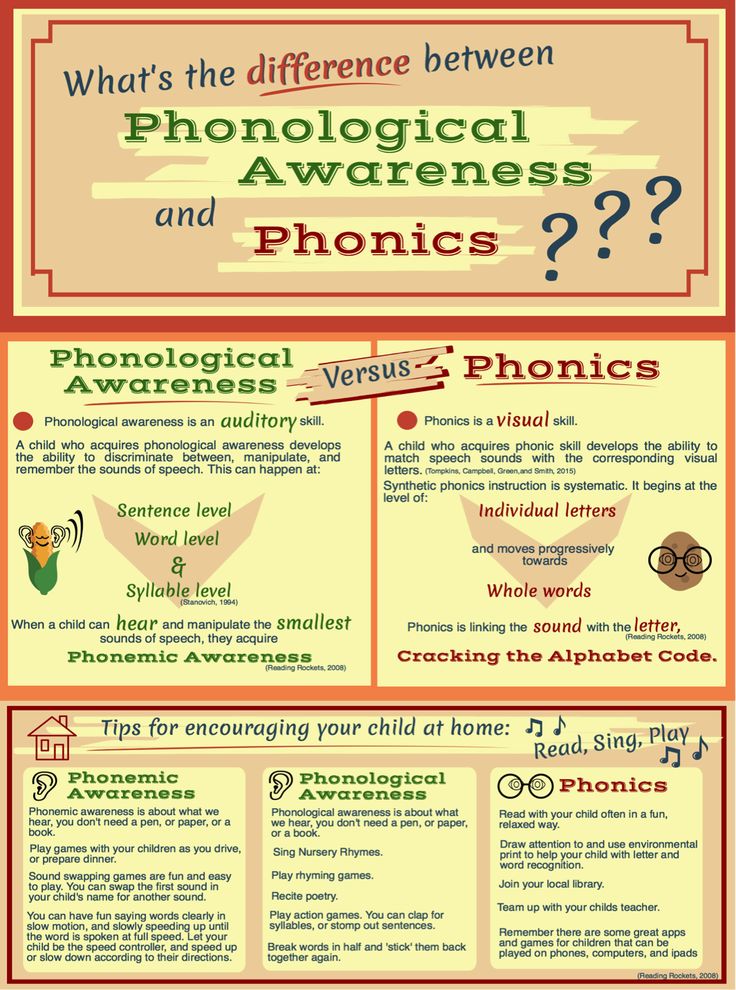

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognize and manipulate the spoken parts of sentences and words. Examples include being able to identify words that rhyme, recognizing alliteration, segmenting a sentence into words, identifying the syllables in a word, and blending and segmenting onset-rimes. The most sophisticated — and last to develop — is called phonemic awareness.

The most sophisticated — and last to develop — is called phonemic awareness.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to notice, think about, and work with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. This includes blending sounds into words, segmenting words into sounds, and deleting and playing with the sounds in spoken words.

Phonological awareness (PA) involves a continuum of skills that develop over time and that are crucial for reading and spelling success, because they are central to learning to decode and spell printed words. Phonological awareness is especially important at the earliest stages of reading development — in pre-school, kindergarten, and first grade for typical readers.

