Logic of english phonogram

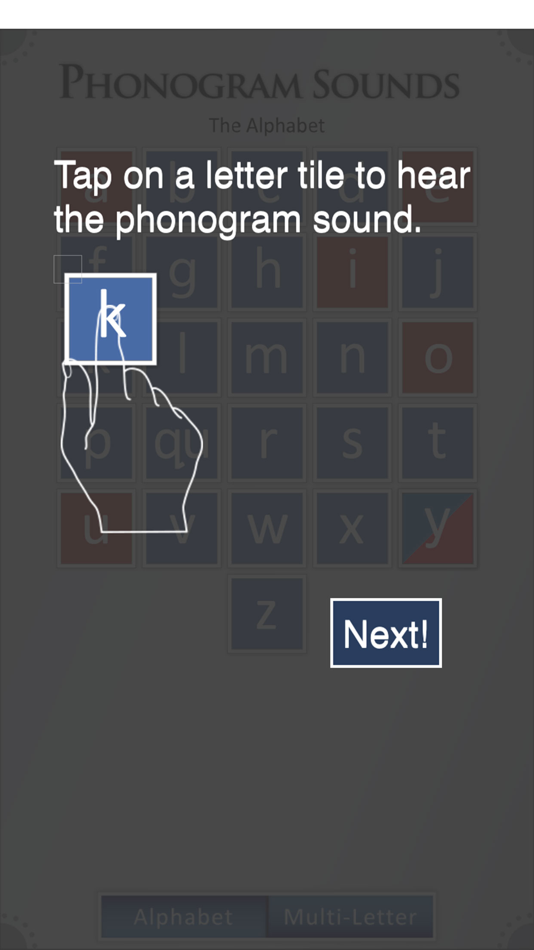

Phonics With Phonograms by Logic of English on the App Store

Description

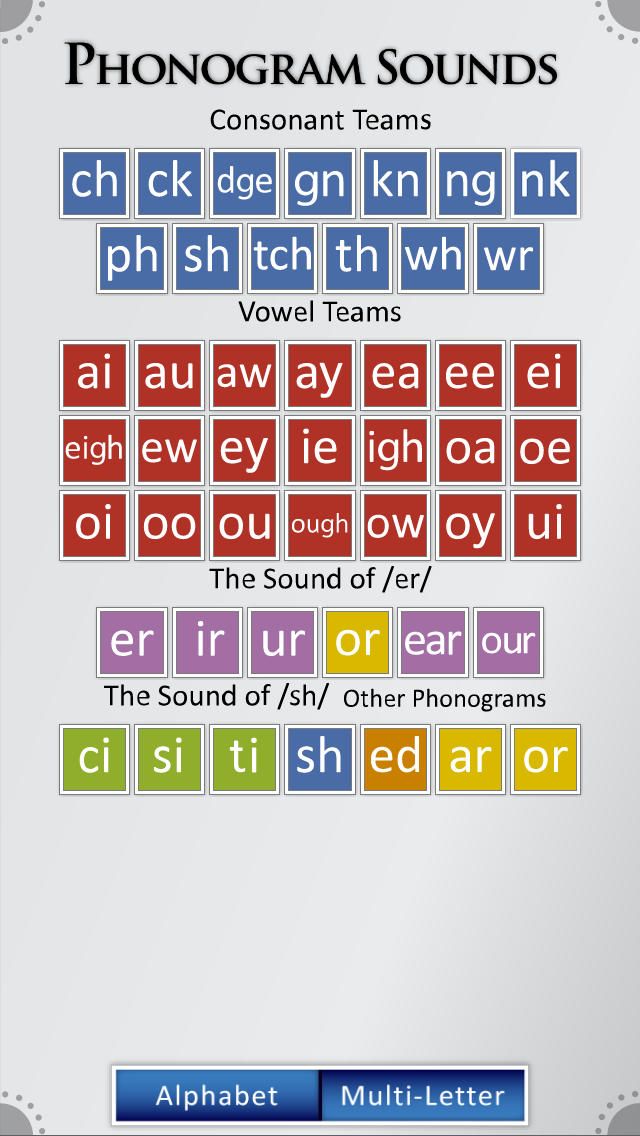

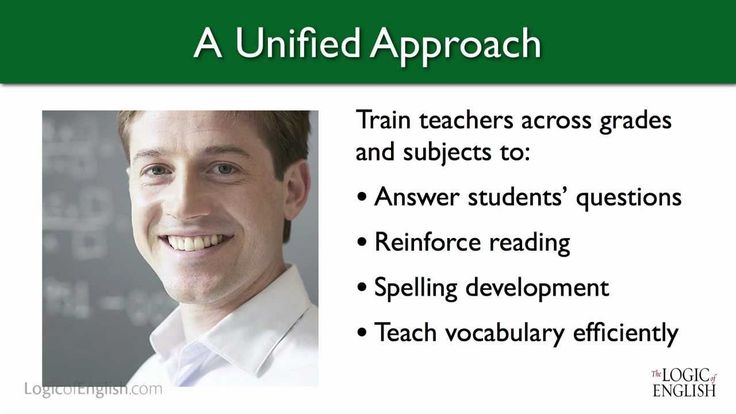

A fun, effective phonics recognition game that eliminates exceptions and provides a complete picture of the phonograms needed to read and spell!

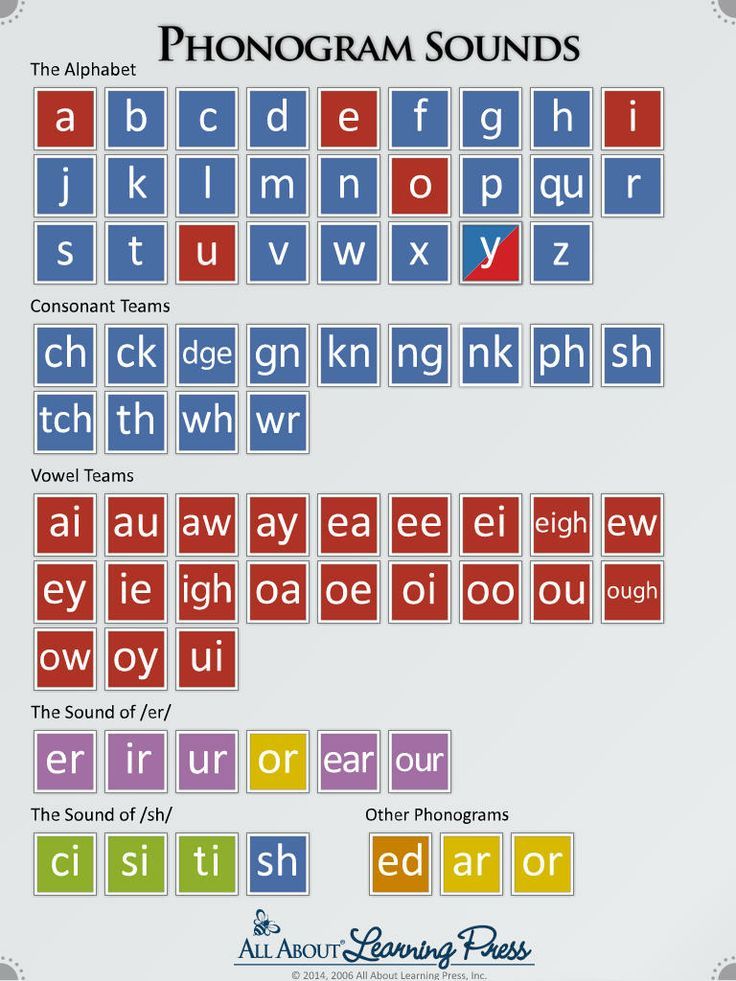

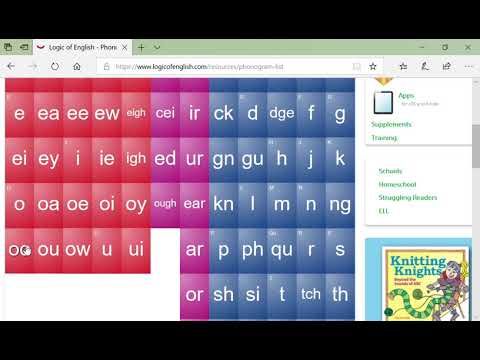

- Ten guided levels to introduce and master the 74 phonograms needed to read and spell 98% of English words.

- A fun matching game to master the phonograms.

- A simple flashcard method for quick review.

- Eliminates unnecessary exceptions by teaching all the sounds for each letter and multi-letter phonograms from the beginning.

- Select lowercase, uppercase, and multi-letter phonograms to create a custom game.

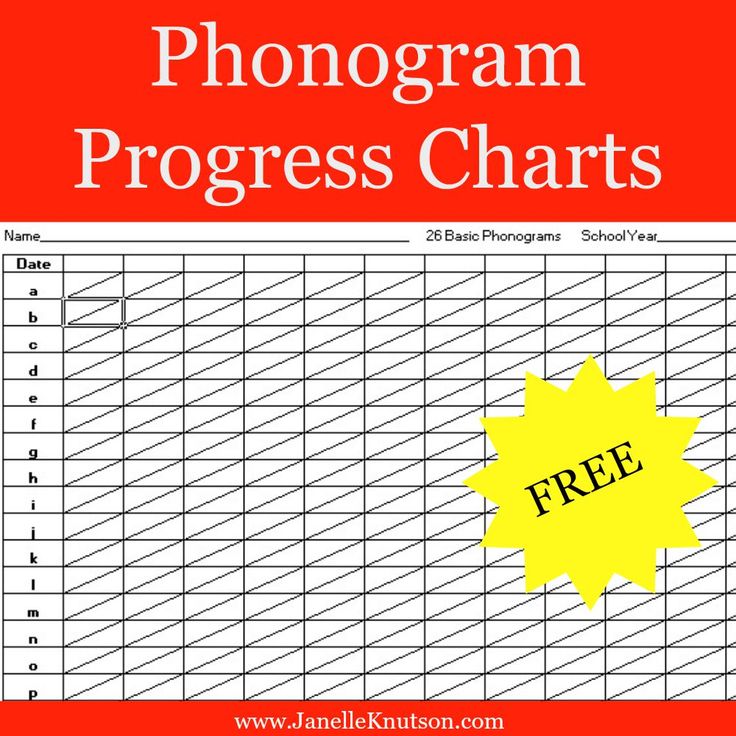

- Tracks individual progress and mastery for multiple users.

- Allows parents and teachers to see at a glance which phonograms have been mastered, which need more practice, and which have not been introduced yet.

