My children can read

Your Child Can Read!

Toggle Nav

Search

Search

Menu

Account

Settings

Language

English (US)

- Add More

Currency

USD - US Dollar

- GBP - British Pound

- EUR - Euro

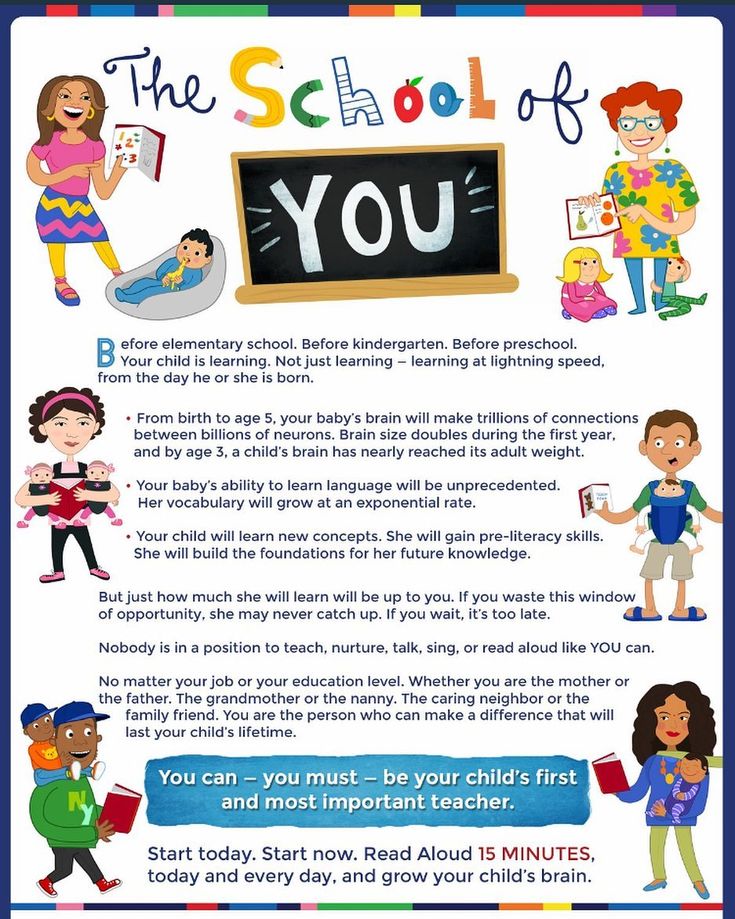

Your Child Can Read! is the follow-up series to Your Baby Can Learn! Children under age 5 years should use the Your Baby Can Learn! series before starting this program. Please click here to see Your Baby Can Learn! kits.

Sort By Position Product Name Price Set Descending Direction

View as Grid List

11 Items

Show

15 30 All

per page

Sort By Position Product Name Price Set Descending Direction

View as Grid List

11 Items

Show

15 30 All

per page

Filter

Shopping Options

Teaching children to read isn’t easy.

How do kids actually learn to read? A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

How do kids actually learn to read? A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

