Math skills for toddlers

Help Your Child Develop Early Math Skills

Before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. Learn what informal activities give children a head start on early math skills when they start school.

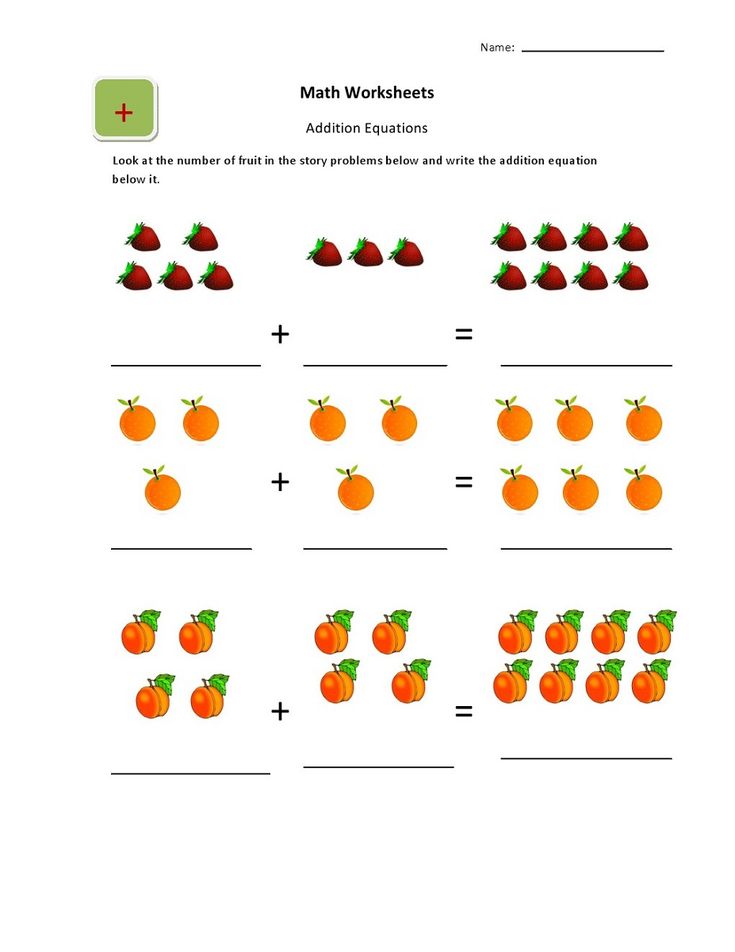

Children are using early math skills throughout their daily routines and activities. This is good news as these skills are important for being ready for school. But early math doesn’t mean taking out the calculator during playtime. Even before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. For example, Thomas has two cars; Joseph wants one. After Thomas shares one, he sees that he has one car left (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001, p. 201). Other math skills are introduced through daily routines you share with your child—counting steps as you go up or down, for example. Informal activities like this one give children a jumpstart on the formal math instruction that starts in school.

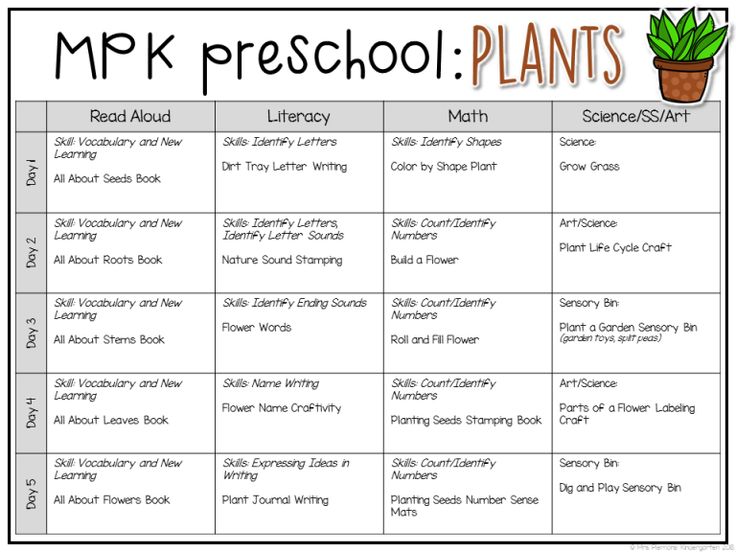

What math knowledge will your child need later on in elementary school? Early mathematical concepts and skills that first-grade mathematics curriculum builds on include: (Bowman et al., 2001, p. 76).

