Literacy development definition

Literacy Development in Children | Maryville Online

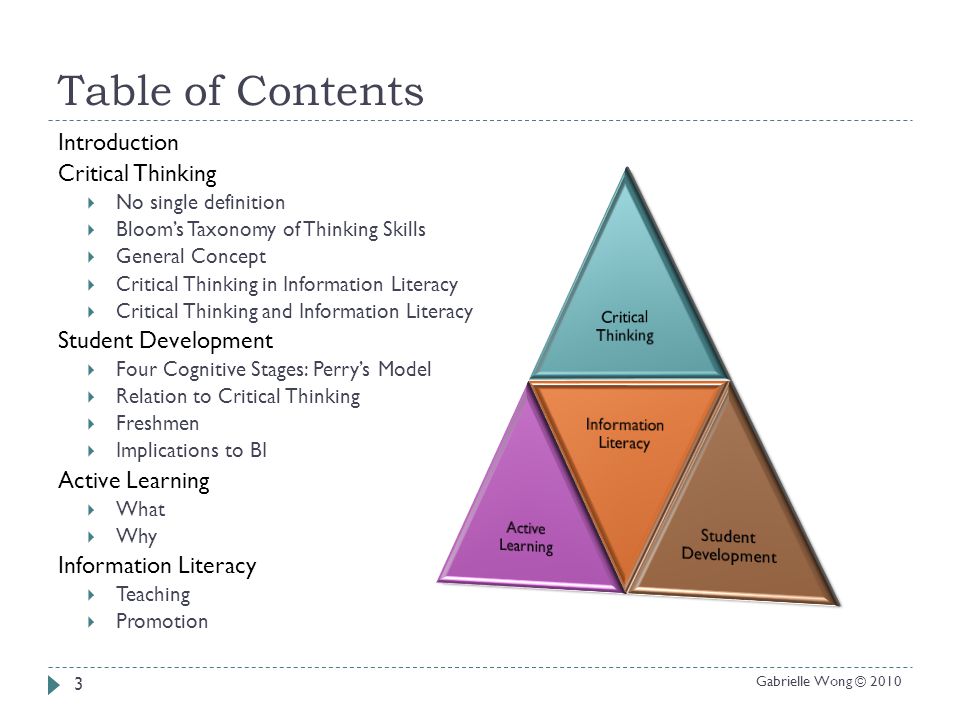

Tables of Contents

- What Is Literacy Development?

- Language and Literacy Development in Children

- 5 Literacy Development Stages

- Literacy Development in Early Childhood

- Early Literacy Development Stages in Children

The benefits of physical activity for a person’s health and longevity are well documented. However, not everyone is aware of the many health benefits of the most common form of mental exercise: reading.

- Reading stimulates brain development in children and adults and promotes social and emotional skills that contribute to healthy lifestyles.

- Reading reduces stress and symptoms of depression; it lowers readers’ blood pressure and pulse rate, and it reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and late-life cognitive decline.

- Reading fiction enhances emotional intelligence by teaching how to perceive and understand other people’s feelings; it also improves memory and the ability to concentrate.

For children, literacy development provides benefits that begin immediately and last a lifetime.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) found that instructing parents on the benefits of reading aloud to their children and providing an age-appropriate and a culturally appropriate book to a child at each health supervision visit from birth to 5 years improves the child’s language development and home environment. The improvement was greatest among children at socioeconomic risk.

- Research published in the journal Pediatrics links language exposure in children ages 12 months to 24 months to higher language skills and IQ scores through age 14.

- A study reported in the Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics determined that children who are read to regularly in their first five years of life are exposed to 1.4 million more words than children who are never read to.

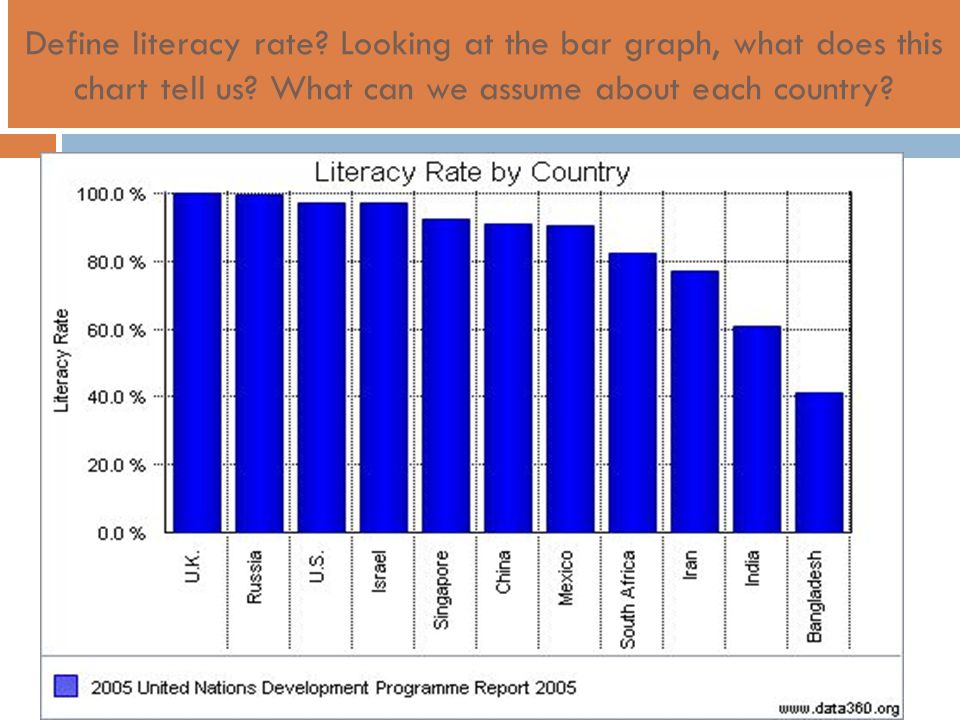

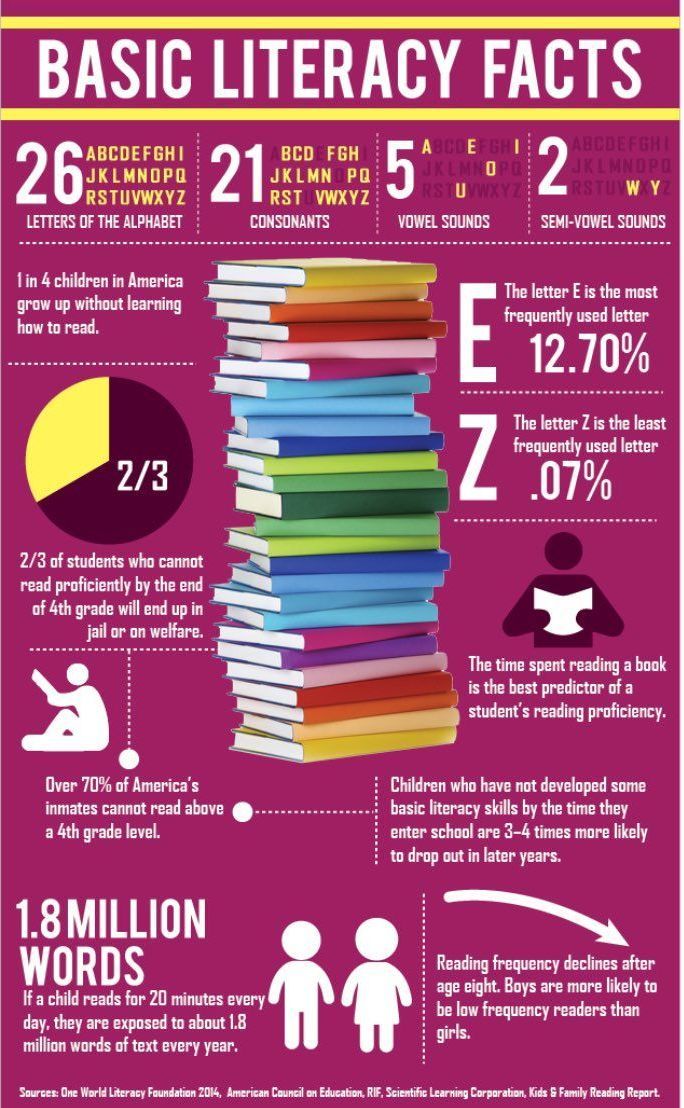

The importance of early literacy development to a child’s success in school and life can’t be understated. Even though the literacy rate in the U.S. is 99%, researchers estimate that 43 million U.S. adults have low literacy skills that impair their cognitive abilities. Introducing children to books and reading from their first months of life prepares them to succeed in school while also strengthening family bonds and promoting children’s health and well-being for a lifetime.

Even though the literacy rate in the U.S. is 99%, researchers estimate that 43 million U.S. adults have low literacy skills that impair their cognitive abilities. Introducing children to books and reading from their first months of life prepares them to succeed in school while also strengthening family bonds and promoting children’s health and well-being for a lifetime.

Back To Top

Crayons, Pencils, and Keyboards; Martin-Pitt Partnership for Children; and Nationwide Children’s Hospital report these benefits of language and literacy: They build confidence and self-esteem, encourage independent learning, enhance cognitive ability, strengthen brain function, improve attention span, and enrich communication skills.

Back To Top

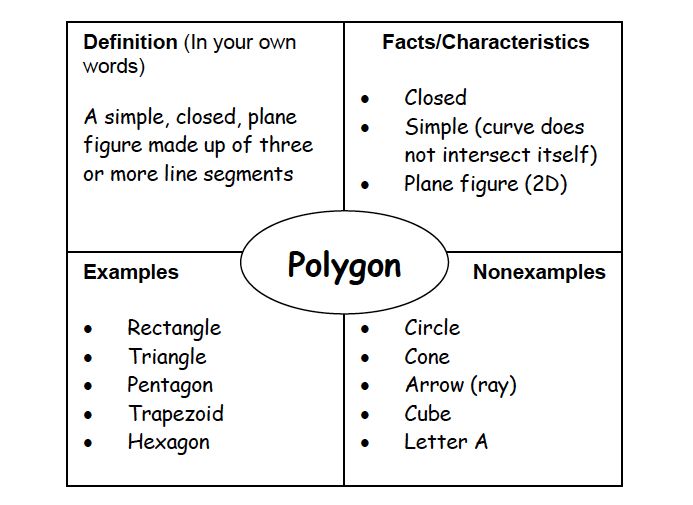

What Is Literacy Development?

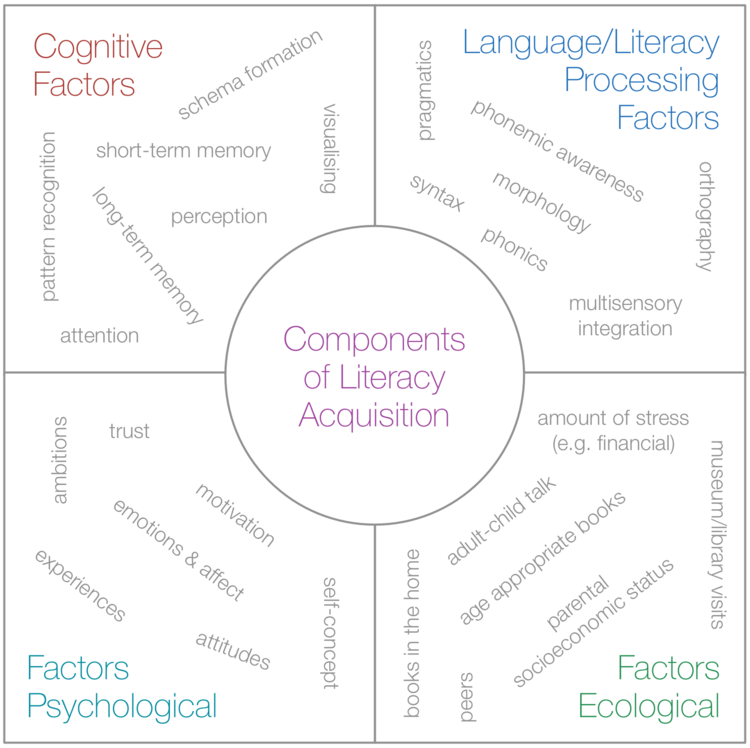

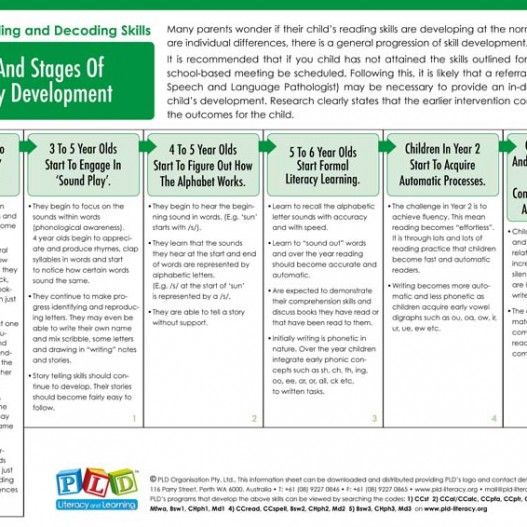

Literacy development is the process of learning words, sounds, and language. The acquisition of early literacy skills begins in a child’s first year, when infants begin to discriminate, encode, and manipulate the sound structures of language, an ability called phonological awareness.