- After a phonogram has been correctly answered five times, a star is placed on the card in the selection screen to indicate mastery.

- A fun and effective way to introduce anyone ages 2-adult to the phonograms.

- An ageless design that is loved by young children and adults alike.

- Works in both portrait and landscape mode.

- Students and teachers may create custom games to coordinate with other Orton-Gillingham based reading programs.

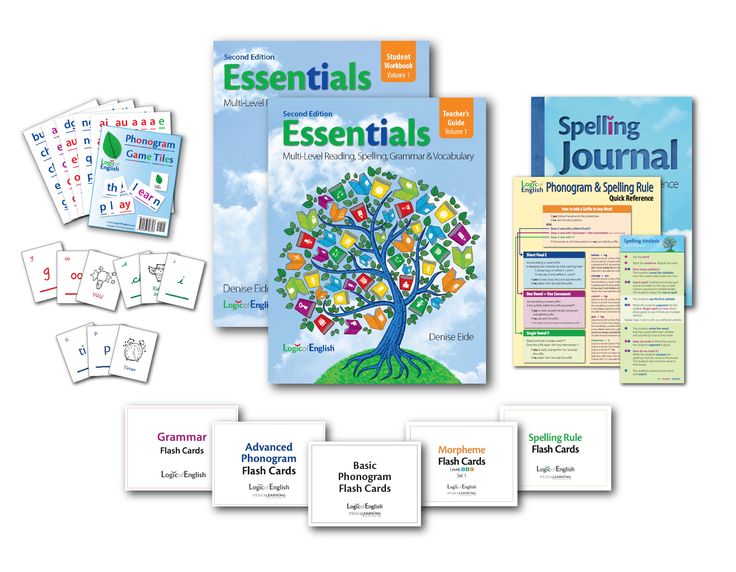

- Designed to accompany Logic of English Curriculum and Materials.

Version 1.1.2

This app has been updated by Apple to display the Apple Watch app icon.

Fixed bugs preventing the app from running in ios8. Included the /z/ sound with the x phonogram.

Ratings and Reviews

42 Ratings

Great Supplement to the full Logic Of English Curriculum

This app is a useful supplement to the complete Foundations Logic of English program we are using in our homeschool.

It helps reinforce advanced phonics with my kiddos while freeing me up to do other things, and is able to show what sounds/concepts they may need me to review with them. My only complaint is that some of the sounds are over-pronounced (the letter "w" is miss-pronounced "wuh"), a sadly common dificulty with phonics teaching resources.

A true ESL/ELL gem!!

The LOE app supports their reading program in the most accessible and common sense way possible. I like the simplicity of the app—without all the bells and whistles of other apps that look and sound good, but are low on substance. The app does exactly what it claims it will do, and actually much more, because it teaches an expanded list of phonograms that are not taught by most traditional reading programs.

Since using the LOE program and the app, my ESL students have “clicked” with their English language learning and are not as confused when they come across “exceptions to the rule” because LOE reduces exceptions to a minimum.

I can see this approach may not be for everyone because we’re entrenched in our traditional learning, but give it a try. You may find that this will be your first approach, rather than your “last resort”.

Is awesome and does exactly what it is supposed to!

This is an app designed to support a method of teaching reading and spelling that will get rid of illiteracy if implemented. It is awesome for struggling readers, dyslexics, and all those tired of hearing how hard English is, when it is not! Hence the name, Logic of English! Got for my four! What a great way to practice all the phonograms and track multiple students progress! Thank you. It is even better than I thought it would be.

Loving even more as we use! Truly a great tool to strengthen phonemic awareness! My 7 year old can't get enough!One note: found 1 error on level 3. The letter is l but the sound is d .

Please fix when you can. Thanks.

The developer, Logic of English, Inc., has not provided details about its privacy practices and handling of data to Apple.

No Details Provided

The developer will be required to provide privacy details when they submit their next app update.

Information

- Seller

- Logic of English, Inc.

- Size

- 15.5 MB

- Category

- Education

- Age Rating

- 4+

- Copyright

- © 2013 Pedia Learning Inc

- Price

- Free

- Developer Website

- App Support

You Might Also Like

A Helpful Guide For Parents

Phonograms are the foundation of your child’s reading and spelling success. But what resources do you need to teach them to your child?

But what resources do you need to teach them to your child?

While phonograms sound like an intimidating literary concept, they are actually relatively easy to teach and for kids to understand. All you need is a clear plan to get started, and that’s what we’ll help you with in this article.

However, before sharing our effective learning tips with you, let’s start by evaluating what a phonogram is.

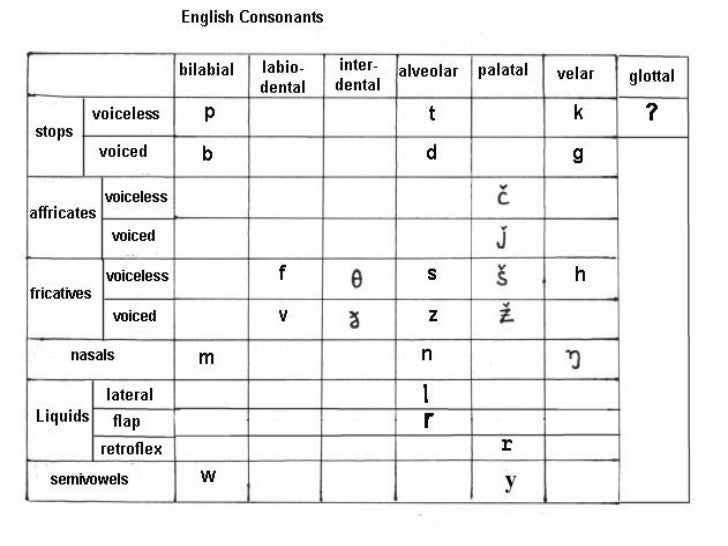

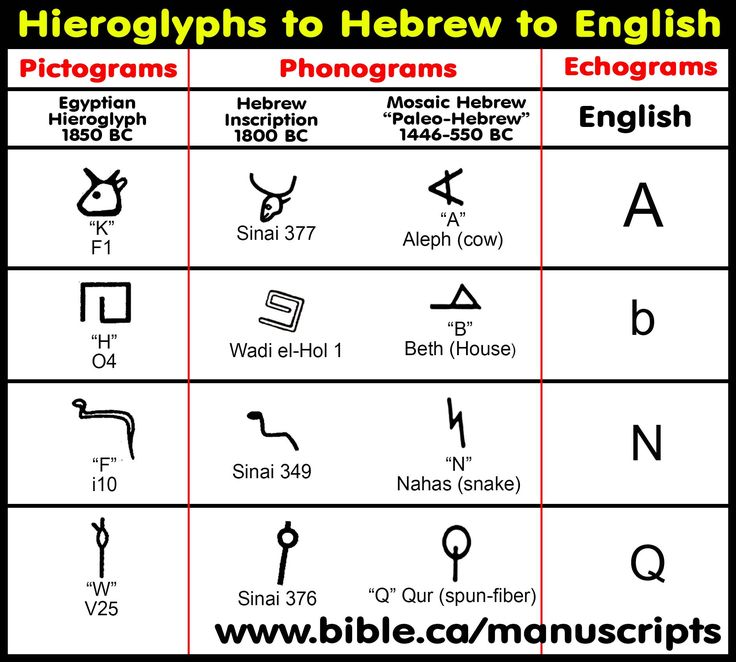

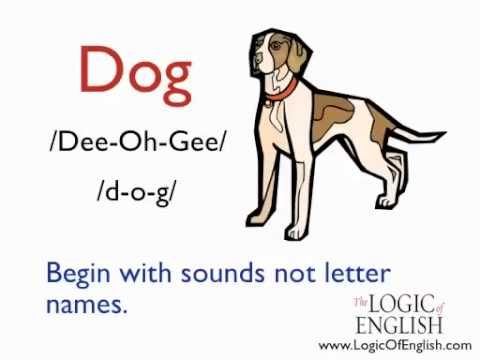

What Are Phonograms?