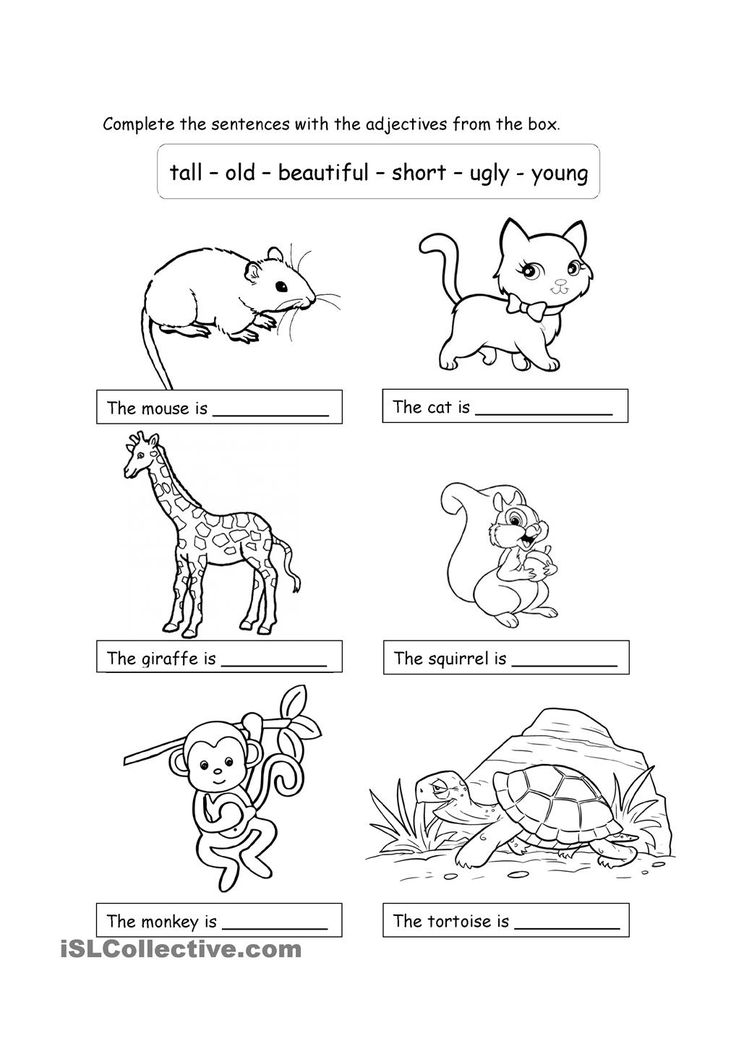

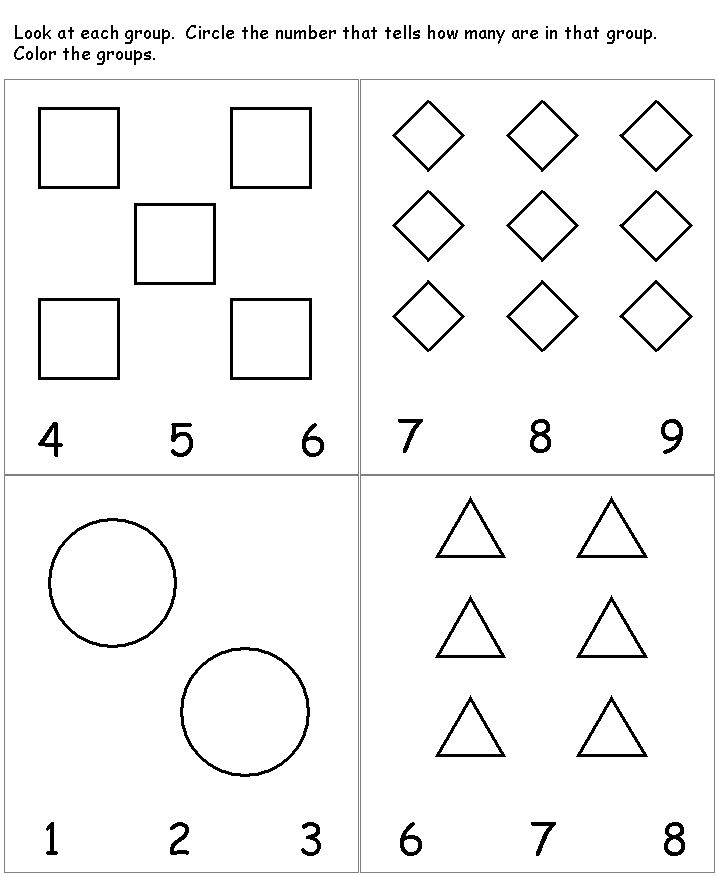

- Understanding size, shape, and patterns

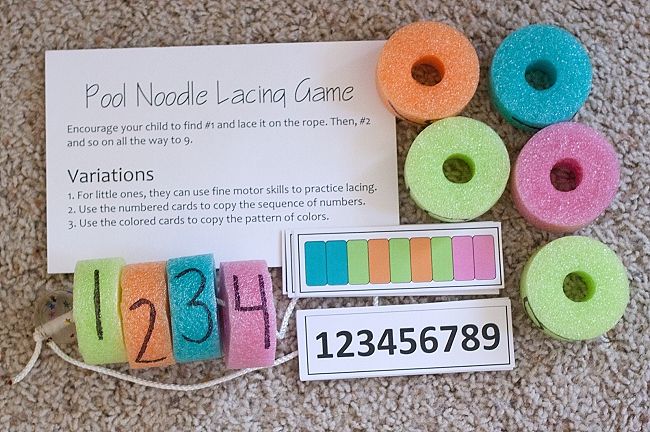

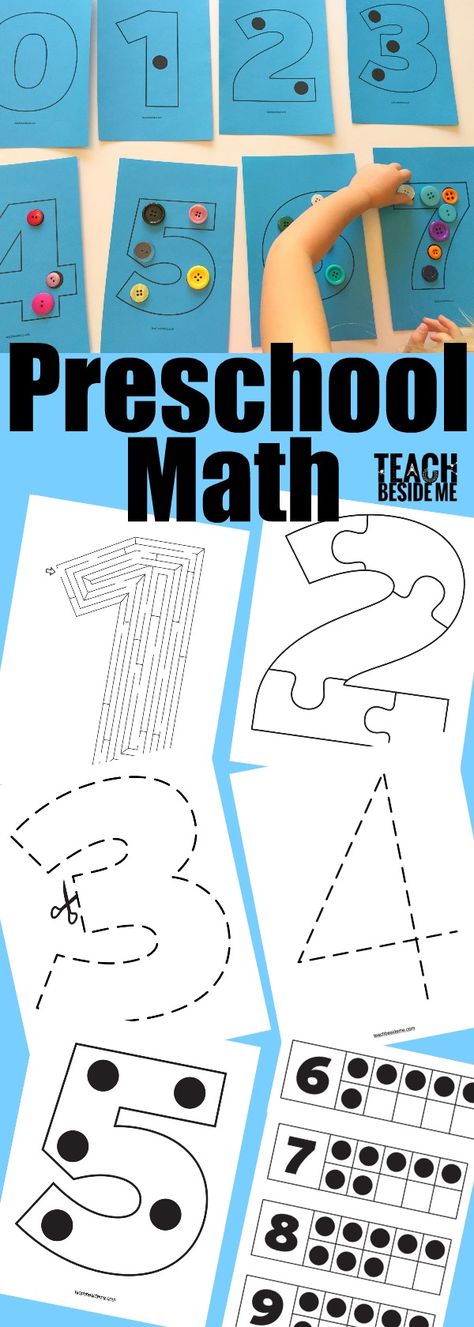

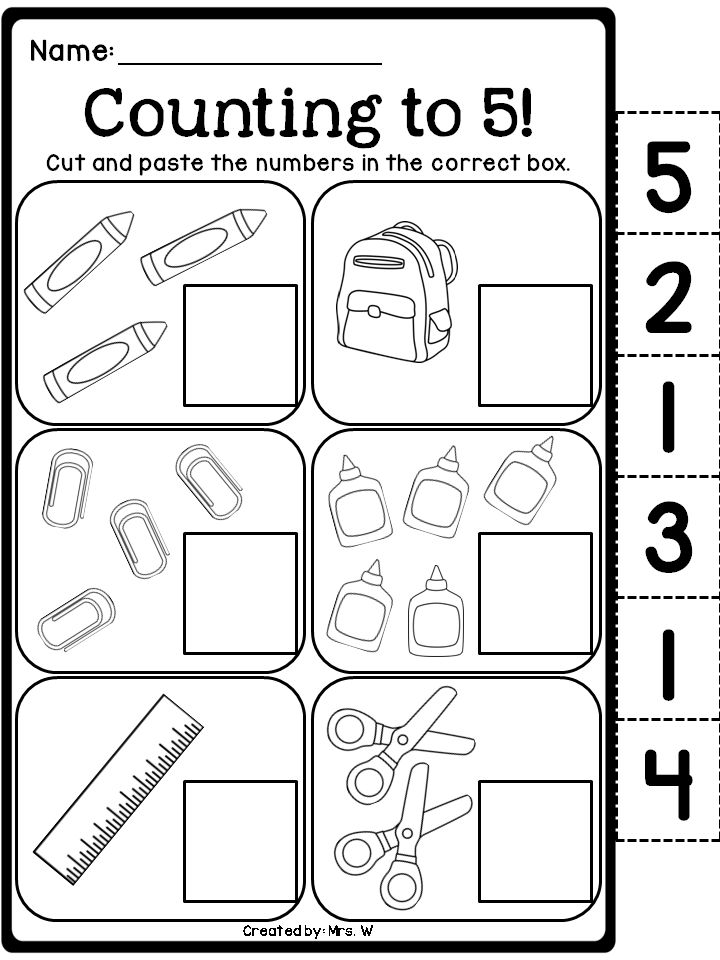

- Ability to count verbally (first forward, then backward)

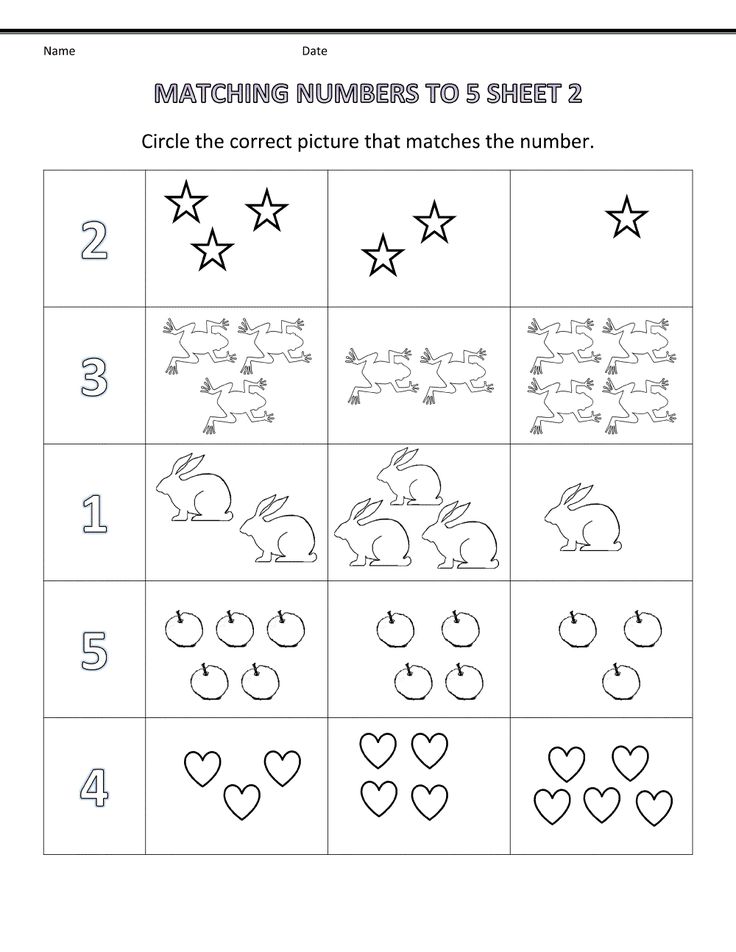

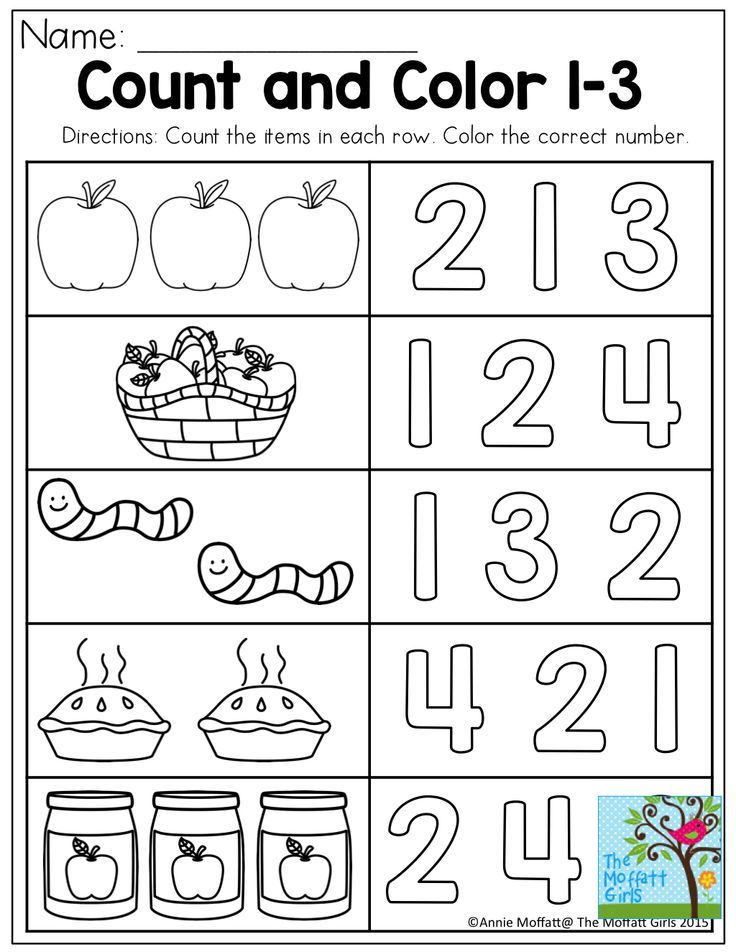

- Recognizing numerals

- Identifying more and less of a quantity

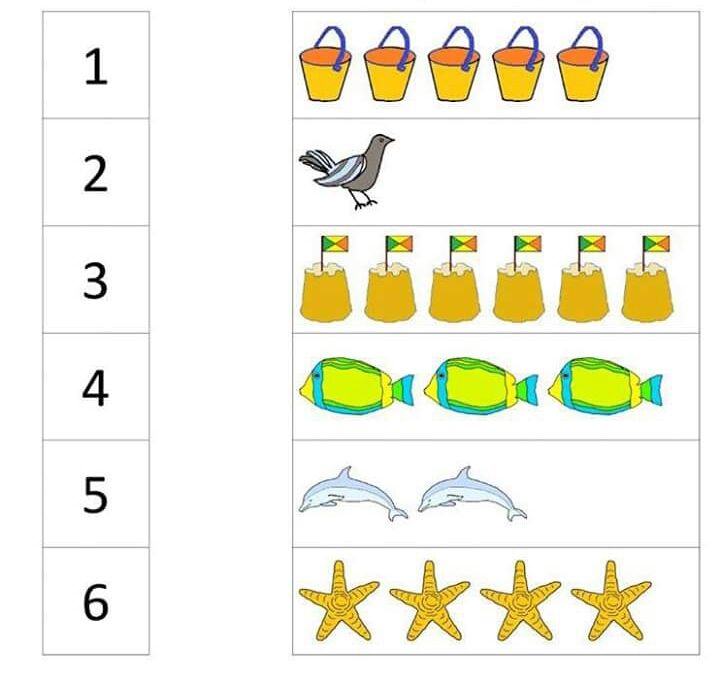

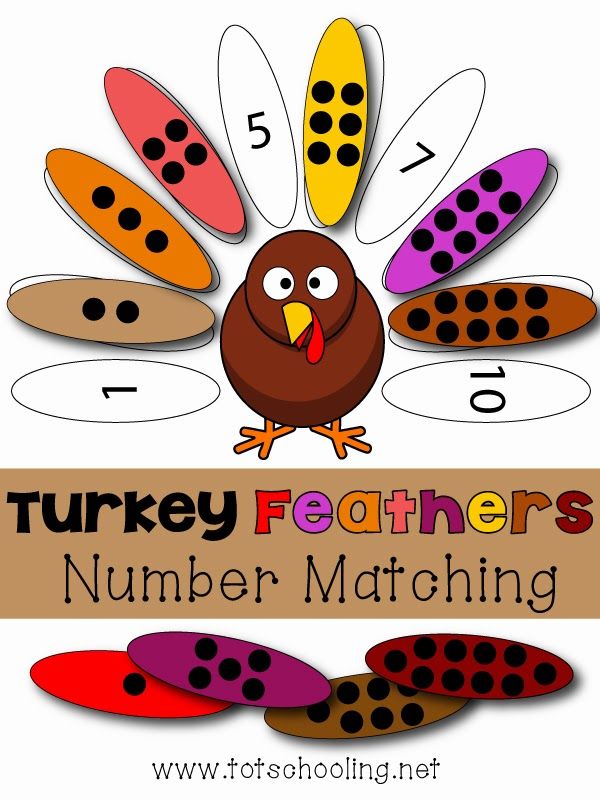

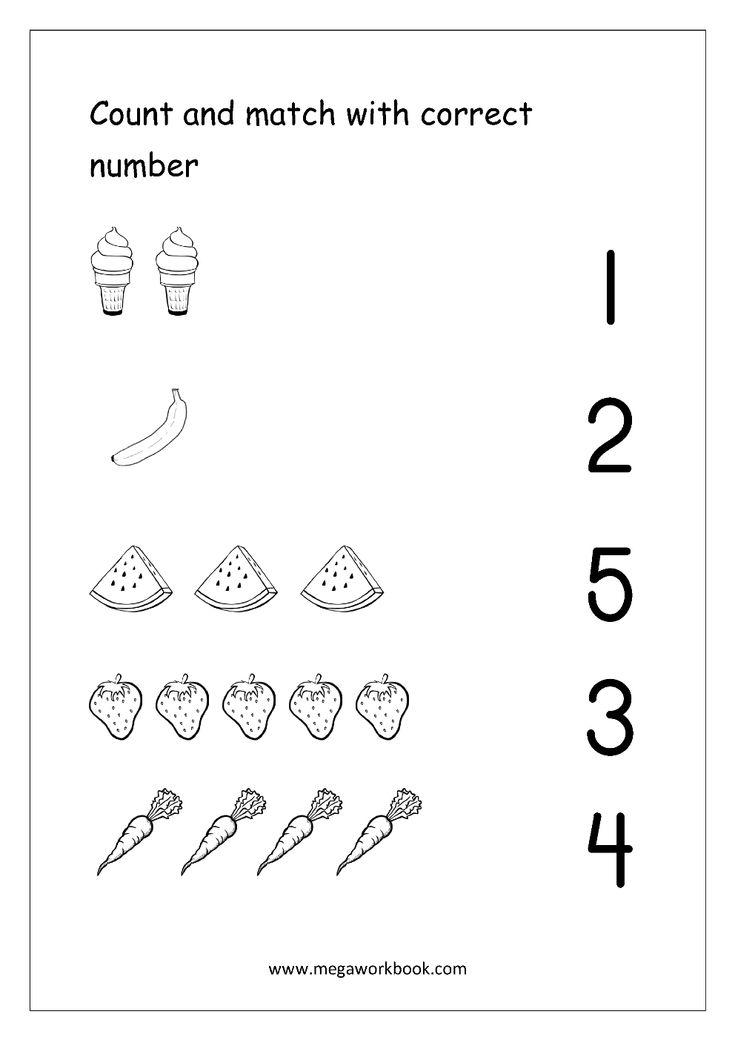

- Understanding one-to-one correspondence (i.e., matching sets, or knowing which group has four and which has five)