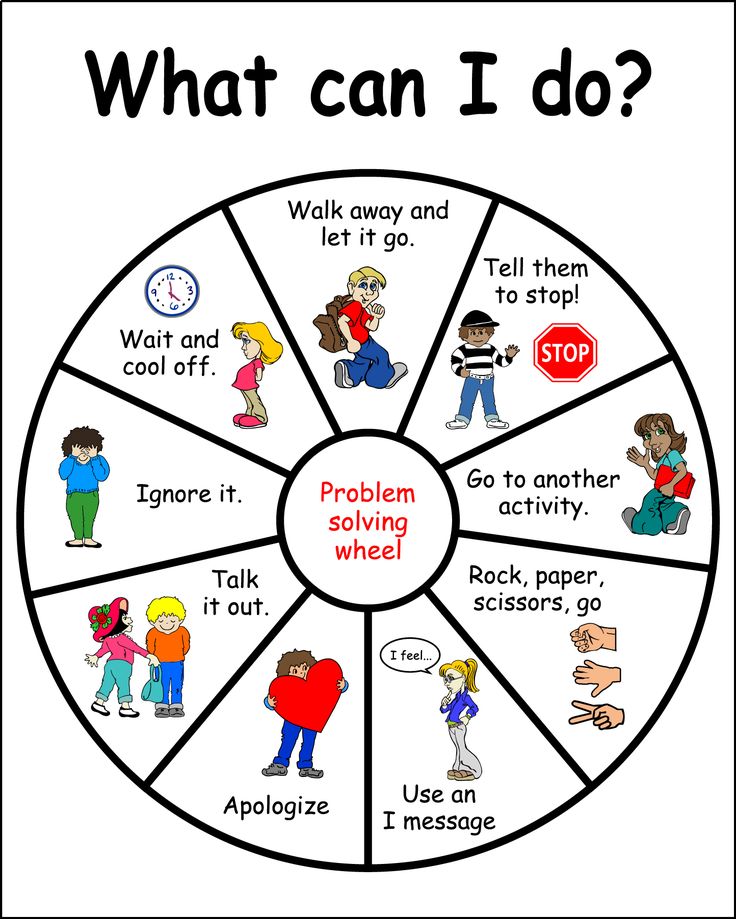

Explicit teaching of phonological awareness in these early years can eliminate future reading problems for many students. However, struggling decoders of any age can work on phonological awareness, especially if they evidence problems in blending or segmenting phonemes.

How about phonological awareness and phonics?

Phonological awareness refers to a global awareness of sounds in spoken words, as well as the ability to manipulate those sounds.

Phonics refers to knowledge of letter sounds and the ability to apply that knowledge in decoding unfamiliar printed words.

So, phonological awareness refers to oral language and phonics refers to print. Both of these skills are very important and tend to interact in reading development, but they are distinct skills; children can have weaknesses in one of them but not the other.

For example, a child who knows letter sounds but cannot blend the sounds to form the whole word has a phonological awareness (specifically, a phonemic awareness) problem. Conversely, a child who can orally blend sounds with ease but mixes up vowel letter sounds, reading pit for pet and set for sit, has a phonics problem.

44 phonemes

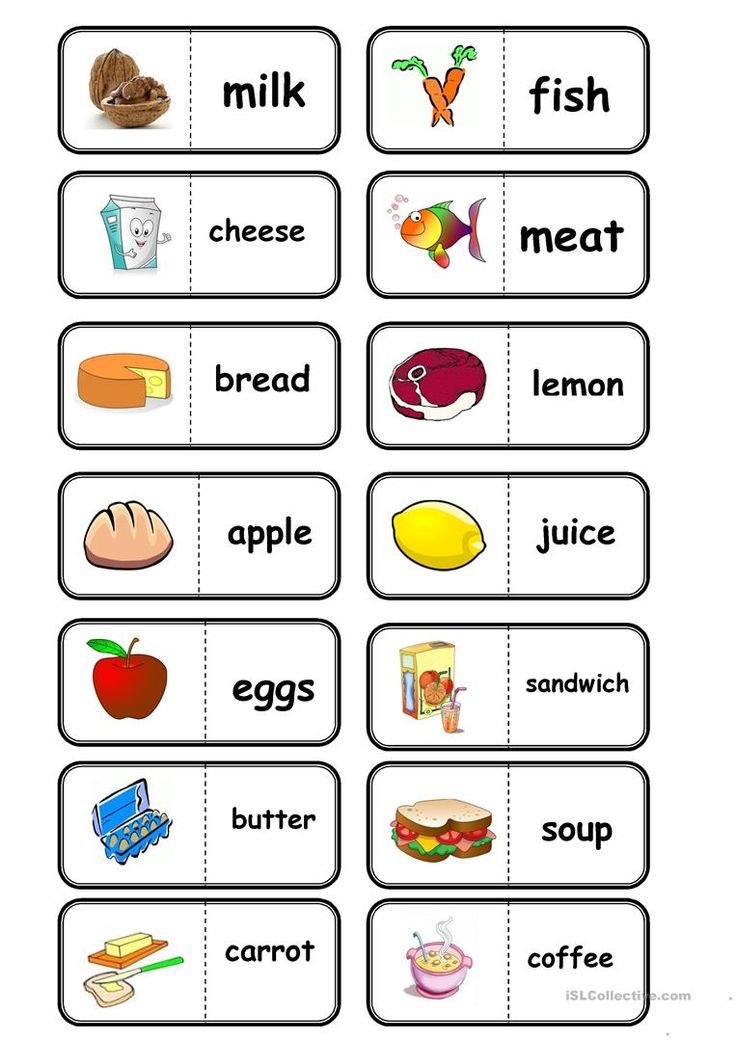

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet that make up 44 speech sounds, or phonemes.