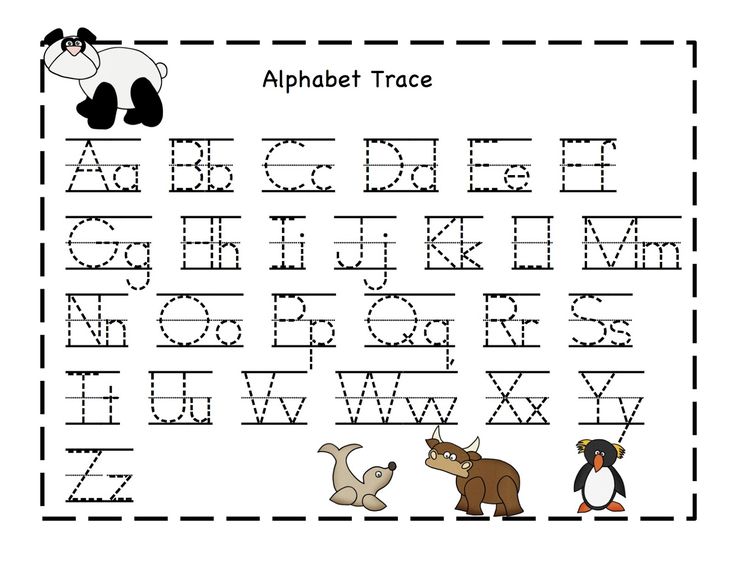

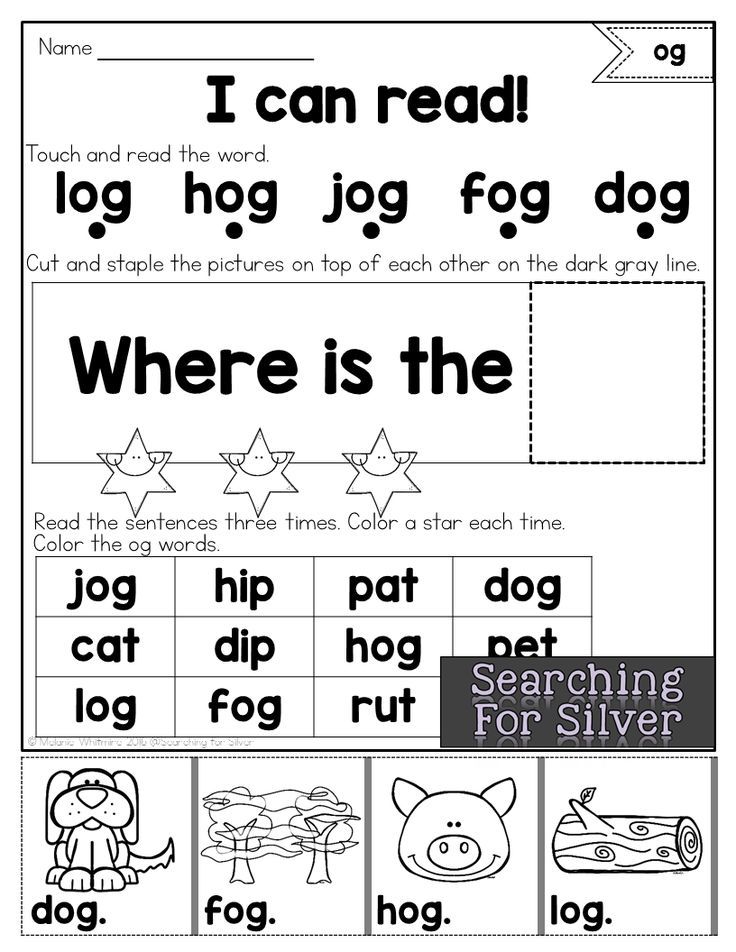

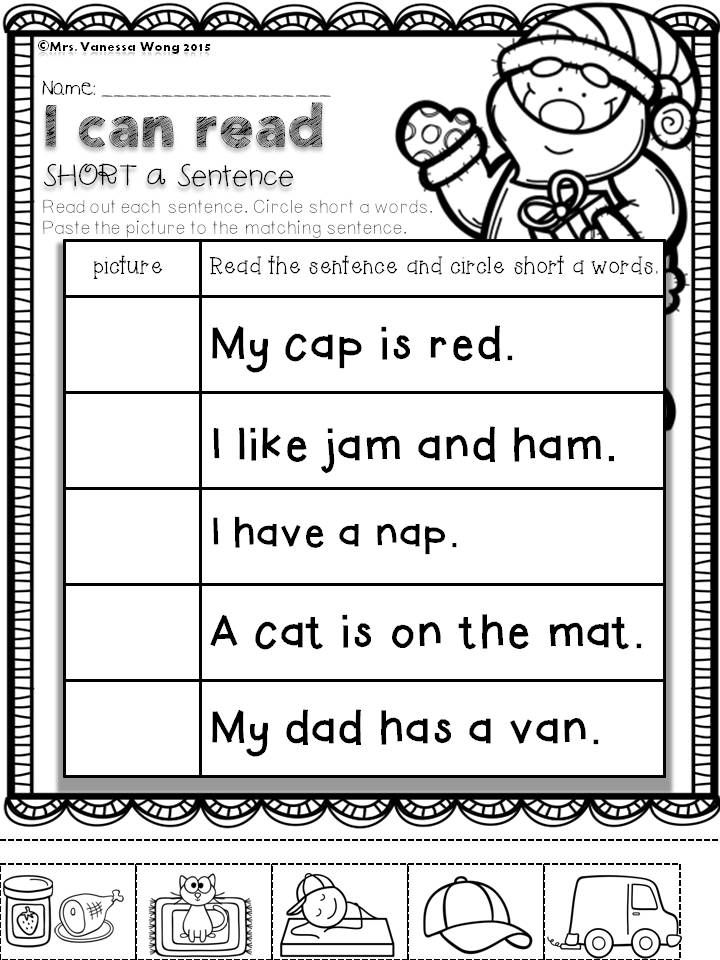

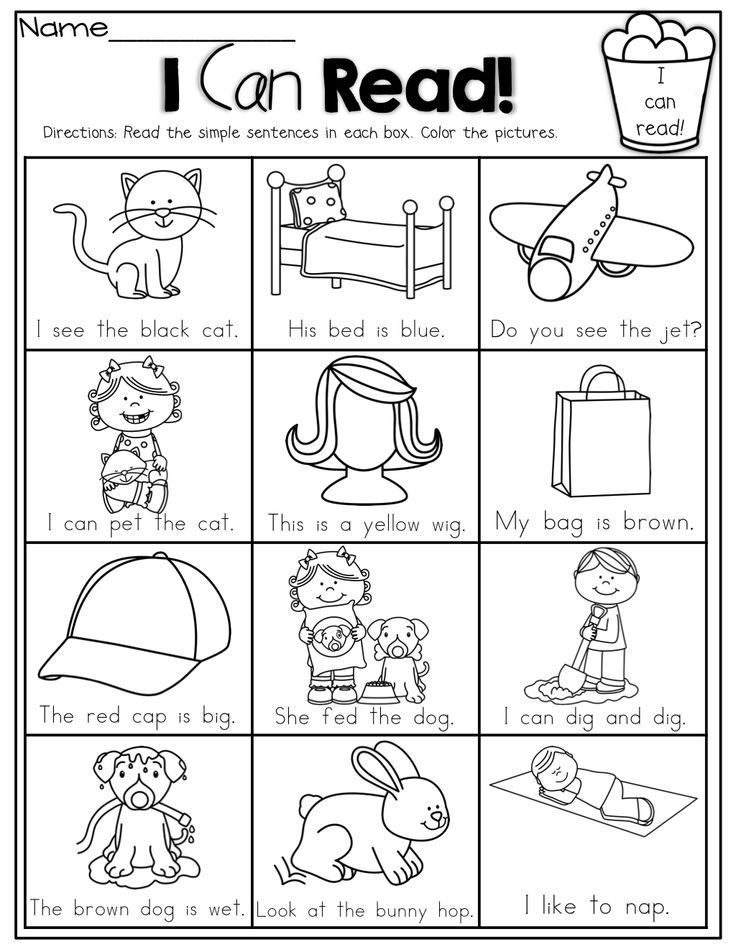

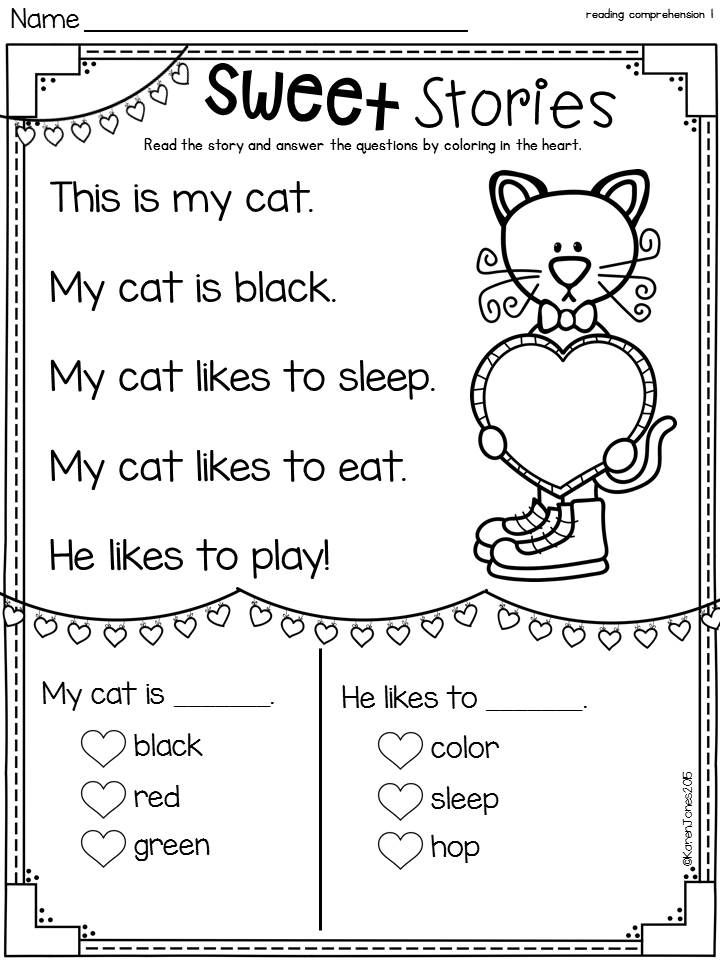

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

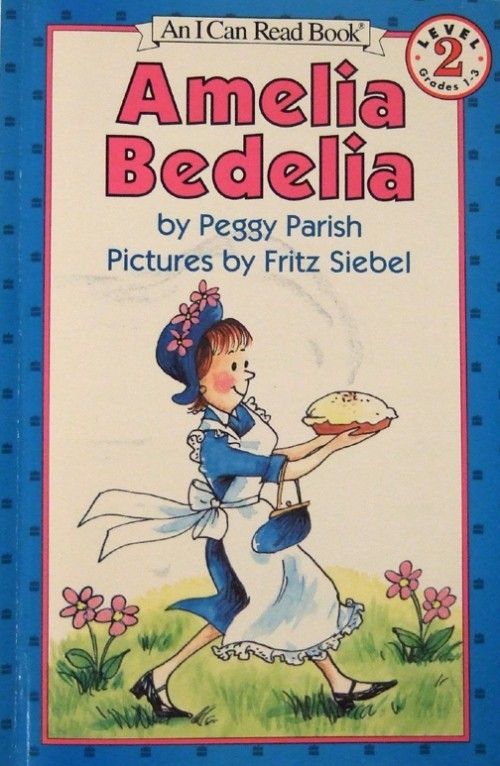

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

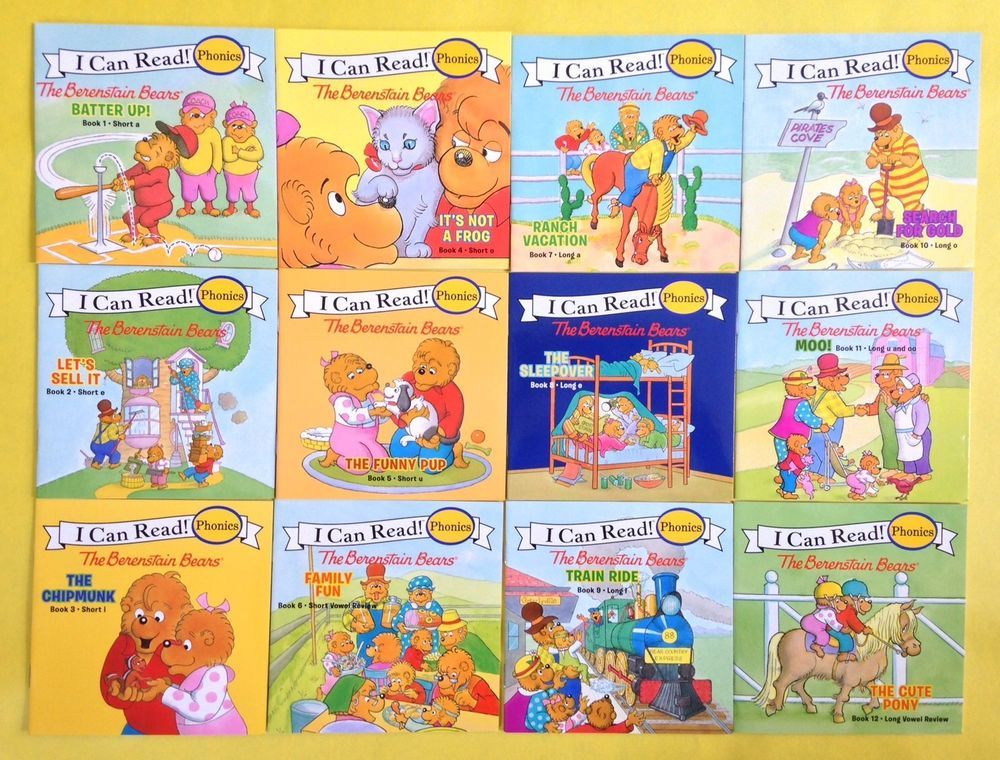

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

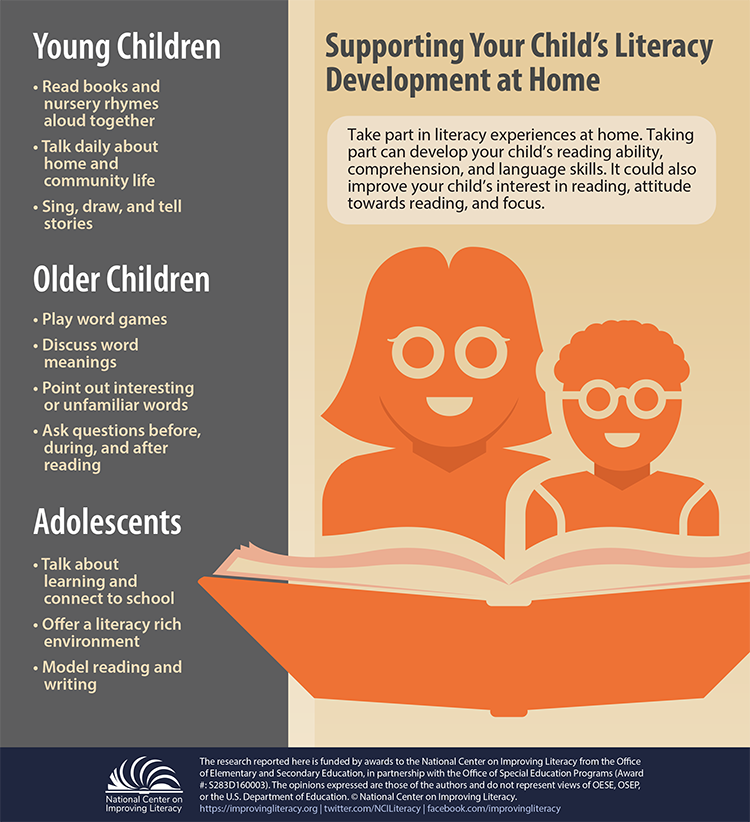

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

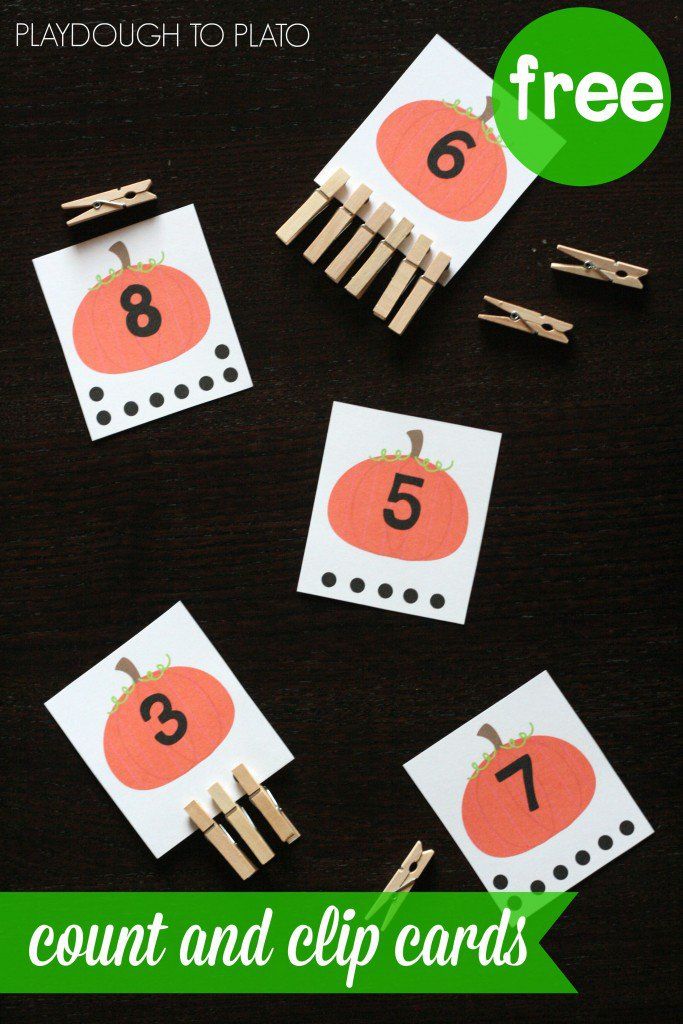

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

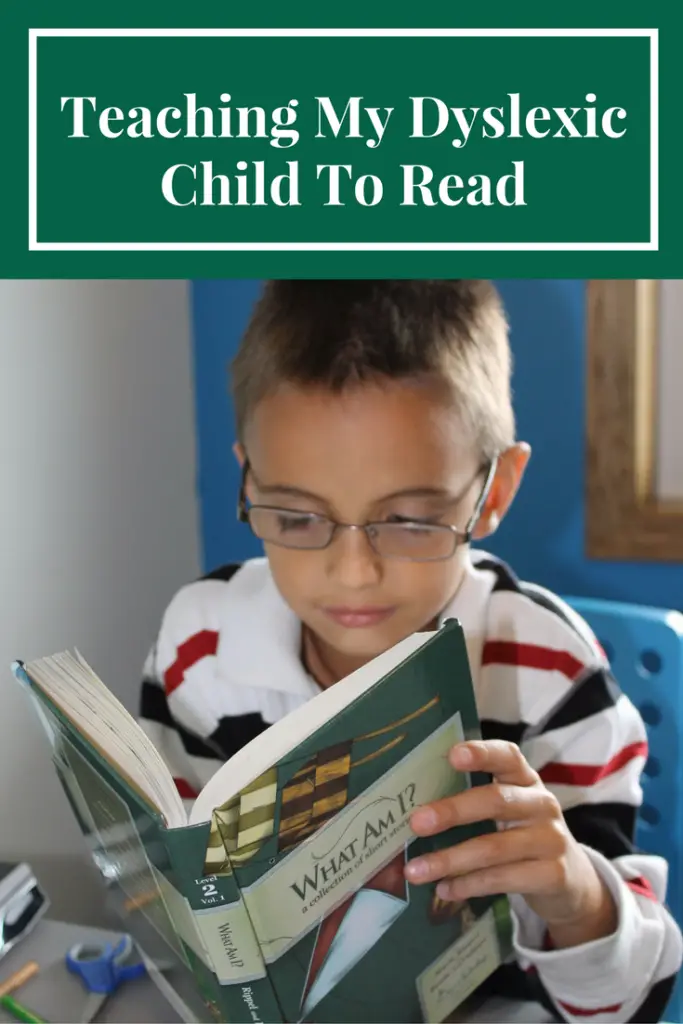

Why can't my children read like everyone else?

Society 3427

Share

“My grandson is three years old. He doesn't talk at all. They turned to doctors. There were examinations. Doctors shrug. His hearing is normal. He understands the speech addressed to him. But he doesn't want to talk."

He doesn't talk at all. They turned to doctors. There were examinations. Doctors shrug. His hearing is normal. He understands the speech addressed to him. But he doesn't want to talk."