- Before their first birthday, children begin to store phonemes, or basic units of meaning in a language, in their memory.

- In subsequent years, they learn how to manipulate and combine phonemes into meaningful language units by applying morphology (words) and syntax (grammar).

- They’re able to retrieve and produce words in ways that express ideas, and they can coordinate visual and motor processes (speaking written words).

It’s important to assess a child’s language skills at an early age, because delays in literacy development could indicate a language or reading disorder. Research has shown that languages with consistent sound-to-letter correspondences, or orthographic consistency, are easier for children to learn.

- Languages with regular orthographies, such as Spanish and Czech, tend to be easier for young children to learn than languages with inconsistent orthographies, such as English, Danish, and French.

- Primary school children acquiring languages with opaque orthographies tend to make more errors than children learning a language with transparent orthographies.

- A language’s orthographic transparency affects the ability to diagnose dyslexia, for example: In languages with transparent orthographies, the inability to quickly retrieve and produce words, or rapid automatic naming, is more predictive of dyslexia than in languages with opaque orthographies, in which lack of phonological awareness is a better indicator of potential dyslexia.

Encouraging Communication and Reading Skills

Reading-related activities in the child’s home are key to early literacy development. These activities include joint reading, drawing, singing, storytelling, game playing, and rhyming.

- Joint reading entails children and their parents or caregivers taking turns reading parts of the book. The children are asked to describe what they’re thinking as they read.

- Drawing not only helps develop a child’s motor skills but also encourages creative thinking and lays the foundation for early writing.

It also helps children gain cognitive understanding of complex concepts and builds their attention span.

It also helps children gain cognitive understanding of complex concepts and builds their attention span. - Singing makes it easier for children to identify small sounds in words and build their vocabulary. A song’s rhyme structure teaches similarities between words, and singing helps develop a child’s listening skills.

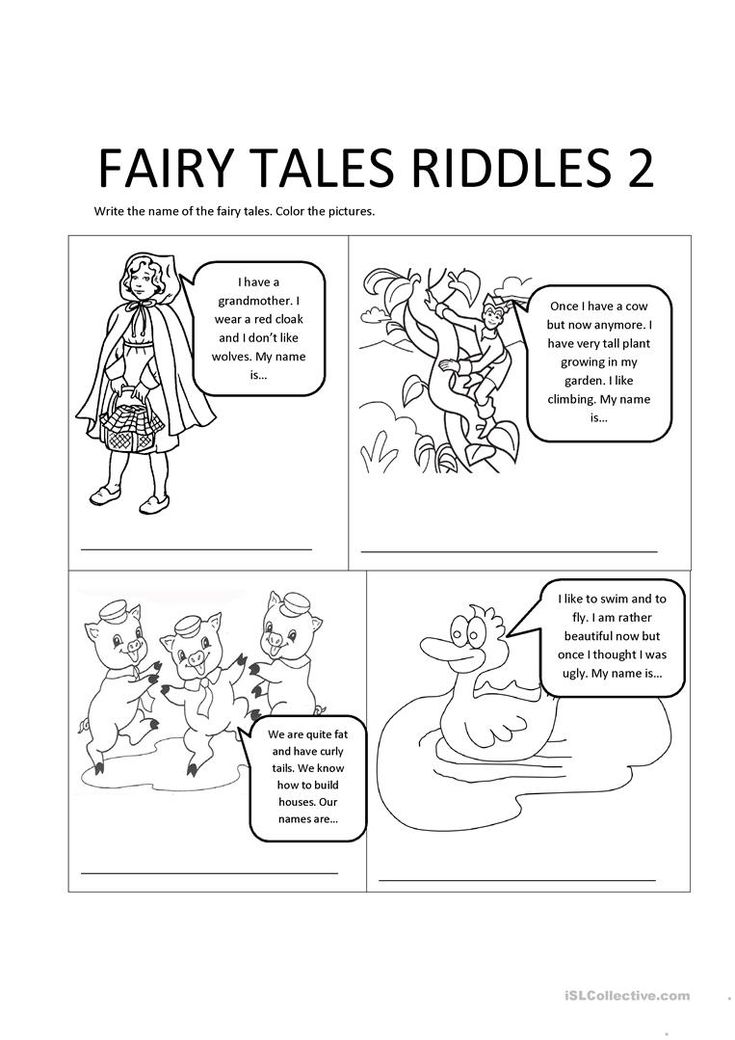

- Storytelling sparks a child’s imagination in addition to teaching sounds, words, and grammar. Children learn to focus and concentrate while also picking up social and communication skills.

- Game playing presents an opportunity for children to learn language and reading skills while engaged in favorite activities, such as using props and objects to act out scenarios, role-playing, and imagining new experiences.

- Rhyming is both enjoyable and memorable for young children while also teaching phonemic awareness and fluency in reading and speaking. In addition to helping children learn the fundamental patterns in language, rhyming helps build their confidence and instills in them a joy of reading.

Using Childhood Literacy to Treat Communication Disorders

While nearly all children experience problems with a few language sounds, words, or syntax, some children struggle to reach literacy milestones that are common for their age group. These are among the language problems that young children may encounter:

- Receptive language, or understanding what others are saying. This may be due to a problem hearing or an inability to understand the meaning of words.

- Expressive language, or using language to communicate thoughts. The child may not possess sufficient vocabulary to express themselves, not understand how to put the words together, or may know the words but not how to use them correctly.

- Speech disorders include difficulty forming specific sounds and words or problems speaking smoothly, such as stuttering.

- Language delay occurs when the child takes longer than usual to comprehend language and speak.

- Language disorders include aphasia (difficulty speaking and understanding due to a brain injury or atypical brain function) and auditory processing disorder (problems in comprehending the sounds the ear sends to the brain).

Some language development problems relate to hearing loss, so children experiencing language problems should have their hearing checked. Speech language pathologists are able to help children overcome language learning difficulties; they also help parents, caregivers, and teachers overcome language learning difficulties in children. Children under the age of 3 who appear to have problems with literacy development may qualify for state early intervention programs that help them develop cognitive, communication, and other skills.

Back To Top

Language and Literacy Development in Children

How children develop language skills and become literate are two separate but closely related processes:

- Language development occurs as the child’s ability to understand and use language emerges.

Receptive language skills are the ability to listen and understand, while expressive language skills relate to the child’s use of language to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings.

Receptive language skills are the ability to listen and understand, while expressive language skills relate to the child’s use of language to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings. - Emerging literacy is the child’s initial use of language and communication skills as the foundation for reading and writing. Infants and toddlers begin to apply their new receptive, expressive, and vocabulary skills, while preschoolers begin to distinguish the differences and similarities of spoken and written language.

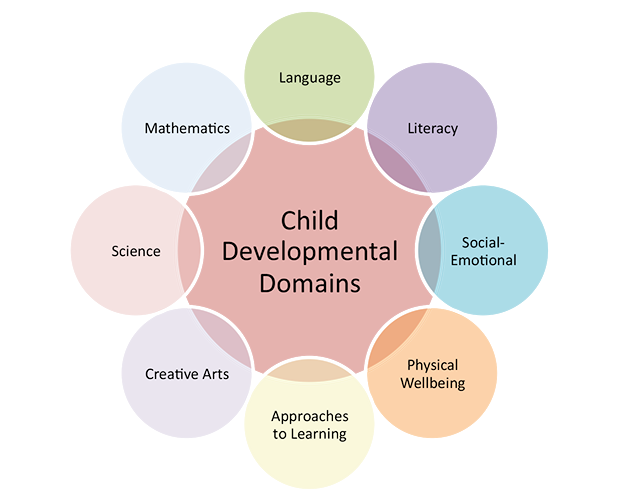

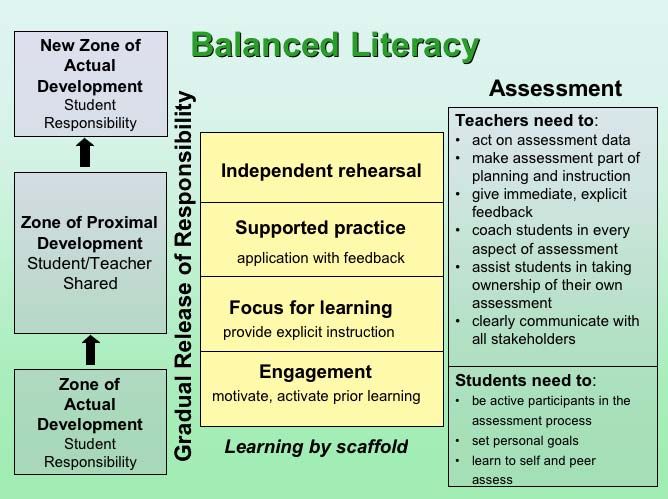

These are the components of language and literacy development programs for young children:

At this stage, the child focuses on communication and language from others, understanding, and responding. The four aspects of attending and understanding are know, see, do, and improve:

- Know: For infants and toddlers, the parents or caregivers respond to their verbal and nonverbal communication with words and facial expressions to establish a back-and-forth exchange.

Toddlers are encouraged to respond to questions and short comments. For preschool children, communication expands from simple words and short phrases to more complex words and sentences.

Toddlers are encouraged to respond to questions and short comments. For preschool children, communication expands from simple words and short phrases to more complex words and sentences. - See: For infants and toddlers, the caregivers describe what they’re doing and what the infants or toddlers are doing and observe their response to indicate whether the infants or toddlers understand. For preschool children, the caregivers describe what’s going to happen and give the children an opportunity to communicate and respond.

- Do: For infants and toddlers, the caregivers narrate what’s happening during an activity and give the children an opportunity to participate, focusing on the things that draw the children’s attention. For preschool children, the caregivers engage them in a conversation about what’s happening and help them pick up the cues of a give-and-take exchange, such as waiting for their turn to speak.

- Improve: For infants and toddlers, the caregivers individualize the responses to their verbal and nonverbal communication and react using facial expressions, gestures, signs, and words when the children indicate that they understand.

For preschool children, the caregivers initiate conversations with them and let them know they’re valued conversation partners. The children are encouraged to strike up conversations with other children.

For preschool children, the caregivers initiate conversations with them and let them know they’re valued conversation partners. The children are encouraged to strike up conversations with other children.

Communicating and Speaking

Early communication efforts by infants and toddlers focus on what the child wants or needs through facial expressions, gestures, and verbalization. The child engages with others using increasingly complex language and initiates interactions with others verbally and nonverbally to learn and gain information. Preschoolers learn to vary the amount of information they communicate as dictated by the situation. They begin to understand, follow, and comply with the rules of conversation and social interaction.

