Magical beans story

The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk

Old English Fairy Tale - version written and illustrated by Leanne Guenther

Once upon a time, there lived a widow woman and her son, Jack, on their small farm in the country.

Every day, Jack would help his mother with the chores - chopping the wood, weeding the garden and milking the cow. But despite all their hard work, Jack and his mother were very poor with barely enough money to keep themselves fed.

"What shall we do, what shall we do?" said the widow, one spring day. "We don't have enough money to buy seed for the farm this year! We must sell our cow, Old Bess, and with the money buy enough seed to plant a good crop."

"All right, mother," said Jack, "it's market-day today. I'll go into town and sell Bessy."

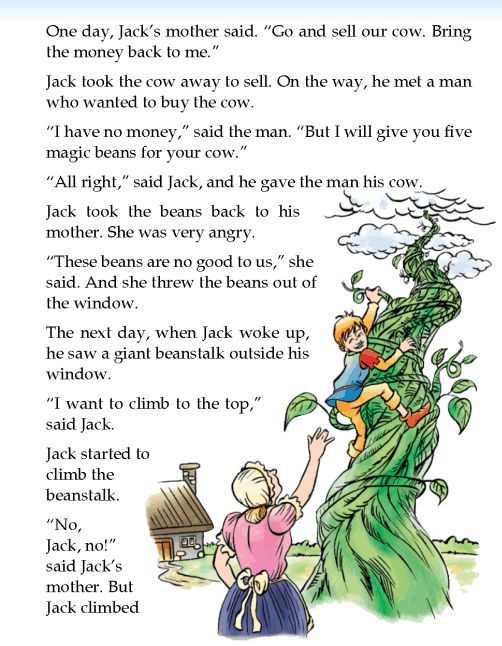

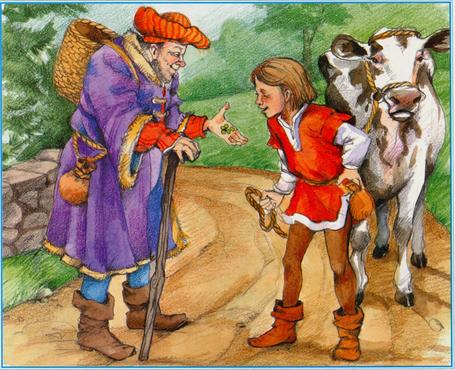

So Jack took the cow's halter in his hand, walked through the garden gate and headed off toward town. He hadn't gone far when he met a funny-looking, old man who said to him, "Good morning,

Jack. "

"Good morning to you," said Jack, wondering how the little, old man knew his name.

"Where are you off to this fine morning?" asked the man.

"I'm going to market to sell our cow, Bessy."

"Well what a helpful son you are!" exclaimed the man, "I have a special deal for such a good boy like you."

The little, old man looked around to make sure no one was watching and then opened his hand to show Jack what he held.

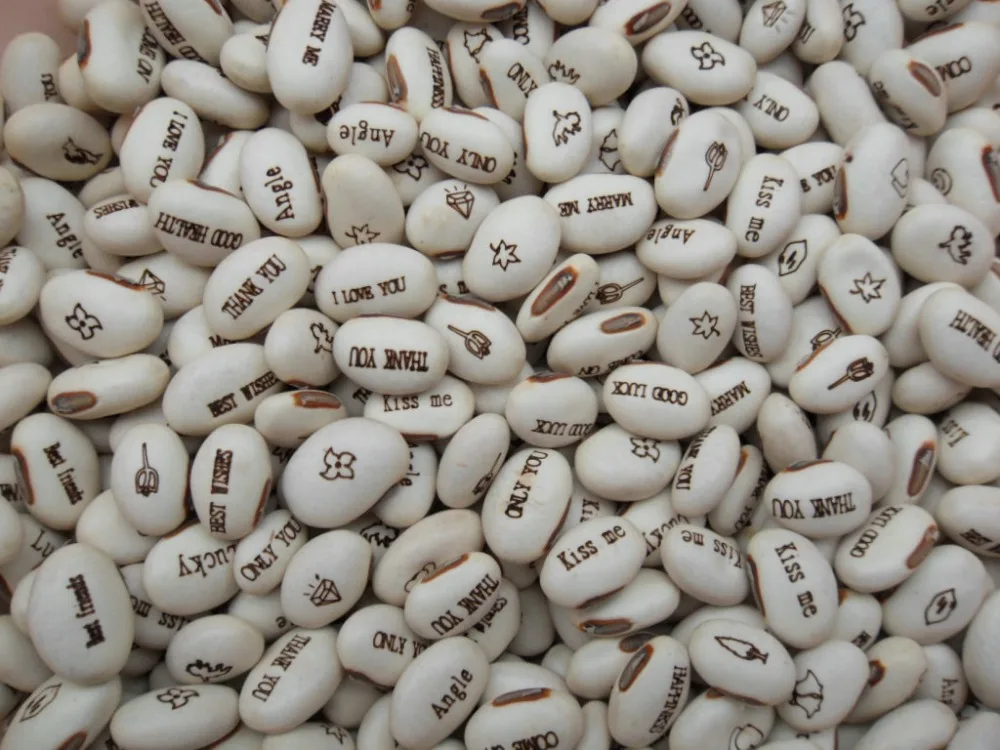

"Beans?" asked Jack, looking a little confused.

"Three magical bean seeds to be exact, young man. One, two, three! So magical are they, that if you plant them over-night, by morning they grow right up to the sky," promised the funny little man. "And because you're such a good boy, they're all yours in trade for that old milking cow."

"Really?" said Jack, "and you're quite sure they're magical?"

"I am indeed! And if it doesn't turn out to be true you can have your cow back. "

"

"Well that sounds fair," said Jack, as he handed over Bessy's halter, pocketed the beans and headed back home to show his mother.

"Back already, Jack?" asked his mother; "I see you haven't got Old Bess -- you've sold her so quickly. How much did you get for her?"

Jack smiled and reached into his pocket, "Just look at these beans, mother; they're magical, plant them over-night and----"

"What!" cried Jack's mother. "Oh, silly boy! How could you give away our milking cow for three measly beans." And with that she did the worst thing Jack had ever seen her do - she burst into tears.

Jack ran upstairs to his little room in the attic, so sorry he was, and threw the beans angrily out the window thinking, "How could I have been so foolish - I've broken my mother's heart." After much tossing and turning, at last Jack dropped off to sleep.

When Jack woke up the next morning, his room looked strange. The sun was shining into part of it like it normally did, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. So Jack jumped up and

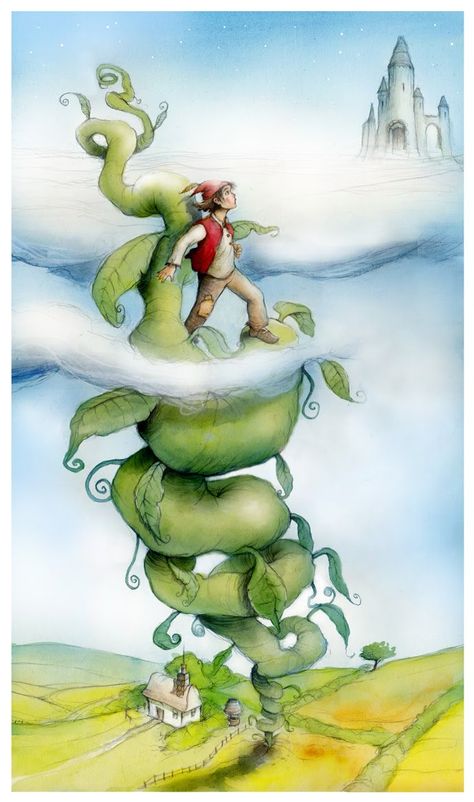

dressed himself and went to the window. And what do you think he saw? Why, the beans he had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a big beanstalk which went up and up and

up until it reached the sky.

The sun was shining into part of it like it normally did, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. So Jack jumped up and

dressed himself and went to the window. And what do you think he saw? Why, the beans he had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a big beanstalk which went up and up and

up until it reached the sky.

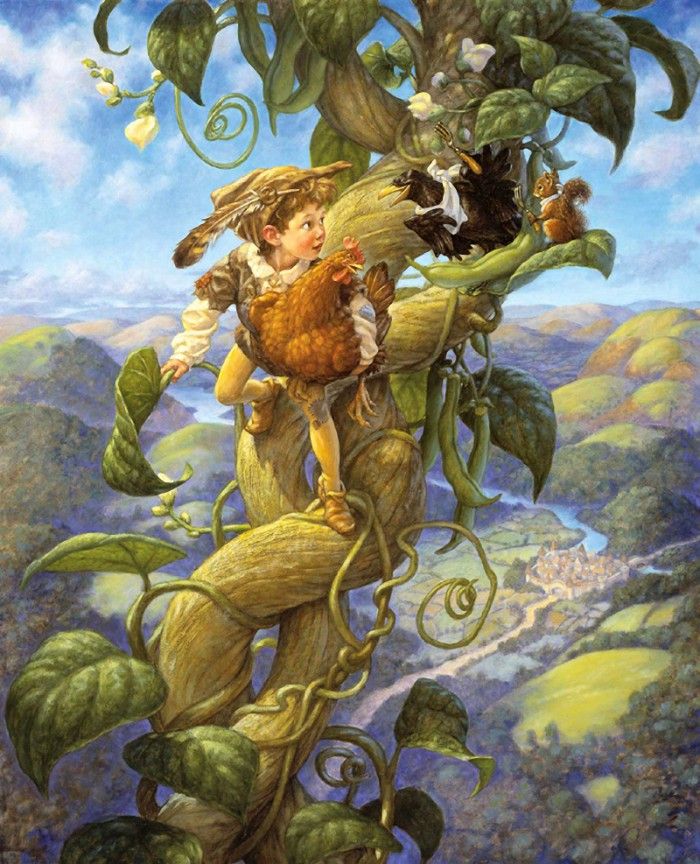

Using the leaves and twisty vines like the rungs of a ladder, Jack climbed and climbed until at last, he reached the sky. And when he got there he found a long, broad road winding its way through the clouds to a tall, square castle off in the distance.

