Literacy milestones by age

Reading Milestones (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Nemours BrightStart!

en español Hitos en la lectura

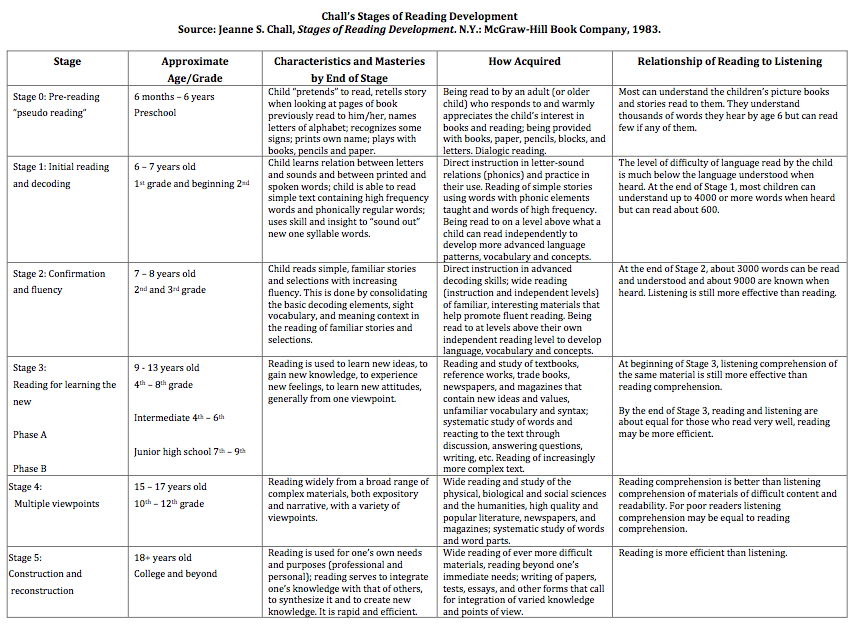

This is a general outline of the milestones on the road to reading success. Keep in mind that kids develop at different paces and spend varying amounts of time at each stage. If you have concerns, talk to your child's doctor, teacher, or the reading specialist at school. Getting help early is key for helping kids who struggle to read.

Parents and teachers can find resources for children as early as pre-kindergarten. Quality childcare centers, pre-kindergarten programs, and homes full of language and book reading can build an environment for reading milestones to happen.

