Level q reading passages

Leveled Books

Home > Leveled Books

As a member of Raz-Plus, you gain access to thousands of leveled books, assessments, and other resources in printable, projectable, digital, and mobile formats.

Ensure success in your classroom and beyond with engaging, developmentally appropriate books at various levels of text complexity. Students can read texts at different levels and in their areas of interest anytime with 24/7 Web access to the practice they need to become better, more confident readers. Easily assign books using the Assign button on the book's thumbnail or landing page.

More About Leveled Books

Showing 812 of 812 books View

The Birthday Party Level aa Fiction

City Street Level aa Nonfiction

The City Level aa Nonfiction

The Classroom Level aa Nonfiction

Farm Animals Level aa Nonfiction

Fido Gets Dressed Level aa Fiction

The Fort Level aa Nonfiction

The Garden Level aa Nonfiction

Good Night Level aa Fiction

In Level aa Fiction

It Is Fall Level aa Nonfiction

Little Level aa Nonfiction

My Family Level aa Fiction

On Level aa Fiction

Play Ball! Level aa Nonfiction

The Playground Level aa Nonfiction

Spring Level aa Nonfiction

Summer Level aa Nonfiction

Summer Picnics Level aa Nonfiction

We Go Camping Level aa Fiction

Yellow Level aa Nonfiction

All Kinds of Faces Level A Nonfiction

Athletes Level A Nonfiction

Baby Animals Level A Nonfiction

Bedtime Counting Level A Fiction

The Big Cat Level A Fiction

Bird Colors Level A Nonfiction

Bird Goes Home Level A Fiction

Building with Blocks Level A Fiction

Car Parts Level A Nonfiction

Carlos Counts Kittens Level A Fiction

Carlos Goes to School Level A Fiction

Clean, Not Clean Level A Fiction

The Forest Level A Nonfiction

Going Places Level A Nonfiction

Hot and Cold Level A Nonfiction

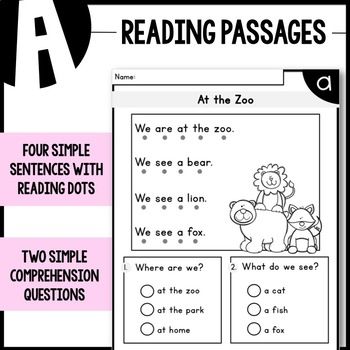

Reading Intervention Program: Sets Q-T

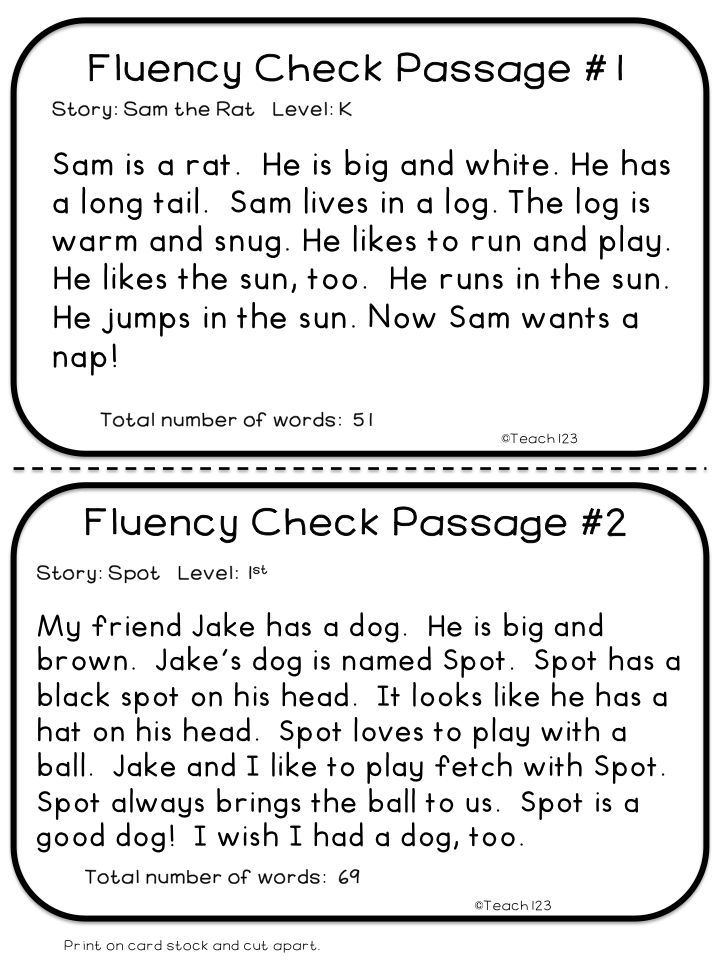

1. 100 reading passages with appropriate content and language for levels Q-T (including both fiction and nonfiction passages).

2. Reading passages in 5 different student-friendly formats

3. Teacher/tutor fluency page with clear directions, running record with word count, and space for scoring fluency skills.

4. Targeted Comprehension questions for each passage

5. Targeted Word Work activities for each passage

6. 5 Bolded vocabulary in each passage, with space for students to define each word.

7. Teacher/tutor comprehension, word work, and vocabulary instruction pages with space to collect data and additional comprehension questions for guided instruction.

8. Progress monitoring pages for teachers/tutors to track student growth with fluency, comprehension, word work, and vocabulary.