Key Math Skills for School

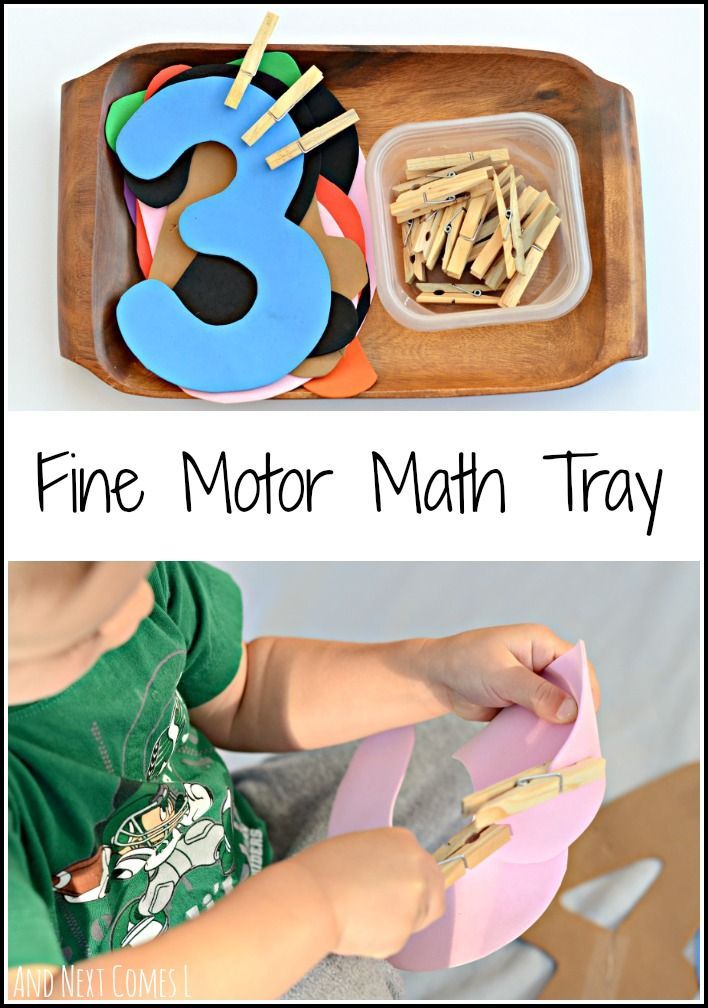

More advanced mathematical skills are based on an early math “foundation”—just like a house is built on a strong foundation. In the toddler years, you can help your child begin to develop early math skills by introducing ideas like: (From Diezmann & Yelland, 2000, and Fromboluti & Rinck, 1999.)

Number Sense

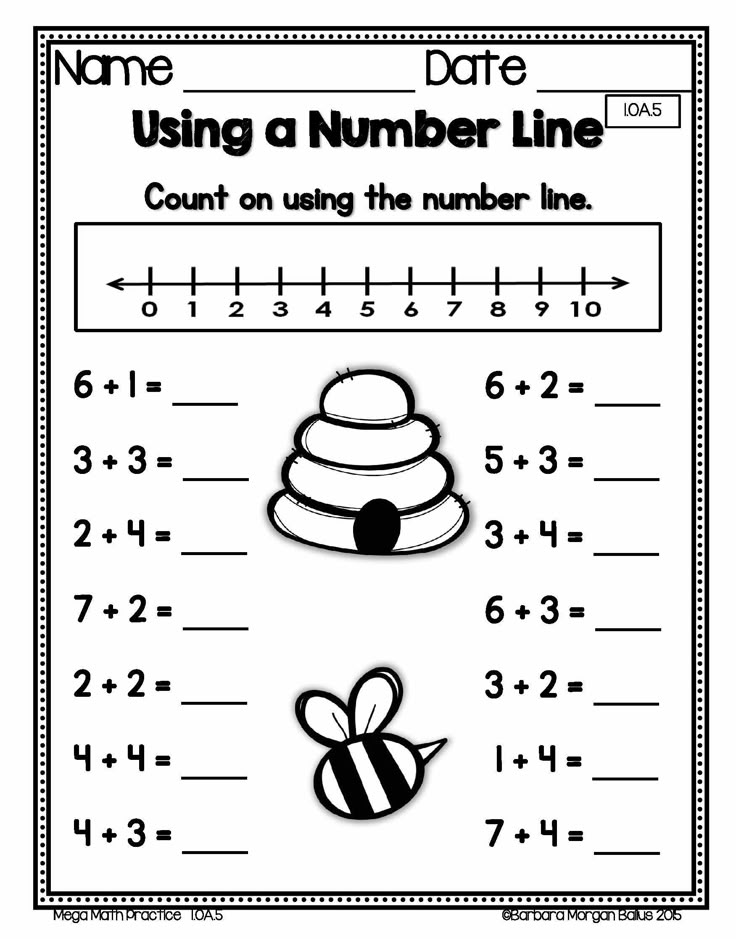

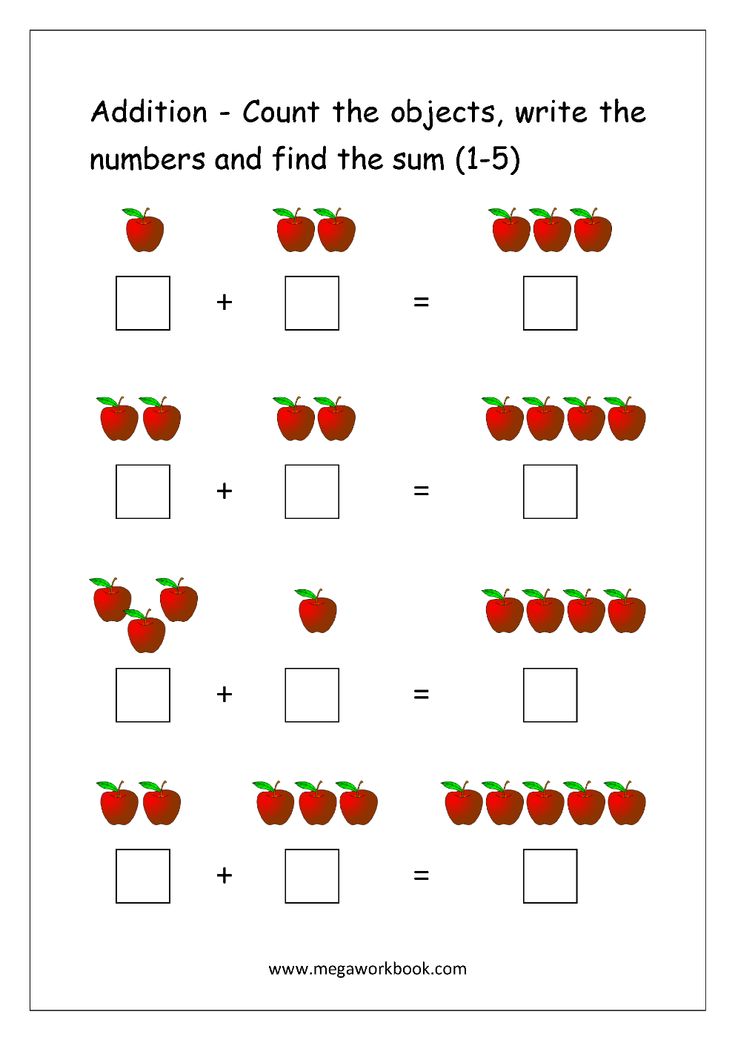

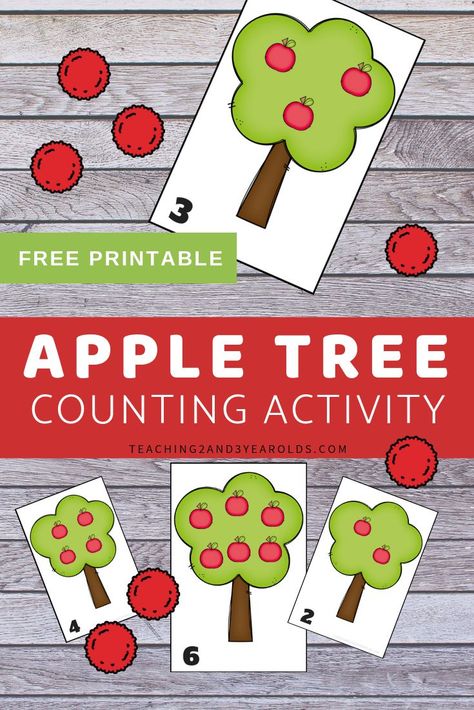

This is the ability to count accurately—first forward. Then, later in school, children will learn to count backwards. A more complex skill related to number sense is the ability to see relationships between numbers—like adding and subtracting. Ben (age 2) saw the cupcakes on the plate. He counted with his dad: “One, two, three, four, five, six…”

A more complex skill related to number sense is the ability to see relationships between numbers—like adding and subtracting. Ben (age 2) saw the cupcakes on the plate. He counted with his dad: “One, two, three, four, five, six…”