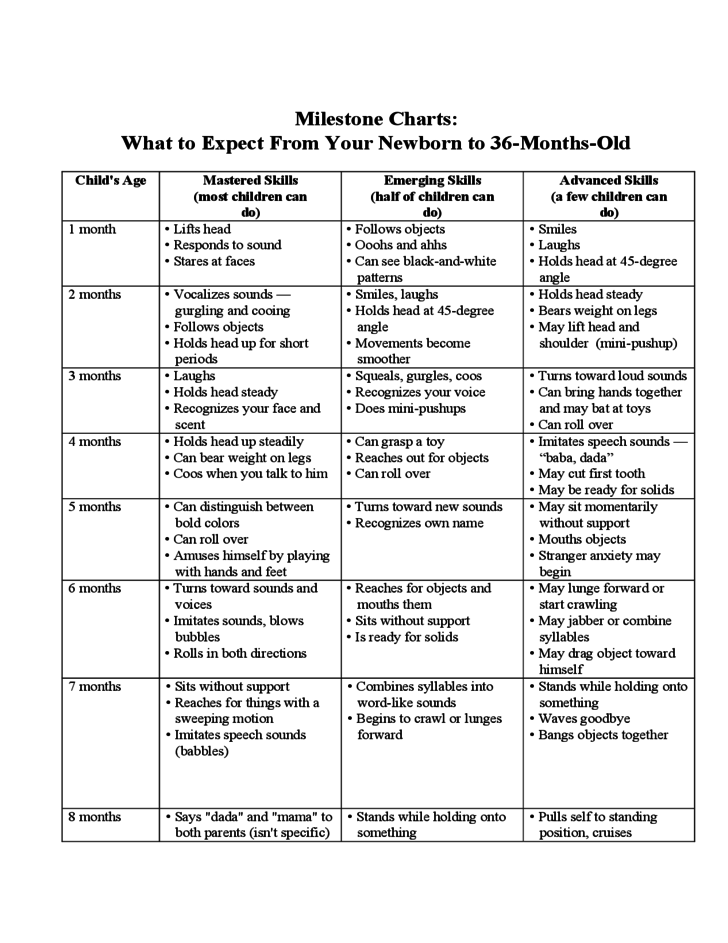

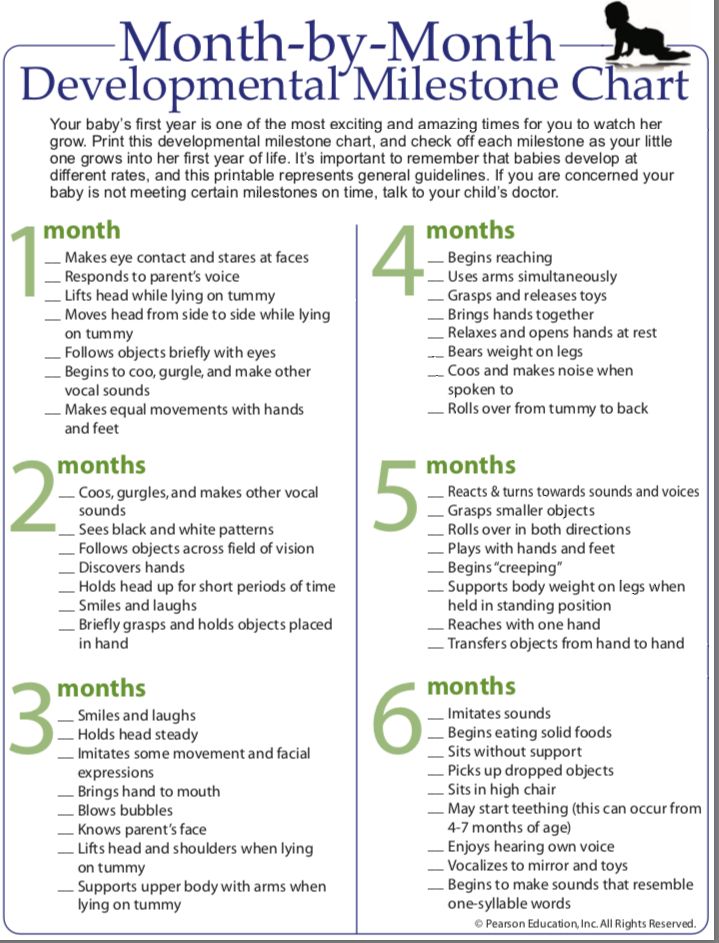

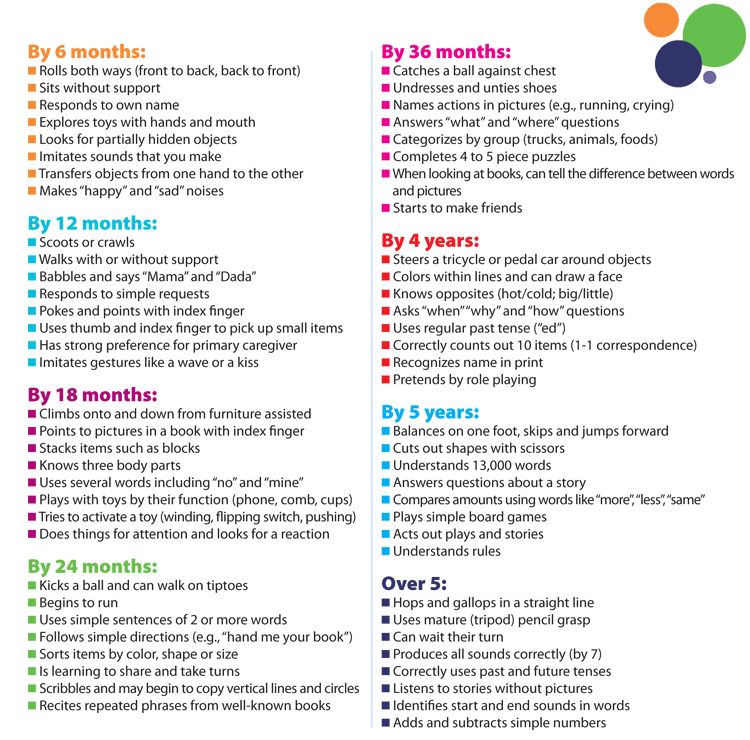

Infancy (Up to Age 1)

Kids usually begin to:

- learn that gestures and sounds communicate meaning

- respond when spoken to

- direct their attention to a person or object

- understand 50 words or more

- reach for books and turn the pages with help

- respond to stories and pictures by vocalizing and patting the pictures

Toddlers (Ages 1–3)

Kids usually begin to:

- answer questions about and identify objects in books — such as "Where's the cow?" or "What does the cow say?"

- name familiar pictures

- use pointing to identify named objects

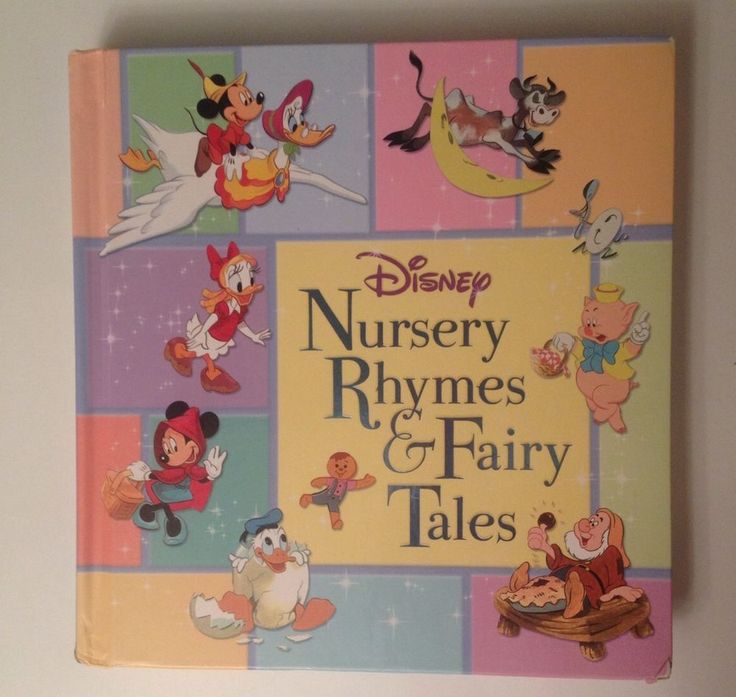

- pretend to read books

- finish sentences in books they know well

- scribble on paper

- know names of books and identify them by the picture on the cover

- turn pages of board books

- have a favorite book and request it to be read often

Early Preschool (Age 3)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore books independently

- listen to longer books that are read aloud

- retell a familiar story

- sing the alphabet song with prompting and cues

- make symbols that resemble writing

- recognize the first letter in their name

- learn that writing is different from drawing a picture

- imitate the action of reading a book aloud

Late Preschool (Age 4)

Kids usually begin to:

- recognize familiar signs and labels, especially on signs and containers

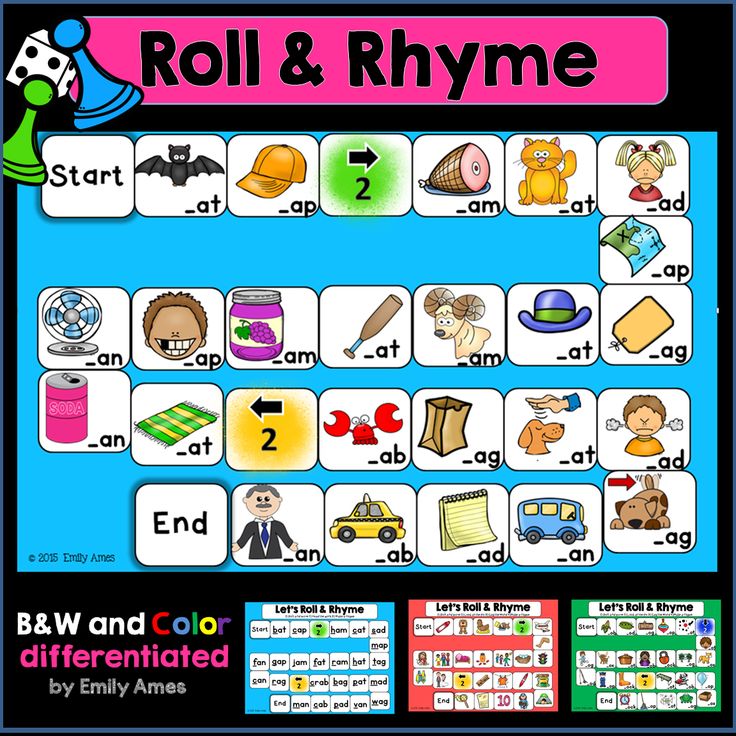

- recognize words that rhyme

- name some of the letters of the alphabet (a good goal to strive for is 15–18 uppercase letters)