Vocabulary

Through their interactions with others, infants and toddlers learn new words and begin to use them to communicate and respond. The parent or caregiver shows an object or action and repeats its name, and also demonstrates words that express feelings and desires. Preschool children learn how to use a wider range of words in various settings and with shades of meaning in specific situations. They also begin to categorize words and understand relationships between words. When engaging children in conversation, the person takes every opportunity to introduce new words to the child that relate to the topic and setting.

Preschool children learn how to use a wider range of words in various settings and with shades of meaning in specific situations. They also begin to categorize words and understand relationships between words. When engaging children in conversation, the person takes every opportunity to introduce new words to the child that relate to the topic and setting.

Emergent Literacy

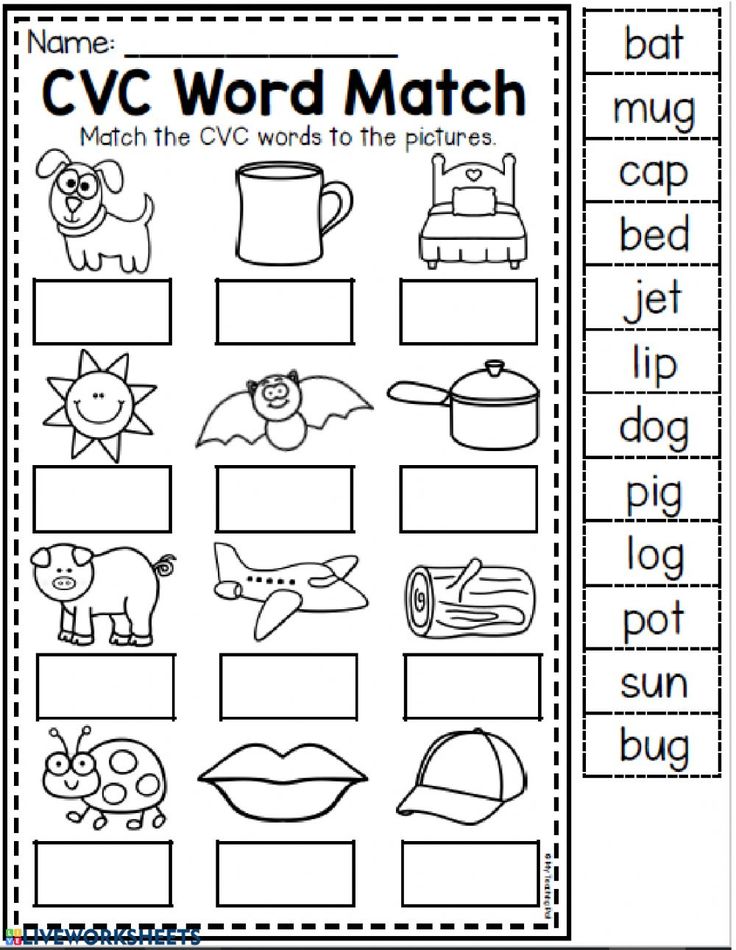

The earliest stages of literacy for infants and toddlers is their repetition and use of rhymes, phrases, and song refrains. They begin to physically handle books and understand that they’re the source of stories and information. Children start to recognize pictures, symbols, signs, and basic words; understand what pictures and stories mean; and make marks that represent objects and actions.

Phonological Awareness

Preschoolers begin to understand that language is composed of discrete sound elements that have their own meaning. Singing songs, playing word games, and reading stories and poetry aloud help make children aware of phonological distinctions in the words, phrases, and sentences they’re using. Through wordplay, such as being called by name with the separate sounds of the name highlighted, children become aware of the individual sounds that make up words.

Through wordplay, such as being called by name with the separate sounds of the name highlighted, children become aware of the individual sounds that make up words.

Print and Alphabet Knowledge

Preschoolers begin to show that they understand how printing is used and the rules that apply to print. They can identify individual letters and associate the correct sounds to the letters. The parent or caregiver can draw attention to the features of printed letters and show children different print types, such as those used in menus, brochures, and magazines. The person can emphasize the relationship between letters and sounds. Reading alphabet books together helps children connect a letter with words that use the letter and pictures of the objects.

Comprehension and Text Structure

By hearing and reading stories, preschoolers begin to comprehend the narrative structure of storytelling and start to ask questions about and comment on the stories. Children are introduced to stories by reading aloud together, and after several rereadings, they’re able to recall its plot, characters, and events. They’re also able to retell the story using puppets and other props related to the book, as well as through their own illustrations and writing.

They’re also able to retell the story using puppets and other props related to the book, as well as through their own illustrations and writing.

Writing

Preschoolers can be introduced to writing as a way to describe in their own words a story or an event, such as preparing a shopping list before going to the grocery store. They can also be asked to write captions for pictures and photographs. Children can be taught the proper spacing of words by writing each word of a sentence on a separate piece of paper. Drawing helps children develop the motor skills required for writing; in place of a pencil or crayon, they can be encouraged to write using their finger or a stick to write in sand or dirt.

Back To Top

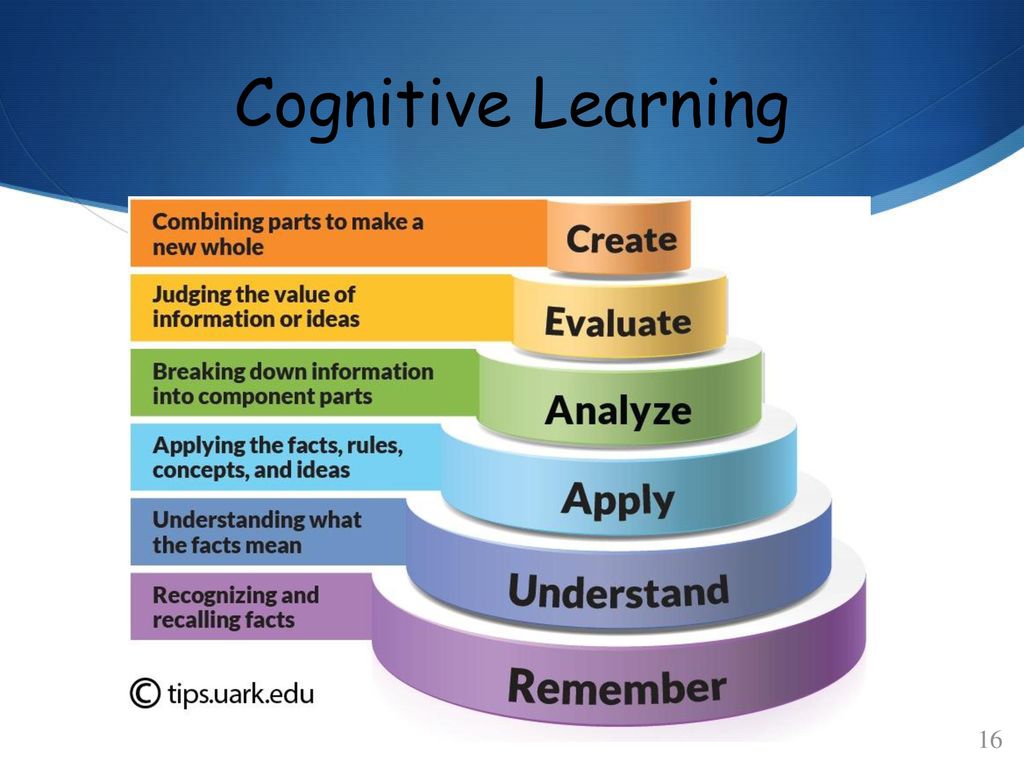

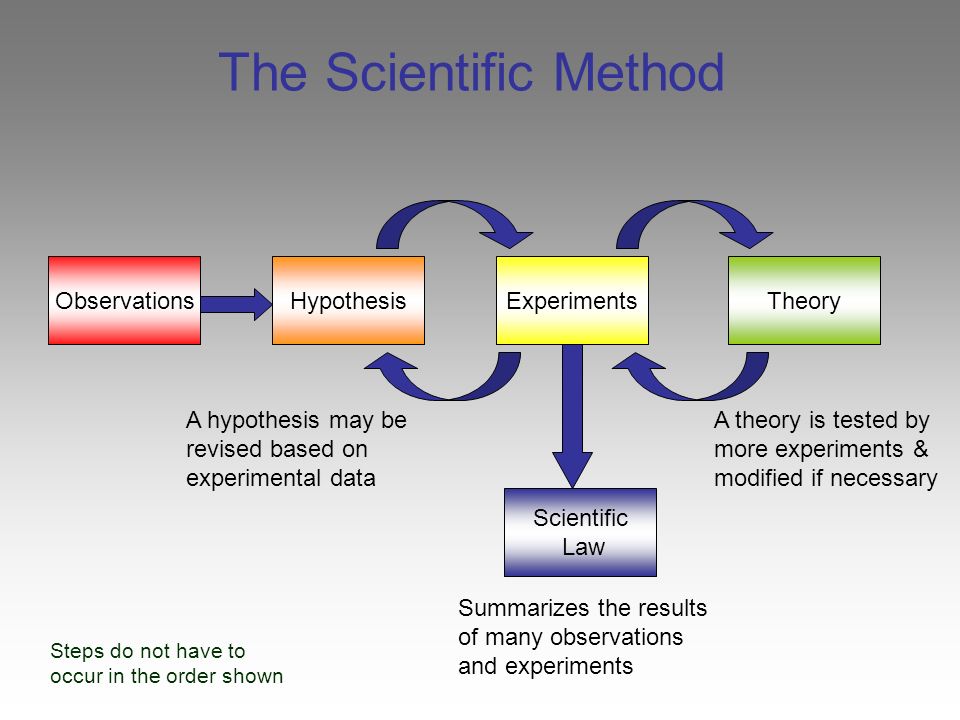

According to The Edvocate, This Reading Mama, and UpToDate, readers should be able to complete the following tasks at each literacy development stage. Emergent literacy: sing the ABCs; alphabetic fluency: see the relationships between letters and sounds; words and patterns: read silently without vocalizing; intermediate reading: read to acquire ideas and gain knowledge; and advanced reading: comprehend longer texts such as books.

Back To Top

5 Literacy Development Stages

Early literacy typically occurs in a child’s first three years, when the child is introduced to books, stories, and writing tools (paper, pencils, etc.). Children learn language, reading, and writing skills simultaneously, in part through their experiences and interactions with others. Parents and caregivers can encourage early literacy development stages through various activities:

- Read to children beginning in earliest infancy.

- Let them handle books.

- Help them identify and interact with images in books.

- Narrate and imitate the actions in the pictures.

- Spend as much time as possible talking to infants.

The goal of early literacy efforts isn’t to teach children to read at a very young age but rather to prepare them for each stage of literacy development, from earliest image recognition through reading fluency at ages 11 to 14. The five stages of literacy development are emergent literacy, alphabetic fluency, words and patterns, intermediate reading, and advanced reading.

1. Emergent Literacy

The initial stage of literacy development sees children acquire literacy skills in informal settings before their formal schooling begins. This preliterate phase lasts until children are 5 or 6 years old and is characterized by specific pre-reading behaviors:

- Pretending to read books that others have read to them

- Holding books correctly and playing with them

- A growing interest in pencils, paper, crayons, and other material related to reading and writing

- Speaking or chanting letters even though they may not yet recognize them

- Scribbling make-believe letters or pretending to write

At later ages in this stage, children may recognize and be able to write the letters in their names, distinguish between uppercase and lowercase letters, and identify an increasing number of high-frequency words.