Each passage is NOT individually leveled, however, they range from Fountas and Pinnell Levels Q-T.

The daily intervention lessons contain extra practice with:

1. Reading Fluency

Reading Fluency

2. Comprehension (with weekly targeted skills)

3. Word Work (with weekly targeted skills)

4. Vocabulary (5 daily vocab. Words in every passage)

1. As a daily tier 2 reading intervention (as a small group of 3-4 students 1 year below reading grade level)

2. As a daily tier 3 intensive one-on-one reading intervention (most often with students 2+ years below reading grade level)

3. As a tier 2 ADVANCED intervention (as a small group of advanced, or gifted students who are above their grade’s reading level)

4. In literacy centers for extra reading practice

5. In guided reading groups for a structured tier 1 program

6. Administered by aids or school volunteers either daily or a few times a week to small groups or one-on-one.

7. As homework practice on reading. As a way for kids to simply spend more time reading and thinking about their reading.

8. One passage due per week

9. In a literature circle, where students from the same reading level range read and discuss the passage

10. In a reading partner setting during reading workshop

In a reading partner setting during reading workshop

11. As a whole group, using the comprehension skills as mini lesson topics

Each of the 5 Reading Intervention Sets can be purchased for $18 each, totaling $90. This Bundle saves you $18, so that's like getting one set free

OPTION ONE: purchased in a bundle of all one set per level range. This is a great option if you work with readers across several level ranges. Those bundles include 7 sets each, totaling $126 and discounted to $108 (like getting one set free)

OPTION TWO: purchased as the ENTIRE Reading Intervention Program. If you purchase the entire program with all 700 passages, you will save $145 (like getting 8 sets free).

Are each of the passages leveled separately?

A: Each passage is not leveled separately. I believe students can read on more than just one reading level. I think we limit our kids when we place them on only one level. That is why each set is a ‘range’ of 3-4 levels. If your students struggle reading the passage independently, it’s a perfect opportunity for reading instruction and modeling of reading to occur!

If your students struggle reading the passage independently, it’s a perfect opportunity for reading instruction and modeling of reading to occur!

Is this program research-based?

A: Yes! I have a pilot team that has been in place for two years. They are using the program in a variety of ways and reporting data to me. I will have the research results from the 2015-2016 school year available soon. Also, the program was designed after careful research in the best practices in reading instruction. Multiple professional development resources created from decades of research were studied and used as theoretical foundations to the program. The comprehension, word work, and vocabulary are all designed to specifically match the learning needs of readers at each level range.

Can parents do this at home?

A: Absolutely! The program is designed with careful instructions so that parents, aids, and school volunteers can easily administer and assess students’ reading skills. It is very easy to follow! Even students can work independently or with partners after they complete a few passages.

It is very easy to follow! Even students can work independently or with partners after they complete a few passages.

What reading program did you use to level the ranges?

A: I used Fountas and Pinnell for my reading levels. If you use a different program you can match it up with the conversion chart found here.

Are there answer keys provided?

A: Yes! There are answer keys for each of the comprehension questions in every passage.

How many of the passages are fiction and nonfiction?

A: In almost all the sets it is a 50/50 split, with 10 passages being fiction and 10 being nonfiction. There are fantasy, realistic fiction, biographies, informational, and content specific passages to name a few. The passage topics were carefully matched to common interests and understandings of students at each level.

About how long are the passages?

A: The passage lengths vary by their range. Here is a breakdown of passage lengths by levels:

Here is a breakdown of passage lengths by levels:

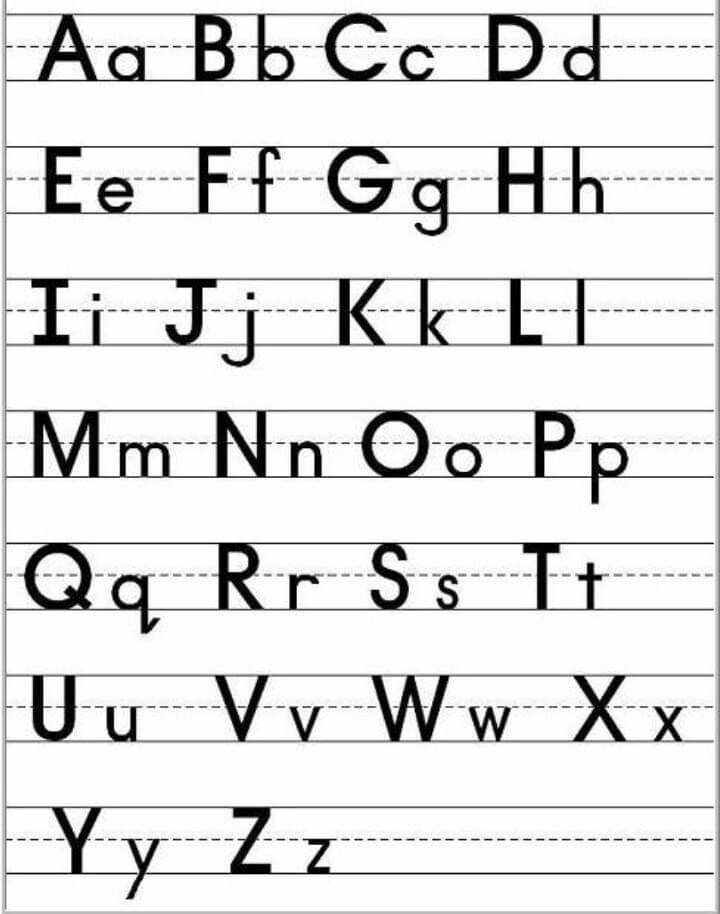

Levels A-D >> 50-65 words

Levels E-G >> 95-125 words

Levels H-K >> 140-170 words

Levels L-P >> 200-240 words

Levels Q-T >> 255-320 words

Levels U-W >> 255-320 words

Levels X-Z >> 255-320 words

What is the difference between the first and fifth set in every level range?