Jack ran up the road toward the castle and just as he reached it, the door swung open to reveal a horrible lady giant, with one great eye in the middle of her forehead.

As soon as Jack saw her he turned to run away, but she caught him, and dragged him into the castle.

"Don't be in such a hurry, I'm sure a growing boy like you would like a nice, big breakfast," said the great, big, tall woman, "It's been so long since I got to make breakfast for a boy. "

"

Well, the lady giant wasn't such a bad sort, after all -- even if she was a bit odd. She took Jack into the kitchen, and gave him a chunk of cheese and a glass of milk. But Jack had only taken a few bites when thump! thump! thump! the whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

"Goodness gracious me! It's my husband," said the giant woman, wringing her hands, "what on earth shall I do? There's nothing he likes better than boys broiled on toast and I haven't any bread left. Oh dear, I never should have let you stay for breakfast. Here, come quick and jump in here." And she hurried Jack into a large copper pot sitting beside the stove just as her husband, the giant, came in.

He ducked inside the kitchen and said, "I'm ready for my breakfast -- I'm so hungry I could eat three cows. Ah, what's this I smell?

Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead

I'll have his bones to grind my bread.

"Nonsense, dear," said his wife, "we haven't had a boy for breakfast in years. Now you go and wash up and by the time you come back your breakfast'll be ready for you."

So the giant went off to tidy up -- Jack was about to make a run for it when the woman stopped him. "Wait until he's asleep," she said, "he always has a little snooze after breakfast."

Jack peeked out of the copper pot just as the giant returned to the kitchen carrying a basket filled with golden eggs and a sickly-looking, white hen. The giant poked the hen and growled, "Lay" and the hen laid an egg made of gold which the giant added to the basket.

After his breakfast, the giant went to the closet and pulled out a golden harp with the face of a sad, young girl. The giant poked the harp and growled, "Play" and the harp began to play

a gentle tune while her lovely face sang a lullaby. Then the giant began to nod his head and to snore until the house shook.

When he was quite sure the giant was asleep, Jack crept out of the copper pot and began to tiptoe out of the kitchen. Just as he was about to leave, he heard the sound of the harp-girl weeping. Jack bit his lip, sighed and returned to the kitchen. He grabbed the sickly hen and the singing harp, and began to tiptoe back out. But this time the hen gave a cackle which woke the giant, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, "Wife, wife, what have you done with my white hen and my golden harp?"

Jack ran as fast as he could and the giant, realizing he had been tricked, came rushing after - away from the castle and down the broad, winding road. When he got to the beanstalk the giant was only twenty yards away when suddenly he saw Jack disappear - confused, the giant peered through the clouds and saw Jack underneath climbing down for dear life. The giant stomped his foot and roared angrily.

Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead

I'll have his bones to grind my bread.

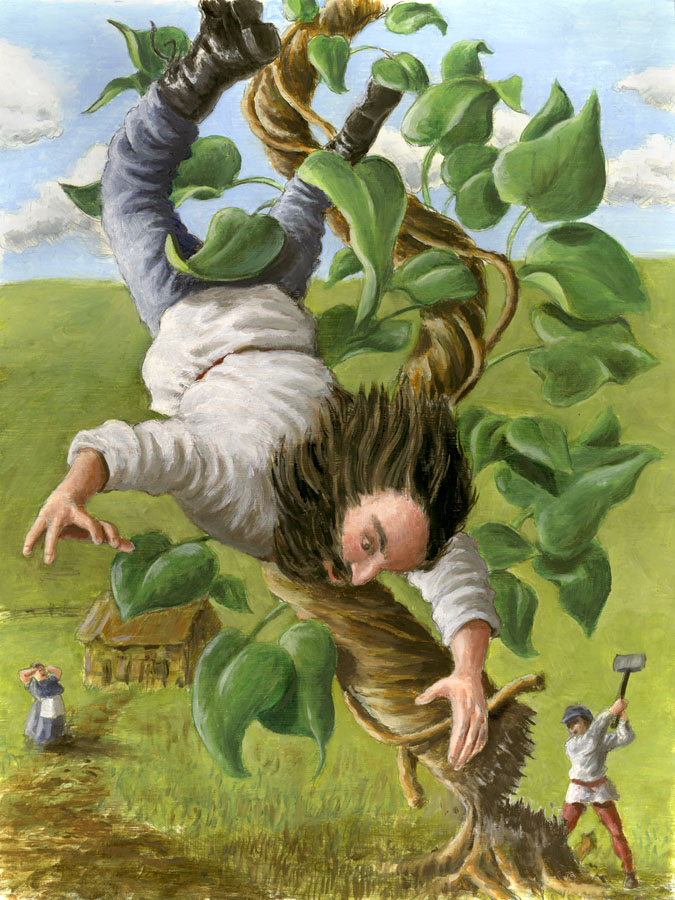

The giant swung himself down onto the beanstalk which shook with his weight. Jack slipped, slid and climbed down the beanstalk as quickly as he could, and after him climbed the giant.

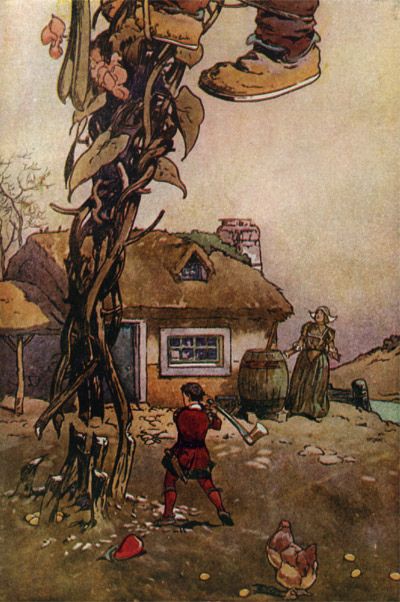

As he neared the bottom, Jack called out, "Mother! Please! Hurry, bring me an axe, bring me an axe." And his mother came rushing out with Jack's wood chopping axe in her hand, but when she came to the enormous beanstalk she stood stock still with fright.

Jack jumped down, got hold of the axe and began to chop away at the beanstalk. Luckily, because of all the chores he'd done over the years, he'd become quite good at chopping and it didn't

take long for him to chop through enough of the beanstalk that it began to teeter. The giant felt the beanstalk shake and quiver so he stopped to see what was the matter. Then Jack gave one

last big chop with the axe, and the beanstalk began to topple over. Then the giant fell down and broke his crown, and the beanstalk came toppling after.

The singing harp thanked Jack for rescuing her from the giant - she had hated being locked up in the closet all day and night and wanted nothing more than to sit in the farmhouse window and sing to the birds and the butterflies in the sunshine.

With a bit of patience and his mother's help, it didn't take long for Jack to get the sickly hen back in good health and the grateful hen continued to lay a fresh golden egg every day.

Jack used the money from selling the golden eggs to buy back Old Bess, purchase seed for the spring crop and to fix up his mother's farm. He even had enough left over to invite every one of his neighbours over for a nice meal, complete with music from the singing harp.

And so Jack, his mother, Old Bess, the golden harp and the white hen lived happy ever after.

Printable version of this story

Templates:

- Close the template window after printing to return to this screen.

- Set page margins to zero if you have trouble fitting the template on one page (FILE, PAGE SETUP or FILE, PRINTER SETUP in most browsers).

Template Page 1 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 2 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 3 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 4 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 5 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 6 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 7 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 8 (color) or (B&W)

Template Page 9 (color) or (B&W)

Jack and the Beanstalk - Storynory

seek 00.00.00 00.00.00 loading- Download

Download the audio

Pictures by Sophie Green

There was once upon a time a poor widow who had an only son named Jack, and a cow named Milky-White. All they had to live on was the milk the cow gave every morning, which they carried to the market and sold - until one morning Milky-White gave no milk.

All they had to live on was the milk the cow gave every morning, which they carried to the market and sold - until one morning Milky-White gave no milk.

“What shall we do, what shall we do?” said the widow, wringing her hands.

“Cheer up mother, I’ll go and get work somewhere,” said Jack.

“We’ve tried that before, and nobody would take you,” said his mother. “We must sell Milky-White and with the money, start a shop or something.”

“Alright, mother,” said Jack. “It’s market day today, and I’ll soon sell Milky-White, and then we’ll see what we can do.”

So he took the cow, and off he started. He hadn’t gone far when he met a funny looking old man, who said to him, “Good morning, Jack.”

“Good morning to you,” said Jack, and wondered how he knew his name.

“Well Jack, where are you off to?” Said the man.