2. Alphabetic Fluency

At this novice reader stage, children between the ages of 5 and 8 begin to recognize relationships between letters and sounds. These activities are typically observed during this phase of literacy development:

These activities are typically observed during this phase of literacy development:

- Recognizing and pronouncing words they see in print

- Writing phonetically

- Using pictures and other context clues to identify unfamiliar words

- Pointing at words as they read them out loud

- Occasionally reversing letters when they write them

3. Words and Patterns

During this transitional stage that occurs from ages 7 to 9, children’s reading fluency improves, and children begin to recognize syllables and phonemes rather than simply individual letters. Children in this decoding reader phase have reading vocabularies of up to 3,000 words. Behaviors in this stage include the following:

- Reading without assistance

- Much improved reading comprehension

- Silent reading without vocalizing

- Greater recognition of high-frequency words

- Reduced reliance on context clues to figure out the meaning of new words

4.

Intermediate Reading

Intermediate ReadingBy ages 9 to 15, children begin to acquire ideas from what they’re reading. Their reading material includes textbooks, dictionaries and other reference works, newspapers, magazines, and trade books. At this stage of literacy development, a child’s reading comprehension becomes equivalent to listening comprehension. These are some of the experiences of readers at this phase:

- Gaining new knowledge

- Experiencing new feelings through the stories they read

- Exploring issues from various perspectives

- Developing strategies for learning the meaning of unfamiliar words

- Reading at a faster pace

5. Advanced Reading

At the last stage of literacy development, readers can comprehend long and complex text without assistance. They’re also able to find on their own books and other printed material that’s relevant to a specific topic. Characteristics of readers at this stage include the following:

- Reading for many different purposes and to expand their own interests

- Seeking different perspectives and points of view and understanding that what they read can influence their opinions

- Gaining a deeper understanding of the subtext of what they read, or reading between the lines to grasp the wider context of the material

- Expanding their vocabulary and knowledge of subjects through reading recommendations or their own selection of material

Back To Top

Literacy Development in Early Childhood

Literacy development in early childhood entails helping children build language skills, including their vocabulary, ability to express themselves, and reading comprehension. Learning to read is a complex process that children master at their own pace, so it’s natural for some children to proceed more slowly than others.

Learning to read is a complex process that children master at their own pace, so it’s natural for some children to proceed more slowly than others.

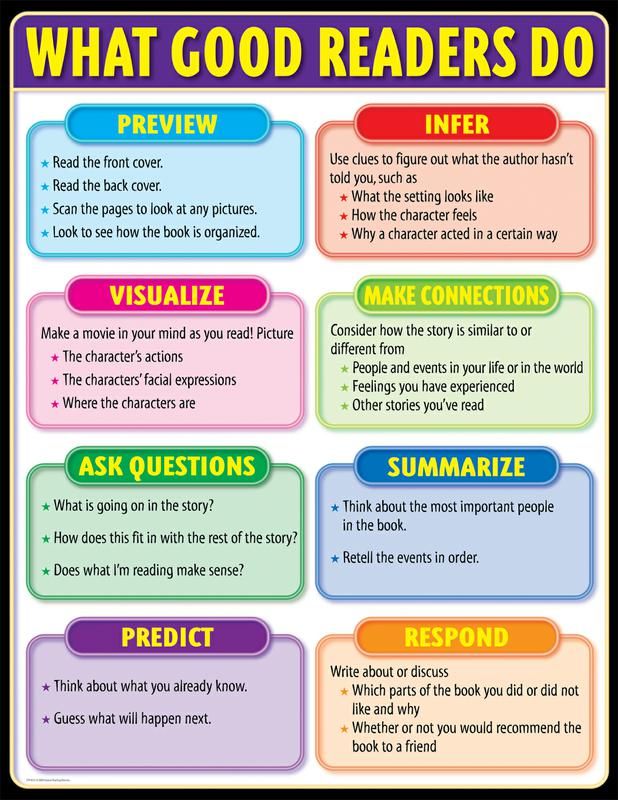

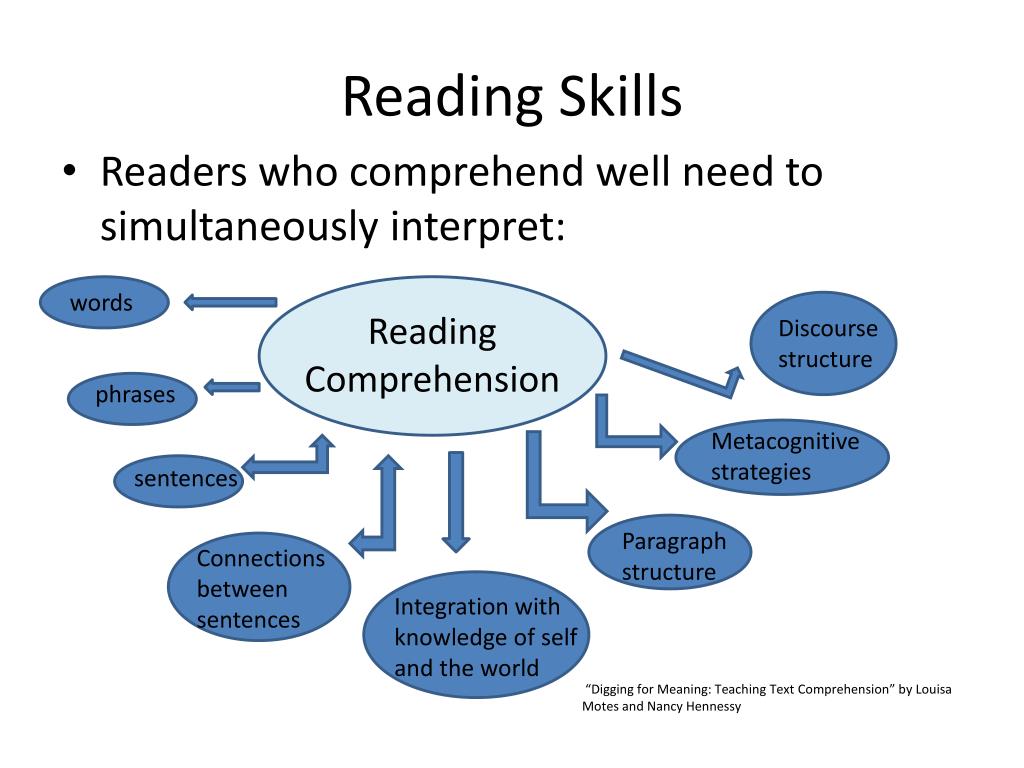

Skills Needed for Reading Comprehension

The many individual skills required for reading comprehension can be divided into seven broad categories: decoding, fluency, vocabulary, sentence structure, sentence cohesion, background knowledge, and working memory and attention.

Back To Top

The skills that make up reading comprehension, according to Reading Rockets and Understood: 1. Decoding — Sound out words. 2. Fluency — Recognize words by sight. 3. Vocabulary — Become familiar with a collection of words. 4. Sentence structure — Understand how words build sentences. 5. Sentence cohesion — Understand how words connect ideas. 6. World experience — Relate to what’s being read. 7. Working memory — Take in information from text.

Back To Top

- Decoding: Children learn the meaning of words by sounding out words they’ve heard before but haven’t seen in writing. Decoding requires phonemic awareness, or knowledge of the basic building blocks of meaning in a language. This is part of broader phonological awareness, which allows children to associate specific sounds with their written representation.

- Fluency: Once children can recognize words immediately as they read, they’re able to comprehend what they’re reading much faster. Children learn irregular words that they can’t sound out, such as “of” and “the.” Fluency improves comprehension by allowing readers to consider groups of words together to get a better sense of their meaning.

- Vocabulary: While children learn some of their vocabulary through direct instruction, they learn most new words by reading on their own and from their everyday experiences. Among the creative ways to introduce children to new words are through using them in conversations with children, telling jokes, and playing word games.

- Sentence structure and cohesion: Reading comprehension depends on a child’s understanding of how phrases and sentences are constructed. Sentence cohesion is the ability to connect the ideas expressed in a sentence and between sentences, while coherence describes how the ideas in a sentence link to the overall theme of the book or material being read.

- Experience, reasoning, and background knowledge: Children and adults bring their own knowledge and experience to the material they’re reading, so they can place the information in a broader context and more closely relate to the subject. Gaining the ability to reason about what they’re reading is helped by giving the child greater exposure to the world through hands-on experiences, conversations, art, and reading itself.

- Working memory and attention: Working memory and attention are considered part of a child’s executive function, which is required to complete complex tasks.

This includes organizing and planning, staying focused, and tracking their own progress. Working memory lets children retain and reuse information as well as identify the words they don’t understand. Maintaining attention as they read bolsters comprehension and lets children read at a faster pace.

This includes organizing and planning, staying focused, and tracking their own progress. Working memory lets children retain and reuse information as well as identify the words they don’t understand. Maintaining attention as they read bolsters comprehension and lets children read at a faster pace.

Activities That Stimulate Reading Comprehension

The best way to prepare children for a lifetime of reading enjoyment is to surround them with words from infancy through their teen years. Everyday activities, such as eating meals, going to the store, taking a bath, and playing outside are excellent opportunities to build a child’s vocabulary and other literacy skills. These literacy activities are suitable for infants and toddlers, as well as for pre-K and school-age children.

- Talking to and singing with young children: Rhyming is a great way to catch and maintain a young child’s interest, whether by reciting nursery rhymes or making up rhymes in everyday conversations.

Repeat the sounds that the child makes, or ask children to repeat the sounds they hear. Narrate your walks or car trips, and ask the child to repeat the sounds of the objects seen.

Repeat the sounds that the child makes, or ask children to repeat the sounds they hear. Narrate your walks or car trips, and ask the child to repeat the sounds of the objects seen. - Reading actively: While reading together, emphasize the rhyming words, and make up rhymes for the words the child encounters. Let the child turn the book’s pages and ask the child to comment on the images on the page. Stop on occasion while reading to ask the child what will happen next. Ask the child to act out the story, and tie what’s happening with events in the child’s own life.

- Scribbling and drawing: Scribbling and drawing help children develop the motor skills they need for writing. They also help children understand that certain writing and pictures have specific meanings. Ask children to add a scribble or drawing to cards and letters or to describe what they’ve drawn, writing down the words they use so that they can connect writing with the sound of words.

- Making a storybook or alphabet book: Using a computer or paper and pencils, help children create a story using their own drawings and words. A simple example is an alphabet book with each letter on one side of a page and a drawing of an item that begins with that letter on the opposite side of the page.

Resources: Literacy Development in Early Childhood

- Scholastic, 6 Strategies to Improve Reading Comprehension — Strategies include asking children to read aloud, rereading simple and familiar books to gain fluency, and talking to the children about what they’re reading.

- S. Department of Education, Early Learning Resources — Resources include language building tips for parents, guides for preschool teachers and child care providers, and early childhood literacy assessment techniques.

- Raising Readers, How to Get Your Child Ready to Read — Tip sheets for parents and families in several languages, along with downloadable handouts that teach a different aspect of literacy for each month of the year.

Back To Top

Early Literacy Development Stages in Children

While researchers in early literacy development agree that it’s a step-by-step process, they define the steps in different ways. Generally, the path a child takes from earliest awareness of print and reading to independent, competent reader and writer is completed in five stages:

Awareness and Exploration Stage

Between the ages of 6 months and 6 years old, children hear and experiment with reproducing and creating a range of monosyllabic and polysyllabic sounds, ultimately forming words that represent discrete things and concepts. Their introduction to reading is typically through listening to and discussing storybooks, participating in rhyming activities, and beginning to identify letters.

Novice Reading and Writing Stage

At ages 6 and 7, children match letters with sounds and connect printed and spoken words. They can tell simple stories, and understand the orientation of printed words on a page. They’re also able to read and write individual letters and high-frequency words and sound out new monosyllabic words that they encounter.

Traditional Reading and Writing Stage

When they’re between the ages of 7 and 9, children gain fluency in reading familiar stories, increasing their enjoyment. They’re able to decode elements of words and sentences while building their vocabulary of words they recognize on sight. Their reading skills allow them to process new information, and they have a better grasp of the meaning of the material they read.