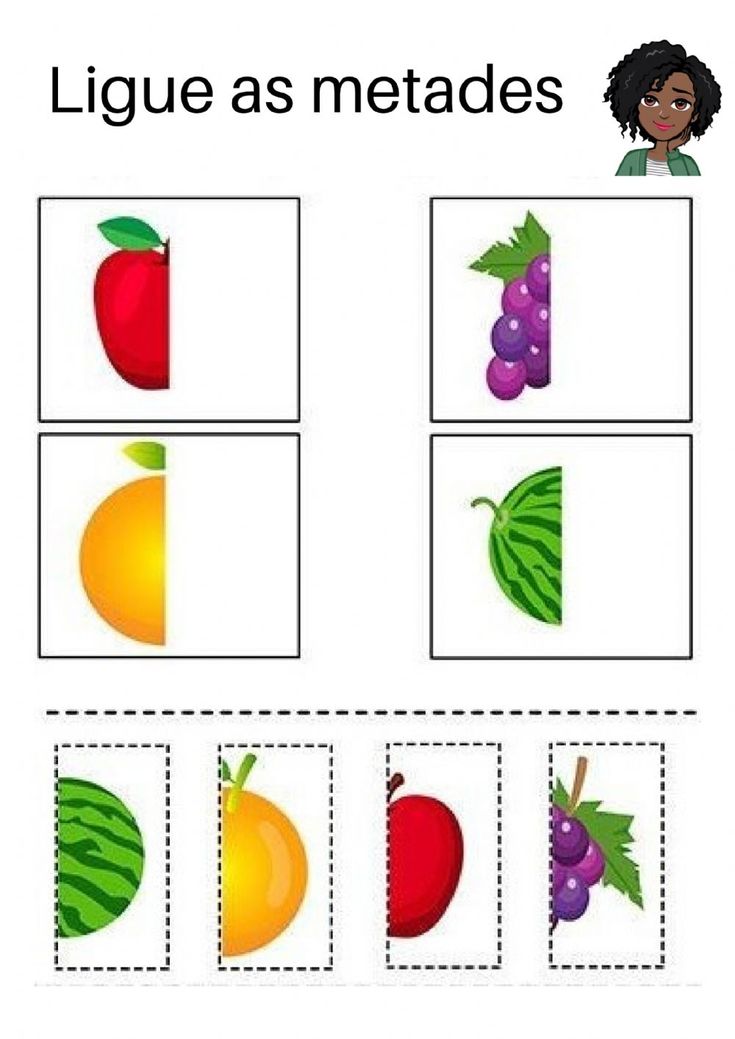

Representation

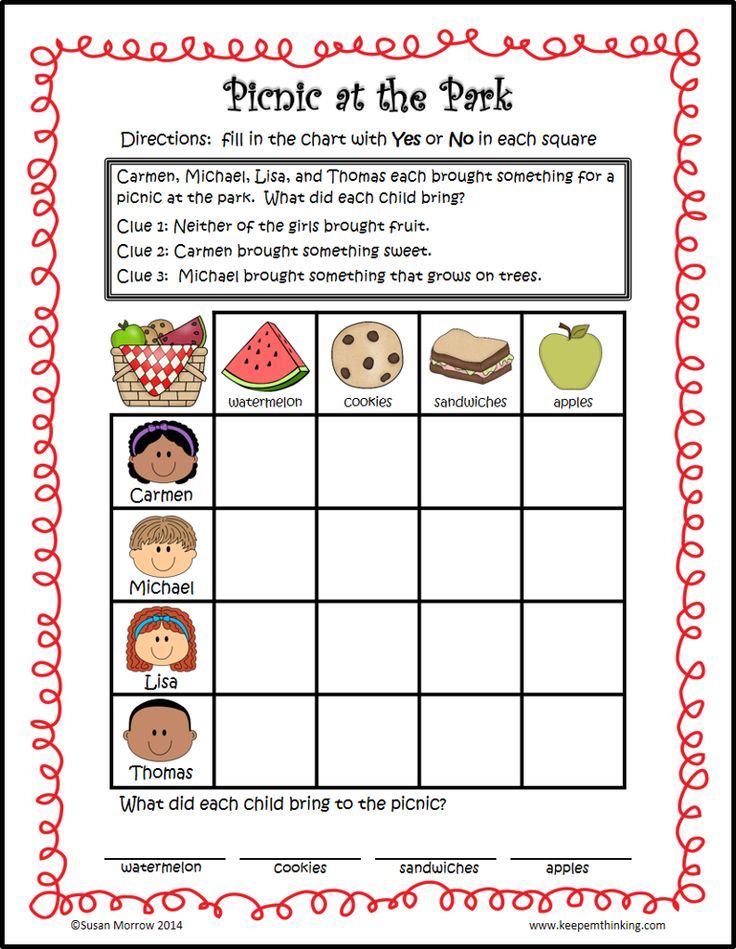

Making mathematical ideas “real” by using words, pictures, symbols, and objects (like blocks). Casey (aged 3) was setting out a pretend picnic. He carefully laid out four plastic plates and four plastic cups: “So our whole family can come to the picnic!” There were four members in his family; he was able to apply this information to the number of plates and cups he chose.

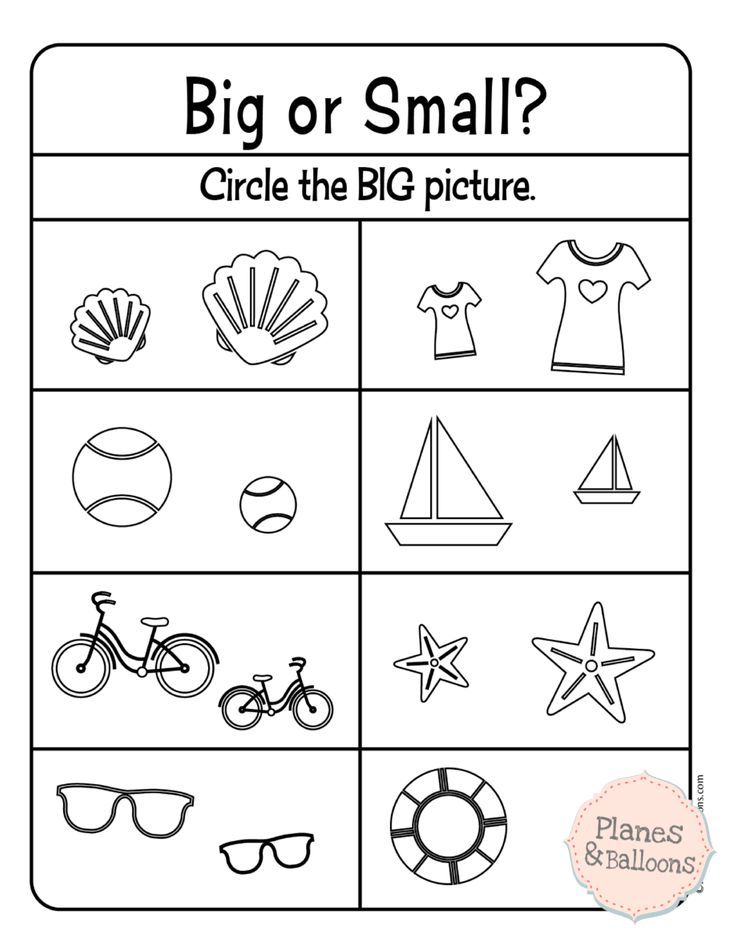

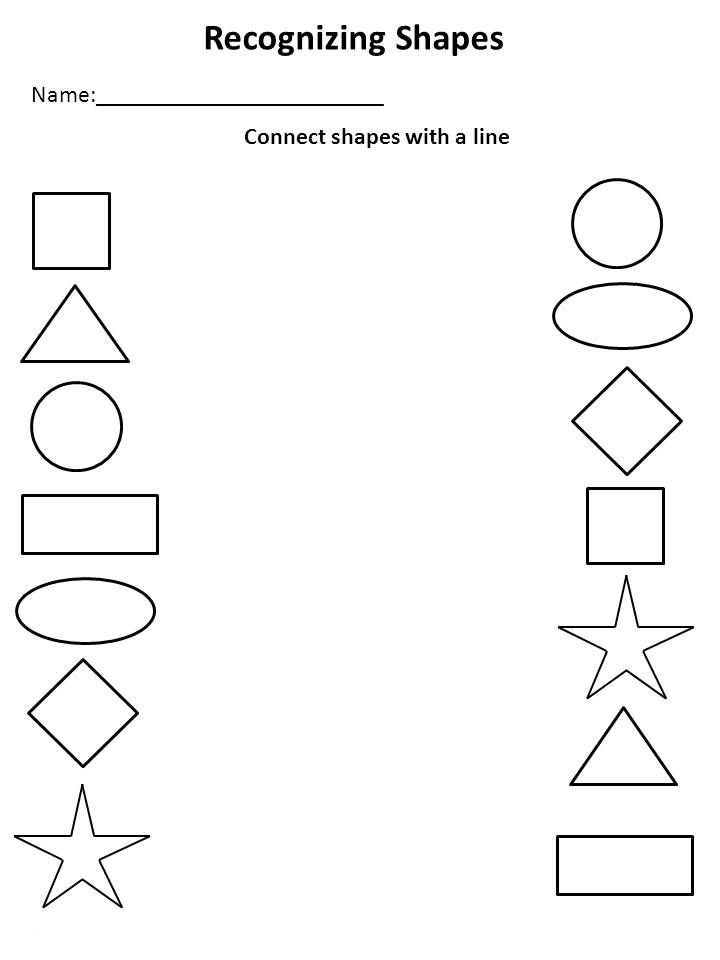

Spatial sense

Later in school, children will call this “geometry.” But for toddlers it is introducing the ideas of shape, size, space, position, direction and movement. Aziz (28 months) was giggling at the bottom of the slide. “What’s so funny?” his Auntie wondered. “I comed up,” said Aziz, “Then I comed down!”

Measurement

Technically, this is finding the length, height, and weight of an object using units like inches, feet or pounds. Measurement of time (in minutes, for example) also falls under this skill area. Gabriella (36 months) asked her Abuela again and again: “Make cookies? Me do it!” Her Abuela showed her how to fill the measuring cup with sugar. “We need two cups, Gabi. Fill it up once and put it in the bowl, then fill it up again.”

Measurement of time (in minutes, for example) also falls under this skill area. Gabriella (36 months) asked her Abuela again and again: “Make cookies? Me do it!” Her Abuela showed her how to fill the measuring cup with sugar. “We need two cups, Gabi. Fill it up once and put it in the bowl, then fill it up again.”

Estimation

This is the ability to make a good guess about the amount or size of something. This is very difficult for young children to do. You can help them by showing them the meaning of words like more, less, bigger, smaller, more than, less than. Nolan (30 months) looked at the two bagels: one was a regular bagel, one was a mini-bagel. His dad asked: “Which one would you like?” Nolan pointed to the regular bagel. His dad said, “You must be hungry! That bagel is bigger. That bagel is smaller. Okay, I’ll give you the bigger one. Breakfast is coming up!”