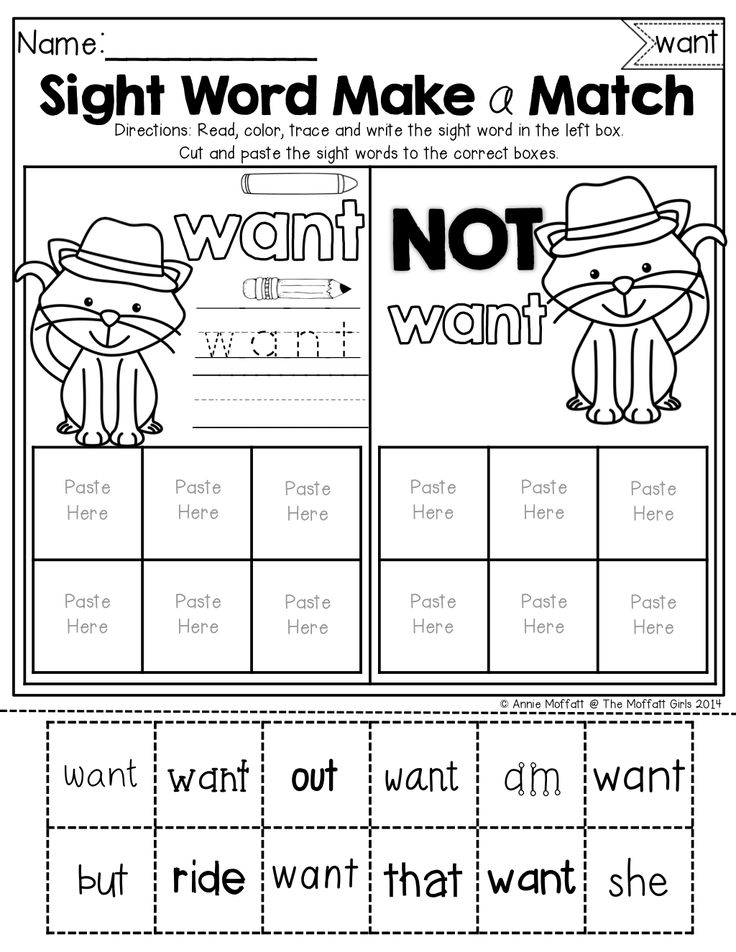

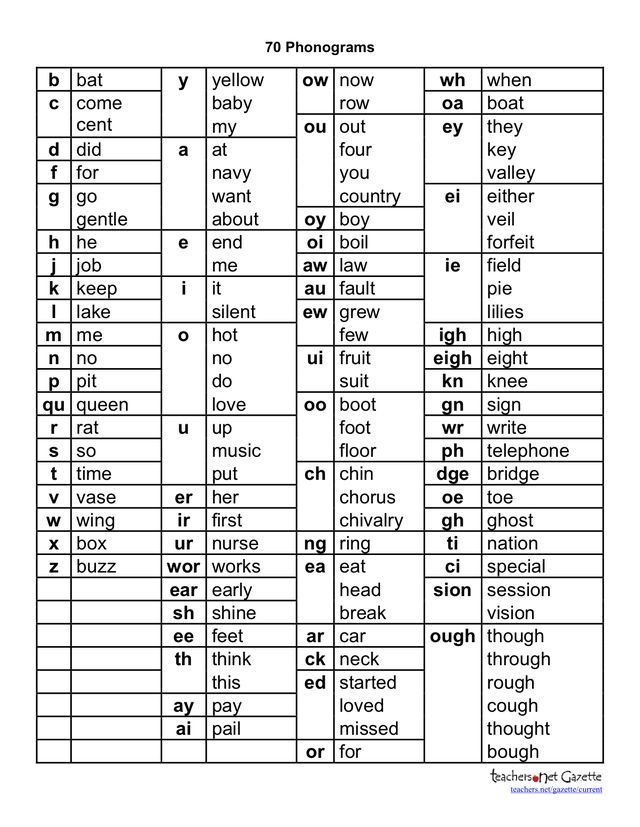

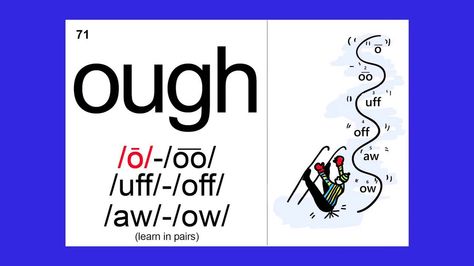

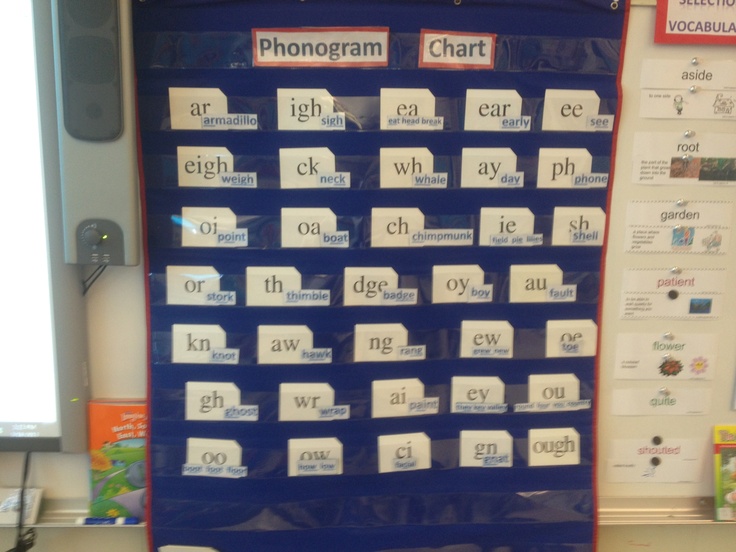

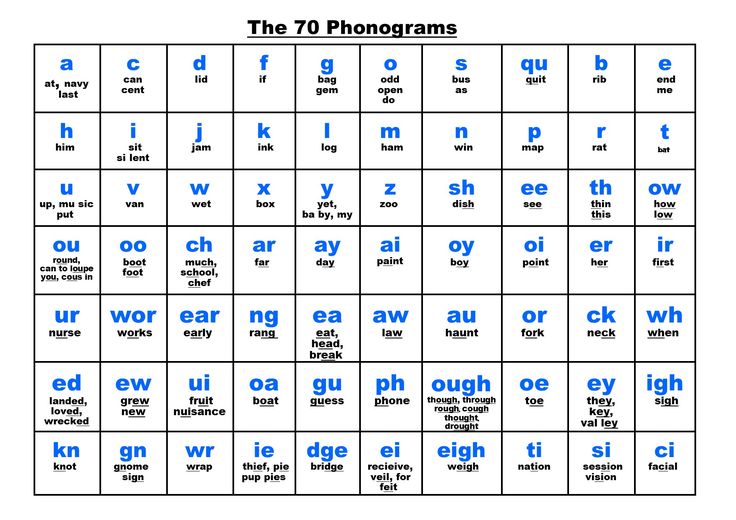

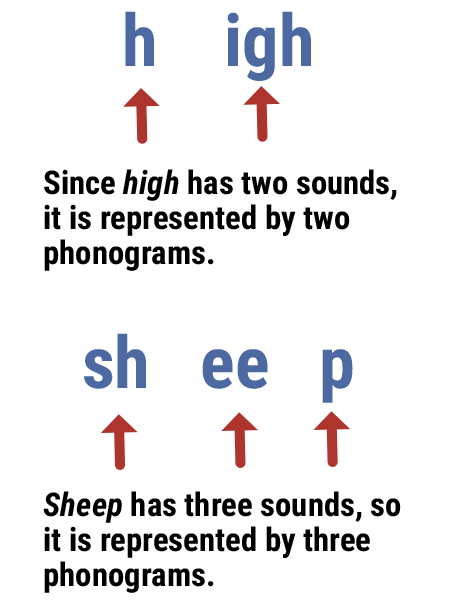

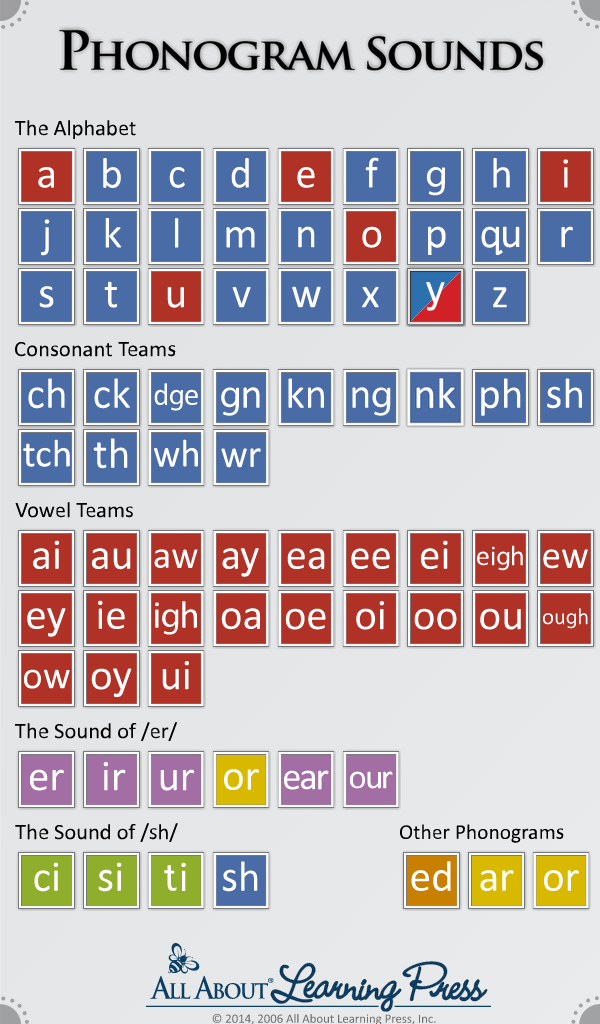

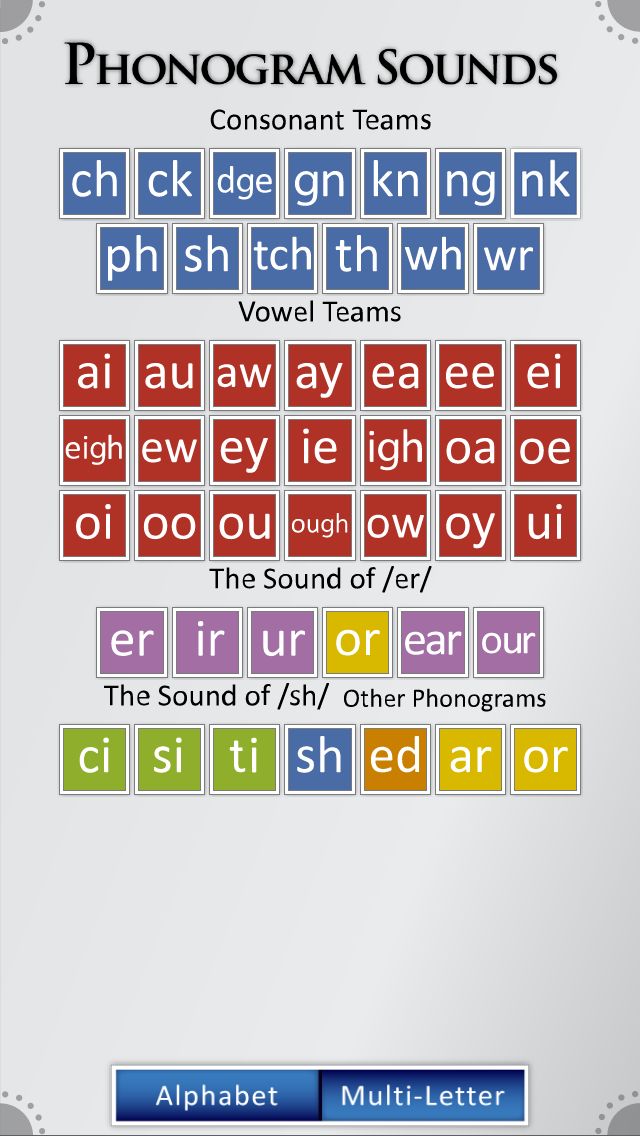

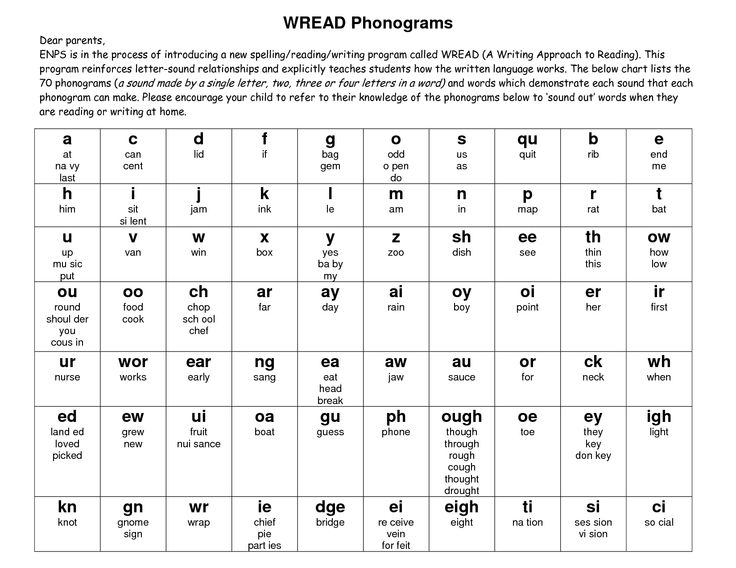

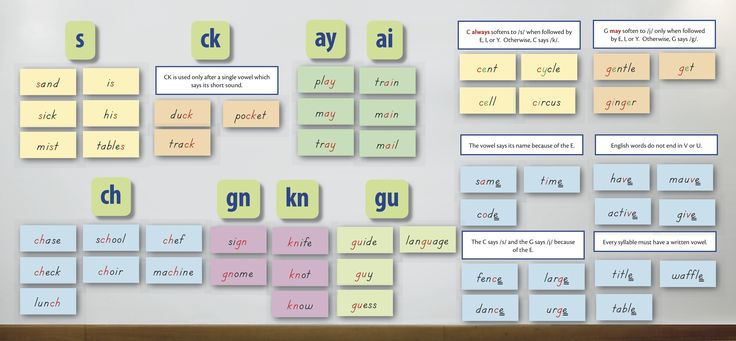

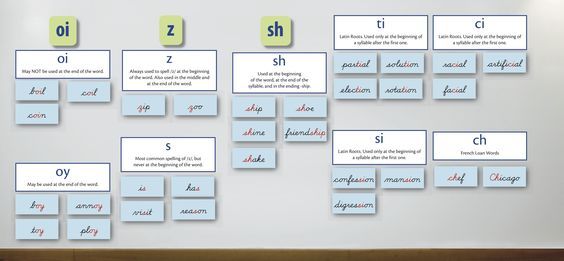

Phonograms are the letters or combinations of letters that represent a sound. Think of letter combinations such as oy, ck, th, and ch. These are common phonograms that you’ll often come across in the English language.

When a child doesn’t know these letter combinations and the sounds they make, it becomes challenging to write or spell correctly. But when they understand them, they know that “oy” makes an /oi/ sound (e.g., boy), “ck” makes a /k/ sound (e.g., pack), and so forth.

There are also letters that give different sounds depending on the word. For instance, “s” is a phonogram with an /s/ sound in some words (e.g., sing) and a /z/ sound in other words (e.g., has).

For instance, “s” is a phonogram with an /s/ sound in some words (e.g., sing) and a /z/ sound in other words (e.g., has).

The Importance Of Learning Phonograms

Phonograms are an important pre-literacy skill. They are the building blocks of words because they help make reading and spelling much easier.

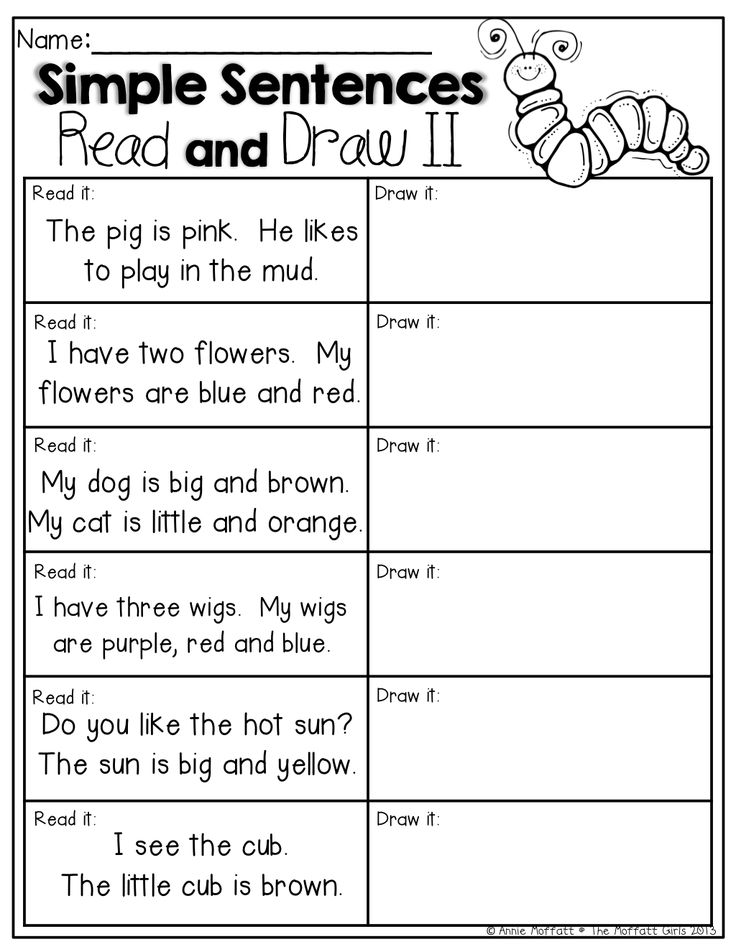

Let’s take the word cat as an example. For a child learning to spell, they will usually pronounce the individual sounds (i.e., phonemes) of the word: /c/-/a/-/t/.