Fluent and Comprehending Reading and Writing Stage

Between the ages of 9 and 15, children are able to understand what they’re reading from multiple perspectives and learn new ideas and concepts. Their reading expands to reference books, textbooks, and various media, in which they’re exposed to a range of worldviews in addition to new syntax and specialized vocabularies.

Expert Reading and Writing Stage

When children reach their midteens, their reading skills allow them to tackle advanced topics in science, history, mathematics, and the arts. They’re able to make associations across subject areas and consider complex issues from diverse points of view. Their reading and writing span topics from social and physical sciences to politics and current affairs.

They’re able to make associations across subject areas and consider complex issues from diverse points of view. Their reading and writing span topics from social and physical sciences to politics and current affairs.

Importance of Literacy Development in Children

Children gain confidence in many areas of their lives when they grow up to become strong readers. The literary skills they began learning in their first months of life enhance all aspects of their lifelong education. By encouraging a love of reading in children, we instill a desire to learn and progress that propels them through their school years, careers, and personal lives. Children learn that reading is one of the most rewarding and enjoyable skills they’ll ever possess.

Back To Top

Infographic Sources

Crayons, Pencils, and Keyboards, “Why is Literacy Development Important for Children?”

Martin-Pitt Partnership for Children, “Benefits of Early Literacy Skills”

Nationwide Children’s Hospital, “Early Literacy: Why Reading is Important to a Child’s Development”

Reading Rockets, “Comprehension Instruction: What Works”

The Edvocate, “What Are The Five Stages of Reading Development?”

This Reading Mama, “Word Pattern Readers and Spellers {Stage 3}”

Understood, “6 Essential Skills for Reading Comprehension”

UpToDate, “Emergent Literacy Including Language Development”

The 5 Stages for Developing Literacy

Site Search

Site Search

Shop Now

Teaching Tips

June 17, 2021

0

4 min

Literacy development is the process of learning words, sounds, and language. Children develop literacy skills in order to learn to read and write confidently and eventually improve their communication skills overall. The stages of literacy development that a child goes through can vary depending on the child’s comprehension levels but generally include the same key concepts along the way. Understanding literacy development in children as an educator is key for helping children master these core skills that set them up for their education. With an understanding of literacy development and how to address each of the stages of literacy development, both educators and students alike will be set up for success in the classroom.

Children develop literacy skills in order to learn to read and write confidently and eventually improve their communication skills overall. The stages of literacy development that a child goes through can vary depending on the child’s comprehension levels but generally include the same key concepts along the way. Understanding literacy development in children as an educator is key for helping children master these core skills that set them up for their education. With an understanding of literacy development and how to address each of the stages of literacy development, both educators and students alike will be set up for success in the classroom.

Why is Literacy Development Important?

As the pillars of language and reading skills, literacy development is a crucial time in a child’s life. Educators need to understand why literacy development is so important in order to effectively help children within each stage of their early literacy development.

Here are just a few reasons early literacy development is important:

- Children with confident reading abilities typically struggle less with their studies and have a confident approach to their education.

- Strong literacy skills translate well into independent learning and encourage consistent growth in and out of the classroom.

- Literacy development affects the way students communicate and problem solve. Those with strong literacy skills usually have improved cognitive ability.

As a child grows older and demonstrates the key stages of literacy development they will improve their reading and writing ability. The five stages of literacy development include emergent literacy, alphabetic fluency, words and patterns, intermediate reading, and advanced reading. Each stage of literacy development helps the child move forward and become a stronger student. Keep in mind that a child's current age group doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re at that step in their early literacy development.

Stage 1: Emergent LiteracyAge Range: 4-6 years old.

As the earliest stage of literacy development, emergent literacy is the first moment that a child begins to understand letters and words. While many of the behaviors of the emergent literacy stage are not fully formed and irregular, these are still some of the first signs that a child is beginning to form literacy ability.

While many of the behaviors of the emergent literacy stage are not fully formed and irregular, these are still some of the first signs that a child is beginning to form literacy ability.

Here are Some Behaviors of Stage 1 Learners:

- Pretending to be able to read children’s books.

- The ability to recognize the first letter of their name.

- Singing the ABCs, even if unable to identify letters separately.

- Trying to memorize certain books to “read” them.

- The ability to recognize some letters and potentially their sound.

- The ability to find words in their environment.

To learn helpful strategies to support emerging readers by helping them understand what alphabet knowledge and phonological awareness are and why they are both so critically important watch this free webinar, 5 Essential Strategies to Effectively Teach Letters and Sounds.

Stage 2: Alphabetic Fluency

Age Range: 6-7 years old.

As the child grows older and more comfortable with learning their words and letters, they enter the alphabetic fluency stage of literacy development.

Here are Some Behaviors of Stage 2 Learners:

- No longer “pretend” reading.

- Finger-pointing to words while reading them.

- Beginning to recognize words.

- Admitting that they’re unable to read certain words.

- Using pictures and context clues to figure out certain words.

- Reading out loud word by word.

Stage 3: Words and Patterns

Age Range: 7-9 years old.

Sometimes referred to as the “transitional” stage of literacy development, the words and patterns stage is when children begin to develop stronger reading skills. This is the stage when children can vary the most in terms of skills and may adopt behaviors in multiple stages of literacy development.

Here are Some Behaviors of Stage 3 Learners:

- Less decoding of words and stronger ability to comprehend reading materials.

- More self-correction when what is read is unclear.

- Less sound by sound reading and easier time grouping letters.

- Able to recognize words that pop up most often automatically.

- Less reliance on context clues to figure out unknown words.

- Beginning to be able to spell complex consonant words like “-tch”.

Stage 4: Intermediate Reading

Age Range: 9-11 years old.

During the intermediate stage of literacy development, children begin to rely less on educational crutches that help a child learn new words. This is also when children are becoming able to write out sentences with less error and develop stronger fluency overall.

Here are Some Behaviors of Stage 4 Learners:

- Reading to learn new information and writing for multiple purposes.

- Less difficulty with independent reading.

- Reading to explore new concepts from numerous perspectives.

- Reading longer materials such as textbooks with little difficulty.

- An interest in wanting to learn and develop new vocabulary.

Stage 5: Advanced Reading

Age Range: 11-14 years old.

As the last stage of literacy development, advanced reading is when children become fully fluent and capable of relying on independent reading to learn new information. Reading and writing provide little difficulty and students can absorb complex reading materials during this stage.

Here are Some Behaviors of Stage 5 Learners:

- The desire to read numerous types of reading materials.

- Reading becomes a daily tool for learning new information.

- The ability to formulate longer texts such as essays or book reports.

- Readers usually have a strong understanding of the meaning and semantics of words.

- The ability to understand and retain complex reading materials.

Develop Early Literacy with Learning Without Tears!

Each stage of literacy development provides its own unique challenges and triumphs in learning to become confident in reading and writing. Learning Without Tears specializes in early childhood development programs that help further progress within the stages of literacy development. Learning Without Tears offers a wide range of educational materials to help teachers create an engaging lesson plan that will get children excited to learn more. With resources for parents to get children set up for school and programs for teachers to teach early literacy concepts, Learning Without Tears is committed to helping children become confident students. Learning Without Tears has created resources and educational materials for children in pre-k to 5th grade to help students succeed during every stage of literacy development and early childhood education. Explore Learning Without Tears to help children get the most out of their education today.

Learning Without Tears specializes in early childhood development programs that help further progress within the stages of literacy development. Learning Without Tears offers a wide range of educational materials to help teachers create an engaging lesson plan that will get children excited to learn more. With resources for parents to get children set up for school and programs for teachers to teach early literacy concepts, Learning Without Tears is committed to helping children become confident students. Learning Without Tears has created resources and educational materials for children in pre-k to 5th grade to help students succeed during every stage of literacy development and early childhood education. Explore Learning Without Tears to help children get the most out of their education today.

A—Z for Mat Man and Me

!

Seamlessly bring the ABCs to life while building foundational literacy skills with our new letter book series. Each of our illustrated letter books introduces a letter of the alphabet and emphasizes their associated sound through captivating, visual stories. The engaging stories in each book capture children's imaginations and expose them to social-emotional skills and diverse cultures.

The engaging stories in each book capture children's imaginations and expose them to social-emotional skills and diverse cultures.

Learn More → .

Related Tags

Ask the Experts Teaching Tips Multisensory Learning Readiness Home Connection

Ask the Experts, Teaching Tips, Multisensory Learning, Readiness

Pint-Size Book Authors: Using Early Readers as Mentor Texts

September 10, 2021

0 3 min

Ask the Experts, Teaching Tips, Multisensory Learning, Readiness, Home Connection

Why is Literacy Development Important for Children?

June 17, 2021

0 4 min

Ask the Experts, Teaching Tips, Multisensory Learning, Readiness, Home Connection

Naming Letters Is Not a Straight Path to Literacy: Here’s Why

April 15, 2021

4 2 mins

There are no comments

Stay Connected and Save 10%Sign up for our newsletter and get the latest updates, Classroom tips & free downloads.

Comments

what it is and how to develop it

The modern world requires a rethinking of pedagogical approaches in teaching schoolchildren. Increasingly, thoughts are being expressed about the need to develop functional literacy in schoolchildren. Let's figure out what its value is and what tools teachers should use

What is functional literacy

The concept of functional literacy of schoolchildren appeared in the 1970s and implied a set of reading and writing skills to solve real life problems. Over the next 40 years, functional literacy in the learning and development of schoolchildren has become more important than basic literacy. Today, a functionally literate student is an indicator of the quality of education. Academic knowledge alone is no longer enough in life. The emphasis is shifting to the ability to use the information and skills received in specific situations.

Distinctive features of a schoolchild with developed functional literacy:

- successfully solves various everyday problems;

- is able to communicate and find a way out in a variety of social situations;

- uses basic reading and writing skills to build communications;

- builds interdisciplinary connections when the same fact or phenomenon is studied and then evaluated from different angles.

The ability to assess the situation and use the acquired knowledge in practice is not formed in one lesson, the process of improving functional literacy is logically built into the curriculum for several years.

Benefits of functional literacy

The labor market requires those professionals who are able to quickly respond to any challenges, learn new knowledge and apply it in solving emerging problems. These are functionally literate people. If a student has managed to acquire such skills, he will easily navigate in modern reality.

Some educators find it difficult to teach functional literacy. However, if you follow all the pedagogical developments, it becomes more interesting for children to study, and for a teacher to work.

Analysis of meta-subject learning outcomes shows that the emphasis on functional literacy makes children involved in the cognitive process, able to analyze and segment information, draw conclusions and use the data obtained in different educational areas. This naturally improves the performance of the class.

This naturally improves the performance of the class.