“I’m going to market to sell our cow there.”

“Oh, you look the proper sort of chap to sell cows,” said the man. “I wonder if you know how many beans make five. ”

”

“Two in each hand and one in your mouth,” said Jack, as sharp as a needle.

“Right you are,” says the man, “and here they are, the very beans themselves,” he went on, pulling out of his pocket a number of strange looking beans. “As you are so sharp,” said he, “I don’t mind doing a swap with you — your cow for these beans.”

“Go along,” said Jack. “You take me for a fool!”

“Ah! You don’t know what these beans are,” said the man. “If you plant them overnight, by morning they grow right up to the sky.”

“Really?” said Jack. “You don’t say so.”

“Yes, that is so. If it doesn’t turn out to be true you can have your cow back.”

“Right,” said Jack, and handed him over Milky-White, then pocketed the beans.

Back home goes Jack and says to his mother, “You’ll never guess mother what I got for Milky-White.”

His mother became very excited, “Five pounds? Ten? Fifteen? No, it can’t be twenty.”

“I told you that you couldn’t guess. What do you say to these beans? They’re magical. Plant them overnight and — ”

Plant them overnight and — ”

“What!” Exclaimed Jack’s mother. “Have you been such a fool, such a dolt, such an idiot? Take that! Take that! Take that! As for your precious beans, here they go out of the window. Now off with you to bed. Not a sup shall you drink, and not a bit shall you swallow this very night.”

So Jack went upstairs to his little room in the attic, sad and sorry he was, to be sure. At last he dropped off to sleep.

When he woke up, the room looked so funny. The sun was shining into part of it, and yet all the rest was quite dark and shady. Jack jumped up and went to the window. What do you think he saw? Why, the beans his mother had thrown out of the window into the garden had sprung up into a giant beanstalk which went up and up and up until it reached the sky. So the man spoke truth after all!

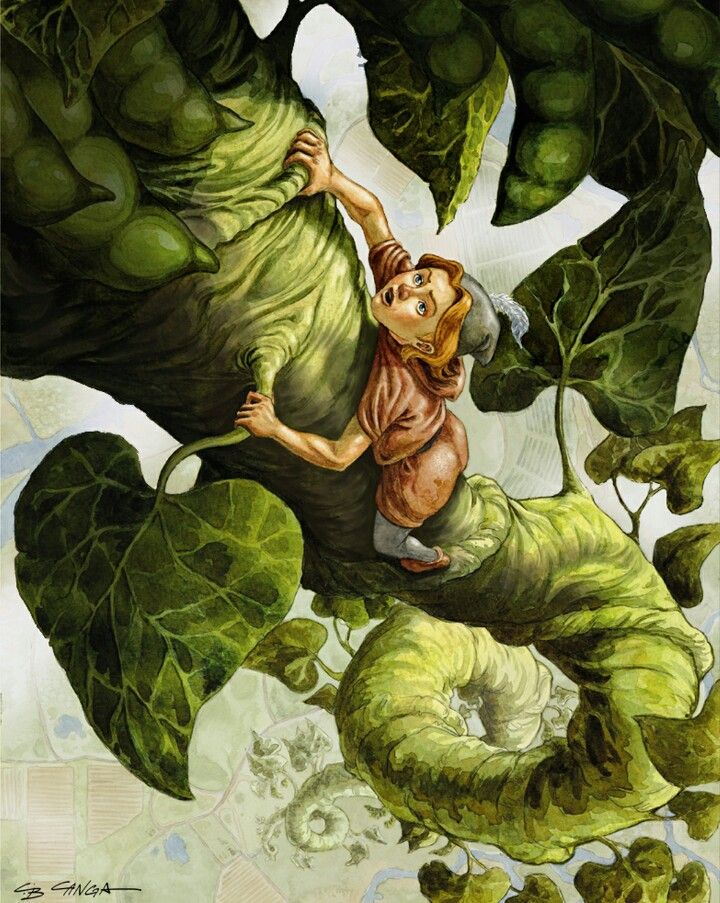

The beanstalk grew up quite close past Jack’s window, so all he had to do was to open it and give a jump onto the beanstalk which ran up just like a big ladder. So Jack climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he reached the sky. When he got there he found a long broad road going as straight as a dart. So he walked along, and walked along, and he walked along until he came to a great big tall house, and on the doorstep there was a great big tall woman.

So Jack climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he reached the sky. When he got there he found a long broad road going as straight as a dart. So he walked along, and walked along, and he walked along until he came to a great big tall house, and on the doorstep there was a great big tall woman.

“Good morning, ma’am,” said Jack, quite politely. “Could you be so kind as to give me some breakfast?” For he was as hungry as a hunter.

“It’s breakfast you want, is it?” said the great big tall woman. “It’s breakfast you’ll be if you don’t move off from here. My man is an ogre and there’s nothing he likes better than boys boiled on toast. You’d better be moving on or he’ll be coming.”

“Oh! please mum, do give me something to eat, mum. I’ve had nothing to eat since yesterday morning, really and truly, mum,” said Jack. “I may as well be boiled as die of hunger.”

Well, the ogre’s wife was not half so bad after all, so she took Jack into the kitchen, and gave him a hunk of bread and cheese and a jug of milk. Jack hadn’t half finished these when thump, thump, thump! The whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

Jack hadn’t half finished these when thump, thump, thump! The whole house began to tremble with the noise of someone coming.

“Goodness gracious me! It’s my old man,” said the ogre’s wife. “What on earth shall I do? Come along quick and jump in here.” She bundled Jack into the oven just as the ogre came in. He was a big one, to be sure. At his belt he had three calves strung up by the heels, and he unhooked them and threw them down onto the table and said:

"Fee-fi-fo-fum,

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I’ll have his bones to grind my bread."

“Nonsense, dear,” said his wife. “You’re dreaming. Or perhaps you smell the scraps of that little boy you liked so much for yesterday’s dinner. Here you go, and have a wash and tidy up. By the time you come back your breakfast’ll be ready for you.”

So off the ogre went, and Jack was just going to jump out of the oven and run away when the woman told him, “Wait till he’s asleep. He always has a doze after breakfast. ” Well, the ogre had his breakfast, and after that he went to a big chest and took out a couple of bags of gold, and down he sat and counted until at last his head began to nod and he began to snore until the whole house shook again.

” Well, the ogre had his breakfast, and after that he went to a big chest and took out a couple of bags of gold, and down he sat and counted until at last his head began to nod and he began to snore until the whole house shook again.

Jack then crept out on tip-toe from the oven, and as he was passing the ogre, he took one of the bags of gold from under his arm, and off he peltered until he came to the beanstalk, and then he threw down the bag of gold, which of course fell into his mother’s garden. He climbed down and down until at last he got home and told his mother and showed her the gold and said, “Well, mother, wasn’t I right about the beans? They are really magical, you see.”

So they lived on the bag of gold for some time, until at last they came to the end of it, and Jack made up his mind to try his luck once more at the top of the beanstalk. So one fine morning he rose up early, and got onto the beanstalk, and he climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until at last he came out onto the road again and up to the great tall house he had been to before. There, sure enough, was the great tall woman a-standing on the doorstep.

There, sure enough, was the great tall woman a-standing on the doorstep.

“Good morning, mum,” said Jack, as bold as brass, “could you be so good as to give me something to eat?”

“Go away, my boy,” said the big tall woman, “or else my man will eat you up for breakfast. Aren’t you the youngster who came here once before? Do you know, that very day my man missed one of his bags of gold.”

“That’s strange, mum,” said Jack, “I dare say I could tell you something about that, but I’m so hungry I can’t speak until I’ve had something to eat.”

Well, the big tall woman was so curious that she took him in and gave him something to eat. He had scarcely begun munching it as slowly as he could when thump! thump! They heard the giant’s footstep, and his wife hid Jack away in the oven.

All happened as it did before. In came the ogre as he did before, said, “Fee-fi-fo-fum,” and had his breakfast off three boiled oxen.

Then he said, “Wife, the hen that lays the golden eggs. ” So she brought it, and the ogre said, “Lay,” and it laid an egg all of gold. Then the ogre began to nod his head, and to snore until the house shook. Jack crept out of the oven on tip-toe and caught hold of the golden hen, and was off before you could say “Jack Robinson.” This time the hen gave a cackle which woke the ogre, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, “Wife, wife, what have you done with my golden hen?”

” So she brought it, and the ogre said, “Lay,” and it laid an egg all of gold. Then the ogre began to nod his head, and to snore until the house shook. Jack crept out of the oven on tip-toe and caught hold of the golden hen, and was off before you could say “Jack Robinson.” This time the hen gave a cackle which woke the ogre, and just as Jack got out of the house he heard him calling, “Wife, wife, what have you done with my golden hen?”

The wife said, “Why, my dear?” But that was all Jack heard, for he rushed off to the beanstalk and climbed down like a house on fire. When he got home he showed his mother the wonderful hen, and said “Lay” to it; and it laid a golden egg every time he said “Lay.”

Well it wasn’t long before that Jack made up his mind to have another try at his luck up there at the top of the beanstalk. One fine morning he rose up early and got to the beanstalk, and climbed, and climbed, and climbed, and he climbed until he got to the top.