This is fairly easy. So, let’s take things up a notch with the word talk. A child who understands phonograms doesn’t need to separate each letter of the word. Instead, they will pick up on the /alk/ sound and then be able to spell the word correctly: /t/-/alk/.

This is an essential skill because many words, especially longer ones, can be formed more quickly by remembering that certain letter combinations make certain sounds.

For example, we don’t pronounce the word holiday by going /h/-/o/-/l/-/i/-/d/-/a/-/y/. Sure, you can, but there are 26 letters in the English language. Imagine how much time you’d spend sounding out each letter of every word you want to spell.

Sure, you can, but there are 26 letters in the English language. Imagine how much time you’d spend sounding out each letter of every word you want to spell.

A much better strategy is to focus on segmenting the word by phonograms: /h/-/o/-/li/-/day/. Understanding phonograms makes spelling and reading fluently much easier and more efficient.

And a child who understands phonograms may have a better chance of correctly spelling words they are unfamiliar with. For example, when a child can spell winter, they have a better chance of spelling sister, mister, enter, after, etc.

Phonogram Vs. Phoneme

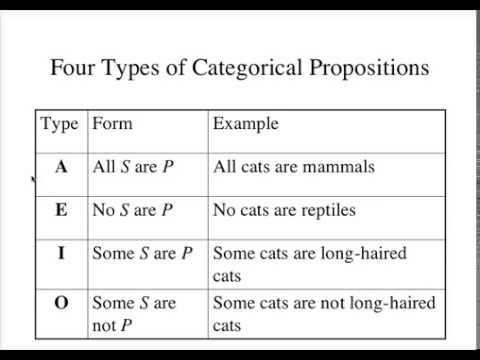

When many people think of phonograms, they often mistake them for phonemes. They both involve the individual sounds that make up a word, so they must be pretty much the same, right?

While their concepts may be closely related, there are fundamental differences between the two. Let’s take a look.

What Is A Phoneme?