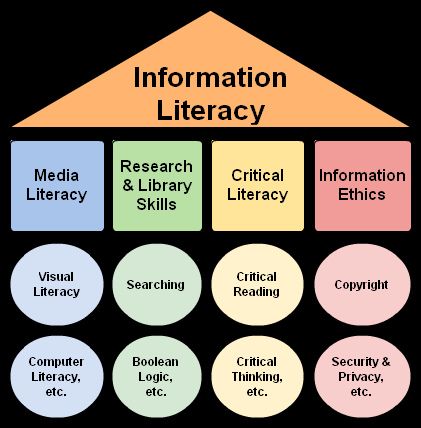

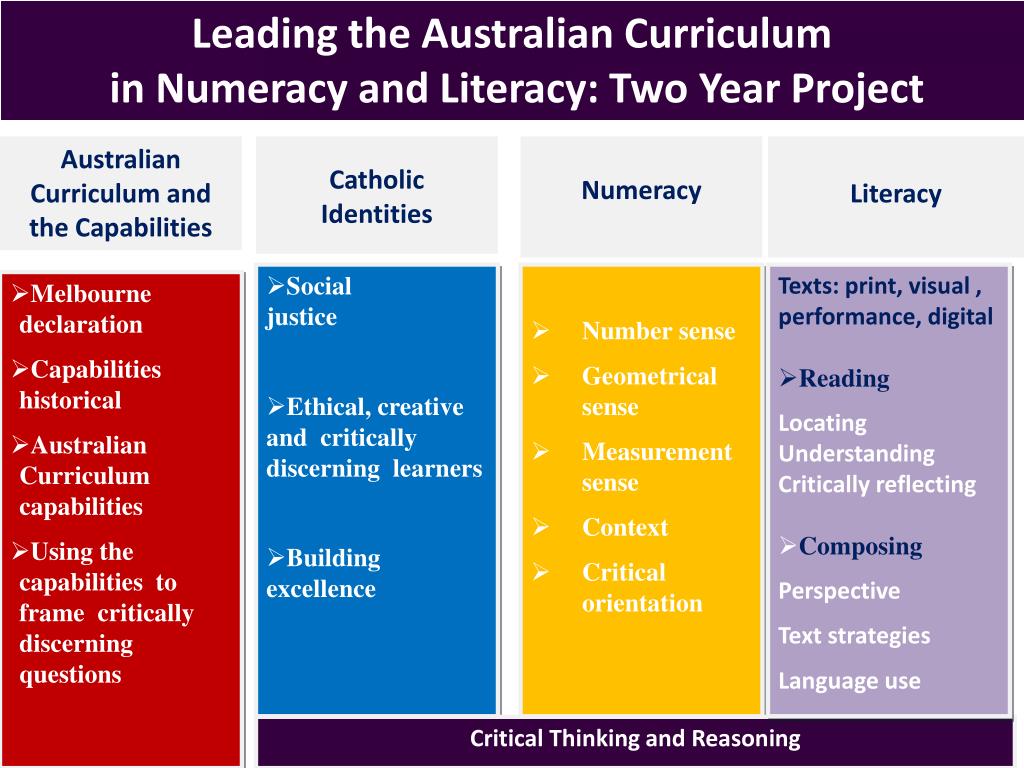

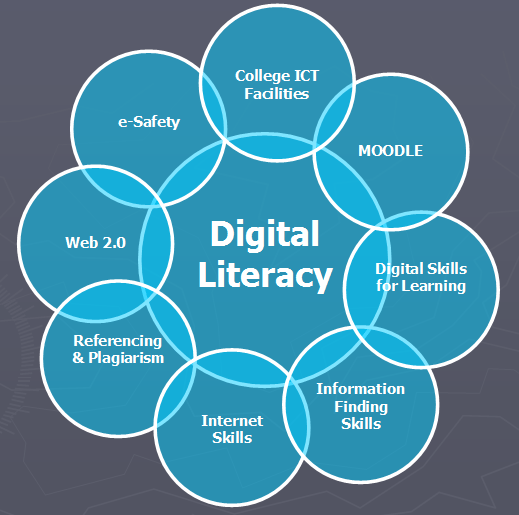

What functional literacy consists of

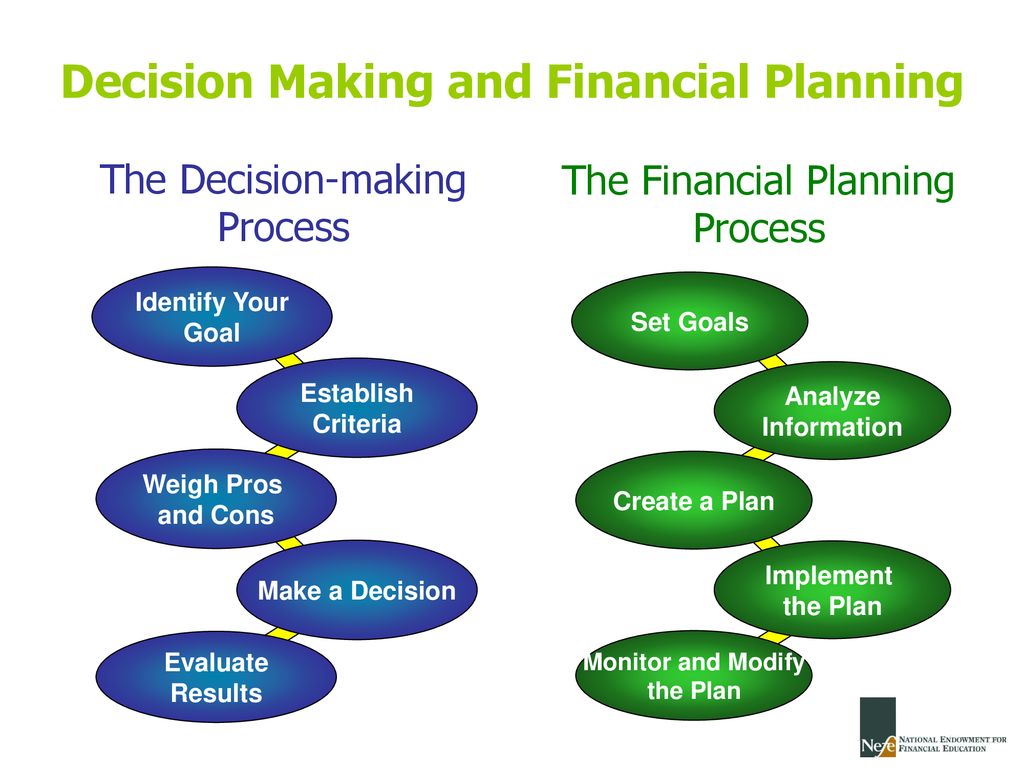

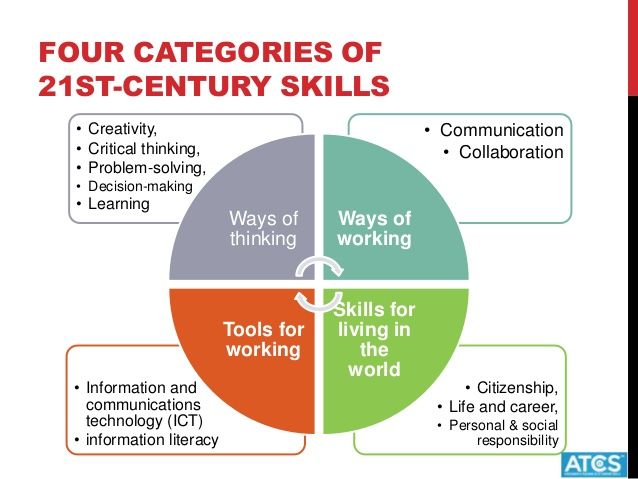

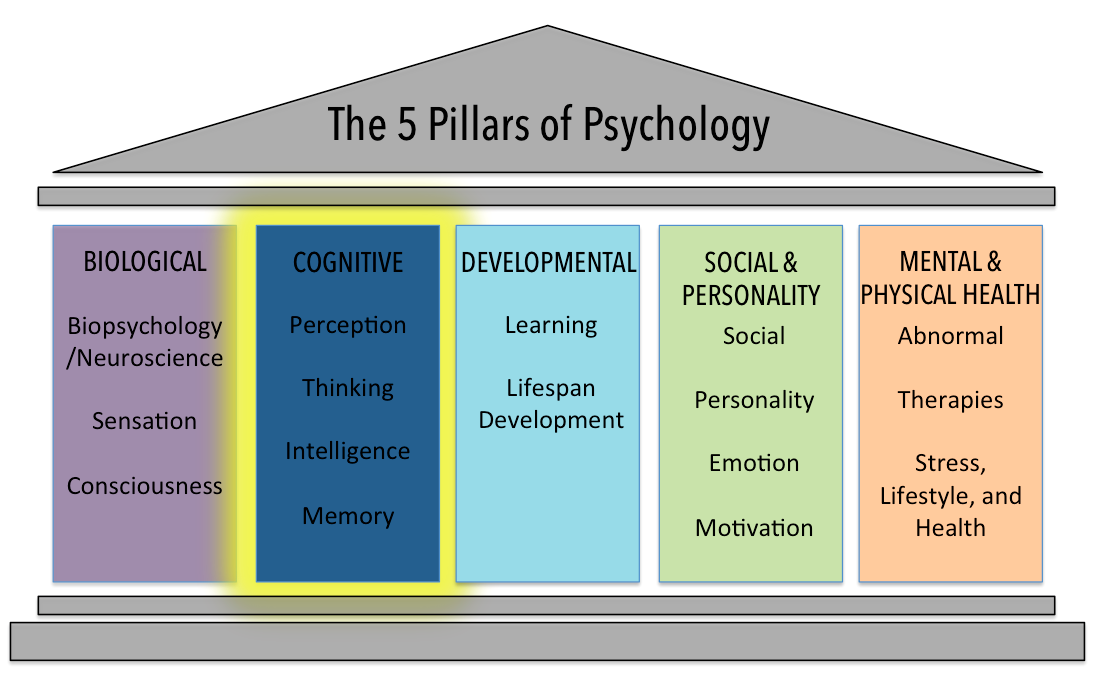

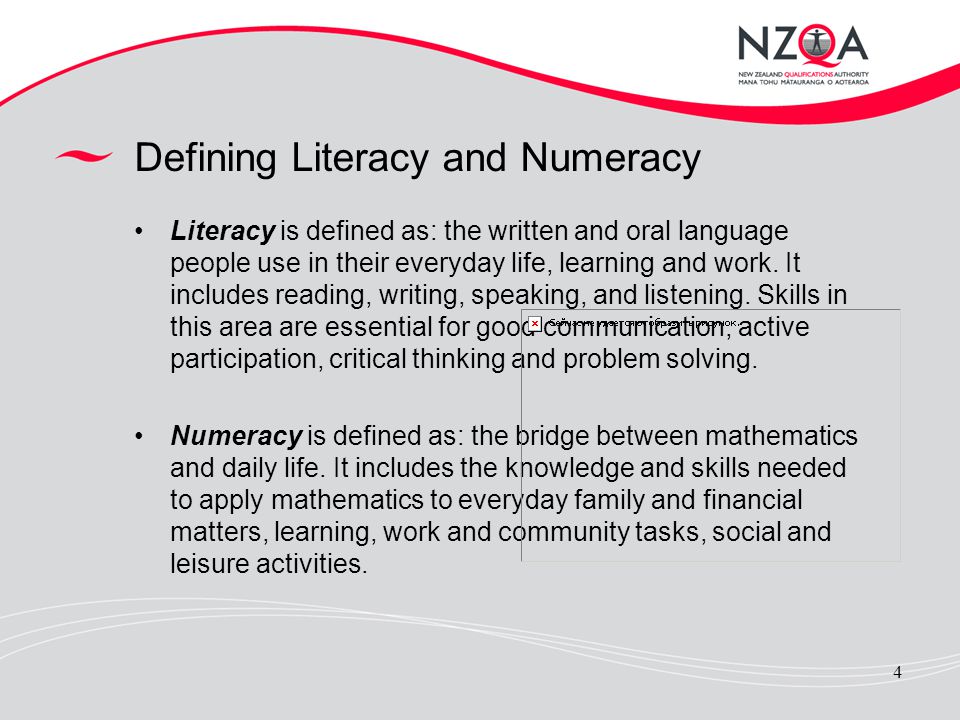

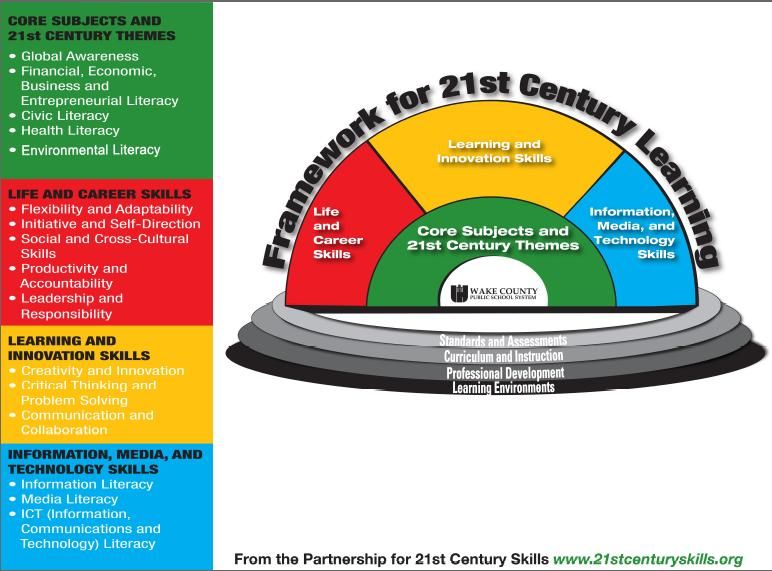

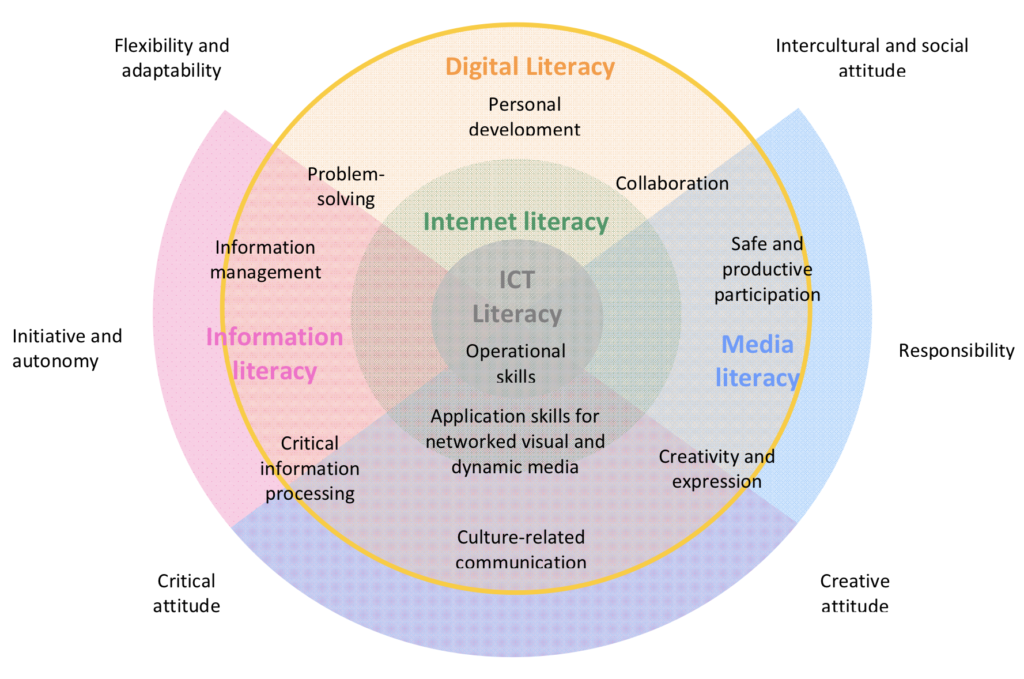

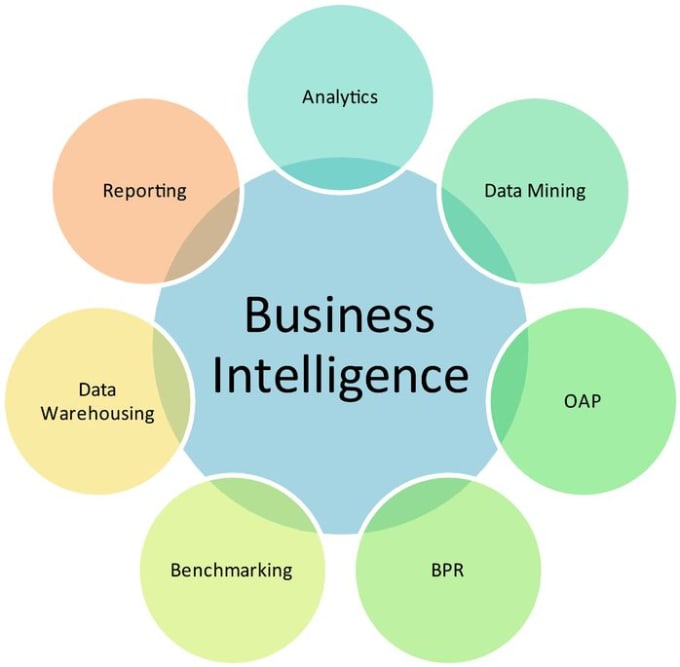

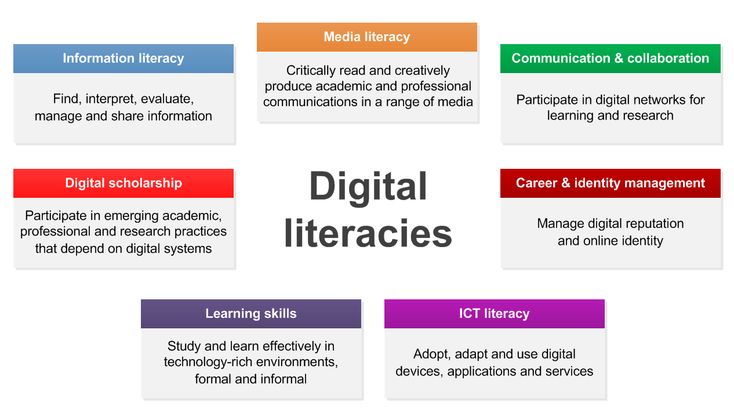

The concept combines reading, mathematical, scientific, financial and computer literacy, global competencies and creative thinking. It is about applying the acquired knowledge and skills in a versatile practical life.

Example. The student has read the description of natural phenomena, but cannot answer the questions and discuss the situation. This suggests that he has developed only basic reading skills. Reading functional literacy makes the student able to reason, draw conclusions, simulate the described situations in real life, for example, independently determine the air temperature, cardinal points, wind strength, and predict the level of natural danger.

Reading literacy

The federal state educational standard includes the task of developing the functional literacy of primary and secondary school students. For example, reading literacy is the most important meta-subject learning outcome.

For example, reading literacy is the most important meta-subject learning outcome.

There must be tasks in the lesson where it is impossible to give an unambiguous answer, but you need to reason on the proposed topic. This helps to replenish the accumulated knowledge and achieve certain goals in life, applying them in practice.

Examples. What would you do if you were the main character? Why did the author end the book in this way? What could have happened if the main character had acted differently?

It is important to learn to read between the lines, to be able to find and extract important and secondary information, to notice various relationships and parallels.

Mathematical literacy

A correctly asked question related to practical life will help to form mathematical literacy.

Example. Electric vehicle efficiency problem. Given: the amount of fuel that is required when operating a car with an internal combustion engine, the amount of energy to recharge an electric car, the electricity tariff and the cost of one liter of gasoline.

As a result of the decision, the class will see how many years the difference in the cost of maintaining a car with an internal combustion engine and an electric car will reach the cost of the latter, that is, it will fully pay off.

A child with mathematical literacy is able to use knowledge in various contexts, predict phenomena based on mathematical data, calculate actual benefits and make informed decisions.

Science literacy

Tasks for the analysis and comparison of natural phenomena, geographical maps, processes in the environment will help here. To develop competencies in the field of natural sciences, it is important to correctly interpret scientific data, conduct practical research, explain natural phenomena and find existing evidence.

Example. Analysis of the seismic activity map will help answer the question of which region will be more comfortable and safer to live in. You can offer high school students to calculate the optimal number of storeys of buildings that can be erected in certain seismic and geological conditions.

A student with natural science literacy is able to form an opinion about phenomena and situations related to natural processes.

Global competencies

Another component of functional literacy is global competencies. This is the ability of a student to use knowledge independently or in a group to solve global problems.

Its development is facilitated by tasks for finding cause-and-effect relationships between phenomena, events and natural consequences. Students are offered to analyze the situation and answer questions in the field of demography, economics, ecology and other global problems.