- recognize the letters in their names

- write their names

- name beginning letters or sounds of words

- match some letters to their sounds

- develop awareness of syllables

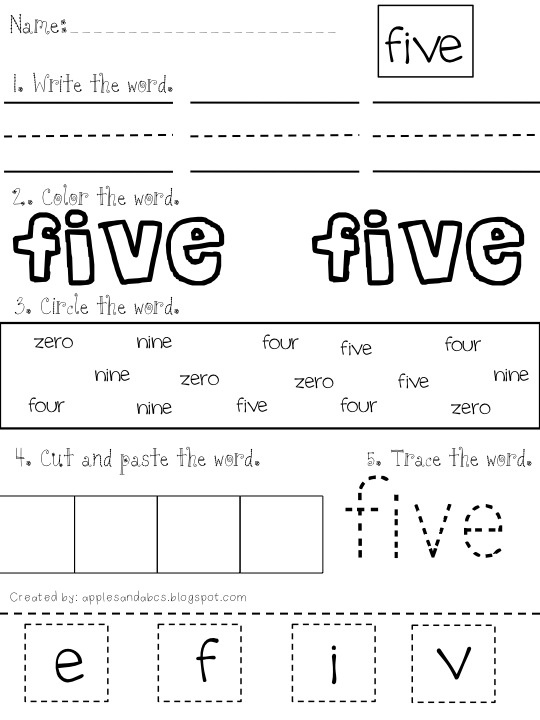

- use familiar letters to try writing words

- understand that print is read from left to right, top to bottom

- retell stories that have been read to them

Kindergarten (Age 5)

Kids usually begin to:

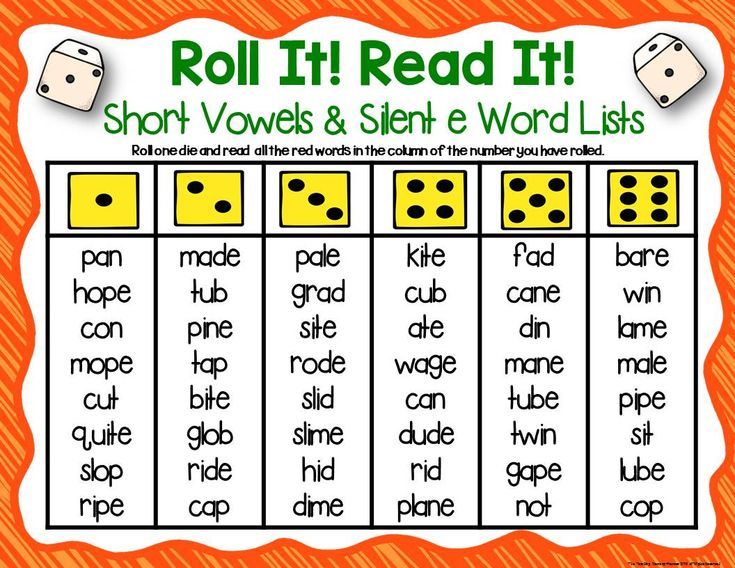

- produce words that rhyme

- match some spoken and written words

- write some letters, numbers, and words

- recognize some familiar words in print

- predict what will happen next in a story

- identify initial, final, and medial (middle) sounds in short words

- identify and manipulate increasingly smaller sounds in speech

- understand concrete definitions of some words

- read simple words in isolation (the word with definition) and in context (using the word in a sentence)

- retell the main idea, identify details (who, what, when, where, why, how), and arrange story events in sequence

First and Second Grade (Ages 6–7)

Kids usually begin to:

- read familiar stories

- "sound out" or decode unfamiliar words

- use pictures and context to figure out unfamiliar words

- use some common punctuation and capitalization in writing

- self-correct when they make a mistake while reading aloud

- show comprehension of a story through drawings

- write by organizing details into a logical sequence with a beginning, middle, and end

Second and Third Grade (Ages 7–8)

Kids usually begin to:

- read longer books independently

- read aloud with proper emphasis and expression

- use context and pictures to help identify unfamiliar words

- understand the concept of paragraphs and begin to apply it in writing

- correctly use punctuation

- correctly spell many words

- write notes, like phone messages and email

- understand humor in text

- use new words, phrases, or figures of speech that they've heard

- revise their own writing to create and illustrate stories

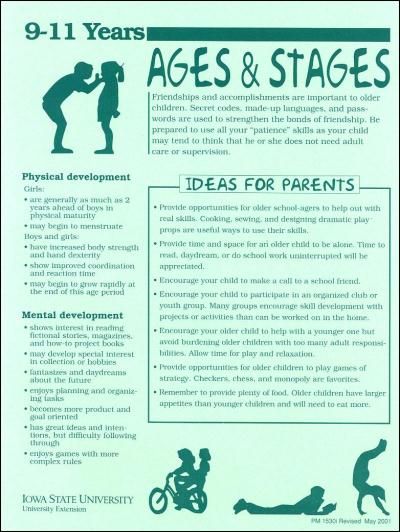

Fourth Through Eighth Grade (Ages 9–13)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore and understand different kinds of texts, like biographies, poetry, and fiction

- understand and explore expository, narrative, and persuasive text

- read to extract specific information, such as from a science book

- understand relations between objects

- identify parts of speech and devices like similes and metaphors

- correctly identify major elements of stories, like time, place, plot, problem, and resolution

- read and write on a specific topic for fun, and understand what style is needed

- analyze texts for meaning

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Date reviewed: May 2022

Reading Development and Skills by Age

Even as babies, kids build reading skills that set the foundation for learning to read. Here’s a list of reading milestones by age. Keep in mind that kids develop reading skills at their own pace, so they may not be on this exact timetable.