“My daughter graduated from the first grade, but she still can't learn to read and write. We go to additional classes, hired a tutor - all in vain. I do not know what to do".

“My granddaughter studied in the second grade last academic year. She has trouble reading and writing. Confuses letters all the time. Many of them do not speak. Poor memory for spelling words.

“I am 16 years old. I often stumble and forget words. I get nervous when I talk to my friends. Often, when I read some text, the first time I understand it with difficulty. I need to read it again. I think I have dyslexia."

These are excerpts from complaints addressed to psychologists and speech therapists. They are quite typical. A sixteen-year-old girl diagnosed herself with dyslexia. It may well be that she is right. What is it? Dyslexia, according to Wikipedia, is "a selective impairment of the ability to master reading and writing skills while maintaining a general ability to learn."

What is it? Dyslexia, according to Wikipedia, is "a selective impairment of the ability to master reading and writing skills while maintaining a general ability to learn."

Many scientists agree that this phenomenon is based on neurobiological reasons. Researchers find dyslexics have idiosyncrasy in the brain, a special condition that makes it difficult for them to associate letters and combinations of letters with certain sounds. A genetic factor is also not ruled out.

Specialists in different countries differ in the interpretation of the term "dyslexia". In the West, including the United States, many, though not all, tend to associate reading and writing disorders with them. Russian speech therapists prefer to consider dyslexia separately as a violation of oral speech, and for written language they use other terms - dysgraphia, dysorphography. But all this is very close and interconnected. Even some of the symptoms are similar.

Your child gets tired easily and avoids reading and writing homework. Holds a pen or pencil awkwardly and has difficulty using these items. He reads very badly, much worse than most of his peers. Skips single words and entire paragraphs. Complains of headache while reading and after. Often rubs eyes and squints a little. When reading, holds the book close to the eyes, sometimes covers or closes one eye, or turns the head so that one eye does not participate in reading. Oral communication is normal, but it is difficult to transfer their thoughts to paper. In early childhood, he writes words backwards. The handwriting is bad, the words crawl over each other. With difficulty remembers, recognizes and reproduces basic geometric shapes.

Holds a pen or pencil awkwardly and has difficulty using these items. He reads very badly, much worse than most of his peers. Skips single words and entire paragraphs. Complains of headache while reading and after. Often rubs eyes and squints a little. When reading, holds the book close to the eyes, sometimes covers or closes one eye, or turns the head so that one eye does not participate in reading. Oral communication is normal, but it is difficult to transfer their thoughts to paper. In early childhood, he writes words backwards. The handwriting is bad, the words crawl over each other. With difficulty remembers, recognizes and reproduces basic geometric shapes.