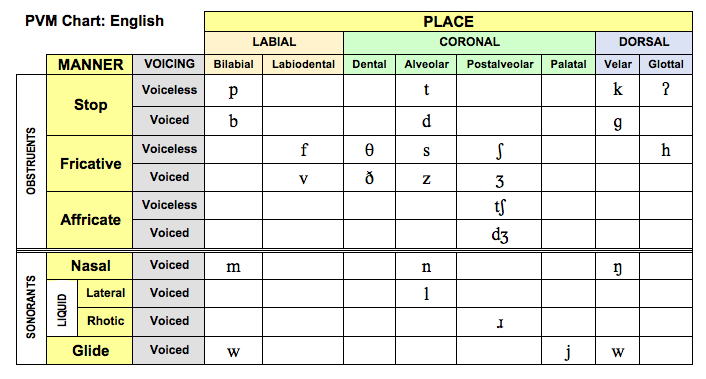

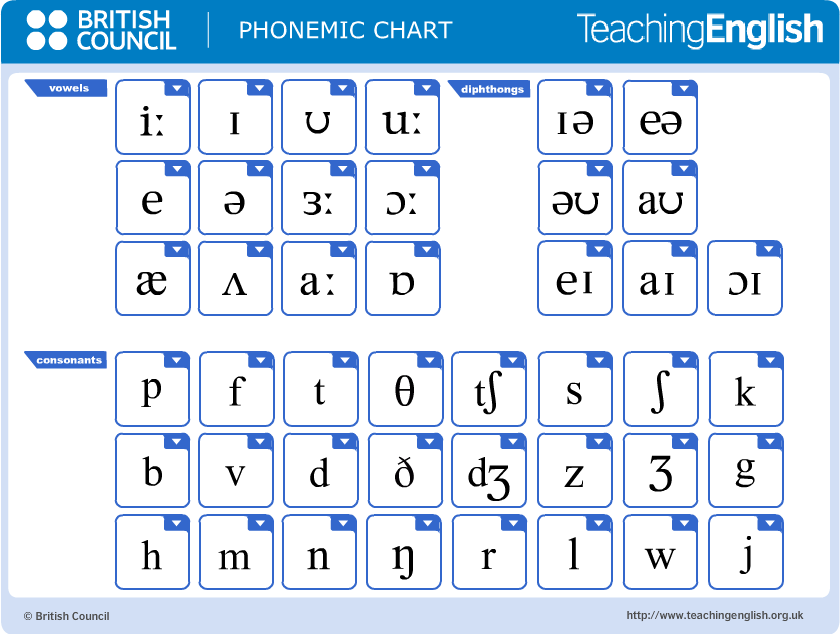

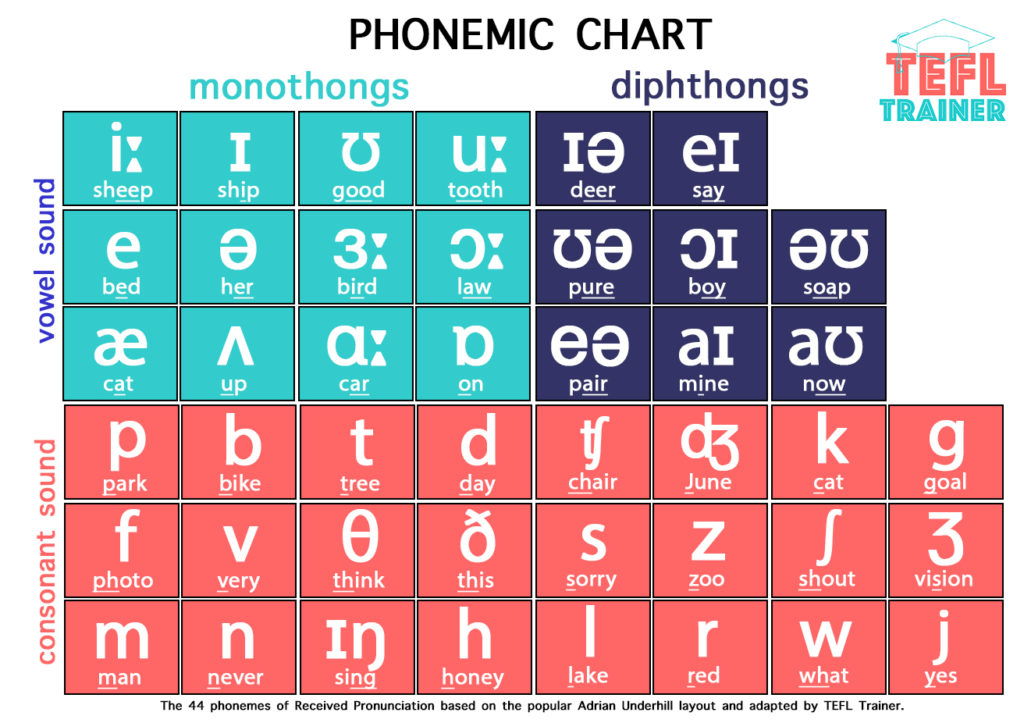

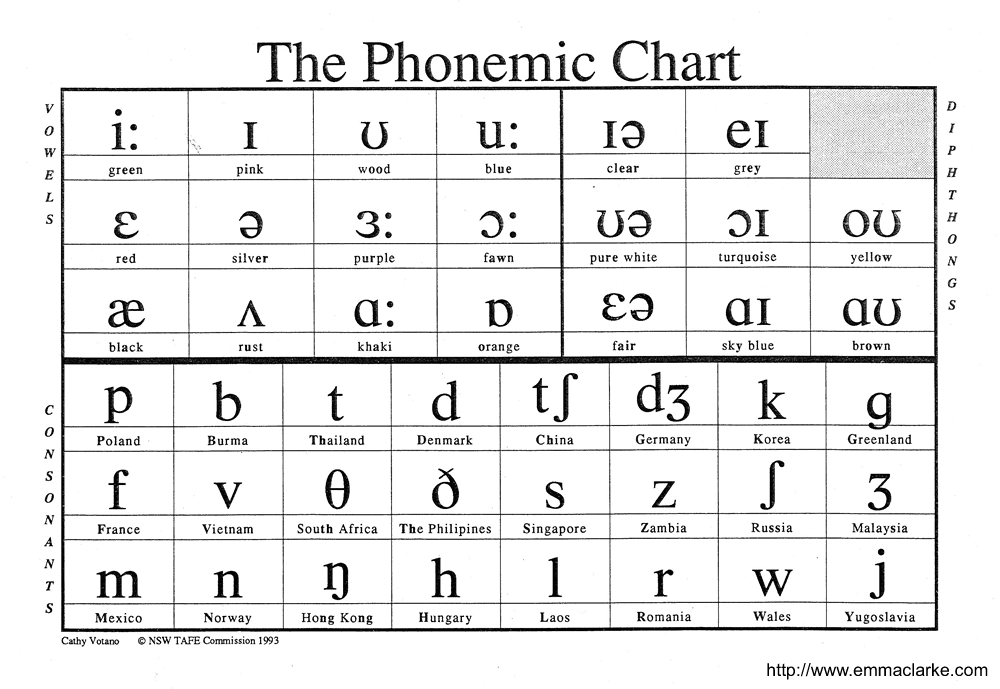

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in our spoken language. We have 44 phonemes in the English language, and we combine these individual units of sound to make words.

We have 44 phonemes in the English language, and we combine these individual units of sound to make words.

For example, from the five-letter word light, we only hear or pronounce three individual sounds: /l/-/i/-/t/.

How’s This Different From A Phonogram?

A phonogram, on the other hand, is a visual symbol that represents a speech sound. So, from the above example, the /igh/ part of the word has the /i/ phonogram.

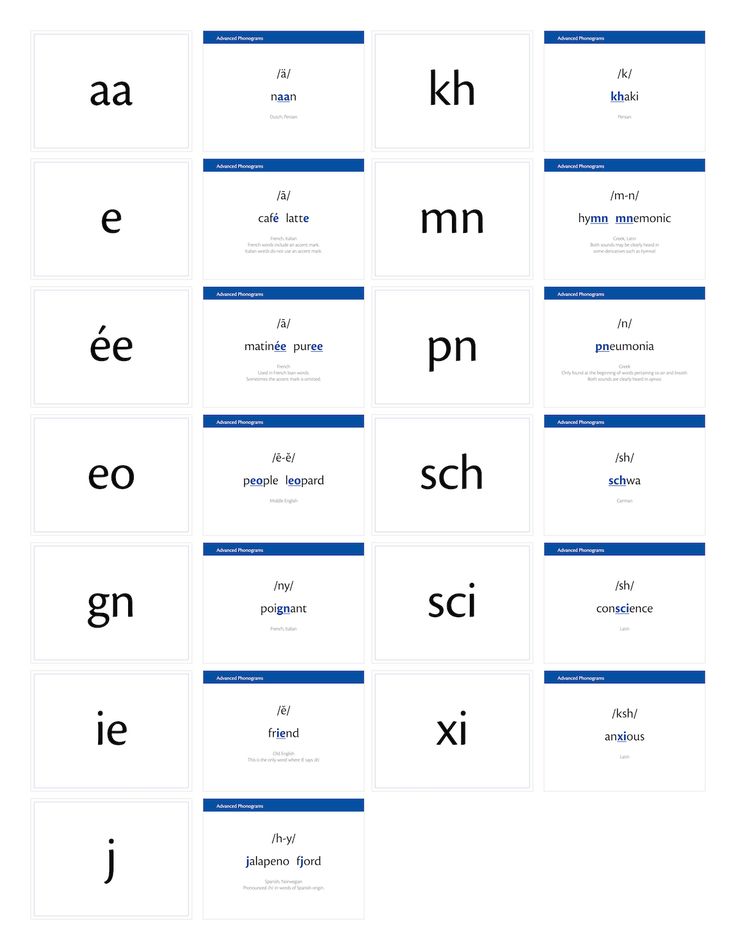

In total, there are 75 basic phonograms in the English language. We commonly use around 49 of them, some of which include /igh/, /dge/, /oo/, /dger/, /th/, /sh/, /ch/, and /ph/.

As highlighted above, these are the building blocks of reading and spelling, so the more familiar children are with these sounds and letter combinations, the more comfortable they will be when reading and spelling.

Here are a few tips to help your young learner grasp these concepts at home.

Tips For Teaching Phonograms At Home

1) Start Simple

There is no perfect pace for teaching phonograms. Some children may master the concepts and skills very quickly, while others may need a little more time.

Some children may master the concepts and skills very quickly, while others may need a little more time.

No matter where your child is on their learning journey, the best approach is to start with a few and build from there.

For example, introducing three to five phonograms at a time could be a great starting point. Once your child gets comfortable with those, you can then move on to the next three to five, and so forth.

Since there are so many, it’s OK to set the goal of introducing a certain amount each week. However, if your young learner hasn’t mastered the ones you taught them last week, give them as many days as they need before progressing to new phonograms.

This will keep them excited about learning and prevent them from becoming overwhelmed. Don’t worry about a specific timeline; they will eventually get the hang of it!

2) Read Together Regularly

Here at HOMER, we’re huge fans of early childhood reading. Not only do books expose children to incredible worlds and help with cognitive and language development (and so much more!), but reading also plays an essential role in helping children get more familiar with phonograms.

Whenever your child is reading and comes across a word they’re unfamiliar with, remember to pause and go back to the basics of phonemes and phonograms. Help them sound out the letters and letter combinations.

You can also reinforce a phonogram by highlighting other similar words your child might know. For example, if they’re learning the /ch/ sound, remind them of words they may know, such as chair, chips, chat, child, etc.

With the above tips in mind, here are a couple of activities to make learning phonograms at home fun.

Phonogram Activities

1) Phonogram Simon Says

What You’ll Need:

- 8 Index cards

- Marker

- 8 single-letter phonograms

- Crayons

What To Do:

Start by writing down eight phonograms (one on each card) with your child. As you’re writing, say the sound the letter or letter group makes. Then, have your child decorate each card in fun ways.

Once you’re done making your cards, stand on one side of the room and have your child stand on the other side. Then, hold up a card and say, “Simon says make the sound!”

Then, hold up a card and say, “Simon says make the sound!”

If your child pronounces the phonogram correctly, they take a jump toward you. If they don’t, they have to jump backward. (Note: If there’s no room for them to go backward, they can stay put.)

The goal is for your child to reach you before the deck is done!

Tip: If your child is still mastering individual letter sounds, you can play this game with single-letter phonograms instead of letter groups.

2) 52 PickUp, With A Twist

What You’ll Need:

- The same index cards from Sound-Letter Simon Says (and more if your child is ready).

What To Do:

To start playing, toss the cards in the air. Then, have your child go around the room and say the sound for every letter or phonogram that is facing up.

If they can make the sound correctly, they get to keep that card. Any cards they cannot pronounce go back to the deck. Then, it’s your turn (feel free to fake it a bit here).

Take turns going back and forth until all the cards are picked up. The person with the most cards wins!

3) Feel The Letter

What You’ll Need:

- Magnetic or foam letters

What To Do:

Start by asking your child to put their hands behind their back. Then, place a magnetic or foam letter in one of their hands and have them feel its shape.

To get a point, your child needs to tell you the letter. And to get a bonus point, they need to tell you the sound that letter makes. You and your child can take turns guessing to make it a fun competition!

Remember to keep things fun. For example, if your young learner gets a phonogram wrong, simply correct them and move on without stressing too much. The point of this game is to practice, and repetition is a great way to solidify phonogram knowledge.

One Phonogram At A Time

Working with your child to master phonograms can be a fun journey!

When practicing, remember to start simple by introducing just a few phonograms at a time before moving on to more. In addition, reading regularly together will also help reinforce all the language rules your child is learning.

In addition, reading regularly together will also help reinforce all the language rules your child is learning.

While there are many phonograms to master, try not to focus on how quickly your child is grasping them. Instead, build their confidence around each set you introduce, and they will make a little progress each day.