A: As far as the levels and passage difficulty, there is no difference from set one to set five. The sets do NOT get increasingly more difficult from set one to set five. The difference in each set is 20 new reading passages, along with different comprehension, word work and vocabulary skills to practice.

Do you use a new passage every day?

A: You can! But, you do not have to. The program is designed to be used in many ways (see ‘Ways to Use the Program’). Some teachers chose to focus on one passage for an entire week, while others move into a new passage each day. It truly depends on your schedule, and the learning needs of your students!

It truly depends on your schedule, and the learning needs of your students!

Do the students complete the passages independently?

A: They can, but if they need help, you can certainly do so. It is totally open to your students’ needs how you would like them to complete the work each day! Every classroom will be slightly different based on what works best for them!

How did you determine that the passages fit within each level range?

A: I used a combination of four things to determine that each passage was appropriate for the range it is in. First, I researched the Continuum of Literacy Learning by Fountas and Pinnell. I studied what readers can and cannot do at each of the guided reading levels in the Continuum. Second, I compared the passages to other texts at those levels to be sure the text difficulty, content, and sentence structures were appropriate. Third, I used the Fry Readability Scale to calculate each passage’s grade level. And finally, I used my training, experience, and understanding in theory as a Literacy Collaborative Coordinator to verify that the passages were appropriate for each level range.

And finally, I used my training, experience, and understanding in theory as a Literacy Collaborative Coordinator to verify that the passages were appropriate for each level range.

How can I gauge progress monitoring if the passages don't have one reading level?

A: This is a really great question. As I’ve said before, I believe kids are more than capable to perform on a range of levels, not just one. I use the progress monitoring data not so much to put them on one level as I do to see reading growth. I look at how they are growing in their comprehension, word work, vocabulary, and fluency skills. When I see growth in these key reading areas, I know they are becoming stronger readers, regardless of the text level. I know many teachers who use the program and progress monitor these skills. Then, they take a quarterly benchmark assessment with a leveled standardized program and see huge growth!

Below are just a few quotes from the 1,000's of teachers who are using the program and seeing huge success!

An excerpt from Proust and the Squid: The Neurobiology of Reading by Marianne Wolfe - Snob

In Proust and the Squid: The Neurobiology of Reading, the American neuroscientist Marianne Wolfe explains what changes occur in the brain when a person learns to read than the brain of a cuneiform clay reader. of a tablet differs from the brain of a person reading the alphabet, how long it takes on average to read one word and which writing system is most effective. With the permission of the publishing house "KoLibri" "Snob" publishes one of the chapters. You can learn more about diagnosing dyslexia from this article on Snob. The Investment in the Future Foundation, which helps children with dyslexia, is nominated for the Made in Russia award

of a tablet differs from the brain of a person reading the alphabet, how long it takes on average to read one word and which writing system is most effective. With the permission of the publishing house "KoLibri" "Snob" publishes one of the chapters. You can learn more about diagnosing dyslexia from this article on Snob. The Investment in the Future Foundation, which helps children with dyslexia, is nominated for the Made in Russia award

The tangled story begins where it should, in our evolutionary past. The essence of the origin of dyslexia was best expressed by the British neuropsychologist Andrew Ellis, who stated that, whatever it was, "it is not a reading disorder." What Ellis meant was that, evolutionarily speaking, the human brain was never designed to be read: there are no genes or biological structures that are read-only. Rather, each brain must learn to build new neural networks by linking older areas originally intended and genetically programmed for the other, such as recognizing objects and looking up their names. Dyslexia cannot be a flaw in the "reading center" of the brain, because it simply does not exist. To find the causes of dyslexia, we must look to older brain structures and the many layers of processes associated with those structures, other structures, neurons, and genes that must come together and synchronize to form the reading neural network.

Dyslexia cannot be a flaw in the "reading center" of the brain, because it simply does not exist. To find the causes of dyslexia, we must look to older brain structures and the many layers of processes associated with those structures, other structures, neurons, and genes that must come together and synchronize to form the reading neural network.

In other words, we will have to take a closer look at the five layers of the reading pyramid that we are already familiar with. It is shown again in Fig. 7.1 and represents activities, each of which serves the main type of behavior located in the upper layer: reading a word or sentence. Now I'm using this image with a new purpose: to help map out the various locations and states that can fail in a reading neural network. The second cognitive layer of the pyramid, which includes the basic perceptual, conceptual, linguistic, attentional, and motor processes, is an area that many psychologists study. Most 20th-century theorists believed that difficulties within this layer were the main explanation for dyslexia. In turn, many of its processes are based on neural structures, which (when connected to each other) form the neural networks that allow us to learn to read. A huge amount of neuroimaging research is devoted to the study of these structures and their connections: scientists are trying to understand what dyslexia is. Under this structural layer is a layer consisting of working groups of neurons. Their ability to create and find long-term representations of various types of information gives a person, for example, the ability to perfectly see and hear letters and phonemes - and do this automatically.