Babies (ages 0–12 months)

- Begin to reach for soft-covered books or board books

- Look at and touch the pictures in books

- Respond to a storybook by cooing or making sounds

- Help turn pages

Toddlers (ages 1–2 years)

- Look at pictures and name familiar items, like dog, cup, and baby

- Answer questions about what they see in books

- Recognize the covers of favorite books

- Recite the words to favorite books

- Start pretending to read by turning pages and making up stories

Preschoolers (ages 3–4 years)

- Know the correct way to hold and handle a book

- Understand that words are read from left to right and pages are read from top to bottom

- Start noticing words that rhyme

- Retell stories

- Recognize about half the letters of the alphabet

- Start matching letter sounds to letters (like knowing b makes a /b/ sound)

- May start to recognize their name in print and other often-seen words, like those on signs and logos

Kindergartners (age 5 years)

- Match each letter to the sound it represents

- Identify the beginning, middle, and ending sounds in spoken words like dog or sit

- Say new words by changing the beginning sound, like changing rat to sat

- Start matching words they hear to words they see on the page

- Sound out simple words

- Start to recognize some words by sight without having to sound them out

- Ask and answer who, what, where, when, why, and how questions about a story

- Retell a story in order, using words or pictures

- Predict what happens next in a story

- Start reading or asking to be read books for information and for fun

- Use story language during playtime or conversation (like “I can fly!” the dragon said.

“I can fly!”)

“I can fly!”)

Younger grade-schoolers (ages 6–7 years)

- Learn spelling rules

- Keep increasing the number of words they recognize by sight

- Improve reading speed and fluency

- Use context clues to sound out and understand unfamiliar words

- Go back and re-read a word or sentence that doesn’t makes sense (self-monitoring)

- Connect what they’re reading to personal experiences, other books they’ve read, and world events

Older grade-schoolers (ages 8–10 years)

- In third grade, move from learning to read to reading to learn

- Accurately read words with more than one syllable

- Learn about prefixes, suffixes, and root words, like those in helpful, helpless, and unhelpful

- Read for different purposes (for enjoyment, to learn something new, to figure out directions, etc.)

- Explore different genres

- Describe the setting, characters, problem/solution, and plot of a story

- Identify and summarize the sequence of events in a story

- Identify the main theme and may start to identify minor themes

- Make inferences (“read between the lines”) by using clues from the text and prior knowledge

- Compare and contrast information from different texts

- Refer to evidence from the text when answering questions about it

- Understand similes, metaphors, and other descriptive devices

Middle-schoolers and high-schoolers

- Keep expanding vocabulary and reading more complex texts

- Analyze how characters develop, interact with each other, and advance the plot

- Determine themes and analyze how they develop over the course of the text

- Use evidence from the text to support analysis of the text

- Identify imagery and symbolism in the text

- Analyze, synthesize, and evaluate ideas from the text

- Understand satire, sarcasm, irony, and understatement

Keep in mind that some schools focus on different skills in different grades. So, look at how a child reacts to reading, too. For example, kids who have trouble reading might get anxious when they have to read.

So, look at how a child reacts to reading, too. For example, kids who have trouble reading might get anxious when they have to read.

If you’re concerned about reading skills, find out why some kids struggle with reading.

Related topics

Reading and writing

Development of speech at an early age: mechanisms and results of learning from birth to five years

Erika Hoff, PhD

Department of Psychology, Florida Atlantic University, USA

(English). Translation: June 2016

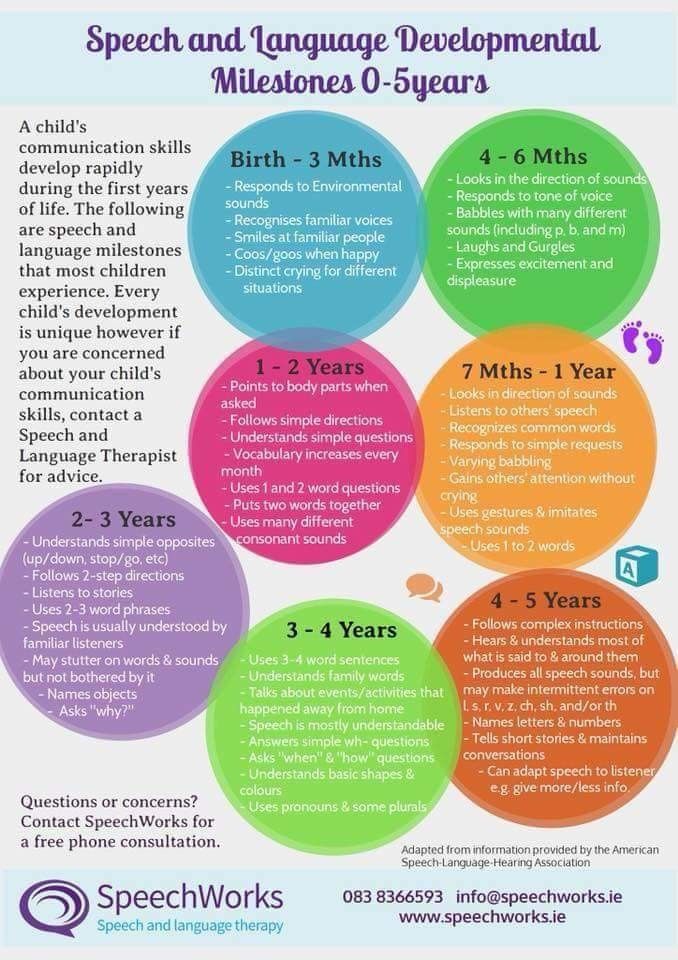

Language acquisition is one of the most outstanding achievements of early childhood. By the age of five, children have mastered the sound system and grammar of their native language to the required extent and master a vocabulary of several thousand words. This report describes the key milestones in language development that normally developing monolingual children go through in the first five years of life, and the mechanisms that have been proposed in science to explain these achievements.

By the age of five, children have mastered the sound system and grammar of their native language to the required extent and master a vocabulary of several thousand words. This report describes the key milestones in language development that normally developing monolingual children go through in the first five years of life, and the mechanisms that have been proposed in science to explain these achievements.

Item

For young children, language proficiency is important for social and academic success. 1.2 Therefore, it is essential to have descriptions of normative development that allow the identification of children with language difficulties/impairments, as well as some understanding of those mechanisms of language acquisition that can serve as a basis for optimizing the development of all children.

Issues

Although naturally all normally developed children acquire the language(s) they hear, the rate at which children develop, and therefore their levels of language proficiency, vary considerably at each age. One of the goals of research in this area is to understand the role of innate abilities and environmental conditions in explaining the universality of language acquisition as a fact, as well as the variability in speech development. nine0020 3

One of the goals of research in this area is to understand the role of innate abilities and environmental conditions in explaining the universality of language acquisition as a fact, as well as the variability in speech development. nine0020 3

Scientific context

Since ancient times, the language development of children has been a hot topic of study, and since the 1960s this problem has become central to a significant number of studies. 4 Although the frontiers of research in this area have expanded in recent years, there is still more work describing monolingual middle-class children learning English than other groups of children learning other languages. nine0008

Recent research results

The course of language development and the mechanisms underlying it are usually described separately for each of the emerging sublevels: phonological (sound system), lexical (words), and morphosyntactic (grammar), despite that these areas are closely interrelated both in language development and in practical language proficiency.