Each of these symptoms alone may not be a sign of dyslexia. And it is likely that the child should not be shown to a speech therapist, but, say, to an ophthalmologist or some other specialist. But in the aggregate, this is a good reason to suspect precisely "impaired ability to master the skills of reading and writing. " And keep in mind that with such disorders in the intellect of your son or daughter there are no flaws. Moreover, some scientists believe that dyslexia is one of the signs of genius, and as proof they cite examples from the life of Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison, Peter the Great, Winston Churchill, Walt Disney, Tom Cruise and many other celebrities who at different periods of his life experienced difficulties in reading and writing.

" And keep in mind that with such disorders in the intellect of your son or daughter there are no flaws. Moreover, some scientists believe that dyslexia is one of the signs of genius, and as proof they cite examples from the life of Albert Einstein, Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison, Peter the Great, Winston Churchill, Walt Disney, Tom Cruise and many other celebrities who at different periods of his life experienced difficulties in reading and writing.

In any case, the diagnosis should not be rushed. Yes, and it is difficult for parents to put it. It is easy to mistake for dyslexia in the kindergarten period of various kinds of developmental delays, but do not give in to this temptation. Reading problems are observed in more than half of first-graders. But in only 5-8 percent of these children, it can turn into something serious.

A well-known specialist in this field, academician of the Russian Academy of Education, director of the Institute of Developmental Physiology Maryana Bezrukikh writes:

“If by the third or fourth grade of school a child still reads by syllables, tries to guess words, rearranges or swallows letters and their combinations, constantly loses a line or repeatedly returns to a word already read, then in this case experts diagnose “dyslexia” ". But she herself believes that this is wrong: “A defectologist or neuropsychiatrist has no right to make this diagnosis before the child is 10-11 years old. Until this age, we can only talk about the presence of difficulties in learning to read and write.

But she herself believes that this is wrong: “A defectologist or neuropsychiatrist has no right to make this diagnosis before the child is 10-11 years old. Until this age, we can only talk about the presence of difficulties in learning to read and write.

However, a diagnosis is a diagnosis, and alertness and attention to anomalies are appropriate and correct at any age. Academician Bezrukikh also admits this: “If in the first six months of study a first-grader sits down at a primer under pressure, parents should not waste time. If you catch yourself in time, you can cope with this problem completely. ”

It is only necessary to understand the origin of the disorder and, with the help of specialists, find ways to correct it.

When parents get involved

A decade ago, only five states had laws that mentioned the word "dyslexia." Now Wisconsin could become the 46th such state. Here, the lower house of the legislature has already approved bill AB-110, which addresses the needs of children who are found to have this condition. True, the law still has to be passed by the Senate and signed by the governor. But that seems to be the case, and the time is not far off when dyslexics will legally receive help. After all, this year alone, according to the Dyslexia website, lawmakers are expected to consider 75 (!) different legal acts related to the problem of dyslexia across the country at the state level. Why such attention, such a wave of public interest? And how can one explain the impressive victories at the legislative level? Legal experts, teachers, literacy advocates all point to an organization called Decoding Dyslexia. It originated in 2011 when several parents in New Jersey, mostly mothers, concerned about what was happening to their children, found themselves facing similar problems in their families that had nothing to do with where they lived. and what is the quality of education in a particular school district. They were united by the fact that the children had a hereditary pathology and that, as it seemed to the parents, it could be corrected.

True, the law still has to be passed by the Senate and signed by the governor. But that seems to be the case, and the time is not far off when dyslexics will legally receive help. After all, this year alone, according to the Dyslexia website, lawmakers are expected to consider 75 (!) different legal acts related to the problem of dyslexia across the country at the state level. Why such attention, such a wave of public interest? And how can one explain the impressive victories at the legislative level? Legal experts, teachers, literacy advocates all point to an organization called Decoding Dyslexia. It originated in 2011 when several parents in New Jersey, mostly mothers, concerned about what was happening to their children, found themselves facing similar problems in their families that had nothing to do with where they lived. and what is the quality of education in a particular school district. They were united by the fact that the children had a hereditary pathology and that, as it seemed to the parents, it could be corrected. Such boys and girls needed to be taught to read more carefully. Especially what is connected with the understanding of phonemes: what sound corresponds to a particular letter and how to pronounce it correctly. Of course, all this required additional attention and efforts on the part of teachers. And the schools either did not want, or simply were not able to provide such assistance to students.

Such boys and girls needed to be taught to read more carefully. Especially what is connected with the understanding of phonemes: what sound corresponds to a particular letter and how to pronounce it correctly. Of course, all this required additional attention and efforts on the part of teachers. And the schools either did not want, or simply were not able to provide such assistance to students.

“I wanted to talk about all this with other parents,” recalls Kathy Stratton, one of the founders of Decoding Dyslexia. “Because in families where there is a child with dyslexia, you feel so isolated from the rest of the world.”

And the parents, who were brought together by a common misfortune, began to meet, exchange opinions, seek new information. They were part of their state's dedicated Reading Impairment Task Force. And in the end, their determination and assertiveness paid off. In December 2012, six draft laws relating to dyslexia were proposed for consideration by the deputies of the Assembly

New Jersey. Three of them have been approved. The parents didn't stop there. Their representatives went to Washington to interest the US Congress. After that, 10 of the 12 legislators representing New Jersey entered the bipartisan Congressional Dyslexia Caucus.