In turn, many of its processes are based on neural structures, which (when connected to each other) form the neural networks that allow us to learn to read. A huge amount of neuroimaging research is devoted to the study of these structures and their connections: scientists are trying to understand what dyslexia is. Under this structural layer is a layer consisting of working groups of neurons. Their ability to create and find long-term representations of various types of information gives a person, for example, the ability to perfectly see and hear letters and phonemes - and do this automatically.

The last layer of the pyramid represents the genes that program neurons to form groups, structures, and eventually neural networks for older processes such as vision and language. Some of the newest research on dyslexia is looking at these last layers. Work in this direction is complicated by the fact that the neural network used for reading does not have genes unique only to it, and cannot be inherited. Each time an individual's brain begins to master reading, the top four layers must re-learn how to form the necessary paths. As a result, reading does not come to children in the "natural" way that speech and vision do, so beginning little readers are especially vulnerable.

Each time an individual's brain begins to master reading, the top four layers must re-learn how to form the necessary paths. As a result, reading does not come to children in the "natural" way that speech and vision do, so beginning little readers are especially vulnerable.

The evolutionary approach to the reading brain presented in this book begins with three organizing principles that enabled the brain to read the first token. In all written languages, the development of reading includes: reorganization of already existing structures to create new neural networks of learning; the ability to specialize the working groups of neurons within these structures for the representation of information; and automatism, the ability of these groups of neurons and learning networks to seek out and connect this information almost involuntarily. If we use these design principles to analyze reading disorders, a number of potential underlying sources of dyslexia emerge: 1) a developmental (and possibly genetic) failure in the structures responsible for language or vision, these structures; 2) inability to reach the level of automatism - when looking for representations within certain specialized working groups and / or in connections between these structures; 3) physical defects in the connections between two or more such structures; 4) reorganization of a neural network that is not usually used for a particular writing system. Some causes of reading disorders can be found in all writing systems, while others are relatively specific to one.

Some causes of reading disorders can be found in all writing systems, while others are relatively specific to one.

Over the past 120 years of the uneven history of dyslexia research, hypotheses have been put forward that address each of these four types of failure. In fact, it is possible to streamline this history if the existing hypotheses are organized in accordance with the principles outlined above. More importantly, if we organize all the available information from the different theories of dyslexia according to how the brain works, we can get a clearer picture of how studying reading disorders will lead to a more complete and accurate.

Principle 1: Failure in the old structures

Most of the theories of dyslexia that emerged in the 20th century associated it with one of the old structures in the neural network, the visual system. The first term for what we now call dyslexia was "alexia" (word-blindness). This term first appeared in the work of the German researcher Adolf Kussmaul in the 1870s. Childhood dyslexia came to be called congenital alexia based, on the one hand, on the work of Kussmaul, and on the other hand, on the strange case of Monsieur X, a French businessman and amateur musician, who woke up one day and found himself unable to read almost a single word. The French neurologist Joseph-Jules Dejerine discovered that Monsieur X could indeed no longer read words, name colors or read music, despite the fact that his vision was not damaged. A few years later, Monsieur X suffered a stroke that completely destroyed his ability to read and write, and also caused an imminent death.

Childhood dyslexia came to be called congenital alexia based, on the one hand, on the work of Kussmaul, and on the other hand, on the strange case of Monsieur X, a French businessman and amateur musician, who woke up one day and found himself unable to read almost a single word. The French neurologist Joseph-Jules Dejerine discovered that Monsieur X could indeed no longer read words, name colors or read music, despite the fact that his vision was not damaged. A few years later, Monsieur X suffered a stroke that completely destroyed his ability to read and write, and also caused an imminent death.

Monsieur X's autopsy showed two separate strokes, each damaging discrete areas of the brain. Dejerine used this information as the basis for a new theory about reading and the brain. The first stroke caused damage in the left visual area and in the back of the corpus callosum, the group of fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain (see Figure 7.2). As a result, Monsieur X's visual areas were "disconnected", allowing him to see with his right hemisphere, but preventing him from relating what he saw to either the language areas of the left hemisphere or to the damaged left visual area. This is what caused his initial inability to read. The second stroke, which caused a complete loss of reading and writing, damaged the area of the angular gyrus. Dejerine's case of "classic dyslexia" marked the beginning of research into acquired dyslexia and became the basis for the first hypotheses regarding the role of vision and the importance of intracerebral connections.

This is what caused his initial inability to read. The second stroke, which caused a complete loss of reading and writing, damaged the area of the angular gyrus. Dejerine's case of "classic dyslexia" marked the beginning of research into acquired dyslexia and became the basis for the first hypotheses regarding the role of vision and the importance of intracerebral connections.

In the 20th century, neuroscientist Norman Geschwind interpreted Dejerine's case as an example of "disconnection syndrome," where different parts of the brain needed to perform a specific function (such as writing language) are "cut off" from each other, causing the function to fail. Thus, Monsieur X's case actually reflects two different putative causes of dyslexia: damage to one of the old structures, that is, the visual system, and broken connections in the reading network.