Phonological development . Newborns have the ability to hear and distinguish speech sounds. nine0020 5 During the first year of life, they begin to better distinguish by ear the distinctive features of the sound structure of their language, and become insensitive to acoustic features that are not related to their language. This tuning of speech perception in relation to the language of the environment is the result of a learning process in which infants form mental categories of speech sounds around clusters of the most frequently occurring acoustic signals. These categories subsequently direct perception in such a way that variation within the category is ignored, and intercategory variation provokes an increase in attention. nine0020 6.7

The first sounds babies make are screams and noises that are not like speech sounds. Major milestones in the preverbal development of the vocal apparatus include the production of canonical syllables (well-formed combinations of consonants and vowels), which appear at 6-10 months of age; they are soon followed by a reduplicated coo (repetition of syllables). When the first words appear, they use the same sounds and contain the same number of sounds and syllables as the sound sequences in the previous humming stage. nine0020 8 One of the processes that seems to contribute to early phonological development is the active attempts of the infants themselves to reproduce the sounds they hear. It is possible that while cooing, babies learn to recognize the correspondence between the actions of their speech apparatus and the sounds that are produced. The conclusion about the significant role of feedback follows from the results of studies that demonstrate that children with hearing impairment master the canonical hum with a delay. As it turns out, by about 18 months, children develop some kind of mental system for representing the sounds of their native language and their production within the limits of articulatory possibilities available to them. At this stage, the production of speech sounds becomes consistent and uniform in various words, which contrasts with the previous period, in which the sound form of each word was a separate mental unit.

When the first words appear, they use the same sounds and contain the same number of sounds and syllables as the sound sequences in the previous humming stage. nine0020 8 One of the processes that seems to contribute to early phonological development is the active attempts of the infants themselves to reproduce the sounds they hear. It is possible that while cooing, babies learn to recognize the correspondence between the actions of their speech apparatus and the sounds that are produced. The conclusion about the significant role of feedback follows from the results of studies that demonstrate that children with hearing impairment master the canonical hum with a delay. As it turns out, by about 18 months, children develop some kind of mental system for representing the sounds of their native language and their production within the limits of articulatory possibilities available to them. At this stage, the production of speech sounds becomes consistent and uniform in various words, which contrasts with the previous period, in which the sound form of each word was a separate mental unit. nine0020 9 The processes underlying this development are not fully understood.

nine0020 9 The processes underlying this development are not fully understood.

Vocabulary development . Babies understand the first word as early as 5 months of age, speak their first words between 10 and 15 months, their active vocabulary reaches 50 words at about 18 months and increases to 100 words by 20 to 21 months. 10 Vocabulary development then proceeds so rapidly that keeping track of how many words children are learning becomes a difficult task. It has been estimated that the average six-year-old child has a vocabulary of 14,000 words. nine0020 11

Vocabulary acquisition has many components and mechanisms. 12 Infants use "statistical learning" procedures a to track the likelihood that sounds appear together and thereby segment a continuous stream of speech into individual words. 13 The ability to capture these sequences of sounds, known as phonological memory, comes into play as units of the mental lexicon are created. nine0020 14 In solving the task of matching a first encountered word with its intended referent, children are guided by their abilities to enable them to use socially determined inference mechanisms (i.e., speakers are likely to talk about things they look at), 15 cognitive representations of the world (learning some words required projecting new words onto existing concepts), 16 and one's own prior linguistic knowledge (i.e., the structure of the sentence in which the new word appears offers clues to the meaning of the word). nine0020 17 Full mastery of the meanings of words may also require the formation of new concepts. 18

nine0020 14 In solving the task of matching a first encountered word with its intended referent, children are guided by their abilities to enable them to use socially determined inference mechanisms (i.e., speakers are likely to talk about things they look at), 15 cognitive representations of the world (learning some words required projecting new words onto existing concepts), 16 and one's own prior linguistic knowledge (i.e., the structure of the sentence in which the new word appears offers clues to the meaning of the word). nine0020 17 Full mastery of the meanings of words may also require the formation of new concepts. 18

Development of the morphosyntactic sphere . Children begin to make short sentences of two, then three or more words around the age of 24 months. The first children's sentences are combinations of significant parts of speech, which often lack auxiliary parts of speech (for example, articles and prepositions) and word endings (for example, plural endings and tense markers). As children gradually master the grammar of their native language, they develop the ability to make longer and more grammatically complete sentences. Compound sentences (that is, sentences with multiple clauses) usually begin shortly before the child is 2 years old, and this skill is completed by the age of 4. As a rule, perception precedes production. nine0020 4

As children gradually master the grammar of their native language, they develop the ability to make longer and more grammatically complete sentences. Compound sentences (that is, sentences with multiple clauses) usually begin shortly before the child is 2 years old, and this skill is completed by the age of 4. As a rule, perception precedes production. nine0020 4

The mechanism responsible for development in the field of grammar is one of the most actively discussed topics in the field of children's language learning. There is an assertion that children begin language acquisition based on innate knowledge of the structure of the language, and that it is impossible to master the language in any other way. However, it is also clear that already in infancy, children are able to recognize abstract language constructs in the speech they hear. 19 There is strong evidence that children who hear speech more often and who hear structurally more complex speech acquire grammar faster than children who have less such experience 3. 20 - all this indicates that language experience plays a significant role in the development of speech in children.

20 - all this indicates that language experience plays a significant role in the development of speech in children.

Unexplored areas

A gap or inconsistency in this area is found between the desire to theoretically explain the universal fact of language acquisition and the need to understand the causes of individual differences in language development for applied purposes. Related to this is the fact that there is less research on linguistic minorities and research on bilingual development than on monolingual development done on middle-class samples. This is a major gap as most standardized assessment tools are not suitable for detecting organic developmental delay in minority, low socioeconomic or multilingual children. nine0008

Conclusions

The process of language development in different children, regardless of the language, is characterized by uniformity, which serves as an indication of the universal biological basis of this human ability. The pace of language development varies widely, but it depends on the amount and nature of children's language experience, as well as on the children's ability to use this experience.

The pace of language development varies widely, but it depends on the amount and nature of children's language experience, as well as on the children's ability to use this experience.