Letters vs. phonemes

Dr. Louisa Moats explains to a kindergarten teacher why it is critical to differentiate between the letters and sounds within a word when teaching children to read and write.

Next: Phonological and Phonemic Awareness Pre-Test >

The quality of diagnosing dyslexia depends on the complexity of the tests - Nauka - Kommersant

Researchers at the Higher School of Economics found that complex phonological tests involving several cognitive processes predict dyslexia better than simple ones. They also help to determine which of the cognitive processes is impaired.

They also help to determine which of the cognitive processes is impaired.

Photo: Dmitry Lebedev, Kommersant

Photo: Dmitry Lebedev, Kommersant

Dyslexia is a common disorder characterized by persistent difficulty in learning to read. In Russia, symptoms of dyslexia appear in 10–15% of schoolchildren. Contrary to myths, dyslexia is not associated with pedagogical neglect or low intelligence - it is an innate feature of the child.

In world science, it has long been believed that one of the main causes of dyslexia is a phonological deficit - the inability to distinguish between phonemes, that is, speech sounds (the minimum meaningful units of the language), as well as to carry out all kinds of operations with them. Presumably, because of this difficulty, problems arise in the process of reading - at the stage of correlating letters with sounds. nine0004

The phonological deficit hypothesis explains why a child with dyslexia often fails on phonological tests. However, until now it has not been clear which of the phonological tests are best suited for diagnosing dyslexia.

However, until now it has not been clear which of the phonological tests are best suited for diagnosing dyslexia.

Researchers from the Higher School of Economics, Moscow State University, and the Center for Speech Pathology and Neurorehabilitation suggested that phonological tests may differ in their level of difficulty, i.e., in the number of speech and cognitive processes that must be activated to successfully complete the task. Thus, the simple task of distinguishing sounds in short pseudowords (for example, "iva - yva") requires fewer cognitive processes: the sounds must be recognized, retained in memory and compared. A more complex task involves a whole complex of processes. So, in order to replace a sound in a word, you need to accurately hear the task, keep this task and the word itself in memory, highlight the desired sound in the word, mentally replace the sound and pronounce the resulting word aloud. nine0004

Researchers have suggested that more sophisticated phonological tests may better predict a child's risk of dyslexia than simpler ones. This is due to the fact that more processes are required to successfully complete complex tests, some of which overlap with the processes required for successful reading.

This is due to the fact that more processes are required to successfully complete complex tests, some of which overlap with the processes required for successful reading.

To test this, the researchers compared the performance of various phonological tasks by children with and without dyslexia. The study used a battery of seven phonological tests ZARYA, a comprehensive diagnostic tool developed at the National Research University Higher School of Economics. It includes phonological tests of different levels of difficulty, depending on how many language processing processes need to be involved in order to successfully complete the tasks. nine0004

The study involved 173 children aged 7–11 (grades 1–4) from Russian schools. Forty-nine of them had a clinical diagnosis of dyslexia, and the remaining participants had no difficulty in learning to read. In all children, the level of development of non-verbal intelligence was not below the norm, and the absence of primary hearing impairments was additionally checked.

A comparison of the results of the two groups showed that children with dyslexia cope with the simplest phonological tests - to distinguish between similar sounds and to differentiate between real words and made-up words that differ from real ones by one or two sounds - just as well as schoolchildren who do not experience difficulties with reading. However, more complex tasks were given to children with dyslexia much more difficult. nine0004

The best predictor of a child's dyslexia was their performance on the first sound naming and pseudoword sound replacement tasks—these tasks involve the most verbal and cognitive processes, from working memory to articulation.

Presumably, as task complexity increases, so does overall cognitive load—the ability to perform several different processes quickly or almost simultaneously. Therefore, a greater number of children with dyslexia do not cope with such tasks. nine0004

According to the researchers, comparing the composition of cognitive processes in tests that a child performed successfully and those in which he did not cope can help determine which process is impaired, which provides valuable information for corrective planning.