Another early logical explanation for reading disorders is problems in the auditory system (see figure 7.3). At 19In 21, reading researcher Lucy Fields received evidence that children with reading problems are unable to form acoustic images (kind of like our phonemic representations) of the sounds represented by letters. In 1944, the neurologist and psychiatrist Paul Schilder astutely described a person with reading disabilities, noting that he was unable to relate letters to the sounds they represent, and also to decompose the spoken word into its constituent sounds. Schilder's discoveries and Fields' earlier work on acoustic imagery are the forerunners of one of the most important areas of work on the problems of dyslexia: the study of the child's inability to process phonemes in words.

In 1944, the neurologist and psychiatrist Paul Schilder astutely described a person with reading disabilities, noting that he was unable to relate letters to the sounds they represent, and also to decompose the spoken word into its constituent sounds. Schilder's discoveries and Fields' earlier work on acoustic imagery are the forerunners of one of the most important areas of work on the problems of dyslexia: the study of the child's inability to process phonemes in words.

In the early 1970s, mainly based on the intellectual influence of the linguist Noam Chomsky, the emerging psycholinguistics (the study of the psychology of language) set a new direction in the study of reading. The goal of early psycholinguists was nothing less than a systemic understanding of the relationships between speech, language, reading development, and reading disorders. Their theory that dyslexia is a language disorder disproved earlier theories that focused primarily on perceptual and visual impairments. Psycholinguistic research by psychologists Isabelle Lieberman and Don Shankweiler is thought provoking. They studied a group of deaf children and found that only a few of them could read well and yet differed from all other readers by having phonological representations of the sounds that make up words. As interpreted by Lieberman and Schenkweiler, these and other results indicate that reading is more dependent on phonological analysis and comprehension skills that require linguistic experience (see Figure 7.4) than on the sensory nature of the auditory perception of speech sounds.

Psycholinguistic research by psychologists Isabelle Lieberman and Don Shankweiler is thought provoking. They studied a group of deaf children and found that only a few of them could read well and yet differed from all other readers by having phonological representations of the sounds that make up words. As interpreted by Lieberman and Schenkweiler, these and other results indicate that reading is more dependent on phonological analysis and comprehension skills that require linguistic experience (see Figure 7.4) than on the sensory nature of the auditory perception of speech sounds.

The work of experimental psychologist Frank Vellutino in the field of reading disorders put an end to researchers' attempts to explain the problems that arise here as defects in perceptual structures. Vellutino and colleagues have shown that the most common perceptual problems in dyslexia (the well-known "visual" shifters, such as reading b for d and p for q) are the result not of a perceptual deficit, but of the child's inability to find the right verbal labels for these sounds. In his in-depth research, Vellutino first showed children with reading problems a few typical pairs of flippers and then asked them to either draw letters (a non-verbal task involving visual processing) or say them (a verbal task). The children drew the letters very accurately, but gave predominantly incorrect names, indicating a language-related source of failure.

In his in-depth research, Vellutino first showed children with reading problems a few typical pairs of flippers and then asked them to either draw letters (a non-verbal task involving visual processing) or say them (a verbal task). The children drew the letters very accurately, but gave predominantly incorrect names, indicating a language-related source of failure.

There are now hundreds of phonological studies demonstrating that many children with reading disabilities do not perceive, segment and manipulate individual syllables and phonemes in the same way that intermediate readers do. This discovery had far-reaching and important consequences. Children who do not understand that the word bat (“bat”) has three sounds that can be separated from each other will have difficulty if the teacher starts the lesson with good intentions by saying: “Pronounce this word so that separate sounds are heard: /b/ - /a/ - /t/". They cannot quickly isolate and then pronounce a phoneme from the beginning or end of a word (especially from the middle), and their awareness of rhyme patterns - to decide whether words like fat (“fat”) and rat (“rat”) rhyme, - develops much more slowly. More importantly, we now know that if such children have to deduce correspondence rules between letters and sounds unaided, they have the greatest difficulty in learning to read.

More importantly, we now know that if such children have to deduce correspondence rules between letters and sounds unaided, they have the greatest difficulty in learning to read.

Undoubtedly, the most important contribution of phonological explanations of dyslexia is that they have influenced primary education and correctional programs. Joseph Thorgesen, Richard Wagner, and colleagues at Florida State University have shown that programs that systematically and effectively teach phoneme awareness and grapheme-phoneme correspondences to young readers achieve significantly greater success in correcting reading disorders than other programs. The cabinets of published research proving the effectiveness of phoneme awareness and step-by-step decoding training for basic reading skills alone could take up an entire wall in a library. Thus, phonological studies represent the most studied structural hypothesis of reading disorders.

Other—less explored but no less important—structural hypotheses cover executive processes in the frontal lobes (which involve the organization of attention, memory, and monitoring comprehension) or the posterior cerebellum (which deal with many aspects of temporal distribution, language processes, and communication). between motor coordination and thinking). Any of these structural hypotheses is very important. As Virginia Berninger of the University of Washington shows, some children's reading problems are caused by primary elements of executive processes, such as attention and memory; in others, reading disorders are accompanied by problems concentrating. A number of British researchers suggest that this may be due, at least in some children, to cerebellar dysfunction.

Let's analyze the overall picture that emerges as a result of considering all structural hypotheses. In the early and mid-20th century, well-intentioned scientists tended to find one area of dysfunction and prove that it was the root cause of most reading disorders. The story of the blind wise men and the elephant (although this is perhaps an overused metaphor for dyslexia research) is by far the best description of most of this research.