Recommendations

Children with normal developmental abilities need only the experience of conversational interaction in order to acquire language. However, many children may be missing out on conversational experiences that would maximize their language development. Parents should be encouraged to treat their young children as companions from infancy. Educators and policy makers need to understand that children's language skills reflect not only their cognitive abilities, but also the opportunities to hear and use language provided by those around them. nine0008

Literature

- Black B, Logan A. Links between communication patterns in mother-child, father-child, and child-peer interactions and children’s social status. Child Development 1995;66(1):255-271.

- Morrison F, Bachman H, Connor C. Improving literacy in America: Guidelines from research . New Haven: Yale University Press; 2005.

- Hoff E. How social contexts support and shape language development. nine0046 Developmental Review 2006;26(1):55-88.

- Hoff E. Language development . 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2009.

- Aslin RN, Jusczyk PW, Pisoni D. Speech and auditory processing during infancy: Constraints on and precursors to language. In: Damon W, ed-in-chief. Handbook of child psychology . 5 th Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998: 147-198. Kuhn D, Siegler RS, eds. Cognition, perception, and language. Vol 2.

- Kuhl PK, Conboy B, Padden D, Nelson T, Pruitt J. Early speech perception and later language development: Implications for the “critical period.” Language Learning and Development 2005;1(3-4):237-264.

- Werker JF, Curtin S. PRIMIR: A developmental framework of infant speech processing.

Language Learning and Development 2005;1(2):197-234.

Language Learning and Development 2005;1(2):197-234. - Fagan MK. Mean Length of Utterance before words and grammar: Longitudinal trends and developmental implications of infant vocalizations. nine0046 Journal of Child Language 2009; 36(3):495-527.

- Stoel-Gammon C, Sosa AV. Phonological development. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 238-256.

- Pine J M. Variation in vocabulary development as a function of birth order. Child Development 1995;66(1):272-281.

- Templin M. Certain language skills in children, their development and interrelationships. nine0047 Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1957.

- Diesendruck, G. Mechanisms of word learning. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 257-276.

- Saffran JR, Thiessen ED.

Domain-general learning capacities. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing LTD; 2007: 68-86.

Domain-general learning capacities. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing LTD; 2007: 68-86. - Gathercole SE. Nonword repetition and word learning: The nature of the relationship. nine0046 Applied Psycholinguistics 2006;27(4):513-543.

- Baldwin D, Meyer M. How inherently social is language? In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 87-106.

- Poulin-Dubois D, Graham SA. Cognitive processes in early word learning. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 191-211.

- Naigles LR, Swensen LD. Syntactic supports for word learning In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. nine0046 Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 212-232.

- Carey S. The origin of concepts .

New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. - Gerken L. Acquiring linguistic structure. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 173-190.

- Vasilyeva M, Waterfall H, Huttenlocher J. Emergence of syntax: Commonalities and differences across children. nine0046 Developmental Science 2008;11(1):84-97.

Note:

a “statistical learning” in infants is a theory put forward by Jenny Saffran and colleagues (Saffran, Aslin, & Newport, 1996) that infants have the ability to use statistical information from their environment to when self-learning language elements, for example, words.

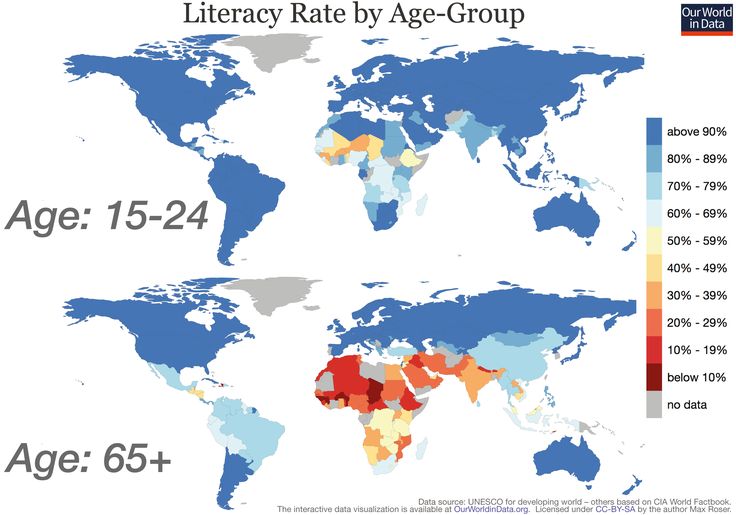

Elimination of illiteracy in the USSR

The campaign to eradicate illiteracy (from 1919 to the early 1940s) – mass literacy education for out-of-school adults and adolescents – was a unique and largest social and educational project in the entire history of Russia.

Illiteracy, especially among the rural population, was rampant. The 1897 census showed that out of 126 million men and women registered during the survey, only 21.1% of them were literate. In the almost 20 years since the first census, the literacy rate has hardly changed: 73% of the population (over 9years) were simply illiterate. In this aspect, Russia was the last in the list of European powers.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the issue of universal education was not only actively discussed in society and the press, but also became an obligatory item on the programs of almost all political parties.

The Bolshevik Party, which won in October 1917, soon began to implement this program: already in December of the same year, an out-of-school department was created in the People's Commissariat of Education of the RSFSR (A.V. Lunacharsky became the first People's Commissar of Education) under the leadership of N.K. Krupskaya (since 1920 g. - Glavpolitprosvet).

- Glavpolitprosvet).

Actually, the literacy campaign itself began later: on December 26, 1919, the Council of People's Commissars (SNK) adopted a decree "On the elimination of illiteracy among the population of the RSFSR." In the first paragraph of the decree, compulsory literacy education in the native or Russian language (optional) was announced for citizens aged 8 to 50, in order to provide them with the opportunity to “consciously participate” in the political life of the country.

Concern for the elementary education of the people and the priority of this task are easily explained - first of all, literacy was not a goal, but a means: "mass illiteracy was in blatant contradiction with the political awakening of citizens and made it difficult to carry out the historical tasks of transforming the country on socialist principles." The new government needed a new person who fully understood and supported the political and economic slogans, decisions and tasks set by this government. In addition to the peasantry, the main “target” audience of the educational program were workers (however, the situation here was relatively good: the occupational census 1918 showed that 63% of urban workers (over 12) were literate).

In addition to the peasantry, the main “target” audience of the educational program were workers (however, the situation here was relatively good: the occupational census 1918 showed that 63% of urban workers (over 12) were literate).