This time he knew better than to go straight to the ogre’s house. When he got near it, he waited behind a bush until he saw the ogre’s wife come out with a pail to get some water, and then he crept into the house and got into a big copper pot. He hadn’t been there long when he heard thump, thump, thump! As before, and in came the ogre and his wife.

When he got near it, he waited behind a bush until he saw the ogre’s wife come out with a pail to get some water, and then he crept into the house and got into a big copper pot. He hadn’t been there long when he heard thump, thump, thump! As before, and in came the ogre and his wife.

“Fee-fi-fo-fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman,” cried out the ogre. “I smell him, wife, I smell him.”

“Do you, my dearie?” said the ogre’s wife. “Then, if it’s that little rogue that stole your gold and the hen that laid the golden eggs he’s sure to have gotten into the oven.” And they both rushed to the oven.

Jack wasn’t there, luckily. So the ogre sat down to the breakfast and ate it, but every now and then he would mutter, “Well, I could have sworn –” and he’d get up and search the larder and the cupboards and everything, only, luckily, he didn’t think of the copper pot.

After breakfast was over, the ogre called out, “Wife, wife, bring me my golden harp.” So she brought it and put it on the table before him. Then he said, “Sing!” The golden harp sang most beautifully. It went on singing until the ogre fell asleep, and commenced to snore like thunder.

Then he said, “Sing!” The golden harp sang most beautifully. It went on singing until the ogre fell asleep, and commenced to snore like thunder.

Then Jack lifted up the copper lid very quietly and got down like a mouse and crept on hands and knees until he came to the table, when up he crawled, caught hold of the golden harp and dashed with it towards the door. But the harp called out quite loudly, “Master! Master!” The ogre woke up just in time to see Jack running off with his harp.

Jack ran as fast as he could, and the ogre came rushing after, and would soon have caught him, only Jack had a start and dodged him a bit and knew where he was going. When he got to the beanstalk the ogre was not more than twenty yards away when suddenly he saw Jack disappear. When he came to the end of the road he saw Jack underneath climbing down for dear life. Well, the ogre didn’t like trusting himself to such a ladder, and he stood and waited, so Jack got another start.

Just then the harp cried out, “Master! Master!” and the ogre swung himself down onto the beanstalk, which shook with his weight. Down climbed Jack, and after him climbed the ogre. By this time Jack had climbed down, and climbed down, and climbed down until he was very nearly home. So he called out, “Mother! Mother! Bring me an axe, bring me an axe!” His mother came rushing out with the axe in her hand, but when she came to the beanstalk she stood stuck still with fright, for there she saw the ogre with his legs just through the clouds.

Down climbed Jack, and after him climbed the ogre. By this time Jack had climbed down, and climbed down, and climbed down until he was very nearly home. So he called out, “Mother! Mother! Bring me an axe, bring me an axe!” His mother came rushing out with the axe in her hand, but when she came to the beanstalk she stood stuck still with fright, for there she saw the ogre with his legs just through the clouds.

Jack jumped down and took hold of the axe and gave a chop at the beanstalk which cut it half in two. The ogre felt the beanstalk shake and quiver, so he stopped to see what was the matter. Then Jack gave another chop with the axe, and the beanstalk was cut in two and began to topple over. Then the ogre fell down and broke his crown, and the beanstalk came toppling after.

Jack showed his mother his golden harp, and with showing that and selling the golden eggs, Jack and his mother became very rich, and he married a great princess, and they lived happy ever after.

Magic Beans | Big sport

The modern bob has nothing to do with the sledges connected by a "train" on which the first bobsledders descended. Today it is a high-tech device made of steel and fiberglass, the creation of which the best engineering minds are working on.

Today it is a high-tech device made of steel and fiberglass, the creation of which the best engineering minds are working on.

The modern bob bear has nothing to do with the train-bound sledges used by the first bobsledders. Today it is a high-tech device made of steel and fiberglass, the creation of which the best engineering minds are working on. The aerodynamic properties of fireballs capable of reaching speeds of up to 130 and even 201 km / h (this is the world record today) are tested on the same stands as jet aircraft. The constant improvement of absolutely all the details forces the organizers of the competition to regularly update the specifications prescribed in the regulations in order to keep technical progress under control and not allow technology to come out on top, pushing people aside.

At the end of the 20th century, bobsleigh took over the minds of people all over the world. Someone will consider such a statement controversial, but to be convinced of its truth, it is enough to recall the beautiful story about the Jamaicans, who, against all odds, slid down the icy track of the Olympic Games in Calgary in 1988. About the athletes who literally took the famous Russian proverb “Prepare the sled in the summer ...”, in 1993 the film “Steep Turns” was even shot in Hollywood, clearly demonstrating how these “hothouse” athletes gave the bobsleigh a beautiful story about the impotence of common sense before the attraction of opposites .

About the athletes who literally took the famous Russian proverb “Prepare the sled in the summer ...”, in 1993 the film “Steep Turns” was even shot in Hollywood, clearly demonstrating how these “hothouse” athletes gave the bobsleigh a beautiful story about the impotence of common sense before the attraction of opposites .

“Perhaps it is more interesting than Formula 1, because it depends much more on the person” - Michael Schumacher gave such a description of the bean. The great rider was also surprised by how similar G-forces and general sensations bobsleighs are to race cars. So, the ancient Egyptians were not averse to riding the mummy of the pharaoh on a sleigh under the scorching sun, which, by the way, were quite capable of competing with wheeled carts. And in the peat bogs of Finland and the Northern Urals, narrow long sledges with a flat wooden flooring were found, which, according to scientists, were born more than four thousand years ago. A variation of this vehicle was called the toboggan by the Indians of Canada. Consisting of narrow boards three or four meters long, held together by several crossbars and buckskin straps, Indian toboggans may well be called the ancestors of the modern Olympic bean.

Consisting of narrow boards three or four meters long, held together by several crossbars and buckskin straps, Indian toboggans may well be called the ancestors of the modern Olympic bean.

Thunderstorm for pedestrians

As you know, the first competitions in downhill sledding were held at the very end of the 19th century in the vicinity of St. Moritz, Switzerland. Over a hundred years ago, the most sought-after sleigh was the long wood-and-steel bobs. They were controlled by slings tied to the front skids and accommodated a team of four, five and even six people. And the Norwegian enthusiast Martin Gabrielson, who lived in Canada, built an eleven-seat bob (driver and ten passengers) in 1906 and famously drove off Mount Gaspero on it.

Christoph Langen won 1 MORE Olympic medal than Andre Lange

But later interest in such "communal skids" faded, and in 1908 the first national bobsleigh competition in Austria was dominated by teams of four and five participants. Soon Germany joined Switzerland and Canada, where in 1910 the championship in collective descent on a sled took place. In the next thirteen years, similar competitions were held in countries such as France, Italy, Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia. But despite the wide geography of distribution, bobsleigh remained a semi-professional and amateur sport until 1923 years old. It was then that the International Bobsleigh and Tobogganing Federation (Fe´de´ration Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing, FIBT) appeared, which united bobsledders around the world.

Soon Germany joined Switzerland and Canada, where in 1910 the championship in collective descent on a sled took place. In the next thirteen years, similar competitions were held in countries such as France, Italy, Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia. But despite the wide geography of distribution, bobsleigh remained a semi-professional and amateur sport until 1923 years old. It was then that the International Bobsleigh and Tobogganing Federation (Fe´de´ration Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing, FIBT) appeared, which united bobsledders around the world.

Fiberglass nose

After the bobsleigh received organized support, it was easily included in the first Winter Olympics, held in 1924 in Chamonix, France. Only male crews participated in the competition, because due to the high level of injuries, not a single young lady showed a desire to become the first Olympic bobsledder. Teams of four competed in Chamonix, and the gold was taken away by the Swiss, led by pilot Eduard Scherrer. At the Olympics 1932 years in Lake Placid, the program included a doubles descent, in which the team from the USA won. The Americans repeated their success at the next Winter Olympics in 1936, the last before the Second World War, winning in the descent on double bobs.

At the Olympics 1932 years in Lake Placid, the program included a doubles descent, in which the team from the USA won. The Americans repeated their success at the next Winter Olympics in 1936, the last before the Second World War, winning in the descent on double bobs.

In 1928, there were 3 more Olympic medalists in bobsleigh than in 1924.

By the end of the 1930s, bobsledders' equipment was an open steel sled driven by a rudder. But twelve years later, their exterior has changed a lot. At 1948 in St. Moritz, the athletes amazed the fans with the closed nose of their units, which was made from fiberglass, invented in 1938. Thanks to this, it was possible to improve the aerodynamic characteristics of the sled. Professionals still prefer this particular bean design today.

The era of skinny

Over the next decade, bobsleigh actively cultivated personnel, poaching athletes from other sports. Since it was at this time that the importance of the run before the descent became clear, preference was given to large athletes, whose weight also contributed to better acceleration on the track. The reign of the heavyweights ended at 1952nd, after the FIBT limited the weight of doubles to 165 kilograms and quads to 230 kilograms, including all equipment.

The reign of the heavyweights ended at 1952nd, after the FIBT limited the weight of doubles to 165 kilograms and quads to 230 kilograms, including all equipment.