The story of the blind wise men and the elephant (although this is perhaps an overused metaphor for dyslexia research) is by far the best description of most of this research.

Not surprisingly, many theorists have given their own explanation of reading disorders a new name. Let's see what happens if we place all the hypotheses of violations created at different times at the procedural-structural level, approximately like areas on a map of the human brain (see Fig. 7.5). Here you go: the sum of these hypotheses looks like a good approximation of the main parts of the universal reading system. This is another way of saying that many of the sources of dyslexia, according to this cumulative hypothesis, correspond to the basic structures of the brain that can read.

You can pre-order the book here

More texts about psychology, relationships, children and education are in our telegram channel “Project Snob – Personal” Join us

talks about your intelligence - and that's why / Sudo Null IT News If you love to read as much as I do, then going to a bookstore is like going to a candy store for a child.

Treasures of human wisdom lined up on the shelves, revelations that each of the authors has been polishing for years. It's all here, right at your fingertips, concentrated in a format that makes you want to curl up and under the covers.

Naturally, you pull out a credit card or press the "Buy" button.

And the books are piling up. On your shelves. In the bedroom. In car. Maybe even in the bathroom.

The most selfless bibliophiles are looking for a place where no one previously guessed to put books:

Source: http://bit.ly/2JRrqbk

And as the books pile up, so does your greed. No, not the desire to read all the books you buy. Thirst not to finish reading those books that you have started.

If the next maxim is about you, then I have to please you.

"Even if you don't have time to read them all, it's good for you to overfill your bookshelves or reader."

— Jessica Stillman

In this article, I will explain why, for those who really take the time to read and learn to learn, unread books scattered around the house just indicate high intelligence, and not its absence.

Transferred to Alconost

Not only are heaps of unread books scattered everywhere - this is the handwriting of a smart guy; such a person will make you an excellent company. I finally came to terms with my own greed when I got to know the reading habits of brilliant entrepreneurs in detail and interviewed my most successful friends in my own way. Most of them read only 20-40 percent of the books they buy. Many of them can read 10 books at a time. In fact, one of the most eager readers in the tech beau monde, a self-made billionaire entrepreneur, estimates that...

of them. I end up reading 1-2 books a week.”

— Patrick Collison

What is going on?

Studying the reading habits of others, coupled with the tremendous changes in our society, dominated by knowledge, I became convinced that our new times dictate new ways of searching, filtering, consuming and applying knowledge - the only way to change lives for the better.

The explosion of information in a variety of media and formats, new research tools to help us find the best information, and apps to help us absorb it not only encourage us to read more. They encourage us to read in a new way.

A big part of my reading life is the old fashioned way of getting into art, but when I read to learn rather than to relax, I use a lot of tricks and strategies to figure out which books to buy and how to read them.

Here are some of the smartest non-fiction reading hacks I've picked up from world-class entrepreneurs.

Life hack one: Considering books as an experiment

My friend Emerson Spartz, a successful serial entrepreneur and investor who has read thousands of books, convincingly demonstrates that buying a book is an experiment. The costs are small: you have to pay $ 15 and spend a little time. However, if you're lucky, the book can change your life. The rates are very good!

It is known that the more "smart" experiments you do, the higher your chances of finding a breakthrough experiment that will change everything. The most celebrated scientists and the most successful companies are usually the ones that experiment the most.

The most celebrated scientists and the most successful companies are usually the ones that experiment the most.

My experience is that you need to study, buy and research 10 books before you find the one that, in my opinion, contains breakthrough knowledge.

A good experimenter is willing to take some losses. Thus: every time you get a book, and it turns out to be nonsense, you are still one step closer to the book that will change your life.

Life hack two: Practice fractal reading

We, as a knowledge society, have reached a tipping point. The metadata generated by books (ie, author's interviews, author's presentations, book abstracts, reviews, citations, first and last chapters, etc.) are often as valuable as the book itself.

Why?

- All this is free. This information allows you to try many more books before you buy. Consequently, in every "experiment" with the purchase of a book, our chances of success increase.

- This is multimedia. All of this information is available in text, audio, and video format, making it a better fit for your daily routine (for example, you can read it while traveling back and forth or at work).

- In this case, we have a high signal-to-noise ratio. In the abbreviated format, all the water is removed, the main ideas are presented immediately.

Just as a book is the quintessence of an author's best ideas, metadata is the quintessence of a book.

This is why I call this approach to reading "fractal"; because fractals are figures whose structure reveals identical patterns regardless of scale.

We have reached a point where it may be more useful and convenient to read non-fiction in the "fractal" mode, rather than the entire book from cover to cover. For example, I can estimate that I spend 50% of the purposeful study time on fractal reading, and not on deep sequential reading. This makes it easier for me to choose books to dive into and also to recognize the most important and essential sections of the book so that I can jump directly to them. In most cases, a fractal reading of five books will be more valuable and exciting for me than studying one book from cover to cover.

This makes it easier for me to choose books to dive into and also to recognize the most important and essential sections of the book so that I can jump directly to them. In most cases, a fractal reading of five books will be more valuable and exciting for me than studying one book from cover to cover.