The child must be able to manage his behavior, openly perceive new information, be communicative and interact in a group. This component develops analytical and critical thinking, empathy, and the ability to cooperate. Collaborative research helps build respect for other people's opinions and cultures. Modern education offers a completely new level of development of a person who is able to understand and accept the beliefs of other people.

Creative thinking

This includes everything related to creativity in a global sense: the ability to generate your own and improve other people's ideas, offer effective solutions, use fantasy and imagination. The result is a critical analysis of the proposals, which will help to see their strengths and weaknesses.

Collaborative work on a wall newspaper, scheduling lessons and household chores, creating a picture on a current topic or an image of a fantastic animal helps to develop creative thinking.

Creative thinking is associated not only with creative activity, but also with a deep knowledge of the subject. Creativity inextricably accompanies daily tasks, which, under certain conditions, can be solved faster and easier.

Financial literacy

Financial literacy means that students become familiar with basic concepts and learn to make decisions to improve their own well-being.

In order to master this type of literacy, teachers model situations for students with banking products, money transactions, and other financial market instruments.

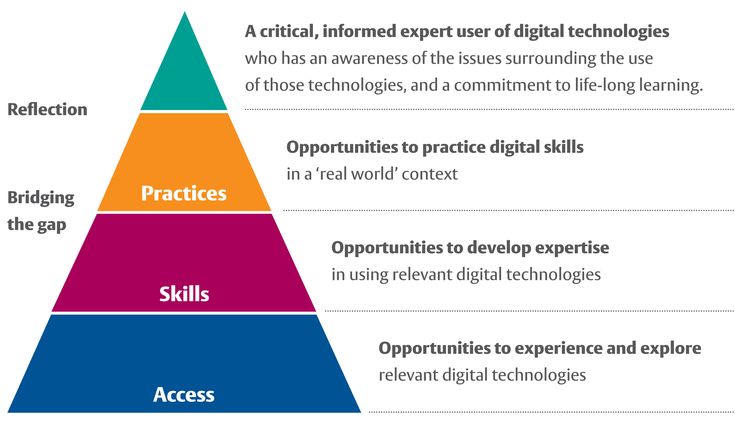

Computer literacy

The component related to computer literacy and safety of schoolchildren has become one of the first places in recent years. The skill of interacting with electronic services is required already in elementary school.

Computer literacy consists in the ability to:

- work with information on the Internet, search and analyze data, segment it according to the degree of reliability.

- use electronic services: mail, cloud storage, basic programs;

- know the rules of security and protection of personal information, manage personal accounts in social networks.

Ways to develop functional literacy of schoolchildren

Basic rules

Functional literacy at school

Professional development for teachers. Online test. Certificate

View the program

There are more and more tasks of various types for the development of functional literacy of primary and advanced levels at school. They should be evenly distributed in the educational process throughout the year.

They should be evenly distributed in the educational process throughout the year.

Their main features:

- linking to real situations in which children can imagine themselves;

- compliance with the age of students;

- consistency and interconnection of knowledge and factors.

Formation of functional literacy in elementary school

For the development of functional literacy in younger students, it is important that the tasks correspond to their practical experience. A topic close to children arouses interest and inspires to seek new knowledge. Instead of diggers and turners, it is better to choose the heroes of your favorite cartoons and computer games for setting tasks.

Example. A task that will help you calculate the amount of plastic to make a model of a golden key on a 3D printer. If an exciting master class is held before this task, the children will not be able to tear themselves away from the solution and will certainly offer their own options.

Additional education plays an important role in the formation of functional literacy in primary school. Classes in circles develop creative abilities, creative thinking, computer and reading literacy. Proper synchronization of the work of teachers and metasubject connections will help to quickly develop the necessary competencies.

Formation of functional literacy in basic school

In middle and high school, they offer a gradual increase in the amount of knowledge and the complexity of information analysis. You can talk with children about serious global problems, the causes of world wars and social inequality. The results are also evaluated according to more stringent criteria.