In bobsleigh competitions, the average run lasts approximately 60 seconds. During this time, the speed of the bean can reach 140 km / h. At the world championships, the score goes to hundredths of a second. So, at the Olympics in Lillehammer between the two Swiss deuces, who claimed for the gold medal, such a stubborn struggle unfolded that after four races they were separated by only five hundredths of a second, which ultimately decided the fate of the first place

The bobsleigh, delivered in a rigid weight and size framework, has become a high-tech sport. To reduce weight, the modern bob is made from expensive materials using technologies used in the Formula 1 racing series. These sleds accelerate to 140 km/h in 60 seconds. In this case, bobsledders experience the effect of gravity four to five times more than usual. Driving such a car requires good reaction, endurance and the ability to work in a team, where each crew member has his own role. At the start, all athletes accelerate the bob, then the pilot directly controls the sled, the crew balances it on turns, and the fourth team member slows down the projectile after the finish. These days, you can see only two- and four-man beans at competitions, the cost of which goes off scale for 50 thousand dollars, which gives every right to call this sport a very expensive pleasure.

Driving such a car requires good reaction, endurance and the ability to work in a team, where each crew member has his own role. At the start, all athletes accelerate the bob, then the pilot directly controls the sled, the crew balances it on turns, and the fourth team member slows down the projectile after the finish. These days, you can see only two- and four-man beans at competitions, the cost of which goes off scale for 50 thousand dollars, which gives every right to call this sport a very expensive pleasure.

The War of Technology

The success of the US team in the 2002 Olympics illustrates the impact of modern technology on bobsleigh performance. Previously, the situation in North America was deplorable: the national team won the last gold medal only in 1956. Thirty-six years without gold made NASCAR racing king Jeffrey Bodine notice at the 1992 Olympics that Americans were riding imported beans. Deciding that a good racing car for his compatriots could only be made in the United States, he established the Bo-Dyn Bobsled Project, which by 1994 developed the first North American bean using technology from Dayton. It took Bodine almost ten years and several million dollars to create a competitive product, but at the Olympics in Salt Lake City, the US team, equipped with Bo-Dyn Bobsled, won three gold medals at once.

It took Bodine almost ten years and several million dollars to create a competitive product, but at the Olympics in Salt Lake City, the US team, equipped with Bo-Dyn Bobsled, won three gold medals at once.

However, already at the Turin Olympics, the performance of the Americans was not as brilliant. Experts explain this by the fact that in one Olympic cycle, the bean has time to become obsolete and requires constant updating - no less than Formula 1 cars. That is why it is almost impossible to name the main favorite of the upcoming Games in Vancouver today. And this means that on the Canadian tracks we can expect any kind of technological surprises.

From Singers to Wimmer

Until recently, Russian bobsledders competed on Zinger equipment, but in 2007 it was decided to change the supplier of two-bobs. The choice fell on the German company Wimmer Carbontechnik, which produces parts for racing cars, including Formula 1 cars. Franz Wimmer's parts are not made by hand, but on high-precision machines, which eliminates all errors. The first tests of the double bob, created specifically for the Russians by the German mechanic Thomas Platzer together with Wimmer Carbontechnik, took place in December last year. Now it remains to win a championship medal on it.

The first tests of the double bob, created specifically for the Russians by the German mechanic Thomas Platzer together with Wimmer Carbontechnik, took place in December last year. Now it remains to win a championship medal on it.

Jack and the Magic Bean - frwiki.wiki

For the articles of the same name, see Jack and the Magic Bean (disambiguation).

Jack and the Beanstalk is a fairy tale popular in English.

It bears some resemblance to Jack the Giant Slayer , another Cornish hero tale. The origin of Jack and Beanstalk is unknown. We can see in the parody version which appeared in the first half of XVIII - th century the first literary version of the story. In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published in London a moralizing version closer to what is known today. The story was subsequently popularized by Henry Cole in The Home Treasury (1842) and Joseph Jacobs gave another version in English Tales (1890). The latter is the version most often reproduced in English-language collections today, and due to its lack of morality and "dry" literary treatment, it is often considered a truer oral version than Tabart's. However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

The latter is the version most often reproduced in English-language collections today, and due to its lack of morality and "dry" literary treatment, it is often considered a truer oral version than Tabart's. However, there can be no certainty in this matter.

Jack and the Beanstalk is one of the most famous folk tales and has been the subject of many adaptations in various forms until today.

Summary

- 1 First printed versions

- 2 Summary (Jacobs version)

- 3 variants

- 4 Structure

- 5 Classification

- 6 Fee-fi-fo-fum formula

- 7 parallels in other fairy tales

- 8 Patterns and ancient origins of these

- 9 Morality

- 10 interpretations

- 11 Illustrations

- 12 Modern adaptations

- 12.1 Cinema

- 12.2 Television and video

- 12.3 Video games

- 12.4 Exhibitions

- 13 Notes and references

- 14 Bibliography

- 14.

1 Versions / editions of fairy tale

1 Versions / editions of fairy tale - 14.2 Research

- 14.3 Symbolic

- 14.4 About adaptation

- 14.

- 15 See also

- 15.1 Related Articles

First printed versions

The origin of this tale is not exactly known, but it is believed to have British roots.

According to Iona and Peter Opie, the first literary version of the tale is The Charm Shown in the Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean , which appears in the 1734 English edition of Round of Our Charcoal Fire or Christmas Amusement , a collection that includes the First Edition, which did not include the tale, is dated 1730. Then this is a parody version that makes fun of the fairy tale, but nevertheless testifies on the part of the author of a good knowledge of the traditional fairy tale.

Frontispiece (" Jack running away from the giant ") and title page "The story of Jack and the beanstalk" , B. Tabart, London, 1807.

Tabart, London, 1807.

when two books were published: "The Story of Mother Twaddle" and "The Wonderful Achievements of Her Son Jack" with the single initials " Bat " as the author's name. and Jack and Bob's Story , published in London by Benjamin Tabart. In the first case, this is a poetic version, which differs significantly from the known version: a servant takes Jack to the giant's house, and she gives the latter beer to put him to sleep; as soon as the giant falls asleep, Jack decapitates him; He then marries a maid and sends for his mother. Another version, whose title page states that it is a version "printed from an original manuscript, never before published", is closer to the tale as we know it today, except that it has a fairy character, which gives the moral of the story.

In 1890, Joseph Jacobs reported in English Tales a version of Jack and the Beanstalk which he said was based on "oral versions heard in his boyhood in Australia about 1860" and in which he took the side of "ignoring excuse". given by Tabart for Jack who killed the giant. Subsequently, other versions of the tale will follow sometimes Tabart, who therefore justifies the hero's actions, sometimes Jacobs, who presents Jack as a steadfast deceiver. So Andrew Lang at The Red Fairy Book , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

given by Tabart for Jack who killed the giant. Subsequently, other versions of the tale will follow sometimes Tabart, who therefore justifies the hero's actions, sometimes Jacobs, who presents Jack as a steadfast deceiver. So Andrew Lang at The Red Fairy Book , also published in 1890, follows Tabart. From Tabart/Lang or Jacobs, it is difficult to determine which of the two versions is closer to the oral version: while specialists such as Katherine Briggs, Philip Neal or Maria Tatar prefer Jacobs' version, others such as Jonah and Peter Opie consider it should be “nothing but a reworking of a text that has continued to be printed for more than half a century. "

Jack trades his cow for beans. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Summary (Jacobs version)

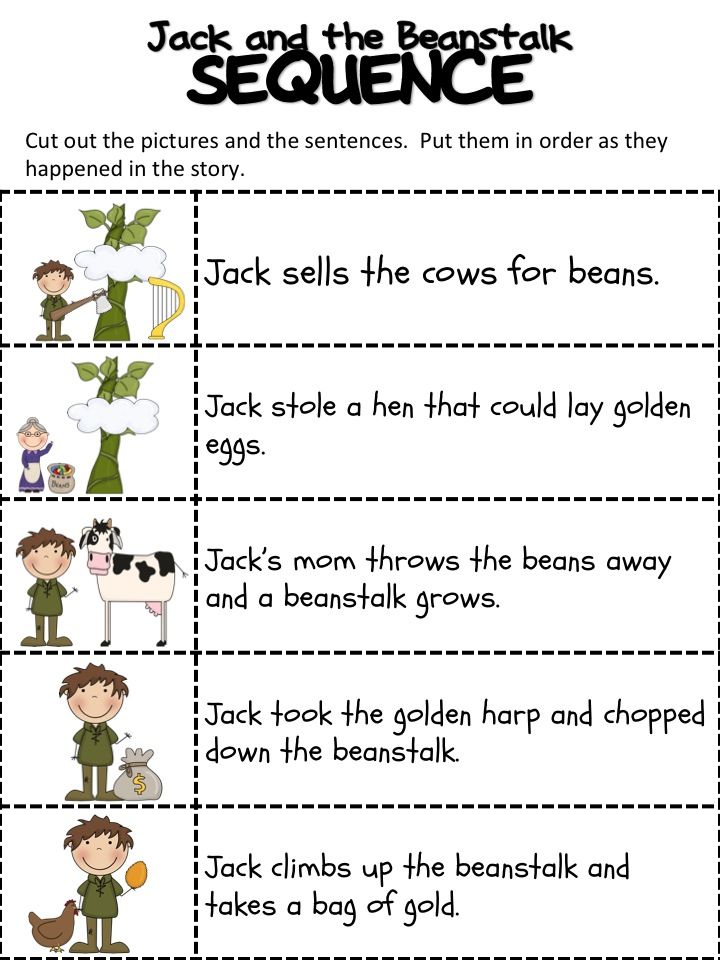

In Jacobs' version of the tale, Jack is a boy who lives alone with his widowed mother. Their only source of existence is milk from a single cow. One morning they realize that their cow is no longer producing milk. Jack's mother decides to send her son to sell her in the market.