Three of them have been approved. The parents didn't stop there. Their representatives went to Washington to interest the US Congress. After that, 10 of the 12 legislators representing New Jersey entered the bipartisan Congressional Dyslexia Caucus.

Further, more. New Jersey moms and dads have used the power of social media to connect with fellow sufferers across the country. The creators of Decoding Dyslexia have released something like a tutorial. By 2015, they had branches in all 50 states and Canada. Members of this movement pushed for the passage of laws requiring children to be tested for dyslexia at an early age, provide them with access to audio books and other means of correcting the disorder, arrange mandatory special training for teachers, regularly test children, and so on. That same year, President Obama signed into law a federal law called READ (an acronym for Research Excellence and Advancements for Dyslexia). It provided for $2.5 million annually from the National Science Foundation for research on dyslexia.

One can, of course, admire and pay tribute to the activity of parents. However, let's not deceive ourselves: success in lawmaking is only part of the matter, it is not yet a cure.

"How to cut a cake properly?"

No one is opposed to helping children read and raise the literacy rate that so many Americans complain about. However, there are educators who do not welcome the activities of Decoding Dyslexia. Yes, they say, there are many dyslexics in the country - from 5 to 15 percent of the total population of the country. Higher figures are also cited: one in five Americans. But opponents object to the emphasis on method, where children are taught to read and pronounce words based on the phonetic equivalent of letters, letter combinations, and especially syllables. How else? Recently, the International Literacy Association stated on the issue of dyslexia: "At the moment, there is no reliable method of teaching children who have reading difficulties. " Curiously, the Wisconsin branch of this association opposed the passage of Bill AB-110.

" Curiously, the Wisconsin branch of this association opposed the passage of Bill AB-110.

Even some advocates for children with physical and mental disabilities do not rave about the success of Decoding Dyslexia.

“Illiteracy is a huge national problem. But dyslexia is not the same as illiteracy,” says California State University professor Jasmine Harris. It puts socioeconomic factors first. In her opinion, malnutrition and health problems have the strongest impact on schoolchildren's ability to learn. Harris worries about how the government allocates its rather meager funds to "children with special needs." “I wouldn't favor either group,” she says. But how do you cut a pie properly?

Methodological and ideological disputes continue, which, according to parents concerned with dyslexia, distracts them from solving their problem. Liz Barnes, the New Jersey mother who pioneered Decoding Dyslexia, says she is bombarded with email every day that is dominated by a single question: "What can I do to help my child?"

Robert Buck, one of the members of the Decoding Dyslexia movement, has an answer to this: "If children are not able to learn in the way we teach them, then we must teach them differently - so that they are able. "

"

Subscribe

The authors:

- Lev Borshevsky

Government of the Russian Federation Barack Obama USA Washington Baku Canada Children School Books healthcare Governor Science

- 21 Oct

Creative industries in Siberia can get a new impetus for development thanks to cultural events

- Oct 20

Digitization will help solve the personnel problem

- Oct 17

New media: who and how forms the modern information field

What else to read

-

UAV UAV attacked with grenades the trenches of the Russian military in the Belgorod region

34539

Artem Koshelenko

-

Ukrainian trace found in Boris Moiseev's fatal illness

A photo 15845

Denis Sorokin

-

In Crimea, the anti-terrorist commission will take care of Zelensky's apartment

33887

Oleg Tsyganov

-

The State Duma wants to increase the term of service in the army

15551

Oleg Tsyganov

-

Zelensky commented on Moscow's statement about receiving guarantees from Ukraine

40911

Alexander Shlyapnikov

What to read:More materials

In the regions

-

Grain deal suspended due to terrorist attack in Sevastopol

42026

CrimeaPhoto: Pixabay.

com

com -

"The girl went into hysterics": what was happening at the time of the shelling of the bus in Pskov

A photo 22392

PskovSvetlana Pikaleva

-

In Yaroslavl, an elite complex was left without water and heating

13442

Yaroslavl -

Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation: Sevastopol was attacked by 9 aircraft and 7 sea drones

12891

Crimeaphoto: crimea.

mk.ru

mk.ru -

The head of the Yaroslavl region told the residents of Yaroslavl what to do with the received subpoenas

7949

Yaroslavl Red tape and "creative" interpretation of laws

are seen in the work of the Sverdlovsk Regional Court4223

YekaterinburgMaxim Boykov

In the regions:More materials

What do your children read? – Power – Kommersant

635 4 min. ...

...

| Question of the Week | Number 010 dated 14-03-2000 Band 002 |

What do your children read?

The land of bears, ballet and oil — this is what Russia looks like on the pages of translated children's books, with which all stores are filled today (see p. 44). We decided to find out if these books are popular with readers.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, State Duma deputy. For my five-year-old Natasha, the hit is The Wizard of the Emerald City. He also likes some books about ninja turtles. Natasha can read, but she is lazy, so we read to her every day for an hour and a half. She has her own children's library: Marshak, Barto, Mikhalkov, Chukovsky, Oster, Andersen, many folk tales - Russian, Scottish, Japanese.