In a decree signed by the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars V.I. Ulyanov (Lenin) declared the following: each settlement, where the number of illiterates was more than 15, had to open a literacy school, it is also a point for the elimination of illiteracy - "likpunkt", training went on for 3-4 months. It was recommended to adapt all kinds of premises for likpunkts: factory, private houses and churches. Students were given two hours off their work day. nine0008

The People's Commissariat of Education and its departments could recruit for work in the educational program "in the order of labor service the entire literate population of the country" (not drafted into the army) "with payment for their work according to the norms of educational workers. " Those who evaded the execution of decree orders were threatened with criminal liability and other troubles.

" Those who evaded the execution of decree orders were threatened with criminal liability and other troubles.

Apparently, a year after the adoption of the decree, no noticeable actions were taken to implement it, and a year later, on July 19, 1920, a new decree appeared - on the establishment of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for the Elimination of Illiteracy (VChK L / B), and also its departments "in the field" (they were called "gramcheka") - now the commission was engaged in the general management of work. At the Cheka l / b there was a staff of traveling instructors who helped their districts in their work and monitored its implementation. nine0008

What exactly was meant by “illiteracy” in the system of educational programs?

First and foremost, it was the narrowest understanding - alphabetic illiteracy: at the initial stage of liquidation, the goal was to teach people the techniques of reading, writing and simple counting. A graduate of the Likpunkt (now such a person was called not illiterate, but semi-literate) could read “a clear printed and written font, make brief notes necessary in everyday life and in official affairs”, could “write down whole and fractional numbers, percentages, understand diagrams” , as well as "in the main issues of building the Soviet state", that is, he was guided in modern socio-political life at the level of learned slogans. nine0008

nine0008

True, often an illiterate person, having returned to his usual life (it was harder for women), forgot the knowledge and skills acquired in the educational center. “If you don’t read books, you will soon forget your diploma!” - menacingly, but rightly warned the propaganda poster: up to 40% of those who graduated from the likpunkt returned there again.

Schools for the semi-literate have become the second step in the system of education for workers and peasants. The learning objectives were more extensive: the foundations of social science, economic geography and history (from the ideologically "correct" position of Marxist-Leninist theory). In addition, in the countryside, it was supposed to teach the principles of agro- and zootechnics, and in the city - polytechnical sciences. nine0008

In November 1920, about 12,000 literacy schools were operating in 41 provinces of Soviet Russia, but their work was not fully established, there were not enough textbooks or methods: the old alphabets (mainly for children) were categorically unsuitable for new people and new needs. The liquidators themselves were also lacking: they were required not only to teach the basics of science, but also to explain the goals and objectives of building the Soviet economy and culture, to conduct conversations on anti-religious topics and to propagate - and explain - the elementary rules of personal hygiene and the rules of social behavior. nine0008

The liquidators themselves were also lacking: they were required not only to teach the basics of science, but also to explain the goals and objectives of building the Soviet economy and culture, to conduct conversations on anti-religious topics and to propagate - and explain - the elementary rules of personal hygiene and the rules of social behavior. nine0008

The eradication of illiteracy often met with resistance from the population, especially the rural population. Peasants, especially on the outskirts and "national regions", remained "darkness" (curious reasons for refusing to study were attributed to the peoples of the North: they believed that it was worth teaching a deer and a dog, and a person would figure it out himself).

In addition, in addition to all kinds of incentives for students: gala evenings, the issuance of scarce goods, there were many punitive measures with "excesses on the ground" - show trials - "agitation courts", fines for absenteeism, arrests. Nevertheless, the work went on. nine0008

nine0008

New primers began to be created already in the first years of Soviet power. According to the first textbooks, the main goal of the educational program is especially noticeable - the creation of a person with a new consciousness. Primers were the most powerful means of political and social propaganda: they taught to read and write according to slogans and manifestos. Among them were: “Our factories”, “We were slaves of capital ... We are building factories”, “The Soviets set 7 hours of work”, “Misha has a supply of firewood. Misha bought them at the cooperative”, “Kids need smallpox vaccination”, “Among the workers there are many consumptives. The Soviets gave the workers free treatment.” Thus, the first thing that the former “dark” person learned was that he owed everything to the new government: political rights, health care and everyday joys. nine0008

In 1920–1924, two editions of the first Soviet mass primer for adults (by D. Elkina and others) were published. The primer was called "Down with illiteracy" and opened with the famous slogan "We are not slaves, slaves are not us."

The primer was called "Down with illiteracy" and opened with the famous slogan "We are not slaves, slaves are not us."

Popular newspapers and magazines began to publish special supplements for the semi-literate. In such a leaflet-application in the first issue of the magazine "Peasant Woman" (in 1922), the content of the decree on educational program of 1919 was set out in a popular form.

, and those for the most part were illiterate. The army also created schools for the illiterate, held numerous rallies, talks, read aloud newspapers and books. Apparently, sometimes the Red Army soldiers had no choice: often a sentry was placed at the door of the training room, and according to the memoirs of S.M. Budyonny, on the backs of cavalrymen going to the front line, the commissar pinned sheets of paper with letters and slogans. Those who walked behind involuntarily learned letters and words according to the slogans "Give Wrangel!" and "Beat the bastard!". The results of the educational program campaign in the Red Army look rosy, but not very reliable: “from January to autumn 19In 20, more than 107. 5 thousand fighters mastered the letter.

5 thousand fighters mastered the letter.

The first year of the campaign did not bring any serious victories. According to the 1920 census, 33% of the population (58 million people) were literate (the criterion for literacy was only the ability to read), while the census was not universal and did not include areas where hostilities took place.

In 1922, the First All-Union Congress for the Elimination of Illiteracy was held: it was decided there, first of all, to teach literacy to workers of industrial enterprises and state farms aged 18-30 years (the training period was increased to 7-8 months). Two years later, on January 1924 - The XI All-Russian Congress of Soviets on January 29, 1924 adopted a resolution "On the elimination of illiteracy among the adult population of the RSFSR", and set the tenth anniversary of October as the date for the complete elimination of illiteracy.

In 1923, on the initiative of the Cheka l / b, a voluntary society “Down with illiteracy” (ODN) was created, which was headed by the chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Congress of Soviets of the RSFSR and the USSR M. I. Kalinin. The society published newspapers and magazines, primers, propaganda literature. According to official data, ODN grew rapidly: from 100,000 members by the end of 1923 to more than half a million in 11 thousand likpunkts in 1924, and about three million people in 200 thousand points in 1930. But according to the recollections of none other than N.K. Krupskaya, the true successes of society were far from these figures. Neither by the 10th anniversary nor by the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution (by 1932) the undertaken obligations to eradicate illiteracy were fulfilled.