Jack's mother decides to send her son to sell her in the market.

Along the way, Jack meets a strange looking old man who greets Jack by his first name. He manages to convince Jack to trade his cow for beans, he says "magic": if we plant them at night, in the morning they will grow to heaven! When Jack returns home with no money but only a handful of beans, his mother gets angry and throws the beans out the window. She punishes her son for his gullibility by sending him to bed without supper.

« Phee-foo-foom, I can smell the Englishman's blood. ". Arthur Rackham's illustration from English Tales by Flora Annie Steele, 1918.

While Jack sleeps, the beans sprout from the ground, and by morning a giant stalk of beans has grown in the place where they were thrown. , Jack sees a huge rod rising into the sky and decides to immediately climb to its top.

At the top he finds a broad road which he chooses and which leads him to a large house. On the threshold of a large house stands a large woman. Jack asks her to offer him dinner, but the woman warns him: her husband is a cannibal, and if Jack doesn't turn around, he risks serving dinner to her husband. Jack insists, and the giantess cooks a meal for him. Jack is not halfway to the meal when footsteps are heard, causing the whole house to shake. The giantess hides Jack in the oven. The ogre appears and immediately senses the presence of a human:

On the threshold of a large house stands a large woman. Jack asks her to offer him dinner, but the woman warns him: her husband is a cannibal, and if Jack doesn't turn around, he risks serving dinner to her husband. Jack insists, and the giantess cooks a meal for him. Jack is not halfway to the meal when footsteps are heard, causing the whole house to shake. The giantess hides Jack in the oven. The ogre appears and immediately senses the presence of a human:

« Phi-fi-fo-foom!

I smell the blood of an Englishman,

whether he is alive or dead,

I will have his bones to grind my bread. "

What does it mean:

« Fi-fi-fo-foom!

I sniff the blood of an Englishman,

Dead or alive,

I have to grind his bones to make bread. "

The ogre's wife tells him that he has his own thoughts and that the smell he smells is probably the smell of the remains of a little boy that he enjoyed the day before. The ogre leaves, and as Jack is ready to jump out of his hiding place and wrap his legs around his neck, the giantess tells him to wait until her husband naps. After the ogre swallows, Jack sees him take some bags from the chest and count the gold coins in them until he falls asleep. So Jack tiptoes out of the oven and runs off carrying one of the bags of gold. He descends the bean stalk and brings gold to his mother.

The ogre leaves, and as Jack is ready to jump out of his hiding place and wrap his legs around his neck, the giantess tells him to wait until her husband naps. After the ogre swallows, Jack sees him take some bags from the chest and count the gold coins in them until he falls asleep. So Jack tiptoes out of the oven and runs off carrying one of the bags of gold. He descends the bean stalk and brings gold to his mother.

Jack escapes a third time, carrying a magic harp. The ogre is on his trail. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Gold allows Jack and his mother to live for a while, but there comes a time when it all disappears and Jack decides to return to the top of the bean stalk. On the threshold of a large house, he again finds the giantess. She asks him if he had already arrived the day her husband noticed one of her bags of gold was missing. Jack tells her that he is hungry and cannot talk to her until he has eaten. The giantess prepares food for him again . .. Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

.. Everything goes like last time, but this time Jack manages to steal a goose that every time we say "ponds" lays a golden egg. He returns her to his mother.

Soon an unsatisfied Jack feels the urge to climb back to the top of the bean stalk. So the third time he climbs up the stick, but instead of going straight to the big house, when he comes to it, he hides behind a bush and waits before entering the house. Ogre, that giantess went out for water. There is another cache in the house, in a "pot". A couple of giants are back. Once again, the ogre senses Jack's presence. The giantess then tells her husband to look in the oven because that's where Jack used to hide. Jack is gone and they think it is the smell of the woman the ogre ate the day before. After dinner, the ogre asks his wife to bring him a golden harp. The harp sings until the ogre falls asleep, and Jack takes the opportunity to get out of his hiding place. When Jack grabs the harp, she calls her master an ogre with a human voice, and the ogre wakes up. The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

The ogre chases Jack, who has grabbed the harp, towards the beanstalk. The ogre comes down the rod behind Jack, but as soon as Jack goes down, he quickly asks his mother to give him an ax with which he cuts the huge rod. The ogre falls and "breaks his crown".

Jack shows his mother a golden harp, and thanks to her and the sale of golden eggs, they both become very rich. Jack marries a great princess. And then they live happily ever after?

Variants

Three flights are missing from the 1734 parody version and the 1807 "BAT" version, but not from the bean stalk. In Tabart's version (1807), Jack, upon arriving in the giant's realm, learns from an old woman that his father's property had been stolen by the giant.

Composition

- Introduction: Jack and his mother are poor, but their cow gives milk.

- Trouble → Mission: The cow no longer gives milk

- Encounter → Magic Offer ← Earth Mission Failure: Jack meets a "wizard" - Jack accepts magic and trades a cow for one or more beans.

- Earth Sanction: Jack is punished, deprived of food (Jack is hungry). NIGHT: Jack sleeps.

- The magic happens: a stalk of a giant bean is found in the morning.

- Sky World:

- 1- e visit / 1- flight (Jack is very hungry): (a) Man-eating Jack's wife protects and hides in the oven - (b) Ogre senses Jack: Phi-Pho- fum! ("Chorus formula") - (c) Jack takes the bag of gold - (d) Ogre is unaware.

- 2- e visiting / 2- e stealing (Jack is hungry): (a) The ogre's wife doubts Jack and hides him in spite of everything in the oven - (b) Fi-fi-fo-foom! - (c) Jack takes the goose that lays the golden eggs - (d) Ogre in his house almost catches up with Jack.

- 3 - th visit / 3 e flight (Jack wants to find other treasures): (a) Jack is hiding in a pot - (b) Fee-fo-fum! - (a ') Ogre's wife condemns Jack - (c) Jack takes golden harp - (d) Ogre pursues Jack to wand.

- Conclusion: Fall and death of the ogre - Jack and his mother are rich and happy.

This plan includes several progressions, each of which takes place in three stages: in the earthly world, hunger becomes more acute (cash cow → beans → "go to bed without supper"), and in the heavenly world, hunger subsides until finally turns into a desire for more wealth, the ogre's wife gradually separates from Jack, and finally the danger posed by the ogre becomes more and more concrete.

Classification

Ogre fall. Illustration by Walter Crane.

Illustration by Walter Crane.

The tale is usually kept in Aarne-Thompson tales AT 328, corresponding to the type "The boy who steals the ogre's treasure". However, one of the main elements of the tale, namely the bean stalk, does not occur in other tales in this category. Beanstalk , similar to the one that appears in Jack and the Beanstalk , is found in other typical tales such as AT 563, "Three Magic Objects" and AT 555, "The Fisherman and His Wife". Bean Ogre's fall, on the other hand, seems to be unique to Jack .

Formula "Fi-fi-fo-fum"

The formula appears in some versions of Jack's story The Giant Killer ( XVIII - th ) and earlier, in Shakespeare's play King Lear (v.1605). We find echoes of this in the Russian fairy tale about Vasilisa the Most Beautiful , where the witch shouts: “Crazy! It smells like Russian here! (Crazy, Fu means "Phi! Pah!" In Russian).

Parallels in other tales

Among other similar tales, such as tales AT 328 "The boy stealing the cannibal's treasure", we find, in particular, the Italian tale "The Thirteenth" and the Greek tale How the dragon was deceived . Corvetto , a tale that appeared in Giambattista Basile's Pentamerone (1634–1636), is also part of this type. It is about a young courtier who enjoys the favor of the king (of Scotland) and is the envy of the other courtiers, who therefore look for a way to get rid of him. Not far from there, in a fortified castle perched atop a mountain, lives an ogre, who is served by an army of animals and who keeps certain treasures that the king is likely to desire. The enemies of Corvetto force the king to send a young man in search of a cannibal, first a talking horse, then a tapestry. When a young man enters two victorious cases of his mission, they see to it that the king orders him to capture the ogre's castle. To complete this third mission, Corvetto introduces himself to the ogre's wife, who is busy preparing a feast; he offers to help her in her task, but instead kills her with an axe. Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

Corvetto then manages to knock the ogre and all the guests of the feast into a hole dug in front of the castle gates. As a reward, the king finally extends the hand of his daughter to the young hero.

The Brothers Grimm note the analogies between Jack and the Beanstalk and the German fairy tale The Devil's Three Golden Hairs (KGM 29), in which the devil's mother or grandmother acts in a manner quite comparable to the behavior of the cannibal's wives in Jack : a female figure, protecting the child from an evil male figure. In the version of the tale "Petit Puse" (1697), Perrault's wife also comes to the aid of Puse and his brothers.

The theme of a giant plant serving as a magical staircase between the earthly world and the heavenly world is also found in other fairy tales, especially in Russian ones, for example, in "Doctor Fox" .

The tale is unusual in that in some versions the hero, although an adult, does not marry at the end, but returns to his mother. This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

This feature occurs only in a small number of other tales, such as some variations of the Russian tale Vasilisa the Beautiful .