Armed with all these skills, they’ll soon be able to spell accurately (most of the time) and read fluently. Just wait and see!

For more on helping develop your child’s reading and spelling skills, check out our Learn & Grow app.

Author

Is there any logic in English grammar

An article was published in the journal Nature about the causes of language changes. Its authors, Mitchell Newberry, Christopher Ahearn, Robin Clark, and Joshua Plotkin, using population genetics and material from different periods of the English language, try to prove that language changes are not only conditioned, but also random. All authors of the article are professors at the University of Pennsylvania. Newberry and Plotkin are biologists, while Ahearn and Clark are involved in applying game theory to solving linguistic problems. There is no traditional linguist among them.

All authors of the article are professors at the University of Pennsylvania. Newberry and Plotkin are biologists, while Ahearn and Clark are involved in applying game theory to solving linguistic problems. There is no traditional linguist among them.

Meanwhile, the causes of language changes is one of the main questions that linguistics deals with. The conclusion reached by the authors of the article in Nature - that language changes can be not only conditioned, but also random, to put it mildly, is not new. Not only specialists, even junior students know that variability and variability are inherent in any living language. Only dead languages don't change.

Language changes are conditioned, that is, caused by a variety of factors, including random ones. Some conditioned changes are considered "laws" and are named after the great linguists who discovered them, but more often they are described in terms. Random changes, respectively, have no conditionality.

In the article, in particular, the fluctuations of the past tense form of English verbs are considered. The authors use the Corpus of Historical American English (more than 100,000 texts from 1810–2009) as a source of material. Competing forms of the past tense such as lighted / lit, waked / woke, sneaked / snuck, dived / dove, wove / weaved, smelt / smelled, wove / weaved fell into their field of vision.

As a small digression, we note that the doublet forms of the past tense became a mass phenomenon in the 13th-14th centuries, and possibly even earlier, when the English language was moving from the old system, dividing verbs into strong and weak, to a new one, in which opposition goes by regularity/irregularity. The old system collapsed because, due to phonetic and morphological changes, some classes began to combine very different colors of verbs. To this must be added the massive process of reduction that has taken hold of all parts of speech, and the need to assimilate a huge number of French borrowings, including verbs, most of which, of course, have become regular.

Against this background, a high variability of forms of the past tense arose, the echoes of which can be observed not only in the 19th century, but even now. The main direction of this development is an increase in the number of regular verbs and a reduction in irregular ones. The authors of the article also note that, as their analysis shows, regular forms will win for many verbs. Opting for irregular shapes "looks more mysterious," the article says.

But in fact there is no big mystery here. If phonetically the verb was similar to a whole group of irregular verbs (usually these are verbs of the same old class), he began to conjugate according to their type. As an example, the article gives the verb quit. It was borrowed from French, and therefore was supposed to become - and became - a regular verb: quit - quitted. But now quit is also used as the past tense, similar to verbs such as hit and split.

Another interesting example given in the article is the conjugation of the verb dive "to dive". Omitting its early history, we note that in modern English this verb should have been regular: dive - dived. But in the 20th century, the form dove becomes more and more common, which, as the authors of the article note, occurs against the backdrop of an increase in the use of the verb drive after the invention of the car. Not only are dive and drive consonant, they also denote an activity that is becoming more and more fashionable - diving and driving. Therefore, dive began to be conjugated in the same way as drive, and dictionaries have long cited the dove form as valid.

Omitting its early history, we note that in modern English this verb should have been regular: dive - dived. But in the 20th century, the form dove becomes more and more common, which, as the authors of the article note, occurs against the backdrop of an increase in the use of the verb drive after the invention of the car. Not only are dive and drive consonant, they also denote an activity that is becoming more and more fashionable - diving and driving. Therefore, dive began to be conjugated in the same way as drive, and dictionaries have long cited the dove form as valid.

In principle, all this was known before. There is even a term for this - development by analogy or analogous alignment. But these are all exceptions, and exceptions are conditional. At the same time, most verbs, including learn, burn, and so on, get rid of irregular forms - and the authors suggest that such changes be considered random.

On the other hand, can the main direction of development, also determined by many factors, be considered random? In addition to the past tense forms of verbs, the authors consider the development of periphrastic constructions with the auxiliary verb do and the development of negative constructions. It is noteworthy that they do not hide the fact that they come to the same conclusion that was made 100 years ago (!) by the famous Danish linguist Otto Jespersen: the development of a negative construction is due to other changes taking place in the English language, and is not random.

It is noteworthy that they do not hide the fact that they come to the same conclusion that was made 100 years ago (!) by the famous Danish linguist Otto Jespersen: the development of a negative construction is due to other changes taking place in the English language, and is not random.

In other words, there is nothing new in the article that would not be known to traditional linguistics. Perhaps the authors did not need this: they checked whether the methods of population genetics work in linguistics. Probably, they work at the level of the most general observations. But the slightest attempt to clarify the details shows that linguistics and genetics have different objects and different research methods, and they should not be arbitrarily confused.

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Michael Rabiger. Documentary Screen Directing / Part 10: Editing: The Final Step

Once you've done a thorough editing job, you'll have the feeling that you already know everything about the film by heart. The editor loses objectivity and the ability to make decisions. All conceivable mount options seem exactly the same to him, and they all seem too long. Most often, this feeling happens to film editors who themselves conceived the film and fiddled with the footage themselves.

The editor loses objectivity and the ability to make decisions. All conceivable mount options seem exactly the same to him, and they all seem too long. Most often, this feeling happens to film editors who themselves conceived the film and fiddled with the footage themselves.

In this case, it is necessary to draw up a general outline of the film and try to look at what the idea is from the outside, and then show the working version of the film to colleagues.

Diagnosis and general scheme

In order to better understand something, it is very useful to try to give the object of interest to us in a different form. Sociologists, for example, know that the meaning of numbers becomes apparent when they are presented graphically in the form of a diagram or diagram.

We are dealing with the enchanting reality of cinema, when what is happening on the screen captures us to such an extent that it is difficult for us to appreciate the film as a whole. The general scheme of the film just makes it possible to look at your work from the side.

The following montage diagnostic form allows you to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the film.

To use this form, you need:

- Watch the movie, pausing after each episode.

- In the empty cells of the form, enter a brief definition of the content of each episode.

- Episode can reflect:

- factual information,

- characterization or appearance of a new character,

- new situation or new storyline,

- allusion which will be further developed later,

- a special mood or feeling.

You should:

- Next to each cell, write the meaning that this episode has for the film as a whole.

- Add timing (only if needed: useful when you need to shorten something).

- Rate the expressiveness of each episode so that the best of them would receive five stars (although this procedure is not necessary, it can be useful if you have to refuse some material).

What the American director describes, according to our concepts, is precisely the work on a silent version of the film - that is, before recording the announcer, music and noises.

Editing diagnostic form_____________________Page

Film title…………………..

Length…….

_______Editor___________________________Date / /______________

Episode name___________________ Episode value for the movie as a whole

Episode No. 1 Meaning

End min.______sec.________________________Length min. sec.

Episode #2 Meaning

End min. sec.____________________________Length min. sec._________

... What can the chart show? As with the first draft of a movie, you will most likely encounter the following:

- Lack of expressiveness or stretched exposure: the action begins to develop too late (which is absolutely unacceptable in television films).

- Repetitions and redundancy of explanations.

- Lack of necessary information.

- Violations in the display of the sequence of events.

- Unequal artistic authenticity of different episodes (which is expressed in the jerky development of the action).

- Depicting the same thing in different ways, select the best options and remove (or use in some other way) the rest.

- Inconsistency of one or more episodes with the general concept of the film. Be brave and remove them. Sometimes you have to part with the most precious thing.

- The idea of the film becomes clear too quickly, so that the rest of the film is reduced to a simple repetition of what has already been said.

- The tape has several endings (up to three) ...

Each of these diseases has its own remedy. Give it a try and you'll see how much better you get, even if you don't know exactly how you did it.

It is impossible to enumerate all the temptations to which the filmmaker is subjected. After making significant changes, you will encounter new problems. It would be very wise to make another film scheme, this will help to identify new defects.

Over time, much of what you achieve with your circuit will become a habit, and you will notice the shortcomings of your work in the earlier stages of editing. However, even experienced documentarians do not shy away from formal analysis.

However, even experienced documentarians do not shy away from formal analysis.

First View

Using the schema will also bring you the following benefits. Knowing the purpose of every brick in the building of the film, you are now ready to test the tape in a small audience. Your viewers should be 5-6 people whose tastes and opinions you respect. The less these people know about your film's goals and objectives, the better.

Inform them that the film is not yet completed and is in progress. List things that aren't done yet: e.g. music, sound effects, titles. It's good if you suggest some kind of working title for the film: this will help the audience understand your intention.

During the screening of a film, the editor must adjust the volume of the sound. Even seasoned producers get the wrong idea about a film if nothing is heard or if sound recording defects are too obvious. Try to present your film in the best possible way, otherwise you will hear undeservedly harsh criticism.

How to Survive and Benefit from Criticism

After watching, ask your viewers how the film is perceived as a whole. It is better to formulate questions clearly, because otherwise the subject of discussion will be matters that are only indirectly related to your tasks. Establish contact with the audience should be very careful, otherwise the whole idea may be fruitless. On the one hand, you must listen carefully, on the other hand, you must not forget your own opinion about the film as a whole. Say as little as possible and avoid at all costs explain what you wanted to say . Clarifications are inappropriate at this stage, as they prevent viewers from forming their own opinions. After all, only your film will be judged, and comments are not needed here. So try to think only about what your critics have to say.

It takes a lot of courage to sit quietly and write down what is said. Many people suffer greatly when they have to listen to criticism. Get ready to be misunderstood and appreciated.

Get ready to be misunderstood and appreciated.

The following questions (starting with the most general ones) are appropriate to ask:

- What is this movie about?

- What issues does it address?

- Doesn't it seem too long?

- What remains unclear or seems ambiguous?

- Which parts of the film look drawn out?

- Which fragments of the film left you indifferent, which ones seemed well done?

- What do you think of … (character name)?

- What would you do... (situation or problem)?

In essence, you are testing what you yourself wrote in the “meaning of the episode” column on your diagnostic form, and along with it, your concept of the film. If the audience is patient, you will be able to find out their attitude to most of the film fragments. If they start to express displeasure, you will be able to discuss only those aspects of the film that cause you the most doubts.

Record everything that is said about the film, or make a tape recording that you can work on later. Then you will be able to look at the picture through the eyes of, for example, those three of your viewers who did not understand that the boy in question in the film was the son of "that woman." Of course, there are already hidden hints of their relationship in other parts of the film, but now you will try to include shots where he calls her "mother". And that will solve the problem.