Half of the dyslexic children in the sample could not cope with the most difficult phonological tasks. This can signal both difficulties with the implementation of individual processes (phonemic analysis, speech working memory, articulation coordination), and an inability to withstand a general increase in cognitive load. Another 50% of children with dyslexia completed the tasks of all phonological tests at the normal level. Perhaps the cause of the reading disorder is another deficit or a combination of deficits, the researchers suggest. nine0004

Svetlana Dorofeeva, author of the study, researcher at the HSE Center for Language and Brain:

— How is dyslexia now defined?

— If the question is about the definition of the term, then in the Russian tradition dyslexia is understood as a specific disorder in the processes of learning to read, which has a neurobiological basis (features of the structure and / or functioning of the brain) and manifests itself in numerous repeated errors of a persistent nature, despite a sufficient level of intellectual and speech development and the absence of violations of the auditory and visual analyzers. nine0004

nine0004

If the question is about the diagnosis of dyslexia, then it is more difficult to answer unambiguously. The experience of countries in which this problem has been actively dealt with at the state level for a long time shows that in order to reliably detect violations, standardized protocols are needed to assess both the reading skill itself and a number of cognitive functions, the successful development of which is important for reading.

To assess reading skills, specialized batteries of reading tests of various types are used (reading words, pseudo-words, sentences, texts of various levels of complexity). Tests for reading of various types are necessary in order to assess how exactly the reading process is impaired in a particular child (for example, whether the success of reading depends on the need for morphosyntactic processing, on the presence of context, on the frequency of words, etc.). nine0004

To evaluate reading-important functions, standardized batteries are used to assess phonological processing skills, visual perception, general speech development, non-verbal intelligence, etc.

the transition to such a diagnosis being established collectively - for example, parents are advised to contact the PMPK (psychological-medical-pedagogical commissions). In view of the complexity of the possible structure of the disorder (reading can be impaired in many different ways for many different reasons), an integrated approach to diagnosis is warranted. nine0004

The main problem at present, in our opinion, is the low inter-expert reliability of diagnostics. In particular, by referring to three different specialists about the risk of developing dyslexia, parents can get different diagnoses for their child. This, in turn, is due to the fact that a sufficient number of standardized tools for assessing reading skill have not been developed for the Russian language (there was only one standardized test for assessing reading skill at the text level) and important reading functions, normative data have not been collected and control diagnostic levels are defined, diagnostic protocols are formalized. nine0004

nine0004

The development of such tools, and especially their standardization, are rather time-consuming tasks. The HSE Center for Language and Brain has been working in this direction since 2017. A phonological battery has been developed, standardized and tested through a series of studies, and a battery of visual tests and a battery of reading tests are under development.

— Why do HSE experts believe that more sophisticated phonological tests can better predict a child's risk of dyslexia? nine0035

- This is shown by the results of our study. We collected data from children without reading difficulties and children with clinically diagnosed dyslexia, analyzed in different ways (intergroup comparisons, calculation of sensitivity and specificity of each of the series of phonological tests, ROC analysis, analysis using linear models) and found that it is complex tests that involve a greater number of speech processes that better predict reading disorders.

— How was the research?

— We have developed a battery of phonological tests ZARYA (sound analysis of the Russian language) especially for the Russian language. When developing, we relied both on the experience of foreign studies and samples of phonological batteries for English and other European languages, as well as on the domestic tradition and a neuropsychological approach to studying learning difficulties.

When developing, we relied both on the experience of foreign studies and samples of phonological batteries for English and other European languages, as well as on the domestic tradition and a neuropsychological approach to studying learning difficulties.

Using the experience of Western research, we have developed for each test sets of stimuli that allow for reliable quantitative assessment, described and applied an unambiguous protocol for testing and evaluation of results. Using the experience of domestic neuropsychologists, we have selected such a set of tests themselves so that it is possible to assess the contribution of various speech processes to the level of development of the phonological processing skill in a person undergoing testing. We assessed each task in terms of whether it involved primary speech perception, auditory-speech memory, lexical access, phonemic analysis, phoneme operations, speech production processes, and articulation. nine0004