Patterns and ancient origins of these

The bean stalk seems to be a memory of the World Tree connecting Earth with Heaven, an ancient belief that existed in Northern Europe. This may be reminiscent of a Celtic tale, an ancient form of the Axis mundi , the original myth of the cosmic tree, a magical-religious symbolic link between Earth and Heaven, allowing sages to climb to the upper halves to know the secrets of the cosmos and the conditions of human life on earth. It is also reminiscent in the Old Testament of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) and the scale of Jacob's dream (Genesis 28:11-19) ascending to Heaven.

The victory of the "small" over the "great" is reminiscent of the episode of David's victory over the giant Philistine Goliath in the Old Testament ( First Samuel 17:1-58). In the 1807 version of The Bat (1807), the "ogre" is beheaded, as was Goliath in the Old Testament story.

"The Goose that Lays the Golden Eggs", illustration for the Aesop fable by Milo Winter, taken from of the book "Isop for Children" . The motif of the "hen that lays the golden eggs" recurs in the fairy tale Jack and the Magic Bean .

Jack steals a goose that lays golden eggs, which resembles the goose with golden eggs of Aesop's fable (VII e - VI - th century BC), without coming to however this is Aesopian morality: no moral judgment is made on greed in Jack . Gold mining animals can be found in other tales such as the donkey in Peau d'âne or the donkey in Petite-table-sois-mise, Donkey-to-gold and Gourdin-sors-du. - bag , but a fact. The fact that in Jack the goose lays golden eggs does not play a special role in the development of the plot. In his Symbol Dictionary Jean Chevalier and Alain Gerbran note: “In the Celtic continental and insular tradition, the goose is the equivalent of the swan [. ..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

..]. Considered a messenger from the Other World, among the Bretons he is the object of a ban on food, along with a hare and a chicken. "

Jack also steals the golden harp. In the same Symbol Dictionary we can read that the harp “connects heaven and earth. The heroes of the Edda want to be burned with a harp on a funeral pyre: this will lead them to that world. This is the role of the psychiatrist, the harp does not fulfill it only after death; during earthly life, it symbolizes the tension between the material instincts, represented by its wooden frame and the ropes of the lynx, and the spiritual aspirations, represented by the vibrations of these ropes. They are harmonious only if they come from a well-regulated tension between all the energies of the being, this measured dynamism that symbolizes the balance of personality and self-control. "

Moral

The story shows a hero who shamelessly hides in a man's house and uses his wife's sympathy to rob him and then kill him. In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

In Tabart's moralized version, the fairy explains to Jack that a giant stole and killed his father, and Jack's actions turn into justified retribution in the process.

Meanwhile, Jacobs omits this excuse, relying on the fact that, according to his own recollection of a fairy tale heard in childhood, she was absent from it, and also on the idea that children know well, without this we should tell them in a fairy tale that theft and murder are "evil".

Many modern interpretations have followed Tabart and portrayed the giant as a villain, terrorizing little people and often stealing valuables to make Jack's behavior legal. For example, the film "The Goose Who Loves Golden Eggs" ( Jack and the Beanstalk , 1952), starring Abbott and Costello, blames Jack the giant for failure and poverty, making him guilty of theft, and little people from the lands at the foot of his dwelling, food, and possessions, including a goose that lays golden eggs, which in this version originally belonged to Jack's family. Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

Other versions suggest that the giant stole the chicken and harp from Jack's father.

However, the moral of the tale is sometimes disputed. It is, for example, a subject of discussion in Richard Brooks' Seed of Violence ( Jungle on Plank , 1955), an adaptation of the novel by Evan Hunter (i.e. Ed McBain).

A mini-series made for television by Brian Henson in 2001, Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story ) gives an alternate version of the tale, leaving Tabart's additions aside. Here, Jack's character is significantly clouded, and Henson dislikes the morally dubious actions of the hero in the original tale.

Interpretations

There are different interpretations of this tale.

At first we can read Jack's exploits in the Middle Kingdom as a fairy tale. Indeed, it is at night when Jack, deprived of his supper, is asleep that a giant bean stalk appears, and it is not uncommon to see it as a fairy tale creation, spawned by his hunger and subsequent adventures, in part because of the guilt of failing him. missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

missions. The giantess, the ogre's wife, is a projection of Jack's mother in the dream, which can be interpreted as the fact that during Jack's first visit to the Skyworld, the giantess accepts her regarding her mother's protective behavior. The ogre thus represents the absent father, whose role was to provide both, Jack and his mother, with a livelihood, a role for which Jack is now called upon to replace him. In Skyworld, Jack joins his father-turned-giant and formidable shadow - the ogre - in competition with him, who seeks to eat him, and eventually sets about the task. Causing the ogre's death, he comes to terms with his father's death and realizes that it is his duty to the one who was initially presented as worthless to take over. In this way, he also breaks the bonds that bind and hold his mother captive to his father's memory.

We can also interpret the story from a broader point of view. The giant that Jack kills before becoming the master of his fortune may represent the "big ones in this world" who exploit the "little people" and thereby provoke their rebellion, making Jack the hero of a sort of jacquerie.

Vector illustrations

The tale, reprinted many times, was drawn by famous artists such as George Cruikshank (illustrator of Charles Dickens), Walter Crane or Arthur Rackham.

Modern fixtures

Movie

Jack and beanstalk (1917)

- 1902: Jack and the Beanstalk , a ten-minute short film produced by the Edison Manufacturing Company and directed by George S. Fleming and Edwin S. Porter, with Thomas White (Jack).

- 1912: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a short film directed by J. Searle Dawley, with Gladys Hewlett (Jack), Harry Eitinge (giant) and Gertrude McCoy.

- Jack and the Beanstalk , a short film with Leland Benham (Jack) and Helen Badgley.

- 1917: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Chester M. Franklin and Sidney Franklin, with Francis Carpenter (Jack), Jim J. Traver (giant), Virginia Lee Corbin, Jane Leigh, Katherine Leigh, Violet Radcliffe and Carmen de Ryu.

- 1922: Jack and the Beanstalk , produced and directed by Walt Disney.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Herbert M. Dawley.

- 1924: Jack and the Beanstalk , short film directed by Alfred J. Goulding, with Baby Peggy and Blanche Payson.

- 1924: L'Ogre ( The Giant Killer ), short film mixing live action footage and animation, directed by Walter Lantz, starring the character Dinky Doodle (a character created in 1916 and considered one of the first cartoon characters) .

- 1931: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Dave Fleischer, starring Betty Boop.

- 1933: Mickey in Giantland ( Giantland ), an animated short produced by Walt Disney and directed by Barton Gillette, starring, as the name suggests, the character Mickey.

- 1933: Jack and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Ub Iwerks and written by Ben Hardaway, collaboration with Sheamus Culhane, music by Carl W.

Stalling (uncredited).

Stalling (uncredited). - 1943: Jack the Wabbit and the Beanstalk , an animated short film directed by Friz Freleng, music by Carl W. Stalling and starring the character Bugs Bunny.

- 1947: Mickey and the Beanstalk , an episode from Disney's Spring Scoundrel , directed by Hamilton Luske and Bill Roberts, again starring the character Mickey.

- 1952: La Poule aux Eggs d'Or ( Jack and the Beanstalk ), produced in black and white for the modern part and in color for Jean Yarbrough's fantasy tale period with Lou Costello (Jack), Buddy Baer (giant), and Costello's lifelong friend, Bud Abbott.

- 1955: Jack and the Beanstalk or Jack the Giant Killer , a British short film (China Shadow technique) directed by Lotte Reiniger with music by Freddie Phillips.

- 1955: Seed of Violence by Richard Brooks, who integrates the cartoon Jack and the Magic Bean into his film to show Richard Dadier's character's heart for tolerance towards his students.

- 1967: Shônen Jakku to Mahô-tsukai (in the United States: Jack and the Witch ) is a Japanese animated film directed by Taiji Yabushita.

- 1970: Jack and the Beanstalk , directed by Barry Mahon, with Mitch Poulos (Jack) and Renato Boraquerro (giant).

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk is a Japanese-American animated film directed by Gisaburo Sugi.

- 2013: Jack the Giant Slayer ( Jack the Giant Slayer ), a feature film directed by Bryan Singer, starring Nicholas Hoult as Jack.

- 2015: Into the Woods musical film featuring characters from fairy tales with Daniel Huttlestone as Jack.

- Tom and Jerry Jack and the Magic Bean

TV and video

- 1967: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk (1967) ), produced by Gene Kelly, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, directed by Gene Kelly, Music by Lenny Hayton, with Gene Kelly, Bobby Riha (Jack) and Ted Cassidy (giant).

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance.

The film, which is about fifty minutes long, combines real footage and animation, emphasizing music and dance. - 1973: The Goodies and Beanstalk , episode of the British TV series featuring the Goodies, a trio of actors consisting of Tim Brooke-Taylor, Graham Garden and Bill Oddie.

- 1974: Jack and the Beanstalk with Peter Jeffery.

- 1993: Jack and the Magic Bean (video), animated short film directed by Koji Morimoto, "Anime Art Video" compilation.

- 1998: Jack and the Beanstalk , British television film directed by John Henderson and starring Neil Morrissey (Jack), Griff Rhys Jones and Peter Serafinowicz.