Here's how to do it:

- Read 2-3 book summaries (google search). For almost any book, you can find several annotations, which often contain the most sensible information from the book (20% of the ideas containing 80% of its value). Let me explain: here I mean only non-fiction books; This rule, of course, does not apply to fiction.

- Listening to the author's interview (podcasts, Google). The interviews are engaging, and the facilitator takes over your job, asking the author the most essential and intriguing questions that emerge from the book.

- Watching the author's presentation (TED, Google or university lecture). When an author is forced to pack a 200-page book into a 20-minute lecture, he shares his biggest ideas, merging them into an optimal plot.

- Read the most helpful 1-star, 2-star, 3-star, 4-star and 5-star reviews (Amazon). Amazon helps everyone quickly sort through the most thoughtful reviews, from readers who fell in love with her to those who hated her.

- Reading the first and last chapters of the book. The first and last chapters of the book often contain the most valuable information (of course, this principle does not work if you want to plunge headlong into the novel). In addition, the first and last paragraphs of each chapter contain its most valuable ideas. Given that Google Books has free e-book samples and Amazon has a Look Inside feature, you can often get the first and last chapter of a book for free.

Life hack three: Unread books should remind us how little we really know

Intellectual humility is so valuable not only because it is a virtue. It is valuable because it allows us to more realistically conceptualize ourselves and our place in the world, and this helps us live more efficiently and harmoniously. For example, humility helps us make better decisions and inspires us to study and learn.

For example, humility helps us make better decisions and inspires us to study and learn.

This is how I see it: there were billions of people in the world who accumulated knowledge and documented it for thousands of years. The knowledge of one person compared to the collective knowledge of all mankind is only a drop in the ocean. And this sea is expanding at an unfathomable rate. Most of the scientists who have ever lived in the world are our contemporaries!

Moreover, if we talk about all the knowledge that humanity is able to obtain, and about what we have already managed to discover, then the first is like the whole Universe, and the second is like a grain of sand. So, here are three levels for cultivating our humility:

- Individual knowledge

- Modern knowledge of mankind

- All potential knowledge

However, at the level of everyday tangible experience, it seems that we know much more than we really do. When all is well, it seems to many that they have comprehended the notorious "meaning of life." It's like we're at the end of a cycle instead of the beginning. It’s just that we are constantly reminded of the already known and rarely (if ever) of the unknown.

When all is well, it seems to many that they have comprehended the notorious "meaning of life." It's like we're at the end of a cycle instead of the beginning. It’s just that we are constantly reminded of the already known and rarely (if ever) of the unknown.

Naturally, conceptually, we can realize that we know far from everything, but we do not physically feel it. I was reminded of this recently when I spent two hours touring two of Princeton's six libraries. I happened to pass a space the size of 10 football fields, filled with books and scientific journals. On the one hand, I was inspired by looking at all this and realizing that all this can be studied. On the other hand, he experienced extreme humility. Libraries have helped me to realize how little I currently know, and to understand that even if I spent my whole life only reading, I would learn a small fraction of what is collected in them.

Collecting anti-library , that is, accumulating unread books at home, one can experience similar feelings. Nassim Taleb, a successful investor and best-selling author, brilliantly describes the value of the anti-library in his book Black Swan :

Nassim Taleb, a successful investor and best-selling author, brilliantly describes the value of the anti-library in his book Black Swan :

“A personal library is not an image accessory, but a working tool. Read books are far less important than unread ones. The library should contain as much of the unknown as your finances, mortgages, and the current difficult real estate market will allow you to fit into it. As the years go by, your knowledge and your library will grow, and the growing ranks of unread books will begin to look at you menacingly. In fact, the wider your horizons, the more shelves you have of unread books. Let's call this collection of unread books the anti-library."

Not only Taleb is of this opinion. The Italian writer and philosopher Umberto Eco collected over 30,000 books. Thomas Jefferson collected 6,000 books, thus, at that time, his library was the largest in the country. Jay Walker, the founder of Priceline. com, amassed such a huge library that he later built his house around it. Thomas Edison set up his desk in the center of his own three-story library. Bill Gates has many rooms in his house, but his favorite is his own colossal 2,100-square-foot library.

com, amassed such a huge library that he later built his house around it. Thomas Edison set up his desk in the center of his own three-story library. Bill Gates has many rooms in his house, but his favorite is his own colossal 2,100-square-foot library.

Personal Library of Jay Waker, founder Priceline.com

Tomasa Edison library

Personal library Bill Gates

Lifehack Fourth: Cape good books, Read the Great 9001 9005 In one excellent podcast from the Knowledge Project, Patrick Collison, founder of the Stripe project, self-made billionaire, makes the following thesis:

only known. However, as soon as you find another book that seems more interesting or more important, the current handbook should not hesitate to discard ... any other algorithm will cause your reading to get worse and worse over time.

In other words, remember what you were taught and do exactly the opposite. Instead of trying hard to “finish off” any book you start, allow yourself to simply put this book aside - but only if you find a more valuable one. Life is too short and there are simply too many good books in the world. On the other hand, be careful and try not to go too far - that is, not to reject great books just because you got some new with a catchy title.

Instead of trying hard to “finish off” any book you start, allow yourself to simply put this book aside - but only if you find a more valuable one. Life is too short and there are simply too many good books in the world. On the other hand, be careful and try not to go too far - that is, not to reject great books just because you got some new with a catchy title.