Assignments are given at the intersection of different sciences and interdisciplinary classes, where they simultaneously study history and literature, geography and economics and draw conclusions based on their relationships. Good results are demonstrated by independent and group research work, project activities in natural science and sociological areas.

To develop critical thinking in the main school, they analyze information and learn to identify fake and viral content. Tasks in financial literacy are also becoming more difficult. Children can be offered to build their own financial pyramid and calculate the duration of its existence.

The formation of functional literacy of students is the task of every modern teacher. This is a difficult process, where creativity and creative thinking, the use of innovative forms and teaching methods are required from the teacher himself. Successful mastering of the components of functional literacy will help to bring up an initiative, independent, socially responsible person who is able to adapt and find his place in a constantly changing world.

Literacy and its Impact on Child Development: Comments on Articles Tomblin and Sénéchal

Introduction

The concept of “literacy” has taken center stage in early education only within the last decade. Prior to this, experts rarely considered literacy as a critical aspect of the healthy growth and development of young children. The current level of reading problems among schoolchildren remains unacceptably high. The data show that about 40% of fourth grade students have difficulty reading even at the elementary level, and that there are a disproportionate number of poor children and children from ethnic or racial minorities among children with reading problems. 1 A paradigm shift over the past decade, spurred by the 1998 publication Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children by the United States National Research Council, has emphasized the importance of early education as a context within which addressing the identified urgent issues is likely to be effective. Early childhood education is the period during which young children develop skills, knowledge and interest in the symbolic and semantic foundations of written and spoken language. In this paper, I interpret these abilities and interests as "pre-literacy" abilities in order to emphasize their role as precursors of traditionally understood literacy.

Prior to this, experts rarely considered literacy as a critical aspect of the healthy growth and development of young children. The current level of reading problems among schoolchildren remains unacceptably high. The data show that about 40% of fourth grade students have difficulty reading even at the elementary level, and that there are a disproportionate number of poor children and children from ethnic or racial minorities among children with reading problems. 1 A paradigm shift over the past decade, spurred by the 1998 publication Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children by the United States National Research Council, has emphasized the importance of early education as a context within which addressing the identified urgent issues is likely to be effective. Early childhood education is the period during which young children develop skills, knowledge and interest in the symbolic and semantic foundations of written and spoken language. In this paper, I interpret these abilities and interests as "pre-literacy" abilities in order to emphasize their role as precursors of traditionally understood literacy. To date, attention to pre-literacy as an integral element of early childhood education stems from two emerging areas of research that show that:

To date, attention to pre-literacy as an integral element of early childhood education stems from two emerging areas of research that show that:

- Individual differences in pre-literacy skills among children are meaningfully important – early-onset differences contribute significantly to longitudinal measures of reading performance; 2

- The prevalence of reading problems is more likely to be affected by prevention than by remedial education, because if a particular child falls behind in reading in primary school, it is more likely that a return to healthy progress will not occur. 3

Research and findings

Experts Tomblin and Seneschal discuss current and important aspects of the current literature on the development of pre-literacy and its short- and long-term relationships with other age-related competencies. According to my reading of the text of their papers, there are three critical areas that require further development: decoding predictors, the language-literacy relationship, and the role of temperament and motivation.

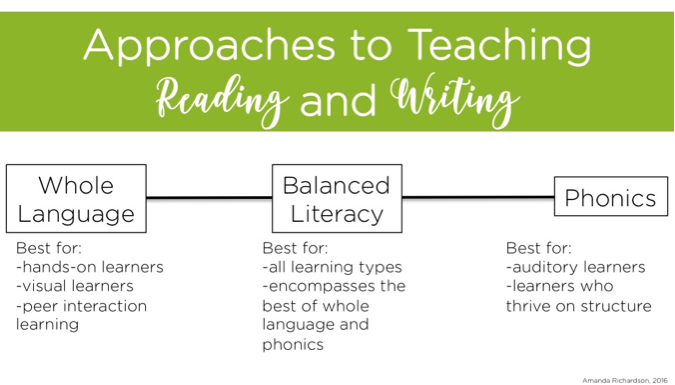

First, the current cumulative research literature on the development of early literacy skills and the relationship of this development to later reading outcomes identifies three unique predictors of reading competence: phonological processing, knowledge of printed letters and what they are used for, and spoken language. 2 While the first two aspects directly prepare children for acquiring word skills (such as decoding), the third aspect prepares them for text comprehension with little or no effect on decoding. Tomblin aptly points out that reading competence requires both decoding skills and comprehension skills, and the Seneschal emphasizes that children need to first "learn to read" before "reading to learn." It should be understood that the relationship between the two aspects of reading is multiplicative—meaning that both sides of the equation (Decoding x Comprehension = Reading) require any value other than 0 for the reading to be functional. 4 Both Tomblin and the Seneschal do not emphasize enough the importance of developing early decoding precursors in children. Children will never be able to read to learn (i.e. understand) unless they are able to successfully decode. Children who start learning basic reading with inadequate pre-literacy skills will not be able to keep up with decoding educational information, which will slow down the final transition to reading for the sake of understanding the meaning of what they read. Early education is a period during which educators can almost easily improve children's chances of learning to become a reader by gaining initial alphabetic skills (printing and phonological awareness) that will enable children to benefit from the process of decoding directions while learning.

Children will never be able to read to learn (i.e. understand) unless they are able to successfully decode. Children who start learning basic reading with inadequate pre-literacy skills will not be able to keep up with decoding educational information, which will slow down the final transition to reading for the sake of understanding the meaning of what they read. Early education is a period during which educators can almost easily improve children's chances of learning to become a reader by gaining initial alphabetic skills (printing and phonological awareness) that will enable children to benefit from the process of decoding directions while learning.

Second, both Tomblin and the Seneschal emphasize the importance of the role of spoken language in literacy development, although they do not emphasize the relationship between literacy and language development. Scholars are increasingly inclined to view the integrative relationship between language and literacy as interdependent. Engaging children in literacy-related activities, such as reading a storybook or listening to rhymes, requires a metalinguistic focus that focuses on spoken or written language. The continuous involvement of children in literacy classes and their growing tendency to consider language as an object of attention are becoming the first routes of language development. Once children begin to read, even at the most elementary level, reading texts becomes the richest source of new words and concepts, complex syntax, and narrative structures that stimulate further language development. In short, literacy is the most important vehicle for the development of language competencies in children, both in the preschool period and during the periods of initial and subsequent schooling. The relationship between language and literacy is more than a one-way street – language provides a platform for the exploration and experiential learning of written language, which in turn shapes children's later language competencies.

Engaging children in literacy-related activities, such as reading a storybook or listening to rhymes, requires a metalinguistic focus that focuses on spoken or written language. The continuous involvement of children in literacy classes and their growing tendency to consider language as an object of attention are becoming the first routes of language development. Once children begin to read, even at the most elementary level, reading texts becomes the richest source of new words and concepts, complex syntax, and narrative structures that stimulate further language development. In short, literacy is the most important vehicle for the development of language competencies in children, both in the preschool period and during the periods of initial and subsequent schooling. The relationship between language and literacy is more than a one-way street – language provides a platform for the exploration and experiential learning of written language, which in turn shapes children's later language competencies.

Third, the role of temperament and motivation in influencing children's achievement and experience in teaching pre-literacy skills requires further consideration, as Tomblin and Seneschal's findings are insufficient. Tomblin notes overlap between internalizing behaviors (such as anxiety and depression) and literacy difficulties, and Seneschal notes that some children may avoid reading, especially those who feel they do not read well enough. The role of early motivation, self-esteem, and temperament in the development of pre-literacy requires more attention overall, especially when we consider opportunities to stimulate other intrinsic competencies (eg, phonological processing and vocabulary) in prevention programs. Most early education educators know that motivating children to become literate is one of the most important contributions to successful pre-literacy. By trying to experience literacy on their own or in the context of interacting with others, children themselves correct the process of developing pre-literacy! A small, though largely consistent, body of research shows that children's motivation and engagement in literacy activities varies greatly for each child and is relatively related to the individual child's benefit from the activity. 5 Some children actively resist pre-literacy experiences, such as reading a storybook, and children with poor language skills or children who do not receive any literacy experiences at home are more likely to resist involvement in development activities. The scientific literature is still unable to explain why some children resist participation in literacy classes and how this resistance generally correlates with the child's temperament. However, approaches to encouraging young children to become involved in literacy activities and motivate them to become literate need to be considered as one of the most important characteristics of developing effective interventions.

5 Some children actively resist pre-literacy experiences, such as reading a storybook, and children with poor language skills or children who do not receive any literacy experiences at home are more likely to resist involvement in development activities. The scientific literature is still unable to explain why some children resist participation in literacy classes and how this resistance generally correlates with the child's temperament. However, approaches to encouraging young children to become involved in literacy activities and motivate them to become literate need to be considered as one of the most important characteristics of developing effective interventions.

Recommendations for policy makers and services

Modern perspectives for policy makers and services emerge from three scientific findings reported in the literature. First, children with an underdeveloped oral language base will be very vulnerable in the context of acquiring reading competence, which in turn hinders continuous language development. Secondly, it is much more difficult to correct existing reading problems than to prevent them. Third, it appears possible to increase children's chances of acquiring literacy skills through high-quality, intensive, systemic pre-literacy programs implemented in pre-schools and kindergartens before children develop reading problems.

Secondly, it is much more difficult to correct existing reading problems than to prevent them. Third, it appears possible to increase children's chances of acquiring literacy skills through high-quality, intensive, systemic pre-literacy programs implemented in pre-schools and kindergartens before children develop reading problems.

Integrating policy, practice and research

Significant gaps remain in integrating policy, practice and research, and in producing research that can be safely applied to existing programs. Tomblin emphasizes the need for further research into the mechanisms that cause literacy problems in children with language difficulties. Research into these mechanisms is one of the most developed and well-funded areas of research in the United States, and has unequivocally shown the importance of spoken language, phonological processing, and capitalization commonly associated with a child's ability to read. What is needed now is a closer look at ways to stimulate the linkage between policymaking, practice and research to ensure that current efforts to improve literacy rates in young children, especially those who start these programs with low levels of language and literacy, are effective. The Seneschal puts forward several evidence-based proposals to encourage the development of literacy skills in young children, such as word games and book reading. Further scrutiny should be given to the extent to which these activities are effective for children with poor language proficiency, have a longitudinal positive effect, and can be incorporated into existing interventions.

The Seneschal puts forward several evidence-based proposals to encourage the development of literacy skills in young children, such as word games and book reading. Further scrutiny should be given to the extent to which these activities are effective for children with poor language proficiency, have a longitudinal positive effect, and can be incorporated into existing interventions.

Does quality matter?

Policy makers, practitioners and researchers have rarely considered the importance of the quality of interaction between adults and children in relation to literacy, whether it be word games or reading books. Theories of the development of pre-literacy skills in children suggest that the quality of the interaction is of great importance because children's skills progress faster and more easily in the course of such learning interaction, which is characterized by empathetic, responsive and under-involved adults. When implementing systematic, evidence-based remedial interventions aimed at early literacy development, the quality of these interventions by the teacher can vary significantly, and these differences, apparently, are the cause of a significant difference in the level of literacy of children. When we develop policies and services to serve young children to reduce the risk of reading difficulties through remedial programs, we must ensure that children's relationships and interactions with adults are of high quality, providing a context within which knowledge, skills and interests are developed. .

When we develop policies and services to serve young children to reduce the risk of reading difficulties through remedial programs, we must ensure that children's relationships and interactions with adults are of high quality, providing a context within which knowledge, skills and interests are developed. .

Literature

- National Assessment of Education Progress. The Nation's Report Card. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/. Accessed February 4, 2005.

- Storch SA, Whitehurst GJ. Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology 2002;38(6):934-947.

- Juel C, Griffith PL, Gough PB. Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology 1986;78(4):243-255.

- Gough PB, Tunmer WE. Decoding, reading, and reading disability. RASE: Remedial and Special Education 1986;7(1):6-10.

Learn more