- 2001: Jack and the Beanstalk ( Jack and the Beanstalk: The True Story ), directed by Brian Henson, with Matthew Modine (Jack), Vanessa Redgrave, Mia Sarah, Daryl Hannah, Jon Voight and JJ Feild (Jack's child) .

- 2010: Jack and the Beanstalk , an American television film directed by Gary J.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd.

Tunnicliff and starring Colin Ford, Chloe Moretz and Christopher Lloyd. - 2010: Simsala Grimm , German cartoon season 2 episode 1: Jack and the beanstalk (Hans und die Bohnenranke)

- 2013: TV series Once Upon a Time offers its own version of the tale. "Jack" here is a woman, and her real name is Jacqueline. In the universe of the series, Jacqueline allies with Prince James (charming's twin) and manipulates the giant into pretending to be his friends, rather than steal his wealth and magic beans;

- 2013: Tom and Jerry: Giant Beans , an animated television series featuring Tom and Jerry.

video games

- Attempt to adapt to Nintendo has been cancelled.

- There is an Amstrad CPC version.

- There is also a Commodore 64 version called Jack and the Beanstalk (© 1984, Thor Computer Software).

- In 2008, 24 Grimm stories were adapted into 24 episodes of a downloadable video game called American McGee's Grimm, created by American creator American McGee, also known for the game American McGee's Alice .

The essence of the game is to make the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm creepy and scary, breaking the theme of Happily Ever After . Of the 24 episodes of Jack and the Beanstalk, was released in early 2009, its third season.

The essence of the game is to make the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm creepy and scary, breaking the theme of Happily Ever After . Of the 24 episodes of Jack and the Beanstalk, was released in early 2009, its third season.

Shows

- Jack and the Magic Bean , a rock musical created by Georges Dupuy and Philippe Manca (cd Naïve/FGL/Tremolo)

- The True Story of the Magic Bean , a story and musical show by François Vincent - a recording recorded by Ouï-dire editions.

- "Jack and the Magic Bean" , a work by Sasha Chaban for symphony orchestra and narrator - commissioned by the Bordeaux orchestral ensemble under the direction of Lionel Gaudin-Villars.

Notes and links

- ↑ Tabart in The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk (1807) introduces the character of a fairy who explains to Jack the moral of the story. - Granby (2006), pp. 1-24.

- ↑ In a review of children's books for The Quarterly Review of 1842 and 1844 (volumes 71 and 74), Elizabeth Eastlake recommends a series of books beginning with Felix Summerlee's Treasury House [sic] [i.

e. Henry Cole], including a book of England's traditional Children's Songs , Beauty and the Beast , Jack and the Beanstalk and other old friends, all charmingly performed and beautifully illustrated." - quoted by Summerfield (1980), pp. 35-52.

e. Henry Cole], including a book of England's traditional Children's Songs , Beauty and the Beast , Jack and the Beanstalk and other old friends, all charmingly performed and beautifully illustrated." - quoted by Summerfield (1980), pp. 35-52. - ↑ a b c and d (en) "The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk ", available from surlalunefairytales.com. — Page consulted June 12, 2010

- ↑ a and b Tatar (2002), p. 132.

- ↑ a and b Opie (1974).

- ↑ (in) The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk: Recording and Facsimile, about the Hockcliff Project.

- ↑ a b and c Goldberg (2001), p. 12.

Tale collected by Johann Georg von Hahn in Griechische und Albanesische Märchen , 1854

Tale collected by Johann Georg von Hahn in Griechische und Albanesische Märchen , 1854 - ↑ (in) Corvetto at surlalune.com, English translation of the tale.

- ↑ (en) Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (eds.), The Devil's Three Golden Hairs, in Selected Stories of the Brothers Grimm , trad. Frédéric Baudry, Hachette, Paris, 1900, p. 146 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

- ↑ (ru) William Ralston Shedden (ed.), "The Fox Doctor" in fairy tales popular in Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 277 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

- ↑ (en) William Shedden Ralston (ed.

), "Vasilisa la Belle", in Popular Tales of Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 147 St. - Online at the Gallica website.

), "Vasilisa la Belle", in Popular Tales of Russia , trans. Loys Brueyre, Hachette, Paris, 1874, p. 147 St. - Online at the Gallica website. - ↑ Tatarsky (1992), p. 199.

- ↑ Eliade (1952). 9Chevalier-Gheerbrant (1992), p. 392.

- ↑ Tatarsky (1992), p. 198.

- ↑ Nazzaro (2002), pp. 56-59.

- ↑ Cruikshank (1854).

- ↑ Crane (1875).

- ↑ Rackham (1913).

- ↑ (in) Jack and the Beanstalk , sealntera.com.

- ↑ a b and c Available in addition to DVD, Jack's Giant Fighter , MGM Home Entertainment - Ciné Malta, coll. "Cult & Underground", 2002. EAN 3-545020-008485.

- ↑ a and b Find out more.

- ↑ Assigned to by Drive In Movie when announcing this film's broadcast on August 10, 2018 at 9:00 pm. However, this title does not appear in the subtitles of the film produced by Bach Films.

- ↑ Process Super Color, mentioned in the credits.

- ↑ (in) Jack and the Beanstalk at Movie Database at Internet

- ↑ Downloadable version from catsuka.com.

- ↑ " TREMOLO EDITIONS PRODUCTIONS " on TREMOLO EDITIONS PRODUCTIONS (accessed March 22, 2016)

- ↑ " FGL Music - Jack and the Magic Bean - Tale Musical Pop Rock (Jack and the Magic Bean) ", available at www.fglmusic.com (accessed March 22, 2016)

Bibliography

Versions / editions of the tale

- (en) [Crane] Jack and the Beanstalk , George Routledge and Sons, London, 1875. Jack and the Beanstalk, in Bluebeard picture book , Walter Crane, ill.

, George Routledge and Sons , London, [ca. 1875]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

, George Routledge and Sons , London, [ca. 1875]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website. - (en) George Cruikshank (ed., ill.), "The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk", in Fairy Library , David Bog, London, [c.1853-1854]. — Notice and facsimile of mutilated copy at The Hockliffe Project website.

- (en) [Heartland] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Edwin Sidney Heartland (ed.), English Tales and Other Folk Tales , Walter Scott Publishing Company, London, [c.1890]. - Send text messages online at surlalune.com.

- (en) [Jacobs] "Jack and the Beanstalk", Joseph Jacobs (ed.

), English Tales , David Nutt, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com.

), English Tales , David Nutt, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com. - (en) [Lang] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Andrew Lang (ed.), The Red Fairy Book , Longmans, Green and Company, London, 1890. - Text online at surlalune.com.

- (en) [McLaughlin] Jack and the Beanstalk, R. Andre (?) ill., McLaughlin Brothers, Sat. "Young Men Series", New York, 1888.

- (en) [Nesbit] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in E. Nesbit, "Old Children's Stories" , ill. W. H. Margetson, Henry Froude and Hodder and Stoughton, Sat. "Children's Bookcase", London 1908. - Text online with facsimile at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Orr] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in "The Stories of Jack and the Beanstalk [ and Michael Scott ]", Francis Orr & Sons, Glasgow, [1820]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Park] The Amazing Story of Jack and the Beanstalk, which details his travels through the beanstalk, how he got hold of the sacks of gold, and how he killed the ogre by chopping down the bean. stem , A. Park, London, [c.1840]. - Notice and facsimile on the Hockliffe Project website.

- (en) [Parsons] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Elsie Clews Parsons (ed.

), "Tales from Maryland and Pennsylvania", in Journal of American Folklore , vol. 30, n o 116 (April ). - Send text messages online at surlalune.com.

), "Tales from Maryland and Pennsylvania", in Journal of American Folklore , vol. 30, n o 116 (April ). - Send text messages online at surlalune.com. - (en) Arthur Rackham , Arthur Rackham Picture Book , W. Heinemann, London, 1913.

- (en) [Reynolds] "Jack and the Beanstalk: A New Version", in Jack and the Beanstalk, and Little Jane and Her Mother , William J. Reynolds & Co., Boston, 1848]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

- (en) [Tabart] The Story of Jack and the Beanstalk , Benjamin Tabart - Juvenile and School Library, London 1807 - Notice and facsimile on the website "Hawcliffe Project".

- (en) [Vredenberg] "Jack and the Beanstalk", in Edrik Vredenberg et al. (ed.), Old Tales , Francis Brundage, E. J. Andrews et al. ill., Raphael Tuck & Sons, London, [before 1919]. - Send online text messages with a fax at the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) website.

Research

- (en) Christine Goldberg, "Composition Jack and the Beanstalk ", at Marvels & Tales , vol. 15, No 1 (2001), pp. 11-26. - Online at the Project Muse website.

- (en) Matthew Orville Granby, "Tame Fairies Are Good Teachers: The Popularity of Early British Fairy Tales", in The Lion and the Unicorn , 30.

1 ().

1 (). - (en) Jonah and Peter Opie, Classic Tales , New York, Oxford University Press, New York, 1974.

- ( fr ) Geoffrey Summerfield, "Creating a Home Treasury", at children's literature , 8 (1980).

- (en) Maria Tatar, Annotated Classical Fairy Tales , W. W. Norton, 2002 (ISBN 0-393-05163-3) .

- (ru) Maria Tatarka, cut off their heads! : Tales and Culture of Childhood , Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1992 (ISBN 0-691-06943-3) .