Moreover, our battery has two important advantages: a strong linguistic component and a convenient tablet form. In other words, it was difficult to make it (we selected stimuli both taking into account the observations of domestic speech therapists about what type of mistake children with dyslexia make more often, and taking into account a number of psycholinguistic parameters: the age of learning words, their frequency, syllabic structure, articulatory complexity, and etc.), but it is quite easy to use (all stimuli are recorded by the speaker in the studio, presented to all participants in the same way, the results in the comprehension tests are recorded and calculated automatically, the answers in the generation tests are recorded, they can be re-listened, marked in the application, and the program will also calculate the results and display them in comparison with the norms; the norms have so far been collected only for children in grades 1-4). To date, there is no phonological battery of tests for any language in the world that would have all these advantages at the same time. nine0004

In other words, it was difficult to make it (we selected stimuli both taking into account the observations of domestic speech therapists about what type of mistake children with dyslexia make more often, and taking into account a number of psycholinguistic parameters: the age of learning words, their frequency, syllabic structure, articulatory complexity, and etc.), but it is quite easy to use (all stimuli are recorded by the speaker in the studio, presented to all participants in the same way, the results in the comprehension tests are recorded and calculated automatically, the answers in the generation tests are recorded, they can be re-listened, marked in the application, and the program will also calculate the results and display them in comparison with the norms; the norms have so far been collected only for children in grades 1-4). To date, there is no phonological battery of tests for any language in the world that would have all these advantages at the same time. nine0004

The study involved children aged 7-11 years, students of elementary school. 124 children without learning difficulties and 49 children with clinically diagnosed dyslexia were recruited. All participants in the study had a level of non-verbal intelligence not lower than the age norm (we checked this using the Raven test), there were no primary hearing impairments (we checked this using audiometry), there were no uncorrected visual impairments, as well as mental and neurological disorders, brain injuries and brain surgery (according to information from the parents of the participants). nine0004

124 children without learning difficulties and 49 children with clinically diagnosed dyslexia were recruited. All participants in the study had a level of non-verbal intelligence not lower than the age norm (we checked this using the Raven test), there were no primary hearing impairments (we checked this using audiometry), there were no uncorrected visual impairments, as well as mental and neurological disorders, brain injuries and brain surgery (according to information from the parents of the participants). nine0004

For each child in both groups, we assessed text reading skills (for additional verification of the diagnosis of dyslexia) and assessed phonological processing skills in detail (using all tests of the ZARYA battery). Testing took place individually, in a comfortable environment for children. At the end of testing, each child received a small gift, and parents, if desired, could receive an individual report on the results of passing all tests by their child.

- What did it show? nine0035

— We conducted several analysis options: intergroup comparisons, calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of each of the seven phonological tests, ROC analysis, analysis using linear models. The results showed that it is complex tests that involve a greater number of speech processes for their successful implementation that better predict reading disorders, and allow better classification of children as having or not having dyslexia.

The results showed that it is complex tests that involve a greater number of speech processes for their successful implementation that better predict reading disorders, and allow better classification of children as having or not having dyslexia.

It is worth noting that this was the first detailed study of phonological processing skills in Russian-speaking children with dyslexia - there were no tools for this before. In our sample (where we controlled for the absence of primary hearing impairment and non-verbal intelligence impairment), we found that almost all dyslexic children performed well on simple phonological tasks (90–96%). This suggests that the majority of Russian-speaking children with dyslexia do not have difficulty distinguishing individual speech sounds. Difficulties arise when it is necessary to track the presence of certain sounds in the speech stream, perform operations with phonemes, involve auditory-speech working memory and articulation. The more such processes were required to successfully complete a particular phonological test, the better the test predicted both reading outcomes and risk of dyslexia. At the same time, individual variability in the development of phonological processing skills is quite large. nine0004

At the same time, individual variability in the development of phonological processing skills is quite large. nine0004

Up to 50% of the dyslexic children in our sample had complex phonological processing impairments. It can be argued that it is these children with dyslexia who need the help of speech therapists in the first place. It is worth noting that in this study we paid special attention to the phonological hypothesis of dyslexia. However, other factors can also be the causes of reading disorders: features of visual and visuospatial perception, features of the development of executive functions, etc. These factors deserve close attention in further research. nine0004

— Why is early detection of dyslexia important in children?