Natasha can read, but she is lazy, so we read to her every day for an hour and a half. She has her own children's library: Marshak, Barto, Mikhalkov, Chukovsky, Oster, Andersen, many folk tales - Russian, Scottish, Japanese.

Sergei Reusov, Deputy Chairman of the Board of Credittrust Bank. The last book that I saw in the hands of my son were some horror stories of Uspensky. In general, it is very difficult to teach him to read. As a child, I read him a lot of Russian folk tales, Charles Perrault, attracted him with beautiful pictures and comics, but with age, his desire to read disappears. This is another generation that is accustomed to television and computers.

Nikolai Egorov, President of the Russian Aikido Federation. All. My daughter started to read on her own early, and my son was a terrible fidget, and it was difficult for me to accustom him to books. One day, when he was about ten years old, I brought him a book about the Indians. He was so captivated by this reading that he even read at night. And after that I began to read books avidly. Neither TV nor computer can replace them.

And after that I began to read books avidly. Neither TV nor computer can replace them.

Pavel Krasheninnikov, Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Legislation. I am lucky, I have very reading children. They read the books of Bazhov, O'Henry, they love science fiction. And my son's first book was one of my books, although I understand that this is wrong. But until now, and he is 12 years old, he is my first reader and main censor. His reference book is the Civil Code.

Yuri Bondarev, writer. My kids read everything except Afanasiev's mischievous tales and explicit sex. And now the children have nothing to read. Neither the good old "Funny Pictures" nor the real "Murzilka" for you. Debauchery is solid, only computers. Here is my first book - "Youth Army" - was about children in the civil war. Patriotism should be instilled in children from a very early age with the help of such books. Then the child learns good and develops in a normal way.

Oleg Morozov, head of the Russian Regions parliamentary group. The main thing is to push the child, and then he himself forces reading and even foreign languages. My daughter learned English from the cradle and now knows it perfectly. At the age of three she began to read herself, and before that I often spoiled her with "Cat's House". She grew up and began to read Cooper, Mine Reed.

The main thing is to push the child, and then he himself forces reading and even foreign languages. My daughter learned English from the cradle and now knows it perfectly. At the age of three she began to read herself, and before that I often spoiled her with "Cat's House". She grew up and began to read Cooper, Mine Reed.

Alexander Volodin, playwright. My kids didn't start with children's books. The eldest from the age of nine read Dostoevsky and Pasternak. Yes, and the younger did not lag behind him - he loved Gogol. No one read books to me as a child. True, my older brother in my adolescence drew me into reading supermen - Nietzsche, Schopenhauer. And then I came to Kant.

Lyudmila Pikhoya, Assistant to the Head of the Federal Tax Police Service. There have never been any problems to accustom to reading in our family. The granddaughter loves the fairy tales of Pushkin and Green very much. Read by yourself, read together. The son, an ironic man, read Ilf and Petrov, Bulgakov avidly.

Viktor Erofeev, CEO of Pharmamed. My five-year-old daughter reads fairy tales herself, fluently. I don’t know what kind, my mother does this with us. And now I myself only read detective stories for the future.

Olga Gryadovaya, Chairman of the Board of Transcapitalbank. By the age of 17, "Quiet Flows the Don" and Zoshchenko mastered. In order not to waste time, the children consult with me and my husband what to read. I advise the classics, especially ours, because in the future they will somehow come into contact with the world. The eldest daughter, who is 24 years old, reads books on English law in the original.

Vladimir Shumeiko, leader of the Reforms - New Deal movement. Now with the grandson we master the alphabet. And I taught children life according to Bianchi. My principle is simple - the child became a little interested, which means that you need to put the book aside and say: "When you learn to read, then you will find out what happened next. " Operates flawlessly.

" Operates flawlessly.

Igor Lipanov, Deputy Chairman of the Board of Sobinbank. The eldest, he is 18 years old, now reads Bunin, the middle daughter, 13 years old, reads Efremov's Tais of Athens. And the youngest still can’t read himself, but listens with pleasure about Carlson. But, to be honest, they begin to read mainly when their parents pull them away from the TV by the ears.

Irina Saltykova, singer My Alice, at the age of 12, read as much as I have not read in my entire life. Now he is reading the collected works of Dumas. Loves Chekhov. It was unrealistic to force me to read as a child, so I was worried because of her. But she learned to read at the age of three and a half and reads a lot.

Vladimir Shainsky, composer. I have two kids and are already friends with Shakespeare. And it is also very funny for them to read about how Agafya Timofeevna bit off the ear of the assessor - from "The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich. " I read this thing when I was four years old.

" I read this thing when I was four years old.

Alexandra Burataeva, State Duma deputy. This is a different generation: they first watch movies, and only then read books. My daughter is 13 years old, she reads detective stories avidly. After I took her to the opera Eugene Onegin, she read Pushkin. After the movie Heart of a Dog, I also read Bulgakov.

Viktor Bolotov, Deputy Minister of Education of Russia. I advise my daughter to read Remarque, the Strugatskys, the classics. And young children need to read classic fairy tales that teach human values, such as Andersen. I also think that all teenagers should definitely read Ilf and Petrov. The only thing I oppose as a matter of principle is books intended only for passing exams.

Evgeny Osin, artist. "They dropped the bear on the floor" - a classic. And coloring books with large letters. Children are generally smarter than us. And what poetry they have! I even recorded an album for children's poems.

Telman Gdlyan, President of the All-Russian Foundation for Progress, Protection of Human Rights and Mercy.