How do you know if you're jumping randomly from book to book? This is where fractal reading comes in handy. If the book's meta-information didn't grab your attention, then it's unlikely that the whole book will be enough.

Life hack five: Use the books you read to free up space in your head for great ideas to collide

It is known that targeted advertising is effective. The recipient perceives it both consciously and subconsciously. The same applies to those books that we correctly place in the existing context.

My mentor, business partner, and friend Eben Pagan compares a bookshelf to a playlist of timeless intellectual masterpieces:

“The most important book on your shelf is the one you haven't read yet.If you have a promising book, it may not be time to read it yet. Maybe you will ripen to it in a year, or maybe in ten years. However, if you spot a book at the right moment, you will be interested in it and take it off the shelf.”

Patrick Collison talks along the same lines:

“Another skill that I find very valuable is simply putting a book away. When someone recommends a book to me, I can often get myself a copy... and put it down. So, the books are in my kitchen. They lie in the bedroom. They are just scattered all over the place.Moreover, it is surprisingly common when someone else recommends you a book, or some aspect of it, and it is still at hand. In sight. And you'll think, "Oh, really, you need to get to know this thing."

Or learn about the book's importance in some other way. Read in the article. You will begin to realize its zest, or the question posed in it, or something else.

So one of the reasons why I continue to appreciate paper books is that the book creates a kind of idea space for you, in which fruitful collisions occur between such ideas more often.

Life hack six: read books like magazines

"Journal" reading of a book is a powerful metaphor. Picking up a magazine, we do not feel embarrassed if we skip some pages in it, or scroll diagonally in 5 minutes. On the contrary, we will scan the magazine in such a way as to find the most interesting and important articles, and then, having found them, we will carefully and slowly read them. This approach is very powerful on several levels:

- Helps you find the most important information to study in depth.

- Helps slow down so we can get the most out of the information we decide to study in depth.

- Makes it easier to read, making it easier for us to stay consistent.

Let's face it, it's not as easy to focus for long periods of time as it used to be. Yes, it would be great to sit and read for hours without distraction, but if this is not done properly, then the benefit is zero.

Yes, it would be great to sit and read for hours without distraction, but if this is not done properly, then the benefit is zero.

Avid reader and famed technology investor and entrepreneur Naval Ravikant has pioneered a reading system that helps to put even shortened periods of acute attention to good use.

Ravikant noticed that among the most valuable books there are a lot of old sources that form the basis for other books. He describes the value of these books in one of the Tim Ferriss podcast series:

“The older the problem, the older the solution. When it comes to old topics, such as how to keep your body healthy, stay calm and peaceful, what value systems are good, how to arrange a family ... for such problems, the old solutions are perhaps better than the new ones, as they have stood the test of time. Any book that has existed for 2,000 years is "filtered" by a lot of people."

However, Ravikant notes the important challenge of reading this kind of book:

“…but I knew it was a very difficult problem, because my brain is used to Facebook, Twitter and other sources where information is given by the teaspoon.So I used this tactic when I started thinking of books as one-off blog articles or miniature tweets or Facebook posts. I don't feel any obligation to finish the book. Now, when someone points me to a book, I buy it. At any given time, I read between 10 and 20 books. I flip through them, as soon as the book starts to get boring, I skip the uninteresting. Sometimes I start reading a book from the middle, because a paragraph caught my attention, and I continue from there. I don't feel the need to read at all. If at some point it seems to me that the book is boring due to clearly erroneous fragments (and I can no longer trust the rest of the information that is presented in it), I simply delete them and no longer remember them. Now I treat books like others - any other easy information that can be found on the Internet. All of a sudden, books are back in my circle of reading.”

Finally, it's not about how many books you finish reading

It is difficult to distinguish between just a book plush and a smart reader, if you just visit their homes. Both of them will have books all over the place. However, this similarity is superficial. In fact, there are three key differences between plushkin and a smart reader.

Both of them will have books all over the place. However, this similarity is superficial. In fact, there are three key differences between plushkin and a smart reader.

- Smart readers have a well-established learning ritual. I recommend sticking to the 5-hour rule: spend about an hour a day reading, following the example of many leading entrepreneurs and leaders. Today I devote 4-5 hours a day to systematic learning, while at the same time managing my company and raising two children.

- Smart reader learns to learn. In other words, he learns to make the best use of the time devoted to reading. I wrote a free email course to help you master mental models, one of the most important skills to help you learn faster and better. This course explains the models that billionaire investors use to make business and investment decisions. This is an arsenal that you can begin to apply in life and in business right now. You will also learn how to incorporate these patterns naturally into your daily life.

- Smart readers continue to act until they achieve the desired result. The value of theoretical knowledge lies in the ability to apply it in practice.

If you consistently adhere to these three principles, then the time will soon come to say goodbye to guilt. You don't have to read every book on your shelf. And when you take a book off the shelf, you don't have to read it to the end.

Plyushkin is proud of how many books he has, and an intelligent reader is proud of how much he was able to extract from his books.

About the translator

The article was translated by Alconost.

Alconost localizes games, applications and websites into 70 languages. Native translators, linguistic testing, cloud platform with API, continuous localization, project managers 24/7, any format of string resources.

We also make promotional and educational videos - for websites, selling, image, advertising, training, teasers, explainers, trailers for Google Play and App Store.