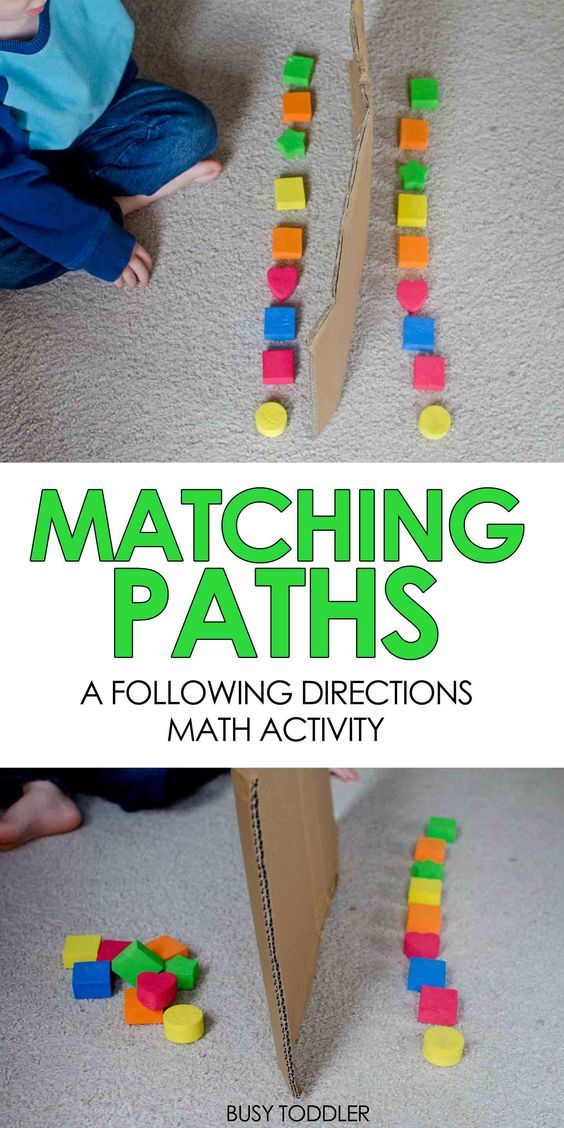

Patterns

Patterns are things—numbers, shapes, images—that repeat in a logical way. Patterns help children learn to make predictions, to understand what comes next, to make logical connections, and to use reasoning skills. Ava (27 months) pointed to the moon: “Moon. Sun go night-night.” Her grandfather picked her up, “Yes, little Ava. In the morning, the sun comes out and the moon goes away. At night, the sun goes to sleep and the moon comes out to play. But it’s time for Ava to go to sleep now, just like the sun.”

Patterns help children learn to make predictions, to understand what comes next, to make logical connections, and to use reasoning skills. Ava (27 months) pointed to the moon: “Moon. Sun go night-night.” Her grandfather picked her up, “Yes, little Ava. In the morning, the sun comes out and the moon goes away. At night, the sun goes to sleep and the moon comes out to play. But it’s time for Ava to go to sleep now, just like the sun.”

Problem-solving

The ability to think through a problem, to recognize there is more than one path to the answer. It means using past knowledge and logical thinking skills to find an answer. Carl (15 months old) looked at the shape-sorter—a plastic drum with 3 holes in the top. The holes were in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square. Carl looked at the chunky shapes on the floor. He picked up a triangle. He put it in his month, then banged it on the floor. He touched the edges with his fingers. Then he tried to stuff it in each of the holes of the new toy. Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

Math: One Part of the Whole

Math skills are just one part of a larger web of skills that children are developing in the early years—including language skills, physical skills, and social skills. Each of these skill areas is dependent on and influences the others.

Trina (18 months old) was stacking blocks. She had put two square blocks on top of one another, then a triangle block on top of that. She discovered that no more blocks would balance on top of the triangle-shaped block. She looked up at her dad and showed him the block she couldn’t get to stay on top, essentially telling him with her gesture, “Dad, I need help figuring this out.” Her father showed her that if she took the triangle block off and used a square one instead, she could stack more on top. She then added two more blocks to her tower before proudly showing her creation to her dad: “Dada, Ook! Ook!”

You can see in this ordinary interaction how all areas of Trina’s development are working together. Her physical ability allows her to manipulate the blocks and use her thinking skills to execute her plan to make a tower. She uses her language and social skills as she asks her father for help. Her effective communication allows Dad to respond and provide the helps she needs (further enhancing her social skills as she sees herself as important and a good communicator). This then further builds her thinking skills as she learns how to solve the problem of making the tower taller.

Her physical ability allows her to manipulate the blocks and use her thinking skills to execute her plan to make a tower. She uses her language and social skills as she asks her father for help. Her effective communication allows Dad to respond and provide the helps she needs (further enhancing her social skills as she sees herself as important and a good communicator). This then further builds her thinking skills as she learns how to solve the problem of making the tower taller.

What You Can Do

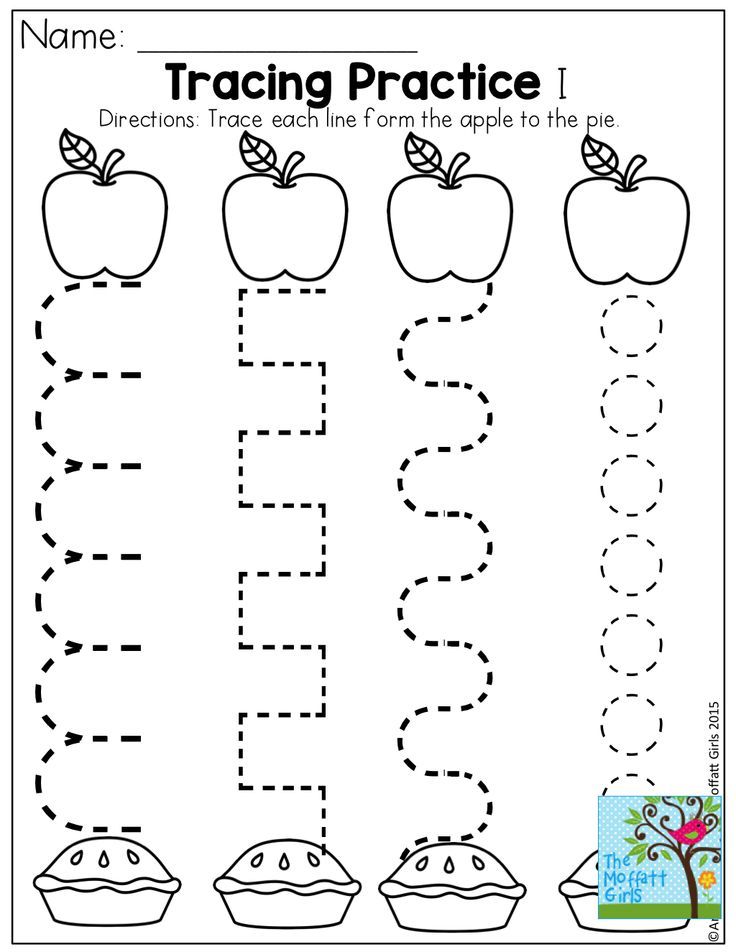

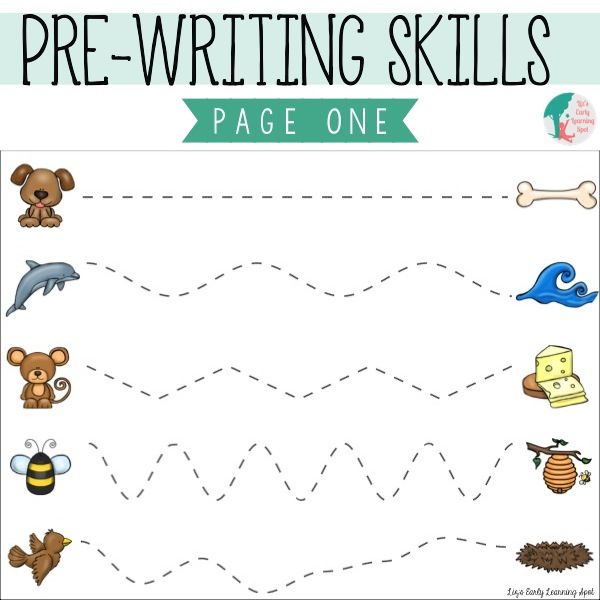

The tips below highlight ways that you can help your child learn early math skills by building on their natural curiosity and having fun together. (Note: Most of these tips are designed for older children—ages 2–3. Younger children can be exposed to stories and songs using repetition, rhymes and numbers.)

Shape up.

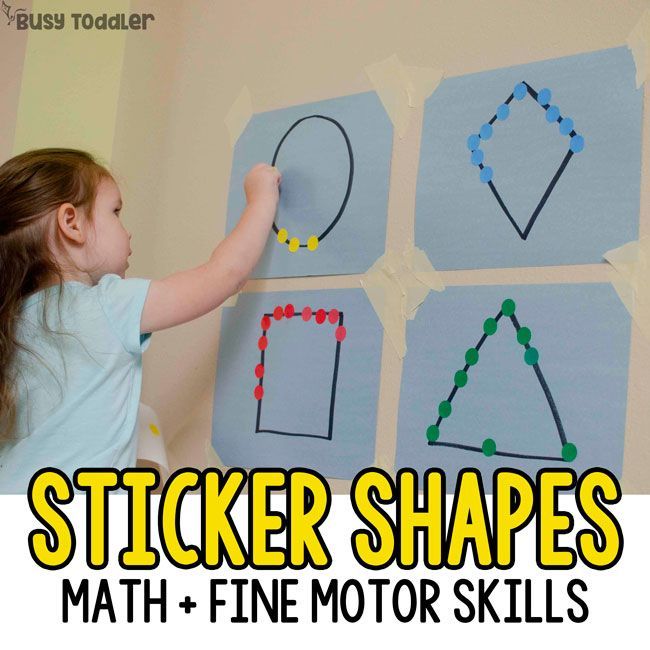

Play with shape-sorters. Talk with your child about each shape—count the sides, describe the colors. Make your own shapes by cutting large shapes out of colored construction paper. Ask your child to “hop on the circle” or “jump on the red shape.”

Ask your child to “hop on the circle” or “jump on the red shape.”

Count and sort.

Gather together a basket of small toys, shells, pebbles or buttons. Count them with your child. Sort them based on size, color, or what they do (i.e., all the cars in one pile, all the animals in another).

Place the call.

With your 3-year-old, begin teaching her the address and phone number of your home. Talk with your child about how each house has a number, and how their house or apartment is one of a series, each with its own number.

What size is it?

Notice the sizes of objects in the world around you: That pink pocketbook is the biggest. The blue pocketbook is the smallest. Ask your child to think about his own size relative to other objects (“Do you fit under the table? Under the chair?”).

You’re cookin’ now!

Even young children can help fill, stir, and pour. Through these activities, children learn, quite naturally, to count, measure, add, and estimate.

Walk it off.

Taking a walk gives children many opportunities to compare (which stone is bigger?), assess (how many acorns did we find?), note similarities and differences (does the duck have fur like the bunny does?) and categorize (see if you can find some red leaves). You can also talk about size (by taking big and little steps), estimate distance (is the park close to our house or far away?), and practice counting (let’s count how many steps until we get to the corner).

Picture time.

Use an hourglass, stopwatch, or timer to time short (1–3 minute) activities. This helps children develop a sense of time and to understand that some things take longer than others.

Shape up.

Point out the different shapes and colors you see during the day. On a walk, you may see a triangle-shaped sign that’s yellow. Inside a store you may see a rectangle-shaped sign that’s red.

Read and sing your numbers.

Sing songs that rhyme, repeat, or have numbers in them. Songs reinforce patterns (which is a math skill as well). They also are fun ways to practice language and foster social skills like cooperation.

Songs reinforce patterns (which is a math skill as well). They also are fun ways to practice language and foster social skills like cooperation.

Start today.

Use a calendar to talk about the date, the day of the week, and the weather. Calendars reinforce counting, sequences, and patterns. Build logical thinking skills by talking about cold weather and asking your child: What do we wear when it’s cold? This encourages your child to make the link between cold weather and warm clothing.

Pass it around.

Ask for your child’s help in distributing items like snacks or in laying napkins out on the dinner table. Help him give one cracker to each child. This helps children understand one-to-one correspondence. When you are distributing items, emphasize the number concept: “One for you, one for me, one for Daddy.” Or, “We are putting on our shoes: One, two.”

Big on blocks.

Give your child the chance to play with wooden blocks, plastic interlocking blocks, empty boxes, milk cartons, etc. Stacking and manipulating these toys help children learn about shapes and the relationships between shapes (e.g., two triangles make a square). Nesting boxes and cups for younger children help them understand the relationship between different sized objects.