I. Kalinin. The society published newspapers and magazines, primers, propaganda literature. According to official data, ODN grew rapidly: from 100,000 members by the end of 1923 to more than half a million in 11 thousand likpunkts in 1924, and about three million people in 200 thousand points in 1930. But according to the recollections of none other than N.K. Krupskaya, the true successes of society were far from these figures. Neither by the 10th anniversary nor by the 15th anniversary of the October Revolution (by 1932) the undertaken obligations to eradicate illiteracy were fulfilled.

Throughout the entire period of the campaign on educational program, official propaganda provided mainly optimistic information about the course of the process. However, there were many difficulties, especially "on the ground". The same N.K. Krupskaya, recalling her work during the campaign, often mentioned the help of V.I. Lenin: "Feeling his strong hand, we somehow did not notice the difficulties in conducting a grandiose campaign . ..". It is unlikely that local leaders felt this strong hand: there were not enough premises, furniture, textbooks and manuals for both students and teachers, and writing materials. The villages were especially poor: there they had to show great ingenuity - alphabets were made from newspaper clippings and magazine illustrations, charcoal, lead sticks, ink from beets, soot, cranberries and cones were used instead of pencils and pens. The scale of the problem is also indicated by a special section in the methodological manuals at the beginning of 1920s "How to do without paper, without pens and without pencils."

..". It is unlikely that local leaders felt this strong hand: there were not enough premises, furniture, textbooks and manuals for both students and teachers, and writing materials. The villages were especially poor: there they had to show great ingenuity - alphabets were made from newspaper clippings and magazine illustrations, charcoal, lead sticks, ink from beets, soot, cranberries and cones were used instead of pencils and pens. The scale of the problem is also indicated by a special section in the methodological manuals at the beginning of 1920s "How to do without paper, without pens and without pencils."

The 1926 census showed moderate progress in the literacy campaign. Literate was 40.7%, i.e. less than half, while in the cities - 60%, and in the village - 35.4%. The difference between the sexes was significant: 52.3% of men were literate, and 30.1% of women.

Since the late 1920s The campaign to eliminate illiteracy has reached a new level: the forms and methods of work are changing, the scope is increasing. In 1928, on the initiative of the Komsomol, an all-Union cultural campaign was launched: it was necessary to pour fresh forces into the movement, its propaganda and the search for new material means for work. There were other, unusual forms of propaganda: for example, exhibitions, as well as mobile propaganda cars and propaganda trains: they created new educational centers, organized courses and conferences, and brought textbooks. nine0008

In 1928, on the initiative of the Komsomol, an all-Union cultural campaign was launched: it was necessary to pour fresh forces into the movement, its propaganda and the search for new material means for work. There were other, unusual forms of propaganda: for example, exhibitions, as well as mobile propaganda cars and propaganda trains: they created new educational centers, organized courses and conferences, and brought textbooks. nine0008

At the same time, the methods and principles of work are becoming tougher: “emergency measures” are increasingly mentioned in order to achieve results, and the already militaristic rhetoric of the educational program is becoming more aggressive and “military”. The work was referred to only as "struggle", to the "offensive" and "storming" were added "cultural assault", "cultural alarm", "cultists". By the middle of 1930, there were a million of these cultural soldiers, and the official number of students in literacy schools reached 10 million.

A serious event was the introduction in 1930 of universal primary education: this meant that the "army" of the illiterate would cease to be replenished with teenagers.

By the mid-1930s. the official press claimed that the USSR had become a country of complete literacy - partly for this reason, one hundred percent indicators in this area were expected from the next census in 1937. There was no continuous literacy, but the data were not bad: in the population older than 9 years, there were 86% of literate men, and 66.2% of literate women. However, at the same time, there was not a single age group without illiterates - and this despite the fact that the literacy criterion in this census (as in the previous one) was low: one who could read at least syllable by syllable and write his surname was considered literate. Compared to the previous census, the progress was colossal: most of the population nevertheless became literate, children and youth went to schools, technical schools and universities, all types and levels of education became available to women. nine0008

However, the results of this census were classified, and some of the organizers and performers were repressed. The data of the next, 1939, census were initially corrected: according to them, the literacy of people aged 16 to 50 was almost 90%, so it turned out that by the end of the 1930s, about 50 million people were literate during the campaign.

The data of the next, 1939, census were initially corrected: according to them, the literacy of people aged 16 to 50 was almost 90%, so it turned out that by the end of the 1930s, about 50 million people were literate during the campaign.

Even taking into account the well-known "postscripts", this testified to the clear success of the grandiose project. Illiteracy of the adult population, although not completely eliminated, lost the character of an acute social problem, and the campaign for educational program in the USSR was officially completed. nine0008

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (1875-1933) - the first People's Commissar of Education of the RSFSR (from October 1917 to September 1929), a revolutionary (he was a member of social democratic circles since 1895), one from the leaders of the Bolsheviks, a statesman, since the 1930s. - Director of the Institute of Russian Literature of the USSR Academy of Sciences, writer, translator, fiery speaker, carrier and propagandist of conflicting views. A man who, even during the years of the Civil War, dreamed of the imminent embodiment of the ideal of the Renaissance - "a physically handsome, harmoniously developing, well-educated person who is familiar with the basics and the most important conclusions in various fields: technology, medicine, civil law, literature ...". In many ways, he himself tried to live up to this ideal, engaging in all sorts of large-scale projects: the eradication of illiteracy, political education, the construction of the principles of advanced proletarian art, the theory and foundations of public education and the Soviet school, as well as the upbringing of children. nine0008

A man who, even during the years of the Civil War, dreamed of the imminent embodiment of the ideal of the Renaissance - "a physically handsome, harmoniously developing, well-educated person who is familiar with the basics and the most important conclusions in various fields: technology, medicine, civil law, literature ...". In many ways, he himself tried to live up to this ideal, engaging in all sorts of large-scale projects: the eradication of illiteracy, political education, the construction of the principles of advanced proletarian art, the theory and foundations of public education and the Soviet school, as well as the upbringing of children. nine0008

The cultural heritage of the past, according to Lunacharsky, should belong to the proletariat. He analyzed the history of both Russian and European literature from the point of view of the class struggle. In his emotional, vivid and imaginative articles, he argued that the new literature would be the crown of this struggle, and waited for the appearance of brilliant proletarian writers.