Then you will be able to look at the picture through the eyes of, for example, those three of your viewers who did not understand that the boy in question in the film was the son of "that woman." Of course, there are already hidden hints of their relationship in other parts of the film, but now you will try to include shots where he calls her "mother". And that will solve the problem.

An annoyed director often has to listen to critics who talk not about the film, but only about what kind of film they would make themselves (this is exactly what happens in film schools). In this case, try to diplomatically translate the conversation to a topic of interest to you.

The ability to perceive criticism means the ability to perceive different opinions. After a while, you will think about how you deal with such conflicting opinions. Remember that your critics are biased and subjective. Therefore, do not try to take into account everything that has been said - it is worth considering only if several people point out the same flaw. And if there are opposing opinions, then you might be better off not changing anything at all. Don't make changes without thinking them through. Remember that when you ask for critical feedback, people are looking for something they think needs to be changed in order to make a useful contribution to your work. Never and under no circumstances will you be able to please everyone.

And if there are opposing opinions, then you might be better off not changing anything at all. Don't make changes without thinking them through. Remember that when you ask for critical feedback, people are looking for something they think needs to be changed in order to make a useful contribution to your work. Never and under no circumstances will you be able to please everyone.

The most important thing is not to change the plan. You should not review it without good reason. If they are not, you should take into account only those comments that serve to improve your own concept.

For a documentary filmmaker, and indeed for any artist, this is a difficult time. It is very easy to be confused and doubt the essence of your work. Keep listening and resist the temptation to immediately start shredding the tape.

At such moments, the documentarian usually thinks that the result of his efforts is rubbish that no one wants, that he has failed, and that all his efforts are in vain. If you feel this way, I advise you to take control of yourself. Keep in mind that your movie will inevitably not look its best on the first viewing. Viewers are terribly annoyed by discrepancies in sound and image that come across here and there, frames that were mistakenly left uncut, episodes that should be inserted into a different context. All these shortcomings reduce the overall impression in the eyes of a non-professional viewer. Remember that the polishing of details that you are about to have will have a significant impact on the audience's perception of the film.

If you feel this way, I advise you to take control of yourself. Keep in mind that your movie will inevitably not look its best on the first viewing. Viewers are terribly annoyed by discrepancies in sound and image that come across here and there, frames that were mistakenly left uncut, episodes that should be inserted into a different context. All these shortcomings reduce the overall impression in the eyes of a non-professional viewer. Remember that the polishing of details that you are about to have will have a significant impact on the audience's perception of the film.

Sometimes it's better to take your time

Whether you like your film or not, it's good to put it aside for a while and do something else. If you've never experienced this problem before, don't worry, you're in the throes of a creative person right now. Birth is always preceded by a long and painful process. When, after a few days or months, you return to work on the film again, and the problems facing you no longer seem insurmountable.

Taking a few days off from work on editing is an illusory and painful luxury. In 95% of cases, this fails: deadlines are pressing on you, the producer is rushing, etc. Here you have to return to the advice that was given earlier.

Think of solitaire. We recommended starting this "game" before making an intermediate or final cut of the film.

After a disheartening viewing, after all the criticism, lay out your cards with actionable and vivid scene names in sequence on your desk, or better yet, on the floor. Stand above them to your full height and mentally play through them the dramatic course of your own presentation of thoughts, and in parallel - the course of thoughts and changes in the experiences of your future viewers.

At this point, each of the scenes has usually been edited fairly cleanly. And the potential for the best change in drama is hidden only in the rearrangement of scenes. Moreover, these possibilities are so wide that they allow changing the meaning of the entire film even to the opposite.

By this moment, the pictorial series and the conversations of the characters in the picture are so well imprinted in your memory that, rearranging the cards on the floor in a new sequence, you almost instantly discover how the meaning changes from the rearrangement of the scenes. Find the best option and go to the editing room, for which you will again have to pay. It is only necessary to remind you that it is better to do all this before recording the announcer, music and noises.

Try again and again

If a tape requires a lot of editorial work, be prepared to run several test screenings in different audiences. To see where you've improved your feed, you can show the final version of the movie to the same viewers who first saw your movie.

Being a director and having a lot of experience as an editor, I am sure that in fact the film is created in the editing process. At this stage, the footage taken acquires the magical shape of the film. Only a few members of the crew know what is really going on in the editing room. After all, this is the work of alchemists, about which the uninitiated have no idea.

Only a few members of the crew know what is really going on in the editing room. After all, this is the work of alchemists, about which the uninitiated have no idea.

Final cut

The above process ends with the final cut of the film. True, out of caution, it is usually called not final, but simply white, since small changes can still be made to it. Some of them are related to the preparation of sound tracks and music for mixing - sound mixing.

Audio mixing

You can mix all the audio tracks together when you have already:

- completed the content of the tape,

- determined the place of musical accompaniment,

- sorted dialogue tracks to make synchronization easier,

- recorded and determined the location of the narration,

- edited sound effects and atmospheric noise,

- drew up a sound balancing scheme.

A book could be written on this subject, so what follows is a list of just the basic steps you will need to take, along with some instructions to make the process easier. Sound balancing determines the following:

Sound balancing determines the following:

- Establishing correlations in sound strength: for example, between the recording of the voice of one of the characters in the foreground and the background noise of a bus stop in the background.

- Volume Conversion: Reduce or increase the volume of a sound so that new components such as voiceover, music or dialogue can be used without overlap.

- Leveling: filtering and processing of individual audio tracks, either to match other tracks or to provide better audibility and listening comfort. For example, the ear-piercing noise produced by a rumbling vehicle can be softened by cutting off the low frequencies somewhat, leaving the initial range unchanged.

- Sound recording design, introduction of techniques such as echo, "voice on the phone", etc.

- Audio Range Enhancement: Compressor cuts wide dynamic range down to TV broadcast limits, limiter leaves main range unchanged but brings audio peaks down to mid-range.

- Sound Perspective: Leveling and working on the range of the sound contributes to a certain extent to the appearance of sound perspective.

- Creating the effect of a multi-dimensional sound space.

- Stereo channel allocation: To create the effect of spatial distance when working on a stereo track or a track that combines different sounds, different sound components should be placed on different audio paths.

- Noise Reduction: Dolby Noise Reduction and other similar systems help to minimize the hiss that occurs in otherwise unaccompanied movie scenes.

The thoughtful interest with which the audience watches a good film can quickly disappear due to the sharp fluctuations in the level, quality and types of sound design. With the exception of moments that should cause shock, the soundtrack of the film is designed to help switch the attention of the audience to the next object.

The only way this can be done is by staggering audio fragments between two or more tracks. When working on both film and video, you won't be able to mix sound or match a piece of audio from one track to a recording on another track until you've separated the tracks themselves. The reason for this is simple: all frequency conversion changes take time, and they cannot be done in one fell swoop at the junction of two tracks.

When working on both film and video, you won't be able to mix sound or match a piece of audio from one track to a recording on another track until you've separated the tracks themselves. The reason for this is simple: all frequency conversion changes take time, and they cannot be done in one fell swoop at the junction of two tracks.

Preparation

Film soundtracks are easier to process than video soundtracks because you can see how the film track works with your own eyes. Each section of the track is streaked with colored lines, and your job is greatly facilitated by the fact that you see the material that you have to deal with. The fact that you can cut along the frame (1/24 sec.) helps to control the accuracy of your actions. The ordering of the tracks of a video film as a result of computer transfer seems to be more abstract, although the basic working principles that are used remain the same. If the track ordering is done digitally, time indications will appear on your computer screen from left to right, so the track arrangement looks supremely clear and logical.

Here's what to remember when editing:

- Careless cutting: be careful not to cut off the barely audible end of the descending sound or, conversely, the rise of the sound at the very beginning. You can cut only when you turn on the sound at a high volume, so that you hear everything that you cut.

- Unsuccessfully converted sounds: put an annoying sound in the background, so that another sound is in the foreground (for example, give it as a background to a dialogue or a doorbell).

- Audio Skip: You can shorten the looped sound by cutting out one or more loops.

- Unwanted background: if you are recording music or some other sound effect that introduces its own background, trim the section you need just before the sound rises and immediately after it fades, so that the alien background cannot appear.

- Acoustic effect: try to introduce and stop the sound not suddenly, but gradually. Remember that the human ear is much more sensitive to the beginning and end of a sound than to its gradual change.

- Sound synchronization logic: consider whether it is possible to change the strength and perspective of the sound when the perception angle of the character on the screen also changes (for example, when he opens the door to the street).

- Audio overlay: Don't forget to cut out the overlay sections.

Structural organization of sound phonogram

The components of the audio tracks listed below in descending order of their value may change. Music, for example, may be brought to the fore, while the words of dialogue may be barely audible.

Narration: The details of how to synchronize the narration have already been given above. If parts of the text are accompanied by otherwise unvoiced episodes, you will have to somehow fill in the gaps between words so that the soundtrack remains “alive”.

Dialogue tracks and incompatibility problem: Dialogue tracks should be staggered at the editing stage. If you are working with a video system with two tracks, then each subsequent fragment should be placed on a new track. This assumes that you have previously adjusted the various fragments with the help of a mixer, using pauses between pieces of texts. This will allow you to adjust the uneven volume and clarity of individual fragments of the speech of heroes .

If you are working with a video system with two tracks, then each subsequent fragment should be placed on a new track. This assumes that you have previously adjusted the various fragments with the help of a mixer, using pauses between pieces of texts. This will allow you to adjust the uneven volume and clarity of individual fragments of the speech of heroes .

Uneven volume (very quiet and very loud nearby on the track) is a sign of a badly recorded sound. Such a sound makes the viewer pay attention not to the content of the film, but to the accompanying technical flaws. Such defects often appear, for example, in the following situation. The speech of two speakers who are in the same place sounds different due to the fact that during the recording the microphone was at a different distance from each of them. And since the replicas were recorded directly after each other, their sound turned out to be different. By splitting the cues into two tracks, you can amplify the sound of a quieter voice, which will then be better combined with another, louder one . ..

..

Similarly, replicas are mixed together at the stage of preparing a film cut on two films. And if the discrepancies in volume are not very large, then sometimes the operation of equalizing the volume of replicas is carried out on re-recording.

The nature of the sound of voices: Different acoustic properties of the rooms in which the recording was made, different microphones, as well as different distances at which they were installed, violate the principle of identity of the acoustic impression reproduced by the voice. But if you pay due attention to filtering (equalizing) the sound when mixing, then you will significantly reduce the tension and irritation that inevitably appears in a person who must constantly adapt to unmotivated changes in sound quality.