Stacking and manipulating these toys help children learn about shapes and the relationships between shapes (e.g., two triangles make a square). Nesting boxes and cups for younger children help them understand the relationship between different sized objects.

Tunnel time.

Open a large cardboard box at each end to turn it into a tunnel. This helps children understand where their body is in space and in relation to other objects.

The long and the short of it.

Cut a few (3–5) pieces of ribbon, yarn or paper in different lengths. Talk about ideas like long and short. With your child, put in order of longest to shortest.

Learn through touch.

Cut shapes—circle, square, triangle—out of sturdy cardboard. Let your child touch the shape with her eyes open and then closed.

Pattern play.

Have fun with patterns by letting children arrange dry macaroni, chunky beads, different types of dry cereal, or pieces of paper in different patterns or designs. Supervise your child carefully during this activity to prevent choking, and put away all items when you are done.

Supervise your child carefully during this activity to prevent choking, and put away all items when you are done.

Laundry learning.

Make household jobs fun. As you sort the laundry, ask your child to make a pile of shirts and a pile of socks. Ask him which pile is the bigger (estimation). Together, count how many shirts. See if he can make pairs of socks: Can you take two socks out and put them in their own pile? (Don’t worry if they don’t match! This activity is more about counting than matching.)

Playground math.

As your child plays, make comparisons based on height (high/low), position (over/under), or size (big/little).

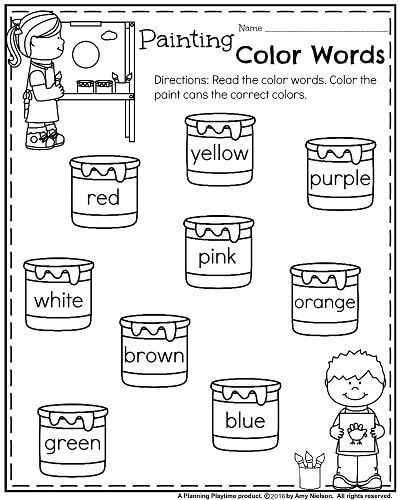

Dress for math success.

Ask your child to pick out a shirt for the day. Ask: What color is your shirt? Yes, yellow. Can you find something in your room that is also yellow? As your child nears three and beyond, notice patterns in his clothing—like stripes, colors, shapes, or pictures: I see a pattern on your shirt. There are stripes that go red, blue, red, blue. Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

Graphing games.

As your child nears three and beyond, make a chart where your child can put a sticker each time it rains or each time it is sunny. At the end of a week, you can estimate together which column has more or less stickers, and count how many to be sure.

References

Bowman, B.T., Donovan, M.S., & Burns, M.S., (Eds.). (2001). Eager to learn: Educating our preschoolers. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Diezmann, C., & Yelland, N. J. (2000). Developing mathematical literacy in the early childhood years. In Yelland, N.J. (Ed.), Promoting meaningful learning: Innovations in educating early childhood professionals. (pp.47–58). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Fromboluti, C. S., & Rinck, N. (1999 June). Early childhood: Where learning begins. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, National Institute on Early Childhood Development and Education. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/EarlyMath/title.html

Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/EarlyMath/title.html

Supporting Math Skills in Infants and Toddlers

Infants and toddlers naturally explore math concepts as they play. In this brief, learn how to make children's everyday experiences mathematical. Find the most up-to-date information to answer three prompts: “What does research say?”; “What does it look like?”; and “Try this!” There’s also an accompanying resource, Connecting at Home. It offers tips for families on ways to add math to their daily activities and routines.

Download the PDF

Research Notes

Math concepts are a natural part of our routines and activities throughout the day. This is true for children and adults. Math refers to numbers and counting, but it also includes knowledge of shapes, patterns, measurement, and spatial sense. Infants and toddlers naturally explore these math concepts as they play. Adults can highlight the math in children’s everyday experiences by providing language and support.

The Take Home

- Infants and toddlers build early foundations for math during play and daily routines.

- Math is integral to learning across developmental domains.

- Effective practices for building math skills include creating responsive environments, using intentional language, encouraging family engagement, and incorporating math into everyday experiences.

What Does Research Say?

- Math isn’t just a subject to be taught once children start school. Math skills begin developing early. For example, infants pay attention to quantity during their interactions with people and the environment. They learn about quantity as they reach or look for more than one object. Supporting math skills in early childhood is related to later success in school. Children’s math skills in preschool predict how well they will score in third grade reading and math.

- Infants and toddlers need time and space to play in open-ended ways with varied materials to boost their emerging math skills.

This is a big part of what children do naturally during play. Adults can introduce math concepts like size and shape, and spatial words like in, between, and under during any type of play or routine. When working with children who are dual language learners (DLLs), adults should speak in short sentences and provide key math concepts in English and the child’s home language, when possible.

This is a big part of what children do naturally during play. Adults can introduce math concepts like size and shape, and spatial words like in, between, and under during any type of play or routine. When working with children who are dual language learners (DLLs), adults should speak in short sentences and provide key math concepts in English and the child’s home language, when possible. - Children benefit from early spatial play. Research shows there is a relationship between how often young children play with puzzles and their later spatial skills. Infants and toddlers develop spatial skills by mouthing objects, turning toys in their hands and looking at them from different perspectives, and using materials like nesting cups or shape sorters. Spatial skills can be improved with practice at any age.

- Math skills are connected to other learning domains, such as language and social and emotional development. When infants and toddlers feel emotionally and physically safe, they are more confident to explore their world, which supports the development of math skills.

This might be experimenting with how tall they can build a tower before it falls or climbing the steps to go down a slide. Responsive adults provide math language to describe the concepts children are exploring.

This might be experimenting with how tall they can build a tower before it falls or climbing the steps to go down a slide. Responsive adults provide math language to describe the concepts children are exploring. - Families play an important role in teaching young children math skills so they are ready for school. Research shows that children are more likely to have higher math scores when their parents include math activities at home. The best way to do this is to encourage families to explore math concepts with children during their regular daily activities and routines.

What Does It Look Like?

- All learning (including math!) happens in the context of relationships. Children need consistent, responsive caregivers to feel safe and supported. When they feel this way, they are more likely to explore and learn new skills. Responsive learning environments build on the diverse languages, cultures, experiences, and interests of each child. To support and be responsive to children who are DLLs, adults use visual cues and identify math concepts in English and their home language when possible.

- Math exploration and learning happen everywhere. Children learn math skills in their early learning setting, but also in places like the grocery store, playground, and in their home. Infants and toddlers learn about quantity as an adult counts two apples to put into their shopping cart. They develop early spatial skills as adults push them on the swings or as they go down a slide. At home, math can be found from playtime to mealtime. For example, a caregiver says as he prepares lunch, “Your sandwich is a square. If we cut it in half, it makes two rectangles.”

- Young children naturally explore math concepts as they play, and adults support their math knowledge and vocabulary with the language they use. Adults intentionally use math talk during what they’re already doing every day. They introduce spatial concepts like, “I’m going to pick you up and then put you down in your crib.” Or they can compare the size of their shoes as they get ready to go outside, “Your sneakers are smaller than my sneakers.

” Adults can use math language during mealtimes, “How many blueberries do you have left? Do you need more?” The more math language children hear each day, the greater the growth of their math knowledge.

” Adults can use math language during mealtimes, “How many blueberries do you have left? Do you need more?” The more math language children hear each day, the greater the growth of their math knowledge. - Infants and toddlers need time and space to play in open-ended ways with varied materials to boost emergent math skills. Special math materials or tools are not necessary. Materials can be anything from cups or containers to socks from the laundry. Infants and toddlers learn about measurement as they fill and dump water, sand, or dirt. They can use those same cups to learn about size and how things fit together as they try to nest or stack them. Adults can use everyday materials with children with identified disabilities or suspected delays by choosing materials that are easy to grasp and manipulate and by offering support for children’s play, such as holding the large cups steady as they stack.

- Support families in thinking of ways important cultural skills or traditions include math concepts.

They may explore patterns as they clap and dance to music together. They explore numbers and measurement while making the family’s favorite dish.

They may explore patterns as they clap and dance to music together. They explore numbers and measurement while making the family’s favorite dish. - Daily routines are full of opportunities for developing math skills. A predictable schedule and routine help infants and toddlers learn about the concept of time. For example, naptime always happens after a bottle and books. Going through routines also teaches children about patterns: We always wash our hands before we eat.

Try This!

- Encourage exploration of different, safe environments and materials. Infants and toddlers develop a sense of numbers and are introduced to shape and size as they explore different non-chokeable objects with their hands or mouth.

- Head outside. Talk about math concepts as you look for patterns on the buildings, collect rocks to sort and stack, or see who can run "the fastest!"

- Stick to a routine. When you follow the same routine before nap or meal time, children not only feel more secure, but they learn about patterns and measurement concepts, like time.

- Listen and move to music together. It helps infants and toddlers develop a sense of their body in space that encourages spatial awareness. Sing songs with hand movements like “Open, Shut Them” and “Pat-a-cake.” Songs with repeating words or actions build skills in recognizing patterns.

- Help families “find the math” in the things they already do every day. Toddlers can practice sorting toys into bins during clean up time or discover spatial concepts as they climb up stairs or through blanket forts or tunnels.

- Create and look for patterns. Clap and stomp to music. Find patterns in your clothing or around the house like stripes on a rug. Line up a red block, then a blue, then red, and another blue. Ask what color comes next.

- Make time for math talk. Language is what brings math concepts to life for children. When you raise an infant up and down off your lap, they experience their body moving in space. But you mathematize the action and teach spatial concepts by saying “up” and “down” as you move them.

- Play with blocks. Blocks are a great way to encourage open-ended play. Infants can explore shape and size with their hands and mouth. Use shape words to describe the blocks like, “That block is a cube. Each side is a square.” Toddlers practice spatial concepts like “on” and “under” as they stack then eventually build.

- Put together puzzles. Children practice spatial skills as they rotate and turn each piece to find its place.

Learn More

- High Five Mathematize

- Finding the Math

- News You Can Use: Supporting Early Math Learning for Infants and Toddlers

- ELOF Effective Practice Guides: Emergent Mathematical Thinking

Connecting at Home

You can find math in just about everything you do. Think of the home as a learning environment that supports math learning. All you need is what is already in the environment. Discover objects and toys together to use for math related play. You can make children's play and routines mathematical through the language and support you provide while at home, around the neighborhood or your community.

Read a Book

Books don’t need to be about math. You can add math concepts to any book! Compare and contrast, describe the shape and size of objects, talk about numbers or spatial concepts like between and behind. Give toddlers space to fill in the word in a line that repeats itself to highlight patterns, like “Brown bear, brown bear, what do you (see).” Find a favorite book and think of how you can add math.

Play

I Spy ShapesPick a shape and look for it in the house, outside, or on an errand. Say, “I spy something round. What do you see?” Use spatial language to offer clues, like “it’s above the bookshelf.” Talk about the name and properties of the shape, such as, “The square has four sides and four points.” Older toddlers can spy objects too!

Fill and Dump

Find different size measuring cups, plastic containers, or spoons around the house. Let children fill and dump water in the kitchen sink, bathroom tub, or a bucket outside. What other materials can young children use to explore measurement? Invite toddlers to help measure ingredients the next time you make dinner.

What other materials can young children use to explore measurement? Invite toddlers to help measure ingredients the next time you make dinner.