— The lack of timely diagnosis leads to the fact that the child does not receive the necessary assistance and this negatively affects the entire learning process, hinders the growth of basic knowledge and becomes an extremely difficult life experience for both the child and his family members. Research shows that without adequate help, children experience anxiety and depressive behavior, suicidal thoughts, and school failure. Timely and accurate establishment of both the diagnosis of dyslexia itself and the causes of difficulties in learning to read is extremely important for planning correction programs and a reasonable distribution of the forces of the children themselves, their parents and teachers. nine0004

Research shows that without adequate help, children experience anxiety and depressive behavior, suicidal thoughts, and school failure. Timely and accurate establishment of both the diagnosis of dyslexia itself and the causes of difficulties in learning to read is extremely important for planning correction programs and a reasonable distribution of the forces of the children themselves, their parents and teachers. nine0004

Prepared by Maria Gribova

Questions of theory and practice (included in the list of VAK) . Tambov: Diploma, 2021. No. 4. S. 616-622.

Questions of theory and practice (included in the list of VAK) . Tambov: Diploma, 2021. No. 4. S. 616-622.  The purpose of the study is to identify existing empirical approaches to measuring the parameters of assessing phonological competence (FC), namely phonological intelligibility (intelligibility), ease of speech perception (comprehensibility) and the degree of manifestation of a foreign accent (accentedness). The article discusses the main empirical approaches to measuring the level of proficiency in phonological competence in English as a global lingua franca, in particular, methods for quantifying three parameters of oral foreign speech are analyzed: phonological intelligibility, ease of perception and the degree of manifestation of a foreign accent. In accordance with the objectives of the study, the advantages, disadvantages and conditions for the use of each of the analyzed measurement methods are characterized based on the results of the analysis of modern empirical studies, the expediency of using the discussed methods in linguodidactic studies of FC at the level of higher education in Russia is assessed.

The purpose of the study is to identify existing empirical approaches to measuring the parameters of assessing phonological competence (FC), namely phonological intelligibility (intelligibility), ease of speech perception (comprehensibility) and the degree of manifestation of a foreign accent (accentedness). The article discusses the main empirical approaches to measuring the level of proficiency in phonological competence in English as a global lingua franca, in particular, methods for quantifying three parameters of oral foreign speech are analyzed: phonological intelligibility, ease of perception and the degree of manifestation of a foreign accent. In accordance with the objectives of the study, the advantages, disadvantages and conditions for the use of each of the analyzed measurement methods are characterized based on the results of the analysis of modern empirical studies, the expediency of using the discussed methods in linguodidactic studies of FC at the level of higher education in Russia is assessed. The scientific novelty of the study lies in the fact that within the framework of this article, for the first time in Russian, the international methodology for measuring the parameters of assessing phonological competence corresponding to the concept of English as a lingua franca and the latest pan-European recommendations of the Common European Framework of Reference (2020) is analyzed in detail. As a result of the study, the most important advantages and disadvantages of each of the modern methods used to measure the above speech parameters were identified, and the feasibility of using these methods in linguo-didactic studies of phonological competence at the level of higher education in Russia was assessed. nine0004

The scientific novelty of the study lies in the fact that within the framework of this article, for the first time in Russian, the international methodology for measuring the parameters of assessing phonological competence corresponding to the concept of English as a lingua franca and the latest pan-European recommendations of the Common European Framework of Reference (2020) is analyzed in detail. As a result of the study, the most important advantages and disadvantages of each of the modern methods used to measure the above speech parameters were identified, and the feasibility of using these methods in linguo-didactic studies of phonological competence at the level of higher education in Russia was assessed. nine0004  A free PDF viewer can be downloaded here. nine0103

A free PDF viewer can be downloaded here. nine0103  Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2020. URL: https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989 (accessed 20/07/2021).

Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2020. URL: https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989 (accessed 20/07/2021).  , Thomson R., Moran M. Empirical approaches to measuring the intelligibility of different varieties of English in predicting listener comprehension: Measuring intelligibility in varieties of English // Language Learning. 2018 Vol. 68. No. 1. P. 115-146.

, Thomson R., Moran M. Empirical approaches to measuring the intelligibility of different varieties of English in predicting listener comprehension: Measuring intelligibility in varieties of English // Language Learning. 2018 Vol. 68. No. 1. P. 115-146.  VIII+150 p.

VIII+150 p.  2015. Vol. 38. No. 4. P. 439-462.

2015. Vol. 38. No. 4. P. 439-462.