Music: Music is easy to sync, but please note that the music must start immediately after the start of the track, otherwise even voices in the studio or the hiss of the recording device will be heard. The sound of music should stop immediately before the start or during the sound of a new phonogram, as well as before the appearance of a new element on the screen or already in its background. Music should be replaced by something that would allow the attention of the audience to switch.

The sound of music should stop immediately before the start or during the sound of a new phonogram, as well as before the appearance of a new element on the screen or already in its background. Music should be replaced by something that would allow the attention of the audience to switch.

Short Sound Effects: These sounds should correspond exactly to what is happening on the screen when, for example, someone closes a door, puts a coin on the table with a jingle, or when a phone rings. The most general guidelines are as follows:

- Don't expect to be able to use everything in the library in your movie, you first need to see if a particular sound clip is right for you.

- Recordings in the music library, sideroms, etc. often contain sets of various noises. As mentioned above, in order to minimize side effects, the sound fragment that you have taken from the music library should be limited to points immediately before the sound fades in and immediately after it fades out.

- You can shorten the playing time of intermittent sounds (such as footsteps or the sound of a person chopping a tree) by reducing the number of repeated cycles. But the only way to “build up” the missing cycles is with the help of digital computer equipment, which allows you to extend the playing time without lowering the pitch.

- Atmospheric and background noises: The selection of phonograms of such noises is carried out so that:

- Create a certain mood (compare, for example, birds singing against a picture of a morning forest and sounds like sawing wood in a carpenter's workshop).

- Hide the defects of some other soundtrack, in this case using background noise to distract attention.

- Provide audio for the whole image fragment, not just part of it, except when logic requires otherwise...

For Russian professionals, the listed works are usually called "voicing". So we say: speech dubbing, noise dubbing, musical dubbing. If all types of dubbing are completed, then you are on the verge of the next crucial stage. The Russians call it “overwriting”, the British call it “sound mixing”. In essence, this is the process of mixing all the phonograms onto one track.

If all types of dubbing are completed, then you are on the verge of the next crucial stage. The Russians call it “overwriting”, the British call it “sound mixing”. In essence, this is the process of mixing all the phonograms onto one track.

Mixing strategy

Pre-mixing soundtracks. One part of a feature film includes at least 40 soundtracks. And since up to four people can simultaneously use the mixing console during the mixing process, it is better to prepare for work in advance, that is, to conduct preliminary mixing. This applies to more modest documentaries, where there are from 4 to 8 tracks to be mixed, and to the simplest videotapes, on which only 2 tracks can be played at a time.

Remember the golden rule: mix audio tracks in an order that allows you to highlight the most significant elements .

If you are going to re-record both dialogue and sound effects on the same tape, then when you later add sound effects or music, the dialogue must remain in the foreground. And since the most important thing is to ensure that the words of the dialogue are heard, you must watch this all the time.

And since the most important thing is to ensure that the words of the dialogue are heard, you must watch this all the time.

Although dialogue is not always the most significant element, in the simplest situation (for a two-track video system) the downmix order should be:

1. Mix the dialogue using synchronized tracks.

2. Mix dialogue and atmospheric noise.

3. Combine the sound of dialogue with noises and music.

4. Combine the results of the 2nd and 3rd steps so that you have everything on one track.

5. The last step is to combine the narration (if any) and the results of the premix.

In non-digital recording processing, each new sound transfer introduces an additional level of system noise or hiss. Unfortunately, on quiet recordings, such as a slowly speaking voice in a quiet room, or on low-saturated musical recordings, these side sounds are clearly audible. Therefore, when mixing, you should avoid repeated transfers of sound from track to track.

The mixing of several phonograms onto one tape or track in English terminology is called premixing. To facilitate the understanding of technological actions and manipulations with sound, we took the liberty of introducing the term “mixing”, which is used in domestic production practice.

What is the mixing process? Let's say you have several speech tapes, with interviews and voice-overs from the characters. It is better to reduce them to one track before rewriting. To obtain high-quality sound in the final version of the film, each requires specific processing. If the phonograms are processed and cleaned during mixing, then it will be easier for the sound engineer to cope with the processing and mixing of music, noise and speech on one tape during dubbing.

Classical dubbing technology requires the following order:

1. Editing and mixing of interviews and dialogues with simultaneous equalization of the sound and preliminary cleaning of the soundtrack.

2. Additional voice acting if required.

3. Record and mix background noise onto one track.

4. Recording and mixing sound effects.

5. Recording under the image and mixing of all musical phonograms.

6. Mixing all noise and music into one track. This phonogram is included in the set of so-called source materials. If the film is translated into another language, then this soundtrack is usually placed under all the translated texts.

7. Narration and dialogues and lines carrying the main content are mixed separately. If the dialogues serve only as a background, then they are usually placed on a common mixed soundtrack.

8. The last operation is the most important: bringing all sounds and speech onto one track. The result is called the "overwrite original".

M. Rabiger talks about this further.

Rehearse first, then record: You'll get better results if you listen to the piece you're processing first and then mix it down. Thus, by pausing at convenient places, you will move forward, processing fragment by fragment. Just don't be too hasty.

Thus, by pausing at convenient places, you will move forward, processing fragment by fragment. Just don't be too hasty.

This is a step-by-step re-recording that requires preliminary rehearsals. Not always in the process of scoring a film, all the listed information of phonograms is carried out. Therefore, often at the final stage of dubbing, the sound engineer needs to mix not two, but much more tapes or tracks. And when there are more than three of them, it is impossible to do without rehearsals.

Before re-recording, the director and sound engineer must compose the score of all tracks, indicating where, in what place of this or that scene on the sound tracks there are texts, noises and music. The sound score is a kind of project of the entire sound sequence of the film in its diversity.

Finishing the mix: After the end of mixing , listen to the entire recorded audio without stopping.

Synchronization of sound recording and film image: In the film laboratory, the sound recording in its final form is transferred to an optical (photo-) track, and then synchronized with the image. The result is a projection version of the film. Television often broadcasts a "double system": the picture and magnetic sound recording are loaded into separate but connected machines so that the sound is transmitted from a high-quality magnetic original rather than from an average-quality 16mm photographic track.

The result is a projection version of the film. Television often broadcasts a "double system": the picture and magnetic sound recording are loaded into separate but connected machines so that the sound is transmitted from a high-quality magnetic original rather than from an average-quality 16mm photographic track.

Synchronizing audio and video: Provided you have the appropriate tracks on your video system, synchronized audio can be transferred (using the sync start mark) from one tape to another. In practice, this means that when synchronizing the sound recording and the video image, copies of the editing original and the original sound recording are used, and then the original sound recording is again combined with the original image, representing, so to speak, a copy of the second generation. CAUTION: since this procedure erases the original tracks to make way for the mixed recording, in order to make sure that the procedure is correct, you should first try it on copies ...

Keep a backup copy of the original mixed audio. Since mixing is a long painstaking work, when it is finished, professionals always immediately make a backup copy. She is kept in reserve "just in case." Copies are made from the first original of the mixed sound recording.

Since mixing is a long painstaking work, when it is finished, professionals always immediately make a backup copy. She is kept in reserve "just in case." Copies are made from the first original of the mixed sound recording.

Credits and Acknowledgments

Each film has a working title, but the final title is sometimes decided at the last minute. Often the title is not easy to come up with, because it should briefly express what the movie is about. Remember that the movie's "name" is also an advertisement intended for the audience, so it must attract attention. Neither TV programs nor movie posters usually give information about films, so the title is your only identifying mark.

A sure sign of unprofessionalism is a huge list of people to whom gratitude is given. Once I watched a 4-minute film, the credits for which took almost as long as the film itself, which was noted by the stormy applause of the ironic audience. Titles should be laconic, take a little time. The name of the same person performing different functions should not constantly flash on the screen, and gratitude should be expressed in an elegant and concise manner. In this regard, we can boldly follow the models offered by television. The following credits are for a fictional movie as an example:

The name of the same person performing different functions should not constantly flash on the screen, and gratitude should be expressed in an elegant and concise manner. In this regard, we can boldly follow the models offered by television. The following credits are for a fictional movie as an example:

No. Screen text Seconds

——————————————————————————————————-

(name)

1 How do you think to keep them 7

on the farm?

(end credits)

2 Text read - Robin Wragg 4

3 Music - Graham Collier 4

4 Documentary material -

Maggie Hall 13

Cinematography - Tony Cummings

Sound engineer - Rosalyn Mann

Sound editor - Danielle Richlet - Editor 9003

5 Written and directed by Avril Lemoine 5

6 We thank 10

National Endowment for the Arts,

Illinois Council for the Humanities,

Department of Agricultural Research,

Smith University, Illinois,

Mr. and Mrs. Mike Roy,

Joe and Lyn Locker

7 Сoryring Avril Lemoine © (1997) ) 3

———————————————————-

To set the screen time of a page (which is a single on-screen image of the titles), read it aloud and increase the elapsed time by one and a half times. When you shoot titles, increase this time by at least three times more. If necessary, this will not only extend the screen time of titles, but also facilitate computer processing of the material.

When you shoot titles, increase this time by at least three times more. If necessary, this will not only extend the screen time of titles, but also facilitate computer processing of the material.

While working on the film, the people who helped you did not count on any other reward than thanks in the credits, so try to punctually fulfill the promises you made. When you receive funding from somewhere, you must mention it. You must carefully monitor compliance with all such obligations. At least two people with appropriate education should check the spelling, paying special attention to the correct spelling of names.

Using a video system makes it easy to debug the fonts used, but the film reel requires more attention to itself ...

Never leave the compilation of titles to the last moment. It's a tough job, especially if you're ambitious and want to make a good impression. Titles, like misfortunes, are sent to test us, so leave some time in case you have to redo everything.

M. Rabiger is an experienced director, editor and teacher. In his creative biography - dozens of films of various genres. Many directors under his leadership began their journey into art. He is one of those who understands well how difficult the path to the heights of the director's profession is, how many obstacles there are. And therefore, he tries to gently warn his reader about possible miscalculations and mistakes that often happen to beginners. What is called - shows where to lay the straw so that it does not hurt when you fall.

The author of a book on documentary directing knows perfectly well that the profession cannot be mastered after one reading of his textbook and invites the reader to repeat the main lessons of mastery to some extent. In the final paragraphs of the section, he returns to the main thing - dramaturgy and the original principles of screen creativity of a documentary filmmaker in film and television.

In the West, editing is a highly respected and highly paid profession.