Make It Routine

Routines teach children about patterns, but they can include other math concepts too! Snuggle up for a book and a bottle every day before nap. Don’t forget to introduce math concepts as you read. Turn your clean-up routine into a fun sorting task. “The blocks go in this bin and the puzzles go on the shelf.” Time your toddler to see how fast they can clean up!

« Go to Connecting Research to Practice

Read more:

Mathematics

, School Readiness

Resource Type: Publication

National Centers: Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning

Age Group: Infants and Toddlers

Last Updated: December 9, 2021

Mathematics for the little ones (from 0 to 3) - Academy of Development

Experts in the field of early child development have established the fact that children's thinking absorbs all information. In their opinion, all facts are deposited in the child's memory, which in the future are transformed into knowledge, but only if the material is presented at a high emotional level, exciting and tempting, without excessive perseverance.

In their opinion, all facts are deposited in the child's memory, which in the future are transformed into knowledge, but only if the material is presented at a high emotional level, exciting and tempting, without excessive perseverance.

This approach is absolutely justified in relation to the basics of mathematics, which the baby must certainly master. Such information enables the child to navigate in space, perform simple mathematical operations, logical tasks, and also determines the ability to use mathematical concepts such as size, shape. If the child is not familiar with the basic concepts, it will be more difficult for him to perceive the environment. Performing mathematical and logical tasks activates the mental activity of the baby, contributes to the development of thinking. nine0003

Where to start?

The first mathematical lessons should be started almost from the first days of life, namely in games that contribute to the development of tactile abilities. A newborn from the first days, thanks to vision, touch, learns to perceive the features of objects: size, texture, color. It is important not to forget to name these qualities for the child and demonstrate the properties during the game or everyday activities. Teach your child to compare objects around him. As illustrative examples, you can use toys, clothing, dishes, body parts. For example, you can describe your favorite toy like this: “Look at that big, brown bear. Try how shaggy and soft he is. Where is our little ball? The ball is blue, round. Let's touch it, how smooth it is. He jumps higher than you." nine0003

A newborn from the first days, thanks to vision, touch, learns to perceive the features of objects: size, texture, color. It is important not to forget to name these qualities for the child and demonstrate the properties during the game or everyday activities. Teach your child to compare objects around him. As illustrative examples, you can use toys, clothing, dishes, body parts. For example, you can describe your favorite toy like this: “Look at that big, brown bear. Try how shaggy and soft he is. Where is our little ball? The ball is blue, round. Let's touch it, how smooth it is. He jumps higher than you." nine0003

For a child who is able to explore space while crawling, adults can suggest directions in the horizontal plane. This should be done not intrusively, commenting on the movements of the child or joint movements with adults. When the child has reached the goal, he begins to persistently master the subject, using all the possibilities (feels, tries on the tooth, moves). At this moment, a small person activates the work of the brain, starts the processes of analysis. Adults must necessarily suggest what is in front of the child, what properties are characteristic of this object, and say the baby's feelings. (This cube is small, plastic, red, hard, and the pencil is long, thin, yellow, wooden). nine0003

Adults must necessarily suggest what is in front of the child, what properties are characteristic of this object, and say the baby's feelings. (This cube is small, plastic, red, hard, and the pencil is long, thin, yellow, wooden). nine0003

At the age of one, the foundations are laid for the further development of cognitive abilities. Parents should be patient and try not to limit the baby in his desire for knowledge of the world around him. It is necessary to prepare a house or apartment for the appearance of a baby, so that his movement around the home becomes safe, and also remove valuables away. G. Doman, a well-known American theorist of the early development of a child, is sure that difficulties and problems in learning appear later in those children who were limited by space during the crawling period, sat in the arena, and were not able to freely move around the house. Physiologists who specialize in pediatrics know that a child acquires certain knowledge or skills in the proper period of time, when the body is capable of it and has reached the appropriate level of development. nine0003

nine0003

At the age of one year, when a child begins to walk, it is important for him not only to feel the object, but also to understand the relationship between them. At this age, a real mathematical boom begins in the development of the baby. The child activates his skills of analysis and synthesis. For learning, as a visual aid, toys still occupy the main place.

Sufficiently complex concepts quickly fit into the baby's head thanks to a variety of bright pyramids, cubes and nesting dolls, balls, dolls, plush animals. When a child builds castles using building blocks, he gradually learns shapes and colors. But only if the parents comment on the implementation and name the geometric shapes. Simple exploration of toys will help the child master their basic qualities and their most striking properties. For example, a toddler will enjoy watching a ball roll down an incline, while blocks will not be able to roll around corners. Invite your child to feed the toy animals with colorful cookies, pick up caps for felt-tip pens of the appropriate colors. If the child constantly performs such tasks, he will quickly master the colors and the combination of the words “by color” will no longer be frightening. By organizing a game with a pyramid, the child will understand the ratio "more - less". nine0003

If the child constantly performs such tasks, he will quickly master the colors and the combination of the words “by color” will no longer be frightening. By organizing a game with a pyramid, the child will understand the ratio "more - less". nine0003

Studying numbers

There is no need to rush to study numbers. Until the age of three, children have concrete thinking. They perceive only those objects that can be touched and seen with their own eyes. Whereas numbers are something incomprehensible, meaningless, simple hooks and sticks. Toddlers perceive numbers in the same way that adults perceive Chinese characters. Since the memory of children is sufficiently formed, the child will be able to capture the meaning of these symbols, if necessary, reproduce and name numbers. But at an older age, the baby will re-master the material, learns to correlate the signs and the number of objects. For training, you can use nuts or sweets. nine0003

It should be noted that depending on the type of perception, children easily or difficultly memorize numbers. For example, visual kids (in whom vision prevails in the perception of the world around them) already at the age of two years reproduce numbers and letters. To teach a child or not at this age should be decided by parents, taking into account the interests of the child in symbols. If he has a desire to master incomprehensible signs, give the baby such an opportunity and satisfy his interest. But it is worth remembering that such features are not typical for all children of this age. It is important not to force the child to such activities if he does not show interest. Persistence of parents can cause rejection of information and lack of desire to master the material in the future. nine0003

For example, visual kids (in whom vision prevails in the perception of the world around them) already at the age of two years reproduce numbers and letters. To teach a child or not at this age should be decided by parents, taking into account the interests of the child in symbols. If he has a desire to master incomprehensible signs, give the baby such an opportunity and satisfy his interest. But it is worth remembering that such features are not typical for all children of this age. It is important not to force the child to such activities if he does not show interest. Persistence of parents can cause rejection of information and lack of desire to master the material in the future. nine0003

Three-year-olds must master the concept of the number of objects, as well as understand the relationship “many-few”. The best option for kids is learning from their own experience.

The American theorist of early childhood development G.Dogma, like Nikitin, suggests using dots to indicate the number of objects, Maria Montessori recommends using beads. Do not take such recommendations as a rule. Replace the beads with buttons, and the dots with sticks or matches. Count with your child everything that comes to hand: balls, cars in the parking lot, animals, pencils in cups, spoons, birds on a tree. You can start studying numbers after three years. nine0003

Do not take such recommendations as a rule. Replace the beads with buttons, and the dots with sticks or matches. Count with your child everything that comes to hand: balls, cars in the parking lot, animals, pencils in cups, spoons, birds on a tree. You can start studying numbers after three years. nine0003

Children will also be taught to count in kindergarten. Moreover, the child learns information much better if he is with his friends. If you are unable to send your child to a preschool, try placing him in a part-time kindergarten group.

We count everything

As a visual aid for a small child, you can use any children's book that is full of beautiful high-quality illustrations. You can train in the account by determining the number of objects depicted: butterflies, squirrels, berries, flowers, guys. Ask questions to the child so that he focuses his attention on the quantity. How many pens does the girl have? How many hands does a boy and a girl have together? How many paws does a cat have? How many paws does a dog have? How many shoes does the girl have? How many socks does a dog need? How many hats does the mushroom have? How many fish are in the aquarium? How many legs does a fish, octopus, spider, butterfly, bug have? nine0003

Do not try to stop a child by looking at other children if they are trying to learn to count. You can learn to count not only within a dozen. If this is interesting and easy for a child, try to master counting to one hundred. You can count in direct order, through a number, or in reverse. Such exercises contribute to the development of logical thinking, memory. Try to make tasks varied: compare the number of items, perform elementary mathematical operations, play supermarket, dominoes, dice. Focus not on the information you are trying to offer the child, but on the process and methods of learning. The main criterion for an impeccable process of education and upbringing is the positive emotions of the baby and the child. nine0003

You can learn to count not only within a dozen. If this is interesting and easy for a child, try to master counting to one hundred. You can count in direct order, through a number, or in reverse. Such exercises contribute to the development of logical thinking, memory. Try to make tasks varied: compare the number of items, perform elementary mathematical operations, play supermarket, dominoes, dice. Focus not on the information you are trying to offer the child, but on the process and methods of learning. The main criterion for an impeccable process of education and upbringing is the positive emotions of the baby and the child. nine0003

Sorting game. The game contributes to the development and training of mathematical logic, thinking. To organize the game, you can use improvised materials, for example, spoons, forks, cubes, toys, and other materials. You can get creative with the sorting process. Arrange special containers for items with appropriate openings. For example, a round hole for beans, a narrow oblong hole for buttons.

Taking into account the individual abilities of the child, tasks can be complicated by adding additional sorting signs. Tasks should be feasible for the child in order to create a situation of success. Try to constantly name household items in the kitchen, in the nursery, in the hallway. Name items of clothing when going for a walk, toys, cleaning the room, dishes, setting the table. nine0003

To increase the effectiveness of training, you should combine training with the activation of large and fine motor skills. This approach is especially important for children, who more clearly perceive the world around them through tactile sensations. For kinesthetic children, classes without movement have no benefit and result.

Mathematics also requires an integrated approach, taking into account the characteristics of children. You can play sorting not sitting in one place, but on the run. You can complicate the game by equipping an additional obstacle course in the room. While jogging, count steps, keep score, exercise, throw the ball. A great solution would be counting rhymes that can be played while walking in the park. nine0003

A great solution would be counting rhymes that can be played while walking in the park. nine0003

Auditory children, who absorb information by ear, learn mathematics very well in the process of learning songs, rhymes, fairy tales. For example, count the number of animals in the fairy tales "Mitten" or "Teremok". Ordinal counting can be mastered using the example of the fairy tales "Turnip" and "Gingerbread Man". Who did Kolobok meet first? Who is the biggest in the story? And who is the smallest? Who stood first behind the turnip? Who was Grandma behind? The fairy tale "Three Bears" is a real find for doing mathematics. Here you can count the number of bears, describe the sizes, and compare the animals, as well as establish the correspondence between bears and beds, chairs, and other items. nine0003

Indeed, mathematics at an early age has no boundaries. Parents need only be patient and creative to succeed in learning. Only in this way you will be able to turn difficult tasks into a fun and exciting game.

How to develop a child's mathematical abilities

Even if you do not plan to raise a genius like Euler or Pythagoras, this does not mean that your child will do without mathematics. After all, algebra and geometry are not just subjects of the standard school curriculum, but something much more. nine0003

They help develop the intellect, form logical and abstract thinking, train willpower. But how to make children fall in love with the world of numbers? The answer to this question is obvious to parents who work with babies using the world-famous Kumon notebooks. More details in our selection.

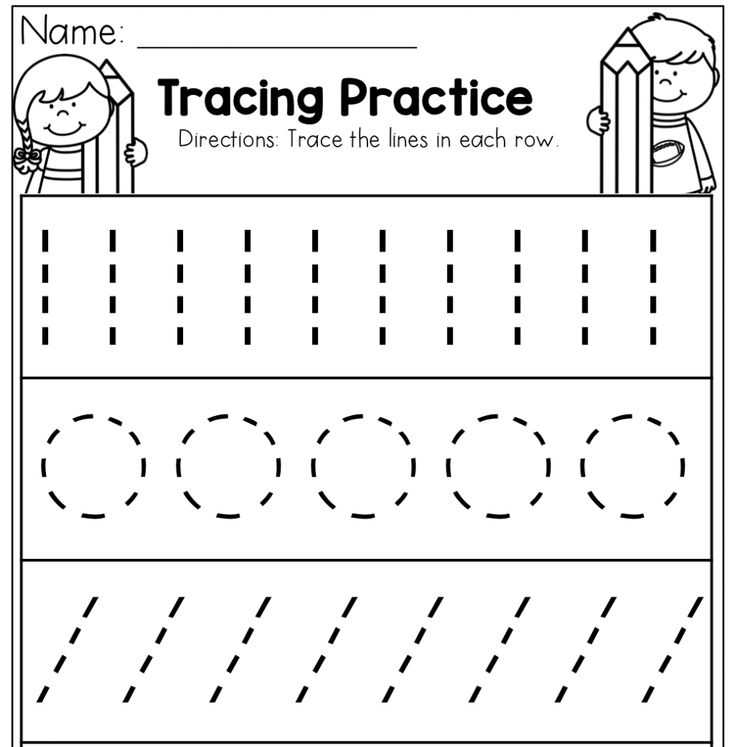

1. KUMON. Games with numbers from 1 to 150

This exercise book is intended for use with children from 4 to 6 years of age. It will help your child remember numbers up to 150, develop fine motor skills, master ordinal counting and fall in love with the world of numbers with all his heart. The child is waiting for game tasks of two types: connect by dots and color by numbers. He will be happy to perform these exciting exercises, and you will not even have to persuade him. nine0003

He will be happy to perform these exciting exercises, and you will not even have to persuade him. nine0003

Download task in pdf format

Similar notebook:

2. KUMON. Learning to count from 1 to 120

This notebook will not only help children from 4 to 6 years old to master counting, but also teach them to write numbers up to 120. The following types of exercises are waiting for the child: “Fill in the missing numbers”, “Connect the numbers one by one with a line”, “Circle the numbers by saying them out loud ". By completing tasks in order, from easy to difficult, the child will quickly memorize the shape of the numbers, work out the skill of writing and prepare to perform simple mathematical operations, such as subtraction and addition. nine0003

Download task in pdf format

Similar notebooks:

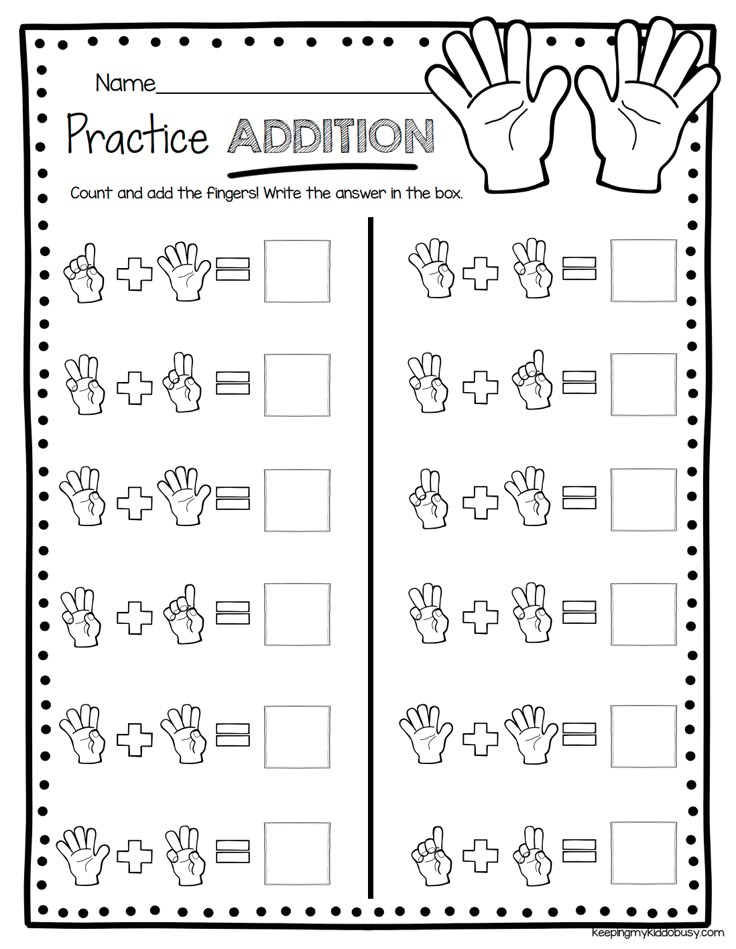

3. KUMON. Mathematics. Addition. Level 1

Workbook for preschoolers and first graders, which will help to master the action of addition. With it, the child will repeat the ordinal count and remember how numbers are written. And then he will move on to a new topic and learn how to solve easy examples. As in all Kumon notebooks, here the tasks become more difficult gradually so that children can easily understand how to add small numbers. nine0003

With it, the child will repeat the ordinal count and remember how numbers are written. And then he will move on to a new topic and learn how to solve easy examples. As in all Kumon notebooks, here the tasks become more difficult gradually so that children can easily understand how to add small numbers. nine0003

Download task in pdf format

Similar notebooks:

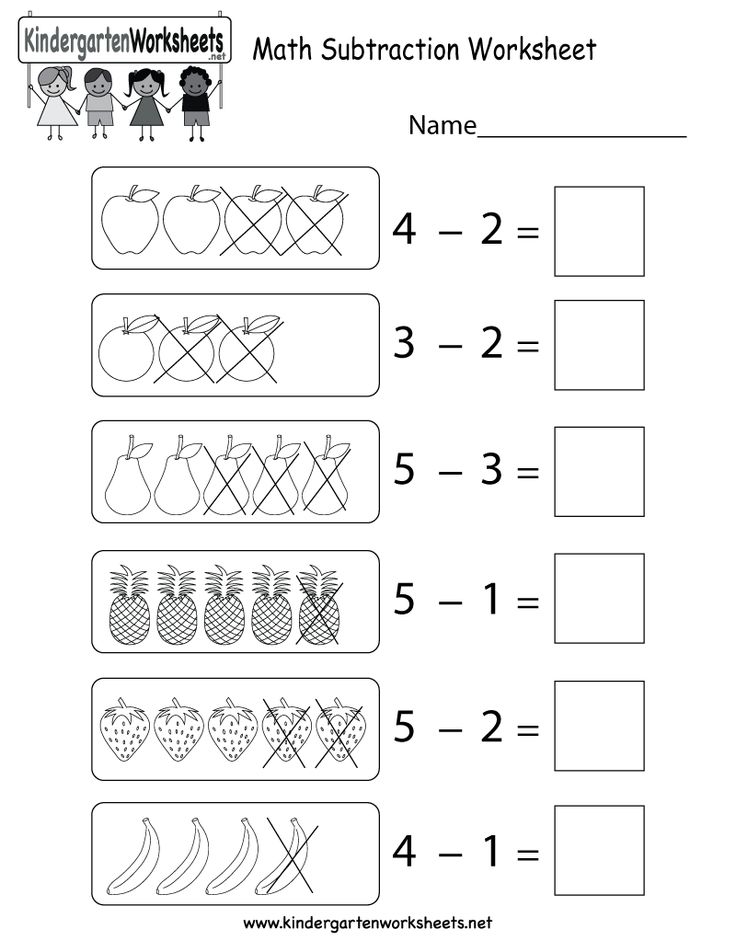

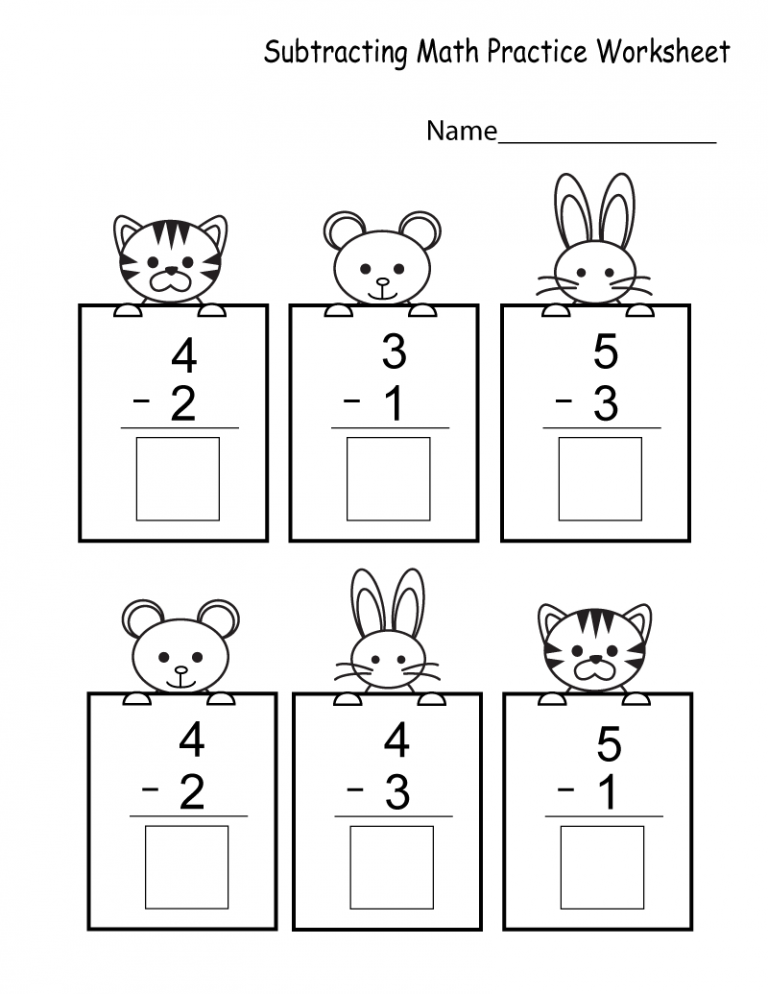

4. KUMON. Mathematics. Subtraction. Level 1

Together with this notebook, the child will repeat counting and addition, in order to then learn a new topic - subtraction of single and double digits. He will not need the help of adults: moving from simple examples to more difficult ones and independently checking the number series, the young mathematician will learn to perform subtraction exercises without much effort. nine0003

Download task in pdf format

Similar notebooks:

5.

KUMON. Mathematics. Addition and subtraction. Level 3

KUMON. Mathematics. Addition and subtraction. Level 3

Addition and subtraction for those who have already mastered the account well and learned how to perform simple mathematical operations with two-digit numbers. If a child is ready to move to an advanced level and solve more difficult examples, this notebook will come in handy.

nine0002Download task in pdf format

6. KUMON. Mathematics. Multiplication. Level 3

If your child is great at addition and subtraction, it's time to teach him how to multiply. With this notebook, he will learn what multiple addition is and will be able to move on to the next stage. Solving examples, a little mathematician will gradually memorize the entire multiplication table.

Download task in pdf format

Similar notebooks:

7. KUMON. Mathematics. Division. Level 3

Notebook for elementary school students and preschoolers who have successfully mastered all previous mathematical operations: counting, addition, subtraction and multiplication.